Tong Meng Hui, Visual Self-Representation of the Chinese and the Birth of Chinese Cartoons in Early...

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

3 -

download

0

Transcript of Tong Meng Hui, Visual Self-Representation of the Chinese and the Birth of Chinese Cartoons in Early...

180 圆切线 第六卷 • 第二期 • 二○○七年 TANGENT Vol. 6 • No. 2 • 2007

Tong Meng Hui, Visual Self-Representations of the Chinese and the Birth of Chinese Cartoons in Early Twentieth Century Singapore1

Lim Cheng Tju

Introduction

2006 marks the centenary of the birth of Tong Meng Hui, or Chinese Revolution-ary Alliance, in Singapore.2 Founded by Sun Yat Sen in Japan in January 1905, Tong Meng Hui was a revolutionary organisation dedicated to the overthrow of the Qing Dynasty in China. (Hsu 1990: 454 and 463) The Singapore chapter, founded on April 6, 1906, was the Southeast Asian headquarters of the alliance.

Much has been written about the role of the overseas Chinese, especially those in Singapore, as the “mother of the revolution” that led to the eventual demise of Manchu rule in 1911.3 What is lesser known is the role played by the Tong Meng Hui in the birth of the first Chinese cartoons to be printed in Singapore.

This paper will examine the context and production of these early cartoons in Singapore in relation to Tong Meng Hui and its later incarnation, the Kuomintang (Nationalist Party). These cartoons are also fascinating in the insights they provide in the way the Chinese portray themselves in drawn images such as cartoons. The nature of the visual self-representations of the overseas Chinese in early 20th Century Singapore is the second focus of this paper.4

At the turn of the 20th Century, Singapore was at the nexus of Eastern and Western ideas and influences with news of political events from China or Europe

1 I would like to pay tribute to the pioneering works of Yeo Man Thong, Li Qing Nian and Foo

Kwee Horng in the documenting the early history of Chinese cartoons in Singapore.2

See The Straits Times, 8 and 13 June 2006.3

See the following publications: Yen (1976), Yen (1978) and Lee (1987). For a historiographical discussion of the writing of Tong Meng Hui’s history, see Huang (2006).4

For a comparison of how overseas Chinese elsewhere represent themselves in images, see Yu (1992).

Visual Self-Representations of the Chinese and the Birth of Chinese Cartoons 181

being communicated rapidly through wire agencies and newspapers that created an impact on local life. (Chen 1991: 289) In 1907, events in China and Japan “conspired” to produce the first Chinese cartoon in Singapore at a very specific point of time.

1907−1908: The Image of the Political Sojourner in Chong Shing Yit Pao

The story of Chinese cartoons in Singapore began with the setting up of Chong Shing Jit Pao in 1907 by members of the Singapore branch of the Tong Meng Hui. (Chen 1967: 97) The advent of mass media, new printing technology and revolutionary interests coincide to introduce cartoons to the Chinese immigrant population of Singapore on a mass base. It was political forces rather than commercial or cultural ones that brought satirical images into Chinese newspapers of Singapore — revolutionary conditions that did not come sooner than 1907. It was with the emergence of radical politics and revolutionary newspapers in Singapore, namely Chong Shing Yit Pao, that Chinese cartoons came into being.

Chong Shing Yit Pao (1907–1910) was the organ of the Singapore Tong Meng Hui and the successor to the first Chinese revolutionary paper in Singapore, Thoe Nam Jit Poh (1904–1905). While the older Chinese press in Singapore like Lat Pau (1881–1932) sat on the fence with regards to the new Chinese politics and preferred to stick to its traditional role of providing leisure news to the privileged, the radical press took an active role in pursuing its revolutionary cause. (Ibid.: 130)

Unlike earlier reformist papers, the revolutionaries saw the potential of cartoons in getting their message across to the public. Their aims and ways were not the evolutionary process of reforms in education but revolution in arms, words and deeds.5 The mass media, words and pictures, was meant to serve the propaganda purposes of Sun Yat Sen’s vision for a new China.6

5 These revolutionary journalists were men of action. Three writers from another pro-revolutionary paper, the Sin Chew Morning Paper (1909–1910), returned to Canton in China to participate in the historic uprising in 1911 and were counted among the 72 Huang Hua Kiang heroes. (Chen 1991: 293)6 Sun’s sojourn in Singapore has received much attention in the last few years with the re-opening of the Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall and a highly-publicised play, One Hundred Years in Waiting performed at the Singapore Arts Festival 2001. The memorial hall was granted the status of being a national monument of Singapore. See “New Phase for Chinese in Singapore,” The Straits Times, 1 December 2001.

182 Lim Cheng Tju

Chong Shing Yit Pao started publication on 20 August 1907 as a result of Sun Yat Sen launching the Singapore Tong Meng Hui the previous year. The proprietors of the paper, Tan Chor Lam and Teo Eng Hock were elected chairman and vice-chairman of the Singapore branch respectively.7 (Ibid.: 97) They were serious self-styled revolutionaries who had lost about $30,000 in their previous venture, Thoe Nam Jit Poh.8 (Ibid.: 130) Now with the Singapore Tong Meng Hui in place, they constructed another paper as the mouthpiece of the revolutionary organisation.

Tan and Teo were neither scholars nor writers and Thoe Nam Jit Poh suffered from staffing problems as there was no official revolutionary body in Singapore then to coordinate the movement.9 But in 1907, Chong Shing Yit Pao had the full support of the new organization, including articles written by Sun Yat Sen under a pen-name.10 (Ibid.: 97) The fact that Sun was involved in Chong Shing Yit Pao explains why Chinese cartoons first appeared there and not in the pages of Thoe Nam Jit Poh. The latter had difficulty in finding writers, much less cartoonists to draw for them. Chong Shing Yit Poh could also be more aware of the revolutionary potential of cartoons as the Tong Meng Hui in Japan was publishing the subversive Min Pao (People’ s Journal ), which contained many anti-Qing Dynasty cartoons.

For example, a 1907 cartoon entitled “Heaven Condemns” depicted high-ranking Chinese officials working for the Qing government as snakes or fish. (Lent 1994: 282; Wang 1999: 10–11) (Figure 1) Similar visual attacks on Chinese traitors would recur in the cartoons of Chong Shing Yit Pao. (Figure 2)

It was very possible that the revolutionaries in Singapore had access to issues of Min Pao as 7000 copies were being printed and distributed to China and overseas Chinese communities.(Bergere 1998: 156) Furthermore, the “Heaven Condemns” Min Pao cartoons were reprinted in the China Daily News, the organ for Tong

7 Teo’s nephew, Lim Nee Soon, the rubber magnate, was also a financial supporter of Thoe Nam Jit

Poh and Chong Shing Yit Poh. (Turnbull 1989: 108; Singapore Press Holdings Limited 1993: 25)8 The paper was distributed free to attract readers and free calendars and gift vouchers were also given out. Tan also sold his house to start the paper to pursue the cause of the revolution. (Singa-pore Press Holdings Limited 1993: 81) However the paper only had a circulation of 30. (Turnbull 1989: 109)9 The Tong Meng Hui was only established in Tokyo in 1905. Thoe Nam Jit Poh was set up in 1904.10 Sun used the pen-name of ‘Nanyang Hsiao Hsueh Sheng’ (a young student of Nanyang). Funding of the paper was raised by the Tong Meng Hui and it was considered the strongest revolutionary paper in the region then due to the support given to it by Sun. (Singapore Press Holdings Limited 1993: 81)

Visual Self-Representations of the Chinese and the Birth of Chinese Cartoons 183

Meng Hui in Hong Kong. (Wong and Yeung 1999: 14–15) The editors of Chong Shing Yit Pao could have seen the cartoons from the China Daily News as well.

Fig. 1 ‘Heaven Condemns’. Min Pao, 1907

Fig. 2 ‘Corrupt Ching Officials’. Chong Shing Yit Pao, 1907

The initial cartoon appeared in the literary page (“Fei Fei”) of Chong Shing Yit Pao on 9 September 1907, the first time a Chinese newspaper in Singapore carried pictorials other than those in advertisements. (Chen 1967: 98–99) (Figure 3) A total of 41 cartoons were published from then until 21 March 1908, when

184 Lim Cheng Tju

the cartoons were dropped possibly, as a result of a change in editorship. Yeo Man Thong has suggested that the disappearance of cartoons could be due to a lack of cartooning talents to continue drawing for the paper.11

Fig. 3

With the exception of two works, none of the cartoons were signed, possibly to avoid persecution from the Qing Dynasty and the colonial government in Sin-gapore. Indeed, in 1908, the British threatened to use the Banishment Ordinance to deport Sun Yat Sen and the editors of the paper for advocating “seditious agitation against China”. (Yong 1991: 31) Such acts had their precedence in the rest of the British Empire in the Far East — in August 1907, the British govern-ment in Hong Kong censored the China Daily News for reprinting the “Heaven Condemns” Min Pao cartoons. (Wong and Yeung 1999: 15) Such news would have spread to other Tong Meng Hui branches in Asia, including Singapore, and suggest to the cartoonist or cartoonists that they take precautions.

The two identified cartoons were drawn by a well-known May 4th Move-ment cartoonist, Ma Xingchi (1873–1934). (Figures 4 and 5) A native of the Shangdong province, Ma studied art in Beijing and Shanghai before following Sun overseas to pursue his revolutionary activities. (Bi 1998: 12) It is very possible that he was in Singapore together with Sun between 1907 and 1908 and drew cartoons for Chong Shing Yit Pao. Ma was believed to have invented a particular style of drawing by piecing together different Chinese characters to create hidden meanings in his cartoons. Many of the other uncredited cartoons in Chong Shing

11 The new editor, Tian Tong took over the reins of Chong Shing Yit Pao on March 1908. (Yeo

1995: 83)

Visual Self-Representations of the Chinese and the Birth of Chinese Cartoons 185

12 Ma’s connection with Chong Shing Yit Pao was pointed to me by Foo Kwee Horng.

Fig. 4

Fig. 5

Yit Pao using a similar technique could have been drawn by him.12 (Gao 1998: 33) Ma returned to China by 1910, taking up the editorship of the China Picto-rial Weekly in Shanghai, which printed his first well-known cartoon. (Bi 1998: 12) He went on to draw other seminal cartoons during the May 4th Movement of 1919, but his work for Chong Shing Yit Pao remained a footnote in Chinese cartooning history today.

186 Lim Cheng Tju

As shown above, the appearance of Chinese cartoons in Singapore was not accidental, but a deliberate effort on the part of Chong Shing Yit Pao to use car-toons as a tool for agitation against the Qing government in China. In intention and aesthetics, Chinese cartoons in Singapore were geared towards shaping the mindset of its readers with regards to the tyranny of the Qing Dynasty.

The cartoons’ subject matters never strayed far from the tumultuous changes happening in China’s political scene in the 1900s. Attempts to engage local mer-chants were reflected in the cartoons depicting the restrictions the Qing government placed on the trade of the overseas Chinese, especially the high taxes imposed by the Manchus. (Figure 6) These cartoons were obviously meant to rouse anti-Qing sentiments among the Chinese population in Singapore and sway them to the revolutionary cause of the Tong Meng Hui.

Fig. 6

Content was more important than form in these cartoons, which unlike today’s premium on humor, these were hardly funny at all. There were layers to some of the works in Chong Shing Yit Pao, incorporating clever use of wordplay. But their messaging was always very direct and biting. Getting the point across to the masses in the most effective way was paramount and there was no room for subtlety.13

However Chong Shing Yit Pao’s actual influence on the Chinese population is debatable as it had a circulation of only 1000 copies. This was better than Lat Pau’s 550 but its main ideological competitor, the progressive oriented The

13 This is common for Chinese cartoons when depicting times of crisis. (Hung, 1994: 97–98)

Visual Self-Representations of the Chinese and the Birth of Chinese Cartoons 187

Union Times had a circulation of 1060. (Cui 1993: 68) These figures are nowhere near the actual number of the Chinese population in Singapore. In 1911, the Chinese population had reached a number of 219, 577. Yeo Man Thong argued that the Chong Shing Yit Pao cartoons were important in educating the illiterate and influencing their opinions about the political situation in China. (Yeo 1995: 82) However a careful study of the cartoons showed that it employed the usage of many Chinese words and phrases, indicating that the target audience of the cartoons needed to possess some level of street literacy in Chinese to understand the cartoons. A more possible explanation is that they were meant for people with rudimentary literacy. As pointed out by Cui Gui Qiang, the readers and supporters of Chong Shing Yit Pao were small time businessmen and intellectuals. It was unlikely that the coolies and laborers had the ability or time to read the newspaper. Their ideological education was through speeches and talks and not the print medium. (Cui 1993: 70–71)

The cartoons in Chong Shing Yit Pao could be perceived as crudely drawn by today’s standards, but they defined the propagandistic role Chinese cartoons would play in Singapore.14 Thus visual representations of the Chinese by them-selves during this time in Singapore were framed in political terms. The image they have of themselves was one of a sojourner, whose concerns were with the political problems in China. They did not perceive themselves as mere victims of circumstances or exploitation (in contrast to the images of the Chinese in America drawn by Westerners15), but while these images acknowledged their plight, there were also means to empower themselves and influence others to do something about their dreary conditions.

Although Chong Shing Yit Pao stopped running cartoons in early 1908, it did pave the way for other Chinese papers to print cartoons in its pages. The reformist newspaper, The Union Times (1906–1948) ran its first cartoon on 29 July 1909, reprinting a satirical cartoon from China. Even the conservative Lat Pau reprinted a cartoon critical of the Qing government from a London newspaper.16 (Li 1996: 21) However the appearance of cartoons in these newspapers was not

14 In the early 20th Century, the term propaganda did not carry such negative connotations as today.

In China, cartoons drawn in the service of propaganda to rally the masses against foreign aggression and imperialism were seen as positive. Even in the West, it was only with the advent of World War One that propaganda art was seen as negative. (Clarke 1997: 7) 15

See Choy, Dong and Horn (1995), and Kuo (1999).16

Li (1996) in his article on the origins of Chinese cartoons in Singapore also mentioned that cartoons appeared in the following newspapers: Sin Chew Morning Paper (1909–1910), Nam Kew Poo (1911–1914), Kuo Min Yit Poh (1914–1919) and Sin Kuo Min Press (1919–1939). (21)

188 Lim Cheng Tju

regular due to two possible reasons. One could be that there was no demand for cartoons from the readership of these papers. The other more probable reason was the lack of cartooning talent in Singapore. The first commercial art school in Singapore was set up in 1906, but it had a small very enrollment. In 1908, it had only 8 graduates — five Chinese and three Europeans. (Yeo 1995: 82) Thus it makes sense that the first known Chinese cartoonist to work in Singapore, Ma Xingchi was a sojourner from China and newspapers like The Union Times and Lat Pau had to reprint cartoons from overseas.

1914–1918: ‘US VERSUS THEM’ IN KUO MIN YIT POH

Chinese politics continued to dominate the content of the Chinese cartoons in Singapore. After the fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1911, the new Republic was threatened by the imperial ambition of a former Manchu general, Yuan Shih Kai, who fancied thoughts of reviving dynastic rule in China. (Hsu 1990: 478) Pro-democratic elements in the new Republican government and newspapers con-demned his actions. Opposition was particularly strong in Shanghai and Yuan was lampooned regularly in the newspaper cartoons. On 20 August 1913, a collection of these anti-Yuan cartoons was compiled and published in book form, possibly the first cartoon book in China. Pictorial History of Yuan Shih Kai’s Government was edited by Qian Bing He, who also drew most of the cartoons in the 16-page book. (Wang 1999: 32) Of particular ingenuity was “Old Ape’s Hundred Man-ners”, a series of cartoons portraying Yuan as a foolish monkey — the joke being that Chinese characters for Yuan and monkey are similar. While one cannot verify whether copies of this book made its way to Singapore, there are visual clues to determine that it did influence the cartoonists here.

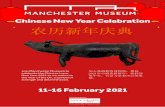

On 20 May 1914, Kuo Min Yit Poh (1914–1919), the organ of the Singapore Kuomintang, started publication.17 Four months later, in its 1 October edition, the paper printed its first cartoon attacking Yuan Shih Kai. The next cartoons appeared in the papers between January and April 1915, with the bulk of them running in the January editions. (Li 1998: 49) The works continued to make fun of Yuan, taking potshots at his policies and plans to bring back the monarchial system in China. One particular cartoon from 1 April 1915 caricatured Yuan as a traitor monkey, opening up the doors of Beijing to allow the entry of birds,

17 Formed in 1912, Kuomintang was the successor to Sun’s Tong Meng Hui. (Hsu 1990: 477)

Visual Self-Representations of the Chinese and the Birth of Chinese Cartoons 189

which symbolized Japanese imperialists. (Figure 7) This cartoon refers to Yuan’s acceptance of Japan’s humiliating 21 Demands on China in exchange for Japan’s tacit agreement to Yuan’s monarchial plans for China. (Hsu 1990: 479) This event angered overseas Chinese with Chinese merchants in Singapore boycotting Japanese goods. (Turnbull 1989: 129) It is very possible that the cartoonist had seen the Pictorial History of Yuan Shih Kai’s Government and was influenced by satirical portrayal of Yuan from that book.

The cartoons in Kuo Min Yit Poh stopped appearing around mid-1915. It was risky to run such cartoons as it was known to Kuomintang members overseas that the publishers of Pictorial History of Yuan Shih Kai’s Government suffered reprisal. Yuan’s cronies took action against the agitators with some of them being imprisoned and exiled.18 Perhaps for that reason, the cartoons in Kuo Min Yit Poh were signed under pen-names. Furthermore, the press conditions in Singapore were tightening up due to the British involvement in World War One. While the primary objectives of the Libel Ordinance (1915) and the Seditious Publications (Prohibition) Ordinance (1915) were to protect the security of the British Empire in times of war, the Chinese newspapers were well aware that such laws could be used against them even if they were only concerning themselves with the affairs of China. In 1912, the editor of Nam Kew Poo (a pro-Sun Yat Sen radical pa-per) was banished from Singapore by the colonial government. Lu Wei-hang had committed the crime of attacking the legitimate government of Yuan in China. (Yong 1991: 31)

Fig. 7 ‘Yuan Betraying China to the Japanese’. Kuo Min Yit Poh, 1/4/1915

18 Only the cartoonist, Qian Bing He escaped the clutches of Yuan with the help of friends. His

cartooning career resumed after Yuan died and he continued to draw anti-warlord cartoons. (Wu 1989: 29)

190 Lim Cheng Tju

Kuo Min Yit Poh stopped publication on 31 August 1915, but was revived on 1 March 1916. (Ke 1995: 221) Cartoons returned briefly to its pages in the months of September and October of 1918 under the penmanship of Zhu Min Xin, an overseas Chinese artist and poet who contributed regularly to Kuo Min Yit Poh. (Li 1998: 49–50)

By May 1916, Yuan had lost power in his bid for monarchial supremacy. With his death on 6 June, China entered into its dark period of warlordism, a decade of lawlessness and disorder that would last till 1927, until Chiang Kai Shek completed his Northern Expedition. (Hsu 1990: 482 and 523) The dictum that bad times give rise to good cartoons is true for this period. 1917 and 1918 saw an influx of cartoons from Shanghai attacking the warlords, imperialistic aggressors and attempts to restore the last Manchu Emperor, Puyi. (Ibid.: 483) Active car-toonists include Iron Chicken and Ma Xingchi. The key cartooning event in 1918 was the publication of Shanghai Puck in September, the first specialized cartoon magazine in China. (Farquhar 1995: 142) It was a happy coincidence that Zhu revived the cartoon column in Kuo Min Yit Poh in the same month. The milieu then was right for the medium to make a comeback in Singapore.

Content and form-wise, Zhu’s cartoons remained very much in the same mode as the Chong Shing Yit Pao cartoons. The aim was to expose the weaknesses and foolishness of the warlords and rally support for the Kuomintang. A combina-tion of words and pictures were utilized to get the message across to the masses, which were required to have some level of street literacy to read the cartoons. Metaphors continued to be a favorite tool to reveal the warlords for what they

Fig. 8 ‘Pleasures of a Rich Drunkard’ by Zhu Min Xin. Kuo Min Yit Poh, 18/9/1918

Visual Self-Representations of the Chinese and the Birth of Chinese Cartoons 191

really were — animals and beasts without a patriotic bone in their bodies. How-ever one particular cartoon of Zhu’s stood out to show that there were Western influences on Chinese cartoonists in Singapore as well. In “Pleasures of A Rich Drunkard”, the figure drawn to caricature a corrupt Chinese government official looked suspiciously like Jiggs of George McManus’ Bringing Up Father. (Figure 8) The famous American comic strip was first published in 1913 and could have made its way to Singapore by 1918.19 This cartoon is revealing in using Jiggs as a symbol of decadence and corruption — showing what the Chinese thought of the West and specifically, America.

This cartoon is interesting in the direct contrast it pose to the racist image of Chinese in the United States by American cartoonists.20 Just as the latter created and perpetuated stereotypes of the Chinaman as the yellow peril and the lowly laundry cleaner, Zhu’s cartoon was using Jiggs as a stereotype of the decadent and foolhardy American. In some ways, this “us versus them” perspective reaffirms the possible empowerment of the Chinese overseas in their own self-image: that they would not be like the Americans or corrupt Chinese government officials in cahoots with the West in exploiting the motherland.

It is not clear why cartoons by Zhu stopped appearing in Kuo Min Yit Poh after 12 October 1918 as Zhu continued to contribute poems to the paper on 20 December 1918 and 21 February 1919. (Li 1998: 52 and 50) Kuo Min Yit Poh ended its run on 6 August 1919, after it ran into trouble with the British authorities for advocating the boycott of Japanese goods in Singapore during the period of the May 4th Movement in China.21

Kuo Min Yit Poh was relaunched as Sin Kuo Min Press (1919–1939) on 1 October 1919, continuing as the organ of the Singapore Kuomintang. (Ke 1995: 229) In the history of Singapore and Malaya Chinese Literature, Sin Kuo Min Press was important as it was the first major newspaper to use baihua or vernacular Chinese writing in these territories. (Fang 1986: 12) It promoted the ideals of the Chinese literary revolution of 1917 to create new works in the service of debunking old traditions and bringing forth new concepts from the

19 According to Maurice Horn, Bringing Up Father was the first American comic strip to achieve world-wide fame, being translated into different languages. But no details were given on its impact in Asia or the timing of success. (Horn 1976: 132) John Lent talked about Bringing Up Father’s popularity and influence on a spin-off strip in Japan in the 1920s, but it is difficult to ascertain the strip’s arrival in Nanyang. (Lent 1995: 59)20

See Kuo (1999), which explores the visualization of stereotypes like “Ah Sin”, the Chinese trick-ster.21

The paper was suspended from publication for one month for its involvement. (Ke 1995: 221)

192 Lim Cheng Tju

West. Sin Kuo Min Zazhi, the paper’s literary supplement, published writings and stories advocating the reform of Chinese language and literature. (Wong 2000: 203) However, this was not a simple task. Adapting to the form of baihua was easy but to come up with new content to reflect the social and literary changes in China and to shape the mindset of readers in Singapore was not achieved till 1925, when the new literary supplements of Sin Kuo Min Press and Lat Pau were launched. (Fang 1986: 4)

Thus even though cartoons in China played a part in dismantling feudalism in the post-May 4th period, it is understandable that in Singapore cartoons were not the focus of newspaper editors and journalists in the early 1920s as they were concentrating on the written word to express the new ideas. Cartoons did appear in some issues of Sin Kuo Min Press’ literary supplements like Uninhabited Island, but irregularly. They took a backseat to the written word.

Conclusion

The history of Chinese cartoons in Singapore in its first 12 years (1907–1918) is much tied to the activities and concerns of the Tong Meng Hui and its successor, the Kuomintang. More importantly, the cartoons reflected an empowering self-image of the Chinese overseas in contrast to the silly and racist representations of the Chinese in the West done by American cartoonists. When they were able to represent themselves visually, whether in America (as evidenced in the cartoons found in To Save China, to Save Ourselves: The Chinese Hand Laundry Alliance of New York) or Singapore, these images were of a political nature and patriotic toward the homeland. This provides a clue to the perception and charge of chau-vinism others have the Chinese overseas in the early 20th Century. In some ways, the self-representations of the Chinese further contributed and perpetuated certain stereotypes the “others” had of Orientals — political, subversive and not particu-larly loyal to the land they were staying. Such sentiments extended themselves to the Second World War (when Chinese cartoons became one of the most powerful propaganda tool in the anti-Japanese campaign) and beyond, creating problems of racial integration in the post-colonial period.

Visual Self-Representations of the Chinese and the Birth of Chinese Cartoons 193

References

Bergere, Marie-Claire (trans. Lloyd, Janet). 1998. Sun Yat-Sen. California: Stanford Uni-versity Press.

Bi, Ke Guan. 1998. Past Wisdom: Cartoon Criticism 1909–1938. Shandong: Shandong Pictorial Publishing.

Chen, Ai Yen. 1991. “The Mass Media, 1819–1980.” In A History of Singapore, eds., Ernest Chew and Edwin Lee, pp. 288–311. Singapore: Oxford University Press.

Chen, Mong Hock. 1967. The Early Chinese Newspapers of Singapore, (1881–1912). Sin-gapore: University of Malaya Press.

Choy, Philip P., Dong, Lorraine, Horn, Marlon K., ed. 1995. The Coming Man: 19th Century Perceptions of the Chinese. Washington: University of Washington Press.

Clarke, Toby. 1997. Art and Propaganda in the 20th Century: The Political Image in the Age of Mass Culture. London: The Everyman Art Library.

C.M. Turnbull, C.M. 1989. A History of Singapore 1819–1988 (Second Edition). Singapore: Oxford University Press.

Cui, Gui Qiang (Choi, Kwai Keong). 1993. Singapore Chinese Newspapers and Journalists. Singapore: Haitian Cultural Company, 1993.

Fang, Xiu. 1986. History of Singapore and Malaysia Chinese Literature. Hong Kong: Joint Publishing Co. and The House of Literature.

Faquhar, Mary Ann. 1995. “Sanmao: Classic Cartoons and Chinese Popular Culture.” In Asian Popular Culture, ed., John Lent, pp. 139–158. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press.

Foo, Kwee Horng. 2004. Woodcuts and Cartoons of Pre-war Singapore (1900–1942), MA. thesis, National Institute of Education, Singapore.

Gao, Yin. 1998. “Different Meanings.” Lao Man Hua 1: 33.Horn, Maurice Horn, ed. 1976. The World Encyclopedia of Comics. New York: Chelsea

House Publishers, 1976.Hsu, Immanuel. 1990. The Rise of Modern China (Fourth Edition). New York: Oxford

University Press.Huang, Jianli. 2006. “Writings on Tongmenghui, Sun Yat-sen and the 1911 Revolution:

Surveying the Field and Locating Southeast Asia.” Paper presented at the International Seminar on “Tongmenghui, Sun Yat Sen and the Chinese in Southeast Asia: A Revisit”, co-organized by the Chinese Heritage Centre and Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall, in Singapore, 12 June 2006.

Hung, Chang-Tai. 1994. War and Popular Culture: Resistance in Modern China, 1937–1945. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994.

Ke, Mulin, ed. 1995. Xinma Lishi Renwu Liezhuan (Who’s Who In The Chinese Community of Singapore). Singapore: EPB Publishers Pte Ltd.

194 Lim Cheng Tju

Kuo, Wei Tchen John, 1999. New York Before Chinatown: Orientalism and the Shaping of American Culture 1776–1882. Baltimore Maryland: The John Hopkins University Press.

Lee, Lai To, ed. 1987. The 1911 Revolution: The Chinese in British and Dutch Southeast Asia. Singapore: Heinemann Asia.

Lent, John Lent. 1994. “Comic Art.” In Handbook of Chinese Popular Culture, eds., Wu Dingbo and Patrick D. Murphy, pp. 279–305. Westport, CT: Greenwood.

Lent, John. 1995. “Easy-Going Daddy, Kaptayn Barbell, and Unmad: American Influences Upon Asian Comics.” INKS Nov. issue: 58–67, 71–72.

Li, Qing Nian. 1996. “Origins of Chinese Cartoons in Singapore and Malaya — Chong Shing Yit Pao.” Yi Shu Tian Di (Artopolis) 8: 19–27.

Li, Qing Nian. 1998 “The Anti-Warlord Cartoons in Kok Min Jit Poh.” Yi Shu Tian Di (Artopolis) 12: 49–59.

Liu-Lengyel, Hongying. 2001. “Man Hua: Cartoons and Comics in China Before 1949.” The Comics Journal 233: 43–45.

Singapore Press Holdings Limited. 1993. Our 70 Years (1923–1993): History of Leading Chinese Newspapers in Singapore. Singapore: Chinese Newspapers Division, Singapore Press Holdings Limited.

The Straits Times, various issues.Wang, Yuan Lin. 1999. 100 Years of Manhua, 1898–1999 Vol. .1 Beijing: Contemporary

Publishing.Wong, Wendy Siuyi and Yeung, Wai Pong. 1999. An Illustrated History of Hong Kong

Comics. Hong Kong: Luck-Win Book Store. Wong, Yoon Wah. 2000. “Singapore (Traditional Chinese Literature).” In Traditional Lit-

erature of ASEAN, ed., Haji Abdul Hakim and Hj Mohd Yassin, pp. 200–207. Brunei Darussalam: ASEAN Committee on Culture and Information.

Wu, Zude. 1989. “A Collection of Cartoons from the Earlier Period of Our Country.” Art History 4: 25–29.

Yen, Ching Hwang. 1976. The Overseas Chinese and the 1911 Revolution: With Special Reference to Singapore and Malaya. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press.

Yen, Ching Hwang. 1978. The Role of the Overseas Chinese in the 1911 Revolution. Sin-gapore: Chopman Enterprises.

Yeo, Man Thong. “Talking About the Cartoons in Chong Shing Yit Pao”, Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Association 10th Anniversary Souvenir Publication, 1985–1995 (1995): 79–85.

Yong, C.F. 1991. “The British Colonial Rule and the Chinese Press in Singapore, 1900–

1941.” Asian Culture 15: 30–37.Yu, Renqiu. 1992. To Save China, to Save Ourselves: The Chinese Hand Laundry Alliance

of New York. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.