Argumentum ad nauseam

Transcript of Argumentum ad nauseam

Argumentum ad nauseam

Edwin Coleman

1 Introduction2 Division3 An Incoherent Tradition continues : introducing argumentum ad nauseam4 Attempted progress : formal dialectic, pragma-dialectics, neo-rhetoric 5 No-theory theory6 The Book of Objections7 Conclusion

1 Introduction

2 Division

3 The Incoherent Tradition continuesAristotle's theory, first versionThe traditionIts incoherenceContinuation : introducing argumentum ad nauseam

4 Progress, anyone?Dialectic, Formal dialectic, pragma-dialecticsWhat fallacies areWhat fallacies there areWhy this is badly wrongNeo-rhetorical adjustments are inadequate

5 The No-theory TheoryCriticisms of Cummings' arguments that theory should be eschewedDiscussion of Cummings' suggestions for progress

6 Theory E : The Book of ObjectionsWhy we need a theoryWhat fallacy isWhat fallacy is notWhat kind of theory can we haveWhat fallacies there are

7 Conclusion

argumentum ad nauseam edwin coleman 1

1 IntroductionIn his 1970 monograph, Hamblin showed very convincingly that extant accounts of fallacy were shockingly bad ; he complained that we really have no theory of fallacy ; and he set to work to make one. Unfortunately, in the many years since then, the situation has barely improved. Some are suggesting that it cannot be.

My thesis is that, against the weight of historical evidence and despite the shortcomings of current attempts, we need a theory of fallacy, and we can have one : but we'll need to revise our ideas of both fallacy and theory to do so. Better sense can be made of the idea of fallacy, but to do requires several radical moves.

Firstly, remove the nonsense : many traditional fallacies must be recognised to be no such thing, confused and inapplicable definitions must be given up, and invented oversimplified “examples” must be banned from discussion. Good but invalid arguments must be fully accepted.

Secondly, revise the aim : hankering after a theory of fallacy must be put aside, or better, the notion of theory made wide and genuinely informal. In particular, dialog logic and neo-rhetoric must be recognised as insufficiently radical advances on the standard account.

In the future we need also to recognise reality : the forms which rational discourse takes must be seen in all their variety and specificity. For example, we must stop abstracting from the written character of a lot of important discourse.

I'm giving this talk about fallacies because GP circulated an advertisement for an informal logic conference, which I took at first as meaning an (informal logic) conference, but soon realised would be an informal (logic conference). This kind of syntactic ambiguity is what I call a thin captain's biscuit, and it is often claimed to be one of the primordial kinds of fallacy ; we'll see about that later.

argumentum ad nauseam edwin coleman 2

2 Division I'll be discussing five theories of fallacy. They are

A Aristotle's theorythe first, and still worth discussion

B The Standard Account [textbooks]the nonsense commonly found in text-books, supposedly developed from A

C The Amsterdam theory [van Eemeren and Grootendorst etal]the radical alternative proposed by pragma-dialectics

D The no-theory theory [Cummings, and others]arguments against the possibility of a good theory

E The Coleman theorythe good theory we need to create

Firstly, I'll outline the faults of each of the three theories A, B and C.

Secondly, I'll discuss some arguments that we should abandon seeking a theory at all.

Thirdly, I'll argue that despite the bleak situation, we need to keep after a good theory. I shall suggest what are the main features for the theory we should be trying to develop.

As an illustration I'll be using the category of argumentum ad nauseam. You may be unfamiliar with this label, but I'll explain it shortly.

argumentum ad nauseam edwin coleman 3

3 The Incoherent Tradition, continued

The traditional discourse of fallacy is generally said to start with Aristotle, though this is part of the usual unfair ignoring of the contributions of the Sophists to intellectual history. Aristotle's concept of fallacy is not entirely coherent, especially not if taken away from the context of his discussion, which was the peculiar Athenian debating practice with which he is concerned.

He discussed fallacies in several works, not entirely consistently. Here is a simplified version of his theory. A less simple one is discussed later.

Aristotle's theory, simple version – Theory A[a] Fallacy is not defined [actually, he has no word for fallacy], but[b] there are twelve kinds[c] six fallacies are “due to language”, six are “outside language”[d] they are

equivocation amphiboly form of the expression accent composition division

andbegging the question non-cause as cause accident consequentsecundum quid many questions

Some of these are familiar, and others may sound familiar, but we shall see that not all is as it seems here. Aristotle does not discuss AAN under any name.

The Standard Account, Theory BAfter Aristotle, major changes waited till the scientific revolution, at which time numerous new “fallacies” were “discovered” and added to the list. More recently, ever more new “fallacies” have been discovered, for example in statistical reasoning. There's a book detailing hundreds of “historian's fallacies”, Bentham wrote another book about political fallacies, Whitehead claimed that most of western philosophy consists in ways of committing the fallacy of misplaced concreteness, and so on. Nowadays you are likely to be told that there are all sorts of fallacies – a recent survey of 20 text books found eighty-nine different fallacies discussed in them. So-called “arguments ad” figure strongly in such lists from Locke onward, so I will illustrate the idea by introducing my own “discovery”, argumentum ad nauseam.

Aristotle's discussion includes argumentum ad hominem, the tactic of opposing an argument by attacking its propounder [though it's not one of the canonical twelve]. It was Locke who took over from the PortRoyal logic the identification of another tactic which he dubbed argumentum ad verecundiam, otherwise known as argument ad auctoritas or argument from authority. This consists in presenting the character of its propounder as reason for accepting a claim. Since then many other “arguments ad” have been discovered, such as argumentum ad misericordiam or appeal to pity ; argumentum ad ignorantiam, appeal to ignorance, meaning arguments like [you can't disprove P, so P ] ; ad populum, appeal to common opinion ; ad baculum, the stick , i.e. threat ; ad superstitionem, ad imaginationem, ad invidiam – envy, ad crumenum – purse, ad metum – fear, ad

argumentum ad nauseam edwin coleman 4

fidem – faith, ad socordiam – weak-mindedness, sad uperbiam, ad odium, ad ludicrum, ad captandum vulgus, ad fulmen, ad vertiginem – dizziness.

I have taken this list from Hamblin, who remarks “we feel like adding : ad nauseam – but even this has been suggested before.” He refers us to Bradley. Hamblin gives no gloss on what AAN might be, while Bradley seems to have meant that a line of argument, which he declines to give, would have wearied his reader too much. I consulted Google, in case others have taken up Hamblin's hint, and indeed there numerous pages on the 'Net claiming that AAN is the tactic of repeating something until it is accepted. I can't find out how this first got into the lists – it's not in any text-book list I've seen. Actually, one blogger wants to use the phrase for the tactic of objecting to something on the ground it has been said too often ! (Although that person thinks it should be argumentum ad nauseum.)

There are indeed such tactic as these but I think they can be better named, and in any case I want to use AAN for something else, namely the tactic of rebutting a claim by claiming that it is offensive.

Examples :

John Brogden said 'HC is a mail order bride', that is offensive, so Brogden must go.Fraser Gehrig said that some other footballer is a biblebashing c***, that is offensive, so he must apologiseDavid Irving denies the Holocaust, that is offensive to Jews, so Irving must not be allowed into AustraliaSocrates says he's on mission from the gods, that is impious, so he should die.X says p, but C[p], so f[X]

The Socrates example shows us 'blasphemy' as a form of AAN: X says P, p offends God, so X must be burned at the stake.

Accusations of racism, sexism etc are also AAN : X says p, p is offensive to [insults] a certain group of people, so X must be pilloried

AAN may fruitfully be compared with adhomination :

X says p, but X is C, so f[p]Howard says the war was right, but he is a war criminal, so it wasn't.

In both cases we start from X says p. But adhomination has for second premise a characterisation of X and a concluion about the status of p, whereas AAN has for second premise a characterisation of p, with a conclusion about the status of X.

So my latest contribution to the tradition is the discovery of AAN.

The incoherence of this tradition Hamblin pointed out in 1970, to general acceptance, that existing accounts of fallacy were extremely deficient in many ways. Although Hamblin criticised Aristotle's account, the critical part of his book is mainly a tracing of the genealogy of current text-book accounts of fallacy, which he calls the Standard Account. According to it, [1] a fallacy is an argument that seems valid but is not ;l (there are many alternative definitions too but none are nay better than this, supposedly descended from Aristotle)[2] there are a certain number of fallacies, somewhere between 12 and 24 in most versions – they all have a different list, but generally include most of Aristotle's, a few arguments ad, and a few others ;

argumentum ad nauseam edwin coleman 5

[3] what's wrong with a given fallacy is usually not made clear ; often it boils down to being invalid ; often makes no sense - for example, begging the question is always a problem since it is not invalid ;[4] many examples given do not really exemplify the fallacy they are said to ;[5] some supposed fallacies are not even arguments, others are faults in premises, contrary to the stated criterion for fallacy ;[6] there is an uncritical acceptance that things claimed to be fallacies must be so, and of traditional examples whether good or not ;

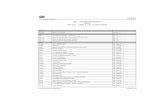

It is difficult to convey briefly just how awful the presentations of theory B are.A short example off the 'Net may give the flavour.

Typical textbook treatment of AAN, if it were done, might say something like this :someone who argued [Brogden said H and H is a racist remark so Brogden deserves ignominy] would be committing a fallacy because the premises might be true and the conclusion false, for example if Brogden had an unusual misunderstanding of mail order business practices. However, such a move can sometimes not be fallacious because racists do deserve ignominy.

But in fact AAN is not a fallacy, although it is a frequently objectionable move.

Hamblin complained that we don't really have a theory of fallacy, and that's why the SA is so bad.

The main questions which the SA fails to answer properly arewhat is a fallacy?what kinds are there?why are they bad ?can we give real examples ?

argumentum ad nauseam edwin coleman 6

4 Progress, anyone?What's changed in 35 years ? Text-books are pretty much unchanged : Hamblin might never have lived to judge from them. But there have been some attempts in the literature to make a better theory.

Formal dialectic and the Amsterdam solutionHamblin himself observed that some of the nonsense derives from ignoring the kind of reasoning with which Aristotle had actually been concerned, namely certain riutualised debating contests with a Questioner and an Answerer – a dialog in fact. So he started work on a branch tradition of formal dialectic. The idea is to lay down a set of rules for dialog games like those Aristotle was concerned with, and to interpret fallacies in their light. This has obvious merits in making some sense of begging the question and many questions – make it clear that there is a questioner !

There are several well-known theories developed in this way – Krabbe&Barth, Woods&Walton, for example ; but the most interesting is vanEemeren&Grootendorst's pragma-dialectical theory. It goes like this.

Theory C – the Amsterdam theoryArgumentation concerns critical discussion between two parties aimed at resolving a difference of opinion. Such dialogs are subject to ten rules. A fallacy is any breach of one of these rules. This definition has several merits : it is simple and definite ; it is comprehensive ; and it has founded a progressive, or at least impressive, research program. The rules in question are :

[1 freedom] Parties must not prevent one another from putting forward standpoints or casting doubt on standpoints.[2 burden of proof] A party who puts forward a standpoint is obliged to defend it if asked to do so.[3 standpoint] A party's attack on a standpoint must relate to the standpoint that has indeed been advanced by the other party.[4 relevance] A party may defend his or her standpoint only by advancing argumentation related to that standpoint.[5 unexpressed premise] A party may not falsely present something as a premise that has been left unexpressed by the other party or deny a premise that he or she has left implicit.[6 starting point] No party may falsely present a premise as a starting point, or deny a premise representing an accepted starting point.[7 argument schemes] A standpoint may not be regarded as conclusively defended if the defense does not take place by means of an appropriate scheme that is correctly applied.[8 validity] The reasoning in the argumentation must be logically valid or capable of being made valid by making explicit one or more unexpressed premises.[9 closure] A failed defense of a standpoint must result in the protagonist retracting the standpoint, and a successful defense of a standpoint must result in the antagonist retracting his or her doubts.[10 usage] Parties must not use any formulations that are insufficiently clear or confusingly ambiguous, and they must interpret the formulations of the other party as carefully and accurately as possible.

The definition of fallacy as any breach of a rule for CD has the merit of simplicity, but few others : although it handily accounts for begging the question via Rule 6, it includes much wrongly, leaves aside much wrongly, and often gives the wrong reason for our negative verdict on what it does rightly cover. As an account of

argumentum ad nauseam edwin coleman 7

fallacy it is not satisfactory because its coverage is wrong, and it retains many wrong diagnoses from the standard account. For example, it counts adhomination as fallacy, which it is not ; it does not include [because of the validity rule] generalising from tiny samples, which is a fallacy ; it explains the fallacy of division wrongly as failure of validity when it is a failure of truth; etc. It calls fallacy both tu quoque and appeals to authority, but they are not ; it assumes falsely that only a valid argument can be good ; it calls unclarity a fallacy, it lumps various fallacies such as sampling faults under the hopelessly vague description “incorrectly applying an argument scheme”. What's more, despite its apparent profligacy there are numerous fallacies it ignores – because it assumes that argumentation only goes on in spoken dialog it cannot even begin to cover fallacies dependent on the medium of expression, in particular anything peculiar to written argumentation -though this is a criticism that I would make of virtually every writer on the subject.

Theory C has been criticised by many people for its narrow focus on one kind of speech interaction. Walton has long advocated recognising and analsysing a variety of kinds of dialog, and recently the official position Amsterdam has shifted to recognise certain rhetorical aims of discussants as legitimate, to add to the theory an account of “strategic manouevering” ; but this is at the cost of recognising that this manouevering may go awry through the commission of – guess what - “what used to be called fallacies”. This change can also be seen as response to criticism from a number of exponents of rhetorical approaches to argumentation, who argue that dialectic is inadequate tot he actual process of argumentation which is highly dependent on contextual factors, in particular, just who the discussants are. They also emphasise that much argumentation is not really a dialog but more in the nature of a speech to an audience, and much is made of the construction of audiences in the process of argumentation. They like to construe traditional logic as concerned only with the products of argumentation, dialectic with its procedures, but the rhetorical view with the process itself.

However, so far this has not really produced a theory, indeed Tindale suggests that it should not be expected to. This idea has been argued at some length by Cummings recently, so let us turn to the no-theory theory.

argumentum ad nauseam edwin coleman 8

5 Theory D, the no-theory theoryArguments against the very idea of a theory of fallacy have been suggested before, for example by Massey ; Hamblin mentions others prior to his book. Recently Louise Cummings has argued such a case at length.

Cummings argues that aping science by seeking a fallacy theory which is complete, objective and certain will inevitably require the adoption of a “metaphysical position” and hence produce incoherence. She tries to show this by argument and by example, neither being very convincing to me.

Cummings' argument is twofold. One line is the repeated claim that reason cannot hope to fully understand itself, whereas science can hope to fully understand nature – nature thought of as external to the scientific endeavour. But this argument relies on the unjustified assumption that nature does not include science and rationality. Moreover, this idea that there is a problem about reason examining itself is hogwash, no better than the claim that one cannot investigate eyesight visually, or the english language if you are monolingually english yourself or humanity, if you are human.

Cummings also presents a more specific version of the same idea: attempting to meet the ideal of a scientific theory inevitable produces unintelligible accounts. The ideal criteria, she claims, are completeness, certainty and objectivity, and she tries to show that each of these is productive of unintelligibility. However, none of her arguments convinces me. The most developed is the completeness argument.It's true that scientistic philosophers often write glibly about some “completed physics” which would make other disciplines otiose. If there is such a thing, it will have to do everything that these superseded investigations try to, including axiological enquiries such as logic. No completed physics will allow discarding the concerns of logic for the fatuities of academic psychology or its new-fangled avatar, so-called cognitive science. But in any case, Cummings' attempt to show that a completed theory of rationality is impossible, because attempting it produces unintelligibility, fails. Her argument is that this inevitably requires adopting a metaphysical standpoint because the enquiry both presupposes rationality and examines it. I've already indicated why this does not follow. Nor does she explain why a metaphysical standpoint must produce unintelligibility - though her later discussion of Wittgenstein perhaps shows why she thinks so.

Cummings' second argument is the example of Woods and Walton trying to characterise and diagnose argumentum ad ignorantiam. (You can't disprove p, so p.) Her complaint is that they claim this to be an intrinsically dialectical category, and yet, according to Cummings, it presupposes a monolectical inference schema – a non-dialectical element. I agree that it does (there is no proof of not p, so p), but all that shows is that if they think only dialectical concepts suffice for the characterisation, they are wrong. I'm not sure that they do claim that, and in any case one need not – expanding the conceptions of logic and argument to dialectical contexts does not have to be at the expense of concepts developed for monolectical cases.

The best refutation of theory D will be to produce a good theory of fallacy. So let us.

argumentum ad nauseam edwin coleman 9

6 Theory E : The Book of Objections

Why we need a theoryDo we need the term 'fallacy', or some concept of fallacy ?Yes, we do. Consider the recent report about systematic differences in IQ between males and females. [ref?]One could just AAN this, as many will, but that is a weak response. There are various faults of various kinds in the report. Some of them are characteristic of modern investigation, viz. they are of a statistical nature. They should be distinguished and compared with their like elsewhere. A critical response to such a text needs a battery of concepts ; just hunting out invalidities won't get you anywhere.

From this starting point, the idea of critical response, we can develop a useful concept of fallacy, and from that a good theory.

What fallacy is'Fallacious' is a term that may fill the V slot in the schema The F of T is V because Rwhich expresses rational criticism.

'Fallacious' is a charge which applies to persuasive/argumentative texts and it implies a [grievous?] fatal flaw in the argumentation. It must be complemented by a choice of R predicating from the range of canonical fallacies such as BQ, AC, FD etc.

A fallacy makes an argument bad. Often a fallacy is a kind of bad argument.

Begging the question is a mistake or tactic – it can be either – which is always fatal to argumentation, and I suggest we should reserve the term fallacy for this and its like.

What fallacy is notAn argument is not a fallacy merely because it is invalid.All inductive arguments are invalid, but not all of them are fallacious.

A non-demonstrative argument is more or less strong. It is not a fallacy merely because it is weak. Ad hominem argument is generally weak, often very weak. But it is not a fallacy. If an ad hominem argument is bad, it is because it is completely irrelevant. It's the irrelevance not the adhomination that causes the badness.(This is just the converse of my long argument about argument from authority).

To label an argument ad hominem is to make a criticism of it, usually ; but there are many kinds of criticism.

Contrary to recent writers reluctant discovery of kinds of argument that are only “sometimes a fallacy”, like AAA, any such kind is necessarily not a fallacy but a plausible argument that can be weak or strong. There are a number of books that divide up into deductive, inductive and fallacy. This is almost right, except that 'inductive' is always taken much too narrowly. So a term like 'plausible' is needed instead.

Thus there are three grades of argumentative strength : validity, plausibility and fallacy. I would like to say probability in place of plausibility but that would give the false impression that I subscribe to the fallacy I call the canonical shuffle. In this move, after treating deductive arguments one first recognises there are good

argumentum ad nauseam edwin coleman 10

but invalid arguments, calling them inductive ; one later considers only statistical arguments inductive, and explicitly or more often by implication calls all other kinds of argument fallacy. That puts the division in the wrong place. The key observation for theories of both good and bad argument is that there are many kinds of argument, not two.

What kind of theory can we have ?What kind of theory of fallacies do we really need ? The kind of theory we can't have, but after which the formally inclined hanker, is an axiomatic formal theory. It's not going to happen that we can give a neat definition, or simple set of axioms which define fallacy, a basic set of forms which lists the types of fallacy, and a deductive demonstration that each of the latter is one of the former. But so what ? Not every theory worth the name has that character. The atomic theory, for example, is a great theory but it arguably has only one of those three marks. Freud's theory has been widely dismissed on a variety of grounds, but not because it is not a theory – rather, it's a bad theory, or an unscientific theory, or an unfalsifiable theory. It's good example of a theory even if it is not an example of a good theory.

I think that the model that should be adopted is the catalog, dictionary or encyclopedia. Parallel to works like Dupriez's Dictionary of Literary Devices – 2000 entries from abbreviation to zeugma - we need The Book of Objections, which lists alphabetically all the large number of possible kinds of criticism which can be made of argumentative texts. Some of the features to which objection can be made deserve to be called fallacies because they always make an argument bad. Other objections need other labels ; all these arguments ad, for starters, none of which are fallacies.

Now I might seem to be advocating more of the rubbish you find so commonly on the 'Net. “Mr X's list of the fallacies” - there are lots of them. But it might be a mistake to assume that because many lists of fallacies are rubbish, that any list of fallacies must be rubbish. I say it's not the listing system, its the listers at fault. The reason 'Net lists of fallacies are so bad is that they are uncritically copied from one another and from the very bad literature which Hamblin criticised. They have no coherent concept of fallacy, and they repeat all the usual rubbish about adhomination etc. Horrifying examples can be found on every US university website.

The Book of Objections is different ; it deploys a coherent set of critical categories among which fallacy has a secure but not bloated place. Its entries are nuanced descriptions of the various factors which work for or against the effectiveness of a particular trope, and as does Dupriez', its entries not only give real examples from pre-existing texts, they constantly compare and contrast different tropes via extensive cross-referencing. It includes an analytical index and an annotated bibliography in which all the errors in the other treatments are exposed and refuted.

What fallacies there are [!]How many fallacies are there, and what are they ? Some old favourites will have big entries in the Book of Objections. Begging the question, false dichotomy, affirming the consequent – all these will be listed as fallacies. But others of the usual suspects, such as all the arguments ad and argument from analogy, will be listed as plausible arguments subject to characteristic kinds of weakness and flaw.

Some old muddles will have to be cleared up for the Book of Objections. Thus, we will have to give a suitable name to the fallacy that Aristotle called composition or

argumentum ad nauseam edwin coleman 11

division – what I called the thin captains' biscuit fallacy – and point out that most people use the term fallacy of composition for something completely different. It may be that we also need a new term [not fallacy, but close to it] for the kind of problem that composition exhibits : such an argument [every ingredient in this stew is delicious, so this stew is delicious] rests on the false assumption that what is true of all the parts of something is always true of the whole. But really, the assumption that what is true of the parts of X is true of X is very often true. So it's really a dangerous assumption : should that be called a fallacy ? Compare this with false dichotomy, where the charge is always that in the case at hand, there are unacknowledged alternatives – not that there are no strict dichotomies.

New fallacies can be discovered. Is that why I introduced argumentum ad nauseam, you ask ? Not quite, AAN is not a fallacy. It is merely a discursive criticism which is often highly objectionable itself, but may be good. But here is a real example : in geometrical arguments, a common fault in the reasoning is reliance on a misleading diagram. This has not been listed as a fallacy although until recently diagrams have generally been regarded as logically suspect, and have rarely been discussed well.

In fact there are many new fallacies waiting to be named once the final step is taken away from the SA. The rhetorical turn needs intensifying to take into account the media of expression of discourse. Ironically, in this again I am preceded by Aristotle who pointed out that his category of accent, which in fact can't occur in English, only happens in written argumentation not spoken. Written argumentation, like written text generally, has many important properties not shared with speech and it's time attention was given to fallacies dependent on medium. One might consider the fallacy of authorial intent, the fallacies of charity, the fallacy of assuming a single author etc etc. (These are merely hints for the future.)

The preparation of the Book of Objections, and its companion volumes in the Library of Criticism, will be a large task and indeed it will need to be constantly extended as new forms of expression become available. Perhaps I should go back to Bradley's meaning for argumentum ad nauseam after all ...

argumentum ad nauseam edwin coleman 12

7 ConclusionHamblin exposed the unacceptable Standard Account of fallacy as confused and superficial, full of obvious falsehoods and contradictions. Recognising that abstracting from the dialectical was a source of this, some writers put forward dialectical accounts of fallacy ; the most radical is the pragma-dialectical theory, but even it has the same faults of misdescription and conceptual confusion. Neo-rhetorical accounts of argumentation have not produced a theory, and it is now being argued again that we should not seek a theory.

I argue that this pessimism is unwarranted ; we can produce a good theory but to do so, we need to clarify both fallacy and argument by correcting several traditional mistakes. The root problem is inconsistency about the notion of good argument. We also need a different notion of 'theory'. Thus my main points are these.

[1] Validity is not necessary for goodness.[2] Many so-called fallacies simply are not fallacies – the recent invention of part-time fallacies is a hopeless attempt to hold on to a bad account. [3] 'Fallacy' has been used inconsistently. No trick can also be a mistake.[4] Let's use 'fallacy' for bad kind of argument.Let's also be a more accurate about what makes a specific argument [kind] bad.[5] 'Fallacy' is a criticism, more specifically an objection. A criticisms is an evaluation ; a rational criticisms offers justification ; there are many kinds of criticism. We need more terms for them.[6] The right model for a treatise on fallacy, the Book of Objections, is the Dictionary of Literary Devices. It includes fallacies but is not limited to them.It is an alphabetical list.It includes fallacies but is not limited to them.BQ, FD, AC etc are explained as bad kinds of argument.AAN etc are explained as possibly objectionable discourse tactics.Real examples are given.There is an index and an annotated bibliography.It has a high level of internal cross-reference.[7] New fallacies need to be named that are specific to different media of expression.

But that is for the future.

argumentum ad nauseam edwin coleman 13

Five theories of Fallacy

A Aristotle's theorythe first, and still worth discussion

B The Standard Accountthe nonsense commonly found in text-books, supposedly developed from A

[textbooks]

C The Amsterdam theorythe radical alternative proposed by pragma-dialectics

[van Eemeren and Grootendorst et al]

D The No-Theory Theoryarguments against the possibility of a good theory

[Massey, Cummings, and others]

E The Coleman theorythe good theory we need to create

argumentum ad nauseam edwin coleman 14

Overview

1 Introduction

2 Division

3 The Incoherent Tradition continuesAristotle's theory, first versionThe traditionIts incoherenceContinuation : introducing argumentum ad nauseam

4 Progress, anyone?Dialectic, Formal dialectic, pragma-dialecticsWhat fallacies areWhat fallacies there areWhy this is badly wrongNeo-rhetorical adjustments are inadequate

5 The No-theory TheoryCriticisms of Cummings' arguments that theory should be eschewedDiscussion of Cummings' suggestions for progress

6 Theory E : The Book of ObjectionsWhy we need a theoryWhat fallacy isWhat fallacy is notWhat kind of theory can we haveWhat fallacies there are

7 Conclusion

argumentum ad nauseam edwin coleman 15

Theory A - Aristotle's theory, simple version

[a] Fallacy is not defined [actually, he has no word for fallacy], but

[b] there are twelve kinds

[c] six fallacies are “due to language”, another six are “outside language”

[d] they are

equivocation amphiboly form of the expression accent composition division

andbegging the question non-cause as cause accident consequentsecundum quid many questions

argumentum ad nauseam edwin coleman 16

Theory B – The Standard Account

[1]a fallacy is an argument that seems valid but is not (there are many alternative definitions too but none are any better than this, supposedly descended from Aristotle)[2] there are a certain number of fallacies, somewhere between 12 and 24 in most versions – they all have a different list, but generally include most of Aristotle's, a few arguments ad, and a few others ;[3] what's wrong with a given fallacy is usually not made clear ; often it boils down to being invalid ; often makes no sense - for example, begging the question is always a problem since it is not invalid ;[4] many examples given do not really exemplify the fallacy they are said to ;[5] some supposed fallacies are not even arguments, others are faults in premises, contrary to the stated criterion for fallacy ;[6] there is an uncritical acceptance that things claimed to be fallacies must be so, and of traditional examples whether good or not.

This theory needs to be seen to be believed : for example, at http://www.colorado.edu/PWR/writingtips/23.html

argumentum ad nauseam edwin coleman 17

Writing Tip #23: Types of Fallacies

Arguments can be logically invalid even though the conclusion may be true; in some cases, a conclusion can be true by coincidence. Furthermore, the statements (known as premises) that combine in a syllogism to yield the conclusion may not be true. For a syllogism to be conclusive, the premises must be true and the form must be valid. The resulting conclusion cannot be disputed. In most cases, however, our arguments are persuasive rather than conclusive because they leave room for further argument.

Nonetheless, arguments aim for conclusion. Remember that correlation is not cause and effect. For example, scientists recognize that smoking and lung cancer correlate positively at a high level, but scientists have yet to prove that smoking causes cancer. Thus, an argument could not conclude that smoking causes lung cancer, or conversely, that a person who does not smoke will not get lung cancer.

Below is a list of logical fallacies, which may be difficult to detect. A solid argument will not contain any of these fallacies.

1. Appeal to symbols (I wrap myself in the flag to demonstrate my patriotism). 2. Appeal to ignorance/unseen evidence (He's guilty because he had a gun we couldn't find). 3. Appeal to illogical premises (It's OK to cheat, everybody does it in this class). 4. Appeal to what's known (We know Germans like big cars, they make Mercedes). 5. Red herring (She's rich. Did you hear her children own big houses and boats). 6. Appeal to false authority (99% of family dentists say regular brushing is good; use Crest). 7. Ad hominem (attacks character) (Of course you support euthanasia, your parents are dead).

includes name calling: My opponent is a liar.

includes prejudice: Women just can't be good stock brokers.

includes guilt by association: She's a feminist so her ideas must be radical.

8. Straw person/straw man (You may think it's cheaper to cut trees to make sacks, but I don't). 9. Begging the question (We should not give high grades because they will reward poor students

as well as good ones). 10. Complex questions (When did you stop speeding in your sports car?). 11. Oversimplification (Love it or leave it!). 12. Equivocation (He's so successfulsuccessful had many meanings). 13. Post hoc, ergo propter hoc (After this, therefore because of that) /Correlation

(I ate pizza and got a stomach ache, so pizza must not be good for us).

14. Slippery slope (We don't dare provide more scholarships. We'll be supporting the whole country if we do).

15. Generalization (The taxes are much too high).

includes pars pro toto (assumes what is true for part is true for all: That banker didn't pay his taxes on time. Bankers don't pay their taxes on time.) includes the opposite of pars pro toto (contradicting evidence is withheld: He was told to pay a penalty for late taxes. But, he paid his taxes on time; the mail was late).

16. Faulty analogy (Well, the jet model worked in the wind tunnel, so that plane will fly). 17. Non sequitur (Pete likes to drink milk, so Jennifer is sure to like malts ). 18. Irrelevant reasons (I should not get below a B in this class because I worked hard).

[http://www.colorado.edu/PWR/writingtips/23.html]

argumentum ad nauseam edwin coleman 18

Argumentum ad nauseam [1]John Brogden said 'HC is a mail order bride', that is offensive, so Brogden must go.

[2]Fraser Gehrig said that Shane Parker is a biblebashing c***, that is offensive, so he must grovel.

[3]David Irving denies the Holocaust, that is offensive to Jews, so Irving must not be allowed into Australia.

[4]Socrates says he's on mission from the gods, that is impious, so he should die.

The scheme is X says p, but C[p], so f[X]

The Socrates example shows us 'blasphemy' as a form of AANs: X says p, p offends God, so X must be burned at the stake.

Accusations of racism, sexism etc are also AANs :

AAN may fruitfully be compared with adhomination X says p, but X is C, so f[p]Howard says the war was right, but he is a war criminal, so it wasn't.

argumentum ad nauseam edwin coleman 19

Theory C – the Amsterdam theory A fallacy is any breach of one of these rules :

[1 freedom] Parties must not prevent one another from putting forward standpoints or casting doubt on standpoints.[2 burden of proof] A party who puts forward a standpoint is obliged to defend it if asked to do so.[3 standpoint] A part's attack on a standpoint must relate to the standpoint that has indeed been advanced by the other party.[4 relevance] A party may defend his or her standpoint only by advancing argumentation related to that standpoint.[5 unexpressed premise] A party may not falsely present something as a premise that has been left unexpressed by the other party or deny a premise that he or she has left implicit.[6 starting point] No party may falsely present a premise as a starting point, or deny a premise representing an accepted starting point.[7 argument schemes] A standpoint may not be regarded as conclusively defended if the defense dose not take place by means of an appropriate scheme that is correctly applied.[8 validity] The reasoning in the argumentation must be logically valid or capable of being made valid by making explicit one or more unexpressed premises.[9 closure] A failed defense of a standpoint must result in the protagonist retracting the standpoint, and a successful defense of a standpoint must result in the antagonist retracting his or her doubts.[10 usage] Parties must not use any formulations that are insufficiently clear or confusingly ambiguous, and they must interpret the formulations of the other party as carefully and accurately as possible.

argumentum ad nauseam edwin coleman 20

Aristotle's theory, version 2

[a] a fallacy is a failed demonstration[b] a refutation is a demonstration of the denial of a thesis[c] a sophistical refutation is a seeming refutation which is really a fallacy[d] SR's should be classified by the source of the seeming.[e] The sources are various false presuppositions about language and the world[f] hence the classification :[g] equivocation [do the learned or the ignorant learn ?]amphiboly [I wish that you the enemy may capture]form of the expression [I have ten dice, so i don't have only one, so I can't give away only one]accent [not possible in english]composition [it is true to say right now that you have been born, so it is true to say that you are born right now]division [ditto : this is not really a different category]

begging the question [p, so p]non-cause as cause [a,b..., so x&-x ; so -a]accident [Coriscus is different from Socrates, Socrates is a man, So Coriscus is not a man]consequent [this is yellow, all honey is yellow, so this is honey]secundum quid [prudence is good, prudence is knowledge of evil, so something of evil is good]many questions [which is the sea, the land or the sky?]

argumentum ad nauseam edwin coleman 21

Theory E : The Book of Objections, a volume in the Library of Criticism

[1] Validity is not necessary for goodness.[2] Many so-called fallacies simply are not fallacies – the recent invention of part-time fallacies is a hopeless attempt to hold on to a bad account. [3] Fallacy has been used inconsistently. No trick can also be a mistake.[4] Let's use 'fallacy' for kinds of bad argument.Let's also be a more accurate about what makes a specific argument [kind] bad.[5] 'Fallacy' is a criticism, more specifically an objection. A criticisms is an evaluation ; a rational criticisms offers justification ; there are many kinds of criticism. We need more terms for them.[6] The right model for a treatise on fallacy, the Book of Objections, is the Dictionary of Literary Devices. It is an alphabetical list.It includes fallacies but is not limited to them.BQ, FD, AC etc are explained as bad kinds of argument.AAN etc are explained as possibly objectionable discourse tactics.Real examples are given.There is an index and an annotated bibliography.It has a high level of internal cross-reference.

[7] New fallacies need to be named that are specific to different media of expression. The Book is not yet complete.

argumentum ad nauseam edwin coleman 22

Argumentum ad nauseam

Edwin Coleman

1 Introduction2 Division3 The Incoherent Tradition continuesAristotle's theory, first versionThe traditionIts incoherenceContinuation : introducing argumentum ad nauseam4 Progress, anyone?Dialectic, Formal dialectic, pragma-dialecticsWhat fallacies areWhat fallacies there areWhy this is badly wrongNeo-rhetorical adjustments are inadequate5 The No-theory TheoryCriticisms of Cummings' arguments that theory should be eschewedDiscussion of Cummings' suggestions for progress6 Theory E : The Book of ObjectionsWhy we need a theoryWhat fallacy isWhat fallacy is notWhat kind of theory can we haveWhat fallacies there are7 Conclusion

-------------------------------------------Argumentum ad nauseam [1] John Brogden said 'HC is a mail order bride',

that is offensive, so Brogden must go.

[2] Fraser Gehrig said that Shane Parker is a biblebashing c***, that is offensive, so he must grovel.

[3] David Irving denies the Holocaust, that is offensive to Jews, so Irving must not be allowed into Australia.

[4] Socrates says he's on mission from the gods, that is impious, so he should die.

The scheme is X says p, but C[p], so f[X]

The Socrates example shows us 'blasphemy' as a form of AANs: X says p, p offends God, so X must be burned at the stake.

Accusations of racism, sexism etc are also AANs

AAN may fruitfully be compared with adhomination X says p, but X is C, so f[p]Howard says the war was right, but he is a war criminal, so it wasn't.

argumentum ad nauseam edwin coleman 23

Writing Tip #23: Types of FallaciesArguments can be logically invalid even though the conclusion may be true; in some cases, a conclusion can be true by coincidence. Furthermore, the statements (known as premises) that combine in a syllogism to yield the conclusion may not be true. For a syllogism to be conclusive, the premises must be true and the form must be valid. The resulting conclusion cannot be disputed. In most cases, however, our arguments are persuasive rather than conclusive because they leave room for further argument.

Nonetheless, arguments aim for conclusion. Remember that correlation is not cause and effect. For example, scientists recognize that smoking and lung cancer correlate positively at a high level, but scientists have yet to prove that smoking causes cancer. Thus, an argument could not conclude that smoking causes lung cancer, or conversely, that a person who does not smoke will not get lung cancer.

Below is a list of logical fallacies, which may be difficult to detect. A solid argument will not contain any of these fallacies.

8. Appeal to symbols (I wrap myself in the flag to demonstrate my patriotism). 9. Appeal to ignorance/unseen evidence (He's guilty because he had a gun we couldn't find). 10. Appeal to illogical premises (It's OK to cheat, everybody does it in this class). 11. Appeal to what's known (We know Germans like big cars, they make Mercedes). 12. Red herring (She's rich. Did you hear her children own big houses and boats). 13. Appeal to false authority (99% of family dentists say regular brushing is good; use Crest). 14. Ad hominem (attacks character) (Of course you support euthanasia, your parents are dead).

includes name calling: My opponent is a liar.

includes prejudice: Women just can't be good stock brokers.

includes guilt by association: She's a feminist so her ideas must be radical.

14. Straw person/straw man (You may think it's cheaper to cut trees to make sacks, but I don't). 15. Begging the question (We should not give high grades because they will reward poor students

as well as good ones). 16. Complex questions (When did you stop speeding in your sports car?). 17. Oversimplification (Love it or leave it!). 18. Equivocation (He's so successfulsuccessful had many meanings). 19. Post hoc, ergo propter hoc (After this, therefore because of that) /Correlation

(I ate pizza and got a stomach ache, so pizza must not be good for us).

16. Slippery slope (We don't dare provide more scholarships. We'll be supporting the whole country if we do).

17. Generalization (The taxes are much too high).

includes pars pro toto (assumes what is true for part is true for all: That banker didn't pay his taxes on time. Bankers don't pay their taxes on time.) includes the opposite of pars pro toto (contradicting evidence is withheld: He was told to pay a penalty for late taxes. But, he paid his taxes on time; the mail was late).

19. Faulty analogy (Well, the jet model worked in the wind tunnel, so that plane will fly). 20. Non sequitur (Pete likes to drink milk, so Jennifer is sure to like malts ). 21. Irrelevant reasons (I should not get below a B in this class because I worked hard).

[http://www.colorado.edu/PWR/writingtips/23.html]

argumentum ad nauseam edwin coleman 24