An Initial Investigation of the Branded Petrol Market - CiteSeerX

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

2 -

download

0

Transcript of An Initial Investigation of the Branded Petrol Market - CiteSeerX

Military-Madrasa-Mullah Complex 137

India Quarterly, 66, 2 (2010): 133–149

A Global Threat 137Article

Measuring Consumers’ Preferences and Attitudes Towards Branded Petrol: An Initial Investigation of the Branded Petrol Market

Anurag Dugar

AbstractPetrol was sold as a ‘commodity’ through ‘mass marketing’ in India for over four decades andgenerationsof Indian consumers got soused to this thatwhen ‘segmentedmarketing’ arrived andbrandswerelaunchedin2002,aparadigmshiftwasexpectedinmarketingpracticesandalsoincon-sumerbehaviour.Thechangesoccurred,asexpected. Before2002,Indianconsumerspurchasedpetrolwhichcameinonlyonevariant,fromgovernmentregulatedcompanieswithsimilarsoundingnamesandlogos,atonepricefromonetypeofoutlet.Eventhepromotioncampaignsreachedconsumersthroughidenticalmedia(hoardings)andconveyedidenti-calmessages(‘savepetrol’).Thiswastheresultoftightregulationsposedbythegovernmentonthemarketingofpetrol.Also,offeringsubsidiestopetroleummarketingcompaniesandsettingdifferentpricesofpetrolanddieselwerealsoapartofgovernment’soverallstrategy. Overaperiodof time, the sharp rise indemandmade thegovernment realize that it couldnotmanage theexploration, refiningandmarketingofpetrolon itsown.Aftera lotofdeliberation, in2002,governmentallowedprivatesectorplayerstomarketpetrol,withapromiseofprovidingalevelplayingfieldtothem.Asaresult,theIndianmarketsawtheentryofmultinational(RoyalDutchShellPlc.)andprivateIndianplayers(RelianceIndustries,EssarOilLimited,etc.)settingupshoptomarketpetrol.Brandswerelaunched,celebritieswerehiredtopromotethebrands,outletswererefurbishedandpricingwasrevisitedanddifferentvariantsofpetrolwereofferedatdifferentprices.Thewholescenariochangedveryquicklyandcompanieswentoutallgunsblazingandalltheplayerslaunchedamarketingblitzkrieg. Objective of the study:Now, after a decade of high-decibelmarketing action and aftermillionshavingbeenspentinbrandbuildingandeducatingconsumersaboutthenewavatarsofpetrolandwaysofpetroleummarketing,itwasfeltthatitwouldbeinterestingandusefultotakestockoftheoutcomeofthesemarketingactivities.Tobeprecise,thisresearchisaimedatmeasuringthechanges,ifany,inconsumers’preferencesandattitudestowardsbrandedpetrol.

Methodology:Toachievetheabove,anempiricalstudywasundertakenanddatawascollectedfrom900MBAstudentswhodrivetheirownvehiclesandhenceareconsumersofpetrol.Hence,itwasafairlylargehomogenoussetofrespondentstowhomthequestionnairewasadministered.

Anurag DugarisAssociateProfessor–MarketingArea,SymbiosisInstituteofBusinessManagement(SIBM),Pune,Maharashtra,India.E-mail:[email protected]

GlobalBusinessReview14(1)137–154

©2013IMISAGEPublications

LosAngeles,London,NewDelhi,Singapore,

WashingtonDCDOI:10.1177/0972150912466466

http://gbr.sagepub.com

at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 8, 2016gbr.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Global Business Review, 14, 1 (2013): 137–154

138 Anurag Dugar

Findings:Theresultsofthestudypresentinterestingfindingsforacademiciansaswellasmarketers.Itwasfoundthatalthoughconsumersseevalueinbrandedpetroltheyconsiderdifferentbrandsofpet-rolas‘verysimilar’.Itmaybeconcludedthatthemarketingstrategieshavemadetheconsumerssitupandtakenoticeofpetrolbrandsandalsothestrategieshavebeensuccessfulinthesensethatconsum-ersseevalueinbrandedpetrol.Anotherinterestinginsightasaresultofanalysiswasthatconsumersperceivethattheyarepricesensitiveasfaraspetrolisconcerned,butactuallytheyarenot.

Implications:Theabovesuggeststhatcompanieswouldhavetothinkofcreativewaystopositiontheirbrandsas‘different’becauseuntilthatisachieved,thecompanieswillnotbeabletoreaptherealbenefitsofmarketingandmarketersofpetrolneednotlosetheirsleeponthepricesensitivityoftheconsumers(atleastuptoanextent);rather,theyshouldfocusonaddingvalueandcreatingmeaningfuldifferentiation.

Keywords

Branding,marketingmix,petrol,gasoline,commodity

To appreciate, analyze and evaluate the marketing function in the business of petrol, one needs to know the basics of this particular industry because in spite of being something that touches the lives of millions on a daily basis, few understand petrol as a product and even fewer understand where it originates. This is important because these factors dictate the way in which the business of petroleum marketing is con-ducted. This article begins with a brief insight into the evolution and present status of the business of petrol, with special reference to the Indian market.

With extensive media coverage on the stories related to oil in general and petrol in particular, terms like fossil fuels, hydrocarbon, oil and petrol have emerged as popular buzz words. Mistakenly, these terms are used synonymously in common parlance. To remove that misconception, a brief overview of what these terms mean and where these products come from is given below with special emphasis on petrol.

Fossil fuels are sources of energy formed because of the reaction that takes place between the remains of once-living organisms (buried under various layers of earth) with the material under which they get buried (Bartsch and Miller, 2000). This reaction is very slow and might take centuries. Oil, coal and natu-ral gas are some of these fossil fuels. Fossil fuels take such different forms because of the ‘differences in materials’ between which the reactions take place (remains of different living organisms stay buried for different time periods, under different materials found in layers of earth at different places) (Oil.. Black Gold.. What’s all the fuss about?, 2004).

After the reaction takes place, various compounds, made up of different proportions of hydrogen and carbon are formed. These compounds are called hydrocarbons. Oil is composed of liquid hydrocarbon compounds and hence it is a kind of liquid hydrocarbon mostly found inside the small pores of the sedi-mentary rocks. The word ‘petrol’ has been derived from a Latin word ‘petra’, which means rock or stone, and ‘oleum’, which means oil. From this derivation petrol can be defined as ‘rock oil’. In fact, petrol is derived from crude oil, which happens to be ‘rock oil’ in the true sense of the word (How was oil formed?, n.d.). In refineries, petroleum is extracted from crude oil drilled from the earth.

Petrol is known by different names in different parts of the globe, like benzine, gasoline, petroleum, petroleum spirit and petrogasoline. In the commonwealth countries it is popular by the name of ‘petrol’,

at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 8, 2016gbr.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Global Business Review, 14, 1 (2013): 137–154

Measuring Consumers’ Preferences and Attitudes Towards Branded Petrol 139

which has been derived from ‘petroleum spirit’. Petrol is also given different names on the basis of its usage (Evans, 2011); for example in India, the fuel used in automobiles is called petrol while the fuel used in airplanes is called ATF or aviation turbine fuel. In some countries the term ‘mogas’ (for motor gas) and ‘avgas’ (for aviation gas) are used to distinguish between the two. However, this is certainly not to say that petrol is the same as ATF; there is a difference in the production process, components and purity.

Business of Petrol

Universally, the business of petrol can be classified into two broad categories—‘upstream’ and ‘down-stream’. This classification is done on basis of the functions that petroleum companies perform. As the names might suggest, ‘upstream’ involves the extraction of oil from underground or underwater deposits and ‘downstream’ involves converting oil into petrol (and other things) and taking the final product to the end consumer. These functions are so specialized in nature that most companies operating in this business either work in the downstream sector or the upstream sector. However, there are few ‘integrated organizations’, which perform both functions. For the purpose of this article, a further classification of the downstream companies has been made into two categories—‘refining’ and ‘marketing’.

The ‘petroleum marketing industry’ includes all companies engaged in the marketing and transporta-tion of petrol. These companies take or buy petrol from the refineries and manage the transportation to their petrol pumps where it is sold to end consumers. It can be concluded that while refining is concerned with the physical production of oil, marketing focuses on the selling process to consumers.

The aforementioned definition of the petroleum marketing industry represents the industry as if it is structured in an identical fashion across the globe. Nothing can be further from the truth. Different economies have given different shapes to this industry, based on their orientation towards it. On one extreme are the developed countries like the United States and the United Kingdom, where this industry has been open and competitive since its inception (Chan et al., 2007; Chandra and Tappata, 2011; Ingene and Brown, 1987) and on the other are markets like India, where till date, the government plays a critical role in the operations of this industry. To be specific, the petroleum marketing industry in India has seen both regulated and deregulated eras. To be precise, until the late 1970s, the Indian petroleum marketing industry was dominated by private players, nationalization occurred thereafter and continued until 2002, after which this industry was again opened for private players. Somewhere in between these two extremes are countries like Pakistan, where state-run companies operate along with private players (Higgins, 1998).

Indian Petroleum Marketing Industry: Evolution in a Nutshell

The Indian petrol retailing industry is very old. It virtually started with the entry of automobiles in India. This section describes briefly its evolution after Independence. Since 1947, foreign petroleum companies have dominated the Indian petroleum industry (both upstream and downstream) and obviously so. India did not have the technology and expertise to explore, drill and refine oil. Companies such as ESSO, Caltex, Burmah Shell, etc., were present for this task and were running their businesses without interference from the government.

at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 8, 2016gbr.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Global Business Review, 14, 1 (2013): 137–154

140 Anurag Dugar

In the early 1970s, after facing the first oil shock, the Indian government realized that having a grip over the supply and prices of petroleum products is critical because they affect the life of everyone in one way or the other. So the government started the nationalizing these foreign companies and also started opening its own enterprises in this sector. In this process, Burmah Shell was transformed into Bharat Refineries and later to Bharat Petroleum Corporation Limited (BPCL) and ESSO became Hindustan Petroleum Corporation Limited (HPCL).

Since then, the government has regulated this industry according to its socialistic objectives and con-trolled prices, distribution and imports through various mechanisms devised from time to time, like oil pool, subsidies, administered price mechanism (APM), etc. After meeting the immediate requirements of controlling the prices and ensuring supplies through the process of nationalization, in the late 1980s, because of growing demand of petroleum products due to industrialization and transportation activities, the government began focusing on exploration and production activities.

However, soon, in the early 1990s, the government realized two things—one was that mounting losses to the oil marketing companies was increasing the burden of subsidies to an intolerable level. Adding to that was international pressure to remove subsidies. The second realization was that the govern ment-controlled system could not grow fast enough to meet the country’s rapidly growing demand of petroleum products.

As a result, the obvious thought was to have private players onboard to obtain the necessary invest-ment as well as speed in improving the whole set-up from exploration to marketing of petroleum prod-ucts. Life came full circle for this industry when recently, the government allowed 100 per cent foreign investment in the oil and petroleum sector (Kaur, 2004). This move has encouraged private players from India and abroad to open shop in this industry.

Indian Petroleum Industry: Demand, Supply and the Gap In Between

One important reason behind the initial restriction on aggressive marketing of petrol in India was that the government thought of petrol as a ‘strategic commodity’. This realization came after the first oil shock. Also, for most of the post-Independence period, India felt the pressure of ever-increasing demand and ever-reducing domestic supplies, which translated into high pressure on foreign exchange reserves. In such a scenario, it seems obvious for the government to think of not pushing the product to the market.

Even today, India is amongst the top 10 and one of the fastest growing energy consumers in the world (India’s energy trilemma, 2012). The rapidly growing economy, rising population and an expanding number of middle-class consumers (Ablett et al., 2007) are fuelling the demand for petrol in India. However, due to limited domestic crude oil reserves, more than 70 per cent of India’s oil and petroleum product (diesel, aviation fuel, etc.) requirements are met through imports. Import of these products is all set to increase further in near future. Value-wise also, India’s oil import bill has been growing at a faster rate than the demand on account of escalation in global oil prices. Earlier the government used to subsi-dize the price hikes and consumers never felt the significant shocks but now that the government of India has decided to provide autonomy to petrol marketing companies as far as pricing is concerned, the price of petrol has been increasing drastically. In the last one year, the price of petrol has been increased nine times. This is something that the Indian petrol consumer is not very used to seeing.

at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 8, 2016gbr.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Global Business Review, 14, 1 (2013): 137–154

Measuring Consumers’ Preferences and Attitudes Towards Branded Petrol 141

Increasing Consumption

As mentioned earlier, increasing income and expanding cities are fuelling the demand for automobiles and thereby the consumption of petrol is also increasing. Figure 1 shows the consumption pattern of petrol in India since the 1970s. It is visible that until the 1980s the consumption was more or less stag-nant, but after that it started rising. After liberalization, i.e., after 1991, the consumption of petrol increased rapidly, while as shown in Figures 1a and 1b, the domestic production reached the peak in the early 2000s and has remained more or less stagnant or rather reducing.

petrol consumption

9286

14192

10332 1125812818

2006−07 2010−11*2009−102008−092007−08

18000

12000

6000

0

petrol consumption

Figure 1a ConsumptionPatternofPetrolinIndia(inthousandtonnes)

Note: 2010-11*-ProvisionalData

2006−07

120.75

2009−102008−092007−08 2010−11*

133.6138.2

128.95

141.79

206.15192.77160.77156.1

146.55

347.94330.97

294.37285.05267.3

consumption of crude and other petro products400

0

100

200

300

oil petro products total consumption

Figure 1b ConsumptionofCrudeOilandPetroleumproducts(inmilliontonnes)Source: IndianPetroleum&NaturalGasStatistics2010–11,ReportofGovernmentofIndia,MinistryofPetroleumandNatural

Gas,EconomicDivision,NewDelhi,p.5.Retrievedfromhttp://petroleum.nic.in/pngstat.pdfNote: 2010-11*-ProvisionalData

at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 8, 2016gbr.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Global Business Review, 14, 1 (2013): 137–154

142 Anurag Dugar

4000

5001000150020002500

30003500

0

2002

−03

2007

−08

2006

−07

2005

−06

2004

−05

2003

−04

2009

−10

2008

−09

Figure 2a ValueofImportedCrudeOil(in`Billion)

2002−03 2007−082006−072005−062004−052003−04 2009−102008−09

160

80

100

120

140

40

60

20

0

Figure 2b ValueofImportedCrudeOil(inmilliontonnes)

Source: IndianPetroleum&NaturalGasStatistics2010–11,ReportofGovernmentofIndia,MinistryofPetroleumandNaturalGas,EconomicDivision,NewDelhi,p.5.Retrievedfromhttp://petroleum.nic.in/pngstat.pdf

Liberalization and Its Impact on Imports and Exports

The impact of liberalization began after 1993–1994, which is reflected through the increasing consump-tion of petroleum products. Increasing consumption obviously pulled up the demand also. The fact that India’s domestic production of oil has been stagnant (rather, gradually reducing), this (increasing con-sumption and demand) increased the gap between production and consumption (as presented in Figure 1). This widening gap is filled through increasing the imports and reflects the reducing self- sufficiency of India in terms of crude oil, which is the raw material for other petroleum products. India’s self-reliance on crude oil, which was 63 per cent in 1989–1990 reduced to less than 30 per cent in the early 2000s and is continuously falling further (Kaul, n.d.). Similarly, the value and volume of crude imports have increased significantly, along with the ratio of ‘oil and petroleum products’ in India’s ‘total imports’. The volume and value of oil and petroleum products is presented in Figures 2a and 2b.

at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 8, 2016gbr.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Global Business Review, 14, 1 (2013): 137–154

Measuring Consumers’ Preferences and Attitudes Towards Branded Petrol 143

Here, it is worth mentioning that as the international prices of crude increase, the amount of money that goes out of India increases far more rapidly in comparison to the increasing quantity of oil and petro-leum products that India imports.

Paradigm Shift in Petrol Marketing in India

One might ask what made the government change its mind about marketing of petrol. If in the 1970s it restricted private players and opted for nationalization of the companies operating in this arena, then why did it allow them again in 2002? There could be multiple answers. One of the most important ones is the change that came with liberalization. Growing incomes, increasing availability and options to suit every pocket, coupled with improving credit facilities and infrastructure pushed the demand for petrol and the government realized that it could not take petrol everywhere on its own, so it allowed private players to share the burden by offering them this lucrative market as an opportunity. This resulted in a complete transformation of the marketing mix and was not less than a shock to the consumer.

Indian petrol consumers saw petrol as a ‘commodity’ for approximately four decades (a period start-ing from the mid-1970s and until 2002). Generations grew up with petrol being sold as only ‘petrol’, that is, no variants at all, at the same prices (at least within the state they lived in), at similar-looking petrol pumps of companies bearing similar sounding names and logos and which belonged to the same parent, that is the Government of India. In other words, all the elements of marketing mix offered by the sellers were extremely similar to each other and hence the notion of ‘commodity’.

Come 2002, everything in this arena changed. From marketing mix to players, from prices to services, there was a disruption in the ‘business-as-usual’ situation. The Government of India opened up this industry to private players both from India and abroad. This move brought in new players (Reliance Industries Limited and Essar Oil Limited from India and Royal Dutch Shell Plc. entered the market) and led to the birth of petrol brands.

For consumers it was a paradigm shift; something that was a ‘commodity’ with very high degree of ‘sameness’ was suddenly presented to them as ‘brands’, indicating ‘differentiation’. Not only that, consum-ers saw a sea change in the attitude of petrol-selling companies towards them. Petrol pumps started pam-pering consumers by providing them with a host of services, celebrities started endorsing petrol, and so on.

Not only for the consumers, but also for the industry it was a major transformation. A very interesting equation emerged. There were public sector companies (IOCL, BPCL and HPCL) who knew the market like the backs of their hands but these companies were not used to marketing petrol. Then there were companies (Reliance Petrochemicals and Essar Oil) who were new to this business but knew the market and were known as aggressive marketers and finally, there was a company (Shell), a global giant in the petrol business, but new to Indian market. So, in this new equation, the public sector was competing against private sector and Indian firms stood against the global petroleum giant.

Changing Dynamics of Indian Petrol Marketing Industry: New Players

In India, the petroleum industry embraced the marketing concept in its complete sense only recently. The government allowed private players and also gave some freedom to petrol marketing companies

at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 8, 2016gbr.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Global Business Review, 14, 1 (2013): 137–154

144 Anurag Dugar

to launch brands and set prices (although within a pre-specified range). The idea behind this step was that allowing private players would not only bring in money, but also speed up the process of finding new oil reserves. The step was welcomed by private players from India, as well those as from abroad.

Until the recent past, the Indian petroleum marketing industry had been a reserved place for public sector undertakings (PSUs). Not anymore. Today, this industry is witnessing and welcoming the private players across every segment—be it exploration and production (as mentioned earlier), transportation, refining, or retailing of products. Private players, including multinational players, are increasing their footprint in this industry.

In exploration and production, companies like Reliance Petroleum Limited and Cairn Energy (India) Limited, British Gas, etc., are present. In refining, there are Reliance Petroleum Limited (RPL) and Essar Oil Limited (EOL), and in retailing, RIL, EOL and Shell India Markets Private Limited (SIMPL) are increasing their stronghold. So private players have entered virtually all the components of the value chain of this industry.

However, in India, PSUs still dominate this industry and are ahead compared to their private coun-terparts. In upstream operations, Oil and Natural Gas Corporation Limited (ONGC) and Oil India Limited (OIL) still have control over 85 per cent of the total crude production1. In refining, the public sector enterprises control 61.55 per cent2 of refining capacity in India and finally, the marketing of petroleum products is also dominated by PSUs like Indian Oil Corporation Limited (IOCL), BPCL and HPCL with over 94 per cent share in the retailing network (‘RIL, Essar gain share in Oil retail’, 2005). This is primarily because private sector has recently entered the industry. The growth that the private sector has achieved in this short span of time is remarkable and they are already giving sleepless nights to the PSUs. The PSUs are aware of the strength of the companies who have entered this industry.

The facts are that Reliance Petroleum Limited has recently started its refinery in Jamnagar (Gujarat), which will be the world’s largest petroleum refinery, once it starts functioning completely. Essar Oil Limited is a company of the Essar group, which is one of the top five corporate houses in India. Finally, Shell India Markets Private Limited is a subsidiary of the Shell group, which is an oil and petroleum behemoth with origins in the United Kingdom and Netherlands. This company needs no introduction. It is one of the largest and oldest oil companies in the world.

Changing Consumer Orientation

Looking back it can be seen that the Indian petroleum marketing industry has seen different levels of regulations, which resulted in different approaches to marketing. When marketing is being done in a certain way by all players for a very long period of time, it shapes the consumers’ orientation not only towards the product category but also in terms of what they expect in terms of marketing activities and strategies.

For a very long time (approximately four decades), Indian consumers saw petrol being sold through identical marketing mix elements and hence, Indian consumers were habituated to same prices of petrol, orthodox and basic petrol pumps, no advertising (as far as petrol was concerned) and an overall experi-ence of petrol filling which was nothing but dull. But suddenly, after 2002, everything changed for them.

at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 8, 2016gbr.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Global Business Review, 14, 1 (2013): 137–154

Measuring Consumers’ Preferences and Attitudes Towards Branded Petrol 145

Petrol brands were offered with differential prices, supported by celebrity endorsements, sales promo-tion schemes and loyalty programmes; convenience stores, ATMs and fast food joints made petrol pumps ‘happening places’. Companies spent millions on these marketing initiatives and therefore, to understand consumers’ reactions to such changes, it is vital for companies to evaluate the effectiveness of their mar-keting strategies.

As a result, in order to measure any change occurring in consumers’ perception and buying behaviour empirical research is required. The primary idea is to check whether there is any change in consumers’ perception and behaviour in the context of the new marketing practices including new products, new prices, new way of promotions, etc., because if the marketing strategies of the petrol marketing compa-nies are working or are effective, then there has to be a noticeable change in the perceptions and behaviour.

Objective and Scope of This Study: What It Is and What It Is Not

This study was undertaken after almost a decade of all the aforementioned action, with the view-point of assessing the impact of all the marketing action that had taken place. The idea is to under-stand whether the Indian consumer of petrol, who was used to buying petrol as a commodity, has accepted the idea of petrol brands or not. Indian consumers are known to be sensitive to prices and especially towards petrol prices. However, brands are all about differentiation leading to reduced price sensitivity. So, the thought behind the study on which this article is based is to gauge if there has been any decline in the price sensitivity towards petrol after all the branding effort having been put in, or not.

It is important to make clear that this study does not consider the business-to-business (B2B) market, which is a very important segment for petrol marketing companies. This study is confined to the analysis of the business-to-consumer (B2C) segment and aims to measure consumers’ preferences and attitudes towards branded petrol only.

Research Methodology

The research methodology adopted for this particular article is quite simple and straightforward. For the first part of this study (discussed earlier) secondary data was collected and used on information relating to the history and evolution of the Indian petroleum marketing industry, past and present trends in demand, production, consumption and imports and exports.

For the second and more important part of the article, an empirical study was conducted to quan-tify the perception of consumers to branded petrol, which is actually a partial evaluation of the effectiveness of marketing strategies used by petroleum marketing companies from the consumers’ perspective.

On basis of analysis of the information collected above, the study concludes with recommenda-tions that the petroleum marketing companies might consider to improve the effectiveness of their marketing programme. A graphical representation of the research design used for this study is given in Figure 3.

at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 8, 2016gbr.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Global Business Review, 14, 1 (2013): 137–154

146 Anurag Dugar

Hypotheses and Questionnaire for Consumers

To measure the impact of marketing strategies of companies on consumers (which is the acid test for any marketing strategy) a primary study was required and conducted. A questionnaire was framed to collect information and statistical tools were used to analyze the collected data.

To capture and measure changes (if any) in consumer behaviour towards the prices of branded petrol, two hypotheses were formed around various behavioural dimensions observed in Indian consumers. Then questions were framed around them, with scales adopted from previous research studies. This questionnaire was filled by respondents in person. Answers were coded and analyzed with the use of statistical techniques and to verify the hypotheses formed.

Hypothesis 1: Indian consumers are extremely price sensitive as far as petrol is concerned and price is the most important influencing variable in their decision-making criteria. In other words, price is a significant variable influencing the final decision to purchase or not.

Hypothesis 2: There is a strong correlation between price sensitivity and consumers’ preference for non-branded petrol.

Questionnaire

To validate the hypotheses, a questionnaire (see Annexure) was designed. It comprised 10 questions in total and all were aimed at collecting information, directly or indirectly to achieve the aforementioned

Research Methodology

Industry Analysis: Evolution of Industry (Past to Present); Domestic Demand and Supply, Consumption and Gaps In Between

(Secondary Data)

Consumers’ Perception and Preferences to Evaluate the Marketing Strategies Used

(Quantitative Research; Experimental Study; Primary Data)

Recommendations to Petrol Marketers in India

Figure 3. ResearchMethodology

at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 8, 2016gbr.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Global Business Review, 14, 1 (2013): 137–154

Measuring Consumers’ Preferences and Attitudes Towards Branded Petrol 147

purpose of validating the hypotheses. All the questions were close ended and were framed with the help of different scales adapted from research work previously undertaken. In particular, the work of Lichtenstein et al. (1988), Maheswaran and Sternthal (1990), Stayman and Batra (1991) and Sujan and Bettman (1989) were considered, as the product categories or variables measured or scales developed in these seminal works were similar to the requirements of this project. However, only those scales whose reliability and validity scores were high were considered for this study.

The next section details the sources of scales used to develop the questionnaire for this study as well as their scores on reliability and validity along with the expected outcome, which would then help in the choice of analytical tools. But before that, the logic behind framing the questions is explained.

Question 1 to Question 6

These questions were included to get the demographic details of the respondents, so that a profile could be made and correlated with the remaining answers. The idea was to segment the respondents and their responses on basis of demographics in order to increase homogeneity and to understand any particular trends shown by specific segments.

Questions 7 to 10

These questions aimed at analyzing the consumers’ sensitivity towards price, with respect to petrol and to learn about consumers’ perception of their knowledge about the prevailing prices of various brands of petrol. The idea was to check that whether consumers are actually aware of the prices or they just think that they are, and in reality they are not. This can be an interesting finding for marketing companies, as consumers might perceive themselves as sensitive to price, but in reality they are not.

Rationale Behind the Questions

The mechanism adopted was that in one question the respondents were asked to fill in the prevailing prices (as they thought) and this would be cross-checked with the actual prices prevailing at that point of time (with the date of data collection being mentioned in the beginning of the questionnaire so that the prices prevailing on that date could be used to collect the prices prevailing on that date). Since in India prices do not change very frequently, price fluctuation would not be a problem.

For these questions, a price consciousness scale (ideally a three-item five-point Likert-type sum-mated ratings scale) given by Lichtenstein et al. (1988) was used. The reliability was mentioned as 0.66 (LISREL), while the validity checks were not mentioned.

The questionnaire was administered through personal interviews with 900 people in the age group of 22–26 years with equal representation from both genders. This was done looking at the increasing number of female drivers. The questionnaire was filled in by students of MBA colleges charging a fee of more than ` 350,000 for two years. The idea was to get a relatively homogeneous group of respondents in terms of qualification and social class. Moreover, people from this age group and this social class tend to be more brand aware and brand conscious. Even more important is the fact that it is more likely that the respondents in this group might have purchased a new vehicle in the recent past, so they are more likely to care for their vehicle and here, petrol brands might play a role because most brands are positioned on basis of the functional benefit of improving the performance and life of the vehicle.

at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 8, 2016gbr.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Global Business Review, 14, 1 (2013): 137–154

148 Anurag Dugar

Statistical Tool and Analysis

In view of the hypotheses suggested earlier, ‘correlation coefficient’ was chosen for analyzing the rela-tionship between ‘price sensitivity’ and ‘consumer preference’ towards branded and non-branded petrol. It is necessary to mention here that the coefficient of correlation does not necessarily tell us any cause and effect relationship, but merely compares the movement in two data sets and indicates up to what degree they are in tandem with each other. The use of the coefficient of correlation for this study has been made on the assumption that there is a relationship between the two variables, i.e., ‘price sensitivity’ and ‘consumers’ preference for branded or non-branded petrol’. In other words, consumers who are sensitive to price do not give much consideration to the brand, or it may be assumed that they associate brands with high prices. The converse is also true under this assumption.

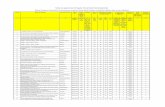

The questionnaire used for data collection is given in the Annexure and the interpretation and expla-nation of the results derived from data analysis is given below. Table 1 presents the summary of the data collected for questions 7, 8 and 9 based on which the hypotheses were validated.

Hypothesis 1

There is a significant impact of price on the perception of consumers, i.e., price is a significant variable influencing the attitude of consumers. Indian consumers are sensitive to the price of petrol.

Results of Tests and Explanation

The analysis does not support this hypothesis as the combined Z value for questions 7, 8 and 9 is greater than the expected Z value at 5 per cent level of significance (+2.64 for right-tail testing), which leads to an interesting conclusion that although people think that they are sensitive to price, in reality they are not.

The analysis gives the individual results question 7 as 2.43 and question 8 as 2.25, which indicates agreement with the first hypothesis, but these two questions are based on perceptions of the customer (i.e., what they think) whereas the individual value of question 9, being 2.92 clearly signifies a rejection of the hypothesis. Question 9 was based on actually what they do.

Hypothesis 2

There is a strong correlation between price sensitivity and customers’ preference for non-branded petrol.

Table 1. SummaryofDataAnalysisforQuestions(Q)Numbered7,8and9

Q7 Q8 Q9 Q7,8,9

Average 3.23 3.2 3.26 9.69StandardDeviation 1.38 1.19 1.19 2.67SE 0.09 0.09 0.09 0.133Z 2.43 2.25 2.92 5.197

Source: Author’sfindings.

at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 8, 2016gbr.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Global Business Review, 14, 1 (2013): 137–154

Measuring Consumers’ Preferences and Attitudes Towards Branded Petrol 149

Results of Tests and Explanation

The correlation value observed between the combined answers of questions 7, 8 and 9 and question 10 was 0.842, which indicates very high correlation between the two variables—‘price sensitivity’ and ‘consumers’ preference towards non-branded petrol’. The inference from this analysis is that those who are actually sensi-tive to price (i.e., who have given the right answer to the question on prevailing prices) are the ones who prefer regular petrol to branded petrol. This means that the people who are sensitive to price do know the prices of different brands and keep them in consideration while making their purchase decision.

Four questions (questions 7, 8, 9 and 10) were asked to measure the price sensitivity of consumers and its impact on their choice of petrol. An attempt was made to understand whether the consumer is actually sensitive to price or he just thinks so. The results clearly indicated that consumers were not exactly clear whether only price affects their decision while buying petrol. However, the interesting part of the find-ings was that consumers perceived themselves to be sensitive to price but they were not able to prove it. They failed to mention the prevailing prices of petrol (which they regularly bought) and prices of petrol do not change very often. The implications of this for petrol marketing companies are set out after the charts showing the summary of responses.

Data Presentation

Question 7

The findings in response to the question, ‘I am aware of price differences between normal petrol and branded petrol’ are set out in Figure 3.

Awarness About Price Differences InNormal & Branded Petrol

Strongly Disagree Disagree Can’t Say Agree Strongly Agree

Agree49%

Can’t Say9%

Disagree7%

Strongly Disagree22%

Strongly Agree13%

Figure 3. AwarenessofPriceDifferencesbetweenNormalandBrandedPetrol

Source: Author’sfindings.

at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 8, 2016gbr.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Global Business Review, 14, 1 (2013): 137–154

150 Anurag Dugar

Question 8

The findings in response to the question, ‘I choose to buy normal petrol and never go for branded petrol until and unless it becomes essential’ are set out in Figure 4.

Figure 4. ChoosingNormalPetroloverBrandedPetrol

Source: Author’sfindings.

Question 9

The findings in response to the question, ‘When it comes to buying petrol, I rely heavily on price’ are set out in Figure 5.

Figure 5. RelianceonPrice

Source: Author’sfindings.

at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 8, 2016gbr.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Global Business Review, 14, 1 (2013): 137–154

Measuring Consumers’ Preferences and Attitudes Towards Branded Petrol 151

23% 15%

18%

11%33%

All Options Right 3 Options Right 2 Options Right

1 Option Right No Option Right

Price Awareness

Figure 6. PriceAwareness—AccuracyofAnswers

Source: Author’sfindings.

Question 10

The findings in response to the question, ‘Based on your memory/guess, please indicate the prevailing prices of regular petrol, Speed, XtraPremium and Power’ are set out in Figure 6.

Implications for Companies

There are two positive outcomes for petrol marketing companies to consider. One, as mentioned earlier, consumers ‘think’ that they are sensitive to price, but in reality they are not. Two, consumers are not exactly clear that price is the only influencing factor in their petrol-buying decision. This also means two other things for the companies to consider.

First, that the marketing strategies of petrol marketing companies show some impact on the consum-ers, as they are gradually shifting away from only pricing and valuing other things as well. Also, it can be concluded that the millions of rupees that companies have spent on marketing has not being effective to the maximum, because the consumers are still not clear on the price factor. Had the marketing strate-gies worked completely, the consumers would have clearly said that price is not the only factor that they consider while buying petrol—this would have meant that there are other things like brands, services, ambience, etc., that would have indicated the complete success of marketing strategies.

at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 8, 2016gbr.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Global Business Review, 14, 1 (2013): 137–154

152 Anurag Dugar

Second, the finding that the consumers perceive that they are sensitive to price, but in reality they are not (this is additional evidence that the above-mentioned interpretation is correct) is clearly a positive signal for the companies because this means consumers can be drawn towards brands, but that is possible only if the companies can give the consumers strong reasons to do so. So, under the circumstances at this point of time, companies should not only focus on advertising and promotions (which they are doing currently), but should also consider creating differentiation and giving consumers strong reasons to buy their brands.

Limitations and Conclusion

In spite of the best of efforts, like other research studies, this study is also not free of limitations. Since the industry is so large and involves so many different functions, businesses and products, with each having sepa-rate regulations, channel networks and marketing communication requirements, that it was difficult to incor-porate every element; moreover it was not advisable. Second, since the consumers of petrol are so large in number (all persons above 18 years of age and driving a vehicle fall in the category of petrol consumers), it was difficult to even attempt capturing their behavioural patterns with respect to petrol.

Another major constraint was the rapidly changing business environment and it was extremely diffi-cult to capture the impact of such a volatile business environment. However, efforts were made to ensure the inclusion of all important variables and it can be said with certainty that knowledge of these hypoth-eses will be extremely valuable for petrol marketing companies, as they would be able to identify which areas of marketing and the target market they need to work on.

Annexure

Questionnaire

Greetings!I am Anurag Dugar and I am conducting a study to analyze and measure consumers’ preferences and

attitudes towards branded petrol. I request you to answer the following questions. This will take approxi-mately 7 minutes.

I’d like to state that I am not selling anything and this study is being done for my doctoral work. Your personal information will not be shared with anyone for any purpose.

Please take the survey only if you drive your own vehicle and please do not take this survey if you own and drive only an electric vehicle.

Thanks!

For Question 1 to Question 6: Tick in the circle given with options – O

1. Gender O male O female2. Age group O 18–28 O 28–38 O 38+

at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 8, 2016gbr.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Global Business Review, 14, 1 (2013): 137–154

Measuring Consumers’ Preferences and Attitudes Towards Branded Petrol 153

3. Your vehicle O scooter* O bike O both4. Daily driving O less then 10 km O 11–20 km O 21 km +5. Profession O student O service O other6. Monthly Expenditure on petrol: O less than `1000 O `1001–5000 O `5001+7. I am aware of price differences between normal petrol and branded petrol:

StronglyDisagree Disagree Can’tSay Agree StronglyAgree1 2 3 4 5

8. I choose to buy normal petrol and never go for branded petrol until and unless it becomes essential:

StronglyDisagree Disagree Can’tSay Agree StronglyAgree1 2 3 4 5

9. When it comes to buying petrol, I rely heavily on price:

StronglyDisagree Disagree Can’tSay Agree StronglyAgree1 2 3 4 5

10. Based on your memory/guess, please fill in the prices of the following in the space provided: –

CurrentPriceof→ Normal Petrol Speed Xtra-Premium Power

InRupeesperlitre

Notes1. Indian Petroleum & Natural Gas Statistics 2010–11, Report of Government of India, Ministry of Petroleum and

Natural Gas, Economic Division, New Delhi, p. 5. Retrieved from - http://petroleum.nic.in/pngstat.pdf2. Indian Petroleum & Natural Gas Statistics 2010–11, Report of Government of India, Ministry of Petroleum and

Natural Gas, Economic Division, New Delhi, p. 5. Retrieved from - http://petroleum.nic.in/pngstat.pdf

ReferencesAblett, J., Baijal, A., Beinhocker, E., Bose, A., Farrell, D., Gersch, U., Greenberg, E., Gupta, S. , & Gupta, S. (2007).

The bird of gold: The rise of India’s consumer market. McKinsey Global Institute, McKinsey & Company, USA. Retrieved from http://www.mckinsey.com/insights/mgi/research/asia/the_bird_of_gold

Bartsch, U., & Müller, B. (2000). Fossil fuels in a changing climate: Impacts of the Kyoto Protocol and developing country participation. Oxford Institute of Energy Studies, Oxford University Press, USA.

Chan, T., Padmanabhan, V., & Seetharaman, P. (2007). An econometric model of location and pricing in the gasoline market. Journal of Marketing Research, 44(4), 622–635.

Chandra, A., & Tappata, M. (2011). Consumer search and dynamic price dispersion: An application to gasoline markets. RAND Journal of Economics, 42(4), 681–704.

*Scooter includes gearless scooters and ‘with-gear’ scooters

at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 8, 2016gbr.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Global Business Review, 14, 1 (2013): 137–154

154 Anurag Dugar

Evans, C. (2011, April). Gasoline. Retrieved from http://abovegroundfuelstoragetanks.com/gasoline/2011/gasoline/ (accessed on 27 December 2011)

Higgins, T. (1998). Marketing petroleum products in Pakistan., Economic Review, 29(8), 29.How was oil formed? (n.d.). Oil crude and petroleum products explained, U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Retrieved from http://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/index.cfm?page=oil_home (accessed on 29 December 2011)

India’s Energy Trilemma. (2012, October 23). Indian Express. Retrieved from http://www.indianexpress.com/news/india-s-energy-trilemma/1020556 (accessed on 5 November 2012)

Ingene, C., & Brown, J. (1987). The structure of gasoline retailing. Journal of Retailing, 63(4), 365–392.Kaul, V.N. (n.d.). New exploration licencing policy. Retrieved from http://pib.nic.in/feature/feyr2001/faug2001/

f100820012.html (accessed on 23 June 2010)Kaur, P. (2004). Petroleum sector: Privatization or monopolization. In Y. Chandra Shekhar (ed.), Indian oil

industry—Transition to deregulation. Hyderabad, India: The ICFAI University Press.Lichtenstein, D.R., Bloch, P.H., & and Black, W.C. (1988). Correlates of price acceptability. Journal of Consumer

Research, 15(September), 243–252.Maheswaran, D., & Sternthal, B. (1990). The effect of knowledge, motivation and type of message on ad processing

and product judgements. Journal of Consumer Research, 17(June), 66–73. RIL, Essar gain share in oil retail (2005, December 21). The Financial Express. Retrieved from http://www.financial

express.com/news/ril-essar-gain-share-in-oil-retail/155012/Oil… Black Gold .. What’s all the fuss about? (2004, April). Rock Talk, Colorado Geological Survey, Volume 7,

Number 2, pp. 1–7. Retrieved from http://geosurvey.state.co.us/pubs/Documents/rtv7n2.pdfStayman, D.M., & Batra, R. (1991). ‘Encoding and retrieval of ad affect in memory. Journal of Marketing Research,

28(May), 232–239.Sujan, M., & Bettman, J.R. (1989). ‘The effects of brand positioning strategies on consumers’ brand and category

perceptions: Some insight from schema research. Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. XXVI, 26(November), 454–467.

at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 8, 2016gbr.sagepub.comDownloaded from