The Visual in Archaeology: Photographic Representation of Archaeological Practices in British India

Transcript of The Visual in Archaeology: Photographic Representation of Archaeological Practices in British India

The visual in archaeology: photographic representation of archaeological practice

in British India

SUDESHNA Gum*

Photographs produced during archaeological fieldwork can be employed in shaping the nature of archaeological discourse in different parts of the world. Such photographs are material objects that ut times show what written texts fail to soy. The focus of this paper

is on the photographs produced during archaeological surveys and excavations in British India between the Inst quarter of the 19th and middle of the 20th centziries.

Key-words: phntngraphy, representation, archaeological practicc, India

Introduction Photography was received with great enthusi- asm by archaeologists from the first introduc- tion of the technology in 1839. Within a year, daguerreotypes of ancient Egyptian monuments were in circulation, and by the 1880s detailed photographic records of archaeological field activities were being created. One early exam- ple is the meliculous photo-documentation of the excavations conducted between 1882 and 1886 of the Indian mounds in the Ohio River Valley of the United States. The excavations, directed by Frederick Ward Putnam with the help of his principal fieldworker Charles Metz, were aimed at establishing a scientific method for North American archaeology. Putnam’s use of thc camera to produce visual evidence of his methods is well documented in his letter to Metz in 1884 (quoted by Banta & Hinsley (1986: 76)):

By the way I wish you would continue to keep a section of the big [Turner] mound perfect, so that I can photograph it when I get there in May. I wish you could let a mass stand that v7ould give me a full view from the top mound to the trench off the sec- tor with the pits. Let a column stand where the trees are just back of the old altar . . . so that the photo would show all the layers. Can’t this be done?

Techniques oT photographing anc:ient sites and artcfacts were widely experimcntcd with throughout the latter half of the 19th century, and methods for archacological photography

were soon established. As early as 1904, an entire chapter on the correct manner of taking photo- graphs for archaeological purposes was writ- ten by Sir Flinders Petrie in his seminal work Methods and aims of rxrchneology. Until the 1970s, in many countries a course on archaeo- logical photography was deemed compulsory. Photographs produced during archaeological practice were accepted as providing objective and reliable information. Their use as visual aids and documentary records highlighted their status as evidence. Archaeology’s reliance on photography was based on the belief that the technology promised foolproof objectivity. However, even a cursory examination of the kinds of imagery produced for nearly one-and- a-half centuries reveal consistent manipulation of the photographic technology to tailor many kinds of ‘realities’ and ‘objective’ recordings.

The history of interaction between photog- raphy and archaeology is complex. The condi- tions within which photographs are taken, the choict: of imngcs for acadcmic publications and non-academic consumption, the manner in which people and places are photographed and captioned, reveal wider political and social conditions that govern archaeological practice in different areas of the world. Gero &Root (1990: 19-3 7 ) illustrated this relationship between archaeology, photography and world politics in their article on the public presentation of archaeological practice in the National Geo- graphic. The authors demonstrated how con-

* Cambridgc University Museum of Archacology & Anthrupology, Downing Street, Cambridge CB2 3DZ, England.

Received 4 October 2000, accepted 1 August 2001, revised 23 Octoher 2001

ANTIQUITY 76 (2002): 93-100

94 SUDESHNA GUHA

temporary political ideologies of the United States determined what is photographed in excavations conducted by North Americans in the poorer countries of Latin America and Asia. They identified the many different ways in which imagery and texts were created and manipulated in the pages of the Nafional Geo- graphic to glorify and legitimize the techno- logical and economic imperialism of the United States over ‘primitive societies’ and ‘ancient civilizations’ of the third world.

Following the lead given by Susan Sontag and John Tagg in the 1970s and ’80s respec- tively, research on the history of photography, on the impact of this technology on 19th-century sciences, and on the nature of visual evidence produced through this medium in disciplines such as social anthropology, art history and sociology has shown that photographs are so- cially and politically constructed like all cul- tural representations. They are not merely taken, but made. A photograph is indexically linked to that which it records, and in most instances ‘the data allows more to be seen or analysed than lisl possible at the time of collection’ (Banks & Morphy 1997: 17). As objects that are inten- tionally created. photographs produced during archaeological fieldwork carry information, at times variant, from contemporary texts on ar- chaeological practice.

The histories of photography, archaeology and colonialism are closely related in the Indian sub- continent. India became a British dominion in 1858. and three years later the Archaeological Survey was formally es tablislied. Photography came to India as early as 1840, and from its first introduction was enthusiastidly used by the officers of the East India Company to docu- ment the country’s architectural landscape. With the developments in archaeological methods and aims initiated by the British officers of the Survey, photography became an active partici- pant in the archaeological discourse. Over the last decmle, research on the history of South Asian archaeology has unravelled many strands of colonial politics that have shaped the de- velopment of archaeological practice in India. However, photography’s role in nurturing and promoting British interests in the archaeology of India, especially during the first half of the 20th century, has been largely overlooked.

If photographs of archaeological practice are accepted as intentionally created artefacts, thcn

they become important material sources for understanding the history of the discipline. 19th- and early 20th-century archaeological field photographs from South Asia are not only prod- ucts of archaeological practice in the subcon- tinent, but their imagery, use and distribution can reveal the ways in which archaeology was used to serve British colonial aims.

Photography and documemtation The technology of photography could, for the first time, permanently fix a shadow on a pal- pable material. During the 19th century, the technical, optical, mechanical and chemical features associated with photography were largely accepted as being independent and free of selective discrimination of the human eye and hand. This assumed objectivity and real- ity of representation in photographic images favoured the camera over other tools of repre- sentation. As the century progressed, the cam- era became a powerful instrument of surveillance. Photography established itself as one of the principal modes for recording facts, of surveying the unknown (including the na- tion’s poor, mentally ill and dispossessed popu- lation) and colonial lands, and for gathering evidence (as used by the police Iorce). Photo- graphs were accorded the status of evidence bp observational sciences and by institutions of power such as colonial: and national gov- ernments.

From the late 18th century, European atti- tudes towards indigenous p o p l e in distant and subjugated lands were largely formed by theo- ries of racial supremacy aild social evolution. These were effectively used by imperial pow- ers to sustain unequal relationships. Photog- raphy brought out the relational imbalance explicitly. The practice of photographing ‘the other’ was itself an unequal action. From the middle of the 19th century, posed bodies of human beings (in many instances semi-naked or naked) in front of a measuring grid or a scale became an established norm for taking ethno- graphic photographs of ‘saviage’ and ‘primitive‘ races. Such photographs were accepted as re- liahlc documents for comparative physiology (Spencer 1992). As visual records of people colo- nised by ‘superior’ powers, such images rein- lorced the colonial hierarchy of the century.

In the Indian subcontinent, the best-known early example of the use of photography for

PHOTOGRAPHIC REPRESENTATION OF AKCHAEOI.OCXAL PRACTICE IN BRITISH INDIA 95

ethnological investigations is John Forbes Watson & John William Kaye’s edited eight- volume set, The people of India. It n7as pub- lished by the Indian Museum in London between 1868 and 1875, and contained over 500 photo- graphs acc:ompanied by text, depicting differ- ent ‘races’ and ‘types’. The preface to the work mentions that the project was initiated by an informal request from the then Governor-Gen- era1 Canning to civilians and army officers of the East India Company for photographic sou- venirs of India. However, the Mutiny of 1857 transformed its nature and the history of its genesis is not as simple as the preface leads thc reader to believe. Contemporary documen- tation reveals that large-scale collection of eth- nographic photographs for the project did not begin until after an official circular was sent out to the provincial administration in July 1861. Over half of the 200 copies of the eight-set vol- umes were retained by the Political and Secret Department of the Governmcnt of India for of- ficial use. The initial collection of photographs for the project may also have been intended for display at the London international cxhibi- tion of 1862. Whatever the underlying motives of the project, the published volumes ‘served to reinforce notions of dominance and control, both in the selection of their subjects and in their descriptive text’ (Falconer 2000: 80; also Pinney 1997: 34-44).

Throughout the late 18th and 19th centu- ries, various schcmcs were undertaken by thc colonial powers to obtain information on ar- eas under their subjugation. The employment of government anthropologists in colonial lands, the establishment of topographical, geological, linguistic: and archaeological survey organiza- tions, and regular publications of population censuses are a few examples. From its incep- tion, photography played a major role in these projects of colonial documentation. Compared to other visual forms, such as sketches, paint- ings and plaster-cast models, the cheap tech- nology of photography available from thc 1860s, and its easy replication, made it an indispen- sable recording device. For example, in 1855, the East India Company decided to replace its draftsmen with photographers, stating in a let- ter from London (Desmond 1974:314):

We have rccently desircd the Goveriinicnt of Bom- hap to discontinue the employrnenl of draughtsrnen

in the delinealion of the antiquities of Wcstcrn In- d ia and to ernploy photography instead, and it is our desire (hat this rrielliorl be generally substituted through out India.

The British historian of Indian architecture, James Fergusson’s (1 868) remark that ‘forty negatives will not cost more than one cast; and though they cannot supply its place, the larger field they cover and the number of incidental details they include render them invaluable adjuncts’ provides another apt example. From the 1870s, photography determined the nature of the visual documents produced by the Ar- chaeological Survey in British India.

Nineteenth-century photography and the Archaeological Survey of India The Archaeological Survey of India, initially established in 1861 as a non-permanent insti- tution, was a colonial bureaucracy of the 19th century. Its crcntion as a government organiza- tion to survey and document the historical sites of India just after the Mutiny, can be related to the initiation of an organized programme by the British Raj to compile information on In- dia. The initial objective of the Survey, that of systematic documentation of Indian monunients of historical importance, and not their preser- vation or upkeep [see Canning 1862), can be linked to the British imperial aims of creating centralized bureaucracies in Indian provinces and states to systematize techniques of collecting data within the subcontinent [see Bayly 1999: 121-3). However, the intellectual efforts of in- dividrial Survey officers fostered the growth of scientific archaeology in the subcontinent and, until the 184(ls, the Archaeologicd Survey of India remained the primary institution that governed the developments within the disci- pline.

For most Survey officers of the 19th century, practising archaeology meant registration of visible architectural and epigraphic monuments, their identification, description and exact re- production for publication (Biihler 1895). Piec- ing together the history of Indian art and architecture and establishing a chronology for the history of the subcontinent through its ma- terial relics were the two main aims of archae- ology. This is well exemplified in the tenures of the (only) two Directors-General during the chequered life of the Survey in the 19th cen-

9G SUDESHNA GUHA

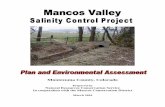

FIGURE 1. P.36676. Temple at Halehid, 13th century AD. Albumen print, c . 1860-1 880. (Courtesy (,’ambridge University Museurn of Archaeo1og.y b Anthropology.)

tury, Alexander Cunningham (1871-1 885) and James Burgess (1886-1889). Therefore most of the 19th-century photographs depicting the activities of the Archaeological Survey are of historical monuments; and amongst the archi- tectural photographs of the century, no distinc- tion can he made between ‘archaeological’ and ‘non-archaeological’ images.

The manner in which the Great Stupa of Sanchi was photographed by Henry Cousens between January and March of 1900 (Burgess 1902) is one example of how photography was used to produce ‘true’ representations of the subject matter. Such acts of photography were based on the belief that photographic archives could preserve the past for future reference, and were advocated strongly for the application of the technology to observational sciences. Ex- tracts from a paper read by Rev. F.F. Stratham at the South London Photographic Society on 1 7 May 1860 illustrate the point:

The photographer will point his camera at each pinnacled niche or florialed doorway; he will take his sun-painted sketch of each figured corbel or gm- tesque gargoyle; and in facl, carry away in his port- folio every nice detail of the architectural detail long before time, with his destructive hand, shall have had the opportunity to mar any more of the beauty of the original; and when Iuture ages shall he wish- ing to picture to themselves the appearance of this or that abbey or cathedral long since crumbled to decay. . . they will thank pruvidence for the perfec- tion of photography in the middle of the nineteenth century.

The Survey and the ‘natives’ Despite the realist paradigm that governed the use of the camera as a recording tool, photo- graphs followed the aesthetics of the period. For example, the genre of the picturesque, the dominant visual aesthetic in romantic landscape paintings of the 18th century, was developed further through the means of photography. Al-

PHOTOGRAPHIC REPKESENTATTON OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL PRACTICE IN BRITISH INDIA 97

though accurate documentation by means of photography was adopted in programmes of salvaging cultures considered threatened into extinction and/or irreversible changes, the images produced were not necessarily ‘true’ documents. Many photographs that were pro- duccd to capture the rapidly changing world evoked feelings of nostalgia at the passing away of traditional customs. Sentimental and romantic photographs of ‘primitive races’ and ‘ancient civilizations’ flooded the 19th-century markets. The dictates of contemporary aesthetic conven- tions, together with the need to ratify prevail- ing scientific ideas about ‘other’ cultures, produced powerful stereotypes within photo- graphic imagery (see Edwards 1992a: 10). In the Indian context, concerns about salvaging native architectural heritage can be found echoed in the documentation schemes of the Ar- chaeological Survey (e.g. Cole 1867). The dual role of salvaging India’s ancient traditions arid providing a visual alibi for objective documen- tation aided the production of a large number of romanticized photographs of architecture and landscapes that merit the status of art. In many o l them, local Indians were strategically placed so that their physical bodies would provide a visual reference for the height, length and/or width of the building photographed (FIGURE 1). The natives against their ruins, photographed during the systematic restoration of their an- cient heritage by the Imperial Survey, became a powerful colonial imagery of a civilization in decay (from former grandeur) being restored by the British (see Cohn 1996: 93).

It has been suggested that the ‘photographers working for the Archaeological Survey. . . pro- duced some of the best photographic work in India during the nineteenth century’ (Falconer 1990: 271). Yet, on closer examination, it be- comes clear that, unlike the native photogra- phers of the Survey, the British officers were almost always acknowledged with the author- ship of their works. The names of the Survey’s Indian photographers (28 names found as early as the 1870s), employed at the same rate of pay as other draftsmen, appear to be absent from all known official publications. Appendix (Hiii) in Cole’s reports for the year 1881-82 is one example. In the column detailing whether the building/monument has bcen photographed or not, Cole mentioned the names of individual British officers and commercial studios (both

Indian and British) who had previously pho- tographed a building, but consistently omitted mentioning the staff photographers of the Ar- chaeo1ogic:al Survey who had accompanied the survey teams. If a building/monument had been photographed by them, it was merely listed as ‘has been photographed’ (Cole 1882: 39-72). The British officers of the Survey are usually credited with the authorship of their images in all published lists providing details of pho- tographs and negatives produced by the Ar- chaeological Survey during the latter part of the 19th century. The elimination of all junior staff photographers, which included almost every Indian photographer of the Survey, from official lists betray bureaucratic, if not racial, prejudice.

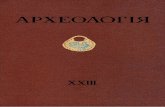

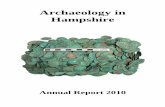

The visual construction of a scientific practice From the beginning of the 20th century, sys- tematic site excavations altered the nature of the discipline. The methodological develop- ments involved in the intcrpretation of exca- vated sites helped to promote the claim that archaeology was ‘scientific’. It also produced a unique imagery of excavations that could be directly associated with the discipline. The two most influential British Directors-General of the Survey in the early zoth cxntury were Sir ]ohn Marshall (1902-28) and Sir Mortimer Wheeler (194448). The former brought to the Indian subcontinent the methods of scientific exca- vation, the latter codified the practice. A gradual development of excavation imagery is evident throughout this period. The two photographs, one from Ghaz Dheri, taken in 190:! and prob- ably one of the earliest visual representation of an excavation (FIGIJRC 2), and the other from Arikamedu (FIGURE 3) , taken 43 years later in 1945, represent the two ends of the develop- ment spectrum.

Although the role of archaeological photog- raphy as an instrument for recording remained common throughout the 19th and 20th ccntu- ries, the scope of documentation changed with the onset of large-scale excavations. The em- phasis shifted towards the systematic depic- tion of activities performed in the field. The objective was to transform photographs of sites into quantifiable documents and this was achieved by producing iniages that could be compared. From the 191os, the appearance of

SUDESHNA GUHA

FIGURE 2 . Excavation at Ghaz Dheri, 1902. Silver-gelatin print Publibhed in the Annual Report of t h P Archaeological Survey of India 1902-03. (Courtesv Archaeological Srrrvey oflncfii, New Drlhi )

the measuring scale tiecame an ubiquitous fea- ture in all photographs of excavations. Although the scale was depicted in Survey photographs of the 19th century, an example being John Burke’s photographs of the ancient temples in Kashmir, in many images its relationship to the artefact depicted remained unclear. The ‘cor- rect’ positioning of the scale in relation to the object in the photograph was codified in the imagery from the first half of the 20th century. The measuring apparatus was usually laid flat before the object to indicate width, or kept stand- ing on the sides to indicate height. The pres- ence of these wooden scales in the early 20th-century archaeological photographs, like the grids and scales in the 19th-century ethno- graphic photographs, aided the transformation of an archaeological image into a comparative visual document.

During Mortirner Wheeler’s tenure, sites of excavations were converted into laboratories for archaeological practice. Wheeler imposed strict rules for archaeological photography, cam- paigning for the ‘proper’ method of taking pho-

tographs on site (Wheeler 1956). He used the camera as a tool for generating evidence for the performance of ‘rational’ and ‘scientific’ field- work, and for keeping meticulous records. Con- sequently, many ncw images were created during his tenure. Photographs of pottery yards (e.g. Brahmagiri 1947), payment of wages to labourers (c.g. Chandravali 1947), sets of consecutive photographs representing the removal of buri- als on site (e.g. Harappa 1948), group photo- graphs depicting team members and close-ups demonstrating the labour involved in clearing sites for excavations (e.g. Arikamedu 1945), are some examples. The conscious policy of mak- ing the performance of fieldwork visible is Wheeler’s legacy to archaeological practice in the Indian subcontinent.

Stamping information on a print regarding its corresponding negative number, the date when photographed and the officiating branch responsible for its production, composing cap- tions and pasting each print on albums allo- cated to separate excavation seasons of a particular site, inscribing relevant photographic

PHOTOGRAPHIC KEPRICXNTATION OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL PRACTICE IN BRITISH INDTA 99

FIGURE 3. Excaviltioris nl Ariknmedu, 1945. Silver-gelatin print. Captioned as ‘Discipline’ in Wheclcr (1956). (Courtcsy Archaeological Survey of India, Ncw Dcl1ii.l

details on negatives, and maintaining annual negative registers from each excavated site, are activities which were begun by the photogra- phy department of the Survey from the begin- ning ofthe 20th century, and staunchly practised from Wheeler’s tenure. Together with withhold- ing the names of the photographers and those in the photographs. and the abandonment of all aesthetic genres of representations, the aim throughout the 20th century has been to pro- duce ‘objective’ visual records. However, in Indian archaeology, the actual photographer of an excavation has usually been the supervisor or the director who has dictated what aspects of the finds were worth recording. This domi- nation of the excavator’s eye vis-6-vis the pho- tographer’s in site imagery inevitably broke the unquestioned neutrality of a visual record, mocking the often repeated mantra that ‘the photographer is expected to tell the truth with the help of his camera’ (Srivastava 1982: 72- :3). Throughout the century, the element ofcon- scious choice has determined the manner of photographing archaeological sites, the subjects

photographed and what has been visually pre- sented as archaeological data.

Representation and reality The architectural photographs taken by the Archaeological Survey during the 19th and the early 20th century were mainly used as docu- nieiitary records, for academic references, for international exhibitions and for commercial purposes. Beautiful folios of photographs de- picting ancient temples, medieval palaces, tombs and mosques, were published for sale by the Survey during the 1860s, and to a large extent photography formalized the relationships be- tween tourism and archaeology in the subcon- tinent. Photographs of ancient and medieval monuments were often transformed into post- cards and souvenirs. Official photographs de- picting historical sites and native types were periodically exhibited in European international exhibitions. An example is the Exposit ion Universelle at Paris in 1867. where a selection of such images was shown in the section enti- tled Hisfoire du fravuil. The value and utilitv

100 SIJDESHNA GUHA

of cheap native labour for British archaeologi- cal fieldwork in India is evident from many of these photographs, whether ethnographic, ar- chilectural or depicting excavations. The name- less local natives are shown either as measuring scales or field workers, whose ‘apartness’ from the Survey officers (mostlv British) fitted in with the general iconography of colonial India.

Many excavation photographs of ‘important’ sites such as Harappa and Mohenjodaro, dis- covered in the early 20th century, have been widely published in Indian and British news- papers, although most photographs of site ex- cavations were consumed for academic purpose. As Indian archaeology endeavoured to become a rational science, the names of all photogra- phers were withheld from official publications, be they British or native. The paucity of writ- ten information about the official photographers of the Survey, of the ficld labourers in the pho- tographs, and the use of short technical cap- tions for images depicting people, were deliberate attempts at producing an impersonal imagery. Yet the colonial roots of Indian archae- ology are remarkably visible. In a land whose written history could not be trusted by its

References BANKS, M. & H. MOKPHY. 1997. Introduction: rethinking visual

anllrropology. in !vT. Banks & H. Murphy (cd.), k t h i n k - ing visual anthropology: 1-35. New Havcri (U): Yale University Press.

h4NT24, M. & C.M. HINSLBY. 1986. Archaeology: intermingling of human past and present through the camera’s eye, in M. Ranta & C . M . Hinsley (ed.], From site to sight: anfhro- pohgy , photogrciphy and the power of imagery: 72-99. Cambridge [MA): Peabodp Museum Press.

BAYLY, S.B. 1999. Coste, society nnd politics in Indiofrom the eighteenth centiii;v to the niodern iige. Camhridge: C a n - bridge LJnivcrsity Press.

UUHLER, C;. 1895. Some Notes on Past and Future Archaeologi- cal Explorations in India. Journol of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain a n d Ireland for 18Y5: 649-tiO.

BURGESS. J. 1902. The Great Stupa at Sanchi-Kanakheda. Jour- riuJ of the Ruyoi Asiotic Society of Greot Britain a n d Ire-

CANNING (Lord). 1862. Minute by tlic Right Hon’blc the Govcr- nor General of India in Council on the Antiquities of Upper India-dated 22nd January 1862, in Cunningham (1871) Preface to Four Reports m a d e during the years 186’2-63- fid-fi5: I. Simla: Govt. Central Press.

COHN. B.S. 1Y96. Coloniaiism and itsfurms ofknowiedge: the British in h d i a . Princeton (NJ): Princeton TJniversity Press.

COLE, H.H. 1067. bxtriicl from a Memoraridunr ofrering sug- gestions for cullccliiig iIifornration about the aricirnl ar- chitecture of India, by Lieutenant 11.K Colc, R.E.. dalcd Naini Tal, June 1867, in Cole (1882): Appendix A.

1882. First Report o f the Curator of Ancient Monuments in r d i o for the Ymr Z88?-#2. Sinila: Govt. Central Press.

DESMOND. R. 1974. Piiotography in India dilring the ninet?enth century. London: India Office Library arid Records Re- port.

llllld for 1902: 29-49.

colonizers, scientific excavations were promoted as a means of providing a reliable past. The photographs of uneducated masses of toiling ‘natives’ physically uneaathing their past ac- cording to British decree, however, speaks of a different reality.

Being an off-spring of colonial bureaucracy, the performance of archaeology in the subcon- tinent has always been ‘controlled’ by a select practising elite, a feature visible in the photo- graphs, although seldom revealed in writing. The bureaucratic hierarchy of the colonial Sur- vey has left its legacy within the post-colonial excavation field. The manner in which infor- mation about sites is gengrated, recorded and published still follows the dictates of official rank and status; and the official photographs of the Archaeological SurJrey, even to this day, hint at the inherent systems of power that gov- ern the organization.

Acknowledgemen t . 1 w o u l d l ike take this oppor tun i ty t o express my grat i tudc to t h e la tc Director-Gcncral 01 t h e Archaeological Survey of India , Mr Ajai Shankar , for his generous a n d whulc-hear ted suppor t in granting inc access to t h e archives of t h e Archaeological Survey of India .

EDWARDS, E. 1992a. Introduction, in lidwards led.): 3-17. (Ed.]. 1992b. Anthropology and photogruphy: 1860-1920.

New Haven (CTIiLondon: Yale University Press in asso- ciation with the RAI.

FALCONER, J. 1990. Photography in nineteenth-centurv India, in C.A. Bayly led.). The Raj: F i l t h and fhe British 7600- 1947: 264-77. London: Natibnal Portrait Gallery Publi- cations.

znoo. A passion for documentation: architecture and eth- nography, i n Vidyo Dehejia (ed.). India throrrgh the I m s : phatogruphy I840-1B21: 69-118. Wdshingturi (DC): Freer Gallery of AdAr thur hl. Sackler Gallery.

FERCUSSON, J. 1868. Memorandum by James Fergusson, esq. [lSSS), regarding objects in India of which it is desirable casts should he obtained, in Cole (1882): Appendix B.

GERO, J. & D. R o t n . 1 990. Public prwenlations and private cmi- cerns: archaeology in l hc pagel: of Llw Natioiial GengiaplriL, in P. Gathcrcolc & U. Loweritha1 (cd.), The polilics of tho past: 19-37. London: Unwin Hpman.

PINLTY, C . 1997. Camera Indica: the social life of Indian pho- tographs. London: Reaktion Books.

Son I A G , S. 1971. 0 1 7 photography. Harmondsworth: Penguin. SPt:NCKR. F. 1992. Some notes on the attempt to apply photog-

raphy In anthroponietrv duling the second half of the ninekcnlh century. in Edwards (ed.): 99-107.

SRIVASTAVA, K.M. 1982. New e m uJIridinn Archneology. New Uelhi: Cosrrio fublicstions.

STR.MHAM, F.F. 1860. On the applicatioii of photography to scientific pursuits, British Journal o/Phofogruphy 121(7): 191-2.

TA(;~:. J. 1988. The burden of representation: essays on photo- graphs n n d histories. Basingstoke: Macmillan Education.

WHEELER, R.E.M. 195G. Archaeu1og.y from t h e earth. Harmoudsworth: Penguin.