Validation of the Orientation to Life Questionnaire in Norwegian Adolescents, Construct Validity...

Transcript of Validation of the Orientation to Life Questionnaire in Norwegian Adolescents, Construct Validity...

1 23

Social Indicators ResearchAn International and InterdisciplinaryJournal for Quality-of-Life Measurement ISSN 0303-8300 Soc Indic ResDOI 10.1007/s11205-013-0536-z

Validation of the Orientation to LifeQuestionnaire in Norwegian Adolescents,Construct Validity Across Samples

Unni Karin Moksnes & Gørill Haugan

1 23

Your article is protected by copyright and all

rights are held exclusively by Springer Science

+Business Media Dordrecht. This e-offprint

is for personal use only and shall not be self-

archived in electronic repositories. If you wish

to self-archive your article, please use the

accepted manuscript version for posting on

your own website. You may further deposit

the accepted manuscript version in any

repository, provided it is only made publicly

available 12 months after official publication

or later and provided acknowledgement is

given to the original source of publication

and a link is inserted to the published article

on Springer's website. The link must be

accompanied by the following text: "The final

publication is available at link.springer.com”.

Validation of the Orientation to Life Questionnairein Norwegian Adolescents, Construct Validity AcrossSamples

Unni Karin Moksnes • Gørill Haugan

Accepted: 2 December 2013� Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2013

Abstract In spite of the potential significance of sense of coherence (SOC) for adolescent

health and well-being, the past decades have yielded limited progress in investigating the

psychometric properties of the most used inventory measuring SOC, The Orientation of

Life Questionnaire (OLQ) in adolescents. The present study aimed at investigating the

factorial validity and reliability of the Norwegian version of the 13 item OLQ based on two

adolescent samples 13–18 years from Norway. Concerning the dimensionality of the OLQ,

two measurement models were tested using confirmatory factor analysis; a one-factor

model and a three-factor-model. The results showed that a three-factor solution with

correlated residual variances between item 2 and item 3 showed the best fit across the two

adolescent samples, although five items revealed low factor loadings. The dimensions were

highly correlated and showed adequate composite reliability. The present results indicate

that the 13 item OLQ has potential as an instrument assessing SOC in adolescents.

However, more psychometric testing of the instrument is required in reference to the

modified factor structure and the low reliability found on some of the items in OLQ.

Keywords Confirmatory factor analysis � Psychometric evaluation � Sense

of coherence � Adolescents

1 Introduction

The medical sociologist Aron Antonovsky introduced the theory of Salutogenesis which

focuses on what are the sources for people’s resources and capacity to create health

U. K. Moksnes � G. HauganFaculty of Nursing, Sør-Trøndelag University College, Trondheim, Norway

U. K. Moksnes (&) � G. HauganResearch Centre for Health Promotion and Resources, Mauritz Hansens gt 2, 7030 Trondheim, Norwaye-mail: [email protected]

123

Soc Indic ResDOI 10.1007/s11205-013-0536-z

Author's personal copy

(Salutogenesis) rather than the classic focus on risk, ill health and disease (Pathogenesis;

Antonovsky 1979, 1987). Antonovsky was interested in the explanation for why some

people, regardless of major stressful situations, manage to stay healthy and live good lives,

while others do not (Eriksson and Lindstrom 2005). He formulated the explanation in terms

of the key concepts sense of coherence (SOC) and general resistance resources (GRR)

(Antonovsky 1979; Eriksson 2007).

The first key concept SOC is defined as ‘‘a global orientation that expresses the extent to

which one has a pervasive, enduring though dynamic feeling of confidence that (1) the

stimuli deriving from one’s internal and external environments in the course of living are

structured, predictable, and explicable, (2) the resources are available to one to meet the

demands posed by these stimuli; and (3) these demands are challenges, worthy of

investment and engagement’’ (Antonovsky 1987, p. 19). These three components, termed

comprehensibility, manageability and meaningfulness are thought to be highly interrelated

but separable, forming the construct of SOC. Comprehensibility is a cognitive component

and refers to the degree to which individuals sense that information about themselves and

the social environment is not only understandable, but also ordered, structured, and con-

sistent. However, perceiving events as comprehensible does not mean that they are com-

pletely predictable. Manageability is an instrumental component and refers to the degree to

which individuals feel that available resources are sufficient to adequately cope with the

demands posed by internal and external stimuli. Meaningfulness is a motivational com-

ponent and refers to the extent to which individuals feel that certain areas of life are worthy

of time, effort, personal involvement and commitment (Antonovsky 1987; Eriksson 2007).

According to Antonovsky, the SOC concept reflects an individual resource and disposi-

tional orientation that enables the individual to reflect on its external and internal resources,

and resolve tension in a health-promoting way (Eriksson and Lindstrom 2006).

The other key concept in the salutogenic theory is the resources available to help one to

improve one’s state of health. Antonovsky defined the term general resistance resources

(GRR) as both material and non-material qualities that could be found within people,

bound to their person and capacity, but also to their immediate and distant environment

(Antonovsky 1987). An important point is not what resources are available but the ability

to use and re-use the different resources for intended purpose (Eriksson 2007). A person

with a strong SOC is able to mobilize GRR to promote effective coping. This resolves

tension in a health-promoting manner, and leads toward the salutary health end of the

health ease/dis-ease continuum (Eriksson and Lindstrom 2005; Nielsen and Hansson

2007).

A strong SOC is associated with good health, especially mental health and quality of life

in adult populations (Eriksson and Lindstrom 2006; Lindstrom and Eriksson 2010; Nilsson

et al. 2010). In contrast, far less is known about the role and nature of SOC during

childhood and adolescence, although these developmental stages are considered important

to the development of SOC (Lindstrom and Eriksson 2010; Rivera et al. 2012). However,

previous studies have shown that SOC is an important salutary resource in association with

different health outcomes and well-being in adolescents (Moksnes et al. 2012; Neuner et al.

2011; Nielsen and Hansson 2007; Simonsson et al. 2008; Oztekin and Tezer 2009). It can

therefore be no doubt that SOC constitutes an issue of importance to the broader under-

standing of adolescent health. Consequently, the availability of a valid and reliable

instrument to measure SOC in the adolescent population is required, since the source and

nature of adolescent SOC may be substantially different to how the construct is recognized

in adult populations.

U. K. Moksnes, G. Haugan

123

Author's personal copy

Antonovsky developed the Orientation to Life Questionnaire (OLQ) to operationalize

SOC. The questionnaire exists in two forms: a longer version consisting of 29 items and a

shortened 13 item form (Antonovsky 1987). These two questionnaires are the original ones

and the 13 item version was used for the present study. The OLQ has been translated and

used in at least 43 languages and seems to be a cross-culturally valid, reliable and feasible

instrument, especially in adult samples (Eriksson and Lindstrom 2005; Lindstrom and

Eriksson 2010).

According to Antonovsky (1993) the OLQ comprises one general factor of SOC with

three correlated components of comprehensibility (5 items), manageability (4 items), and

meaningfulness (4 items). However, previous studies have shown that the factor structure

of the scale is not completely clear and seems to measure a multidimensional rather than a

one-dimensional construct (Eriksson and Lindstrom 2005). Studies investigating the factor

structure of the OLQ based on exploratory and confirmatory approaches in adult and older

populations have shown support for a three-factor structure (Ding et al. 2011; Gana and

Garnier 2001), a second-order three factor structure (Ding et al. 2011; Feldt et al. 2007;

Naaldenberg et al. 2011; Richardson et al. 2007) and a one-factor structure (Hittner 2007).

Accordingly, the construct validity of the OLQ 13 does not seem to be clear in reference to

that different factor structures are evident in different populations. It may also be a

question whether the items included in the instrument adequately represent the construct of

SOC and that there may be variations in how the items are understood across different

cultures and age groups. Validations of the factor structure in adolescent populations are

less investigated, but previous studies have found support for a one-factor structure in a

sample of Swedish adolescents (Hagquist and Andrich 2004).

The 13 item OLQ scale has been reported to have internal consistency comparable to

the 29 item version with Cronbach’s alpha ranging between 0.70 and 0.92 (Eriksson and

Lindstrom 2005; Hittner 2007). The internal consistency of the 13 item OLQ are less

evident in adolescent samples, however, studies have reported Cronbach’s alpha values of

0.75 (Braun-Lewensohn and Sagy 2010), 0.82 (Rivera et al. 2012) and 0.86 (Nielsen and

Hansson 2007).

The present psychometric evaluation work is important in order to establish the utility

of an assessment tool aimed for use in adolescent populations, and to allow cross-national

recommendations with regard to the applicability, and broad usefulness of OLQ. Assess-

ment of SOC in adolescent populations is also important for evaluation of educational

programs designed to improve SOC, health and well-being among adolescents.

The aim of the present study was to test the factorial validity and reliability of the 13

item version of the OLQ. Based on theory of the dimensionality of SOC and previous

psychometric validations of the instrument, two hypothesized models of SOC were tested:

A one-factor model (Hagquist and Andrich 2004) and a three-factor model comprising

three correlated dimensions of comprehensibility, manageability and meaningfulness

(Ding et al. 2011; Gana and Garnier 2001).

2 Method

2.1 Participants

The first cross-sectional sample (sample 1) comes from a survey involving the participation

of six (three urban and three rural) public elementary and secondary schools in two

counties in Mid-Norway. A total of 1,229 questionnaires were distributed and the number

Validation of the Orientation to Life Questionnaire

123

Author's personal copy

of completed questionnaires which were returned was 1,209, giving an overall response

rate of 98.4 %; 617 (51.0 %) were girls and 586 (48.5 %) were boys (gender was not

identified for six of the participants). The age range of the sample in the present study was

13–18 years, and 26 subjects were excluded, leaving n = 1,183 cases in the analyses.

The second cross-sectional sample (sample 2) comes from a survey involving public

elementary and secondary schools in Mid-Norway. A total of 1,924 students were asked to

participate in the study and 1,289 completed questionnaires, giving a response rate of

67 %. Non responses were mainly due to students being absent when the questionnaire was

administered, or students who declined to answer the questionnaire. The age range of the

sample in the present study was 13–18 years, and the data analyses were therefore

undertaken for n = 1,239; 634 (51.2 %) were girls and 603 (48.7 %) were boys (gender

was not identified for two participants). The mean age for the entire sample was 15.00

(SD = 1.62); for boys 14.99 (SD = 1.63) and for girls 15.02 (SD = 1.63).

2.2 Procedure

The two data collections were approved by the regional committees for medical research

ethics (REK) and the Norwegian social science data services (NSD). The main author was

responsible for collecting the data for sample 1 and was partaking in the data collection for

sample 2. The project was funded by Sør-Trøndelag University College. The headmaster at

each school approved the content of the questionnaire prior to agreeing to participate in the

surveys.

In the data collection for sample 1, passive consent from the participants was found to

be sufficient because no personal identifying data were collected. Adolescents or their

parents responded only if they did not want their child to participate. As such, any ado-

lescent who did not have an active decline was eligible to be part in the study, which might

have increased the response rate. The adolescents and their parents received an information

letter which briefly explained the purpose of the study. Questionnaire administration was

completed in one section, in whole class groups during one regular school hour of 45 min.

The data were collected during September and October 2008.

In the data collection for sample 2, all the students and parents to students younger than

16 years received an information letter that briefly explained the purpose of the study.

According to research ethical guidelines, written consent was claimed from the participants

and from their parents when students were younger than 16 years old. Questionnaire

administration was completed in whole class groups, during one regular school period of

45 min. The data were collected during October and November 2011.

2.3 Measures

2.3.1 Sense of Coherence

Sense of coheren was assessed by means of a Norwegian 13 item version of the Orientation

to Life Questionnaire based on Antonovsky’s theory (Antonovsky 1987). The respondents

are requested to mark their response to each item on a seven-point scale with two

anchoring verbal responses, for example ‘‘very seldom or never’’ and ‘‘very often.’’ The

total sum ranges from 13 to 91 and higher score indicates a stronger SOC (Antonovsky

1979, 1987). The items included in the instrument are presented in Table 1.

U. K. Moksnes, G. Haugan

123

Author's personal copy

2.4 Statistical Analyses

Data were screened and analysed using the SPSS version 20.0 and Lisrel 8.8 for Windows.

The analyses were done in two steps; sample 1 was used as model sample to evaluate the

factor structure of the 13 item OLQ. In the second step, the procedure was repeated and the

same measurement models were tested in sample 2 in order to investigate the factorial

validity across samples. Mean scores and standard deviations were calculated on each item

and for the three dimensions of comprehensibility, manageability and meaningfulness.

Pearson product-moment correlation was used to test bivariate associations between the

items and the three dimensions. Internal consistency for each original dimension in both

samples was examined with Cronbach’s alpha. Reliability was further investigated in CFA

by means of composite reliability, where values C0.60 are acceptable whereas values

C0.70 are considered to be good (Bagozzi and Yi 1988; Hair Black Babib and Anderson

2010).

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to test the factor structure of the OLQ.

Test of multivariate normality on both samples displayed significant skewness and kur-

tosis. Since the standard errors are estimated under non-normality, the Satorra-Bentler

scaled Chi square statistic was applied as a goodness-of-fit statistic which is the correct

asymptotic mean under non-normality. The models were tested using the sample asymp-

totic covariance matrix and robust maximum likelihood estimation (RML) (Brown 2006).

Altogether, two models were tested in this study: a one-factor model, and a three-factor-

model.

Table 1 Items included in the OLQ 13-item version

Item Item description

1 Do you have the feeling that you really don’t care about what is going on around you?

2 Has it happened in the past that you were surprised by the behaviour of people whom you thoughtyou knew well?

3 Has it happened that people whom you counted on disappointed you?

4 Until now your life has had: no clear goals or purpose at all …vs…. very clear goals and purpose

5 Do you have the feeling that you are being treated unfairly?

6 Do you have the feeling that you are in an unfamiliar situation and don’t know what to do?

7 Doing the things you do every day is… a source of deep pleasure and satisfaction vs… a source ofpain and boredom

8 Do you have very mixed-up feelings and ideas?

9 Does it happen that you have feelings inside you would rather not feel’?

10 Many people, even those with a strong character, sometimes feel like sad sacks (losers) incertain situations. How often have you felt this way in the past?

11 When something happened, have you generally found that…you overestimated orunderestimated its importance… vs…. you saw things in the right proportion?

12 How often do you have the feeling that there is little meaning in the things you do in your daily life?

13 How often do you have feelings that you are not sure you can keep under control?

Items 2,6,8,9,11 - ComprehensibilityItems 3,5,10,13 - ManageabilityItems 1,4,7,12 - Meaningfulness

Validation of the Orientation to Life Questionnaire

123

Author's personal copy

The conventional overall test of model-fit is the Chi square (v2). Since Chi square

statistics are sensitive to sample size, it is recommended to use this measure along with

other fit measures. The Dv2 was measured and reported when comparing the model fit. If

the difference in fit (Dv2) is not significant, the hypothesis of equal parameter estimates

across multiple samples is considered to be tenable. The v2/df is also used as an indicator

of model fit in CFA where values B2.0 are indicative of a good model fit and values B3.0

are indicative of acceptable model fit (Byrne 2001). Besides, the following fit indices were

used; the RMSEA and the SRMS with values below 0.05 indicating good fit, whereas

values smaller than 0.08 is acceptable (Hu and Bentler 1998; Schermelleh-Engel et al.

2003). Further we used the CFI and the NNFI with acceptable fit at 0.95, and good fit at

0.97 and above, the NFI and the GFI with acceptable fit at 0.90, and good fit at 0.95 and

above. For the AGFI, acceptable fit was set to 0.85 and good fit at 0.90 (Hu and Bentler

1998; Schermelleh-Engel et al. 2003). By convention, the GFI and the NFI should be equal

to or greater than 0.90 for a model to be accepted. However, Brown (2006) suggested that a

cut-off value close to 0.95 for the CFI and 0.06 for RMSEA are needed before we can

conclude that there is a relatively good fit between the hypothesized model and the

observed data. All analyses were conducted using list wise deletion.

3 Results

3.1 Mean Scores, Correlations, and Internal Consistency of OLQ

The mean scores and standard deviations for the items and the three dimensions of

comprehensibility, manageability, and meaningfulness, as well as Cronbach’s alpha values

are reported for both samples in Table 2. The inter-item correlations and the correlations

between the three OLQ-dimensions were in the positive direction, showing medium to

strong estimates in both samples, especially item 2 and item 3 (r = 0.56/60) (Table 3). The

alpha-levels for the SOC dimensions indicated acceptable to good inter-item consistency

with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging between 0.61 and 0.70 for sample 1 and

between 0.64 and 0.70 for sample 2 (Table 2). Nevertheless, a substantial body of research

has indicated that Cronbach’s alpha cannot be generally relied on as an estimator of

reliability (Raykov 2001). Therefore, the formula by Hair et al. (2010) was used to estimate

the composite reliability (qc) showing acceptable to good values (0.60–0.70) (Table 5).

3.2 Confirmatory Factor-Analysis (CFA)—Factorial Validity of the OLQ

3.2.1 Model-1: The One-Factor Model (Sample 1)

The one-factor solution (Model-1) of the 13 item OLQ-scale was tested by means of CFA,

showing significant estimates (p \ 0.05). Table 4 shows the goodness-of-fit statistics for

the different models tested. As can be seen, the one-factor model did not show an

acceptable fit in reference to the Satorra-Bentler v2-value 452.12 (df = 65), (v2/

df = 6.96), (p value \ 0.001). Except from the v2 displaying a very high value, the other

fit indices indicated fairly good model fit with the present data. Nevertheless, several

significant residuals C ±1.96 and high modification indices (MI) indicated misspecifica-

tions of the model.

U. K. Moksnes, G. Haugan

123

Author's personal copy

3.2.2 Model-2: The Three-Factor Model (Sample 1)

Antonovsky’s theory highlights that SOC comprises three highly correlated dimensions

(Antonovsky 1979). Accordingly, a three-factor model (Model-2 in Table 4) was tested

showing an improved fit compared to the one-factor model. The Satorra-Bentler v2-value

was high (326.92), p value\0.011, v2/df = 5.27. However, the fit indices indicated a good

fit with the present data. A scrutiny of the residuals and the MIs revealed a standardized

residual = 12.83 and a MI = 236.83 between item 2 (‘‘Has it happened in the past that you

were surprised by the behaviour of people whom you thought you knew well?’’) and item 3

(‘‘Has it happened that people whom you counted on disappointed you?’’). It is theoreti-

cally plausible that being surprised and disappointed by someone’s behaviour might share

residual variance. Accordingly, allowing a correlated error term between item 2 and item 3

seemed reasonable. Thus, a nested version of Model-2 including the correlated errors

between item 2 and item 3 was estimated and named Model-2A; this model showed an

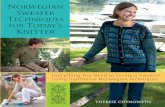

excellent fit with the data (see Table 4; Fig. 1). Table 5 lists the standardized estimates,

standard deviations, t values, and squared multiple correlations (R2) of Model-2A. All

factor loadings were significant and the R2 values ranged between 0.13 and 0.51. The

three-factor structure’s equivalent second-order was also tested as a conceptual possibility,

which indicated identical model fit as the first-order factor model.

Table 6 presents the differences in Satorra-Bentler-scaled v2. For the model to be

significantly better, the change in v2-value should exceed the critical value belonging to the

difference in degrees of freedom. The present results confirmed a significant difference in

v2-value for Model-2 versus Model-1 (125.2) and for Model-2A versus Model-2 (177.26);

Table 2 Means (M), standard deviations (SD) and Cronbach’s alpha, for OLQ items and the threedimensions meaningfulness, comprehensibility and manageability in sample 1 and sample 2

OLQ-13 Sample 1 (n = 1,183) Sample 2 (n = 1,168)

Mean (SD) Cronbach’s a Mean (SD) Cronbach’s a

Item 1 4.99 (1.56) 4.78 (1.64)

Item 2 4.41 (1.48) 3.97 (1.62)

Item 3 4.55 (1.55) 4.19 (1.68)

Item 4 5.36 (1.51) 5.12 (1.69)

Item 5 4.83 (1.68) 4.85 (1.79)

Item 6 4.70 (1.55) 4.55 (1.62)

Item 7 5.78 (1.30) 5.39 (1.52)

Item 8 4.86 (1.63) 4.45 (1.71)

Item 9 4.54 (1.81) 4.19 (1.84)

Item 10 5.14 (1.45) 4.53 (1.60)

Item 11 4.52 (1.32) 4.38 (1.38)

Item 12 4.61 (1.64) 4.50 (1.65)

Item 13 5.01 (1.70) 4.58 (1.72)

Meaningfulness (4 items) 20.63 (4.28) 0.66 19.72 (4.54) 0.63

Comprehensibility (5 items) 22.85 (5.34) 0.70 21.52 (5.53) 0.70

Manageability (4 items) 19.49 (4.45) 0.64 18.12 (4.59) 0.61

Total scale 62.97 (11.92) 0.84 59.19 (12.47) 0.84

Validation of the Orientation to Life Questionnaire

123

Author's personal copy

Ta

ble

3C

orr

elat

ion

sb

etw

een

the

item

sin

OL

Q1

3

OL

Q1

OL

Q2

OL

Q3

OL

Q4

OL

Q5

OL

Q6

OL

Q7

OL

Q8

OL

Q9

OL

Q1

0O

LQ

11

OL

Q1

2O

LQ

13

ME

CO

MA

OL

Q1

–0

.21

**

0.2

2*

*0

.14

**

0.1

7*

*0

.13*

*0

.26*

*0

.17*

*0

.12*

*0

.16*

*0

.10*

*0

.23

**

0.1

5*

*0

.60

**

0.2

5*

*0

.22

**

OL

Q2

0.1

8*

*–

0.6

0*

*0

.02

0.1

4*

*0

.18*

*0

.11*

*0

.25*

*0

.24*

*0

.21

-1

4*

*0

.21

**

0.2

5*

*0

.20

**

0.4

4*

*0

.52

**

OL

Q3

0.1

7*

*0

.56

**

–0

.13

**

0.2

2*

*0

.21*

*0

.20*

*0

.27*

*0

.28*

*0

.26*

*0

.14*

*0

.25

**

0.2

8*

*0

.28

**

0.6

5*

*0

.43

**

OL

Q4

0.2

5*

*0

.18

**

0.2

4*

*–

0.3

3*

*0

.29*

*0

.36*

*0

.36*

*0

.30*

*0

.26*

*0

.21*

*0

.41

**

0.3

3*

*0

.70

**

0.3

9*

*0

.36

**

OL

Q5

0.1

8*

*0

.22

**

0.2

6*

*0

.36

**

–0

.53*

*0

.26*

*0

.38*

*0

.37*

*0

.27*

*0

.24*

*0

.41

**

0.3

3*

*0

.43

**

0.6

9*

*0

.49

**

OL

Q6

0.1

3*

*0

.24

**

0.2

5*

*0

.27

**

0.3

5*

*–

0.2

6*

*0

.43*

*0

.42*

*0

.23*

*0

.32*

*0

.42

**

0.3

5*

*0

.40

**

0.4

9*

*0

.69

**

OL

Q7

0.1

9*

*0

.17

**

0.2

2*

*0

.40

**

0.2

2*

*0

.23*

*–

0.2

5*

*0

.15*

*0

.39*

*0

.13*

*0

.34

**

0.2

0*

*0

.69

**

0.3

8*

*0

.26

**

OL

Q8

0.1

8*

*0

.28

**

0.2

8*

*0

.35

**

0.3

0*

*0

.37*

*0

.32*

*–

0.5

5*

*0

.29*

*0

.32*

*0

.47

**

0.5

1*

*0

.46

**

0.5

3*

*0

.77

**

OL

Q9

0.1

5*

*0

.31

**

0.3

4*

*0

.32

**

0.3

4*

*0

.39*

*0

.31*

*0

.53*

*–

0.3

1*

*0

.29*

*0

.44

**

0.5

7*

*0

.37

**

0.5

6*

*0

.76

**

OL

Q1

00

.13

**

0.2

4*

*0

.29

**

0.3

4*

*0

.30*

*0

.32*

*0

.32*

*0

.39*

*0

.38*

*–

0.1

4*

*0

.28

**

0.2

7*

*0

.38

**

0.6

5*

*0

.35

**

OL

Q1

10

.22

**

0.1

6*

*0

.19

**

0.2

6*

*0

.23*

*0

.31*

*0

.18*

*0

.28*

*0

.22*

*0

.20*

*–

0.3

6*

*0

.31

**

0.3

0*

*0

.32

**

0.5

7*

*

OL

Q1

20

.28

**

0.2

6*

*0

.26

**

0.4

6*

*0

.35*

*0

.30*

*0

.36*

*0

.32*

*0

.35*

*0

.31*

*0

.28*

*–

0.4

6*

*0

.72

**

0.5

1*

*0

.55

**

OL

Q1

30

.15

**

0.2

7*

*0

.31

**

0.3

10

.32*

*0

.33*

*0

.28*

*0

.48*

*0

.51*

*0

.36*

*0

.28*

*0

.38

**

–0

.42

**

0.7

0*

*0

.60

**

Mea

nin

gfu

lnes

sM

E(4

item

s)0

.62

**

0.2

8*

*0

.31

**

0.7

4*

*0

.38*

*0

.32*

*0

.65*

*0

.41*

*0

.39*

*0

.38*

*0

.33*

*0

.76

**

0.3

9*

*–

0.5

6*

*0

.51

**

Co

mpre

hen

sib

ilit

yC

O(5

item

s)0

.23

**

0.4

6*

*0

.66

**

0.4

5*

*0

.69*

*0

.45*

*0

.37*

*0

.52*

*0

.57*

*0

.67*

*0

.33*

*0

.48

**

0.7

3*

*0

.53

**

–0

.70

**

Man

agea

bil

ity

MA

(4it

ems)

0.2

5*

*0

.57

**

0.4

7*

*0

.40

**

0.4

2*

*0

.68*

*0

.35*

*0

.74*

*0

.76*

*0

.44*

*0

.55*

*0

.44

**

0.5

5*

*0

.51

**

0.6

8*

*–

Corr

elat

ions

for

sam

ple

1ar

eab

ove

the

dia

gonal

and

corr

elat

ions

for

sam

ple

2ar

ebel

ow

the

dia

gonal

**

pB

0.0

1

U. K. Moksnes, G. Haugan

123

Author's personal copy

Ta

ble

4G

oo

dnes

s-o

f-fi

tm

easu

res

for

Mo

del

-1,

Mo

del

-2an

dM

od

el-2

A

Fit

mea

sure

Mo

del

-1N

=1

,183

1-f

acto

rR

ML

13

var

iab

les

Sa

mp

le1

Mo

del

-1N

=1

,168

1-f

acto

rR

ML

13

var

iab

les

Sa

mp

le2

Mo

del

-2N

=1

,183

3-f

acto

rR

ML

13

var

iab

les

Sa

mp

le1

Mo

del

-2N

=1

,168

3-f

acto

rR

ML

13

var

iab

les

Sa

mp

le2

Mo

del

-2A

N=

1,1

83

3-f

acto

rR

ML

13

var

iab

les

Sa

mp

le1

Mo

del

-2A

N=

1,0

68

3-f

acto

rR

ML

13

var

iab

les

Sa

mp

le2

v2(S

atorr

a-B

entl

er)

452.1

2790.3

4326.9

2716.1

7149.6

6398.5

8

p-v

alue

\0

.00

1\

0.0

01

\0

.00

1\

0.0

01

\0

.001

\0

.001

Df

65

65

62

62

61

61

v2/D

f6

.96

12

.16

5.2

71

1.5

52

.45

6.5

3

RM

SE

A0

.074

0.0

98

0.0

62

0.9

50

.036

0.0

72

pv

alue

(clo

sefi

tte

st)

\0

.00

01

\0

.00

01

\0

.00

01

\0

.00

01

1.0

00

0.0

00

1

SR

MR

0.0

54

0.0

74

0.0

47

0.0

71

0.0

31

0.0

54

NF

I0

.94

0.9

10

.96

0.9

10

.98

0.9

5

NN

FI

0.9

40

.89

0.9

60

.90

0.9

80

.95

CF

I0

.95

0.9

10

.97

0.9

20

.99

0.9

6

GF

I0

.92

0.8

80

.94

0.8

90

.97

0.9

3

AG

FI

0.8

90

.84

0.9

20

.88

0.9

60

.90

RM

SE

Aro

ot

mea

nsq

uar

eer

ror

of

app

roxim

atio

n,

SR

MS

stan

dar

diz

edro

ot

mea

nsq

uar

ere

sid

ual

,N

FI

no

rmed

fit

ind

ex,

NN

FI

no

n-n

orm

edfi

tin

dex

,C

FI

the

com

par

ativ

efi

tin

dex

,G

FI

go

od

nes

s-o

f-fi

tin

dex

,A

GF

Iad

just

edg

oo

dn

ess-

of-

fit

ind

ex,

RM

Lro

bu

stm

axim

um

lik

elih

oo

d,

Df

deg

rees

of

free

dom

Validation of the Orientation to Life Questionnaire

123

Author's personal copy

all significant at the 0.001 % level. Thus, the null-hypotheses of equal fit for the models

were rejected indicating a significant better v2 for the three-factor-model than for the one-

factor-model.

3.2.3 Evaluation of the Models in Sample 2

As a next step we investigated Model-1, Model-2 and Model-2A in sample 2. These

analyses revealed the same pattern as disclosed by sample 1: the v2 and the fit indices

showed the best fit for Model-2A, Model-2 and Model-1, respectively. Thus, sample 2

supported the findings from sample 1 and the model fit of the three models tested are

presented in Table 4. However, items 1, 2, 3, 10, and 11 displayed low factor loadings and

R2 (Table 5), and a great amount of error variance and very high MIs between several pairs

of items were disclosed.

4 Discussion

The aim of the present study was to extend the understanding of the factorial validity and

reliability of the 13 item version of the OLQ in adolescents, using two samples with

Norwegian adolescents 13–18 years. The psychometric properties of the 13 item OLQ has

been scarcely investigated in adolescents and to the author’s knowledge, no validations

have been made on Norwegian adolescents. Based on theory of the dimensionality of SOC

and previous psychometric validations of the instrument (Feldt et al. 2007; Gana and

Garnier 2001; Hittner 2007; Naaldenberg et al. 2011), a one-factor model and a three-

factor model were evaluated.

Fig. 1 Model-2A, sample 1: three-factor-model of the orientation to life questionnaire (OLQ)

U. K. Moksnes, G. Haugan

123

Author's personal copy

Regarding dimensionality of the OLQ, the results of the CFA showed that the same

pattern of misspecifications was evident for the 13 item one-factor model (Model 1) in both

samples. An improved model fit was found for the three-factor model (Model 2), although

Table 5 Model-2A: Three-factor model including correlated errors between item 2 and item 3, t-values arebased on sample 1

Items Parameter Lisrel estimate t-value (sample 1) R2

Meaningfulness

OLQ 1 kx1,1 0.37 (0.30) 9.37*** 0.13 (0.09)

OLQ 4 kx4,1 0.68 (0.57) 19.55*** 0.46 (0.33)

OLQ 7 kx7,1 0.56 (0.47) 14.64*** 0.32 (0.22)

OLQ 12 kx12,1 0.68 (0.75) 21.65*** 0.47 (0.57)

Comprehensibility

OLQ 2 kx2,2 0.42 (0.32) 13.16*** 0.18 (0.10)

OLQ 6 kx6,2 0.56 (0.63) 18.06*** 0.31 (0.40)

OLQ 8 kx5,2 0.70 (0.73) 26.47*** 0.49 (0.53)

OLQ 9 kx9,2 0.72 (0.71) 29.18*** 0.51 (0.51)

OLQ 11 kx7,2 0.41 (0.45) 11.28*** 0.17 (0.21)

Manageability

OLQ 3 kx3,3 0.47 (0.38) 14.93*** 0.22 (0.15)

OLQ 5 kx5,3 0.54 (0.58) 18.19*** 0.29 (0.33)

OLQ10 kx10,3 0.57 (0.41) 17.86*** 0.32 (0.17)

OLQ 13 kx13,3 0.66 (0.67) 23.15*** 0.44 (0.45)

qc Meaningf. 4 items qc 0.67 (0.60) – –

qc Compreh. 5 items qc 0.70 (0.70) – –

qc Manageab.4 items qc 0.65 (0.60) – –

Standardized factor loadings, squared multiple correlations (R2) and Composite reliability

(qc ¼P

k2

Pkð Þ2þ

Phð Þ

� �based on sample 1 (sample 2)

*** p \ 0.001

Table 6 Statistical comparison and v2 difference test of Model-1, Model-2 and Model-2A based in sample1

v2 Dfd Diff v2 Model-1 Diff v2 Model-2 Diff v2 Model-2A

Models Sample 1

Model-1a 452.12 65 –

Model-2b 326.92 62 125.2*** –

Model-2Ac 149.66 61 302.46*** 177.26*** –

*** p \ 0.001a Model-1: The 1-factor-modelb Model-2: The 3-factor-modelc Model-2A: 3-factor-model including correlated errors between the items 2 and 3d Df Degrees of freedom

Validation of the Orientation to Life Questionnaire

123

Author's personal copy

the Chi square value was still high. Overall, the presence of misspecifications was evident

in reference to correlated error variances between items 2 and 3, indicating that they share

common sources of variance other than to their respective subscales. Thus, a nested version

of the three-factor model was evaluated, allowing a correlated error terms between item 2

and item 3, which resulted in good model fit in both samples (Model 2A). The three-factor

structure’s equivalent second-order factor model was also tested as a conceptual possi-

bility, which indicated similar model fit as the first-order factor model. The CFA also

showed that the components of comprehensibility, manageability and meaningfulness were

highly interrelated. Nevertheless, the Chi square difference test showed that the three-

factor structure was statistically superior the one-factor structure.

The decision of allowing correlated error variances between item 2 and item 3 was

based on statistical considerations, indicated by large Chi square values and residual

variances. It is a well-known problem that Chi square statistics are sensitive to sample size.

That is, as the sample size increases, the chances of rejecting a true model increase (Brown

2006; Byrne 2001). Meanwhile, correlated error variances between items should be con-

ducted only if it makes theoretically sense to do so. The presence of misspecifications was

evident in reference to correlated error variances between item 2: ‘‘Has it happened in the

past that you were surprised by the behavior of people whom you thought you knew well?’’

and item 3: ‘‘Has it happened that people whom you counted on disappointed you?.’’ The

items represent manifestations of an underlying interpersonal unpredictability, in reference

to being surprised and disappointed by people who you know well and account on. If you

know someone well it is also likely that you count on this person and that you will be both

surprised and disappointed if such a person let you down. Thus, allowing correlated errors

for item 2 and item 3 seemed theoretically meaningful. These findings are in line with other

studies which have concluded that especially item 2 and item 3 in the OLQ contributed to

model misspecifications in reference to semantic overlap in the items (Ding et al. 2011;

Hittner 2007; Naaldenberg et al. 2011; Richardson et al. 2007).

According to Antonovsky’s theory (1987), the structure of the SOC concept is one-

dimensional (a global orientation of life) consisting of three components of comprehen-

sibility, manageability and meaningfulness, all three closely correlated and considered as a

whole. A previous review (Eriksson and Lindstrom 2005) summing research on the OLQ

based on different adult populations concludes with that the OLQ dimensionality is

unclear, seeming to be multidimensional rather than one-dimensional. The results of the

present study are in line with Anotnovsky’s theory and previous validations of the 13 item

OLQ, supporting a three factor structure of the instrument, with highly correlated com-

ponents (Ding et al. 2011; Feldt et al. 2007; Richardson et al. 2007). However, the present

results contradict the findings of the study based on Swedish adolescents where a one-

factor structure was supported (Hagquist and Andrich 2004).

All three models presented significant factor loadings in both samples. For the three-

factor model the standardized factor loadings ranged between 0.37 (item 1) and 0.72 (item

9) in sample 1 and between 0.30 (item 1) and 0.73 (item 8) in sample 2. When looking at

the three-factor model with correlated error variances (Model-2A), item 1: ‘‘Do you have

the feeling that you really don’t care what is going on around you?’’, item 2: ‘‘Has it

happened in the past that you were surprised by the behaviour of people whom you thought

you knew well?’’ and item 11: ‘‘When something happened, have you generally found

that…you overestimated or underestimated its importance…versus…you saw things in the

right proportion?’’, exposed R2-values of 0.13, 0.18 and 0.17, respectively. The same

pattern appeared in sample 2, with R2-values of 0.09, 0.10 and 0.21, respectively. Hence,

these items did not explain a noteworthy amount of variance in SOC, indicating low

U. K. Moksnes, G. Haugan

123

Author's personal copy

reliability. Furthermore, item 3 (‘‘Has it happened that people whom you accounted on

disappointed you?’’) and item 10 (‘‘Many people, even those with a strong character,

sometimes feel like sad sacks (losers) in certain situations. How often have you felt this

way in the past?’’) also displayed low factor loadings and R2-values of 0.22/0.15 and 0.32/

0.17, in sample 1/sample 2, respectively. Summarized, the items 1, 2, 3, 10 and 11 indi-

cated low reliability in the two samples investigated.

The low factor loading of item 1 is in accordance with the findings in the study of Ding

et al. (2011) indicating that this item does not contribute to the variance of the mean-

ingfulness dimension in the two adolescent samples investigated. There might be multiple

reasons for this, but caring about what is going around in one’s close environment,

especially with friends during school and leisure time is one of the most important focuses

in adolescents’ lives and something that is meaningful for most adolescents. Therefore, the

item might not be perceived as relevant by the adolescent group.

Item 10 focuses on the feeling of being a loser in certain situations. Being a loser might

be perceived as having an insulting character and give adolescents an association of being

victimized and stigmatized. It is therefore possible that it is difficult for adolescents to

relate to the semantic meaning and wording of this item and respond to it in a reliable way.

Item 11 involves an evaluation of either over- or underestimating a situation at one end,

and reacting in the right proportion at the other end. This item requires a general reflection

and comprehension of a magnitude of situations that may happen in adolescents’ lives in a

retrospective perspective. It is possible that this item has low reliability because the

semantic meaning in reference to ‘‘overestimate’’ and ‘‘underestimate a situation’’ is dif-

fuse and complex to comprehend and therefore difficult to evaluate by adolescents.

The presence of low factor loadings was also evident for item 2 and item 3. As

described previously, it is possible that these items presented low factor loadings and

explained variance because it is difficult to differentiate the cognitive and emotional

aspects of being surprised and disappointed by people adolescents know well and count on.

It is also possible that it would be easier to reflect around such situations if the word

‘‘people’’ was more concrete, allowing adolescents to reflect around situations related to

e.g. teachers, parents or peers.

Moreover, evaluation of the items in the OLQ requires that adolescents are at a level of

cognitive development where they are able to reflect and understand the semantic meaning

of the items. The age range of the adolescent samples was 13–18 years and it may be

especially challenging for the youngest ones to reflect over abstract concepts like ‘‘over-or

underestimating situations in general’’, and ‘‘being disappointed’’ or ‘‘surprised by other

people’s behavior;’’ this may lead to over or under reporting (self-report bias) (Derdikman-

Eiron et al. 2011). Second, there is a challenge regarding the adolescents’ ability to reliably

evaluate and report on experiences and feelings as though self-reports require that ado-

lescents are at a level of cognitive development where they are able to reflect, understand

and differentiate abstract concepts. However, it should be acknowledged that all such data

might be more prone to bias due to the possible influence of social desirability factors

(Derdikman-Eiron et al. 2011). Another aspect in the discussion of interpretation of items

is the relevance of the content and the language which adolescents use, and the jargon they

choose to describe and evaluate their experiences. All these aspects have to be taken into

consideration when evaluating the face validity of the items and the ability of OLQ to

reliably measure SOC in the adolescent group. In reference to the low factor loadings and

R2-values found on some of the items in OLQ (item 1, 2, 3, 10 and 11) across the two

samples investigated, the semantic meaning of the items might be discussed with

Validation of the Orientation to Life Questionnaire

123

Author's personal copy

adolescents in gender and age balanced focus groups in order to evaluate the relevance,

wording and semantic meaning of the items.

Meanwhile, the high factor loadings of the remaining items and the good model fit of

the three-factor model with correlated residual variances between item 2 and item 3

indicate that most of the variance in SOC is explained by the items included in the 13-item

OLQ; this gives support to the reliability of the instrument as well as Antonovsky’s theory

(1987). Moreover, the present results demonstrated that the 13 item three factor model had

a good internal consistency, where composite reliability ranged from 0.65 to 0.70 for

sample 1 and from 0.60 to 0.70 for sample 2. The 13 item OLQ scale has been reported to

have internal consistency comparable to the 29 item version with Cronbach’s alpha ranging

between 0.70 and 0.92 in adult and elderly samples (Eriksson and Lindstrom 2005; Hittner

2007). Among adolescents, the internal consistency is less investigated, however, studies

have reported Cronbach’s alpha of 0.82 (Rivera et al. 2012) and 0.86 (Nielsen and Hansson

2007).

4.1 Limitations

A major strength of the present study is that it is based on two reasonably large sample

sizes with high response rates. Although the sample size was high, differences in sample

characteristics may have had impact on the results. The present results have tested model

data consistency by comparing measurement models and its assumptions to the present

data. However, we do not know if the assumptions for ‘‘model reality consistency’’ are

achieved, that is, whether the model found to fit our data mirrors real-world processes. A

good model fit does not mean we have obtained the ‘‘true’’ model. It is therefore possible

that there are other alternative models that fit the data equally well as the model found in

the present data sets, and that our model may be only one of many that match the data

(Bollen 1989). The present study have investigated the factorial validity and stability of the

instrument across two large samples, however, this is not tested statistically through multi-

group analysis; this analyze technique is recommended in future studies. All findings were

based on self-reports and are therefore subject to potential self-reporting bias, however, the

large sample size of the present study can partially protect against the influences of

potential random error related to self-reporting (Derdikman-Eiron et al. 2011).

5 Conclusion

The results of this study provide further evidence of the psychometric properties of the 13

item OLQ and contribute to an understanding of how the instrument may perform as a

measure of SOC across two Norwegian adolescent samples. The three-factor model with

correlated error parameters between item 2 and item 3 resulted in good fit in the two

samples investigated. Further, the good composite reliability of the dimensions indicates

high inter-correlations among the items, and that items are consistent in measuring the

underlying construct of SOC. However, more psychometric testing of the instrument is

required in reference to the modified factor structure found and that five items had low

factor loadings and R2. The items in the OLQ instrument might be investigated e.g. through

gender and age balanced focus group discussion with adolescents to clarify the relevance,

wording and semantic meaning of the items. The OLQ should also be further validated on

adolescents, as though few studies have tested the psychometric properties of the OLQ on

this population. Additional cross-cultural research exploring the psychometric properties of

U. K. Moksnes, G. Haugan

123

Author's personal copy

OLQ is also necessary in order to assess external validity of the reported findings. On the

basis of evidence reported in this paper, the 13 item OLQ does appear to have potential as

an instrument assessing SOC in the Norwegian adolescent population. Nevertheless, five

items presented low reliability and should be further developed in order to comprehen-

sively assess SOC among teenagers.

References

Antonovsky, A. (1979). Health, stress and coping. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.Antonovsky, A. (1987). Unraveling the mystery of health. How people manage stress and stay well. San

Fransisco: Jossey-Bass.Antonovsky, A. (1993). The structure and properties of the sense of coherence scale. Social Science and

Medicine, 36, 969–981.Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of

Marketing Science, 16, 74–94.Bollen, K. A. (1989). Structural equations with latent variables. New York: John Wiley & Sons.Braun- Lewensohn, O., & Sagy, S. (2010). Sense of coherence, hope and values among adolescents under

missile attacks: A longitudinal study. International Journal of Children’s Spirituality, 15, 247–260.Brown, T. A. (2006). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. London: The Guildford Press.Byrne, M.B. (2001). Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS. Basic concepts, applications, and pro-

gramming. USA: Taylor AND Francis Group.Derdikman-Eiron, R., Indredavik, M. S., Bratberg, G. H., Taraldsen, G., Bakken, I. J., & Colton, M. (2011).

Gender differences in subjective well-being, self-esteem and psychosocial functioning in adolescentssymptoms of anxiety and depression: Findings from the Nord-Trøndelag health study. ScandinavianJournal of Psychology, 52, 261–267.

Ding, Y., Bao, L., Xu, H., & Hallberg, I. R. (2011). Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of senseof coherence scale in women with cervical cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 21, 1205–1214.

Eriksson, M. (2007). Unravelling the mystery of salutogenesis. The evidence base of the salutogenicresearch as measured by Antonovsky’s Sense of Coherence Scale. (Research Report No. 1). Turku:Folkhalsan Research Centre, Health promotion research programme.

Eriksson, M., & Lindstrom, B. (2005). Validity of Antonovsky’s sense of coherence scale: A systematicreview. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 59, 460–466.

Eriksson, M., & Lindstrom, B. (2006). Antonovsky’s sense of coherence scale and the relation with health:A systematic review. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 60, 376–381.

Feldt, T., Lintula, H., Suominen, S., & Koskenuvo, M. (2007). Structural validity and temporal stability ofthe 13-item sense of coherence scale: Prospective evidence from the population-based HeSSup study.Quality of Life Research, 16, 483–493.

Gana, K., & Garnier, S. (2001). Latent structure of the sense of coherence scale in a french sample.Personality and Individual Differences, 31, 1079–1090.

Hagquist, C., & Andrich, D. (2004). Is the sense of coherence-instrument applicable on adolescents? Alatent trait analysis using Rasch-modelling. Personality and Individual Differences, 36, 955–968.

Hair, J., Black, W., Babin, B., & Anderson, R. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: Upper Saddle River:Prentice Hall.

Hittner, J. B. (2007). Factorial invariance of the 13-item sense of coherence scale across gender. Journal ofHealth Psychology, 12, 273–280.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. (1998). Fit Indices in covariance structure modelling: Sensitivity to underparametrizedmodel misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3, 424–453.

Lindstrom, B., & Eriksson, M. (2010). The Hitchhiker‘s guide to salutogenesis. Salutogenic pathways tohealth promotion. (Research Report No. 2) Helsinki: Folkhalsan Research Centre, Health promotionresearch programme.

Moksnes, U. K., Lohre, A., & Espnes, G. A. (2012). The association between sense of coherence and lifesatisfaction in adolescents. Quality of Life Research, 22, 1331–1338.

Naaldenberg, J., Tobi, H., van den Esker, F., & Vaandrager, L. (2011). Psychometric properties of the OLQ-13 scale to measure Sense of Coherence in a community-dwelling older population. Health and Qualityof Life Outcomes, 9, 37–46.

Validation of the Orientation to Life Questionnaire

123

Author's personal copy

Neuner, B., Busch, M. A., Singer, S., Moons, P., Wellmann, J., Bauer, U., et al. (2011). Sense of Coherenceas a predictor of quality of life in adolescents with congenital heart defects: A register-based 1-yearfollow-up study. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 32, 316–327.

Nielsen, A. M., & Hansson, K. (2007). Associations between adolescents’ health, stress and sense ofcoherence. Stress and Health, 23, 331–341.

Nilsson, K. W., Leppert, J., Simonsson, B., & Starrin, B. (2010). Sense of coherence and psychological well-being: Improvements with age. Journal of Epidemiological and Community Health, 64, 347–352.

Oztekin, O., & Tezer, E. (2009). The role of sense of coherence and physical activity in positive andnegative affect of Turkish adolescents. Adolescence, 44, 421–431.

Raykov, T. (2001). Estimation of congeneric scale reliability using covariance structure analysis withnonlinear constraints. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 54, 315–323.

Richardson, C. G., Ratner, P. A., & Zumbo, B. D. (2007). A test of the age-based measurement invarianceand temporal stability of Antonovsky’s sense of coherence scale. Education and PsychologicalMeasurement, 67, 679–696.

Rivera, F., Garcia-Moya, I., Moreno, C., & Ramos, P. (2012). Developmental contexts and sense ofcoherence in adolescence: A systematic review. Journal of Health Psychology, 18, 800–812.

Schermelleh-Engel, K., Moosbrugger, H., & Muller, H. (2003). Evaluating the fit of structural equationmodels: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods of PsychologicalResearch, 8, 23–74.

Simonsson, B., Nilsson, K. W., Leppert, J., Vinod, K., & Diwan, V. K. (2008). Psychosomatic complaintsand sense of coherence among adolescents in a county in Sweden: A cross-sectional school survey.BioPsychoSocial Medicine, 2, 1–8.

U. K. Moksnes, G. Haugan

123

Author's personal copy