Translations of '-ly' adverbs of degree in an English-Spanish Parallel Corpus

Transcript of Translations of '-ly' adverbs of degree in an English-Spanish Parallel Corpus

This is a contribution from Target 20:2© 2008. John Benjamins Publishing Company

This electronic file may not be altered in any way.The author(s) of this article is/are permitted to use this PDF file to generate printed copies to be used by way of offprints, for their personal use only.Permission is granted by the publishers to post this file on a closed server which is accessible to members (students and staff) only of the author’s/s’ institute.For any other use of this material prior written permission should be obtained from the publishers or through the Copyright Clearance Center (for USA: www.copyright.com). Please contact [email protected] or consult our website: www.benjamins.com

Tables of Contents, abstracts and guidelines are available at www.benjamins.com

John Benjamins Publishing Company

Translations of ‘-ly’ adverbs of degree in an English-Spanish Parallel Corpus*

Noelia Ramón and Belén LabradorUniversity of León, Spain

This paper focuses on the translations of English -ly adverbs of degree into Span-ish. The English suffix -ly has been traditionally associated with the expression of manner. However, it also actualises other meanings, in particular degree. In Spanish, the formal equivalents of -ly adverbs are adverbs ending in -mente, but the latter occur less frequently and with different pragmatic nuances. Adverbs of degree can be translated into -mente adverbs but also into other resources such as non -mente adverbs, prepositional phrases, adjectives, etc. The aim is to establish a taxonomy of translation solutions extracted from a parallel corpus in order to reveal cross-linguistic correspondences useful in translator training and translation quality assessment.

Keywords: adverbs of degree, parallel corpus, translation, -ly suffix, -mente suffix, translation quality assessment

1. Introduction

This paper is an account of a corpus-based analysis of the translations from English into Spanish of some adverbs of degree. “Expressions of degree are conspicuous elements in human communication” (Paradis 1997: 9), and from a cross-linguistic perspective degree has recently raised much interest too (Klein 1998). As far as the language pair English-Spanish is concerned, the translation of grading expressions is particularly problematic. One of the typical resources for expressing degree in English is -ly adverbs, such as greatly, highly, extremely. There is a formally similar resource available in Spanish, in the form of -mente adverbs for expressing grading functions. However, there are other more frequent and idiomatic expressions of degree in Spanish, in particular other adverbs not ending in -mente, prepositional phrases (PPs), adjectival constructions, etc. (Hoye 1997).

Due to the formal similarity of cognate adverbs in -ly and -mente, there may be a tendency to use Spanish -mente adverbs for translating -ly forms. This overuse

Target 20:2 (2008), 275–296. doi 10.1075/target.20.2.05ramissn 0924–1884 / e-issn 1569–9986 © John Benjamins Publishing Company

© 2008. John Benjamins Publishing CompanyAll rights reserved

276 Noelia Ramón and Belén Labrador

is a case of ‘translationese’, i.e. a feature of translated language that can be attrib-uted to the interference of the source language. Bearing this in mind, this paper (a) studies a large number of -ly adverbs of degree in contemporary written English texts in order to describe their behaviour; (b) identifies the most frequent trans-lational options adopted in Spanish for translating those -ly adverbs of degree, and (c) compares the results from the translations with the behaviour of -mente adverbs in original Spanish. The empirical data for the study have been extracted from electronic corpora: on the one hand, a parallel corpus containing English original texts and their corresponding Spanish translations (P-ACTRES), and, on the other hand, a comparable corpus of original and translated Spanish. The main goal of this study is to employ corpus data to reveal the most important trends in the use of -ly and -mente degree adverbs. The results can be of use in areas such as translator training and translation quality assessment.

2. Theoretical background

Adverbs are peripheral sentence elements that show a wide range of semantic con-cepts and disparate syntactic distribution. They can be used to contribute a variety of circumstantial meanings, including place, manner, or degree. From a syntactic point of view, adverbs may carry out two main functions: modifier or adverbial, and both have been taken into account in this study. From a semantic perspective, “adverbs of degree describe the extent to which a characteristic holds” (Biber et al. 1999: 554). Degree can be considered a continuum, from negative to absolute, in-cluding various different positions along the scale. A broad semantic classification distinguishes between intensifiers and downtoners, depending on whether they express a degree greater or lesser than usual. Some authors distinguish further categories. For instance Bolinger (1972) puts forward the terms ‘booster’, ‘compro-miser’, ‘minimizer’ and ‘diminisher’ for the various degrees that may be expressed, and Klein (1998) discerns up to eight different degrees: ‘absolute’ (completely), ‘ap-proximative’ (nearly), ‘extremely high’ (extremely), ‘high’ (very), ‘moderate’ (rath-er), ‘minimal’ (somewhat, a bit), ‘quasinegative’ (hardly), and ‘negative’ (not).

As far as translation is concerned, transferring grading meanings from one lan-guage to another usually involves divergences due to differences in the way languag-es map functions onto grammatical form. In the case of the pair English-Spanish, different resources are available for the expression of degree, e.g. the suffix -ísimo (grandísimo) is commonly used by native speakers of Spanish to express a high de-gree but no formal equivalent exists in English. This paper focuses on the other direction, from English into Spanish, using a form (-ly adverbs) as a starting point to identify all the actual translations chosen to convey the grading meanings of these

© 2008. John Benjamins Publishing CompanyAll rights reserved

Translations of ‘-ly’ adverbs of degree in an English-Spanish Parallel Corpus 277

-ly adverbs. There is a formal equivalent of this resource in Spanish, the cognate -mente adverbs, but these two suffixes are pragmatically non-equivalent. First, -ly adverbs are unmarked with respect to register, and they are used with relative fre-quency by native speakers of English as they carry no particular connotation of for-mality. In addition the suffix -ly is so short that it does not produce excessively long words, thus enhancing their idiomaticity. In contrast, -mente adverbs are stylistically and pragmatically marked. Native speakers of Spanish tend to shun them because of their length (two syllables added to the root), which makes them cumbersome and, as a result, they carry a connotation of formality, they are basically used in writ-ten texts and they are less idiomatic. However, native speakers avoid some -mente adverbs more than others on a lexical basis, e.g. probablemente is used 35 times as often as amargamente and has a much wider range of collocates.1 For most adverbial meanings, native speakers of Spanish prefer other resources, in particular other ad-verbs, PPs (prepositional phrases) and adjectival constructions (Hoye 1997).

In spite of their pragmatic non-equivalence, and due to their formal similarity, our working hypothesis is that there may be a tendency to translate -ly adverbs by their cognates in Spanish, irrespective of their pragmatic function in the target language. An overuse of a particular language feature in translated texts is known in the literature as ‘translationese’ (Baker 1998, 2004; Laviosa 1998; Mauranen 2000, 2004, Tirkkonen-Condit 2002, 2004) and recent research has brought the question into translation quality research. An overuse or underuse of -mente ad-verbs expressing degree in Spanish translations when compared to original Span-ish texts may contribute to the assessment of the quality of translations. For this purpose, the results of the analysis of the parallel corpus will be compared with the frequency of use of those same -mente adverbs in a large reference corpus of con-temporary Spanish: CREA (Corpus de Referencia del Español Actual). A higher or lower number of -mente adverbs in the Spanish translations in P-ACTRES will illustrate a deviation typical of translated language.

3. Methods

3.1 Interlinguistic stage

3.1.1 Description of the parallel corpusThe working procedure followed in this paper is the one developed by the AC-TRES2 research group at the University of León (Spain). The ACTRES Project is a long-term translation-oriented research endeavour that has been running for several years now. This project is aimed at exploiting cross-linguistic analyses be-tween English and Spanish in order to investigate translated language and find

© 2008. John Benjamins Publishing CompanyAll rights reserved

278 Noelia Ramón and Belén Labrador

applications mainly in the field of translation practice, translator training and translation quality assessment.

Numerous studies have been devoted to the exploitation of parallel and other types of corpora with translation-oriented purposes (Baker 2004, Olohan 2004). A parallel corpus has been compiled and aligned containing original English texts and their corresponding Spanish translations. This translation corpus includes written material from a variety of different registers (fiction, non-fiction, press and miscellanea) published in English since 2000, thus representing the contem-porary stage of the English language. The texts included vary in length depend-ing on the register. In the case of books, the corpus contains fragments averaging some 15,000 words. The exact length varies depending on the text, since chapter divisions were considered so that all fragments were complete texts. In the case of newspaper and magazine articles the texts included are complete units of around 1,000 words each for the former and around 3,000 words each for the latter. To-gether with the corresponding translations into peninsular Spanish, these texts form what is known as the P-ACTRES corpus (Parallel ACTRES). The P-ACTRES corpus is still under construction and is intended to reach several million words. The corpus management tools used have been developed and constantly refined in Norway for the English-Norwegian Parallel corpus Project (Hofland and Johans-son 1998).

For this analysis, we have drawn data from the sections on books only, both fiction and non-fiction. The texts included in these sections have been aligned at sentence level and the English half has also been tagged for parts of speech (POS), thus allowing for more precise queries, e.g., words ending in -ly and tagged as adverbs. This type of query discards unwanted instances of other parts of speech ending in -ly, e.g., July, fly, etc. Table 1 shows the composition and the distribution of the number of words per language in each subsection of the corpus used for the present piece of research.

Table 1. Composition of the parallel corpus used for the analysisEnglish Spanish Total

B. Fiction 295,207 302,818 598,025B. non-Fiction 186,994 207,092 394,086Total words 482,201 509,910 992,111

3.1.2 Data selection in the parallel corpusThe first step in the analysis consisted in selecting a list of formal entries, -ly ad-verbs, obtained from a smaller sample corpus of the larger ACTRES parallel cor-pus. In a previous study of -ly adverbs (Rabadán et al. 2006), all the occurrences of these adverbs in the sample corpus were classified according to their semantic

© 2008. John Benjamins Publishing CompanyAll rights reserved

Translations of ‘-ly’ adverbs of degree in an English-Spanish Parallel Corpus 279

function. Among the different functions found, one that was particularly outstand-ing in terms of frequency was degree. Table 2 shows the complete list of functions found for all -ly adverbs (477 tokens, 234 types) appearing in a nearly 40,000-word corpus of authentic contemporary English texts of the various registers included in the ACTRES corpus.

Manner was the most frequent semantic function of -ly adverbs in English, with 40% of the total. This was an expected result since this form has traditionally been associated with the expression of manner. However, more than half the oc-currences of -ly adverbs — the remaining 60% of cases — expressed other differ-ent meanings, and degree happened to be particularly frequent, at 23%. This high frequency of -ly adverbs of degree in English prompted the present study, which is on a much larger scale. The starting point was the series of 47 types identified as having a grading function in the study mentioned above.

All the instances of each adverb of degree were extracted and analyzed manu-ally. The analysis has provided a number of different results: (a) information of interest about collocational patterns in the case of certain -ly adverbs; (b) a list of the translational options; (c) cross-register differences established between fiction and non-fiction texts, and (d) translationese in the Spanish translations.

The total number of occurrences of -ly adverbs of degree analysed was 771. A number of cases had to be discarded for several reasons:

1. Some instances expressed functions other than degree, in particular, manner — 59 cases. Overlap between manner and degree is very common.

2. Some of the instances were part of a paragraph or chunk of text which was not actually translated — 3 cases.

3. Some other cases were part of a proper noun e.g., Nearly Headless Nick (a character in the Harry Potter books) and were therefore not considered for the study — 8 cases.

Table 2. Semantic functions of -ly adverbsSemantic category Number of cases PercentageManner 192 40.25%Degree 112 23.48%Epistemic 80 16.77%Time 42 8.8%Restriction 28 5.87%Linking 9 1.88%Point of view 6 1.25%Attitude 5 1.04%Style 3 0.62%TOTAL 477 99.96%

© 2008. John Benjamins Publishing CompanyAll rights reserved

280 Noelia Ramón and Belén Labrador

As a result, the final number of occurrences to be studied amounted to 701, all evenly distributed across the two registers. Appendix 1 shows the total number of instances studied of the 47 types selected arranged alphabetically. It also illustrates the distribution of the various adverbs across fiction and non-fiction texts.

3.1.3 Statistical analysisThis is a form-based study using as a starting point a list of 47 -ly adverbs that have previously been identified as having a grading function (Rabadán et al. 2006). De-gree is a continuum and the cline ranges from negative degree to absolute degree in the quality of the linguistic item that is being graded. Most -ly adverbs of degree from the P-ACTRES parallel corpus indicate amplification, as in example (1), but there are also cases of adverbs indicating attenuation, as in example (2):

(1) We all agreed it had been extremely droll.

(2) Appropriate, he thought, barely able to contain his excitement.

All the concordances of these -ly adverbs are studied together with their corre-sponding translations. The results constitute the list of translational options avail-able in Spanish and some relevant intralinguistic features of the use of these English adverbs have been found too. In addition, the comparison between original and translated Spanish has provided data for identifying translationese. These cross-linguistic data are useful for Spanish students of English as a foreign language and also for practitioners of translation from English into Spanish, both trainees and professionals.

3.2 Spanish intralinguistic stage: Description of the comparable corpus

A second working procedure employed in this paper makes use of data from a Spanish comparable corpus in order to compare the use of -mente adverbs in orig-inal and in translated texts. For this purpose the whole of P-ACTRES corpus will be employed as a sample of translated Spanish; the comparable sample of original Spanish will be provided by a large reference corpus of this language, CREA (Cor-pus de Referencia del Español Actual) sponsored by the Royal Academy for the Spanish language. In CREA a subcorpus had to be selected to make it comparable to the texts in P-ACTRES in terms of registers, time and geographic variety (Pen-insular Spanish).

The two corpora differ in size: the Spanish translations in P-ACTRES include 674,040 words and the corresponding subsection of original Spanish in CREA comprises 56,448,069 words. The total number of cases per million words will be calculated in each language to make the figures comparable. In addition, the

© 2008. John Benjamins Publishing CompanyAll rights reserved

Translations of ‘-ly’ adverbs of degree in an English-Spanish Parallel Corpus 281

chi-square test for statistical significance will be used (p-value<0.05) to determine the relevance of the differences between the frequency rates in original versus translated Spanish.

4. Results

4.1 Intralinguistic analysis: Lexico-grammatical regularities in English

The first step in our analysis focused on the study of the individual lexical items in English, i.e. the list of types of ly-adverbs of degree shown in Appendix 1. Some peculiar features were observed with respect to the syntagmatic relationships that affect certain -ly adverbs of degree. In this section we will comment on the most significant collocational trends and semantic prosodies of a few of the adverbs selected: partly, closely, deeply and virtually.

Firstly, the -ly adverb of degree partly was found to occur in 50% of cases preceding the causal conjunction because, thus indicating that this particular ad-verb has a strong link with the expression of causal meanings. Curiously enough, virtually all the occurrences of the string partly because appeared in the fiction subcorpus, which suggests a preference for usage in a particular register. In addi-tion, partly often occurs in our corpus sample in correlative constructions: partly … partly or partly … mainly, as in example (3).

(3) When her father died, and her mother returned to London, Hermia stayed on, partly because of her job, but mainly because she was engaged to a Danish pilot, Arne Olufsen.

Secondly, the -ly adverb of degree closely was found to show several very inter-esting co-occurrence patterns. This adverb occurs very often with verbs of visual perception such as look, screen, read, watch, inspect, examine, peer, zoom and focus (37.5% of cases, as in example (4)), with a certain overlap of the meaning ‘manner’. This tendency has been observed equally frequently in both registers, fiction and non-fiction.

(4) The king inspected it closely then said, “Why, it is priceless”.

Closely was also found preceding a number of past participles that indicate a rela-tionship of connection: related, linked and connected (30% of cases, as in example (5)). Interestingly, all of these cases belonged to the non-fiction subcorpus.

(5) Given increasing evidence that red and green algae are closely related, a single symbiotic event may account for both groups.

© 2008. John Benjamins Publishing CompanyAll rights reserved

282 Noelia Ramón and Belén Labrador

Apart from the collocational issues mentioned above, another interesting aspect re-fers to the semantic prosody of certain adverbs of degree. Semantic prosody was first defined as “the consistent aura of meaning with which a form is imbued by its collo-cates” (Louw 1993: 157) and it is usually associated with positive or negative conno-tations. The -ly adverb of degree deeply showed a certain negative semantic prosody as many of the adjectives it precedes have a negative connotation (44% of cases in our corpus), most of which were found in the fiction subcorpus, as in example (6).

(6) The woman was deeply upset but she did what she could to get close to him.

The analysis of all the cases of the adverb virtually has revealed that on about half the occasions it co-occurred with universal quantifiers, such as all and every, near-ly all of them appearing in the non-fiction subcorpus (example 7). Another 32% of concordance lines were cases where the adverb preceded negative words, either quantifiers (nothing, no), or adjectives with negative prefixes (un-, im-) (example 8). This tendency of co-occurrence with the two extremes of the scale — univer-sal or negative quantity — characterises virtually as an approximative adverb of degree expressing “that the range of the scale which applies is very close to this end-point” (Klein 1998: 21).

(7) Though guerrillas operated in virtually all mountain areas, especially in the north and in southern Aragon, the Catalan guerrillas, who were almost wholly anarchist, unlike the others, were of no military significance.

(8) The extra surveillance wiring in the walls made it virtually impossible to get a carrier unless you stepped out into the hall.

These lexico-grammatical features specific to each -ly adverb of degree have impli-cations in FLT as well as in the field of translation.

4.2 Interlinguistic analysis: From English into Spanish

4.2.1 The translation of -ly adverbs of degreeThe analysis of the data extracted from the parallel corpus provided a list of au-thentic translational options of the 701 instances of -ly adverbs of degree and these options were subsequently grouped according to lexical, syntactic, and/or semantic categories. The labels used are loosely based on the general classification put forward by Vinay and Darbelnet (1958) including transposition into different grammatical parts of speech (PPs, adjectives, nouns, verbs and determiners) and modulation; modulation is a type of oblique translation that refers to instances where the adverbial function is not clearly expressed by a single element or phrase but spread over several lexical units in the target language with a change in the point of view.

© 2008. John Benjamins Publishing CompanyAll rights reserved

Translations of ‘-ly’ adverbs of degree in an English-Spanish Parallel Corpus 283

The results show that the most frequent translational option for -ly adverbs of degree were -mente adverbs in Spanish, which is not surprising, since this is a for-mal resource available in the Spanish language for expressing adverbial meanings. In general, there are cognate -mente adverbs for most English -ly adverbs, e.g. ab-solutely — absolutamente. Sometimes, there seem to be strong links between one particular -ly adverb and a prototypical equivalent in the form of a -mente adverb, even if it is not a cognate, e.g. the English adverb slightly is translated as a -mente adverb 11 times in the corpus, 10 times as ligeramente, and once as levemente. The analysis has revealed that there is not a one-to-one correspondence between pairs of cognates, but that non-cognate -mente adverbs are sometimes used for particular -ly adverbs, even when cognates are available in the target language, i.e. in example 9 absolutely has not been translated into absolutamente but into estrictamente:

(9) She said no more than was absolutely necessary to say to a stranger asking questions, but she was not unfriendly.

No dijo nada más que lo estrictamente necesario para satisfacer la curiosidad de una extraña, pero se mostró cordial.

On the one hand, each -ly form may be translated into different -mente adverbs with related meanings: e.g., completely has been translated into completamente (13 occurrences), but also into totalmente (8) and absolutamente (3). On the other hand, some -mente adverbs seem to be particularly frequent in Spanish and are used for the translation of more than one -ly adverb, e.g. ampliamente is used as the equivalent of widely (10), largely (1), thoroughly (1) and greatly (1); totalmente is used as the equivalent of entirely (10), completely (8), wholly (3) and absolutely (1) and completamente is used for translating completely (13), entirely (8), thor-oughly (3), wholly (2) and extremely (1). This last trend is much stronger, since

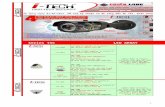

33.38

24.67

13.26 11.557.98

3.99 3.561.14 0.42

05

10152025303540

menteadvPP

modulationomissionadj

NPvdet

Figure 1. Translational options of -ly adverbs meaning degree

© 2008. John Benjamins Publishing CompanyAll rights reserved

284 Noelia Ramón and Belén Labrador

there are fewer commonly used -mente adverbs in Spanish and each one must therefore cover more meanings. This suggests that there is a greater variety of -ly adverbs than of -mente adverbs.

One particularly problematic subtype of -ly adverbs for native speakers of Spanish studying translation are those derived from adjectives indicating a nega-tive quality like awfully, badly, horribly, poorly, which all indicate either high or low degree apart from retaining the negative evaluation implied by the corresponding adjectives. Some collocational patterns identified are: ‘badly injured/wounded/bat-tered’; ‘awfully busy/tactless/clever’, ‘horribly vivid’, ‘poorly + Past Participle’: ‘poor-ly documented/known/sorted/organized/maintained/veiled’. From our teaching experience, we may say that this use of negative quality adverbs indicating degree is difficult to identify for native speakers of Spanish who tend to associate these adverbs to the meaning of negative evaluation instead of degree. In consequence, they use literal translations in the form of cognate -mente adverbs instead of more idiomatic grading devices available in Spanish. Example (10) shows how the ad-verb poorly has been properly translated into Spanish with an adverb of degree, poco, with no trace of negative quality which would result in pobre, pobremente or something similar.

(10) I first visited Namibia more than twenty years ago, in the company of South African geologist Gerard Germs. A gentle man of philosophical bent, Germs emigrated from the Netherlands as a graduate student and took up the challenge of bringing geologic order to a poorly known region the size of Texas.

Mi primera visita a Namibia se produjo hace más de veinte años en compañía del geólogo sudafricano Gerard Germs, una persona amable y de disposición filosófica que emigró a Sudáfrica desde los Países Bajos para realizar su tesis doctoral y asumió desde entonces el reto de poner orden geológico a una región del tamaño de Texas poco conocida.

Other adverbs not ending in -mente were the second most common option in the translation of -ly adverbs of degree into Spanish (25%), which is an expected result, as adverbs of degree such as muy, casi, poco, más, más o menos, etc. are a frequent way to express grading functions in Spanish. Examples (11) and (12) il-lustrate this fact.

(11) In reality, the assistance offered by German Volksdeutsche in Poland seems to have been largely uncoordinated.

En realidad parece que la ayuda que ofrecieron los alemanes volksdeutsche en Polonia estuvo muy mal coordinada.

© 2008. John Benjamins Publishing CompanyAll rights reserved

Translations of ‘-ly’ adverbs of degree in an English-Spanish Parallel Corpus 285

(12) They said, “No way are all these schmucks worth nearly $ 4 million!”

Dijeron: “¡Es imposible que todos estos inútiles valgan casi cuatro millones de dólares!”

Then PPs follow with a frequency of slightly over 10%. As suggested by Hoye, “periphrastic constructions, usually … prepositional phrases, which function ad-verbially” (1997: 253) have been found to be a typical device to express degree in Spanish. A number of different prepositions may head these PPs, as in examples (13), (14) and (15):

(13) Yet if you look more deeply, is there not only one moment, ever?

Pero, si miras más a fondo, ¿no hay siempre un único momento?

(14) At five feet tall, the canvas almost entirely hid her body.

Su metro y medio de altura casi le ocultaba el cuerpo por completo.

(15) Healing is a living process, Holmes told his audience, greatly under the influence of mental conditions.

La curación es un proceso vivo — dijo Holmes a su audiencia —, en gran parte bajo la influencia de las condiciones mentales.

Modulation accounted for 12%, as in example 16 where the meaning of largely is rendered in the target text in the form of the negative adverb no and the use of the opposite adjective.

(16) If these activities were largely illusory, the result was all too real.

Aunque estas acciones no fueran reales, su resultado sí fue real.

Another example of modulation is illustrated by cases where fixed phrases or idi-oms are used in the target language, as in (17):

(17) “I know you feel strongly about this, but there’s no need for discourtesy”.

Ya sé que te tomas muy a pecho esas cosas, pero no hay ninguna necesidad de ser descortés.

One striking feature in the results is the fact that nearly 8% of cases of -ly adverbs of degree were omitted in the translations as in example (18).

(18) I blushed deeply and turned my head away.

Yo me sonrojé y me volví.

These cases of omission should not be considered translation errors from our point of view, but rather accurate and idiomatic Spanish options. Our empirical data

© 2008. John Benjamins Publishing CompanyAll rights reserved

286 Noelia Ramón and Belén Labrador

support the notion that degree intensifiers are generally more common in English than in Spanish, following the general trend that the English language is more precise and physically descriptive of the real world, whereas the Spanish language remains on a more abstract level (Vázquez Ayora 1977: 44). Previous studies have illustrated this difference, revealing far more details in English than in Spanish in the expression of location within the boundary of the noun phrase (Ramón 2006), and a similar tendency may apply in the case of degree. In our opinion, degree modification may be more frequent in English than in Spanish because of these features of the two languages, and consequently, this fact would explain why all the cases of omission in our corpus were idiomatic.

One of the possible reasons for this trend, which we think plays a role in the relatively high number of omissions, is of a typological nature: the more analytic structure of Spanish compared with the more synthetic character of the English language. Example (19) shows how we need more words for expressing the same meaning in Spanish than in English.

(19) You lived entirely on benefit, had more social workers allocated to you than anyone else in the street, yet for some reason the pressure was always on Annie to move and never on you.

Ustedes vivían de lo que les pagaba el Estado, y tenían asignados más asistentes sociales que ninguna otra familia de esta calle, y sin embargo, no sé por qué, siempre iban detrás de Annie para que se mudara, y no de ustedes.

Another typological feature is the fact that words tend to be longer in Spanish than in English, therefore limiting the space available for additional modifiers, expressing for example degree. Example (20) illustrates this as there are two very long words in the translation (cualquier localización); so using a degree modifier would make it sound rather long and cumbersome. In contrast, the noun phrase in English is very short (‘any spot’) thus leaving the door open for an idiomatic modification with respect to degree.

(20) I imagined myself pacing back and forth trying to place my stake in the spot where I would build my house, but never managing to decide, because in the absence of defining detail, and assuming the Mississippi near enough by, absolutely any spot would do.

Me imaginé a mí misma yendo y viniendo, intentando clavar mi estaca en el emplazamiento en el que edificaría mi casa sin llegar nunca a decidirme, ya que en ausencia de algún detalle definitorio y dando por supuesta la proximidad del río cualquier localización podía servir.

© 2008. John Benjamins Publishing CompanyAll rights reserved

Translations of ‘-ly’ adverbs of degree in an English-Spanish Parallel Corpus 287

However this typological fact accounts for only 12 cases out of 56 of omission (21.42%). The main reason for omitting degree adverbs seems to be the peripheral nature of adverbs in general and degree adverbs in particular, since they do not add essential content to the propositional meaning, facilitating their omission in translations without any real loss of a fundamental part of the ideational function of the message (44 cases in our study — 78.57% of the cases of omission). This ties in with the generally assumed idea that the English language is graphic in physical descriptions where Spanish remains more on the abstract level (Vázquez Ayora 1977: 44). The omission of these degree adverbs simply results in certain lack of precision in the target text.

Finally, other minor resources found in the parallel corpus as equivalents to -ly adverbs of degree into Spanish include transpositions into verbs or part of verbs (21), adjectives (22), quantifying NPs (23), and quantifying determiners (24).

(21) They impressed upon his secretary the urgency of their visit, and after almost forty minutes the door opened slightly.

Los inspectores trataron de hacerle comprender a la secretaria el carácter urgente de la visita y, al cabo de casi cuarenta minutos, la puerta se entreabrió.

As far as adjectives are concerned, recent trends in linguistics highlight the simi-larity in the semantic functions that adjectives and adverbs may express, merging the two categories into one large field called ‘modification’ (Berk 1999; Biber et al. 1999). So it is not surprising that central adjectives are used to express typically adverbial functions such as degree. Example 22 shows a double transposition: the ‘adverb + adjective’ combination in English becomes an ‘adjective + noun’ combi-nation in Spanish.

(22) That was awfully tactless of me.

Ha sido una horrible falta de tacto por mi parte.

With respect to quantifying NPs and determiners, these are resources that express quantification, like mayoría, cada vez (más), todo/a, mucho/a, etc. As a matter of fact, quantification and degree are closely related semantic functions. The former applies to nouns whereas the latter refers to verbs and adjectives.

(23) Some from the university but mostly local business.

Una parte procedía de la universidad pero la mayoría de empresas locales.

(24) It wants to draw your attention in completely.

Quiere captar toda tu atención.

© 2008. John Benjamins Publishing CompanyAll rights reserved

288 Noelia Ramón and Belén Labrador

4.2.2 Register distributionFunctionalist approaches to language (Halliday 1985) highlight the concept of lin-guistic variation, that is to say, language is not used the same way by speakers in different situations or communicative contexts but rather adapts to the needs of particular circumstances: “linguistic features are not uniformly distributed across registers” (Biber et al. 1999: 11). Taking into account the fact that the P-ACTRES corpus includes both fiction and non-fiction texts it was decided to search for potential translation differences across these two registers, as text-type influences translation (Trosborg 1997).

Our findings indicate that the differences between fiction and non-fiction lan-guage lie mainly in the parameters of field and tenor; the mode is written in the two text types. In the case of fiction, the field is literary works, mostly contempo-rary novels which may deal with a large variety of topics but they all have in com-mon a narrative and descriptive nature. The aesthetic and entertaining purposes are dominant here, thus leading to a type of language which is expected to exploit the linguistic resources to the full. As for tenor, authors of novels write their texts with the aim of making readers enjoy invented stories through the use of language, and readers approach these texts mostly as a leisure or cultural activity.

Non-fiction texts, on the other hand, are produced under very different cir-cumstances. As far as field is concerned, the contents of these texts belong to specific academic disciplines such as history, science, politics, etc. This implies a particular level of formality, specific vocabulary and a more direct style in the expression of ideas. The authors of these texts are usually experts in their fields writing for a non-expert general public, and the aim is mainly instructive. Readers of these texts approach them to get information on a specific topic.

The translation equivalents found for -ly adverbs of degree were classified ac-cording to their register distribution: fiction vs. non-fiction in order to identify possible differences in the expression of degree due to text type. Figure 2 sum-marises the results:

01020304050

-men

te ad

vs.

other ad

vs PP

modulation

omission

ADJNP VP

DET

FICTION NON-FICTION

Figure 2. Cross-register distribution of the Spanish translations of -ly degree adverbs

© 2008. John Benjamins Publishing CompanyAll rights reserved

Translations of ‘-ly’ adverbs of degree in an English-Spanish Parallel Corpus 289

The data in Figure 2 indicate that fiction translators appear to be less con-strained by the linguistic features of the source text, e.g., -mente adverbs are not the most frequently employed translations in fiction texts; other adverbs are pre-ferred. This indicates that translators of fiction are more reluctant to use -mente adverbs, thus not sticking as often as the other translators to the source language items, -ly adverbs. Another piece of evidence that supports this claim is the fact that there is more modulation in the translations of fiction texts, which reflects the expression of similar meanings from different points of view, using a richer and more varied vocabulary.

Non-fiction translators, in contrast, rely more heavily on the formal equiva-lents of -ly adverbs, i.e. -mente adverbs, probably because they are more concerned with communicating the contents than about which linguistic resources are used to communicate these contents. The focus lies more on the ‘what’ than on the ‘how’ of the translation. In addition, non-fiction translations showed fewer cases of modulation. This ties in with the less creative nature of this text type, which motivates non-fiction translators less to find more varied and elegant linguistic expressions to convey the meanings of -ly adverbs in Spanish.

On the whole, it can be said that fiction texts, because of their nature, seem to allow for a higher degree of freedom in their translations.

4.3 Intralinguistic analysis: Identifying -mente translationese in Spanish

After a detailed analysis of the English examples and their translations into Span-ish, it was considered necessary to take a closer look at the Spanish -mente adverbs because we suspected that there could be an overuse of these items in the transla-tions with respect to non-translated Spanish.

We selected the most frequent -mente adverbs in the parallel corpus and com-pared their frequencies with data from the reference corpus of contemporary Spanish CREA to see whether they were being used more often than the norm in original Spanish. If this was the case, this would be an instance of ‘translationese’, linguistic features that distinguish translated texts from texts written originally in a particular language. Translationese can be detected statistically in an overuse or underuse of particular lexical items in translated texts.

Our initial hypothesis is that there could be an overuse of -mente adverbs in the Spanish translations. As mentioned above, native Spanish speakers tend to avoid -mente adverbs in original texts, but since they are cognates of -ly adverbs we expect a higher frequency of occurrence of -mente adverbs in translations due to the influence of the source language.

As mentioned above the two corpora differed in size. A first step was to calcu-late the number of occurrences of each -mente adverb per million words. Figure 3

© 2008. John Benjamins Publishing CompanyAll rights reserved

290 Noelia Ramón and Belén Labrador

below illustrates the number of cases per million words of the 8 most common -mente adverbs in our translations of -ly adverbs, most of which express an abso-lute or very high degree.

A first look at the graph enables us to detect a general trend of overuse of these -mente adverbs in translated Spanish, sometimes a slight overuse as in the cases of ampliamente and extremadamente, and sometimes a much more important over-use as in the cases of completamente, prácticamente and profundamente. The only exception to this tendency is the adverb absolutamente, which is more often used in original Spanish than in translated Spanish. The results indicate that for most -mente adverbs, translators tend to use them to a greater extent than native speak-ers of Spanish actually do. However, there are different degrees of overuse depend-ing on each individual -mente adverb, which suggests a lexical preference on the part of translators for some over others. In order to determine the relevance of the differences between the frequency rates in original versus translated Spanish, a second step was necessary: the chi-square test for statistical significance had to be used. Using this test it was found that the difference is statistically significant for p-value<0.05 in four out of eight cases. The data are as follows:

Table 3. Raw frequencies and p-value of the most common -mente adverbsAdverb P-actres Crea P-valueAbsolutamente 19 2,589 0.03Ampliamente 14 765 0.11Completamente 72 2,568 0Extremadamente 12 741 0.29Prácticamente 65 3,956 0.01Profundamente 33 1,383 0.0006Relativamente 23 1,683 0.51Totalmente 61 4,257 0.15

020406080

100120

Absolutamen

te

Ampliamen

te

Completam

ente

Extrem

adam

ente

Práctic

amen

te

Profundamen

te

Relativ

amen

te

Totalmen

te

original Spanishtranslated Spanish

Figure 3. Number of occurrences per million words

© 2008. John Benjamins Publishing CompanyAll rights reserved

Translations of ‘-ly’ adverbs of degree in an English-Spanish Parallel Corpus 291

Table 3 shows that there is translationese in four out of the eight most common degree -mente adverbs found in P-ACTRES. In 3 cases (completamente, práctica-mente, profundamente) translationese is due to overuse of the adverb, as we ini-tially suspected, because of the influence of the source language. In contrast, the adverb absolutamente was found to be less commonly used in translations than in original Spanish texts. The only plausible explanation that may contribute to clarify this fact is the relatively low frequency of occurrence of the cognate abso-lutely (14 instances) in the English source texts when compared to other -ly ad-verbs of degree that express absolute degree like completely (48 instances). So the translators are not prompted by the source language to use absolutamente as an equivalent. There is, however, an overuse of completamente which plays in detri-ment of absolutamente.

5. Discussion

The most significant facts relative to the analysis of the -ly adverbs included in the study refer to recurring patterns in the case of certain lexical items: both syn-tagmatic and semantic. Collocational trends were identified in the cases of the adverbs partly, closely and virtually and an instance of negative semantic prosody in the case of the adverb deeply (e.g. deeply troubling). The adverb partly was found to occur mostly along with a causal conjunction; closely tended to occur with verbs of visual perception and with past participles indicating connection, and virtually presented two clearly distinct patterns: it co-occurred with universal quantifiers and negative particles.

The analysis of the parallel corpus of contemporary writing revealed a wide range of different translational options as equivalents of -ly adverbs of degree. The most frequent translational option employed for conveying the meaning of -ly ad-verbs of degree is the use of -mente adverbs in Spanish (33%). Among the other re-sources used, single adverbs are particularly common in the expression of degree (25%) as compared with their use in the expression of other semantic functions (time 9.5%; manner 2% (Rabadán et al. 2006)). While other adverbs range second after -mente adverbs in the expression of degree, they occupy the fifth position in the translation of -ly adverbs regardless of their semantic function, where PPs were the second most important option (Rabadán et al. 2006).

The study of the translations showed that the link between -ly adverbs of degree and their corresponding Spanish cognates in -mente is not so strong, as the same adverb (e.g. completamente) has been found to translate up to six differ-ent -ly adverbs of degree. On the other hand, one single -ly adverb of degree was translated into several different -mente adverbs: e.g. absolutely into absolutamente,

© 2008. John Benjamins Publishing CompanyAll rights reserved

292 Noelia Ramón and Belén Labrador

estrictamente and totalmente. This illustrates the many-to-many relationship that exists between form and meaning and how collocational matters play a role here.

One important finding in the analysis of translations is what we may call ‘idi-omatic omission’ — cases where it is more acceptable in the target language to omit a particular item in the source language rather than trying to use a transla-tion equivalent ‘by hook or by crook’ to the detriment of idiomaticity and natural-ness in the target language. Omission occurs less frequently in the translation of -ly adverbs expressing degree (under 8%) than in the expression of all semantic functions put together (16%) (Rabadán et al. 2006). This indicates that the mean-ing of degree does not tend to be omitted so often as when -ly adverbs express some other meanings. All the instances of -ly adverbs of degree that were omitted in the Spanish translations can be considered idiomatic omissions.

A cross-register analysis revealed that -mente adverbs were more common in non-fiction translations, whereas there were more adverbs not ending in -mente and more modulation in fiction translations. These results suggest that fiction texts are less source-text dependent and allow for a higher degree of freedom in the translations, whereas non-fiction translators are more concerned with the con-tents and less with the form and therefore tend to stick more to the source text forms.

As for the intralinguistic analysis of Spanish -mente adverbs, one important result is related to the identification of translationese in the parallel corpus, which means that Spanish translators use certain -mente adverbs either more or less fre-quently compared with the native usage of these items. We found that 50% of the most common degree -mente adverbs in P-ACTRES were either overused (three cases in four) or underused (one case in four) when compared to their frequency in original Spanish texts in CREA.

6. Conclusion

This paper has studied the Spanish translations of English -ly adverbs of degree us-ing empirical data from the P-ACTRES parallel corpus. Our teaching experience in contrastive studies and in FLT drew our attention towards this highly produc-tive suffix in English, traditionally associated with the expression of manner, and the possible translations into Spanish, bearing in mind that the cognate -mente adverbs in this language are not always pragmatically equivalent to the English adverbs. A preliminary analysis of a large number of -ly adverbs and their trans-lations into Spanish revealed that, after manner, the most important semantic function expressed by these adverbs is degree (Rabadán et al. 2006). This finding prompted the present study.

© 2008. John Benjamins Publishing CompanyAll rights reserved

Translations of ‘-ly’ adverbs of degree in an English-Spanish Parallel Corpus 293

The analysis was divided into three parts: first, an intralinguistic study of the English types selected, second, an interlinguistic analysis of the corresponding Spanish translations and finally, an intralinguistic comparison of the use of -mente adverbs in translated Spanish and original Spanish.

The results obtained in this study can be applied in different fields. The data found with respect to the collocational patterns identified in the analysis of the English -ly adverbs used are particularly helpful for the development of FLT ma-terials, since they highlight interesting facts about the use of these adverbs in dis-course. Next, the results of the cross-linguistic section of this study provided an inventory of translation solutions available in Spanish which can be considered as a useful tool in translation practice as well as in translator training. Finally, the findings of the Spanish intralinguistic comparison have practical applications in the field of translation quality assessment.

Notes

* This study was partially supported by Projects ULE2003–12 (University of León), HUM2005–01215 (Spanish Ministry of Education) and LE003A05 (Junta de Castilla y León).

1. Data extracted from CREA (Corpus de Referencia del Español Actual) (15-02-2007) select-ing exclusively texts from Spain.

2. Spanish acronym for “Contrastive Analysis and Translation English-Spanish”.

References

Baker, Mona. 1998. “Réexplorer la langue de la traduction: une approche par corpus”. Meta 43:4. 480–485.

Baker, Mona. 2004. “A corpus-based view of similarity and difference in translation”. Interna-tional journal of corpus linguistics 9:2. 167–193.

Berk, L.M. 1999. English syntax. From word to discourse. Oxford: OUP.Biber, Douglas, Stig Johansson, Geoffrey Leech, Susan Conrad and Edward Finegan. 1999. Long-

man grammar of spoken and written English. London: Longman.Bolinger, Dwight. 1972. Degree words. The Hague–Paris: Mouton.Halliday, Michael A.K. 1985: An introduction to functional grammar. London: Arnold.Hofland, Knut and Stig Johansson. 1998. “The translation corpus aligner: A program for auto-

matic alignment of parallel texts”. Stig Johansson and Signe Oksefjell, eds. Corpora and cross-linguistic research: Theory, method and case studies. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1998. 87–100.

Hoye, Leo. 1997. Adverbs and modality in English. London: Longman.Klein, Henny. 1998. Adverbs of degree in Dutch and related languages. Amsterdam–Philadelphia:

John Benjamins.Laviosa, Sara. 1998. “The English comparable corpus: A resource and a methodology”. Lynne

© 2008. John Benjamins Publishing CompanyAll rights reserved

294 Noelia Ramón and Belén Labrador

Bowker, Michael Cronin, Dorothy Kenny and Jennifer Pearson, eds. Unity in diversity?: Current trends in Translation Studies. Manchester: St. Jerome, 1998. 101–112.

Louw, Bill. 1993. “Irony in the text or insincerity in the writer?: The diagnostic potential of semantic prosodies”. Mona Baker, Gill Francis and Elena Tognini-Bonelli, eds. Text and technology. In honour of John Sinclair. Amsterdam–Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 1993. 157–176.

Mauranen, Anna. 2000. “Strange strings in translated language: A study on corpora”. Maeve Olohan, ed. Intercultural faultlines: Research models in Translation Studies I: Textual and cognitive aspects. Manchester: St. Jerome, 2000. 119–141.

Mauranen, Anna. 2004. “Corpora, universals and interference”. Mauranen and Kujamäki 2004. 65–82.

Mauranen, Anna and Pekka Kujamäki, eds. Translation universals: Do they exist? Amsterdam–Philadelphia: John Benjamins

Olohan, Maeve. 2004. Introducing corpora in Translation Studies. London: Routledge.Paradis, Carita. 1997. Degree modifiers of adjectives in spoken British English. Lund: Lund Uni-

versity Press.Rabadán, Rosa, Belén Labrador and Noelia Ramón. 2006. “Putting meanings into words: Eng-

lish -ly adverbs in Spanish translation”. Cristina Mourón Figueroa and Teresa Iciar Mo-ralejo Gárate, eds. Studies in contrastive linguistics. Santiago de Compostela: Universidad de Santiago de Compostela, 2006. 855–862.

Ramón, Noelia. 2006. “Mapping meaning onto form: A corpus-based contrastive study of nomi-nal modification in English and Spanish”. Languages in contrast 6:2. 307–334.

Tirkkonen-Condit, Sonia. 2002. “Translationese — a myth or an empirical fact?: A study into the linguistic identifiability of translated language”. Target 14:2. 207–220.

Tirkkonen-Condit, Sonia. 2004. “Unique items — over- or under-represented in translated lan-guage?”. Mauranen and Kujamäki 2004. 177–186.

Trosborg, Anna, ed. 1997. Text typology and translation. Amsterdam–Philadelphia: John Ben-jamins.

Vázquez Ayora, Gerardo. 1977. Introducción a la Traductología: Curso Básico de Traducción. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press.

Vinay, Jean-Paul and Jean Darbelnet. 1958: Stylistique comparée du français et de l’anglais. Paris: Didier.

Résumé

Le présent article porte sur la traduction en espagnol des adverbes de degré anglais qui se termi-nent par -ly. Le suffixe anglais -ly est traditionnellement associé à l’expression de manière. Ce-pendant, il évoque également d’autres significations, telles que le sens de degré qui nous intéresse en l’occurrence. En espagnol, les équivalents formels des adverbes en -ly sont des adverbes qui se terminent par -mente, mais ils sont moins fréquents et entraînent des nuances pragmatiques différentes. Les adverbes de degré se traduisent non seulement par des adverbes en -mente, mais aussi par d’autres outils linguistiques tels que des adverbes qui ne se terminent pas par -mente, des phrases prépositionnelles, des adjectifs, etc. L’objectif est d’établir une taxinomie des ressour-ces de traduction extraites d’un corpus parallèle afin de révéler des correspondances interlinguis-tiques utiles dans la formation des traducteurs et dans l’appréciation qualitative des traductions.

© 2008. John Benjamins Publishing CompanyAll rights reserved

Translations of ‘-ly’ adverbs of degree in an English-Spanish Parallel Corpus 295

Authors’ addresses

Noelia Ramón and Belén LabradorDepartamento de Filología ModernaFacultad de Filosofía y LetrasUniversidad de LeónCampus de Vegazana s/n24071 LEóNSpain

[email protected]; [email protected]

Appendix. Sample of -ly degree adverbs studied

Fiction Non–fiction Total1. Absolutely 10 4 142. Awfully 4 – 43. Badly 3 2 54. Barely 35 18 535. Broadly 1 6 76. Closely 12 28 407. Completely 26 22 488. Considerably – 1 19. Deeply 14 11 2510. Densely – 1 111. Desperately 15 4 1912. Drastically – – 013. Entirely 18 19 3714. Extremely 11 7 1815. Faintly 3 2 516. Greatly 5 3 817. Hardly 41 22 6318. Highly 15 14 2919. Horribly 1 – 120. Immensely 1 1 221. Increasingly 5 19 2422. Keenly – – 023. Largely 5 19 2424. Loosely 4 2 625. Ludicrously 1 – 126. Merely – – 027. Mostly 10 18 28

© 2008. John Benjamins Publishing CompanyAll rights reserved

296 Noelia Ramón and Belén Labrador

Fiction Non–fiction Total28. Nearly 22 19 4129. Overwhelmingly 1 2 330. Partly 6 5 1131. Poorly – 7 732. Profoundly 2 10 1233. Reasonably – 4 434. Relatively 1 17 1835. Roughly 1 5 636. Significantly 2 5 737. Slightly 29 6 3538. Spectacularly 2 2 439. Strikingly – 1 140. Strongly 4 3 741. Supremely – 3 342. Thickly 1 1 243. Thoroughly 8 7 1544. Vaguely 8 2 1045. Virtually 5 14 1946. Wholly 4 8 1247. Widely 3 18 21TOTAL 339 362 701

![[ADVERBIAL[Pr LY]] - Norbert Corver](https://static.fdokumen.com/doc/165x107/63275702051fac18490e32af/adverbialpr-ly-norbert-corver.jpg)