China-USA Business Review (ISSN 1537-1514) Vol.14, No.4, 2015

Chinese Business Review (ISSN 1537-1506) Vol.12, No.1, 2013

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of Chinese Business Review (ISSN 1537-1506) Vol.12, No.1, 2013

Chinese Business Review

Volume 12, Number 1, January 2013 (Serial Number 115)

David

David Publishing Company

www.davidpublishing.com

PublishingDavid

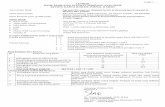

Publication Information: Chinese Business Review is published monthly in hard copy (ISSN 1537-1506) and online by David Publishing Company located at 9460 Telstar Ave Suite 5, EL Monte, CA 91731, USA.

Aims and Scope: Chinese Business Review, a monthly professional academic journal, covers all sorts of researches on Economic Research, Management Theory and Practice, Experts Forum, Macro or Micro Analysis, Economical Studies of Theory and Practice, Finance and Finance Management, Strategic Management, and Human Resource Management, and other latest findings and achievements from experts and scholars all over the world. Editorial Board Members: Moses N. Kiggundu (Canada) Yener COŞKUN (Turkey) Helena Maria Baptista Alves (Portugal) Marcello Signorelli (Italy) Doaa Mohamed Salman (Egypt) Amitabh Deo Kodwani (Poland) Lorena Blasco-Arcas (Spain) Yutaka Kurihara (Japan) Ahmad Zafarullah Abdul Jalil (Malaysia) Salvatore Romanazzi (Italy) Saeb Farhan Al Ganideh (Jordan) Tulus Tahi Hamonangan TAMBUNAN (Indonesia)

GEORGE ASPRIDIS (Greece) Agnieszka Izabela Baruk (Poland) Goran Kutnjak (Croatia) Elenica Pjero (Albania) Cafer TOPALOĞLU (Turkey) Indah Susilowati (Indonesia) LI Kui-Wai (Hong Kong) Mohamed Nabil MZOUGHI (Tunisia) Mary RÉDEI (Hungary) Shelly SHEN (China)

Manuscripts and correspondence are invited for publication. You can submit your papers via Web Submission, or E-mail to [email protected], [email protected]. Submission guidelines and Web Submission system are available at http://www.davidpublishing.org, http://www.davidpublishing.com. Editorial Office: 9460 Telstar Ave Suite 5, EL Monte, CA 91731, USA Tel: +1-323-984-7526, 323-410-1082 Fax: +1-323-984-7374, 323-908-0457 E-mail: [email protected]

Copyright©2013 by David Publishing Company and individual contributors. All rights reserved. David Publishing Company holds the exclusive copyright of all the contents of this journal. In accordance with the international convention, no part of this journal may be reproduced or transmitted by any media or publishing organs (including various websites) without the written permission of the copyright holder. Otherwise, any conduct would be considered as the violation of the copyright. The contents of this journal are available for any citation, however, all the citations should be clearly indicated with the title of this journal, serial number and the name of the author.

Abstracted / Indexed in: Database of EBSCO, Massachusetts, USA Ulrich’s Periodicals Directory ProQuest/CSA Social Science Collection, Public Affairs Information Service (PAIS), USA Norwegian Social Science Data Services (NSD), Database for Statistics on Higher Education (DBH), Norway Index Copernicus, Poland Summon Serials Solutions

Chinese Database of CEPS, Airiti Inc. & OCLC Chinese Scientific Journals Database, VIP Corporation, Chongqing, P. R. China

Subscription Information: Print $520 Online $360 Print and Online $680 David Publishing Company 9460 Telstar Ave Suite 5, EL Monte, CA 91731, USA Tel: +1-323-984-7526, 323-410-1082 Fax: +1-323-984-7374, 323-908-0457 E-mail: [email protected]

David Publishing Company

www.davidpublishing.com

DAVID PUBLISHING

D

Chinese Business Review

Volume 12, Number 1, January 2013 (Serial Number 115)

Contents Economics

Typology and Dynamics of Financial-Industrial Groups Operating in the Czech Republic and Slovakia 1

Danes BRZICA

Migration in the Middle Asia and Its Effects on the Labor Market 14 Füsun ÇELEBİ, Atakan DURMAZ

Acceleration Factors in the Improvement of Public Welfare Sangiran 24 Mugi Raharjo, I Gusti Putu Diva Awatara, Harmadi, Wahyu Agung Setyo New Keynesian Model and Inflation Prediction 34 Yutaka Kurihara

Chinese Patent—A Tentative Explanation of Various Strategies of Patenting 41 Dou Henri, Dou Jean-Marie Jr

Management

Entrepreneurship and Growth in Emerging Mini-dragon Economies: A South-East Asia Perspective 48

Alex Maritz, Viet Le, Simon Masli, Anton de Waal, Bert Verhoeven, Shieh, Chich Jen

Analysis of Managing Creativity for Entrepreneurs 62 Ati Cahayani

Application of Recent Technologies in the Concept of Modern Business 70 Danica Tadic

Chinese Business Review, ISSN 1537-1506 January 2013, Vol. 12, No. 1, 1-13

Typology and Dynamics of Financial-Industrial Groups

Operating in the Czech Republic and Slovakia*

Danes BRZICA

Slovak Academy of Sciences, Bratislava, Slovak Republic

The contribution of this paper is threefold. Firstly, it develops a typology of corporate group development in terms

of the pattern of corporate group formation in the Czech Republic and Slovakia. It identifies briefly three important

types of corporate groups—industrial groups (type I groups), pyramid-like (type II) groups, and financial (type III

or FIGs) groups. Using original typology for corporate groups, the paper examines development trajectory of some

of the biggest FIGs and shows what effects their existence have in the two economies. Finally, some lessons

resulting from this corporate group-related type of ownership concentration for other pre-transitive countries are

mentioned.

Keywords: financial-industrial groups, The Czech Republic, Slovakia, restructuring, corporate governance

Introduction

Transformation towards market economy has been completed across Central and Eastern European

countries (CEECs). Since its start in early 1990s, this process has represented numerous reform processes, radical

shifts in institutional settings and many other aspects affecting business actors as well as citizens. Despite the

specter of changes, the most visible aspect of reforms was privatization process. It is not our aim here to review

all main features of the process but rather to look at how specific institutional setting, regulation, and policy steps

affected the emergence and development of financial-industrial groups (type III groups or FIGs) in the Czech

Republic (CR) and Slovak Republic (SR). To demonstrate magnitude of FIGs power, one good example is PPF

group from the Czech Republic majority-owned by Kellner. Mr. Kellner’s position was among the top 100 richest

men of the world as of 2010. Other groups, although smaller, are also important players on the domestic and

(Central) European markets.

The contribution of our paper is threefold. Firstly, it develops a typology of corporate group development in

terms of the pattern of corporate group formation in the Czech Republic and Slovakia. Briefly, it identifies three

important types of corporate groups in these countries: these being industrial groups, pyramid-like groups, and

financial groups. Our research tries to show how group-related process of ownership concentration has developed

* Acknowledgment: This paper was published with the support of grant VEGA number 2/0080/12. The author would like to thank for the comments on an earlier versions of this article to participants at conferences in Stockholm, Sydney and Seoul. The author also wants to thank for useful comments to M. Rafferty from The University of Sydney Business School.

Danes BRZICA, Ing., Ph.D., Institute of Economic Research, Slovak Academy of Sciences. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Danes BRZICA, Institute of Economic Research, Slovak

Academy of Sciences, Sancova 56, 811 05 Bratislava, Slovak Republic. E-mail: [email protected].

DAVID PUBLISHING

D

TYPOLOGY AND DYNAMICS OF FINANCIAL-INDUSTRIAL GROUPS 2

since the beginning of transition. In the early transition process, industrial groups emerged as significant ways of

overcoming the weaknesses in financial markets and property rights confronting industrial firms, themselves

facing significant restructuring pressures. Later groups (pyramid-like) emerged out of the process of collecting

funds from the public, especially in Slovakia, on the promise of very high returns from stock trading and

investment. However, these groups were quite unstable and unprofitable forms of investment and losses to small

lenders/investors were common. Indeed, as with pyramid type schemes elsewhere, many pyramid-like groups

were characterized by flagrant theft and corruption, and their activities quickly came to be considered to be risky

or illegal. Not surprisingly then, their history was to paraphrase Hobbes, nasty brutish and short. This paper aims

also to analyze emergence and developmental trajectories of FIGs in the two countries, and finally to formulate

some general policy lessons from transformation process related to FISGs. The structure of the paper corresponds

to the above three areas.

Theoretical Issues Related to Groups and Basic Typology

The theory of firm has a well-established literature covering several aspects of firm structure and

performance. Some of the traditional works on firm structure and performance include Demsetz (1983), March

and Simon (1958), and many others. However, some new areas of research have been introduced recently to the

traditional areas. Among these are, e.g., issues of ownership concentration and corporate governance. Tirole

(1991) represents one important work that explores the newer areas in the context of developments in CEECs.

The standard textbook account of the firm tells us that increased size often brings greater efficiency, but that as a

firm grows beyond a certain size it may in fact become absolutely less efficient. This size/performance paradigm

has been a centerpiece of research on the firm for decades. One reason provided by the literature on optimal

size/performance is that as a corporate group grows it eventually becomes more difficult to organize and manage.

Thus, some diseconomies may begin to arise because of the firm exceeding optimal size. Problems with the firm

size often relate to difficulties in coordination and control of group activities.

Most existing research on the development of the corporate sector in the Czech Republic and Slovakia has to

date focused on the mechanisms and effects of voucher privatization. Some have taken this analysis further and

attempted to estimate also the impact of investment funds on the process. Notable here is the work of Ellerman

(1998), Mertlik (1997), and more broadly Simoneti, Estrin, and Boehm (1999), and Olsson (1999). In general,

these studies tell a rather gloomy story about the impact of these methods of privatization and financial structure

on market and corporate development. The privatization process helped to introduce companies and markets in a

formal sense, but as such could not provide mechanisms to ensure that they operated in ways that anywhere near

approached those of developed market economies. Privatization by vouchers generated an initially dispersed

ownership structure, but was rapidly overwhelmed by developments that have led to highly concentrated

ownership forms (e.g., Olsson and Brzica, 2001). In earlier research by the author, it was established if it was

possible to identify the emergence of several different types of corporate group structures.

Research into ownership concentration has typically been made in terms of industry concentration ratios,

average corporate size or other such indicators. These indicators provide a very good standardized snapshot of

industry or firm structure and offer the possibility of using inter-industry or cross-country comparisons of various

types. However, it is difficult to use such data for tracing the dynamics of industrial concentration in a country

TYPOLOGY AND DYNAMICS OF FINANCIAL-INDUSTRIAL GROUPS 3

undergoing rapid change. In the case of the countries under study, where rapid changes in both the scale and

nature of concentration has been a central feature, such static measures may not therefore be especially useful. In

such cases, it may be better to use case studies instead. Another reason for adopting this research strategy is that

data limitations are themselves quite constraining. We simply do not have enough data at either industry or

individual company level due to privacy restrictions imposed on statistical agencies, except for the limited data

disclosed through the stock market. This paper therefore employs selected sample analysis as a way of attempting

to improve our understanding of corporate ownership structures in the Czech and Slovak Republics. Before

moving to that analysis, the paper attempts to specify the structural features of type III firms in more detail.

Uncertainty is considered an important factor contributing to the emergence of business groups. Along with

incomplete information and transaction costs, different degrees of uncertainty can lead to higher or lower degrees

of group concentration. Dynamics and flexibility go hand in hand with pragmatism leading to what has been

known as co-competition (competition through cooperation). It is therefore no surprise that the type III groups

make no ideological, political or other selection in finding their strategic/tactical partners or in following their

strategic goals. In such cases, this sort of opportunism is not to be taken as an absence of strategy. Instead, in a

rapidly changing corporate and institutional environment, it may be a logical and profitable strategic orientation.

To be successful in such activities, each group usually has to have its own legal, consulting, and brokering agency

or at least have good access to some good independent ones. In addition, previously purely industrial groups have

typically transformed into financial-industrial groups by acquiring important financial firms (e.g., Komarek’s

acquisition of Atlantik finanční trhy).

Theories of economic concentration are frequently misinterpreted. The evolution of groups in transition

economies, often neglected in studies1 of transition reforms, can shed light on concentration patterns and

determinants. We cannot overemphasize the importance of these groups for understanding the influence and

patterns of foreign investment and their role in economic development. The ability to capture and control large

equity stakes of whatever sort are surely results of tough inter- and intra-national competition. Group

interdependence (Williamson, 1975) is the most serious of the alleged dangers of group formation. The process is

not unlike that of a traditional oligopoly. Competition is restrained out of the mutually recognized dependence.

This may take form of less aggressive competition in markets, where interfaces exist, or a reduction in potential

competition in markets where entry might otherwise occur.

In order to make the analysis more understandable, the paper introduces a brief typology of corporate groups,

which have appeared in the two economies since 1990s. Table 1 provides a simplified typology that characterizes

three different sets of corporate groups. The taxonomy used to differentiate the three main group types identified

is based on multiple criteria and not purely on strict quantitative parameters. Importantly, criteria cover different

phases of corporate development. This means that similarities or even the same characteristics exist across some

groups. Group types I, II, and III are therefore also expressions of a time horizon of corporate group development,

starting with type I to the present type III. Table 3 in the next section then divides the main home-established

corporate groups into the following three categories: (1) industrial groups (also called type I groups); (2)

pyramid-like groups (type II groups); and (3) financial groups (type III groups or FIGs). If taken chronologically, 1 However, there are some important studies, which appeared in early 1990s (Stark, 1996, on recombinant property and group structures).

TYPOLOGY AND DYNAMICS OF FINANCIAL-INDUSTRIAL GROUPS 4

however, one would have to make some other structuring or typology, because today one can find both type I and

III groups together (with some rather relics of type II groups as well) on the markets.

It is possible find some type I groups existing today, but often in a completely different form (often not so

fragmented as in the earlier phase of transformation) and with different owners (often foreign ones). A good

example of this is former VSZ Kosice. Originally privatized by means of a sort of management buyout, the firm

was later taken-over by US Steel (Olsson, 1999).

Table 1

Typology of FIGs

Group types:

Group type I—Industrial groups (traditional holding companies operating in one or more industries/segments).

Group type II—Pyramid-like groups (predominantly speculative type of firms, which has gradually grown to become

local/regional imperia, typically they collapsed several years after their emergence).

Group type III—Financial-industrial groups (FIGs) (represent powerful and well-managed firms with huge capital—in bn of

EUR—often highly diversified).

Note. Source: The author’s own.

Our paper shows that financial groups (type III groups) are now becoming a powerful force in the corporate

sector in both countries and create different ownership/industrial structures. Furthermore, they have not (yet) been

affected by large (especially foreign) investors. The Správa prvního privatizačního fondu (that became the PPF

Group) is seen here as the main representative of the type III groups. In 1991, PPF had already established an office

aimed at the administration of a prepared investment fund. Later, Prvni privatizacni fond, a privatization fund

representing the core of the PPF, was established, and by 1994, PPF had collected approximately five billion CZK

in assets. Having laid out the general characteristics of type III firms, the case study charts the development of PPF

as a way of illustrating these characteristics. It shows how this type of corporate group has become important.

Existing diseconomies caused by the excess size of a group can, however, be offset by other effects. Under

relatively weaker corporate governance systems and poorer property rights protection in transitional economies, it

may be profitable to organize information and resource transfers through a larger corporate group, despite any

possible diseconomies. Indeed, one of the most important explanations for the development of high levels of

ownership concentration in Eastern Europe (of which corporate groups are one expression) is that concentrations of

ownership and complex control vehicles are response to inadequate protection of investors (La Porta et al., 1997).

Table 1 shows the range of analytical factors that provide a context for the development of ownership

concentration and corporate groups. The table serves to help explain the development of type III corporate groups,

but can be used to help explain the development of all three types of corporate groups. It shows that the factors

affecting group development can be understood in terms of two broad dimensions: the institutional and the

corporate framework. Further, within the institutional framework, both the environment confronting shareholders

and users of capital markets will affect the way that corporate groups develop. Moreover, within the corporate

framework, the independence and efficiency of corporate regulatory system, as well as the transparency and

responsibility of the corporate governance system will affect corporate group development. Finally, strategic and

competitive power factors within the corporate framework will affect the development of corporate groups.

TYPOLOGY AND DYNAMICS OF FINANCIAL-INDUSTRIAL GROUPS 5

In explaining the development of type III groups, this paper suggests that strategic factors (scope of

activities covered—SCOAC-C and high profit activity share on total activities HIAC-C) and competitive power

(POW-C) issues, together with ownership related issues (OW-I and INV-I) have been particularly important. C

and I, respectively, in abbreviations means corporate or institutional framework element. Given their importance

for the analysis of the ownership structure within type III groups and corporate governance issues, the paper also

mentions rate of equality among shareholders (SHE-C). The paper suggests that for further growth of the type III

groups, a more balanced dealing with different stakeholders (and especially particular shareholder groups) will

now become more critical. After all, it is widely accepted that it has been this factor, which has been a source of

many problems in corporate development in most transition economies. This structural weakness and the absence

of properly specified legal protections have substantially marked the development of capital markets in the Czech

Republic and Slovakia. These weaknesses have had, however, an uneven impact. It provided advantages for the

some groups of shareholders, especially to large (majority-insider) shareholders.

Table 2 provides some specification of the analytical context applied to the two basic corporate governance

models—Anglo-Saxon and continental. The structure of corporate governance has certainly exerted a substantial

influence over the process of ownership concentration and the emergence of all three types of groups.

Irrespective of the specific type of privatization employed, certain forms of legal arrangements along with a

traditional aversion to meet ethical standards vis-à-vis the state and business partners, there would not have been

probably such processes of ownership concentration, which we have seen since 1990s. On the other hand, the

historical fact is that everywhere around the globe a concentration of property in reform period had been

aggressive and massive in both scale and scope.

Table 2

Specification of the Analytical Context: Two Basic Models

Model OW-I ownership

INV-I investment

STDEV-I stock market development

TAK-I rate of takeover activity

BO-C Board INC-C Incentives

DIS-C Disclosure

SHE-C shareholder protection

A Dispersed institutional investors

High High Majority of non-executive members

Widely-set stimuli

High High

B Concentrated families, banks, public sector

low (especiallyfor the new issues)

Limited Bodies composed from insiders

Stimuli related to main shareholders

Limited

Weak protection of minority shareholders

Notes. Model A = Anglo-Saxon model; Model B = continental model; Source: The author’s own.

Table 4 does not cover all industrial groups existing in the Czech and Slovak republics. Several other large

actors operate in coal mining (Kolacek group, Czech Coal), agriculture and food processing (Agropol Group),

petrol, travel, and tourism (Unimex group) and real estate. Other groups are established or controlled by foreign

companies, e.g., Siemens group in Slovakia or ABB in the Czech Republic.

Emergence and Developmental Strategies of FIGs

Given the fact that voucher privatization was designed and for the first time used on a wide-scale basis in the

Czech Republic, it was natural that this model had been used also in some other countries, which had copied this

model with some modifications later on (e.g., in Bulgaria or Russia). Several authors have written on the topic of

TYPOLOGY AND DYNAMICS OF FINANCIAL-INDUSTRIAL GROUPS 6

voucher privatization specifically (Claessens, Djankov, & Pohl, 1996) or on privatization in the Czech Republic

in general (Coffee, 1996). Studies of ownership concentration in Western Europe and CEECs (Olsson & Brzica,

2001; Olsson & Alasheyeva, 2000) confirm that for various reason the concentration of listed companies was

quite high in late 1990s.

Development of corporate groups is the result of ongoing ownership concentration in the Czech and Slovak

economies and can be characterized by several periods. Several types of financial and industrial groups have

appeared since 1990s, but now it is evident that only some of them have survived and even smaller part of them have

become FIGs. In this chapter, five subchapters cover main aspects of FIGs’ emergence and developmental strategies

Type III Groups: Concentration, Conflict, and Cooperation

The type III groups compete intensively within the Czech and Slovak republics. For them, the transfer of

remaining state stakes in companies or bad debts claims has been a central way they have been able to expand at

such a rapid pace. Table 3 provides a more detailed picture of the corporate groups in the two countries selected.

Table 3

Typology With Some Representatives for Each Type Group (Examples)

Group Types:

Type I—Industrial groups

Chemapol group (Czech Republic)

Skoda Plzen group (Czech Republic)

VSZ Kosice group (Slovakia)

HTC holding (Slovakia)

IPB Group (financial group with stakes in industrial firms) (Czech Republic)

Skoda Plzen Group (Czech Republic)

Majsky group (Slovakia)

Agrofert Holding (Czech Republic)

Type II—Pyramid-like groups

BMG Invest CR (Czech Republic)

BMG Invest (Slovakia)

Horizont Slovakia (Slovakia)

Drukos (Slovakia)

AGW (Slovakia)

Type III—Financial-industrial super groups (FISGs)

PPF Group (Czech Republic)

K&K Capital Group (Komarek Group) (Czech Republic)

J&T (Czech Republic & Slovakia)

Penta Group (Slovakia)

Istrokapital (Slovakia)

CPI (Czech Republic)

Note. For the cases of Chemapol group, VSZ group, and Skoda Plzen group see Brzica (2001). Source: The author’s own.

TYPOLOGY AND DYNAMICS OF FINANCIAL-INDUSTRIAL GROUPS 7

Whereas some groups have remained concentrated purely on their home market, others have expanded to

the East (PPF), to the West (HTC) or in both directions (Komarek group—to the former Soviet territory and

Norway). There are three possible reasons for doing this: (1) to compete later on the EU market; (2) to counter

balance local or national competitors; and (3) to expand eastward later on. Table 4 presents a basic description of

the type III groups’ representatives.

Table 4

Type III Actors—Basic Description

(1) Penta Group—Penta is one of the most important financial groups. It operates in both Slovakia and the Czech Republic.

(2) HTC Holding—It is the Slovak financial group controlling the Czech biggest tractor producer Zetor Brno. HTC consists of

13 companies. As of December 31, 2002, it reported sales of 19.8 bn SKK and employed 8,000 people. Zetor reported in 2002

profit 3.436 bn CZK compared with 2001’s loss of 631 mn CZK.

(3) Istrokapital—Istrokapital has been created by merger of four investment funds from the first wave of voucher privatization.

Originally the funds had been under management of Slovenska sporitelna, a.s., Bratislava (Slovak insurance company), which

sold its shares.

(4) PPF group—PPF is a private international financial group based in the Netherlands. Founded in 1991, currently this group

focuses on consumer finance, insurance, banking, and real estate business. It operates in the Czech Republic, Slovakia,

Belarus, China, Cyprus, Kazakhstan, Russia, Ukraine, and Vietnam. The group consisted of specialized companies (10);

financial institutions (15); and a media company (1) in late 1990s. It is majority-owned by Petr Kellner (who controls 94%)

PPF belongs to the most important financial groups in the Czech Republic. It controls property in volume of 359 bn CZK and

controls 317 companies (2011 data).

(5) K&K Capital group (K. Komarek group)—The group is active in petrol business and industrial production. Komarek Group

also acquired Atlantik financni trhy (AFT) in late 1990s making thus the group also rooted in financial operations. Later on,

AFT was sold in 2010 to J&T. KKCG recently divided into two separate holdings. The group controlled 42 bn CZK assets in

2007.

(6) Agrofert Holding—Agrofert Holding represents a holding in agricultural business. Agrofert is a type I group survivor so far

without any financial branch. This case shows that some of the former type I groups persist on the scene.

(7) Czech Coal—the group controlled by P. Tykac is one of the biggest owners of Czech coalmines.

(8) J&T—important group focused on energy, banking and finance, real estate, media.

(9) Karbon Invest—controlled by Z. Bakala. Bakala originally focused on finance recently concentrates on coal business.

Currently Bakala owns NWR (New World Resources) company (coal business) and via his investment company RPG he owns,

e.g., 44 thousand flats.

(10) EC Group—controlled by J. Dienstl. Received state claims from Czech consolidation agency in volume of 39 bn CZK in

2003.

Note. Source: The author’s own.

So far, only limited data are available for the analysis of these groups, and this gives researchers only a

limited set of options. Hence, we have chosen to use anecdotal evidence in combination with the presentation of

selected sample of the main players. In one older survey of investment companies and investment funds (Brzica,

TYPOLOGY AND DYNAMICS OF FINANCIAL-INDUSTRIAL GROUPS 8

1996), several of the biggest fund managers expressed then their willingness to become active administrators of

firms in their portfolio. Legal barriers, however, have changed their possibilities for a while but some of their

dreams have continued throughout the whole 1990s.

What has been typical for all main FIGs since their emergence in 1990s is their bi-polar nature of their

business. As most of FIGs are large groups within their home countries they, as a result, both compete and

cooperate among themselves. The reason is simple, in public tenders many of them are interested to participate

and hence they compete there or, alternatively, they form consortia in which they cooperate (see Table 5 for

illustration).

Table 5

Competition Over Stakes—Some Examples

Firm Industry Value Bidders/competitors

Unipetrol2 petrol 15 bn CZK B, other firms*

Severoceske doly coalmining millions of CZK J, P, other firms*

TV NOVA TV broadcasting billions of CZK PP

State claims various industries billions of CZK PP**, J**, P, EC, other firms*

Fischer group travel agencies millions of CZK P, K, J

Cesky Telecom3 telecommunications 50 bn CZK PP

Sazka lottery billions of CZK J, P, CPI, other firms

Notes. PP = PPF; B = Babis group (Agrofert); P = Penta group; J = J&T group; I = Istrocapital; K = Komarek group; EC = EC group; * There are also some other competitors but they do not represent the groups studied here; **Penta is together with J&T Finance one of the biggest Slovak type III groups, which business focus is especially on trades with bad debts. Source: The author’s own.

Ownership and Control Dynamics of Type III Groups

What makes the difference between the three categories of groups mentioned earlier important for the

changing corporate landscape (and therefore for researchers) are differences in the dynamics and strategic focus

as well as the composition of their activities between the different types of group structures. Whereas the type I

and II groups could be characterized as having quite stable strategic focus, especially on acquiring stakes in

industrial companies (in the case of the type I groups) or collecting money from investors (in the case of the type

II groups), the type III groups are more dynamic in pursuing their strategic goals. Demsetz and Lehn (1985)

postulate that owner control should be more valuable in firms where rapid, uncertain changes in the operating

environment make it difficult to evaluate the effort of management. This is indeed the characteristic feature of the

present business environment in certain segments of the Czech and Slovak industries where further important

privatizations are to be expected.

Having the PPF group in the sample of type III groups, it is easy to show that the dynamics inherent to the

2 Participation in the privatization of Unipetrol announced then the Hungarian petrol and gas company MOL; the Polish PKN Orlen (in consortium with Agrofert); the Russian company Yukos and TNK-BP; ConocoPhilips and Agip. Both Agip and ConocoPhillips had already stakes in Unipetrol and planned to increase their stakes in the company. 3 The consortium Tel Source, representing KPN (The Netherlands) and Swisscom (Switzerland), had decided to sell 27 percent of Cesky Telekom shares. The PPF group, as financial investor, searched for new investment opportunities. Cesky Telekom had been evaluated from this perspective but given the circumstances the purchase of its shares was not considered attractive enough for the PPF.

TYPOLOGY AND DYNAMICS OF FINANCIAL-INDUSTRIAL GROUPS 9

group has helped it to survive and avoid the destiny of other type I groups.4 Internal efficiency of the type III

groups is probably higher than that for the type I and definitely higher than for the type II, because responsiveness

to change is integral to their strategic and structural orientation. Initial ownership dynamics of the type III groups

could have been hampered due to several factors. Among them especially important are: (1) an increasing

competition from abroad in particular segments nowadays controlled by the groups; (2) a global pressure to

concentrate on core technologies; and (3) problems with management and control of complex business structures

in a less developed institutional environment.

Compared with type I and II groups, which had focused on mainly industrial capital and real estate (type I)

or money capital (type II), the type III groups are open to every opportunity to make profit. For this reason, they

have created efficient structures to identify profitable opportunities, provide legal advice on all operations to

avoid possible misconducts and potential suits, and to mobilize financial resources within the group to take

advantage of the identified opportunities. They also organize restructuring, managing/maintaining, consulting or

selling newly acquired assets. This is being made on such a wide-scale level that it can be considered as a

completely new phenomenon despite some exceptions that existed within types I and II groups.

With the concentration process having intensified across many sectors of the Czech and Slovak economies,

large parts of the economy are now controlled either by private groups/companies (or remain in state ownership).

The “winner takes all” principle of current privatization and corporate takeover activity is forcing all the main

players to be active in fights for receiving controlling stakes in different important companies be they in

telecommunications (Telecom), petrol (Unipetrol), banking (Postovni banka) and others. Table 5 provides some

examples of which groups have been competing over which stakes. From the privatization of Unipetrol, the

Czech Republic expected to receive revenues up to 15 bn CZK. As seen from the announced planned sales, a bid

for these stakes required/s substantial capital available. Several groups from our sample confirmed that they have

enough capital sources to be ready to use for such purposes.

We have observed so far that the Czech and Slovak corporate sector concentration for publicly listed

companies is substantial. The group-related process of ownership concentration is permanent throughout the

transition period in both countries as the groups analyzed collect still higher stakes in some important companies

as shown by the cases of PPF or Penta group. In addition, there are several indicators suggesting that this process

will continue. The forms and modes of concentration used by FIGs have been changing over time. It is evident

that some practices and strategies: (1) do not work efficiently; (2) are no longer available (e.g., cheap bank

credits); or (3) are no longer possible (due to higher competition on the market, new legislation etc.). The groups

as intermediaries can, in some cases, “maintain” originally highly concentrated ownership structure of some

former state companies unchanged, because, through bids, they have access to bulk of shares in these companies.

The Cesky Telecom case is one such example of this phenomenon. The dynamics of different types of groups

have widened substantially in terms of durability (persistence), complexity and scope or profitability. Nowadays

they also more efficiently use an opportunity to be incorporated abroad.5

As regards ownership structure, in many cases FIGs are either family-owned (KKCG, EC group),

4 Sometime the IPB case is mentioned in this regard because of some similarities between IPB and PPF structures. 5 Being dynamic and powerful also means that a group should pay substantial amount of taxes. Therefore, the mother company of the whole group, Penta Holding Ltd., is for the tax purposes registered in Cyprus.

TYPOLOGY AND DYNAMICS OF FINANCIAL-INDUSTRIAL GROUPS 10

individually owned (PPF), or owned by small number of individual majority owners (Penta group, J&T).

Restructuring Dynamics of Type III Groups

The emergence of type III groups, together with a new state policy of selling claims of Czech consolidation

agency (a state agency responsible for dealing with claims of state), have generated higher dynamics to the whole

process of restructuring. Not successful initial bank and type I group-lead restructuring have been gradually

substituted by more successful type III groups-lead restructuring. Whereas both the Czech and Slovak banks had

not been successful in solving the situation with their bad debts and claims, the type III groups had been very

dynamic and successful here. Usual time-period of solving such a case was less than one year,6 any operation

lasting more than one year was considered as a failure and such claims were written-off.

Despite the literature on the relation between corporate concentration and restructuring is not well

developed in transition economies, the results from developed countries have shown substantial interrelatedness

between the two aspects. Hence, one has a good reason to believe that making the industrial structure more

concentrated can lead in turn to further restructuring. Restructuring activities are considered here in a wider sense.

They include not only corporate/industrial restructuring processes but also innovations generated by the type III

groups leading to changes in institutional environment and organization setting on the national level. So far, there

have been several such changes made also by the type I and II groups. In the case of type III groups, one change

affected completely corporate sector. It was the initiative of the two companies cooperating on the Czech and

Slovak markets (J&T Global, a member of J&T group and MEI—Middle Europe Investment from the

Netherlands) to trade IPOs of shares related to business in real estates in the Czech Republic and Slovakia. The

two firms have created Middle Europe Real Estate (MERE), a close-end fund with assets value of 100 mn EUR,

where J&T Global and MEI have become joint fund administrators.

In general, restructuring of an economy in transition requires a committed government providing consistent

and widely supported economic policy as well as some business actors capable to initiate needed changes.

Strategic investors from the voucher privatization—some strategically oriented investment companies and

investment funds7; industrial groups of the type I and some individually owned “family imperia”8—could not

have obtained enough power to contribute to substantial concentration of ownership in medium-term horizon.

Many of them have either been transferred into portfolio players, have collapsed or been marginalized by (often

foreign) competitors. In the latter two groups (collapsed and marginalized firms) one can find Chemapol group or

Skoda Plzen, both type I Czech groups. One type I group from Slovakia, VSZ Kosice, has followed still another

development path. Being not a fund but an industrial firm, it has not collapsed or been marginalized but has

returned to its core business with its previously strong capacity. However, it is no surprise also here that Penta had

been interested in control over this company.

Unlike the groups from previous periods, nowadays the biggest groups have quite different operating

possibilities. Whereas at the beginning of transformation the type I and II groups had to deal with both the state

6 Usual schedule for the operation was that in one month these groups or specialized agencies contacted debtors, in less than three months made an agreement or find buyers and then received payments. 7 Since 1996 several investment companies have transformed themselves into holding companies to avoid anti-strategic fund regulation. 8 Charouz group, once a single man-owned company, had in mid 1990s about 1,000 firms in its portfolio.

TYPOLOGY AND DYNAMICS OF FINANCIAL-INDUSTRIAL GROUPS 11

and broad public, now the main partner for the groups in some activities is the state only and in other deals other

powerful groups. Such a situation was possible to see in the case of acquiring claims from the Czech

consolidation agency in volume of billions of CZK or in privatization of important state stakes in strategic

companies, like, e.g., in Czech Telecom or Czech post. In times of voucher privatization there had been disputes

with the government but most activities concentrated on attracting enough individual voucher investors to invest

in particular funds (or to have sufficient number of investors to deposit money in the case of the type II groups).

Although their investment opportunities are limited, their knowledge of how to use existing institutional

environment (especially laws and tender procedures) are deep. Hence, the type III groups are unusually

successful in public tenders organized by the state and usually it is the groups, which appear on short-lists for

such tenders. In some cases, they initiate legal suits to satisfy their claims or to protect their rights. Nevertheless,

FIGs are also successful in usual business. PPF Group, the biggest investment group in Central and Eastern

Europe, received (in 2010) a permission of the Chinese regulator in banking CBRC to found a non-banking

company for providing consumer credits in one Chinese city. This approval gives PPF group the right to

establish—in line with the law on consumer credits adopted in China in 2009—the first company for consumer

credit operations, which will be fully owned by foreign investor. In total in four Chinese cities is to be allowed to

establish firms for consumer credits and these cities/firms should be a pilot for development of this financial

industry in the whole China. Among the recent activities of FIGs belong huge investments into real estates, but

this activity has been reduced since the beginning of the global financial crisis.

Currently, most of the groups mentioned in this paper dynamically develop its activities despite the ongoing

crisis. The largest Italian insurance company Generali has agreed to acquire 49% shares of Generali PPF Holding

(GPH), a joint venture with Kellner’s PPF. Generali, among other things, dominate the Ceska pojistovna (Czech

Insurance Company), which is part of the GPH. For the PPF’s share in GPH Italians pay 2.5 bn euros (about 63.8

bn CZK) (CTK, 2013).

Some Policy Lessons From Transformation Process Related to FIGs

Recent development of FIGs shows that such groups can serve a positive role in post-transformation

economies. It thus confirms the hypothesis that in a transitive economy market uncertainty and instability

motivate firms and other business actors to behave in such a way as to stabilize internally market conditions by

formation of diversified conglomerates. Our analysis indicates that FIGs are very often focused on high profit

margin activities based on deals both with private firms/FIGs and state organizations/institutions. Their economic

power and ability to find and invest in attractive projects make them less vulnerable to crisis—as was shown, e.g.,

by PPF. From a policy perspective is highly discussed the issue of (relative) closeness of these groups. If not

directly person-owned or family-owned then often such groups have a small number of high-stake owners.

An analysis of the groups is important for transitional economies for two reasons: (1) it provides an

explanation of the concentration processes within the economies; and (2) it helps to understand why some

particular modes of privatization and concentration take place and what kind of industrial structure can be

expected to arise in the next future.

To summarize some key elements relevant for other countries one can mention the following ones:

Regulators must stimulate competition and avoid “imperfections” in legislation, which can lead to erosion of

TYPOLOGY AND DYNAMICS OF FINANCIAL-INDUSTRIAL GROUPS 12

competition. Nevertheless, as identified by north, due to active participation of business interest groups in

legislation process (directly or indirectly through lobby groups/persons) such task is very difficult and sometimes

impossible;

Timing and sequencing of steps in reform process can have certain impact on FISGs emergence. However,

initial conditions matter probably more due to the inherent industrial structure of a country than do reforms

specificities;

As the Czech and Slovak cases demonstrate, despite several mistakes of policymakers at the beginning and

during the transition process the resulting post-reform situation is in both countries quite good. Both countries’

competitiveness remains well above those of many other post-reform countries and even global financial crisis

has had a comparatively modest impact on economic development;

Together with foreign direct investments, FIGs has become since their emergence an important vehicle for

exporting investment activities—one most visible example is the one of PPF, which has become the only fully

foreign-owned company receiving a license to provide consumer credit services to population in China. It is

important to note that for PPF this kind of business represent one of the core businesses, which is highly

profitable.

Conclusions

The partial results, which have been presented so far indicate that: (1) group-related process of ownership

concentration is permanent throughout the transition period in both countries; (2) forms and modes of

concentration used by groups have changed over time; and (3) such intermediaries can, in some cases, “maintain”

originally highly concentrated ownership structures of some former state companies unchanged. The dynamics of

different types of groups have widened substantially in terms of durability (persistence), complexity and scope or

profitability. Legal and ethical positions of their operation are also very important from an economic policy

standpoint but for our purposes have been left aside here and therefore were not discussed.

We have shown that the dynamics and structure of different types of groups are important features

explaining, at least partly, why some groups have become more powerful over time while other have either been

rendered unstable or collapsed entirely.

References

Brzica, D. (1996). The role of investment companies and investment fund managers in exercising ownership rights. Russian and East European Finance and Trade, 32(4), 47-66.

Claessens, S., Djankov, S., & Pohl, G. (1996). Ownership and corporate governance: Evidence from the Czech Republic. Retrieved November 8-9, 1996, from http://www-wds.worldbank.org/external/default/WDSContentServer/IW3P/IB/2000/02/24/000009265_3971110141228/additional/117517322_20041117180553.pdf

Coffee, J. C. (1996). Institutional investors in transitional economies: Lessons from the Czech experience. In R. Frydman, Ch. W. Gray, & A. Rapaczynski (Eds.), Corporate governance in central Europe and Russia (pp. 111-186). Budapest: CEU Press.

CTK. (2013). Generali ovládne českou pojišťovnu, odkoupí podíl Kellnerovy PPF. Retrieved from http://www.financninoviny.cz/zpravy/generali-ovladne-ceskou-pojistovnu-odkoupi-podil-kellnerovy-ppf/886027

Demsetz, H. (1983). The structure of ownership and the theory of the firm. Journal of Law and Economics, 26(2), 375-390. Demsetz, H., & Lehn, K. (1985). The structure of corporate ownership: Causes and consequences. Journal of Political Economy, 93,

1155-1177.

TYPOLOGY AND DYNAMICS OF FINANCIAL-INDUSTRIAL GROUPS 13

Ellerman, D. (1998). Voucher privatization with investment funds. The William Davidson Institute Working Paper, No. 167, University of Michigan Business School.

La Porta, R., Lopez de Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1997). Legal determinants of external finance. Journal of Finance, 52, 1131-1150.

March, J. G., & Simon, H. A. (1958). Organizations. New York: Willey. Mertlik, P. (1997). Czech privatization: From public ownership to public ownership in five years? Eastern European Economics, 35,

64-83. Olsson, M. (1999). Ownership reform and corporate governance: The Slovak Privatisation Process in 1990-1996 (Acta Universitatis

Upsaliensis, Uppsala Studies in Economic History No. 49). Olsson, M., & Alasheyeva, J. (2000). Market transparency, ownership concentration and harmonization of law in some east

European countries: A critical note. Paper presented at the conference of Economic Aspects of European Integration. Sweden: Mölle.

Olsson, M., & Brzica, D. (2001). Corporate governance in transitional economies: The case of the Czech Republic. Paper presented at the ACE workshop on Corporate Governance and the Accession Countries, Portoroz, Slovenia.

Pistor, K., & Spicer, A. (1997). Investment funds in mass privatization and beyond: Evidence from the Czech Republic and Russia. Retrieved from http://www.cid.harvard.edu/hiid/565.pdf.

Simoneti, M., Estrin, S., & Boehm, A. (1999). The governance of privatization funds: Experiences of the Czech Republic, Poland and Slovenia. London: Edward Elgar.

Stark, D. (1996). Recombinant property in East European capitalism. American Journal of Sociology, 101(4), 993-1027. Tirole, J. (1991). Privatization in Eastern Europe: Incentives and the economics of transition (draft). Cambridge/Mass:

Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Williamson, O. E. (1975). Markets and hierarchies: Analysis and antitrust implications. New York: Free Press.

Chinese Business Review, ISSN 1537-1506 January 2013, Vol. 12, No. 1, 14-23

Migration in the Middle Asia and Its

Effects on the Labor Market

Füsun ÇELEBİ, Atakan DURMAZ

Bayburt University, Bayburt, Turkey

Many Middle Asia countries declaring their independence after the splitting of the Soviet Union, cannot meet the

economical and social needs of their citizens by falling much behind of the era in terms of industry despite the

natural wealth they have. In addition to all these, the problems in the ruling class and the chaos environment have

resulted in the migration of many people to alternative living spaces. These migrations have affected labor market

both positively and negatively besides the social life. The labor demand increased by the entrance of the immigrants

into the market has affected the employee wages and also this situation has affected the life standards of the citizens.

In this study, the migration that took place in the countries established after the splitting of the Soviet Union,

forming one of the two poles of the world before the cold war, and the effects of this migration on the labor market

have been analyzed considering previous studies on the subject. The studies carried out on this subject have yielded

various results according to the area in which it is carried out, the time interval it includes, and the period’s structure.

For this reason, the points of views on the subject are compared by making a long literature review.

Keywords: migration, labor market, Middle Asia

Introduction

Human being has been obliged to emigrate due to various reasons for centuries. While some have emigrated

as a result of the brutality of sovereigns, others have done so because of such reasons hunger, famine, and

economic factors.

The migrations caused by economic reasons take place generally in a way in which people groups who want

to live in better conditions and earn more lead to more developed countries leaving where they live. These

migrations affect both positively and negatively not only the countries left but also those arrived. The fact that the

unqualified emigrant labor affects the labor market of the country they arrive in as a result of the excess supply

they cause could be considered as the most important one among the negative effects. However, the probable

deduction effect of the immigrant labor power on costs is one of the most important positive effects which should

never be underestimated.

The immigrants affect, in various ways, not only the countries in which they arrive but also in which they

Füsun ÇELEBİ, Associate Professor, Ph.D., Department of Economics, Bayburt University. Atakan DURMAZ, Research Assistant, Department of Economics, Bayburt University. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Füsun Çelebi, Bayburt University, Bayburt, Turkey. E-mail:

DAVID PUBLISHING

D

MIGRATION IN THE MIDDLE ASIA AND ITS EFFECTS ON THE LABOR MARKET 15

were born. The main effect of those is the decrease in unemployment caused by the migration of the unqualified

labor power. Apart from this, the exchange income sent by the emigrants to their homelands is considered as a

very important foreign resource for many countries.

In this study, the effect of migration on the labor market of the countries having been established in Central

Asia especially after the Soviet Union separated is aimed to be analyzed. Firstly, the concept of international

migration and the effects of international migration on labor market will be investigated into and then, the effect

of migration on Central Asia countries is aimed to be discussed.

International Migrations

The increase having been experienced in both national and international migration currencies since the

second half of the 20th century has caused academic studies to be focused on this area. Different reasons cause

individuals to emigrate individually or within groups. In this context, it is possible to explain migration briefly as

the moving of people individually or collectively as a result of economic, social, and political reasons (Şahin,

2001). Thinking more comprehensively, migration is the temporary or stable settlement of people in other places

after leaving the places where they live for the aim of working or providing themselves with better life conditions

(Öngör, 1980).

Migration takes place voluntarily or compulsorily. However, considering the historical events, one can see

that the mass migrations have taken place generally because of compulsory reasons. The Migration of Tribes

which dates back to 4th century when the Huns trying to escape from the sovereignty of China moved towards the

west and settled in the north of Black Sea causing the German tribes who had been living in that region to leave

the region and invade the Europe Continent for years laying the foundations of today’s Eurpoe states, is the first

known mass migration movement (Kinik, 2010). While the mass migrations taking place in different places leads

up to the foundation of new cities and states, the intercontinental migrating has had an oversea dimension since

the American Continent was discovered (Aksoy, 2012). Since the 16th century, many people living in Europe

have migrated collectively to America continent and have settled there. Behind this migration are the economic

reasons. The opportunity of agriculture in the large fields within the new continent and the fact that the overseas

trade developed much have lead people to settle in this continent collectively. Apart from these, nearly 15 million

people have been moved from Africa to America to work as a slave, in the 19th century, millions of people

migrated to America and Europe from China and India for working as contract labors, as a result of the two World

Wars broke out in 20th century, many people have been obliged to leave their homelands (Giddens, 2010).

Europe countries having been tried to be re-established after the Second World War, which have started to

host emigrants from underdeveloped and developing countries to meet the demanded labor power. As this

migration movement depending on economic factors has taken place in parallel with the people’s wishes, it is

possible to be regarded as being based on voluntariness.

General idea about the factors affecting international migration depends on the migration of people from

underdeveloped countries to more developed ones for earn more and to live in better conditions (İçduygu, 2009).

However, this idea has been changing gradually. A kind of migration from developed countries to

underdeveloped ones has been taken place since the developed countries began to spread their economic actions

towards various parts of the world. These are (de Tapia, 2003):

MIGRATION IN THE MIDDLE ASIA AND ITS EFFECTS ON THE LABOR MARKET 16

Permanent settlers;

Permanent contract labors;

Permanent professional workers;

Secret or illegal workers;

Asylum seekers;

Refugees.

According to United Nations, those leaving their homelands and moving to other countries need to stay there

more than one year to mention about international migration (Gençler, 2004). Economic factors, though being an

important factor leading people to move and live in other countries distinct from their homelands, are not the sole

factor. There are several factors apart from economic ones. These could be counted as below:

Migration originating from Economical factors: Migration movements taking place due to people’s wish to

have better jobs, more income, and, accordingly, a better life;

Migration originating from Climatic factors: Migration movements caused by climatic conditions and

natural events. Events such as drought, famine, and natural disasters are leading factors for people’s migration;

Migration originating from Political factors: Migrations caused by the events such as wars, terror, political

pressure which threatens human life. This kind of migration could be caused by problems and instabilities among

different parts of a country while it could be among countries;

Migration originating from educational factors: Migration movements that take place temporarily for

educational purposes. While backward migration could take place as the educational process finishes, permanent

settlement is also possible even after educational process finishes;

Brain drain: Migration of well-educated, qualified, expert individuals of an underdeveloped country to

developed countries for the aim of having better living conditions, a better status, and better income level;

Retired migration: Retired migration, including motivations different from the other migration types, refers

to the migration of people from generally wealthy North America and North Europe to South America and South

Europe costs to spend rest of their life after retirement (Balkiri, Karaman, & Kırkulak, 2008).

Various theories directed at the reasons of international migration have been developed within migration

srudies (Lee, 1996; Wallerstein, 1974). However, the studies carried out accept that the contemporary migration

cannot be connected with only one theory and cannot be measured through one viewpoint (Massey et al., 1993).

Globalization makes it compulsory to evaluate the migration relationship among countries with different

dimensions.

The Effect of International Migration on Labor Market

According to a study carried out by United Nations: more than 175 million people, 3% of the world

population, live in places different from their homelands (Borjas, 2006). Many developed countries, especially

the USA, Canada, and Australia, host these emigrants. The amount of emigrant population hosted by developed

countries has reached high levels, 11% of France’s population, 9% of Germany’s population, 11% of

Switzerland’s population, and 7% of United Kingdom’s population is comprised of foreign originated people.

These crowded emigrant groups have great impacts on both social and economical structure of the countries in

which they live. Important conflicts caused by cultural differences and economic factors can be observed

MIGRATION IN THE MIDDLE ASIA AND ITS EFFECTS ON THE LABOR MARKET 17

between the natives and emigrants especially during crisis periods.

The effect that emigrants have on the labor power of the host countries has been an important subject on

which many academics have studied. However, contrary to the general opinion, it has been revealed as a result of

the studies carried out in the USA and many European countries that migration has no or very little effect affect

on the native workers employment or their salaries (Dustmann, Fabbri, & Preston, 2005). However, considering

the studies analyzing the effects of migration in detail, the effect of migration on labor market varies according to

the qualified worker portion in total emigrant group and the labor market’s structure.

The fact that migration towards OECD countries is more than the rest of the world and also there has been a

gradual increase during the recent years is stated in the study carried out by Docquier, Özden, and Peri (2001). It

was revealed in 2009 that 10% of the OECD countries’ population is foreign originated people. However,

contrary to what is believed in this study, it has been revealed that the many migration movements among OECD

countries have been from one OECD country to another and the portion of high-school graduate in the emigrant

group is higher than those in the migrated country. Accordingly, it can be said that the migration towards the

OECD country is mainly brain drain. It has been revealed that as those migrating to OECD countries are

generally qualified workers, although migration movement towards this region affects employment and salaries

of the unqualified workers in that country negatively, it has no negative effect on the qualified works.

The Structure of Migration in Central Asia and the Effect of Labor Migration on Employment Market

Central Asia countries’ population has been in a new structuring process since the Soviet Union separated

and new 15 states established. While, initially, migration intention was high because of political and ethnical

conflicts, economic reasons came forward later. Especially after the Soviet Union, as the structure of migration is

analyzed within five different periods, the reasons why the region’s people headed towards come up. In the first

step (1991-1992), population movements were the same as in the last years of 1980s, and were shaped according

to discriminations and ethnical based conflicts. In the second step of migration period (1993-1995), political and

ethnical factors continued their dominance, while about 57% of originally Kazakh migrants live in emergent

countries, the rest live in Mongolia (Korobkov, 2007). In the third step (1996-1999), as political factors lost their

significance, social and economic factors accelerated the region’s people’s movements. In this period, while the

number of emigrants arriving in Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, and Moldova decreased, there was an increase in both

permanent and temporary labor migration in Azerbaijan and Central Asia. Also, the growing bureaucratic

structuring, the effects of international laws and the negative attitudes towards emigrants slow down the

migration tendency. In the fourth step (2000-2005), there were attempts to construct legal infrastructure of

emigrant policy, while in the fifth step, after 2005, there was a process in which temporary emigrants were made

permanent, and employees were punished in case of employing illegal emigrants (Korobkov, 2007).

In Figure 1, the increase portion of migration towards Russia between 1992 and 2010 is shown. After the

country separated, while the highest amount of migration was in 1994, the number of people migrating decreased

in the following years and reached its lowest number in 2003. The number of migration in 2003 increased less

than those in 1990s, and as of the year of 2010, being in a decrease proccess, reached a number of below 200

thousand.

MIGRATION IN THE MIDDLE ASIA AND ITS EFFECTS ON THE LABOR MARKET 18

Figure 1. The increase in the migration amount of Russia between 1992 and 2010 (Thousand).

Table 1

Country Based Distribution of Those Migrated Between 1997 and 2010

1997 2000 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010

Azerbaijan 29,878 14,906 4,600 8,900 20,968 23,331 22,874 14,500

Armenia 19,123 15,951 7,581 12,949 30,751 35,216 35,753 19,890

Belarus 17,575 10,274 6,797 5,619 6,030 5,865 5,517 4,894

Kazakhstan 235,903 124,903 51,945 38,606 40,258 39,964 38,830 27,862

Kirghizistan 13,752 15,536 15,592 15,669 24,731 24,014 23,265 20,901

Moldova 13,750 11,652 6,569 8,649 14,090 15,519 16,433 11,814

Tadzhikistan 23,053 11,043 4,717 6,523 17,309 20,717 27,028 18,188

Turkmenistan 16,501 6,738 4,104 4,089 4,846 3,962 3,336 2,283

Uzbekistan 39,620 40,810 30,436 37,126 52,802 43,518 42,539 24,100

Ukraine 138,231 74,748 30,760 32,721 51,492 49,064 45,920 27,508

Total 547,386 326,561 163,101 170,851 263,277 261,170 261,495 171,940

Considering the migration data about countries between 1992 and 2010, it is observed that there are 547,386

emigrants in 1997, and also while Kazakhstan comprises 43% and Ukraine comprises 25% of this amount, the

rest is comprised of Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan, and Tadzhikistan. It is possible to conclude the fact that as Kazakh

language became dominant in Kazakhstan, Kazakhs had a voice in policy and economy, and there was a weak

economy in that region, there has been an increase in the number of emigrants (Dornis, 1997). Migration from

Kazakhstan to Russia decreased after 1997, and the number was 27,862 in 2010. The reason for this decrease was

0

200

400

600

800

1000

1200

Increase of migration (thousand)

MIGRATION IN THE MIDDLE ASIA AND ITS EFFECTS ON THE LABOR MARKET 19

the improvement in Kazakhstan’s economy despite the recession in Russia’s economy (Salt, 2005). In the same

way, the number of emigrants from Ukraine to his close neighbor has decreased until 2007, and although it

increased again in 2007, it started to decrease again after 2007. The emigrants leaving Ukraine prefer not only

Russia, but also East Europe, Germany, and Israel with the intention of settling, depending on the economy in

Russia (Rybakovsky & Ryazantsev, 2005). Such factors as militarial ethnical conflicts, downwardness of Russia

population and Russian language in Kirghizistan have affected the migration process, and although it increased in

the years between 1997 and 2007, Russia was at the fourth place among the emigrant countries in 2010. As

people migrating from Kirghizistan are high qualified people, their migration causes a decrease in the country’s

economically active population and qualified workers working in the industrial, transportation, construction

sectors (Ergeshayev, 2006). While, general the number of people migrating from Uzbekistan to Russia is

fluctuating, it was 24,100 in 2010. As a result of the economic growth in Kazakhstan and Russia, the number of

people migrating from Tajikistan and Uzbekistan increased in 2007, and then it decreased due to the economic

crisis (Abdullaev, 2008).

The Structure of Labor Migration in Central Asia and Its Affect on Labor Market

The fact that life standards decreased and unemployment increased with the shift into market mechanism in

Central Asia led people to search for alternative income resources in various countries. Accordingly, this fact

accelerated labor migration (Korobkov & Zaionnchkovskaia, 2004). After Soviet Union separated, people from

Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kirghizistan, Armenia, Moldova, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Ukraine started working in

Russia without getting visa. A large amount of the workers is comprised of males, and also most of them works at

construction, services, trade, and agriculture sectors (Retrieved from

http://www.ios-regensburg.de/fileadmin/doc/ios_db/Remittances_CIS12_2004-2008.pdf).

As it can be seen from Table 2, the share of remittance income in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is

Tajikistan with an amount of 31% followed by Moldova and Kirghizistan respectively. It is possible to conclude

the fact that migration tendency has increased in Tajikistan as educational processes are left half finished because

of the civil war, large amount of the population work at agricultural sectors whose average salary is low, and their

qualifications are inadequate (Marat, 2009). Migration tendency in Moldova varies in three ways. In the first step,

it was generally for economical and commercial purposes because of the high poverty level depending on the

effects of economic crisis in Russia in the second step after 1997. In the same way, the period after 2007 refers to

a period in which the share of Moldavian exists in foreign labor market, and the remittance income increases

except for 2009 (Retrieved from

http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTECA/Resources/WBMoldovaReport.pdf). The fact that remittance

income in Kirghizistan increases except for 2009, the crises in Kazakhstan and Russia led both countries impose

a quota on those to be employed refer to a decrease in remittance in 2009 (Retrieved from

http://www.warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/pais/researc/nsc/projects/templer/publications/cg_central_asia_migrants_and

_the_economic_crisis_in_pdf.pdf). While, the portion of outflow of foreign currency by workers in Gross

Domestic Product is most in Tajikistan with an amount of 15.2%, Kirghizistan’s share is 6.2%. It is determinable

that the outflow of foreign currency is shaped according to those transferring from Kirghizistan to Tajikistan and

Uzbekistan, and from there to Russia and Kazakhstan (Collins, 2006).

MIGRATION IN THE MIDDLE ASIA AND ITS EFFECTS ON THE LABOR MARKET 20

Table 2

Workers Remittance Inflow and Outflow in Central Asia Countries Between 1997 and 2011

Transfer Inflow Million USD

1997 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011e % of GPD 2010

Azerbaijan .. 54 57 104 182 171 228 693 813 1.287 1.554 1.274 1.432 1.885 2.5

Armenia 136 95 87 94 131 168 435 498 658 846 1.062 769 996 1.254 8.8

Belarus 295 209 139 149 140 222 257 255 340 354 680 589 589 722 1

Kazakhstan 60 64 122 171 205 148 166 178 186 223 192 261 291 270 0.2

Kirghizistan 3 18 9 11 37 78 189 322 481 715 1.232 992 1.275 1.500 20.8

Moldova 20 112 179 243 324 487 705 920 1.182 1.498 1.897 1.211 1.392 1.562 23.2

Tadzhikistan .. .. .. .. 79 146 252 467 1.019 1.691 2.544 1.748 2.254 2.680 31

Turkmenistan .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ..

Uzbekistan .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ..

Ukraine 12 18 33 141 209 330 411 595 829 4.503 5.769 5.073 5.607 6.619 3,9

Transfer out flow million USD

Azerbaijan 19 77 101 142 235 169 200 269 301 435 593 652 961 .. 1.9

Armenia 5 12 5 21 24 27 138 152 154 176 185 145 157 .. 1.8

Belarus 141 97 58 77 68 65 82 95 93 109 141 112 104 .. 0.2

Kazakhstan 522 356 440 487 594 802 1.354 2.000 3.033 4.303 3.559 3.058 3.020 .. 2

Kirghizistan 29 51 45 55 57 55 83 125 150 220 196 188 297 .. 6.2

Moldova 20 25 46 59 57 67 67 68 86 87 115 104 117 .. 2.2

Tadzhikistan .. .. .. .. 13 64 119 145 395 184 199 124 856 .. 15.2

Turkmenistan 4 .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ..

Uzbekistan .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ..

Ukraine 4 3 10 5 15 29 20 34 30 42 54 25 24 .. 0

Note. “..” means data not available; e: estimate.

Table 3

Average Salaries and Wages Between 1994 and 2008 (Dollars)

1994 1998 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2008

Russia 110 108 79 111 139 179 234 305 391 718

Azerbaijan 13 44 49.5 55.8 64.9 78.8 101.2 130.8 166.8 317

Armenia 6 36 42.1 44.1 47.7 60.1 81.4 113.7 149.8 293

Belarus 27 106 73.6 86.6 104 120 160 215 271 396

Kazakhstan 48 119 101 117.9 132 154 208 256 323 485

Kirkhizistan 22 40 25.7 39 35 43 52 63 81 137

Moldova 26 47 32 42 51 63 89 104 129 245

Tadzhikistan 16 12 8.5 9 11 14 20 26 35 63

Turkmenistan .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ..

Uzbekistan 27 47 .. 39 39 41 52 .. .. ..

Ukraine 45 63 42 57 70 86 110 157 206 356

Note. “..” means data not available.

MIGRATION IN THE MIDDLE ASIA AND ITS EFFECTS ON THE LABOR MARKET 21

According to Table 3, average salary in Russia increases generally except for that in 1998, crisis period, and

reached 718 dollars in 2008. In the same way, average salary in Kazakhstan too, is higher than many other

countries, and increases except for 2000. Apart from Kazakhstan, the countries with high salaries are Ukraine,

Belarus, and Azerbaijan followed by Armenia and Moldova. The countries with lowest salaries are Kirghizistan

and Tajikistan. The fact that remittance income is highly results in the migration of people to countries with

higher salaries to have better life standards. In January, 2012, while the average salaries are supposed to be 795

and 630 dollars in Russia and Kazakhstan respectively, it is supposed to be about 110 dollars Tajikistan

(Retrieved from http://news.am/eng/news/101025.html). It is known that Russia’s economy will grow and

remittance income will increase by means of the increase in oil prices and economic recovery. Also, according to

the forecasts, remittance out flow from Europe and Central Asia will rise from 6.5% to 10.4% from 2011 to 2012.

Conclusions

After the separation of Russia, the second biggest migration-receiving country, while ethnic origin based

migration tendency of those Russian originated and Russian speaking increased, the structure of migration

changed depending on the economic disruption. The civil wars in Tajikistan, Kirghizistan, and

Azerbaijan-Armenia regions prevented people from finishing their education and getting qualified training. In

this period, at the same time, with the shift into market economy, the fact that new arrangements were made and

they could not find positions suitable for their qualifications led people to search for new ways of income.

Accordingly, the process of migrating to close neighbours started and then continued towards Europe Countries,

Israel, and America. It can be said that the citizens of the region migrate to other places with higher average

salaries to get better life standards and live in better conditions, and especially those in Kirghizistan, Tajikistan,

and Uzbekistan headed for Kazakhstan and Russia. Also, the fact that the exchange income comprises a large

amount of gross Domestic Product of Tajikistan, Kirghizistan, and Moldova underlines again the importance of

emigrant income. As Russia made it easier to get visa for the places where it was dominant, labor migration

increased significantly and it became an important country in terms of outflow of foreign currency. Labor

migration, playing an important role on such sectors as construction, services and trade, is expected to increase

even if it would not be at the same lever with that in 1990s. It could be said that Russia’s and Kazakhstan’s

continuing economic growth depending on the increases in oil prices will be important for Tajikistan,

Kirghizistan and Uzbekistan from where they allow immigrants, and also the number of people migrating will

increase. Accordingly, as a result of the economic crises, countries will set measures to present employment