Computer registration of missing persons. A case of Scandinavian cooperation in identification of an...

Transcript of Computer registration of missing persons. A case of Scandinavian cooperation in identification of an...

Forensic Science International, 60 (1993) 15 - 22 Elsevier Scientific Publishers Ireland Ltd.

15

COMPUTER REGISTRATION OF MISSING PERSONS. A CASE OF SCANDINAVIAN COOPERATION IN IDENTIFICATION OF AN UNKNOWN MALE SKELETON

LEIF KULLMANa, TORE SOLHEIMb, ROBERT GRUNDIN’ and AINA TEIVENSa

aDepartment of Forensic Odontology, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm (Sweden), bSection for Forensic Odontology, Department of Pathology, Dental Faculty, University of Oslo (Norway) and cDepartment of Forensic Medicine, National Institute of Forensic Medicine, Stockholm (Sweden)

(Received June 6th, 1992) (Revision received January 3rd, 1993) (Accepted January 24th, 1993)

Summary

A case is described where the identity of an unknown body was established several years after death and despite the fact that the body was found in a foreign country. This was made possible due to the established Interpol routines and the good cooperation between the authorities involved in the Scandinavian countries. A significant role was also played by a computerized register with ante- mortem dental findings of missing Swedish citizens.

Key words: Identification; Computer; Antemortem dental register; Cooperation

Introduction

Sweden About one-thousand Swedish citizens disappear every year. Most of them

return after a few days. However, about two-hundred remain permanently miss- ing. After a month’s disappearence the police contacts the family of the missing person in order to obtain a full description of the missing person. This description includes personal characteristics such as colour of hair and eyes, height, clothes and so on. These are stored in a computer register at the police headquarters in Stockholm.

Since 1988 Swedish police have a new instruction for this interview [l]. In addition to collecting the usual police description, they also try to obtain the name of the missing person’s doctor and dentist. These are then contacted to submit all relevant medical and dental recordings to the National Institute of

Correqnondenee to: Leif Kullman, Department of Forensic Odontology, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden.

0379s0738/93/$06.00 0 1993 Elsevier Scientific Publishers Ireland Ltd. Printed and Published in Ireland

16

Forensic Medicine in Stockholm. In both Sweden and Norway there are regula- tions for all physicians and dentists to record and keep the records of their patients for 10 years according to existing laws [2,3]. All records are then filed until the person is found - dead or alive.

The medical records can be radiographs of the body or ordinary written records and laboratory investigations e.g. blood typing. This information is stored manually in a file at the institute.

Concerning the dental records, the dentists are prompted to submit all materi- al about the missing person. It can be written records, photographs, radiographs or dental casts. The dental records are then entered into a computer-based pro- gram created with a threefold aim for the Department of Forensic Odontology in Stockholm.

Our first and most modest reason to create this program was to have a tool to assist us in our daily writing of identification reports in Sweden. About two- hundred of the autopsy cases in Stockholm every year have an uncertain identity and the police asks for assistance in these cases. Writing identification reports on a typewriter has been very time consuming for the forensic odontologist. This is not necessary today - the reports can be written out by computer and laser printer.

A second reason for this programme has been to have a computer-based pro- gram to assist us in mass disaster identification. If there is a large number of victims, the identification process will be much faster if all cases can be registered, sorted and compared with the aid of a computer.

Our third and most important reason for the program has been to create a com- puter file with the antemortem dental status of missing people in Sweden. When dead bodies, without any indication of their identity are found in Sweden, as hap- pens about 20 or 30 times a year, it is possible to compare the postmortem dental findings with the antemortem information of all missing Swedish citizens. The computer file of missing persons can be searched for matching fillings or other details of the dead.

This computer-based matching is not limited to Swedish citizens who have disappeared. Scandinavian police cooperation also gives the forensic odon- tologist information about missing persons in other countries, with dental find- ings included.

The computer program is based on the new Interpol disaster victim identifica- tion forms. To date only the dental portion of the Interpol forms are computer- ised (ante- and postmortem dental records Fl, F2). Today more than two hundred missing Swedish citizens are recorded in the antemortem part of this computer base. After a record of a missing or dead person has been registered, the form can be written out by a laser printer. Information about a missing Swede can in this way be printed out and sent, together with copies of radiographs, to other countries. In the same way, information received from abroad with postmortem dental findings of an unknown dead body, can be com- pared with the antemortem dental records in our database. As a matter of fact, the search routine is exactly the same as that adopted after the autopsy of an unknown dead body at our department in Stockholm.

17

The computer helps us to select candidates with a possible match. Searching with the computer can be done on a single filling or tooth or on several teeth simultaneously. Often one rare or very characteristic filling is enough to select one or a few candidates. Finally an ordinary manual comparison by a forensic odontologist is performed.

It is important to stress, that in the end the odontologist has to inspect the can- didates and make the final decision about identity. Very often, at least when another country is involved, it is necessary to take radiographs to establish a full identity.

Norway A central register for missing persons was established at the Central Criminal

Police Bureau in Oslo in 1946 [4]. The register was computerized in 1984 and at the present time information about persons disappearing after 1975 have been registered in the computer. The register is in a mainframe under the control of the police. Nova*Status, a text retrieval program is used [5]. The registrations comprise the full Interpol form for missing persons. However, the graphic odon- togram has been omitted.

According to police instructions, when a person is reported missing during such circumstances that he may be assumed dead or otherwise when he has been missing 6 months, the police collect all information to fill in the Interpol form for missing persons. Dental records and radiographs are sent to the Section for Fo- rensic Odontology at the Dental Faculty in Oslo for transcription to the Interpol form and for coding with used codes for computerization. Later police personnel type the information into the computer and the original record and radiographs are filed with the case at the Central Criminal Police Bureau. Also information about a number of foreign missing persons has been entered into the computer.

When an unidentified body is recovered a full description of the teeth on the Interpol form for dead persons is made by a forensic odontologist. Bitewing or full mouth radiographs are taken. With this description the police search their missing person’s file for possible matches.

If they feel they have got the right person the Interpol form together with the original dental record and radiographs are forwarded to the forensic odon- tologist for final dental conclusion. If the identity can be established, approval by the Identification Commission has to be obtained. This commission was established permanently in 1975 and is also under the jurisdiction of the Central Criminal Police Bureau. In addition to mass disasters, single cases where identi- fication is especially difficult are decided by the Identification Commission [6]. Such cases occur when fingerprint identification is not possible.

If the missing person cannot be found in Norway, information about the body is sent directly to the police in the other Scandinavian countries and through In- terpol to other countries. In such cases a complete translation of the dental infor- mation in the form to English is made by a forensic odontologist. Unfortunately, no standard international system for dental description exists, not even between the Scandinavian countries, making special translation and coding necessary for cross-referencing.

18

Case report

In the autumn 1989 a skeletalized body was found outdoors in southwest Nor- way. The body was lying hardly discernible under a tree and on a branch was found a rope arranged as a noose. According to the preliminary forensic medical and police investigations the person had committed suicide by hanging himself at least 2 years earlier. When the soft tissues had undergone complete putrefac- tion the body had fallen down. There were no clothes or other personal belong- ings around or on the body which could give the police any clue to the identity.

The autopsy was made at the department of Forensic Medicine in Oslo. Since no soft tissues were left on the body it became a very rough autopsy. To get as much information as possible of the body an anthropologist was asked to partici- pate in the examination. They concluded that it was the body of a middle aged man. No signs of damages could be discovered on the body. A forensic odon- tologist (T.S.) made a postmortem dental examination. The registrations on the Interpol form reached Interpol in Stockholm (Fig. 1). Interpol in Stockholm routinely forwarded a copy of the message to the National Institute of Forensic Medicine in Stockholm. Among several restorations in the mouth the forensic odontologist in Stockholm (A.T.) could see a characteristic goldcrown in tooth 36. A computer search among missing Swedish citizens with exactly this kind of crown was made and two possible candidates were found. These two were manually examined and one of them had dental records that matched rather well, except in one tooth. The missing person had an intact 45 (Fig. 2) while the postmortem findings of the skeleton showed an occlusal filling in the same tooth.

This discrepancy could be explained and was no contradiction to identity [‘7], since the antemortem findings were based on records from the late 1970s and the filling could have been made later by some other dentist. Our matching, miss- ing person was a member of the military who had disappeared in Stockholm 1983 while working as a captain in a military camp southwest of the city. When a definite identification was secured the police contacted his family who related that shortly before his disappearance the subject had said, that he would go away and commit suicide and make sure that nobody would ever find him.

The antemortem records for this individual had been obtained by our institute in 1985, before the installation of our dental computer base, when we were work- ing with two other cases of unidentified bodies. Both bodies proved to have other identities and all dental records including radiographs of the captain were returned to the military camp. Subsequently, as the antemortem dental records for this officer were registered in the computer the only information to hand was our own recorded dental findings, none of the original material.

We found this to be an important case with two countries involved and because of the minor discrepancies in the ante- and postmortem recordings we decided in 1989 that a reliable radiographical identification was necessary. We therefore contacted the captain’s former employer and requested the dental records again, including radiographs. However, as it was now four years later and over ten years after the last treatment they had difficulty in locating them, but promised to make an effort.

19

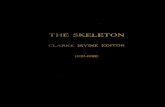

VICTIM IDENTIFICATION FORM F2 DEAD BODY

Nature of disaster: No: ----_---__-____-- Place of disaster: 33X ““know”

------------__-- Dateof examination: m Day ( Month m yew MaIS

cl FBfll&

86 1 DENTAL FINDINGS

51-11 Tom alveol (missing pm) Tom alveol (missing pm) 21-61

52-12 Tom alveol (missing pm) Tom alveol (missing pm) 22-62

53-13 s. s. 23-63

54-14 s. Tom alveol (missing pm) 24-64

55-15 s. s. 25-65

16 FamMOL F am M 0 L. 26

17 F am 0. F am M 0. 27

Cv&&vl?~~&~~Ux~~~2~

RIGHT LINGUALLY LEFT

rnMuwBMqn@~gBBB~~ 46 47 46 45 LL

4 L3 il

Al"* J 34 35 36 37 30

46 s. F am Od. 38

47 am M 0. F am 0, M L fraktur 37

46 FamMODV K G F am M @t-k farge-rotfylt? 36 65-45 F am Od. Tom alveol (missing pm) 35-75

84-44 S. S. 34-74

03-43 S. S. 33-73

62-42 s. s. 32-72

81-41 S. S. 31-71

87 Specificdescription of crowns, brldgsrand Gullkrone pa 36. dentvres (goldcrown 36)

Fig. 1. The dental part of the victim identification form arriving to Interpol in Stockholm from Oslo (Norwegian version).

Meanwhile we concentrated on our antemortem medical records in the cap- tain’s file. These showed that he had two toes amputated and there were also some skeletal radiographs, of the chest and right knee joint. A medical descrip- tion was put together (R.G) and sent together with the radiographs to Oslo. Included in this message was information on height, hair colour, shoe size and also dental records according to our computerbase, but without any intraoral radiographs.

A radiographic identification based on normal anatomical structures is often possible by tracing the trabecular pattern in skeletal radiographs, thereby mak-

20

3 iMale n Female

DENTAL DATA ,REIIRRI\NGEDI

11 No information Intact 21 12 No information 1+ am 22 13 No information Intact 23 14 Intact Intact 24 15 Intact Intact 25 16 MOl+ am MO am 26 17 0 am MO am 27 18 No information No information 28

RIGHT LINGUALLY LEFT

48 41 46 45 44 43 42 41 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38

48 No information 1 No information (erupted 1978) 38 47 MO am 0 am .37 46 MOD am GCR (qoi dcrown) 36 45 Intact DOl+ am 35 44 Intact Intact 34 43 No information Intact 33 42 No information No information 32 41 No information No information 31

Spu‘lC dUc.0" C,o/mI, brldga and dC",Y,ea 1

Fig. 2. The dental part of the missing person form according to the computer file in Stockholm

ing pathological.changes or malformations unnecessary [&lo]. However, iden- tical radiographic projections are needed. Before identical postmortems of the knee and chest could be made in Norway, the intraoral radiographs were receiv- ed from the military camp; copies were made and sent to Oslo. Postmortem in- traoral radiographs were taken there and a full identity was established (Fig. 3). Half a year after the skeletalized body was found, it was repatriated and laid to rest in the family graveyard in Sweden.

Discussion

With increasing mobility and travel in the world today the risk of fatal acci- dents increases. There is a higher risk that deceased persons will be buried unidentified in foreign countries leaving relatives uninformed about the fate of

Fig. 3. The antemortem (below) and postmortem (upper) intraoral radiographs, with which a full identity could be established.

the individual. A case where this occurred, but which was later solved through international and professional cooperation has been described by Kullman and Cipi 1992 [9].

For many years now Interpol has handled many cases of missing people and unidentified bodies. Many of these bodies are usually in advanced stages of putrefaction or disfigurement making forensic odontology and intraoral dental and skeletal radiographs more important in identification.

In Scandinavia almost all Interpol communications about missing or dead peo- ple include dental recordings. In both Sweden and Norway there are computer databases where dental records of missing people are stored. Sometimes it can take several years before a deceased person’s body is found. If the dental and medical records haven’t been collected shortly after the disappearence they may have been destroyed by the time the body is found. This is an important reason for the need for immediate post-disappearence collection of the person’s antemortem dental and medical records, in addition to the usual police descrip- tion. The efficient establishment of the identities of bodies is a multidisciplinary team effort.

In some cases questions are raised about who should be authorized to make the

22

ante- and postmorten findings. In our opinion this can only be done by a profes- sional. A dentist must ‘translate’ the dental records received while a forensic physician must examine and evaluate the medical records. In the described case it must have been difficult for police officers to evaluate the mismatching filling in tooth 45 and a mistaken identity could easily have been made.

Even forensic odontologists can sometimes encounter communication barriers. In the post- and antemortem forms in Figs. 1 and 2 some minor discrepancies can be seen, e.g. teeth 26 and 46, which can be explained by the ever present uncertainty in antemortem materials. Only a trained professional can evaluate these discrepancies and on many occasions a radiographic identification is necessary, due to unreliable or old antemortem records. Even if the written antemortem records were up to date, when the person disappeared, some uncer- tainty is always present [7].

The principle of having all disciplines represented and cooperating is deeply rooted in the Scandinavian countries and is always used in individual Interpol identification cases and in mass disasters when the identification commissions are involved. When other non-Scandinavian countries are involved antemortem dental records of missing persons without any ‘translation’ by a forensic odon- tologist are often received. This has caused difficulties and important antemortem information has been omitted. In the same way we sometimes receive unprofessional and inaccurate descriptions of the teeth of a victim, where some layman must have made the postmortem dental findings. In the case described above it is our strong conviction that the case would have remained unsolved if forensic odontolgists had not participated or if no antemortem dental register had been available. We recommend that every forensic pathologic institution have its own consultant forensic odontologist for Interpol cases.

References

5

6

7 8 9

10

Rikspolisstyrelsen, Identifiering av forsvunna personer. MEB (mddelandebreu) ,444 (1988) 38. Allminna Tandlakarinstruktionen. Svensk Forfattningssamling 666 (1963). Forskrift om tannlegesjournal for pasient, Socialdepartementet (1983), 10 maj. F. Strem, Politiets saknetergister og dens rettsodontologiske bistand. Norsk Tunnl. Tid., 78 (1968) 117 - 122. T. Solheim, S. RQnnning, B. Hars and PK. Sundnes, A new system for computer aided dental identification in mass disasters. Forensic Sci. Int., 20 (1982) 12’7- 131. T. Solheim, Kriminalpolitisentralens faste identifiseringsgruppe og dens amodning til tan- nlegene. Norsk Tannl. Tid., 87 (197’7) 19-23. S. Keiser-Nielsen, Person Zdmtificution by Means of the Teeth, Wright, Bristol, 1980, 54 - 72. A. Neiss, Personenidentifizierung durch Rontgenstrahlen. Med. Klin., 70 (1975) 1285 - 1289 L. Kuhman and B. Cipi, International cooperation in a dental identification. J. Forensic Odonto- Stom., 10 (1992) 25-31. K.T. Evans, B. Knight and D.K. Whittaker, Forensic Radiology, Blackwell Scientific Publishers, Oxford, 1981.