The visual and verbal rhetoric of Race Records and Old Time ...

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of The visual and verbal rhetoric of Race Records and Old Time ...

Selling the Sounds of the South:

The visual and verbal rhetoric of Race Records and Old

Time Records marketing, 1920-1929

Luke Horton

Submitted in total fulfilment of the

requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy

Dec, 2011

School of Historical and Philosophical Studies

University of Melbourne

Abstract

In the early 1920s, the phonograph industry in America began producing two very

distinct record catalogues of racially segregated Southern vernacular music, one called

Race Records and the other called Old Time (or 'Old Time Tunes', 'Songs of the Hills and

Plains', 'Familiar Tunes Old and New' and towards the end of the decade simply 'hillbilly'

records). In the marketing for these new catalogues, two completely separate streams of

Southern music were presented, one purely white and one purely black, a separation that

denied any possibility or history of the intermingling of the races, a bifurcation of a

shared tradition which became a revision of Southern history, and a segregation in

keeping with the race policy of the Jim Crow era.

‘Selling the Sounds of the South’ argues that the verbal and visual rhetoric of the

marketing for these new catalogues of music (contained not only in catalogues

themselves, but in advertisements, window displays, and other promotional material),

presented a unique utilisation of Southern images that offered a new definition of

Southern black and white music. While heavily reliant on existing constructions of white

and black musical culture, the creation of these catalogues involved the recasting of

major cultural tropes and resulted in an intertextual construct that itself was something

new. The record industry's Old Time artist remained at the mercy of Southern stereotypes,

but these musicians were neither simply the pious folk relics projected by folklorists nor

the comic caricatures of the radio hillbillies, but rather more complex characters,

personified by the dignified mountain entertainer who sometimes sang contemporary

songs as well as traditional material and who was a product of both the modernist and

anti-modernist impulse. Likewise, the verbal and visual rhetoric of Race Records drew

heavily on existing models for selling black music, such as minstrelsy and songbooks of

folklorists, and yet the mostly sophisticated, professional, urban, vaudeville performers

who became the first Race Records artists, and the music they made, also had a

significant impact on the marketing images of Race Records. While these rhetorics were

decidedly Northern white conceptions, the fact that both catalogues were created in

response to consumer enthusiasm for a vernacular musical culture had a huge impact on

their marketing, and it is the matrix of cultural and commercial forces that makes these

constructs such interesting examples of the commodification of culture in the burgeoning

consumer culture of the 1920s. Put another way, the record industry's marketing imagery

for these musics ultimately combined well-worn stereotypes with modern images that

were inspired by, and to some degree produced by, this music and its practitioners, and

this created a new version of Southern black and Southern white musical culture in 1920s

consumer culture.

This is to certify that:

(I) the thesis comprises only my original work towards the PhD except where

indicated in the Preface,

(ii) due acknowledgement has been made in the text to all other material used,

(iii) the thesis is fewer than 100,000 words in length, exclusive of tables,

maps, bibliographies and appendices or the thesis is [number of words] as

approved by the RHD Committee.

Acknowledgements

It has been my greatest pleasure and privilege over the past four years to work closely

with my supervisors in the School of Historical and Philosophical Studies at the

University of Melbourne, David Goodman and Barbara Keys. Besides reading countless

versions of these chapters, and assisting me with every stage of the PhD writing process,

their enthusiasm, encouragement, and academic rigour, has sustained me through this

project and I have learnt a great deal from both of them.

One of the great things about writing a PhD is that, over a period of several years, you get

to share your project with many people, and through papers given at conferences etc., I

have had feedback from countless academics that has helped sharpen my ideas and

clarify my arguments. Among the many great scholars that have commented on my work,

I must make special mention of Susan Smulyan and Patrick Huber, whose enthusiasm for

the project and whose advice I appreciate a great deal. I must also thank the staff at the

libraries and archival collections where I did my research in the USA. The staff at the

Wilson Library at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and at the Recorded

Sound Archives at the Library of Congress, Washington D.C., were incredibly helpful

and patient.

While it is customary in acknowledgements to thank ones parents for their support and

encouragement, I would have to thank my parents, John and Judy Horton, regardless of

familial bonds, as this project would not exist if not for them. It was in my parent’s

bookshelves and record collection that I found my love for both history and music. These

treasure troves have provided me with the initial inspiration for much of my scholarship.

My honours thesis at Latrobe University on Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk

Music was inspired by the copy of the Anthology in my father’s record collection (and his

expert commentary on much of its contents). Again, with this project, it was my parent’s

record collection and their excellent library, which contains a large section of historical

works on early blues and country music, that awakened me to the visual and verbal

rhetoric of the advertising for these records and their import. Therefore, I owe my parents

a huge debt of gratitude for the passion for books and music they have instilled in me, as

well as for their constant encouragement and support.

I am also in the incredibly fortunate position of having several brilliant academics in the

family. Jessica Horton’s passion for good history has been a constant inspiration to me,

and her insights into my own work vastly improved it. Undine Sellbach, with a PhD in

Philosophy, has always offered new perspectives on the material of this study, and our

many conversations over the years about the process of writing a PhD have been

incredibly helpful. Lastly, and most importantly, I must thank Antonia Sellbach, whose

love and support I could not have done this without, and whose experience with

completing a Masters helped both of us keep perspective through all the ups and downs

of writing a PhD.

i

Contents

Illustrations......................................................................................................................ii

Introduction.....................................................................................................................1

Chapter One: Southern Vernacular Music Enters the Mainstream……………….24

Chapter Two: Out From Behind the Minstrel Mask: Race Records Advertisements

in the Black Press in the 1920s……………………………………………………….50

Chapter Three: The Curious Character of the Old Time Artist as Presented

by the Record Industry……………………………………………………………….90

Chapter Four: Cultural Uplift and the Talking Machine World…………………..117

Chapter Five: The Accommodation of a Commercial Reality: Race Records and

Old Time in the Talking Machine World …………………………………………...139

Chapter Six: In the Press: The Reception of Race Records in the Black Press….168

Epilogue: What the Depression Did to the Marketing of Southern Vernacular Music

………………………………………………………………………………………...194

Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………....201

Bibliography.................................................................................................................205

ii

Illustrations

1.1 Victor ‘Race Records’ catalogue 1930……………………………………………..1

1.2 OKeh ‘Old Time Tunes’ catalogue 1927…………………………………………...2

2.1 Victor Talking Machine Company's 'New Victor Records' supplement,

June 1907...................................................................................................................33

2.2 'A Musical Galaxy', Victor supplement, 1927........................................................37

3.1 Minstrel and Coon Song covers…………………………………………………..61

3.2 ‘Argufying’ and ‘Oh Boy’, Chicago Defender, September 21, 1927 and March

21, 1928…………………………………………………………………………….63

3.3 ‘Mr Freddie’s Blues’, Chicago Defender, October 11, 1924……………………..65

3.4 ‘Jazzbo Brown’ and ‘Mean Papa turn in your Key’, Chicago Defender, July

10, 1926, and June 21, 1924……………………………………………………...66

3.5 Columbia Ethel Waters ad, Chicago Defender, July 4, 1925…………………...69

3.6 ‘Sorrowful Blues’, Chicago Defender, May 24, 1924…………………………...71

3.7 ‘Organ Grinder Blues’ and ‘Aint Nothin’ Cookin’ what you’re Smelling’,

Chicago Defender, November 17, 1928, and October 23, 1926………………..72

3.8 ‘Roamin’ Blues’, Baltimore Afro-American, January 4, 1924………………….76

3.9 ‘Brownskin Mama Blues’, Chicago Defender, April 21, 1928………………….80

3.10 ‘Hard Road Blues’, Chicago Defender, February 4, 1928……………………..80

3.11 ‘Ash Tray Blues’, Chicago Defender, September 1, 1928……………………...82

3.12 ‘He’s in the Jailhouse Now’, Chicago Defender, December 31, 1927………....83

3.13 ‘Jonah in the Belly of the Whale’, Chicago Defender, October 1, 1927………85

3.14 ‘Reverend J.M Gates’, Chicago Defender, Oct 20, 1928………………………86

3.15 ‘The Prodigal Son’, Chicago Defender, September 10, 1927………………….87

iii

4.1 OKeh ‘Old Times Tunes' catalogue, 1926…………………………………...107

4.2 OKeh ad for Fiddlin' John Carson and Henry Whitter, Talking Machine

World, June 15, 1924…………………………………………………………...109

4.3 Columbia 'Familiar Tunes Old and New' catalogue………………………....112

4.4 ‘The inside story of the Hillbilly Business’, Radio Guide, 1936……………..115

5.1 Victor, Victorla ad, Talking Machine World, June 1924……………………...145

Introduction

In the early 1920s, the phonograph industry in America began producing two very distinct record

catalogues of racially-segregated Southern vernacular music, one called Race Records and the other

called Old Time (or 'Old Time Tunes', 'Songs of the Hills and Plains', 'Familiar Tunes Old and New'

and towards the end of the decade simply 'hillbilly' records). Victor Talking Machine Company, the

industry leader throughout the period, took longer than most to enter these new fields of recording,

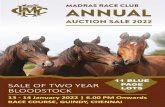

but by 1927 it had relented and began aggressively pursuing the markets for both. Figure 1.1 shows

the cover of one of Victor's last Race Records catalogues from 1930, before the stock market crash

severely curtailed record production:

Figure 1.1 (Source: Southern Folklife Collection, Manuscripts Department, University of North

Carolina, Chapel Hill)

Introduction 2

Figure 1.2 is the cover of an Old Time Tunes catalogue produced by OKeh Records, one of the

pioneers in the field, probably from 1927:

Figure 1.2 (Source: Jim Walsh Collection, Recorded Sound Archives, Library of Congress)

The images used here to represent these catalogues of music are strikingly dissimilar. In the first we

are presented with a black man sitting on a dock, a ferry in the background, plucking at his guitar

and, one imagines, singing a plaintive melody. In the second we are presented with a white man, in

a suit and tie, sitting on a stump of a tree in an idealised mountain setting, a log cabin in the distance

behind him. These images convey different moods; the Race Records catalogue cover is sombre, the

artist possibly a down-on-his-luck itinerant worker, an image in keeping with the blues contained

inside, while the fiddler in his suit and tie on the Old Time Tunes catalogue cover (modelled closely

on OKeh’s promotional photograph of Fiddlin’ John Carson) suggests a humble respectability and a

more harmonious, pastoral idyll. But there are similarities between them. Both covers present a

solitary artist without an audience. There is no element of formal performance to either of these

images; this is music played to entertain or sustain the player himself, therefore both suggest the

Introduction 3

authenticity of the 'folk' musician.1 Another similarity is that both of these images evoke the South;

the first a river port such as New Orleans or Memphis on the Mississippi River, and the second a

Southern 'hill country' or mountain region (the artist probably had the Appalachian Mountains in

mind). Of course, if the reader does not recognise instantly that this is supposed to be the South, this

implication is reinforced as soon as one opens the catalogue and finds blues ‘expressing the true

heart of the South’, the ‘rollicking, jazzing boys from the Sunny South’ or the 'genuine songs of the

Southern mountaineers’.2

This study examines the visual and verbal rhetoric of both Race Records and Old Time marketing.

The two catalogue covers presented above suggest some of the key questions and underscores the

central contention of this research. What we see in the covers of these catalogues are two separate

streams of Southern vernacular music, separated rhetorically by region: the Deep South as the South

of blacks and the mountain South as the white South. But how did these images come to define the

various musical genres featured in these catalogues in the 1920s? What were the true determinants

of this imagery? What ultimately did it present and what did this say about blacks and whites, and

in particular Southern blacks and whites, in the 1920s? These are the questions of this study.

In pursuing such questions, this research has led me to a central contention: that what is presented in

the visual and verbal rhetoric of Race Records and Old Time was something new in the consumer

culture of the 1920s. As can be seen in the catalogue covers above, these images present familiar

images to present day viewers, the down-on-his-luck blues musician and the white Southern fiddle-

playing mountaineer. To a certain extent these figures were not unfamiliar in the 1920s, the blues

musician and the Southern fiddler were well-known popular entertainers to some, and to others the

image would have been familiar through songbooks and popular fiction that contained such

characters. Yet neither of these figures are simple stereotypes. The most popular image of the black

performer in the 1920s was still the minstrel performer. Al Jolson 'The Singing Fool' was the

biggest black star of the decade. Besides the pious image of the Jubilee singers who sang black

spirituals, minstrelsy was still by far the commonly used imagery used to sell black musicians. As a

result, most scholarship on the imagery of Race Records advertisements and marketing has likewise

focused on the imagery of minstrelsy and what some have described as the demeaning and

inappropriate representation of blues musicians in the 1920s by the record industry. While this study

1 Here they different stringed instruments, but many Old Time covers featured guitar players as well, although the opposite, a black man playing a fiddle, would never be used on a Race Records catalogue, as the instrument became synonymous with white mountaineer folk music. 2 ‘The Paramount Book of Blues’ (Southern Folklife Collection, Manuscripts Department, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill) and Victor ‘Olde Time Fiddlin’ Tunes’, 1924 (Jim Walsh Collection, Recorded Sound Archives, Library of Congress).

Introduction 4

recognises the lingering influence of minstrelsy, it contends that the visual and verbal rhetoric of

Race Records transcended minstrelsy. The above catalogue cover is one example of how. What we

see here is a black man free of minstrelsy’s performative gestures, simply playing his music.

Likewise, the most enduring image of the 1920s hillbilly is the comic hayseed character in a straw

hat and a plaid shirt. This is not what is presented in Figure 1.2. The fiddler presented to the reader

in 1927 by OKeh is a man in a suit and tie, a proud and dignified character, simply playing his

music in his mountain home. Undoubtedly these are romantic images, but not crude stereotypes.

What we are presented with in Race Records and Old Time marketing are not simple caricatures,

neither minstrel characters or hillbilly hayseeds, but something new. This study seeks to explain

how the record industry, while fumbling for new markets for phonographs and phonograph records,

produced these new figures in the 1920s.

This side-by-side analysis of the marketing of Race Records and Old Time is underpinned by the

understanding that, while we are presented with two parallel, yet apparently completely unrelated

musical traditions in these segregated catalogues, the reality of Southern musical culture of course

was quite the contrary. Music historians such as Charles Joyner, Archie Green, and Tony Russell

have persuasively argued that, prior to its commercial segregation, there existed in the South a

shared musical tradition from which musicians both black and white drew. Tony Russell has

described this well as a ‘common stock’ that contained songs from every conceivable source, from

Anglo-Celtic folk songs hundreds of year’s old to contemporary Tin Pan Alley parlour and 'event'

songs. There was an extraordinary array of musical approaches in the South, and this music was

found in many forms – sung by a solo singer with any kind of instrument or none, duet, jug band,

string band and jazz band.3 Highly original and regionally-specific interpretations of this common

stock are what are invariably found on the earliest Old Time and Race Records 78s, yet this is not

what is presented through the rhetoric used to sell this music.4 In the marketing, two completely

separate streams of Southern folk music are presented, one purely white and one purely black, a

separation that denies any possibility or history of the intermingling of the races, a bifurcation of a

shared tradition which becomes a revision of Southern history, and a segregation in keeping with

the race policy of the Jim Crow era. This segregation has largely been observed in studies of the

early years of blues, jazz and country music. While many studies have challenged the assumption of

segregated traditions, the organisational structure of music scholarship has often perpetuated this

3 Tony Russell, Blacks, Whites, and Blues (London: Studio Vista Ltd., 1970), 27. 4 Certain styles were of course considered the preserve of certain groups. The blues for example was certainly intrinsically linked to black culture, with whites adopting it self-consciously. But as Tony Russell and others have argued, the blues was not the most common music for Southern black musicians prior to the creation of Race Records; in fact while the blues can be traced back to the 1880s, the common stock was probably more widespread than the blues before the twentieth century. Russell, 31.

Introduction 5

segregation, the separate-but-equal status of Southern white and black music, by telling the story of

one stream or the other, missing the opportunity to compare the process of the transformation of this

shared tradition into discrete categories. Analysing the marketing rhetoric of Race Record and Old

Time side-by-side serves to keep the prior communal state of this music in mind, while

underscoring the way that the racial politics of entertainment during the Jim Crow era influenced

the commodification of each in different ways.

The verbal and visual rhetoric of these new marketing categories, presented in catalogues,

advertisements, window displays, and other promotional material, employed Southern images and

pre-existing musical and marketing traditions, to offer a new definition of Southern black and white

music. While heavily reliant on existing constructions of white and black musical culture as we

shall see, the creation of these catalogues involved the recasting of major cultural tropes and

resulted in an intertextual construct that was something new.5 The record industry's Old Time artist

remained at the mercy of Southern stereotypes, but these musicians were neither simply the pious

folk relics projected by folklorists nor the comic caricatures of the radio hillbillies, but rather more

complex characters, personified by the dignified mountain entertainer who sometimes sang

contemporary songs as well as traditional material and who was a product of both the modernist and

anti-modernist impulse. Likewise, the verbal and visual rhetoric of Race Records drew heavily on

existing models for selling black music, such as minstrelsy and songbooks of folklorists, and yet the

mostly sophisticated, professional, urban, vaudeville performers, who became the first Race

Records artists, and the music they made, also had a significant impact on the marketing images of

Race Records.6 While these rhetorics were decidedly Northern white conceptions, the fact that both

catalogues were created in response to the popularity of vernacular musical styles had a significant

impact on their marketing, and it is the matrix of cultural and commercial forces that makes these

constructs such interesting examples of the commodification of culture in the burgeoning consumer

culture of the 1920s. Put another way, the record industry's marketing imagery for these musics

ultimately combined well-worn stereotypes with modern images that were inspired by, and to some

degree produced by, this music and its practitioners, and this introduced a new version of Southern

black and Southern white musical culture into the national marketplace.

Specific studies have informed my way of thinking about the rhetorics used to sell Race Records

and Old Time. While it does not cover the creation of Race Records and Old Time marketing

5 My use of Julia Kristeva’s theory of intertextuality will be explained shortly.

6 While not all Race Records can be characterised in this manner, the first stars of Race Records were 'classic' blues or 'vaudeville blues' singers, such as Mamie Smith, Bessie Smith and Ethel Waters, and were professionals on the vaudeville circuit prior to their recording careers.

Introduction 6

rhetoric, David Suisman's account of the 'commercial revolution' in music in the early twentieth

century which transformed the music industry from a haphazard enterprise dominated by small-

scale publishing firms to a highly organised, transnational industry dominated by mass-producing

record companies using mechanical reproduction to mass-market music, provides us with a vivid

picture of the political economy of music in the early twentieth century. Suisman examines how the

music industry 'rationalized the business of musical culture according to the principles of industrial

manufacturing', allowing it to produce innovative products and advertising to cultivate and

consolidate new consumer markets.7 This completed the commodification of music and now sounds

could be manufactured, marketed and purchased like any other consumer good.8 More broadly,

Suisman's work underscores an important point about the industry in the 1920s: that as a relatively

new industry pedalling a relatively new product, the marketing and advertising of genres of music

to specific markets was a concept still in its infancy, and that this was an industry grappling with the

cultural and commercial potential and meaning of various musical styles.9 Broadening the variety of

entertainment available on phonograph records was justified using the rhetoric of democracy and

consumer choice, and initially both Race Records and Old Time were viewed as somewhat akin to

the 'foreign language’ records which catered to the large numbers of newly-arrived immigrants from

Europe and Asia in the 1910s and 1920s.10 Race Records and Old Time catalogues were also

designed for a specific group, and were similarly nostalgic, racialised formulations that were

considered marginal, niche, and often, regionally specific. Neither attained the status of the 'popular'

catalogues that contained the huge hits of the 1920s such as the 'symphonic jazz' of Paul Whiteman,

the sentimental 'torch' songs of crooners such as Gene Austin and Rudy Vallee, and Broadway and

movie tie-ins such as Al Jolson's 'Sonny Boy' (from 1928's huge 'talkie' hit The Singing Fool). Nor

were they as important to the corporate image of the leading companies as their highbrow

catalogues of classical music, however both new catalogues proved to have surprisingly strong

markets and assumed an importance beyond their initially tentative and marginal status.11

7 Suisman, 'The Sound of Money: Music. Machines, and Markets, 1890-1925' (PhD, University of Columbia, 2002), 2. 8 Suisman correctly notes that while this commodification was happening, music was being dematerialised at the same time, through new copyright law, which came to recognise music as intellectual property removed from physical forms. David Suisman, Selling Sounds: The Commercial Revolution in American Music (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009), 9. 9 Suisman also reminds us that the modern conception of marketing only took hold around the turn of the century. The shift in meaning of the term from simply, and literally, bringing things to market to speculating what an abstract consumer might want, 'any activity to create or appeal to a market', was a still a relatively new concept by the 1920s. Susiman, 'The Sound of Money', 5. 10 Karl Hagstrom Miller, Segregating Sound: Inventing Folk and Pop Music in the Age of Jim Crow (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010), 205. 11 Paul Whiteman's 'Whispering', a slow, polite ballad that owed little to jazz despite being called 'symphonic jazz', is considered to be the biggest selling record of the decade, selling 2 million copies. The biggest Race Records sold around 500,000. Andre Millard, America on Record: A History of Recorded Sound (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 107.

Introduction 7

Other studies have more directly addressed the construction of the Race Records and Old Time

catalogues. Karl Hagstrom Miller's work on the segregation of Southern music in the era of Jim

Crow importantly identifies three different groups – musicians, folklorists, and phonograph

companies – and analyses how their divergent and at times competing conceptions of the musical

culture of the South contributed to the commercial categorisation of Southern music as racially

segregated, separate streams of musical culture.12 Miller's work builds on the assertion made by

earlier historians and music scholars, such as Archie Green, Tony Russell, and Charles Joyner, that

there existed in the South a history of musical interaction and cross-pollination between white and

black that was denied and ignored by both the commercial segregation and folkloric definition of

this music. Through an investigation into the rise of the folklore movement from the 1880s, and the

changes in the minstrel tradition over the same period, he argues persuasively that the new folklore

definition of authenticity (in isolation from modern life), was combined with the minstrel

conception of authenticity (as a product of racial contact and interaction through the market), to

create ‘a series of mongrels that often tendered authentic minstrel deceits as authentic folkloric

truths’.13 His focus is on musical repertoire, and while the Old Time and Race Records catalogues

of the 1920s play only a small part in his story, and he spends very little time on record industry

promotional material and advertising (the primary sources of this study), my work draws on

Miller’s by identifying how these same three groups (musicians, folklorists, and phonograph

companies) contributed to the verbal and visual rhetorics used to sell these new discrete racial

categories of music to the public. The present study developed from a specific interest in how the

rhetoric of this advertising and promotional material functioned as an articulation and reinforcement

of the essentialist vision of Southern white and black music developed over this period.

While there are many histories of the record industry and of Race Records and Old Time, few have

delved deeply into the verbal and visual rhetorics used to sell these catalogues.14 There have been

several studies of Race Records advertising, which will be discussed in detail in Chapter Two, but

few that compare and contrast these with Old Time, or adequately account for the antecedents of

this material within an industry context.15 There is some very good work on the development of

12 Miller, Segregating Sound, 6. 13 Ibid. 14 Among the best treatments of the record industry during this era which do address Race Records and Old Time are: William Howland Kenney, Recorded Music in American Life: The Phonograph and Popular Memory, 1890-1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999); Suisman, Selling Sounds; Russell Sanjek, American Popular Music and Its Business: The First Four Hundred Years, Vol. 3: From 1900-1984 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988); Millard, America on Record; and Miller, Segregating Sound. 15 There have been more on Race Records, reflecting the level of advertising in the black press which was not mirrored at all for Old Time. These include: Mark K. Dolan, ‘Cathartic Uplift: A Cultural History of Blues and Jazz in the Chicago Defender, 1920-1929' (PhD, University of South Carolina, 1985); Mark K. Dolan, ‘Extra! Chicago Defender Race Records Ads Show South from Afar'. Southern Cultures (Fall 2007): 107 -124; Jeff Todd Titon, Early Downhome

Introduction 8

these new catalogues which does treat race, but for the most part these studies, when they do stretch

back to the 1920s, stick to the well-established narratives which centre around the major figures of

the entertainment industry – Ralph Peer, the head of recording at both OKeh then Victor, or radio

impresarios such as John Lair and George W. Hay who established the radio hillbilly – or else they

view this history through the work and lives of particular recording artists.16 These accounts offer

insightful commentary on the development of the segregated record catalogues and the relationship

these entrepreneurs had to the music and their recording stars, but they offer little analysis of the

marketing rhetoric of these new commercial categories.

When one’s goal is to delineate and analyse the production of cultural and commercial tropes used

in record industry advertising, the centrality of specific individuals recedes. There are no detailed

accounts of the process of drafting record industry advertising nor of the devising of marketing

strategies, we have merely snippets of information, anecdotal evidence and little else. We can make

educated guesses; for example it seems most likely that most of the Race Records advertisements

were drafted in-house and then sent to an advertising agency, which inserted the cartoons and

prepared them for the press, but beyond this very little is known. Regardless, the actions,

perceptions or prejudices of particular men cannot explain how or why an entire industry, in silent

consensus, utilised and adapted certain cultural tropes for the marketing and definition of these new

catalogues of recorded music.17 Rather, the way to unravel this process of cultural and commercial

production is with an analysis that weaves together several threads. First, there are the models for

advertising music by Southern whites and blacks already in use in the entertainment industry by the

1920s, such as those used for minstrelsy, vaudeville, sheet music and the Southern-themed music in

‘popular’ catalogues. All of these were important antecedents of the industry's marketing for Race

Records and Old Time and provided many of the images, stereotypes, and widely understood tropes

upon which it was based. Second, the corporate image concerns of record companies in the 1920s,

Blues (Urbana: University of North Carolina Press, 1977); and Ronald Clifford Foreman, Jnr., 'Jazz and Race Records, 1920-1932: Their Origins and their significance for the record industry and society' (PhD, University of Illinois, 1968). 16 These works include, Bill C. Malone, Singing Cowboys and Musical Mountaineers: Southern Culture and the Roots of Country Music (Athens and London: University of Georgia Press, 1993); Bill C. Malone and David Stricklin, Southern Music/American Music (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1979); Anthony Harkins, Hillbilly: A Cultural History of an American Icon (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004); Richard A. Peterson, Creating Country Music: Fabricating Authenticity (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997); Russell, Blacks, Whites, and Blues; Patrick Huber, Linthead Stomp: The Creation of Country Music in the Piedmont South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008); Wayne W. Daniel, Pickin’ on Peachtree: A History of Country Music in Atlanta, Georgia (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1990); Charles K. Wolfe, 'Nashville and Country Music, 1925-1930: Notes on Early Nashville Media and Its response to Old Time Music'. Journal of Country Music, 4 (Spring 1973): 2-16. 17 In his research into the practice in the 'Commercial Music Graphics' series in the John Edwards Memorial Foundation Quarterly Archie Green reveals the names of several men who were employed to write the ad copy for Old Time catalogues in the 1920s, but not much beyond this is known about them. More broadly, we know that for major campaigns Victor used Raymond Rubicam, one of the most successful ad-men of the era, but of course none of this yields insights into the decision making process behind the more prosaic practice of drafting ads and catalogues.

Introduction 9

and the cultural ideology that underpinned these concerns, played a crucial part in the construction

of these catalogues of music and their marketing. Third, the actions of both Southern whites and

blacks as artists play a significant role in this story. The self-promotional, or 'self commodification',

efforts of artists greatly influenced the images and language used by the industry to sell their

recordings and therefore this study, while not focusing on the lives and careers of musicians, does at

times examine the role of specific artists in the development of key tropes in this marketing

vernacular. Finally, the music fan and record-buying consumer also plays a role in this story, even in

this pre-market-research era. Suisman has argued that ‘the creation of modern musical culture was

not a consumer-driven phenomenon', that the industry was not responding to some expressed need

which only it could fulfil, and that it therefore had to create a market for its product.18 While this is

true of the modern music industry in its first years of development in the early twentieth century,

when its main job was to convince consumers of the benefits and convenience of mechanically-

reproduced phonograph recordings, the creation of both Race Records and Old Time in the 1920s

was, if not entirely consumer-driven, prompted by the local popularity of certain artists, and

significantly shaped by the enthusiastic response among record buyers to the initial recordings.

While OKeh's claim to be the pioneer in both the Race Records and Old Time markets, as presented

in the industry advertisements presented above, was correct, in neither case was it entirely OKeh’s

initiative to produce these records. Ralph Peer, OKeh's head of recording from 1920-1926, is widely

credited with being the man behind the creation of both Race Records and Old Time, and indeed he

was responsible for the recordings of both Mamie Smith and Fiddlin' John Carson, and yet in both

instances he was persuaded by an outsider that there was an untapped market for this music.19 In the

case of Race Records this outsider was Perry Bradford, a black songwriter and performer who had

considerable difficulty convincing any of the New York record labels to record one of his songs

with a black female singer.20 In the case of Old Time, the outsider was P.C. Brockman, a Southern

‘jobber’ and head of sales at OKeh’s largest Southern distributor, James A. Polk Inc., in Atlanta,

Georgia. He was, the story goes, in New York City’s Palace Theatre on Broadway watching a

newsreel that featured a fiddling competition when he made a note to record local Atlanta fiddler

John Carson.21 These stories, and the lives of these men, are undoubtedly fascinating, but what is

most remarkable about them is what they tapped into and what they showed the industry about the

18 Suisman, Selling Sounds, 15. 19 Peer initiated the first field recording in Atlanta in 1923, and it was here that Peer recorded Fiddlin’ John Carson at the behest of Brockman. Peer famously described the record as 'Plu perfect awful' and it is still debated whether he was he was referring to the recording or the music with this judgement. He also described Mamie Smith’s first record as 'The most awful record ever made' but quickly added, 'and it sold over a million copies'. Harkins, Hillbilly, 72. 20 Perry Bradford, Born with the Blues: Perry Bradford's Own Story (New York: Oak Publications, 1965), 29. 21 He then took this idea to Ralph Peer. Kenney, Recorded Music in American Life, 145.

Introduction 10

tastes of ordinary Americans. In both cases these initial recordings were runaway hits, with ‘Crazy

Blues' selling 75, 000 copies in a month and onto a million and a half, and ‘The Little Old Log

Cabin in the Lane’ selling several hundred thousand copies, creating a national market into which

nearly every major label moved within the next few years.22 The industry was completely taken by

surprise by the success of these two records – Ralph Peer claims they did not even assign the

Carson record a catalogue number – and OKeh's executives had to be convinced to pursue these

markets firstly by people whose involvement in the wider music community told them there was a

market for this music, and secondly, by consumers who responded enthusiastically to these

recordings and the many more that followed.23 The record industry knew very little about the music

– how to define, market, and sell it, even what to call it – and this colours the whole story of these

catalogues and the history of this music on record. Furthermore, this fact has an important impact

on the approach to the marketing of these records, because in effect the industry had somehow to

capture the popularity of this music and sell it back to consumers while at the same time using

imagery that adhered to its existing marketing strategies and corporate image. This dynamic, and

tension, informed the tenor and the vocabulary of Race Records and Old Time marketing.

This discussion of consumer involvement leads to the question of reception. While the focus in the

following pages is on the cultural and commercial context of the rhetoric used by the industry to sell

these new racialised categories of music to the public, such a project naturally leads one to

questions about the consumer response to these marketing strategies and images. The reception of

advertising by consumers is notoriously difficult to research, especially in this era that pre-dates

systematic market research. The success of the records and catalogues themselves, and the

consistency of record industry marketing imagery, may point to a degree of acceptance, perhaps

even a positive response, to the imagery used in record company advertising (there is at least no

evidence of public outcry against this advertising) or it may not. These facts may instead simply

indicate the prevailing popularity of the artists and musical genres contained in these catalogues,

rather than successful marketing. For the purposes of this study, while responses to the imagery of

Race Records and Old Time in the media, the industry, and in the case of Race Records, the black

leadership and among younger intellectuals of the 'New Negro' generation, are considered, the

questions of most interest to me are how the industry settled on these images, what informed both

the images themselves and the decision to use them, and what contributed to their final shape.

Without inside knowledge of this decision-making process, this study relies predominantly on a

rhetorical analysis and industry contextual study to suggest answers to these questions.

22 Miller, Segregating Sound, 192. 23 Huber, Linthead Stomp, 43.

Introduction 11

The research for this project involved the analysis of as much 1920s record industry promotional

material as I could find. This led me to the rich holdings of record industry material at both the

Library of Congress and the Wilson Library’s Southern Folklife Collection at the University of

North Carolina, Chapel Hill. At the Library of Congress I studied the Jim Walsh Collection,

bequeathed to the Library of Congress by one of the greatest collectors of acoustic and early electric

era recordings and related material. This collection, which includes 40, 000 discs, 500 cylinders,

and 23 phonographs, contains many boxes of record industry catalogues, supplements, promotional

material and ephemera from many labels including: Brunswick, Columbia, OKeh and Odeon. At the

Southern Folklife Collection this range was expanded with many boxes of material relating to

Victor, Vocalion, OKeh, Brunswick, Columbia, Paramount and Black Swan. Much of this material

came from the John Edwards Memorial Foundation (JEMF) holdings, an archive built around

Australian John Kenneth Fielder Edward’s remarkable collection of ‘Golden Age’ country music

78s and promotional material. In the 1950s this collection was widely considered the largest outside

of America and equal to any within it, and when in 1960 the Sydney Old Time enthusiast’s life was

tragically cut short by a car accident, Edward's collection was bequeathed to American record

collector Eugene Earle.24 Earle, with a distinguished group of American music scholars including

Archie Green, Fred Hoeptner, Ed Kahn, and D.K. Wilgus, established the JEMF to honour Edward's

legacy. This foundation went on to establish the JEMF Quarterly, a publication that included many

seminal studies of early country music, including Archie Green's pioneering 'Commercial Music

Graphics' series, one of the first efforts to offer a cultural analysis of Old Time and Race Record

catalogues and advertising.25

Beyond these two principal archives, another central source used in this study is the Talking

Machine World (TMW), the main trade journal of the record industry through the 1920s. This

journal serves as the primary source for two chapters here, as no previous study has attempted an in-

depth analysis of this forum for the record industry. Extensive research in newspapers was also

undertaken, especially the black press, in which nearly every major player in the Race Records

market advertised heavily during this era.26 Finally, due to the resurgence of interest in this music

24 Edwards spent many years mining the libraries of Australian radio stations, swapping new country records he had ordered from the US for old 78s of the Carter Family, Jimmie Rodgers, and many others. He then established long lasting relationships with other collectors in the US and many artists themselves. Sara Carter was known to refer to her pen pal as 'Our John in Australia'. Jazzer Smith, ‘The Long Journey Home: The Hitherto Untold Story of a Remarkable Man Called John Edwards’. JEMF Quarterly v. 21 77/78 (1985): 85-88, 88. 25 I have since sourced many other articles from the JEMF Quarterly for this study. 26 Variety issues throughout the 1920s were also examined. To further explain my methodology, the two holdings which were my principle cites of research contained a vast range of record industry catalogues and promotional material and covered the great majority of record companies in operation during this time. I photographed all of this material,

Introduction 12

and the recording process of Race Records and Old Time among folklorists, musicologists and

enthusiasts in the 1960s and 70s, there are many interviews with key figures in the creation of the

first Old Time and Race Records which shed light on some aspects of the marketing process and

these have been drawn upon in various places throughout this study.27

This interpretation of record industry promotional material necessarily involves an engagement with

the problems surrounding, and limitations of using, advertising as a primary source. Historians of

advertising and consumer culture have lamented the paucity of work that explores advertising as a

source for cultural history.28 When advertisements are used there is often the feeling that, as Daniel

Pope has suggested, ‘Too often (cultural critics) divorce advertisements from the business

conditions and marketing strategies behind them.’29 Kimberly Ann Paul, in her study of context and

culture in print advertising of the 1920s, stresses ‘the importance of situating an advertisement in its

historical setting. Within this context, authorial intent and meaning can be studied, offering multi-

layered and robust interpretations.’30 My intention is to situate the marketing of Race Records and

Old Time in both an industry context, with particular attention paid to the commercial concerns of

the industry at the time of the inception of these catalogues, and within the historical context, and

rhetorical idiom, of the marketing imagery used to sell both Southern black and white music.

and used these photographs as the basis of a content assessment of the material, which involved cataloguing them by various themes, by company and by year. As for the newspaper articles and advertisements pertaining to either Old Time or Race Records, I examined every item that contained the search terms Race Records, Old Time, blues or hillbilly from 1919-1930. I did further searches with more specific search terms, and with wider time periods, to check my results and compare the content to different periods. I then catalogued these in the same way as the photographs of the catalogues and promotional material. In regards to The Talking Machine World (TMW) I studied every issue from 1920-1930 and again catalogued every article and advertisement that pertained to either Race Records and Old Time, and many other relevant topics, such as the activities of key industry figures etc., and again the findings here represent a content assessment, what journalism/media historian Carolyn Kitch, using Marion Marzolf's concept, defines as 'a selection of representative words and images analysed with particular attention to their cultural and historical context'. Carolyn Kitch, 'Family Pictures: Constructing the “Typical” American in 1920s Magazines'. American Journalism 16 (Fall 1999), 60. 27 These include: Arthur Edward Satherley, interview by Norm Cohen and G. Earle, with Ken Griffis and Bill Ward present (June 12, 1971) tapes FT-1647/1 and 2; FT-1648. Southern Folklife Collection, Manuscripts Department, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill; David Evans ‘Interview with H. C. Speir.’ JEMF Quarterly No. 27 (Autumn 1972): 117-121; Mike Seeger, 'Interview with Frank Walker,' in Josh Dunson and Ethel Raim, eds, Anthology of American Folk Music Handbook (New York: Oak Publications, 1973); Alfred Shultz, interview by Gayle Jean Wardlow, (August 2, 1969) Cassette TTA-01812/UU. Courtesy of The Centre for Popular Music, Murfreesboro, Texas; Harry Charles, interview by Gayle Jean Wardlow, (1960) reels #TTA-0182 J/UU and TTA-0182 K/UU. Courtesy of The Centre for Popular Music, Murfreesboro, Texas; Mayo Williams interview by Stephen Calt and Gayle Jean Wardlow. in Stephen Calt, ‘The Anatomy of a “Race” Label Part 11,' and Stephen Calt and Gayle Jean Wardlow, 'The Buying and Selling of Paramounts Part 3'. Gayle Jean Wardlow interview with H.C. Speir, in Chasin' That Devil Music: Searching for the Blues (San Francisco: Miller Freeman Books, 1998). 28 Roland Marchand, Advertising the American Dream: Making Way For Modernity, 1920-1940 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985); Richard Wightman Fox and T. J. Jackson Lears, eds, The Culture of Consumption: Critical Essays in American History, 1880-1980 (New York, Pantheon Books, 1983); Kimberly Ann Paul, 'The More We Know, the More We See: Context and Culture in 1920s Print Advertising'. (PhD, University of Texas at Austin, 2001). 29 Daniel Pope, The Making of Modern Advertising (New York: Basic Books, 1983), 10. 30 Paul, 3.

Introduction 13

One of the central issues with using advertisements as a primary source in cultural history is to what

degree one can understand the advertisement as a mirror of the times in which it was published. It is

important to recognise that advertisements are projections, and reflect more about those that devised

them than anything else. In so far as they are products of their time and projections used to attract

certain segments of the public through imagery and text designed to be appealing to them, there is

certainly a case to be made that advertisements reflect something of the times in which they were

devised. Advertising historian Roland Marchand’s solution is to suggest that, while one can only

ever read the advertisement as a 'distorted, selected refraction' of reality, 'determined not only by the

efforts of advertisers to respond to consumers desire for fantasy and wish-fulfilment but also by a

variety of other factors', it is 'in their efforts to promote the mystique of modernity in styles and

technology, while simultaneously assuaging the anxieties of consumers about losses of community

and individual control that they most closely mirrored historical reality – the reality of a cultural

dilemma’.31 It is one my central contentions that the record industry was one such national

advertiser engaged in this paradoxical strategy.32 In the odd position of needing to respond to, and

expand, a market about which they knew little, the predominantly Northern white middle-class men

who ran the record industry relied mostly on Southern talent scouts to suggest which artists to

record, and likewise these men turned to what they could find already in use for the marketing of

black music and Southern white music. Largely eschewing advertising agents, except in the case of

major campaigns – in the 1920s Victor used Raymond Rubicam, one of the most prized ad agents of

the era who also devised campaigns for Wanamaker, Montgomery Ward and Rolls Royce, for their

Red Seal and Victrola ads – the record industry’s marketing of Race Records and Old Time looked

to the advertising of minstrel shows and vaudeville theatres, the covers of sheet music and song

books, as well as the visual and verbal tropes representing Southern blacks and white Appalachian

mountaineer culture already in the popular consciousness, courtesy of popular fiction and the

press.33 This is not to say that perceptive copy did not appear about this music, for example Archie

Green has singled out Victor's James Edward Robertson for his particularly sensitive descriptions of

songs in early Old Time catalogues, and as we shall see, the rhetoric of these catalogues owed much

31 Marchand, Advertising the American Dream, xvii and xxi. 32 Other studies in connected fields, such as Carolyn Kitch, 'Family Pictures: Constructing the “Typical” American in 1920s Magazines', and Lisa Jacobson, Raising Consumers: Children and the American Mass Market in the Early Twentieth Century, have explored this issue. Kitch uses the theory of hegemony to describe the way in which the Saturday Evening Post and Good Housekeeping magazine both reflected and produced a version of the family that would last throughout the century. Jacobson is careful to avoid a ‘top-down’ approach, which views 'the expansion of consumer markets largely as a result of corporate strategies to rationalize demand'. She concluded 'cultural change did not merely reflect the economic imperatives of corporate elites', and wished to restore agency to non-corporate elites. My study is closely aligned to this perspective, in that a central tenet of the argument here is that the record industry was responding to consumer demand and the musical taste of audiences, while simultaneously shaping and producing cultural meaning through economic imperative and the negotiation of segregation. Jacobson, Raising Consumers: Children and the American Mass Market in the Early Twentieth Century (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004), 3. 33 Suisman, Selling Sounds, 115.

Introduction 14

to the music and the artists themselves, however this marketing was from the outset couched in the

tropes of pre-existing models.34

This study aims to understand the record industry’s strategic employment of specific marketing

rhetoric to persuade the consumer to buy the records in Race Records and Old Time catalogues, and

therefore can be described as a rhetorical analysis. To elucidate how this rhetoric functioned, that is

how this marketing employed previous models for marketing the music of Southern whites and

blacks and yet created something new out of this available material, this study also draws on other

approaches to the analysis of 'texts' such as those used in post-structuralist semiotics and the

‘linguistic turn’ in historiography. While much attention was paid in post-structuralist semiotics to

how meaning is formed when reading a 'text', and although the focus in this study is less on

reception and more on the cultural and commercial production of marketing tropes, certain post-

structuralist theories are useful in explaining how this marketing rhetoric functioned within the

commercial and cultural discourse of the phonograph industry. One potentially useful way of

explaining how this marketing rhetoric worked is the through the concept of bricolage, a theory

devised by the father of French post-structuralism Jacques Derrida, building on the work of de

Saussure. This theory argues that all signs (a discrete unit of meaning that can be a word, image,

gesture, sound among many other things) are ‘constructed of fragments of prior significations,

being meaningful by virtue of the traces that each fragment carries of previous uses’.35 Bricolage,

literally meaning construction through whatever is in hand, is a way then to describe how signs

recombine previous meanings to create new meaning, and this is an important aspect of both Race

Records and Old Time marketing. Both drew heavily not only on contemporary representations of

the ‘hillbilly' or ‘blues' musician, but retained and reconfigured previous meanings as it recombined

elements to create new meanings. However, the conceptual tool that perhaps helps us best

understand the dynamics inherent in the marketing imagery of Race Records and Old Time, and is

drawn upon in the subsequent analysis, is the literary theory devised by Julia Kristeva of

intertextuality. Somewhat aligned to Derrida's bricolage, Kristeva's intertextuality is based in

literary theory but has been effectively applied to mass media by other scholars, such as Kimberly

Ann Paul and those included in Ulrike H. Meinhof and Jonathan Smith's collection Intertextuality

and the Media, and offers a useful way to describe how advertising works.36 Kristeva's theory

describes, as Paul neatly puts it, ‘the influence of text upon text upon text – that a text always refers

34 Archie Green, 'Commercial Music Graphics: Four'. JEMF Quarterly, Vol. 4, pt.1, No. 9 (March, 1968):9-12, 10. 35 Jacques Derrida, 'Structure, Sign, and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences' (1972), reprinted in Robert Davis, Robert Con and Ronald Schliefer, eds, Contemporary Literary Criticism: Literary and Cultural Studies (New York: Longman, 1989), 229-248. 36 Paul, 'The More We Know, the More We See'; Ulrike H. Meinhof and Jonathan Smith, eds, Intertextuality and The Media: From Genre to Everyday Life (New York: Manchester University Press, 2000).

Introduction 15

back to a previous text', and underscores not only the point that to understand and legitimately

interpret any text, one must understand its antecedents, its context and its referents, but as well that

a text is essentially one articulation in an ongoing discourse, both historical and cultural.37 The three

components of this concept of intertextuality are the actual text, the pretext, and the quotation. The

actual text is what is being read or viewed. The pretext is made up of any and all possible 'texts' that

are woven into the actual text – deliberately or not – by both the creator and the reader. The

quotation is an actual recognisable reference to a pretext – for example, the use of minstrelsy

figures – bug-eyed, wide-mouthed, 'Zip Coon' and 'Jim Crow' caricatures – in the cartoons

associated with the marketing of Race Records. Julia Kristeva’s theory is a useful way to explain

how this rhetoric was situated within a long tradition, and ever-evolving vocabulary, of rhetoric

used to sell white and black Southern music. This rhetoric did not simply make allusions to

recognisable rhetorical devices, but re-configured them to create something new. Furthermore, the

cartoons, illustrations and printed images of this marketing were as deeply intertextual as the copy

that accompanied them and intertextuality is a useful theory here because it acknowledges the

language of visual imagery.

The central question of this study – how and why the record industry constructed the version of

Southern vernacular music that it did in the early 1920s – is as much concerned with ideas about the

South and its inhabitants as it is about the record industry and its motivations. To answer this

question then this study engages with existing literature in several inter-related fields: the

historiography on Southern cultural stereotypes such as 'poor whites', 'hillbilly', 'happy slave', 'urban

dandy', ‘mammy’ and 'blues shouter'; the work of cultural and music historians who have elucidated

the history of Southern vernacular music in American society preceding and following the 1920s;

the literature on consumer culture in the early twentieth century; work on the parallel yet distinct

process of commercialisation and cultural clash in radio; and the work of advertising historians who

have suggested approaches to the problematic interpretation of advertising as a mirror of society.38

37 Paul, 45. 38 For work on the construction and function of Southern cultural stereotypes see: Harkins, Hillbilly; Mark Wray, Not Quite White: White Trash and the Boundaries of Whiteness (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006); J. Wayne Flynt, Dixie’s Forgotten People: The South’s Poor Whites (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1980); and W. Fitzhugh Brundage, The Southern Past: A Clash of Race and Memory (Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2005). For work on Southern musical culture see, Archie Green, 'Hillbilly Music: Source and Symbol'. The Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 78, No. 309 (July-September 1965): 204-228; Lawrence Levine, Black Culture and Black Consciousness (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007); Lawrence Levine, Highbrow/Low Brow: The Emergence of Cultural Hierarchy in America (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1988); Charles Joyner, Shared Traditions: Southern history and folk culture (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1999); Malone, Singing Cowboys and Musical Mountaineers; Tony Russell, Blacks, Whites, and Blues; Le Roi Jones, Blues People (New York: William Morrow and Co., 1963); Marybeth Hamilton, In Search of the Blues (London: Jonathan Cape, 2007); and Geoff Mann, ‘Why does Country Music Sound White? Race and the Voice of Nostalgia’. Ethnic and Racial Studies Vol. 31 No. 1 (January, 2008): 73-100. For work on radio in the 1920s, see Susan Smulyan, Selling Radio: The Commercialization of American Broadcasting, 1920-1934 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1994);

Introduction 16

As the reification of certain ideas surrounding black and white Southern musical culture, Race

Records and Old Time contributed substantially to the formation of Southern whiteness and

blackness in the blossoming consumer culture of the 1920s. Contrasting the development of each of

these contributes to our understanding of this formation and the record industry’s role in this

process. In the scholarship on whiteness, some attention has been paid to the confluence of

Southern segregation and consumer culture in the first decades of the twentieth century, but few

have noted the peculiar case of the record industry in this context.39 Grace Elizabeth Hale discusses

the ‘common whiteness’ and ‘mass racial meanings’ that white Southerners defined through

consumer culture, and which were made possible through new visual technologies and cultural and

commercial sites where these meanings could be acknowledged. Among these she lists

‘photography and motion pictures and changes in lithography, engraving, and printing as well as the

construction of museums, expositions, department stores, and amusement parks'.40 The phonograph

does not figure in her analysis, but not only does the phonograph represent another site in which

these new mass racial meanings were being constructed and defined, it was also an industry that

utilised all of the new technologies and entertainments she lists in their construction. The

phonograph industry was a Northern-based industry, which perhaps is why Hale excludes it from

her study of Southern segregation, but of course these new mass racial meanings were part of a

national project at this time, as segregation took place across the US whether by custom or by law.41

Furthermore, the negotiation of Southern segregation laws guided the national marketing strategy

for these two new phonograph industry products, Old Time and Race Records, because the greater

part of the market for these recordings was presumed to reside in the South.

The other reason perhaps why Hale overlooks the phonograph in her analysis is that her focus is on

Shawn Vancour, 'Popularizing the classics: radio’s role in the American music appreciation movement, 1992-34’, Media Culture & Society (2009): 289; Charles Wolfe, A Good Natured Riot: The Birth of the Grand Ole Opry (Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 1999); and Tracey E.W. Laird, Louisiana Hayride: Radio and Roots Music Along the Red River (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005). On consumer culture and advertising, see: Marchand, Advertising the American Dream; Paul, 'The More We Know, The More We See’; Pamela Laird, Advertising Progress: American Business and the Rise of Consumer Marketing (Baltimore and London: John Hopkins University Press, 1998); Susan Strasser, Satisfaction Guaranteed: The Making of the American Mass Market (New York: Pantheon Books, 1989); Fox and Lears, eds, The Culture of Consumption; and Stuart Ewen, Captains of Consciousness: Advertising and the Social Roots of the Consumer Culture (New York: McGraw Hill, 1976). 39 Works on whiteness that have discussed the period: Grace Elizabeth Hale, Making Whiteness: The Culture of Segregation In The South, 1890-1940 (New York: Pantheon Books, 1998); David R. Roediger, The Wages of Whiteness: Race and the Making of the American Working Class (London: Verso, 1991); George Lipsitz, The Possessive Investment in Whiteness: How White People Profit From Identity Politics (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1998); Matthew Pratt Guterl, The Color of Race in America: 1900-1949 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2001); and Vron Ware and Les Black, Out of Whiteness (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002). 40 Hale, Making Whiteness, 8. 41 On segregation and resistance to it in the North see Thomas Sugrue, Sweet Land of Liberty (New York: Random House Publishing Group, 2009).

Introduction 17

‘visual’ imagery and the phonograph has featured in the literature on race predominantly by virtue

of its contribution to new ‘aural’ definitions of whiteness and blackness. This tendency is

understandable. Scholars such as Lisa Gitelman and Mark M. Smith have explored the way in

which the record industry from its inception both destabilised prior racial signification, because one

could no longer see the race of the performer, and by inscribing new oral racial markers, racialised

sounds in new ways. Gitelman asks 'what happens to the love and theft of blackface when there is

no face?' and answers that new kinds of aural markers of race were developed in response to the

apparent colour-blindness of recorded sound.42 The 'coon song', one of the biggest crazes of the

acoustic era, became popular at a time, the turn of the century, when the minstrel show was no

longer a widespread popular entertainment, and this racialised performance was predicated on the

fact that listeners could hear race. Musical features such as syncopated rhythms and even the sound

of the piano in popular music became new markers of blackness in popular music. Mark M. Smith

similarly argues that 'record companies…helped accelerate a racial politics of sound, popularized

the idea of the disembodied voice, and separated race from the eye and thereby endorsed the notion

that racial identity could be heard, sold, and consumed'.43 Both the radio and the phonograph

industries had to find ways to signify race through voice, instrument, musical style, etc., and this

aural dimension was an important part of the industry’s promotion of an essentialist definition of

race. But the phonograph was not only an aural medium. The fact of its aural ambiguity only

heightened the need to visually encode and reinforce racial markers, and the phonograph industry

advertised heavily.44 The industry leader, Victor, was the single largest magazine advertiser in the

country in 1923 and the fourth-largest newspaper advertiser.45 Therefore, this study can be seen as

part of an effort to understand the visual representation of race devised by the record industry, but

this focus does not aim to suggest that the segregated catalogues of the 1920s were the only, or even

first, contribution the record industry made to the racialisation of popular music in the early

twentieth century.

In Geoff Mann’s work on country music and whiteness in the post-World War II period, he asks

'Why does country music sound white?' and suggests that 'it is perhaps worth considering the

possibility that something claiming the status of “white culture”, something like a purportedly

American whiteness, however historically baseless, is not reflected in country music, but is, rather,

42 Lisa Gitelman, Scripts, Grooves, and Writing Machines: Representing Technology in the Edison Era (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999), 124. 43 Mark M. Smith, Sensing the Past: Seeing, Hearing, Smelling, Tasting, and Touching in History (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), 55 44 In fact its aural ambiguity was sometimes exploited for covert crossings of the colour-line, and certain acts, such as the Mississippi Sheiks, a black group led by the Chapman brothers from Jackson, Mississippi, were featured in both Race Records and Old Time catalogues. 45 Suisman, Selling Sounds, 115.

Introduction 18

partially produced by it'.46 This contention that the country music industry in fact produces

whiteness goes to the heart of the argument of this study, which looks at a period far earlier than

Mann’s. Country music was producing whiteness, and calling people to their whiteness, long before

it was even called country music, right from the beginning of the Old Familiar Tunes catalogues of

the mid-1920s. The industry’s concurrent definition of 'blackness' in Race Records likewise

produced a blackness, a commercial category of Southern blackness, that allowed the black

musician some involvement in the commodification of Southern black musical culture, but a role

defined and accompanied by images that conformed to forms of blackness acceptable in 1920s

society.47

The 1920s was a remarkable decade for the commodification of Southern vernacular black and

white music to take place in. In a decade that on the one hand was presaged by the 1919 race riots,

and was characterised by a general consternation over the ‘Great Migration’ of the Southern black

population, and on the other, included the Scopes Trial and the scandal of the economic and cultural

indigence of the Southern rural farmer, selling Southern black and white musical culture in any

form in the 1920s would appear to have been no easy task. The historical consensus on the 1920s is

that the era was defined by paradox and countervailing impulses: that in this era of rapid change and

incredible excitement about all things modern, there was an equally strong current of rejection of, or

revulsion from, modernity. Cultural historians have seen this ambivalent mood, and more

specifically the deep mistrust and resistance to modernity, reflected in disparate movements such as

prohibition, fundamentalism, nativism, the revitalised Ku Klux Klan, and in events such as the

backlash against urbanite Al Smith’s presidential campaign in 1928.48 The support for many of

46 Mann, 'Why does Country Music Sound White? Race and the Voice of Nostalgia'. 75. 47 Minstrelsy, a Northern and white creation has been characterised in terms of ‘love and theft’ by Eric Lott in his influential book of that name. Eric Lott, Love and Theft: blackface minstrelsy and the American working class (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995). By the 1920s however, minstrelsy had long ceased to be solely a white performance, with black minstrels dominating the dying form. For more on minstrelsy, see John Strausbaugh, Black Like You: Blackface, Whiteface, Insult and Imitation in American Popular Culture (New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Penguin Group, 2006); David Roediger, The Wages of Whiteness: Race and the Making of the American Working Class (London: Verso, 1999); William John Mahar, Behind the Black Cork: early blackface minstrelsy and Antebellum American black culture (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1999); Robert Toll, Blacking Up: the minstrel show in nineteenth century America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1974); W.T. Lhamon, Raising Cain: blackface performance from Jim Crow to Hip Hop (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1998); Amy Schrager Lang, ‘Jim Crow and the Pale Maiden: Gender, Color and Class in Stephen Foster’s “Hard Times”', in Reading Country Music: Steel Guitars, Opry Stars, and Honky-Tonk Bars, ed. Cecelia Tichi (Durham: Duke University Press, 1998); and Nick Tosches, Where Dead Voices Gather (London: Little, Brown and Co., 2001). 48 See Lawrence Levine, The Unpredictable Past: Explorations in American Cultural History (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993); T.J. Jackson Lears, No Place of Grace: Antimodernism and the transformation of American Culture: 1880-1920 (New York: Pantheon Books, 1981); Miles Orvell, The Real Thing: Imitation and Authenticity in American Culture, 1880-1940 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1989); Marchand, Advertising the American Dream; Tracey E.W. Laird, Louisiana Hayride: Radio and Roots Music Along the Red River (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005); George E. Mowry, The Urban Nation: 1920-1960 (New York: Hill and Wang, 1965); Nathan Miller, New World Coming: the 1920s and the Making of Modern America (New York: Scribner, 2003); Richard Hofstadter, The Age of Reform: From Bryan to F.D.R. (New York: Alfred A Knopf, 1966); Brundage, The

Introduction 19

these movements came from new city dwellers as well. Levine has argued that these causes

represented ‘a real or symbolic flight from the new America back to the familiar confines of the

old.’49 Indeed, the folksy, front-porch style of both of the winning presidential candidates of the

1920s, Harding and Coolidge, has been seen as further evidence that in this decade of rapid

modernisation, there was an ever-present pull in the opposite direction, a deep desire to hold on to

the values of the past.50 Levine suggests there was a ‘tension’ between the old and new, individual

and society, within every American in the 1920s.51 I would add the tension between rural and urban,

and perhaps North and South, to this list of major preoccupations of the era.

This ambivalence towards modernity involved a deepening of the nostalgia for, and of the

mythology surrounding, the ‘Old South' in the first decades of the twentieth century. Although not

new in 1920, indeed ever-present throughout Reconstruction and the Jim Crow era, the version of

the idealised American past that seemed to focus so intently on the antebellum ‘Old South’ became

institutionalised, and again ironically modernised at this time, through new commercial ventures,

government-sponsored commemoration, and the burgeoning consumer culture.52 I will argue in

subsequent chapters that while historians have tended to focus on radio or the nascent film industry

as embodiments of this ambivalence towards modern society in the 1920s, there is no more potent

expression of the nostalgic and contradictory nature of the era than the immense popularity of both

Race Records and of Old Time. Although products of the success of mass production and

consumerism, and of a technology still very much in its infancy – the transition from acoustic to

electrically-powered phonographs occurred in 1925, after the establishment of both of these

catalogues – these catalogues were marketed as a return to tradition, a preservation of traditional

culture, and as a conservative force, allowing the displaced Southerner and the urban Northerner to

re-establish some links to their pasts. This marketing served to dress up this modern music, and this

modern phenomenon of a commodified, segregated, electrically re-produced Southern music, in the

guise of tradition and nostalgia for a past that, it was strongly implied, at least in the case of Old

Time, no true American could do without.

Chapter One looks at the content of record label catalogues prior to the creation of Race Records

and Old Time and analyses the first attempts by the record industry to include Southern vernacular

Southern Past; Pete Daniel, Standing at the Crossroads: Southern Life Since 1900 (New York: Hill and Wang,1986); Tara McPherson, Reconstructing Dixie: Race, Gender, and Nostalgia in the Imagined South (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003); and David E. Whisnant, All that is Native and Fine: The Politics of Culture in an American Region (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1983). 49 Levine, The Unpredictable Past, 197. 50 Miller, 135. 51 Levine, The Unpredictable Past, 199. 52 For commemoration and Southern tourism see Brundage, The Southern Past.

Introduction 20

music in their ‘popular’ catalogues. It argues that the new folkloric sheen that Southern vernacular

music gained in the 1910s and 1920s provided the phonograph industry with the tools to market this

music as culturally important as well as novel, and furthermore, that this early marketing of

Southern vernacular music continued to influence the industry’s approach to Race Records and Old

Time in the 1920s. Chapter Two analyses the Race Records advertising placed in the black press by

the American record industry in the 1920s. The record companies advertised extensively in the

black press, with the knowledge that some of these newspapers, in particular the Chicago Defender,

had a wide circulation in the South. Indeed this amounted to the industry's sole avenue for reaching

the black market for Race Records. This chapter offers an interpretation of the verbal and visual

rhetoric used in these advertisements and argues that, contrary to previous studies that have read