“Breathing Machines. Inspiration and Interdependence in Contemporary Art Installations”. Die...

Transcript of “Breathing Machines. Inspiration and Interdependence in Contemporary Art Installations”. Die...

Marc Caduff / Stefanie Heine / Michael Steiner (Hgg.)

Die Kunst der Rezeption

AISTHESIS VERLAGBielefeld 2015

© Aisthesis Verlag Bielefeld 2015Postfach 10 04 27, D-33504 BielefeldSatz: Germano Wallmann, www.geisterwort.deDruck: docupoint GmbH, MagdeburgAlle Rechte vorbehalten

ISBN 978-3-8498-1069-6www.aisthesis.de

Bibliografische Information der Deutschen NationalbibliothekDie Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar.

Stefanie Heine

Breathing Machines

Interactive Installations in Contemporary Art

In recent years, one can observe an emergence of interactive art installations related to breathing. The works I focus on do not represent breath, but actu-alise it – they produce, transform or transmit artificial breathing by technical, that is mechanical, electronic or digital means. The works can be considered as machines in the broadest sense of being artificial contrivances or construc-tions; machines that breathe and that, due to their interactive dimension, are breathed into by the recipients. To begin, I want to give a few examples of such installations, or breathing machines.1

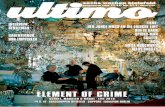

Ill. 1: Scott Sona Snibbe. Blow Up © Scott Sona Snibbe.

1 The number of examples could be extended. To name just two: Ulrike Gabriel: Breath (1992-1993); Werner Reiterer: Breath (2006-2010).

68

Scott Sona Snibbe’s Breath Series consists of different variations of installa-tions in which the visitors’ breath is recorded, translated and amplified. Blow Up2 (ill. 1) records the breath of a visitor who blows into a small input device “electronically linked to a large wall of twelve electric fans”3. The large fans then mirror the breathing pattern received by the small input device. The participants’ actual breath thus literally animates or inspires the installation – their exhalations are externalised and transformed into movement which activates the rhythmical blows of the fans.

Ill. 2: Nils Völker. One Hundred and Eight © Nils Völker.

2 Exhibited in the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco (2005), the Ars Electronica (2006) and the South Korea Media Art Biennial (2006).

3 Scott Sona Snibbe: http://www.snibbe.com/projects/interactive/blowup/ (last visited: 14.5.2014).

Stefanie Heine

69

In Nils Völker’s One Hundred and Eight4 (ill. 2), an arrangement of plas-tic bags is in- and deflated by micro controlled cooling fans in pre-arranged sequences resulting in several repetitive shapes and formations. The installa-tion reacts to the viewers, aligning the pattern that emerges from the bags’ in- and deflation to their movement in the room. The regular, monotonous pat-tern – the mechanical breathing of an inanimate object – is thus disrupted and assumes a more organic, lively quality. Moreover, viewers get the impres-sion that they contribute to a process of immediate creative sculpturaliza-tion. Even though the breath of the participants is not actually involved, as in Blow Up, One Hundred and Eight invites to reflect the connection between one’s own breathing and the artificial breathing of the plastic bags and the impression of an active inspiration by the viewers is also given. In both installations, one can observe a process of transference: one’s own breath is projected to and externalised in the installation, which visualises breathing patterns in a magnified manner.

Ill. 3: Christa Sommerer and Laurent Mignonneau. Mobile Feelings © Christa Sommerer and Laurent Mignonneau.

4 Exhibited at the B-Seite Festival, Mannheim (2011), the ISEA Istanbul (2011) and the Rewire Festival, The Hague (2011).

Breathing Machines

70

Christa Sommerer’s and Laurent Mignonneau’s Mobile Feelings-project5 (ill. 3) employs small electronic devices passed on between the visitors of the exhibition (or several exhibitions taking place at different venues). Equipped with various sensors, the devices record data of a participant’s heartbeat and breath, for example pulse or breath-temperature. This body-data is then transmitted to another participant’s mobile feeling device by means of visualization and haptic effects: the device vibrates according to the pulse recorded and a micro ventilator emits air corresponding to the air breathed into the sender device. Whereas the relation between the participants and the installation is foregrounded in Blow Up and One Hundred and Eight, Mobile Feelings highlights the relation between the participants who ani-mate the work reciprocally. By yet another process of transferring breath to a technical device and its consecutive transmission to another device, a feeling of intimacy is staged. We do not feel the air exhaled by a living person, but artificial air expelled by a device literally inspired by another visitor, who may be a total stranger.

The probably most complex contemporary breath-installations are cre-ated by the New York-based Korean artist Kimsooja, whose works over the last decades display a strong internal continuity. Throughout her work, Kim-sooja is concerned with practices of weaving and sewing as well as of wrap-ping and bundling. Establishing connections, for example between artworks and viewers as well as between the viewers themselves via artwork, lies at the heart of her artistic endeavours and breathing became one of her favoured motives to actualise these relations. In the Venice Biennale 2013, Kimsooja transformed the Korean Pavilion into a breathing space (ill. 4).6 The venue was completely wrapped with translucent diffraction film that diffused the incoming light into a rainbow spectrum. The mirror-covered floor and ceil-ing reflected the incoming light back and forth perpetually, thus constituting a visualised as well as a metaphorical image of breath: mirrored to and fro in a continual rhythm, light moved between inside and outside like air moves

5 Exhibitions (selection): Ars Electronica (2003), DEAF Dutch Electronic Media Art Festival, Rotterdam (2004), Microwave Media Art Festival, Hong Kong (2004), BEALL Art Center, University of California Irvine (2005), Banquete 05 – Communication in Evolution, Madrid (2005), WIRED NEXT FEST’05, Chicago (2005), STUK Festival, Leuven (2005), ESBALUARD Contemporary Art Museum Palma, Palma de Mallorca (2011).

6 The Korean Pavilion is a direct continuation of two former works by Kimsooja: To Breathe – Respirare (Invisible Mirror/Invisible Needle), Venice (2006) and To Breathe – A Mirror Woman, Madrid (2006-2008).

Stefanie Heine

71

Ill. 4: Kimsooja, To Breathe: Bottari, 2013, mixed media installation, partial instal-lation view of the Korean Pavilion, The 55th Biennale di Venezia, photography by

Jaeho Chong, courtesy of Arts Council Korea and Kimsooja Studio.

Breathing Machines

72

in and out our bodies when we breathe. As a further doubling, one encoun-ters an acoustic actualization of breath: the room is pervaded by the artist’s recorded in- and exhaling. Visitors see the diffracted light mirrored along with their own reflected bodies and hear the artist’s breath, which is exter-nalised, rendered anonymous and seems to merge with the exhibition space itself. The pavilion turns into a breathing room that at the same time mirrors the visitor’s own breathing. Following this space of infinite reflections and mirroring, of visual and auditory connections, the visitors are called to enter a completely dark and anechoic room, in which all exterior sound sources are absorbed, and are thrown back to the mere sound of their own breath. The work as a whole mainly consists in the physical sensations caused by the stark contrast of the light flooded mirror room in which one is bedazzled to the degree that one’s eyes hurt and the absolute darkness in the sound-proof chamber. In the pavilion, the visitors do not so much interact as participate, in the sense that they literally constitute an essential part of the installation as a whole. In the moment when they are in the anechoic chamber, hearing nothing but the sound of their own breathing, the artwork and the viewer seem to coincide radically: the work is nothing but the recipient’s breath – pure self-inspiration, so to speak.

*

I want to suggest that in all these works, the coincidence of their actualization of breath and their participational dimension is not random, as participation coincides with animating the installations, literally inspiring them, breath-ing life into them. In order to investigate the particular role that inspiration assumes in these artworks via articulations of breath and so as to differentiate it from other, earlier conceptions of inspiration, it is helpful to briefly outline some implications of breathing as a figure of thought in Western Culture and to trace breath in art history. Reductive as such an endeavour certainly is, as simplifying matters is unavoidable, it enables to sketch a framework against which the contemporary installations can be set. The Greek word πνεῦμα (pneuma) designates physical breath as well as a transcendent entity, the spirit or soul.7 Especially in the course of Bible translations, these two meanings tend to drift apart.8 In Biblical terms, the immortal breath of God

7 Menge (1913), 561f.8 In the Latin translation, πνεῦμα generally turns into spiritus, which still encom-

passes the same array of meanings. The incorporeal dimension is already increas-

Stefanie Heine

73

(pneuma, or spiritus) animates the world and the (mortal) living creatures inhabiting it. Breath has been associated with inspiration from Antiquity on, which is most prominently manifested in the Latin word inspirare, signifying “breathing in”.9 In Antiquity as well as in the Christian tradition, the notion of animating breath, inspiration, has been transferred to the creation of art or scriptures: creativity is breathed in by an external divine entity and leads the writing hands of the humans who passively act out what is dictated to them.10 The mortal human is thus inspired by an immortal divinity in order to create something that likewise transcends a mortal’s time, e.g. a work of art, or a scripture. Artistic renderings of inspiration reflect how the work of art itself came to be, they tell their own supposed story, so to speak. In contrast to literature, where due to the term alone, inspiration and breath often go hand in hand, Christian iconography mostly draws on other visu-alizations when displaying scenes of inspiration: the writers listening to the voice of God, the dove of the holy ghost sitting by their ear, an angel leading their hand or Christ himself as inspirator.11 As it is usually not seen, breath is hard to represent visually. Scenes of literal inspiration, breathing in, are thus not only rather rare in Christian iconography, but in art history in general.

ingly emphasised in the Latin term (Lutze (1960), 52). In the translations into Germanic languages, where no word with the same range of meanings as pneuma and spiritus exists, this tendency is reinforced: when spiritus is transla-ted as ‘ghost’, for example, it refers to a divine entity or the human’s portion of eternity rather than to the mortal breathing body (ibid., 60). In the New Testa-ment this emphasis is upheld.

9 Greene et al. (2012), 708.10 Ibid. That inspired creators only act passively is not true for all discussions

of inspiration in Antiquity. As Penelope Murray observes, inspiration is not incompatible with a poet’s craft or technique in early Greek literature. The writer depends on the divine inspiration, but is not merely an instrument of it (Murray (2006), 38, 61). Also Renate Schlesier argues that inspiration does not necessarily go hand in hand with passivity in Antiquity. For a very differ-entiated analysis of distinctions between Christian and Classical conceptions of inspiration and the relation between life-giving breath and creativity see Schlesier (2004). Schlesier argues that in the Bible, ‘breathing in’ is not related to artistic creativity (ibid., 183) and that – contrary to common presumptions – numerous Classical authors do not make this connection. This circumstance is worth discussing further, as in the 20th and 21st century, the relation between breathing in and creativity seems to be (re-)established increasingly in art and literature.

11 Kirschbaum (1968), 344f.

Breathing Machines

74

The works that do show inspiration by divine breath tend to highlight it as a force imposed from an external agent. Michelangelo’s Il Sogno, for example, has – amongst other interpretations – been read in terms of inspiration.12 It depicts an angel blowing through a horn directed towards the dreamer’s head. As in the iconographic representations, we have three clearly distin-guishable entities on a visual level: the inspiring angel, located in the realm of the divine, the human dreamer or passive creator and the drawing itself, which could be seen as a result of the inspirational scene it depicts.13

At first sight, it seems as if such a notion of inspiration is inverted in the contemporary breath-installations: that the human being takes the position of the divine inspirator who constitutes the installation as an artwork, which would otherwise only be a mechanical or electronic construct lacking ani-mation. Without being activated by participants, Blow Up would only be a construction of fans, One Hundred and Eight a monotonously moving pile of garbage, Mobile Feelings a number of useless electronic devices and Kim-sooja’s To Breathe: Bottari an empty room – in Kimsooja’s radical formula-tion, articulated by curator Seungduk Kim: “If no one’s there, then there’s nothing.”14 What turns the objects or spaces into works of art is the recipi-ents’ participation; it is the participants who give life to them. In all installa-tions presented, the act of inspiration is related to physical breathing, the air that enters and leaves the participants bodies. Compared to the traditional images, the mode of breath-transference changes: whereas in the scenes of divine inspiration air is transmitted from the divine entity into the human body, the viewer’s breath in the installations is transferred to the artworks in a modified manner or in terms of an externalization. One may assume that inspiration is shifted from a divine force to the human, and from the process of the artwork’s production by the artist to the process of reception. It is tempting to infer that this implies a notion of empowerment, mastery and creative autonomy for a now “emancipated spectator”15 who, in a secularized world, takes the place of the divine force of inspiration on the one hand, and on the other renders the passive executions of the inspired artist active.

12 For a very informed analysis see Ruvoldt (2003). 13 Obviously, this is a simplified reading – one could easily deconstruct these

implications by taking into account the physical manner in which the angel’s body is displayed etc.

14 Kim (2013), 34.15 Cf. Rancière (2011).

Stefanie Heine

75

However this turns out to be illusionary. The inspirational participations enabled by the installations are the results of complex and well-wrought technical constructions. Animating the works is by no means our solitary creative act, it presupposes the digital, mechanical or electronic means designed by the artists. At the moment the participants initiate their inspi-ration, these technical constructs enter a relation of interdependence with their very bodies. In the literal or metaphorical transference from the partic-ipants’ breathing – the air entering and leaving their lungs, noses or mouths, the very air that grants their being alive – to the artificial installation, they coincide with the breathing machine. The installations, especially Blow Up, Mobile Feelings and One Hundred and Eight 16, which literally establish a connection between a human being and a technical apparatus, thus for an instance become cyborg, in the very words of Donna Haraway “hybrid[s] of machine and organism”17. According to Haraway, cyborgs challenge binary oppositions and clear boundaries. In this sense, they share a structural paral-lel with the notion of breath itself: breathing takes place at the very border of the body, as the air we breathe enters the body from the outside and is exhaled again. As a figure of thought, breath is also utterly liminal, located between mind and body, divine and human, life and death. In her “Mani-festo for Cyborgs”, Haraway moreover observes that “[i]t is not clear who makes and who is made in the relation between human and machine”18. In the installations, this indeed becomes undecidable: the technical construc-tions are created by specific humans, but that does not make them works of art. Neither is it only the active participants who create the artwork, as only the technical constructions enable them to do so. The cyborgic break-down of boundaries19 does not only concern the border between human and machine, but also that between creator and creation. In the installations, the status of the humans who momentarily become part of a breathing machine, as well as the status of the artwork is put in to question. Creator, artwork and

16 Kimsooja’s pavilion can only be considered as a machine metaphorically, or in the broadest sense that it is an artificial construction. The way in which the space of the pavilion presents itself to the humans visiting is similar to the posi-tion the machine has in relation to the human according to Haraway: it presents itself as Other, but as an Other which mingles with the human.

17 Haraway (1985), 2269.18 Ibid., 2296.19 Ibid., 2271.

Breathing Machines

76

inspirational source, which are often depicted as three separated instances in iconographic representations, can no longer be clearly distinguished.

The artwork is only constituted as such when it is animated by the partici-pants, which happens not in one single moment, but again and again – there is not one inspirational scene that can be pinpointed. The moment when an artwork is created is hard to designate: it is not the act of designing and man-ufacturing the installation or the elements it consists of, and it is not only the recipients’ participation alone. Hand in hand with this, it is not so easy to point out what the artwork actually consists in, what it is. At best, one could say that it is the moment when a relation between the installation as a phys-ical entity and the humans who engage with it is established. Only then can we call Snibbe’s and Völker’s constructions, Sommerer’s and Mignonneau’s technical devices, or Kimsooja’s architectural spaces works of art. Conse-quently, the artworks are not so much manifested objects as momentary emergences, taking place in the course of a fleeting touch. We are faced with artworks whose very existence as artworks is continually put at risk: they are themselves transient because the moments of touch between participants and work pass by. One could argue that regarding the installations, the con-notations of transcendence and eternity going along with the Greek pneuma are reunited with the word’s reference to physical (and thus mortal) breath in a transformed manner. The many different visitors revitalise the works again and again, but the fact that visitors come and go exposes the works to a con-tinuing break threatening their very existence: the moment the contact with a visitor breaks, the artwork ceases to be. It is continually put in question and dependent on each recipient to engage with it.

The relation to the recipients is a fragile one – it depends on multiple factors that come together in one specific moment: is the recipient present, willing and able to participate, and if so, is the participation successful? It is easy to imagine that visitors do not feel like blowing into the input device of Blow Up, or that they do not step closely enough towards One Hundred and Eight to make it react. Visitors of an exhibition may not know what to do with a Mobile Feeling-device. It is also well imaginable that the technical con-structions fail or wear out. Before you enter the Korean Pavilion in Venice, you have to sign a paper declaring that you don’t suffer from claustrophobia, panic disorder, tachycardia, dizziness or epilepsy, so some people are from the start prohibited from participating for health reasons. Then, many vis-itors, having entered the pavilion and taken a walk around the rather small room and having observed the changing formations of the rainbow spectrum for a while, seem to end up being unsure of what to do. In the rather long

Stefanie Heine

77

time span they have to wait until they are admitted to the anechoic chamber, the connection to the artwork may be broken. The recipients, and with it, the artwork, becomes subject to exhaustion: some visitors just sit and wait or take a rest, some check their make-up in the mirrors, some take photographs and some start to engage in meditation practices. In other words, they no longer participate directly in an artistic installation, or become unaware that they may even be doing so by the other activities or non-activities they exert. The effect of the anechoic chamber can easily be destroyed if people start to talk or make noises, or you may panic. In sum, there is a constant danger that the participants for some reason may not participate in the installations discussed. The works are thus all but autonomous or intransient and their mortal inspirator-recipients do not act as self-determined creators.

The artworks’ precarious state is as such highlighted by what they the-matically and materially relate to, namely breathing. As already mentioned, breath is not only associated with a vitalising force, but also with death, tran-sience and mortality. Dying is ceasing to breathe. All installations discussed involve air, which as an invisible, evaporating substance as such evokes fleet-ingness and dissolving. The works present breath in a visualised manner or in the form of sound waves, as something than can be perceived with the bodily senses. The physical, sensible qualities of breath and air are rendered productive as basic materials of these works that involve the participants’ bodies. This combination, along with the interdependence of the works and the humans, results in a threefold highlighting of transience: first, as already discussed, the dependence on interaction with participants renders the status of the artwork as artwork precarious. Second, the human body the works depend on is mortal and vulnerable. This is explicitly addressed in Kimsooja’s case where visitors are warned that the installation may pose a bodily risk. The paper you have to sign before visiting the pavilion ends with the sentence “The decision to enter is each individual’s personal responsibility”, which reminds of the assumption risk agreements and medical statements one has to sign before engaging in a potentially dangerous activity. Moreover, in the pavilion we hear the artist’s recorded breathing accelerating to the point of breathlessness and exhaustion, thus pointing to a body’s weakness. The mir-ror room causes sensory overload, the diffracted and reflected light is almost too much for the eyes to take. Thus, the visitor’s body is itself brought to the limit of exhaustion.20 Third, the fact that the installations are used and

20 On the relation of inspiration, inexhaustibility and the annihilation of the inspired human being see Blanchot (1982a), 181.

Breathing Machines

78

handled physically makes them subject to wastage. The interior of Kimsooja’s pavilion showed signs of use already one month before the exhibition closed: the mirrors were partly dent and murky and the diffraction granting film started to peel away in some places. One Hundred and Eight addresses mate-rial wearout explicitly, as it consists of plastic bags, objects that are made to dispose of waste. It seems to be no coincidence that all of these works are part of temporary exhibitions – they are deliberately designed to last only over a certain limited period of time. Breathing artworks are bodily artworks – artworks giving the impression that they may also cease to breathe and consequently appear to be mortal. The works in turn bring us in touch with decomposition, that is, they create a touch with what is Other to our func-tioning living bodies.

*

At this point, I want to turn back to the notion of inspiration. Inspiration can be considered as an articulation of the Other in one’s body, or, in the case of the installations discussed, as an articulation of one’s body in the Other, the machine. Maurice Blanchot’s approach to inspiration in The Space of Lit-erature (French original 1955) offers a way to carry forward the discussion of the installations’ precarious state along with the articulation of an alterity through breathing. For Blanchot, inspiration always involves a leap – a leap in into uncertainty, a suspended breath of which we do not know whether it brings life or marks its end. It is what potentially lets an artwork emerge, but at the same time implies the risk of its decomposition. In Blanchot’s reading of Orpheus and Eurydice, Orpheus descends to the underworld towards “the furthest that art can reach”21 which is embodied by Eurydice. In order to create a work of art, Orpheus has to face the other night, a space which is radically Other to the world, where nothing is but absence. The intention to ascend again, to give form and shape to what he encountered in the under-world by creating an artwork, is endangered in the moment he encounters Eurydice who coincides with the other night. He “forgets the work he is to achieve”22 and is on the brink of losing himself in the void of the other night. Blanchot points out that precisely this moment of facing the abyss, of for-getting to create an artwork in the fatal look back at Eurydice is Orpheus’s

21 Blanchot (1982b), 171.22 Ibid.

Stefanie Heine

79

“inspired movement”23. Inspiration – life-giving breath – is reread by Blan-chot as apnea, as suspension of breath, that is, a moment in which (the) life (of the work) teeters on the brink: “Inspiration pronounces Orpheus’s ruin […] and it does not promise, as a compensation, the work’s success.”24 On the contrary, the work reaches “its point of extreme uncertainty” through Orpheus’s inspired look.25 For Blanchot, it is precisely this uncertainty, the moment in which it is not granted that the next breath sets in again, which makes the work possible. The work, which makes its own demands, pushes the artist away from its own realization; it pushes him “to make of the work a road to inspiration […] and not of inspiration a road to the work.”26 So in con-trast to the thought that inspiration leads to an accomplished work, inspira-tion in Blanchot’s sense at the same time constitutes the work and endangers it, exposing it to a continual unworking.

When Blanchot addresses inspiration, he is concerned with the produc-tion of artworks rather than with their reception. However, shifting the focus from the creator of the work to the recipient, his thoughts on inspiration can be extended and offer a fruitful model to investigate reception, especially in the case of the breath-installations discussed. The installations deliberately create a situation in which recipients find themselves in a position compara-ble to the one of Orpheus as Blanchot describes it and they display “a road to inspiration”. A simplified conception, dismissed by Blanchot in his nego-tiation of the term, would suggest a linear process in which inspiration has a clearly defined place: the inspired artist creates an accomplished work that is then viewed. In the installations, inspiration does not mark a beginning in a chronological timeline; rather, inspiration is scattered and the role of the artist spreads to the recipient. Moreover, staging the Classical concept literally as ‘breathing into’, the installations perform “a road to inspiration”: they are constituted by continually being animated by participants, that is, by the ones who encounter them after they have been ‘created’ by the artists. As already discussed, this continual inspiration in the reception process at the same time perpetually renders the artworks’ existence as artworks uncer-tain. Even though all installations can be considered in terms of inspiration as “the work’s uncertainty”, Kimsooja’s pavilion can be read more particularly in Blanchot’s terms, which I am going to do in the following.

23 Ibid., 172.24 Ibid., 174.25 Ibid.26 Blanchot (1982a), 186.

Breathing Machines

80

What does Orpheus want, when he descends to the underworld? He does not want the Eurydice of the day, is not interested in the visible woman, but in the moment when she is invisible and obscure, present in her absence. At first, Kimsooja’s room of mirrors seems to be what Orpheus turns away from: it is a space of hyper-visibility, day as bright and lucid as it can be. In the room, everything is visible, including things that are commonly invisible: white light, usually unseen, is made perceptible by its diffraction into bright, spectral colours. The mirrors make the visitors visible, who see themselves in the artwork – whereas in most other cases, one looks at an artwork and is unaware of the part one has in it. The mirrors also mirror themselves, so the mirror as a medium becomes visible, another thing, which generally goes unnoticed. On another sensual level, we hear the recorded breath. Breath also belongs to the things that happen without being perceived consciously. As the title of the installation, To Breathe: Bottari and the continual audi-tory background in the mirror room suggest, breath functions as the instal-lation’s undertone or basic motive. Taking into account the link between breath and inspiration as the original moment of the work, as the way in which it comes to be, the different elements of the installation can be con-nected. Everything in the room points to that which makes the artwork and the images it produces possible: firstly, light, which is an important factor for seeing something at all, is highlighted. Second, we see ourselves. Besides owning the organs that make seeing possible, it has already be stressed that the visitors are an essential part of the installation as such. Third, the instal-lation would not work without mediation, which is rendered visible through the mirrors mirroring themselves. The installation enacts its own emergence and constituents and puts its self-reflexivity on display. In a nutshell, it can be considered as an extended image for inspiration as a moment of origin, of that which constitutes the work as work. Rather than resulting in an accom-plished whole, however, the mirror room seems to decompose into its own components.

On closer consideration, it does not stand in contrast to what Orpheus faces in the underworld, but rather displays one facet of the other night. Blanchot observes that when “[i]nspiration pushes us gently or impetuously out of the world”, we may encounter “within concentrated night a passive, obedient light […] paralyzed lucidity. The power that fascinates has come into contact with this point, which it touches in the separated place where everything becomes image.”27 Kimsooja’s space of total visibility indeed

27 Ibid., 185.

Stefanie Heine

81

causes an effect of paralysis: visitors are exposed to radical disorientation as the boundaries between inside and outside, and above and below blur. Even though it seems like the most imaginable contrast to the anechoic chamber, the transition is fluent: we move from one kind of disorientation to another and from one kind of present absence into another. When entering the anechoic chamber, negative afterimages of the dazzling light in the mirror room are produced and the room itself seems to function like these after-images: it is the mirror room’s inverse. One is disoriented and encounters a presence of absence because one does not see anything. Instead of hear-ing recorded breath, visitors start to faintly hear their own breath. Reflected mediation turns to immediacy: what has been displayed next to each other metonymically, resulting in visible images of inspiration, collapses in the bodies of the visitors, their breathing. In the anechoic chamber, one’s own breathing is only heard after a while, and even then, it is only heard dimly. At first, you are not even sure that it is your own breath you hear. This sen-sation has striking parallels to a moment Blanchot pinpoints in the other night, when one hears a “muffled whispering, a noise one can hardly distin-guish from silence […]. Not even that. Only the sound of some activity […] – at first intermittent, but once perceived, it won’t go away.”28 As Blanchot points out, hearing the seemingly foreign muttering sound turns out be hear-ing oneself29 and “it is intimacy that becomes menacing foreignness”30. Like Orpheus’s look back to Eurydice, hearing the air entering and leaving one’s body is “a critical moment”31. Whereas in the first case, Orpheus’s wife, the woman he knows, appears distant and turns into “nocturnal obscurity”32, in the second case it is a process of our own bodies that appears foreign.33 We

28 Blanchot (1982c), 168.29 Ibid., 169.30 Ibid., 168.31 Blanchot (1982b), 173.32 Ibid., 172.33 Here, one can discern a difference between the mirror room and de anechoic

chamber in terms of the way in which an Other is conceived: whereas in the mirror room, we are confronted with a reconciliation between self and Other in the sense of Haraway’s notion of the cyborg, where human and machine merge (we merge with the space), the anechoic chamber opens to an encounter to the Other as radical alterity. Other than the machine, the mirror room or recorded breath, which are Other in the sense of being different form the human and external to it, the effect of radical alterity in this case is evoked by the internal being perceived as external.

Breathing Machines

82

hear our breath as if it were something external, a disembodied sound like the one we heard in the mirror room. Besides its uncanniness, this experience is what constitutes the artwork at this very moment. At this point, we are all but active – to the contrary, all we do is breathe, which is the most min-imal action one can imagine. Minimal as it is, the act of breathing is all but insignificant: it marks the thin line that separates life and death. Kimsooja addresses this in an interview about her pavilion in Venice:

I see breathing as the moment of life and death – just one moment when life ends, just one moment when you are living. Breathing is another kind of fabric – another way of weaving and sewing –34 another way of connecting life and death and awareness of my body as both a physicality and impermanency.35

By leading attention to mere breath, and in Blanchot’s words engaging us in a passive “movement outside tasks”36, the work also leads attention to its own fragile state of existence on the brink. For Blanchot, the work’s initiative, or rather original moment, is always a moment of “standstill” a “state of sus-pense when inspiration has the same countenance as sterility”37.

Kimsooja’s installation in particular, but also the other breathing instal-lations discussed, seem to highlight such a conception of art. In these cases, participation does not coincide with inter-action, even though recipients play a constitutive role. Contrary to self-determined, intentional and empow-ered actions of the recipients, the relation between work and recipients in the installations discussed is one of interdependence, which can never be fully guaranteed. The works are neither produced nor completed by the reci-pients – which would imply that their status was secured: there would be an accomplished artwork as a result. As already discussed, such a state is never achieved – the works only emerge temporarily in a fleeting and fragile trans-ference of breath and perpetuate the precarious moment of inspiration in Blanchot’s sense.

34 Kimsooja alludes to her references to and work with textiles, for example the practice of bundling and weaving, throughout her art projects. The title of the Korean Pavilion, To Breathe: Bottari points to this, as ‘bottari’ “is the result of rolling up pieces of fabric in bundles.” Kim (2013), 35.

35 Kimsooja (2009), 144.36 Blanchot (1982a), 182.37 Ibid.

Stefanie Heine

83

References

Maurice Blanchot. “Inspiration, Lack of Inspiration”. The Space of Literature. Lin-coln, London: University of Nebraska Press, 1982a. 177-187.

Maurice Blanchot. “Orpheus’s Gaze”. The Space of Literature. Lincoln, London: Uni-versity of Nebraska Press, 1982b. 171-176.

Maurice Blanchot. “The Outside, the Night”. The Space of Literature. Lincoln, Lon-don: University of Nebraska Press, 1982c. 163-170.

Roland Greene et al. (Eds., 2012). The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Donna Haraway (1985). “A Manifesto for Cyborgs: Science, Technology, and Socialist Feminism in the 1980s”. The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism. Eds. Vincent B. Leitch et al. New York, London: W. W. Norton & Company, 2001. 2269- 2299.

Seungduk Kim. “Centripetal Acceleration”. The Korean Pavilion. Kimsooja. To Breathe: Bottari. 55th International Art Exhibition. La Biennale di Venezia 2013. Eds. Seungduk Kim/Franck Gautherot. Città di Castello: Les presses du reel, 2013. 33-37.

Kimsooja (2013). To Breathe: Bottari. Venice Biennale. Kimsooja. Art: 21. Art in the Twenty-First Century. Volume 5, 2009. 132-145. Engelbert Kirschbaum (Ed., 1968). Lexikon der christlichen Ikonographie. Zweiter

Band. Freiburg i.B.: Herder, 2012. Ernst Lutze (1960). Die Germanischen Übersetzungen von Spiritus und Pneuma.

Ein Beitrag zur Frühgeschichte des Wortes “Geist”. Bonn: Rheinische Friedrich Wilhelms-Universität.

Hermann Menge (1913). Langenscheidts Grosswörterbuch Griechisch. Teil I. Griech-isch – Deutsch. Berlin, München, Zürich: Langenscheidt, 1967.

Laurent Mignonneau/Christa Sommerer (2004-2011). Mobile Feelings. Exhibited at various venues.

Penelope Murray. “Poetic Inspiration in Early Greece”. Oxford Readings in Ancient Lit-erary Criticism. Ed. Andrew Laird. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006. 37-61.

Jaques Rancière (2011). The Emancipated Spectator. London, New York: Verso.Maria Ruvoldt. “Michelangelo’s Dream”. The Art Bulletin Vol. 85, No. 1 (Mar.,

2003): 86-113.Renate Schlesier. “Künstlerische Kreation und Religiöse Erfahrung. Verwendungs-

geschichtliche Anmerkungen zum Begriff der Inspiration”. Ästhetische Erfahrung im Zeichen der Entgrenzung der Künste. Epistemische, ästhetische und religiöse Formen von Erfahrungen im Vergleich. Sonderheft des Jahrgangs 2004 der Zeitschrift für Ästhetik und Allgemeine Kunstwissenschaft. Ed. Gert Mattenklott. Hamburg: Felix Meiner, 2004. 177-194.

Scott Sona Snibbe (2005-2006). Blow Up. Exhibited at various venues.Nils Völker (2011). One Hundred and Eight. Exhibited at various venues.

Breathing Machines