Fashion, Limitation and Nostalgia: Scandinavian Place-Names Abroad

Transcript of Fashion, Limitation and Nostalgia: Scandinavian Place-Names Abroad

In : Arne Kruse and Peter Graves, eds., Images and Imaginations: Perspectives of Britain and Scandinavia,Edinburgh 2007 (:3-33), ISBN 1-874665-02-8

Fashion, Limitation andNostalgia:

Scandinavian Place-Names Abroad

Arne Kruse

When I was in the American Mid-West I was struckby the way the Scandinavian-Americans had chosencertain cultural expressions to convey theiruniqueness as a group. Cultural features with anorigin in the home countries had been reinforcedto an almost iconic status. The chosen items weresometimes surprises. Within the culinary sectionof culture the most remarkable icon was arguablylutefisk, a kind of cured fish that you would notthink would travel well – in any sense of theword. Lutefisk is cod or ling that is first salted,then dried, then nearly dissolved in strong lyebefore it is cooked to gain a jelly-likeconsistency. It is a dish that is found on theChristmas table of a few die-hard traditionalistsin Norway and Sweden. However, in the AmericanMid-West the pungent smell of lutefisk announcesbetter than any poster the way to the churchdinner or any other congregation of more that twoScandinavian-Americans. A popular bumper sticker,‘Legalize lutefisk’, announces to the world thatthis car is owned by a Scandinavian-American witha sense of humour.

The need to proclaim this, as well as the needto feel obliged to consume dubious tribal food,illustrates how important it is for many people

to feel part of a group. Apart from consciouschoices to declare one’s attachment to a factionlike the one mentioned, we all are part ofvarious social categories, patterns or groups,whether we are conscious of it or not. Thefollowing pages will argue the case that it is ofimportance to the historical linguist to takeinto consideration that emigrants form a uniquesocio-ethnic faction whose linguistic choiceswill be governed by influences that sometimes aredifferent from those they left behind in the homecountry. My concern will be how this influencesthe naming patterns and naming motives ofScandinavians who settled outside of Scandinavia.

Before any discussion of possible motivesbehind place-names it is sobering to be remindedthat place-names first and foremost are there asplace-specific linguistic tags and that this factalso concerns the motive behind the namingprocess. As George R. Stewart (1975:86) says:‘all place-names arise from a single motivation,that is, the desire to distinguish and toseparate a particular place from places ingeneral’. Any further attempt to reconstruct whatmay have been the finer motive behind the coiningof place-names is an uncertain activity. RobertM. Rennick (1984:xii) goes further:

[…] researching the naming process is, at best, adifficult undertaking. […] Since very few namersever recorded their reasons for naming, let alonethe event that led to the naming, and traditionalaccounts have always been suspect, we invariablyfind ourselves accepting, or even seeking, ex postfacto explanations.

Rennick here has in mind the mostly relatively

Scandinavian names abroad 11

young American place-names. His reminder ispainfully more relevant in a European context,with place-names of a much higher age, created intime periods with very different mind frames,values and priorities.

Having acknowledged these reminders ofprudence, it is, however, unacceptable to go asfar as to say that any attempt to unravel themotivation behind names is futile. Rennick isright to announce caution when it comes to singlenames and individual namers, but as such it is awarning that is relevant to the explanationbehind any individual’s action in the past. Whenit comes to place-names, they very often fallinto categories and form patterns that reflectseveral individuals’ onomastic behaviour ratherthan only one individual’s. My hope is that bycomparing typologically similar place-namescoined in the same language over various timeperiods and locations, we may be able to distilhow certain patterns of naming behavior canchange over time and space, and we may even beable to suggest possible reasons behind thesechanges. In order to provide ourselves with a setof tools for this task, we should first establisha few terms and concepts.

Central in the study of place-names are theterms appellative, which has a characterizingfunction, e.g. ‘town’, ‘hill’, ‘river’, and nameor proprium, which has a distinguishing function,e.g. Edinburgh, Ben Nevis, the Clyde. Somegrammarians distinguish between (pure) propria andcharacterizing names (‘karakteriserende Navne’ inDiderichsen 1962:34, 40)

Olav Beito (1986:153-4 [my translation]) says:

12 Kruse

Characterizing names are in a position betweenappellatives and pure propria. Likeappellatives they are more or lesscharacterizing the object, but as propria theyare able to distinguish it from other objectsof the same type. […]Place-names develop from characterizing namesto pure propria when the semantic link with theorigin is uncertain or broken.

The distinction between what we could also callmeaningful and non-meaningful names reminds us ofthe fact that place-names do not need to carrymeaning. Meaning is an extra quality that namesmay have but certainly not must have. The mainfunction of a name is as an address tag and assuch it is in principle irrelevant if weunderstand the semantic content of it or not. Afurther principle, however, is that names, at themoment of coining, do carry meaning. ‘Meaning’ ishere a wide concept including topographical termsas well as references to other implicationsconcerning the location which is being named. Itseems to be the case that the oldest names inScandinavia basically had to be topographicallyjustified (Pamp 1976).

The formal distinction between characterizingnames and pure propria is theoreticallyunproblematic. It leaves, however, one aspect ofthe content side of place-names untouched, namelyhow names, in addition to carrying a facultativeappellatival meaning, also may have a furtherassociative side to them. While the semantic,characterizing meaning to Edinburgh is long lost,most people will associate the name with such

Scandinavian names abroad 13

qualities as ‘capital of Scotland’ and ‘where theMilitary Tattoo takes place’ etc. Some names,more than others, have a very strong associativeaspect. It is nearly impossible to think aboutVenice without instantly imagining ‘canals’ orCairo without picturing ‘pyramids’.

Kurt Zilliacus (1975)1 recognizes this widerdefinition of what a proprium might imply, and hesuggests three components that may be attached toa name, where only the first is constituting andcompulsory and the other two are facultativesides to a name:

1. the place identifying quality2. the appellatival meaning 3. the associative side

We shall here focus on the latter two aspects ofthe proprium - more specifically the place-name -and investigate if the relative importance ofthese two possible qualities, the appellativalmeaning and the associative side, might changeover time and location. As a general rule weassume that all denominations initially will havesprung from some form of descriptive expression,where in most cases there will have been anappellatival meaning attached to the name, whichover time may or may not have been obscured – ofcourse without any affect on the maindenominative quality of the name. However,instantly or over time another aspect may beattached to a place-name. This is not attached tothe semantic, appellatival side of the name butis rather linked to the function the locationitself will have had in history, in society or inpeoples’ minds in general. Place-names with a

1 For a brief discussion in English see Zilliacus 1997.

14 Kruse

heavy associative side to them are for exampleWaterloo, Mecca, Auschwitz. Although to a Norwegian thename Eidsvoll easily reveals its appellativalreference, it is not likely that the semanticside of the name is much present in the mind ofanyone hearing this name mentioned. In most casesthe dominant side of this name will be thehistorical symbolism it carries as the placewhere the constitution of Norway was signed in1814.

The associative side of a name relates to itsfunction within the group of users of the name,and the following discussion will be concernedwith the concept of groups of name users: in thiscontext more concretely how emigrants participatein a different onomastic community and share adifferent group onomasticon2 in relation to thosewho stayed behind. An onomastically baseddefinition of a group will by its nature havemembers sharing some form of a common locality.In society, group and group affinity are relativeconcepts and so is onomastic community. Anindividual may belong to several onomasticcommunities at the same time and at differentdegrees. There will be varying degrees ofmembership of such communities in terms ofknowledge, participation and identification withthe community. For example, a Scandinavianimmigrant to North America would to a certaindegree have been able to participate in an

2 The term onomasticon, ‘list of names’, is here relatedto the place-name, the toponym, and to the community ofusers, i.e. meaning ‘the place-name inventory of a nameuser group’. This usage of the term is different toe.g. WFH Nicolaisen’s (1980b:41-2), who uses the termrelated to the individual.

Scandinavian names abroad 15

onomastic community that shared the knowledge ofmajor American cities, but he or she would nothave been a fully fledged member of thisonomastic community at the same level as a nativewho would have a much more detailed knowledgeabout the names and perhaps would have taken partin actually creating the names of the grouponomasticon. As individuals we migrate over timethrough a number of name user groups andtherefore a number of onomastica. This can beillustrated through the example of a typicalemigrant from Norway to America. If he was livingon the coast he would be likely to be from acombined fishing and farming community. Whenfishing with others, he would relate to thetopography with a specialized onomasticon usedonly at sea. When discussing matters concerningthe farm with others living there he would haveused near-horizon names only familiar to thelittle circle of people living on the farm. Withfellow farmers from the village he would havemade use of names of features they would have hada shared knowledge of, such as lakes, roads,other farms, common grazing land etc. As anemigrant on board the ship across the Atlantic hewould have had to make use of an onomasticonshared by other Norwegians on board, relatingboth to the land they had left and the land theywould arrive in, and once settled on the GreatPlains he would be taking part in establishing anew set of near-horizon names on his own plot ofland and a new onomasticon shared with his localfellow settlers. Over time, he would also havehad to communicate names with English-speakingadministrators, often involving translated orphonologically adapted names. In this way an

16 Kruse

individual’s onomastic repertoire will includethe whole range of variety which is at his or herdisposal as a member of many name user groups.The various onomastica available to us all asmembers of different user groups will each inprinciple not only have a unique inventory ofappellatives and names but also a unique namingpractice.

Fashion and analogy We often see personal names as reflexions offashion and we expect people born in a certaindecade to carry names that were popular at thattime, so that for example Norwegian femalesplumed with names like Sunniva and Cecilie are morelikely to be born after 1980 than in the 1950s.In the same way we expect brand names, names ofcompanies, shops etc. to be linguistic expressionsof changing time periods. Place-names, on theother hand, we tend to experience as separateentities without any contact to other place-names, and many people have an idea of place-names as an exceptionally conservative part ofthe linguistic system, rather timeless and abovethe fashion of the moment. This, however, this isnot the case. Just like personal names place-names or place-name types may fall in and out offashion. Conspicuous distribution patterns intime and space of place-names or place-nameelements reveal analogy or imitative naming atwork.

WFH Nicolaisen (1991:147) has rightly pointedout that there is a degree of analogy behind allnaming. However, degrees can be arranged along ascale, where at the ultimate end of the scale ofanalogy we find distribution patterns of certain

Scandinavian names abroad 17

place-names that have no factual basis in thearea they occur but are motivated solely byassociation with other place-names or place-nameelements. An essential question to pose in thiscontext is at what social level this type ofanalogy works. Is it on the level of theindividual or are there social forces behind it?Undoubtedly, WFH Nicolaisen (1980b:41-2) is rightto insist that we as individuals carry our ownonomasticon, a name inventory uniquely based onour personal histories, as I have exemplifiedabove. However, when distribution patterns andchanges over time are observed we must clearlyemphasise the social side, the onomasticcommunity. In order to establish various kinds ofsocial identity language often contains semioticsystems with a function to construct in-groupsolidarity. Slang is an easily recognisablepractise that demarcates and differentiates oneparticular social group, namely young people, ina kind of intra-generational solidarity, andlingo functions in the same way within speechcommunities formed, for instance, by certainprofessions. Although an onomasticon within agroup is not normally defined along generationalor professional lines and is not ruled by thelaws of fashion in any way similar to slang orlingo, it still can be a linguistic identitymaker which can generate in-group solidarity,normally defined along geographical terms butsometimes also along professional divisions(Kruse 1998).

Ethnologists have shown how group identity iseasily created in expatriate circumstances. In astudy of the recent influx of Norwegians in thebordering Swedish landscape of Bohuslän, Anders

18 Kruse

Gustavsson (2005) demonstrates how both theNorwegians and the Swedes experience strongidentity along the lines of ‘us’ as opposed to‘those others’. However, the Norwegianimmigrants’ ‘us’ does not necessarily include allNorwegians but rather exclusively those who haveshared the experience of being a Norwegianimmigrant to Bohuslän. This type of in-groupsolidarity could easily spur the motivation toestablish cultural and linguistic demarcationsto, in this case, Swedes, but also to Norwegiansback home, and, if transferred to onomasticallyvirgin land, we can imagine that there may exista certain motivation among settlers todifferentiate themselves from those back home,based on a feeling of a shared experience.

Focusing on the linguistic side of immigrants’culture, on the settlers as a speech community,it is evident that such a group will showdifferences from the sort of local speechcommunity they left behind. Even if settlers’communities could often consist of manyindividuals from the same region back home, therewould always be settlers from other areas,resulting in generalization or centralization ofdialect variation, as described among Norwegian-Americans by Einar Haugen (1953 II: 350-3), ormore recently among Norwegians in Spitsbergen byBrit Mæhlum (1992). In a similar way, we mustassume that dialectal features in the onomasticontend to be levelled in immigrant societies.Although it is sometimes certainly possible topoint to dialectal features in the onomasticon ofsettlers, the general tendency is that theirtoponyms are created from a blended anddialectally neutralized inventory of

Scandinavian names abroad 19

appellatives. Furthermore, in situations wheresettlers establish themselves among nativespeakers of prestigious languages, as theScandinavian settlers did in North America, therewill be borrowing of appellatives and also namingmethods from the dominant language (Kruse 1991).

Taking this perspective as the basis, we willnow discuss how Scandinavians, when they settledabroad, chose to name their new environments.Over the last 1200 years large numbers ofScandinavians have emigrated and settled new landin two distinct periods, namely during the VikingAge from c. 800-1050 and then again during themuch more recent exodus to North America, whichstarted as early as in the first half of the 17th

century but as a large scale emigration tookplace only from c. 1850-1920. A relevant questionto ask is to what degree the naming strategieswere similar in the two periods a millenniumapart. I will try to limit my task by mainlyinvestigating only a few generic elements andappellatives used in the creation of names.

Same as in ScandinaviaFirstly, it is important to remind ourselves ofthe fact that the naming done in what we, for thesake of convenience, will call the ‘colonies’,fundamentally is the same as in the homelands. Aspart of their linguistic inheritance emigrantsfrom Scandinavia will have brought with them alexicon of appellatives that could be applied tomaking names and they will have brought with theman onomasticon in the form of names of locationsthey left behind as well as a set of rules forhow to make new names. The similarities areevident especially in the first period of

20 Kruse

settlement. There may be differences infrequency, distribution patterns and composition,but only rarely are the naming elementsthemselves and the naming practices fundamentallydifferent in the colonies. In the second period,the exodus to America, both the lexicon appliedand the rules for name making are much moreinnovative. However, as we will see, many ofthese innovations are also used in Scandinavia atthe same time.

Intensely used elements in the early settledcolonies, such as býr, setr, staðir etc., are in use atthe same time in Scandinavia proper when new landis won for cultivation. Habitative elements thatare no longer productive in the homelands are ofcourse not employed in the colonies. The farmname element –vin, f., had been utilised inScandinavia earlier in the Iron Age to namelarge, centrally located farms on good soil.These names are never composed with Christianpersonal names, thus the productive life of thiselement is not likely to have stretched intoperiods with Christian influence, brought toScandinavia with Viking activities. This isconfirmed by the near total absence of theelement –vin in Scandinavian farm names abroad.3

The Viking adventus comes at a time whenindividuals are beginning to be reflected inplace-names. What may be the proud settler of anewly established farm (or possibly a later user,

3 In Shetland and Orkneys vin is found quite frequentlyin topographical names but not in habitative names(Jakobsen 1936:116-9) – a fact that indicates that themeaning ‘natural meadow’ must still have been alive atthe time of the exodus but that it was not productiveas a habitative element any longer.

Scandinavian names abroad 21

see note 5) is proclaimed both in Scandinavia andin the colonies: Ellevset, (Eilífr) in Norway, Torrisdale(Þorgísl/Þorgils) in Scotland, and in Egilsstaðir inIceland.

The increase in travel created a need for moreprecise names. In a locally restrictedneighbourhood with relatively littlecommunication with the world outside, farms cancarry names like Vík and Hlíð and still be goodnames in the sense that they are monoreferential:no other farms within the limited group of nameusers carry similar names. However, when thehorizon of users’ onomasticon widened as a resultof the Viking expeditions and the extensivesettlement that followed, the precision levelneeded to increase so that new names became asmonoreferential as possible. Adding specifics wasthe obvious method, and, although there are alsoWick (Caithness), Uig (Hebrides) and Vík (SouthernIceland) in the newly settled areas, the norm isthat new names were compounds: Reykjavík, Keflavík,Njardvík, Grindavík (all on Reykjanes, Iceland).

It may have been a general need to increasethe precision level or it may have been ananalogy arising from the practice in the coloniesthat reshaped a number of previously simplexnames in Norway. During the Middle Ages manysimplex nature names had generics fixed to them:Njót became Njótarey (before 1300), Hvínir becameHvínisfjörðr etc., and many farms that initiallycarried simplex names made up of habitativeelements of the relatively younger type: Setr,Þorp, Þveit and Ruð had specifics added to them:Grímsrud, Brattarud etc. (Rygh, Indl.:17-19).4

4 Rygh points out that as a rule we should not expect apersonal name in composition with –ruð to be the

22 Kruse

West Norwegian mountainsWhile I was working on a project aiming tocollect all the names possible in the county ofMøre and Romsdal on the west coast of Norway, weregistered the following appellatives used withinthe county for referring to various shapes ofheights in the landscape (see Hallaråker1995:166-8):

Height: høgding, berg, bjørg, fjell, høgd, ås Peaked summit: horn, nibbe, nipe, nut, nyk, pigg, pik,

snydde, tigg, tind Rounded summit: hol, holt, hovde, hø, høgd, klepp, klimp,

knatt, knoll, koll, kolt, nakk(e), skolt Rocky hill or level: benk, flå, hammar, hause, hjell,

hylle, knaus, knubb, lem, nabb, naus, nobb, pall, pell, skage,slå, snage, trapp

Ridge: hals, hei, kjøl, kvelv, leite, pall, rabb, rande, range,rank, res, ris, rim(e), rind(e), robb, rong, rør, rygg, snate,synd, vor

Standing out part of a mountain: aksel, egg, ende,hytt, nase, nos, nov

Hill: bell, haug, hol, holter, klump, knubb, knøtt, kul, tuve Slope: skråning, bakke, braut, brekke, halling, kleiv, li, side,

sla, slege, slå Edge: bard, breidd, brot, brun, bryn, kant, librun, rip, rør, tripRockface: flaug, flog, flogberg, heng, staup, stup, ufs

Similar long lists of appellatives - withlocal variations - are documented from other

founder of the farm. Following Rygh’s argument, thiswill often be the case also with the other relativelyyounger habitative elements in Norway, and we shouldbear in mind that it may well be the case also forsimilar names in the colonies.

Scandinavian names abroad 23

areas on the west coast of Norway. Some of theseappellatives are quite local, others are regardedold-fashioned and perhaps only known to oldpeople, again others can be classified as rareand unusual, but the majority of theseappellatives are alive in the sense that theircharacterising meaning is known to most people,at least to those living in the countryside andwho are in frequent contact with the topographydescribed. Used in names we here see illustratedthe term nut, m., ‘pointed top’ and koll, m.,‘rounded mountain’.

Figure 1, Freikollen, photo: Per Kvalvik

24 Kruse

Figure 2, Malmangernuten, photo: Magne Fitjar

Some mountain names are metaphoric; thedescriptive part of their semantic content isseparated and is transferred to a description ofa mountain shape. Along the coast of Norway thereare several mountains with one steep side namedwith keip, m., ‘angle-shaped oar-rest’. Likewise,hest, m., ‘horse’ is used several places, insimplex names or as a generic, for distinctlyprotruding headlands or islands, presumablycomparing the shape of the pronounced headlandwith a horse charging forward. When there is asystematic use of certain originally non-topographical terms in topographical names alongthe coast, implying certain characteristics withthe designatum, they should qualify to becategorized as appellatives. In such cases themetaphor as such is dead because it has become

Scandinavian names abroad 25

lexicalised - it has become a lexeme in its ownright; the transferred meaning concerningtopography has become so established that it isregarded as one of the meanings of the word.Several of these original metaphors which havebecome part of the inventory of appellativesrelated to shapes of mountains are transferredfrom body-parts: the descriptive element in rygg,m., ‘back-side’, is used to picture a longstretched ridge shaped like the back of ananimal; aksel, f., ‘shoulder’, describes theshoulder side of a large mountain, and horn, n.,‘horn’, designates peaked mountains similar to ahorned animal. If we were to investigate thespecific element of the names we would of coursefind even further variety, indicating shape,colour, location, ownership, vegetation, usage,etc. Even a function of the hills on the horizonas a sort of sun-dial is evident in frequentnames such as Middagshøa, (‘mid-day-hill’), andfishermen and sailors could have their own namesfor mountains when used as landmarks fornavigation (see Kruse 1998). In addition to namesof this kind, which still carry characterisingmeanings, a great number of the mountains ofcourse carry names that eventually will havebecome pure propria, i.e. over time theirsemantic content will have become opaque to theusers of the names.

The point of this brief excursion intomountain naming on the west coast of Norway is toindicate a naming tradition as varied as thelandscape it describes. Today's inventory ofmountain names is created over a time period ofthousands of years and many shifting usages,viewpoints and linguistic changes. Over time, the

26 Kruse

vocabulary creating the specific element of nameswill have changed, and appellatives will haveappeared and fallen out of fashion in the sensethat they may have been productively used tocreate names only at limited time periods.

Staffan Nyström (1988) has shown that in Daga,Eastern Södermanland, Sweden, the locals have aninventory of appellatives used for heights thatis much wider than those actively used for nameformation, and so, although we may be impressedby the modern west-Norwegian farmer’s activeknowledge of appellatives, we cannot take forgranted that all the appellatives the farmerknows will be actively used to create new place-names. One way to investigate to what extent aninventory of possible appellatives is active inthe sense that it may be applied to theproduction of new names is to examine the namingbehaviour of farmers from Vestlandet when asubstantial part of the population emigrated tonew lands twelve hundred years ago and then againone hundred and fifty years ago. There is noreason to believe that the active knowledge ofappellatives will have been less a thousand yearsor one hundred and fifty years ago, but will theemigrants’ inventory of appellatives have beenactive or productive?

Of all the possibilities that probably existedto name a mountain or hill on the west coast ofNorway during the Viking period, fjall, n., or -most frequently - the unbroken form, fell, iscompletely dominant in names of heights in theNorth Atlantic settlements. For example, in anexceptionally mountainous island like Harris inthe Hebrides there are Tangaval, Arnaval, Clettraval,etc. and only exceptionally anything different.

Scandinavian names abroad 27

In Shetland field is the principle element used inhill names: Fugla Field, Hamara Field, as in Orkneyfiold: Sand Fiold, Fibla Fiold.

There are of course many examples of creativenaming also in the colonised areas. For example,there is a Hestfjall protruding on Grímsnes inIceland, with the ‘ears’ metaphorically seen inHesteyru on the mountain in a similar way toStemshesten with Hestøra in Romsdalen, Norway (Kruse2000:61). The distinct Icelandic mountainHerðubreið5 ‘broad-shouldered’ carries a very aptdescriptive name. The mountain Herdabreida inHardanger in Norway may of course be directlycommemorated in the Icelandic name, but it isperhaps more likely that we here see the re-useof a concept, resulting in parallel names. (Iwill return to this point later in this article.)

Metaphoric naming is also found for instancein Shetland where ON keipr, m. ‘oar rest’, is usedfrequently for pointed hills, as in the parish ofTingwall where a prominent, distinctly shapedhill, which is now called Luggie’s Knowe, used to benamed Da Kebb (Smith 1992), in a mannerreminiscent of naming traditions in the west andnorth of Norway.

5 There are actually two mountains with this name in Iceland: in addition to the well-known, 1682 m. high one in the north-east, there is a less conspicuous, 812m. high Herðubreið by Eldgjá in the south.

28 Kruse

Figure 3, Luggie’s Knowe (Da Kebb), photo: AndrewJennings

It is, however, quite obvious to anyone withmore than a fleeting interest in Scandinaviannames that there are relatively few such namesfound in the areas where Scandinavians havesettled abroad. Several scholars have commentedupon the lack of onomastic variation in areaswhere the Scandinavians settled during the Vikingexpansion: in other words, the range ofappellatives applied in names abroad is limitedcompared to the range of possible appellativesthe colonizers could have made use of. WHFNicolaisen (1980a:112) has this to say aboutNorse naming in the Scottish isles:

[…] the limited number of topographical terms whichwere turned into uncomponded place names is quite

Scandinavian names abroad 29

striking. Colonists in a hurry about their namingobviously did not have the time or the inclinationto go beyond the basics in applied toponymics.

When exploring the inventory of Icelandicriver-names Finnur Jónsson almost excuses hisproject: ‘The Icelandic river names are, comparedwith e.g. the Norwegian, rather poor and somewhatmonotonous’ (1914:18 [my translation]). He findsfor instance that the large number of simplexriver names found in Norway are parallelled inIceland with only a handful of names, and thatthe regular pattern has been to name the riverafter the valley it flows through: ‘it isprobably fair to say that each valley had a rivernamed after itself’ (Jónsson 1914:18-23). OnIcelandic stream names Hans Kuhn (1966:262)observes that out of the possible west-Norwegianappellatives for ‘stream, burn’ – bekkr, gróf, lœkr –only lœkr has proved productive in the new settingin Iceland.6

The distribution pattern of bekkr, m., as anappellative and a generic, is remarkablyasymmetric. Although it is the most used term for‘(small) stream’ in Modern Norwegian it has notmade it into Modern Icelandic, nor into Scots orGaelic as a loan-word. Although bekk is a veryfrequent generic on the west coast of Norway andit does appear on the Faroe Islands, severaltimes on Shetland (Jakobsen 1936:15) and once inIceland, Kvíabekkur (Sigmundsson 1985:132), it isnearly non-existent in the other Norse colonies,

6 In addition to the modern form of those mentioned byKuhn: bekk, løk, and grov, we registered in‘Stadnamnprosjektet i Møre og Romsdal’ the appellativeskeile, kvisl, sike/sikle, veke and ed (Hallaråker 1995:169).

30 Kruse

so much so that it has almost become a litmustest-word for Danish vs. Norse settlement: wherethe element –beck appears in place-names in theBritish Isles it indicates Danish colonisation.7 Apossible explanation for this unusualdistribution may be a semantic shift in exactlythe areas on the Norwegian west coast that sawmost settlers off to Iceland and the Scottishisles. In the dialects of Sogn and northwards onVestlandet and Trøndelag the appellative bekk hasdeveloped a meaning, ‘(natural) well’, which isstill in use (NSL:87). If this innovationhappened around the Viking period it may havecreated uncertainty about the usage or limitedthe practical application of the appellative as ageneric. Interestingly, the Faroe Islands, wherebekkr is found as a generic in old names, weresettled from the southern part of Vestlandetwhere this new semantic content of bekk has notdeveloped.

Settlers in a new settingA difficulty settlers in the new lands had todeal with was to make their language relate to alandscape that could be rather unfamiliar tothem. Part of the solution was to re-semanticizeappellatives. One of the words for ‘stone’ in OldNorwegian, hraun, n., is used in a traditional wayin Scotland, in e.g. the Hebridean island nameRona, ON *Hrauney, to reflect the many boulders onthe island. In Iceland, however, hraun had to makedo as the term for the unfamiliar concept of‘lava’, used in many place-names, as in the lava-7 Complications to this pattern arise of course inareas like the north of England where beck is aproductive loan-word in the dialect.

Scandinavian names abroad 31

field Stora Hraun. One of the ON terms for ‘gully’,gjá, f., was adopted in Scotland to refer to themany steep, narrow inlets from the sea which areunusual in Norway; as in Glaisgeo, and borrowedinto Gaelic: Geodh’Ghamhainn (both Caithness).From a rather limited and semantically differentusage in Norway, these appellatives get a newlife with a new lexical meaning and are usedexceptionally frequently to form names in newsurroundings.

For the Scandinavian-American settlers amillennium later the scenario would have beensimilar in the sense that they came to alandscape that was different from what they knewfrom home. For the many who establishedthemselves on plots on the Great Plains theexperience of change must have been deep-seatedwhen they thought back on the varied topographyat home in Norway, Sweden or Iceland. Obviously,a flat, featureless, square plot of the prairiedoes not invite names in general, and thesettlers’ inherited Scandinavian onomasticon musthave been felt as fundamentally inappropriate. Inaddition, the immigrants to America settled noton virgin land, as in Iceland a thousand yearsback in time, nor among a suppressed people, ason the Scottish isles, but rather in the midst ofa dominant culture with different attitudes andvalues when it came to land, work, money andlife. This will have led to a pressure on theimmigrants’ own culture and also their language,and it helps to explain a rather dramaticrestructuring of the immigrants’ semantic systemand an extensive borrowing from the English-American lexicon (Hasselmo 1974:196-7). This isalso seen in the choice of appellatives employed

32 Kruse

to create names on the Scandinavian-Americanfarm, where fil, f., from English field, refers tothe various cultivated strips of land; Tobakksfila,Potetfila, etc., and the farm itself is referred towith the loan-word farm, m., also used in names;Olsonfarmen, Grøperudfarmen, etc. It is as if thetraditional words jorde, åker, etc. and gard, bruk, etc.are not fit to describe the dramaticallydifferent topographical and cultural conditionsthe immigrants settled into (Haugen 1953:Chapter20; Kruse 1991).

Not only lexical topographical appellativesbut also elements uniquely used in names may gainintensified use in the new surroundings. A knownand proven element that exists in Scandinavia maylocally be developed under new naming motives.The Swedish scholar Bengt Pamp (1991:159)classifies a name-giving motive as ‘analogicalaffix name-formation’ when a generic element of asufficiently high frequency achieves status asbeing particularly valuable in naming a certaintype of locality. A good example of this is theelement –by, in Old Norse -býr, m., ‘farm’, whichis found much more frequently in the EnglishDanelaw than in Denmark. With a personal name asspecific it becomes the chique way among theScandinavians to coin names for new, small,independent agricultural units in early 10th

century England. In Normandy there are c. 590names with the element –tot, in Old Norse topt, f.,‘house site’ or ‘house ruins’, i.e. many morethan in Norway and Denmark added together(Stoltenberg 1994:42-58). The element bólstaðr,‘farm’ is used rather sparingly in Norway. Onlyjust over one hundred farms carry this element,showing a significant concentration to northern

Scandinavian names abroad 33

Vestlandet. In the Norse parts of Scotland, onthe other hand, there are about 240 settlementscarrying this element, showing that it had becomea fashionable term to use in order to name farmsthat were established in the latter part of the9th century (Gammeltoft 2001:39 and 80).

InterferenceSettlers’ choice of farm name elements may showinterference from languages they have been inclose contact with, as we earlier saw examples ofin an American setting. The interference can beof two types. Firstly, a relatively little usedfarm name element in Scandinavia wins supportfrom a frequently used similar-sounding elementin the contact language. Although the element –garđr, m., ‘farm’ is used to form habitative namesin both Sweden and Norway, it is obvious that thefrequent use of –garđr in the Scandinavian namesin Russia, such as Holmgarđr and Kœnugarđr, must bemotivated by Slavic gorod ‘city’ (Kuhn 1966:264).

I believe that something similar can be behindthe so-called Grimston-hybrids in the Danelawarea. It was initially Kenneth Cameron (1971:147-63) who identified this group of names in whichhe saw a Scandinavian qualifier, usually apersonal name, and an Anglo-Saxon generic. In thename Grimston Cameron thus saw the Scandinavianpersonal name Grímr followed by the Englishelement tūn, which he found to be evidence ofbilingualism among the Scandinavian settlers andthe English natives. Since the Scandinavian wordtún, n., ‘hedged plot with farm-house’ or‘farmstead’ was not often used to form place-names, Cameron was convinced that the element wefind so productive in the Danelaw must be an Old

34 Kruse

English borrowing into Scandinavian in the area.We must, however, be open to other explanationsbehind these so-called hybrids. First, we mustallow for the possibility that personal nameslike Grímr can have survived long afterScandinavian speech in general died out, and sosuch names could easily have been coined byspeakers of English still calling each other, inan old manner, with Scandinavian names. Theother, more likely, possibility is that suchnames are pure Scandinavian creations. When it isclaimed that only a fairly low frequency makes itan unlikely candidate for name-building in thecolonies, we must tread with caution. As we haveseen, the frequency of names in the colonies candiffer significantly from what is usual in thehomeland. There is, however, very good reason tobelieve that tún was actually a productive place-name element during the early medieval period inScandinavia and Iceland (Sandnes 1997,Sigmundsson 2006). The element tun in the so-called Grimston-hybrids may, in other words, be agenuine Scandinavian naming element that wasthere as a possibility in the Scandinavianonomasticon practised on the British Isles. Itmay have become popular as an element to denote afarmstead with support from English tūn, but evenso it can be seen as a Scandinavian namingpractice.

A second type of contact interference occurswhen a totally new element without any backing inScandinavian is taken up as a productive elementamong the settlers. The Scandinavian settlers inNormandie borrowed the local habitative elementville, originally from Latin villa, and in use longbefore the Viking period. The most intensive use

Scandinavian names abroad 35

of the element, however, takes place in the 10th

and 11th centuries, when the province was understrong Scandinavian influence, typically composedwith a Scandinavian appellative, e.g. kirkja,‘church’ in Querqueville, or most usually with aScandinavian personal name, e.g. Gunnúlfr inGonneville and Ketill in Quetteville. According to JeanAdigard des Gautries (1954:375 ff.) there are 169names with –ville compounded with a Scandinavianpersonal name, and in addition 86 that may beeither Frankish or Scandinavian. The frequent useof this element indicates the influence thelocal, native language had on the incomers’choice of expressions to coin their newacquisitions.

On Scottish ground one can point to theborrowing of Gaelic àirigh which originally had themeaning ‘milking place’ but by the end of theViking Age had taken the meaning ‘uplandshieling’, so that the ærgi in Norse show a nearcomplementary distribution with the element setrto the north, on Lewis and the Northern Isles.The borrowing and complementary distributionpattern possibly relates to Somerled’s dominationfrom 1156 of exactly the area with ærgi as a Norseborrowing from Gaelic (Macniven 2006:178 and 190-2).

The analogical use of the mentioned habitativeelements in the Scandinavian settlements datingback to the Viking period does not seem to beoutside of what is factually correct. Theelements will denominate a certain type of farmand not be used for anything else. This is alsothe case when whole names turn up in thesecolonised areas in patterns which are likely tobe analogically motivated.

36 Kruse

Imitation and analogy In medieval Scandinavia there seems to be a needfor the settlers to use names that are factuallycorrect, in other words, names must reflect thetopography. Is this also the case in the newsettlements? Part of the answer to this questionis touched upon in the discussion around a groupof farm names in Iceland that have parallelselsewhere. Svavar Sigmundsson (1991) is of theopinion that names like Uppsalir and Heiðabær inIceland are not necessarily réttnefni, or factuallyaccurate names but that such names could havebeen given without considering that the semanticcontent of the name corresponded to the localityitself. Svavar thinks that the namegivers wouldhave chosen such names because they were wellknown rather than because of their semanticaccuracy. Hans Kuhn (1949:62-3) and ÞórhallurVilmundarson (1996) are of the opinion thathardly any of these names are given withoutconsidering the semantic content. Þórhallur showsfor example that the 23 farms named Uppsalir inIceland are all located high in the terrain orhigher than other farms in the vicinity(1996:401). As an element on its own –salir (pluralof –salr ‘room’) is not used to form names. Thereare, in other words, no *Neðrasalir or *Bjarnasalir.It seems, on the other hand, that the compositeuppsalir, meaning ‘up(per)+house(s)’ has become aset way to denote farms located higher than otherfarms, not only in Iceland but also in Norway(Rygh:NG I, 1897:138), where there are 40-50 suchnamed farms, and in Sweden, where there are about20. It may be that the famous Uppsala in Sweden orone of the Norwegian farms with this name are

Scandinavian names abroad 37

implicitly referred to in some or even all of theIcelandic names but as long as the new farmscarrying this name reflect the factual topographywe should not take it for granted thatcommemoration is the motive behind such names.What we know is that the denominations aresemantically transparent appellatival reflectionsof the landscape. The further motive behind thequite high frequency of these names in Icelandcan be due to a local Icelandicfashion/analogical naming practice and notnecessarily memorial naming with the famousUppsala in mind.

Figure 4, Sullom, Shetland, photo: Peder Gammeltoft

The fact that –salir is not otherwise productivein Iceland or in Scandinavia may of course beseen as evidence for the whole name having beentransferred. There are, however, parallel

38 Kruse

examples of an intensive use of compositeelements in place-names, both in Scandinavia andin the colonies. In a similar way to thecomposite uppsalir having achieved a meaning‘(farm) houses located high in the terrain’ andsystematically used to create names thatfactually express this location, the compositeelement sólheimr, m., has gained a meaning ‘sunnyhomestead’ and is behind the creation of severalnames in Norway and in the colonies. As anelement in its own right –heimr is by the start ofthe Viking period no longer productive in thecreation of farm names.8 The only time it is seenused in the colonies is in the composite sólheimrwhich is found in 11 farms on Iceland, one onShetland (Sullom) and one on Islay (Solam). Thereare also about 70 farms named Solheim (and Solemetc.) in Norway, and like their Icelandic andScottish namesakes they are mainly farms locatedrelatively high up on sunny spots and outside theearlier settlement area (Jakobsen 1936:54;Macniven 2005:495-6; NSL:415-6). It is evidentthat -heimr as an element plays a different rolein these names than it did in names from earlierin the Scandinavian Iron Age. It may be fair tosay that the stereotypically used compositeproclaims the end of the productive life for theelement heimr both inside and outside ofScandinavia.

In an almost reversed way to uppsalir, thehabitative element bólstaðr shows a curiously

8 Several farm names with –heimr are found on Shetland,for example Cauldhame < *Kaldheimr, Stuttem < *Stuttheimr, Sodom<*Suð(r)heimr. This, and the fact that vin is frequentlyused in nature names, indicates a very early, possiblypre-Viking, Norse settlement of Shetland.

Scandinavian names abroad 39

restricted, almost stereotypical usage in Norwayand a much more unrestricted application in thecolonies. In Norway there are two main specificswith which bólstaðr is compounded, namely mikill,adj., ‘large’ – used in nearly half of theNorwegian names - and heilagr, adj.,‘holy’, inmodern names typically as Myklebust and Hellebust. InScotland a much greater variety of specifics isused, as e.g. in Kirbister, Grimbister, Swanibost, Melbostand Westerbister. Peder Gammeltoft, who has analysedthe distribution of this element, explains thedifference as a form of extensive ‘imitativenaming’ in Norway, with the use of a limitednumber of set specifics attached to bólstaðr, whilein Scotland the element was adapted to a newenvironment without such a restrictive namingmotivation (Gammeltoft 2001:227 and 273-4). Theexpression ‘imitative naming’ in this context maybe associated with imitating existing names,which is probably not the case. The Icelandicbólstaður-names illustrate this. As in Norway wesee an extraordinary restriction in the use ofthis element in Iceland; there are four simplexBólstaður and there are 12 Breiðabólstaður out ofaltogether 16 mentioned in medieval sources.Svavar Sigmundsson (1996) points to the eightBreiðabólstaðr-names in Scotland and thinks theymust be the inspiration behind the Icelandicnames. This makes sense when we consider howScotland seems to have been a stop-over for manyof the Icelandic settlers en route from Norway.There is, however, no reason to believe that oneparticular Scottish Breiðabólstaðr-name iscommemorated in the Icelandic names.

In the examples mentioned with uppsalir, sólheimrand miklabólstaðr a more apt expression than

40 Kruse

‘imitative naming’ is ‘analogy’, referring moreto an unusual frequency or distribution with abasis in the onomasticon of a name user group’sunusual compositional restriction concerning theelements used to create the names, rather than asingle individual’s naming motive. However, whenit comes to what until now have been referred toas ‘elements’, I think that uppsalir, sólheimr andmiklabólstaðr ought to be regarded as compoundappellatives, as integral parts of the lexiconand with the capacity to construct place-names.Peder Gammeltoft (2001:225-7) rejects miklabólstaðras a compound appellative on the ground that itdoes not have ‘general currency throughout thespeech area while it formed part of theonomasticon’ as not one single example of*Miklabólstaðr is found in Scotland or Iceland.There is, however, no need to establish acriterion that an appellative will need to befound ‘throughout the speech area’. Such acriterion will reject any form of regional ordialectal aspect of an onomasticon, e.g. manyentries from the list of appellatives relating toheight registered from the county of Møre andRomsdal, simply because they are not foundoutside Møre and Romsdal.

As we have seen, a little used appellativalconcept in the homeland can at times be used withincreased frequency in the colonies to createboth habitative names and nature names. Threeislands in Nordland in the north of Norway, whichare or used to be attached to the mainland onlyat low tide, are called Offersøya: ca. 1430 one iswritten Orfyrisøy, in ‘classical’ ON *Órfyrisey or*Órfirisey, f., ‘tidal island’, from *ór-fjara ‘out atebb tide’ (NG XVI:60, 299, 334). There are many

Scandinavian names abroad 41

more such characteristic islands in Scotland,with a long stretch of sand, a so-called tombola,exposed as a causeway over to the island at lowtide. Accordingly, WFH Nicolaisen (1977-80:119-20) can list 30 islands from the Western andNorthern Isles with names with an origin in*Órfyrisey: Oronsay, Orfasay etc.9 Nicolaisen finds the*Órfyrisey-names the prime example of what he calls‘connotative names’, i.e. names which ‘display apredominantly associative meaning’. He says aboutthe island names that ‘the association of “tidal”must have been overwhelming compared with allother potential associations, like size, shape orcolour; it therefore produced an instancy ofnaming which would be difficult to match.’Nicolaisen argues that frequent Norse names inScotland such as Lerwick and Sandwick qualify forthis category and he thinks they will have beengiven ‘connotative names’ because those who namedthese bays will have had an instant associationabout ‘clay, mud’ and ‘sand’ respectively(Nicolaisen 1995:391).

The motivation for giving a natural feature aname corresponding to its most striking featureis not controversial, in fact it is whatonomasticians in general would agree is the mostobvious naming principle in most circumstances,and there is certainly no reason to believe thatit will not be a motive behind naming in newsettlements. However, I find there is no realground for establishing a term ‘connotativenames’ and claiming that as a naming motive it is9 From Nicolaisen’s list Orsay, Islay, should besubtracted, because it is not a tidal island andtherefore the name cannot mean this (Macniven2006:355).

42 Kruse

particularly over-represented in new settlements.The main cause of the possible over-frequency ofcertain names in the colonies is most likely tobe related to a factual difference in thetopography and how this difference wasexperienced by the settlers. If it is the casethat there is an over-representation of Sandvík-names in Scotia Scandinavica compared to the westcoast of Norway, it may simply be because thereis a higher frequency of ‘sandy bays’. Anyonefrom Vestlandet landing on Orkney or the Hebrideswill have been struck by the many bays with sandybeaches, inviting the use of names reflectingthis feature. As a name, however, Sandvík needs tobe as monoreferential as possible within acertain speech community. Thus, in spite of anumber of sandy bays on Tiree, there is only onedenotatum named Sandaig. It is an obvious name,but it can only be employed once within the usergroup onomasticon.

Names reflecting central topographicalfeatures in a landscape are, however, ofimportance in a chronological perspective. InScandinavia simplex topographical names used ashabitative names, like Vik and Dal, are in generalregarded as very old and it is likely that thisprinciple can guide us well also in theScandinavian colonisation areas (Kruse 2004).

Commemorative names in the North Atlantic?My quest to convince runs the risk of becoming adogmatic mission and I must therefore concedethat there are indeed old names that probably arecommemorative, both in Scandinavia and in theScandinavian North Atlantic. A unique examplefrom Scandinavia is the case from Västergötland,

Scandinavian names abroad 43

first considered by the Swedish scholar HugoJungner (1920). Some 30-40 km apart are twoidentical sets of the place-names Friggeråker, Lovene,Slöta, Saleby, Synnerål and Holma. Clearly the two setsof names are interrelated and one set may well becommemorating the other. (See a furtherdiscussion in Brink 1996:65-7.)

Younger in time and set in the Scandinavianexpansion area is the case indicated by HermannPálsson (1996:16-18). In central eastern Lewis inthe Hebrides are the names Leirehbagh, Eshaval, Ceoseand Lachasay, and in Iceland, in a region forwhich the Landnámabók claims firm Hebideanconnections, is the parallel set of names onneighbouring locations: Leiruvágr, Esja, Kjós and Laxá.The three first names in both sets are relativelyunusual and the parallel appearance cannot easilybe dismissed as coincidence.

A.W. Brøgger (1929:70-71) points to thesimplex Norwegian area-name Voss maybereduplicated in Uist, and the complex island-nameMostr found again in Mainland.

Also, the name Romsdal, again in Uist in theHebrides, may be the recycled valley name fromnorthern Vestlandet. Admittedly, it is difficultto come up with alternative etymologies for aname like this, but we must recognise that ourfailing to do so may also be because there is alack of old written forms of the name and theremay be unmapped sound changes from Norse toGaelic or similar shortcomings. I want tomaintain that as a naming motive commemoration islikely to have been a minor, even negligiblefactor until we reach more modern times, and thatwe should be careful not to suggest shortcutconclusions around parallel names or peculiar

44 Kruse

distribution patterns. A couple of examples willdemonstrate this.

The name Dimun forms an interesting pattern inthe North Atlantic over the area where the Norsesettled, used to denotate topography with twofeatures. The name even occurs in Norway in theform Dimna, an island with two hills, near toUlsteinvik, Sunnmøre (Nes 1989:69). The name isclearly of Celtic origin, where the di is thefeminine form of the numeral da ‘two’ and thesecond element probably linked to Irish muinn‘neck, top’.10 We don’t know the background tothis name and its distribution, nor who coined itand who spread it, but the fact that the namesprings from a language other than Norse and thatit is found in areas where Celtic slaves willhave lived makes this name unusable as an exampleof Norse naming habits in the North Atlantic.

Hermann Pálsson (1996:12) has pointed to theunusual distribution of the mountain name Hekla.The name of the famous and impressive Icelandicvolcano has several parallels in Norway, and theIcelandic and many of the Norwegian names areprobably a metaphorical comparison to ON hekla, f.‘cape’ referring to the ‘snow-caped’ summits ofthese tall, rounded mountains.11 However, the namealso appears in the Outer Hebrides, not only oncebut twice: in South Uist and in Mingulay, and inthe extremely wet and mild climate of theHebrides these comparatively small hills can

10 As far as I know, this is the only place-name inNorway which, with a degree of confidence, can beclaimed to be of Celtic origin.11 Hekla-names on rugged comb-like ridges in Norwaymight rather refer to hekle, f. ‘tool with spikes toclean flax’ (NSL:205).

Scandinavian names abroad 45

certainly not be accused of carrying anythinglike a snow-caped summit. Therefore, because theIcelandic Hekla is factually referring to a snow-caped mountain, we must assume that those whocoined the name of the volcano actually werereferring to the semantic meaning of the wordthat was used as a metaphor to make up the name.What we see in the Hebridean Hekla names, on theother hand, could possibly be nostalgic naming inthe sense that one or two of the Hekla-mountainsin Norway will have motivated those who coinedthe Hebridean names to recollect the hills fromback home in Norway. Can we, however, be sure ofthe exact meaning of the metaphoric hekla? Couldit not be that the meaning ‘cape’ could alsorefer to ‘fog’ or ‘cloud’ just as much as to‘snow’? If so, the Hebridean Hekla-names could besaid to be just as factual as the Norwegian andIcelandic names.

It may of course be the case that some ‘ready-made’, complete, uncoded names are recycled, andif so, then probably for commemorative reasons. Ido, however, agree with WHF Nicolaisen(1980a:115) who suggests mildly, thatcommemoration and nostalgia do not stand out aspowerful factors in 9th century Scotland, and thattheir effect on the creation of new nomenclatureshould not be overrated. If it was the case thatuncoded, ‘instant’ names were transplanted in amore or less systematic way from Scandinavia tothe colonies we should have expected to findnames that were old in Scandinavia at the time ofthe Viking expansion, such as those with the oldelement -vin, ‘meadow’, and old, obscure nature-names. Such names are extremely hard to find inthe North Atlantic colonies, and if we think we

46 Kruse

find them, we should be careful to claim anyunusual names with parallels in Norway astransplanted names.

The Icelanders’ unique record of the earlysettlement of their island, the Landnámabók,informs us in amazing detail where the settlerscame from and where they located their new farms.Although it only presents the background to a fewhundred settlers out of several thousand, itstill provides a snapshot of Scandinaviansettlers’ naming strategies in a nameless land.It is telling that there is not one single clearexample of a settler who named his new farm afterhis old farm in Norway (Rygh 1898:8).

A narrow doorwayThere is a remarkable lack of teophoric names inthe Scandinavian settlements in the NorthAtlantic. This area was settled by people whowere pagan, yet there is very little trace ofthis fact in the place-name material available tous. There are many pagan graves but scarcely anyindisputable names celebrating deities such asUllr, Óðinn, Þórr, Njörðr. What we do find, however, arenames warning about the supernatural, abouttrolls, as in Traligill, Inchnadamph, and Trallisker,Barra, both Scotland. It is as if the settlersmay have felt that they came to landscapesinhabited by spirits, but that the localsupernatural beings were not the gods they knewfrom their homeland. In a similar way, the namesattached to the places they knew back home appearso intimately attached to the place itself thatthey could not easily be transferred to a newsetting. Certain generics from their onomasticoncould be applied to name the new landscapes but

Scandinavian names abroad 47

it seems as if the old names themselves ingeneral were not transferable.

It is as if there is a rather narrow onomasticdoorway open to emigrants. As we have seen, evenin the homeland only parts of the livinginventory of appellatives are likely to beproductive for naming purposes. At the moment ofexodus the emigrants are victims of the fashionof the moment, especially when it comes to namingtheir newly established settlements, and,finally, they will often have to face a new typeof topography in their new homelands, atopography that may not be the same that theirvocabulary is adapted to.

In the new Scandinavian settlements in NorthAmerica this doorway appears even narrowercompared to that of their fellow emigrants amillennium earlier. Appellatives employed toproduce place-names in Scandinavian America areconsiderably fewer, fashion seems to have limitedthe choices even more and the prairie most ofthem settled on will have been very differentfrom what the settlers were used to from theirhomelands and would probably have been uninvitingto appellatives they mentally attached to thetopography back home. Even in areas with a morefamiliar landscape, only a very limited number ofgenerics is used (Kruse 1991 and Kruse 1996:260-1). Still, in one respect the more modernsettlers had a wider choice. While in the oldcolonies one really will have to look hard tofind commemorative or nostalgic names, in themore recent Scandinavian settlements in Americathis type of naming becomes the norm for largersettlements.

We observe that this shift has happened

48 Kruse

already in the first Scandinavian effort tocolonise America after the Middle Ages. Nya Swerigeor Nova Svecia was the Swedish attempt to win apiece of the colonial cake by organising asettlement along the Delaware River from 1638. Ina map called Nova Svecia, anno 1654 och 1655, drawn byPeter Lindström (Holm 1702:32), we notice,interestingly, quite a number of Indian names, wefind, as expected, descriptive names, but we alsodiscover a group of names that are new in aScandinavian setting, namely names that clearlyrefer back to places or persons in Sweden, andwith an obvious intention behind the name whichis precisely to commemorate this place or person.Peter Minuit, the Dutch leader of the Swedishexpedition, had been instructed to rename SableIsland Christina after the queen, and the merchantport to be founded at Minquas Kill in the bay ofDelaware were to be named Stockholm. Because ofbad weather they never reached Sable Island, themerchant port was given the name Christina, andStockholm was not used as a name in the new colony(Utterström 2001:63). Nevertheless, there is nodoubt about the intention to mark the territorywith linguistic Swedishness. The proud presenceof the ambitious new national power in the Balticregion is announced in names such as Nya Göteborg,Upland, Nya Korsholm, Nya Wasa and Finland. This isnaming with a mission. The colony was to beestablished with military presence, but alsothrough onomastic branding.

The Swedish effort did not succeed for verylong, neither militarily nor linguistically. Thecolony was captured by the Dutch in 1655 and noneof the Swedish names are still in use. The colonydoes, however, represent the first conscious and

Scandinavian names abroad 49

planned effort by Scandinavians to name a newlandscape with what we may call an ideologicalintention behind it.

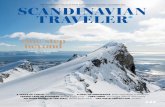

Figure 5, Extract from the map ‘Nova Svecia, anno 1654 och 1655’,drawn by Peter Lindström (Holm 1702:32).

When settlers establish themselves in a newenvironment, they form a socio-geographical unitthat in linguistic practice can have close ormore remote connections to the homeland,

50 Kruse

depending on geographical, political and economicproximity and individuals’ personal contact. Insuch relative isolation, the inventory ofappellatives that can produce names may bedifferent and so the onomasticon among colonialsettlers might follow a dissimilar course to theonomasticon in the homeland. Settlers will inother words form a linguistically defined groupwith their own set of rules for language use.Clearly defined in time and as a group thesettlers may even want to express theiruniqueness as a group, and their linguisticpractice, including their onomasticon, mayconstruct and display in-group solidarity in theway, for example, fishermen’s onomasticon does(Kruse 1998). I think this becomes clearlyvisible during the emigration to America whene.g. Swedish-American or Norwegian-Americansettlers’ conscious choice of names is used todemarcate and differentiate themselves from otherethnic groups.

The naming motive based on nostalgia orcommemoration is doubtlessly due to an increasein the importance attached to national or ethnicidentity. By the time of the great Scandinavianexodus to America in the late 19th century we cansee how the influence of the National Romanticmovement and organised schooling added new namingmotives to the register of the Scandinavianimmigrants.

Transplaced and transferred names Many of the place-names in the North Americanlandscape which indicate Scandinavian settlementor another form of link to Scandinavia arestrictly speaking not Scandinavian-American names

Scandinavian names abroad 51

in the sense that they have not been created byScandinavian speakers. Common names like Denmark,Norseville, Swede Creek, Scandinavia, and sometimesnames like Stockholm and Gothenburg, will veryoften have been given by English-speakingAmerican administrators and cartographers inorder to identify Scandinavian settlements.Swenoda Lake (Min.) was created by taking Swe+no+dafrom Swedish, Norwegian and Danish, since thearea was settled by people from all three nationsand the administration needed a characterisingname.

Many other, and often smaller Scandinavian-American settlements, however, will have beencoined by the immigrants themselves in order toestablish links to their old roots. When theFinnish name for Finland, Suomi, and a Swedishpoetic name for Sweden, Svea, is used, we can becertain that these are settlements which werenamed by the immigrants themselves, as it isdoubtful that the American administrators wouldknow such insiders’ names or expressions.

The terms transplaced and transferred names areuseful terms when discussing the naming motivesbehind the Scandinavian-American place-names(Rudnyćkyj 1952). Transplaced names are originalplace-names from Scandinavia that will have beenrecycled and put into use in order to denominatea completely new location in the new settlements.Examples of transplaced Scandinavian-Americannames are: Stockholm (e.g. Maine, SDak.), Oslo(Min.), Smolan (Kans.), Erdahl (Min.) Malmo (Min.and Nebr). The transplaced name will typically bethe name of the region, town or village whencethe immigrants originated e.g. Sogn (Min.); or itwill carry iconographic implications of

52 Kruse

historical or national importance to therespective country of origin: Eidswold (Min.),Upsala (Flor., Min. and Ont.), Vasa (Min.). In thelatter example it is not evident whether it isthe Swedish royal house Vasa or the Finnish townVasa that is being commemorated. (The Finnishtown, founded 1606, is named after the royalhouse.) Most likely it is the royal house thatlies behind the American name and the name willthen fit into a group of typically American town-names where an original surname stands alone,without a generic, as in Washington, Jefferson, and,with Swedish background, Tegner and Lindstrom.Unusually, the ‘Swedish Nightingale’ Jenny Lind ishonoured with her full name and without an addedgeneric by a town in California.

Names of persons, ideas or mythical placeswhich are adopted as place-names can beclassified as transferred names. Such names may havestrong national or ethnic implications for thesettlers or may be ‘respectful’ names taken froma Christian context or Norse pagan mythology. Themany Scandinavian-American transferred names forplaces like Gimli (Man.), Viking (Alb.), St Olaf(Iowa), are original American creations declaringa romantic link to the ethnic past in the OldWorld. A parallel cultural transfer or re-use ofthe names of figures and beings from Norsemythology and national tradition was popular inScandinavia towards the end of the 19th century -on villas, for example Breidablikk, Gimle, and socialclubhouses for young people, ungdomshus, forexample Valhall, Lidsjalv, Mjølner.

From a synchronic perspective, place-names mayhave different implications for different user-groups. To an American administrator names like

Scandinavian names abroad 53

Stockholm and Oslo were good names as theyindicated a predominantly Scandinaviansettlement, while for the Scandinavian settlersthemselves they carried what we could callnostalgic implications.

From a diachronic perspective, a staticdefinition of connotation does not accommodatethe fact that ‘meaning’ may change over time.Gimli and Voss in North America were suitableplace-names to the settlers not because of theirsemantic content but because they carry certainother useful connotations. It would have beentheir nostalgic attributes, although a secondarydevelopment, which would have made themattractive as names in a new setting. Bothtransplanted names and transferred names may thusbe said to be carriers of a secondary connotationin their new setting, namely an emotionalhistoric link to an inherited ethnic traditionand place of origin.

The Scandinavian-American names give us newinsight into a development of naming motivationthat certainly is not limited to the Scandinavianimmigrants (see Stewart 1975:118-26). In theintroduction to his book on Kentucky place-namesRobert M. Rennick (1984:xii) says:

‘[…] American place-names, including most of thosewith obviously non-English origins, are eithersignificant in terms of their meanings to thenamers or in their historical association with theplaces they identify; or else they merely identifythese places. The motivation behind an American name often

stands out as a statement in the sense that the

54 Kruse

place-name tells us more about the name-makersthat the place itself.

In modern Europe we see a similar tendency. Inplanned naming in bureaucratic settings, e.g.naming streets in newly built suburbs, a streetname like Heron Road is not very likely to referto unusual sightings of a particular bird in thearea but is rather chosen because of itsassociative hint of idyll and tranquillity – justthe benefits the house-owners hope to purchasewhen they settle in suburbia. In a similar way,the oilfields in the Norwegian sector of theNorth Sea have since the 1970s in a more or lesssystematic manner been given names from Norsemythology or Norwegian folk tales: Valhall, Norne,Troll, Smørbukk etc. The value added to such nameslies in their positive connotations to Norwegianculture although, it may be argued, it isdifficult to imagine anything further afield fromtraditional folk culture than this high-techmodern industry.

This flight over an onomastic landscapespanning more than a millennium and crossing twocontinents has, I hope, shown that namers changepriorities over time and space. In brief, wewitness a change from an onomasticon that used tobe purely descriptive to one that carries evermore extra-descriptive associations. Although weare used to thinking about place-names as anespecially conservative part of our language, theactual making of place-names as an ongoingprocess is very much influenced by changes insociety. The oldest stratum of place-names thatwe can identify in Scandinavia, those onimportant natural localities like islands andrivers, have all – as far as we know – sprung

Scandinavian names abroad 55

from appellatives that provided factualdescriptions of the locality. Place-names fromthe Viking period are not any longer onlydescriptive. Many farm-names from this periodcelebrate the individual who founded the farm,reflecting the big social upheaval that thebreak-up of a society funded on ancestry andkinship implied. From now on farms belong toindividuals. Finally, during the Scandinavianexodus to North America we see how farm namesmore than ever attach the owner to the farm, butthere is by now a new element added in that manyof the Scandinavian-American names express astrong sense of a common geographical origin andhistorical heritage, products of a schoolprogramme with a mission to foster ideas like thenecessity to belong to a nation and an ethicallydefined group.

LiteratureAdigard des Gautries, Jean (1954) Les noms de

personnes scandinaves en Normandie de 911 à 1066, Lund.Beito, Olav T. (1986) Nynorsk grammatikk. Lyd- og

formlære, 2nd ed., Oslo. Brink, Stefan (1996) ’The onomasticon and the

role of analogy’, in Namn och bygd 84, Uppsala(:61-84).

Brøgger, A.W. (1929) Ancient Emigrants, Oxford.Cameron, Kenneth (1971) ‘Scandinavian settlement

in the territory of the Five Boroughs: theplace-name evidence,’ in: P. Clemoes & K.Hughes, eds., England Before the Conquest, Cambridge(:147-63).

Diderichsen, Paul (1962) Elementær dansk grammatik,3rd ed., Copenhagen.

56 Kruse

Jakobsen, Jakob (1936) The Place-Names of Shetland,London & Copenhagen.

Jungner, Hugo (1920) ’Fornvästgötar på vandring.Är Als härad en skapelse från den förstaFrigg-entusiasmens dagar?’, in: Västergötlandsfornminnesföreinings tidskrif,t 4.

Finnur Jónsson (1914) ’Islandske elvenavne’, in:Namn och bygd (:18-28).

Gustavsson, Anders (2005) ’Modern Norwegians inBohuslän: Cultural Encounters in the BorderArea’, in: Arv 61, Uppsala (:163-204).

Hallaråker, Peter (1995) Stadnamn i Møre og Romsdal.Innsamling, teori, metode og formidling,Forskingsrapport nr. 8, Møreforsking, Volda.

Haugen, Einar (1953) The Norwegian Language in America.A Study in Bilingual Behaviour, vols. 1-2,Philadephia.

Holm, Tomas Campanius (1702) Kort Beskrifning omProvincien nya Swerige (A Short Description of the Province ofNew Sweden), Stockholm.

Kruse, Arne (1991) ‘Norske stadnamn i CoonValley, Wisconsin. Møte mellom totradisjonar’, in: B. Helleland, ed., Norsk språki Amerika / Norwegian Language in America, Oslo (:135-71).

Kruse, Arne (1996) ‘Scandinavian-American place-names as viewed from the Old World’, 255-67,in: P. Sture Ureland & I. Clarkson, Languagecontact across the North Atlantic, Tübingen.

Kruse, Arne (1998) ‘Sjønamn på médfjella’, in:Namn og Nemne, Bergen (:21-31).

Kruse, Arne (2000) Mål og méd. Målføre og médnamn fråSmøla, Tapir: Trondheim.

Kruse, Arne (2004) ‘Norse Topographical Names onthe West Coast of Scotland’, in: J. Adams and

Scandinavian names abroad 57

K. Holman, eds., Scandinavia and Europe 800-1350:Contact, Conflict and Co-existence, Brepols (:97-107).

Kuhn, Hans (1966) ’Die Ortsnamen der Kolonien unddas Mutterland’, in: D.P. Blok, ed., Proceedingsof the Eight International Congress of Onomastic Sciences,The Hague, Paris (:260-265).

Kuhn, Hans (1949) ’Birka auf Island’, in: Namnoch bygd 37 (:47-64).

Landelius, Otto Robert (1985) Swedish Place-Names inNorth America, Southern Illinois UniversityPress: Carbondale.

Macniven, Alan (2006) The Norse in Islay, unpublishedPhD-dissertation, University of Edinburgh,Edinburgh.

Mæhlum, Brit (1992) ‘Dialect Socialization inLongyearbyen at Svalbard (Spitsbergen): afruitful chaos’, in: Ernst Håkon Jahr, ed.,Language Contact. Theoretical and Empirical Studies(=Trends in Linguistics. Studies andMonographs 60), Berlin & New York (:117-30).

Nes, Oddvar (1989) ‘Stadnamn på strekkja Volda -Runde’, in: P. Hallaråker, A. Kruse and T.Aarset, eds., Stadnamn i kystkulturen, NORNA-rapporter 41, Uppsala. (:63-76)

Nicolaisen, W.F.H. (1980a) ’Early ScandinavianNaming in the Western and Northern Isles’, in:Northern Scotland 3, 2 1979-80 (:105-21).

Nicolaisen, W.F.H. (1980b) ‘Onomastic dialects’,in: American Speech 55, No. 1 (:36-45).

Nicolaisen, W.F.H. (1991) ‘Scottish analogues ofScandinavian place names’, in: G. Albøge etal., eds., Analogi i namngivning, NORNA-rapporter45, Uppsala.

Nicolaisen, W.F.H. (1995) ’Name and Appellative’in: Ernst Eichler et al., eds. Namenforschung,

58 Kruse

Name Studies, Les noms propres, vol. 1, Berlin & NewYork (:384-93).

NSL: Norsk stadnamleksikon (1997) ed. by J. Sandnesand O. Stemshaug, Oslo.

Nyström, Staffan (1988) Ord för höjder och sluttningar iDaga härad. En studie över betydelsen hos två grupperterrängbetecknande appellativ och ortnamnselement,Uppsala & Stockholm.

Pamp, Bengt (1976) Ortnamnen i Sverige, Lund.Pálsson, Hermann (1996) ‘Aspects of Norse Place

Names in the Western Isles’, in: Northern Studies31, Edinburgh (:7-24).

Rennick, Robert M. (1984) Kentucky Place Names,Lexington: University Press of Kentucky.

Rudnyćkyj, J.B. (1952) ‘Classification ofCanadian Place-names’, in : Quatrième CongrèsInternational de Sciences Onomastiques, Vol. I,Uppsala (:452-57).

Rygh, Oluf (1898) Norske Gaardnavne. Indledning,Kristiania.

Sandnes, Jørn (1997) ’Navneleddet tun i norskegårdsnavn’, in: Ortnamn i språk och samhälle.Hyllningsskrift till Lars Hellberg, ed. by SvanteStrandberg, Uppsala (:225-31).

Smith, Brian (1992) ‘Kebister – a short history’in: Shetland Life, no. 135, January (:38-43).

Stewart, George R. (1954) ‘A Classification ofPlace Names’, in: Names 2 (:1-13).

Stewart, George R. (1975) Names on the Globe, NewYork.

Stoltenberg, Åse Kari (1994) Nordiske navn iNormandie, unpublished Cand. Philol.dissertation, University of Bergen: Bergen.

Sigmundsson, Svavar (1985) ‘”Synonymi” itopografiske appellativer’, in: Þ.Vilmundarson, ed., Merking staðfræðilegra samnafna í

Scandinavian names abroad 59

örnefnum, NORNA-rapporter 28, Uppsala (127-35).Sigmundsson, Svavar (1991) ‘Analogi i islandske

stednavne’, in: Analogi i navngivning. Tiende nordiskenavneforskerkongres. Brandbjerg 20.-24. maj 1989, G.Albøge, E.V. Meldgaard & L. Weise, eds.,NORNA-rapporter 45, Uppsala (:189-197).

Sigmunsson, Svavar (2006) ’Farm-names in Icelandcontaining the element tún’, in: P. Gammeltoftand B. Jørgensen, eds., Names through the Looking-Glass. Festschrift in Honour of Gillian Fellows-Jensen July 5th

2006, Reitzel : Copenhagen (:275-87).Utterström, Gudrun (2001) ‘Nova Sueica, die

schwedishe Kolonie Delaware – Namen undSprachen’, in: P.S. Ureland, ed., GlobalEurolinguistics. European Languages in North America –Migration, Maintenance and Death, Tübingen (:63-78).

Vimundarson, Þórhallur (1996) ‘Overførelse afstednavne til Island’, in: K. Kruken, ed., Denellevte nordiske navneforskerkongressen, Sunvollen 19.-23.juni 1994, Uppsala (:398-411).

Zilliacus, Kurt (1975) Onomastik, unpublishedmanuscript. [Published in Kurt Zilliacus, Forskai namn, Skrifter utgivna av Svenskalitteratursällskapet i Finland 640,Helsingfors 2002.]

Zilliacus, Kurt (1997) ‘On the function of propernames’, in: R.L. Pitkänen & K. Mallat, eds.,You name it. Perspectives on onomastic research, Helsinki(:14-20).