Close knit or loosely woven? Unravelling the quotidian geographies of voluntarism: a case study of...

Transcript of Close knit or loosely woven? Unravelling the quotidian geographies of voluntarism: a case study of...

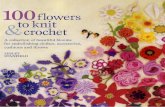

Close knit or loosely woven?

Unravelling the quotidian geographies of voluntarism: a

case study of Operation Christmas Child.

BA Geography

Final year: 2012

Candidate number: 642537

Word count: 11,928

ABSTRACT

Volunteering is a long-standing phenomenon of immense socio-economic value and, currently, significant political purchase. This study departs from the recent proliferation of debates concerning its national political deployment, in order to considerhow and with what consequences landscapes of volunteering are shaped by locally lived volunteer lives. Drawing on geographical work on morality, care and giving, it focuses on the often neglected spaces of individual lived experience, exploring how these help constitute and come to be constituted by the practices,performances and experiences of volunteering. In order to achieve this the study centralises volunteers empirically, through a case study of Operation Christmas Child, a children's charity which enables volunteers to send wrapped shoeboxes of gifts to disadvantaged children overseas. Utilising several innovative participation-based methods, including participation in knitting circles and volunteering in an OperationChristmas Child warehouse, the research explores how practices of volunteering are inseparable from individual ethics and imaginaries. This leads to a consideration of the situation of both volunteering and volunteers with regard to the (re)productionand negotiation of various social power structures. The study highlights the particular affective significance of embodied connection and banal, quotidian performances to the production of ethical meanings through volunteering. It demonstrates how these interconnect enabling investments in individual identities and practices of care for the self, such as catharsis, feelingful reflection and meaningful relationships. As a result, the multifaceted, dialogic relationship between volunteering and ordinary, personal lives is stressed, which suggests that a redefinition of volunteering would be beneficial which considered more equally its capacity to 'touch' volunteers as well as recipients. It is recommended that current work on voluntarism would benefit if greater attention were paid to the complex spatialities of such touching. To consider the

cartographies of voluntarism and everyday life separately would deprive understandings of both.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to say a huge thankyou to all those who have

helped me through this project: Firstly, to the volunteers from

Wedmore Parish churches and the surrounding area for sharing part

of their lives with me and particularly Valda for knitting with

and teaching me so much. Secondly, to Hilary McFall and all the

ladies at Wiltshire warehouse for welcoming and caring for me.

Your example of love is one that I hope many people will follow.

Thirdly, to Professor Paul Cloke- for giving his time to help a

stranger and a wonderful demonstration of 'ethical citizenship' (Cloke et

al. 2007) in action!

Finally, I would like to thank Frances, whose patience has

been unending, advice invaluable and whose kindness has

continually amazed me. I couldn't have done it without you.

DEDICATIONThanks be to my Heavenly Father, El Elyon.

'He is good; his love endures forever' (2 Chronicles 7:3).

CONTENTS

Page

1 Introduction 01

2 Volunteering and its geographies

03

2.1 Volunteering in context

2.2 Moral geographies and volunteering

2.3 Volunteering motivations: ordinary ethics and care

2.3.1 Ordinary ethics

2.3.2 Care

2.4 Practising volunteering: embodied performance, affect and

giving

2.4.1 Embodied performance and affect

2.4.2 Giving

3 Methodology 14

3.1 Study context

3.2 Methodology overview

3.3 Semi-structured interviews

3.4 Participation-based research

3.4.1 Warehouse volunteering

3.4.2 Knitting

3.5 Positionality

3.6 Ethics

Research findings

4 Actualising ordinary ethics in the spaces of

volunteering 22

4.1 Networks and connectivities

4.2 The effects of ordinary ethics

4.2.1 Faith

4.3 The perplexing nature of giving spaces

4.4 Summary

5 Creating and connecting voluntarism's spaces: the

30 significance of embodiment

5.1 Embodied practices of knitting

5.2 Performances of care through shoeboxes

5.2.1 The affects of performance

5.3 At the nexus of ethics and embodiment: the haptic

geographies of voluntarism

5.3.1 (Dis)connection and responsibility

5.4 Summary

6 “That box is so powerful really isn't it?” The (re)production 38

and negotiation of power structures in voluntarism.

6.1 Power amongst volunteers at Wiltshire warehouse

6.2 Neocolonialism in OCC

6.2.1 Critical and postcolonial voluntarism

6.3 Summary

7 Conclusions

45

7.1 The skeins of ordinary ethics

7.2 Knitting (two) together: the significance of embodied

performances

7.3 Weaving in and casting off power structures

7.4 Tying up loose ends: suggestions for further research

Chapter 1 Introduction

“You can call it empowerment. You can call it freedom. You can call it responsibility.”

David Cameron's (2010) comment refers to the much-publicised Big

Society, his 'mission in politics' (Sparrow, 2011) 'unleashing social energy'

by encouraging Britons in collective 'stimulating pursuits' (The Big

Society Network, 2011). Volunteering is one such engagement,

encouraged to achieve a coming “together in... neighbourhoods to do good

things" (ibid). Generally, volunteering- formal and informal-

constitutes far reaching and variegated networks, facilitating

ethical performances and close relationships across local,

regional and national boundaries. Consequently it is a widespread

and enduringly popular phenomenon pursued for its benefits both to

recipient and volunteer.

At a time when voluntarism is receiving considerable political

attention, this study inspects geographical work on volunteering,

combining it with that on moral geographies, care and giving. It

departs from work by Cloke et al. (2005; 2007; 2010) on volunteering

in homelessness services. These authors explore how quotidian

moral influences source volunteer motivations and inspire

particular practices which co-construct organisational spaces of

care. They do not, however, consider volunteer practices as

situated in and part constitutive of individual lives; this work

empirically centralises volunteers themselves, investigating how

volunteering is lived and part of personal lives. How and with

what spatial consequences are volunteering practices experienced

phenomena, enmeshed with volunteers' daily lives? To answer this,

1

three questions are posed:

1. What 'ordinary ethics' (Barnett et al., 2005) and imaginaries are

brought to volunteering and how are these actualised spatio-

temporally?

2. What significance does the embodied nature of caring

practices have in volunteering and for volunteers themselves?

3. Do volunteers' motivations or practices (re)produce any power

structures and/or is there evidence of more critical

voluntarism, by which structures can be negotiated?

By posing these questions in a study of the charity, Operation

Christmas Child, this work seeks to address that “little is known on

volunteer experiences” within geography (Pearce, 1993) and improve

understandings of the significance of volunteering for volunteers

personally, volunteering itself and its study. It is additionally

intended to enable discussion about contemporary readings of

volunteering- whether participants can be considered selfish,

government-controlled neoliberal puppets (Peck and Tickell, 2002),

or whether the entanglement of volunteering with everyday lives

transforms its practices and ethical meanings, making it more

relational and emotional (and part of the resistance against

neoliberalism) (Cloke et al. 2010).

This research is conducted in a novel way: participatory

techniques of knitting, sewing and other volunteering practices

are used. Involvement was sought to facilitate interactions with

participants and more personal, holistic understandings of

volunteering than those possible through interview-based

2

techniques alone. The research is arranged as follows: firstly

relevant literatures are reviewed, then methods employed are

explained. Three chapters then outline some emerging themes, which

are synthesised in chapter 7, with reflections upon their

implications and suggestions for further research.

Chapter 2 Volunteering and its geographies

2.1 Volunteering in context

Whilst the origins of volunteering remain mysterious, for

millennia mankind has surrendered time serving others in ways

innumerable and of value immeasurable. Such service remains

popular; from 2008-2009 41% of Britons volunteered at least once

annually (Drever, 2010). Volunteering is also economically

3

valuable; in 2001, the aggregate value of US volunteer hours was

$239bn (Chambré and Einolf, 2009). Yet despite this significance,

'volunteering' defies simple definition; it can be an offer to do

something, work without payment, or action independent of

government (Salamon and Sokolowski, 2001). Varied comprehensions

lead Kendall and Knapp (1995) to call volunteering 'a loose and baggy

monster'. Handy and Hustinx (2009) relish this complexity, terming

it a 'kaleidoscope concept', with dynamic contextual 'pictures every time the

field shifts'. A simple, initial definition is:

“any unpaid activity where someone gives their time to help an organisation or an

individual” (Fitzgerald and Lang, 2009).

Volunteering is of considerable public interest and social policy

relevance, particularly because of its shifting position vis-a-vis

the state. Support from successive governments since the 1980s, in

the context of rolled-back state support for service provision,

has led to the increasing prominence of the voluntary (or third)

sector (Edwards and Woods, 2006) and its broad acceptance as a

form of governance alongside other community structures (Parsons,

2006). Most recently David Cameron promoted voluntarism within the

Conservative Party's 2010 flagship policy idea, the Big Society.

This was billed a 'huge culture change', devolving power to society to

help 'their own communities' (Cameron, 2010). £500m funding has been

promised- 'every penny of dormant bank and building society account money

allocated to England' (King, 2010).

Volunteering has also received significant academic attention.

Research foci include general sector characteristics (Boris and

4

Steuerle, 2006), volunteer motivations (Wilson and Musick, 1999)

and personal characteristics (Gallup organisation, 1987). However,

accounts are 'largely aspatial' (Fyfe and Milligan, 2004). Within

geography, voluntarism is deemed a 'lost continent' (Salamon et al. 2000)

lacking literature. Despite this, some varied works have recently

emerged. One collection, Landscapes of voluntarism (Milligan and

Conradson, 2006), exemplifies this variety, with topics ranging

from rural community governance to charity shop

professionalisation. Throughout such accounts, a particular

cluster of views prevail. Firstly, volunteers are conceptualised

as cheap service providers, addressing needs originally met by the

welfare state (Edwards and Woods 2006). Secondly, voluntary groups

are considered 'little platoons” (Peck and Tickell, 2002) of neoliberal

governments, their actions directed via financial contributions

and policy pressures. Cameron has acknowledged this view, calling

public sector workers 'weary, disillusioned puppets of government targets'

(2010), needing empowerment by the Big Society to 'come together and

improve life for themselves' (Conservative party manifesto, 2010). Finally,

volunteers are thought selfishly interested in 'moral selving'-

creating themselves 'more virtuous and often more spiritual' (Allahyari,

2000:4). Collectively, these views depict volunteering negatively.

Their considerable political influence justifies these views'

importance for critical study.

2.2 Moral geographies and volunteering

Unlike volunteering, geographers (e.g. McDowell, 1994) have

5

considered moral philosophy extensively, particularly since the

'moral turn' of the 1990s (Smith, 1997). Smith (ibid) asserted

that 'nothing much is lost' if morals and ethics both mean judgements of

conduct as right/wrong or good/bad. Proctor (1998) however

distinguishes ethics as:

“systematic intellectual reflection on morality in general- morality being... the realm of

significant normative concerns, often described by notions such as good or bad, right or

wrong, justified or unjustified”.

Morals influence daily living, since morality is conceived and

enacted (Smith, 2000:10). Entrikin (1991) consequently saw 'moral

geographies' as the social relations constituting communities and

their practices. More broadly however, moral geographies refer to

any 'interrelationship of moral and geographical arguments' (Matless, 2009)

including the influence of places upon moral sensibilities, vice

versa and geographies of morals. Shared morals can create the 'we-

feelings' (Cloke, 2002) of community, although established

simultaneously are those not sharing feelings- excluded Others.

Such exclusion was examined by Cloke, May and Johnsen in their

Homeless Places Project. There, they encouraged volunteers to be

sensitive to senses of Others (Augé, 1998) and have senses for them,

that are reflexive, emotionally connected and committed to them.

Their project inspired several papers (2005; 2007) and the book

Swept Up Lives (2010). The authors (2005) examined organisational

ethoses in homeless centre discourses and argue that, unlike

volunteering influenced by Christianity or secular humanism,

'postsecular' volunteering had a non-oppressive sense for Others and

6

would likely arise in quotidian volunteering performances. These

performances are explored alongside volunteers' motivations (2007)

to assess how workers co-construct care spaces. Performances are

considered products of specific motivations and influential of

constructions of and interactions with homeless Others. This

approach enables comment on the disadvantages of third sector

corporatisation, ethically complex motivations and the

performative construction of homeless spaces. However, volunteers'

backgrounds are only considered sources of motivations, rather

than also sites of volunteering. Further, the project neglects

volunteers' lives, focussing on volunteering producing official

care spaces. More could be done to illuminate how and with what

spatial consequences volunteering practices aren't

compartmentalised and isolated from volunteers' lives because they

occur in disposable time- but are intricately interconnected with

them. Smith et al. (2010) do consider this vivacity, calling

volunteering 'situated, emotional and embodied'. However, their work more

highlighted than extensively explored this situatedness and didn't

consider voluntarism's moral dimensions. This study attempts to

fill this lacuna, examining volunteering practices as enmeshed in

their ordinary spatialities. Opportunity may also arise to

contribute to discussions in Swept Up Lives, where, additionally to

challenging conventional representations of the urban homeless,

the authors explore how critical 'postsecular' care is performed

within homeless services 'despite their spatial marginality... stigma [and]

financial tenuousness' (DeVerteuil, 2010). Consequently they argue for

an alternative reading of volunteering to that prevailing (p4), in

which volunteers selflessly establish geographies of relationship

7

and emotion, forming 'part of the resistance against the excesses of neoliberalism'

(Cloke, 2011). This study examines volunteering performances,

considering whether there is support for Cloke et al.'s reading of

volunteers, the conventional view or one altogether different.

2.3 Volunteering motivations: ordinary ethics and care

Volunteering is a lived experience, necessitating

consideration of volunteers' motivations. Their popular

discussions in research however (e.g. Leete, 2006), tend towards

tabulated summaries not repeated here.

2.3.1 Ordinary ethics

This research will consider: what ordinary ethics are brought

to volunteering and how are these actualised spatially? 'Ordinary

ethics' were first conceptualised in Barnett et al.'s (2005) work on

ethical consumption. Ethical consumption is conventionally

considered (in a knowledge deficit model) a consequence of place-

based knowledge prompting the adoption of abstract ethical values.

The authors however re-conceptualise consumers as 'ordinarily ethical',

with their (shifting) ethics forming 'platforms' upon which

impulses for action are developed (Cloke et al. 2007). Associated

with ordinary ethics are learned ethical competencies which

constitute practical consumption habits, partly producing

volunteers' moral selfhoods. Barnett et al. (ibid) add that ethics

can be re-articulated by personal choices ('governing the consuming

8

self') and campaign 'devices' (tools achieving a task- here 'governing

consumption'). By re-articulation, ordinary ethics are made into

exceptional commitments, enabling volunteers to invest in their

own 'ethical citizenship' (Cloke et al. 2007). In this 2007 paper, ethical

performances in volunteering spaces are explored. Here, broad

organisational ethoses aren't solely performed by volunteers;

instead they are transformed through combination (complicatedly

and unstably) with individual ethical commitments to inspire

volunteering practices. Care spaces are partly produced by these

ethoses.

Although useful, Barnett et al.'s (2005) discussion of ordinary

ethics only examine their re-articulation in actor enrolments and

Cloke et al. (2007) only explore how they inspire specific

performances. Here, they are used to understand voluntary

experiences. It is anticipated that individuals are constantly

influenced by multiple ordinary ethics, all potentially

influencing decisions simultaneously (though to different

degrees). Alongside specific ordinary ethics articulated for

particular volunteering practices then, other ethics may also be

influential. This may entangle volunteering practices/experiences

with other ethical competencies, like caring for friends- showing

them as phenomena not isolated in volunteers' lives. Such

connections might modify volunteering experiences, meanings and

specific practices, enabling hybrid demonstrations of moral

selfhoods.

2.3.2 Care

9

The concept of care denotes engaged interest and 'a

reaching out to something other than the self' (Tronto, 1993:102) with (often)

accompanying actions. Geographical work on care originates from

feminist concerns for subalterns and forms their critical

alternative to male dominated ethical theory. Care is relevant here

since volunteering itself is a device used to meet needs, through

which many forms of care are embodied (it is also conceptually

rich owing to its many meanings- including as a motivation and

moral capacity- Jagger, 2000). Different types of care include

benevolent caring about someone (ethical, emotional concern) and

beneficent caring for them (active demonstrations of support)

(Smith, 1998a). Beneficence particularly interests Silk (1998)

because it seeks emotional, committed connection with Others.

Cloke et al. (2005) warn however that even benevolent care may

oppress where practices arise from pre-formed views of Others.

However demonstrated though, care assists the ongoing construction

of voluntarism's 'emotionally heightened spaces' (Cloke et al. 2007).

Since care involves relational connections between carers and

recipients it is inherently geographical- work on landscapes of

care, ('carescapes'- McKie et al. 2002) continually expands and

includes an exploration of the professionalising influence of New

Labour's performance targets upon homeless service spaces (Cloke et

al. 2010). These targets, they argue 'undermined' policies (of the

rationale that the homeless are socially excluded and require

support) that had made 'space for an alternative ethics of care' (ibid:38).

Another discussion of care questions caring 'at a distance'. Currently

a knowledge-deficit model (see p6) prevails, attesting that with

distance, knowledge of ethical responsibilities is lost (Barnett et

10

al. 2005). Thus distance can problematise care, though doesn't

prevent it, because (Corbridge, 1993a:463):

“boundaries are themselves not closed, but... defined in part by an increasing set of

exchanges with distant strangers”.

Barnett et al. (2005) however, argue that proximity-based knowledge

shouldn't be privileged as a conduct motivator. Instead, they

propose that actors' 'ordinarily ethical' competencies are re-

articulated in their enrolment to ethical activities. More

broadly, it has been argued that care can occur, irrespective of

distance, if actors are 'attentive and responsive' (Fisher and Tronto,

1990) to needs. Any impetus, like guilt or generosity, might

suffice, but is unnecessary. Another inspiration of volunteering

(and its underlying ethics) might be moral or political

imaginaries of Others and need. These may arise from ordinary

conversations, images and literature and, additional to ordinary

ethics, may influence decisions to care and consequent voluntary

experiences. This study considers their influence, to improve

understanding of volunteering as woven into volunteers' lives.

2.4 Practising volunteering: embodied performance, affect and

giving

2.4.1 Embodied performance and affect

In addition to volunteers' ethics, performances and their

11

related affects also matter in understanding how volunteering

impacts lives. Performances differ from routine practices- they

accomplish specific tasks, for example, identity enactment

(Butler, 1997). Since ethos partly constitutes identity then,

performances can embody (tangibly express) moral values, affecting

both volunteers and recipients. Furthermore, through their

enactment, 'performative possession' (Bywater, 2007) of space is taken,

helping produce places and moral geographies themselves (Matless,

1994). Cloke et al. (2007) contend that performances of ordinary

ethics particularly create voluntary spaces. Conradson's (2003)

study of a New Zealand community drop-in centre explores this

using actor-network theory. He finds the centre a dynamically

performed network, with continually evolving internal geographies

of relations engendered by myriad performances, which

substantiated space. Whilst some performances were scripted by

rules or training, embodying an institutional order, these (and

others of individuals' initiatives) could have significance in

volunteers' personal lives.

Like Conradson, this research acknowledges the importance of

performances in voluntarism's spaces. However, Conradson focussed

on their role constructing organisational space, here their

significance as experienced by volunteers is explored. Since

Conradson was unaware of 'ordinary ethics' (Barnett et al. 2005)- how

these ethical performances and volunteers' lives enmesh is

examined particularly. Additionally, performances- being embodied

and relational- can reinforce power inequalities like class and

gender ('reproductive volunteering'- Holdsworth and Quinn, 2011) which

cannot be neglected. Such volunteering challenges common

12

assumptions that volunteering is uncontroversial and beneficial

for all involved. Equally, however, embodiment may facilitate

'deconstructive volunteering' (ibid) in which power structures are revealed

and their negotiation attempted.

After using actor-network theory to explore the relational

productions of performance, Conradson (2003) adds that fleeting,

intangible dimensions of volunteering spaces also contribute to

their 'sociability and experiential texture'. These dimensions are atmospheres

of affect (e.g. Tomkins, 1962): a precognitive, neurological

intensity of encounter consequence of the embodied, relational

nature of practices (McCormack, 2008). Affects precede and exceed

cognition, defying representation and forming a mobile, elusive

part of space-time. They are nevertheless influential of

knowledge- forming the 'motion of emotion' (Aitken, 2006), with which

the world is thought, and one way by which affects are transmitted

between bodies (others include sounds, images and objects). One

theory considering affect is non-representational theory (NRT).

Largely developed by Nigel Thrift (e.g. 1999; 2000), NRT

contrasted the Cultural Turn's focus on representations like

discourse, contending that non-representable phenomena like

embodied performances are the principal sources of knowledge, a

form of which is affect (Cloke et al. 2010:66). Affective auras

motivate and modify volunteers' individual and collective

experiences, inspiring and sustaining voluntarism. This influence

accords performances ethical potential- they can encourage the

acceptance of ethical responsibility in the world (Popke, 2009)-

and makes affect of interest here. Considering affective

volunteering performances can help answer the second and third

13

research questions, providing insight into the significance of

volunteering practices as embodied for volunteers themselves and

within larger power structures.

2.4.2 Giving

Since volunteering is a form of giving, concepts from

giving literature may prove beneficial in its investigation. Gifts

involve (Davies et al. 2010):

“selection and transfer of something to someone without the expectation of direct

compensation, but with the expectation of a return”;

they are relational connections partly responsible for societal

'vitality... and identity' (Giesler, 2006). Classically, gifting was

theorised by Marcel Mauss (1923) as a social exchange system with

dyadic structure in which reciprocity was normal (Giesler, 2006).

Mauss' original work, although widely applied, isn't undisputed-

its dyadic structure, for instance, was challenged by Davies et al.

(2010) who propose transactional (additional to reciprocal) giving

in which donor benefits are endogenous, not relational. Defining

giving as a connection, enables its relation to work on haptic

geographies. Typically, geographers have neglected touch for the

gaze (Hayes-Conroy and Hayes-Conroy, 2010) although it is often

vital to individual experiences and general comprehension (Dixon

and Straughan, 2010). The relational connection of touch has

connotations of authenticity that reduce felt distances between

actors; it enables connection between volunteers and Others,

irrespective of geographical distance, destabilising imagined

14

boundaries between internal and external (Stewart, 1999).

Giving can be considered an 'ethical trait' (Cloke et al. 2007)

developed on platforms of ethics like love and care, although

motivations are diverse (including guilt) and have inspired

debates over giving as ultimately altruistic or egoistic. Support

for altruism does exist (e.g. Allen and Rushton, 1983) whilst

others argue that giving is principally selfish; Allahyari

(2000:4) asserts that volunteering is:

“creating oneself as a more virtuous and often more spiritual person... emotional self

work”.

Recently however, this dualism has been challenged. Soper and

Thomas (2006) for example describe an 'alternative hedonism' emerging

in consumption in which consumers altruistically consider factors

like the environment to achieve self-satisfaction; they argue that

altruistic and egoistic motivations are inseparable (see also

Yeung, 2004). More importantly though- since giving relations have

'everything to do with haves and have nots' (Tvedt, 1998:225)- they are

entangled with power. Volunteering performances and organisational

discourses may reproduce (for example) Western-centric power

inequalities. Best placed to examine this is postcolonial theory,

which argues that Western colonial capacities 'are routinely reaffirmed

and reactivated in the colonial present' (Gregory, 2004:7). Postcolonial

theorists criticise representations used in third sector

promotional media (including Operation Christmas Child's, the

organisation considered in this research) which encourage

neocolonial imaginaries by using images of impoverished children

15

(figures 1-4) without socio-political context- victimising,

homogenising and silencing them (McEwan, 2007) and reproducing

Orientalist understandings of the global South as primitive and

backward (Said, 1978).

16

This knowledge is not innocent- because all knowledge 'presuppose[s]

and constitute[s] at the same time, power relations' (Foucault, 1977:27) which

have violent potential- and consequently isn't conducive to

encouraging Holdsworth and Quinn's (2011) 'deconstructive volunteering'.

However, postcolonial theorists also contend that distance is

relational and consequently negotiable (Raghuram et al. 2009) and

that every Westerner can and should listen to, learn from (Kapoor,

2004) and have Augé's (1998) sense for Others to address

inequalities. Investigating this will help answer the third

research question: do volunteers' practices (re)produce power

inequalities or can critical volunteering occur, in which

inequalities are negotiated? With answers to the other questions:

1. What 'ordinary ethics' (Barnett et al. 2005) and imaginaries are

brought to volunteering and how are these actualised spatio-

temporally?

2. What significance does the embodied nature of caring

practices bear in voluntarism and for volunteers themselves?

a greater understanding of volunteering as lived and experiential

might be developed.

17

Chapter 3 Methodology

3.1 Study context

This dissertation explores volunteering experiences in England

by studying the organisation Operation Christmas Child (hereafter

OCC). OCC is 'the world’s largest children’s Christmas appeal' (Samaritan's

Purse, 2011b) established in Wrexham, Wales in 1990 to alleviate

suffering in Romanian orphanages remnant of the Ceausescu regime.

Shoeboxes were packed with presents (like sweets, stickers,

gloves) and decoratively wrapped, then sent to Romanian orphans.

Its discourses presented shoeboxes as 'a tool for showing love' (OCC,

2006). The idea was embraced particularly by churches and schools;

OCC expanded considerably, sending shoeboxes to 'disadvantaged children'

(OCCa, 2011) in over 130 countries since 1993 (e.g. figure 5-7).

18

Now, OCC is part of the international organisation Samaritan's

Purse and with branches in Australia, New Zealand and Canada,

altogether over 86,000,000 shoeboxes have been sent since 1993

(OCCc, 2011) via this transnational care network. Principally

communicating via leaflets, posters and videos, by 2010 OCC also

had a website, social networking groups on Twitter and Facebook†

and 'Shoebox World', an online tool to fill shoeboxes vicariously.

Most volunteers unofficially (never formally registering with

OCC) fill shoeboxes and take them to 'drop-off points'. They may

also sell items for shoeboxes, like hats and mittens. Official† Twitter and Facebook are websites at the forefront of the recent explosion in

online social networking. On 04 January 2012 OCC had 8,121 and 685 followers of its international and British Twitter pages (respectively) and 26,109 Facebook fans.

19

volunteers (having undergone background checks) transport boxes to

OCC warehouses, checking (liquids, literature and war-related toys

are banned) and packaging them for shipping to distribution

partners overseas. Most volunteering is akin to transactional

giving (Davies, 2010)- without reciprocity, though infrequently

response letters are sent. Nevertheless, some volunteers pay to

assist shoebox distributions; according to desired involvement,

volunteers position themselves in performative 'niches' (McDonald

and Warburton, 2003). This is one reason why OCC was chosen for

this study; whilst comparable to other voluntary organisations in

mission, its structure (including unofficial and official

volunteering) enables diverse volunteering forms in formal and

informal contexts. This uniqueness doesn't, however, restrict this

study's applications since its focus is personal experiences of

volunteering, not OCC particularly. Other reasons for selecting

OCC included the international, distanced nature of giving and the

author's personal connections with OCC- contacts existed and its

structure and history were already familiar.

3.2 Methodology overview

This study's research, undertaken in summer 2011, used mixed

qualitative methods in a tripartite sampling of OCC's structure.

Such sampling enabled interaction with volunteers from multiple

performative niches. Firstly, semi-structured interviews with

volunteers were conducted largely in Wedmore, Somerset. Secondly,

observation and participation-based techniques were employed

20

during one week spent volunteering in an OCC warehouse in

Wiltshire. Thirdly, knitting and sewing were undertaken with five

volunteers (several hours spent with each). Throughout the

research, a written journal was kept to enable the recording and

consideration of personal thoughts and feelings and thus seek

'emotionally intelligent research' (Bennett, 2004). The following sections

elaborate on these methods, discussing positionality, power and

ethics.

3.3 Semi-structured interviews

Thirty semi-structured interviews were conducted with official

and unofficial volunteers- a manageable quantity considering time

constraints. Most were conducted in the author's home parish of

Wedmore, Somerset; recruiting volunteers largely from one area was

intended to enable nuanced understandings of potential research

themes, like community. Also interviewing warehouse volunteers,

included perspectives of those with roles like area coordinator

and warehouse manager- diversity enables access to varied

perspectives/experiences. Somerset volunteers were recruited via

the local magazine, church newsletters and word of mouth, then a

snowball sampling technique. Consequently, the sample wasn't

representative of OCC: children weren't interviewed, only one male

participated and approximately 85% of interviewees professed

themselves Christian. Nevertheless, neither a comparison of

different volunteers nor a representative sample were originally

sought. Instead an illustration was pursued, of volunteering as

21

lived and personal. One disadvantage was that interviewees

volunteering themselves were generally enthusiastic, potentially

positively biasing discussions. Their statuses as OCC's

representatives could also have caused tendencies towards such

positivity. To attempt to address this, interview questions were

carefully phrased to encourage critical reflection.

Interviews included several topics (see appendix) to uncover

accounts of why and how individuals volunteered and how practices

fitted into their lives. This enabled participants to respond to

(particularly the first two) research questions. Afterwards,

interview recordings were transcribed, then coded akin to Okley's

(1994) work, in which transcripts, notes and reviewed literature

were processed simultaneously and turbulently. Broad thematic

headings were provisionally constructed in a separate document,

then insights from notes and transcripts were compiled under them.

Further re-reading and data contemplation led to new and changed

interpretations.

During interviews, researcher-respondent power inequalities

were anticipated (e.g. from researcher university affiliations),

influencing responses. To balance these, participants themselves

were permitted to choose their interview location and the length

of their contributions†. Some broad questions were drafted for

conversation starters, but weren't rigidly imposed; participants'

responses naturally directed conversation, facilitating its flow

and a calm atmosphere. Interviews were digitally recorded (with

permission) though no accompanying notes were taken, instead being

written immediately afterwards to avoid undue formality unnerving

† Consequently, interviews were widely ranging in duration, from twenty minutesto over two hours! The average interview lasted thirty five minutes.

22

participants. Additionally, it enabled the researcher to listen

fully to responses and pose appropriate questions.

3.4 Participation-based research

The benefits of ethnography (sustained immersion in a social

system) to developing comprehensive, yet detailed, field

understandings are widely acknowledged (e.g. Fraenkel and Wallen,

2008). This inspired use of participation-based techniques to

answer (particularly) the second question of this research

(concerning embodied volunteering). Such methods involve working

alongside volunteers- a form of 'mobile ethnography' (Hein et al. 2008)-

though distinct from participatory action research where

respondents are proactively included to effect change that they

desire (Pain and Francis, 2003). Participation-based research

enables casual chats with volunteers which may facilitate 'chance

encounters, new discoveries and re-imaginings' (Davies and Dwyer, 2007)

impossible in interviews. 'Participation-while-interviewing' (Bærenholdt et

al. 2004) has also been said to level power differentials and help

respondents articulate their views honestly (Hitchings and Jones,

2004). Unfortunately, the acquisition of quotes was impeded as

recording conversations was impractical; all that remained was to

attempt to recall comments in my research journal. Nevertheless,

active research enables access to and (partial) sharing of

embodied volunteering experiences and performances, through which

more holistic understandings of the moral energies and ephemeral

affective atmospheres of volunteering can be developed. Although

23

this embodied knowledge evades representation, it was hoped that

it might help data interpretation. Volunteering undertaken

included knitting and working at an OCC warehouse.

3.4.1 Warehouse volunteering

With permission, one week was spent at an OCC warehouse in

Wiltshire, participating in routine voluntary activities. As a

purely volunteer-funded and operated warehouse processing c.30,000

boxes annually, it has a busy schedule of events, making it an

ideal place to experience volunteering. Outside of November,

warehouse volunteers fundraise and prepare for the checking of

boxes when 'fillers' are added to sparse boxes and exchanged for

unacceptable items. Many fillers are needed, requiring making or

sourcing, then storing according to age and gender suitability.

Additionally, containers of clothes and school equipment are

prepared to send with shoeboxes. During this research, all these

practices were participated in, also a coffee morning, the 'Knit 1

Purl 1 Club' (a fortnightly knitting afternoon) and a fundraising

quiz and picnic. Whilst some activities contrasted conventional

practices like knitting (their coffee breaks were frequent and

sometimes lengthy!) these were integral to volunteers' involvement

(and coffee breaks furthermore encouraged socialising that

facilitated researcher acceptance and more open conversations).

3.4.2 Knitting

Additional to volunteering in Wiltshire, sessions were

24

arranged at the homes of five post-retirement age women from

Somerset. Their volunteering constituted knitting or sewing items

for their own shoeboxes and for volunteer-run 'shoebox shops' in

churches, community centres and coffee mornings (figure 8-9) where

individuals can come and pay to fill shoeboxes immediately.

Materials were taken to each appointment and several hours were

spent joining each lady in her volunteering routine†. Participation

enabled observation of practices and performances to accompany

verbal accounts and also a visceral understanding of volunteering.

Knitting was subsequently also used to assist thought during data

processing. Throughout research, sensitivity to volunteers'

dispositions and characters was critical and required reflexivity

regarding positionality and ethics, considered in the following

sections.

3.5 Positionality

† Time was spent knitting a range of items which were used by the researcher tofill a shoebox personally at the end of the research period.

25

Since fieldwork 'is always contextual, relational, embodied and politicized'

(Sultana, 2007) continual reflexivity was imperative. Being a

young, white, British, middle class, female student positions one

within social power structures which could influence participants'

feelings and contributions. During research, certain researcher

positionality facets proved particularly influential: university

affiliation seemed to intimidate some respondents, reducing

conversation. Age differences also distanced elderly participants

from the researcher, reducing conversation, but also occasionally

reversing power relations, with the researcher being positioned as

a naïve youth to advise. Consequently, although eradicating

inequalities is impossible, working within frameworks to partially

reconcile differences and improve research quality was attempted.

Strategies adopted included avoiding mentioning institutional

affiliation or diverting conversation from its discussion. Another

was one of McDowell's (1998) strategies for interviewing elites:

researcher behaviour was modified after initial visual and verbal

assessments of participants to seek trusting relationships and 'elicit

as thoughtful... responses as possible' (ibid). The shared locality of the

researcher and many- consequently familiar- respondents proved

advantageous here, enabling quicker assessments and some trust

that facilitated more intimate interviews.

Regardless of efforts to negotiate positionality, findings

will be partial and situated owing to their influence by the

researcher's intersubjectivities (Mullings, 1999). Research

nevertheless has significance by:

26

“telling... stories that may otherwise not be told... and revealing broader patterns that

may or may not be stable over time and space” (Sultana, 2007).

Furthermore impartiality matters less than 'fidelity to an event' (Badiou,

2001:42)- 'being ethical and true to the relations and experiences... in the field'

(Sultana, ibid).

3.6 Ethics

Although commitment to ethical guidelines was necessary

throughout research, there was especial need to consider senior

volunteers. The elderly are vulnerable since ageing and memory

loss may lessen their ability 'to perceive information, and to make a rational

decision about participation' (Jokinen, et al. 2002). Consequently

researchers have a 'duty of care' to them (Hickey, 2011) actualised

here firstly, by seeking informed consent to avoid

misunderstandings; the study and intentions for data use were

explained to all participants by telephone/email beforehand and in

person immediately preceding research. Where necessary, it was

arranged for a relation of the volunteer to be present, for

support in case of memory loss. Secondly, confidentiality and

anonymity were assured. Thirdly, research was conducted in

participants' homes where it was 'easier for them to feel that they were an

authority on research topics' (Jokinen et al. 2002). Finally, topics were

explained clearly and sensitively to avoid psychological stress.

Overall however, commitment to established ethical codes wasn't

rigorous, since ethics must be lived in practical choices that

27

negotiate a tumultuous field. Successful research comes through

flexibility, integrity and judgement,

“not by following rules but by negotiating... social situations, sensitive as much as possible

to others’ needs and wishes” (Madjar and Higgins, 1996).

RESEARCH FINDINGS

28

Chapter 4 Actualising ordinary ethics in the

spaces of volunteering

4.1 Networks and connectivities

OCC is a transnational network of care through which thousands

of volunteers create and transfer gifts from across the UK to

disadvantaged children overseas. Officially, volunteering in OCC

is a device for serving these children, although it is also

assimilated and enmeshed within volunteers' personal lives,

transcending the organisational context and not existing

autonomously. Instead, volunteering was often brought into and

performed through practices of personal lives- shopping for

example was rarely a sanctified practice.

“[most] shopping I do on my own... while I'm out in the year, I don't think I'm going out to

shop for shoeboxes, while I'm in Tescos I think ooh they're on special offer I'll have them”

(Claire).

This proximity to daily practices blurred boundaries between

volunteering and wider life- its practices commingled with or were

co-constitutive of regular activities like lunch breaks, or

looking after family. The mundane spaces of these activities- like

car-boot sales and staffrooms- were drawn into OCC's network,

extending it and acquiring ethical significance. This networking

was dynamic, implicated spaces changed, some bearing significance

only momentarily. Sally's hallway for instance, became 'wonderful'

during October when storing her village's shoeboxes and Wiltshire

29

warehouse had regularly transformed displays and table

arrangements for different events. This exemplifies how

organisational networks are transient 'achievements' of volunteering

(Conradson, 2003). For volunteers themselves, the quotidian

situation of volunteering affected their comprehension of it;

approximately half didn't recognise themselves as volunteers. 'It's

just become part of my [life]... it doesn't feel like I'm doing anything extra' (Krissy).

For Claire's family, voluntarism was 'just something that's part of who we

are'. That volunteering wasn't recognised in ordinary spaces

suggests neglect of these spaces in understanding volunteering's

existence, achievements and significance.

OCC's network operated according to a distinctive moral

geography which volunteers helped sustain; it was deemed ethical

to give gifts to vulnerable children overseas, particularly in the

light of Western wealth and the expected charitable zeitgeist of

Christmas. Consequence of entanglements with personal

circumstances however, OCC meshed with other ethical networks,

like churches, whose moral geographies/imaginaries also then

became significant. Particularly important networks were McKie et

al.'s 'carescapes' (2002); volunteering often became a device for caring

for relatives or friends. Elara and Simone filled shoeboxes as an

activity with their grandchildren. Volunteering thus gained

meaning through connection with family carescapes and became a

deliberate activity. Other volunteers drew in different networks,

making other meanings; for Russell it enabled social bonding in

his church whilst Jane used it to educate her school pupils about

poverty. Volunteering didn't affect other networks

unidirectionally however, as the other ethical structures acted

30

reflexively upon it. In Wiltshire, Helen, Lizzie and Eilidh were

motivated by friendships they'd developed there, 'now we're just all like

sisters' (Helen). In this sense network interconnection sustained

voluntarism. However, connection could also be problematic. For

Helen the intersection of family and volunteering sometimes caused

aggravation- she'd been criticised with comments like 'you ever take

your bed round there?' Despite these potential difficulties, many

interconnections enhanced volunteering experiences.

4.2 The effects of ordinary ethics

This research affirmed Barnett et al.'s (2005) concept of

'ordinary ethics'; volunteers demonstrated ethics including those of

faith, generosity and care in the everyday. In volunteering,

certain of these ethics were 're-articulated'; Caz explained that

her box was 'just another present that I buy each Christmas for a family member or a

friend'- her ethic of care for others, shown by giving, was extended

to distant children. As Barnett et al. (2005) also contended, from

heterogeneous ordinary ethics heterogeneous practices emerge- Caz

demonstrated care by packing shoeboxes, Mary her faith by

knitting. The ordinarily ethical competencies motivating

volunteering weren't articulated exclusively however- other ethics

were practised in connected networks, decisions being potentially

influenced by several ethics enmeshing simultaneously. This was

shown when individuals who valued good financial stewardship

volunteered; their 'ethics of thrift' prompted efforts to pack

shoeboxes cheaply and influenced choices of recipient:

31

“I've just kind of done it on what was cheap, like find out what first few things I buy- oh

what age is that appropriate for? and then try and do it along that line” (Emily).

Often, there was no intention of miserly giving. Instead:

“I just want to get the best sort of quality goods, without going overboard on price wise so

I can fill two boxes” (Daniela).

Here, the combination of ethics sustained and enriched

volunteering, enabling care for multiple children. Simone acted

similarly, shopping cheaply at car-boot sales to fill six boxes.

At times however, ethical networks met unsuccessfully, some taking

precedence and restricting volunteering. Care for grandchildren

for instance reduced summer attendance at Wiltshire warehouse. In

Somerset some thrifty volunteers filled fewer boxes or stopped

altogether to avoid rising costs.

Additionally to influencing practices, the enmeshment of

ordinary ethics affected volunteering spaces, which acquired

multiple, overlapping functions oriented around both volunteers

and beneficiaries. At Wiltshire warehouse, co-ordinator Helen-

motivated by care for both her community and impoverished

children- tirelessly rearranged its furniture for different

events. Monthly coffee mornings raised funds for Samaritan's Purse

projects but other events unrelated to OCC benefited local people.

The warehouse space also served multiple functions for volunteers;

Helen decorated it to provide information about OCC and make an

exciting space where community members- for whom retirement had

32

brought feelings of redundancy and exclusion- could enjoy

volunteering and find 'acceptance', 'community' and 'purpose' (Helen)

re-using their skills from past employment. Helen's dedication

demonstrated a more deliberate, extraordinary commitment than most

volunteers, perhaps akin to practices of 'ethical citizenship' (Cloke et

al. 2007) emerging from, but moving beyond ordinary ethics.

Voluntarism's space-times are ethically complex, constructed

from re-articulated ordinary ethics and heterogeneous others from

their wider lives. In addition to considering policy-based

influences of voluntarism's spaces to understand their

organisation, it is necessary to consider the moral identities and

personal networks of volunteers (Smith et al. 2010). From these,

volunteering draws meaning and through them it is practised,

experienced and understood.

4.2.1 Faith

To inspect ordinary ethics more closely, ethics of faith

can be examined. The Christian faith, which approximately 80% of

volunteers brought to volunteering (or, to which volunteering was

taken), significantly influenced initial and continued engagements

with OCC and comprehension of voluntarism. This is not to say that

motivations like secular humanism weren't encountered nor that

such engagements with OCC weren't instructive, just that analysing

Christian faith enables an exploration of ethical network

intersections.

The meaning of faith to different Christians varies

considerably, although for all, to some extent, it is a moral lens

33

through which the world is interpreted. Through this lens,

particular Biblically principled ethics are adopted and many

Christians seeking deeper faith desire their habituation. For

some, as these moral sensibilities developed, so their willingness

to volunteer increased. Mary, for example developed a keen sense

of justice through her faith:

“to me it seems- it wouldn't have done 20 years ago maybe but it does now- it just seems

so grossly, not unfair... unjust somehow that we have so much... so anything we can

donate, do, give or whatever... let's do it” (Mary).

Faith increased her desire to volunteer, illustrating that to

fully understand volunteering, one must understand personal lives.

Whilst some Christians began supporting OCC for secular

reasons, most had their ethics of faith re-articulated by OCC's

campaigning devices. Several of OCC's videos, posters and leaflets

include Bible verses and phrases like 'God bless you' (Samaritan's

Purse, 2010) alongside requests for volunteers, calling upon

widespread Christian belief that faith is practical (James 2:17,

NIV) to gain attentions and mobilise volunteering responses

(Barnett and Land, 2007). Making volunteering a tool for

Christians expanded its function- Claire filled two shoeboxes

annually to represent and thank God for her two daughters. Others

used volunteering evangelically- to 'sow seeds' (Hannah), to 'get

somebody thinking of an alternative way of, living and, you know believing' (Daniela).

However, faith itself was not unaffected by volunteering. Time

spent filling shoeboxes transformed Keren's initial motivation

from obligation (as a Christian) to love. It prompted her prayer

34

for recipients and generally reaffirmed the value of prayer,

developing her faith.

The coincidence of faith and voluntarism also had collective

effects, partly because churches are popular vehicles for

encouraging and practising volunteering. Groups formed in several

churches to provide 'shoebox shops' for their congregations; these

fostered supportive friendships and a sense of Christian unity.

Each congregation's shoeboxes were also usually gathered in one

place before transportation; the sense of collective achievement

enhanced volunteering for Nikki and Krissy.

“it's always quite exciting, the days when the shoe boxes are being collected in... you get

this sense of achievement and feeling really proud that everyone's done something

together... it's not you independently... it's part of the church and part of fellowship”

(Krissy).

Volunteering in churches was sociable, illustrating the individual

and collective ethics of volunteering. Working at the warehouse

revealed this conviviality, which produced affective atmospheres;

at Wiltshire's Wednesday morning prayer meeting volunteers'

reverent prayers established an atmosphere. Although eluding

description using actor-network theory, this immaterial intensity

produced a sense of tranquillity amongst the volunteers. Sociality

challenges the prevailing view of volunteering as selfishly sought

by individuals pursuing 'moral selving' (Allahyari, 2000). Instead it

attests to the apprehension of volunteering through collective

social networks and the importance of relationship and

interdependence therein.

35

4.3 The perplexing nature of giving spaces

OCC is a double case of giving: volunteers give of themselves

and also ultimately produce gifts. Exploring this giving was meant

to enhance understanding about the complex ethical dimensions of

voluntarism- not to contribute to debates about

altruistic/egoistic motivations. This remit was partly developed

through conversations with volunteers about motivations and

practices. As expected, motivations ranged from compassion to

guilt, derived from encounters with poverty, actual or vicarious.

The quotidian sources of motivations made consequent giving

paradoxical. One paradox related to the relational ethics of

giving. When made charitably to the global South, postcolonial

theory contends that giving can be problematic if not founded upon

contextual understandings of and relationship with Others.

However, the situation of volunteering within personal lives meant

that sometimes ethical giving came from distance, anonymity and

uncertainty, not information and connection. For example, as a

child Julia was berated by her cousins for being doted upon at

Christmastime. She consequently felt guilty and feared the

emotional connections of giving- volunteering out of thankfulness

to God for her prosperity, which she considered morally good,

became problematic. OCC enabled her to anonymously send gifts and

'for the first time... [to be] just showing... that I cared' without guilt.

Consequently, she felt free to omit packing a Christmas card and

photo of herself and desired never to know where or to whom her

36

shoebox went. Julia illustrates how individual experiences

complicate the 'ethical' nature of giving; whilst critical

discourses like postcolonialism are useful ethical guides, they

smooth the tumultuous landscapes of voluntarism where ethics are

“'lived' in the exercise of practical judgements' (Madjar and Higgins, 1995).

Another paradox adds a new dimension to work on the

coexistence of egoistic and selfless motivations in volunteers; in

discussions of giving which arose whilst knitting, several

volunteers exhibited an ethic of care for themselves, revealing

the possibility that some self-interested acting might itself be

altruistic. The care shown was an ordinary concern for personal

health and wellbeing that might be called an 'ethic of catharsis'.

Several arthritic knitters for example, knitted 'to keep them [their

hands] going' (Anna). Anna also explained how by volunteering she

felt useful, which relieved her depression. At the warehouse,

volunteers communed and talked, a practise alleviating loneliness.

Care for oneself might conventionally be assumed selfish- defined

as:

“lacking consideration for other people; concerned chiefly with one's own personal profit

or pleasure” (OUP, 2011)

however catharsis wasn't selfishness in a self-indulgent sense-

caring about the self. Instead, it was a respectful caring for the

self. This ethic might be considered akin to 'alternative hedonism'

(Soper and Thomas, 2006), since both involve seeking self

satisfaction and can be motivated by disaffection with

neoliberalism's excesses. Catharsis however wasn't focussed on

37

substituting one set of pleasures for more satisfying ones, but on

meeting existing needs. This concept of ethical care for oneself

challenges the relational nature of Fisher and Tronto's (1990)

definition of care, where attentiveness and responsiveness are “to

needs of the Other”. The concept could perhaps be expanded to include

personal needs.

4.4 Summary

By considering OCC and volunteers' lives as networks, they are

shown as inseparably entangled, influencing and (sometimes)

vitalising one another. Within these networks, multiple ordinary

ethics intermingle, acting as threads weaving OCC into wider

contexts of giving and the fabric of volunteers' lives. This

produces complex, sometimes paradoxical spaces. Volunteering

consequently shouldn't be considered in isolation from volunteers'

lives because it occurs unpaid in disposable time, but instead co-

constructive of them and therefore of import underestimated in

previous readings of volunteering.

38

Chapter 5 Creating and connecting voluntarism's

spaces: the significance of embodiment

The central, malleable devices through which OCC volunteers

act ethically are shoeboxes, gift containers personalised through

creative volunteer performances (figure 10-11). Although according

to Davies et al.'s (2010) typology, the shoebox might be considered

39

an unreciprocated transactional gift, this chapter discusses how

volunteers desire and seek connection with recipients through

their giving.

5.1 Embodied practices of knitting

OCC's campaign revolves around packing shoeboxes, although

additional forms of care ripple out as this device becomes

embedded in individual lives. Some focussed their roles on

particular tasks; Jess ran a shoebox shop, whilst Frances

organised student volunteering at her school. Others with creative

abilities used OCC patterns to knit hats, mittens and puppets.

Knitting is an activity of turning wool into crafts. Simple

knitting is a fairly easy skill to acquire, though honing it can

take years. With practise, detailed knitting can be completed

whilst talking, reading or watching television, although periodic

40

quiet concentration is still required. Most knitters encountered

in this research had knitted throughout their lives and were

significantly skilled.

As a research technique, knitting proved rewarding, although

positionality attributes of age and educational status were

episodically problematic (pp19-20). Nevertheless, it is highly

recommended as a methodological tool for researchers concerned

with life histories, or gerontological accounts particularly;

mobile methodologies do create unique spaces enabling clearer

thinking and verbalisation of views (Hitchings and Jones, 2004)

because in knitting, the periodic necessity of concentration makes

silence socially acceptable and fosters a peaceful atmosphere,

with freedom to contribute or not to discussions. The contrast in

discussions before and during knitting with Kirstie was dramatic.

Before knitting, her comments were short and she seemed uneasy,

but once knitting, the atmosphere calmed and she chatted at

length, even sharing her emotions during volunteering; practise

opened windows onto deep conversations with participants.

Knitting is a craft occupying thoughts, hands and arms,

demonstrating the body's significance to volunteering argued by

Smith et al. (2010). Knitting was as they described 'embodied and

feelingful'- although forming only one experiential layer of place,

other elements of bodily condition (like carpal tunnel syndrome,

diabetes and hip arthoplasty) were also influential. Nevertheless

knitting was also an extraordinary hive of other meaningful

experiences; it was not, as initial inspection might conclude, a

banal habit practised to fill spare time. Firstly, knitting is an

historical and reflective experience. Often learned during

41

childhood from relatives, its practise rouses memories and life

histories. At the warehouse, sharing these memories drew

volunteers together. Individually, memories constituted identities

and life meaning. Shoebox beneficiaries also figured in

reflections- Clara's thoughts often drifted to her knitting

recipient and whether they'd like the item. She was consequently

pernickety about the shape, size and colour coordination of her

gloves, hat and puppet sets. These thoughts and concerns,

alongside volunteers' histories, caused individual approaches and

products unique in stitch, style and composition.

The addictive rhythms of knitting were also therapeutic,

leading to muscle relaxation and relief from arthritis. Linda and

Clara mentioned how knitting helped them think through and resolve

their problems. Finally, knitting was transformative. During

knitting, the atmosphere calmed and volunteers' dispositions

changed too; knitting stimulated reflection on the past, present

and future which didn't cause nostalgia, but appeared to help

volunteers to accept and mentally transcend situations, and plan

their negotiation†. They became more cheerful. Such assistance

mattered in both monumental and ordinary decisions and

consequently knitting- and perhaps volunteering generally- is only

deceptively ordinary and should be considered a critical structure

in volunteers' lives.

††The helpful influence of knitting upon volunteers' abilities to reflect and think prompted me to use knitting during the processing of the results of this study. It proved highly effective in this task and is recommended to other qualitative researchers, regardless of their interests!

42

5.2 Performances of care through shoeboxes

The practices of packing shoeboxes were certainly

performances- enactments embodying motivational ethics, personal

characteristics and emotions. As such, gifts enabled identity

enactments (Butler, 1997)- knitting for instance expressed

creativity and personal tastes. Additionally, boxes embodied love

and care for children, despite geographical distance. This

established connections that transcended the relational limitation

of shoeboxes being transactional gifts (Davies et al. 2010). Nikki

explained:

“you communicate with them [people] by other means at a distance, you know like emails

telephone... a shoebox is definitely one that is really a tangible way for children to

understand love... to have things... when you're little, it's things you can touch and hold”.

Performances raise questions about what ethical care is- most

volunteers never physically encountered recipients, lacked

knowledge of their contexts and didn't even know shoebox

destinations, despite this information being available. This may

strengthen Barnett and Land's argument (2007) that knowledge is

unnecessary for distanced caring, however postcolonial theorists

warn that without some knowledge, caring effectively is difficult.

Nevertheless, limited knowledge didn't prevent volunteers from

acting ethically by their own moral compasses. To them ethical

action was the 'actual giving of the gift to a child' (Elara) showing that they

'were loved and not forgotten' (SamaritansPurseTV, 2010); the connection

itself was prized over contextual knowledge and OCC was trusted to

43

specify unsuitable presents. Whether care without contextual

knowledge can be ethical raises philosophical questions suitable

for another study. Whatever the answers, relational giving through

shoeboxes was desirable and consequently, physically selecting

items and preparing boxes was considered of paramount importance

to volunteering; only Sara expressed interest in using Shoebox

World to send shoeboxes rather than pack personally. It was widely

believed that personal involvement- item creation and/or

selection, colour co-ordination and positioning- would show one's

personality and individual care:

“it's a really personal way to do something, you feel like you're putting a bit of yourself,

into the box... you feel like you're doing more somehow” (Krissy).

Even several housebound volunteers- whose friends filled their

shoeboxes- still inspected and packed boxes personally. The high

value of performance warns against further professionalising the

third sector, which prevents volunteers from demonstrating care

practically.

5.2.1 The affects of performance

Consequence of volunteering performances being embodied-

although exceeding and evading representation- OCC's spaces were

rich with affective atmospheres that formed additional layers of

volunteers' experiences. As Conradson (2003) explained, affects

are immaterial, fleeting sensations whose appreciation cannot be

obtained purely from an actor-network theory approach. This

44

immateriality however doesn't negate their importance- indeed,

affects were the motion behind all emotions emerging from and of

attachment to volunteering. The consequences of affect were

observable during interviews- many volunteers seemed excited,

their eyes glittered and they faltered in finding words (Hannah

and Krissy used sounds of wonder to describe their feelings).

Participatory techniques also helped reveal affect. Watching

promotional videos (containing facial shots of delighted

recipients) over lunch in Wiltshire moved some volunteers to tears

despite the spatial and temporal distance of recipients. Their

prayer meeting also had a lingering affective impact upon the

morning's work. Unfortunately, the critical affective time,

November when shoeboxes are collected and processed, couldn't be

experienced, though its aura endured- there was 'invisible dust still

singing, still dancing' (Thrift, 2000). Despite this limitation, other

affective moments were frequent- donations arriving daily in

Wiltshire always caused excited anticipation of the joy they might

bring. These sensational experiences had affective ethics; they

disposed individuals to seek ways to care for others, like

volunteering. They partly explain OCC's popularity.

5.3 At the nexus of ethics and embodiment: the haptic

geographies of voluntarism

Consequence of volunteering performances being embodied and

the limited visual connection with recipients, there was a will to

connect with recipients through the sense of touch. Whilst some

45

volunteers (Russell and Jane) didn’t believe haptic connection

possible without physical contact, all others did and consequently

volunteering practices and ethical performances need re-examining

from a haptic perspective.

In OCC, touch mattered in multiple ways. In Wiltshire, touch

through hugging, kissing and hand-shaking welcomed and included

volunteers. A central concern though was 'touching' the lives of

distant children through shoeboxes. This turned benevolence to

beneficence (Silk, 1998) and allowed recipients to

kinaesthetically understand the care with which boxes were sent

(Nikki, p32). Haptic encounters take many forms, including a

'caress' (Obrador-Pons, 2007) and a grasp. For Emma, it was 'the

personal touch' in shoebox packing that demonstrated an individual's

imprint and enabled connection despite distance, whilst Flossie

thought her volunteering showed love through 'reaching out'. For

Elara, touch was more literal. She sponsored a child and

corresponded with her- explaining how touching fingerprints on the

letters she'd received enabled indirect contact:

“I thought do you know in a way I've touched this child, she's, however many thousand

miles away but there is that connection, and you know that in the same way if you put a

card into a shoebox... or even when you've put the toys in you know somebody else's hands

are going to take them out, there's a connection however many thousands of miles”.

This highlights the importance of small bodily experiences to

participants, enabling connection across great distances. The

haptic is partly responsible for voluntarism's relational

intimacies and a source of the satisfaction volunteers reported.

46

Perceived connection also generally yielded senses of agency to

help others, not helplessness. Finally touch had ethical

potential; perceived connections promoted continued practices of

faith, caring and loving through volunteering. For Christians

particularly, touch was important- it enabled practises of faith

by providing an opportunity to embody Christ and demonstrate His

love/care. Jane described how her children felt whilst packing:

“they felt very strongly that they were, incarnating if you will, you know they were his

[Jesus'] hands and feet while they were packing the shoeboxes... [they] felt like they were

being Jesus to the children that they were buying these things for”.

Visual touching of gathered shoeboxes in churches also proved

significant to Christians, uniting them as a community (see p26).

5.3.1 (Dis)connection and responsibility

Whilst haptic connection proved central to volunteers'

experiences and there was often passionate enthusiasm for

practical care, the connection volunteers were willing or able to

make often had limits. Volunteering in OCC was frequently a

'reaching out' as Flossie described, but not the grasp of real

connection. Although some mediated this by assisting shoebox

distributions and Caz and Daniela additionally sponsored children

to achieve deeper relationships, for many volunteers, limited

connection was desirable. Julia explained that 'if there was a connection,

I'd feel like there was a responsibility there' and Nikki added:

47

“if you build up a relationship then, umm there's a vulnerability... it becomes a relationship

that may get tricky”.

Such reticence to deepen connections is problematic for meaningful

encounters with Others and paradoxical considering the touching

sought through volunteering. While for Julia (p27) connection

would have prevented ethical action, another possible reason for

disinclination is technological globalisation. By this,

information consumption has increased- including of media raising

poverty awareness and seeking charitable responses. Accompanying

this bombardment has been increasingly mediated and superficial

relationships (Rheingold, 2000) and senses of powerlessness to

effect societal change. Many volunteers responded by involving

themselves minimally in many campaigns, feeling obligated to

respond to as many as possible. Excessive involvement in one cause

was then perhaps feared as inhibitory of caring in other respects

(though to the detriment of establishing close relationships with

Others). Such distanced acting begs the question of whether

appropriate and effective care enriching both volunteer and

recipient is possible when weak social ties and shallow senses of

responsibility prevail.

5.4 Summary

Volunteering practices and performances are many and diverse,

each helping to produce OCC's spaces and volunteers' experiences

and to enact ethics; apprehending voluntarism would be impossible

48

without their consideration. Performances offer haptic connection