What are corridors and what are the issues? Introduction to special issue: the governance of...

Transcript of What are corridors and what are the issues? Introduction to special issue: the governance of...

Journal of Transport Geography 11 (2003) 167–177

www.elsevier.com/locate/jtrangeo

What are corridors and what are the issues? Introductionto special issue: the governance of corridors

Hugo Priemus, Wil Zonneveld *

OTB Research Institute for Housing, Urban and Mobility Studies, Delft University of Technology, Thijsseweg 11, P.O. Box 5030,

2629 JA Delft, The Netherlands

Abstract

Linear concepts such as the corridor have a long history in spatial and urban planning. The recent megacorridor or eurocorridor

concept, proposed in the context of discussion on European territorial development, strives to integrate policies on infrastructure,

urbanisation and economic development. As is shown by the example of the Netherlands, the corridor concept can count on a

hostile reception from spatial planners. As an analytical concept the corridor can hardly be denied its legitimacy. Several urgent

policy issues can be attached to corridor developments that together require an improved coordination between policy domains at

different spatial levels.

� 2003 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Megacorridors; Eurocorridors; Spatial planning

1. The starting point: corridors as bundles of infrastruc-

ture

As a starting point, we can imagine corridors to be

bundles of infrastructure that link two or more urban

areas. These can be highways (sometimes via different

routes), rail links (high-speed trains, intercity lines, local

trains or trams), separate bus lanes, cycle paths, canals,

short-sea connections and air connections. In general,

however, corridor development concerns connectionsthat use different transport modes (e.g. car, train, tram,

ship, aeroplane), and carry both passenger and freight

transport. One can also adopt a broader interpretation

of corridors that encompasses things like ICT infra-

structure, power lines and cables as well as pipes for

drinking water, natural gas, crude oil, electricity and

sewage. This contribution, however, will concern itself

mainly with traffic infrastructure, that is, passenger andfreight transport links.

The development of corridors over the course of time

has reflected technological advances in transport modes,

and the construction legacy of different varieties of in-

* Corresponding author. Tel.: +31-15-2781038; fax: +31-15-

2784422.

E-mail address: [email protected] (W. Zonneveld).

0966-6923/$ - see front matter � 2003 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/S0966-6923(03)00028-0

frastructure. New generations of infrastructure are often

located in the vicinity of older systems and sometimes––in cases of replacement––on top of older systems. In

other words: the development of corridors is strongly

path dependent. This is the crux of Whebell�s theory of

corridors (Whebell, 1969). In most parts of the world,

cities were initially linked over land only by road.

Wagons, carts and coaches were drawn over these roads

by horses and other animals, and roadhouses, inns and

markets sprung up along the way. In areas rich in water,rivers and other water routes were important conduits

for sailboats, rowboats and barges.

Industrialisation brought with it the personal car and

the lorry, and finally also the highway. Curves were

straightened out, roads were paved and average speeds

soared. Although industrialisation also brought motor-

boats and steamboats, the increase in traffic over water

was much less dramatic than that on land. Road net-works became increasingly elaborate, while waterway

networks remained much more basic, being expanded

only in exceptional circumstances. Finally, the age of

industrialisation brought trains and trams, for which a

completely new rail-based infrastructure was laid out.

Initially, the hearts of existing cities were linked via

land-based routes according to the logic of shortest

distances. Later, however, railway stations were lo-cated outside city centres in order to avoid large-scale

168 H. Priemus, W. Zonneveld / Journal of Transport Geography 11 (2003) 167–177

demolition and to spare the surrounding area the dis-turbances caused by the noise and smoke of the trains.

The best example of this is probably London, where all

its stations are terminals. With the explosion in car

traffic, congestion and traffic safety levels in the built-up

area became increasingly intolerable. It was first at-

tempted to remedy this by clearing large thoroughfares

through old city neighbourhoods, but after the 1960s,

the solution was increasingly sought in ring roads cir-cumnavigating the city and––literally––holding traffic

off at a distance.

The consequence of this historical development is not

only that cities are currently situated at a node (or better:

nodes) of different kinds of infrastructure (the main theme

of the book �Splintering Urbanism� by Graham and

Marvin, 2001), but also that these infrastructure nodes

are laid out differently vis-�aa-vis the cities and each other;this fact has seriously compromised the interconnectiv-

ity and interoperationality of various traffic networks.

Understandably, airports generally lie at a fairly great

distance from city centres, or where this is not the case

(e.g. Athens), are moved further away. This situation

may please taxi drivers, but not most travellers. Only

recently, however, has there been a growing level of

attention for direct and seamless connections betweenairports and city centres via train, light rail or metro

(e.g. Tokyo, London––Heathrow, Amsterdam––Schi-

phol). Train and roadway networks are quite poorly

integrated. Here and there, Park & Ride facilities have

been developed at a number of railway stations and

well-situated transfer stations along the motorway, in

order to promote seamless multi-modal travel and fa-

cilitate transfers from one transport network to theother. In so doing, one encounters not only site location

and traffic-technical difficulties, but also institutional

problems such as the coordination of services and the

absence of a universal fare structure (e.g. a �smart card�system). These kinds of developments, combined with

the consequences of new generations of infrastructure

(path-dependency), have resulted in a situation that in

many parts of the world––particularly those character-ised by high population densities such as north-west

Europe––heavy bundles of infrastructure exist whose

location exerts a powerful influence on urbanisation

patterns and economic development.

2. The corridor as a planning concept

2.1. Planning urbanisation

The use of �corridor� as a planning concept is in fact

rather old. About a century ago, linear city models werepresented as alternatives for the densely populated,

concentric industrial city. The most famous of these was

put forth by the Spanish urbanist Soria y Mata (1844–

1920) in a series of articles published as early as 1882. Infact, he was the first urban planner to design an urban

model fully tailored to the development of transport

technology. Soria y Mata had strong misgivings about

the often-chaotic urban development in his day. To

combat this, he proposed that urban extensions be fully

adjusted to the infrastructure necessary for efficient

transport. The �Ciudad Lineal� takes the form of a city of

400 m wide, centred on a tramway and a parallel-run-ning thoroughfare. Although he advocated a new sort of

land policy to make the Ciudad Lineal possible from a

social point of view, his model was traditional since only

dwellings for the more affluent had immediate access to

the central axis. For the study of urban models, it is

important to remember that the Ciudad Lineal did not

represent a model of an alternative linear city, but was

created to extend existing ones (Hall, 1996, p. 112 ff.). Assuch, the model has been influential because many re-

gional plans made since then have advocated some sort

of linear extension of large cities based upon infra-

structure. The basic difference in most cases is that an

unbroken linear development was certainly not pro-

posed, but more the model of �beads on a string�: smaller

urban settlements grouped along an infrastructural line.

The famous Copenhagen Finger Plan of 1947 is a clearexample of this (Lemberg, 1997). Similar plans have

been developed for the cities of Oslo and Stockholm

(Fullerton and Knowles, 1991). The unplanned extension

of cities based on the road system, on the other hand,

has always been rejected by virtually all urban planners.

Using the words of Mumford (1937) this would ulti-

mately lead to the �Townless Highway�. Also many

conservationists up to the present day strongly rejectsuch a model. At an early stage of the profession, the

mere occupation of the countryside by urban functions

was opposed by planners. Later on––the last decades of

the twentieth century––the fragmentation of scenic areas

and the destruction of ecological infrastructure were

becoming the main grounds for objections. Neverthe-

less, history tells us that urbanisation in the shape of

linear and fragmented development has taken place on agrand scale. Studies of many towns seem to agree that

1850 represents a peak in urban densities (Hohenberg

and Hollen Lees, 1995, p. 303 ff.). After that, most Eu-

ropean cities spread out into the surrounding country-

side rapidly, sometimes in a carefully planned manner

and sometimes totally haphazardly. Technological in-

novations clearly made this possible, first with the ar-

rival of tram and railway lines and electricity, later onwith the internal combustion engine and the private car.

The trams and railways, although enabling urban de-

centralisation, also allowed for some regrouping in the

form of streetcar suburbs. However, the private car

made decentralisation in totally fragmented patterns

possible, although some sort of clustering is often still

discernable at a higher level of scale. The corridor

H. Priemus, W. Zonneveld / Journal of Transport Geography 11 (2003) 167–177 169

concept thus forms part of the ongoing debate on pat-terns of urbanisation and urban spatial structure.

2.2. Megacorridors and economic development

Only recently, at least in the European Union, the

corridor concept is turning into a multi-faceted concept.

The �project� Europe 1992, aiming at a �borderless� Eu-rope, played a pivotal role. The assumption was that the

abolition of the barriers posed by national borders

would result in a substantial rise in cross-border and

transnational relations, which could ultimately reshape

the spatial structure and thus the map of Europe in asignificant way. In hindsight, it is not surprising that the

modern version of the corridor concept––the megacor-

ridor––crept up in this period of time. More or less at

the same time as the unfolding of the Europe 1992

project, an infrastructure discourse at the European le-

vel took shape (Hajer, 2000). In regional policy there

was a firm belief that enhancing the level of connectivity

would stimulate the economic performance of regionslagging behind. This line of thinking was scaled up to

the level of Europe. Economic integration pushed for-

ward by the Europe 1992 project should thus be ac-

companied by a policy programme aimed at the physical

integration of the European territory. This was linked in

part to the expectation that certain areas and regions

would profit more from integration than others, and

that there will also be some clear �losers�. Geographicallocation has a lot to do with this, so it was assumed.

New cross-border and transnational infrastructure

would offset remoteness and peripherality and, in gen-

eral, make economic integration physically possible.

Assumptions and expectations like this have led to the

project of Transeuropean Networks, which is probably

(at least in financial terms) one of the most important

outcomes of the European infrastructure discourse.Transportation itself became the object of coopera-

tion within the European Union. The first reason for this

was that the passing of the deadline of the Europe 1992

project did not bring all the obstacles to trans-border

traffic to an end. A well-known example is the division of

European airspace into many sub-spaces, each com-

manded by its own air traffic control system. The Eu-

ropean rail system is plagued by similar institutionalfragmentation, resulting in a host of different technical

systems being used by national rail companies simulta-

neously. This problem has led to a distinct corridor

concept, not in the dictionary sense of the word (i.e. safe

passage through an otherwise hostile territory), but as

unhampered passage (freeway) through an institution-

ally and technically fragmented European territory. So

what we are dealing with here is in fact an institutionalcorridor, albeit limited to the transportation theme. All

these various strands of thinking and emerging policy

issues focussed on the idea of linkages were brought to-

gether under the umbrella of the (mega)corridor concept.In particular some of the transnational studies carried

out to produce the European Commission report �Eu-rope 2000+� (CEC, 1994) gave prominence to this con-

cept. Attention is especially directed to the concept of the

eurocorridor, a guiding concept in the study report on

the Central Capital City region (CEC, 1996), an area

encompassing Southeast England, northern France, the

Netherlands (except the northern provinces), Belgium,Luxembourg and parts of western Germany. In this re-

port, the eurocorridor is defined as a combination of one

or more important infrastructure axes (road, rail, tele-

communication lines) with heavy flows of cross-border

traffic that link important urban areas (ibid., 1996, p.

107). Literally speaking, the CCC-study makes a dis-

tinction between (euro)corridors and urban areas. Still,

the study is not conclusive on this point because it sees aclose connection between the level of competitiveness of

an urban area and whether this area is located in a cor-

ridor or not. The study speaks in terms of an emerging

group of cities with very high nodality (London, Paris,

Frankfurt, Brussels, Amsterdam, Cologne, Duisburg

and Lille). This is to the �disadvantage� of, for instance,cities in regions not linked to the network. For that

reason the CCC-study promotes the development ofseveral new eurocorridors and the improvement of me-

tropolitan cooperation and connectivity in existing eu-

rocorridors. So behind this �policy scenario� lies the

assumption that (new) infrastructure is of crucial im-

portance––maybe even decisive––when it comes to

competitiveness. The concept of a eurocorridor is

therefore intimately linked to the European cohesion

discourse. It does also however raise the issue of insti-tutional and administrative fragmentation in an area

where there are strong links between the constituent

parts. The CCC-area is a European macro-region char-

acterised by a very high density of borders. This is even

more the case because the internal borders of Belgium,

from a spatial planning point of view, can be considered

as national borders as well.

2.3. The eurocorridor approach

The European Spatial Development Perspective has

brought with it the discussion on �eurocorridors�––thepreferred term in the ESDP––to a new level by advo-

cating it as nothing less than a comprehensive planning

concept (CEC, 1999). In the ESDP the eurocorridor is

indeed considered as a bundle of infrastructure, but also

as a development corridor. ‘‘The spatial concept of eu-

rocorridors can establish connections between the sector

policies of, say, transport, infrastructure, economic de-

velopment, urbanisation and environment. The devel-opment perspective for eurocorridors, should clearly

indicate the areas where the growth of activities can be

clustered and the areas which are to be protected as

170 H. Priemus, W. Zonneveld / Journal of Transport Geography 11 (2003) 167–177

open space’’ (CEC, 1999, p. 36). Obviously, the ESDPdoes not go into detail on how to avoid ribbon devel-

opment, an issue that is, by nature, located at a lower

spatial level, although the makers of the ESDP are

clearly against it. In fact when we compare the final

ESDP with various drafts of it, it becomes clear that the

eurocorridor concept stirred up considerable debate

when preparing the final version of the ESDP.

The Noordwijk- and Glasgow-versions of the ESDP(CEC, 1997; British Presidency, 1998) explicitly advo-

cate the development of eurocorridors as an important

element of a European spatial development agenda.

While the final ESDP just advocates building bridges

between sector policies, the Glasgow document lists not

only specific policy goals but also states that eurocorri-

dors should be developed. Eurocorridors ‘‘could [be]

used as a conceptual tool for integrating policies relat-ing to the development of multinodality, cooperation

between cities, the improvement of infrastructure and

transport in more peripheral areas, the reduction of con-

gestion, international accessibility, etc. Such corridors

could contribute considerably to the cohesion of the

European territory’’ (British Presidency, 1998, p. 67). On

top of that, the document lists examples of eurocorri-

dors which have already emerged or that could be devel-oped and linked with existing ones. To the first category

belong corridors like Transmanche–London–Glasgow;

Amsterdam–Brussels–Paris; Brussels–Cologne–Hannov-

er–Berlin–Poznan–Warzaw; Rotterdam–Ruhr–Rhine–

Main–Stuttgart–Munich. To the second category belong

corridors like Dublin–Manchester–London–Transman-

che and Rotterdam–Hannover–Berlin (British Presi-

dency, 1998, p. 67).These early versions of the ESDP are clearly in line

with the preceding CCC-study. Eurocorridors are seen

as instrumental in spreading economic development

over the European territory: eurocorridors ‘‘can help

structure the territory of the whole continent.’’ (British

Presidency, 1998, p. 49). There are two plausible ex-

planations as to why such a eurocorridor approach was

toned down. The listing of specific eurocorridors prob-ably did not fit neatly into national spatial planning

policies. It is likely that in several countries no agree-

ment could be reached on the question of which areas

could or should be designated as eurocorridors. More

fundamental is the rejection by some Member States of

the eurocorridor concept in itself, particularly the ar-

gumentation in favour of corridor development. In these

countries it was assumed that eurocorridors would pavethe way for ribbon development. Two clear examples

are Belgium, where a fierce debate on corridor devel-

opment took place in the mid-1990s (Houthaeve, 1993;

Van Naelten, 1995) and the Netherlands. We will in-

vestigate the Dutch debate in some detail because this

debate illustrates the difficulties that especially spatial

planners have with the corridor concept.

3. The corridor concept put to the test: the example ofthe Netherlands

3.1. The debate

About a decade ago, the Dutch National Spatial

Planning Agency, part of the Ministry of Housing,

Spatial Planning and the Environment (better known by

its Dutch acronym as the Ministry of VROM), asked theNetherlands Economic Institute (NEI) to describe the

main spatial economic structure of the Netherlands

(Priemus, 2001). The NEI also proposed to investigate

the competitive position of the Dutch economy not only

in terms of inward investments but also by looking at

the potential of companies already located in the

Netherlands. This research was motivated in part by the

observation that not all companies were happy aboutlocating in cities. This proposal went considerably fur-

ther than the activities of the Ministry of VROM at the

time: the ministry was advocating the planning concept

of �urban nodes� and arguing for the establishment of

international companies at these nodes. So this was

what the world should look like according to the na-

tional spatial planning strategy. In contrast the NEI

stated that if one looked at the map, some �strips� be-came visible that were particularly attractive to inter-

nationally operating companies. These strips were

dubbed �corridors�. The resulting report �Development

strategies for Dutch regions and cities in an interna-

tional perspective� (NEI, 1995) can be interpreted as the

starting shot for discussions in the Netherlands on cor-

ridors.

The Ministry of Economic Affairs was quick to takeup the gauntlet. In a working paper, the Ministry indi-

cated its intention to pay more attention to economic

activities in spatial policy (EZ, 1999). They pointed out,

using maps and charts, that an expansion was taking

place from the Randstad to the East and to the South

along hinterland routes. The NEI concept of corridors

was adopted by this ministry (Fig. 1): corridor devel-

opment was put forward as a natural process, as anexpression of bottom-up preferences of the private sec-

tor for the location of firms.

With a sufficient supply of space in these corridors

this process ought to be capable of being accommo-

dated. With this paper the Ministry of Economic Affairs

provided the political response to the proposals included

in the NEI-report. Moreover, parties such as the

Chambers of Commerce and regional developmentcompanies supported these ideas. For them, corridors fit

neatly into their employment argument: the substantial

streams of goods flowing through corridors offered a

potential for derived activities (and thus employment)

and therefore deserved support. These actors felt that

the government should meet the location preferences of

the business community, even those outside the cities. A

Fig. 1. Spatial-economic core area of the Netherlands (source: EZ, 1997): stedelijk gebied (inclusief VINEX-locaties)––urban area including new

extensions; ruimtelijk-economische hoofdstructuur––spatial-economic main structure; hoofdweg––main road; hoofdweg als drager––main road as

spine of the spatial-economic structure.

H. Priemus, W. Zonneveld / Journal of Transport Geography 11 (2003) 167–177 171

coalition was born with the support of the Ministry of

Economic Affairs, employees� and employers� associa-tions, the regional Chambers of Commerce and devel-

opment companies (Van Duinen, 1995).By that time––the mid-1990s––the Ministry of

VROM had launched a large public debate on the spa-

tial structure of the country. In the final Discussion

Memorandum �Netherlands 2030� (VROM, 1997) four

spatial scenarios had been developed. One of these is

based on the structuring spatial impacts of water

structures and transport corridors: Flow Country (van

Uum, 1998). Corridors were absent in the three otherspatial scenarios. Although the corridor was present in

one vision on the future spatial structure of the country,

this was definitely not the vision endorsed by the min-

istry.

1 Policy preparation in the Netherlands follows somewhat corpo-

ratist paths (see Hajer and Zonneveld, 2000).

172 H. Priemus, W. Zonneveld / Journal of Transport Geography 11 (2003) 167–177

Shortly afterwards, the government started thepreparation of a new (Fifth) policy memorandum on

spatial planning (on average about every ten years such

a memorandum is produced, the first one published as

early as 1960). The Starting Memorandum on Spatial

Planning was published in the beginning of 1999 as a

foretaste of the Fifth Policy Document on Spatial

Planning. By no means the least important aim of this

document was to bridge the gap between the Ministry ofHousing, Spatial Planning and the Environment and the

other departments dealing with the spatial-economic

structure of the country: Economic Affairs; Agriculture,

Nature Management and Fisheries; and Transport,

Public Works and Water Management (Priemus, 1999).

The Starting Memorandum was endorsed by the min-

isters of the four departments listed above and can thus

be perceived as a cabinet paper. The then minister ofspatial planning declared in an interview (Cate, 1999)

that: ‘‘Corridors are not my idea. My ambitions go

further’’. Nevertheless he seemed to identify the corridor

as an empirical phenomenon in the Starting Memoran-

dum on Spatial Planning, according to the following

passage (VROM, 1999, pp. 39–41): ‘‘The dynamics of

the city are often stronger along the urban arterial roads

and in the large centres at the edge of an urban areathan in the inner cities. These dynamics tend to move

along these arterial roads and transport axes, mostly

because good accessibility is essential for maintain-

ing the dynamics. In spatial terms this takes place near

the large economic centres and along the transport

axes which provide the connections to the European

networks, not only in the Randstad but also in the re-

gions that lie between the Randstad, the Ruhr and theBrussels–Antwerp–Ghent region. As a result of this the

business activity in parts of Gelderland, North Brabant

and Limburg acquires a stronger international profile.

The companies grow there the most quickly, so that the

need for extra space for work but also for other urban

functions is sharply felt.’’ (translation HP/WZ).

Relevant to this was a plea by the official government

advisory council on spatial planning, the VROM-Raad(1999), for a change from unplanned corridor formation

to planned corridor development. The Starting Memo-

randum seems to introduce the corridor as a planning

concept as well. According to the Starting Memo-

randum, by adapting the space within corridors to the

desired differentiation in residential and working envi-

ronments, the necessary dynamics can acquire form and

substance and the pressure on green space outside canbe minimised. The argument runs as follows: one should

promote selective and bundled urbanisation where eco-

nomic opportunities occur and have green spaces near

areas where urbanisation takes place. Erosion of sup-

port for the existing cities must be avoided, not only

from an economic point of view, but also in terms

of society. What is required is a limited number of

well-situated corridors. Otherwise there would be athreat to the vitality of the cities and the green spaces

between corridors and cities. Corridors are sustained by

bundles of highways, rail and where possible water and

pipe connections linked together through multimodal

transfer points. A limited number of nodes on these

connections would become profiled as top national and

international locations. These would be the existing

cities and a few newly identified transfer points noted fortheir good accessibility and available space. Nodes and

corridors belong to each other. Improvement of �green�functions is needed both in and around the corridors.

Similarly, space should be created at nodes for a broad

range of residential and work environments, inter-

spersed with green areas. This arrangement would lead

to more variety, while at the same time maintaining

open natural areas and water for recreation and for useas buffers between the cities within and between the

corridors. The international imbedding implies that a

corridor is based on the trans-European infrastructure

networks (eurocorridors) and performs an important

function for the transport of passengers and goods be-

tween large urban areas in Europe (Fig. 2). With an eye

for international competitiveness, complete urban cen-

tres with high-quality services must be developed forcompanies as well as residents. A selective and con-

trolled spatial development must guarantee that the

corridors do not compete with but complement the

function of big cities.

The Dutch Social-Economic Council (SER), com-

prised of the national government and organisations of

the employers and employees, also issued an advisory

document on the Starting Memorandum (SER, 1999). 1

The SER (1999) argued that a continuation of un-

planned corridor formation would have both ecological

and economic drawbacks. The SER distanced itself from

the views in circulation in which a corridor was con-

ceived as a strip of land along transport axes with its

accessibility determined by the development of eco-

nomic activities. The consideration of coherent planning

for a few corridor areas must allow space for economicpotential while at the same time providing protection for

green functions and the maintenance of open space. To

describe this, the SER invoked the popular �string of

beads� concept (SER, 1999, p. 43).

3.2. Corridors or urban networks?

Looking at the Dutch discussion on corridors, three

distinct meanings of the concept �corridor� can be dis-

tinguished (Priemus, 2001; EZ, 1997, p.114; see also: EZ,

1999).

Fig. 2. Eurocorridors in NW Europe (source: EZ, 1997): metropool––metropolitan area; stedelijk gebied buiten metropool––urban area outside

metropolitan area; megacorridor (met spoor- en autoweg)megacorridor (with railroad and motorway).

H. Priemus, W. Zonneveld / Journal of Transport Geography 11 (2003) 167–177 173

The corridor as an infrastructure axis. Here corridor is

defined in terms of traffic engineering. A corridor is used

in this sense by the Ministry of Transport, Public Works

and Water Management when developing or improving

(interconnected) infrastructure modalities on a particu-

lar route. A simultaneous approach to the various mo-

dalities within a corridor offers important advantages,such as opportunities for bundling, and with it, a re-

striction of further criss-cross traffic.

The corridor as an economic development axis. Here

an implicit or explicit relationship is supposed between

opportunities for economic development and major

traffic axes. This point of view assumes that the spatial

results of functional economic activities are strongly

determined by the infrastructure network. The numberof potential corridors in the Netherlands is limited, and

their precise boundaries are of secondary importance.

What is more important is the influence of the transport

axes. The NEI (1995) used the corridors concept with

this meaning in the study quoted in the first section.

The corridor as an urbanisation axis. Here the infra-

structure network functions as the basis for the direc-

tions of future urbanisation for residential and workactivity. This definition is related to the aim of sup-

porting public transport infrastructure. This is the ap-

proach used by the Ministry of Transport, Public Works

and Water Management (V&W, 1995) at the local level

in the study �A View of Urbanisation and Mobility�.All three interpretations of the corridor concept are,

in fact, a good example of what could be referred to as

�implicit theory�. The assumption is that traffic and in-

frastructure are not only derived from social and eco-nomic processes but to a high degree determine these

functions as well. Following this logic, corridors have a

considerable impact on spatial developments and spatial

patterns. Especially areas through which large volumes

of passenger and freight transport pass are attractive for

the location of companies, especially those operating in

the realm of distribution and logistics. Eventually this

would lead to urbanisation in places located betweenpresent urban centres, starting with some sort of ribbon

development, and then giving way to new urban growth

poles. It is at this point that spatial policy is playing––or

will have to play––an important role. As we have seen,

most spatial planners do not like the idea of ribbon

development, wishing instead to concentrate building

activities in existing or––in cases where this cannot be

avoided––new urban centres. This is an interesting bat-tlefield for the three most relevant Dutch ministries and

the societal interests they represent: (1) the Department

174 H. Priemus, W. Zonneveld / Journal of Transport Geography 11 (2003) 167–177

of Transport which, almost by nature, mainly looks atthe capacity of infrastructure networks and a smooth

circulation of traffic flows; (2) the ministry of Economic

Affairs prioritising an abundant supply of space for

economic development at attractive locations and––for

this reason––embracing the (mega)corridor concept; (3)

the ministry responsible for spatial planning, striving for

a neat, orderly and well-contained urbanisation of so-

ciety, which does not disrupt green belts, scenic areasand nature reserves (and therefore rejecting all corridor

concepts).

This whole discussion represents a tremendous task

for spatial planning: how can it combine the endogenous

qualities and characteristics of areas and zones sur-

rounding cities with the transportation functions and

potentials of railway stations, airports and access points

to the motorway system? (see Bertolini and Spit, 1998).So far Dutch spatial planning strived to achieve con-

tained urbanisation, and well-defined compact cities.

Looking at the spatial distribution of cities, towns and

villages, their functional relationships, their growing size

and intertwining of labour and housing markets and,

finally, the dense network of infrastructure it seems

logical that spatial planning accepts the reality of net-

work cities and urban networks even when the presentadministrative organisation is not at all equipped to

cope with the emerging reality.

The challenge seems to have been taken up by the

national government. The main planning concept in the

Fifth Policy Document on Spatial Planning (VROM,

2001) has become that of the �urban network�. Urban

networks are economic–geographic zones that, in spatial

terms, take on the form of a network of compact cities.Not every compact city needs to strive separately for

completeness of functions and services, because this

completeness can be reached at the level of a network.

Urban networks require the fulfilment of two condi-

tions. First, cities within an urban network must not

compete with each other in spatial terms; they must

collaborate about where best to accommodate various

functions. Second, urban areas within urban networksneed to be well connected with each other via integrated

systems of public transport.

At first sight, the concept of urban networks fits very

well with the rise of �network society� and the network

economy in which economic and social relationships

become more open and horizontal. Urban networks

have replaced corridors as the spatial planning concept

in the Fifth Spatial Planning Memorandum. Neverthe-less, the question remains whether the empirically ob-

servable spatial phenomenon of corridors can still be

denied or ignored. And the question also remains how

the spatial organisation of corridors should be mapped

out. A Dutch parliamentary workgroup set up for

evaluating national spatial planning policy seriously

regrets that the Dutch debate on corridors was com-

pletely dominated by the issue of urban form. The as-sociation with ribbon development had made the mere

mention of the corridor concept taboo, while the con-

cept of eurocorridor highlights the necessity for proper

coordination of the various policy domains. Here the

workgroup pointed to the (final) ESDP (Parlementaire

Werkgroep Vijfde Nota Ruimtelijke Ordening, 2000, p.

277 ff.) As we have seen, in the �Starting Memorandum�the government seemed willing to concede that corridordevelopment is not the same as ribbon development but,

in so doing, it still only paid attention to the question of

urban form. Thus the criticism of the parliamentary

workgroup is valid. It is also obvious that the European

dimension is entirely beyond the horizon. Also missing

is the point brought forward by the ESDP that euro-

corridors are basically large bundles of infrastructure

crossing European space and exerting influence on Eu-ropean patterns of urbanisation and economic devel-

opment (CEC, 1999, pp. 70–71).

In this special issue, this tension between transport

functions, economic functions and spatial functions will

be raised again and again. Naturally, it is the task of

politicians and officials to reconcile these functions. In

this way, the growing interest in both scholarly as well as

political circles for polynuclear urban regions, networkcities and urban networks is particularly relevant. Ur-

banisation is thus viewed at a higher (regional) level

of scale in a manner that takes into account the acces-

sibility of urban cores for individual and public trans-

port, the variation in residential preferences of

households and the differentiated location preferences of

businesses.

4. Corridor challenges

When we observe the development of traffic infra-structure and the dynamics of megacorridors between

urban areas, we are confronted with a number of specific

challenges.

(1) How should long distance and short distance traffic

be regulated? More and more, the solution to this

question is being sought in disentangling the infra-

structure of these two traffic types. For example,

one can levy fees for long-distance traffic (e.g. toll

roads, road pricing), and for short-distance traffic

during parts of the day with high congestion. In gen-eral, this concerns an optimalisation of the traffic in-

frastructure.

(2) How should the interconnectivity and interopera-

tionability of networks be promoted? This issue re-

quires a reasoned and hierarchical design of

networks and infrastructure with multimodal nodes

for both freight (terminals) and passenger transport

(stations, transfer stations).

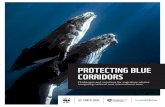

Fig. 3. The seven most important megacorridors in North West Eu-

ropa: (1) Randstad–Flemish Diamond; (2) Randstad–RheinRuhr; (3)

RheinRuhr–Flemish Diamond; (4) Flemish Diamond–Lille; (5) Lille–

Paris; (6) Lille–London; (7) London–West Midlands.

H. Priemus, W. Zonneveld / Journal of Transport Geography 11 (2003) 167–177 175

(3) How can synergy between urban patterns and trafficinfrastructure networks be increased? This question

is related to the accessibility of housing areas and

business parks, the multimodality of nodes and the

relationship between urban areas and green and

water structures.

(4) How can one prevent corridor development from

taking place at the expense of existing urban centres?

How can one prevent infrastructure networks fromfragmenting the open countryside and damaging

natural areas? How can the spatial quality of land-

scapes and the biodiversity and ecological signifi-

cance of natural areas be guaranteed with the

development of corridors? These issues will require

gaining further insight into the location and logic

of green–blue networks (we add the dimension of

�blue� because of the increasing relevance of watersystems for spatial planning), and prioritising these

as much as possible over traffic network routes.

Where conflicts arise, underground infrastructure

or stacking (e.g. eco-flyovers) may offer a way out.

(5) Corridors situated between polynuclear urban re-

gions usually cross municipal borders, regional bor-

ders and even national borders. This necessitates the

coproduction of policy between municipalities, re-gional authorities and national governments, and

also between different sectors: spatial planning,

housing, economic affairs, agriculture, environment

and transportation. Particularly differences in regu-

lation and policy practices between nations must

be overcome. Successful examples of multi-level

governance, policy coproduction and multi-actor

systems can offer guidance in this regard.

5. This issue

This issue of the Journal of Transport Geography is

informed by a large research project called CORRI-

DESIGN. This project investigated the development of

megacorridors in north-west Europe. Seven megacorri-

dors were identified as the starting point of the analyses

(see Fig. 3): (1) the Randstad–Flemish Diamond corri-

dor; (2) the Randstad–RheinRuhr corridor; (3) the

RheinRuhr–Flemish Diamond corridor; (4) the FlemishDiamond–Lille corridor; (5) the Lille–Paris corridor; (6)

the Lille–London corridor; (7) the London–West Mid-

lands corridor. CORRIDESIGN started from the ob-

servation that regional economies are entwined on a

European scale. CORRIDESIGN examined whether, to

what extent and how this process towards a network

society is spatially linked with the development of cross-

border megacorridors or bundles of infrastructures be-tween the large urban regions in north-west Europe.

This emphasis on the possible development of cross-

border megacorridors implied a focus of CORRIDE-

SIGN on transnationality. Important questions in

CORRIDESIGN included: which types of corridor de-

velopment should be stimulated, slowed down or un-done?; where should corridors be developed, and why

there?; should the growing spatial coherence within

megacorridors be followed by institutional coherence?

if so, which public or private parties should be involved?

CORRIDESIGN was a joint project of the OTB

Research Institute for Housing, Urban and Mobility

Studies, Delft University of Technology (Lead Partner);

The Bartlett School of Planning, University CollegeLondon; School of Planning and Housing, University of

Central England, Birmingham; Department of Social

Sciences Administration, London School of Economics;

Institute of Urban and Regional Planning, Catholic

University of Leuven; Institute for Traffic Planning and

Design, Essen University; and the Institut F�eed�eeratif deRecherche sur les Economies et les Soci�eet�ees Industrielles(IFRESI), Lille (with the collaboration of Territories,Sites & Cit�ees). The project was co-financed by the Eu-

ropean Regional Development Fund under the IN-

TERREG IIC Programme, a European Community

Initiative concerning Transnational Cooperation on

Spatial Planning.

The contribution by Chapman, Pratt, Larkham and

Dickins on the London–West Midlands corridor clearly

illustrates how difficult it is to arrive at improved policyintegration when so many different opinions exist about

what a corridor exactly entails. Nevertheless the authors

also show that there is a great deal of consensus about

spatial developments within a corridor. Irrespective of

their background, stakeholders within the London–

West Midlands corridor rejected any sort of linear urban

development but instead embraced a form of concen-

tration. For lack of a better term, this is also referred toas �beads on string� development.

176 H. Priemus, W. Zonneveld / Journal of Transport Geography 11 (2003) 167–177

Sch€oonharting, Schmidt, Frank and Bremers concen-trate primarily on what consequences the intersection of

various large European corridors will have on a large

urban area such as RheinRuhr. The most urgent task,

namely achieving a fundamental improvement of the

constituent relations between various infrastructure

networks, is difficult to bring about without having a

minimum level of administrative integration. Rhein-

Ruhr is just at the beginning of what could be called acapacity building phase, although a few important new

initiatives are also underway. These authors also make it

clear that there is no support whatsoever in the urban

region to understand corridor development as a con-

vergence of urban areas and business locations.

The analysis offered by Romein, Trip and De Vries

orients itself primarily to the area between the polynu-

clear urban regions of the Randstad and the FlemishDiamond. This �in between area� is an important conduit

for large-scale infrastructure binding the two urban

networks and the mainports within them. The authors

show that the decisions taken regarding infrastructure

(e.g. new connections, upgrading of existing ones), is still

too much the exclusive domain of national governments

and policy sectors. They argue for new kinds of multi-

level governance.Albrechts and Coppens take a closer look at the

conflicts between megacorridor development and the

area-specific qualities within important nodes. Their

case study is the new High Speed Train terminal Brus-

sels South. Inspired by concepts such as �space of flows�and �space of places�, each of which follows its own lo-

gic, the authors unpack the events that have transpired

in order to transform this station area into what it isnow, not only as a HST terminal but also as a new node

for economic activity. They painstakingly examine the

mechanisms influencing transport companies and land-

owners. As a result, they arrive at a number of funda-

mental recommendations for policy practice in which

the concept of subsidiarity figures prominently.

Next, De Vries and Priemus examine in detail what

the main conclusions appear to be in the previous fourcontributions: corridor development in particular de-

mands an improvement of the governance structure with

respect to infrastructure, urbanisation and economic

development. They argue that corridor development

clearly requires an improvement in the coordination

between various policy areas: (1) an improvement in the

coordination between different policy sectors and seg-

ments of society; (2) an improvement in cooperationbetween public and private organisations; (3) improve-

ment in coordination at the cross-border level because

corridors do in fact cross-borders; (4) and finally an

improvement in the coordination between central and

local governments.

In summary, the various papers of this special issue

demonstrate––including this introduction––that (euro

or mega) corridors should not be conceived as an entityoccupying physical space. Although corridors originate

with the large-scale bundling of infrastructure, they

certainly do not constitute a new urban field. Corridors

comprise the arena within which an attempt must be

made to arrive at an integration of a multitude of social

interests. In this sense, a corridor is neither a sectoral

nor a spatial concept, but rather the indication of a

challenge: that of improving the governance of infra-structure and area development.

Acknowledgements

The background of this paper and this special issue

is informed by research conducted within the frame-

work of the CORRIDESIGN project co-financed by

the European Community through the INTERREG

IIC programme for the North-West Metropolitan Area

(NWMA). The contribution of Wil Zonneveld is part of

the NWO-ESR programme �Spatial Developments and

Policies in Polynuclear Urban Configurations inNorthwest Europe� which was financed by NWO, BNG

(Dutch Municipalities Bank) and the municipalities of

Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague and Utrecht.

References

Bertolini, L., Spit, T., 1998. Cities on Rails: The Redevelopment of

Railway Station Areas. Spon Press, London.

British Presidency, 1998. European Spatial Development Perspective

(ESDP): Complete draft; Meeting of ministers responsible for

spatial planning of the Member States of the European Union.

Glasgow, 8 June 1998.

Cate, F.T., 1999. Minister Pronk bewaart ruimtelijke visie voor Vijfde

Nota: �Corridors zijn niet mijn idee. Mijn ambitie gaat verder�(Minister Pronk maintains a spatial vision for the Fifth Policy

Document: �Corridors are not my idea. My ambition stretches

further�). Binnenlands Bestuur, 19 February, pp. 18–19.

CEC, Commission of the European Communities, 1994. Europe

2000+; Cooperation for European territorial development. Office

for the Official Publications of the European Communities,

Luxembourg.

CEC, Commission of the European Communities; Directorate General

XVI, 1996. The prospective development of the central and capital

cities and regions, Regional Development Studies No. 22. Office for

Official Publications of the European Communities, Luxembourg.

CEC, Commission of the European Communities, 1997. European

Spatial Development Perspective: First Official Draft; Presented at

the Informal Meeting of Ministers Responsible for Spatial Plan-

ning of the Member States of the European Union, Noordwijk,

June 1997. Office for Official Publications of the European

Communities, Luxembourg.

CEC, Commission of the European Communities, 1999. European

Spatial Development Perspective. Towards Balanced and Sustain-

able Development of the Territory of the European Union. Agreed

at the Informal Council of Ministers responsible for Spatial

Planning in Potsdam, May 1999. Office for Official Publications of

the European Community, Luxembourg.

H. Priemus, W. Zonneveld / Journal of Transport Geography 11 (2003) 167–177 177

Duinen, L. van, 1995. Eindrapport NUBS-corridor (Final report

NUBS-corridor); Studierapport. Provincie Noord-Brabant, Den

Bosch.

EZ, Ministerie van Economische Zaken (Ministry of Economic

Affairs), 1997. Ruimte voor Economische Dynamiek (Space for

Economic Dynamics), Een verkennende analyse van ruimtelijk-

economische ontwikkelingen tot 2020. EZ, The Hague.

EZ, Ministerie van Economische Zaken (Ministry of Economic

Affairs), 1999. Nota Ruimtelijk-Economisch Beleid (Memorandum

Spatial Economic Policy). EZ, The Hague.

Fullerton, B., Knowles, R.D., 1991. Scandinavia. Paul Chapman

Publishing, London.

Graham, S., Marvin, S., 2001. Splintering urbanism: networked

infrastructures, technological mobilities and the urban condition.

Routledge, London.

Hajer, M.A., 2000. Transnational networks as transnational policy

discourse: some observations on the politics of spatial development

in Europe. In: Salet, W., Faludi, A. (Eds.), The Revival of Strategic

Spatial Planning. Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and

Sciences, Amsterdam, pp. 135–142.

Hajer, M.A., Zonneveld, W., 2000. Spatial planning in the network

society––rethinking the principles of planning in the Netherlands.

European Planning Studies 8 (3), 337–355.

Hall, P., 1996. Cities of Tomorrow: An Intellectual History of Urban

Planning and Design in the Twentieth Century, Updated ed.

Blackwell Publishers, Oxford.

Hohenberg, P.M., Hollen Lees, L., 1995. The Making of Urban

Europe 1000–1994. Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

Houthaeve, R., 1993. Corpulente corridors: over de ruimte en

mythologie van Marc van Naelten (Corpulent corridors: about

the space and mythology of Marc Van Naelten). Planologisch

Nieuws 13 (1), 54–61.

Lemberg, K., 1997. Danish Urban Planning: Urban Developments in

the Copenhagen Region. In: Bosma, K., Hellinga, H. (Eds.),

Mastering the City; North-European City Planning 1900–2000.

NAI Publishers/EFL Publications, Rotterdam/The Hague, pp. 20–

31.

Mumford, L., 1937. What Is a City. Architectural Record LXXXII.

Reprinted in: LeGates, R. (Ed.), 1996. The City Reader. Routl-

edge, New York, pp. 183–188.

NEI, Nederlands Economisch Instituut (Netherlands Economic Insti-

tute), 1995. Ontwikkelingsstrategie€een voor Nederlandse regio�s en

steden in internationaal perspectief (Development strategies for

Dutch regions and cities in international perspectives). VNO-

NCW, The Hague.

Parlementaire Werkgroep Vijfde Nota Ruimtelijke Ordening (Parlia-

mentary Working Party Fifth Policy Document on Spatial Plan-

ning), 2000. Notie van ruimte. Op weg naar de Vijfde Nota

ruimtelijke ordening (Notion of space: On the road to the Fifth

Policy Document on Spatial Planning), Tweede Kamer 27 210, No.

1–2. Sdu Publishers, The Hague.

Priemus, H., 1999. Four ministries, four spatial planning perspectives?

dutch evidence on the persistent problem of horizontal coordina-

tion. European Planning Studies 7 (5), 563–585.

Priemus, H., 2001. Corridors in the Netherlands: apple of discord in

spatial planning. TESG, Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale

Geografie 92 (1), 100–107.

SER, Sociaal-Economische Raad (Social-Economic Council), 1999.

Advies Startnota ruimtelijke ordening en Perspectievennota verk-

eer en vervoer (Advice on Starting Memorandum Spatial Planning

and Perspectives Policy Document Traffic and Transport), Advies

99/06. SER, The Hague.

Uum, E. van, 1998. Spatial planning scenarios for the Netherlands,

TESG. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 89 (1),

106–116.

Van Naelten, M., 1995. Het corridor-model; Een planologisch �verhaal�met en over cijfers, feiten en betwistingen (The corridor model: een

planning story with and about figures, facts and disputes).

Planologisch Nieuws 13 (1), 30–50.

VROM, Ministerie van Volkshuisvesting, Ruimtelijke Ordening en

Milieubeheer, 1997, Nederland 2030––Discussienota (Netherlands

2030––Discussion Memorandum). VROM, The Hague.

VROM, Ministerie van Volkshuisvesting, Ruimtelijke Ordening en

Milieubeheer (Ministry of Housing, Spatial Planning and the

Environment), 2001. Ruimte maken, ruimte delen, Vijfde Nota

Ruimtelijke Ordening deel 1: Ontwerp (Fifth Policy Document on

Spatial Planning part 1: draft). VROM, The Hague.

VROM, Ministerie van Volkshuisvesting, Ruimtelijke Ordening en

Milieubeheer, Ministerie van Economische Zaken, Ministerie van

Landbouw, Natuurbeheer en Visserij en Ministerie van Verkeer en

Waterstaat (Ministry of Housing, Spatial Planning and the

Environment, Ministry of Economic Affairs, Ministry of Agricul-

ture, Ministry of Transport, Public Works and Watermanage-

ment), 1999. Startnota Ruimtelijke Ordening (Starting

Memorandum Spatial Planning). Sdu Publishers, The Hague.

V&W, Ministerie van Verkeer en Waterstaat (Ministry of Transport,

Public Works and Water Management), 1995. Visie op verstedel-

ijking en mobiliteit (A View of Urbanisation and Mobility). V&W,

The Hague.

VROM-Raad, 1999. Corridors in balans: van ongeplande corri-

dorvorming naar geplande corridorontwikkeling (Corridors

in balance: from unplanned corridor formation to planned

corridor development), Advies 011. VROM-Raad, The

Hague.

Whebell, C.F.J., 1969. Corridors: a theory of urban systems. Annals

of the Association of American Geographers 59 (1), 1–26.