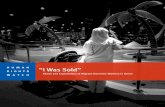

When Iran's Abadan was Capital of the World

Transcript of When Iran's Abadan was Capital of the World

PART ONE:WHAT IF OIL

IS MAGIC?Sure, we are used to think of oil as a curse dis-guised as a blessing: as oil is extracted and refined, it turns into black gold for the few and misery for the many. Oil reeks of pollution and corrupt autocrats, it smothers democratic forces. Oil makes a nation addicted to non-renewable re-sources and dependent on a global market out of its control. Oil spoils nature, society and politics.

And yet the forgotten story of a city in Iran re-minds us that oil can also be the stuff of imagina-tion, bringing life to a place, making people dream and remember. This is the story of a city that was brought into being by oil, almost killed by oil, and yet still understands itself through oil.

....

“It was with oil from here that the Europeans were able to lit up their streets,” my host asserts while his ancient, rusting car struggles on a dark dusty road full of potholes during one of my recent trips to Abadan. “Without Abadan, Europe would still be in darkness!”

We are in Khuzestan Province in southwest-ern Iran along the border with Iraq, where the Euphrates, Tigris and Karun rivers flow together and into the Persian Gulf. Abadan was once home to the world’s biggest oil refinery. Around the refinery was one of the Middle East’s most modern and diverse cities.

Today, Abadan is a mere shadow of its former self. Revolution, war and stagnation left the city

hollowed out and forgotten. Its citizens recollect the past with a nostalgia that runs thick in the cultural veins of the city.

When I first visited Abadan, it was to learn about its violent past under the British-owned oil company that ran Abadan as a virtual colony in the first half of the twentieth century. I heard echoes of the narratives I was looking for: how oil brought British imperialism and global petro-capitalism into Iran; how oil created and crushed labor movements; and how oil consolidated the Shah’s dictatorship.

And yet, time and again, Abadan refused to tell me the simple story I wanted to hear. One Abadani after another preferred to tell me fond memories of peaceful co-existence, cultural blos-soming, material prosperity, welfare and well-being with the oil industry as the driving force.

There was a dissonance between the records of injustice I had unearthed in the historical archives, and the romanticized past I was pre-sented with in present-day Abadan. Nostalgia for the past, sweet and bitter, seemed to saturate society. I wanted to understand why.

The longing for a time or place in the past is not necessarily regressive: it demands active remembrance and amnesia; it involves selec-tive rearrangement and creative reproduction. Rather than being unmodern, nostalgia is part of modernity: it enables one to stand outside of the present and criticize ‘the modern’. It gives momentary respite from the present, but it also suggests possible futures.

In a fast century, Abadan has seen oppression, war and upheaval enough to trigger a desire for escapism and re-enchantment. But rather than

Abadan: Oil City Dreams and the Nostalgia for Past Futures in IranRasmus Christian Elling

This three-part essay is partially a reworked version of: Elling, Rasmus Christian. 2014. ‘Oliebyen midt i en jazztid: Nostalgi, magi og det moderne i Abadan’, Tidsskriftet Kulturstudier, 2/24 (download here).The series was published online by Ajam Media Collective (ajammc.com) and is here reproduced as a single PDF file.

Fig. 1: Almost picture-perfect Abadan (1950s).

Fig. 2: Parts of Abadan are today still marked by the Iran-Iraq War (1980-88).

a mere psychological reaction, nostalgia can be visualized as a contested terrain on which Abadanis recreate their history. At the geograph-ical, historical and social center of that terrain stands the towering presence of oil.

The dominant literature mostly treats oil in terms of economy or geopolitics: it is a com-modity, and as money, it impacts on states and politics. More nuanced recent research has instead focused on the social and cultural impact of oil as seen from below, within communities. By conceding oil historical agency on the border between man and nature, this research enables us to better understand its role in shaping and affecting people, classes and cities, myths and emotions.

In this three-part essay, we will look at Abadani nostalgia through memoirs and local histo-ries — the nostalgic books, I call them — and through fragments from interviews I conducted in Abadan in 2012.

These memoirs, memories and fragments are analyzed as if they were oil products: through them, we can understand the magic power with which a natural resource can move and change people, create and nearly destroy a city — and yet continue to sustain its imagination and self-understanding.

Abrupt leaps of the pastWhen flying into Abadan at night, the oil refinery stands out as a visible center from which the city sprawls, lit up in intervals by flames gushing from the oil towers.

It is hard to imagine that just over a hundred years ago, the little island of Abadan only con-tained villages of Arabic-speaking tribes living in mud huts, growing date palms, fishing and trad-ing with the neighboring towns. Even though oil literally seeped up through the ground and into homes across the province, no-one probably guessed its impending global significance.

The unnoticed presence of oil would be, in a very short time, starkly contrasted with its manifesta-tion at the epicenter of development and conflict in the whole region.

An exploration team sent to Iran by a venture capital millionaire in London struck oil in 1908. Soon, the Anglo-Persian, later renamed Anglo-Iranian, Oil Company (APOC/AIOC, today known as BP, and in this essay simply ‘the Company’) was established. A rudimentary refinery was erected on Abadan’s muddy banks, which from 1913 was able to ship oil to a world market in explosive growth. Within a decade, oil from Iran catapulted the Company into extreme wealth and global power.

Locally, the establishment of the refinery became the first physical manifestation of the magic power of oil. Through oil, Abadan village gave way to a bustling city.

From an overlooked outpost, Abadan became a center of economy, a symbol of modernity and a hub of development. By the 1930s, oil had spawned a multi-cultural if segregated city with a progressive if unequal society. It had middle class suburbs alongside impoverished shanty-towns. It saw both ruthless suppression of labor activism and increasing social mobility. As a key entry point for new technology, fashion and con-sumerism, Abadan’s image was that of a liberal, leftist haven.

Labor strikes in 1929 and 1946 foreshadowed the 1951 oil nationalization movement. Abadan gave birth to famous artists, novelists and cine-matographers, many of whom would set the tone for the movement that culminated in the Shah’s overthrow in 1979. The chaos of the Islamic revolution was followed by Iraq’s 1980 invasion of Iran that led to a bloody eight-year war during which Abadan was evacuated and bombed.

Although it is today repopulated, Abadan has never regained its pre-revolutionary status and glory. Oil lost its magic powers, and Abadan’s progress was abruptly stopped. The city was more or less forgotten by those in power. But the

memory of old Abadan lived on.

The brevity and intensity of the city’s history is almost tangible in breathless prose of nostalgia such as this:

“I was reminded of what we called life, within the framework of certain principles and rules, and the culture of the city of Abadan that came to life where British discipline met with the peculiarities of the 72 nations [a metaphor for Iran’s multi-ethnic population], what we called Abadani soci-ety, where, far from all the backwardness of other cities, one could enjoy a tranquil breath of air, and I remember it as if it was a dream, a dream that moved with the speed of lightning throughout my life, and I realized that life in Abadan, with all its good facets, love, warm-bloodedness, hospitality, beauty, progress and principled order, just as in the life of civilized nations, whatever it was, was but a dream, and I was gripped by an urge to tell about all that I had heard and seen, touched, learnt and lost, from my birth until the day the Imposed War [a metaphor for the Iran-Iraq War] forced us away, an urge to tell this story under the heading Abadan was a dream.”

This is from the opening pages of Anglo va Bangolo dar Âbâdân (“Anglo and Bungalow in Abadan”, 2010), the first book by Iraj Valizadeh, born in 1938, who has worked in radio, theatre and in the refinery. It is one of several books

Fig. 3: Surveying future oil fields in Khuzestan, sometime in the 1910s.

Fig. 4: Arabs in Khuzestan, perhaps from 1951. Fig. 5: Abadan Refinery, probably in the 1930s.

written over the last three decades by Abadan enthusiasts, amateur historians and local lumi-naries.

Based on his own and his father’s memories, Valizadeh’s book resembles a chaotic stream of thought, absentminded but full of information. The narrative jumps from one topic and format on one page to another on the next: from per-sonal memories of growing up in the houses and streets of Abadan, to translations of articles from the Company’s English-language newsletter; from detailed rundowns of engineering accom-plishments in the refinery to recipes for local dishes; from minute descriptions of architecture to lists of records set by local sportsmen.

The whole narrative is tied together with that of oil, which is also reflected on the cover of the book: behind the title looms the refinery tow-ers, and under it, pictures of the gentlemen who established the oil industry and thus modern Abadan, which is represented by a neat bun-galow. In the upper left corner, it simply says “identity”.

The cover, like the content, draws a direct con-nection between oil, the foreign capitalist forces that extracted it, and the material progress it would manifest in local community. Valizadeh romanticizes the past while questioning its real-ity, asking himself whether Abadan was in fact just a dream. Or was Abadan like a dream?

The dream is kept alive today by many Abadanis who seek to catch it in pictures, objects and stories — whether they are too young to pos-

sibly remember or old enough to put it in writ-ing. As fleeting as it was, as transient as it is, the dream is ever lucid in Abadani nostalgia — and it is almost tangible to any visitor to the city, as I discovered.

The cult of nostalgiaOn my own first visit to Abadan, a member of a friend’s family —a former captain on an oil tanker— spent a whole day showing me around in the city’s various neighborhoods, the museum and the bazaar.

He reminisced over the places and the the peo-ple who used to frequent them before the war, before the revolution and before nationalization: the Greek photographer’s fancy studio where people would have their wedding pictures taken; the Jewish-owned shop at the roundabout that sold magazines from abroad; the hotel lobby where oil engineers from every corner of the world would gather to tell tall tales over whiskey.

But the captain was also in a rush to get to a particular place: an unassuming little store in the bazaar that prints photos and sells CDs, DVDs and sunglasses. Here, the captain had pre-ordered a gift for me: a heavy faux-leather bound album stuffed with grainy reprints of photos from old Abadan. The seller collects the photos on the internet, and sells them the same way as when someone orders up a private family album.

In the album, there are pictures of swimming pools, family dinners and picnics in parks, of rowing contests, flower exhibitions and scenes of children being vaccinated by smiling nurses. Most women are without hijab, wearing flowery dresses and hair-dos in the fashion of Audrey Hepburn or Sophia Loren. They smile at the camera. On black-and-white photos, gentlemen with mustachios wear suits, hats and ties. And in color photos, they don trumpet trousers, button-down shirts with broad collars and 70s haircuts.

The streets are not trafficked, the cars are American. Parks, gardens and hedges are neatly groomed. From some angles, Abadan looks like a pretty sleepy suburb in post-war Florida, the idyllic scenery only complicated by the refinery smoking in the background.

Fig. 6: Abadan streets, 1950s or 60s.

Fig. 7: Iranian pop diva Googoosh giving a show in Abadan.

Fig. 8: Abadani basketball girls.

Memories of the past tend to take on an almost cultic status in Abadan today. They are embodied in symbols, narratives, texts and objects that are collected, preserved and reproduced by ordinary Abadanis to connect the present with the past.

Some Abadanis are keen hoarders of pictures, Company newsletters, personnel documents, uniforms, posters, medals of distinction, even rationing coupons, cinema tickets and bus time-tables. At any given dinner in Abadan, the host may pull out boxes of memorabilia or anecdotes from a long life spent in the city. Even younger Abadanis show great interest in old Abadan.

During the war with Iraq, Abadanis were scat-tered to the four winds. There are Abadanis living across Iran and all over the world, and yet they tend to coalesce in Abadani circles wher-ever they are – including on social media.On Facebook, groups like ‘Children of the Oil Industry’ share pictures and stories sent in by Abadanis from near and far. Offline, Abadanis gather in clubs and networks, be it in Los An-geles, London or Tehran. There is also a society for former Company employees in the West, The Abadan Society. In its newsletter, members share memories, jokes and pictures.

Browsing the album in the bazaar shop, I notice that a bunch of teenagers have gathered behind me to look at the album. They are excited, and they want one for themselves. Despite my host’s attempt to haggle, the price is non-negotiable: the business of nostalgia is flourishing.

Abadan’s past is an exotic place. But as I reach the final pages of the photo album, the pictures begin to tell a gloomier story. Depressing scener-ies show Abadan as a bullet-riddled ghost town, kids playing on the burnt-out carcass of a war tank, mourning and grief painted in the faces of soldiers under the blood-red banners of mar-tyrdom. Engulfed by war, Abadan would never become the same again.

In an exceptionally short time, Abadan expe-rienced a series of dramatic leaps and abrupt interruptions in its trajectory. It is upon this discontinuity that nostalgia builds: a seed was planted by pioneers and with the speed of light-ning, it brought about an oasis of progress, fol-lowed by a steep blossoming, and then a sudden destruction that left only a fata morgana.

When Abadan was the coolest city in Iran: left, jazz legend Dizzy Gillespie poses with the Shah’s sister at a concert in 1956 (fig. 9); right, a kid poses with a fancy car (fig. 10).

PART TWO:WHEN ABADAN WAS

CAPITAL OF THE WORLDAbadan is special. Or at least, it used to be special. Its urban and social fabric stands out from all other Iranians cities. Its inhabitants are unmistakably Abadani. How is that? If oil can create a city, can it also shape an identity?

Abadan’s past status as an international city is central to stories of what it means to be an Abadani. Despite the injustice and inequality of the past, and despite Abadan’s rapid decline during the 1980-1988 Iran-Iraq War, Abadanis are still proud of their city and their history. That history is so deeply mired in the story of oil that it is impossible to tell the one without the other.

With the phenomenal growth of the oil industry across Khuzestan Province from the 1910s, the Company realized that a whole new city was needed in Abadan. Next to the absence of infra-structure, the biggest concern facing the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (later renamed Anglo-Iranian and today BP) was the supposed lack of skills and ‘discipline’ in the local population.

Although locals were hired for basic manual tasks, the Company preferred to import labor from India, Mesopotamia, Palestine, Burma and even China. Eventually and reluctantly, the Company would employ Iranians. Soon, migrants from all over Iran descended on Abadan in search of work.

Different styles and fashions, from the 1950s (left, fig. 11) to the 1970s (right, f. 12).

The British and their white Western colleagues stood at the top of the labor hierarchy that emerged. For the technical, administrative and menial work, they mostly employed those they deemed trustworthy: the Indians, Christian Arme-nians and Assyrians, and Jews. Muslim Iranians were employed in the lowest rung of the hierarchy, toiling in danger and living in misery.

Since many Company officers had a background in British India, they brought with them colonialist, racist ideas about managing a multi-ethnic, over-crowded society — ideas that materialized in urban planning.

In the Braim neighborhood, on one end of Abadan Island, where breezes made tropical life bearable, the British nurtured their culture in bungalows, cricket clubs, gardens, and at tea parties. Here, they were segregated, until oil nationalization, from the non-white population by the refinery, which func-tioned as a huge, metallic barrier on the middle of the island.

On the other end of the island was ‘The Native Town’: sprawling slums with crime, diseases and disorder, real and imagined, which the British feared could spill over at any time.

Relations were tense between immigrants and the local Arab-Iranians who were watching as their palm groves gave way to an industrial city. But the industry also generated new dynamics of conten-tion. As early as 1918, Indian migrant workers protested their maltreatment by the Company, and when they went on strike to demand higher wages, they signaled the birth of an oil labor movement in Iran. The British responded with heavy-handed repression, control and surveillance.

To offset rising discontent, the Company imported pre-fabricated barracks to house laborers. From the mid-1920s, it began to install sewerage and elec-tricity while extending roads, public transport and health services. In time, the Company built schools, social clubs, cinemas and a university, and in the 1940s, it established whole new neighborhoods in Bawarda and Bahmanshir.

In exchange for taking responsibility for urban development, the Company allowed itself to run Khuzestan as a de facto state within the Iranian state, and with Abadan as its capital.

Class difference and racial segregation: above, “White”, upper class Abadan (figs. 13 and 14);

below, “Native”, working class Abadan (figs. 15 and 16).

This imagined link with Brazil shows how the city sees itself in a global rather than merely Iranian con-text. And the international past lingers on in everyday life.

There are numerous English words in Abadani dia-lect, as well as loanwords from Hindi and Punjabi. Streets that were renamed with Islamic and Iranian names after the revolution are still called lanes – in-cluding Sikh Lane (actually, Sikh Line), once inhabited by Indians.

One of Abadan’s more intriguing buildings is the Masjed-e Ranguni-hâ (‘The Burmese Mosque’), built with inspiration from Indian temple architecture but undergirded by discarded oil pipes. The Anglo-Indian past is also reflected in the food culture, which dif-fers from Persian cuisine with spicy curries, chapatti bread, pakora snacks and chutneys.

The connection to Britain, although formally broken with the oil nationalization in 1951, is still tangible.In the local vernacular, Abadan was dubbed ‘Sec-ond London’ (landan-e sâni), and one of its famous squares (Alfi) was known as ‘Piccadilly Circus.’

I am told again and again that there used to be direct daily flights to England; that London Times was deliv-ered every morning as it hit the streets of the me-tropolis; that films premiered in Abadan simultane-ously with British cinemas; that many buildings were constructed with the “London red brick”; and that the local university cooperated with Birmingham.

Abadan’s population grew from 40,000 in the early 1920s to 200,000 in the 1940s. From the 1930s, some Iranians were able to move into the new middle class. Oil had brought about modern welfare and material progress unheard of in Iran at that stage. But it had also brought into being a segregated class society, modelled on the colonial-capitalist logic of a British corporation.

On such a background, it would be no surprise if Abadanis consider the British past a dark chapter of the city’s history. And yet, the pre-nationalization past is often invoked with a sense of loss.

Gained and lost in transitionVisitors to Abadan are constantly reminded that the city was once the capital of modernity in Iran: a cosmopolitan beacon for the Middle East and a prominent point on the world map. It is on this global scale that Abadanis tend to quantify the city’s past splendor and contrast it with its present sorry state.

Abadanis are proud, and sometimes the pride turns into ironic exaggeration or lâf– the stuff of many jokes in Iran, but also a self-conscious form of expression in Abadani popular culture. Let me give an example:

An Abadani who, just as all of his fellow citizens, it seems, is a huge fan of football was not really in-terested in my questions about the social structure of Abadan in the past. He was rather interested in why my country’s football team had never visited his city to play the local outfit, San’at-e Naft (‘The Oil Industry’). He resorted to lâf: “Before the Danes could even set foot in Abadan, we would have beaten them 3-0! The only team who would stand a chance against us is Brazil!”

Curiously, Abadanis tend to associate their city with Brazil.

A local researcher I met during my first visit pro-poses that the similarities in the tropical climate, the palm trees and the warm-blooded mentality may have caused this association. It may also be the simple fact that the colors of FC San’at-e Naft are the same as that of the Brazilian team, or that Abadanis allegedly play “samba style” football. A popular say-ing is Âbâdân berâzilete!, or ‘Abadan is your Brazil!’

Fig. 17: Abadani football fans.

Fig. 18: The Burmese Mosque.

Alfi Square, or “Picadilly Circus”, before and after the Iran-Iraq War. (figs. 19 and 20).

Most Indians, Jews and Christians have left the city, but they are nonetheless eagerly remi-nisced by Abadanis. There are only two Indian restaurants left in Abadan, but they remain the most popular. The airport seems dilapidated and distinctly provincial. They day I visit the old university, it is completely deserted. There is no London Times to be found in the kiosks. And yet Abadan insists on its global identity.

Through pipelines, shipping lines and airlines, oil connected Abadan to the rest of the world spatially; temporally, it synchronized the city with the modern West.

Today, when most have forgotten Abadan, and the city has slipped into the periphery, its past connection to the world is still a source of local pride.

From cosmopolitanism to provincialismA local researcher compares Abadani identity with the ma’jun smoothie, a blend of banana, honey, coconut, pistachio and dates.

Abadanis, he says, are the mixed product of the city: “I lived in an alley, where there was a Christian Lebanese Arab, an Indian family, a fam-ily from Bushehr, one from Tabriz and one from Dezful. We lived side by side without any prob-lems,” he says.

Rather than segregation and discrimination, Abadanis remember a strong sense of neighborly friendship, solidarity and harmony. “There was a church next to the mosque in our neighborhood,” another Abadani tells me.

When migrant workers came to Abadan from all over Iran, they tended to flock together in specific neighborhoods and mosques. There were Dashtestanis, Larestanis and Afro-Iranians from the south, Lors and Bakhtiyaris from the north, Behbahanis from the east; Armenian and Assyrian Christians, Jews, Bahais and Sabaeans; there were people from Shiraz and Esfahan, and those from further afield, Tehran, Tabriz, Bandar Abbas and Mashhad.

Yet the Company’s urban planning and mode of production brought people together in ways that

differed from traditional life and generated new forms of socialization. Many migrants broke with old tribal bonds in their home regions when they moved to Abadan, and many married outside their ethnic group after they settled there.

Together, these diverse peoples would craft a new culture that in many ways distilled and summed up all of Iran’s diversity in one city. Within the spaces created by oil, Abadan gave rise to a new communal identity.

After the nationalization of oil, Abadan entered a new golden age from the mid-1950s. In this period, Abadan became the symbol of American-inspired materialism and consumerism, with the nuclear family and suburban life as the ideal. Many luxury items, foreign cars, washing ma-chines and modern air-condition was imported for the first time into Iran via Abadan. Iranians and Westerners would mingle more freely, and a new middle class emerged.

The Company’s PR department disseminated the values that fitted the Shah’s vision of a secular, Westernized Iranian society. This new society was attainable, Iranians were told, through the miracle of oil. And the Company - now in Ira-nian hands - and the oil wells, the pipelines, the refinery and the laborers were the catalysts of the miracle.

With the new society came an obsession with looks and image. Abadanis were famous for their sense of fashion and for the distinct Abadani look. The most important item was sunglasses, a trade mark of Abadan — to such an extent that there is a whole genre of jokes in Iran related to the Abadani love of Ray-Bans. But also Western clothing, Clarks’ shoes and beach sandals, Ameri-can jeans and British shirts defined Abadani chic.

“When we traveled up to Mashhad,” a banker tells me, “our friends would ask us to bring clothes.” An Abadani would spend much time and energy on grooming, and was a heavy user of perfumes and beauty products. The contrast between the traditional look and that of a refin-ery worker out for a Thursday evening stroll was sharp.

The nostalgic books praise Abadan’s many spaces for pastime recreation: the scout teams, sowing clubs and courses on hygiene and cooking; golf, wrestling and horse rac-ing; swimming competitions, roller skating and backgammon on the cafés; not just Iran’s first cinemas but even 15 of them on the eve of the revolution; and of course the kind of after-work pursuits to which books published today can only allude through hints: the bars, cabarets and night clubs, opium dens, liquor stores and brothels.

Despite its history of social control, old Abadan is remembered today as a free-spirited, liberal and even hedonistic city. Many Iranians looked up to Abadan: they aspired to be employed by the Company, and the city was a popular destination for domestic tourism — “even though we don’t have any particular attractions,” the banker tells me.

Abadan’s attraction was its population; its pull on Iranians came from the ideas about the city that the magic powers of oil would conjure.

Today, Iranians still describe Abadanis as laidback, humorous, open and passionate people. The urban youth still appear less re-strained and conformist than their counter-parts in neighboring cities. And yet, many today complain that the disruptions of the war have prompted a growing conserva-tism. Instead of the cultural and political diversity that characterized the city before, tribalism and traditionalism have resurged. According to a local politician I interviewed, this has made Abadan a more provincial city. It has lost its cosmopolitanism.

It is as if the oil industry’s stagnation is seen as a root cause for cultural recession. The nostalgia pays homage to a time, when Abadan was bustling with culture and life, the envy of all Iran: an erstwhile trendset-ter gone out of fashion.

Abadan of fashion and consumerism (figs. 21, 22 and 23).

An orderly time in spaceWhat has been lost since the revolution and the war, many Abadanis say, is the order that characterized the city in the past: the discipline prompted by the oil industry and institutional-ized in the society that the British created under the Company, and which continued under the Shah — but has since disappeared.

Abadan was an orderly city, and it is now out of order, the visitor is often told; not just because of the war, but due to the mismanagement of the city by both political elites and ordinary citizens.

My interviewees complain that people cannot or will not respect the rules, that they show no respect for public space and that the city has lost its aesthetic identity. Citizens disregard regulations for how the houses once built by the Company are to be maintained, how gardens should be kept, facades cleaned and cars parked, and so on.

“The city has lost its historic face, and the mayor will not do anything — it is simply too difficult to change the mentality,” the local politician tells me.

Many memories and memoirs mention how the giant horns (feydus) of the refinery would signal the beginning and end of the work day. This cre-ated a sense of discipline that regulated urban life, and that my interviewees complain is miss-ing today. The post services, pay checks, electric-ity and above all traffic is in shambles.

“Back then, traffic would run smoothly, and you wouldn’t see garbage lying around in the streets,” an Abadani tells me — without specify-ing when ‘then’ was. “We had the best sewerage in the country,” a banker states. “Today, waste is seeping into buildings. The parks are unkempt, there are weeds growing everywhere and graf-fiti on the walls,” he sighs. Today, more than 25 years after the war, there are still bullet holes in some buildings.

The loss of “order” is a recurrent theme in the nostalgic books, including Iraj Valizadeh’s Anglo and Bungalow in Abadan. Valizadeh contrasts the present state of the city with the order of the past through detailed descriptions of Company welfare projects.

He painstakingly describes how the British introduced schemes to alleviate hungerdur-ing World War II. First, they would survey land outside the city in yards and feet; then subject the soil to desalination; and then allot it to local farmers under strict regulations for fertilizing and cultivating it. Then the Company conducted a census, divided Abadan into units of families, and allocated rationing coupons with which they could buy food stuff in new stores. In order to keep the calm during shopping hours, the British told Iranians to sit on the ground as they waited for their turn.

And thus, Valizadeh implies, Abadanis learned not only to respect the queue, but also to work together on solving collective problems in soci-ety, to use technology to cultivate the barren soil, and to distribute the yield through systematic

measures. All of this was possible thanks to the social and industrial discipline brought about by oil.

Valizadeh is certainly not blind to the jarring inequality of British-run Abadan. And yet he shows a strong belief in the spirit that British entrepreneurship purportedly engendered in Abadan.

I often encounter such arguments in conversa-tions with Abadanis: that everything was bet-ter during the British or before the revolution. Current local officials and managers are accused of inefficiency and cronyism. Abadan’s municipal authorities are paralyzed by internal conflicts and strapped for funding. A politician allegedly ran for local elections recently with the slogan “we don’t want progress – we want to return to twenty years before the revolution!” – a slogan that obviously runs counter to the official state narrative.

The waning magic of oil has left Abadani society to its own devices, and in the nostalgia for an orderly time with orderly spaces, Abadan hangs uneasily suspended in its own history.

Crude cultureWhen the Company established a system of technical and industrial routines that could be managed to meet one clear overriding objective —oil production— it also set in motion a chain of social processes that it could not control.

Oil was the driving force of economic and urban development in Abadan, but it also became the lubricant for cultural development, shaping new forms of socialization and creating new imagi-naries. Oil opened up new horizons and made Abadanis think of themselves and their city in a global context.

With the self-irony of lâf, Abadanis distance themselves from the exaggerated pride in a glo-rified past of order, style and status. But at the same time, a distinct Abadani identity persists wherever Abadanis have settled in the world. Perhaps we could visualize this identity, as the local researcher does, as a form of ma’jun.

But another metaphor is oil. Just as crude under-goes processing and refining before it is shipped out as oil to become another thing another place, Abadani-ness, an unintended byproduct of the oil city’s development, became a culture and an imaginary in its own right. Abadan is special.

Different types of housing built by the oil company (clockwise, figs. 26, 27 and 28).Flooding, and the generally poor state of some of the city’s public spaces today (figs. 24 and 25).

PART THREE:UNFULFILLED PROMISES

OF OIL MODERNITY AND REVOLUTION

I want to cryin mourning the death of the harbor

My devastated harborburial of fluttering flowers

Oh Abadan, how it disappearedunder blood and fire and smoke

My devastated harborthere used to be life in you

– ‘Abadan’, poem by Ardalan Sarfaraz. As comforting as it may feel, nostalgia is con-tentious: any remembrance of the past rests on selective amnesia.

In a country where the state persistently asserts itself as the manifestation of the people’s will through revolution, longing for the pre-revolu-tion past can be seen as a protest. Indeed, local accounts of Abadan can be at odds with official history in the Islamic Republic. But they are also often in conflict with each other. These conflict-ing views on the past grow out of common soil. They are rooted in the contradictory experience of modernity that oil brought to Abadan. That experience includes war.

In 1913, the British navy - under Winston Churchill, also a Company lobbyist - shifted from coal to oil, which propelled Britain towards vic-tory in World War I. As Abadan became a vital asset for the Empire, the Company acted as a military entity, controlling and coercing labor through policing and intelligence. In times of un-rest, the Company employed local tribes against workers or threatened with British intervention.

Yet Abadan’s oil workers quickly learned to pres-sure the Company by paralyzing that crucial part of the production cycle, the refinery. The 1929 oil refinery strike inspired a budding national-ist movement against foreign dominance across Iran. The demand for nationalization was public-ly expressed for the first time. Oil had thus given birth to a new form of political agency, to class awareness and to anti-imperialist sentiments that would impact profoundly on Iran’s history.

Faced with a growing labor movement in Abadan and a bolder Shah in Tehran, the Compa-ny had to make concessions. But higher wages, increased social mobility and more welfare was not enough to mask the basic unfairness of the Company earning huge profits from Iranian re-sources without even paying taxes to Iran. Terms such as junior and senior employee were mere euphemisms for the structural discrimination that shaped the work, community and daily life of oil workers.

On the pretext of the Second World War, amidst hunger, chaos and British occupation of south-ern Iran, the Company managed to strengthen its hold on Abadan. But already in 1946, the labor movement rose again during a major strike. With the support of thousands of disgruntled work-ers, the Communist Tudeh Party took control over Abadan and the refinery. The British played disgruntled Arab tribes off against the strikers, and then forced the Iranian police to crack down on Communists.

And yet, it was too late. In 1951, the democratic Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddeq, riding a wave of anti-imperialist sentiment, finally nationalized Iran’s oil. During the dramatic ‘Abadan Crisis,’ British employees were evacu-ated while oil workers hoisted the Iranian flag

Fig. 29: Winston Churchill preparing for war. Fig. 31: British oilmen and their families leaving Abadan during the 1951 Abadan Crisis.

Fig. 30: British Indian riflemen at Abadan Refinery.

on the refinery.

Oil was now a symbol of independence and popular will. But in just two years, Mosaddeq was overthrown in a CIA-organized coup, which paved the way for an emboldened, more auto-cratic Shah. While Iran now owned its oil, the country became dependent on US support. Ris-ing oil revenues were spent to finance the Shah’s overambitious plans and megalomania.

A turning point was an event in Abadan: on 19th August 1978, unknown perpetrators set fire to the fully packed Cinema Rex. At least 500 died in this, one of the biggest acts of terrorism before 9/11. In the months after the fire, the movement against the Shah was radicalized, culminating in the revolution and the establishment of the Islamic Republic. The last foreigners left Abadan and the revolutionary state purged Iran of West-ern cultural imperialism and moral decadence.

Just as Khomeini had consolidated his power, Iran was attacked in 1980: the Iraqi invasion was partly prompted by Saddam Hussein’s ambition of annexing Iran’s oil-rich region around Abadan. In some of the worst battles of the eight-year war, locals and volunteer soldiers gave the Iraqi invaders stiff resistance.

Abadan’s neighboring city of Khorramshahr was the scene of a brutal siege and a 1982 libera-

tion considered an epic in Iran today. Thousands died during the battles for Khorramshahr and Abadan, among them some of Iran’s most celebrated martyrs. Abadan was bombed and besieged for 18 months, and almost all inhabit-ants were evacuated and displaced.

Near the end of 1980s, Abadan was gradually resettled, although many never returned. In 1989, the refinery resumed operations, but only in 1997 could it reach its pre-war output. By that time, its place in the Iranian oil grid had been taken over by newer installations elsewhere. Attempts to revive the local economy have only been partly successful. The plans for a major free trade zone around Abadan and Khorramshahr appears in shambles, and Abadan is plagued by a host of socioeconomic problems.

As a juggernaut of modernity, oil heralded rapid development, profound change and a prospect of emancipation. It inspired movements, brought them to their knees and saw them rise again. Through oil, Iranians imagined a new era, liber-ated from imperialism and as masters in their own house. But ousting the British only gave way to the tyranny of the Shah, and freedom from the Shah was followed by the horror of war.

Although oil made many futures seem attain-able, it never gave Abadan peace. Those living in Abadan today are still suffering from the conse-

quences of war.

Oil, water and corroded promisesA key Abadani grievance is that the city has lost its vibrant, healthy and productive environment.

Almost a third of Abadan’s population subsists on financial support from the government, and Khuzestan officially has 27% unemployment. The local youth, I am told repeatedly during my visits to Abadan, is marked by disillusion, and some have slipped into drug abuse.

“The young don’t do sports anymore. We used to have the best sportsmen in the country, but now the riff-raff hangs around in the streets all night doing drugs,” I was told by an elderly Abadani gentleman working in a local bank. There are no statistics available, but an official tells me that Abadan is suffering from a “drug epidemic.”

The social environment seems to suffer in tan-dem with the physical environment.

In all of Khuzestan Province, water is of an alarmingly bad quality, particularly so around Abadan. The region is deeply affected by air pol-lution from metal, sugarcane and petrochemical industries. The provincial capital Ahwaz, 130 km. north of Abadan, has the dubious honor of being the most polluted of all cities in the world.

Khuzestanis suffer from illnesses caused by the pollution, and drought, salinization, erosion, acid rain and mismanagement have destroyed much agriculture and nature. As rivers have been dammed and marshes drained in Iran, Iraq and Turkey, the region has become a huge dustbowl. Abadan is regularly smothered in sandstorms.

Popular notions of wellbeing and prosperity in Abadan are tied directly to water, and access to water, the quality of water and the symbolic power of water in a desert community are also key themes in the nostalgic books. The books often contain odes to the rivers that flow around Abadan, or pay homage to the drinking water systems, water purification plants and swim-ming pools constructed by the Company.

Not all of the books praise the charitable work of the Company, though.

The retired school teacher and now Karaj-based writer Ali Farrokhmehr has written eight books about his life in Abadan. In his Âbâdân: Khâk-e khubân, yâd-e yârân (‘Abadan: Soil of the Good, Memory of Friends’), we are told how in the late 1940s, the Company dug a canal from the Bahmanshir River into one of the new quarters, supplying water to gardens and a large public swimming pool. Farrokhmehr remembers play-ing in the pool as a child.

Fig. 32: Children in Abadan during the war. Fig. 33: Female volunteer militia during the war. Fig. 34: Dust engulfing Abadan.

But he also distances himself from the specta-cle, which was in fact a PR strategy to cover up inequality:

“All the Company neighborhoods had clean drink-ing water, electricity and asphalted streets but the rest of the city was barred from the bare necessi-ties of life! Abadan was inextricably tied together with contradictions. Next to the biggest refinery in the world, misery thrived. A lump of ice was something you could only dream of! In the shade of the refinery, the only recreation for Lors, Kurds, Arabs, Baluchis and Persians was a pool and the Bahmanshir Cinema under open sky! The sum of all these contradictions made Abadan a city on the brink of explosion!”

Farrokhmehr grew up in the shantytown, and has no rosy picture to paint of Abadan under the British or under the Shah. The aspect of Abadan’s past that he deems memorable is a cul-ture, which may have taken shape in the spaces created by the Company, but was unmistakably Iranian, patriotic and religious: the Iranians who as booksellers, teachers, poets, sportsmen and engineers created Abadan.

Farrokhmehr’s Abadan is a city of the oppressed, devout, revolutionary and the martyrs: the stage for an epic struggle against the Western powers that sought to hamper Iran’s industrial and spir-itual development. When Iranians succeeded in wrestling oil out of foreign hands, the imperial-ists took revenge by destroying the country with the help of their henchman, Saddam Hussein.

Farrokhmehr denies that his longing glorifies the past:

“Why, with all these disappointments and all this pain do hearts still wheel and circle over the past? In every corner of Iran, the ageing and elderly bring the days of yore to life with a sigh. A sigh, not of resentment for the present, but because days are passing fleetingly, and life is short … Yes, it was indeed oil that turned ‘Abbâdân [the old Arabic name of the city, ed.] into Âbâdân [the pre-sent name, which connotes ‘progress’ and ‘blos-soming’, ed.]. Yes, it was indeed the establishment of the refinery that made Abadan a city! The oil, the refinery, ArvandRud River, Bahmanshir River,

the money, the harbor, the export and the import — they turned the island into a thriving port. In time, slowly, like a turtle. But with all those riches, it could also have blossomed more than it did!”

Farrokhmehr, then, is not nostalgic for the splen-dor of the past, but rather for the missed futures of the past: the city did not become what oil could have made it become.

In another book, Âbâdân, kuche-ye mehrabâni (‘Abadan, Street of Love’), his subtle critique of the post-revolution state surfaces:

“The long war, life as displaced and in exile, promises and assurances, neither war nor peace; and slowly, Abadan lost its value and dignity, and the population turned disillusioned and their hearts grew cold. The artificial lake and the swim-ming pool were forgotten. The water pipes in the ground corroded. The gardens faded and Tank One and Tank Two [neighborhoods in Abadan, ed.] became worse than shantytowns! … This is not just the story of water and drought. It is the story of a city being phased out.”

Part of Farrokhmehr’s story, then, is the frus-tration with unfulfilled promises of post-war reconstruction and the indifference of those in power. This echoes those in Iran’s lower classes who had hoped that the revolution would bring social justice and progress for all. It also echoes a frustration felt across Khuzestan, where infra-structure and homes are still marked by a war that ended 27 years ago.

But it is not just a story about frustration with the state. Abadani nostalgia exposes the para-dox of the modern: the disillusion of life in a city that is surrounded by rivers but does not even have clean drinking water; the disappointment of living so close to a resource that promised to transform life, and then, after liberation, the experience of being crushed by the war machine of covetous foreign powers.

As a symbol of injustice and unfulfilled prom-ises, oil is present throughout the story of a city phased out.

Figs. 35 and 36: Ordinary Iranians in 1950s Abadan.

Last scene: the amnesia of liberationCinemas stand out in the geography of memory sketched in the nostalgic books. They symbolize the windows to the world that oil opened up in Abadan.

Cinema has its own story that began in 1912 when the first portable projector was im-ported to entertain British employees exclu-sively. Soon, the Company realized the many benefits of films and opened cinemas, open air or in disused warehouses, and eventu-ally new, grand cinema complexes. Here, the Company would screen propaganda news from England along with commercials for the Company or for products available in Company stores.

The Company even produced a film about Abadan, Persian Story. It was meant to con-vince an European audience of the magical power of oil, of the charity of the Company and of Abadan as a prime example of mod-ern progress in even the most backward setting.

From the 1930s, privately owned cinemas were also established, including some of the biggest and technically most advanced in the Middle East. They showed Western movies, and in the nostalgic books, Abadanis re-member watching Tarzan, Hopalong Cassidy and East of Eden. Sometimes, they screened Indian Bollywood dramas or romantic mov-ies from Egypt. Thanks to Abadan’s relative independence from Tehran’s censorship, Ira-nian films with social and political messages could be shown uncut. But gangster flicks and sordid comedies were always popular.

The cinemas drew people from all over the region to Abadan: Arab tribesmen came rid-ing or sailing in just to watch Abdel Halim Hafez, the Dark-Skinned Nightingale from Cairo sing of his broken heart, or to watch Charlton Heston race for his life in Ben Hur.A trip to the cinema could be a family pic-nic or a chance to steal a kiss. Cinemagoers

would sing, cry and shout, and if the screen-ing was interrupted by power cuts, riots could erupt. Abadan was obsessed with films.

The many cinemas inspired some of Iran’s best directors, including Nasser Taghva’i and Nader Amiri. Cinemas were a physical land-mark: one of the most popular postcards from old Abadan shows the magnificent Taj Cinema, built with imported redbrick.

But the remembrance of Abadan of the Cinemas also carries within it a need to forget: for many Abadanis, the last scene in the story of Abadan’s glory took place in the cinema.

That fateful, sweltering hot night of August 19, 1978, when more than 500 Abadanis perished in a blaze, the film Gavazn-hâ (‘The Deer’) had drawn a sold-out show to Cinema Rex.

Today, it still appears significant that it was exactly this film that was showing. Gavazn-hâ, a modern classic by Mas’ud Kimai, tells the story of Qodrat, a bank robber on the run who takes refuge with his childhood friend, the junkie Seyyed, and his girlfriend who works in Tehran’s sleazy cabarets. With the help of Qodrat, Seyyed manages to quit his addiction, defend the honor of his girlfriend and resist his rivals. With its ruthless depic-tion of the downside of modernity, the film only barely slipped through censorship. It was received as a critique of Iranian society under the Shah.

It is also with this understanding that the Islamic Republic makes sense of the fire: that the Shah wanted to scare people away from the simmering rebellion, to punish those watching critical movies, or to throw the blame on Islamic radicals when in fact it was the Shah’s own people who were be-hind. Another interpretation is that Islamists started the fire: blaming the Shah while tar-

geting a cinema, which for some represented the epitome of sin, moral decay and Western decadence.

No matter what, the nostalgia for Abadan of the Cinemas is contrasted by the painful experience of modernity that went up into flames in the oil city: first in the Cinema Rex fire, and then, two years later, in the Iran-Iraq War. The final act in the combustible story of Abadan’s glory starts with a fire and ends with a war.

As opposed to the official narrative that treats the patriotic fight against Iraq as the starting point of a new golden era in Iran’s history, Abadan’s nostalgic books end with the war. This is obviously connected to the evacuation: memories and memoirs end with a tragic afterword of displacement, life in refugee camps, moving to other cit-ies or leaving Iran altogether. The war reset Abadan’s historic clock. It is as if those who are still in Abadan and writing about the city’s past are living in the fading setting of what used to be a glorious film that did not end as promised.

Oil went from being a source of progress to the cause of enmity, destruction and disloca-tion; and now, the backdrop for stillness and inertia. And yet oil continues to feed nostal-gia, criticism and self-criticism, identity and pride.Fig. 37: Poster for the Company’s propaganda film

“Persian Story”

Fig. 38: The magnificent Behrouz Vosughi as Qodrat in a scene from Gavazn-hâ.

Fig. 39: Cinema Rex after the fire.

When there is a power cut“Our refinery used to be the biggest in the world, and it is still big. And yet we have power cuts! It simply doesn’t add up,” an in-terviewee tells me. And as a visitor, one does wonder how a city based on a refinery is not able to provide all citizens with a stable source of electricity.

Oil is a contradictory experience to those who live in its spaces of extraction and re-finement.

The possibilities of modernity were mani-fested physically right in the middle of what would quickly become a sprawling city: in its spectacular, giant metallic embodiment, the refinery heralded prosperity and wel-fare, progress and happiness. And yet, these promises remained unfulfilled as Abadan was ravaged and forgotten.

Oil constitutes the dichotomies through which Abadani nostalgia reenacts history: its presence created order and discipline, its ab-sence made society descend into chaos and disregard; oil endowed Abadan with pres-tige before it became a footnote in history; oil brought about cosmopolitanism, which has now been replaced by provincialism; oil gave healthcare, drinking water and agricul-ture, but also environmental degradation; oil generated electricity to lit up the streets of the world, but today cannot even secure Abadan itself; the magic power of oil fuelled imagination in spaces like the cinema, until those spaces burnt down, were bombed to pieces or simply closed and disappeared.

This discontinuity and suspension in time breaks with the teleological perception of modernity as the result of modernization following a clear and inevitable trajectory. The nostalgia hails the magic power of oil just as it is painfully aware of its tendency to destroy.

Abadanis have many reasons to reminisce about the past: to glorify it or to criticize it or to lament the ruptures that broke the city’s thrust into the future; or to forget about the ruptures and dream away to dif-ferent futures that could have been.

Nostalgia cannot be reduced to a critique of the Islamic Republic, conservatism and eco-nomic recession, although these are impor-tant points to some. What unites nostalgia are the expectations to and experiences with modernity that oil engendered.

When a power-cut hits Abadan, the only thing that fills the darkness with light are the flames of the refinery. This makes it clear to everyone how contradictory and ultimate-ly ephemeral modernity is.

SOURCES:Farrokhmehr, Ali. 2001. Âbâdân: Kuche-hâ-ye mehrabâni, Tehran: Nashr-e Abed.

Farrokhmehr, Ali. 2011. Âbâdân: Khâk-e khubân, yâd-e yârân, Tehran: Najaba.

Valizadeh, Iraj. 2010. Anglo va bangolo dar âbâdân, Tehran: SimiaHonar.

PICTURES:Fig. 1: National Iranian Oil Company, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Abadan#mediaviewer/File:Abadan_the_city_of_Oil.jpgFig. 2: Ahmad Kaabi.Fig. 3: BP Archives.Fig. 4: Unknown source.Fig. 5: BP Archives.Fig. 6: AIOC.Fig. 7: Abdolali Lahsaiezadeh.Fig. 8: Unknown source.Fig. 9: the Dizzy Gillespie Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.Fig. 10: Paul Schroeder.Fig. 11: Shahriar Tashnizi.Fig. 12: Unknown source.Fig. 13: Hamid Arjomand.Fig. 14: Inge Morath Collection.Fig. 15: J. H. Bamberg.Fig. 16: Unknown source.Fig. 17: Unknown source.Fig. 18: Asr-e Iran.Fig. 19: Abadan.wikimapia.org.Fig. 20: Unknown source.Fig. 21: Paul Schroeder.Fig. 22: Unknown source.Fig. 23: Unknown source.Fig. 24: Mehr News Agency.Fig. 25: Abadan News.Fig. 26: Unknown source.Fig. 27: Paul Schroeder.Fig. 28: Shahriar Tashnizi.Fig. 29: Rare Historical Photos.Fig. 30: Imperial War Museum.Fig. 31: J. H. Bamberg.Fig. 32: Fars News Agency.Fig. 33: Unknown source.Fig. 34: Mehr News Agency.Fig. 35: Paul Schroeder.Fig. 36: Paul Schroeder.

Fig. 37: BP Archives.Fig. 38: Still from Gavazn-ha by Mas’ud Kimiai.Fig. 39: Unknown source.

SUGGESTED READING:

On industrial urbanismAlissa, Reem. 2013. “The Oil Town of Ahmadi since 1946: From Colonial Town to Nostalgic City”. Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 2013: 33, pp. 41-58.

Dinius, Oliver J. & Vergara, Angela 2011. Com-pany Towns in the Americas: Landscape, Power and Working-Class Communities, University of Georgia Press.

Ferguson, James 1999: Expectations of Moderni-ty: Myths and Meanings of Urban Life on the Zam-bian Copperbelt, University of California Press.

Fuccaro, Nelida 2013: “Shaping the Urban Life of Oil in Bahrain: Consumerism, Leisure, and Public Communication in Manama and in the Oil Camps, 1932-1960s”, Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 2013: 33, pp. 59-74.

On Abadan and its historyBayat, Kaveh 2007: “With or Without Workers in Reza Shah’s Iran: Abadan, May 1929” in Touraj Atabaki (Ed.): The State and the Subaltern: Mod-ernization, Society and the State in Turkey and Iran, I.B. Tauris.

Crinson, Mark 1997: “Abadan: Planning and Architecture under the Anglo-Iranian Oil Compa-ny”, Planning Perspectives 1997:12, pp. 341-59.

Cronin, Stephanie 2010: “Popular Politics, the New State and the Birth of the Iranian Working Class: the 1929 Abadan Oil Refinery Strike”, Mid-dle Eastern Studies 2010: 46, pp. 699-732.

Ehsani, Kaveh 2003: “Social Engineering and the Contradictions of Modernization in Khuzestan’s Company Towns: A Look at Abadan and Masjed-Soleyman”, International Review of Social History 2003: 48, s. 361-399.

Ehsani, Kaveh 2014: The Social History of Labor in the Iranian Oil Industry, the Built Environ-

ment and the Making of the Industrial Working Class (1908-1941), doctoral dissertation, Leiden University.

Elling, Rasmus Christian 2015: “On Lines and Fences: Labour, Community and Violence in an Oil City” in Ulrike Freitag, Nelida Fuccaro et al (Eds.): Urban Violence in the Middle East: Chang-ing Cityscapes in the Transition from Empire to Nation State, Berghahn Books (forthcoming, March 2015).

Elling, Rasmus Christian 2015: “War of Clubs: Struggle for Space and the 1946 Oil Strike in Abadan” in Nelida Fuccaro (Ed.): Violence and the City in the Modern Middle East, Stanford Uni-versity Press (forthcoming, primo 2016).

Pirzad, Zoya 2013: Things We Left Unsaid, trans-lated by F. D. Lewis, Oneworld Publications.

On nostalgiaBoym, Svetlana 2007: “Nostalgia and Its Discon-tents”, Hedgehog Review 2007: 9, pp. 7-18.

Davis, Fred 1979: Yearning for Yesterday: A Soci-ology of Nostalgia, Free Press.

Gross, David 2000: Lost Time: On Remembering and Forgetting in Late Modern Culture, Univer-sity of Massachusetts Press.

On oilCoronil, Fernando 1997: The Magical State: Na-ture, Money, and Modernity in Venezuela, Chicago University Press.

Damluji, Mona 2013: “The Oil City in Focus: The Cinematic Spaces of Abadan in the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company’s Persian Story”, Comparative Stud-ies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 2013: 33, pp. 75-88.

Davis, Eric & Gavrielides, Nicolas 1991: State-craft in the Middle East: Oil, Historical Memory and Popular Culture, University Press of Florida.

Limbert, Mandana 2010: In the Time of Oil: Piety, Memory, and Social Life in an Omani Town, Stan-ford University Press.

Mitchell, Timothy 2011: Carbon Democracy: Political Power in the Age of Oil, Verso.

Salas, Miguel Tinker 2009: The Enduring Legacy: Oil, Culture and Society in Venezuela, Duke Uni-versity Press.

Vitalis, Robert 2007: America’s Kingdom: Myth-making and the Saudi Oil Frontier, Stanford University Press.

Watts, Michael 2001: “Petro-Violence: Com-munity, Extraction and the Political Ecology of a Mythic Commodity” in Nancy Lee Peluso & Mi-chael Watts (Eds.): Violent Environments, Cornell University Press, pp. 189-212.