Community forestry in the DRC: lessons learned from the Congo basin

-

Upload

tu-dresden -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of Community forestry in the DRC: lessons learned from the Congo basin

Deutsche Gesellschaft für

Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ)

GmbH

Programme Biodiversité et Forêts

COMMUNITY FORESTRY IN THE DRC:

LESSONS LEARNED FROM THE CONGO BASIN

April 2015

PN 12.2517.6-001.01

Appie van de Rijt

Short term National expert

1

Recommended citation: Van de Rijt, A. (2015). Community forestry in the DRC: Lessons learned from

the Congo basin. Programme de Biodiversité et Forêts (PBF) / Deutsche Gesellschaft für

Inernationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ). Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo.

The information and views set out in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily

reflect the official opinion of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Inernationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ).

Neither the GIZ nor any person acting on their behalf may be held responsible for the use which

may be made of the information contained therein.

Copyright © GIZ 2015

Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged.

2

RÉSUMÉ En Août 2014, le décret de la RDC sur la foresterie communautaire a été signé, la promulgation des

modalités pour les communautés locales pour obtenir une concession forestière. Cette étape

importante vers la finalisation du cadre juridique de la forêt concernant la foresterie communautaire

rapproche les communautés un peu plus de l'utilisation des forêts pour le développement local. Les

communautés forestières détiennent souvent les droits coutumiers sur les terres et la foresterie

communautaire offre des possibilités juridiques supplémentaires utilisant ces forêts pour leur

développement local. La foresterie communautaire est un concept qui a été mis en œuvre à l'échelle

mondiale, souvent avec succès.

En particulier au Cameroun, le concept a été mis en place plus récemment avec des résultats mitigés.

D'autres pays de la région, le Gabon et la RDC, ont vu la mise en œuvre de ce modèle de gouvernance

forestière à l'échelle pilote. Cette étude donne un aperçu de l'expérience obtenus avec la foresterie

communautaire en Afrique centrale, et résume les leçons tirées de leur part. En RDC, les projets de

gestion des ressources naturelles à base communautaire offrent des leçons supplémentaires utiles

pour la mise en œuvre de la foresterie communautaire.

L'étude est basée sur une étude de la littérature, mais a été complétée par des interviews d'experts

avec des représentants des ONG´s et la coopération bilatérale au développement. Sur la base des

données recueillies l'étude a indiqué 15 points-clés qui nécessitent une attention pour donner à la

foresterie communautaire plus de succès. Les aspects qui nécessitent une attention supplémentaire

sont souvent le reflet de questions sociétales visibles à tous les niveaux de gouvernance (par exemple :

capture de rente par l´élite, le besoin de responsabilité), et le risque de généralisation des

communautés constitue une menace pour la mise en œuvre réussie. Les principales conclusions de

l'étude sont:

1. La foresterie communautaire a le potentiel

2. Le cadre juridique doit être complété

3. Le régime foncier doit être garanti

4. La RDC est trop diverse pour une approche unique

5. Les institutions coutumières doivent être reconnues

6. Les droits des groupes vulnérables doivent être garantis

7. La planification des ressources naturelles doit être participative

8. Les solutions pour l’exploitant à petite échelle sont nécessaires

9. La REDD + peut être combiné avec la foresterie communautaire

10. La gouvernance doit être améliorée

11. Le capture de rente par l´élite devrait être évitée

12. La responsabilisation est nécessaire pour prévenir les conflits 13. La Prise en charge de la foresterie communautaire devrait atteindre le seuil 14. Les usages de la forêt autres que le bois doivent être pris en compte 15. L'information doit être partagée.

D'importantes leçons sont disponibles pour rendre à la foresterie communautaire plus de succès, mais le partage et l'évaluation des expériences existantes sont nécessaires pour éviter les erreurs commises ailleurs, et d'éviter les pièges posés par le contexte de la gouvernance nationale.

3

ABSTRACT In August 2014 the community forestry decree for the DRC was signed, promulgating the modalities

for local communities to obtain a forest concession. This important step towards the finalization of

the forest legal framework concerning community forestry brings communities one step closer to

the use of the forests for local development. Forest communities often hold customary rights over

land and community forestry provides additional legal opportunities use these forests for their local

development. Community forestry is a concept that has been implemented globally, often with

success.

In particularly Cameroon, the concept has been implemented more recently with mixed results.

Other countries in the region, Gabon and the DRC, have seen implementation of this forest

governance model on a pilot scale. This study provides an overview of the experiences obtained with

community forestry in Central Africa, and summarizes the lessons learned from them. In the DRC,

community based natural resource management projects provide additional lessons useful for the

implementation of community forestry.

The study is based on a literature study, but was complemented with expert interviews with

representatives of NGO´s and bilateral development cooperation. Based on the collected data the

study has indicated 15 key-points which require attention to make community forestry more

successful. Aspects that require additional attention are often reflections of societal issues visible on

all levels of governance (e.g. elite rent capturing, need for accountability), and the risk of

generalization of communities forms a threat to successful implementation. The key findings of the

study are:

1. Community forestry has potential

2. The legal framework needs to be completed

3. Land tenure needs to be secured

4. The DRC is too diverse for a “one size fits all” approach

5. Customary institutions need to be recognized

6. Rights of vulnerable groups need to be guaranteed

7. Natural resource planning needs to be participatory

8. Solutions for individual small scale logging are needed

9. REDD+ can be combined with community forestry

10. Governance needs to be improved

11. Elite rent capturing should be prevented

12. Accountability is needed to prevent conflicts

13. Support for community forestry should meet the threshold

14. Forest uses other than timber should be taken into account

15. Information should be shared

Important lessons are available to make community forestry more successful, but sharing and

evaluation of existing experiences are required to avoid the mistakes made elsewhere, and to avoid

the pitfalls posed by the national governance context.

4

RÉSUMÉ ....................................................................................................................................... 2

Abstract ....................................................................................................................................... 3

List of Acronyms .......................................................................................................................... 5

Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 7

Background ................................................................................................................................... 7

Brief introduction into community forestry .................................................................................. 8

Methodology ............................................................................................................................... 8

Study area ..................................................................................................................................... 8

Methods ........................................................................................................................................ 8

Results ......................................................................................................................................... 9

Establishment of community forests in the congo basin .............................................................. 9

Community Forestry in Cameroon .............................................................................................. 10

Characteristics of Community forestry ............................................................................ 10

contribution to local development................................................................................... 10

Production and marketing ................................................................................................ 11

Conflicts ............................................................................................................................ 11

Self-management and subcontracting ............................................................................. 12

Clustering .......................................................................................................................... 12

Ecological sustainability. ................................................................................................... 13

Community forestry in Gabon ..................................................................................................... 13

Community forestry in Central African Republic ......................................................................... 13

Community forestry in the DRC .................................................................................................. 14

Community forestry Projects ........................................................................................... 14

Community Based natural resource management projects ....................................................... 16

Discussion and Conclusions ........................................................................................................ 19

lessons learned from Community forests and community based natural resource management

in The Congo basin ........................................................................................................... 19

5

Acknowledgements.................................................................................................................... 23

Annexes..................................................................................................................................... 29

LIST OF ACRONYMS

AWF African Wildlife Foundation

CAGDFT Centre d’Appui à la Gestion Durable des Forêts Tropicales

CAR Central African Republic

CARPE Central African Regional Program for the Environment

CBNRM Community Based Natural Resource Management

CF Community forests

CFM Community forest management

CEDEN Centre pour la Défense de l'Environnement

COMIFAC Commission des Forêts d’Afrique Centrale

DACEFI Development of Community Alternatives to Illegal Logging

DFS Deutsche Forst Service GmbH

DRC Democratic Republic of Congo

FAO (United Nations) Food and Agriculture Organization

FLEGT Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade

GIZ Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (German

development Cooperation)

IUCN International Union for Conservation of Nature

NGO Non-Governmental organization

NTFP Non-Timber Forest Product

NRM Natural resource management

OCEAN Organisation Concertée des Ecologistes et Amis de la Nature

PBF Programme de Biodiversité et Forêts

REDD+ Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation

SMP Simplified management plan

SNV Stichting Nederlandse Vrijwilligers (Dutch Development Cooperation)

6

USAID United States Agency for International Development

WCS Wildlife Conservation Society

WWF World Wildlife Foundation

7

INTRODUCTION

BACKGROUND In August 2014, the government of the Democratic Republic of Congo signed the community forestry

decree that promulgates the modalities for communities to obtain a community concession.

Community concessions will allow communities to manage the forest resources over which they have

customary rights and to use the forest resources in a way that contributes to the local development.

Communities can decide to manage the resources themselves or to outsource the management to

third parties, such as artisanal operators, conservation organizations or ecotourism projects

(Rainforest Foundation UK 2014). The actual implementation of the first community forest will not be

formally recognized in the near future since the elaboration of the technical directives were at the

time of writing (2015) still ongoing.

The Congo basin forests are after the Amazon basin forests the largest tropical forest in the world.

They provide many ecosystem products and services to local, national and international economies.

The majority of the Congo basin forests are located in the Democratic Republic of Congo´s (DRC) (54%)

(Mayaux et al. 2004), where 70% of the population depends on them for their livelihoods. This figure

underlines the importance of the sustainable forest management in a way that local people benefit

from them (African Community Rights Network 2014). There are three forms of legal forest rights in

the DRC. The two dominant forms of legal forest tenure in the Congo basin are industrial logging

concessions (595,381 km2) and protected areas (444,973 km2)(Nasi et al. 2012). Both land uses are

very large scale and highly restricting the user rights for local communities. The third form of legal

forest right are community forests. Which cover approximately 10,000 km2 (Nasi et al. 2012) and are

the only legal from of communal forest tenure. Concession based forestry has failed to deliver the

expected benefits to conservation and local community development despite large international

support. Consequentially more decentralized and participative forest models have become prioritized

in forest policy (Eisen et al. 2014). The realisation on paper often seems more successful than the

reality, especially since there are systemic shortages of means and man power on the lower

administrative levels (Eisen 2015 Pers. Comm.). During the last decades, community based forest

management has been a priority in national and international forest policy debates (Gauld 2000;

Pretzsch 2005), and communal forest management has been implemented throughout the tropics

(Sabogal et al. 2008; Cuny 2011; Sunderlin 2006). In the Congo Basin only limited experience is

available. In other parts of the world it has been implemented for decades with positive results in e.g.

Mexico (Bray et al. 2006) and Nepal (Pandit & Bevilacqua 2011).

This study summarizes the experiences in community forest management (CFM) in the Congo Basin,

with a specific focus on the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Nearly all countries mention CFM in

their forest law, but the completion of the legal framework delays the actual implementation. For

instance, thanks to its early adoption the community forestry model Cameroon has obtained a

regional leading role, and provides extensive lessons (positive and negative) on community forests.

This allows a more detailed study in themes such as conflicts and innovative approaches. In Gabon,

community forestry has been introduced more recently thus limited information available and mostly

based on specific cases from pilot projects. To capitalize on relevant experiences available in the

national context, the scope of the study in the DRC includes both pilot community forestry projects

and relevant Community Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM) projects.

This study has been performed for the Programme for Biodiversity and Forest (PBF) of the Deutsche

Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ). The study forms a contribution to the

community forestry project of PBF/GIZ in Kailo, the province of Maniema, the East of the DRC. This

project aims to test a new form of forest co-management model, a community concession. It combines

8

local communities and loggers in the management of the forest resources, and to provide a legal

sustainable forest management strategy to fill the gap between small scale (artisanal) and large scale

(industrial) logging.

BRIEF INTRODUCTION INTO COMMUNITY FORESTRY In its broadest sense, community forestry can be considered as ´forestry for the people and by the

people´ (Karsenty et al. 2010). Community forest management allows communities to benefit from

their forests and its resources, in contrary to external entrepreneurs and the political elite which

usually benefit from other forms of forest management (de Jong et al. 2006). In theory, a community

forest is considered to have three objectives: increase the welfare of rural populations, conserve forest

resources and biodiversity, and improve local governance through devolution of forest management

responsibilities to local democratic organizations (Oyono et al. 2006).

Community forestry combines two realities; (1) a customary reality where local people manage and

use the forest and (2) the public authorities who create a legal category “Community Forests”, and

allocate land to it (Karsenty et al. 2010). In all Congo basin countries the forest resources are vested

in the nation with the state as custody, only allowing the issuance of temporary management

contracts (Eisen et al. 2014). The institutional systems are based on the French system, which does

not permit the transfer of management responsibilities directly to a customary institution without

formal legal recognition. Therefore the system requires the recognition or creation of a legal entity

prior to the allocation of land and its management responsibilities to communities (Karsenty et al.

2010). In Cameroon and Gabon the legal entity is established by organizing the community into

collective interest groups or cooperatives with elected leaders (Karsenty et al. 2010). Traditional forest

tenure is family based, with groups that tend to be smaller than the communities defined within the

CFM process (Martijn Ter Heegde 2015 pers. Comm).

METHODOLOGY

STUDY AREA The study focusses on the Congo basin countries Cameroon, Central African Republic (CAR), Gabon

and especially the DRC. The study intended to include Equatorial Guinea, Republic of Congo, Angola

and Chad, but were excluded for several reasons; it was difficult to obtain credible information for

Equatorial Guinea, the Republic of Congo has no legislation for community forests, Angola only

community based natural resource management found with limited information available, and Chad

differs ecologically and culturally strongly from the DRC.

METHODS The information was obtained from scholarly literature, books and reports from bilateral organizations

and from non-governmental organizations (NGO´s) and from expert interviews. The most important

sources have been the bilateral donor organizations; SNV and the United States Agency for

International Development (USAID), the GIZ and international “green” NGO´s Rainforest foundation

UK, Forest Monitor, WCS and WWF. Many of the used literature originates directly from these

organizations, or is based on their experiences. The information was gathered, categorized and

analysed with Mendeley 1.13.2 and CITAVI 4.4.

The study includes more detailed information from the combined experiences with community in

Cameroon. The section on the DRC contains more case specific information, including general

information on the projects, and case specific lessons learned from community forestry pilot projects,

REDD+ pilot projects and CBNRM projects.

9

In addition to the literature study, the author participated in two workshops on the topic of

community forestry visited during the initial stage of the study. Five semi-structure interviews were

held with experts from WWF, CEDEN, OCEAN and CAGDFT, SNV and DFS for additional information.

FIGURE 1 THE STUDY AREA, THE CONGO BASIN COUNTRIES. ADAPTED FROM: BELE ET AL. (2014)

RESULTS

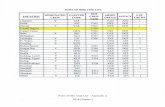

ESTABLISHMENT OF COMMUNITY FORESTS IN THE CONGO BASIN Community forests are provided for in the forest legal framework in nearly all Congo basin countries,

but have been formally recognized in Cameroon and in Gabon only. The far majority, 262 out of 266

is found in Cameroon (Vermeulen 2014; Eba'a Atyi et al. 2013). Incomplete legislative frameworks in

the region have been impeding the progress of community forestry and have caused a major

implementation gap (Figure 2). Even when essential forest policy documents are passed the actual

implementation can be delayed with years due to the lack of information sharing between the central

government and field officials (Eisen et al. 2014).

The community forests in Gabon follow the

model of Cameroon, restricting the size to

maximum 5,000 ha, in contrary to the DRC which

has set the maximum size to 50,000 ha.

Another major obstacle in the process of

establishing community forests is the allocation

of land. Land is limitedly available due to competing land-uses such as industrial logging and mining

concessions, and more recently agro-industrial concessions (Meunier et a. 2011). The implications of

a limited size means that the community forest does not represent the customary land claim which

INCOMPLETE LEGISLATIVE FRAMEWORKS IN THE

REGION HAVE BEEN IMPEDING THE

IMPLEMENTATION OF COMMUNITY FORESTRY

AND HAVE CAUSED A MAJOR IMPLEMENTATION

GAP.

10

may contribute to conflict. It also means that the costs of establishment need to be compensated by

the products from a smaller area. This may contribute to overharvesting.

FIGURE 2 THE LEGAL PROCESSES OF COMMUNITY FORESTRY IN THE CONGO BASIN STATES. SOURCES USED: 1DEWASSEIGE ET AL. (2014), 2EISEN ET AL. 2014, 3RAINFOREST FOUNDATION UK (2011).

COMMUNITY FORESTRY IN CAMEROON

CHARACTERISTICS OF COMMUNITY FORESTRY In Cameroon, community forests are located in the non-permanent forest domain, restricted in size

to 5000 ha per community, have an average size of around 3000 ha and are issued for a 25 year period.

With these characteristics the community forests are similar to a forest concession, just with a

different size and regulatory framework (Ezzine de Blas et al. 2009). In 2013, the 262 community

forests cover around 9,000 km2 (Vermeulen 2014), and jointly representing 2-4% of the domestic

timber market (Cuny 2011).

Community forestry in Cameroon is mainly oriented on income generating activities, primarily timber

production. It needs to be pointed out that traditionally the forest based economy consisted mainly

of hunting and non-timber forest product (NTFP) production, and timber production in most

communities a relatively concept. The areas available for community forests tend to be limited in size,

due to the prevalence of logging concessions and protected areas. And timber resources often tend

to be limited due to previous logging activities (Martijn Ter Heegde 2015 pers. Comm.). The production

of timber was initial intended to take place under communal management, however 80% of the

community forests were being exploited under subcontracts in 2011 (Cuny 2011).

CONTRIBUTION TO LOCAL DEVELOPMENT Fifteen years of community forests have produced mixed social, environmental and economic

outcomes (Cuny 2011; Julve et al., 2007; Vermeulen et al., 2006). Throughout Cameroon community

forests contribute only marginally to the economic and infrastructural development of the village and

its inhabitants (Lescuyer 2007; Ezzine de Blas et al. 2009; Beauchamp and Ingram 2011; Lescuyer

2013). An important cause for the limited economic success of the community forests is the

unfamiliarity of communities with the processes of timber production and marketing. These are

traditionally not a part of the forest economy and thus function not optimally (Martijn Ter Heegde

2015 pers. Comm).

11

The studies show that collective revenues are relatively low and little used for collective investments.

The management entity is the second largest expense item, and only 20% of the collected revenues is

effectively invested in community development, mostly water, health and education (Eba’a Atyi et al.

2013). Many factors reduce the economic impact of CF´s; the small authorized annual logging area,

the unfamiliarity of local organizations with international timber markets, the obligation to use

community forest income in collective investments (Lescuyer 2013), and conflicts (Michael Vabi 2015

pers. Comm.). In several occasions additional income was being obtained by the illegal trade of legal

documents such as way-bills to facilitate illegal logging (Bauer 2011; Eba’a Atyi et al. 2013).

PRODUCTION AND MARKETING According to Julve et al. (2007) communities can obtain significantly more benefits on the

international market, but several factors are negatively affecting the competitiveness of timber

production in community forests. On the international market the competitiveness is reduced by the

maximum size of 5,000 ha which significantly increases the unit costs of legal verification and

certification, which are required for accessing the international market (Eba'a Atyi et al. 2013). And

the prohibition of the use of industrial equipment, since the allowed alternative methods result in

lower quality sawn wood which is less desired on the international market (Eba'a Atyi et al. 2013). The

domestic market is dominated by informal timber operators who have far lower production costs since

they operate outside the legal framework and restriction (Julve et al. 2013).

CONFLICTS Conflicts have significantly reduced the contribution of community forestry to improved rural

livelihoods (Ezzine de Blas et al. 2011; Michael Vabi 2015, pers. Comm.). Ezzine de Blas, et al. (2011)

analysed 20 community forests and found three causes for systemic conflicts: illegal logging,

mismanagement and corruption of governmental officials.

Informal small‐scale logging is in general considered one of the largest threats to community forestry,

and has been increasing heavily the last decade. To reduce the competitive advantage of informal

logging over community forest management (CFM), strong simplification of procedures and improved

regulation of the informal sector are needed (Karsenty et al. 2010). Internal conflicts have indicated

the lack of accountability and the need for mechanisms for improved governance of logging revenues.

It also stresses the role of social capital within the community, its importance as a prerequisite for

international assistance and necessity to create it in the capacity building process.

External conflicts occur mainly with logging operators and governmental officials. The nature of the

systemic external conflicts is related to the nature of the internal conflicts: appropriation of benefits,

mismanagement, and struggles over control of the community forest timber resources (Ezzine de Blas,

et al. 2011).

The frequency of internal conflicts was found to be related to the proportion of the benefits shared

collectively. Communities with a higher level of investment in community development have fewer

conflicts (Julve et al. 2007; Ezzine de Blas, et al. 2011). Fair benefit sharing of logging revenues

contributed more to a consensus than the height

of the financial benefits derived from logging

(Julve et al. 2007). Julve and Vermeulen (2008)

and Beauchamps and Ingram (2011) concluded

that an investment plan in community

development projects prior to the implementation of the CF is an important way to prevent conflict

and wasteful use of common monetary resources. At the same time is the lack of monitoring often

results in ineffective implementation of such financial governance. The institutionalization of

COMMUNITIES WITH A HIGHER LEVEL OF

INVESTMENT INTO COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT

HAVE LESS CONFLICTS

12

investment plans improves long term planning with income and investments, and helps to prevent

internal conflicts (Mbia et al. 2010).

SELF-MANAGEMENT AND SUBCONTRACTING The expansion of community forestry in Cameroon largely took place thanks to the international

support in the end of the 1990´s. Many pilot projects were initially financed, but after difficulties arose

with the implementation many donors ended funding. This was followed by the formation of new

partnerships between community forests and

commercial logging companies (Cuny 2011).

Many communities outsourced management to

the logging companies despite the greater

revenues of self-management (Ezzine de Blas et al. 2009). Lack of commercial logging skills contribute

to the reduced ability of community to achieve a higher level of vertical integration independently.

The chances for independent self‐management were found to depend on the distance to the market.

More distant communities are more likely to delegate management power or sell timber rights to

artisanal or industrial loggers (Ezzine de Blas et al. 2009). This is explained by the dependency of timber

production on road conditions and market knowledge, which can be hard to obtain on community

level (Karsenty et al. 2010). The distance to the market could be overcome with infrastructural

improvement, however that would have a negative environmental impact on the remaining forests

(Ezzine de Blas et al. 2009). And would increase the risk for illegal logging from external groups.

In Cameroon, community forestry was conceived, planned and implemented in a top down manner

high-level decisions for community forestry were made without any consultation at national level or

participation of lower level. The process of obtaining a CF is rather complex and despite the name of

“simple” management plan is its elaboration a very complex process and beyond reach for

communities without external support. The complex procedures resulted in high investment costs for

communities and operators, creating incentive for quick returns, increased pressure on forest

resources and non-compliance with regulations (Eisen et al. 2014). Increased participation of

stakeholders in these processes can reduce the risk of such problems in later stages.

CLUSTERING To address several of the problems mentioned above the clustering of communities was developed.

This approach aims to improve the socio-economics of the participating villagers via capacity building

in natural resource management and thus improving the economic revenues obtained from the forest.

In total three clusters of CF´s were established containing between two and five CF´s. The cluster

approach is similar to the formation of cooperatives combined with certain aspects of Farmer Field

Schools. Training was provided to the elected representatives of the CF´s. They would pass on the

knowledge to the managing committee of their

CF´s. The cluster meetings also provided a forum

for the exchange of experiences, problems and

solutions. At the same time, products were sold on

the international market as a group to use

combined skills and thus improve the market position (Michael Vabi 2015, pers. Comm.).

According to Mbia et al. (2010) is clustering of CF´s is an effective mean to increase resource and time

efficiency, and a forum for communities to discuss and address common problems jointly. The

clustering of CF´s also improved forest governance because membership of a cluster requires taking

position actively against illegal exploitation, raising awareness and discussing unacceptable internal

and external governance practices. The project also improved the behaviour of field officials of forest

DISTANT COMMUNITIES REQUIRE MORE

EXTERNAL SUPPORT TO OVERCOME BARRIERS,

THAN COMMUNITIES CLOSER TO URBAN AREAS

COMMUNITY FOREST CLUSTERS INCREASE

RESOURCE EFFICIENCY AND PROBLEM SOLVING

CAPACITY OF INVOLVED COMMUNITIES

13

authorities, who became less repressive and more willing to facilitate to access to administrative

documents for exploitation.

ECOLOGICAL SUSTAINABILITY. The technical aspects of the elaboration of a Simple management plan are designed to ensure

ecological sustainability and maintain forest stability. However, in reality are the mandatory forest

inventories performed in a bad way and little used for actual management decisions (Eba’a Atyi et al.

2013), or are intentionally falsified (Bauer 2012). It should be taken in consideration during the

implementation of projects that rural communities in forested areas often tend to have other

priorities than “sustainable use” of the resource (Vermeulen 2000).

COMMUNITY FORESTRY IN GABON The Gabonese forest law of 2001 opened up the possibility for community forests, but no community

forests were formally established until 2013. In 2013, four community forests were established with

the help of international NGO´s and were formally recognized by the government (Eisen et al. 2014;

Meunier et a. 2014). This gap between the 2001 forest law, and the establishment of the first

community forest in 2013 might have been caused by the “coupes familiales”, the right for community

members to cut and sell a certain amount of trees per year (Karsenty et al. 2010).

The community forests have been part of the European Union financed project DACEFI (Development

of Community Alternatives to Illegal Logging) implemented by the Belgian NGO Nature+, WWF and

the Belgian university Gembloux Agro-Bio Tech. The project had successes with: (1) the

implementation of the first community forests in the country and to spread the concept of community

forestry. (2) The contribution to the administrative

and technical processes necessary for community

forests to successfully implemented, like the

simplification of admission processes. (3)

Empowerment and capacity building within local

communities. (4) The value addition to forest

products to increase the income of the communities (Quentin Meunier 2015 pers. Comm.). Significant

challenges also have been described. Firstly, the allocation of land for community forests in Gabon is

problematic since customary land claims are overlapping with protected areas, industrial forest and

mining concessions (Annex I). In contrary to concessions, customary land claims are usually not

formally recognized and thus are susceptible to reclassification. Concessions an important source of

foreign currency for the government (Morin et al. 2014), however the trickledown effect to lower

administrative levels remains questionable. Secondly, there has been a lack of assistance for

communities from the state and a long term incomplete legal framework, while external actors

creamed off the valuable timber species from (Meunier et al. 2011). And lastly, participation of the

youth in village committees has been limited, despite that community forestry provides opportunities

for them (Boldrini et al. 2013).

COMMUNITY FORESTRY IN CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC No formal community forests have been established in the Central African Republic (CAR), and forest

management is dominated by international logging companies. Several hunting reserves have been

created which involve various levels of participation of local communities. Recently the NGO

Rainforest Foundation UK has cooperated with the government to map community forests in a

participatory way with local communities. The communities expressed the desire to obtain access to

community forests (Rainforest Foundation UK 2011).

COMMUNITY FORESTS CAN POTENTIALLY

TRANSFORM VILLAGES INTO LOCAL

EMPLOYMENT CENTRES AND INTEGRATE THE

LOCAL YOUTH IN ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

14

The 2008 forest law mentions community forests as a management form, nevertheless CF´s have not

seen implementation yet. The forest authorities are in charge lacking the capacity to oversee/manage

the law at present (Blaser et al. 2012). The 2008 forest law contains several progressive elements

including provisions for community forestry and certain safeguards concerning the rights of

communities around areas protected for biodiversity. Also, the FLEGT Voluntary partnership

agreement with the EU signed in December 2010 contained requirements to respect rights of local

and indigenous people, and the improvement of the framework for community forests (Rainforest

Foundation UK 2011).

COMMUNITY FORESTRY IN THE DRC The 2002 forest law article 22 states that a community may, upon request, obtain a part or totality of

an area that falls under the designation of customary forests under the title of forest concession. The

procedures for granting such concessions are governed by decree from the President of the Republic,

and are free of charge (Greenpeace 2014). The modalities of obtaining a community concession were

not further elaborated, and thus no formally recognized community forest concessions have been

established in the DRC so far. The size of the DRC, her forests and the global importance of them have

caused large scale international involvement in the process towards community forestry. This

influence is reflected in the pilot processes and the legal framework developments.

Progress was made in August 2014, when the community forestry decree fixing the modalities for

acquiring a forest concessions was issued. The decree enables the implementation and formal

recognition of community forests and describes the concessions as a communities´ right with a size

up to 50,000 ha. It also recognizes additional customary claims beyond this size (Greenpeace 2014). It

is worth stating that the concession duration is determined as perpetual, a significant departure from

the 15-30 year leasehold arrangements offered in other counties (Eisen et al. 2014). The DRC has not

build its community forestry model on the Cameroonian model. This has been critically acclaimed by

the civil society (FERN 2014).

COMMUNITY FORESTRY PROJECTS The available experiences with community forestry are based three pilot projects with different

approaches. The first, FORCOM was financed by Belgium and implemented by the FAO. Project

FORCOL was implemented by the civil society namely the British NGO Forest Monitor (Maindo & Kapa

2014). The third project is the PBF/GIZ pilot project in Maniema, which was still ongoing at the time

of writing. All projects have pioneered with CFM in the DRC, and have produced draft versions for

community forestry decrees, to complement the legal framework. The Forest Monitor project initially

intended to implement a pilot community forest but decided not to due to the lack of legal framework

progress. The two projects FORCOM and FORCOL have been complementary (De Wit 2010; Maindo &

Kapa 2014).

Project FORCOM was implemented by the FAO from 2007 to 2012. The implementation took place on

four locations with different ecological and socio-economic characteristics. Luki, located in a biosphere

reserve in Bas-Congo between two economic centres, the harbour city of Matadi and the capital of

Kinshasa. Lisala-Bumba, situated in the proximity of forest concessions in the dense forests of the

inland province of Equateur. Miombo in the savannah like vegetation of Katanga. And the fourth one

in the relatively intact forests of UMA in the Orientale province. To obtain the best results a

participative and integrated approach was chosen for the implementation of community forestry in

the DRC (Maindo & Kapa 2014).

The pilot sites in Miombo and Lisala-Bumba were chosen according to the following criteria: well-

studied, described and delimitated in terms of customary tenure and meeting the predetermined

15

biophysical conditions. Luki was added later for other

reasons. And UMA was a deliberate choice based on

local needs, the prospect of valorisation and integrated

protection of forest natural resources, and with the

participation of the University of Kisangani (Dominique

Bauwens 2015 pers. comm.). The location UMA

continues to progress and provides promising prospects

concerning timber production and potentially

ecotourism (Boyemba 2015).

For the multi-resource inventories a rapid appraisal was

used. The gender based socio-economic analyses was

performed in all strata of the community included

participatory mapping to guarantee the representation

of all stakeholders. The integrated approach included

market development, education and the stimulation of

economic start-ups and local institutional reinforcement

(Maindo & Kapa 2014).

The project has underlined the necessity for improved education on all levels of governance, the need

for the distribution of the strategic forest policy objectives, and the implementation of pilots where

sustainable forest management models function without conflict with other authorised land uses

(Maindo & Kapa 2014).

An important pillar has been institutional assistance. One of the results has been a draft version of the

legal framework on community forests. An important lesson learned according to Maindo & Kapa

(2014) is the importance of the selection of promising location with a willing population. The same

authors draw similar concluding remarks as others have done on community forestry in Cameroon:

the grouping of communities in a community forest makes the implementation of a simple

management plan more viable and existing structures within the communities should be reinforced.

The project has contributed significantly to the current level of experiences, equipped the forest

authorities with basic materials and prepared a draft for the community forestry decree.

The second community forestry project in the DRC was named Forêts du communautés locales or

FORCOL, implemented by Forest Monitor from 2009-2010 throughout the country (Figure 3). This

project was implemented by civil society and determined the necessities of communities in relation

to community forestry and to identify the barriers on the way of obtaining them. FORCOL applied

different participatory methods like group discussions at communal and other levels of governance. It

also used participatory mapping to include traditional forest and uses in the process. FORCOL has

provided an overview of the values of forests for local people, the conflicts and the implications of the

implementation of CF for the DRC. The main conclusions of the discussions were; (1) the country is so

diverse in culture and ecology that the applied CF model has to be sufficiently flexible to adapt to local

circumstances, (2) the minimum size for a community forest to fulfil all the necessities of the forest

dependent communities is 50,000 ha, and (3) there are a high number of internal and external conflicts

in and around community forest stakeholders. The project has produced an overview of the strengths,

weaknesses, opportunities and threats of CFM in the DRC (Annex II), which indicates significant

challenges ahead (Forest Monitor 2010). The DRC faces substantial governance issues, and Forest

Monitor has expressed doubts whether community forestry is realistic and feasible in the national, or

that it might be the most appropriate model in this context (Forest Monitor 2010). The project

FIGURE 3 LOCATION OF FORCOL PROJECTS IN

THE DRC (FOREST MONITOR 2010)

16

produced a draft of the community forestry decree, which has undergone significant changes by the

authorities, before acceptance in August 2014 (Theophile Gata 2015, Pers. Comm.).

The third and ongoing project by the GIZ forest and biodiversity programme PBF implements a pilot

community forest concession, in Kailo near Kindu the capital of the province of Maniema. The project

consists of three phases: (1) studies and participatory mapping of project area, (2) elaboration and

validation of the forest management plan and (3) implementation of the community forest

management plan. In March 2015 the first two phases had been finished (Ousman Hunhyet 2015 pers.

Comm).

Local commissions and councils have been formed to represent the community and to make decisions

regarding the forest management. These commissions are also responsible for the validation of the

forest management plan. The model aims to convince the informal local small scale timber operators

to formalize their activities and to participate in sustainable forest management. The project faced

problems during the first phases to explain the methods, procedures and expected results to the

involved actors on all governance levels. These barriers were overcome with additional sensitisation

and the implementation of a micro model of two hectares within the pilot concession to demonstrate

that the model works in reality. The formalization process of informal timber operators results in

additional costs for the operators in form of paperwork and bureaucratic processes. The project aims

to compensate the additional costs of small scale operators with increased working efficiency and

timber quality as a result of the use of mobile sawmills. 15% of the returns from timber production

are to be transferred to a community fund. The PBF has recommended communities to use 60% of

this fund for socio-economic infrastructure, 20% for the functioning of the commission and 20% for

the renovation of the forest stock. This are however recommendations and the final decision remains

in hands of the local commission (Ousman Hunhyet 2015 pers. Comm).

COMMUNITY BASED NATURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PROJECTS Community based natural resource management is defined as “a process by which landholders gain

access and use rights to, or ownership of, natural resources; collaboratively and transparently plan

and participate in the management of resource use; and achieve financial and other benefits from

stewardship” (Child and Lyman 2005). The implementation of the CBNRM concept is a form of

participative management of common pool resources, which according to (Ostrom 2009) requires the

creation of new, or improvement of existing, institutions to guarantee equitable and sustainable

resource management. Community forestry is a form of CBNRM and includes similar processes such

as resource planning, capacity building and institution building. As a result of the relation between

CBNRM and CF, lessons can be learned from the one to be used in the process of the other. The

following projects are self-declared CBNRM projects, this may or may not be correct by definition.

Objective literature was often missing to compare design with the definition.

TAYNA COMMUNITY RESERVES

Natural resources managed by communities through community reserves is a relatively new

phenomenon in the DRC. One of the first examples is the well-known Tayna community nature reserve

in the East of the DRC. The reserve was found largely on the initiative of the local communities and

have been relatively successful. The Tayna nature reserve was formally recognized in 2006, when the

communities entered into long term management contracts with the government. It has been

supported with REDD funds along the way (Bofin

et al. 2011; Mukulumanya et al. 2014). The

Reserve is located between the Maiko national

park (NP) in the North, the Kahuzi-Biega NP in the

South, and the smaller Virunga NP in the East

THE TAYNA COMMUNITY RESERVE SHOW THAT

LOCAL INITIATIVES, BACKED BY THE

GOVERNMENT AND INTERNATIONAL SUPPORT

CAN BE SUCCESSFUL, AND INSPIRE OTHERS

17

(Annex III), and thus fulfilling an important role as biodiversity corridor. The area is a biodiversity

hotspot and contains endangered primates such as the Lowland Gorillas Gorilla beringei graueri and

Chimpanzees Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii.

In 1998, local groups, formed NGO´s to engage in community based conservation to preserve

biological heritage and stimulate development (Mukulumanya et al. 2014). The area between the

protected areas have seen heavy demographic changes as a result of displacement due to recent

armed conflicts (CBFP, 2006).

The creation of the reserve coincided with participatory land use mapping and capacity building.

Through participatory mapping and land use zoning 900km2 became protected, while other areas

were designated as buffer zone or development zone. The process also included significant amounts

of education and awareness-raising of local communities, including the development of a scientific

programme for monitoring and protection. For which a local university was founded. The local

initiative has gained momentum and after Tayna five other communities formed local NGO´s, which

later joined together in a union to enter in a similar process to create the Kisimba-Ikobo Nature reserve

(Mukulumanya et al. 2014). The effects of these community reserves on local biodiversity have been

positive since the data of monitoring since 2002 indicates an increase in wildlife encounter rates

(Mehlmann cited in Debroux et al. 2007).

The long term sources of financing for the community conservation project is ecotourism. This has

been rather problematic due to the lack of tourism as a result of the armed conflicts in the region.

Other problems are infrastructural and logistical as well as insecure tenure rights that may potentially

cause conflict between formal and customary law (Mukulumanya et al. 2014). Overall show the

projects that community conservation can form a base for local development initiatives and can be

successful when recognized formally and enforcement by local stakeholders (Mehlmann cited in

Debroux et al. 2007).

PARTICIPATORY LAND USE MAPPING IN THE MONKITO CORRIDOR

One of the first steps of community based natural resource management, and often of community

forestry is participatory mapping. Mapping allows communities to more effectively manage their

resources on a community base, and to reduce conflicts with other stakeholders. The importance of

participation of communities in the process of land use planning has been underlined in other parts

of the Central African Regional Programme for the Environment (CARPE) programme. Their national

macro-regional land-use planning was based on satellite images and excluded many traditional forest

such as customary rights and hunting or certain cultural values given to an area. The reason for

exclusion was that they were not invisible on remote sensing images. The programme faced similar

problems on a micro level in the Lake Tumba landscape when the project experienced strong

opposition to micro-zoning activities, as it was perceived as efforts to limit their access to land and

resources. This underlines the importance of self-determination of communities over their resources,

in contrary to external conservation objectives (Eisen et al. 2014).

Participatory land use mapping was done in the Salonga-Lukenie-Sankuru (SLS) Landscape, Equateur

province, in the framework of the USAID CARPE. The SLS landscape consists of two parts of the Salongo

national park with the 40km wide Monkito corridor between them (Annex IV). The corridor covers

104,144 km2 and is inhabited by 176 villages with

nearly 200,000 inhabitants depending for 100% on

the natural resources especially NTFP collection,

hunting and agriculture (de Wasseige et al. 2010).

Such demographics and socio-economics near a

natural park underline the importance of land use

planning. The objective of the land use planning in

FOR COMMUNITIES TO ENGAGE IN

SUSTAINABLE LAND USE CLEAR

CONTRIBUTION TO ECONOMIC BENEFIT OR

CONTRIBUTIONS TO POVERTY REDUCTION

MUST BE VISIBLE

18

this area is the same as the overall CARPE objective “Reducing the rate of forest degradation and loss

of biodiversity through increased local, national, and regional natural resource management capacity”

(Yanggen et al. 2010: 162).

Important lessons from the project have been according to Yanggen et al. (2010); (i) clear contribution

to economic benefit or contributions to poverty reduction must be visible for communities to engage

in sustainable land use, (ii) for land use planning within CBNRM zones to have a long term beneficial

effect the security of land tenure should be improved, (iii) there is a need for capacity building of local

people to facilitate their participation in national processes, (iv) if women are important players in the

change of the community adapted strategies should be developed to ensure their inclusion.

THE INTEGRATED REDD+ PILOT PROJECT IN ISANGI

The integrated REDD+ pilot project in Isangi in the Orientale province is being implemented by the

NGO OCEAN under supervision of the ministry of environment, nature conservation and tourism. It

contributes amongst others to the REDD+ objective “Targeting and transfer of management of

"Protected forests" to local communities” (Bofin et

al 2011). The project aims to reduce deforestation

and poverty, through integrated rural

development, land use planning, community forest

management and the management of forest activities in the permanent production forest (Mpoyi et

al. 2013). The project consisted out of two components; (i) community forest management and, (ii)

livelihoods and development. The forest management component consisted mainly of land use

planning through participatory mapping, agroforestry and reforestation. While the development

component consisted of increased agricultural production and vertical integration. The project faced

problems are: (1) problems with sensitisation of the communities due to the abstractness of the

underlying theories of REDD+, and (2) frequent elite interventions on various levels of governance

with the aim to capture rent (Cyrille Adebu 2015 pers. Comm.). Elite rent capturing is a frequently

returning issue and forms a risk for the implementation and continuity of REDD+ and community

forestry.

EQUATEUR REDD+ PROJECT WOODS HOLE RESEARCH CENTER

The REDD+ project implemented by the Woods Hole Research Centre in Gemena in the north and

Mbandaka in the central region of the Equateur province found out that local customary institutions

(norms, cultural values, routine habits, mode of conduct and appropriate action) governing access and

user rights to land and forest resources are essential during the implementation phase of community

based natural resource management. Social capital was considered one of the determining factors for

self-compliance with locally developed forest

management norms, and thus reduce the costs of

governance. Based on this notion the project

recommends that capacity building should focus

integrally on the strengthening of social capital. This

is especially important in the DRC where social capital is low as a result of ethnic tensions. Social capital

describes the interactions between people and is determined by the level of mutual trust, norms of

interaction, social relationships and networks, and by the collective benefits derived from

cooperation. Furthermore, the project has shown that communities are heterogeneous and consist of

groups of stakeholders with different interests and opinions. Causes for the low social capital include

mistrust, inter-group conflicts, ethnicity and low voluntary participation. The limited voluntary

participation were found to be caused by low socio-economic status, and the NGO´s practice of

payment of allowances for participation (Samndong et al. 2011).

GOVERNANCE ISSUES AIMED AT ELITE RENT

CAPTURING FORM AN OBSTACLE AND RISK

FOR REDD+ AND COMMUNITY FORESTRY

LOCAL CUSTOMARY INSTITUTIONS ARE

ESSENTIAL DURING IMPLEMENTATION AND

SOCIAL CAPITAL IS ESSENTIAL FOR SELF-

COMPLIANCE WITH NRM NORMS

19

MAÏ NDOMBÉ REDD+ PROJECT

Since 2010, WWF is implementing an integrated REDD+ project in the Maï Ndombé district, Bandundu

province. The project has several internal objectives to contribute to the development of REDD+ in

the DRC: (1) to ensure the effective participation and address their rights in a way that reduces

poverty, (2) to demonstrate pathways to zero net deforestation and degradation in Maï-Ndombé,

while managing carbon stocks and other conservation values effectively, and (3) delivering benefits to

indigenous people and local communities (WWF 2012). The project contains the following elements:

(1) micro-zoning of community land for improving land tenure, (2) strengthening local governance, (3)

empowering local communities, and (4) designing possible approaches to benefit sharing (WWF 2012).

Several lessons were learned by the Maï Ndombé REDD+ project. Most of them are highly relevant in

the REDD+ framework, and equally important for the implementation of community forestry:

Local communities need to be sensitized prior to being asked to take action

Activities need to be officially recognized by the government to facilitate scale-up

Being a good partner enables you to be part of all levels of the REDD+ dialogue

For REDD+ to be successful, it is essential to link the local with national and global needs.

It is important to develop methods and tools for Free Prior Informed Consent early in the

REDD+ process.

Local governments need to be strengthened so it is possible to engage them effectively.

When working at the community level, it is important to have a close relationship with both

the people and local authorities

For REDD+ success, it is essential to scale up activities and link the local with national and

global needs.

Stakeholders from different sectors should be integrated early on in the REDD+ process for it

to be successful

Targeted stakeholders need to be empowered so they can take the lead on the REDD+

process

Civil society activities need to be recognized officially by local, regional and national

authorities.

Participative land use mapping is the first step towards securing community land tenure to

stop deforestation (WWF 2012:44-45)

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

LESSONS LEARNED FROM COMMUNITY FORESTS AND COMMUNITY BASED NATURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT IN THE CONGO BASIN The combined experiences in participatory natural resource management in the Congo basin provide

valuable lessons for the implementation of community forestry in the DRC. The analysis of these

experiences has produced several prerequisites for successful implementation, which have been listed

in this chapter.

COMMUNITY FORESTRY HAS POTENTIAL

The Cameroonian model has shown that community forestry only produces limited economic benefits

for community development when restricted by law. However it can provide an opportunity to

increase the social and human capital. This requires permanent links and lasting relationships with

external partner, without creating a patronage system in which the community become dependent

on external support. The gradual transfer of capacity to local institutions is essential for communities

to become independent. Internal discussions are needed under the supervision of local formal

20

organizations to establish the forest uses in the community forest area and to plan collective

investments. This requires capacity building within the community, provides opportunities for better

management of forest revenues and increased access to development and conservation partners

(Lescuyer 2013). Even though in Cameroon the experiences have not met expectations, community

forestry should be considered as a process and not a fixed model (Michael Vabi 2015, pers. Comm.).

THE LEGAL FRAMEWORK NEEDS TO BE COMPLETED

With the signing of the community forestry decree in 2014 the DRC took an important step towards

the implementation of community forestry. However, the region is notorious for delaying the

implementation of community forestry due to incomplete legal frameworks, and the DRC is no

exception. At the time of writing the work on the technical directives (arrêt in French) was still

ongoing, and the completion and ratification of these documents are required before community

forestry in the DRC can be formally recognized and implemented on a larger scale

LAND TENURE NEEDS TO BE SECURED

One general problem with pilot projects and CBNRM zones at this stage is that they have a weak legal

basis and are thus susceptible for reclassification into other land uses (Eisen et al. 2014). Several of

the above mentioned initiatives identified the lack of secure tenure as a threat to the continuity of the

projects, and as a barrier for the large scale implementation of CFM in general. Research in Latin

America and Asia shows that community forests obtain the best results when models are based on

widely recognised, legally-enforced and secure rights and allow communities themselves to establish

and enforce rules governing the access and use of forests (Eisen et al. 2014). The community

concession decree provides more secure tenure since the concessions are perpetual, but further steps

of the implementation of CF´s will be decisive for the stability of the provided security. The decree

mentions that communities have the right to outsource the management or establish conservation

efforts. This could be abused by external parties to gain rights and power over community concessions,

thus failing to meet the community forestry objectives. However, a forest concession only hands over

the temporary rights over the forest, not the land. It is a rental contract, without transfer of ownership.

This may cause problems during the implementation of payments for environmental services, such as

REDD+ (Seyler et al. 2010). To prevent these kind of problems land tenure rights should be

strengthened in the ongoing national land reform processes.

THE DRC IS TOO DIVERSE FOR A “ONE SIZE FITS ALL” APPROACH

The DRC is very diverse, demographically, culturally and ecologically. The requirements for community

forests differ from one area to another. Customary land tenure and intensity of land use in Bas-Congo

province are different from for instance in Equateur. Cultural differences related to gender equality

may inhibit the participation of women in one region, while it is essential in another. Therefore, should

the community forestry model and legislation be flexible enough to allow adaptation to the local

cultural and ecological differences.

CUSTOMARY INSTITUTIONS NEED TO BE RECOGNIZED

The recognition of customary institutions is crucial in any system of forest management, but needs

not to be overly complex or bureaucratic (Long 2010). The level of diversity of customary rules in the

DRC is high. In Cameroon, the traditional resource access arrangements were not sufficiently included

in the new system resulting in conflicts and informal exploitation. To prevent conflicts, external abuses

and elite rent capturing, and to ensure equitable benefit, should customary institutions be included in

the new resource access arrangements. The system for the DRC should be flexible enough to respect

the customary rules, yet clear enough to be enforceable. (Fomete et al. 2001).

21

RIGHTS OF VULNERABLE GROUPS NEED TO BE GUARANTEED

The initial stages of community forestry in Congo basin faced significant shortcomings regarding the

involvement of stakeholders. In Cameroon, the exclusion of stakeholders has resulted in conflicts and

violence. To ensure the participation of vulnerable groups the Commission des Forêts de l’Afrique

Centrale (COMIFAC) issued the Sub-regional Guidelines on the Participation of Local Communities and

Indigenous Peoples and NGO´s in Sustainable Forest Management in Central Africa (Assembe-Mvondo

2013). Additionally, from the experiences in Cameroon the inclusion of women, through the

promotion of NTFP processing and commercialization, has been recognized as a contributor to the

economic and ecological sustainability of CF´s. The experiences from Gabon shows at present little

involvement of youth, despite the large potential of CF´s for this group. Eisen et al. (2014) clarified

that not every decision needs to be taken by everyone all the time, but representation of social, ethnic

and gender diversity is needed to ensure the spread of choices between options.

NATURAL RESOURCE PLANNING NEEDS TO BE PARTICIPATORY

The majority of the experiences have underlined the importance of participatory approaches. This is

in line with Kellert et al. (2000) who stated that participatory approaches in community forestry are

considered to produce; increased benefits for the local community, capitalize on local knowledge,

encourage voluntary compliance, trigger innovation and create economic social and ecological

sustainability. Additionally, participatory approaches create social capital, which was identified by one

of the projects as a key to a successful implementation, and should receive a more attention in projects

in general. The creation of social capital within the community may be a costly process, nevertheless

it saves costs on the long term.

SOLUTIONS FOR INDIVIDUAL SMALL SCALE LOGGING ARE NEEDED

By some experts has the, largely informal, small scale logging sector been considered the largest threat

to community forestry and thus needs to be addressed. It is a global problem that communal forest

exploitation often faces strong competition from small scale more individualistic forms of timber

exploitation (Lescuyer 2013; Cano et al. 2014). Community forests are a common resource pool and

thus apply the Ostrom principles which among others; require clarification of rights and duties, and

increased (community) monitoring and sanctioning, as a part of the means to address these issues

(Ostrom 2009). To formalize the informal small scale loggers, and increase their participation in the

formal economy it should be facilitated by creating framework conditions where compliance is a more

attractive choice than non-compliance. This means that the legal procedure of obtaining the legal

documentation must be facilitated, and community and state enforcement of norms and rules

increased. Tools have been created that aiding community monitoring. The further development and

up scaling of bottom up monitoring can assist the forest authorities to enforce forest regulations.

REDD+ CAN BE COMBINED WITH COMMUNITY FORESTRY

For REDD+ are community forests of major importance since they are located in the areas where the

bulk of the deforestation is occurring, along roads, near infrastructure with already degraded forests

that is more vulnerable to fires and attractive for shifting cultivation. In these areas additionality of

REDD+ payments is extremely high (Karsenty et al. 2010). PES can be used to promote sustainable

forest management in community forests. It should be based on “asset building” instead of “land-use

restriction”, based on investment in sustainable land use while halting unsustainable land uses. It also

would include value chain development, intensifying crop production and modification of agricultural

practices, diversification of the local economy (Karsenty et al. 2010). Furthermore, many of the

underlying problems, e.g. good governance, need to be addressed for both concepts, thus the

implementation of REDD+ and community forestry can result in a synergy.

22

GOVERNANCE NEEDS TO BE IMPROVED

Forest Monitoring showed doubt whether community forestry is possible in the DRC, due to the large

governance issues the country is facing. According to Bofin et al. (2011) is the underlying problem of

the DRC´s governance a “dysfunctional state-society relations”. In both renewable (forests) and non-

renewable (minerals) the DRC is facing the consequences of a system that chased away the operators

and rewarded the bad ones. Also the tradition of using positions within public administration to access

informal taxes and fines is persistent within a too large and underpaid bureaucracy, which will

negatively affect the efficiency of donor money for community forest establishment. The fiscal system

is split among various bureaucratic entities with a poor record of information sharing. External

attempts for improvements have been met with considerable political resistance, and tracking

revenues from the forest sector is hard due to poor data collection. Distrust between various levels of

governance fuels lack transparency and reduce the revenue distribution from bottom up. Public

accountability institutions face political marginalization, leading to lack of financial and informational

resources. The formal institutions in the DRC are woven with informal and customary authority,

complexly woven together in unspoken rules and codes of conduct which are often overlooked in

reform processes (Bofin et al. 2011). Improved governance is required for community forestry and

REDD+ to be successful, the clustering approach from Cameroon may contribute to improvement on

the lower governance levels.

ELITE RENT CAPTURING SHOULD BE PREVENTED

In Cameroon, many local forest management committees have been dominated by local elite, while

other groups were excluded (Oyono 2004). This leads to elite rent capturing which in turn leads to: 1)

exclusion of groups by a select group, and unbalanced circulation of information and awareness of

opportunities; 2) reinforcement of existing unequal power relationships 3) continuation of economic

inequity at the expense of those who benefit the least (Eisen et al. 2014). Furthermore, equitable

benefits sharing is an important component of conflict reduction, and thus improves the livelihood of

community members.

ACCOUNTABILITY IS NEEDED TO PREVENT CONFLICTS

To prevent internal conflicts a high level of accountability and transparency over the forest revenues

is required. A simplified community investment plan can help achieving this, but is only effective when

the plan is being followed. This requires significant investments in capacity building, but contributes

to the prevention of elite rent capturing and future conflicts, and ensures equity. When conflict do

exist local NGO´s are important actors in the conflict resolution process.

SUPPORT FOR COMMUNITY FORESTRY SHOULD MEET THE THRESHOLD

The case of Cameroon has shown that external support must meet a certain threshold to be effective.

External support can partially help communities to overcome the barriers of distance, given that the

aid is of sufficient scale, intensity and length. It should include administrative assistance and capacity

building in administrative management. If support that does not meet the threshold, or that is not

long enough to obtain sufficient experience, the result may be worse than no assistance at all. It may

result in a more dominant role for industrial operators in community forestry by gaining access to

forest that otherwise would be inaccessible and increasing their own benefits at the costs of the

community's. Furthermore, distant communities require more external support, than communities

closer to urban areas (Ezzine de Blas et al. 2009). Relations between industrial logging companies and

communities have been notoriously bad, and increased dependency from communities on logging

companies as a result of insufficient support could be an undesirable side effect of external support.

Aquino and Guay (2013: 78) wrote the following about the implementation of REDD+ which is also

true for community forestry: …. “is likely to achieve its overall goals only if reliable long-term

23

performance-based sources of financing are available to the country, with a strong element of

conditionality against measurable and observable milestones. Given the country's poor infrastructure,

low level of social capital across forest communities and weak overall capacity of the local and national

governments, projects will also face important challenges in successfully conducting those activities

that are envisaged to reduce emissions. Finally, the limits to projects are well-known — their scope of

action is usually limited to time-bound activities addressing direct drivers of deforestation. They are

unable to design and enforce public policies favorable to forest conservation (land tenure clarification,

territorial planning, basic infrastructure development, education and health policies, and so on)”

FOREST USES OTHER THAN TIMBER SHOULD BE TAKEN INTO ACCOUNT

The Cameroonian community forestry model was largely focused on timber production, which turned

out to be a weakness when commercialization of timber was problematic on both the national and

international market. Meanwhile the collection of NTFP´s (e.g. caterpillars and bush meat) showed to

be important for subsistence and income (Beauchamp & Ingram 2011). The addition of these products

in the forest management planning, and the representation of their producers in committees

contributes to food security and economic diversification and development of the community.

Furthermore, are the NTFP collectors often women, and their representation in the elaboration of the

forest management plan would improve their social status and future income opportunities.

INFORMATION SHOULD BE SHARED

Experiences with community forestry pilot projects is still limited. The long term benefits from pilot

projects should go beyond their own implementation, and form a knowledge base for future

developments. The publication of data on the challenges and lessons learned, is essential for the

community forestry process at this stage. Each experience produces useful lessons when they are as

limited as in the DRC, and thus need to be shared for the common good. Civil society has proposed a

round table in which a balanced representation of the various sectors are able to discuss important

topics, share information and contribute to the overall process of community forest management in

the DRC.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to thank the following organizations and persons for their time and effort that

form the basis of this report. I would like to thank the following persons and organisations for their

provision of information: Theophile Gata Dikulukila of CAGDFT, Matthieu Yela Bonketo of CEDEN,

Martijn Ter Heegde of GFA group PBF/GIZ, Cèdric Vermeulen of Nature+, Cyrille Adebu of OCEAN,

Michael Vabi of SNV, Quentin Meunier of WWF/Nature+, Mr. Inoussa of WWF and the DFS forest

technician Ousman Hunhyet working for PBF in Kindu. Furthermore, I would like to thank Joe Eisen,

Simon Councell, Martijn Ter Heegde and Dominique Bauwens for reviewing and commenting on the

report. And Rodrique Yake for translating the abstract.

24

REFERENCES

African Community Rights Network (2014): FLEGT, REDD+ and community forest and land rights in

Africa: lessons learned and perspectives. Study report African Community Rights Network.

Aquino, A.; Guay, B. (2013): Implementing REDD+ in the Democratic Republic of Congo: An analysis

of the emerging national REDD+ governance structure. In: Forest Policy and Economics 36, S. 71–79.