Annuloaortic Ectasia and Giant Cell Arteritis

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

2 -

download

0

Transcript of Annuloaortic Ectasia and Giant Cell Arteritis

2005;80:101-105 Ann Thorac SurgCarlo Sorbara, Pierluigi Stefàno and Gian Franco Gensini

Sandro Gelsomino, Stefano Romagnoli, Franca Gori, Gabriella Nesi, Chiara Anichini, Annuloaortic Ectasia and Giant Cell Arteritis

http://ats.ctsnetjournals.org/cgi/content/full/80/1/101located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

Print ISSN: 0003-4975; eISSN: 1552-6259. Southern Thoracic Surgical Association. Copyright © 2005 by The Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

is the official journal of The Society of Thoracic Surgeons and theThe Annals of Thoracic Surgery

by on June 6, 2013 ats.ctsnetjournals.orgDownloaded from

ASCGDC

tdgw

aawcdy

l

Gaua

amtvE1[mav11ravmp

wr

A

AHs

©P

CA

RD

IOV

AS

CU

LA

R

nnuloaortic Ectasia and Giant Cell Arteritisandro Gelsomino, MD, Stefano Romagnoli, MD, Franca Gori, MD, Gabriella Nesi, MD,hiara Anichini, MD, Carlo Sorbara, MD, Pierluigi Stefàno, MD, andian Franco Gensini, MD

epartments of Cardiac Surgery, and Anesthesia, Careggi Hospital; and Departments of Pathology, and Clinical Medicine and

ardiology, University of Florence, Florence, ItalygTradatf

iar

Background. Thoracic aortic aneurysm, aortic dissec-ion and aortic valve regurgitation have been widelyescribed in patients with Horton disease, also known asiant cell arteritis. We present our midterm experienceith patients with these features.Methods. A total of 386 cases of ascending aorta and

ortic valve replacement performed for thoracic aorticneurysm and aortic insufficiency between 1998 and 2004ere reviewed. Among them 10 cases of histopathologi-

ally confirmed GAA were identified. Patients were pre-ominantly female (90%); the mean age was 74.5 � 4.6ears.Results. Eight patients (80%) showed typical annu-

oaortic ectasia, leading to significant aortic valve regur-

P

Aravci(optmaSi

TtwhagptTorpdvs

ospital, Viale Morgagni 85, 50134, Florence, Italy; e-mail:[email protected].

2005 by The Society of Thoracic Surgeonsublished by Elsevier Inc

ats.ctsnetjournDownloaded from

itation. These subjects underwent a Bentall operation.wo patients whose sinuses seemed undilated and mac-

oscopically normal had separate valve graft replacementt first operation and underwent reoperation due toilatation of the native sinuses. Eight patients had partialortic arch replacement (hemiarch), and 1 underwentotal arch replacement. Six-year survival was 0.9 � 0.09;reedom from reoperation at 6 years was 0.77 � 0.13.

Conclusions. Annuloaortic ectasia is a common findingn giant cell arteritis. In patients with Horton disease, theortic root should always be replaced regardless of mac-oscopic findings.

(Ann Thorac Surg 2005;80:101–5)

© 2005 by The Society of Thoracic Surgeonsiant cell arteritis (GCA), also known as temporalarteritis, cranial arteritis, granulomatous arteritis,

nd Horton disease, is a chronic systemic vasculitis ofnknown etiology, affecting medium- and large-sizedrteries [1–3].Typically GCA occurs in patients older than 50 years of

ge, and women seem to be affected twice as much asales [4, 5], although this is still debated [6, 7]. However,

emporal arteritis is the most common primary systemicasculitis in populations with predominantly northernuropean ancestry, with an annual incidence as high as5 to 33 cases per 100,000 persons of middle age or older8–10]. The temporal arteries or other cranial arteries are

ost commonly affected. Nonetheless, the aorta, withny of its primary or secondary branches, may be in-olved. In fact, aortic aneurysm [11], aortic dissection [12,3], and large artery and arm or leg artery stenoses [14,5] have been widely described in GCA. It has beeneported that as many as 15% of patients with temporalrteritis might have angiographic evidence of aortic in-olvement [16], and that patients with GCA are 17.3 timesore likely to develop a thoracic aortic aneurysm com-

ared with the general population [17].We retrospectively analyzed our midterm experienceith aortic root replacement in patients with GCA, tho-

acic aortic aneurysm, and aortic regurgitation.

ccepted for publication Jan 7, 2005.

ddress reprint requests to Dr Gelsomino, Cardiac Surgery Unit, Careggi

atients and Methods

total of 386 cases of ascending aorta and aortic valveeplacement performed for thoracic aortic aneurysm andortic insufficiency between 1998 and 2004 were re-iewed. Among them, 10 cases of histopathologicallyonfirmed GCA were identified. To define clinically man-fested GCA, the American College of RheumatologyACR) criteria were followed [18]. Furthermore, becausef the close relationship between temporal arteritis andolymyalgia rheumatica, all patients were considered for

his association. The current diagnostic criteria for poly-yalgia rheumatica empirically formulated by Chuang

nd coworkers [19] and and Healey [20] were employed.econdary (occult) manifestations were defined follow-

ng published criteria [21].Preoperative patient characteristics are shown in

able 1. Three patients (30%) reflected ACR criteria forhe diagnosis of GCA. Specifically, all these subjectsere older than 50 years of age and had new onsets ofeadaches; 2 had abnormal temporal artery biopsiesnd 1 showed an erythrocyte sedimentation ratereater than 50 mm/h. Eighty percent of patientsresented at observation with cardiovascular symp-

oms including chest pain, dyspnea, and tachycardia.wo (20%) had signs of congestive heart failure. Sec-ndary manifestations occurred in 3 patients as neu-ologic symptoms (transient ischemic attack), Raynaudhenomenon, and fever of unknown origin. Jaw clau-ication, girdle pain, polymyalgia rheumatica, andisual symptoms were uncommon in our cohort. Two

ubjects had preoperative diagnoses of GCA; they had0003-4975/05/$30.00doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.01.063

by on June 6, 2013 als.org

aweetestfstis

ir

oi

rfFa

hfmb

rDlaCes

R

Ti

T

V

AAFHDADTCANLG

a

ahebiCstae(atdetoane(h

N

T

V

LAAADDAS

CADC

MM

102 GELSOMINO ET AL Ann Thorac SurgGIANT CELL ARTERITIS 2005;80:101–5

CA

RD

IOV

AS

CU

LA

R

bnormal biopsies of the temporal artery and under-ent preoperative corticosteroid therapy. In the oth-

rs, the diagnoses were made after routine histologicxamination of aortic wall specimens. All tissue ob-ained at surgery was processed by hematoxylin andosin staining. Specimens of the aortic wall showedigns of chronic inflammation with typical inflamma-ory infiltrate of mononuclear cells with giant cellormation within the media of the arterial wall. Theinuses of Valsalva showed slight signs of inflamma-ion in all patients; however, the inflammatory cellularnfiltrate did not show giant cells. The aortic cusps

able 1. Preoperative Patient Characteristics (n � 10)

ariable

ge, mean � SD (years) 74.5 � 4.6ge, range (years) 65–81emale, n (%) 9 (90)ypertension, n (%) 7 (70)iabetes, n (%) 1 (10)ngina 2 (20)yspnea 7 (70)achycardia 1 (10)ongestive heart failure, n (%) 2 (20)ortic regurgitation ���/����, n (%) 2 (20)/8 (80)YHA class (mean � SD) 3.1 � 0.2eft ventricular ejection fraction, (mean � SD) 47 � 6iant cell arteritis related signs andsymptoms n (%)Preoperative diagnosis 2 (20)�3 ACR criteriaa 3 (30)Jaw claudication 1 (10)Polymyalgia rheumaticab 2 (20)Loss of vision 1 (20)Secondary manifestationsc 3 (30)Girdle pain �1 month 1 (10)Corticosteroid therapy 2 (20)

American College of Rheumatology criteria for diagnosis of giant cellrteritis [18]: patient age 50 years or older, new onset of localizedeadache, temporal artery tenderness or decreased temporal artery pulse,rythrocyte sedimentation rate � 50 mm/hour, abnormal temporal arteryiopsy. b The diagnosis of polymyalgia rheumatica was made follow-

ng the current diagnostic criteria for PRM empirically formulated byhuang and coworkers [19] (age of 50 years or older; bilateral aching and

tiffness for 1 month or more involving two of the following areas: neck ororso, shoulders or proximal regions of the arms, and hips or proximalspects of the thighs; erythrocyte sedimentation rate � 40 mm/hour;xclusion of all other diagnoses except giant cell arteritis) and Healey [20]pain persisting for at least 1 month and involving two of the followingreas: neck, shoulders and pelvic girdle; morning stiffness lasting morehan 1 hour; rapid response to prednisone (�20 mg/day); absence of otherisease capable of causing the musculoskeletal symptoms; age � 50 years;rythrocyte sedimentation rate � 40 mm/hour). c Secondary manifes-ations (excluding thoracic aortic aneurysm) include fever of unknownrigin, respiratory symptoms, otologic manifestations, glossitis, largertery disease (aortic dissection, limb claudication, Raynaud phenome-on), neurologic manifestations (transient ischemic attack/stroke, periph-ral neuropathy, dementia), myocardial infarction, tumorlike lesionsbreast/ovarian/uterine mass), syndrome of inappropriate antidiureticormone secretion, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia.

YHA � New York Heart Association.

howed dystrophic changes with mononuclear cellular

ats.ctsnetjournDownloaded from

nfiltrate but without granulomatouslike inflammatoryeaction and multinucleated giant cells.

Laboratory tests, which were reconsidered after histol-gy analysis, demonstrated an increase in inflammatory

ndices in only 2 patients.All subjects underwent preoperative computed tomog-

aphy scan and angiography, the latter showing unaf-ected coronary arteries in the entire study population.inally, echocardiography was performed preoperativelynd before hospital discharge.All surviving patients were routinely followed up and

ad a computed tomography scan at 6 months and 1 yearrom surgery. All information was obtained by review of

edical records, written or telephone communication, oroth, and outpatient appointments.All data were analyzed with the SPSS for Windows,

elease 8.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois) statistical package.eath and event-free survival estimates were calcu-

ated by the product-limit method of Kaplan and Meiernd reported with 95% confidence limit; the Mantel-ox (log-rank) test was used to test survival differ-nces. A p value less than 0.05 was consideredignificant.

esults

able 2 shows the operative data. Indications for surgeryncluded cardiac symptoms (dyspnea on exertion, an-

able 2. Operative Data (n � 10)

ariable

ocation of aneurysm, n (%)scending aorta 1 (10)scending aorta-arch 8 (80)scending aorta-arch–descending aorta 2 (20)iameter of ascending aorta (mm, mean � SD) 52 � 6.3iameter of Valsalva sinuses (mm, mean � SD) 40 � 3.4nnular diameter (mm) 26.8 � 1.8urgical procedure, n (%)Bentall procedure 8 (80)Separate valve and graft replacement 2 (20)Arch replacementNo 1 (10)Hemi-arch 8 (80)Total arch replacement 1 (10)

ardiopulmonary bypass time (min) 166.9 � 26.1ortic cross-clamp time (min) 136.6 � 22.5eep hypothermic circulatory arrest, n (%) 1 (10)erebral perfusion, n (%)None 1 (10)Retrograde cerebral perfusion 1 (10)Antegrade cerebral perfusion 8 (80)ean graft diameter (mm) 28.2 � 2.5ean prosthesis diameterMechanical 25.6 � 1.8

Biological 24 � 1.4by on June 6, 2013 als.org

gpgtcidfaptunucEvpatu

ap

s(sdF(tAtuidpmAflrsagt

C

GumbhTvsc(wpftctHaascteptlcbwdaa

Fwd

FttBy

103Ann Thorac Surg GELSOMINO ET AL2005;80:101–5 GIANT CELL ARTERITIS

CA

RD

IOV

AS

CU

LA

R

ina) in 2 patients (20%) and congestive heart failure in 2atients (20%); in the rest of the cases, the indication wasiven on the basis of aneurysm size. At surgical inspec-ion, either the ascending aorta and the aortic arch wereommonly affected. In only 1 patient was there no diseasenvolvement. In 1 patient, the aneurysm extended to theescending aorta. Eight patients (80%) showed typical

eatures of annuloaortic ectasia, leading to significantortic regurgitation. These subjects underwent a Bentallrocedure. In all patients, the St. Jude valve graft pros-

hesis (St Jude Medical, Minneapolis, Minnesota) wassed. In 2 patients, the sinuses seemed macroscopicallyormal, and the annulus was undilated. These patientsnderwent separate graft valve replacement and re-eived, respectively, a 23-mm and 25-mm Carpentier-dwards biological prosthesis (Edwards Lifescience, Ir-ine, California) because of their advanced age. Eightatients had partial aortic arch replacement (hemiarch),nd 1 underwent total arch replacement. For these pa-ients, deep hypothermic (22°C) circulatory arrest wassed in 1, retrograde cerebral perfusion was used in 1,

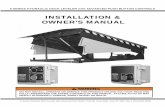

ig 1. Six-year survival after aortic root replacement in patientsith giant cell arteritis. (H � hazard; S � survival; SE(H) � stan-ard error hazard; SE(S) � standard error survival.)

ig 2. Freedom from reoperation after aortic root replacement in pa-ients with giant cell arteritis. Freedom from reoperation was foundo be significantly higher in Bentall. Diamonds � all; squares �entall; triangles � separate valve graft replacement. (Yrs. �

tears.)

ats.ctsnetjournDownloaded from

nd selective antegrade cerebral perfusion was used in 8atients. No other cardiac procedure was performed.There was an in-hospital death occurring 10 days after

urgery caused by multiorgan failure. Six-year survivalFig 1) was 0.9 � 0.09 (SE [hazard � 0.10 � 0.1]). Meanurvival time was 64.8 months. Two patients (20%) un-erwent reoperation for dilatation of the native sinuses.reedom from reoperation at 6 years was 0.77 � 0.13hazard � 0.25 � 0.1). Freedom from reoperation resultedo be significantly higher in the Bentall procedure (Fig 2).ctuarial freedom from thromboembolic events and an-

icoagulant-related hemorrhage was 100%. Two patientsnderwent 1-year postoperative steroid therapy. The

nitial dose was 40 mg of prednisone followed by a dailyose of 10 mg for 6 months and 5 mg within 1 year. Theseatients remained asymptomatic with erythrocyte sedi-entation rate and C-reactive protein levels normal.mong nontreated patients, 2 had fever with high in-ammation indices at 34 and 56 months postoperatively,espectively, and 1 patient exhibited headaches and tran-itory visual loss 16 months after surgery. In 1 patient, anbdominal aortic aneurysm developed and required sur-ery. No patient showed signs of dissection or stenosis ofhe large arteries.

omment

iant cell arteritis is a chronic systemic vasculitis ofnknown etiology with a distinct tropism for large andedium-sized arteries with well developed elastic mem-

ranes [22]. Its incidence rises with increasing age and isigher among whites than blacks, Hispanic, or Asians.he highest incidence rates are described in Scandina-ian countries and North American populations of theame descent [23]. Symptoms include headache, jawlaudication, visual symptoms, fever, and an abnormalpulseless, enlarged) temporal artery [21]. In addition,eak extremity pulses, arm claudication, and Raynaudhenomenon type may occur; these symptoms result

rom the narrowing or occlusion of branches of thehoracic aorta. Polymyalgia rheumatica and GCA arelosely related entities, and approximately 40% of pa-ients with arteritis have polymyalgia rheumatica [24].

owever, the range of presenting features is enormous,nd 40% of patients do not present with the classic signsnd symptoms [25]. Although an elevated erythrocyteedimentation rate is such a common feature that itonstitutes one of the five ACR criteria for the classifica-ion of the disease [18], the prevalence of low or normalrythrocyte sedimentation rate in GCA has been re-orted to vary from 0% to 22.5% [4, 26]. Typical his-

opathologic findings are disruption of the internal elasticamina and an inflammatory cellular infiltrate with giantells [27]. Involvement of medium-size arteries tends toe predominantly focal with some skipped lesions,hereas aortic involvement tends to be continuous andiffuse [28]. The temporal arteries are most commonlyffected; nonetheless, GCA may lead to weakening of theortic wall and eventual aneurysm formation or dissec-

ion [17]. Although this association is not new and aorticby on June 6, 2013 als.org

irrtdwtasnqacai

rocoasacaa(po

psiTtrar

racvltchitmemrp

rcr

s

pfpatipa

dnsmrchs

ni[arcocnnd

CPbllos3aGsasav

tma

Wr

R

104 GELSOMINO ET AL Ann Thorac SurgGIANT CELL ARTERITIS 2005;80:101–5

CA

RD

IOV

AS

CU

LA

R

nvolvement in GCA was first reported in 1937 [29], it hasecently gained renewed attention. Thoracic aortic aneu-ysms are usually a late complication of GCA; however,hey can occur at any time during the course of theisease, and rupture or dissection of the aortic wall asell as aortic regurgitation might be an initial manifes-

ation of temporal arteritis [30]. Patients presenting withcute aortic pathology as the first clinical manifestationhowed a mortality rate as high as 80% after 2 weeks [30];onetheless, these catastrophic complications are infre-uent in GCA-diagnosed patients [31] whereas activeortitis caused by occult GCA seems to occur moreommonly than previously appreciated and to representn important clinical variant of the disease, often requir-ng a prompt diagnosis and early referral to surgery [32].

In the present study, we reviewed patients with tho-acic aortic aneurysm and aortic regurgitation operatedn between 1998 and 2004. Ten cases of histopathologi-ally confirmed GAA were identified, and the incidencef GCA was 2.6% among patients with thoracic aorticneurysm/aortic regurgitation. Older women weretrongly prevalent, and the ascending aorta and aorticrch were mainly affected. In the same period, we en-ountered 2 patients with GCA with a thoracic aorticneurysm without aortic regurgitation; the incidence ofortic regurgitation in our GCA patients was very high83.3%), and annuloaortic ectasia was the most commonathologic finding in GCA as first reported in our previ-us study [32].Eighty percent of our cohort underwent a Bentall

rocedure; contrastingly, 2 patients with sinuses macro-copically normal and annulus undilated at surgicalnspection, received a separate valve graft replacement.hese patients underwent reoperation because of redila-

ation (true aneurysm) of native sinuses. Thus, our expe-ience suggests that in patients with Horton disease, theortic root should always be replaced regardless of mac-oscopic findings.

Another point of interest is the mechanism of aorticegurgitation, which is reported to vary from 9.8% to 33%mong patients with GCA [17, 32]. In all patients in ourohort, valve cusps were macroscopically normal, andalve incompetence was presumably caused by lack ofeaflets coaptation secondary to aneurismal dilatation ofhe aortic root [17]. Thus a “valve-sparing” operationould be indicated in these patients. Nonetheless, atistologic examination, aortic leaflets showed signs of

nflammation with mononuclear cellular infiltrate, evenhough we failed to find a true granulomatouslike inflam-

atory reaction with multinucleated giant cells. How-ver, owing to the advanced age of the patients and theild dystrophic changes of the cusps, a Bentall operation

emains, in our opinion, the treatment of choice for theseatients.Six-year survival was 0.9 � 0.09 and freedom from

eoperation at 6 years was 0.77 � 0.13, with resultsomparable with, in our experience, those of aortic rooteplacement performed in non-GCA patients.

Only 2 patients in the present series received cortico-

teroids preoperatively. That is mainly because for mostats.ctsnetjournDownloaded from

atients the diagnosis is not made until the operation; inact, only a small number of subjects had been diagnosedreoperatively and received preoperative steroid ther-py. The overlap of atherosclerosis with GCA may renderhe evaluation of both angiographic and pathologic find-ngs more difficult. Thus, active aortitis caused by GCArobably occurs more commonly than previouslyppreciated.In our experience, however, we failed to detect any

ifference between these patients and subjects who didot receive corticosteroids. Contrastingly, we found thatubjects receiving postoperative steroid therapy re-ained asymptomatic, with erythrocyte sedimentation

ate and C-reactive protein levels that were normal. Inontrast, among nontreated patients, 2 had fever withigh inflammation indices, and 1 patient wasymptomatic.

The major shortcoming of our study is the smallumber of patients. Nonetheless, considering that the

ncidence of diagnosed GCA in our country is 6.9/100,0004], that approximately 15% of them [16] have thoracicortic aneurysm, and that only a small percentage will beeferred to surgery [33], our small cohort may be suffi-iently representative of a disease that is infrequent atur latitude. Given that the population in developingountries is increasingly getting older, however, theumber of people at risk can be expected to double in theext 25 years; Therefore, probably we will face thisisease much more in the future.

onclusionsatients with a typical history of Horton disease shoulde closely followed up to ensure the early detection of

arge-vessel pathology, which could be responsible forife-threatening complications such as aortic dissectionr rupture, severe aortic incompetence, and ischemicyndrome of the upper and lower extremities [17, 26,0]. Moreover, when cardiologist are faced with anortic aneurysm in older patients, particularly women,CA should at least be suspected and other elements

ought in the patient’s clinical history in order toscertain the nature of the aortopathy. When a GCA isuspected, an investigation of the superficial temporalrteries by duplex ultrasonography may also be ofalue [34].However, in presence of diagnosed or suspected GCA,

he aortic root should always be replaced regardless ofacroscopic findings. Nonetheless, further larger series

re necessary to confirm our conclusions.

e gratefully acknowledge Dr Judith Wilson for the Englishevision of the manuscript.

eferences

1. Evans JM, Hunder GC. Polymyalgia rheumatica and giantcell arteritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2000;26:493–515.

2. Salvarani C, Cantini F, Boiardi L, et al. Polymyalgia rheu-matica and giant cell arteritis. N Engl J Med 2002;347:261–71.

by on June 6, 2013 als.org

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

3

3

3

3

3

105Ann Thorac Surg GELSOMINO ET AL2005;80:101–5 GIANT CELL ARTERITIS

CA

RD

IOV

AS

CU

LA

R

3. Calvo-Romero JM. Giant cell arteritis. Postgrad Med J 2003;79:511–5.

4. Levine SM, Hellmann DB. Giant cell arteritis. Curr OpinRheumatol 2002;14:3–10.

5. Nordborg E. Epidemiology of biopsy positive giant cellarteritis: an overview. Cli Exp Rheumatol 2000;18(4 Suppl20):S15–7.

6. Nir-Paz R, Gross A, Chajek-Shaul T. Sex differences in giantcell arteritis. J Rheumatol 2002;29:1219–23.

7. Nuenninghoff DM, Hunder GG, Matteson EL. Sex differ-ences in giant cell arteritis. J Rheumatol 2003;30:1119.

8. Baldursson O, Steinsson K, Bjoernsson J, Lie JT. Giant cellarteritis in Iceland: an epidemiologic and histopathologicanalysis. Arthritis Rheum 1994;37:1007–12.

9. Haugeberg G, Paulsen PQ, Bie RB. Temporal arteritis in VestAgder Country in southern Norway. J Rheumatol 2000;27:2624–7.

0. Gonzalez-Gay MA, Garcia-Porrua C, Rivas MJ, Rodriguez-Ledo P, Llorca J. Epidemiology of biopsy proven giant cellarteritis in northwestern Spain: trend over an 18 year period.Ann Rheum Dis 2001;60:367–71.

1. Nuenninghoff DM, Hunder GG, Christianson TJ, McClel-land RL, Matteson EL. Mortality of large-artery complication(aortic aneurysm, aortic dissection, and/or large-artery ste-nosis) in patients with giant cell arteritis: a population-basedstudy over 50 years. Arthritis Rheum 2003;48:3532–7.

2. Nuenninghoff DM, Hunder GG, Christianson TJ, McClel-land RL, Matteson EL. Incidence and predictors of large-artery complication (aortic aneurysm, aortic dissection,and/or large-artery stenosis) in patients with giant cellarteritis: a population-based study over 50 years. ArthritisRheum 2003;48:3522–31.

3. Berry MF, Woo YJ. Repair of acute type A aortic dissectionassociated with temporal arteritis. Ann Thorac Surg 2003;76:1717–8.

4. Nuenninghoff DM, Warrington KJ, Matteson EL. Concomi-tant giant cell aortitis, thoracic aortic aneurysm, and aorticarch syndrome: occurrence in a patient and significance.Arthritis Rheum 2003;49:858–61.

5. Brack A, Martinez-Taboada V, Stanson A, Goronzy JJ,Weyand CM. Disease pattern in cranial and large-vesselgiant cell arteritis. Arthritis Rheum 1999;42:311–7.

6. Lie JT. Aortic and extracranial large vessel giant cell arteritis:a review of 72 cases with histopathologic documentation.Semin Arthritis Rheum 1995;24:422–31.

7. Evans JM, O’Fallon WM, Hunder GG. Increased incidence ofaortic aneurysm and dissection in giant cell (temporal)arteritis. A population-based study. Ann Intern Med 1995;

122:502–7.ats.ctsnetjournDownloaded from

8. Hunder GG, Bloch DA, Michel BA, et al. The AmericanCollege of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classificationof giant cell arteritis. Arthritis Rheum 1990;33:1122–8.

9. Chuang TY, Hunder GG, Ilstrup DM, Kurland LT. Polymy-algia rheumatica: a 10-year epidemiologic and clinical study.Ann Intern Med 1982;1997:672-80.

0. Healey LA. Long-term follow-up of polymyalgia rheumatica:evidence for synovitis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1984;13:322–8.

1. Hellmann DB. Giant cell arteritis. In: Kaplan P, ed. Neuro-logic disease in women. New York: Demos Medical, 1998:243–50.

2. Lie JT. Systemic, pulmonary and cerebral vasculitis. In:Stehbens WE, Lie JT, eds. Vascular pathology. London:Chapman and Hall, 1995;623–56.

3. Goodwin JS. Progress in gerontology: polymyalgia rheu-matica and temporal arteritis. J Am Geriatr Soc 1992;40:515–25.

4. Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ. Giant cell arteritis and polymyal-gia rheumatica. Ann Intern Med 2003;139:505–15.

5. Gonzalez-Gay MA, Garcia-Porrua C, Salvarani C, et al. Thespectrum of conditions mimicking polymyalgia rheumaticain northwestern Spain. J Rheumatol 2000;27:2179–84.

6. Salvarani C, Hunder GC. Giant cell arteritis with low eryth-rocyte sedimentation rate. Frequency of occurrence in apopulation-based study. Arthritis Care Res 2001;45:140–5.

7. Richardson MP, Lever AM, Fink AM, Dixon AK, HazlemanBL. Survival after aortic dissection in giant cell arteritis. AnnRheum Dis 1996;55:332-3.

8. Liu G, Shupak R, Chiu BKY. Aortic dissection in giant cellarteritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1995;25:160–71.

9. Sproul EE, Hawthorne JJ. Chronic diffuse mesoarteritis. Am JPathol 1937;13:311.

0. Evans J, Hunder GG. The implications of recognizing large-vessel involvement in elderly patients with giant cell arteri-tis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 1997;9:37–40.

1. Evans JM, Bowles CA, Bjornsson J, Mullany CJ, Hunder GG.Thoracic aortic aneurysm and rupture in giant cell arteritis.A descriptive study of 41 cases. Arthritis Rheum 1994;37:1539–47.

2. Nesi G, Anichini C, Pedemonte E, et al. Giant cell arteritispresenting with annuloaortic ectasia. Chest 2002:121:1365–7.

3. Kerr LD, Chang YJ, Spiera H, Fallon JT. Occult active giantcell aortitis necessitating surgical repair. J Thorac CardiovascSurg 2000;120:813–5.

4. Schmidt WA, Kraft HE, Vorpahl K, et al. Color duplexultrasonography in the diagnosis of temporal arteritis.

N Engl J Med 1997;337:1336–42.by on June 6, 2013 als.org

2005;80:101-105 Ann Thorac SurgCarlo Sorbara, Pierluigi Stefàno and Gian Franco Gensini

Sandro Gelsomino, Stefano Romagnoli, Franca Gori, Gabriella Nesi, Chiara Anichini, Annuloaortic Ectasia and Giant Cell Arteritis

& ServicesUpdated Information

http://ats.ctsnetjournals.org/cgi/content/full/80/1/101including high-resolution figures, can be found at:

References http://ats.ctsnetjournals.org/cgi/content/full/80/1/101#BIBL

This article cites 32 articles, 7 of which you can access for free at:

Citations http://ats.ctsnetjournals.org/cgi/content/full/80/1/101#otherarticles

This article has been cited by 4 HighWire-hosted articles:

Subspecialty Collections

http://ats.ctsnetjournals.org/cgi/collection/great_vessels Great vessels

following collection(s): This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

[email protected]: orhttp://www.us.elsevierhealth.com/Licensing/permissions.jsp

in its entirety should be submitted to: Requests about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

Reprints [email protected]

For information about ordering reprints, please email:

by on June 6, 2013 ats.ctsnetjournals.orgDownloaded from