Within-person variations in self-focused attention and negative affect in depression and anxiety: A...

-

Upload

northwestern -

Category

Documents

-

view

4 -

download

0

Transcript of Within-person variations in self-focused attention and negative affect in depression and anxiety: A...

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

This article was downloaded by: [Northwestern University]On: 20 May 2010Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 917270653]Publisher Psychology PressInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Cognition & EmotionPublication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information:http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713682755

Within-person variations in self-focused attention and negative affect indepression and anxiety: A diary studyNilly Mor a; Leah D. Doane b; Emma K. Adam b; Susan Mineka b; Richard E. Zinbarg b; James W.Griffith b; Michelle G. Craske c; Allison Waters c;Maria Nazarian c

a Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem, Israel b Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois, USAc University of California, Los Angeles, California, USA

First published on: 04 December 2008

To cite this Article Mor, Nilly , Doane, Leah D. , Adam, Emma K. , Mineka, Susan , Zinbarg, Richard E. , Griffith, JamesW. , Craske, Michelle G. , Waters, Allison andNazarian, Maria(2010) 'Within-person variations in self-focused attentionand negative affect in depression and anxiety: A diary study', Cognition & Emotion, 24: 1, 48 — 62, First published on: 04December 2008 (iFirst)To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/02699930802499715URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02699930802499715

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf

This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial orsystematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply ordistribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contentswill be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug dosesshould be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss,actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directlyor indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Within-person variations in self-focused attention andnegative affect in depression and anxiety: A diary study

Nilly MorHebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem, Israel

Leah D. Doane, Emma K. Adam, Susan Mineka, Richard E. Zinbarg, and James W. GriffithNorthwestern University, Evanston, Illinois, USA

Michelle G. Craske, Allison Waters, and Maria NazarianUniversity of California, Los Angeles, California, USA

This study examined within-person co-occurrence of self-focus, negative affect, and stress in acommunity sample of adolescents with or without emotional disorders. As part of a larger study, 278adolescents were interviewed about emotional disorders. Later, they completed diary measures overthree days, six times a day, reporting their current thoughts, affect, and levels of stress. Negativeaffect was independently related to both concurrent stress and self-focus. Importantly, the associationbetween negative affect and self-focus was stronger among participants with a recent unipolar mooddisorder, compared to those with an anxiety disorder, comorbid anxiety and depression, or thosewithout an emotional disorder. The implications of these findings to theories of self-focus and itsrole in emotional disorders are discussed.

Keywords: Self-focus; Negative affect; Within-person; Depression; Anxiety.

Self-focused attention, the direction of attention toone’s thoughts and feelings, has been linked tonegative affect (Mor & Winquist, 2002). Accord-ing to self-regulation theories, focusing attentionon oneself instigates a self-evaluative process thatoften results in negative affect (e.g., Carver &Scheier, 1998; Duval & Wicklund, 1972). In thisprocess, people compare their current standing on asalient dimension with a desired standard. Fallingshort of this standard (Duval & Wicklund, 1972)

or perceiving that the standard cannot be met, canlead to negative affect (Carver & Scheier, 1981,1998).

In addition to temporary mood states, self-focushas been implicated in the development andmaintenance of unipolar depression and anxietydisorders. Depressed individuals are said to getstuck in a self-regulatory cycle, unable to disengagefrom unattainable goals. As a result, they engage inperseverative and maladaptive self-focus, which

Correspondence should be addressed to: Nilly Mor, School of Education, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Mount Scopus,

Jerusalem, 91905, Israel. E-mail: [email protected]

This research was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grants R01 MH65651 and R01 MH65652, by the Patricia

M Nielsen Research Chair of the Family Institute at Northwestern University, and by the William T. Grant foundation.

COGNITION AND EMOTION

2010, 24 (1), 48�62

48# 2008 Psychology Press, an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an Informa business

http://www.psypress.com/cogemotion DOI:10.1080/02699930802499715

Downloaded By: [Northwestern University] At: 01:27 20 May 2010

leads to an intensification of negative affect and tomaintenance of depression (Pyszczynski & Greenberg,1987). Similarly, several theories have pointed tothe role that self-focused thinking plays in anxietydisorders (e.g., Ingram, 1990), particularly socialanxiety and generalised anxiety disorder (Clark &Wells, 1995; Wells, 2000). In these models,attention to oneself in times of distress or perceivedthreat intensifies stress responses and anxiety (e.g.,Carver, Blaney, & Scheier, 1979).

Although more research is available on theassociation between unipolar depression and self-focus, empirical work does suggest that emotionaldisorders, both depression and anxiety, are charac-terised by excessive self-focus (e.g., Woodruff-Borden,Brothers, & Lister, 2001). In their meta-analysis,Mor and Winquist (2002) found a consistent linkbetween self-focus and anxiety and depressivedisorders, with depression being more stronglyassociated with self-focus than anxiety. Theresults of this meta-analysis also indicated thatself-focus is more strongly associated with nega-tive affect among individuals who suffer from anemotional disorder than in non-disordered indi-viduals. Thus, not only is self-focus a character-istic of emotional disorders, there is reason tobelieve that engaging in self-focused thinking is amore maladaptive self-regulatory strategy amongemotionally disordered people than in non-clin-ical populations.

Much of the work relating self-focus andemotional disorders has investigated group differ-ences via examination of either trait-like self-focus (e.g., Ingram, Lumry, Cruet, & Sieber,1987) or response to self-focus inductions (e.g.,Zou, Hudson, & Rapee, 2007). Unfortunately,analyses of group differences are limited whentrying to understand the experiences of theindividual person (Borsboon, Mellenbergh, &van Heerden, 2003; Cervone, 2005) and within-person self-regulation dynamics (Cervone, Shadel,Smith, & Fiori, 2006). Online self-regulatorystrategies can be examined in laboratory-basedexperiments, but these designs, too, might notshed light on self-focus in everyday life and on theeffect of self-focus on people’s mood changesacross the day.

A useful way to capture the nature of within-person co-variation in self-focus and negativeaffect in natural settings is to employ a diarymethodology, in which participants report theirexperiences on multiple occasions. This allows forwithin-person analyses of intraindividual associa-tions, between-person analyses of differencesbetween groups in these intraindividual patterns,and examination of contextual factors in naturalsettings (Bolger, Davis, & Rafaeli, 2003).

Several studies have utilised a diary methodol-ogy in the study of daily self-focus and negativeaffect. For example, Wood and her colleagues(Wood, Saltzberg, Neale, Stone, & Rachmiel,1990) examined daily mood, self-focus, andcoping responses in dealing with daily stressfulevents over a period of a month. Between-subjectsanalyses indicated that people who were high inself-focus tended to experience high levels ofnegative affect. However, there was no relation-ship between within-person self-focus and nega-tive affect. In another study, Nezlek (2002) foundthat participants’ daily anxiety levels were asso-ciated with their degree of daily self-focus.

Nolen-Hoeksema, Morrow, and Fredrickson(1993) examined people’s daily reports ofdepressed mood and ruminative reactions tonegative mood across 30 days. Rumination, aparticularly maladaptive form of self-focus,involves repeatedly focusing on one’s mood, itscauses and consequences (Nolen-Hoeksema,1991, 2000). Duration of depressed mood epi-sodes was predicted by the degree of ruminationexhibited at the outset of the mood episode.Unfortunately, diary reports were averaged acrossall days, and findings were observed on a between-person level rather than on a within-person level.

In these studies participants reported theirmood and thoughts only once a day. This typeof assessment does not allow examination ofwithin-day mood fluctuations and their relationto changes in self-focus. It involves retrospectivereports that are based on beliefs and knowledge(Robinson & Clore, 2002) instead of experience-based reports of current mood.

In a recent study (Moberly & Watkins, 2008b)rumination and negative affect were assessed eight

VARIATIONS IN SELF-FOCUS AND NEGATIVE AFFECT

COGNITION AND EMOTION, 2010, 24 (1) 49

Downloaded By: [Northwestern University] At: 01:27 20 May 2010

times a day over a week. Momentary ruminationwas associated with negative affect, particularlyamong individuals who reported high levels ofdepressive symptoms. Although this study pro-vides a good test of within-person self-regulatorymechanisms involving self-focus, several impor-tant questions are left unanswered. First, all of thediary studies of self-focus examined non-clinicalpopulations. Moberly and Watkins’ findingsregarding the effect of depressive symptoms onthe link between self-focus and negative affect, aswell as meta-analytic findings (Mor & Winquist,2002) that this link is stronger in clinical popula-tions, suggest that these within-day associationswould be stronger among individuals sufferingfrom unipolar depression as compared to non-disordered individuals. This hypothesis has notbeen examined directly, and testing it was the firstaim of the current study.

Second, although unipolar depression andanxiety disorders have both been linked to self-focus, the role of self-focus as a regulatorymechanism in anxiety remains unclear. This isbecause anxiety symptoms are often not assessedalong with depressive symptoms (e.g., Moberly &Watkins, 2008b). In addition, the few existingstudies on anxiety suggest that self-focus is morestrongly associated with depressive symptomsthan with anxiety symptoms. Thus, the secondaim of the current research was to examinewhether the association between self-focus andnegative affect is stronger among individuals withan anxiety disorder compared to non-disorderedindividuals.

Third, the experience of stress has beenproposed to moderate the relationship betweenself-focus and negative affect. Self-focus or rumi-nation following a stressful event are thought tobe particularly likely to lead to negative affectbecause they amplify the effect of stress (e.g.,Pyszczynski & Greenberg, 1987; Robinson &Alloy, 2003). Consistent with this, meta-analyticfindings indicate that the relationship betweenself-focus and negative affect is stronger followingstressful episodes (Mor & Winquist, 2002).However, findings from diary studies are incon-sistent. For example, Nezlek (2002, 2005) found

that although daily levels of self-focus and socialstress were positively related (Nezlek, 2002,2005), daily stress did not moderate the relation-ship between anxiety and self-focus (Nezlek,2002). In another study (Flory, Raikkonen,Matthews, & Owens, 2000) dispositional self-focus was related to higher levels of negative affectduring negative social interactions. Thirty min-utes after the negative social interaction, self-focused individuals who experienced high levels ofdysphoria experienced higher levels of negativeaffect than individuals who were not self-focusedand dysphoric. These mixed findings may reflectdifferential associations of anxiety and depressionwith stress and self-focus. A third aim of thecurrent research was to examine the effects ofstress on the association between self-focus andnegative affect. We predicted, following thetheoretical accounts presented above, that self-focus and negative affect would be more stronglyassociated following stressful events.

Thus, the current study was designed to examinewithin-day fluctuations in negative affect and theirrelation to fluctuations in self-focus in an ethnicallydiverse sample of adolescents. We compared thisrelationship in adolescents who had recently beendiagnosed with an emotional disorder and thosewho had not. We further examined the role ofmomentary stress as a potential moderator of therelationship between self-focus and negative affectamong recently depressed, anxious, and non-disordered adolescents.

Focusing on adolescents is important forseveral reasons. First, adolescents experiencemore frequent mood changes and more intenselevels of affect compared to younger and olderpeople (e.g., Larson, Moneta, Richards, & Wilson,2002). Second, compared to the childhood years,adolescence is characterised by a significantincrease in the number of stressful events (Ge,Lorenz, Conger, Elder, & Simons, 1994) as wellas in the rate of anxiety and depression (e.g.,Burke, Burke, Rae, & Reiger, 1991; Hankin et al.,1998). Finally, during adolescence, the correlationbetween stressful life events and negative moodbegins to emerge (Larson & Ham, 1993).

MOR ET AL.

50 COGNITION AND EMOTION, 2010, 24 (1)

Downloaded By: [Northwestern University] At: 01:27 20 May 2010

METHOD

Participants

When initially recruited, participants were high-

school juniors from two large public high schools,

one in a Chicago suburb and one in the greater

Los Angeles area. Students participated in this

study as part of participation in a larger, prospec-

tive study on risk for mood and anxiety disorders:

The Northwestern�UCLA Youth Emotion Pro-

ject. Students were selected to participate in the

longitudinal study based on their scores on the

Neuroticism scale of the Eysenck Personality Ques-

tionnaire-Revised (EPQ-R; Eysenck, Eysenck, &

Barrett, 1985), which was administered to consent-

ing members of the junior class in each of the two

schools. Students who were screened were cate-

gorised as at low, medium, or high risk for

developing emotional difficulties based on scoring

22 dichotomous items from the EPQ-R-N.1

Students who endorsed seven or fewer items

were classified as low scorers. Students who

endorsed more than seven but fewer than 12

items were classified as medium scorers, and those

who endorsed 12 or more items were classified as

high scorers. Using a behavioural high-risk de-

sign, we over sampled students who were at

higher than average risk for the subsequent

development of mood and anxiety disorders*such that 59% of the students invited to partici-

pate in the study scored in the upper third on the

EPQ-R-N. Participants for the prospective study

were recruited in three consecutive yearly cohorts;

the current study uses available data from the first

year of the first two cohorts. Of the 1366 students

screened for the first two cohorts of the study, 923

were invited to participate, 520 agreed to partici-

pate in the longitudinal study, and 491 completed

baseline assessment. Of these, 76.4% were

randomly selected to complete the diary measuresreported in the current study.

Of the 375 individuals from the first twocohorts who were invited, 365 agreed to takepart in the diary study that included daily diariesand saliva samples (saliva samples were intendedfor analysis of salivary cortisol levels*these resultsare presented elsewhere; Doane, Adam, Zinbarg,Mineka, & Craske, 2008). Forty-two participantsprovided unusable data. Thus, data from 278participants were included in the analyses (74%response rate; 203 women). This response rate istypical for diary studies that include cortisolassessment (Adam & Kumari, 2008). The averageage of participants was 16.9 at the time of theclinical interview. The racial�ethnic compositionof this subsample was: 46.5% Caucasian, 11.8%African American, 19.8% Hispanic, 5% Asian/Pacific Islander, 16.9% multiracial or other. Thesedemographic characteristics of the current sub-sample are similar to those of the larger long-itudinal sample from which it was drawn.

Procedure

Participants who agreed to take part in thelongitudinal study attended an initial session inwhich they were interviewed using the StructuredClinical Interview for DSM�IV (SCID-Lifetime;First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1995) todetermine current and past diagnoses of mood andanxiety disorders. They also completed an inter-view about chronic and episodic stress (Hammenet al., 1987), and a number of self-report ques-tionnaires that are not reported here. Participantswere paid $40 for completion of this initialassessment.

Several months following the initial assessment(average 1.8 months, range 1 day to 9 months,with 90% participating within 4 months of theinitial interview) participants were invited to

1 The original EPQ-R-N scale contains 24 items. We excluded the suicide item to reduce IRB-related concerns related to

responding to potentially suicidal participants. We also excluded an item from the analyses about health concerns because in

preliminary factor analyses of our results, this item failed to load onto an overall N (Mor et al., 2008).

VARIATIONS IN SELF-FOCUS AND NEGATIVE AFFECT

COGNITION AND EMOTION, 2010, 24 (1) 51

Downloaded By: [Northwestern University] At: 01:27 20 May 2010

participate in the next part of the study.2 This partincluded filling out diary forms and providingsalivary samples six times a day for three con-secutive weekdays during the school year. Parti-cipants were sent a study packet that included apre-programmed digital wristwatch, and threediary booklets, one for each of the three days oftheir participation. The study procedures wereexplained in detail over the phone and informa-tion about participants’ rise and bed times wasobtained. Participants received a reminder call thenight before they were to start the procedure,during which procedures were reviewed and anyremaining questions answered. Participants wereasked to fill out a diary form immediately as theywoke up, forty minutes afterwards, at bedtime,and three other times throughout the day. Theywore the wristwatches that were pre-programmedto beep signalling the three mid-day diary entries.These beeps occurred at semi-random timesapproximately 3 hours, 8 hours, and 12 hoursafter participants’ typical wakeup times. Beepswere set in relation to participants’ own wakeupand bedtime as this was important for interpreta-tion of other data gathered in the cortisol portionof the study. Participants were asked to indicateon the diary form for each entry the time that theywere beeped as well as the time that theycompleted the diary entry. Because diary entriescorresponded to cortisol samples, which follow adiurnal pattern, significant deviations from thestated time at wakeup, wake up�40 minutes, andbedtime were detected and the corresponding datawere removed.

The diary forms included measures of mood,stress, and self-focus, as well as questions regard-ing who they were with, where they were, and theactivities and thoughts in which they wereengaged immediately before completing the diary(at the time of the beep). Participants firstanswered an open-ended question regarding their

thoughts, then rated their mood, and thenresponded to questions assessing stress level.Each diary entry took up to 5 minutes tocomplete. Upon completion of the task, partici-pants returned the study materials (diaries andcortisol samples) by mail, and were paid $10 fortheir participation in this part of the study.

On average participants completed 16.38 outof the 18 time points. The total number ofreported occasions was 4553, which represents aresponse rate of 91%. This response rate iscomparable to the rate reported in similar diarystudies (e.g., Nezlek, 2002).

Measures

Diagnostic assessment. The Structured ClinicalInterview-Lifetime for DSM�IV (SCID; Firstet al., 1995) was used to assess current andlifetime psychiatric diagnoses of anxiety, mood,psychotic, alcohol and substance use, somatoform,and eating disorders. In this study in addition todiagnostic status, we provided a Clinician SeverityRating (CSR) for each diagnosis, adapted fromthe Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule-Revised (ADIS-R; Di Nardo & Barlow, 1988).The CSR indicates the severity of symptoms andthe level of impairment and distress associatedwith the diagnosis, on a scale of 0 (low severity andno impairment or distress) to 8 (high symptomseverity and significant impairment and distress),where 4 is the cut-off for severity of symptomsthat is clinically significant. Interviewers had allcompleted at least a bachelor’s degree and allcompleted intensive training on the administra-tion of the SCID. Specifically, they received over60 hours of training that included didactic work-shops, practice sessions, observing an advancedclinician conduct an interview, rating audiotapedinterviews and matching gold standard diagnoses(derived via consensus among the PrincipalInvestigators and postdoctoral project directors)

2 Because of the large variability in the time between the initial assessment and the diary assessment, we removed participants

who completed the diary part of the study more than four months after the initial assessment and repeated all of the analysis using

the remaining participants (n�257). Although the results of these analyses were not identical to those reported here, the direction

of the relationships as well as the magnitude of the effects remained very similar. We therefore did not remove these participants

from the sample.

MOR ET AL.

52 COGNITION AND EMOTION, 2010, 24 (1)

Downloaded By: [Northwestern University] At: 01:27 20 May 2010

on at least three of four consecutive interviews,and being observed by a trained clinician on atleast two interviews.

Approximately 10% (n�51) of the interviews(across the first two cohorts of baseline assess-ments) were coded by a second interviewer whoobserved the interview and could ask additionalquestions after the first interviewer left the room.Intraclass correlations (ICC) between interviewersranged between .72 and .94 for mood and anxietydisorders diagnoses, and the correlations between.74 and .97 for the CSR. In this paper we focus ondiagnoses of unipolar depression only, anxietydisorder only, and comorbid unipolar depressionand anxiety disorders. At the time of theirdiagnostic interview, 3.6% of the participants inthis sample met diagnostic criteria for a currentunipolar mood disorder only (unipolar depressiongroup)*including major depressive disorder(1.8%), minor depressive disorder (0.7%), dysthy-mia, and depressive disorder Not OtherwiseSpecified (NOS) (1.1%). Similarly, 8.6% of theparticipants met diagnostic criteria for a currentanxiety disorder only (anxiety disorders group)*including social phobia (4.3%), generalised anxi-ety disorder (2.5%), panic disorder (0.7%), ob-sessive compulsive disorder (0.4%) and anxietydisorder NOS (1.4%). Finally, 4.7% additionalparticipants met diagnostic criteria for havingboth a current anxiety disorder and unipolardepression (comorbid group).

Momentary affect. Participants were asked toindicate in the diaries how much they felt eachof several mood states when they were beeped.The mood states were chosen to reflect bothpositive and negative affect and they included:nervous, lonely, frustrated, worried, irritable,stressed, sad, happy, active, alert, relaxed, andcheerful. Each mood state was rated as 0 (not atall), 1 (a little), 2 (somewhat) or 3 (very much). Toavoid violating the independence assumption offactor analysis, participants’ responses were aggre-gated and the mean responses for the mood itemswere factor analysed. Thus, mean mood responseswere subjected to a factor analysis using anoblimin rotation. Two factors, negative and

positive affect factors, were extracted using paral-lel analysis (Horn, 1965). We report only theresults pertaining to the negative affect factor,which was the dependent variable in our model.The negative affect factor included the items:nervous, lonely, frustrated, worried, irritable,stressed, and sad. The eigenvalue for this rotatedfactor was 5.15 and it accounted for 42.88% of thevariance in mood. Item loadings on this factorranged from 0.89 (worried) to 0.67 (lonely). Thus,to form an overall negative affect score, theseitems were averaged (with unit weighting), with aCronbach alpha reliability of .91.

Momentary self-focus. Participants’ open-endedresponses to the question ‘‘As you were beeped,what was on your mind’’ were coded for thepresence and type of self-focused thinking. State-ments were coded as self-focused if they includedspecific mentions of the self such as ‘‘I; me; myself;mine’’, or described states that refer to the self,without explicit mention of the self such as ‘‘tired;bored; being lonely’’. Statements were coded asself-focused if they referred to the participant’s roleor performance in an activity (e.g., ‘‘my classroompresentation’’), or to descriptions of their currentstate (e.g., ‘‘thinking about how thirsty I am’’).Examples of statements that were coded as self-focused include: ‘‘thinking about how much I haveto do today’’, ‘‘my nose is all stuffed up and I have aheadache’’, and ‘‘wondering if I passed this test’’.Each statement was coded as 1 if it referred to theself, and as 0 if it did not. Coders were blind toparticipants’ mood state or to the existence ofcurrent stressful events and to their history ofemotional disorders. In addition, each thought wasclassified as positive, negative, or neutral. Twentypercent of data were coded by a second coder.Agreement between raters for the coding ofthought focus was 91.3% (Kappa� .80) and forthought valence was 86% (Kappa� .82). Similaropen-ended responses and thought listing mea-sures are commonly used in the assessment of self-focus (e.g., Krohne, Pieper, Knoll, & Breimer,2002; Pyszczynski & Greenberg, 1986) andhave been used in diary studies of self-focusedattention (Csikszentmihalyi & Figurski, 1982;

VARIATIONS IN SELF-FOCUS AND NEGATIVE AFFECT

COGNITION AND EMOTION, 2010, 24 (1) 53

Downloaded By: [Northwestern University] At: 01:27 20 May 2010

Wood et al., 1990). In addition, the overallpercentage of self-focused thoughts in our sampleis similar to that reported by Csikszentmihalyi andFigurski (1982), who used a similar coding scheme.

Momentary stress level. Participants also respondedto the question ‘‘How stressful was the moststressful situation you encountered in the pasthour?’’ on a scale of 0 to 3, when 0 indicated ‘‘notat all ’’ and 3 indicated ‘‘very stressful ’’. Theseresponses were used as a measure of level of stressin the hour immediately prior to each diaryresponse. Stress scores were standardised bothbetween occasions and between persons.

RESULTS

Descriptive statistics

Negative affect. The mean level of negative affectacross all moments and participants was 0.59(SD�0.57), with a possible range of 0 to 3.Thus, on average participants reported low levelsof negative affect. Because this variable waspositively skewed (skewness�1.03), it wassquare-root transformed and values were Wind-sorised at 2.5 standard deviations above the mean.This resulted in a normally distributed variablewith a mean of 0.72 and a standard deviation of0.30. There were no significant differences by age,gender or race in average levels of negative affect.For our analyses, this negative affect outcomevariable was standardised to make it interpretablein standard deviation units. Unless otherwiseindicated, when we refer to negative affect here-after we refer to this transformed, standardisedvariable.3

Self-focus. On average, across all observations,participants’ thoughts were self-focused about

36% (SD�0.48) of the time. Females’ momen-tary thoughts were focused on the self more oftenthan those of males, F(1, 276)�11.32, pB .01.On average, females focused on the self about42% (SD�0.23) of the time whereas malesfocused on the self about 32% (SD�0.23) ofthe time. There were no significant differences byage or race. On average participants engaged innegative self-focus about 6% (SD�0.08) of thetime, positive self-focus 1% (SD�0.03) of thetime, and neutral self-focus 28% (SD�0.19) ofthe time. Because only neutral self-focused state-ments were common enough to use in theanalyses, and to prevent confounding of self-focusand valence, only neutral self-focused statementswere analysed.4

Stress level. On average, across all moments andparticipants, the mean level of stress was about0.60 (SD�0.39), with an observed range of 0�2.43 out of a possible range of 0�3 with 0indicating no or lowest levels of stress and 3indicating high levels of stress. Thus, on averageparticipants reported low levels of momentarystress. There were no significant differences inaverage levels of stress by gender, age or race.

Analytic approach

The associations among negative affect, self-focus, level of stress and emotional disorderswere tested using hierarchical linear modelling(HLM). In our model, level of negative affect foreach person at each moment was the outcomevariable, and it was predicted by both time-varying predictors (changing from moment tomoment, included at Level 1 of the model) andstable predictors (constant across all moments,included at Level 3). No predictors were includedat Level 2 (the day level); however, the nesting of

3 These analyses were repeated with untransformed negative affect scores. Although, as expected, the regression coefficients

were not identical to the ones reported here, the direction of the relationships as well as the magnitude of the effects remained very

similar.4 To examine whether the inclusion of statements that refer to one’s emotional or physical state inflates the association between

self-focus and affect, we repeated all of the analyses when these statements were eliminated from the data. Because the pattern of

results remained the same, we left these statements as part of participants self-focus repertoire.

MOR ET AL.

54 COGNITION AND EMOTION, 2010, 24 (1)

Downloaded By: [Northwestern University] At: 01:27 20 May 2010

moments within days is accounted for within themodel.

We constructed the following model to test ourpredictions:

Level 1:

Negative affecttij�p0ij�p1ijSelf -focustij

�p2ijStresstij

�p3ij(Self -focus

�Stress)tij�etij

Level 2:

p0ij�b00j�r0ij

p1ij�b10j�r1ij

p2ij�b20j�r2ij

p3ij�b30j�r3ij

Level 3:

b00j�g000�g001Genderj

�g002(Depression�Anxiety)j

�g003Depressionj�g004Anxietyj�00j

b10j�g100�g101Genderj

�g102(Depression�Anxiety)j

�g103Depressionj�g104Anxietyj�10j

b20j�g200�g201Genderj

�g202(Depression�Anxiety)j

�g203Depressionj�g204Anxietyj�20j

b30j�g300�g301Genderj

�g302(Depression�Anxiety)j

�g303Depressionj�g304Anxietyj�30j

In this model, negative affect is predicted byself-focus, stress, and their interaction5 (Level 1predictors). In addition, we examined whether thedirection and strength of associations betweenthese Level 1 predictors and negative affect, varysignificantly according to person�level character-istics (Level 3), namely gender, and the presenceof unipolar depression, anxiety disorders (both

coded as dichotomous variables), and comorbidanxiety and depression (computed as the productof the anxiety and depressive disorders variables).The results of the tested model are shown inTable 1 and are outlined below.

The association between momentary self-focus and negative affect

To replicate prior findings, we first examinedwhether participants would be more likely toexperience negative affect when they engage inself-related thoughts, as compared to when theirthoughts are not self-focused. Indeed, participantsexperienced higher levels of negative affect whenthey engaged in self-focus as compared to timeswhen they were not self-focused, g100� .05, SE�0.02, t(269)�2.42, pB .02.

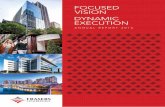

We subsequently examined the moderatingeffect of having been diagnosed with unipolardepression, an anxiety disorder, or both, on thelink between self-focus and negative affect. Wediscuss each effect separately. These moderatingeffects are all presented in Figure 1. For claritypurposes, we describe the effects of unipolardepression, anxiety and comorbid anxiety andunipolar depression, separately.

The role of unipolar depression

We examined whether having a diagnosis ofunipolar depression was associated with averagelevels of negative affect. We then examined ourfirst hypothesis that having been recently diag-nosed with unipolar depression moderates therelationship between self-focus and negative affectat the momentary level. Individuals who wererecently diagnosed with unipolar depression didnot experience higher average levels of negativeaffect compared to non-disordered individuals,g003� .36, SE�0.24, t(269)�1.49, pB .13.However, as predicted, the association between

5 To examine the possibility that autocorrelation between successive observations may have affected the reported results, we

included in the model the time of day as well as time of day squared as level 1 predictors of negative affect. Because the direction of

the associations as well as the magnitude of the effects remained very similar, we did not include the time of day variables in the

model we report in the manuscript.

VARIATIONS IN SELF-FOCUS AND NEGATIVE AFFECT

COGNITION AND EMOTION, 2010, 24 (1) 55

Downloaded By: [Northwestern University] At: 01:27 20 May 2010

self-focus and negative affect was stronger amongthose who had recently been diagnosed withunipolar depression than among non-disorderedindividuals, g103� .27, SE�0.13, t(269)�2.03,pB .04.

The role of anxiety disorders

Again, we first examined whether having adiagnosis of an anxiety disorder was associatedwith average levels of negative affect. We thenexamined whether having been recently diagnosedwith an anxiety disorder moderates the relation-ship between self-focus and negative affect at themomentary level. Individuals who were recentlydiagnosed with an anxiety disorder did experiencehigher average levels of negative affect comparedto non-disordered individuals, g004� .51, SE�0.13, t(269)�4.10, pB .00. However, the asso-ciation between self-focus and negative affect wasnot stronger among those who had recently been

diagnosed with an anxiety disorder than amongnon-disordered individuals, g104�� .004, SE�0.07, t(269)��0.06, pB .95.

The role of comorbid unipolar depressionand anxiety disorders

Comorbid anxiety and unipolar depression didnot significantly predict momentary negativeaffect, nor did it predict the association betweenself-focus and negative affect. It is important toremember that the comorbid depression andanxiety group was very small (n�13) and diag-nostically diverse.

The role of stress

We first examined whether concurrent stresspredicts negative affect. We then examined ourprediction that self-focus would interact withmomentary stress to predict negative affect.When examining both the main effect of stress

Table 1. Negative affect predicted from self-focus, stress level, and emotional disorders (n�278)

Variable Coefficient SE

Level 1 intercept

Intercept, g000 .01 0.04

Gender, g001 �.18* 0.09

Comorbid disorder, g002 �.22 0.32

Mood disorder, g003 .36 0.24

Anxiety disorder, g004 .51** 0.13

Self-focus

Intercept, g100 .05* 0.02

Gender, g101 .03 0.05

Comorbid disorder, g102 �.23 0.21

Mood disorder, g103 .27* 0.13

Anxiety disorder, g104 .00 0.07

Stress level

Intercept, g200 .51** 0.02

Gender, g201 �.08* 0.03

Comorbid disorder, g202 .10 0.14

Mood disorder, g203 �.04 0.09

Anxiety disorder, g204 �.02 0.05

Self-focus�Stress level

Intercept, g300 �.06** 0.02

Gender, g301 .07 0.05

Comorbid disorder, g302 .02 0.15

Mood disorder, g303 �.10 0.10

Anxiety disorder, g304 .00 0.05

Note: *pB.05; **pB.01. Results were similar when run with race dummy variables, SES, and age.

MOR ET AL.

56 COGNITION AND EMOTION, 2010, 24 (1)

Downloaded By: [Northwestern University] At: 01:27 20 May 2010

and its interaction with self-focus, we also testedwhether Level 3 variables (a diagnosis of anxietydisorders or unipolar depression, and gender)moderated these effects. Momentary stress was asignificant predictor of negative affect, g200� .51,SE�0.02, t(269)�33.31, pB .00. Thus, partici-pants experienced higher levels of negative affectwith increasing levels of stress. Although havingbeen recently diagnosed with an emotional dis-order (either depression, anxiety, or both) did notmoderate the effect of stress on negative affect,gender did, g201�� .08, SE�0.03, t(269)��2.48, pB .01. Thus, the effect of stresson negative affect was stronger among femalesthan among males. Interestingly, the interactionbetween self-focus and stress was negatively asso-ciated with negative affect, g300�� .06, SE�0.02, t(269)��3.26, pB .00. Thus, when parti-cipants were self-focused they experienced lowerlevels of negative affect with increasing stress.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we replicated previous findingsdemonstrating that momentary self-focus is asso-ciated with concurrent levels of negative affect.More importantly, as predicted, this association

was stronger among individuals who had recentlybeen diagnosed with a depressive disorder com-pared to those who had not. This moderatingeffect was unique to a diagnosis of a depressivedisorder and was not found for a diagnosis of ananxiety disorder or for comorbid anxiety anddepression. Instead, individuals with a recentdiagnosis of an anxiety disorder reported higheraverage levels of momentary negative affect,regardless of self-focus. Finally, momentary stresswas associated with higher levels of negativeaffect, particularly among females. However, in-creasing levels of stress during times of self-focuswere associated with lower levels of negativeaffect. Our findings contribute to the under-standing of the concept of self-focus, to thedifferential role it serves in depression and anxiety,and to the possible function of stress in within-day fluctuations in negative affect. In whatfollows, we examine the implications of ourfindings to each of these domains.

Implications for theories of self-focus

Despite its central role in theories of personality,self-regulation, social cognition, and psycho-pathology, the construct of self-focus remainscontroversial and elusive. In particular, the question

-0.4

-0.2

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

Non Self Focus Self Focus

Neg

ativ

e A

ffec

t (i

n SD

)

Unipolar Depression

Anxiety Disorder

ComorbidDepression/Anxiety

No Disorder

Figure 1. Negative affect (in SD) by self-focus for individuals with depression, anxiety, comorbid depression/anxiety, and no emotional

disorder.

VARIATIONS IN SELF-FOCUS AND NEGATIVE AFFECT

COGNITION AND EMOTION, 2010, 24 (1) 57

Downloaded By: [Northwestern University] At: 01:27 20 May 2010

of whether and under which circumstances self-focus is maladaptive has attracted much attention(e.g., Ingram, 1990; Mor & Winquist, 2002;Watkins, 2008). A fundamental issue in thisdebate has been whether self-focus is maladaptiveby itself, irrespective of its valence. Early ap-proaches viewed self-focus as generally aversive,because it most likely brings to the forefrontundesired discrepancies between the current stateof the self and desired standards (Duval &Wicklund, 1972). In contrast, later approachesargued that self-focus is aversive only when it isnegatively valenced. Self-focus has been thoughtbe to aversive primarily if it involves negative self-aspects or occurs following negative events (e.g.,Carver & Scheier, 1998; Mor & Winquist, 2002;Watkins, 2008). Because in the current study onlyneutral self-focused statements were included, itwas possible to separate valence and self-focus.Our findings that neutral self-focus is related tonegative affect support initial views of self-focusas being maladaptive regardless of valence. Thesefindings may imply that additional factors, such asthe flexibility with which self-focus is used(Muraven, 2005), or whether it involved analyticversus experiential modes of thinking (Watkins,Moberly, & Moulds, 2008) may determinewhether self-focus is adaptive or not.

Implications for emotional disorders andstress

To our knowledge, this study is the first todemonstrate differential effects of unipolardepression and anxiety disorders on within-dayassociations between self-focus and negativeaffect. The stronger association between self-focusand negative affect among individuals who haverecently been diagnosed with a mood disorder isin line with theoretical accounts of depression as adisorder of self-regulation (e.g., Carver & Scheier,1998). These theories assert that depressedindividuals strive for unattainable goals, showdifficulty disengaging from these goals andinstead engage in a repetitive cycle of self-focusedthinking (e.g., Papadakis, Prince, Jones, &Strauman, 2006; Pyszczynski & Greenberg,

1987). Our findings are consistent with Morand Winquist’s (2002) meta-analytic findings ofa stronger association between self-focus andnegative affect in clinical populations comparedto non-clinical populations. A similar pattern wasalso reported by Moberly and Watkins (2008),where within-day associations of self-focus andnegative affect were associated with symptoms ofdepression.

Recent evidence suggests that depressed in-dividuals engage in particularly unproductiveforms of self-focus. Several studies have shownthat depression is specifically associated withbrooding, the maladaptive component of rumina-tion, which involves passively focusing on one’ssymptoms and on the discrepancy betweenone’s current state and an unachieved standard(Treynor, Gonzales, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2003).For example, Burwell and Shirk (2007) reportedthat in an adolescent sample, higher levels ofdepressive symptoms were associated with brood-ing but not with active reflection in an attempt togain insight. Furthermore, Joormann, Dkane, andGotlib (2006) examined the diagnostic specificityof brooding. They found that individuals diag-nosed with major depressive disorder reportedhigher levels of brooding compared to individualswith social phobia or normal controls. Given thesefindings, it is likely that the stronger associationbetween self-focus and negative affect amongrecently depressed youth in our study reflects theirtendency to use harmful and maladaptive forms ofself-focus. Because in the current research self-focus was assessed using participants’ open-endedresponses, we were unable to discriminate betweendifferent types of self-focus. Thus, this assumptionregarding a potential cause for the strong within-person association between negative affect andself-focus should be tested in future research.

In contrast to depression, having an anxietydisorder was directly linked to negative affect, andnot through the mediation of self-focus. Thisfinding may support recent work about thestructure of emotional disorders in youth. Thiswork has suggested that among youth, anxiety is apure manifestation of negative affect (Anderson &Hope, 2008) whereas depression is not always

MOR ET AL.

58 COGNITION AND EMOTION, 2010, 24 (1)

Downloaded By: [Northwestern University] At: 01:27 20 May 2010

associated with negative affect (e.g., Chorpita,Plummer, & Moffitt, 2000). These findings arealso partly consistent with the meta-analyticfinding that depression is more strongly associatedwith self-focus than anxiety is.

It is important to remember that anxietydisorders are heterogeneous with respect to theirrelation to self-focus. While some disorders, suchas generalised anxiety disorder or social phobia,have been linked both theoretically and empiri-cally to self-focus (e.g., Clark & Wells, 1995;Wells, 2000), very little research links otheranxiety disorders, such as panic disorder to self-focus (e.g., Borden, Lowenbraun, Wolff, & Jones,1993). Therefore, the diagnostic variability ofboth the pure anxiety and the comorbiddepression�anxiety groups in this study, mayexplain why self-focus and negative affect werenot more strongly interlinked in these groupscompared to participants who did not suffer froman anxiety disorder. Unfortunately due to thesmall number of participants in each of the twoanxiety groups (pure and comorbid) we wereunable to conduct separate analyses testing themoderating effect of the different anxiety disor-ders. Future research should examine the relation-ship between self-focus and negative affectseparately for the various anxiety disorders.

The association between momentary stress,self-focus, and emotional disorders remains some-what unclear. Stress and self-focus were indepen-dent predictors of momentary negative affect.However, the effect of the interaction betweenstress and self-focus on negative affect wasunpredicted, suggesting that during times ofself-focus higher negative affect is associatedwith decreasing levels of stress. In interpretingthese results, it is important to consider the strongmain effect of stress on negative affect and thatthis interaction is observed above and beyond themain effects of stress and self-focus, and that it ispossible that this effect represents a suppressioneffect (Holling, 1986). Because this finding isunexpected and difficult to interpret, at this time,we hesitate to interpret the observed interactionof stress and self-focus and encourage furtherresearch to explore this association.

Several limitations of the study’s population,procedures, and measures should be acknowl-edged. First, we used a high-risk high-schoolsample. As a result, only few participants metcriteria for emotional disorders, and this prohib-ited making firm conclusions regarding the role ofanxiety as a moderator of the association betweenself-focus and affect. Having a predominantlyfemale sample with relatively high levels ofneuroticism, may have compromised the gener-alisability of the results. Second, two procedurallimitations should be noted. Self-focus and nega-tive affect were assessed several months after thediagnostic evaluation. Although removing parti-cipants with a long lag between the assessmentsand including the time between assessments in themodel did not affect the main results, ourconclusions are nevertheless limited to the impactof recent rather than current disorders. In addition,a full week of data collection, the use of a fullyrandom beep schedule, and additional beeps perday, could provide a more representative samplingof daily experiences as well as allow for theexamination of lagged effects (e.g., Moberly &Watkins, 2008a). Third, we note some measure-ment limitations. Self-focus was assessed usingpaper and pencil, open-ended responses, whichcan be prone to retrospective biases. Althoughthere was no evidence for significant retrospectivereporting, using electronic devices for data collec-tion may have been advantageous. Similarly,although comparable to measures used in otherdiary studies (e.g., Moberly & Watkins, 2008a)our measure of momentary stress may haveconfounded objective stress with the individual’semotional response (Monroe, 2008). Futureresearch should further disentangle daily stressand emotional experience.

Nevertheless, the current study, using a largehigh-school sample, utilising multiple concurrentassessment points, and clinical diagnoses, contri-butes significantly to our understanding of theinterplay of self-focus, negative affect, and emo-tional disorders. It provides clear evidence thatself-focus is associated with the experience of dailynegative affective states, and that this associationis stronger for individuals with a recent diagnosis

VARIATIONS IN SELF-FOCUS AND NEGATIVE AFFECT

COGNITION AND EMOTION, 2010, 24 (1) 59

Downloaded By: [Northwestern University] At: 01:27 20 May 2010

of unipolar depression. By examining within-daycovariation of self-focus and negative affect,rather than relying on between-person associa-tions, the current results take us closer to under-standing the causal relations between thesecognitive and affective processes. To furtherexplore the causal role of self-focus in negativeaffect and emotional disorders, studies thatexamine time precedence of self-focus should beconducted, as well as prospective studies thatexamine the role of within-day covariation ofself-focus and negative affect in the developmentand maintenance of emotional disorders.

Manuscript received 30 January 2008

Revised manuscript received 11 July 2008

Manuscript accepted 10 September 2008

First published online 4 December 2008

REFERENCES

Adam, E. K., & Kumari, M. (2008). Assessing salivary

cortisol in large-scale, epidemiological research. Manu-script submitted for publication.

Anderson, E. R., & Hope, D. A. (2008). A review ofthe tripartite model for understanding the linkbetween anxiety and depression in youth. Clinical

Psychology Review, 28, 275�287.Bolger, N., Davis, A., & Rafaeli, E. (2003). Diary

methods: Capturing life as it is lived. Annual Review

of Psychology, 54, 579�616.Borden, J. W., Lowenbraun, P. B., Wolff, P. L., &

Jones, A. (1993). Self-focused attention in panicdisorder. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 17, 413�425.

Borsboom, D., Mellenbergh, G. J., & van Heerden, J.(2003). The theoretical status of latent variables.Psychological Review, 110, 203�219.

Burke, K. C., Burke, J. D., Rae, D. S., & Reiger, D. A.(1991). Comparing age of onset of major depressionand other psychiatric disorders by birth cohorts infive US community populations. Archives of General

Psychiatry, 48, 789�795.Burwell, R. A., & Shirk, S. R. (2007). Subtypes of

rumination in adolescence: Associations betweenbrooding, reflection, depressive symptoms, and cop-ing. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent

Psychology, 36, 56�65.

Carver, C. S., Blaney, P. H., & Scheier, M. F. (1979).

Focus of attention, chronic expectancy, and

responses to a feared stimulus. Journal of Personality

and Social Psychology, 37, 1186�1195.Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M. F. (1981). Attention and

self-regulation: A control-theory approach to human

behavior. New York: Springer-Verlag.Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M. F. (1998). On the self-

regulation of behavior. New York: Cambridge

University Press.Cervone, D. (2005). Personality architecture: Within-

person structures and processes. Annual Review of

Psychology, 56, 423�452.Cervone, D., Shadel, W. G., Smith, R. E., & Fiori, M.

(2006). Self-regulation: Reminders and suggestions

from personality science. Applied psychology: An

international review, 55, 333�385.Chorpita, B. F., Plummer, C. M., & Moffitt, C. E.

(2000). Relations of tripartite dimensions of emo-

tion to childhood anxiety and mood disorders.

Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 28, 299�310.Clark, D. M., & Wells, A. (1995). A cognitive model of

social phobia. In R. G. Hiemberg, M. R. Liebowitz,

D. A. Hope, & F. R. Schneier (Eds.), Social phobia:

Diagnosis, assessment and treatment (pp. 69�95). New

York: Guilford Press.Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Figurski, T. J. (1982). Self-

awareness and aversive experience in everyday life.

Journal of Personality, 50, 15�28.Di Nardo, P. A., & Barlow, D. H. (1988). Anxiety

Disorders Interview Schedule-Revised (ADIS-R).

Albany, NY: Phobia and Anxiety Disorders Clinic.Doane, L. D., Adam, E. K., Zinbarg, R., Mineka, S., &

Craske, M. (2008). Cumulative affective strain and

cortisol levels in adolescents at risk for mood and anxiety

disorders. Manuscript in preparation.Duval, S., & Wicklund, R. (1972). A theory of objective

self-awareness. New York: Academic Press.Eysenck, S. B. G., Eysenck, H. J., & Barrett, P. (1985).

A revised version of the psychoticism scale. Person-

ality and Individual Differences, 6, 21�29.First, M. B., Spitzer, R. L., Gibbon, M., & Williams, J.

B. W. (1995). Structured clinical interview for DSM-

IV Axis I disorders, SCID-I/NP, version 2.0 (Non-

patient edition). New York: New York State

Psychiatric Institute.Flory, J. D., Raikkonen, K., Matthews, K. A., &

Owens, J. F. (2000). Self-focused attention and

mood during everyday social interactions. Personality

and Individual Differences, 26, 875�883.

MOR ET AL.

60 COGNITION AND EMOTION, 2010, 24 (1)

Downloaded By: [Northwestern University] At: 01:27 20 May 2010

Ge, X., Lorenz, F. O., Conger, R. D., Elder, G. H., &Simmons, R. L. (1994). Trajectories of stressful life

events and depressive symptoms during adolescence.

Developmental Psychology, 30, 467�483.Hammen, C. L., Adrian, C., Gordon, D., Burge, D.,

Jaenicke, C., & Hiroto, D. (1987). Children of

depressed mothers: Maternal strain and symptompredictors of dysfunction. Journal of Abnormal

Psychology, 96, 190�198.Hankin, B. L., Abramson, L. Y., Moffit, T. E., Silva, P.

A., McGee, R., & Angell, K. E. (1998). Develop-

ment of depression from preadolescence to youngadulthood: Emerging gender differences in a 10-

year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal

Psychology, 107, 128�140.Holling, H. (1986). A classification of trivariate

regression models. Biometrical Journal, 28, 783�790.Horn, J. L. (1965). A rationale and technique for

estimating the number of factors in factor analysis.

Psychometrika, 30, 179�185.Ingram, R. E. (1990). Self-focused attention in clinical

disorders: Review and a conceptual model. Psycho-

logical Bulletin, 107, 156�176.Ingram, R. E., Lumry, A. E., Cruet, D., & Sieber, W.

(1987). Attentional processes in depressive disor-

ders. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 11, 351�360.Joormann, J., Dkane, M., & Gotlib, I. H. (2006).

Adaptive and maladaptive components of rumina-

tion? Diagnostic specificity and relation to depres-sive biases. Behavior Therapy, 37, 269�280.

Krohne, H. W., Pieper, M., Knoll, N., & Breimer, N.(2002). The cognitive regulation of emotions: The

role of success versus failure experience and coping

dispositions. Cognition and Emotion, 16, 217�243.Larson, R., & Ham, M. (1993). Stress and ‘‘storm and

stress’’ in early adolescence: The relationship of

negative events with dysphoric affect. Developmental

Psychology, 29, 130�140.Larson, R. W., Moneta, G., Richards, M. H., &

Wilson., S. (2002). Continuity, Stability, and

change in daily emotional experience across

adolescence. Child Development, 73, 1151�1165.Moberly, N. J., & Watkins, E. R. (2008a). Ruminative

self-focus and negative affect: An experience sam-pling study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 117,

314�323.Moberly, N. J. Watkins, E. R. (2008b) Ruminative self-

focus, negative life events, and negative affect.

Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46, 1034�1039.

Monroe, S. M. (2008). Modern approaches to con-

ceptualizing and measuring human life stress.

Annual Review of clinical Psychology, 4, 33�52.Mor, N., & Winquist, J. (2002). Self-focused attention

and negative affect: A meta-analysis. Psychological

Bulletin, 128, 638�662.Mor, N., Zinbarg, R. E., Craske, M. G., Mineka, S.,

Uliaszek, A., Rose, R., et al. (2008). Evaluating the

invariance of the factor structure of the EPQ-R-N

among adolescents. Journal of Personality Assessment,

90, 66�75.Muraven, M. (2005). Self-focused attention and the

self-regulation of attention: Implications for person-

ality and pathology. Journal of Social and Clinical

Psychology, 24, 382�400.Nezlek, J. B. (2002). Day-to-day relationships between

self-consciousness, daily events, and anxiety. Journal

of Personality, 70, 105�131.Nezlek, J. B. (2005). Distinguishing affective and non-

affective reactions to daily events. Journal of

Personality, 73, 1539�1568.Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1991). Responses to depression

and their effects on the duration of depressive

episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100, 569�582.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2000). The role of rumination in

depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive

symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109, 504�511.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Morrow, J., & Fredrickson, B. L.

(1993). Response styles and the duration of episodes

of depressed mood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology,

102, 20�28.Papadakis, A. A., Prince, R. P., Jones, N. P., &

Strauman, T. J. (2006). Self-regulation, rumination,

and vulnerability to depression in adolescent girls.

Development and Psychopathology, 18, 815�829.Pyszczynski, T., & Greenberg, J. (1986). Evidence for a

depressive self-focusing style. Journal of Research in

Personality, 20, 95�106.Pyszczynski, T., & Greenberg, J. (1987). Self-regula-

tory perseveration and the depressive self-focusing

style: A self-awareness theory of reactive depression.

Psychological Bulletin, 201, 122�138.Robinson, M. S., & Alloy, L. B. (2003). Negative

cognitive styles and stress-reactive rumination inter-

act to predict depression: A prospective study.

Cognitive Therapy and Research, 27, 275�291.

VARIATIONS IN SELF-FOCUS AND NEGATIVE AFFECT

COGNITION AND EMOTION, 2010, 24 (1) 61

Downloaded By: [Northwestern University] At: 01:27 20 May 2010

Robinson, M. D., & Clore, G. L. (2002). Belief andfeeling: Evidence for an accessibility model ofemotional self-report. Psychological Bulletin, 128,934�960.

Treynor, W., Gonzalez, R., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S.(2003). Rumination reconsidered: A psychometricanalysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 27, 247�259.

Watkins, E. R. (2008). Constructive and unconstructiverepetitive thought. Psychological Bulletin, 134, 163�206.

Watkins, E. R., Moberly, N. J., & Moulds, M. L.(2008). Processing mode causally influences emo-tional reactivity: Distinct effects of abstract versusconcrete construal on emotional response. Emotion,8, 364�378.

Wells, A. (2000). Emotional disorders and meta-cogni-

tion: Innovative cognitive therapy. Chichester, UK:

Wiley.Wood, J. V., Saltzberg, J. A., Neale, J. M., Stone, A.

A., & Rachmiel, T. B. (1990). Self-focused atten-

tion, coping responses, and distressed mood in

everyday life. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 58, 1027�1036.Woodruff-Borden, J., Brothers, A. J., & Lister, S. C.

(2001). Self-focused attention: Commonalities

across psychopathologies and predictors. Behavioural

and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 29, 169�178.Zou, J. B., Hudson, J. L., & Rapee, R. M. (2007). The

effect of attentional focus on social anxiety. Beha-

viour Research and Therapy, 45, 2326�2333.

MOR ET AL.

62 COGNITION AND EMOTION, 2010, 24 (1)

Downloaded By: [Northwestern University] At: 01:27 20 May 2010