“Toward the Philosophy of Work: The Late Paintings of Leopold Gottlieb”, Ars Judaica, vol. 9...

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

3 -

download

0

Transcript of “Toward the Philosophy of Work: The Late Paintings of Leopold Gottlieb”, Ars Judaica, vol. 9...

Ar

s

Ju

da

ic

a

20

13

1

Toward the Philosophy of Work: The Late Paintings of Leopold Gottlieb

Artur Tanikowski

Most of the references in the notes are to books and articles in Polish.

1 Gottlieb’s biography, as well as an interpretation of his work, are developed in the book based on my Ph.D. thesis: Artur Tanikowski, Wizerunki człowieczenstwa, rytuały powszedniosci: Leopold Gottlieb i jego dzieło (Likenesses of Humanity, Rites of Commonness: Leopold Gottlieb and His Work) (Cracow, 2011) (Polish with English summary), where I propose the most general periodization of his artistic activity, dividing it into three periods: 1. Gottlieb’s youth and maturation: 1898–1914; 2. The artist in the Polish Legions: World War I, 1914–18; 3. After

The image of human beings was always at the center of Leopold Gottlieb’s oeuvre (fig. 1). Still life and landscape painting are few and far less common. Before World War I, Gottlieb was primarily a painter of portraits, with only a limited number of narrative compositions. However, after the war the numbers were reversed, and Gottlieb’s works, especially in the minds of critics, began to combine a unique vision of labor and rest, depicting them as activities that ennoble human existence. There were several different reasons that lead to this change. The most important and decisive was Gottlieb’s newly awakened social sensibility. The idea of social solidarity also appeared at this time in his narrative compositions on New Testament themes. In his paintings, Gottlieb began depicting both the values of mercy and empathy, followed by the need for unselfish help in the face of poverty, and the physical degradation of a human being. The objective of the present article is to describe and interpret these lesser known and discussed works of Gottlieb’s later period, as well as to explore the paths that steered him to his vision.1

From Drohobycz to ParisLeopold Gottlieb was born on 3 June 18792 in Drohobycz, Austro-Hungarian Galicia, in the Lwów district (today: western Ukraine), as the last of eleven children of

the war: 1919–1934. The present article is a variant and further development of my exploration of the artist’s third, post-World War I, period.

2 Hanna Bartnicka-Górska, “Gottlieb Leopold,” in Słownik artystów polskich i obcych w Polsce działajacych. Malarze, rzezbiarze, graficy (Dictionary of Polish Artists and Those Active in Poland: Painters, Sculptors, Engravers), vol. 2 (Wrocław, et al., 1975), 423. The date of Leopold’s birth is confirmed in the catalogue of his posthumous exhibition at the Salon des Tuileries in 1934: “Né le 3 juin 1879. Décédé à Paris le 24 avril 1934.”

Fig. 1. Portrait of an Elderly Man (Portrait of a Man), ca. 1904–6, oil on

canvas, 100 × 70 cm, Israel Museum, Jerusalem. All illustrations in this article

are by Leopold Gottlieb

Ar

s

Ju

da

ic

a

20

13

2

Artur Tanikowski

Izaak and Felicja (Fanja), née Tiegerman.3 Izaak was a pious Jew and one of the first producers of crude oil in the region.4 A follower of the developments of Haskalah (the Jewish Enlightenment movement), he sent his children to public schools to prepare them for life and coexistence with non-Jewish society. A number of them displayed artistic talent and were encouraged to follow it. Thus, three of Leopold’s five brothers were painters; among them the most famous was Maurycy Gottlieb (1856–79), the oldest of the siblings.5 One of six Gottlieb daughters, Jadwiga (Róz.a), married the artist Mieczysław Jakimowicz (1881–1917),6 one of Leopold’s friends who belonged to the same art establishment.

According to the testimony of Krystyna Miłobedzka, Leopold’s niece, his first wife was Klementyna Wolerner, the daughter of a lawyer from Drohobycz.7 This marriage was short-lived, because “she doesn’t understand his talent and is not able to be truly an artist’s wife.”8 About 1905

Leopold married Aurelia, née Polturak (1865–1943), who was born in Lwów.9 After studying art history and philosophy in Vienna and Berlin, and finishing her doctoral dissertation, Aurelia became a forceful propagator of Zionist ideas.10 She was active as an art critic and translator and “had a strong influence on her husband as well as on his art.”11

Critics discussing the life and work of Leopold Gottlieb usually stress that from the beginning of his career he was perceived as a follower of the “great Maurycy,” his famous brother.12 In 1929 Leopold recalled: “From my very first years I had been raised in an artistic climate. My brother was Maurycy Gottlieb. At the age of five I began to paint. At the age of seven I executed my first historical composition.”13 In his young years Leopold sought artistic patronage among his brother’s former friends. When enrolling at Cracow’s School of Fine Arts, he mentioned in his registration forms having completed four classes of high school.14 Most likely it was the Franz Josef

3 Based on birth certificates, we can try to set the birth order of Izaak and Felicja’s children: Maurycy: 1856–79; Anna (Chana, Taube): born 1860; Rebeka (Recia): born 1865; Marcin: 1867–1931; Filip: born ca. 1870; Malka: 1872–93; Mendel: 1874 (or 1875), died after 8 months; Rachela: born 1878; Stanisław: ?; Jadwiga (Ró.za, Inga): ?; and Leopold (Liepe): 1879–1934. “Wypis z Aktów Metrykalnych Drohobycza w d. województwie Lwówskim – urodzeni w latach 1877–1905” (Excerpts from the Public Register of Births in Drohobycz of the Former Lwów [Lemberg] District – for those born between 1877–1905), Archiwum Główne Akt Dawnych w Warszawie (Central Archives of Historical Records in Warsaw), 263/240.

4 Ezra Mendelsohn, Painting a People: Maurycy Gottlieb and Jewish Art (Hanover and London, 2002), 21–22; Arpad Weixlgärtner, “Leopold Gottlieb,” Die Graphishen Künste 42 (1920): 77–82.

5 Marcin and Filip preceded Leopold in the footsteps of Maurycy. Both made copies of some famous paintings by Maurycy. Marcin was a portraitist and author of scenes from the history of Polish Jews, generic Jewish scenes, and paintings inspired by Polish literature; see Jerzy Malinowski, Malarstwo i rzezba

.Zydów Polskich w XIX i XX wieku

(Painting and Sculpture of Polish Jews in the 19th and 20th Centuries) (Warsaw, 2000), 89–90.

6 Jan Kazimierz Kapera, Mieczysław Jakimowicz 1881–1917: Szkic biograficzny (Mieczysław Jakimowicz 1881–1917: Biographical Sketch) (New York, 2005).

7 Krystyna Miłobedzka, “Pare słów o Leopoldzie Gottliebie” (A Few Words on Leopold Gottlieb), typescript of a letter to Józef Sandel, Archives of Józef and Ernestyna Sandel, Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw, 1.

8 Ibid.

9 “Wypis z Aktów Metrykalnych d. województwa Lwowskiego (urodzeni w latach 1863–76, 1900, 01)” (Excerpts from the Public Register of Births in the Former Lwów District – for those born between 1863 and 1876, in 1900 and 1901), Central Archives of Historical Records in Warsaw), 62 / 519.

10 Józef Sandel, “Aurelia Gottliebowa,” manuscript in the Archives of Józef and Ernestyna Sandel, Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw. Sandel noted that between 1928 and 1932 Aurelia published her monographic texts on the Jewish painters in Paris in the Menorah magazine as well as in Miesiecznik

.Zydowski (Jewish Monthly). She also

worked as a translator.11 Ludwik Oberlaender, “Pamieci Leopolda Gottlieba” (In the Memory of

Leopold Gottlieb), Miesiecznik .Zydowski 4 (1934): 362–63.

12 “Nota od redakcji” (Editorial), in Oberlaender, “Pamieci Leopolda Gottlieba,” 359. (h), “Leopold Gottlieb, Z powodu zgonu wielkiego artysty” (Because of the Death of Leopold Gottlieb, the Great Artist), Nowy Dziennik 120 (1934): 4–5; Cecil B. Roth, Die Kunst der Juden (Frankfurt am Main, 1964), 133, an excerpt in the Archives of Józef and Ernestyna Sandel, Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw; Weixlgärtner, “Leopold Gottlieb”; Roger Brielle, “Les peintres juifs: Modigliani et l’inquiétude nostalgique,” L’Amour de l’Art 6 (1933): 141–47; K.M. [Kazimierz Mitera], “Leopold Gottlieb: Wspomnienie posmiertne” (Leopold Gottlieb: Posthumous Recollection), Głos Plastyków 9–12 (1934): 162.

13 Roman Brandstaetter, “U Leopolda Gottlieba” (Visiting Leopold Gottlieb), Gazeta Polska 56 (1929).

14 Materiały do dziejów Akademii Sztuk Pieknych w Krakowie 1895–1939 (Records for the History of the Academy of Fine Arts in Cracow), eds.

Ar

s

Ju

da

ic

a

20

13

3

Toward the Philosophy of Work:The Late Paintings of Leopold Gottlieb

gymnasium in Drohobycz, the same one that sometime earlier Maurycy had attended.15Although we have no details about Leopold’s high-school education, one point should be made clear: his Polish skills were much better than Maurycy’s, whose “chief language” was German.16

Among Leopold Gottlieb’s teachers at the School of Fine Arts in Cracow, where he enrolled on 23 October 1896,17 was Jacek Malczewski (1854–1929), a leading painter of Polish Symbolism.18 Leopold was influenced by Malczewski’s strong interests in symbolism and allegorical representation rather than by the so-called pure painting favored by the Polish followers of Impressionism or Post-impressionism. Moreover, like Malczewski, throughout his artistic career Leopold Gottlieb rarely abandoned the so-called literary subject of the painting.19

In 1902, upon completing his studies in Cracow, Gottlieb won a gold medal and a scholarship that enabled him to continue his studies in Munich.20 However, rather

than enrolling at the Academy, he studied at the private art school of the Slovenian painter Anton Ažbè (1862–1905). This school was very popular among students from Slavic countries,21 and Gottlieb met the international artistic elite there, as well as some future Polish-Jewish friends. Munich’s Jugendstil, as well as the city’s excellent collections of the art of the past, played an important role in further shaping Gottlieb’s artistic horizons.22 Two years later, in 1904, Gottlieb moved to Paris. Though he stayed there for no more than a few months, he was able to debut at the Paris Salons.23

The works of young Leopold Gottlieb were firmly connected to the Młoda Polska (Young Poland) movement with its fin-de-siècle aura: pessimism, fatalism, and the advantage of symbolism’s pathos and emotional element.24 One can examine these notions either through the titles of Gottlieb’s earliest (but no longer existant) works, exhibited in Kołomyja in the summer of 1898,25 or in

Józef E. Dutkiewicz, Jadwiga Jeleniewska-Slesinska, and Władysław Slesinski (Wrocław, Warsaw, and Cracow, 1969), 278.

15 Jerzy Malinowskiand Barbara Brus-Malinowska, W kregu École de Paris: Malarze z.ydowscy z Polski (In the Circle of the École de Paris: Jewish Painters from Poland) (Warsaw, 2007), 68.

16 Ezra Mendelsohn, “Gottlieb, Maurycy,” in The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe, http://www.yivoencyclopedia.org/article.aspx/Gottlieb_Maurycy (accessed 20 June 2012). Leopold said of Maurycy: “My brother came from a heder. He was a very pious Jew who carefully observed all the rules. My brother didn’t even speak good Polish”; see Roman Brandstaetter, “Rozmowy z Leopoldem Gottliebem” (Conversations with Leopold Gottlieb), Opinia 18 (1934): 5.

17 Leopold Gottlieb, “Formularz dla kandydatów do C.K. Szkoły Sztuk Pieknych [w Krakowie]” ([Leopold Gottlieb’s] EnrollmentForm for Candidates to Study at the School of Fine Arts in Cracow), Archives of the Academy of Fine Arts in Cracow.

18 Malczewski was a professor between the academic years 1896/1897 and 1899/1900; see Materiały do dziejów Akademii Sztuk Pieknych w Krakowie, 191. A few decades earlier Malczewski had befriended Maurycy Gottlieb in the Cracow class of Jan Matejko; see Moj.zesz Waldman, Maurycy Gottlieb: Biografia artystyczna (Maurycy Gottlieb’s Artistic Biography) (Cracow, 1932).

19 Materiały do dziejów Akademii Sztuk Pieknych w Krakowie, 21.20 Józef Andrzej Teslar, “O twórczosci malarskiej Leopolda Gottlieba

(Z powodu wystawy w I.P.S.)” (On the Painting of Leopold Gottlieb, because of the Exhibition at IPS), Pion 27 (1935): 6.

21 Twenty-seven Poles studied at the school until 1905; Halina Stepien, Artysci polscy w srodowisku monachijskim w latach 1828-1914: Materiały zródłowe (Polish Artists in the Munich Milieu between 1828 and 1914: Materials) (Warsaw, 1994), 76. Ažbè’s most famous students were three

Russians: Wassily Kandinsky, Alexiej Jawlensky, and Marianne von Werefkin; and one Ukrainian, Dawid Burliuk.

22 It is quite possible that he met Jewish artists there who later became his colleagues in Paris: Eugeniusz (Eugene) Zak, Elie Nadelman, and Roman Kramsztyk from Poland, Bela Czobel from Hungary, and Jules Pascin from Bulgaria.

23 He exhibited at the Salon des Independants and Salon d’Automne; Hanna Bartnicka-Górska and Joanna Szczepinska-Tramer, W poszukiwaniu swiatła, kształtu i barwy: Artysci polscy wystawiajacy na Salonach paryskich w latach 1884–1960 (In Search for Light, Shape, and Color: Polish Artists Exhibiting at the Parisian Salons between 1884–1960) (Warsaw, 2005), 30, 141.

24 “Young Poland movement, a diverse group of early 20th-century Neoromantic writers brought together in reaction against Naturalism and Positivism. Inspired by Polish Romantic writers and also by contemporary western European trends such as Symbolism, they sought to revive the unfettered expression of feeling and imagination in Polish literature and to extend this reawakening to all the Polish arts. Centred in Kraków, the movement was pioneered by the poet Antoni Lange and by the editor and critic Zenon Przesmycki (‘Miriam’), an early Polish modernist.” Encyclopaedia Britannica http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/654106/Young-Poland-movement (accessed 25 Sept. 2012). The 1890s term “Młoda Polska” was originally applied to literature, but gradually became synonymous with art from around 1900, particularly Polish Symbolism, secession, Neo-Romanticism, and Early Expressionism. Its main advocates/exponents were Stanisław Wyspianski, Jacek Malczewski, Ferdynand Ruszczyc, Konrad Krzyz.anowski, Olga Boznanska, Józef Mehoffer, Leon Wyczółkowski, and Teodor Axentowicz.

25 Particular titles of works exhibited in Surzynski’s café in Kołomyja: Wyrzuty sumienia (Remorse), Widmo nedzy (Wraith of Misery), Połów

Ar

s

Ju

da

ic

a

20

13

4

Artur Tanikowski

his engravings, published together with works of Ludwik Cylkow in their Album of Lithographs (Paris, 1904).26 The scenes depicted by Gottlieb are overwhelmed by the aura of panpsychism, typical of turn-of-the-century modernism:

the elements of nature – trees, water, clouds – add to the elegiac and melancholic context of the depicted figures.27 In Potok (Stream), a leafless tree, sloping upon the lonely silhouette, seems to share her silent despair. In Pogrzeb (Funeral) (fig. 2), a procession of mourners carrying the coffin seems to be accompanied by the line of the cemetery’s birches. Creating lithographs for the album, Gottlieb built his compositions basing himself mostly on linear values and flat spots of dim and pale colors, adopted from the palette of the Nabis.

Back in Cracow, in 1904 Gottlieb established the “Group of Five,” together with four of his artist friends.28 As the group’s initiator and president, he presented the credo of the five young artists in his article for the magazine Krytyka.29 He openly came out against the “Sztuka” (Art) Society for its fossilization, elitism, and rejection of young talent.30 He also specified his artistic priorities and selected the group’s allies and patrons – Wojciech Weiss, Olga Boznanska, and Stanisław Wyspianski. For him, their art is connected by “deep feeling, which is dreamy and

trupów (Catching the Corpses), Złe mysli i skrucha (Bad Thoughts and Repentance), Dwa bóstwa (Two Deities), Usmiech z.ycia (Smile of Life) or Utrapienie (Annoyance). Other subjects undertaken by Gottlieb in Kołomyja stemmed from the Jewish religion and tradition as well as from the history of Poland; see “Młody Gottlieb” (Young Gottlieb), Gazeta Kołomyjska 75 (1898): 3. During his summer vacations in Kołomyja Gottlieb also painted portraits; “W pracowni Gottlieba” (In Gottlieb’s Studio), Gazeta Kołomyjska 47 (1898): 3.

26 Five works of Gottlieb from the album are entitled: Pogrzeb (Funeral), Most (Bridge), Wymarłe miasto (Dead City), Potok (Stream), and Przygnebienie (Depression). Except for Przygnebienie, of which there is no known copy, Gottlieb’s other lithographs from the album are in the collections of the Library of the Warsaw University (Department of Prints) and the National Museum in Warsaw.

27 “One of the fundamental tenets of modernism is the conviction that the phenomena of nature, to which human beings also belong, are interrelated and that the universe, understood as a monistic entity, is both material and spiritual in its substance,” Wiesław Juszczak, Wojtkiewicz i nowa sztuka (Wojtkiewicz and New Art) (Warsaw, 1965) (Polish with English summary), summary, 184.

28 In addition to Gottlieb, the other members of the group were Vlastimil Hofman, Mieczysław Jakimowicz, Jan Rembowski, and Witold Wojtkiewicz. After Wojtkiewicz left his friends, Tymon Niesiołowski joined the group for their last exhibition. The Group of Five held exhibitions between 1905 and 1908 in Cracow, Lwów , Warsaw, Vienna, Berlin, Cologne, Düsseldorf, and Munich. There are two major references to the history of the group and the art of its members, as well

as the group’s significance for modern Polish art: Juszczak, Wojtkiewicz i nowa sztuka; Małgorzata Geron, “Grupa Pieciu (1905–1908)” (The Group of Five 1905–1908), in Sztuka lat 1905–1923: Malarstwo – rzezba – grafika – krytyka artystyczna (Art between 1905–1923: Painting, Sculpture, Graphics, Art Criticism), eds. Małgorzata Geron and Jerzy Malinowski (Torun, 2006), 43–49. Wiesław Juszczak calls the group “the avant garde of early expressionism”; Juszczak, Wojtkiewicz i nowa sztuka, summary, 184.

29 Leopold G.[ottlieb], “IX. Wystawa ‘Sztuki’”(The Ninth Exhibition of the “Sztuka” Society), Krytyka 1 (1905): 470–72.

30 Towarzystwo Artystów Polskich“Sztuka” (The “Art” Society of the Polish Artists), established in Cracow in 1897 and officially active until 1950, brought together the elite of the Young Poland movement. Rather than creating a new coherent aesthetic program, its main task was raising the general level of art and art exhibitions in Poland. Among the society’s members were artists such as Teodor Axentowicz, Józef Chełmonski, Julian Fałat, Jacek Malczewski, Józef Mehoffer, Antoni Piotrowski, Jan Stanisławski, Włodzimierz Tetmajer, Leon Wyczółkowski, and Stanisław Wyspianski. The “Sztuka” Society was considered an official representative of Polish art at the turn of the twentieth century. For further references, see Sztuka kregu “Sztuki”: Towarzystwo Artystów Polskich “Sztuka” 1897–1950 (Art of the “Art” Circle: “Art” Society of the Polish Artists 1897–1950) [catalogue, National Museum in Cracow], curator Stefania Krzysztofowicz-Kozakowska (Cracow, 1995); Stulecie Towarzystwa Artystów Polskich “Sztuka” (The Centenary of the “Art” Society of the Polish Artists) (Cracow, 2001).

Fig. 2. Funeral, 1904, color lithography on paper, 25 × 32 cm, Library of the

Warsaw University, Department of Prints

Ar

s

Ju

da

ic

a

20

13

5

Toward the Philosophy of Work:The Late Paintings of Leopold Gottlieb

inclined for contemplation, which likes the silence and manifests itself in a discrete way.”31

Members of the group chose Cyprian Norwid (1821–1883), a romantic poet and talented visual artist whose work had just been rediscovered by writers and critics of the Młoda Polska (Young Poland) movement, as their patron.32

Another area of Gottlieb’s activity in Cracow was connected to a circle of young Jewish artists, writers, and intellectuals grouped around Samuel Hirszenberg (1865–1908).33 Hirszenberg, who had recently moved from Łodz to Cracow, hoped to enliven Jewish artistic life in the city.34 However, already around 1907, the artistic

milieu centered around Hirszenberg dispersed. According to Liebeskind, “Young and talented enthusiasts found themselves revolutionists, pioneers, and priests of Jewish art. And it was true. Sometimes they treated Hirszenberg as the old one. They realized that his time had passed and his art was finished.”35

Hirszenberg’s influence, although temporary, had at that time crucial consequences for Gottlieb. First of all, he decided to commit himself to showing his works in exhibitions of Jewish art.36 In addition, in the autumn of 1906 Gottlieb travelled to Palestine together with his friend, the Polish sculptor Xawery Dunikowski (fig. 3), and stayed there for a few months as a teacher of painting

31 G.[ottlieb], “IX. Wystawa ‘Sztuki’,” 470–72. Gottlieb’s outlooks correspond closely with the ideas expressed by one of the most important personalities of the Young Poland movement, the writer and theoretician Stanisław Przybyszewski (1868–1927). He was a propagator of the early expressionism as well as a promoter of Edvard Munch’s art not only in Cracow circles; Stanisław Przybyszewski, Na drogach duszy: Edward Munch (On the Roads of the Soul: Edvard Munch), (Cracow, 1900), 51–52. Links between theories of Przybyszewski and Gottlieb’s early portraits were noted by Austrian art critic Arthur Roessler in his forward to the exhibition catalogue of the Group of Five: Kollektiv Ausstellung Krakauer Künstlerbund Grupa V. Bildhauer Lewandowski [catalogue, Kunstsalon Pisko, Vienna], forward Arthur Roessler (Vienna, 1908). Roessler, who discovered the talent of Egon Schiele a year later and became his protagonist, recognized Gottlieb as the most interesting artist of the group: “This young painter, president of the group, is a master in the artistic elaborating of the most characteristic expression of man’s face and palms. He doesn’t care about touching the borders of a caricature while confronting the stigmata of the spiritual pain [of his models]…”

32 The foremost propagators of Norwid’s work and thought were Zenon “Miriam” Przesmycki, Cezary Jellenta, and Stanisław Przybyszewski. “Zenon Przesmycki (...), a poet, essayist, translator, and publisher, contributed to this markedly. He rescued the manuscripts of Norwid’s works from oblivion and systematically published them in the periodical Chimera (1901–1907), of which he was publisher.” http://www.culture.pl/web/english/resources-visual-arts-full-page/-/eo_event_asset_publisher/eAN5/content/cyprian-norwid (accessed 25 Sept. 2012). Following critics and writers, artists of the Group of Five “treated Norwid as a link between [the] present day and Romanticism, as a ‘symbolist’ and a mystic, as well as a forerunner of the most contemporary tendencies in art”; Juszczak, Wojtkiewicz i nowa sztuka, 78–103. Gottlieb and his four friends intended to organize an exhibition of paintings, drawings, graphics, and sculptures by Norwid. The Group of Five was sometimes called the “Norwid” Group; “Wystawa dzieł Cypriana Norwida” (An Exhibition of Works by Cyprian Norwid), Czas 138 (1906): 3.

33 In addition to Gottlieb, among them were painters and sculptors: Abraham Neuman, Jerzy (George) Merkel, Henryk Kuna, and Henryk Hochman; critics: Emil Breiter and Seweryn Gottlieb; art promoters: Dr Józef Liebeskind and Dr Bernard Steinberg; an engineer: J.H. Löwenkron; and writers such as Szalom Asz (Shalom Asch). Members of the group who served as models for Gottlieb’s portraits included Abraham Neuman, Leon Hirszenberg, his brother Samuel with his wife, Henryk Kuna, Szalom Asz, and Efraim Mandelbaum. Gottlieb himself was portrayed by Samuel Hirszenberg in Spinoza (or Spinoza Excommunicated) (1907); see Richard I. Cohen and Mirjam Rajner, “The Return of the Wandering Jew(s) in Samuel Hirszenberg’s Art,” Ars Judaica 7 (2011): 48. If we follow Cohen and Rajner, who maintain that while painting Spinoza, Hirszenberg was “deeply disturbed by the clash between modernity and traditional Jewish life,” the date 1907 seems to have a twofold significance. The painting was one of the last made by Hirszenberg before leaving Cracow for Jerusalem during the same year in which Gottlieb came back from Palestine after only a few months. Was Hirszenberg disappointed that his former protégé left the Jewish circles of the Bezalel school in Jerusalem for cosmopolitan Europe? Is this what led him to choose Gottlieb as the model for Spinoza?

34 Henryk Weber, “Wystawa pamiatkowa Samuela Hirszenberga” (Com-memorative Exhibition of Samuel Hirszenberg), Nowy Dziennik 132 (1933): 8.

35 Józef Liebeskind, “Ze wspomnien o pobycie Samuela Hirszenberga w Krakowie” (Recollecting Samuel Hirszenberg’s Stay in Cracow), Nowy Dziennik 130 (1933): 8.

36 He showed his works in the “Exhibition of works offered on the lottery for victims of pogroms in Russia” organized by the Cracow Society of Friends of Fine Arts in May 1906. No later than 1907, together with more than 70 artists, Gottlieb participated in the exhibition of Jewish art in Berlin; Malinowski and Brus-Malinowska, W kregu École de Paris, 75. See also Austellung jüdischer Künstler [catalogue, Galerie für alte und neue Kunst, Berlin] (Berlin, 1907); Fragmented Mirror: Exhibition of Jewish Artists, Berlin, 1907 [catalogue, Tel Aviv Museum of Art] ed. Batsheva Goldman Ida (Tel Aviv, 2009).

Ar

s

Ju

da

ic

a

20

13

6

Artur Tanikowski

at the Bezalel School of Art in Jerusalem.37 This short interlude ended the following year and in 1907 Gottlieb was replaced at Bezalel by Samuel Hirszenberg himself.

The first ten years of Gottlieb’s artistic activity was a period of countless portrait-painting.38 Through portraits he was able to express not only the mood of the fin-de-

37 Gottlieb presumably replaced Julius Rothschild, a painter from Weimar, who was not accepted by Bezalel students. About Gottlieb’s trip to Jerusalem and teaching experience at Bezalel, see Izydor Lindenbaum, “Leopold Gottlieb a ‘Bezalel’” (Leopold Gottlieb and Bezalel) Wschód, 52/319 (1906): 2–4; Teslar, “O twórczosci malarskiej Leopolda Gottlieba”: 6; (h), “Leopold Gottlieb,” 4–5; Maksymilian Bienenstock, “W pracowni L. Gottlieba” (In L. Gottlieb’s studio), Chwila poniedziałkowa 28 (1922): 4; Weixlgärtner, “Leopold Gottlieb.” In the collection of Gottlieb’s letters written to his sister Inga (Róz.a) Jakimowicz, there are two sent

from Jerusalem and Jaffa in 1906 (collection of Bogdana Pilichowska-Ragno, Cracow). Both letters are described and quoted in Tanikowski, Wizerunki człowieczenstwa, 97. In 1906, in Jerusalem, Gottlieb executed the Portrait of Xawery Dunikowski, now in the collection of the Krzysztof Musiał (oil on canvas, 76 × 92 cm, signed and dated upper right: “Jerusalem L Gottlieb 906”), reproduced in ibid., color ill. no. 9.

38 It was confirmed by the artist himself while interviewed in his late years; see Roman Brandstaetter, “U Leopolda Gottlieba” (Visiting Leopold Gottlieb), Gazeta Polska 56 (1929).

Fig. 3. Portrait of Xawery Dunikowski, 1906, oil on canvas, 76 × 92 cm, collection of Krzysztof Musiał

Ar

s

Ju

da

ic

a

20

13

7

Toward the Philosophy of Work:The Late Paintings of Leopold Gottlieb

siècle period and his access to early expressionism, but also his cultural and national affiliation. Art critics valued Gottlieb’s portraits for their sophisticated, discrete, grey-green mode, their “original, cold and low palette, that introduces the very personal aura of each model.”39 They noted the linear and decorative rhythm of the portraits, their flatness and sketchy drawing, synthetic

and caricature-like formula of depicting the model, and their bravado and wit.40

Usually the model fills in the whole frame. The background is almost always depicted as an abstract surface, suggesting the very shallow space around the model. His silhouette is shown in an asymmetric, passive, and motionless pose. The whole expression is

39 St.[anisław] Roman Lewandowski, “Grupa pieciu i Lewandowski” (The Group of Five and Lewandowski), Tygodnik Ilustrowany 8 (1908): 159–60; Jan Piotrowski, “Młoda sztuka polska” (Young Polish Art), Wedrowiec 24 (1906): 455–56.

40 Roman Zrebowicz, “Polskie metamorfozy malarskie” (Metamorphosies of Polish Painting), Express Poranny 165 (1935); Adolf Basler, “Paryski Salon Jesienny. II” (Autumn Salon in Paris, part 2), Literatura i Sztuka 34 (1908): 3.

Fig. 4. Self-portrait, 1908, oil on canvas, 74 × 59 cm, Tel Aviv Museum of Art

Ar

s

Ju

da

ic

a

20

13

8

Artur Tanikowski

concentrated around the mimicry of models’ faces and gesture of hands.41 In the virtual gallery of Gottlieb’s early portraits, there is a very special place for Self-portrait (1908, Tel Aviv Museum of Art) (fig. 4) and Self-portrait in a Visionary Trance (1907, photography in the National

Digital Archives in Warsaw) because of their author’s deep and touching self-introspection.42 By portraying his Jewish companions from the Cracow circle of Samuel Hirszenberg (fig. 5) as well as his own family members, Gottlieb declared his national belonging.43

41 Thus we can enlist Study for the Portrait of a Bearded Man (ca. 1903–4) and Portrait of Rembrandt Bugatti (1904) – both reproduced in Sztuka 8-9 (1904); Portrait of a Man in the Fur Cap (1906, Ein Harod Museum of Art); Portrait of Mieczysław Jakimowicz (1907, National Museum in Warsaw); Portrait of Wacław Borowski (ca. 1910, National Museum in Warsaw), among others. Rembrandt Bugatti was an Italian sculptor and Gottlieb’s neighbour in Montparnasse. Both Mieczysław Jakimowicz and Wacław Borowski were Polish painters who befriended Gottlieb in Cracow and Paris.

42 Susan Tumarkin Goodman explores social and cultural fundamentals of Jewish artists making their self-representations: “A formal self-portrait

is an autobiography, created for various motives, and invariably relates to an inner self-examination on the part of the artist. Professional considerations, aesthetic orientation, character traits, or the lust for fame may enter into its making”; Susan Tumarkin Goodman, “Reshaping Jewish Identity in Art,” in The Emergence of Jewish Artists in Nineteenth-Century Europe [catalogue, Jewish Museum, New York], ed. Susan Tumarkin Goodman (New York, 2001), 22.

43 The meaning of portraits of Sholem Asch (1911, Ein Harod Museum of Art), Abraham Neuman (ca. 1905–6, present location unknown), and Felicja Gottlieb –the artist’s mother (1910, Israel Museum, Jerusalem) was deepened by using a Hebrew inscription in the background

Fig. 5. Portrait of Sholem Asch, 1911, distemper on canvas, 110 ×110 cm, Ein Harod Museum of Art

Ar

s

Ju

da

ic

a

20

13

9

Toward the Philosophy of Work:The Late Paintings of Leopold Gottlieb

Back in Europe, Gottlieb decided to travel to Paris for the second time. Around 1908 he took up residence in Montparnasse and by doing so enriched both the international Paris school of art as well as the local Polish colony.44 In 1912 Gottlieb participated in one of the

most significant exhibitions of “Polish Parisians” at the Galeries Josep Dalmau in Barcelona.45 After travelling to Barcelona for the opening, later the same year he went to Toledo (fig. 6), together with Mexican artists Diego Rivera and his companions whom he befriended.46

behind the model. I discuss the context and significance of Hebrew inscriptions used by Gottlieb in his portraits of in my book Wizerunki człowieczenstwa, rytuały powszedniosci, 137–45.

44 Among his friends were Maria Melania Mutermilch (Mela Muter), Eugeniusz Zak, Moj.zesz (Moïse) Kisling, Elie Nadelman, and Louis Marcoussis, Jewish artists from Poland, and Polish artists Olga Boznanska, Mieczysław Jakimowicz, Jan Rubczak, and Gustaw Gwozdecki. For some time, Gottlieb lived in the same building at 3 Rue Joseph-Bara, along with such famous personages of Montparnasse as Amedeo Modigliani, Jules Pascin, Leopold Zborowski, and Per Krohg.

45 He came to the Catalan capital together with Elie Nadelman, Witold

Gordon (Jurgielewicza), Mela Muter, and her husband, art critic Michał Mutermilch; Artur Tanikowski, “Heralds of Moderate Modernity: Polish-Jewish Artists in Catalonia,” in Jewish Artists and Central-Eastern Europe: Art Centers, Identity, Heritage from 19th Century to World War Two, eds. Jerzy Malinowski, Tamara Sztyma-Knasiecka, and Renata Piatkowska (Warsaw, 2008): 241–52. Although the most famous artist in Catalonia of all the Polish-Jewish-Parisian exhibitors was Mela Muter, the art of Leopold Gottlieb was also known to the Catalan art audience before the opening at Dalmau: “Leopold Gottlieb”, La Veu de Catalunya (3 April 1912): 4.

46 Rivera was accompanied by his fiancée, the Russian painter Angelina

Fig. 6. Vicinities of Toledo, 1912–13, oil on canvas, 80 ×100 cm, Ein Harod Museum of Art

Ar

s

Ju

da

ic

a

20

13

10

Artur Tanikowski

After settling in France, Gottlieb lightened and vivified his palette, which is clearly seen in the portraits

of befriended personalities from Montparnasse: André Salmon, Jules Pascin (both executed ca. 1908–10) (fig. 7), and Diego Rivera (1912).47 However while still involved in portrait painting, around 1910 Gottlieb developed his multi-figural scenes, mostly based on subjects from the New Testament.

At that time Gottlieb’s outlook on politics drew near to those of Polish socialists, who connected social awareness with the struggle for Polish independence. Following this trend, during 1912 and 1913 Gottlieb joined the secret Parisian branch of the Polish association called “Strzelec” (Rifleman).48 The training he received in their ranks soon proved to be very useful. After the outbreak of World War I, Gottlieb could have chosen a relatively secure life as an official imperial artist at the Austro-Hungarian press headquarters. However, he decided not to do so but rather to declare his Polish patriotism by enrolling, in autumn 1914, in Piłudski’s Polish Legions.49 He was one of the group of Jewish visual artists who, together with writers and intellectuals, took part in the fight for free and independent Poland in the period of the Great War (World War I).50

Petrovna Belova (Beloff) and another Mexican artist Ángel Zárraga (y) Argüelles. During the Toledo trip Gottlieb made the famous Portrait of Diego Rivera (distemper on canvas, 80 × 97 cm, signed lower left: “Leopold Gottlieb / Toledo”, collection of Museo Casa Diego Rivera, Guanajuato, Mexico); see Patrick Marnham, Dreaming with His Eyes Open: A Life of Diego Rivera (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 2000), 90–91. Next year, presumably together with Rivera, Gottlieb visited Mela Muter in Ondarroa, in the Basque country, Spain.

47 Portrait of André Salmon and Portrait of Jules Pascin are both in the collection of University Library in Torun. Portrait of Diego Rivera belongs to the Museo Casa Diego Rivera, Guanajuato, Mexico. Gottlieb’s models were often influential figures of international and Polish cultural, intellectual, and social life: Pablo Picasso, Edward Gordon Craig, Isadora Duncan, Artur Rubinstein, Henri Bergson, André Gide, Paul Valery, Mahatma Ghandi, Xawery Dunikowski, Henryk Kuna, Stefan Z

.eromski, Jan Kasprowicz, and Kornel Makuszynski.

48 “Strzelec” was a Polish paramilitary, cultural, and educational organization established in 1910 in Lwów . An important part of the Association's mission was training young Poles in military skills. There were several Polish and Polish-Jewish artists and writers active in “Strzelec” together with Gottlieb: Leon Chwistek, Mojz.esz Kisling, Włodzimierz Konieczny, Xawery Dunikowski, Louis Marcoussis, Stanisław Rzecki, Władysław Skoczylas, Bolesław Wieniawa-Długoszowski, and Jan Z

.yznowski, among others; see Wacława Milewska

and Maria Zientara, Sztuka Legionów Polskich i jej twórcy 1914–1918

(The Art and Artists of the Polish Legions between 1914 and 1918) (Cracow, 1999), 51–58.

49 After the outbreak of the war, there were two options for the immigrants residing in France who were citizens of the Austro-Hungarian Empire: either to leave for their native country or to enroll in the French Foreign Legion. While Dunikowski, Kisling, and Marcoussis chose the latter, Gottlieb, together with other “Strzelec” members, returned to Galicia as early as July 1914.However, there were numerous Jewish members of different branches of the “Strzelec” association, many of whom were mobilized by the Austrian army after the outbreak of hostilities. See Zygmunt Zygmuntowicz, “Z

.ydzi w Legionach Józefa Piłsudskiego” (Jews

in Józef Piłsudski’s Legion), in Z.ydzi bojownicy o niepodległosc Polski (Jews

in the Struggle for the Independence of Poland), ed. Norbert Getter, Jakub Schall, and Zygmunt Schipper (Lwów , 1939), reprinted in Z.ydzi polscy w słu.zbie Rzeczypospolitej (Polish Jews in the Service of the

Republic of Poland), vol. 1: 1918–1939, eds. Andrzej Krzysztof Kunert and Andrzej Przewoznik (Warsaw, 2002), 163–66.One of the Jewish legionaires was Zygmunt Bronisław Goldschlag, Gottlieb’s nephew; ibid., 258. There were ca. 170 artists among Piłsudski’s legionaries; Milewska and Zientara, Sztuka LegionówPolskich, 94–107.

50 Zygmunt Zygmuntowicz, “Z.ydzi w Legionach Józefa Piłsudskiego” (Jews

in Józef Piłsudski’s Legions), in Z.ydzi bojownicy o niepodległosc Polski

(Jewish Fighters for Poland’s Independence), eds. Norbert Getter, Jakub Schall, and Zygmunt Schipper (Lwów , 1939), reprinted in Z

.ydzi polscy

w słu.zbie Rzeczypospolitej, vol. 1: 1918–1939 (Polish Jews on Duty for the

Fig. 7. Portrait of the Painter Jules Pascin, ca. 1908–10, oil on canvas,

105 × 105 cm, University Library in Torun

Ar

s

Ju

da

ic

a

20

13

11

Toward the Philosophy of Work:The Late Paintings of Leopold Gottlieb

He participated in the Legion’s fiercest battles and clashes and soon became the most eminent Legion artist as well as the portraitist of Brigadier Piłsudski.51 In July 1916 Gottlieb was officially dispatched to Zurich to prepare an exhibition of the Polish Legion.52 While in Zurich, he created a portfolio of lithographs entitled Die polnischen Legionen.53

Gottlieb was an excellent frontline draughtsman, although his art practice at the time incorporated also graphic art, rarely painting, and photography as well as, probably, the moving-image camera.54 He depicted not only Legion leaders and officers, but also privates and line soldiers (fig. 8). He presented battlefields and scenes behind the front lines, soldiers’ everyday life, and funeral

ceremonies.55 The directness of his style impressed the viewer, but his manner has never been conventionally academic.

Particularly in graphic works, especially those depicting group scenes, Gottlieb could be recognized as a precursor of the Polish post-war avant-garde movements, such as formism. As an example of this we can mention In the Way to the Trenches (1916, lithography) (fig. 9), which marked a compositional model for several of Gottlieb’s post-war works. Its modern, neo-primitive form is fused together with an isocephalism – a popular formula of ancient art, especially relief. Its rhythmical narration as well as the oval outlines of the figures presage future paintings and drawings presenting agricultural subjects,

Republic of Poland), eds. Andrzej K. Kunert and Andrzej Przewoznik (Warsaw, 2002), 163–66.

51 There were approximately 170 artists – painters, sculptors, and graphic engravers – among the Piłusdski Legionaries; Milewska and Zientara, Sztuka Legionów Polskich, 94–107.

52 The exhibition “Kriegsbilder Ausstellung des K. u K. Kriegspressquartiers: Kriegsbilder der Polnischen Legionen” was open from 22 June to 9 July 1916. Later it was moved from Zurich to BaselWW and Bern. In the following year Gottlieb again travelled to Zurich to organize the next

exhibition of the Polish Legion; ibid., 351, 355.53 A portfolio of 24 color prints was published by the Zurich workshop of

J.E. Wolfensberger.54 Gottlieb as a cameraman is mentioned by one of his comrades in arms;

see Roman Starzyunski, Cztery lata wojny w słu.zbie Komendanta: Prze.zycia wojenne 1914–1918 (Four Years of War on Duty of a Commander: War Experiences 1914–18) (Warsaw, 1937), 173.

55 Gottlieb’s art critics attributed ca. 1000 portraits to him, possibly executed by Gottlieb during his service in the Legion; Wacław

Fig. 8. Wódz – Józef Piłsudski (Commander Józef Piłsudski), 1916,

lithography on paper, 33.5 × 26 cm, National Library in Warsaw

<

Fig. 9. On the Way to the Trenches, 1916, lithography on paper, 24.5 × 38 cm,

National Library in Warsaw<

Ar

s

Ju

da

ic

a

20

13

12

Artur Tanikowski

i.e., Harvest (1921, drawing) and Harvest –Work in the Fields no. 2 (1926, painting) (fig. 11 10?).56

Recovering from the war, in 1918 and 1919 Gottlieb twice visited the town of Zakopane, in the Polish Tatra mountains. Most likely he resided in the “Zawrat,” a guest house run by his sister Jadwiga (Inga). He participated in the opening of the Free School of Fine Arts there.57 However, the changing status of the town from one of the

leading Polish art centers of the time to a tourist resort, and the anti-Semitic atmosphere in Zakopane, especially noticeable under the administration of right-wing nationalists, caused him to leave Poland once again.58

Between 1920 and 1924 Gottlieb and his family lived in Vienna and Baden. Travelling from time to time to Lwów and Warsaw, he was an active participant in Polish artistic life. He exhibited his works together with the

Husarski, “Wystawy w IPS-ie. T. Czy.zewski – L. Gottlieb” (Exhibitions at IPS: Tytus Czy.zewski and Leopold Gottlieb), Czas 180 (1935). More than 200 of his drawings can be found nowadays in the collection of the National Museum in Cracow. There are also approximately 30 prints of the World War I period today in various collections as well as individual watercolors and oil paintings.

56 Both works from the collection of Krzysztof Musiał.57 “Wolna Szkoła Sztuk Pieknych” (Free School of Fine Arts), Zdrój no.

5 (1919): 112; ibid., nos. 1–2 (1920): 4; ibid., nos. 5–6 (1920): cover; Echo Tatrzanskie 20 (1919): 4.

58 Jarosław Skowranski, Tatry miedzywojenne (The Tatra Mountains Between the Wars) (Łódz, 2003), 19.

Fig. 10. Harvest – Work in the Fields no. 2, 1926, oil on canvas, 88 × 116.5 cm, collection of Krzysztof Musiał

Ar

s

Ju

da

ic

a

20

13

13

Toward the Philosophy of Work:The Late Paintings of Leopold Gottlieb

two groups of Polish mainstream artists of the late 1910s and 1920s: the Formists (Polish Expressionists) and the “Rytm” (Rhythm) Association.59

In 1924 or 1925, during the last decade of his life, Leopold Gottlieb once again returned to France. In spite of his prolonged absence, Paris was where he preferred to be. There he was acknowledged by the critics and appreciated by the art community and public.60 In March 1932 he was again in Cracow, participating in the commemoration of his brother Maurycy.61 At that time he was also invited to Germany to execute his only fresco paintings.62

Leopold Gottlieb died while at work in his Paris studio on 24 April 1934, at the age of 55, presumably from a heart attack. His funeral at the Thiais cemetery was attended by high-ranking Polish officials: the ambassador of the Polish Republic, Alfred Chłapowski, and the military attaché, Colonel Jerzy Błeszynski (whose two portraits were painted by Gottlieb). The participants honored the artist and the soldier, the Jew and the Pole.

Gottlieb’s Late Paintings, Their Meaning and Context After the war Gottlieb’s primary interest was in the icono-graphy of labor. The reasons for this are complex and combine various factors, the most important and decisive

being his social sensibility. Moreover, as noted, at that time the idea of social solidarity was also reflected in his narrative compositions related to New Testament themes.

Gottlieb’s social sensibility was shaped in close connection with the Cracow artistic milieu at the turn of the twentieth century. A number of students at Cracow’s School of Fine Arts with whom he associated belonged to “Zjednoczenie” (Consolidation), the “Society of Progressive Youth,” which had a clear leftist orientation. Its magazine Młodosc (Youth) was illustrated by Wojciech Weiss and Xawery Dunikowski, with whom Gottlieb was well acquainted. His friendship with Dunikowski, exemplified by their joint journey to Palestine in 1906, was particularly significant.63 Many members of Cracow’s artistic circles sympathized with the Polish Social-Democratic Party. That party’s satirical magazine, Liberum Veto, was illustrated by another group of Gottlieb’s friends, already acknowledged or soon to be acclaimed artists such as Witold Wojtkiewicz, Stanisław Szreniawa-Rzecki, Tymon Niesiołowski, Ludwik Markus (Louis Marcoussis), and Karol Frycz.

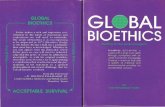

Gottlieb’s poster Sztuka (Art), probably the only one he ever designed, reveals his social orientation and political beliefs during this early period (fig. 11). It was executed in 1904 in Paris to advertise the artistic monthly Sztuka,

59 The group of Polish Expressionists, who later called themselves Formists, was active between 1917 and 1922. It united various artists and art theoreticians who had campaigned for the renewal of Polish art, based on popular art as well as on the achievements of modern movements such as Cubism, Expressionism, and Futurism. The group included Tytus Czy.zewski, Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz (Witkacy), Leon Chwistek, the brothers Zbigniew and Andrzej Pronaszko, and August Zamoyski, among others. At the beginning of their activity they invited some of their Parisian friends to cooperate and co-exhibit: Leopold Gottlieb, Eugeniusz Zak, Louis Marcoussis, and Moj.zesz Kisling. Gottlieb had met some of the future Formists in Paris before the war or later in Zakopane. Like the Formists, the Association of the Polish Artists “Rhythm” (1922–32) did not create a coherent aesthetic program. They appealed to the neoclassical order and decorative formulas of Maurice Denis, as well as to the craftsmanship of old masters based on infallible drawing skills. Artists such as Wacław Borowski, Władysław Skoczylas, Eugeniusz Zak, Roman Kramsztyk, Zofia Stryjenska, Henryk Kuna, Leopold Gottlieb, and Tymon Niesiołowski, among others, were inspired by works of classical tradition (from Greek and Roman antiquity, through Renaissance, and on to the Neoclassicism of the nineteenth century)

and by the Polish folk art and pre-Christian legends.60 His first Parisian one-man show was organized in October 1927 in the

Galerie Aux Quatre Chemins. A month later André Salmon published a monograph about him. In 1928 he was chosen as a member of the board of the Society of Artistic Exchange between Poland and France. In 1933 the Musée du Jeu de Paume acquired his painting Women Preparing the Meal.

61 Mendelsohn, Painting a People, 178–86.62 There is no clear evidence concerning this commission. Some authors

suggest that Gottlieb decorated interiors of the synagogue while others mention that he painted in the chapel of a sanitorium near Magdeburg; Roth, Die Kunst der Juden, 133; Artur Tanikowski, “Leopold Gottlieb,” in Colors of Identity: Polish Art from the American Collection of Tom Podl [catalogue, National Museum in Cracow], curators Anna Król and Artur Tanikowski (Cracow, 2002), 114.

63 Artur Tanikowski, “Portret podwójny z czasów młodosci. Leopold Gottlieb i Xawery Dunikowski” (The Dual Portrait from Youth: Leopold Gottlieb and Xawery Dunikowski), in Sztuka lat 1905–1923: Malarstwo – rzezba – grafika – krytyka artystyczna (Art between 1905–1923: Painting, Sculpture, Graphics, Art Criticism), eds. Małgorzata Geron and Jerzy Malinowski (Torun, 2006), 43–49.

Ar

s

Ju

da

ic

a

20

13

14

Artur Tanikowski

64 The painting, now lost, was shown at one of the exhibitions of the Vienna Sezession; see Józef Kozłowski, Proletariacka Młoda Polska: Sztuki plastyczne i ich twórcy w .zyciu proletariatu polskiego 1878–1914 (Proletariat Young Poland: Visual Arts and Their Authors in the Life of the Polish Proletariat 1878–1914) (Warsaw, 1986), 102.

published by Antoni Potocki in 1904 and 1905. The journal’s main aim was to promote European as well as Polish artistic modernity. In the style Gottlieb employed here, and especially in the use of the matte pastel colors, one can find a mixture of “Young Poland” symbolism and post-Nabis synthetism. The poster depicts a half-naked young man straining his body while pulling a rope and ringing a bell against the background of a townscape. The

banner title “Sztuka” suggests that the young bell-ringer is working hard to awaken the sleepy town’s inhabitants to modern art. However, the determination emanating from his strained brawn and dynamic pose could be connected to a goal on a scale broader than just art. It may be understood as the need for a general revolutionary change.

In his early years, Gottlieb was able to express his leftist sympathies more directly than could be done through the language of Symbolism. Already in 1901 he executed “a huge painting depicting workmen meeting around Ignacy Daszynski in Cracow’s Manège.”64 An eminent socialist activist, Ignacy Daszynski (1866–1936) was one of the co-founders of the Polish Social-Democratic Party (later Polish Socialist Party) and the first prime minister of the Second Polish Republic.One of Daszynski’s co-workers was the eminent author Stefan Z

.eromski (1864–1925),

whom Leopold Gottlieb befriended before World War I either in Zakopane or in Paris. Z

.eromski was involved

in Józef Pisłudski’s activity directed towards transforming the 1905 revolution into a Polish national uprising.65 It was Z

.eromski who could have acquainted young

Gottlieb with the ideas of the philosopher, sociologist, and psychologist Edward Abramowski (1868–1918). An informal leader of Polish anarchists and an apostle of the idea of cooperatives, Abramowski was also the author of the pioneering aesthetic theory of Early Expressionism in Polish modern art. At the same time, one has to remember that “regardless of their outlook, Polish socialists willingly made use of religious (or patriotic) symbols, rituals, and rhetoric.”66 Thus, although a relentless enemy of the Catholic Church, Abramowski found the message of the Christian faith to be one of the ideals of love, brotherhood, and equality.

The ideas of so-called socialist humanism, based on similar opinions, must have been close to those held by Gottlieb, the author of such canvases as Christ as a Beggar, Mercy (Christ and a SamaritanWoman), The Supper of

65 Both Z.eromski and Piłsudski were portrayed by Gottlieb.

66 Andrzej Chwalba, Sacrum i rewolucja: Socjalisci polscy wobec praktyk i symboli religijnych (1870 –1918) (Sacrum and Revolution: Polish Socialists Considering Religious Practices and Symbols, 1870–1918) (Cracow, 2007): note on the cover.

Fig. 11. Sztuka (Art), 1904, color lithograph on paper, 79 × 50 cm, Wilanów

Poster Museum

Ar

s

Ju

da

ic

a

20

13

15

Toward the Philosophy of Work:The Late Paintings of Leopold Gottlieb

Beggars, Composition (Mercy), and Pieta II (fig. 12). All of these were executed in Paris before World War I. In his New Testament paintings Gottlieb linked together elements inspired by current trends with traditional ones: Maurice Denis’s neo-traditionalism and new classicism of the early twentieth century with its modern decorative stylization of traditional clothes, rhythmical composition based sometimes on the Renaissance perspective, and pompous and sophisticated gestures coming from Mannerism.67 For his Christian paintings, Gottlieb was criticized by Jewish commentators as well as by Polish nationalists.68

The key to the proper understanding of Christological paintings executed by Gottlieb is connected with the alternative title of The Last Supper (1910, private collection), which was sometimes called Supper of Beggars. The deeply existential significance of this painting, as well as Christ as a Beggar (ca. 1908–10, University Library in Torun) is specified by superposition of two perspectives: the pivotal moment in the New Testament story and one of the most burning contemporary dramas: urban misery (fig. 13).69

The theme of misery has always been placed by Gottlieb in the context of religion, in a manner similar to that in the paintings of Mela Muter (Maria Melania Mutermilch)70 but in contrast to works by Eugene Zak, whose message has been based, rather, on criticism of modern civilization and expressed throughout his

67 There is no clear evidence that Gottlieb’s trip to Palestine strongly influenced his interest in the New Testament subjects, but we should not reject this too easily. In this context we should take note of Gottlieb’s journey to Spain – especially to Toledo – in 1912. At that time he was able to admire the religious paintings of El Greco (born Doménikos Theotokópoulos, 1541–1614), approved as one of the most important predecessors of the twentieth-century Expressionism. This issue is discussed in Tanikowski, Wizerunki człowieczenstwa, rytuały powszedniosci, 161–62; idem, Heralds of Moderate Modernity, 241–52.

68 [M. Goldstein?], “Z powodu wystawy Gottlieba Leopolda [Lwów, pazdziernik 1912]” (Because of Gottlieb’s Exhibition in Lwów , October 1912), Wschód 38 (1912): 5; Icchak Lichtenstein, “Leopold Gottlieb,” Literarishe Bleter 28a (1935): 1–2 (Yiddish); M. Hurajewicz, “O .zydach malarzach w sztuce polskiej” (On Jewish Painters in Polish Art), Ogniwo 1 (1921): 35.

Among Jewish artists born in Poland and other countries of eastern Europe who toyed with New Testament subjects were some contemporaries of Gottlieb: Marc Chagall, Samuel Hirszenberg, Henryk Glicenstein, Ephraim Moses Lilien, Artur Markowicz, Simon Mondzain, Mela Muter, and Wilhelm Wachtel. The subject of “Jewish Christ” is discussed by Ziva Amishai-Meisels, “The Jewish Jesus,” JJA 9 (1982): 83–104; eadem, “Origins of the Jewish Jesus,” in Complex Identities: Jewish Consciousness and Modern Art, eds. Matthew Baigell and Milly Heyd (New Brunswick, NJ and London, 2001), 51–86; eadem, “Chagall’s Dedicated to Christ: Sources and Meaning,” JA

21–22 (1995–96): 68–94; Artur Tanikowski, “Ukrzy.zowany w tałesie: Ikonografia chrystologiczna w sztuce Z

.ydów polskich i europejskich –

zarys problematyki” (Crucified in Tallit: Christological Iconography in the Art of Polish and European Jews), in Figury i figuracje (Figures and Figurations), eds. Małgorzata Kitowska-Łysiak, Ryszard Kasperowicz, Marcin Lachowski, and Lechosław Lamenski (Warsaw, 2006), 99–125 (Polish with English summary); idem, Malarze z.ydowscy w Polsce, cz. 1 (Jewish Painters in Poland, part 1) (Warsaw, 2006).

69 “In the foreground one can find a hectic vision – a strange supper. Christ, king of beggars, entertains all the poor and lonely. He himself like the poorest beggar without clothes, holds in his lap a sad strumpet, who is dying. All those being eaten by the city-monster: men without a future, sick, unhappy, and disabled, cuddle up to him”; Henryk Zbierzchowski, “Z pracowni artystów polskich w Pary.zu. I: Gottlieb i Jakimowicz” (From the Studios of Polish Artists in Paris, Part One: Gottlieb and Jakimowicz), Tygodnik Ilustrowany 35 (1910): 704.

70 Ursula Lazowski, “Images of Humanité: The Works of Mela Muter 1900–1930,” (MA thesis, Hunter College of the City University of New York, 1997); Barbara Brus-Malinowska, “O malarstwie Meli Muter” (On the Painting of Mela Muter), in Mela Muter (Maria Melania Mutermilch) 1876–1967:Kolekcja Bolesława i Liny Nawrockich (Mela Muter – Maria Melania Mutermilch 1876–1967: Collection of Bolesław and Lina Nawrocki) [catalogue, National Museum in Warsaw], eds. Barbara Brus-Malinowska and Bolesław Nawrocki (Warsaw, 1994), 24–25.

Fig. 12. Pieta II, 1909–10, oil on canvas, 146 ×114 cm, Israel Museum,

Jerusalem

Ar

s

Ju

da

ic

a

20

13

16

Artur Tanikowski

aesthetic and thematic escapism.71Although there were some formal and thematic similarities between Gottlieb and Zak, Gottlieb’s outlook on life and art stemmed primarily from his apologetic stand towards the world:

Gottlieb sings [his canticle] in honor of work and morality of work, let’s say after George Sorel: ‘morality of makers,’ morality of workers. [...] One has to relate [these paintings] to Cyprian Norwid’s ‘simplicity to be reached’ and to the fact that such a simplicity is the only sacrum and greatness that can be reached by the human being and the artist.72

Both names mentioned by Terlecki, the young Polish critic, while interpreting Gottlieb’s late painting, seem meaningful. As noted above, in 1905 Gottlieb and four of his Cracow friends, who established the “Group of Five,” chose as its patron Norwid, the poet, thinker, and graphic artist of late Romanticism. Although for many artists of the Young Poland movement Norwid was first and foremost only the renovator of a poetic phase, we could

71 Artur Tanikowski, Eugeniusz Zak (Sejny, 2003), 58 (Polish and English).72 Tymon Terlecki, “O sztuce malarskiej Leopolda Gottlieba” (On Leopold

Gottlieb’s Art of Painting), Sygnały 10–11, Lwów issues (1934): 25.

Fig. 13. Christ as a Beggar, ca. 1908–10, oil on canvas, 96 × 88 cm, University Library in Torun

Ar

s

Ju

da

ic

a

20

13

17

Toward the Philosophy of Work:The Late Paintings of Leopold Gottlieb

risk assuming that the case of Gottlieb was different. It transpired that, after 1918, for Gottlieb and his art the most important of Norwid’s achievements became precisely his philosophy of work.

Gottlieb had presumably acquainted himself with the poet’s philosophy of work by reading the extensive excerpts of Promethidion, Norwid’s tractate on art and work, published in 1904 in volume 8 of Chimera. In Promethidion

[the author] presented his program of “the new Prometheism,” based on the beauty of work and the work that endlessly creates beauty in everyday life, as opposed to the Prometheism of Romanticism that is based on apologetics of rebellion, struggle, and exceptional acts. A poem should contain reflection on the duty of art in social life. Norwid emphasizes a special meaning of fine arts connected to work, including crafts that introduce beauty to [the] everyday life of common people.73

In Norwid’s opinion, work and man were inseparable phenomena. Man would become more human through work. Norwid perceived the necessity of the rehabilitation of physical labor. Physical and mental efforts were inseparable in his concept of work: physical labor provides the worker with cognitive experiences and sensations. It generates not only material goods but also human thought, which is followed by culture. “Norwid has always seen work as linked to the desire for beauty. [...] Beauty, as well as an intellectual contribution to work, are identified with emotional experience.”74 With such a standpoint, it is easy to understand Gottlieb’s search for the individual aesthetics of work. As Józef Andrzej Teslar commented in his 1935 review of Gottlieb’s work:

Each and every composition executed by Gottlieb brings to mind a gallery of Degas’s “workers.” In these paintings Gottlieb incorporated the harmonized symphony of gestures and colors, based on a kind of elusive and unearthly whiteness. His scale of white-grey, white-green, and white-red compositions delights with the freshness and verity of mystical prayer.75

Norwid’s comprehension of work was highly appreciated by Stanisław Brzozowski (1878–1911). His own philosophy of work originated from the thought of Georges Sorel (1847–1922), the French philosopher and theorist of revolutionary syndicalism. For Brzozowski, “work became a starting point that has to begin all the philosophizing, because all around the world cogitation doesn’t find anything that is not a product of human labor.”76 The ideas of Brzozowski inspired both Poles and Jews, the two nations with which Gottlieb identified. Ten years after Poland regained its independence, Kazimierz Zakrzewski wrote: “By following Marshal Piłsudski the idea of action is transformed nowadays into the idea of work. There are no words more often repeated than the Marshal’s words on the contest of work. The idea of action, as well as the idea of work, stem from the philosophy of Brzozowski.”77 Gottlieb, who was Piłsudski’s most distinguished portraitist of the legionary period, became an adherent of the idea of action as a soldier-volunteer, and of the idea of labor as a painter.

Quite interestingly, the ideological, philosophical, and literary proposals of Brzozowski influenced first of all socialist Zionists, especially the Hashomer Hatzair movement.78 “One can say that Brzozowski participated in the transformations later known as the ‘Jewish

73 http://www.culture.pl/baza-sztuki-pelna-tresc/-/eo_event_asset_publisher/ eAN5/content/cyprian-norwid (accessed 26 July 2012).

74 Tadeusz W. Nowacki, “Filozofia pracy Cypriana Kamila Norwida” (Cyprian Kamil Norwid’s Philosophy of Work), Pedagogika Pracy 40 (2002): 20.

75 Teslar, “O twórczosci malarskiej Leopolda Gottlieba”: 6.76 Leszek Kołakowski, “Stanisław Brzozowski – polska filozofia pracy”

(Stanisław Brzozowski: Polish Philosophy of Work), in idem, Pochwała niekonsekwencji: Pisma rozproszone sprzed roku 1968 (Approval for

Inconsistency: Scattered Papers Written Before 1968), vol. 1, ed. Zbigniew Mentzel (London, 2002), 311–12.

77 Kazimierz Zakrzewski, Filozofia narodu, który walczy i pracuje (Philosophy of the Struggling and Working Nation) (Lwów , 1929); quoted from http://lewicowo.pl/filozofia-narodu-ktory-walczy-i-pracuje-nacjonalizm-stanislawa-brzozowskiego/ (accessed 26 July 2012).

78 Hashomer Hatzair (The Young Guard) was a socialist-Zionist movement founded in Galicia in 1913.

Ar

s

Ju

da

ic

a

20

13

18

Artur Tanikowski

revolution.’ [...] Members [of Hashomer Hatzair] [...] were Polish Jews and, as a matter of fact, Polish intellectuals. When leaving Poland, they knew Hebrew poorly or didn’t know it at all.”79 Mordechai Orenstein, one of Hashomer Hatzair’s leaders, recollected: “There were pages of Brzozowski’s Ideas that inculcated us with the enthusiasm for physical labor.”80 Brzozowski could have also influenced the doctrine of the leading Zionist thinker, Aaron David Gordon, whose motto was the “religion of work.”

Although we don’t have conclusive evidence, it is quite possible that Gottlieb became familiar with Gordon’s ideas through the article by Edmund Menachem Stein, entitled “Idea pracy w z.ydostwie” (The Concept of Work among Jewry). This text was published in the same issue of Miesiecznik Z

.ydowski (The Jewish Monthly) as Aurelia

Gottlieb’s article about Marc Chagall, and her husband must have read it.81 When analyzing the status of labor in different periods of Jewish history, Stein refers to the issues that indeed became subjects of paintings in Gottlieb’s late works: agricultural labor, crafts, and the “ideal woman – symbol of diligence.” Stein enhances the theological equivalence of work and rest: “When working and resting in proper time, we are becoming similar to God and we are coming closer to Him.”82 For his final statement Stein quoted Philo Judaeus of Alexandria: “Indeed, there is no less religion in work than work in religion.”83

Leopold Gottlieb’s attitudes to Zionism and its theoreticians are not unequivocal. In view of his wife,

Aurelia, who professed Zionism,84 his early connections to the Cracow circle of Samuel Hirszenberg, and his 1906 journey to Palestine, Gottlieb’s path to Zionism seemed to be a natural one. Actually, it was not. Upon leaving Jerusalem after just a few months and settling in Paris, Gottlieb became an artist of highly internationalized horizons, especially active in the Polish milieu. Moreover, he clearly declared himself a Polish patriot when volunteering to serve in Piłsudski’s Legions in 1914. Although upon his return to Paris around 1924 and 1925 Jewish critics noted that “the revival of Jewish Palestine fills him with deep enthusiasm,” Gottlieb was at that time renewing his international connections.85 Later, however, at the beginning of the 1930s, he and his wife indeed became active in Jewish circles, especially Zionist ones, but by then the motives were different: “They were both shocked by the events in Germany. Deeply moved by the fate of German Jews, they took part in the activities of the supporting committees.”86

One of Gottlieb’s last dreams, never to be realized, was to travel to Vilna and paint its Jews.87 His need to return to his Jewish roots had already been noted after World War I and was especially exemplified in 1922 when he executed works unknown today: Offering of Isaac, Moses in Front of the Burning Bush, and an illustration for Sh’ma Israel. In 1924 and 1933 he also painted two successive versions of Jews Praying (fig. 14).88 Significantly, Gottlieb's works connected to the traditions of Christianity reappeared about the same time as the paintings relating to Judaism.

79 Ryszard Löw, “Brzozowski wsród lektur syjonistycznych” (Brzozowski among Zionist Reading Materials), Teksty Drugie 6 (84) (2003): 157–58.

80 Mordechai Orenstein, “Akalkalot” (Winding Poads), in Sefer Ha-Shomrim: Antologiyah le-Yovel ha-XX shel ha-Shomer ha-Zair, 1913–1933 (The Book of the Guards: An Anthology for the Twentieth Anniversary of Hashomer Hatzair, 1913–1933) (Warsaw 1934), 103 (Hebrew).

81 Edmund Stein, “Idea pracy w z.ydostwie” (The Concept of Work among Jewry), Miesiecznik Z

.ydowski 11 (1931): 385–399.

82 Ibid.: 388.83 Ibid.84 According to Ludwik Oberlaender: “The artist held great reverence for

his wife. She had a strong influence on him as well as on his art. This influence strongly contributed to consolidate Gottlieb’s Jewish dignity”; Oberlaender, “Pamieci Leopolda Gottlieba”: 362–63.

85 M.W. [Michał Weinzieher], “Leopold Gottlieb,” Nasz Przeglad 119 (1934): 3.

86 Oberlaender, “Pamieci Leopolda Gottlieba”: 363–64.87 Michał Weinzieher, “Leopold Gottlieb: Z powodu posmiertnej wystawy

w I.P.S.-ie” (Leopold Gottlieb: On the Occasion of his Posthumous Exhibition at the I.P.S. Salon), Nasz Przeglad 178 (1935).

88 Modl acy sie Z.ydzi (Jews Praying), 1933 (oil on wood, 47×36 cm,

collection of Wojciech Fibak), reproduction in Polski Pary.z: École de Paris – kolekcja Wojciecha Fibaka (Polish Paris: École de Paris – Collection of Wojciech Fibak), [catalogue, National Museum in Szczecin], eds. Marta Poszumska and Donata Jaworska (Szczecin, 2000), 146. Modlacy sie Z

.ydzi II (Jews Praying, II), 1933 (oil on wood,

44×36 cm), current location unknown, photography in Collection of Iconography and Photography, National Museum in Warsaw, inventory no. DI 99682.

Ar

s

Ju

da

ic

a

20

13

19

Toward the Philosophy of Work:The Late Paintings of Leopold Gottlieb

Fig. 14. Jews Praying no. 2, 1933, oil on wood, 44 × 36, current location unknown,

photography in the Iconography and Photography Department, National Museum in Warsaw

Ar

s

Ju

da

ic

a

20

13

20

Artur Tanikowski

Between 1922 and 1931 Gottlieb painted two versions of Saint Sebastian: Everybody Bears His Own Cross and The Confession.89The strictly religious subjects undertaken by Gottlieb in his late period are proof of a kind of simultaneity. Maybe just because he lived in increasingly sombre times, the artist needed to remind himself of his dual Jewish-Polish identity.

The last decade of Gottlieb’s artistic activity also displays two different streams which clearly complement one another. It is possible to define them as “realistic” and “visionary.” The first group includes gouache or oil portraits and other works that expressed the artist’s desire for direct depiction of reality.90 However, much more impressive are the “visionary” paintings, often noted by critics for their “mystical timelessness.”91 Their main qualities are indeed a spiritual climate created by elegiac silence and soft rhythm that is combined with chromatic values, a fresco-like technique, and concentrated gestures of hieratically captured figures intensely dedicated to their activity. “All the fisherman, bakers, florists, and women selecting fish or preparing food and drinks, all of them are eternal human beings, not of yesterday, nor of today. They seem not to work but rather execute some kind of eternal rites with attention and joy.”92 Not only is it impossible to define the historical period to which those figures belong, but the cultural circle or geographical region of their origin as well. Thus, any direct association

of Gottlieb’s agrarian paintings and figures with the French province or the Palestinian kibbutz, as was done by Sotheby’s branch in Tel Aviv,93 leads to a dead end. Waldemar George, the well-known Parisian based Polish-Jewish art critic, when discussing Gottlieb’s images, has commented: “Their clothes are combinations of antique draperies and contemporary costumes. [...] When depicting a young countrywoman or Parisian workwoman, Gottlieb always idealizes their dress.”94 While some critics were able to compare Gottlieb’s figures of the so-called “everyday workers” to the ideals of ancient Greek sculpture,95 others found in them a connection to the heroes of biblical mysteries,96 while yet others wrote about their serene aura, which recalls that of Saint Francis of Assisi.

Some of Gottlieb’s paintings from the last five years of his life (1930–34) are based on the principle of simultaneous contrasts of colors and values, such as in his Painter in the Window, 1930.97 However, the main tendency of this artist is to focus on reducing the first (the colors) and to expand the latter (the values). Month after month his palette was becoming more whitened, sometimes in pastel tones and sometimes in tones of opalescence. Gottlieb used warm whites, glimmering whites, shiny whites – some of them pinkish, orange, cocoa, or beige – as well as more flat whites – more tarnished, glossless, bluish, greyish, or dingy. Such a palette is characteristic

89 Current whereabouts unknown. Works mentioned above were listed in the catalogue of Gottlieb’s posthumous exhibition in Warsaw: Wystawa prac Leopolda Gottlieba (Exhibition of Works by Leopold Gottlieb) [catalogue, Institute for the Propaganda of Art], texts: Juliusz Kaden-Bandrowski and Mieczysław Wallis (Warsaw, 1935), 23.

90 Among others, we can list: Portrait of a Boy (oil on cardboard, collection of the Signum Foundation, reproduced in Wybitni artysci z.ydowscy z kolekcji Davida Malka i Fundacji Signum (Eminent Jewish Artists from the Collections of David Malek and the Signum Foundation [catalogue, Museum of the City of Łódz], ed. Lucyna Skompska (Łódz, 2004), lot 37, p. 67; Portrait of Zofia Nalepinska-Bojczukowa (1927, private collection, reproduced in Tanikowski, Wizerunki człowieczenstwa, rytuały powszedniosci, color ill. 74); and Portrait of Lena (ca. 1931, private collection, reproduced in ibid., color ill. 70).

91 Nella Samotyhowa, “Leopold Gottlieb – Jacek Mierzejewski – Tytus Czyz.ewski: Wystawa Instytutu Prop. Sztuki” (Leopold Gottlieb – Jacek Mierzejewski – Tytus Czyz.ewski: Exhibition at the Intitute for the Propaganda of Art), Praca Obywatelska 12 (1935): 8.

92 Teslar, “O twórczosci malarskiej Leopolda Gottlieba,” 6.93 In 1993 Sotheby’s Tel Aviv’s branch offered a colored drawing executed

by Gottlieb in 1921, and gave it the title Kibbutzniks (watercolor and charcoal on paper, 40×29 cm, reproduction in Highly Important Judaica Books, Manuscripts, Works of Art and Paintings, auction catalogue of Sotheby’s, Tel Aviv, 15.04.1993, lot 53). There is no reason to accept such a title. Although the painter’s widow, who eventually became a Zionist, contributed to some of his posthumous exhibitions and its catalogues, there is no evidence of any similar title as the so-called “Kibbutzniks.”

94 Waldemar George, “Léopold Gottlieb ou le retour au theme,” Art et Déoration 62 (1933): 78–84.

95 Ibid.96 Zygmunt Stanisław Klingsland, “Malarstwo Leopolda Gottlieba” (The

Painting of Leopold Gottlieb), Wiadomosci Literackie 48 (1927): 2.97 Malarz w oknie (Painter in the Window), 1930 (oil on canvas,

92 × 73 cm), collection of Wojciech Fibak, reproduction in Polski Paryz., 149.

Ar

s

Ju

da

ic

a

20

13

21

Toward the Philosophy of Work:The Late Paintings of Leopold Gottlieb

98 Mleczarnia (Dairy), 1931–33 (oil on canvas, 87 × 88 cm), current location unknown, photography in Collection of Iconography and Photography, National Museum in Warsaw, inventory no. DI 99677; Trzy kobiety na drabinie (Three Women on a Ladder), 1932 (oil on canvas, 93 × 60 cm), collection of Wojciech Fibak, reproduction in

Polski Paryz., 148; Trzy kobiety III (Three Women no. 3), 1932 (oil and gouache on cardboard, 58,5 × 41 cm), private collection, reproduction in Colors of Identity (above, n. 62), 121; Ubieranie do slubu (Dressing for the Wedding), 1934 (oil on canvas, 100,5 × 82,5 cm), collection of Wojciech Fibak, reproduction in Polski Paryz., 153.

of paintings like Plasterers (1928) (fig. 15) and The Water-carrier (1929), as well as for some later works such as Portrait of a Boy and Portrait of Lena.

However, Gottlieb’s so-called white period was actually dominated by the depictions of women – working or resting, or shown in the most essential moment of their

femininity, the time of giving birth (figs. 16–17). The most important achievements of these series include Dairy (1931–33), Three Women on a Ladder (1932), Three Women no. 3 (1932) (fig. 18), and Dressing for the Wedding (1934).98 The usage of such nebular gradation of bright or broken tones, as well as the feminine subject, brought

Fig. 15. Plasterers, 1928, oil on cardboard, 98×69 cm, Ein Harod Museum of Art

Ar

s

Ju

da

ic

a

20

13

22

Artur Tanikowski

Fig. 16. Birth of a Child, ok. 1932, oil on canvas, 100 × 81 cm, Tel Aviv Museum of Art

Ar

s

Ju

da

ic

a

20

13

23

Toward the Philosophy of Work:The Late Paintings of Leopold Gottlieb

Fig. 17. Figures, 1932, oil on paper pasted to cardboard, collection of Marek Roefler, Villa la Fleur

Ar

s

Ju

da

ic

a

20

13

24

Artur Tanikowski

Fig. 18. Three Women no. 3, 1932, oil and gouache on cardboard, 58.5 × 41 cm, private collection

Ar

s

Ju

da

ic

a

20

13

25

Toward the Philosophy of Work:The Late Paintings of Leopold Gottlieb

Fig. 19. Coming Back from the Fields, 1928, gouache on paper, 51.5 × 33

cm, private collection

Gottlieb closer to another famous member of the École de Paris – Jules Pascin, whom he had probably already befriended in their Munich days. But the main difference between them is the manner in which they interpret the theme. While Gottlieb’s woman is presented with silent dignity, elevated by the white of her plain clothes, Pascin focuses on the erotic aura of her femininity, marked by whites and flesh shades of a more carnal quality.

Still, we cannot entirely neglect focusing on the historical and geographical context of Gottlieb’s late works. French culture of the 1930s was imbued with slogans like “return to order” (rappel à l’ordre), “return to man,” and last but not least, “return to the soil.” The last was an argument against urban civilization. According to the French nationalists, the metropolis had been “eating its own tail” and was responsible for the decline of French culture as well as the conservative system of values. Montparnasse was identified as the nest of evil with its countless “barbarians from the East,” mostly Jews.99 At the beginning of the 1930s the Paris Salons recorded the growing number of paintings presenting the profits and pleasures of country life. Their creators belonged to the new generation of artist-landowners representing the neoconservative rightist trend of the romantic idyll.100 This group included Robert Lotiron, Roland Oudot, and Gérard Cochet, whose works answered the slogan of “the return to the true France.” Far removed from their naïve regionalism, Gottlieb in his later years was much closer to painters like Marcel Gromaire, who was able to portray “a

99 On the anti-Semitic campaign in French art criticism of the late 1920s and 1930s, see Romy Golan, “The Ecole Française vs. Ecole de Paris: The Debate about the Status of Jewish Artists in Paris between the Wars,” in The Circle of Montparnasse: Jewish Artists in Paris 1905–1945 [catalogue, The Jewish Museum, New York], eds. Kenneth E. Silver and Romy Golan (New York, 1985), 80–87; see also idem, Modernity and Nostalgia: Art and Politics in France between the Wars (New Haven and London, 1995): 45–46; Artur Tanikowski, Malarze z.ydowscy w Polsce (Jewish Painters in Poland), vol. 1 (Warsaw, 2006), 91; Anna Wierzbicka, We Francji i w Polsce: Sztuka, jej historyczne uwarunkowania i odbiór w swietle krytyków polsko-francuskich (In France and in Poland: Art, Its Subjection to History and Its Reception in the Light of Polish-French Critics) (Warsaw, 2009), 293–316 (Polish with French summaries).

100 The so-called agrarian discourse is discussed by Golan, Modernity and Nostalgia, 23–60.

Fig. 20. Rest, 1926, watercolor and chalk on paper, 33.5 × 35 cm,

collection of Marek Roefler, Villa la Fleur

Ar

s

Ju

da

ic

a