‘The rich... should give to such an extent that it will hurt’: ‘Conscription of Wealth ’ and...

Transcript of ‘The rich... should give to such an extent that it will hurt’: ‘Conscription of Wealth ’ and...

DAVID TOUGH

‘The rich . . . should give to such anextent that it will hurt’: ‘Conscriptionof Wealth’ and Political Modernism inthe Parliamentary Debate on the 1917

Income War Tax

Abstract: The parliamentary debates on the Income War Tax in the summer of1917 were marked by fierce criticisms from Liberal members who argued that thetax measure fell short of the ideal of ‘conscription of wealth’ that had been in widecirculation in the months leading up to the debate. Scholars have repeatedly pointedout that ‘conscription of wealth’ rhetoric, which attempted to link the unfair sacrificesof the war effort to the need for income taxation, and revealed a rapidly polarizingpolitical climate at the end of the war, was the key inspiration for the introductionof the Income War Tax. However, the use of similar rhetoric by parliamentarians,and the call for ‘radical’ taxation across political differences, suggests that somethingelse – a shared desire for a modernist ‘break from the past’ – was at work in thedebate.

Keywords: First World War, dominion, conscription, taxation, modernism,

hegemony, Parliament, radical

Resume : Les debats parlementaires sur la Loi de l’impot de guerre sur le revenu, a l’ete1917, ont ete marques par la critique feroce des deputes liberaux selon qui la mesurefiscale n’atteignait pas l’ideal, abondamment relaye dans les mois qui ont precede ledebat, d’une « conscription de la richesse ». Les chercheurs ont regulierement fait valoirque cette rhetorique de la « conscription de la richesse », qui tenta d’associer les sacrificesinjustes faits au nom de l’effort de guerre au besoin d’avoir un impot sur le revenu et quirevela une polarisation croissante du champ politique a la fin de la guerre, fut la princi-pale source d’inspiration derriere l’introduction de la Loi de l’impot de guerre sur lerevenu. Toutefois, l’emploi d’une rhetorique semblable par les parlementaires et lesdemandes pour un regime d’imposition « radical » par-dela les lignes de parti suggerentqu’autre chose – un desir commun de rompre avec le passe dans l’esprit du modernisme –fut a l’œuvre dans le debat.

Mots cles : Premiere Guerre mondiale, dominion, conscription, imposition,

modernisme, hegemonie, Parlement, radical

The Canadian Historical Review 93, 3, September 20126 University of Toronto Press Incorporated

doi: 10.3138/chr.640

The First World War was at its grimmest in the summer of 1917, withmore than 300,000 Canadians soldiers having been sent to WesternEurope, more than 100,000 of whom had been killed or injured, anda controversial decision to conscript more men to serve overseas underconsideration, when some very excited words were said in Parliamenton the subject of income taxation.1 A vicious fire having destroyed thecentre block of the Parliament buildings on Wellington Street a yearand a half earlier (on 13 February 1916), the members were meeting ina makeshift chamber in the lobby of the Victoria Memorial Museum onMcLeod Street, where the Commons would convene for the remainderof the war (figure 1). On 25 July Thomas White, the Conservative min-ister of finance, presented the bill to create the Income War Tax – thedominion’s first income tax and its second direct tax, following theintroduction of the Business War Profits Tax a year earlier – and overthe next few weeks Liberals who were in favour of income taxationcriticized the bill in consciously intemperate language.

A few excerpts from the speeches of these Liberal members illustratethe tone of their rhetoric in the debate. George Graham, a veteran ofWilfrid Laurier’s Cabinet, commented during second reading of theBill on 2 August that he hoped the minister of finance would ‘increasesomewhat the amount of taxes on these men. I do not want to use theword ‘‘somewhat,’’ but I would say to increase radically the taxes onthe large incomes.’2 Later, during third reading on 17 August, othermembers spoke similarly. Charles Murphy, another Laurier-era Cabinetveteran, hoped that White would amend the bill to ‘provide for a moreequitable distribution of this Income Tax, and [to] see that those inreceipt of large incomes shall pay a much larger percentage than theyare going to pay under the present measure.’3 And Michael Clark, theLiberal member for Red Deer, claimed, ‘I know millionaires who haveexpressed their very highest satisfaction with this income tax, and Ido not think that is a good compliment to the tax. I would lower thesatisfaction of these gentlemen if I were in the position of the minister;I would give them less satisfaction and more taxation.’4 FrederickForsyth Pardee, the Liberal whip, complained, ‘There is no conscrip-tion of wealth here,’ and called the tax ‘a flea-bite; a mere cheese-paring.’ Lamenting that the tax ‘does not take from men enough tomake it hurt,’ Forsyth said, ‘The rich man and the rich corporation

1 Canada, Canada Year Book, 1916–1917 (Ottawa: King’s Printer, 1917), 639, 688.2 Canada, House of Commons Debates (2 Aug. 1917), p. 4108 (George Graham).3 Canada, House of Commons Debates (17 Aug. 1917), p. 4652 (Charles Murphy).4 Canada, House of Commons Debates (17 Aug. 1917), p. 4641 (Michael Clark).

‘Conscription of Wealth’ and Political Modernism 383

who are protected by the men who are fighting our battles at the frontshould give to such an extent that it will hurt.’5

This rhetoric is surprising and unexpected to anyone familiar withliberal political culture. The role of legislatures is to protect the peoplefrom excessive and abusive taxation; liberal government presumesthat the goal of good legislation is satisfaction. It is therefore rare tohear legislators at any time call for ‘more taxation.’ In this case, politi-cians are not only calling for an increase in taxation but for taxationthat ‘will hurt,’ that will give ‘less satisfaction’ to those who pay it. Itis also notable that a former Cabinet minister would use the wordradically to lend weight to his position. The word reflects Graham’sconscious intent to say something provocative. The members’ speechrepresents a direct and self-conscious challenge to liberal presumptions

5 Canada, House of Commons Debates (17 Aug. 1917), p. 4639 (Federick ForsythPardee).

figure 1 The House of Commons photographed on 18 March 1918 in the

Victoria Memorial Museum. (No image is available for the 1917 session).

Source: PA-139684, Arthur Beauchesne Fonds, Library and Archives Canada.

384 The Canadian Historical Review

about the purpose of taxation. As Forsyth’s reference to ‘the men whoare fighting our battles at the front’ suggests, this was an exceptionaldebate about taxation because it was also – if not primarily – aboutmilitary service and sacrifice.

Although only Pardee uses the phrase, the rhetoric members werevoicing is known historiographically as ‘conscription of wealth.’ Therole of ‘conscription of wealth’ rhetoric in the origins of the federalincome tax is repeated in every history of Canada that touches on thewar and Canada’s economy and government. All of these accountsoffer a variation on a standard narrative: a reluctant state introducedincome tax in response to calls for ‘conscription of wealth’ from farmersand workers, who argued that military conscription for overseas service,as presented under the Military Service Act, was unfair unless it wasaccompanied by some material sacrifice by the wealthy.6 This inter-pretation indirectly echoes Antonio Gramsci’s hegemony theory – anecho that has been made more explicit by Ian McKay in the first volumeof his history of the left in Canada.7 ‘Conscription of wealth’ was, asMcKay has argued, an attempt to oppose conscription and critiquethe unequal burden of war service that working-class Canadians wereexpected to offer, without appearing unpatriotic.8 McKay, however,takes no interest in the effects of the rhetoric beyond noting that theIncome War Tax was an ineffectual response. Richard Krever has notedin a little-read article that the ‘conscription of wealth’ debate in Parlia-ment reflected a delicate strategic dance between pro-conscription Lib-erals and Conservatives trying to create a coalition party.9 Undoubtedly

6 See, for example, Robert Craig Brown and Ramsay Cook, Canada 1896–1921:A Nation Transformed (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1974), 230; and CraigHeron and Myer Siemiatycki, ‘The Great War, the State, and Working-ClassCanada,’ in The Workers’ Revolt in Canada, 1917–1925, ed. Craig Heron (Toronto:University of Toronto Press, 1998), 21–2. Bob Russell’s ‘The Politics of Labour-Force Reproduction: Funding Canada’s Social Wage, 1917–1946,’ Studies inPolitical Economy 13 (Spring 1984): 43–74, is representative in underlining thethreat of labour unrest – rather than the appeal of labour’s rhetoric – in thepassage of the Income War Tax.

7 Gramscian theory holds that power is exercised by a hegemonic bloc, essentiallya coalition of powerful groups, and contested by a range of counter-hegemonicgroups, which potentially form a counter-hegemonic bloc. See AntonioGramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks, trans. Quintin Hoare and GeoffreyNowell Smith (New York: International Publishers, 1971).

8 He writes, ‘ ‘‘Conscription of wealth’’ . . . ingeniously worked to subvert theunifying ‘‘myth of the war’’ while seemingly agreeing with it.’ McKay, ReasoningOtherwise: Leftists and the People’s Enlightenment in Canada 1880–1920 (Toronto:Between the Lines, 2008), 134, 433–4.

9 Richard Krever, ‘The Origin of Federal Income Taxation in Canada,’ CanadianTaxation 3, no. 2 (Winter 1981): 170–88.

‘Conscription of Wealth’ and Political Modernism 385

‘conscription of wealth’ was a useful political instrument for forcingconcessions in war finance. But in focusing on the rhetoric’s rolein working out hegemony, scholars have sold it short. By payingmore direct attention to the rhetoric itself, this article will examinewhat parliamentarians and others who used ‘conscription of wealth’rhetoric in 1917 were in effect saying – not to deny the class struggleand elite accommodation that was being worked out in the process,but to enrich our historical understanding of it.

‘Conscription of wealth’ rhetoric was a useful instrument in theconstitution of hegemony because it was an expression of what Iterm political modernism. The rhetoric parliamentarians used in thedebates on the Income War Tax reflected a self-conscious urge tomodernize politics on the part of elites as well as opposition groups.Comments on the war and taxation during 1917 were coloured by asense of what David Harvey has called ‘a radical break with the past,’an awareness of radical novelty.10 Political modernism was concernedwith ‘unblocking energies and releasing flows’ by overturning estab-lished and ossified political practices through a process of creativedestruction and, as such, has gone unnoticed by historians of Canada,who have insistently underlined the sharpening left–right oppositionin this period.11 ‘Conscription of wealth’ reflected a shared aestheticthat ran across the more obvious political and economic divisions.The rhetoric’s vagueness and lack of coherence allowed it to proliferateand resonate with widely felt resentment of war profiteering, clarify-ing widespread disapproval of profit-making and high incomes moregenerally. The rhetoric of ‘conscription of wealth’ was powerful preciselybecause it was politically promiscuous, less a watchword than a spec-trum of meanings.

10 David Harvey, Paris, Capital of Modernity (London: Routledge, 2003), 1.11 Tim Armstrong, Modernism: A Cultural History (London: Polity, 2005), 82.

Creative destruction is a term coined by the economist Joseph Schumpeter, usedby Harvey to characterize the redesign of Paris by Georges-Eugene Haussmanin the period following the 1848 uprising. See Harvey, Paris, 2.

The historiography of Canadian working-class and left history forcefullyunderlines the increasing opposition between radical and hegemonic politicalprojects in this period. See especially Craig Heron, ed., The Workers’ Revolt inCanada, 1917–1925 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1998); and IanMcKay, Reasoning Otherwise: Leftists and the People’s Enlightenment in Canada1880–1920 (Toronto: Between the Lines, 2008). To say that there was a sharedaesthetic of political modernism is not intended to be a direct challenge to thatpicture, but simply to say that violently opposed political projects can sharesome formal similarities.

386 The Canadian Historical Review

This spectrum of meanings can be traced clearly in the use of ‘con-scription of wealth’ rhetoric by a range of speakers of differing politicalpositions, from the speeches and writings of Liberals and Conserva-tives to the Industrial Banner, the organ of the moderate labour organi-zation The Trades and Labour Council, in the period leading up tothe parliamentary debate on the Income War Tax. These expressionsclearly indicate that a more powerful income tax (one that taxed highincomes at higher rates) that proponents described as radical and pro-gressive, held political appeal across deepening political divides. At thesame time, the parliamentary record makes it clear that rhetoric thatappeared to undermine the economic and political orthodoxies of thewar effort, as did ‘conscription of wealth,’ was a matter of concern.The risks in voicing ‘conscription of wealth’ rhetoric were justified byits obvious political value in appealing to critics of conscription andwar finance and its more subtle expression of a modernist desire fora ‘radical break with the past.’ All of these rhetorical gestures madesense, of course, only in a political-economic context in which thecost of the war, financially and otherwise, was steep and regressive,falling more sharply on the poor than the rich.

‘a flea bite’: thomas white, the income war tax, and the

political economy of war

The enormous and unequal cost of the war in terms of displacement,debt, and death gave rise to a rapidly polarizing political culture andone of the most controversial parliamentary session in the history ofthe dominion. The Military Service Act, which saw men conscriptedfor military service overseas for the first time in Canada’s history, andwhich was debated at precisely the same time as the Income War Tax,was at the centre of this political controversy. In order to pass con-scription, Robert Borden’s government took unprecedented measures:it negotiated a coalition with pro-conscription Liberals, called theUnion government; it enfranchised women who were either in thearmed forces or had relatives serving, and disenfranchised recentimmigrants. The Income War Tax, similarly, was the first dominionincome tax, and, along with the Business War Profits Tax of 1916,represented the overturning of a long tradition of resistance to directtaxation by the federal government. It was a ‘break with the past’that, like the Union government and the enfranchisement of women,was a political gesture by the government to enlist support for con-scription and had little to do with paying for the war.

‘Conscription of Wealth’ and Political Modernism 387

The Income War Tax was introduced by Thomas White, a ministerof finance who had entered politics at the top, following the 1911 elec-tion. The dominion tariff, which was the major source of dominionrevenue and the primary instrument in the protectionist National Policy,was a central issue in that election. The Liberals under the leadershipof Wilfrid Laurier had negotiated an agreement with the United Statesfor partial reciprocity or free trade. The defection of eighteen promi-nent Liberal-identified businessmen to the anti-reciprocity cause hadbeen a key contributing factor in the Liberals’ defeat. Borden, the Con-servative party leader, was a bitter opponent of party politics and wel-comed the defectors as a symbol of his commitment to non-partisanelite rule.12 Although Borden was keen to include the ‘Toronto 18’ inhis government, only one, White, the vice-president of the NationalTrust Company, agreed to take a safe seat and a seat at the Cabinettable, as minister of finance, after the election.

White encountered serious problems shortly after becoming financeminister. The long economic boom that had been identified with Laurierand the delayed success of the National Policy in the 1890s came to anend in 1913, with the result that Canada’s credit dried up and its revenuefrom trade tariffs fell just as railways and other major public projectsturned desperately to the dominion government for financial support.White spent most of year before the war anxiously assessing the extentof the damage to the country’s financial reputation while endeavour-ing to appear unconcerned.13 The crisis illustrated the core problemwith the pre-war fiscal model, as R.T. Naylor has demonstrated: govern-ment operations were financed with loans that were paid with revenuefrom tariffs; in a depression, when trade slowed down, revenues fell,and credit dried up precisely when the state most needed it.14 A tradi-tional resistance to the imposition of direct taxation by the federal govern-ment (in part because provinces – and hence their creatures, themunicipalities – could only levy direct taxes) had forced the dominion

12 John English, The Decline of Politics: The Conservatives and the Party System 1901–20 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1979), 53–69.

13 Boxes 1–4 of Sir William Thomas White Papers, Library and Archives Canada(lac), consist of correspondence between White and various banking executivesand Canadian officials in London, sharing intelligence about Canada’s standingas a credit risk.

14 R.T. Naylor, ‘The Canadian State, the Accumulation of Capital, and the GreatWar,’ Journal of Canadian Studies 16, nos 3/4 (1981): 29.

388 The Canadian Historical Review

to rely on tariff revenues, leaving the Borden government with no alter-native but to wait for trade conditions to improve so revenues couldrevive.15

When the war began in the summer of 1914, White’s chief concernwas that interruptions in trade would cut even further into dominionrevenues.16 Although he was advised in Parliament and by corre-spondents that an income tax would be both possible and perhapsnecessary, White refused to adopt what he called a ‘minor’ measureand repeatedly emphasized the government’s intention to rely on thetariff for revenue.17 Within a year of the start of the war, in fact, muni-tions production had revitalized the Canadian economy, and employ-ment and trade conditions improved.18 But the war economy alsomade a regressive system of finance all the more regressive: war loans,a central financing instrument that provided income in the form ofinterest payments to banks and wealthy individuals, and that ultimatelyhad to be paid in revenue raised through the tariff, were essentially

15 W. Irwin Gillespie devotes considerable space to the many objections of dominionfinance ministers – from Richard Cartwright in the 1870s to White in the 1910s –to direct taxation. A representative quotation is George Foster’s remark, ‘I wouldlike to see the man who could be elected in any constituency on a policy ofdirect taxation.’ Tax, Borrow and Spend: Financing Federal Spending in Canada,1867–1990 (Ottawa: Carleton University Press, 1991), 56. H.V. Nelles has alsonoted that the peculiarities of Ontario’s resource policies can be explainedlargely by the province’s fear of ‘the ‘‘bugbear’’ of direct taxation,’ in The Politicsof Development: Forestry, Mines, and Hydro-Electric Power in Ontario, 1849–1941(Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1974), 46.

16 ‘On account . . . of the serious interruption of ocean commerce which is boundto ensue by reason of the hostilities I apprehend that our imports, andconsequently our revenues, may be more seriously curtailed and reduced andit would appear to me that we may face a situation in which the [previous]estimate of revenue will not be reached.’ White to Robert Borden, 3 Aug. 1914,box 3, Sir William Thomas White Papers, lac.

17 During the debate on the Income War Tax, Carvell cited his own suggestion inAugust 1914 that income tax should be introduced to pay for the war. House ofCommons Debates (25 July 1917), pp. 3769–70. Frederick William-Taylor, chair-man of the Bank of Montreal, then Canada’s largest bank and a key ally of thefederal treasury, and B. Edmund Walker, chairman of the Canadian Bank ofCommerce, wrote to Thomas White on 10 August 1914 to say that incometaxation was an option that, however unpopular, would be accepted. Box 3, SirWilliam Thomas White papers, lac. White’s description of income tax as a‘minor’ tax is highlighted in J. Harvey Perry, Taxes, Tariffs, and Subsidies(Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1955), 1:151.

18 Myer Siemiatycki, ‘Munitions and Labour Militancy: The 1916 HamiltonMachinists’ Strike,’ Labour / Le travail 3 (1978): 132.

‘Conscription of Wealth’ and Political Modernism 389

an income transfer from the poor to the rich.19 Added to this was theimpact of the boom on the cost of living, which increased dramaticallyin the middle of the war, causing further hardship to low-incomepeople who were already suffering from unfair taxation. That wealthyCanadians were actively encouraged to profit from the war by investingin war bonds muddied the distinction between the anti-social warprofiteer and patriotic investor that the government was keen onemphasizing, and underlined the deep inequity of the government’sapproach to war finance.

By reviving industrial production and increasing the cost of living,the war boom strengthened and revitalized organized labour. Theeconomic crisis of 1913–15 had reversed many of the gains the labourmovement had made during the Laurier boom. Massive unemploy-ment gutted unions; labour struggled to maintain basic rights with aseverely weakened bargaining position and became conciliatory. Theadvent of war and munitions contracts, Myer Siemiatycki argues,‘revived sagging trade union fortunes by turning the flooded labourmarket of 1914 into a dire manpower shortage by 1916.’20 Organizedlabour was a rising power, particularly in Ontario and Quebec, whereworkers threatened strikes that would have seriously underminedimperial war production.21 The introduction of national registration,which implicitly subjected industrial labour to the same power ofcompulsion as military service, created further resentment amongworkers, and the introduction of conscription, in the form of the MilitaryService Act, further inflamed class resentment toward a governmentthat compelled military service while it invited the rich to contributevoluntarily to finance the war – for a profit. Calls for the ‘conscriptionof wealth,’ as articulated by labour, drew on a moral opposition to thefurther enrichment of wealthy Canadians, especially as viewed againstthe conscription of other Canadians. The introduction of the IncomeWar Tax in the summer of 1917, which constituted a reversal of thegovernment’s previous position, was a response to these criticisms. Itwas not the expression of a changed attitude by White on the value ofincome taxation. It was a political solution to a political problem andwas greeted as such by the government’s critics.

19 W.A. Mackintosh notes that ‘issue after issue of tax exempt bonds put a pre-mium on large incomes to be paid out of the taxes of the ordinary consumer.’‘Revolution in Winnipeg, 1919,’ Labour / Le travail 60 (Fall 2007): 174.

20 Siemiatycki, ‘Munitions and Labour Militancy,’ 131–2.21 Ibid., 133.

390 The Canadian Historical Review

‘a fair arrangement of sacrifice’: wealth, labour,

and conscription

The rhetoric of ‘conscription of wealth’ developed out of the politicaleconomy of the war and served as a sharp indictment of the Conserva-tive government’s management of the war. It rested on a concept offairness that implied an equivalence between conscription and taxation.‘Conscription of wealth’ rhetoric was in fact quite complex and vague,containing a number of distinct arguments. On the one hand, wealthwas paired with manpower (or labour) in that both were resourcescomparable to natural resources and professional expertise and shouldin all fairness be made available to the state in order to prosecute thewar efficiently, usually via some specific mechanism such as incometaxation. On the other hand, conscription of wealth was presented asa kind of punishment for the rich – as illustrated by Forsyth’s insis-tence that taxation should ‘hurt’ – who benefit from the war throughwar bonds or actual profiteering, and who should be made less rich.Whether arising out of a technocratic idea of service to the state or abitter class resentment at the inequities of wartime economic condi-tions, or both, ‘conscription of wealth’ rhetoric found expression inthe statements of a wide range of speakers in the year leading up tothe Income War Tax debates.

At the centre of the class critique of conscription and war financewas the insistence that conscription, in defiance of its official univer-sality, meant conscription of the working class. This point was illus-trated forcefully in the Industrial Banner in an article citing a study bythe Canadian Manufacturers Association, which pointed out that anoverwhelming majority of those already enlisted were workers: ‘Outof 268,111 enlistments up to 15 February 1916, 170,369 are to becredited to ‘‘manual labour,’’ and 48,777 to ‘‘clerks.’’ ’ ‘In other words,’the editorial concluded, ‘mechanics, labourers and clerks have furnishedmore than eighty per cent, or four fifths, of all Canadian enlistments.’22

The numbers were not intended to suggest that professionals andmanagers, who made up the other 48,995, were less patriotic orbrave, but to remind readers that there were far more poor peoplethan rich, especially among those young enough to be conscripted.Conscription was therefore primarily conscription of the non-rich.23

22 Industrial Banner, 13 June 1916, 2.23 Under the Military Service Act, Class 1 recruits, who were first priority and, as

it turned out, the only ones to be actually conscripted, had to be unmarried,without children, and between the ages of twenty and thirty-five. Canada, TheMilitary Service Act: Its Meaning and Effects (Ottawa: King’s Printer, 1917), 1.

‘Conscription of Wealth’ and Political Modernism 391

Another story in the Banner on 15 September 1916 stated forcefully,‘The principle of conscription is one thing – the practice is quiteanother. In principle, it is an instrument of national defence; in prac-tice, it is made an instrument of working-class subjugation.’24 On 20October 1916, the headline ‘The Government Has Promised ThereShall Be No Conscription’ was paired with the subtitle ‘InsistentDemand for Conscription of Wealth.’ The articles reported that mem-bers of the Trades and Labour Congress Dominion Executive weremeeting with Borden, and quoted Simpson as saying, ‘If a man iscomputed to be worth $100,000 a good portion of that wealth shouldbe conscripted if it is found necessary to force conscription on men.’25

Conscription of wealth could therefore be an argument against con-scription (on the basis that men were already doing enough for thewar by enlisting), but it drew on a class understanding of war service,valorizing the contributions that workers made to the war short ofbeing forced to fight.

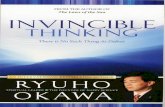

The idea of conscription of wealth was so effective and powerful, asIan McKay has noted, because it attached a critique of wealth to thepatriotic culture of the war.26 Indeed, by representing conscription ofwealth and conscription of manpower as two halves of an inseparablewhole, labour intellectuals were able to portray free enterprise asunpatriotic, and the government that nurtured its continued successas negligent in its execution of the war effort. The originality of thisrhetorical gesture is illustrated in a 22 June 1917 editorial in the Indus-trial Banner, which aimed at reframing the range of possible positionson conscription. ‘Individuals may honestly and conscientiously differon the question of conscription,’ as ‘some honestly advocate it andsome honestly oppose it, but neither Borden nor Laurier are to beplaced in that class.’27 The Banner insisted that it was inconsistentand dishonest to support conscription of men and not conscription ofwealth. An even more forceful equating of the conscription of wealthand men appeared on the front page of the Banner on 6 July 1917: animage of a conscription registration form for men side-by-side withone for conscription of wealth (figure 2). The image encapsulates therhetorical claim the Banner had been making for more then sixmonths: that men and wealth should equally be conscripted and thatto conscript one it was fair and necessary to do the other.

24 Industrial Banner, 15 Sept. 1916, 1.25 Industrial Banner, 20 Oct. 1916, 1.26 Ian McKay, Reasoning Otherwise, 434.27 Industrial Banner, 22 June 1917, 4.

392 The Canadian Historical Review

figure 2 A graphic from the cover of the Industrial Banner, 6 July 1917.

Source: 6 July 1917, 1 amicus 8550541, Industrial Banner, Library and

Archives Canada.

‘Conscription of Wealth’ and Political Modernism 393

A slightly different view of the relationship between conscriptionand taxation was taken up by Stephen Leacock, a noted Conservative,in his pamphlet National Organization for War, part of which CharlesMurphy cited in the debate on the Income War Tax. In typically immod-erate style, Leacock bemoaned the wastefulness, in the context of war,of selfish activity and insisted that all resources should be made avail-able for the war effort. He wrote, ‘If a war were conducted with the fullstrength of the nation, it would mean that every part of the fightingpower, the labour, and the resources of the country were being usedtoward a single end. Each man would either be fighting or engagedin providing materials of war, food, clothes and transport for thosethat were fighting, with such extra food and such few clothes as wereneeded for themselves while engaged in the task.’28

For Leacock, the efficient use of resources for the prosecution of thewar should be the singular priority of political economy. ‘This is thefashion in which the energies of a nation would be directed,’ he notedwith evident approval, ‘if some omniscient despot directed them andcontrolled the life and activity of every man.’29 The implication thatindividual freedom and property rights are, in a wartime context,anti-social, comes to the surface when Leacock addresses taxes specifi-cally. He estimates that consumers are paying 10 per cent of theirincome in war taxes, noting that this ‘means that nine-tenths of theman’s work is directed to his own use and only one-tenth for thewar.’30 War finance is depicted by Leacock as unscrupulously capitalisticand profit-seeking. Taxation is devised with ‘one eye on the supposedbenefits to industry,’ and the ‘so-called patriotic loan is so issued thatthe hungriest money-lender in New York is glad to clamber for a shareof it.’31 This enthusiasm for a system of public finance that looks beyondthe profit motive suggests that McKay’s identification of Leacock as aliberal is not entirely accurate.32

A more moderate expression of political elites calling for ‘conscrip-tion of wealth’ in the form of income taxation is provided by NewtonRowell, the Ontario Liberal leader who would run as a Unionist candi-date in the 1917 dominion election and play a central role in Borden’ssecond government. In a speech on 26 July 1917, and later reprintedin a pamphlet entitled Conscription of Wealth, Rowell said, ‘Men at thefront feel and feel keenly that while they are giving their all for Canada

28 Leacock, National Organization for War (Ottawa: King’s Printer, 1917), 3.29 Ibid., 3.30 Ibid., 4.31 Ibid., 9, 3.32 McKay, Reasoning Otherwise, 17.

394 The Canadian Historical Review

and for liberty, men at home are making huge profits out of the war.In justice to the men at the front as well as to the cause for which theyare fighting, we must require wealth to bear its share of the burden.Men who are profiting by the war must make a full contribution tothe cost of the war, and in addition, a radical, progressive income taxmeasure is urgently required.’33 Rowell here links a sense of justiceand fairness in war sacrifice and connects the large profits arisingout of the war to the need for an income tax – which he describes as‘radical’ (like his federal colleague Graham in the parliamentarydebates cited above) and ‘progressive.’ While progressive is a technicalterm in taxation, referring to the taxation of higher levels of incomeat higher rates, radical has no equivalent technical meaning. In anotherspeech on 2 August 1917, and reprinted in the same pamphlet, Rowellbrought up the issue again, this time specifically commenting on theIncome War Tax, which was in second reading at the time, criticizingits weakness by noting, ‘A progressive income tax is a step in the rightdirection, but we need a war measure not a peace measure like thepresent Bill.’34 Rowell again emphasizes the issue of equality of sacri-fice, but frames it in explicitly economic terms, saying, ‘The wholecapital of the working man is in his life and his capacity for work,’and arguing, ‘If he is placing that at the service of his country, thecontribution of a man of large income, who only gives the surplusover reasonable living expenses, is but dust in the balance comparedwith the contribution of the man who offers his life.’35 Rowell’s insis-tence on what he calls a ‘radical’ income tax, and his rejection of theIncome War Tax as a peace measure, both reflect a deep sense ofinjustice at the wartime economic conditions and a modernist interestin a ‘break with the past.’

‘he must be guarded in his language’: parliament and

the power of rhetoric

The ‘conscription of wealth’ rhetoric had been widely disseminated bythe time the Income War Tax was introduced in the summer of 1917.Parliamentarians using intemperate language calling for ‘more taxa-tion’ and ‘less satisfaction’ were at the end of a long rhetorical arc.Similar rhetoric in response to the weakness of a self-styled war taxon income would have been anticipated, given that ‘conscription of

33 Rowell, Conscription of Wealth (1917), 4.34 Ibid., 9.35 Ibid.

‘Conscription of Wealth’ and Political Modernism 395

wealth’ and labour’s political threats were a crucial inspiration forthe introduction of the tax. In the debate on the Income War Tax,however, Sir Thomas White did not respond to the onslaught of criti-cisms unleashed by the Liberals, a reflection of the convention that, inbudget debates, ‘members of the Opposition conduct almost the entiredebate.’36 The government’s silence presents us with a provocationwithout effect and prevents us from assessing how much of a threat toParliament’s functioning it was felt to be. However, two other incidentsin Parliament in the summer of 1917 illustrate the anxieties associatedwith intemperate speech related to the government’s handling of thewar.

The first of these incidents directly addresses the anxieties associatedwith the rhetoric of ‘conscription of wealth.’ It began on 22 June,when George Graham rose to say that he supported the introductionof an income tax, but that what he really meant was the impositionof a tax on high incomes. ‘I would not have an income tax for theman with the ordinary income because he has difficulty enough nowin living, but there are in Canada a great number of men who receivea great deal more money than they earn, and a portion at least of theirexcess income ought to go hand in hand with the labour and thesoldiery of Canada for the prosecution of this war.’37 He followed thisup with a resolution, which he presented for the House’s consideration:‘That in the opinion of this House it is desirable that steps should betaken forthwith by the Government to provide that accumulated wealthshould contribute immediately and effectively to the cost of the war, andthat all agricultural, industrial, transportation and natural resources ofCanada should be organized forthwith so as to ensure the greatestpossible assistance to the Empire in the war and to reduce the costof living to the Canadian people.’38 Graham made a point of drawingthe House’s attention to the fact that unlike ‘some people [who] havespoken of conscription of wealth, . . . I have not used that term.’39

Despite Graham’s evident circumspection and explicit distancing ofhis resolution from ‘conscription of wealth,’ Thomas White rose a fewweeks later, on 10 July, to clarify the risks of inflammatory speech. Inan official ‘Statement of the Finance Minister,’ White said, ‘It has been

36 ‘Generally the members of the Opposition conduct almost the entire debate andto an observer unfamiliar with this fact it would appear from its tenor that thebudget had been pretty much a dismal failure.’ J. Harvey Perry, Taxation inCanada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1951), 308.

37 Canada, House of Common Debates (22 June 1917), p. 2576 (George Graham).38 Ibid.39 Ibid.

396 The Canadian Historical Review

officially drawn to the attention of the Government that the use of theexpression ‘‘conscription of wealth’’ in the debates in Parliament andby public and other bodies outside of Parliament and by the press inits news reports has caused a certain uneasiness among those whosesavings constitute a vital factor in the business and industrial life ofthe Dominion and are so essential to the credit and prosperity uponwhich our efforts in the continued prosecution of the war must largelydepend.’ A number of things were at work in this statement. First,White was reminding the Commons and the public of the importanceof private credit for the dominion, which was the basis of federalfinance and, crucially, of the war effort. An ‘uneasiness’ among holdersof capital was a potentially serious problem. White therefore assertedthat ‘there need exist no apprehension on the part of the public thatany action of a detrimental character will at any time be taken withrespect to the savings of the Canadian public,’ clarifying that the gov-ernment might introduce ‘income taxation upon those whose incomesare such as to make it just and equitable that they should contribute ashare of the war expenditure of the Dominion.’40 Second, White wasdistinguishing between taxing accumulated wealth (or savings), whichwas not under consideration, and taxing income, which was. Finally,he was issuing a condemnation and a caution to parliamentariansto avoid frightening capital-holders with intemperate and imprecisespeeches.

Understandably concerned that the character of his comments hadbeen misconstrued, Graham immediately rose to defend his parliamen-tary record:

I did not use the term ‘conscription of wealth.’ The resolution which I

introduced was in these words:

That in the opinion of this House it is desirable that steps should be taken

forthwith by the Government to provide that accumulated wealth should

contribute immediately and effectively to the cost of the war.

The observations that I made were, I think, perfectly in harmony with the

wording of this resolution and with the remarks just made by the Minister of

Finance.41

White made no reply, but the prime minister stood and said, clearlyenough for the parliamentary reporter to hear and record, ‘Hear, hear.’42

40 Canada, House of Commons Debates, (10 July 1917), p. 3187 (Thomas White).41 Ibid.42 Ibid.

‘Conscription of Wealth’ and Political Modernism 397

Thus ended a particularly self-conscious display of cross-partisan concernfor the risks of parliamentary rhetoric.

A few weeks later, on 6 September, a less collegial dispute aroseabout the effects of rhetoric, this time on the subject of conscription,and this time in the Senate. P.A. Choquette, a Liberal appointee, roseto speak against conscription, which had just been passed in the formof the Military Service Act. Following a pre-emptive warning thatChoquette not speak against the war, the Senate listened anxiously asChoquette tried to avoid offending his audience and yet make hispoint. When he said, ‘These are some reasons why this war muststop and why many men are asking the Government not to put intoforce now this law which will send their sons –,’ the Speaker, JosephBolduc, and the government leader, James Lougheed, interrupted himto berate him for his speech. He declared that Choquette’s ‘line ofargument is such as to create excitement in the country and oppositionto the law of the land.’ Lougheed was more direct and aggressive, tell-ing Choquette, ‘If you had given expression to these sentiments inEurope, there would have been a firing-squad called out.’43

A long, bitter, and chaotic debate ensued, during which Choquetteaccused the speaker of being a sell-out to the English, and membersrepeatedly called for order and told each other to ‘shut up.’ Thingscooled eventually, and Charles Gavan Power, another Liberal appointee,pointed out that the problem was how Choquette had spoken ratherthan what he had said. A senator, Power said, ‘must be guarded inhis language.’44 Further emphasizing the need for moderate use oflanguage, he continued, ‘Honourable gentlemen should try to keeptheir heads and not be carried away by the strong feelings of themoment. I quite understand, as the honourable gentleman fromGrandville [Choquette] has a rather aggressive way of addressing theHouse, that possibly some honourable gentlemen opposite felt, in fact,‘‘riled’’ about it. . . . But we must not let our angry passions rise.’45 Obvi-ously fiery rhetoric was seen as a potential problem by parliamen-tarians. It was risky and it was taken seriously.

The anxious insistence of White, Lougheed, and Power that parlia-mentarians be circumspect in their criticism of the government’sconduct of the war speaks to the concerns of the political elite, bothLiberal and Conservative, about the risks rhetoric along the lines of‘conscription of wealth’ might pose to political and economic support

43 Canada, Senate Debates (6 Sept. 1917), 844 (James Lougheed).44 Ibid. (Charles Gavan Power).45 Ibid., 849.

398 The Canadian Historical Review

for the war. This anxiety was evidence of a widening polarizationbetween a political elite committed to continuing and even increasingCanada’s involvement in the war and an array of opposition groupsincreasingly intransigent in opposing it – a polarization historianshave underlined repeatedly.46 The debates on the Income War Taxreflected this polarization, both in the sense that Liberal memberswere unrestrained in their criticism of it and in the sense that the taxitself was introduced to dull opposition to conscription, which was themost divisive element of the government’s war policy. Conscription ofwealth – the rhetoric that motivated this response – while arising outof the polarization of political positions on the war, also served as abridge between political positions; unlike other increasingly absoluteoppositions, it admitted a spectrum of differences. It did this becauseit operated in the context of a shared desire for a ‘radical break withthe past,’ a political modernism that ran across more obvious politicaldifferences.

‘a great schoolmaster’: war, tax, and political modernism

Rather than simply an expression of class fear or political opportunism,or a critique of the political economy of war sacrifice, the rhetoric ofthe debate on the Income War Tax can also be seen as a reflection ofwidely shared but contested project of political modernism. Conscrip-tion of wealth wove together competing strands of critique and wasvoiced by speakers from differing and opposed political positions.This suggests that in fact speakers were making a modernist argumentfor conscription of wealth. While Borden and White’s undevelopedproject of progressive reforms and the emergence of the coalitionUnion government after the election of 1917 were the political fruitsof the elite project of political modernism, the emergence of indepen-dent Labour parties and a wave of strikes after the war (including theone at Winnipeg in the spring of 1919) reflected a labour project ofmodernism. As with the ‘conscription of wealth’ rhetoric with whichit overlaps, however, the modernist project reflected some similaritiesbetween elite and labour politics. In particular, both saw the war, andthe general modern era in which it was unfolding, as a force that wasawakening people to new possibilities and, in particular, to a clearerawareness of the world.

46 See note 11.

‘Conscription of Wealth’ and Political Modernism 399

The idea that the time had come for independent political action bylabour was a near-constant theme in the Industrial Banner over theyear leading to the summer of 1917. While the efforts of the Tradesand Labour Congress Executive to influence Borden and other membersof the political elite were applauded and endorsed by the editors, thepaper exhibited a pronounced distaste for the old political parties.What the paper called the ‘strike at the ballot box’47 was partly anexpression of ultimate frustration with labour’s marginalization bythe ruling Conservatives in particular but was also an expression ofthe full flowering of the working class’s own political emancipationand intellectual independence.

An editorial on 16 July 1916 makes this point clearly, arguing thatthe creation of a party for workers is the logical expression of labour’spolitical education: ‘The ballot must supplement political organizationon the industrial field, and the lessons that labour has learned of latein the school of hard experience should itself be the incentive to spurit into action to organize a great political party of its own in orderto capture and control the law making power of the state, in order tolay the foundations for a real and enduring democracy in which thepeople should rule and justice finally triumph.’48 The same editorialridiculed workers who still defined themselves as Liberal or Conser-vative, arguing that ‘the man who carries a union card today andcan insult his intelligence in order to follow round in the rear of anold party bandwagon should be caged in some zoo as a curiosity forsensible people to gaze upon.’49

This insistence on independent political action as essence of politicalmodernism, and on old elite-led parties as relics of political ignorance,is reflected repeatedly in the Banner, but most clearly in an editorial onthe importance of independent political action that explicitly draws onthe modernist imagery of mandatory progress: ‘There is not an intelli-gent observer to-day but realizes that great changes, industrially andpolitically, are in the making; that things will not go on as they havedone as in the past; in the old worn-out run that resulted in worldwideexploitation and disaster. None know this better than the professionalpoliticians, who fully realize that the old parties are losing their holdon the people, that the old pleas have lost their efficacy, and thatancient traditions must be quickly relegated to the scrap heap.’50 An

47 Industrial Banner, 7 July 1916, 2.48 Ibid.49 Ibid.50 Industrial Banner, 15 Dec. 1916, 4.

400 The Canadian Historical Review

eloquent and forceful expression of the idea of a ‘break with the past,’the passage celebrates the growing independence and awareness ofworkers as an expression of a modern consciousness and evenacknowledges the forces in the old elite-dominated political partiesthat have pushed for a rejection of partisanship.

The threat of conscription also inspired threats of extra-parliamentaryforms of independent political action: general strikes. As Myer Siemia-tycki has argued, the idea of a general strike in Canada began in themunitions factories of Toronto and Hamilton in 1916.51 With the riseof the conscription issue, Trades and Labour Congress locals beganpassing resolutions for a general strike in the event of the introductionof conscription, and pushing the national executive to adopt a similarstance on a dominion-wide basis.52 Although these efforts were unsuc-cessful, tlc President James Watters reflected this link in his com-ments to the New York Times on 4 July 1917. Asked how labour wouldrespond to the Military Service Act, Watters said they would

demonstrate their loyalty and patriotism on the day man-power is conscripted

by seeing that the work of their brains and every ounce of their physical

energy is utilized for the support of the men at the front and in defense of the

nation, to provide ample remuneration and adequate pensions for the men in

khaki and a full measure of protection to the dependents of such men, and to

relieve the nation from the burden of debt, which the productive work of

labour alone can meet – even if a general strike is necessary to bring it

about.53

Here Watters uses the rhetoric of ‘conscription of wealth’ to make thegeneral strike – the ultimate expression of the power of workers inde-pendent of the state – into a patriotic gesture. Whether this exactmove would have resonated very far, whether or not it would havefound a sympathetic audience or not, it undoubtedly would haveregistered with the dominion Cabinet and may have influenced theintroduction of the Income War Tax.

The Income War Tax itself, in fact, was welcomed, even by membersof Parliament who were critical of its weakness, as a necessary instru-ment in modernizing politics. In this case, rather than severing old

51 ‘Thus the war-induced epidemic of general strikes, which one prominentunionist dubbed ‘‘Winnipegitis,’’ found its earliest germination in Toronto.’Siemiatycki, ‘Munitions and Labour Militancy,’ 141.

52 Canada, Labour Gazette (Ottawa: King’s Printer, 1917), 847–9.53 James Watters, qtd in New York Times, 4 July 1917, 4.

‘Conscription of Wealth’ and Political Modernism 401

political affiliations, modernity was cast as a clarifier, eliminating con-fusion and allowing taxpayers and citizens to make informed andintelligent political choices. Clarity and intelligibility were the necessaryconditions for a healthy political culture, and for justice in government.The links between income taxation, modernity, and clarity were notnew in the war context, but the introduction of the Income War Tax –justified by the special exigencies of the war, and inspired by theunique conditions of class conflict produced by the war – served asan invitation to make the connections explicit.

This appeal to modernity, and to the potential of income taxationin bringing directness, legibility, and clarity to Canadian politics, canbe seen in the contributions of F.B. Carvell – another Liberal mp

who became, after the 1917 election, a member of the Unionistgovernment – to the debate. When the bill to create the Income WarTax got to the Senate, senators broke with convention (under whichthe Upper House passes all money bills passed by the Commonswithout revisions) and amended it, allowing investigations into taxevasion to be held in camera, out of view of the general public. Whiteexpressed concern about the move, but was concerned primarily withavoiding a confrontation over the issue. On 15 September 1917, Carvellrose to denounce the Senate amendments and did so by linkingincome taxation with modernity and clarity. Income taxation, he said,‘produces a condition of affairs by which, after the war is over, we candiscuss questions of trade, commerce, and tariff much more intelli-gently than we have been able to discuss them.’ Carvell’s interestin more intelligent discussions of the tariff may have been an obliquereference to the Liberals’ defeat in 1911 on the question of partial reci-procity. Carvell also noted that ‘the financial condition of Canadahas so changed during the last three years [since the war started] asto revolutionize our whole method of taxation.’ He continued, ‘Wehave to get down to direct taxation, and to adopt a system so efficient,straight and above board that every man will know whether or not hisneighbour is paying his fair share of taxation.’54 Here Carvell linkedmodernity and direct taxation in the need for political clarity, for visi-bility and transparency. Carvell’s enthusiasm for income taxation, andhis linking it with modernity, echoed a comment Michael Clark madeon 17 August: ‘The war . . . has been a great fiscal schoolmaster, as wellas a great schoolmaster along other lines.’ Clark also congratulatedWhite that ‘he has learned from the course of the war the necessity

54 Canada, House of Commons Debates (15 Sept. 1917), p. 5885 (F.B. Carvell).

402 The Canadian Historical Review

of putting on some direct taxation.’55 Like the necessity of indepen-dent political action for the Banner, the necessity of direct taxationwas represented by these Liberal members as the lesson of the war,the awakening that the war forces upon a sleep-walking polity.

Ironically, though, the rhetoric of conscription of wealth owed muchof its appeal, and its reproducibility, to its ambiguity. It enfolded differ-ent conceptions of the relationship between taxation and conscription,and speakers often made little attempt to clarify what they meant by it.No one who used the phrase could be sure what listeners understoodit to mean; it could suggest very different things to different audiencessimultaneously. Although this undermined its link with clarification,it was to some extent inherent in its reproduction. Whether this pro-ductive ambiguity was a problem was a matter of debate. The OttawaJournal, a Conservative paper, for example, ran an editorial on 24August 1917 that decried the proliferation of the ‘catch phrase ‘‘theconscription of wealth,’’ ’ describing it as ‘the cheap clap-trap oneexpects only from the loose minded.’ The Liberal Citizen replied thenext day with an editorial noting, ‘Nothing quite so grates upon theadministration press as the term ‘‘conscription of wealth.’’ ’56 It waseasy to criticize the vagueness of ‘conscription of wealth,’ but equallyeasy to accuse anyone who did so of having ulterior motives.

A similar exchange occurred in the Industrial Banner. The paperpublished a letter by Harriet D. Prenter on 8 June 1917, which askedwhether the Toronto District Labour Council should ‘hold a few meet-ings at once in the Labor Temple for the purpose of explaining whatis actually meant by ‘‘conscription of wealth’’?’ The letter noted, ‘Itis only as we understand, that we think and act fairly, and to mostpeople conscription of wealth is merely a phrase, whereas a littleexplanation will prove to any reasonable mind that it is quite a way tonationalize the material resources of our country as it is to nationalizethe lives of our men, and that in no other way can there be any real‘‘equality of sacrifice’’ between the rich man and the workers.’57 ForPrenter, clearly, ‘conscription of wealth’ was more than a phrase: itarticulated a clear basis for determining whether the war effort wasbeing carried fairly by everyone. But it was the phrase’s ambiguity –its status as just a phrase – that made it ubiquitous and thereforepowerful.

55 Canada, House of Commons Debates (17 Aug. 1917), p. 4640 (Michael Clark).56 The Journal editorial was reprinted in the Citizen (25 Aug. 1917), 12.57 Industrial Banner, 8 June 1917, 4.

‘Conscription of Wealth’ and Political Modernism 403

The letter elicited no reply, but an editorial on 13 July, after pointingout that the phrase ‘wealth conscription’ was becoming increasinglywidespread and that ‘even old-line political organizations are passingresolutions that are getting dangerously close to the line,’ dismissedthe charge of ambiguity, revelling instead in the idea’s growing appeal.‘It’s coming all right,’ the editorial concluded confidently, ‘and when itgets here everybody will know just exactly what the term means.’58

Just as easy as it was to point accusing fingers at anyone who com-plained of the phrase’s vagueness, it was also easy to resort to teleolog-ical bluster when someone suggested some elucidation.

The rhetoric of conscription of wealth, which conflated a number ofdifferent critiques of war-generated wealth and called for a ‘break withthe past’ as the necessary response to the inequities of war financeand the muddied, corrupted, and ossified political culture that sus-tained it, can be read as an expression of a project to modernize politicsthat crossed class lines. The conscription of wealth, the threat ofpolitical action outside Parliament, and the advent of dominion incometaxation were linked to a clarification of politics, an awakening fromthoughtless tradition that reinforced inequalities and blocked citizensand taxpayers from seeing politics clearly. Liberal politicians, Conser-vative pamphleteers, and labour journalists agreed on the need tomodernize politics and saw fiscal reform, and the immense potentialof income taxation in particular, as a necessary instrument in thatwork.

conclusion

The debates on the Income War Tax in the summer of 1917 are aremarkable event in Canadian political history. They serve as an illu-minating case study of how dissent is handled by the political elite,and of the important role Parliament played as an institution manag-ing and channelling dissent. The Income War Tax itself was notradical, but the debates its weakness inspired opened Parliament upto a sharp critique of the operation of wartime finance that had beenin wide circulation among the elite as well as labour. The dominion’shalf-hearted turn to income taxation, under pressure from a widerange of critics, was greeted by some reformers as a salutary ‘breakwith the past,’ that would clarify the muddled world of Canadianpolitics. Over the two decades that followed its introduction, as it

58 Industrial Banner, 13 July 1917, 4.

404 The Canadian Historical Review

wound its way from controversy to controversy, the Income War Taxwould repeatedly be characterized as both a weak and dismal creatureand a powerful force for change.

That parliamentarians in 1917 used the rhetoric of ‘conscription ofwealth’ to dull dissent and assert the centrality of their role as shapersof rhetoric – and in the process articulated a radically modernist projectof political reform – suggests that some basic assumptions about thepolitical history of the period merit re-examination. First, historianshave treated Parliament as a secure stronghold of liberal-democraticpolitical legitimacy and so have not asked how parliamentarians activelyworked to secure the institution’s place in social life, or read the histor-ical record as an expression of that project. In the context of the war,with a radicalizing working class and an unpopular agenda of forcedsacrifice, the authority of the political elite could not be taken forgranted. Second, that the occasion for this display of rhetorical excite-ment was the passage of an income tax also suggests that taxationitself was inherently politically potent in this period. The image ofincome taxation as dull and technical, as an impersonal and abstractburden no one wants to talk about, clearly arises from a later time.The rhetoric of ‘conscription of wealth’ suggests that progressive incometaxation was perceived as something that was inherently ‘radical’ in thesense that it was new, that its arrival suggested – however meekly – theadvent of a new political culture.

Historiographically, the debates over the Income War Tax underlinethe extent to which the rhetoric of ‘conscription of wealth’ resonatedacross what would normally be understood as different ideologicalpositions. Historians have repeatedly underscored the increasinglyantagonistic political culture of the later years of the war and havedrawn a sharp line between liberal or capitalist understandings of thewar and social service and those articulated by labour or leftist move-ments.59 Social and political conflict between these competing visionsof a just war or postwar society was rising in 1917, but criticisms ofwar finance were not expressed in terms of liberalism or socialism,however much these ideas may have underlain their assumptionsabout fairness and wealth. To a remarkable degree, ‘conscription ofwealth’ reflected, and was intended to reflect, a shared critique of theinequities of war finance and a shared insistence on reform, albeit onethat resisted easy definition. The rhetoric reflected, to some extent, ashared desire for efficient use of resources, for clarity of politicalthought, and for a ‘break with the past.’ This interpretation suggests

59 See note 11.

‘Conscription of Wealth’ and Political Modernism 405

a methodological caution against assuming that historical actors willalways speak as we expect them to, shouting at one another across anabsolute divide, and an invitation to be more descriptive (and less pre-scriptive) in reading political identities off the speeches and writingsof people in the past. As scholars of political ideas, we should bealert to the idiosyncratic statements of historical subjects and learn toappreciate them.

Does an awareness of the place of ‘conscription of wealth’ in theparliamentary debates on the Income War Tax have any political valuein the present? If we study the history of taxation to redress theinequalities that Canada’s tax system, with its liberal commitment tothe inviolability of wealth, continues to support, can we draw anythingmeaningful from the fact that federal income taxation originated ina widely shared desire to ‘hurt’ the rich? It would certainly be naiveto suggest that parliamentarians who used rhetoric in criticizing theIncome War Tax seriously intended to use the federal taxing power toeffect a real equalization of income in 1917, and essentialist to implyfurther that this radical project at the origins of income taxationhaunts us still. But it would be equally erroneous to insist that theinitial shock of encountering an excited insistence on a powerful redis-tribution of sacrifice in the parliamentary record, which was both theinspiration and the rhetorical hook for this paper, is politically inert.Certainly, the excitement it produces is a function of its ahistoricismand, with the requisite grounding in its historical context, it losessome of its peculiarity and force. It becomes understandable andmeaningful, almost expected. In its initial encounter it presents uswith an unfamiliar sensation, what Quentin Skinner calls ‘a broadersense of possibility,’ a sense that what is expected is not always whathappens.60 Even though that excitement is fleeting, it is a valuableencounter. Excitement, as the speaker cautioned Senator Choquette,is political.

60 Quentin Skinner, Visions of Politics, volume 1: Regarding Method (Cambridge,uk: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 6. What I am proposing is similarto Walter Benjamin’s idea of the dialectical image, as explained by SusanBuck-Morss in Dialectics of Seeing: Walter Benjamin and the Arcades Project(Cambridge, ma: mit Press, 1989), which draws on the ‘shock of recognition tojolt the dreaming collective into a political ‘‘awakening.’’ The presentation of thehistorical object within a charged force field of past present, which producespolitical electricity in a ‘‘lightning flash,’’ is the dialectical image’ (219).

406 The Canadian Historical Review

david tough is a PhD student at Carleton University in the Department of

History and the Institute of Political Economy. His dissertation, ‘The Terrific

Engine: The Rhetoric of Dominion Income Taxation and the Modern Political

Imaginary in Canada, 1911–1945,’ argues that fantasies about income taxation’s

capacities for equalizing wealth played a key role in modernizing political

language and popularizing the left–right spectrum in Canada.

david tough est candidat au doctorat au departement d’histoire et de

l’Institute of Political Economy de l’Universite Carleton. Sa these intitulee

« The Terrific Engine: The Rhetoric of Dominion Income Taxation and the

Modern Political Imaginary in Canada, 1911–1945 » affirme que les espoirs

concernant le potentiel de l’impot sur le revenu dans une perspective d’egali-

sation de la richesse ont joue un role cle dans la modernisation du discours

politique et la popularisation de l’axe gauche-droite au Canada.

‘Conscription of Wealth’ and Political Modernism 407