Canonical Sites and the Legacy of Place in American Archaeology

Transcript of Canonical Sites and the Legacy of Place in American Archaeology

1

Canonical Sites

and the Legacy of Place

in American Archaeology

James E. Snead

California State University,

Northridge

Figure 1. A. V. Kidder’s car at Pecos NationalMonument, NM. Photo: Author

Presented in the Symposium “The Convergence of History and Space: Historically-chargedplaces in the archaeological record of North America,” organized by Matthew Sanger. 79thAnnual Meeting of the Society for American Archaeology, Austin, April 25, 2014.

Abstract. Histories of American archaeology remain largely divorced from the places in whicharchaeological work has taken place. Our general preference for exploring trajectories ofprofessionalism has left out many significant stories: the general lack of interest in landscape isparticularly ironic since engagement with material contexts is fundamental to the archaeologicalprocess. At various times in our history, specific places have played critical roles in thestructuring archaeological interpretation. These “canonical sites” (following Rosemary Joyce’s“canonical artifacts”) were visited, studied, and attracted considerable comment. Their centralityto the narrative, however, is often completely idiosyncratic, reflecting proximity to travel routes,aesthetic appeal, or other values that are relevant only to the Euro-American viewer.

This paper looks at a canonical site of central importance to the development of Americanarchaeology in the first half of the 19 century: the Grave Creek Mound. This site can be visitedth

today, but in contrast to its 19 century notoreity contributes little to the modern archaeologicalth

syntheses of its surroundings. Viewed in context, however, it provides an example of therelationship between history, place, and the canon construction in archaeological thought.

Introduction

At the edge of a stand of juniper and piñon pine, on a flat, grassy river terrace in anorthern New Mexico valley, sit the remains of A. V. Kidder’s car (figure 1.). Not far away arethe remains of the archaeological camp set up by his team while excavating nearby Pecos Puebloin the 1920s. To complete the picture, Kidder’s own ashes—and those of his wife, MadelineAppleton Kidder—are interred in the same grove of trees. No path leads to this place, but thescattering of potsherds around the plaque suggests a degree of cognizance and respect expressedby practitioners of the craft for this otherwise entirely hidden locale.

2

The juxtaposition of evidence for archaeological practice with significant research sitesand even the mortal remains of scholars themselves highlights the intricate relationship betweenhistory and place in American archaeology. This should not be surprising, given archaeology’sposition at the intersection of history and material culture. And yet linkage between ideas ofplace and the construction of archaeological knowledge has received remarkably little attention. Our concerns continue to be with intellectual trends, with the development of the profession, andwith aspects of institutional/individual histories. This plays out quite differently in Europe andelsewhere and is shaped by the profound gulf between Euro-Americans and the indigenous past. These circumstances make the opportunity to grapple with “place” and the history of archaeologyin the United States particularly significant.

Figure 2. Beloit College, Wisconsin, illustrating mounds in association with the @ 1847 Middle College Building. Photo: Author

Understanding issues of place within the history of archaeology engages a series ofconnections. The plurality of our scholarship on the topic grapples with concepts of place as theypertain to culture and society in the past and hence the archaeological record. How we replacethese locales within our own conceptual frameworks follows, and then understanding how suchreconstituted places in turn shape interpretation going forward, leaving traces even when theoriginal has been forgotten. The step that interests me concerns how such places have defined ourapproach to the past, broadly construed: how has the engagement with place, and the recollectionof such encounters, shaped our own traditions of inquiry?

A 2012 paper by Rosemary Joyce on the role of “things” in the construction of thearchaeological canon has inspired my thoughts on this topic. Such “canonical objects,” as sheindicates, frame our understanding of entire classes of artifacts, or of particular cultures. Reproductions, exhibitions, and the circulation of associated imagery are all elements of suchconstructions. As opposed to canonical objects, “canonical places,” by definition, cannot bemoved. As with other forms of landscape, however, fixity is more a conceptual framework thanan accurate state. As events move around them, such landmarks are subject torecontextualization, reconfiguration, and even obliteration. But their scale provides feweropportunities for control than artifacts, which makes them contested ground.

A theoretical framework relevant to “canonical places” is suggested in a recent study ofthe history of the site of Kuaua, in northern New Mexico, also known as Coronado StateMonument. Drawing particularly from Foucault and Soja, they discuss the history of the locality,first excavated and interpreted for the public in the 1930s. Naming, representation, authenticity,

3

and peformance are all engaged in places such as Kuaua, which they describe as “transmittersand receivers of memory, and cultural identities” (Preucel and Matero 2008: 97).

Figure 3. Entrance, Coronado State Monument. Photo: Author

Kuaua is perhaps of greatest significance in the context of historical preservation, ratherthan any role in the intellectual structure of American archaeology. Places of this character,however, loom in our historical narratives, including monumental localities such as PuebloBonito and Cahokia. Of equally great interest are places that once attracted interest, but haveover time changed in perceived significance. Such “shifts” imply reformulation and competitiveconstructions of value, hence sites connected to the formation of identity.

This paper looks at a particular canonical place in American archaeology, the GraveCreek Mound. Perhaps the most well-discussed indigenous feature of the Ohio landscape in thefirst half of the 19 century, this site nonetheless slipped from interest by the time of the Civilth

War. Consideration of the issues that made it notorious—and the ways that uses of theindigenous past were thereby contested—makes it a distinctive case study for understanding therelationship between place and history in American archaeology.

The Grave Creek Mound

Located along the Ohio River downstream from Wheeling, the Grave Creek Mound is amajor construction of the Adena/Hopewell era, 20 meters high and 75 meters in diameter. Firstnoted in the 1770s, it was called simply “The Grave,” the “Big Grave”—or, more poetically, the“Sepulchre of the Aborigines” (Cresswell 1924 [1774-1777]: 71; Smith 1928 [1837]: 196). Several references to the site appeared in publications in the first few decades after Americanindependence, with hundreds of visits implied (Norona 1953: for example, 1788–Cutler andCutler 1888: 410; early 1790s–Hart 1793: 215; 1796–Ellicott 1803).

Two contemporary accounts from the first decade of the 19 century illustrate theth

different ways that the Big Grave was conceptualized by the American public. 1805 theMassachusetts antiquarian Thaddeus Mason Harris visited the site as part of a western tour, Hedescribed and measured the locale, noting that even at this early date artifacts found nearby hadbeen “deposited in Mr. Turrell’s Cabinet of Curiosities in Boston.” The majority of Harris’saccount, however, consisted of learned extrapolation regarding the builders of the Big Grave. Atlength he concluded that they had been the Scythians of Central Asia, an argument based on

4

scholarly traditions pertaining to mound-building societies (Harris 1805: 63; c.f., Norona 1953,1964).

An entirely different concept of place at the Big Grave was expressed just a few yearslater by the traveler Fortescue Cuming, who made the short walk up to the site from a flatboatlanding at the mouth of Grave Creek. Cumming’s description of the Big Grave was similar tothat of Harris, referring the scale of the monument, its local associations, and to recentunsuccessful excavations by the neighbors. Cuming’s final remark, however, placed the BigGrave more thoroughly in the human context of the settlement of the Ohio Country. “The bark ofthe trees which crown this remarkable monument,” he wrote, “ is covered by the initials ofvisitors cut into it, wherever they could reach—the number of which, considering the remotesituation, is truly astonishing” (Cuming 1810: 98). Relatively muted on the subject of intellectualcapital, his interest focused instead on the role of the mound into a cultural landmark for nearbysettlers or those passing through.

Thus from an early era “places” associated with indigenous heritage in North Americahad already acquired divergent and potentially competitive meanings. Harris perceived the BigGrave as a source of antiquarian capital, a touchstone for comparison to things more familiar toan international scholarly audience, and possibly a source of material but equally alienablecapital, such as artifacts for display. Cumming recognized this tradition but emphasized the BigGrave’s position in the Ohio landscape as it was experienced by immigrants. It was in this way awaypost along the river headed the West, marked by travelers in an almost ritualized fashion asthey moved on to new lives. An interesting contrast to this evidence for population mobility,however, was the ownership status of the mound itself. The Tomlinson family had lived onGrave Creek Flats since the 1770s, and were considered stewards of the site: by repute theywould “not suffer the axe to violate its timber, nor the mattocks its earth” (Doddridge 1824: 27-28).

Accounts of the Big Grave were commonplace in secondary discussions of Americanantiquities from the 1810s onward (c.f., Haywood 1819: 198.), despite the fact that few of theformal antiquarian commentators of the era—such as Caleb Atwater, Dan Drake, andConstantine Rafinesque—published remarks on the mound from first-hand experience. Other references, however, indicate that the site’s status as a regional landmark continued (c.f. TheExtra Magazine Almanac 1811: 52; Priest 1833: 38; Smith 1928 [1837]: 196; Ward 1992[1823]). Eventually the mound was noted by erudite foreign travelers, including Charles Lyelland Charles Dickens, neither of whom stirred from the decks of their respective riverboats tovisit (Dickens 1842; Lyell 1845: 32). The familiarity of this monument to western audiencesindicated that after two generations of experience the Big Grave had become a part of anincreasingly historicized—and relatively protected—Euro-American landscape.

These circumstances changed, however, in the late 1830s, when ownership of the BigGrave passed to a new generation with more entrepreneurial ambitions. Abelard Tomlinson andhis brother-in-law Thomas Biggs, began excavating the Big Grave in the summer of 1838, andwithin weeks had opened shafts into the mound from the top and sides (Norona 1964: 16). Although it was clear that they hoped for major discoveries, their innovative plan was to

5

“wall the shafts and drifts, and on the top over the shaft erect a neat, tastefulsummer house, three stories high. This arrangement will enable visitors at alltimes to explore the interior of the mound, as well as to view the exterior, andlikewise view in appropriate cases constructed for the purpose...all the relicsfound within the vaults (Townsend 1962 (1839):18).

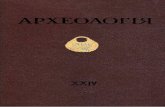

Figure 4. The Grave Creek Mound, early 1840s. Montroville Wilson Dickeson: Courtesy University of Pennsylvania Museum Archives

The interior of the mound itself was converted into an exhibit that would allow theviewer to “trace the progress of human improvement from one degree to another, through a longseries of ages to the present time.” The space itself was denoted as a “rotunda” with 9-footceilings. A circular brick column at the center filled up the vertical shaft and was ringed by a“shelf provided with wire cases, in which the bones, beads, ornaments, and other objects ofinterest, found in the vaults, are arranged.” The most dramatic feature of the tableau was arelatively complete skeleton, a “grim piece of ancient anatomy. . . fastened against the shaft ofthe rotunda and defended by a wire screen” (Townsend 1962 [1839]: 18; Schoolcraft 1843: 388,412).

Tomlinson protected his investment by fencing off the mound, and visitors who arrivedwhile the museum was being organized were not allowed to see the discoveries. Ultimatelyadmission cost 25 cents. It was not for the faint of heart, since in addition to the macabredisplays the atmosphere was described as both “damp and acrid,” with chunks of precipitatedropping from the ceiling (The Ohio Statesman, 4 October 1839 [reprinted from the BaptistBanner]; Townsend 1962 (1839):18, 10; Schoolcraft 1842: 388; Norona 1953: 13).

This shift in perception of the mound from a cultural landmark to a proprietaryenterprise was consistent with evolving western sensibilities regarding the landscape as autilitarian and conceptual resource. The intellectual response to the Grave Creek Moundexcavation, however, remained distinctly disengaged from the locality itself, focusing instead onanalysis of anatomy and artifacts. These two perspectives about the Big Grave were starklyjuxtaposed during the visit of Henry Rowe Schoolcraft in 1843. Having first seen the mound in1818 while traveling West—when he, too, marveled at the the inscriptions on thetrees—Schoolcraft returned as an antiquarian emissary of the American Ethnological Society,

6

New York (Schoolcraft 1845; 1851a: 21). This second visit was provoked not by the novelapproach to the display of antiquities, but by a particular find: the “Grave Creek Stone,” thoughtto be engraved with an undeciphered script.

The Grave Creek Stone was significant in the context of the intellectual debate overNative American origins both because it was apparently a “text” and because it impliedEuropean connections. Questions of history and origin remained pre-eminent in formalantiquarian circles, and this single find had potentially great significance. Schoolcraft dutifullydescribed other excavated artifacts, and documented additional sites on the Grave Creek Flatsbeyond the main mound itself, but these observations were put to limited use. Instead,antiquarians in New York, London and Copenhagen scrutinized the stone, which generatedcontroversy for decades (see Williams 1991: 82-87).

Schoolcraft later provided one of the few preserved references we have to a thirdperspective on the Big Grave. Although possibly apocryphal, the episode he describes is one ofthe only additional observations of a visit to the museum, this time by a Native American.

An old Cherokee chief, who visited this scene, recently, with his companions, onthe way to the West, was so excited and indignant at the desecration of thetumulus, by this display of bones and relics to the gaze of the white race, that hebecame furious and unmanageable; his friends and interpreters had to force himout, to prevent his assassinating the guide; and soon after he drowned his senses inalcohol (Schoolcraft 1851b: 313).

That the museum was seen in competitive terms by the more formally-constitutedantiquarian community is made quite clear by scornful remarks made after the failure of theenterprise in 1843. In the words of Ephraim Squier,

“The excavation proved to be, pecuniarily, a ‘bad operation.’ The ‘rotunda’ hasfallen in, the bolts and bars have vanished, and the gate to the enclosure no longerrequires the incantation of a dime to creak a rusty welcome to the curious visitor.

“ ‘Sic transit gloria moundi’ [Squier 1848a: 206fn. Emphasis in original].

In the decades following the museum’s closure, references to the Big Grave ignore thesite itself almost entirely in preference to objects alienated from the vicinity. Intact skulls, forinstance, were prized, and one from the Big Grave ended up on the possession of Philadelphiaanatomist Samuel George Morton (Morton 1839: 221; see Fabian 2010). The obscurity ofreferences to additional excavations—found only in regional newspapers and correspondence(c.f., The Ohio State Journal, 12 December 1853; Norona 1953: 35)—also denote a shift ininterest. The intellectual climate continued to discount place-based information, a stance thatpersisted even as a more formalized archaeology took root in western institutions in closeproximity to the mounds. In 1879, for instance, claims for the Grave Creek Stone’s exotic originwere debunked by a panel of scholars from the Ohio Archaeological and Historical Society,Wooster College, and other centers of local knowledge, without particular reference to the site

7

itself (Read 1879; c.f., Whittlesey 1865; c.f., St. Louis Academy of Science 1878: cxxxv).Of courset he Big Grave itself did not disappear. Through the 1850s and 60s it served as

the platform for a “saloon,” a dance hall and an artillery emplacement. It was eventuallysurrounded by the town of “Moundville,” and acquired the faux-medieval West Virginia StatePenitentiary as a neighbor. It was apparently due to local agitation that the site was acquired bythe state government in 1909. Despite this, it was not until 1945 that a museum was constructedat the Grave Creek Mound, followed by National Register nomination in 1966, state park statusin 1967, and National Historic Landmark in 1992 (Norona 1953 ).

Figure 5. The Grave Creek Mound in the late 19 Century.th

Conclusion

Considering the Grave Creek Mound as a canonical place in American archaeology shedsunique light on 19 century concepts and practices. In particular, place-focused history providesth

an opportunity to examine the engagement of different communities of interest concerned withantiquities in the landscape. In such a framework intellectual preoccupations can be shifted fromthe center and contextualized along with the very tangible perceptions and actions of people “onthe ground.” To borrow a concept rarely used in the American context, the approach that emergesis chorographic—a form of historical topography, rooted in a diachronic landscape.

The history that emerges is complicated. Contingency cannot be expected to generateneat patterns. But evidence for divergent perspectives—in particular, conflict over the creationof knowledge—allows for a contextual understanding of archaeological practice. The canon, itsdominance but also its mutability, is as firmly grounded in place as it is in artifacts and ideas.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Matthew Sanger for organizing this panel, and to discussants Steve Lekson andChristopher Witmore. This project is supported by the Wenner-Gren Foundation forAnthropological Research and is part of a larger project, Relic Hunters: Encounters withAntiquity in 19 Century America. Imagery from the University of Pennsylvania Museumth

Archives, courtesy Alex Pessati, is appreciated. Support of the College of Social and BehavioralSciences/Oviatt Library, California State University, Northridge, is also acknowledged.

8

References Cited

Cuming, Fortescue1810 Sketches of a Tour to the Western Country through the States of Ohio and Kentucky.

Cramer, Spear & Eichbaum, Pittsburgh.

Cutler, William Parker, and Julia Perkins Cutler1888 Life, Journals, and Correspondence of Rev. Manasseh Cutler, LL.D. Robert Clarke &

Co., Cincinnati.

Dickens, Charles1842 American Notes for General Circulation. Wilson & Co., New York.

Ellicott, Andrew1803 The Journal of Andrew Ellicott, Late Commissioner on Behalf of the United States. Budd

& Bartram, Philadelphia.

The Extra Magazine Almanack 1811 The Extra Magazine Almanack. Cramer, Spear & Eichbaum, Pittsburgh.

Doddridge, Joseph1824 Notes on the Settlement and Indian Wars, of the Western Parts of Virginia &

Pennsylvania. Wellsburg, VA.

Fabian, Ann2010 The Skull Collectors: Race, Science, and America’s Unburied Dead. University of

Chicago Press, Chicago.

Haltunnen, Karen2006 Groundwork: American Studies in Place. American Quarterly 58(1): 1-15.

Harris, Thaddeus Mason1805 The Journal of a Tour into the Territory Northwest of the Alleghany Mountains; Made in

the Spring of the Year 1803. Manning & Loring, Boston.

Hart, Jonathan1793 A Letter from Major Jonathan Hart, to Benjamin Smith Barton...containing observations

on the Ancient Works of Art, the Native Inhabitants, &c. of the Western-Country. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society Vol. III, pp. 214-222.

Haywood, John1819 The Christian Advocate. Thomas C. Bradford, Nashville.

9

Joyce, Rosemary2012 Businessmen, Naturalists, and Priests: The Material Past Before Professional

Archaeology. Paper presented in the symposium "Places, Objects, Bodies, Art: MaterialConstructions of Antiquity," 77 Annual Meeting of the Society for Americanth

Archaeology, Memphis, April 19-22.

Lyell, Charles1845 Travels in north America; with Geological Observations on the United States, Canada,

and Nova Scotia. John Murray, London.

Morton, Samuel George1839 Crania Americana: A Comparative View of the Skulls of Various Aboriginal Nations of

North and South America. J. Dobson, Philadelphia.

Naylor, Simon 2011 Geological Mapping and the Geographies of Proprietorship in Nineteenth-Century

Cornwall. In Geographies of Nineteenth-Century Science, edited by David N.Livingstone and Charles W. J. Withers, pp. 345-370. The University of Chicago Press,Chicago.

Norona, Delf1953 Skeletal Material from the Grave Creek Mounds. West Virginia Archaeologist 6: 7-42.

1964 Moundsville’s Mammoth Mound. West Virginia Archaeological Society, Moundsville,WV.

Preucel, Robert W., and Frank G. Matero2008 Placemaking on the Northern Rio Grande: A View from Kuaua Pueblo. In Archaeologies

of Placemaking, edited by Patricia E. Rubertone, pp. 81-100. One World Archaeology 59.Left Coast Press, Walnut Creek, CA.

Priest, Josiah1833 American Antiquities and Discoveries in the West. Third edition (rev.). Hoffman and

White, Albany.

Reid, M. C.1879 Inscribed Stone of Grave Creek Mound. American Antiquarian and Oriental Journal

1(3): 139-149.

St. Louis Academy of Science1878 Journal of Proceedings. Transactions of the St. Louis Academy of Science: iii-cclxxv.

10

Schoolcraft, Henry R.1845 Observations Respecting the Grave Creek Mound in Western Virginia. Transactions of

the American Ethnological Society I, pp. 369-422.

1851a Personal Memoirs of a Residence of Thirty Years with the Indian Tribes on the AmericanFrontiers. Lippincott, Grambo, & Co., Philadelphia.

1851b the American Indians. Their History, Condition and Prospects. Wanzer, Foot and Co.,Rochester. [2 edition? Cite].nd

Smith, William Rudolph1928 Journal of William Rudolph Smith. The Wisconsin Magazine of History 12(2): 192-220.

Squier, Ephraim G.1848 Observations on the Aboriginal Monuments of the Mississippi Valley. Transactions of

the American Ethnological Society II: 131-207.

Townsend, Thomas1965 [1839] Grave Creek Mound. West Virginia Archeologist 14, pp. 10-18.

Ward, Henry Dana1992 [1823] A Traveler’s Journal of a Tour from Athens, Ohio, to Boston Mass by the way of

the Lakes and the Clinton Canal. Transcribed by Robert J. Cormier.

Whittlesey, Charles1865 Abstract of a Verbal Discourse Upon the Mounds and the Mound Builders in Ohio.

Delivered before the Fire Lands Historical Society at Monroeville, Huron County, Ohio,March 15, 1865. MS on file, American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, MA.