Cultural Resources Survey of the Ghost Ranch Lodge, Tucson, Pima County, Arizona

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of Cultural Resources Survey of the Ghost Ranch Lodge, Tucson, Pima County, Arizona

Cultural Resources Survey of the Ghost Ranch Lodge, Tucson, Pima County, Arizona

Allison Cohen Diehl Reviewed by Patricia Castalia Desert Archaeology, Inc. 3975 N. Tucson Boulevard Tucson, Arizona 85716 Submitted to Marty McCune City of Tucson P.O. Box 27210 Tucson, Arizona 85726-7210

Project Report No. 04-162 Revised Desert Archaeology, Inc. Project No. 01-121FK 3975 N. Tucson Blvd., Tucson, AZ 85716 ● 4 May 2005

ABSTRACT DATE: 4 May 2005 AGENCY: City of Tucson REPORT TITLE: Cultural Resources Survey of the Ghost Ranch Lodge, Tucson, Pima County, Arizona. CITY OF TUCSON PROJECT NAME: Ghost Ranch Lodge CITY OF TUCSON PROJECT NUMBER: 04-35 FUNDING LEVEL: City PROJECT DESCRIPTION: Survey in advance of property redevelopment. PERMIT NUMBER: Arizona Antiquities Act Blanket Permit No. 2004-005bl, Arizona State Museum Accession No. 2004-0817. LOCATION:

County: Pima

Description: Section 35, Township 13 South, Range 13 East on the USGS 7.5-minute topographic quad Tucson North, Ariz. (AZ BB:9 [SW]).

NUMBER OF SURVEYED ACRES: 5.8 NUMBER OF SITES: 1 LIST OF REGISTER-ELIGIBLE PROPERTIES: Ghost Ranch Lodge district (AZ BB:9:393 [ASM]) LIST OF INELIGIBLE SITES: 0 RECOMMENDATIONS: The project area contains the historic Ghost Ranch Lodge (BB:9:393) built between 1941 and 1974. The area was given a single archaeological site number. It is treated in this report as a district because it contains multiple elements. The original 1941 courtyard is significant as an example of the architectural design of Josias Joesler (National Register Criterion C). These buildings as well as others constructed at a later date and designed to be compatible with the original buildings and a historical sign featuring the artwork of Georgia O’Keefe are significant within the context of the expansion and evolution of tourism in the early twentieth century (National Register Criterion A). Construction plans, as currently envisioned, will not threaten the National Register eligibility of the district as a whole. However, any contributing elements to be demolished should be documented prior to removal, and the original neon sign removed to a location where it will be preserved.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ABSTRACT ........................................................................................................................................... 2 LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................................... 5 LIST OF TABLES ................................................................................................................................. 6 PROJECT AREA LOCATION AND DESCRIPTION ..................................................................... 7 ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING OF THE PROJECT AREA ......................................................... 15 CULTURAL BACKGROUND OF THE PROJECT AREA ........................................................... 15 Paleoindian Period ....................................................................................................................... 15 Archaic Period .............................................................................................................................. 16 Early Agricultural Period ............................................................................................................ 17 Early Ceramic Period ................................................................................................................... 17 Hohokam Sequence ..................................................................................................................... 18 Protohistoric Period ..................................................................................................................... 19 Spanish and Mexican Periods ..................................................................................................... 19 American Period ........................................................................................................................... 20 PREVIOUS ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESEARCH ........................................................................... 25 SURVEY METHODS AND RESULTS ............................................................................................ 27 SIGNIFICANCE ASSESSMENT ...................................................................................................... 28 National Register of Historic Places .......................................................................................... 28 Significance of the Ghost Ranch Lodge ..................................................................................... 28 Integrity of the Ghost Ranch Lodge ........................................................................................... 31 ASSESSMENT OF PROJECT EFFECT ............................................................................................ 32 Criterion A ..................................................................................................................................... 32 Criterion C ..................................................................................................................................... 34

Table of Contents Page 4

RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................................................................................... 34 REFERENCES CITED ....................................................................................................................... 36 APPENDIX A: ASM Site Card ......................................................................................................... 41 APPENDIX B: Historic Property Inventory Form ........................................................................ 46

LIST OF FIGURES

1. Reproduction of USGS 7.5-minute topographic quad Tucson North, Ariz. (AZ BB:9 [SW]), showing location of project area .................................................................... 8 2. Aerial photograph of the Ghost Ranch Lodge property, 2001 ............................................... 9 3. Proposed demolition and construction plans ......................................................................... 10 4. Building M (1946-1953) yard and façade, to be stabilized .................................................... 11 5. Principal façade of Building S (1953-1967), one of the modern buildings along the rear property line to be replaced with 2-story units ........................................................ 11 6. Holiday Service Station (1950) .................................................................................................. 12 7. Motel lobby, restaurant, and office building (Buildings R and T), to be demolished ....... 13 8. The Ghost Ranch Lodge sign, featuring the artwork of Georgia O’Keefe, to be removed .............................................................................................................................. 13 9. Original 1941 Ghost Ranch Lodge courtyard area, lined with Joesler-designed buildings to be retained ............................................................................................................. 14 10. Joesler-designed Buildings E and F (1941), showing carport screening to be retained ............................................................................................................................... 14 11. Ghost Ranch Lodge site plan showing the sequence of building construction ................. 24 12. Contributing and non-contributing elements of the Ghost Ranch Lodge district ............. 29

LIST OF TABLES 1. Periodization and chronology of the Santa Cruz Valley-Tucson Basin prehistory ........... 16 2. Previously recorded archaeological sites within 1 mile of the project area ........................ 25 3. Previous cultural resource surveys conducted within 1 mile of the project area .............. 26 4. National Register eligibility criteria ......................................................................................... 28

CULTURAL RESOURCES SURVEY OF THE GHOST RANCH LODGE, TUCSON, PIMA COUNTY, ARIZONA This report presents the results of a cultural resources survey of the Ghost Ranch Lodge in Tucson, Pima County, Arizona (City of Tucson Project No. 04-35). The work was requested by the City of Tucson to determine whether the rehabilitation of the motel facility for low-income senior housing will have any effect on significant archaeological or historical properties that may be present. William H. Doelle, Ph.D., of Desert Archaeology, Inc., is the Principal Investigator for the project. Allison Diehl of Desert Archaeology conducted the field survey on 9 September 2004, working under the authority of Arizona Antiquities Act Blanket Permit No. 2004-005bl (Arizona State Museum Accession No. 2004-0817). R. Brooks Jeffery, a historic preservation specialist and architect, conducted the architectural assessment. The project area contains the historic Ghost Ranch Lodge (AZ BB:9:393 [ASM]), built between 1941 and 1974. The Lodge meets eligibility requirements for the National Register of Historic Places for its role in the expansion of tourism in the early twentieth century and for the architectural distinctiveness of its original 1941 courtyard buildings. This report includes State of Arizona Historic Property Inventory forms for each grouping of related buildings. Because the buildings and other site elements differ in their historical and architectural significance, the property is defined as a contiguous district. It is recommended that contributing elements of the Ghost Ranch Lodge district be preserved where possible to maintain the National Register integrity of the complex as a whole. Rehabilitation of buildings can contribute to preservation by ensuring continued use of the property in an historically compatible fashion. If any contributing elements are heavily modified or removed, it is recommended that they be thoroughly documented prior to any changes. There are no indications of archaeological materials on the property. Additional project records are curated at the Arizona State Museum (ASM). PROJECT AREA LOCATION AND DESCRIPTION The project area is located in Pima County in Section 35, Township 13 South, Range 13 East on the USGS 7.5-minute topographic quad Tucson North, Ariz. (AZ BB:9 [SW]) (Figure 1). Specifically, the area consists of a 5.81-acre parcel located at 801 West Miracle Mile Road (Figure 2). For discussion purposes, all buildings on the parcel have been assigned letter designations (Figure 3). The Ghost Ranch Lodge motel is under consideration for conversion to low-income senior housing. The project development is being conducted by a private developer and partly funded under the federal HOME Investment Partnership Program with support from the City of Tucson Community Services Department and Arizona Department of Housing (ADOH).

Cultural Resources Survey of the Ghost Ranch Lodge, Tucson, Pima County, Arizona Page 8

Figure 1. Reproduction of USGS 7.5-minute topographic quad Tucson North, Ariz. (AZ BB:9 [SW]), showing location of project area.

Cultural Resources Survey of the Ghost Ranch Lodge, Tucson, Pima County, Arizona Page 9

Fifty-two of the existing 83 units will be rehabilitated for residential use as a part of this project. The remaining units will be replaced. Although there are no plans to alter the landscaping within the interior of the property, trenching for upgraded utilities may affect small plants. Building M (Figure 4) has documented structural problems and will be stabilized for use as a communal/laundry facility.

Figure 2. Aerial photograph of the Ghost Ranch Lodge property, 2001.

Cultural Resources Survey of the Ghost Ranch Lodge, Tucson, Pima County, Arizona Page 10

Demolition is planned for the newer buildings and a car shed at the rear of the property (Figure 5). Two-story buildings containing 40 new units will be constructed along the rear property line in approximately the same footprints as the demolished buildings.

Figure 3. Proposed demolition and construction plans.

Cultural Resources Survey of the Ghost Ranch Lodge, Tucson, Pima County, Arizona Page 11

Figure 4. Building M (1946-1953) yard and façade, to be stabilized.

Figure 5. Principal façade of Building S (1953-1967), one of the modern buildings along the rear property line to be replaced with 2-story units.

Cultural Resources Survey of the Ghost Ranch Lodge, Tucson, Pima County, Arizona Page 12

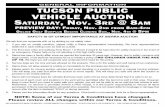

The Holiday Service Station building (Figure 6) will be addressed as part of a separate project. The hotel lobby and restaurant building (Figure 7) will be demolished. The original motel sign, attached to the lobby, will also be removed (Figure 8). A parking lot will then be created in the northwestern corner of the property. Plans indicate that a newer motel sign, located further to the east, will remain. Existing buildings that will not be demolished will be extensively remodeled and brought up to current building codes. These include the 1941 buildings that formed the original motel courtyard (Figure 9). All were designed by architect Josias Joesler. Existing carports, which are open at the rear of the units, will be closed in to create additional bedrooms, but decorative wooden screening that forms part of the front elevations will be retained (Figure 10). A wooden addition at the rear of Building G will be replaced with a new L-shaped addition with a compatible roof. With the exception of the enclosed carports and the rear of Building G, the exterior elevations of the buildings, including door and window openings, will remain unchanged. A new single-story residential building (Building M) will also be constructed immediately behind Building B. Two “Joesler-like” buildings and seven others that were constructed in the 1940s and early 1950s will also be left in place and remodeled. Rehabilitation of all standing buildings will involve the replacement of existing electrical and plumbing systems. Some interior features of the units, including ceiling fans, will be retained. These buildings require extensive rehabilitation to replace dry-rotten beams and rafters.

Figure 6. Holiday Service Station (1950).

Cultural Resources Survey of the Ghost Ranch Lodge, Tucson, Pima County, Arizona Page 13

Figure 7. Motel lobby, restaurant, and office building (Buildings R and T) to be demolished.

Figure 8. The Ghost Ranch Lodge sign, featuring the artwork of Georgia O’Keefe, to be removed.

Cultural Resources Survey of the Ghost Ranch Lodge, Tucson, Pima County, Arizona Page 14

Figure 9. Original 1941 Ghost Ranch Lodge courtyard area, lined with Joesler-designed buildings to be retained.

Figure 10. Joesler-designed Buildings E and F (1941), showing carport screening to be retained.

Cultural Resources Survey of the Ghost Ranch Lodge, Tucson, Pima County, Arizona Page 15

The Miracle Mile right-of-way could eventually be extended per Arizona Department of Transportation standards into what is now motel property. A new decorative masonry and wrought iron wall will be constructed on the Miracle Mile side of the residential buildings. The sides and rear of the property will be fenced, and existing vegetation filled in for screening. Gates will be installed on the front and sides of the property to restrict access. Area of Potential Effects (APE) refers to the “geographic area or areas within which an undertaking may directly or indirectly cause alterations in the character or use of historic properties, if any such properties exist” (36 CFR 800.16[d]). The APE for this project includes the footprint of the project area (for any archaeological remains that may be present), all standing historic buildings or structures within the property that will be directly modified, and the motel complex as a whole. ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING OF THE PROJECT AREA The project area is located within the bajada zone of the Tucson Basin. The area has been fully developed since the Historic Period, but once supported vegetation typical of the Arizona Uplands subdivision of the Sonoran Desert Scrub series (Hansen 1996). The elevation of the project area is approximately 2,340 feet above sea level. CULTURAL BACKGROUND OF THE PROJECT AREA The history of the Southwest and the Tucson Basin is marked by a close relationship between people and the natural environment. Environmental conditions have strongly influenced subsistence practices and social organization, and social and cultural changes have, in turn, made it possible to more efficiently exploit environmental resources. Through time, specialized adaptations to the arid region distinguished people living in the Southwest from those in other areas. Development of cultural and social conventions also became more regionally specific, and by A.D. 650, groups living in the Tucson Basin can be readily differ-entiated from those living in other areas of the Southwest. Today, the harsh desert climate no longer isolates Tucson and its inhabitants, but life remains closely tied to the unique resources of the Southwest. The chronology of the Tucson Basin is summarized in Table 1. Paleoindian Period (11,500?-7500 B.C.) Archaeological investigations suggest the Tucson Basin was initially occupied some 13,000 years ago, a time much wetter and cooler than today. The Paleoindian period is characterized by small, mobile groups of hunter-gatherers who briefly occupied temporary campsites as they moved across the countryside in search of food and other resources (Cordell 1997:67). The hunting of large mammals, such as mammoth and bison, was a particular focus of the subsistence economy. A Clovis point characteristic of the Paleoindian period (circa 9500 B.C.) was collected from the Valencia site, located along the Santa Cruz River in the southern Tucson Basin (Doelle 1985:181-182). Another Paleoindian point was found in Rattlesnake Pass, in the northern Tucson Basin (Huckell 1982). These rare finds suggest prehistoric use of the Tucson area probably began at this time. Paleoindian use of

Cultural Resources Survey of the Ghost Ranch Lodge, Tucson, Pima County, Arizona Page 16

Table 1. Periodization and chronology of the Santa Cruz Valley-Tucson Basin prehistory.

Periods Phases Date Ranges Historic American Statehood American Territorial Spanish and Mexican

A.D. 1912-present A.D. 1856-1912 A.D. 1697-1856

Protohistoric A.D. 1450-1697 Hohokam Classic Tucson

Tanque Verde A.D. 1300-1450 A.D. 1150-1300

Hohokam Sedentary Late Rincon Middle Rincon Early Rincon

A.D. 1100-1150 A.D. 1000-1100 A.D. 950-1000

Hohokam Colonial Rillito Cañada del Oro

A.D. 850-950 A.D. 750-850

Hohokam Pioneer Snaketown Tortolita

A.D. 650/700-750 A.D. 500-650/700

Early Ceramic Late Agua Caliente Early Agua Caliente

A.D. 350-500 A.D. 50-350

Early Agricultural Late Cienega Early Cienega San Pedro (Unnamed)

400 B.C.-A.D. 50 800-400 B.C. 1200-800 B.C. 2100-1200 B.C.

Archaic Chiricahua (Occupation gap?) Sulphur Springs-Ventana

3500-2100 B.C. 6500-3500 B.C. 7500-6500 B.C.

Paleoindian 11,500?-7500 B.C.

the Tucson Basin is supported by archaeological investigations in the nearby San Pedro Valley and elsewhere in southern Arizona, where Clovis points have been discovered in association with extinct mammoth and bison remains (Huckell 1993, 1995). However, because Paleoindian sites have yet to be found in the Tucson Basin, the extent and intensity of this occupation are unknown. Archaic Period (7500-2100 B.C.) The transition from the Paleoindian period to the Archaic period was accompanied by marked climatic changes. During this time, the environment came to look much like it does today. Archaic period groups pursued a mixed subsistence strategy, characterized by intensive wild plant gathering and the hunting of small animals. The only Early Archaic period (7500-6500 B.C.) site known from the Tucson Basin is found in Ruelas Canyon, south of the Tortolita Mountains (Swartz 1998:24). However, Middle Archaic period sites dating between 3500 and 2100 B.C. are known from the bajada zone surrounding Tucson, and, to a lesser extent, from floodplain and mountain areas. Recent investigations conducted at Middle Archaic period sites include excavations along the Santa Cruz River (Gregory 1999), in the northern Tucson Basin (Roth 1989), at the La Paloma development (Dart 1986), and along Ventana Canyon Wash and Sabino Creek (Dart 1984; Douglas and Craig 1986). Archaic period sites in the Santa Cruz floodplain were found to be deeply buried by alluvial sediments, suggesting more of these sites are present, but undiscovered, due to the lack of surface evidence.

Cultural Resources Survey of the Ghost Ranch Lodge, Tucson, Pima County, Arizona Page 17

Early Agricultural Period (2100 B.C.-A.D. 50) The Early Agricultural period (previously identified as the Late Archaic period) was the period when domesticated plant species were first cultivated in the Greater Southwest. The precise timing of the introduction of cultigens from Mexico is not known, although direct radiocarbon dates on maize indicate it was being cultivated in the Tucson Basin and several other parts of the Southwest by 2100 B.C. (Mabry 2004). By at least 400 B.C., groups were living in substantial agricultural settlements in the floodplain of the Santa Cruz River. Recent archaeological investigations suggest canal irrigation also began sometime during this period. Several Early Agricultural period sites are known from the Tucson Basin and its vicinity (Diehl 1997; Ezzo and Deaver 1998; Freeman 1998; Gregory 2001; Huckell and Huckell 1984; Huckell et al. 1995; Mabry 1998, 2004; Roth 1989). While there is variability among these sites−probably due to the 2,150 years included in the period−all excavated sites to date contain small, round, or oval semisubterranean pithouses, many with large internal storage pits. At some sites, a larger round structure is also present, which is thought to be for communal or ritual purposes. Stylistically distinctive Cienega, Cortaro, and San Pedro type projectile points are common at Early Agricultural sites, as are a range of ground stone and flaked stone tools, ornaments, and shell jewelry (Diehl 1997; Mabry 1998). The fact that shell and some of the material used for stone tools and ornaments were not locally available in the Tucson area suggests trade networks were operating. Agriculture, particularly the cultivation of corn, was important in the diet and increased in importance through time. However, gathered wild plants−such as tansy mustard and amaranth seeds, mesquite seeds and pods, and agave hearts−were also frequently used resources. As in the preceding Archaic period, the hunting of animals such as deer, cottontail rabbits, and jackrabbits, continued to provide an important source of protein. Early Ceramic Period (A.D. 50-500) Although ceramic artifacts, including figurines and crude pottery, were first produced in the Tucson Basin during the Early Agricultural period (Heidke and Ferg 2001; Heidke et al. 1998), the widespread use of ceramic containers marks the transition to the Early Ceramic period (Huckell 1993). Undecorated plain ware pottery was widely used in the Tucson Basin by about A.D. 50, marking the start of the early Agua Caliente phase (A.D. 50-350). Architectural features became more formalized and substantial during the Early Ceramic period, representing a greater investment of effort in construction, and perhaps more permanent settlement. A number of pithouse styles are present, including small, round, and basin-shaped houses, as well as slightly larger subrectangular structures. As during the Early Agricultural period, a class of significantly larger structures may have functioned in a communal or ritual manner. Reliance on agricultural crops continued to increase, and a wide variety of cultigens−including maize, beans, squash, cotton, and agave−were an integral part of the

Cultural Resources Survey of the Ghost Ranch Lodge, Tucson, Pima County, Arizona Page 18

subsistence economy. Populations grew as farmers expanded their crop production to floodplain land near permanently flowing streams, and it is assumed that canal irrigation systems also expanded. Evidence from archaeological excavations indicates trade in shell, turquoise, obsidian, and other materials intensified and that new trade networks developed. Hohokam Sequence (A.D. 500-1450) The Hohokam tradition developed in the deserts of central and southern Arizona sometime around A.D. 500 and is characterized by the introduction of red ware and decorated ceramics: red-on-buff wares in the Phoenix Basin and red-on-brown wares in the Tucson Basin (Doyel 1991; Wallace et al. 1995). Red ware pottery was introduced to the ceramic assemblage during the Tortolita phase (A.D. 500-650/700). The addition of a number of new vessel forms suggests that, by this time, ceramics were utilized for a multitude of purposes. Through time, Hohokam artisans embellished this pottery with highly distinctive geometric figures and life forms such as birds, humans, and reptiles. The Hohokam diverged from the preceding periods in a number of other important ways: (1) pithouses were clustered into formalized courtyard groups, which, in turn, were organized into larger village segments, each with their own roasting area and cemetery; (2) new burial practices appeared (cremation instead of inhumation) in conjunction with special artifacts associated with death rituals; (3) canal irrigation systems were expanded and, particularly in the Phoenix Basin, represented huge investments of organized labor and time; and (4) large communal or ritual features, such as ballcourts and platform mounds, were constructed at many village sites. The Hohokam sequence is divided into the pre-Classic (A.D. 500-1150) and Classic (A.D. 1150-1450) periods. At the start of the pre-Classic, small pithouse hamlets and villages were clustered around the Santa Cruz River. However, beginning about A.D. 750, large, nucleated villages were established along the river or its major tributaries, with smaller settlements in outlying areas serving as seasonal camps for functionally specific tasks such as hunting, gathering, or limited agriculture (Doelle and Wallace 1991). At this time, large, basin-shaped features with earthen embankments, called ballcourts, were constructed at a number of the riverine villages. Although the exact function of these features is unknown, they probably served as arenas for playing a type of ball game, as well as places for holding religious ceremonies and for bringing different groups together for trade and other communal purposes (Wilcox 1991; Wilcox and Sternberg 1983). Between A.D. 950 and 1150, Hohokam settlement in the Tucson area became even more dispersed, with people utilizing the extensive bajada zone as well as the valley floor (Doelle and Wallace 1986). An increase in population is apparent, and both functionally specific seasonal sites, as well as more permanent habitations, were now situated away from the river; however, the largest sites were still on the terraces just above the Santa Cruz. There is strong archaeological evidence for increasing specialization in ceramic manufacture at this time, with some village sites producing decorated red-on-brown ceramics for trade throughout the Tucson area (Harry 1995; Heidke 1988, 1996; Huntington 1986). The Classic period is marked by dramatic changes in settlement patterns and possibly in social organization. Aboveground adobe compound architecture appeared for the first time,

Cultural Resources Survey of the Ghost Ranch Lodge, Tucson, Pima County, Arizona Page 19

supplementing, but not replacing, the traditional semisubterranean pithouse architecture (Haury 1928; Wallace 1995). Although corn agriculture was still the primary subsistence focus, extremely large Classic period rock pile field systems associated with the cultivation of agave have been found in both the northern and southern portions of the Tucson Basin (Doelle and Wallace 1991; Fish et al. 1992). Platform mounds were also constructed at a number of Tucson Basin villages sometime around A.D. 1275-1300 (Gabel 1931). These features are found throughout southern and central Arizona and consist of a central structure that was deliberately filled to support an elevated room upon a platform. The function of the elevated room is unclear; some were undoubtedly used for habitation, whereas others may have been primarily ceremonial. Building a platform mound took organized and directed labor, and the mounds are believed to be symbols of a socially differentiated society (Doelle et al. 1995; Elson 1998; Fish et al. 1992; Gregory 1987). By the time platform mounds were constructed, most smaller sites had been abandoned, and Tucson Basin settlement was largely concentrated at only a half-dozen large, aggregated communities. Recent research has suggested that aggregation and abandonment in the Tucson area may be related to an increase in conflict and possibly warfare (Wallace and Doelle 1998). By A.D. 1450, the Hohokam tradition, as presently known, disappeared from the archaeological record. Protohistoric Period (A.D. 1450-1697) Little is known of the period from A.D. 1450, when the Hohokam disappeared from view, to A.D. 1697, when Father Kino first traveled to the Tucson Basin (Doelle and Wallace 1990). By that time, the Tohono O'odham people were living in the arid desert regions west of the Santa Cruz River, and groups that lived in the San Pedro and Santa Cruz valleys were known as the Sobaipuri (Doelle and Wallace 1990; Masse 1981). Both groups spoke the Piman language and, according to historic accounts and archaeological investigations, lived in oval jacal surface dwellings rather than pithouses. One of the larger Sobaipuri communities was located at Bac, where the Spanish Jesuits, and later the Franciscans, constructed the mission of San Xavier del Bac (Huckell 1993; Ravesloot 1987). However, due to the paucity of historic documents and archaeological research, little can be said regarding this inadequately understood period. Spanish and Mexican Periods (A.D. 1697-1856) Spanish exploration of southern Arizona began at the end of the seventeenth century A.D. Early Spanish explorers in the Southwest noted the presence of Native Americans living in what is now the Tucson area. These groups comprised the largest concentration of pop-ulation in southern Arizona (Doelle and Wallace 1990). In 1757, Father Bernard Middendorf arrived in the Tucson area, establishing the first local Spanish presence. Fifteen years later, the construction of the San Agustín Mission near a Native American village at the base of A-Mountain was initiated, and by 1773, a church was completed (Dobyns 1976:33). In 1775, the site for the Presidio of Tucson was selected on the eastern margin of the Santa Cruz River floodplain. In 1776, Spanish soldiers from the older presidio at Tubac moved

Cultural Resources Survey of the Ghost Ranch Lodge, Tucson, Pima County, Arizona Page 20

north to Tucson, and construction of defensive and residential structures began. The Presidio of Tucson was one of several forts built to counter the threat of Apache raiding groups who had entered the region at about the same time as the Spanish (Thiel et al. 1995; Wilcox 1981). Spanish colonists soon arrived to farm the relatively lush banks of the Santa Cruz River, to mine the surrounding hills, and to graze cattle. Many indigenous settlers were attracted to the area by the availability of Spanish products and the relative safety provided by the Presidio. The Spanish and Native American farmers grew corn, wheat, and vegetables, and cultivated fruit orchards, and the San Agustín Mission was known for its impressive gardens (Williams 1986). In 1821, Mexico gained independence from Spain, and Mexican settlers continued farming, ranching, and mining activities in the Tucson Basin. By 1831, the San Agustín Mission had been abandoned (Elson and Doelle 1987; Hard and Doelle 1978), although settlers continued to seek the protection of the Presidio walls. American Period (1856-Present) Through the 1848 settlement of the Mexican-American War and the 1853 Gadsden Purchase, Mexico ceded much of the Greater Southwest to the United States, establishing the international boundary at its present location. The U.S. Army established its first outpost in Tucson in 1856 and, in 1873, founded Fort Lowell at the confluence of the Tanque Verde Creek and Pantano Wash, to guard against continued Apache raiding. Railroads arrived in Tucson and the surrounding areas in the 1880s, opening the floodgates of Anglo-American settlement. With the surrender of Geronimo in 1886, Apache raiding ended, and the region’s settlement boomed. Local industries associated with mining and manufacturing continued to fuel growth, and the railroad supplied the Santa Cruz River valley with the commodities it could not produce locally. Meanwhile, homesteaders established numerous cattle ranches in outlying areas, bringing additional residents and income to the area (Mabry et al. 1994). By the turn of the century, municipal improvements to water and sewer service, and the eventual introduction of electricity, made life in southern Arizona more hospitable. New residences and businesses continued to appear within an ever-widening perimeter around Tucson, and city limits stretched to accommodate the growing population. Tourism, the health industry, and activities centered around the University of Arizona and Davis-Monthan Air Force Base have contributed significantly to growth and development in the Tucson Basin in the twentieth century (Sonnichsen 1982). The earliest detailed map of the project area is the Township map drafted for the United States General Land Office in 1871. By that time, the only development shown in the general area are roads running along the Santa Cruz River and “Grant Road” running north-south. The Grant Road alignment may have been the precursor to a segment of Highway 80. The advent of the automobile at the turn of the twentieth century led to an exponential increase in the number of travelers. The network of existing roads was pushed to its limit

Cultural Resources Survey of the Ghost Ranch Lodge, Tucson, Pima County, Arizona Page 21

and expansion was rapid. Tourism increased as travelers found it easier to travel between destinations that were not served by the railroad. In the early twentieth century, the federal government began funding the expansion and improvement of the highway system. The earliest accommodations along travel routes were campgrounds where travelers parked their cars and pitched a tent alongside. As automobile tourism became more popular, there was an increased demand for both private and public campgrounds. Highway 80 (Oracle Road) passed to the east of the project area, linking Tucson with Florence and Phoenix. In the 1930s, numerous “tourist courts” or “motor hotels” were built along the highway to serve tourists who were demanding increasingly comfortable accommodations. The term “motel” came into use in the 1940s as a contraction of the words motor hotel, and came to indicate lodgings where units were combined into larger contiguous buildings. Motels and tourist courts differed from hotels in that guests could come and go through separate entrances with easy access to both their car and their room. As with camping, travelers continued to sleep near their cars. Travelers on State Route 87 (later State Route 84 and Interstate 10) who wished to reach the accommodations along Highway 80 found a convenient bypass along the newly constructed Miracle Mile Road (known then as an extension of the Casa Grande Highway). Entrepreneurs quickly reasoned that lodgings along this 1.5 mile strip could serve both highways, and numerous business sprang up in the early and mid twentieth century. However, creation of Interstate 10 had the effect of reducing traffic through the area, and many businesses began to fail in the 1960s. One that stood the test of time was the Ghost Ranch Lodge. A motel was built in the project area in 1941 by William and Esther Van Scoy. Arthur and Phoebe Pack purchased the property the following year and renamed the motel the Ghost Ranch Lodge. The Lodge was not listed in city directories until the late 1940s, but Rudolph and Trinidad Reuser are listed as residents of the auto court at 801 Casa Grande Highway in 1942. The Ghost Ranch Lodge’s namesake, the Ghost Ranch, was a 23,000-acre ranch owned by Arthur Pack, located north of Santa Fe, New Mexico. Arthur Newton Pack (1893-1975) was the son of Charles Lathrop Pack, a leading figure in forest conservation. Arthur earned a bachelor’s degree from Williams College and then graduated from Harvard Graduate School in Business Administration. He served in World War I and went on to found the American Nature Association of Washington D. C., with his father. Pack served as editor for the Association’s Nature Magazine, issued from 1923 to 1959 (now absorbed into Natural History, the journal of the American Museum of Natural History). He also persuaded his father to found the Charles Lathrop Pack Forestry Foundation that eventually provided the funding to found the Arizona Sonora Desert Museum, among other things. Pack authored several books on forestry and economics. Pack purchased the New Mexico Ghost Ranch after marrying his second wife, Phoebe Katherine Finley, in 1936. Pack had been married to Eleanor Brown, and had three children with her. Phoebe and Arthur Pack had two children. In 1941, the Packs decided to open the Ghost Ranch Lodge in Tucson. They moved to Tucson permanently in 1946 to be closer to high schools for their children, but continued to spend their summers in New Mexico. The

Cultural Resources Survey of the Ghost Ranch Lodge, Tucson, Pima County, Arizona Page 22

family resided at the Lodge. Arthur Pack was an accomplished pilot and flew his own plane between his two homes. Ghost Ranch Lodge was one of the first tourist accommodations on Miracle Mile and one of the earliest motels in Tucson to welcome African-American guests. It was located on the south side of the road opposite Evergreen Cemetery. The Lodge featured single and double-unit buildings with lush landscaping, nearby parking, and kitchenettes. The resort-like atmosphere attracted both long- and short-term guests. Pack writes in his book and memoir The Ghost Ranch Story,

Ghost Ranch Lodge in Tucson prospered as a resort type of motor hotel. Our theory of wartime operation, whereby we gave special rates and reservation preference to servicemen and their wives, apparently paid off in peacetime in the number of former service families who advertised us far and wide, and returned themselves to stay while they made plans to buy houses and establish their homes in Southern Arizona (1960:57).

At first, Pack and his wife ran the business themselves. As business boomed, they hired additional desk help, but took the Sunday shift so that their employees could attend church. Later, the Packs would become active members of the Mountain View Presbyterian Church, and eventually donated much of their property to the Presbyterian Church of the United States. Pack kept meticulous diaries for most of his life. The Arizona Historical Society houses this material, including a 5-year diary for 1949 through 1953. In this diary, Pack faithfully recorded Tucson weather every day, and made occasional notes about business operations. For instance on January 2, 1951, he notes that a tile roof was added to the service station. The diaries also contain the names of many guests. The Ghost Ranch Lodge featured a distinctive skull logo on its stationary, gear, and sign (see Figure 8). The design was a gift from artist Georgia O’Keefe (1887-1986), who lived on the Ghost Ranch and gave Pack and his bride the design as a wedding gift without copyright restrictions. It is based on one of her most famous paintings of a cow skull. Georgia O'Keeffe was an American modernist artist known for her brilliantly colored paintings, including monumental depictions of flowers, adobe buildings, desert mountain panoramas and floating cow skulls against rich blue skies. She is considered one of the greatest and well-known American artists of the twentieth century. Pack collaborated with his friend William Carr in 1952 to found the Arizona Sonora Desert Museum. As president of the Charles Lathrop Forestry Foundation, Pack authorized a generous donation. He also served as the museum’s first President, and was named Tucson “Man of the Year” in 1952 for his contributions. By the time he had died in 1975, Pack had contributed $500,000 to the museum. In 1959, Pack and Carr also founded the Ghost Ranch Museum, an institution similar to the Desert Museum, located near Abiquiu, New Mexico. During his time living in Tucson, Pack was a prominent member of the business community. He served as the President of the Tucson Chamber of Commerce. He was also president of the YMCA and kick started a fundraising campaign. In 1972, he created a $1

Cultural Resources Survey of the Ghost Ranch Lodge, Tucson, Pima County, Arizona Page 23

million trust for St. Mary’s Hospital. Pack served on the Pima County Parks and Recreation Commission, and a regional park and golf course have been named after him. Phoebe Pack, who had worked to facilitate the acquisition of mental health and drug abuse services for juveniles and adults in Tucson, continued the Pack family charitable contributions after her husband’s death. In the 1980s, she provided thousands of dollars to fund exhibits at Mount Vernon as a member of the Mount Vernon Ladies Association of the Union. Pack sold the Ghost Ranch Lodge when her husband died. The Ghost Ranch Lodge originally featured 8 buildings (Building Q was originally two separate buildings) designed by Swiss architect Josias Joesler (1895-1956), arranged around a courtyard with a common area and shuffleboard court. Joesler was well known for his blending of Old World design elements with local building traditions and was a premier Tucson architect between 1928 and 1956. Original plans for the Ghost Ranch Lodge, archived at the University of Arizona, indicate that Joesler’s designs were closely followed. The builder is unknown. Like many other motor hotels of the time period, the lodgings featured parking areas adjacent to rooms. None of the post-1941 buildings at the Ghost Ranch Lodge were designed by Joesler. Figure 11 shows the construction sequence of Lodge buildings. Born in Zurich, Switzerland, Joesler and his wife traveled extensively through Europe, North Africa, and South and Central America. The two moved to Los Angeles in 1926 and were invited to Tucson by John Murphey, a developer/contractor. Murphey and Joesler collaborated on hundreds of private and public buildings beginning in 1928. Today, many Joesler homes are considered collector’s items in Tucson. The Blenman-Elm Historic Neighborhood, containing the largest cluster of Joesler-designed homes in Tucson, was recently listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Joesler also designed St. Philips-in-the-Hills, St. Michael and All Angels, Broadway Village Shopping Center, the Broadway branch of the Valley National Bank (now demolished), the Arizona Historical Society building and many homes in the Catalina Foothills Estates, Tucson Country Club, and El Encanto Estates. An automobile service station (the Holiday Service Station) was built in the northwestern corner of the Ghost Ranch Lodge property in 1950. Additional motel units were added between 1946 and 1967, according to Pima County Assessor’s Records and aerial photographs, and an enclosed cactus garden area was created that has acquired fame as hosting the tallest known boojum tree (the previous title-holder, on the University of Arizona campus, is dying). Some time between 1953 and 1967, three separate buildings were joined to form the current lobby building (now Buildings R and T) that is attached to the neon Ghost Ranch Lodge sign. Most of the new units echo the original Joesler courtyard, with attached carports and a complementary architectural style. The complex was updated in 1974, when the shuffleboard court was replaced and numerous other cosmetic changes were made. The swimming pool and Building U also date to this time. The Ghost Ranch Lodge has become a prominent landmark along Miracle Mile. Most long-time Tucson residents know of the lodge. Once known as the fanciest motel in town, it has

Cultural Resources Survey of the Ghost Ranch Lodge, Tucson, Pima County, Arizona Page 24

become famous for its resort-like atmosphere, architecture and landmark neon sign. Since the 1960s, the surrounding properties have deteriorated and the neighborhood has been troubled with criminal activity. In the 1990s, the Ghost Ranch Lodge restaurant closed due to lack of business.

Figure 11. Ghost Ranch Lodge site plan showing the sequence of building construction.

Cultural Resources Survey of the Ghost Ranch Lodge, Tucson, Pima County, Arizona Page 25

PREVIOUS ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESEARCH A records check was conducted at the Arizona State Museum and on the Internet at AZSITE. Cultural resource survey and site information reported in this section reflects records available on 3 September 2004. There are no records of previous cultural resources surveys within the project area and there are no recorded archaeological sites within or adjacent to the property. Most archaeological investigations carried out in the general vicinity of the Ghost Ranch Lodge facility have focused on the Santa Cruz River floodplain. Thirteen archaeological sites are recorded within 1 mile of the project area (Table 2). Most are habitation areas or artifact scatters with buried materials along the floodplain. None of the sites appear to encroach on the subject parcel. Table 2. Previously recorded archaeological sites within 1 mile of the project area. ASM Site No. Site Type Site Age Recording Date AZ AA:12:44 Roasting pit and artifact scatter Hohokam 6/17/1999 AZ AA:12:672 Artifact scatter Hohokam 5/24/2000 AZ AA:12:745 Habitation area Late Archaic 11/21/2003 AZ AA:12:746 Habitation area Late Archaic, Early Agricultural, Ceramic 6/16/1999 AZ BB:13:23 Burial and artifact scatter Hohokam 6/24/1999 AZ BB:13:425 Habitation area Early Agricultural, Hohokam 1/22/1997 AZ BB:9:27 Habitation Hohokam Unknown AZ BB:9:41 Road/trail Prehistoric, Historic 3/7/2000 AZ BB:9:78 Artifact scatter Hohokam 5/24/1999 AZ BB:9:222 Artifact scatter Prehistoric 6/3/1999 AZ BB:9:300 Artifact scatter Hohokam 1/22/1997 AZ FF:9:17 Road (State Route 80) Historic 1/22/1997 AZ I:3:10 Road (US Highway 89) Historic 1/22/1997

Very little has been found on the eastern terrace overlooking the river, in part because development was advanced before most of the recorded surveys took place. Table 3 lists previous cultural resource surveys conducted within 1 mile of the project area. Most of the surveys followed linear rights-of-way in previously disturbed areas. The nearest recorded site to the property is the Oracle Road alignment. It comprises segments of both State Route 80 (AZ FF:9:17 [ASM]) and US Highway 89 (AZ I:3:10 [ASM]). Elsewhere in the Tucson Basin, bajada zones were used both prehistorically and historically for resource procurement, resource processing, transportation routes, and camping. This type of activity leaves surface remains that are easily destroyed through modern activity. In 1991, a Survey and Planning Grant from the Arizona State Historic Preservation Office was used by the City of Tucson and Pima County to conduct an inventory of known Joesler/ Murphey properties. Arizona State Historic Property Inventory forms were completed for many of these properties. It was hoped that a National Register multiple property nomination

Cultural Resources Survey of the Ghost Ranch Lodge, Tucson, Pima County, Arizona Page 26

Table 3. Previous cultural resource surveys conducted within 1 mile of the project area.

ASM Project No. Project Name Survey Organization Sponsor

1955-3 Southern Pacific Pipeline Survey Southern Pacific 1979-38 Santa Cruz River Park Survey Arizona State Museum City of Tucson 1979-39 TG+E Northern Tucson Transmission Line

Survey Arizona State Museum Tucson Gas and Electric

Co. 1980-146 Grantway Gardens, West Grant Road Arizona State Museum Raymond and Elyse

Kaufmann 1980-152 Denny Dunn Neighborhood Park Survey Arizona State Museum Arizona State Museum 1980-155 Santa Cruz/SW Interceptor Project Arizona State Museum Buck Lewis Engineering 1981-53 Villa del Sol Apartments Arizona State Museum 1981-6 Sandcastle Arizona State Museum 1982-146 Estrella Norte, Stone and Glenn Area Arizona State Museum Steven Hazen 1982-207 Tucson-Apache 115 kV Transmission Line Complete Archaeological

Services & Technologies Western Area Power Administration

1983-78 Low Income Housing, Ventura East of Central Arizona State Museum City of Tucson 1985-150 Archaeological Survey of the El Rio - Starr Pass

Water Line, Tucson, Arizona Institute for American Research

R.G.A. Engineering Corporation

1987-216 Santa Cruz River: St. Mary's to Speedway, Speedway to Grant, and Grant to Fort Lowell

Institute for American Research

Pima County Transportation and Flood Control District

1987-222 U.S. Telecom Buried Fiber Optic Cable Dames & Moore U.S. Telecom 1990-173 ADOT I-10 Corridor Survey Desert Archaeology, Inc. JHK & Associates 1991-88 Archaeological Survey of Glenn-Fairview Main

Replacement Desert Archaeology, Inc. City of Tucson

Department of Transportation

1991-91 Archaeological Survey of Fairview Avenue - Grant Road to 15th Avenue Widening

Desert Archaeology, Inc. City of Tucson Department of Transportation

1994-279 Oracle-Tucson 11kV Transmission Line Western Cultural Resource Management

Western Area Power Administration

1995-330 Julian Park Survey Desert Archaeology, Inc. City of Tucson 1996-102 Grant-First Survey Desert Archaeology, Inc. City of Tucson 1996-91 Miracle Mile-Oracle Road Archaeological Research

Services Arizona Department of Transportation

1998-267 Miracle Manor Survey Desert Archaeology, Inc. City of Tucson 1999-390 Prince/Fairview NEC Professional

Archaeological Services & Technologies

Canatsey Building and Development

1999-55 Prince Road -- I10 to 1st Avenue Survey Desert Archaeology, Inc. City of Tucson 1999-587 PBNS Level 3 Fiber Optic Line SWCA Parsons Brinckerhoff

Network Services 2000-284 Moratorium Streets Survey Desert Archaeology, Inc. City of Tucson 2000-630 Demoss Petrie Substation Testing at 2501 N.

Flowing Wells Road (DPT) Old Pueblo Archaeology Canter

Tucson Electric Power Company

2000-723 AT&T NexGen/Core Project Link 3 Class 3 Survey

Western Cultural Resource Management

PF. Net Construction Corporation

2001-244 Fire Station 4 Survey Desert Archaeology, Inc. City of Tucson

Cultural Resources Survey of the Ghost Ranch Lodge, Tucson, Pima County, Arizona Page 27

Table 3. Continued.

ASM Project No. Project Name Survey Organization Sponsor 2002-37 M3 Cricket Monopole Environmental and

Engineering Consultants M3 Engineering

2003-1227 Casita Bonita II Survey Desert Archaeology, Inc. City of Tucson 2003-1281 Grant/Ft. Lowell Survey Statistical Research Pima County 2003-1433 Jacobs Park Swimming Pool Survey Desert Archaeology, Inc. City of Tucson 2003-231 Oracle Road, Prince-Miracle Mile HDR Engineering Arizona Department of

Transportation 2003-232 I-10, Miracle Mile - Oracle Highway HDR Engineering Arizona Department of

Transportation 2003-288 Balboa/Laguna Survey Desert Archaeology, Inc. City of Tucson 2003-896 Old Pascua Neighborhood Survey Desert Archaeology, Inc. City of Tucson 2003-906 La Paloma Neighborhood Center Survey Desert Archaeology, Inc. City of Tucson

could be created for Joesler buildings. However, funding has not yet been acquired to complete and submit the nomination form. Nearly 500 properties were attributed to individual and collaborative efforts of Joesler and the Murpheys, of which approximately half remain today. In the inventory, The Ghost Ranch Lodge was identified as a Joesler designed property (ID No. 248). However, an inventory form was not completed for it. Only archival research and a quick field check were carried out. Records indicate that the only other motor inn constructed by Joesler in Tucson or Pima County is the Downtown Motor Hotel or Downtown Inn, located at 383 South Stone Avenue. It was also constructed in 1941. However the design of the Downtown Inn differs greatly from the Ghost Ranch Lodge in that it is comprised of a single U-shaped building. SURVEY METHODS AND RESULTS Initial field survey of the project area was conducted on 9 September 2004 by Allison Diehl. The entire property was inspected on foot and all exposed ground surfaces were checked for artifacts or other signs of buried archaeological materials. Ground visibility was poor because most areas are landscaped or paved. No indications of buried cultural materials were found. Because the standing architecture on the property was obviously historical in age and had good integrity, the property was assigned Arizona State Museum archaeological site number AZ BB:9:393 and an AZSITE site card was created for the property (Appendix A). In addition, consultations were initiated between the developer, the City, and R. Brooks Jeffrey of the University of Arizona School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture. Jeffrey was contracted to complete an architectural assessment of the property and to complete State of Arizona Historic Property Inventory forms (Appendix B).

Cultural Resources Survey of the Ghost Ranch Lodge, Tucson, Pima County, Arizona Page 28

SIGNIFICANCE ASSESSMENT National Register of Historic Places The National Register of Historic Places (National Register) is the nation's inventory of historic sites. It was established after the passage of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 to promote preservation and study of historic resources. Most projects involving federal agencies, federal land, or federal funds require evaluation and mitigation of their impacts on properties eligible for the National Register. In addition, many state and local laws, ordinances, and regulations require similar evaluations. In order for a property to be listed in the National Register, it must meet integrity requirements and at least one of four significance criteria. These criteria are summarized in Table 4. An important aspect of significance is a property's historic context (cultural affiliation and dates of use). If a historic context cannot be established, or if the property cannot be shown to be significant within its historic context, then it does not meet eligibility requirements for the National Register. Furthermore, except in special circumstances, properties must be at least 50 years old to be considered for inclusion in the National Register. Table 4. National Register eligibility criteria (Code of Federal Regulations, Title 36, Part 60). The quality of significance in American history, architecture, archeology, and culture is present in districts, sites, buildings, structures, and objects that possess integrity of location, design, setting, materials, workmanship, feeling, and association, and: A. That are associated with events that have made a significant contribution to the broad pattern of our

history; or B. That are associated with the lives of persons significant in our past; or C. That embody the distinctive characteristics of a type, period, or method of construction or that

represent the work of a master, or that possess high artistic values, or that represent a significant and distinguishable entity whose components may lack individual distinction; or

D. That have yielded, or may be likely to yield, information important in prehistory or history. Significance of the Ghost Ranch Lodge Because the Ghost Ranch Lodge contains numerous buildings that differ in construction date, construction style, and integrity, it is treated here as a district (Figure 12). A National Register district is defined as a “grouping of sites, buildings, structures, or objects that are linked historically by function, theme, or physical development or aesthetically by plan” (Townsend et al. 1993:9). Elements within a district are generally defined as contributing or non-contributing. In order for an element to be considered contributing to a National Register district, it must: 1) date to the period of significance for the property; 2) relate to the documented significance of the property; and 3) possess historical integrity. For the purposes of completing Arizona Historic Property Inventory forms, nine separate sites have been defined within the Ghost Ranch Lodge based on construction episodes, function, and relationship (Appendix B).

Cultural Resources Survey of the Ghost Ranch Lodge, Tucson, Pima County, Arizona Page 29

Criterion A The Ghost Ranch Lodge Historic district, built between 1941 and 1974, is one of the longest continuously operated motels in the Tucson metropolitan area, and it helped to break the color barrier in Tucson lodgings during and after World War II. It is historically significant within the context of tourism and community development in Tucson in the early twentieth century. Its character-defining features include the complex’s use of courtyards to delineate

Figure 12. Contributing and non-contributing elements of the Ghost Ranch Lodge district.

Cultural Resources Survey of the Ghost Ranch Lodge, Tucson, Pima County, Arizona Page 30

pedestrian spaces surrounded by detached or semi-detached dwelling units. Vehicular access to the dwelling units is clearly distinguished from the pedestrian/recreational use of the complex. Another character-defining feature of the Ghost Ranch Lodge Historic district is the level of amenities provided to its guests, including bathrooms and kitchenettes integrated in the individual unit’s plan, an outdoor patio/courtyard space as well as recreational, food, laundry and even automobile service facilities on the site. The buildings, sign, and site layout convey the Lodge’s history as a traditional motor court that evolved into a resort-style facility without a dominant street façade. Criterion B The Ghost Ranch Lodge is indirectly associated with Georgia O’Keefe (1887-1986), one of the best known artists of the twentieth century, who created the well-known skull logo used on Lodge property and its landmark sign. O’Keefe would not have surrendered the copyright for the design lightly, and was known for being antagonistic to many of her admirers. Her love of the Ghost Ranch in New Mexico forged a unique bond with the Pack family and she probably stayed at the Ghost Ranch Lodge in Tucson. However, the indirect tie between Georgia O’Keefe and the motel property is not strong enough to warrant National Register eligibility under Criterion B. It is also difficult to make a case for the property being significant for its association with Arthur and Phoebe Pack. Although the Packs were known in Tucson for their philanthropy and dedication to environmentalism, their contribution is too recent to be evaluated for its overall impact on broader patterns of history. Therefore, the Ghost Ranch Lodge does not meet eligibility requirements for the National Register under Criterion B. Criterion C A subset of the Ghost Ranch Lodge buildings that meet eligibility requirements under Criterion A also meet eligibility requirements under Criterion C. The original motel courtyard contains well-preserved examples of the work of Josias Joesler, a premier Tucson architect in the early twentieth century. Joesler developed a significant architectural legacy for Tucson, ultimately shaping trends in local architecture and enhancing the area’s image as a resort destination (City of Tucson 1994). Numerous other Joesler buildings are listed on the National Register. The Ghost Ranch Lodge is one of only two motels designed by Joesler in Tucson. It exhibits the character-defining features associated with Joesler’s architecture, but priority was given to the inward-facing courtyard environment over the design of the individual buildings. The original 1941 motor court meets significance requirements under Criterion C because it represents the work of a master and is architecturally distinctive. Other buildings on the property that were built later do not attain this level of significance. Criterion D There is no indication of subsurface archaeological materials within the property. Furthermore, the standing structures and buildings on the property are unlikely to yield information that is significant to the history of the property or to its historic context. The property does not meet National Register eligibility requirements for Criterion D.

Cultural Resources Survey of the Ghost Ranch Lodge, Tucson, Pima County, Arizona Page 31

Integrity of the Ghost Ranch Lodge A National Register historic context study conducted for the Missouri Route 66 Survey outlines registration requirements for lodging properties along Route 66 (Snider and Sheals 2003), and provides a framework for evaluating the Ghost Ranch Lodge. To be eligible for the National Register under Criterion C, the buildings should exhibit a high integrity of design, materials, and workmanship. Original building materials should predominate. The presence of associated site features, such as historic signage, would bolster eligibility. In order to meet eligibility requirements for the National Register under Criterion A, tourist courts should be reasonably intact and recognizable to their period of significance (Snider and Sheals 2003). In addition, door and window openings, especially on principal elevations should be intact, and the property located close to a historical roadway. Minor alterations, including rear additions and superficial changes that are not overly noticeable from the street, might be permissible. The original Ghost Ranch Lodge has maintained a high level of integrity. The original feeling and setting of the courtyard areas are well preserved, and all buildings are in their original locations. The historical buildings themselves have also maintained a high level of integrity. Some interior remodeling has been carried out to modernize the units, but most retain their original rustic feel. Original window casings have been preserved, and the elevations of the oldest buildings are unchanged. Building Q, an original 1941 Joesler building, was constructed as two separate buildings that were later joined. After being remodeled, its exterior walls were stuccoed, making it distinct from other buildings in the courtyard grouping. However, sufficient original design elements remain to make it a recognizable part of the original motor court. Another Joesler building (Building G) has had its carport filled in, but the overall ambience created by the arrangement of buildings around the courtyard has been maintained. The alteration of the carport also underscores the history of the property as it changed from a traditional motor court into accommodations for longer-term use. The proximity of the car to the motel unit became less important over time, as the construction of a 1950 car shed to the rear of the original motel courtyard attests. Only two of the contributing elements of the Ghost Ranch Lodge district are structures (others are “buildings”). They are the 1950 car shed (Building W), and the original sign. The neon Ghost Ranch sign featuring the O’Keefe skull insignia is approximately 50 years old. It has been kept in good repair and used continuously until the facility ceased operations in April 2005. Building M (1946-1953) has been noted by the developer as having very low structural integrity, due to problems that have developed with its foundation. Left un-stabilized, the National Register integrity of the building may deteriorate. Definitively non-contributing elements of the Ghost Ranch Lodge district include the heavily modified lobby and restaurant (Buildings R and T), and buildings constructed along the rear property line between 1953 and 1967. The lobby has been extensively remodeled in

Cultural Resources Survey of the Ghost Ranch Lodge, Tucson, Pima County, Arizona Page 32

both the late historic and modern periods, obscuring any remnant of the original three buildings that were combined to form it. The rear buildings cannot be confirmed as older than 50 years of age, their construction is distinct from the rest of the Lodge, and they possess little architectural significance. The Ghost Ranch Lodge complex as a whole remains strongly associated with the Miracle Mile hotel strip, although some of the nearby businesses no longer serve the tourist trade. The lush foliage that has enclosed the facility from early in its history has helped to retain good integrity of feeling as resort lodging; the Ghost Ranch Lodge today would probably still be recognized by both Josias Joesler and Arthur Pack despite existing modern intrusions and alterations. ASSESSMENT OF PROJECT EFFECT The Ghost Ranch Lodge is comprised of multiple buildings and features. As a whole, the majority of the complex is historically significant under National Register Criterion A, and any changes to components of the property should be evaluated in terms of their effect on the whole. The original 1941 motor court portion of the property is also eligible for the National Register under Criterion C for its architectural merit. Any change that threatens the National Register eligibility of the property under either Criterion A or C would be considered an adverse effect. Criterion A As planned, the proposed project will involve both direct and indirect impacts on the Ghost Ranch Lodge. Several contributing elements will be demolished or rehabilitated, and the current streetscape will be modified. New elements to be added to the district include two-story residential buildings, storage and utility buildings, and a new parking area. In addition, the landmark motel sign will be removed. All of these changes affect the integrity of the district as a whole. The Holiday Service Station building is functionally related to the Ghost Ranch Lodge as a motorist service. The construction of an automobile service station on the property in 1950 was intended to attract and serve customers. The building was constructed in a style that is visually compatible with the motel buildings; however, the building is not integrated into the motel site plan, and is not essential to National Register eligibility of the remainder of the district. The building is excluded from consideration because it will not be affected as part of this project. Replacement of non-contributing elements Buildings to be demolished that are not contributing elements include the buildings along the rear property line (Buildings S, U, V, Y, and Z). The units are to be replaced by a bank of two story buildings in approximately the same footprint. Because these buildings do not contribute to the significance of the Ghost Ranch Lodge, and are outside of any existing

Cultural Resources Survey of the Ghost Ranch Lodge, Tucson, Pima County, Arizona Page 33

courtyard groupings, removal should not adversely affect the National Register significance of the rest of the district. The lobby/restaurant (Buildings R and T) is a non-contributing element of the Ghost Ranch Lodge because it has been heavily remodeled to obscure any remnant of the original buildings. It currently forms part of the modern streetscape. Removal of the lobby building should not affect the National Register eligibility of the other motel buildings on the site because the courtyard units face away from it. Removal of a contributing element Construction plans call for the demolition of the 1950 car shed (Building W), located at the rear of the complex. It will be removed to make way for the two-story buildings planned for that area. Although the shed is a result of the property’s evolution from a traditional motor court to resort-style accommodations, it is not a highly visible element of the district. Therefore, its removal will not detract heavily from the integrity of the district as a whole. The original Ghost Ranch Lodge sign is also slated for removal. Developers plan to remove the original neon Ghost Ranch Lodge sign because it is impractical to preserve it in place. Removal of the sign will modify the current streetscape. Because the Lodge was designed with an inward-facing courtyard design that effectively isolated the guest from the highway, its street side view served primarily to attract customers and identify the property. Eliminating the neon sign from the property entirely will affect the integrity of association and feeling of the rest of the district. Owners of the Ghost Ranch in New Mexico have been approached about housing the sign in a related historical setting. Addition of new elements One new element planned for the Ghost Ranch Lodge is a masonry and wrought iron wall along Miracle Mile. The wall is intended to provide much-needed security to future residents, but would change the open feel of the motel facility. Coupled with the removal of the landmark sign, this change may make the original function of the buildings even less apparent. A smaller addition is Building X, to be constructed at the rear of Building G. This new building will not be visible from the original 1941 courtyard. Modifications to contributing elements Plans to remodel the interiors of standing buildings and bring them up to current building codes are not expected to negatively affect National Register eligibility. The transformation of carports into additional bedrooms will be necessary to convert the motel to residential units and to accommodate enough residents. In one of the existing Joesler buildings, the carport has already been filled in. Parking will be shifted to nearby areas at the rear of the courtyards, in keeping with the historical transformation from motor court to resort. Remodeling of the buildings should enhance their preservation by allowing continued use

Cultural Resources Survey of the Ghost Ranch Lodge, Tucson, Pima County, Arizona Page 34

that is compatible with their historic function. As they stand, the buildings do not meet current codes for residential use, and it is unlikely that a motel could be profitably operated in the same facility under current conditions. Total avoidance would hasten the deterioration of the motel units. Building M is part of a courtyard grouping that dates between 1946 and 1953. The units that form the courtyard feature individually-fenced patios that face inward. Plans currently call for the conversion of Building M from a residential unit to a communal building and laundry area. Summary Construction plans call for modifications that will affect the integrity of the Ghost Ranch Lodge district. However, the changes have been planned to minimize the overall impact on the complex. The only character-defining feature that will be directly affected is the neon sign. However, although the alterations are considered negative impacts, the district as a whole should retain National Register eligibility of the district under Criterion A. Criterion C Substantial changes in appearance to the Ghost Ranch Lodge property within the original motel courtyard would threaten its National Register eligibility under Criterion C. However, no elevation changes are proposed for inward-facing sides of the Joesler buildings. The only planned exterior modification is the enclosing of rear carports to create additional bedrooms. Transparency of the existing wooden screening in the carports will be maintained by leaving a gap between the screens and addition walls. It is not anticipated that the addition of second story buildings outside the courtyard will substantially change the character of the original courtyard. Furthermore, no changes are proposed for landscaping and common areas. Therefore, the project as planned should retain the National Register eligibility of the 1941 Joesler buildings under Criterion C. RECOMMENDATIONS The Ghost Ranch Lodge is a historically significant site that meets National Register eligibility criteria as a district. It is privately owned and, because of changes in the surrounding neighborhood and the tourism industry, is no longer profitable as a motel. Rehabilitation of the site into a residential facility should contribute to its preservation. Stabilization and modernization of standing units will improve their condition and insure continued use in a historically compatible fashion. All parties contributing to this project have been very sensitive toward the preservation of this site. It is recommended that a National Register nomination be submitted for the Ghost Ranch Lodge district. If historic tax credits are sought for contributing elements of the district, then long-term preservation of the buildings will be more likely.

Cultural Resources Survey of the Ghost Ranch Lodge, Tucson, Pima County, Arizona Page 35

Any changes to contributing elements of the Ghost Ranch Lodge district should follow the Secretary of the Interior Standards for Rehabilitation (36 CFR 67) (Table 5) as closely as practical. As planned, the proposed undertaking should not threaten the Criterion C National Register eligibility of the original Joesler courtyard buildings. It is also recommended that the historic streetscape and contributing elements to be demolished or removed from the property be documented with scale drawings and photographs. Photography undertaken for this assessment and drawings created by architects working with the developers should be valuable in this effort. Finally, the neon Ghost Ranch Lodge sign should be documented and removed to a location where it will be preserved.

REFERENCES CITED

Cordell, Linda 1997 Archaeology of the Southwest. 2nd ed. Academic Press, New York. Dart, Allen 1984 Archaeological Site Significance Evaluations for Cienega Ventana Project. Technical Report

No. 84-8. Institute for American Research, Tucson. 1986 Archaeological Investigations at La Paloma: Archaic and Hohokam Occupations at Three

Sites in the Northeastern Tucson Basin, Arizona. Anthropological Papers No. 4. Institute for American Research, Tucson.

Diehl, Michael W. 1997 Archaeological Investigations of the Early Agricultural Period Settlement at the Base of A-

Mountain, Tucson, Arizona. Technical Report No. 96-21. Center for Desert Archaeology, Tucson.

Dobyns, Henry F. 1976 Spanish Colonial Tucson: A Demographic History. University of Arizona Press, Tucson. Doelle, William H. 1985 The Southern Tucson Basin: Rillito-Rincon Subsistence, Settlement, and Community

Structure. In Proceedings of the 1983 Hohokam Symposium, edited by A. E. Dittert, Jr., and D. E. Dove, pp. 183-198. Occasional Paper No. 2. Arizona Archaeological Society, Phoenix.

Doelle, William H., and Henry D. Wallace 1986 Hohokam Settlement Patterns in the San Xavier Project Area, Southern Tucson Basin.

Technical Report No. 84-6. Institute for American Research, Tucson. 1990 The Transition to History in Pimería Alta. In Perspectives on Southwestern Prehistory,

edited by P. E. Minnis and C. L. Redman, pp. 239-257. Westview Press, Boulder. 1991 The Changing Role of the Tucson Basin in the Hohokam Regional System. In

Exploring the Hohokam: Prehistoric Desert Peoples of the American Southwest, edited by G. J. Gumerman, pp. 279-345. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque.

Doelle, William H., David A. Gregory, and Henry D. Wallace 1995 Classic Period Platform Mound Systems in Southern Arizona. In The Roosevelt

Community Development Study: New Perspectives on Tonto Basin Prehistory, edited by M. D. Elson, M. T. Stark, and D. A. Gregory, pp. 385-440. Anthropological Papers No. 15. Center for Desert Archaeology, Tucson.

References Cited Page 37

Douglas, John E., and Douglas B. Craig 1986 Investigations of Archaic and Hohokam Sites on the Flying V Ranch, Tucson, Arizona.

Anthropology Series, Archaeological Report No. 13. Pima Community College, Tucson. Doyel, David E. 1991 Hohokam Cultural Evolution in the Phoenix Basin. In Exploring the Hohokam:

Prehistoric Desert Peoples of the American Southwest, edited by G. J. Gumerman, pp. 231-278. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque.

Elson, Mark D. 1998 Expanding the View of Hohokam Platform Mounds: An Ethnographic Perspective.

Anthropological Papers No. 63. University of Arizona Press, Tucson. Elson, Mark, and William H. Doelle 1987 Archaeological Assessment of the Mission Road Extension: Testing at AZ BB:13:6 (ASM).

Technical Report No. 87-6. Institute for American Research, Tucson. Ezzo, Joseph A., and William L. Deaver 1998 Watering the Desert: Late Archaic Farming at the Costello-King Site. Technical Series 68.

Statistical Research, Inc., Tucson. Fish, Suzanne K., Paul R. Fish, and John H. Madsen (editors) 1992 The Marana Community in the Hohokam World. Anthropological Papers No. 56.

University of Arizona Press, Tucson. Freeman, Andrea K. L. (editor) 1998 Archaeological Investigations at the Wetlands Site, AZ AA:12:90 (ASM). Technical Report

No. 97-5. Center for Desert Archaeology, Tucson. Gabel, Norman E. 1931 Martinez Hill Ruins: An Example of Prehistoric Culture of the Middle Gila.

Unpublished Master's thesis, Department of Anthropology, University of Arizona, Tucson.

Gregory, David A. 1987 The Morphology of Platform Mounds and the Structure of Classic Period Hohokam

Sites. In The Hohokam Village: Site Structure and Organization, edited by D. E. Doyel, pp. 183-210. American Association for the Advancement of Science, Southwestern and Rocky Mountain Division, Glenwood Springs, Colorado.

Gregory, David A. (editor) 1999 Excavations in the Santa Cruz River Floodplain: The Middle Archaic Component at Los

Pozos. Anthropological Papers No. 20. Center for Desert Archaeology, Tucson. 2001 Excavations in the Santa Cruz River Floodplain: The Early Agricultural Period Component

at Los Pozos. Anthropological Papers No. 21. Center for Desert Archaeology, Tucson.

References Cited Page 38

Hansen, Eric 1996 Desert Plants for the Botanically Challenged: A Pocket Field Guide to the Plants and Plant

Communities of the Arizona Sonoran Desert. Publications in Anthropology No. 2. Center for Indigenous Studies in the Americas, Phoenix.