The Régie Monopoly and Tobacco Workers in Late Ottoman Istanbul

Transcript of The Régie Monopoly and Tobacco Workers in Late Ottoman Istanbul

I would like to thank Jean Quataert, Kent Schull, and David Gutman for their valuable comments and suggestions.

1. See Quataert, “Economic Climate of the ‘Young Turk Revolution.’ ”

2. See Kırpık, “Osmanlı Devleti’nde I.sçiler ve I

.sçi Hareketleri,” 256 – 63.

3. See ibid., 265 – 67, and Karakısla, “Osmanlı I.mparatorlugu’nda 1908

Grevleri,” 203.

4. See Haupt and Dumont, Osmanlı I.mparatorlugunda Sosyalist Hareketler,

and Hadar, “Jewish Tobacco Workers in Salonika.”

206 Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East Vol. 34, No. 1, 2014 • doi 10.1215/1089201x-2648668 • © 2014 by Duke University Press

The Régie Monopoly and Tobacco Workers in Late Ottoman Istanbul

Can Nacar

T he year 1908 marked a watershed for labor movements in the Ottoman Empire. In July of that year, the Young Turk Revolution overthrew the autocratic regime of Abdülhamid II (r. 1876 – 1909) and restored the constitution of 1876 under the banner of liberty, equality, fraternity, and justice.

The revolution, which took place against a background of mounting economic distress and social un-rest, spurred a wave of labor militancy.1 Between late July 1908 and the end of the year, some 119 strikes involving thousands of workers swept across the empire, often bringing industry and transportation to a standstill.2 Fearing that the strike wave might reach a point where they would be unable to control it, the leading cadres of the revolution quickly adopted legal measures aimed at curbing labor militancy. This move, as studies on Ottoman labor history demonstrate, proved effective in public service companies such as railways and tramways. While, for instance, railway workers played a notable role in the strike wave of 1908, the majority of them did not participate in any strike in the period between 1909 and 1914.3

However, the story of railway workers is not representative of all labor groups in the empire. Ot-toman labor historians, for instance, have documented the growth of a vibrant labor movement in the province of Salonica between 1909 and 1912.4 Yet, still relatively little is known about workers’ collective actions in other parts of the empire after the strike wave of 1908. This study sets out to offer some insight into this issue and thus focuses on one of the largest industrial enterprises in Istanbul, the Cibali tobacco factory. Examining strikes and unionization efforts at the turn of the century, it argues that in 1911, tobacco workers in the imperial capital were more organized and militant in their demands for better terms of employment than they had been in previous years, including 1908. In the period between the early 1890s and 1910, labor protests in the Cibali factory either did not go beyond the planning stage or lasted only a few days. In contrast to this pattern, in 1911, workers there launched what would be one of the longest strikes in late Ottoman history. This surge in labor militancy did not happen overnight. This article shows that the 1911 strike, in addition to other factors, owed a great deal to workers’ organizational efforts. These efforts fostered a sense of solidarity and togetherness among workers employed in different departments of the factory.

This study also questions whether tobacco workers’ collective actions had any impact outside of

5. See 1296 Senesi Martı I.btidasından Subatı Ni-

hayetine, 25, and “Tabakerzeugung, Bearbei-tung und Handel in der Europaischen Türkei,” 338.

6. Basbakanlık Osmanlı Arsivi (Prime Minis-try Ottoman Archive, hereafter BOA),Yıldız Esas Evrakı (Main Yıldız Documents, hereafter Y.EE) 11/17, report from the Régie Superinten-dent to the Imperial Palace (13 Cemaziyelev-vel 1307/5 January 1890). See also Quataert,

“Régie, Smugglers, and the Government,” 21, and Tanin, “Müsterekü’l- Menfaa Reji Sirketi,” 26 Kanunusani 1324/8 February 1909.

7. See Dogruel and Dogruel, Osmanlı’dan Günü-müze Tekel, 47 – 51.

8. See Quataert, “Age of Reforms,” 902.

9. BOA, Sura- yı Devlet (The Council of State, hereafter SD) 565/24 (15 Kanunusani 1294/27 January 1879); BOA, SD 568/19, list of tobacco

factories prepared by the accountant of the Department of Excise Taxes (25 Subat 1296/9 March 1881).

10. BOA, SD 568/19, list of tobacco factories pre-pared by the accountant of the Department of Excise Taxes (25 Subat 1296/9 March 1881); BOA, SD 568/19, petition written by a tobacco company owner in Izmir (28 Tesrinievvel 1296/9 November 1880).

207Can Nacar • Régie Monopoly and Tobacco Workers in Late Ottoman Istanbul

their workplaces. At the turn of the twentieth cen-tury, most of the strikes in the Cibali factory con-cerned three parties: the strikers themselves, the factory administrators, and Ottoman government officials. However, the 1911 strike turned out to be an important event also for many workers outside the Cibali factory and some left- wing politicians in the parliament. This article examines the contacts between the strikers and these “new” actors and highlights the growing sense of solidarity among them. Before moving to these issues, however, it provides general information about the Ottoman tobacco industry and the profile of the labor force in the Cibali factory.

The Ottoman Tobacco Industry and the Régie CompanyTobacco was one of the most lucrative crops in the Ottoman Empire in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In the 1880s, major ciga-rette producers in Egypt, Europe, and the United States began to increase the proportion of high quality tobacco from the Balkans and Anatolia in their cigarette blends. Therefore, in the three decades before World War I, Ottoman exports of tobacco leaf followed an upward curve. According to official statistics, tobacco shipments reached 8.9 million kilograms in 1880, 15.9 million kilograms in 1897, 20.6 million kilograms in 1903, and 38.4 million kilograms in 1911.5 Tobacco products were also quite popular among the populations of the Ottoman Empire. Government officials, commer-cial agents, and journalists estimated that annual tobacco sales within the empire ranged between 18 and 20 million kilograms at the turn of the century.6

Both local and foreign entrepreneurs in the empire sought to capture a greater share of rev-enues generated by tobacco sales. For this purpose, some of them attempted to create monopolies in

domestic markets. In March 1872, for instance, two Greek financiers named George Zarifi and Chris-taki Zografos obtained a monopoly to buy and sell tobacco in Istanbul for a period of five years. In return, they would pay the government four hun-dred thousand Ottoman lire annually. When, how-ever, Zarifi and Zografos reported a loss for the eight- month period between March and October 1872, a state- run enterprise called the Tobacco Monopoly Administration took over the monopoly and retained it until 1877.7 To supply the imperial capital with tobacco products, the Monopoly Ad-ministration built and operated a factory employ-ing some fourteen hundred workers.8

After the abolition of the monopoly in 1877, new factories financed by tobacco merchants and other entrepreneurs sprang up in Istanbul. Twenty- eight such factories existed in 1879, and that num-ber would reach over forty by 1881.9 Around the same time, many provincial towns in the empire also possessed a flourishing tobacco industry. In 1881, tobacco workers operated thirteen factories in Izmir, at least nine in Salonica, seven in Edirne, six in Erzurum, and five in Aleppo and Janina.10 The sources consulted discuss neither the output of these establishments nor the number of workers employed in them. It is quite possible that among them were both small unmechanized workshops and enterprises employing tens of workers and uti-lizing sophisticated machines. In any case, all the factories across the empire, except those in Leba-non and Crete, closed their doors permanently when the Ottoman government granted a new to-bacco monopoly to a foreign company, the Régie Company (a consortium of the Ottoman Bank, Crédit Anstalt, and Bleichröder bank groups), in 1883. The Régie, according to its agreement with the Ottoman state, had the exclusive right to buy, process, and sell all the tobacco grown in the em-pire with the exception of that to be exported.

11. See Quataert, “Régie, Smugglers, and the Government,” 13 – 14.

12. See Dogruel and Dogruel, Osmanlı’dan Günümüze Tekel, 80; “The Ottoman Tobacco Industry,” 733 – 34; and BOA, Dahiliye Nezareti I.dare Kısmı (The Ministry of Interior, Adminis-

trative Section, hereafter DH.I.D) 107/51, report

from the Régie Superintendent to the Ministry of Finance (25 Temmuz 1328/ 7 August 1912).

13. See Quataert, “Régie, Smugglers, and the Government,” 18; Ilıcak, “Jewish Socialism in Ottoman Salonica,” 121; and BOA, Dahiliye Ne-zareti Mektubi Kalemi (The Ministry of Interior, Chief Secretary, hereafter DH.MKT) 847/67, re-port from the Vice- Director of the Régie Com-pany to the Ministry of Interior (21 Nisan 1320 /4 May 1904).

14. See “The Ottoman Tobacco Industry,” 733.

15. See Spataris, Biz I.stanbullular Böyleyiz!

Fener’den Anılar, 55, 69.

16. BOA, Zabtiye Nezareti (The Ministry of Po-lice, hereafter ZB) 320/25, report from the Min-istry of Police to the Ministry of Interior (30 Kanunuevvel 1322/12 January 1907).

17. BOA, DH.MKT 912/53, list showing the names of the Régie workers who tried to orga-nize a strike in 1904.

18. “The Ottoman Tobacco Industry,” 733 – 34.

19. See Moore, “Some Phases of Industrial Life,” 193 – 94.

Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East • 34:1 • 2014208

The origins of the Régie Company went back to 1875 – 76, when the Ottoman government declared a debt payment moratorium. Subsequent negotiations for the repayment of Ottoman debts led to the formation of the Public Debt Adminis-tration in 1881. This new institution, which was a consortium of foreign creditors, was entitled to ad-minister certain tobacco taxes and establish a new tobacco monopoly in the empire. Two years later, in 1883, the Public Debt Administration ceded its right of monopoly to the Régie Company in return for annual payments of 750,000 Ottoman lire. Moreover, both the Public Debt Administra-tion and the Ottoman state would receive a share in the profits of the new monopoly.11 Shortly after the agreement was signed, the Régie began its op-erations and proceeded to establish new factories in major production and transportation centers of the empire. The company opened its largest fac-tory in the Cibali district of Istanbul in 1884. In the early 1890s, the factory employed about fifteen hundred workers. Within less than two decades, however, the number of its workers exceeded two thousand two hundred.12 The second largest Régie factory was located in the Black Sea port city of Samsun. In the period between 1888 and 1897, five hundred workers and twelve overseers earned their living in this factory. By the end of the nineteenth century, the company’s other major factories in Sa-lonica, Izmir, and Adana employed approximately one thousand workers in total.13

The Profile of the Labor Force and Working Conditions in the Cibali FactoryThe Cibali factory brought male and female, Mus-lim and non- Muslim workers together. In the early 1890s, women and girls accounted for two- thirds of its workforce.14 Many of the female workers, like their male counterparts, were Christians and Jews

living in nearby neighborhoods of the Golden Horn, such as Balat, Hasköy, and Fener. In his memoirs, for instance, a former Greek resident of Istanbul wrote that the Cibali factory employed young and pretty Jewish girls from Balat.15 A police report dating from February 1907 mentioned fe-male tobacco workers from Hasköy. According to the report, a boat carrying eight woman passen-gers between Hasköy and Cibali overturned. Fol-lowing the accident, some police and gendarme officers from the Cibali Police Station leaped into sea and saved the lives of the women, who were em-ployed in the Cibali factory.16 Likewise, when the factory administration listed the names of male and female workers who attempted to organize a strike in 1904, it appeared that eight out of twelve blacklisted workers lived in Balat, Hasköy, and Fener. These workers constituted a religiously het-erogeneous group comprising Jews and Orthodox Christians.17

Among the workers streaming into the Cibali factory were hundreds of children, both boys and girls. Children worked in almost every stage of pro-duction. In the tobacco cutting department, about eighty apprentice boys were feeding the cutting machines with tobacco leaves in the early 1890s. The packing department, on the other hand, em-ployed many young girls “celebrated for their dex-terity and rapid manipulation.”18 Similarly, a pho-tograph taken by Guillaume Berggren at the turn of the century depicts young girls rolling cigarettes in a spacious room in the factory (see fig. 1). The Régie continued to employ children until its disso-lution in 1925. According to a report prepared by an American research team in the early 1920s, the Cibali factory had 170 child workers with an aver-age age of twelve years.19

In discussing the profile of the labor force, it is also important to mention the presence of

20. BOA, DH.MKT 912/53, list showing the names of the Régie workers who tried to orga-nize a strike in 1904.

21. BOA, Dahiliye Nezareti Emniyet- i Umumiye Tahrirat Kalemi (The Ministry of Interior, Secre-tariat of General Security, hereafter DH.EUM.THR) 99/45, report from the Security General Directorate to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2 Mayıs 1327 /15 May 1911).

22. See “Ottoman Tobacco Industry,” 733 – 34, and “Osmanlı Tütünleri ve Reji I

.daresi,” 296.

209Can Nacar • Régie Monopoly and Tobacco Workers in Late Ottoman Istanbul

foreigners. The sources consulted do not provide precise figures for the number of non- Ottoman employees in the Cibali factory, though the Régie and Ottoman state documents occasionally men-tion European workers. Here are two examples. First, after the failed strike attempt in 1904, Régie officials blacklisted an Italian worker named Odi-sya Tebrizya.20 The other example comes from a police report dated seven years later. In 1911, police officers in Istanbul conducted an investigation into the nationality of a deceased person named Para-sinho. According to the police report, Parasinho was born in Greece, moved to the district of Fener in 1902, and lived there until his death in 1908. Be-tween 1902 and 1908, he earned a living as a fore-man in the Cibali factory.21

The employees of the Cibali factory, regard-less of age, religion, or nationality, worked in sex- segregated settings. The tobacco sorting and cutting departments, for instance, employed only male workers. Women, on the other hand, made up the majority of cigarette makers and packers. In the early 1890s, for instance, at least three- quarters of the cigarette rollers in the factory were female. Moreover, about twenty women workers fed cigarette- making machines with lower- quality tobaccos. In both the cigarette- making and pack-ing departments, the factory administration pro-vided separate rooms for male and female work-ers.22 Only a few men were allowed to work with women. The sources consulted offer clear hints of the power relations between these men and their

Figure 1. Female Cigarette Rollers in the Cibali Factory. Photograph by Guillaume Berggren, Kadir Has University Collection, Istanbul

23. For a discussion of gendered hierarchies in the Cibali Factory, see also Balsoy, “Gendering Ottoman Labor History.”

24. BOA, DH.MKT 2111/107, report from the Min-istry of Interior to the Ministry of Finance (17 Eylül 1314/29 September 1898).

25. Moore, “Some Phases of Industrial Life,” 193.

Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East • 34:1 • 2014210

female coworkers. For example, one of the pho-tographs taken by Guillaume Berggren depicts a male overseer watching over two female machine operators in the cigarette- making department (see fig. 2).23

Although they were toiling in separate rooms, male and female workers shared common grievances, such as unhealthy working conditions. After a visit to the factory in 1898, a sanitation in-spector reported that although an open space in the middle of the building enabled air to circulate, the poor ventilation systems in workrooms could not remove tobacco dust. To solve this problem, the report proposed the construction of new chim-neys.24 However, it seems that the proposal did not find a favorable response from the Régie. In the

early 1920s, visitors to the factory still mentioned the poor ventilation and the dust- laden atmo-sphere of the workrooms. Workers exposed to to-bacco dust were prone to eye and lung infections. “More than half of the children [in the Cibali factory],” wrote the aforementioned American re-search team, “are sub- normal physically, and there are many cases of bad eye disease.”25

The workers in the Cibali factory were often paid piecework wages. In a petition addressed to the Grand Vizierate in July 1902, for instance, twenty- six male cigarette rollers noted that the Régie Company paid them six piasters for every one thousand cigarettes. As average daily produc-tion per worker ranged between 1,150 and 1,540 cigarettes, the average wage of a male cigarette

Figure 2. Female Machine Operators in the Cibali Factory. Photograph by Guillaume Berggren, Kadir Has University Collection, Istanbul

26. BOA, Bab- ı Ali Evrak Odası (Sublime Porte Secretariat, hereafter BEO) 1890/14173, peti-tion from cigarette rollers in the Cibali factory to the Grand Vizierate (9 Temmuz 1318 /22 July 1902). See also “Ottoman Tobacco Industry,” 734.

27. BOA, Dahiliye Nezareti Emniyet- i Umumiye Müdüriyeti Kısm- ı Adli Kalemi (The Ministry of Interior, Security General Directorate, Secretar-iat of Judiciary, hereafter DH.EUM.KADL) 14/22, report from the Director of the Istanbul Police to the Security General Directorate (16 Subat 1326/1 March 1911).

28. See 1325 Sene- i Hicriyesine Mahsus Selanik Vilayet Salnamesi, 426.

29. BOA, DH.MKT 912/53, report from the Grand Vizierate to the Ministry of Interior (17 Mart 1322/30 March 1906).

30. BOA, SD 436/79, report from the Ministry of Finance to the Council of State (22 Temmuz 1324/4 August 1908).

31. BOA, Yıldız Sadaret Hususi Maruzat (Yıldız, Grand Vizierate, Documents on Issues of Par-ticular Concern, hereafter Y.A.HUS) 273/60 (15 Nisan 1309/27 April 1893).

32. BOA, DH.MKT 912/53, report from the Grand Vizierate to the Ministry of Interior (17 Mart 1322/30 March 1906); report from the Minis-try of Police to the Ministry of Interior (17 Mart

1322/30 March 1906); report from the Prefect of Istanbul to the Ministry of Interior (17 Mart 1322/30 March 1906).

33. BOA, I.rade Hususi (Sultanic Decrees on Is-

sues of Particular Concern, hereafter I..HUS)

1310.L.37 (9 Sevval 1310 /26 April 1893).

34. BOA., Y.A.HUS 273/60 (15 Nisan 1309/27 April 1893).

35. BOA, I..HUS 1324.S.1 (4 Safer 1324 /29 March

1906).

36. For an analysis of this ruling strategy of the sultan, see Özbek, Osmanlı I

.mparatorlugu’nda

Sosyal Devlet.

211Can Nacar • Régie Monopoly and Tobacco Workers in Late Ottoman Istanbul

roller did not exceed ten piasters per diem.26 The available evidence shows that female cigarette makers and packers were paid even lower wages. In 1911, little girls employed in the cigarette- making department toiled nine hours a day and earned 2.5 piasters.27 This amount represents only half of the lowest wage paid to tobacco workers in Kavala, the major tobacco processing center in the Ottoman Empire in the early twentieth century.28 The prob-lem of low wages was exacerbated by the failure of the factory administration to make payments on time. In the early twentieth century, as compensa-tion for unpaid wages, the Régie paid its workforce a certain sum of money annually on Easter.29 With regard to wage issues, it is also important to note that workers contributed a sizeable portion of their income to the Istanbul Municipality as income tax. In return for the payments, the municipal-ity granted them artisan licenses. In 1908, female workers who were fifteen years old and younger paid ten piasters in income tax, while those who were over fifteen years of age and earned fifteen piasters per diem paid twenty- five piasters.30

Labor Activism in the Cibali Factory, 1893 – 1910At the turn of the twentieth century, strikes and other forms of industrial dispute became common-place in the tobacco industry. Before the Constitu-tional Revolution in 1908, the Cibali factory had been the site of at least two strikes, one in 1893 and the other in 1906. These strikes were of short dura-tion, usually a few days, and focused primarily on wage issues. In April 1893, for instance, fifty- two to-bacco cutters refused to start work on the grounds that they could not feed tobacco into the hoppers of the cutting machines by using only their hands.

In response, the director of the Régie Company let them use wooden sticks to feed the hoppers, as they were accustomed to doing in the past. Despite this move by the company, the strikers did not re-turn to work and instead demanded an increase in their wages.31 Thirteen years later, in late March 1906, about two hundred to two hundred seventy workers went on strike when the Régie announced that it was going to forego its annual Easter pay-ment that year.32

The Ottoman government initially took a firm stand against workers’ wage- related demands. In the 1893 strike, Sultan Abdülhamid II warned his bureaucrats that if the necessary measures were not taken, such incidents would give rise to labor troubles similar to those in Europe.33 In line with this warning, the Grand Vizier held a meet-ing with the director of the Régie on the first day of the strike and advised him to fire those work-ers who would not return to work by the end of the day.34 In the 1906 strike, however, the govern-ment followed a different policy. The sultan or-dered the relevant government officials to have the Régie pay the customary Easter money. If this was not possible, the order continued, the gov-ernment itself would make the payment from its share of the Régie’s profits.35 This change in gov-ernment policy occurred for at least two reasons. First, the sultan’s generous offer was probably a part of the ruling strategy of presenting himself as a benevolent ruler, especially on religious holi-days. Thus, he sought to secure the approval of his subjects.36 Second, strikers, both men and women, devised effective protest tactics to get their voices heard. Within hours after the strike declaration, the sultan was informed that the next day work-

37. BOA, I..HUS 1324.S.1 (4 Safer 1324/29 March

1906).

38. BOA, DH.MKT 912/53, report from the Pre-fect of Istanbul to the Ministry of Interior (17 Mart 1322/30 March 1906).

39. See Mentzel, “Nationalism and Labor Move-ment in the Ottoman Empire,” 107, and Tanin, “Reji Amelesi,” 31 Temmuz 1324/13 August 1908.

40. BOA, DH.MKT 2681/20, rules and regula-tions of the Cigarette Makers’ Association.

41. See Nacar, “Tobacco Workers in the Late Ot-toman Empire,” 128 – 35; BOA, DH.MKT 912/53, report from the Grand Vizierate to the Ministry of Interior (17 Mart 1322/30 March 1906); report from the Ministry of Police to the Ministry of Interior (17 Mart 1322/30 March 1906); report from the Prefect of Istanbul to the Ministry of Interior (17 Mart 1322/30 March 1906).

42. See Mentzel, “Nationalism and Labor Move-ment in the Ottoman Empire,” 107; Tanin, “Reji Amelesi,” 31 Temmuz 1324/13 August 1908; Tanin, “Reji,” 2 Agustos 1324/15 August 1908; BOA, ZB 485/17, letter from the Ministry of Po-lice to the Régie Company (30 Temmuz 1324/12 August 1908); BOA, DH.I

.D 107/51, report from

the Régie Superintendent to the Ministry of Fi-nance (25 Temmuz 1328/7 August 1912).

Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East • 34:1 • 2014212

ers would march to the company’s headquarters in the Galata district of Istanbul. This decision caused anxiety among government officials.37 A possible attack by the strikers on the Régie build-ing would provoke protests from foreign states and financial institutions and put the government in a difficult position. The orders issued by the sultan for the immediate payment of the Easter money and to prevent the workers’ demonstration from taking place echoed this anxiety. As a result of this change in the government’s policy, the Régie of-ficials also adopted a conciliatory position toward the strikers. On the second day of the strike, the general director of the company announced that they were ready to increase the Easter payment by 100 percent.38

Labor activism in the Cibali factory gained new momentum after the Constitutional Revo-lution. In the period between 1908 and 1914, workers’ demands concerning conditions of em-ployment became more diversified. In a petition addressed to the factory administration in July 1908, for instance, a group of workers demanded the following: a pay raise of 100 percent, pensions, and provision of free tobacco.39 Another important development in this period was the emergence and growth of labor organizations. In September 1908, some Greek and Jewish cigarette workers in the factory founded the Cigarette Makers’ Associa-tion (CMA). The new organization had restricted membership rules and a male- dominated struc-ture. Membership was open only to cigarette mak-ers and packers. Packers, however, did not have the right to be elected as members of the administra-tive board. It was also difficult for women to break into positions of power. All twelve workers on the association’s first administrative board were men.40

The CMA survived only a few months and was closed down in late December 1908. Almost

two years later, in the summer of 1910, workers founded a stronger and more inclusive labor or-ganization, the Union of the Cibali Factory Work-ers (UCFW). Until then, workers’ organizational efforts and strikes remained localized, centered in specific departments. The 1893 strike did not spread beyond the tobacco cutting department. In the 1906 strike, mobilized workers came mostly from the ranks of cigarette makers and packers.41 Similarly, the CMA closed its doors to tobacco cut-ters and sorters. The UCFW challenged this pat-tern of labor activism. The sources consulted do not mention the number and composition of its members; however, they show that at certain his-torical moments the UCFW served as a platform where male and female workers from different departments could come together to discuss their problems and take collective action. Indeed, as in-dicated in the following section, it played a critical role in the organization of a major strike in April 1911, which involved nearly the entire body of two thousand two hundred workers in the factory.

After the Constitutional Revolution, the Régie usually responded to labor activism in the Cibali factory by threatening workers with unem-ployment. When, for instance, workers did not win their demand for a 100 percent pay raise in July 1908, they began to make preparations for a strike. Before their preparations were finalized, however, the decisive action came from the Régie officials. As hundreds of workers arrived at the factory on 12 August 1908, they saw that the gates were closed. Pieces of paper hanging on the walls of the build-ing informed them of the factory’s closure until further notice. Workers who were now unemployed withdrew their initial demand, and the parties, with the intervention of the Ottoman government and the Committee of Union and Progress, agreed on wage increases of 40 to 50 percent.42 Shortly

43. BOA, DH.MKT 2681/20, an announcement by the Régie Company (7 Kanunuevvel 1908/7 December 1908).

44. See Ökçün, Ta’til- i Esgal Kanunu, 2 – 4, 111 – 13.

45. BOA, DH.MKT 2681/20, report from the Ministry of Interior to the Ministries of Police

and Trade and Public Works (1 Kanunuevvel 1324/14 December 1908).

46. See, for instance, BOA, DH.I.D 126/19, report

prepared by the Council of State (8 Kanunusani 1326/21 January 1911).

47. BOA, DH.EUM.KADL 8/23, letter from the Ministry of Finance to the Security General Directorate (3 Subat 1326/16 February 1911); DH.EUM.KADL 14/22, report from the Istanbul Police Directorate to the Security General Di-rectorate (16 Subat 1326/1 March 1911).

213Can Nacar • Régie Monopoly and Tobacco Workers in Late Ottoman Istanbul

after this conflict, the members of the CMA were also confronted with the threat of dismissal. In an announcement dated 7 December 1908, Régie officials wrote the following: “Those who want to continue working in the Régie factories must sever their relations with the association [the CMA]. We ask its leaders to dissolve the association within five days. Otherwise, they will be dismissed.”43

Régie officials also often resorted to legal measures to prevent strikes and to destroy unions. In this regard, the strike laws of 1908 and 1909 were particularly important. While a strike wave was sweeping the empire in the fall of 1908, the Ottoman government enacted a provisional strike law. Less than a year later, in August 1909, it was adopted with minor changes as a permanent law by the new Ottoman parliament. Both versions of the strike law dealt with labor disputes in compa-nies that operated public services, such as ports, railways, and tramways. They permitted strikes only after the failure of conciliation among work-ers, their employers, and government officials from the Ministry of Trade and Public Works. Moreover, they prohibited workers who were em-ployed by public service companies from forming and joining labor unions.44 As soon as the provi-sional law of 1908 entered into force, Régie offi-cials claimed that the company’s employees were bound by its terms. In the aforementioned Régie announcement, for instance, they wrote that the CMA functioned as a labor union and thereby vio-lated the law. This argument initially found sup-port in government circles. In a report addressed to the Ministry of Police, the Ministry of Interior stated that if the CMA continued its activities, its founding members had to be arrested for violating the strike law.45

After being threatened with dismissal and arrest, the members of the CMA had no choice but to dissolve the organization. However, the Ré-gie’s argument that the strike law covered workers in the tobacco industry did not remain unchal-

lenged for long. When company officials claimed the illegality of the 1911 strike at the Cibali factory, they did not get a favorable response from the Ot-toman government. By then, the Council of State had ruled at least twice that tobacco companies in the empire, including the Régie, did not provide a public service. Therefore, tobacco workers had the right to found labor unions and to go on strike without any prior permission or notice.46 Feeling empowered by this decision, workers in the Cibali factory turned the 1911 strike into a mass action. The following two sections investigate the causes, organization, and consequences of the strike.

Mounting Social Tensions in the Cibali Factory, February 1911In the second week of February 1911, Régie officials wrote to the Ministry of Interior that some workers in the Cibali factory had behaved violently toward the factory director. In response, officers from the nearby Unkapanı Police Station contacted the in-volved workers and notified them of the govern-ment’s intolerance of activities that violated law and order. Moreover, the company declared that if such an event happened again, those involved would be severely punished. Although peace was restored in the factory after this declaration and the intervention by the police, company and gov-ernment officials expressed their concerns about the possibility of further conflict. In a report ad-dressed to the Ministry of Finance, for instance, the Régie superintendent noted that unless the government took effective measures, workers might soon resort to violent actions, such as ma-chine breaking. Passing through the Ministry of Finance, the Security General Directorate, and the Istanbul Police Directorate, this report was ul-timately brought to the attention of the Unkapanı Police Station. In accordance with the orders of their superiors, police officers at the station con-ducted an investigation and wrote a report on the recent conflict in the factory.47

48. BOA, DH.EUM.KADL 14/22, report from the Istanbul Police Directorate to the Security Gen-eral Directorate (16 Subat 1326/1 March 1911).

49. Ibid.

50. According to the strike law, to initiate the conciliation procedure, workers had to present a petition to the Ministry of Trade and Public Works listing their grievances and presenting their demands. See Ökçün, Ta’til- i Esgal Kanunu, 111.

51. BOA, DH.EUM.KADL 14/22, report from the Istanbul Police Directorate to the Security Gen-eral Directorate (19 Mart 1327/1 April 1911).

Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East • 34:1 • 2014214

According to the aforementioned police re-port, on 10 February, about twenty workers pre-sented a list of demands to the factory director, M. Marshal. Perceiving these demands as a threat to the established order in the factory, M. Marshal asked the Unkapanı Police Station to advise work-ers not to take any further action until the gen-eral director of the Régie returned from Europe. Acting upon this request, police officers invited four or five workers to the station and explained to them the situation. Although the workers agreed to wait for the arrival of the general director, M. Marshal was worried about a possible escalation of the situation. To appease his concerns, the report continued, two police officers were sent to the fac-tory. Once there, the officers held a meeting with three workers’ representatives. At this meeting, the representatives stated that workers had not en-gaged in harmful acts against the Régie but asked for the restoration of workers’ rights that had been lost before the Constitutional Revolution. For this purpose, they had already presented a petition to the Ministry of Trade and Public Works.48

The petition listed three demands meant to win improvements in wages and benefits. First, workers wanted the restoration of wages that had been cut by the Régie in 1890 and 1891. While the police report does not provide information on the extent of the wage cuts, other sources provide a few clues. By the beginning of the twentieth century, for instance, male cigarette rollers had suffered a serious drop in piecework wages, from eleven pi-asters to six. Perhaps this decline had something to do with the company’s wage policy in 1890 and 1891. Most of the workers who earned their living in the Cibali factory in the early 1890s, however, had left the Régie’s employment by 1911. Yet, by sharing their workplace stories with younger co-workers, this earlier generation of workers had apparently contributed to the development of a collective memory among workers from different age groups. That is why, in 1911, the recovery of rights lost long ago was still a cause to be fought

for. Second, as a response to unhealthy working conditions in the factory, the petitioners asked the Régie to pay sick benefits to ailing workers. Finally, they demanded a wage increase for female ciga-rette workers.49

In presenting their petition to the Ministry of Trade and Public Works, the workers had resorted to the conciliation procedure established in the strike law.50 It appears that they were not informed of the Council of State’s decision concerning the strike law and tobacco companies. On the contrary, police officers warned them to act in accordance with the strike law. The documents consulted do not mention how ministry bureaucrats responded to the petition. Taking into account the Régie’s sta-tus with respect to the strike law, they quite possibly did not initiate a conciliation meeting between the workers and company officials. The Régie, for its part, made no serious attempts to appease workers and to prevent further conflict in the factory. Thus, the tension between the parties escalated and even-tually led to a strike in April 1911.

Workers on Strike: The Cibali Factory in April 1911On Thursday, 30 March, a group of workers em-ployed at piecework rates had earned a daily wage of six piasters. When the factory accountant at-tempted to pay them only three piasters, the work-ers insisted on full remuneration for their labor. The issue soon came before the factory director, and he fired twenty- two workers who refused to back down from their demand. Although some of these workers applied through their foremen for reemployment, they were turned away from the factory gates. The next morning, the director’s de-cision caused unrest in the factory. Some of the workers announced that they were going to declare a strike. In response, the factory administration informed the Unkapanı Police Station of the in-cident, and several police officers quickly arrived at the factory. The officers induced workers to re-sume their work and asked foremen involved in the unrest to accompany them to the police station.51

52. Ibid.

53. See Dogruel and Dogruel, Osmanlı’dan Günü-müze Tekel, 82.

54. See BOA, DH.EUM.KADL 14/22, report from the Istanbul Police Directorate to the Security General Directorate (19 Mart 1327/1 April 1911). See Mentzel, “Nationalism and Labor Move-ment in the Ottoman Empire,” 207.

55. See Dogruel and Dogruel, Osmanlı’dan Günümüze Tekel, 82 ; BOA, DH.EUM.KADL 14/22, report from the Istanbul Police Direc-torate to the Security General Directorate (24 Mart 1327/6 April 1911). Vlahof Effendi was a deputy from Salonica. For his political activities at the beginning of the twentieth century, see Haupt and Dumont, Osmanlı I

.mparatorlugunda

Sosyalist

Hareketler, 241 – 80. Muradyan Effendi was a deputy from Kozan and a member of Hncha-kian Party.

56. BOA, DH.EUM.KADL 14/22, report from the Istanbul Police Directorate to the Security Gen-eral Directorate (24 Mart 1327/6 April 1911).

215Can Nacar • Régie Monopoly and Tobacco Workers in Late Ottoman Istanbul

Once in the station, the foremen were re-minded of their right to go on strike but also warned not to hold illegal meetings. To this they re-sponded that a strike would occur only if the Régie did not agree to reinstate the fired workers. But, they added, workers would in any case obey the law and the orders of the government. After this meet-ing with police officers, the foremen returned to the factory to resume their work. During the rest of the day, workers waited in vain for a favorable response from the factory administration and ulti-mately decided to call a strike on 1 April 1911.52 In a last- minute attempt to prevent the strike, the fac-tory director sought to invoke the strike law. In a letter addressed to the Ministry of Trade and Public Works, he wrote that the Régie workers were bound by the terms of the strike law. Thus, he argued, they did not have the right to declare a strike. But, as mentioned above, the ministry rejected this applica-tion, and the strike began as scheduled.53

After receiving a negative response from the Ministry of Trade and Public Works, the Régie de-cided to close the Cibali factory on the first day of the strike. It had used this tactic before, in August 1908, and had convinced the workers to moderate their wage demands. However, this time the out-come was disappointing for the Régie. When the factory was reopened on 4 April, only forty workers returned to work. After this failure, company offi-cials made several attempts to drive a wedge in the strikers’ ranks. For instance, they promised higher wages to women cigarette makers and packers in exchange for their return to the factory. Contrary to their expectations, the women workers rejected the offer. The workers’ willingness to continue the strike shows that they were prepared for it both or-ganizationally and financially.54 In this regard, one should note the critical role played by the UCFW.

When Régie officials refused to meet the workers’ demands in February 1911, the members

of the UCFW began to make preparations for a strike. It seems that they convinced the major-ity of workers of the successes to be gained from strike action. According to newspaper reports, for instance, women workers rejected the company’s aforementioned offer with the encouragement of the UCFW. The union members had also success-fully built up a strike fund by April 1911. After the declaration of the strike, the UCFW functioned as a discussion platform for the strikers. Through this platform, the strike developed well beyond the issue that precipitated it. When the UCFW’s general assembly convened on 5 April with the participation of about four hundred workers and two left- wing deputies, Vlahof and Muradyan Ef-fendis, the workers formulated and put forth the following demands: a proper increase in wages, a decrease in work hours, provision of benefits for sick and injured workers, a ban on the employment of children under the age of fourteen, and limits on the employment of workers under eighteen. The widespread participation in the strike shows that these demands reflected concerns common to almost all workers.55

The union meetings also improved workers’ morale and gave them a forum to discuss contro-versial issues such as strikebreaking. Vlahof and Muradyan Effendis went to the 5 April meeting apparently with the latter goal in mind. In their re-marks opening the meeting, both of them stressed the importance of unity among the workers. After the deputies, the president of the UCWF took the floor. In his speech, the president, named Koço, first described the events that led to the strike and then called for firm and resolute action on the part of the strikers. If, Koço said, the workers submitted a list of their demands to parliament, the deputies would definitely take this list into ac-count. However, he concluded, the Régie would ac-cept their demands only if the strike continued.56

57. Ibid.

58. BOA, DH.EUM.KADL 14/22, report from the Istanbul Police Directorate to the Security General Directorate (3 Nisan 1327/16 April 1911). The police report gave Ahmed’s occupation as worker but did not provide any information with regard to Eleni’s occupation.

59. Tanin, “Reji Amelesinin Grevi,” 25 Mart 1327/7 April 1911.

60. BOA, DH.EUM.KADL 14/22, report from the Istanbul Police Directorate to the Secu-rity General Directorate (24 Mart 1327/6 April 1911); Mentzel, “Nationalism and Labor Move-ment in the Ottoman Empire,” 208; Dogruel and Dogruel, Osmanlı’dan Günümüze Tekel, 82.

61. BOA, DH.EUM.KADL 8/23, letter from the Ministry of Finance to the Security General Di-rectorate (3 Subat 1326/16 February 1911).

62. The strike in Salonica lasted until May 1911. See Hadar, “Jewish Tobacco Workers in Salon-ika,” 132 – 33.

63. BOA, DH.I.D 107/23, telegram from the Gov-

ernor of Salonica province to the Ministry of Interior (27 Mart 1327/9 April 1911). Strikers in Kavala issued the following demands: an in-crease in wages, a decrease in work hours, and the employment of only men as tobacco sort-ers. The strike, according to newspaper reports, lasted more than two weeks. By the time strik-ers returned to work, they had won some con-

cessions. See Tanin, “Amele ve Sermayedarın I.htilafı,” 29 Mart 1327/11 April 1911 ; Tanin,

“Amele Grevi,” 13 Nisan 1327/26 April 1911; and Mentzel, “Nationalism and Labor Movement in the Ottoman Empire,” 208.

64. BOA, DH.EUM.KADL 14/22, letter from the Martial Court to the Security General Director-ate (30 Mart 1327/12 April 1911). After a revolt against the new constitutional regime in April 1909, the Ottoman government imposed mar-tial law, which remained in force until 1918.

Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East • 34:1 • 2014216

The president’s remarks were mainly addressed to the workers who did not participate in the strike. Most of them probably thought they could achieve their workplace- related goals through parliament.

The president’s speech sparked a debate in the meeting over how to deal with strikebreakers. It appears from this debate that some union mem-bers did not participate in the strike. Several work-ers demanded the expulsion of these people from their ranks. In response, Koço took the floor again and asked the audience not to adopt a hostile at-titude toward strikebreakers. Moreover, he pro-posed that the administrative board of the UCFW be assigned the responsibility of persuading strike-breakers to quit their jobs.57 With this move, Koço sought to relieve the tension in the room and to prevent actions that would undermine the strikers’ position. The general assembly accepted his pro-posal, but an incident ten days after the meeting shows that the administrative board’s attempts at persuasion achieved limited, if any, success. On Saturday, 15 April, the director of the Régie met with some of the strikers to talk about their de-mands. While this meeting was going on, an Ital-ian strikebreaker named Francois went out of the factory and slapped Ahmed and Mademoiselle Eleni, who were probably picketing in front of the building, twice in the face. The other strikers as-sembling in the nearby coffeehouses heard the cries of their friends and soon gathered in front of the factory. Police forces dispersed the angry crowd before a more serious incident occurred.58

Although the presence of strikebreakers pro-voked violence, it is important to emphasize that in mid- April 1911, they comprised only a tiny minor-ity of the labor force in the Cibali factory. The high

level of participation in the strike generated visible and widespread excitement among other workers in the empire. For instance, representatives from tai-lors’ and porters’ unions attended the 5 April meet-ing to express their support for the strike.59 Like-wise, the Régie workers in different provinces sent letters to their counterparts in the Cibali factory, expressing their support for the strike and asking for further information about it. Moreover, in early April, some newspapers reported that the tobacco workers’ organizations in the Balkans and Istanbul would merge.60 All of these developments raised se-rious concerns among government officials.

The government officials mainly feared the spread of unrest from the Cibali factory into other industrial enterprises. In February 1911, the Min-istry of Finance warned the Security General Di-rectorate that a violent labor protest in the Cibali factory could spread to the other Régie branches in the empire and result in considerable financial costs to the government.61 This fear was realized in the spring of the same year. A strike broke out at the Régie’s Salonica factory in late March, even before tobacco workers in the imperial capital took to the streets.62 A few weeks later, on 9 April, news came of a recent strike in tobacco warehouses in Kavala. In reaction to the strike, major tobacco companies closed their warehouses in Kavala and other nearby towns, including Salonica. Thus, about ten thousand workers became unemployed.63 Facing a wave of labor unrest, the Ottoman gov-ernment adopted new measures restricting the ac-tivities of the strikers, especially in Istanbul. The Martial Law Court, for instance, banned a meeting that the strikers planned to hold in the UCFW hall on 14 April.64 Around the same time, the Régie

65. BOA, DH.I.D 107/51, letter from the Ministry

of Interior to the Security General Directorate (27 Mart 1327/9 April 1911).

66. See Mentzel, “Nationalism and Labor Movement in the Ottoman Empire,” 210.

67. Brummett, Image and Imperialism in the Ot-toman Revolutionary Press, 185 – 86.

68. See Mentzel, “Nationalism and Labor Movement in the Ottoman Empire,” 210.

69. Tanin, “Reji Fabrikası Amele Teavün Cemiy-eti,” 27 Mayıs 1327/9 June 1911.

70. BOA, DH. I.D 107/51, report from the Régie

Superintendent to the Ministry of Finance (25 Temmuz 1328/7 August 1912).

71. The survey defined a child as younger than fifteen years of age. See Ökçün, Osmanlı Sanayii 1913 – 1915 I

.statistikleri, 17, 76.

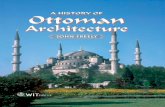

Figure 3. “Régie Strikers” (“Reji grevrileri”). Cartoon published in Kalem 123, no. 5 (1911)

217Can Nacar • Régie Monopoly and Tobacco Workers in Late Ottoman Istanbul

made a move to end the strike in the Cibali factory. It announced that new workers would be recruited in place of the strikers who did not return to work on 14 April.65

Despite pressure from both the government and the Régie, only about one hundred strikers had returned to work at the Cibali factory by 15 April.66 During the latter half of the month, no marked change in the strike situation occurred. After a month without pay and with no clear prog-ress in negotiations, the strikers’ morale probably began to erode, and the company gradually gained the upper hand. It was in this context that the sa-tirical journal Kalem published a cartoon showing two emaciated Régie strikers (see fig. 3). Both of these men had ragged clothing and looked help-less. In analyzing this cartoon, Palmira Brummett rightly argues that its message is a fatalistic one: “The workers are exploited and impoverished. They strike; but there is no suggestion that their conditions will improve.”67 The sources consulted do not mention how this message was received by the strikers and exactly how long the strike contin-ued after the publication of the cartoon in early May. Yet it is evident that by early June, the conflict had been settled and order had been restored in the factory.68

At the end of the conflict, the Régie made few, if any, concessions to the strikers. Shortly after the strike, for instance, the Régie workers in Istanbul founded a mutual aid association whose primary goal was to offer sick and death benefits for its members.69 This initiative strongly suggests that the company refused the strikers’ demand for sick benefits. The strikers also had to give up their demand for higher wages. According to the Régie superintendent, in the period between 1908 and 1912, workers in the Cibali factory received a pay raise only once, and that was in 1908, three years before the strike.70 Likewise, even if the company had initially reduced the use of child labor in line

with the strikers’ wishes, the practice did not last long. An industrial survey conducted by the Min-istry of Trade and Public Works shows that in 1913 and 1915, tobacco packers in the Cibali factory were mostly children.71

Finally, the 1911 strike had a profound effect on subsequent labor actions in the Cibali factory. After the experience of defeat, the majority of the workers did not favor the use of strike action as a means of having their demands met. That is why, in June 1912, they asked the Ministry of Trade and Agriculture to set up a conciliation committee to discuss their demand for higher wages. In order to prevent a new conflict in the factory, the ministry bureaucrats gave a positive response. Yet, during the conciliation meetings, the Régie adopted a tough negotiating stance and made no concessions on wages. In response, about one hundred work-ers assaulted two high- ranking factory officials and some others petitioned the Grand Vizierate

72. BOA, DH.I.D 107/51, petition from the work-

ers of the Cibali factory to the Grand Vizierate and report from the Régie Superintendent to the Ministry of Finance (25 Temmuz 1328/7 Au-gust 1912).

73. See Kırpık, “Osmanlı Devleti’nde I.sçiler ve

I.sçi Hareketleri,” 314.

74. See Ilıcak, “Jewish Socialism in Ottoman Sa-lonica,” 132.

Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East • 34:1 • 2014218

for support of their cause.72 Although these actions soon proved ineffective in changing the Régie’s policy, the workers, in contrast to the previous year, did not go on strike.

EpilogueBy the beginning of World War I, the labor move-ment in the Cibali factory had lost its momentum. The 1911 strike was defeated, the next year’s con-ciliation meetings ended without much progress, and finally labor unions active in the factory, like all others in the empire, were dissolved by the gov-ernment in 1913.73 However, this does not make the story of the tobacco workers in late Ottoman Istanbul merely a chronicle of failure and defeat. In the spring of 1911, a strike wave involving thou-sands of workers swept the tobacco factories and warehouses in Istanbul and the Salonica province. Yet labor unrest in the imperial capital differed from that in other places in one crucial respect. While there were substantial tensions and conflicts between male and female workers in the Salonica province,74 the strike in the Cibali factory brought together about two thousand working men and women of different ethnicities and religions. This unity stemmed from the articulation of a set of de-mands that were meant to address workers’ com-mon grievances, and the workers’ organizational efforts, in which the UCFW played a key role.

The strikers in the imperial capital were so well organized that the Régie’s various attempts to break their ranks remained futile. Moreover, they were not isolated in their battle. Workers in different provinces and sectors as well as politi-cians publicly expressed support for the strike. If the strike had been won, the early contacts among the different labor groups would perhaps have evolved into sophisticated networks of solidarity. These networks of solidarity could have strongly challenged the government’s decision to dissolve all labor unions in the empire. Overall, the events that took place in the first two weeks of the strike show that although short- lived, there were mo-ments of unity, solidarity, and hope in the story

of the tobacco workers in Istanbul. Those histori-cal moments might have set the labor movement, both in the Cibali factory and in the empire, on a different and more promising path in the early 1910s.

References1296 Senesi Martı İbtidasından Şubatı Nihayetine Değin Bir

Sene Zarfında Memâlik- i Mahrûsa- i Şahane Mahsulât- ı Arziyye ve Sınaiyyesinden Diyar- ı Ecnebiyeye Giden ve Bil-cümle Diyar- ı Ecnebiyeden Memâlik- i Mahrûsa- i Şahaneye Gelen Eşyanın Cins ve Mikdarını Mübeyyin Tanzim Olu-nan İstatistik Defterlerinin Hûlâsatü’l- Hûlâsa Cedvelidir (Foreign Trade Statistics of the Ottoman Empire for March 1880 – March 1881). Dersaadet (Istanbul), AH 1301/AD 1883 – 1884.

1325 Sene- i Hicriyesine Mahsus Selanik Vilayet Salnamesi (The Salonica Province Yearbook for 1907 – 8). Selanik, 1907 – 8.

Balsoy, Gülhan. “Gendering Ottoman Labor History: The Cibali Régie Factory in the Early Twentieth Century.” International Review of Social History 17 (2009): 45 – 68.

Brummett, Palmira. Image and Imperialism in the Ottoman Revolutionary Press, 1908 – 1911. Albany: State Univer-sity of New York Press, 2000.

Doğruel, Fatma, and A. Suut Doğruel. Osmanlı’dan Günü-müze Tekel (Monopoly Administration: From Ottoman Em-pire to the Present Day). Istanbul: Türkiye Ekonomik ve Toplumsal Tarih Vakfı, 2000.

Hadar, Gila. “Jewish Tobacco Workers in Salonika: Gen-der and Family in the Context of Social and Ethnic Strife.” In Women in the Ottoman Balkans: Gender, Cul-ture, and History, edited by Amila Buturović and İrvin Cemil Schick, 127 – 52. New York: I. B. Tauris, 2007.

Haupt, George, and Paul Dumont. Osmanlı İmparator-luğunda Sosyalist Hareketler (Socialist Movements in the Ottoman Empire). Istanbul: Gözlem Yayınları, 1977.

Ilıcak, Şükrü. “Jewish Socialism in Ottoman Salonica.” Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 2, no. 3 (2002): 115 – 46.

Karakışla, Yavuz Selim. “Osmanlı İmparatorluğu’nda 1908 Grevleri” (“The 1908 Strikes in the Ottoman Empire”). Toplum ve Bilim (Society and Science), no. 78 (1998): 187 – 208.

219Can Nacar • Régie Monopoly and Tobacco Workers in Late Ottoman Istanbul

Kırpık, Cevdet. “Osmanlı Devleti’nde İşçiler ve İşçi Hare-ketleri (1876 – 1914)” (“Labor and Movements of Labor in the Ottoman Empire”). PhD diss., Süley-man Demirel University, 2004.

Mentzel, Peter Carl. “Nationalism and Labor Movement in the Ottoman Empire, 1872 – 1914.” PhD diss., Uni-versity of Washington, 1994.

Moore, Laurence S. “Some Phases of Industrial Life.” In Constantinople Today, or the Pathfinder Survey of Con-stantinople, edited by Clarence Richard Johnson, 165 – 99. New York: Macmillan, 1922.

Nacar, Can. “Tobacco Workers in the Late Ottoman Empire: Fragmentation, Conflict, and Collective Struggle.” PhD diss., State University of New York – Binghamton, 2010.

Ökçün, Gündüz. Osmanlı Sanayii 1913 – 1915 İstatistikleri (Ottoman Industrial Statistics: 1913 – 1915). Istanbul: Hil Yayın, 1984.

——— . Ta’til- i Eşgal Kanunu, 1909: Belgeler- Yorumlar (The 1909 Strike Law: Documents and Comments). Ankara: Sermaye Piyasası Kurulu, 1996.

“Osmanlı Tütünleri ve Reji İdaresi” (“Ottoman Tobac-cos and the Régie Administration”). Servet- i Fünun (Wealth of Knowledge) 149 (1894): 296.

“The Ottoman Tobacco Industry.” Journal of the Society of Arts 42 (1893 – 1894): 733 – 34.

Özbek, Nadir. Osmanlı İmparatorluğu’nda Sosyal Devlet: Siyaset, İktidar ve Meşruiyet (1876 – 1914) (Welfare State in the Ottoman Empire: Politics, Power, and Legitimacy [1876 – 1914]). Istanbul: İletişim Yayınları, 2002.

Quataert, Donald. “The Age of Reforms, 1812 – 1914.” In An Economic and Social History of the Ottoman Empire, vol. 2., 1600 – 1914, edited by Halil İnalcık with Donald Quataert, 759 – 943. Cambridge: Cambridge Univer-sity Press, 2004.

——— . “The Economic Climate of the ‘Young Turk Rev-olution’ in 1908.” Journal of Modern History 51, no. 3 (1979): 1147 – 61.

——— . “The Régie, Smugglers, and the Government.” In Social Disintegration and Popular Resistance in the Ottoman Empire, 1881 – 1908: Reactions to European Eco-nomic Penetration, 13 – 40. New York: New York Univer-sity Press, 1983.

Spataris, Haris. Biz İstanbullular Böyleyiz! Fener’den Anılar, 1906 – 1922 (Istanbulers, This Is How We Are! Memories of Fener). Istanbul: Kitap Yayınevi, 2004.

“Tabakerzeugung, Bearbeitung und Handel in der Euro-paischen Türkei” (“Tobacco Production, Processing, and Trade in the European Turkey”). Berichte über Handel und Industrie (Reports on Trade and Industry) 18, no. 7 (1912): 255 – 346.