Biehl P. & Yu. Rassamakin (eds), 2008. Import and Imitation in Archaeology Schriften des ZAKS, 11,...

Transcript of Biehl P. & Yu. Rassamakin (eds), 2008. Import and Imitation in Archaeology Schriften des ZAKS, 11,...

SCHRIFTEN DES ZENTRUMS FÜR ARCHÄOLOGIE UND KULTURGESCHICHTE DES SCHWARZMEERRAUMES 11

IMPORT AND IMITATION

IN ARCHAEOLOGY

SCHRIFTEN DES ZENTRUMS FÜR ARCHÄOLOGIE UND

KULTURGESCHICHTE DES SCHWARZMEERRAUMES

Herausgegeben von

FRANÇOIS BERTEMES und ANDREAS FURTWÄNGLER

IMPORT AND IMITATION

IN ARCHAEOLOGY

EDITED BY

P. F. BIEHL & Y. YA. RASSAMAKIN

Beier & BeranLangenweißbach 2008

Es ist nicht gestattet, diese Arbeit ohne Zustimmung von Verlag, Herausgebern oder Autoren vollständig oder aus-zugsweise nachzudrucken, zu kopieren oder auf sonst irgendeine Art zu vervielfältigen!

Bibliographische Information der Deutschen NationalbibliothekDie Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation

in der Deutschen Nationalbibliographie; detaillierte bibliographischeDaten sind im Internet über <http://dnb.ddb.de> abrufbar.

Gedruckt mit freundlicher Unterstützung der Alexander von Humboldt-Stiftung. Printed with the financial support of the Alexander von Humboldt-Stiftung.

Verlag/Publisher: Beier & Beran. Archäologische Fachliteratur Thomas-Müntzer-Str. 103, D-08134 Langenweißbach Tel. 037603 / 3688, Fax 037603 / 3690 Internet: www.beier-beran.de, E-mail: [email protected]

Wissenschaftliche Redaktion/Editing: Peter F. Biehl und Daniela FrehseRedaktion der englischsprachigen Beiträge/English copy editing: Ben Roberts Redaktion der ukrainischen Zusammen-fassungen/Ukrainian translations: Yuri Ya. RassamakinGraphische Gestaltung/Graphic design: Jordan Kanew Layout/Publisher: Daniela FrehseDruck/Print: Verlag Beier & BeranHerstellung/Production: Buchbinderei Reinhardt Weidenweg 17, D-06120 Halle / Sa.

C: Copyright und V. i. S. d. P. für den Inhalt liegt bei den Autoren.

ISBN 978-3-937517-95-7

Gedruckt auf alterungsbeständigem Papier.Hergestellt in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland / printed in Germany.

Cover figure: Anthropomorphic Clay Figurine from Vrsac (after cover figure: G. Schumacher-Matthäus, Studien zu Bronzezeitlichen Schmucktrachten im Karpatenbecken. Ein Beitrag zur Deutung der Hortfunde im Karpatenbecken (Mainz 1985), after F. Milleker, Starinar 3, Ser. 2, 1923, Taf. 1)

S. Hansen:Preface

P. F. Biehl & Y. Ya. Rassamakin:Import and Imitation in Archaeology. An Introduction

A. Choyke:Shifting Meaning and Value through Imitation in the European Late Neolithic

J. Czebreszuk & M. Szmyt:What Lies behind ‘Import’ and ‘Imitation’? Case Studies from the European Late Neo-lithic

T. Tkachuk:Ceramic Imports and Imitations in Trypillia Culture at the End of Period CI - Period CII (3900 - 3300 BC)

Y. Ya. Rassamakin & A. Nikolova:Carpathian Imports and Imitations in Context of the Eneolithic and Early Bronze Age of the Black Sea Steppe Area

A. A. Bauer:Import, Imitation, or Communication? Pottery Style, Technology and Coastal Contact in the Early Bronze Age Black Sea

P. F. Biehl:‘Import’, ‘Imitation’ or ‘Communication’? Figurines from the Lower Danube and Mycenae

Contents

G. J. van Wijngaarden:The Relevance of Authenticity. Mycenaean-Type Pottery in the Mediterranean

A. Mª Lucena Martín:Things We Have, Things We Lack: Reconsidering the First Contacts Between Aegean and the Central and West Medi-terranean

S. Makhortykh:About the Question of Cimmerian Imports and Imitations in Central Europe

H. Potrebica:Contacts Between Greece and Pannonia in the Early Iron Age - With Special Concern to the Area of Thessalonica

M. Carucci:The Sette Sale Domus. A Proposal of Reading

A. Kaliff:The Goths and Scandinavia. Contacts Between Scandinavia, the Southern Baltic Coast and the Black Sea Area During the Early Iron Age and Roman Period

N. Wicker:Import and Imitation in the Migration Period

List of Authors and Addresses

1

2

5

23

35

51

89

105

125

147

167

187

213

223

243

253

Import and imitation have been in archaeological vocabulary since the 19th century and many archae-ologists still use these terms when describing simi-larities of material culture in different archaeological “cultures“.

Generally import and imitation as concepts have been used to build up chronological frame-works in Europe and Eurasia by connecting regional relative chronologies. One major problem in German archaeology in the 1960s was the question of how fast Roman imports reached the northern Germanic regions.

The method of cross dating by “imports“ and “imitations“ in earlier prehistoric periods was revealed in many cases to be flawed after employ-ment of calibrated radiocarbon dates. Especially in the Neolithic and the Copper Age completely new pictures of contemporaneous “cultures“ emerged and are still being developed. Surprisingly we again find in this new chronological framework “imports“ and “imitations“ in cultures whose contemporaneousness we didn’t even consider some years ago.

Hence it is necessary to differentiate forms of imitation of material culture as well as to specify “importing“ as a metaphor for the different forms of exchange of goods.

The growing interest in the humanities in ma-terial culture and the semiotics of things open new perspectives on the topic. Igor Kopytoff’s notion of the cultural biographies of things leads to the dif-ferentiation of several overlapping functions during the lifetime of an object. The meaning and function of objects depended on certain cultural contacts and may have changed in space and time.

The editor’s collection of papers given in EAA meetings in Thessaloniki and St. Petersburg is a wel-come contribution to the widening perspective on foreign objects. The variety of contributions from the Neolithic to the Migration Period and from the Black Sea to the Baltic Sea should be taken as an excellent chance by specialists to read case studies from other regions and periods outside of their own specialization.

!"#$%&' &( )")&(*)+ ,’-.'/'0- . (%12$/$3)45)6 /270'*) . 8!8 0&$%)44), ) 9(3(&$ (%12$/$3). :2 6 ,(%(, .'7$%'0&$.;<&= *) &2%")5', $#'0;<4' 01$>)0&= "(&2%)(/=5$+ 7;/=&;%' . %),5'1 (%12$/$3)45'1 «7;/=&;%(1».

? $05$.5$";, )"#$%&' &( )")&(*)+ 7$5*2#&;(/=5$ .'7$%'0&$.;.(/'0- @/- %$,%$97' 1%$5$/$3)+ A.%$#' &( A.%(,)+, #%' #$9;@$.) %23)$5(/=5'1 .)@5$05'1 1%$5$/$3)45'1 012". B/- #%'7/(@;, $@5)C< , 5(69)/=D'1 #%$9/2" . 5)"2*=7)6 (%12$/$3)+ ; 60-1 %$7(1 88 0&$%)44- 9;/$ #'&(55-, 5(07)/=7' D.'@7$ %'"0=7) )"#$%&' @$0-3(/' #).5)45'1 32%"(50=7'1 %23)$5)..

?)@5$05$ @(&;.(55- «)"#$%&).» &( «)")&(*)6» . %(55)6 #%()0&$%)+ . 9(3(&=$1 .'#(@7(1 .'5'7/' 0;"5).' #)0/- .'7$%'0&(55- %(@)$.;3/2*2.'1 @(&. E$7%2"(, . 52$/)&) &( 252$/)&) .'5'7/( #$.5)0&< 5$.( 7(%&'5( 0'51%$5),(*)+ «7;/=&;%», -7( ) @$0) :2 ,5(1$@'&=0- . #%$*20) %$,.'&7;. B'.$.'>5$, (/2 "' ,5$.; ,5(1$@'"$ 5$.) 1%$5$/$3)45) 012"' «)"#$%&).» &( «)")&(*)6» . 7;/=&;%(1, -7) "' ..(>(/' 520'51%$55'"' :2 @27)/=7( %$7). &$";.F2$91)@5$ %$,%),5-&' G$%"' )")&(*)+ #%2@"2&). "(&2%)(/=5$+ 7;/=&;%', ( &(7$> &$45$ .',5(4(&' «)"#$%&'», -7 "2&(G$%; @/- %),5'1 #%$-.). $9")5; %2426.

E%$0&(<4( ,(*)7(./25)0&= ; .',5(4255) #%'%$@' "(&2%)(/=5$+ 7;/=&;%' &( 02")$&'7' %2426 .)@7%'.(<&= 5$.) #2%0#27&'.' . *)6 $9/(0&) #),5(55-. B;"7( !. H$#'&$GG( #%$ 7;/=&;%5) 9)$3%(G)++ %2426 @$,.$/-C @'G2%25*)<.(&' $7%2") 4(0&7$.$ 0#).#(@(<4) G;57*)+ .#%$@$.> >'&&- $9’C7&;. E5(4255- &( G;57*)- $9’C7&). ,(/2>'&= .)@ #2.5'1 7;/=&;%5'1 7$5&(7&). ) "$>;&= ,")5<.(&'0- ; #%$0&$%) &( 4(0).

I&(&&), ,)9%(5) %2@(7&$%("' . @(5)6 ,9)%*), ) -7) 9;/' #$#2%2@5=$ $,.;425) 5( 7$5G2%25*)-1 A.%$#260=7$+ J0$*)(*)+ J%12$/$3). . I(/$5)7(1 &( I(57&-K2&2%9;%,), C .(>/'.'" .5207$" @$ %$,D'%255- #2%0#27&'. ; .'.4255) #%$9/2"' )"#$%&). &( )")&(*)6. L),5$"(5)&5)0&= 0&(&26, -7) $1$#/<<&= 4(0 .)@ 52$/)&; @$ #2%)$@; ")3%(*)6, &( &2%'&$%)< .)@ M$%5$3$ @$ N(/&)60=7$3$ "$%)., 5(@(C ,%;45'6 D(50 G(1).*-" #$,5(6$"'&'0- , @$0/)@>255-"' , %),5'1 %23)$5). &( #2%)$@)..

Preface

S. Hansen

Import and Imitation in ArchaeologyAn Introduction

The book „Import and Imitation in Archaeology“ arose from two symposia organized by the editors at the meetings of the European Association of Archaeologists (EAA) in Thessaloniki (2002) and St. Petersburg (2003). In it authors from across Europe discuss and illustrate with case studies from a wide range of geographical regions and time periods the archaeological key concepts of ‘import’ and ‘imitation’ from a variety of theoretical and methodological perspectives.

The geographical focus lies in East and South-east Europe as well as in the eastern Aegean and the wider Black Sea Region. Chronologically, there are three emphases among the contributions: (1) Neolithic, Copper Age and Early Bronze Age (Choyke, Czebreszuk/Szmyt, Tkachuk, Rassamakin/Nikolova, Bauer), (2) Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age (Biehl, van Wijngaarden, Lucena Martin, Makhortykh, Potrebica), and (3) the protohistoric periods (Carucci, Kaliff, Wicker).

The book has two main objectives: firstly, to publish new archaeological data, especially from eastern Europe and make it accessible for a wider, mainly western research community (Choyke, Tkachuk, Rassamakin/Nikolova and Bauer). And secondly, to open up a debate and theorize the concepts of import and imitation in archaeology, both with scrutinizing their applications in modern archaeology as well as to better understand the epistemological – the comparative analysis of these concepts in western and eastern European research traditions – and methodological issues involved – ranging from the so called ‘import chronology’, which has been especially influential in culture-historical approaches, to agency-based approaches in post-processual archaeology.

Therefore, the contributions in this book mirror the general paradigm shift in modern archaeology from the concepts of ‘invention’ and ‘innovation’ – including the underlying models of migration or diffusion – to concepts ranging from culture change, contact and transfer to reception/adaptation and import/export – using models such as

centre and periphery, trade and exchange, style and interaction/communication. Other theoretical issues discussed in this volume include authenticity, identity and agency and their meaningfulness for identifying imported or imitated material culture. The basic prerequisite for this paradigm shift and debate is that we acknowledge that material culture is meaningfully constituted and that it plays an active role in the social reproduction of all human behavior and relations. In the end, the book tries to conceptualize the material engagement of both the ‘importing and/or imitating’ and ‘exporting’ individuals or groups, in order to come closer to an understanding of the entanglement of objects and people in the past.

As in any project, we, as editors, owe great thanks to the people who helped make this book possible. We gratefully acknowledge and deeply appreciate the dedicated efforts of each of the authors who undertook to write up their conference papers and who willingly agreed to guide their writings through several stages of editing. We would also like to thank the editors of the Publication Series of the Centre for Black Sea Archaeology (Zentrum für Archäologie und Kulturgeschichte des Schwarzmeerraumes - ZAKS) François Bertemes and Andreas Furtwängler for including this book in the series. Thanks are also due to the Institute of Prehistoric Archaeology at the Martin-Luther-University Halle-Wittenberg for the logistic and technical support. Here we owe a deep dept of thanks to Jordan Kanew for the digital image editing, and especially to Daniela Frehse for the meticulous copyediting, layout and the production of the printer’s copy, which contributed in an essential and significant way to this volume. We would also like to thank Ben Roberts from the University of Cambridge for the diligent copyediting and thorough English language editing. Thanks are also due to our publisher Hans-Jürgen Beier who agreed to take on this project and encouraged it to completion.

And finally, deep gratitude is especially owed to the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation in Bonn for financing the book.

Halle in October 2007

Peter F. Biehl & Yuri Ya. Rassamakin

K2%2@"$.(

E9)%7( «!"#$%&' &( )")&(*)+ . (%12$/$3)+» ")0&'&= 0&(&&), #)@3$&$./25) 5( $05$.) @$#$.)@26, -7) 9;/' #%$4'&(5) 5( @.$1 7$5G2%25*)-1 A.%$#260=7$+ J0$*)(*)+ J%12$/$3). . I(/$5)7(1 (2002) &( I(57&-K2&2%9;%,) (2003) . "2>(1 %$9$&' $7%2"'1 027*)6, $%3(5),$.(5'1 %2@(7&$%("' *)C+ ,9)%7'. B/- %$,3/-@; $,5(425$+ &2"' %2@(7&$%' ,9)%7' ,(#%$0'/' G(1).*). , %),5'1 7%(+5 0.)&;, -7) $93$.$%'/' *<, $@5; , 7/<4$.'1 #%$9/2" . (%12$/$3)+, .'1$@-4' , &2$%2&'7$-"2&$@$/$3)45'1, 32$3%(G)45'1 &( 1%$5$/$3)45'1 #%'5*'#)., 0;#%$.$@>;<4' @'07;0)< D'%$7'" 0#27&%$" (%12$/$3)45'1 #%'7/(@)..O2$3%(G)45$, @$0/)@>255- $1$#/<<&= &2%'&$%)< I1)@5$+ &( K).@255$-I1)@5$+ A.%$#', , $0$9/'.'" 5(3$/$0$" 5( $9/(0&) K%'4$%5$"$%’- &( I1)@5$+ P32+@'. 8%$5$/$3)45$ 0&(&&) "$>5( %$,@)/'&' 5( &%' .2/'7) #)@%$,@)/': (1) 52$/)&, 252$/)& ) %(55)6 #2%)$@ @$9' 9%$5,' (M$67), M29%2D;7/Q"'&, R7(4;7, F)7$/$.(/L(00("(7)5, N(;2%); (2) #),5)6 #2%)$@ @$9' 9%$5,' &( @$9( %(55=$3$ ,(/),( (N)/=, .(5 ?'653((%@25, S;*25( T(%&)5, T(1$%&'1, K$&%29)*() ) (3) 5(69)/=D #),5)6, -7'6 #%2@0&(./25'6 ;>2 %(55=$)0&$%'45'" 4(0$" (H(%;44), H(/)GG, ?)72%).

K$%-@ , 5$.'"' (%12$/$3)45'"' "(&2%)(/("', (53/$"$.5( #;9/)7(*)- -7'1 0&(52 @$0&;#5$< 9)/=D D'%$7$"; 7$/; 4'&(4). (M$67), R7(4;7, F)7$/$.(/L(00("(7)5, N(;2%, H(%;44), ?)72%), $05$.5( ;.(3( ,9)%7' 0#%-"$.(5( 5( &2$%2&'452 .',5(4255- $05$.5'1 7$5*2#*)6 ; .'.4255) )"#$%&). &( )")&(*)6 . #2%.)05)6 &( %(55=$)0&$%'45)6 (%12$/$3)+. H%)" 7%'&'45'1 #)@1$@). @$ &(7 ,.(5$+ 1%$5$/$3)+ ,( )"#$%&("', .(>/'.'" .5207$" @/- $9%(5$+ &2"' C @$0/)@>255- , %),5'" %$,;")55-" ) .'7$%'0&(55-" *)C+ 7$5*2#*)+ ; ,(1)@5)6 &( 01)@5$C.%$#260=7)6 5(;7$.)6 &%(@'*)+.

E( ,(@;"$" %2@(7&$%)., . 0&(&&-1 #$.'55) 9;&' %$,3/-5;&) 52 &)/=7' 7(&23$%)+ «.'5(1)@» &( «)5$.(*)-», (/2 6, .'1$@-4' , %$,;")5- &(7'1 #$

5-&=, -7 ")3%(*)-, @'G;,)- &( .,(C"$@)-, 9;@;&= @'07;&;.(&'0- &(7$> &(7) &2"', -7 5(#%'7/(@, 7;/=&;%5) 7$5&(7&' ) 7;/=&;%5( &%(50G$%"(*)-, *25&% ) #2%'G2%)-, &$%3)./- ) $9")5, ,(0&)6 ) 7$";5)7(*)-, $&%'"(55- ) 270#$%&;.(55- (9$ > (;&25&'45)0&=. H%)" &$3$, . 0&(&&-1 9;@;&= %$,/-@(&'0- -7 #'&(55- )@25&'45$0&) &( )5@'.)@;(/=5$0&) ) +1 #%$-. . "(&2%)(/=5)6 7;/=&;%), &(7 ) $05$.5) #%$9/2"' 0'".$/)45$3$ ,5(4255- "(&2%)(/=5$+ 7;/=&;%'. F(%2D&), . *)6 75',) %$,3/-@(&'"2&=0- #'&(55- 0$*)(/=5$3$ ,5(4255- 7;/=&;%5'1 7$5&(7&). ) 7;/=&;%5'1 &%(50G$%"(*)6 @/- «)"#$%&;<4$3$/)")&;<4$3$», ( &(7$> «270#$%&;<4$3$» 0;0#)/=0&.(.

F( ,(7)54255-, "' 1$&)/' 9 .'0/$.'&' :'%; #$@-7; %2@(7&$%(" «B$0/)@>25= *25&%; (%12$/$3)45'1 @$0/)@>25= ) )0&$%)+ 7;/=&;%' 4$%5$"$%0=7$3$ %23)$5;» (Schriften des Zen-trums für Archäologie und Kulturgeschichte des Schwarzmeerraumes, ZAKS) U. N2%&2"20; &( J. U;%&.253/2%; ,( +1 /<9’-,5; ,3$@; $#;9/)7;.(&' 5(D; 75'3; . @(5$"; &$") *=$3$ 02%)65$3$ .'@(55-. R(7$> "' .@-45) .029)45)6 #)@&%'"*) !50&'&;&; #2%.)05$+ (%12$/$3)+ T(%&)5-S<&2%( ;5).2%0'&2&; 8(//2-?)&&2592%3 (Institut für Prähis-torische Archäologie der Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg) #%' #)@3$&$.*) 75'3' @$ @%;7;. F(D( $7%2"( #$@-7( V. H(52.; ,( *'G%$.; $9%$97; )/<0&%(*)6 ) B. U%2,2 ,( %2@(7*)652 $#)7;.(55- ) #)@3$&$.7; &270&; @$ @%;7;. E( 7%'&'45'6 $3/-@ (53/$"$.5$3$ %;7$#'0; &( %2,<"2 "' @;>2 .@-45) N. L$92%&0; (H2"9%)@>0=7'6 ;5).2%0'&2&). W7%2"( #$@-7( O.-X. N2C%; ,( 6$3$ #%$G20)65; .'@(.5'4; @$#$"$3;.

! 5(%2D&), "' 1$&)/' 9 $0$9/'.$ #$@-7;.(&' U$5@ W/270(5@%( G$5 O;"9$/=@&( ; N$5) (d)2 Alexander von Humboldt Stiftung). N2, G)5(50$.$+ #)@&%'"7' *=$3$ U$5@; .'1)@ , @%;7; *)C+ 75'3' 9;. 9' 52"$>/'.'".

8(//2, ; >$.&5) 2007 %$7;

Shifting Meaning and Value through Imitation in the European Late Neolithic 5

Abstract

The imitation in bone or antler of objects originally made in other raw materials may have a number of different embedded meanings. Imitation may result from the scarcity or inaccessibility of the original raw material. Imitation may occur within new so-cial contexts. Finally, imitation may serve to retain the social meaning and alter the physical properties enough to make the object usable in a different way. The argument will be made here that the very act of transformation into new altered forms and raw materials carries its own social information to the community for whom the imitation is intended. None of these meanings are mutually exclusive but may instead be intertwined. In Central Europe, the phenomenon of imita-tion is widespread, although not very common in bone tool assemblages. The objects to be discussed are all small and designed for individual use. Some are ornaments to be worn and, thus, displayed. Other objects take the form of tools, although not intended for their original use. This interpretation is based on their wear and context. Such imitations seem rather to have functioned in a more intimate sphere, con-necting individuals to other worldly concerns. This paper will concentrate on the time span from the Late Neolithic to the Copper Age. By the Bronze Age in this region, if there is imitation, it does not seem to be carried out in the media of bone or antler. Examples will be drawn from bone and antler finds in France, Switzerland and Hungary.

!"#$%"

&%'()*'+ # ,'-(,. )/0 1023 41"5%"('6, 7,' 4"16'-80 /39. #10/9"8' # '8:.; %)("1')9'6, %0<3(= %)(. 6<" '8:' 6,9)5"8' 6 8.; #8)>"887. &%'()*'+ %0<3(= /3(. 1"#39=()(0% 6'5-3(80-(' )/0 8"50-(3480-(' %)("1')9'6, # 7,.; 10/.9.-7 01.2'8)9.. &%'()*'+ %0<3(= #‘76.(.-7 3 %"<); 806.; -0*')9=8.; ,08-(",-('6. ?)1":(', '%'()*'+ %0<3(= -93236)(. #/"1"-<"88$ -0*')9=8020 #8)>"887 () #%'8$6)(. @'#.>8' 0-0/9.60-(', 7,' 50-()(8' 597 (020, A0/ 6.,01.-(0-636)(. 0/‘B,(. 1'#8.%. :97;)%.. C123%"8(, 7,.D /35" 41.6"5"8.D 3 -()((', 6 (0%3, A0 ),( (1)8--@01%)*'+ 1">"D 3 806' #%'8"8' @01%. ' %)("1')9.

680-.(= -60$ 69)-83 -0*')9=83 '8@01%)*'$ 3 -3--4'9=-(60, 597 7,020 '%'()*'7 41"58)#8)>"8). ?'7,' # 8)6"5"8.; #8)>"8= 8" B 6#)B%80 6.,9$>"8.%., 608. %0<3(= /3(. 4"1"49"("8.%.. E F"8(1)9=8'D G6104' @"80%"8 '%'()*'D B :.10,010#406-$5<"8.%, 8" 5.697>.-= 8) 6'5-3(-8'-(= #8)>8.; 8)/01'6 ,'-(78.; #8)175=. E-' 41"5-%"(., 7,' 8)6057(=-7 6 -()((', 8"6"9.,.; 10#%'1'6, 0@01%9"8' '85.6'53)9=80. H"7,' # 8.; B 41.,1)-)-%., 7,' 80-.9.-7, ' (),.% >.80% 6'5,1.(0 5"%08--(136)9.-7. &8:' 41"5%"(. 0@01%9"8' 3 6.2975' #8)175=, ;0>) 608. 8" /39. 41.#8)>"8' 597 +; 4"1-6'-8020 6.,01.-()887, +; '8("141"()*'7 0-806)8) 8) +; #80:"80-(' () ,08(",-(' #8);05<"887. I),' '%'()*'+ -,01': #) 6-" %029. 6.,01.-(0636)(.-7 6 /'9=: '8(.%8'D -@"1', 406‘7#3$>. 0-0/.-(" # '8-:.%. #"%8.%. (31/0()%.. F7 -()((7 /35" -,08*"8(106)8) 8) >)-060%3 410%'<,3 6'5 4'#8=020 8"09'(3 50 50/. %'5'. J) 50/. /108#. 6 *=0%3 1"2'08', 7,A0 '-836)9. '%'()-*'+, 608. 8" 6.,0836)9.-7 # ,'-(. )/0 1023. K1.,9)5. #8);'50, # ,'-(,. () 1023 /353(= 8)-5)8' 3 -()((' # ("1.(01'D L1)8*'+, M6"D*)1'+ () N201A.8..

Introduction

The American Heritage College Dictionary diction-ary offers several definitions of imitation:

1. The act or an instance of imitating

2. Something derived from or copied from an original

3. Mus. Repition of a phrase or sequence often with variations in key, rhythm and voice - made to re- semble another, usually superior material.

These definitions, however, are not only static, but they also disregard the social and cognitive impera-tives lying behind imitation. Anthropologists and sociologists have described behavioral imitation as an important social variable in, among other things, the cultural transmission of information1. This has usually been described in terms of learning behavior 1 J. Nicod. http://www.warwick.ac.uk/fac/sci/Psychology/ imitation/Background/.

Alice M. Choyke

Shifting Meaning and Value through Imitation in the European Late Neolithic

Alice M. Choyke6

but can be applied to behavior and attitudes associ-ated with the use of objects as symbolic ‘stand-ins’ as well. The act of imitation in behavior, customs or material culture within or between groups of peo-ple seems to increase in frequency at times of social change, when new territorial and social boundaries are evolving. Imitation of special objects may take place at the level of the individual, the household, the village, the region or even further afield. The greater the distance and time from the original source, the less likely it is that the original meaning embedded within the form and/or raw material of a particular object type will retain its initial sense. The end of the Neolithic in Continental Europe dates to the end of the 5th millennium in the Carpathian Basin and the 3rd millennium 1000 km further west in eastern France and western Switzerland. However, no matter when these cultural transformations get underway, these are times when social structures seem to have become more hierarchical and complex with increasing social differentiation. Metal technol-ogy, appeared as a high status raw material. Probably there was also increasing inequality with regard to access to goods made from special raw materials like stone, shell and metal. Archaeological materials can be very unevenly preserved due to accidents of soil and subsequent human activity. It is likely that many different kinds of imitation existed in the past but only a scattered few have come down to us, some of these made in osseous materials which are gener-ally well preserved. The end of the Neolithic appears as a time when hunting, and the animals associated with hunting, assumed importance in the ritual life of many groups across Europe. Access to certain body parts from particular species became notably gender, age, and possibly rank, dependent. On the face of it, bone, antler and canine teeth/tusks would appear to have been ‘cheap’ raw mate-rial, readily available for the production oftools and ornaments. However, even today these osseous mate-rials are not at all neutral in terms of symbolic mean-ing. The makers and users of special implements of all sorts must have had a clear concept of the so-cial meanings embedded in the raw materials they exploited. The special traits they attributed to the particular animal species supplying the raw materials were probably intertwined with layers of meaning in these special objects. Some of these layers of mean-ing would have been unconscious, others conscious but considered too obvious for discussion while others would have represented deliberate, conscious manipulations of symbolic reality. At the end of the Neolithic, across Europe from France to the Black Sea, one can find regular, although not very com-

mon, examples of imitation of special object types in funerary as well as other special contexts. This imita-tion involved transformations between raw material classes and sometimes resulted in subtle alterations in form. Transformations of objects in terms of their raw material and sometimes simultaneous alterations in form reflect the retention of the basic meaning be-hind the object and the added meaning derived from the new context in which the object is being used. These objects can reflect status, gender, age, profes-sion, and combinations of all of these. Sometimes, when the artifact is removed from the original social context, only part of the message was transferred along with the altered physical object to which new, additional, meanings may have been ascribed. People-artifact interactions occur on various scales (Schiffer 2002, 1148). The kinds of transfor-mations described here are not large-scale but rather tend take place on a small scale within or between communities. The argument will be made here that the very act of transformation and alteration carried its own social information for the audience for the imitation, both the broader public and the users of the object. None of these meanings would have been mutually exclusive but may have been closely intertwined and interdependent. The phenomenon of imitation is widespread, although not very common in bone tool assemblages from the Late Neolithic of Central Europe. The ob-jects to be discussed here are all small and designed for individual use. Some are ornaments for wearing and, thus, were displayed by their owners. Other such objects took the form of tools. These, however, had the form of workaday utensils but were, first and foremost, display objects of some sort. This interpre-tation is based on the decoration found on them, the kinds of special polished use wear they exhibit and the contexts in which they were found. Such imita-tions seem often to have functioned in the intimate household or village sphere, connecting individuals to other-worldly concerns which, at the same time, would have reinforced social cohesiveness (between gender and age cohorts in a village, between extend-ed clans, or groupings within larger socio-political units, for instance). By the time the Early Bronze Age truly be-gan (in western Switzerland c. 2200 BC and the Carpathian Basin c. the end of the 4th millennium), imitation in material culture no longer seems to have been carried out in the medium of bone or antler. Examples will be drawn from special bone and antler objects from final Neolithic contexts in the French Jura, Switzerland and Hungary where copper or

Shifting Meaning and Value through Imitation in the European Late Neolithic 7

bronze objects underwent transformations into bone or antler or vice versa. The facts surrounding these transformations are not all the same. The cultural con-texts include lake dwellings in western Switzerland (final Neolithic), extensive flat sites in the final Neolithic Tisza Culture in southeastern Hungary, and a slightly later Chalcolithic Boleráz village set-tlement in northwestern Hungary. At this latter site, the worked bone material still displays clear links with the regional late Neolithic. It seems that in this transitional period imitation as a behavior increased as old forms were adjusted to new social contexts and situations. Sometimes forms were adopted and adapted in new places because of perceived meanings having nothing to do with their original significance. However, drawing conclusions about the manner in which prehistoric societies worked is always fraught with uncertainties because so many facts are sim-ply unavailable. Some examples of imitation will be cited from modern or historical contexts as models of alternative imitation possibilities. These examples include well documented historical and ethnographic contexts of the Sami (popularly known as the Lapps) in Scandinavia, a society in rapid but relatively un-forced transition, and a short description of the use of cowries and their imitations over a wide temporal and geographic scene. Imitation also reflects complex phenomena. The five types of imitation described below may occur alone or in combination with each other. Recognizing how social behavior is manifested in material culture is always challenging, risky, and open to a variety of interpretations. The motivation for imitation takes numerous forms. Rather than present certain ‘archae-ological facts’ the main purpose of this paper will be to illuminate further avenues for future research.

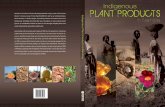

Classification of Imitation Imitation in bone or antler of objects originally made in other raw materials may mean a number of dif-ferent things both to the target group for whom the imitation was intended and for the person employing it. Five different types of imitation have been identi-fied here (fig. 1). The first are two different types of imitation of objects relating to changes in status and are expressed through maintenance of the form but transformations in raw material. These types of imitation can occur both within communities and be-tween societies. The third and fourth types of imita-tion are related to shifts in the embedded symbolism or use context of the object expressed either in the raw material or in the form itself. The final type of imitation, for which there are only examples from

late prehistory and even later, involves imitation of the form but with virtual loss of the original meaning (fig. 1).

Imitation type 1: imitation in easily avail-able materials

The first type of imitation is that from rare raw ma-terials into easily available materials. For thousands of years, long before the end of the Neolithic in Europe, antler, bone and teeth were important raw materials for manufacturing tools and ornaments. Antler was valued for its density and relative resist-ance to shock while bone could be used to produce sharp tools for piercing and scraping (Currey 1979, 313 ff.; MacGregor/Currey 1983, 71 ff.; MacGregor 1985, 23 ff.). Teeth, especially canines with their hard enamel, could be used as sharp-edged scrapers (e. g. wild boar mandibular tusks) or as ornaments (e. g. pig tusks, canines of red deer stags, canids, and brown bear). This was still true when societies be-gan to experiment with copper, first cold hammered and later smelted. Metal technology developed ear-lier in Central Europe (middle of the 5th millennium BC in the Balkans) so that forms such as decorative clothing pins appeared almost ‘ready-made’ in ar-eas just beyond the Alpine Foreland. Copper objects such as pins and beads also began to appear as high status objects in the first half of the 4th millennium BC in a very scattered distribution in French and Swiss Neolithic sites (Fasnacht 1995, 186 ff.). It is likely that the virtual absence of metal on settlements is caused by broken objects being melted down and re-cast or taken out of circulation by being placed in funerary contexts as items of conspicuous wealth and status. The lake dwelling sites of the Alpine Foreland are notable for the rich and varied worked bone, antler and tooth assemblages from various Neolithic periods (for example Strahm 1972-1973, Ramseyer 1987, Schibler 1987, 1997; Deschler-Erb 2001). This variability increases toward the very end of the Neolithic (Corded Ware) at the beginning of the 3rd millennium BC with the addition of a number of decorative pin types in antler and bone which ap-pear abruptly at this time in considerable numbers on all lacustian sites of this period (Gallay 1968; Billamboz 1978, 170; Ramseyer 1987, 4 f.; Choyke, unpublished2). These pins slightly post-date the ap-pearance of bronze prototypes on Central European

2 Also typical in the unpublished Final Neolithic Auvenier worked osseous materials at the lacustian site of St. Blaise on Lake Neuchâtel.

Alice M. Choyke8

Fig. 1. Imitations related to status change and to alter embedded symbolism or for use in different contexts

sites. Clearly people living in the Swiss villages would have observed both the metal pins used on the clothing of both local and far-flung trading partners and recognized the high status denoted by their own-ership. At the well preserved Late Neolithic-Early Bronze age site of Arbon-Bleieche 3 (3384 - 3370 BC, dendrochronological date for the latest occupa-tion), aside from the presence of a copper awl sug-gesting a limited local production, there is clear evi-dence of long distance trade contacts involving more sophisticated objects. The people of this settlement, as at other coeval sites in the Alpine Foreland, used imported flint from northwestern France and north-ern Italy while the shape and ornamentation of some of the ceramics was clearly influenced by pottery styles fashionable in the Boleráz Culture of Central Europe (Luezinger 2000, 56 ff. fig. 270). Some

people at these settlements may have possessed lo-cally made copper/bronze pins and even axes (pl. 1,1a after Strahm 1979, 60 ff. fig. 10A-B) although these clearly would have been re-cycled or buried with their owner. Otherwise, people wore copies of these exotic high status goods for which there are good formal parallels, not only far away at Central European sites but also scattered examples nearby in western Switzerland and eastern France (pl.1,1b after Strahm 1979, 690 f. fig. 10A-B). The copies themselves, however, represent real labor invest-ment. They are beautiful and the fact that they dis-play heavy and repeated curation suggests that their bone/antler copies were valued in their own right3.

3 The club-headed decorative, Final Neolithic Auvenier Period pins from St. Blaise were repeatedly reworked and conservedas the tips broke.

Shifting Meaning and Value through Imitation in the European Late Neolithic 9

Copies of decorative pins in osseous materials based on high status metal prototypes from both outside the area and within it, represent a clear example of the first type of imitation.

Imitation type 2: imitation as enhancement of original meanings

The second type of imitation involves the enhance-ment of the status of a socially identifiable object. Imitation is one way to transfer and transform the meaning of an object or the value of the raw material it is made from for a new audience from outside the original social context. Such enhancement of mean-ing may occur both within and between societies. A particular object may have special social meanings that change depending on the rank or gender/age group(s) that the owner belonged to. Objects trans-formed in this sense are usually found as evidence within the context of special burial rituals.

This Type 2 imitation involves particular ar-tifact types customarily produced in bone or antler. With the availability of new high status materials, the form with all its traditional meanings was main-tained, but was given added meaning by producing it in a new, rare, and valuable material. This would have allowed continuity in the ethnic identification embedded in the object type but would also have am-plified the perceived status of the object. Two ex-amples provide a demonstration: one ethnographic example of Sami spoons to help clarify the point and another example concerning the necklace ‘buttons’ from the end of the Neolithic, found in France and western Switzerland as well as southern Germany. A third example offered here involves imitation of spin-dle whorls in ritual contexts from the slightly later, early Chalcolithic period.

Sometimes it is easier to draw on properly doc-umented ethnographic materials to illustrate theoreti-cal points. In a sense, such objects provide examples of the way the imitation of material properties reflect-ed attitudes and behavior in distant prehistoric times. The Sami have traditionally followed herds of rein-deer in northern Scandinavia and Russia, although theirs is also a history of an increasingly sedentary life. Nevertheless, they have succeeded in preserv-ing their language and ethnic identity in the face of encroaching modernity. The Sami spoon shown here (pl. 1,2a.2b) is an interesting and complex reflection of this process. The initial form of imitation from antler to silver, that is from a common raw material to a more valuable rare one, best fits the Type 2 form of imitation defined here.

These two raw materials have apparently been interchanged by Sami craftspeople over a long pe-riod, even centuries. The first, antler spoons (pl. 1,2a) were probably just that: spoons made from a locally available material, in use long before metal was introduced. Later, when silver spoons became the norm (pl. 1,2b), they may have been copied back into antler as a material which was cheap, easy to work and available on the spot. It is also possible that some of antler spoons were sent to goldsmiths in towns as models for silver spoons made especially for the Sami market and reflecting Sami taste. Aspects of ethnic identity are embedded in the form that was consistently preserved. Since the 1950s, silversmiths who have settled in the Sami areas have made “Sami” silver spoons for the tourist market based on silver spoons – which may have preserved the old (metal) spoon models that would other wise have disappeared (Leif Parelli, personal communication 2003)4. This latter example is more an example of the development of a Type 5 form of imitation where the original meaning is in the process of being lost with the objects re-inter-preted in the nostalgic tourist context.

Another (Type 2) prehistoric example of the amplification of status though imitation into a high-er value raw material concerns the antler and bone buttons from the end of the Neolithic in southern Germany, the Alpine Foreland of Switzerland and the French Jura (Strahm 1982, 183; Schibler 1987, taf. 21,26; Neilsen 1989; Gross 1990, 1991; Egloff 1990, 320, Choyke, unpublished5). It is thought that these buttons may actually have functioned as clo-sures for bags or were strung on necklaces. The but-tons occur in many forms and sizes. One of the most elaborate types has two holes with radiating lines of dot decoration and dots around the outer edge (pl. 2,1 after Strahm 1982, fig. 1,6). These buttons are generally found in settlement materials. Bronze copies of these buttons may be found in a few rare instances in funerary settings in dolman burials in southern France. Dolman 2 of Frau in Cazals (Tar-et-Garonne) contained three bronze buttons with clear parallels with the Swiss finds. They also have two holes and the same radiating pattern of decorative dots (pl. 2,2 after Parot and Clottes 1975, 392 fig. 9,2.3.4). Clearly these buttons had a particular sym-bolic meaning for the people who had the right to wear them. Making them in bronze or copper, then

4 Information from Dr. Leif Pareli, curator at the Norwegian Museum of Cultural History (Museumveien 10, N-0287 Oslo, Norway), who provided specific background informa-tion on the Sami spoons and lasso loops. http://www.norskfolke-museum.no

5 Among the Final Neolithic, Auvenier period worked osseous materials at St Blaise.

Alice M. Choyke10

relatively rare and very high status raw materials, would have given them even more value in the eyes of the mourners at the funeral (Chapman 2000) while retaining the original social meaning embedded in their form.

There is yet one more example of this kind of imitation which appears on sites of the early Chalcolithic (4000 - 3600) in western Hungary. At this time, high status spindles and spindle whorls were made of copper although the majority were surely made from wood or bone as in earlier times6. It seems likely that the wooden or antler spindles and whorls would also have had a very similar shape. However, in this slightly later period there are some smaller, non-functional imitations made from gold found exclusively in ritual burial contexts of women in eastern Hungary (Marton 2001, 133 ff.). Here the gender meaning of weaving equipment was retained while adding on the value of the gold.

Imitation type 3: imitation and material transformations across intra societal bound-aries

Type 3 imitation involves copying of the general form of the original artifact into an available raw material. The new raw material adds on new, related symbolic meaning to the symbolism embedded in the origi-nal object. This type of imitation may also be a way to signal social differentiation or a way to transfer and transform the meaning of an object or the raw material for different groups within the same social setting. Such transformed objects may have had spe-cial social meanings for individuals within cohorts based on rank, age, and/or gender. The objects at-tained additional meaning(s) depending on the target audience. The change in raw material, although it may have represented new meanings, was not neces-sarily related to a change in value. Rather the new material also carried a new message (stone to ant-ler, bone from one species to bone of another, tooth to bone). The transformation of objects may involve imitation of specific or general forms. The latter may have a functional aspect as well. Type 3 and Type 4 forms of imitation are related to each other and may even be embodied in the same object as is the case with the imitation red deer canines to be discussed below. This category is intriguingly complex and is the kind of imitation most often found in the worked bone, antler, and tooth assemblages at the end of the Neolithic.

6 Choyke, unpublished from the Tiszapolgár flat settlement of Polgár 6 the remains of antler spindle pin with the double groove for holding the thread.

Examples presented here include special ant-ler axes, imitation roe deer metapodial awls, and red deer imitation canines from the final Neolithic as well as a special find of a bone projectile point from the slightly later Chalcolithic context in Hungary.

Another rare find characteristic of the final Neolithic lake-dwelling sites in western Switzerland and eastern France are antler axe/adzes, hafted per-pendicular to the long axis of the blade. The major-ity of such finds, made from the rose and beam of a red deer antler rack, are tools intended for every-day activities. However, occasionally some of them display quite different use wear, a high polish, and combine characteristics of both regular antler axes and the polished stone “battle” axes, another type of prestige item known from the region. Another spe-cial antler axe form found in eastern France in the same period imitated socketed metal axes (pl. 3,1; Billamboz 1978, 116, 163 fig. 71; Bailloud 1979; inv. no. 2160 Chastel 1985, 71; Burnez-Lanotte 1987; Baudais/Delattre 1997; Choyke, unpublished7). Both these kinds of special antler blades are darkly pol-ished overall, with copies of leather binding around the haft hole, produced by leaving the rough original surface of the antler intact in thin, criss-crossed lines or broad stripes on this part of the object. Billamboz (1978, 116) suggests that this binding is an imitation of the handles for metal axes with bifurcate handle heads (l’emmanachement des haches de métal avec la gaine à tenon bifide). Although worn, these axe/adz-es display none of the battering characteristic of oth-er similar axe/adzes. The ash wood handles are often preserved intact in the transversely hafted specimens. This suggests that these objects were disposed dif-ferently than other antler axes used as regular tools. In this case, there is no suggestion that these objects were made en lieu of their stone or metal counter-parts. Rather, use of the more prestigious form in antler combined the high status of the stone or metal forms with the recognized meaning inherent to the antler axe/adze or axe form. Furthermore, since the antler itself comes from stags, it seems likely that the symbolic meanings attributed to the stag as a princi-pal large game species were also embedded in these special antler artifacts.

Another excellent example of symbolic trans-formation through form and raw material, again sig-nificantly involving raw materials from game, is a unique case from a disturbed late Neolithic burial in France. It contained multiple burials including the

7 Such special axes were also found in the unpublished Auvernier worked osseous materials at the lacustrian site of St. Blaise on Lake Neuchâtel. One particular axe, with its ash handle complete, was dark colored and highly polished with a decorative band of the antler outer skin retained at its shaft hole.

Shifting Meaning and Value through Imitation in the European Late Neolithic 11

well-preserved skeleton of a young woman, scattered remains of another adult individual and remains of children. Here, aside from perforated red deer ca-nines and their imitations in stone, the deceased in-dividuals were buried with an awl apparently carved from the metatarsus of a roe deer, but actually whit-tled from the larger metapodium of a red deer (pl. 3,2; Roussot-Larroque 1982, fig. 2) as well as an awl of the same size made from a roe deer metatarsal. Thus, the imitation is not only of the form of the tool but also of the species and raw material! Clearly, this complex transformation is not related to any scar-city of roe deer in the immediate environment but rather to the immensely complex wild/hunt symbol-ism represented by these two cervid species for the individual and the society they lived in.

Imitation Type 3, where the general form was imitated in an available raw material but where new meaning was added onto the original form also in-cludes bone copies of red deer canine teeth. Such copies of stag canines are found from Paleolithic times on in Europe. However, there are some spe-cial cases from the end of the Neolithic in Central Europe including the finds from Polgár–Cs!szalom-d"l!, a settlement in eastern Hungary dating to the 5th millennium BC. This period marks the time of the Late Neolithic in the Carpathian Basin. The equivalent social phenomena in the French Jura and western Switzerland seem to have begun almost 1000 years later. Of particular interest here are ornaments such as necklaces containing red deer canine beads – the upper mandibular canines – or their imitations carved from the long bone diaphyses of large rumi-nants (Choyke 2001). All objects found in such rit-ual contexts carry their own special, codified mean-ings relative to both the deceased and the society in which he or she lived. The symbolic meanings of whom real canines were given to and who received the imitations were apparent, even obvious, to the people taking part in the funeral ritual, although we can only guess at the specifics. The copies were not made because of a shortage of red deer canines. They embodied various meanings as subtly altered practical and symbolic phenomena, related to group identity and social continuity during the burial ritual. Furthermore, while the real red deer canines may actually have belonged to the deceased, the imita-tions, more labor intensive to produce, exhibit stages of wear from new to heavily worn. This suggests that the ornaments they were made into had some kind of a history behind them, having been compiled from a number of sources, perhaps for the burial event itself. Pydyn (1998) defines the value of an object as entail-ing a combination of shape, originality and artistry as well as its prime and added value. Red deer canine

beads and their copies would represent the perfect kind of valuable mortuary goods (Bailey 1998) be-cause they came from an important game animal and were restricted in their availability. Pearson (1998) has pointed out that the moment of interment is an emotional theatrical moment. What better time not only to honor the dead but to reconfirm and strength-en the fabric of social intercourse?

The proportion between sexes is roughly equal in the graves of the large Polgár 6 horizontal settle-ment adjacent to the tell site. Altogether 11 graves, male and female, juvenile and adult, were found con-taining necklaces with real red deer canines and/or their blunt, propeller-shaped imitation beads (pl. 4,1; Anders, personal communication). Generally, men were given real canines and women seem to have possessed imitations. However, one of the graves was that of an older, high status woman who apparently had the right to wear a necklace with a large number of real red deer canine beads strung with large spondylus shell beads (pl. 4,2, lower necklace). She was accompanied by other valuable grave goods as well. Interestingly, the opposite of this phenomenon was observed at a Middle Neolithic Hinkelstein cem-etery at Trebur in Germany (Spatz 1999). This site, containing belts and necklaces with both real and imitation red deer teeth, would have been contem-porary with the Hungarian Polgár 6 site. As opposed to the Hungarian finds, these imitations made from the shell Margarita auricularia are quite realistic in terms of their shape and size. Also different from the situation in the Hungarian burial context, the imita-tions were generally presented to the men and the real red deer canine beads to the women, including 230 in one grave and 86 in another! It seems that it was the act of copying the general form of these teeth which permitted transference and the accumulation of meaning in both contexts, even if the end results differed.

Finally, an apparent Type 3 imitation came to light in the worked osseous materials from a slightly later site, Gy!r–Szabadrét-domb, a middle Chalcolithic Boleráz Culture settlement (3338-3042 BC cal), contemporary with the aforementioned set-tlement of Arbon-Bleiche 3 in Switzerland (Choyke, in press). This site is located in the northwestern cor-ner of present-day Hungary. The bone and antler pro-jectile points which came to light at Gy!r–Szabadrét-domb are extremely interesting from several points of view. First, in Hungary at this stage of research, they appear to be manufactured uniquely in the Boleráz phase of the Middle Chalcolithic. No comparable projectile points manufactured in osseous materials are known either from earlier or later periods in this region until the later Bronze Age. Examples of simi-

Alice M. Choyke12

lar types have been found in the surrounding territo-ries. Pape (1982, 141 ff.) places all the types found at Gy!r–Szabadrét-domb within his Group D, which he suggests may have had metal proto-types. There is also a short triangular point made on a bone flake. It was chipped on the edge like a stone arrowhead, perhaps a case of an expedient Type 2 imitation of such a tool. Two of the projectile points with angled cross-sections, however, have a high handling-polish (pl. 5,1). Both specimens are beautiful, glossy and have a warm honey-brown color. The manufactur-ing marks seem fresh, unworn by use or re-working. This suggests that they were never actually used but functioned more emblematically, perhaps as part of an amulet satchel. Their angular shape seems to rep-resent an attempt to copy a valued (possibly metal) projectile point type seen somewhere outside the im-mediate area of the site. If the interpretation of the high handling-polish related to their use as amulets or talisma is correct, this would also be a case of symbolic imitation of a form associated with hunting or human conflict.

Imitation type 4: copies of specific emblem-atic forms altered for use in new functional contexts

Imitation Type 4 is represented by artifacts in which the social meaning of the object reflects social or ethnic identity, but where the form or raw material has been altered to make the object conform to new working or decorative contexts. Thus, the physical properties may be altered to make the object usable in a new way whilst the form is carefully maintained. The raw material chosen may have been as valuable or even less valuable than that which was used origi-nally. By altering some aspects of the form of a spe-cial object, it became possible to employ it in other social contexts or for other members of the society to use it. Thus, objects which were originally strung on necklaces can be altered to be sewn on clothing or to give them a slightly different appearance.

The Sami traditionally produced characteristic lasso loops with incised decoration in antler for use in reindeer herding (pl. 5,2a). Nowadays, although still connected to reindeer herding, such lasso loops are used with snowmobiles as part of reindeer herd-ing. The form and size of these loops have been faith-fully reproduced in plastic that is stronger and more resilient, but they still fit specifically Sami taste re-quirements and reflect ethnic identity both in terms of form and the activity where they are traditionally used (pl. 5,2b). As with most societies in transition, Sami households are filled with socially emblematic

objects which are traditional in form but which are made in new, convenient raw materials (Leif Parelli, personal communication).

The Hungarian imitations of red deer canine beads in necklaces also contain an element of Type 4 imitation. The unique propeller shape of the imi-tation beads on the one hand had a practical qual-ity, surpassing that of the original anatomical shape. These carved bone beads can be fitted perpendicu-larly to each other, producing the smoother, more orderly look of the ornaments found with younger females (see pl. 4,1) . On the other hand, as the pro-peller-type beads became worn and broke, they could be re-drilled and came to resemble the real red deer canines more closely. Thus, the form of the imitation of both the lasso loops and red deer canine beads had practical as well as symbolic aspects that intertwined and reinforced each other.

Imitation type 5: copying of forms between groups without transference of meaning

Type 5 involves copying external, re-interpreted forms between societies. Ultimately these shapes have nothing to do with their meanings in their own original contexts. The forms are adapted from a mis-construed interpretation that is then almost totally re-interpreted. Sometimes the original social and tech-nical function may be completely lost in the process of physical imitation and transformation. From more recent periods comes an example of the use of the crucifix form in Avar metal finds. The Avars, peo-ple of Asiatic steppic origins, practiced a form of shamanistic religion. However, they saw crucifixes at the court of the Byzantine Emperor and adapted them as a symbol of power rather than as a religious symbol.

Among animal raw materials there is also the curious case of cowry shell beads and their imita-tions, which were in use from ancient Egypt to China to Europe. A few of their many and complex trans-formations are worth citing here. In Egypt, cowries and their imitations in materials ranging from gold to bone were worn suspended from women’s girdles. The similarity of the opening of these shells to the hu-man vulva no doubt accounts for their use as fertility symbols, even in the present day (Reese 1988, 262). In slightly later periods, their use reached China ei-ther through diffusion or actual contact. Here their meaning was transformed and cowries and their im-itations began to be used as money (Egami 1974, 3 f., 15, 44).

Although natural cowries only reached the Minusinsk basin in Central Asia in the Iron Age in

Shifting Meaning and Value through Imitation in the European Late Neolithic 13

limited numbers if at all, their imitations in glass paste and bronze, even in bone, are common. They were sewn on clothing or worn as pendants or in strings of beads. They were perforated or grooved longitudinally to produce serrated edges. These ob-jects, also considered Chinese, could have been em-ployed as ornaments or amulets, but were no longer thought of as money (Ierusalimskja 1996, 29).

Cowrie shells and cowry imitations as beads can also be found as far west as Estonia where their use was re-interpreted once again as a snake’s head within the framework of a snake cult and they were meant to protect the wearer against mischance. On the other hand, the Sarmation period glass imita-tion cowrie from a woman’s grave in Hungary was again thought to be related to fertility magic (Kovács 2001, 172). Modified cowries are found in Early Central Asian Sarmatian contexts as well as later in the Carpathian Basin, exclusively in women’s graves. However, their form here once again represented a reinterpretation from their original use in Central Asia where it appears as decoration on belts (Kovács/Vaday 1999, 262 ff.).

This shell can be seen used as exotica on la-dies’ apparel or in necklaces even today, in 21st cen-tury Europe. The men and women wearing these pieces, however, have little idea about the historical transformations of their embedded meanings in vari-ous periods and geographical settings. Having lost most of their symbolic value and being a rather com-mon shell, they are rarely copied in alternative raw materials. The originals are actually valued in this new context as symbols of an “organic” or “ethno” back-to-nature look.

Conclusions

Different types of imitation are sometimes embodied in a single object. Imitation of motifs and forms can be lifted from various media to be combined within a new artifact in new raw materials to produce layers of meaning which may or may not be conscious on the part of the people observing or using the object. In fact, different levels of symbolic meaning can exist for individual beholders or groups of beholders of a particular object type.

It appears that imitation may occur more fre-quently in times of social instability. Most of the ob-ject types chosen for analysis here come from con-texts dating to the end of the Neolithic. This was a time when many tribal societies across Europe were in transition both in terms of technology and their in-creasingly hierarchical social structures. This inevi-tably led to inequalities in the availability of certain

prestige goods. Bone, antler, and tooth were still very important raw materials at the end of the Neolithic and continued to have significance well into the Bronze Age in many parts of the Old World. Thus, it is not surprising that they played an important role in various kinds of imitative behaviors. Objects made from osseous raw materials became less and less im-portant in manufacturing as time progressed, with the exception of peripheral regions with less access to wood and other raw materials. This would per-tain to Arctic peoples such as the Sami in northern Scandiavia and Russia.

Five different types of imitation have been defined here. Type 1 and Type 2 are related in the sense that they both concern maintenance of mean-ing with enhanced value. Type 1 Imitation involves raw material transformations from a prototype pro-duced in a rare and therefore particularly valuable raw material into a more easily available medium. Thus, people living in later Neolithic villages along the lakeshores in Switzerland frequently copied the forms of coveted copper and bronze decorative pins which were probably in the possession of the highest ranking individuals both in the village and outside the immediate region.

Type 2 imitation involves a transformation into a valuable raw material where the form of the origi-nal object made in a common (i. e. less prestigious) raw material had an important iconic meaning in terms of ethnic or age/gender identity. This mean-ing of identity was enhanced by transformation into more rare and thus, valuable raw materials. The two examples presented include Sami antler spoons with a complex raw material history. The form, originally made in antler, was always maintained as something particularly Sami in taste, but the form of the spoons was later manufactured, that is, imitated in silver. The Late Neolithic button shapes with two holes and radiating dot decoration used in necklaces and found both in settlement materials and burial contexts in western Switzerland represent another example of a form originally made in easily available antler or bone, with strong iconic associations of some sort in one region. The form was then copied into a more valuable raw material, bronze, to produce grave goods for a burial in southern France. Type 3 and Type 4 imitations are related in that they both concern the manufacture of particular objects in traditional raw materials. Imitation occurs within social groups and the raw material transformation involves a change into an equally available raw material. However, they dif-fer in terms of their final intent. The general form is copied, but the raw material changed in symbolically significant ways. Thus, the original meaning intrinsic to the form is maintained and the symbolism of the

Alice M. Choyke14

new raw material is added on. There is no question of added value in this kind of imitation. Type 3 was the most important kind of imitation in osseous ma-terials in the final Neolithic in Switzerland. The sali-ent features of stone battle axes and socketed metal axes were imitated as decoration on common antler tool types. The ash handles of these axes are almost always preserved at lakeshore sites. The antler blades themselves are highly polished, exhibiting a very dif-ferent kind of use wear than what would be found on the workaday variety of antler adze/axe. Thus, these objects contain meanings embodied in the stone and metal axes, the antler adze/axe tool type and in the red deer antler they are made from. A similar situation is exemplified in a unique burial find from the same period in France of an imitation roe deer metapodium awl carved from a red deer metapodium found together with a real roe deer metapodium awl and other imitations of wild animal teeth. Here, the importance of the tool is enhanced by the change into another raw material derived from another, possibly equally significant, game animal. The red deer canine beads from burials dating to the end of the Neolithic in the Carpathian Basin also reflect shifts in meaning along with transformations from teeth to bone related to the age and sex of the deceased. Finally, a type of arrowhead discovered at a slightly later Chalcolithic site in northwestern Hungary appears to be an imi-tation of real working arrowheads produced in an-other raw material, possibly metal. However, two of the long angular points are glossy and a deep honey brown in color. Such intensive handling polish sug-gests that they were used as talism, perhaps designed to give good luck in hunting or conflicts. Type 4 imitation involves a copy of a very spe-cific form in a new raw material as well as alterations in a form. The changes occur in new functional con-texts although the original symbolic meaning of the form is retained. A good example of such imitation is found in the Sami lasso loops, originally used in traditional reindeer herding. With the new functional requirements they have been transformed exactly into more durable and resistant plastic, but their form, an iconic symbol of Sami identity, has been retained. The red deer canine beads from Hungarian sites dis-cussed here also fit this category as their imitation in an altered form in a different raw material also al-lows them to be strung into a more rounded, ordered way in female ornaments. In contrast, the imitation deer canines from a contemporary German Middle Neolithic cemetery signaled male identity.

There are no examples of Type 5 imitation evident among the bone, antler and tooth artifacts from late Neolithic Europe. This kind of imitation occurs be-tween social groups and is expressed in objects made of valuable raw materials. The raw material may be retained in the imitation but the original meaning understood by the people who first manufactured it is lost or in the process of being lost. This results in new interpretations in new contexts. From later prehistoric and proto-historic periods there is the ex-ample of cowry shell pendants and their imitations in various raw materials from gold to glass and bone. These began to be used in the ancient Near East, ap-parently related to fertility beliefs. The use of cowry beads and their various imitations is known from places as far away as China but used as currency. They also appeared in Europe in the Iron Age, again to be transformed unrecognizably in meaning as part of a snake cult in the Baltic region and were used as protective amulets. Currently such cowry beads have even been used as purely decorative exotic items in Europe. They continue to be altered in the same way but virtually all the original meaning(s) has been lost.

Imitation in objects is indeed a way of trans-ferring important information from person to person and from group to group through various special arti-facts. Imitation can be related to questions of prestige, rank, and group identity. Five types were described here in which an object is replicated containing more than one type of intertwined imitation. It is possible that other types of imitation have existed in other media from different periods and regions. It is hoped that this paper will inspire other scholars to explore this aspect of this very human behavior in their own materials.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to express her thanks to the following people: to Dr. László Bartosiewicz for crit-ically reading the manuscript for flaws in logic and editing. To Dr. Judith Rasson for more editing and for help with re-constituting the line drawings. All mistakes and flaws still lingering in the paper are the responsibility of the author. I would also like to thank the organizers of the EAA session in Thessaloniki on ‘Import and Imitation’, Yuri Rassamakin and Taras Tkachuk, for making it possible to present my ideas on this very interesting key concept in archaeology. Thanks are also due to Dr. Peter Biehl for undertak-ing the hard work of editing these proceedings.

Shifting Meaning and Value through Imitation in the European Late Neolithic 15

References

The American Heritage College Dictionary, Third edition, Houghton Mifflin Company: Boston.

Bailloud 1979G. Bailloud, Le Néolithique dans le Bassin Parisien, Gallia préhistoire (Paris 1979).

Bailey 1998D. Bailey, On being famous through time and across space. In: D. W. Bailey (ed.), The Archaeology of Value: Essays on Prestige and the Processes of Valuation. BAR Intern. Ser. 730 (Oxford 1998) 1–9.

Baudais/Delattre 1997D. Baudais/N. Delattre, Les objets en bois. In: P. Pétre-quin (ed.), Les sites littoraux néolithiques de Clairvaux-les-Lacs et de Chalain (Jura), III, Chalain station 3, 3200-2900 av. J.-C., vol. 2 (Paris 1997) 529–544.

Billamboz 1978A. Billamboz, L‘industrie du bois de cerf en Franch-Comté au Néolithique et au début de l‘Age du Bronze. Gallia Pré-hist. 20/1, 1978, 7–176.

Burnez-Lanotte 1987L. Burnez-Lanotte, Le Chalcolithique moyen entre Seine et Rhin inférieur: étude synthétique du rituel funéraire BAR Intern. Ser. 354 (Oxford 1987).

Chapman 2000J. Chapman, Tension at Funerals: Social practices and the subversion of the community structure in later Hungarian prehistory. In: M. Dobres/J. Robb (eds.), Agency and Ar-chaeology (London, New York 2000) 169–195.

Chastel 1985J. Chastel, Fouilles anciennes des lacs de Chalain et de Clairvaux. Les industries en bois de cervidés et en os, Collections du Musée municipal de Lons-le-Saunier no. 1, 1985, 61–81.

Choyke 2001A. M. Choyke, Late Neolithic Red Deer Canine Beads and Their Imitations. In: A. M. Choyke/L. Bartosiewicz (eds.), Crafting Bone - Skeletal Technologies through Time and Space. BAR Intern. Ser. 937 (Oxford 2001) 251–266.

Choyke, in pressA. M. Choyke, Continuity and Discontinuity at Gy!r–Sz-abadrét-domb: Bone Tools from a Chalcolithic Settlement in Northwest Hungary. In: J. Schibler (ed.), Bone, Ant-ler, Teeth. Raw Material for Tool Production in Prehistoric and Historic Periods. Proceedings of the 3rd meeting of the (ICAZ) Worked Bone Research Group. Basel (Augst, 4-8 September 2001) Internationale Archäologie Arbeitge-meinschaft (Rahden/Westf, in press).

Currey 1979J. D.Currey, Mechanical Properties of Bone tissues with greatly differing functions. Journal of Biomech. 12, 1979, 313–319.

Deschler-Erb 2001 S. Deschler-Erb, Die Knochen-, Zahn- und Geweiharte-fakte. In: S. Deschler-Erb/U. Leuzinger/E. Marti-Grädel/J. Schibler (eds.), Die jungsteinzeitliche Seefersiedlung Arbon/Bleiche 3 - Funde. Arch. Thurgau 9 (Kantos Thur-gau 2001) 277–366.

Egami 1974N. Egami, Migration of the Cowrie-Shell Culture in East Asia. Acta Asia 26, 1974, 1–52.

Egloff 1990M. Egloff, La rive nord du lac de Neuchâtel: du Magda-lénien à l‘âge du Bronze final. In: M. Höneisen (ed.), Die ersten Bauern 1 (Zürich 1990) 311–323.

Fasnachte 1995W. Fasnachte, Metallurgie. In: W. Stöckli/U. Niffeler/E. Gross-Klee (eds.), Die Schweiz vom Paläolithikum bis zum frühen Mittelalter. Serie SPM II, Neolithikum (Basel 1995) 183–192.

Gallay 1968A. G. Gallay, Le Jura et la séquence Néolithique récent/Bronze Ancien. Archives suisses d‘anthropologie générale 33 (Genève 1968) 1–84.

Gross 1990E. Gross, Entwicklungen der neolithischen Kulturen im west- und ostschweizerischen Mitteland. In: M. Höneisen (ed.), Die ersten Bauern 1 (Zürich 1990) 61–72.

Gross 1991E. Gross, Die Sammlung Hans Iseli in Lüscher. Ufersied-lungen am Bielersee 3 (Bern 1991).

Ierusalimskaja 1996A. Ierusalimskaja, Die Gräber der Moš#evaja Balka. Früh-mittelalterliche Fund an der nordkaukasischen Seidenstras-se (München 1996).

Kovács 2001L. Kovács, A glass imitation of a cowrie from the Sarma-tian Period in Hungary. Journal of Glass Stud. 43, 2001, 172–174.

Kovács/Vaday 1999L. Kovács/A.Vaday, On the problem of the marine gas-tropod shell pendants in the Sarmatian Barbaricum in the Carpathian Basin. In: A. Vaday (ed.), Pannonia and Bey-ond. Studies in Honour of László Barkóczi, Antaeus 24 (Budapest 1999) 247–277.

Leuzinger 2000U. Leuzinger, Die jungsteinzeitliche Seeufersiedlung Ar-bon/Bleiche 3, Befunde, Arch. Thurgau 9 (Kanton Thur-gau 2000).

MacGregor 1985A. MacGregor, Bone, Antler, Ivory & Horn: The Techno-logy of Skeletal Materials since the Roman Period (London 1985).

Alice M. Choyke16

MacGregor/Currey 1983A. MacGregor/J. D. Currey, Mechanical Properties as conditioning factors in the bone and antler industry of the 3rd to the 13th century, Journal of Arch. Science 10, 1983, 71–77.

Marton 2001E. Marton, New approaches to the spinning and weaving of Neolithic-Aeneolithic people in the Carpathian Basin (the „Shrewd Princess“ and looms). In: J. Regenye (ed.), Sites and Stones. Lengyel Culture in Western Hungary and Beyond (Veszprém 2001) 131–142.

Nicod 2000J. Nicod, Perspectives on Imitation from cognitive neuros-cience to social science, conference at Royaumont Abby, France (2000), http://www.warwick.ac.uk/fac/sci/Psycho-logy/imitation/Background/.

Nielsen 1989E. H. Nielsen, Sutz-Rütte, Kataloge der Alt- und Lese-funde der station Sutz V, Ufersiedlungen am Bielersee 2 (Bern 1989).

Pape 1982W. Pape, Au sujet de quelques pointes de flèche en os. In: H. Camps-Fabrer (ed.), Industrie de l‘os neolithique et de l‘Age des Metaux 2 (Paris 1982) 135–172.

Parot/Clottes 1975B. Parot/J. Clottes, Le dolmen 2 du Frau, à Cazals (Tarn-et-Garonne). Bull. Société Préhist. Française 72, 1975, 383–401.

Pearson 1998M. Pearson, Performance as valuation: Early Bronze Age burial as theatrical complexity. In: D. W. Bailey (ed.), The Archaeology of value: Essays on Prestige and the Processes of Valuation. BAR Intern. Ser. 730 (Oxford 1998) 32–41.

Pydyn 1998 A. Pydyn, Universal or relative? Social, economic and symbolic values in Central Europe in the transition from the Bronze age to the Iron Age. In: D. W. Bailey (ed.), The Archaeology of Value: Essays on Prestige and the Pro-cesses of Valuation. BAR Intern. Ser. 730 (Oxford 1998) 97–105.

Ramseyer 1987D. Ramseyer, Delley/Portalban II: Contibution à étude du Néo-lithique en Suisse Occidentale, Editions Universitaires Fribourg (Fribourg 1987).

Reese 1988S. Reese, Recent invertebrates as votive gifts. In: B. Ro-thenberg (ed.), The Egyptian Mining Temple at Timna (London 1988) 260–265.

Roussot-Larroque 1982J. Roussot-Larroque, Poinçon en os sculpté imitant un métapode de chevreuil dans la sépulture néolithique de l‘Abri Vidon à Juillac (Gironde). In: H. Camps-Fabrer (ed.), L‘industrie en os et en bois de cervidé durant le Néolithique et l‘âge des métaux, Deuxième réunion du groupe de travail n° 3 sur l‘industrie de l‘os préhistorique (Paris 1982) 124–134.

Schibler 1987J. Schibler, Die Knochenartefakte. In: E. Gross et al. (eds.), Zürich „Mozartstrasse“. Neolithische und bronze-zeitliche Ufersiedlungen 1. Monogr. Züricher Denkmalpfl. 4 (Zürich 1987) 167–175.

Schibler 1997J. Schibler, Knochen- und Gweihartefakte. In: J. Schib-ler et al. (eds.), Ökonomie-Ökologie neolithischer und bronzezeitlicher Ufersiedlungen am Zürichsee A. Monogr. Kantonsarch. Zürich 20 (Zürich 1997) 122–219.

Schiffer 2002M. B. Schiffer, Studying Technological Differentiation: the case of 18th-century electrical technology. American Anthr. 104-40, 2002, 1148–1161.

Spatz 1999H. Spatz, Das mittelneolithische Gräberfeld von Trebur, Kreis Gros-Gerau. Mat. Vor- u. Frühgesch. Hessen 19 (Wiesbaden 1999).

Strahm 1972-1973C. Strahm, Les fouilles d‘Yverdon. Jahrb. schweizerische Ges. Ur- u. Frühgesch. 57, 1972-1973, 8–16.

Strahm 1979C. Strahm, Les épingles de parure en os du Néolithique final. In: H. Camps-Fabrer (ed.), L‘industrie en os et en bois de cervidé durant le Néolithique et l‘âge des métaux, Premièree réunion du groupe de travail n° 3 sur l‘industrie de l‘os préhistorique (Paris 1979) 47–85.

Strahm 1982C. Strahm, Deux types de boutons de parure du Néoli-thique final. In: H. Camps-Fabrer (ed.), L‘industrie en os et en bois de cervidé durant le Néolithique et l‘âge des métaux, Deuxième réunion du groupe de travail n° 3 sur l‘industrie de l‘os préhistorique (Paris 1982) 183–194.

Shifting Meaning and Value through Imitation in the European Late Neolithic 17

PL. 1. 1a. Metal proto-types of decorative pins from Central Europe and France (redrawn by Judith Rasson after Strahm 1979, 60 f. fig. 10A-B); 1b. Antler imitations of metal proto-types from Swiss Late Neo- lithic lacustrian sites (redrawn by Judith Rasson after Strahm 1979, 60 f. fig. 10A-B); 2a. Sami antler- spoon (photograph by Alice Choyke); 2b. Sami silver imitation (photograph by Alice Choyke)

1b1a

2a 2b

Alice M. Choyke18

Pl. 2. 1. Antler and bone buttons with two holes and radiating dot decoration from Swiss Late Neolithic la custrian sites (redrawn by Judith Rasson after Strahm 1982, 184 fig. 1,3-6); 2. Bronze buttons from the 2nd dolman burial at Frau, á Cazals (redrawn by Judith Rasson after Parot and Clottes 1975, 391 fig. 9,2-4)

2

1

Shifting Meaning and Value through Imitation in the European Late Neolithic 19

Pl. 3. 1. Late Neolithic imitation of a socketed metal axe from the site of Chalain 3 in the French Jura (Musée de Lons-le-Saunier; redrawn by Judith Rasson after Billamboz 1978, 163 fig. 71,1); 2. Late Neolithic imitation roe deer metapodial awl carved from red deer metapodial from a multiple burial at the Vidon Rockshelter in France (redrawn by Judith Rasson after Roussot-Larroque 1982, 127 fig. 2,1)

1 2

Alice M. Choyke20

Pl. 4. 1. Imitation red deer canines with spondylus beads in a necklace from a young woman’s grave at the late Neolithic Hungarian site of Polgár 6 (photograph by Karoly Kozma); 2. Real red deer canines with large spondylus beads in a necklace from an older woman’s grave at the Late Neolithic Hungar- ian site of Polgár 6 (photograph by Karoly Kozma)

1

2

Shifting Meaning and Value through Imitation in the European Late Neolithic 21

Pl. 5. 1. Projectile point imitation used as amulet from the Middle Chalcolithic Boleráz site of Gy!r–Szaba- drét-domb (photograph Judith Rasson); 2a. Traditional Sami antler lasso loops (photograph Alice Choyke); 2b. Modern Sami lasso loop from blue plastic (photograph Alice Choyke)

1

2a

2b

What lies behind ‘Import’ and ‘Imitation’? 23

Abstract

Two cases from the 3rd millennium BC, which from a certain point of view may be treated as examples of ‘import’ and ‘imitation’, are discussed. A com-mon manifestation of both cases is the presence of artifacts in one culture that are related to an entirely different cultural group (or even several of them). A detailed analysis of both cases, however, in particular the exploration of their cultural and social contexts, leads to the conclusion that in each case the items underwent a different chain of transformations of senses and values.

!"#$%"

& '()((* +,'-.(.$(/'0 +1) 1,2)+-, # 333 (,'. +4 5. "., 0-* 6"#.%4154 %47.(/ 6.(, 84#9:05.(* 0- 28,-:)+, *%248(*1 () *%*();*<. =)9):/5,% 284014% 1 464> 1,2)+-)> ? 5)015*'(/ 1 4+5*< -.:/(.8* )8("@)-(*1, 0-* 1*+54'0(/'0 +4 #41'*% *5A4B -.:/(.854B 98.2, ()64 5)1*(/ +4 -*:/-4> 98.2). C"():/5,< )5):*# 464> 1,2)+-*1, #4-8"%), +4':*+7"550 B> -.:/(.85,> () '4;*):/5,> -45("-'(*1, 28,14+,(/ +4 1,'541-., D4 1 -4754%. 1,2)+-. ;* 28"+%"(, 284>4+,:, :)5;$9 8*#5494 84+. (8)5'@48%);*< B> #5)E"550 * ;*554'(*.

F"8A,< 1,2)+4- – ;" 5)015*'(/ 24'.+., @48%):/5* 8,', 0-494 () 485)%"5();*0 1,#5)E)$(/ #1‘0#-, # -.:/(.84$ -.:0'(,> )%@48 1 24>41)550> 0%54B -.:/(.8, 1 '("241*< () :*'4-'("241*< #45)> G>*+54B H1842,. I)-,< 24'.+ 2415*'($ E.7,< (8)+,;*0% 0%54B -.:/(.8,. J'* 1*+4%* 46‘?-(, ;/494 (,2. #5)<+"5* 1 '.%*75*< #45* %*7 +14%) -.:/(.8)%,, 0-* 284;1*():, 4+54E)'414 +"0-,< 2"8*4+. KE"1,+54, ()-,< 24'.+ '1*+E,(/ 284 -45()-(, %*7 46D,5)%, 464> -.:/(.8.

C8.9,< 1,2)+4- 28"+'()1:"5,< 5)015*'($ ()- #1)5,> 9.+#,-*1 # V-24+*65,% 4(1484%. I)-* 9.+#,-,, #846:"5* 94:415,% E,54% # -*'(-, () 849., 1*+4%* 1 -.:/(.8)> L"5(8):/54B H1842, # 24E)(-. 5"4:*(.. M8454:49*E54 +4194 1*+4%* 145, 1 -.:/(.8* N)81) 5) 2*1+"554%. '>4+* O):(,-,, +" 145, 6.:, #846:"5* 1,-:$E54 # 6.8A(,5.. I*:/-, 1 )8"):*, 0-,< 284'(095.1'0 1*+ P+)5'/-4B #)(4-, +4 Q)(1*B 5)% 1*+4%* %)<'("85*, +" 9.+#,-, # V-24+*65,% 4(1484% %)'414 1,846:0:,'0. R8*%

#5)>*+4- # 2)%‘0(4- -.:/(.8, N)81), ;"< (,2 )8("@)-(*1 (#846:"5,> (*:/-, # 6.8A(,5.) 1*+4%,< 5) 2)%‘0(-)> -.:/(.8, -.:0'(,> )%@48, -.:/(.8, A5.8414B -"8)%*-,, -.:/(.8, !7.E"14, -.:/(.8, =:4() () -.:/(.8, +#1*5424+*65,> -.6-*1. L0 (8)+,;*0 6.:) 284+417"5) 5)'":"550% -.:/(.8, -.:0'(,> )%@48. J -.:/(.8* +#1*5424+*65,> -.6-*1 46,+1* ("5+"5;*B 46‘?+5):,'0 # 9.+#,-)%,, #846:"5,%, (.( ()-47 # -)%"50 (1-:$E54 5)2*1-4A(415494 -)%"50) () %"():. (1-:$E54 #4:4(4). F*':0 -.:/(.8, +#1*5424+*65,> -.6-*1, 5) 24E)(-. 33 (,'. +4 .5."., 9.+#,-, 8)2(414 #5,-)$(/. = 49:0+. 5) 8*#5* -.:/(.85* -45("-'(, 1)7:,14 1'()541,(,, E, %):, 9.+#,-, 1 -4754%. # 5,> (" 7 ')%" #5)E"550.

K'46:,1. .1)9. 28,+*:"54 #%*5)%, 28, 0-,> 2"81*'5) (1,>*+5)) '(8.-(.8) 46‘?-() 6.:) 1*+(4895"54$ * (*:/-, +"0-* ":"%"5(, 241(48"5* (+:0 28,-:)+., #8)#-, -.:/(.8, -.:0'(,> )%@48 1 0%54B -.:/(.8,) () #%*5* ;*554'(* 28"+%"(*1 #) 8)>.54- +4+)5,> +4 (,241,> 28"+%"(*1 ":"%"5(*1 (+:0 28,-:)+., 9.+#,-, # 6.8A(,5.).

Introduction

Right at the very beginning we would like to stress that the terms ‘import’ and ‘imitation’ used in the title are purely conventional. That which in the ma-terial sphere is perceived as an identity or similarity of forms, techniques and/or materials, is one of the signs of a phenomenon being an object of intensive studies by cultural anthropologists and prehistorians, namely, the cultural contact, or more specifically, its material aspects. As an analytical key, we use the concept of metaphoric and metonymic transforma-tions formulated by E. Leach (1976). Under this con-cept, signs and symbols (and, consequently, objects that are their carriers) undergo multiple transforma-tions during a transfer. In this paper we wish to show what chain of formal and semantic transformations accompanied the movement of certain ideas, materi-ally represented in the form of different goods.

What lies behind ‘Import’ and ‘Imitation’?

Case Studies from the European Late Neolithic

Janusz Czebreszuk & Marzena Szmyt

Janusz Czebreszuk and Marzena Szmyt24