The emotional journey of the beginning teacher: Phases and ...

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of The emotional journey of the beginning teacher: Phases and ...

Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found athttps://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rred20

Research Papers in Education

ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rred20

The emotional journey of the beginning teacher:Phases and coping strategies

Henrik Lindqvist, Maria Weurlander, Annika Wernerson & Robert Thornberg

To cite this article: Henrik Lindqvist, Maria Weurlander, Annika Wernerson & Robert Thornberg(2022): The emotional journey of the beginning teacher: Phases and coping strategies, ResearchPapers in Education, DOI: 10.1080/02671522.2022.2065518

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2022.2065518

© 2022 The Author(s). Published by InformaUK Limited, trading as Taylor & FrancisGroup.

Published online: 18 Apr 2022.

Submit your article to this journal

View related articles

View Crossmark data

RESEARCH ARTICLE

The emotional journey of the beginning teacher: Phases and coping strategiesHenrik Lindqvist a, Maria Weurlander b, Annika Wernerson c

and Robert Thornberg a

aDepartment of Behavioural Sciences and Learning, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden; bDepartment of Education, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden; cCLINTEC, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden

ABSTRACTResearch on the transition from teacher education to beginning to teach have focused on the ability to teach, as well as on classroom practices, and how complicated socialisation processes impede developing skills when starting to teach. The aim of the study was to investigate emotionally challenging situations during teacher edu-cation and when starting to teach, with a focus on how the partici-pants’ perspectives and coping strategies changed over time. In this study, 20 participants were followed during their final year of teacher education and into their first year of teaching. Data was collected through interviews and written self-reports. A constructivist grounded theory methodology was adopted. We found that new teachers experience three main emotional phases as they move from teacher education and into teaching, namely (1) opposite positions, (2) enthu-siasm mingled with fear, and (3) a rollercoaster of emotions. Emotions and coping strategies linked with the phases are illustrated, and practical implications are discussed.

ARTICLE HISTORY Received 28 May 2021 Accepted 17 March 2022

KEYWORDS Student teachers; beginning teachers; coping; grounded theory

Introduction

Learning to become a teacher does not end when a student teacher graduates from teacher education. Their journey of learning and developing their teaching compe-tence, including how to deal with their emotions as a teacher, will continue starting on the very first day as a beginning teacher. Previous studies have followed student teachers as they start to work as a teacher (Cochran Smith et al., 2012), and have demonstrated that their teaching skills vary at the beginning of their teaching career. Other studies have shown that new teachers face complicated socialisation processes and collegial situations at the outset of their careers (Caspersen and Raaen 2014; Kelchtermans and Ballet 2002). Exploring the transition from teacher education to a teaching position is important if we are to understand the complexities of starting to teach in a school, which is especially important given Sweden’s current teacher shortage (Swedish National Agency for Education 2019).

CONTACT Henrik Lindqvist [email protected] Department of Behavioural Sciences and Learning, Linköping University, SE-58183 Linköping, Sweden

RESEARCH PAPERS IN EDUCATION https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2022.2065518

© 2022 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Emotions and coping

There is an intense debate about how to define emotions (Izard 2010; Oatley and Johnson- Laird 2014). Emotions can be understood as neural circuits and neurobiological processes, response systems, phenomenal experiences, or feelings, or as feeling-processes that include perceptual-cognitive processes and that motivate and organise cognition and action (Izard 2010). According to Oatley and Johnson-Laird (2014), emotions involve appraisals, sub-jective experiences, emotional expressions, physiological changes, and action tendencies. Emotions influence thinking, learning, decision-making, actions, well-being, and social relationships (Izard 2010). Other researchers emphasise emotions as relational. In the context of teachers, for example, Chen (2016) argued that ‘teacher emotional experiences not only occur in individual’s psychological activities, but also involve the emotional feelings of others and interactions with personal, professional, and social environment’ (p. 69). In that way, emotions are not to be seen as merely individual and psychological, but also need to be understood as social, interactive and performative (Zembylas 2007).

In this study, ‘emotional challenges’ refer to situations that teachers found hard to handle or are experienced with unpleasant or challenging emotions. Examples of emotional challenges might be meeting an aggressive pupil, or persistent disorder and misbehaviours in the classroom. Teaching is an emotional occupation and coping strategies must be used to deal with issues that come up in a teacher’s day-to-day work (Admiraal, Korthagen, and Wubbels 2000). When teachers ‘perceive an imbalance between situational demands in their working experience and their ability to respond adequately to these’ (Travers 2017, 25), teachers may become stressed. Teacher stress, in turn, can be defined as unpleasant emotions such as anxiety, tension, anger, frustration or depression, that result from their work as a teacher (Kyriacou 2001). Teacher stress is therefore always connected to emotions and ineffective or inadequate coping with perceived resources and demands (Lazarus and Folkman 1984). Teacher stress has been found to be associated with teacher burnout (Garciá et al., 2019), which, in turn, has a negative impact on the academic motivation and achievement of their pupils (Madigan and Kim 2021a), and increases the risk of teacher attrition (Magidan & Kim, 2021b).

According to Lazarus and Folkman (1984), challenges are produced by a complex and subjective interplay between situational demands and individual resources. Individuals evaluate whether situations are threatening or challenging, how their wellbeing could be affected, and whether and how they can cope with the situation. Coping in general can be defined as efforts to master a problem in the person- environment relationship, through tolerating, amending, or altering the problem (Admiraal, Korthagen, and Wubbels 2000), and coping strategies refer to specific cognitive and behavioural efforts aimed at reducing and overcoming challenges (Chaaban and Du 2017). In coping literature, coping strategies are commonly divided into (a) direct-action, problem-focused strategies (aimed at eliminating the sources of challenges), and palliative, emotion-focused strategies (focusing on mod-ifying internal/emotional reactions instead of eliminating the cause of the challenge) (Lazarus and Folkman 1984; Sharplin et al., 2011).

Teacher emotions and coping with perceived emotional challenges are relevant in teacher education, especially during the transition from teacher education to actual teaching. There are few longitudinal studies about the transition from teacher education

2 H. LINDQVIST ET AL.

into actual teaching, or about emotional challenges faced, or how beginning teachers cope. Emotions are discussed in the literature as something important for the beginning teacher to work with, but even so, little is known about emotions and processes of coping during the transition from teacher education to a position as a teacher.

Emotional challenges and reality shock when starting to teach

For the remainder of this article, the phrases ‘beginning teacher’ or ‘new teacher’ will be used to refer to a teacher (of any age) who has recently ended their teaching education and is now dealing with pupils in a classroom setting. Previous research on beginning teachers has shown that emotional challenges include meeting conflicting perspectives, beliefs, and practices concerning teaching and learning in negative school contexts (Flores and Day 2006). In contrast, teacher education presents relatively consistent beliefs and perspectives about the nature of teaching and learning. Emotional challenges described by beginning teachers include poor school climate and relationships with colleagues (Harmsen et al., 2018), as well as professional identity tensions and dilemmas (Aspfors and Bondas 2013; Pillen, Beijaard, and den Brok 2013). Research has depicted coping strategies (i.e., actions taken to tolerate, amend or alter a situation) among student teachers as relying on help-seeking and developing self-efficacy (Lindqvist et al. 2017; Hascher and Hagenauer 2016; Murray-Harvey et al. 2000).

Being among more experienced colleagues has the potential of letting the new teacher establish the teacher role, but also seems to involve limitations. The experience of a newcomer has been described as lonesome (McCormack & Thomas, 2003) and without much room to influence one’s surroundings (MacPhail & Tannehill, 2012). Some studies have followed student teachers into teaching using a longitudinal design. For instance, Tynjälä and Heikkinens (2011) highlighted a number of challenges in their review on the transition into teaching and workplace learning, teacher induction, and professional development; these challenges include inadequate knowledge and skills, decreased self- efficacy, increased stress, early attrition, and the newcomer’s role and position in a work community. These authors argued that there is a lack of variation in methodological approaches to examine the transition into teaching, and the case study design dominates. Ní Chróinín and O’Sullivan (2014) used a six-year longitudinal design through all years of teacher education and the first three years of teaching. Participants reflected on their prior experiences of teacher education, and valued the applied and practical pedagogics. Overall, though, the participants were critical of teacher education, for instance describ-ing their teacher education as restrictive and pointing out that it did not encourage trying out new ideas during practicum. This can be related to the different phases described by Fuller and Bown (1975), who showed that beginning teachers go through a survival phase before entering mastery and routine phases.

Hong, Greene, and Lowery (2017) followed five participants from teacher education to teaching, and used the dialogical self theory framework to analyse changes that the participants’ identities underwent during this transition. The findings showed that most of the participants changed their I-positions either slightly or dramatically over time, and ‘they experienced disequilibrium among different I-positions during the change’ (p. 94). The social support of a school was considered important for coping with the challenges of the experienced tension among different positions.

RESEARCH PAPERS IN EDUCATION 3

Aim and research question

Previous research has shown that the teacher profession, and in particular the start of teaching, to include emotional challenges that require coping strategies. Our overall objective was to investigate the challenges and strategies used by new teachers during the transformation process from student teachers to working teachers, and thereby contribute to this field of research. We examined this transformation using qualitative short-term longitudinal data and a grounded theory methodology. Specifically, we followed individuals during their last year of teacher education and into their first year of teaching, and asked the participants to define episodes they perceived as causing challenging emotions that needed to be coped with. The research question was: How do the perceived emotional challenges and coping strategies of new teachers change over time?

Method

To examine the processes involved in the transformation from student teacher to new teacher based on their experiences and perspectives, we adopted the qualitative research methodology of constructivist grounded theory. This investigative view-point was designed to examine and conceptualise social processes (including socia-lisation and learning), experiences, meanings, and actions (Charmaz 2014), and relies on an abductive approach rather than naïve induction (Kennedy-Lewis, & Thornberg, 2018). As a theoretical framework, and in line with constructivist grounded theory (Charmaz 2014), symbolic interactionism (e.g., Blumer 1969; Charon 2007) was adopted as a flexible perspective. We assumed social reality to be constructed and part of an ever-changing process in human interaction. We examined and analysed the experiences and perspectives of new teachers (cf. Charon 2007), particularly in terms of what they perceived to be emotionally challenging situations as student teachers as well as beginning teachers, and how they dealt with those challenges. We used an interpretative framework but stayed open to possible connections to theory in line with the constructivist grounded theory approach (Charmaz 2014).

The study setting: teacher education and induction period in a Swedish context

In Sweden, teacher education is divided into pedagogical courses and subject areas and is either eight semesters (upper primary teachers, i.e. teaching pupils in grades 4–6 aged roughly 10–12,) or nine semesters (lower secondary teachers, i.e. teaching pupils in grades 7–9 aged roughly 13–15,). In studying to become level 4–6 teachers, student teachers choose to focus more in depth on the sciences, social science, or physical education. All level 4–6 student teachers study English, Swedish, and Mathematics. In studying to become a teacher of grades 7–9, the student teachers study various subjects, and receive degrees in either two or three subjects depending on their particular combination.

4 H. LINDQVIST ET AL.

All students studying to be teachers also do a practicum of 20 weeks spread over time and different courses. During their practicum, student teachers shadow and work with a supervising teacher. The longest part of the practicum occurs during the last semester. During their final practicum, the student teachers are expected to hold several lessons supervised by their supervising teacher.

When starting to teach, there is an induction phase that is defined as the first year of working as a teacher, and a mentor may be assigned. New teachers are to have as much responsibility as more experienced teachers, and the same number of lessons as other teachers.

Participants and data collection

A first wave of interviews was conducted with the participants at the beginning of their last year of teacher education, and a second wave was conducted at the end of their first year as a teacher. In between those two interviews, we collected three written self- reports from each participant over a two-year period. Thus, the data comprised inter-views and written reports as the participants progressed from student teachers to new teachers. Data collection was carried out before the Covid-19 pandemic.

In total, the study included 20 participants. The data set comprised 40 inter-views and 59 self-reports (one participant did not return the final self-report). The student teachers had undergone teacher education to become upper primary teachers or lower secondary teachers. It should be noted that three of the parti-cipants who had trained to be lower secondary student teachers started their teaching career as upper primary teachers or as teachers in adult education. The participants’ ages spanned from 22 to 56 years old (m= 27.19; sd = 9.79) at the time of the first wave of interviews. Six of the participants were male, 13 were female, and one identified as non-binary (see Table 1). The participants studied in six teacher-training programmes located at various geographic locations in Sweden.

Ethical approval for the study was given by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm (Dnr 2014/1088-31/5). The participants were informed about confidentiality and gave their informed consent, and were also informed about their right to withdraw their participation at any point in the research process. The first author, who conducted all the interviews, aimed to co-construct credibility and trustworthiness of data (Charmaz and Thornberg 2020) together with the interviewees by attentive listening, probing, and asking follow-up questions (Hiller and Diluzio 2004).

Table 1. Participants.Participants Female Male Non-binary Total

13 6 1 20Educational

Programmeupper primary school lower secondary school7 13 20

Interviews 1 2 Total20 20 40

Self-reports 1 2 3 Total20 20 19 59

RESEARCH PAPERS IN EDUCATION 5

The interview questions dealt with emotionally challenging situations encountered in teacher education and when starting to teach. Worries about starting to teach were also discussed. Participants described their perspectives and experiences of teacher education, practicum, and later, what it had been like to start to teach. The participants were asked to summarise their experiences, their education, the support they received, and to give examples of situations they experienced as emotionally challenging. In accordance with theoretical sampling (Charmaz 2014), codes, categories, and themes from the initial interviews were revisited in the second wave of interviews. The second wave of interviews also included questions about possible new experiences of emotional challenges. All interviews were recorded, transcribed verbatim, and fictional names were assigned in the transcripts and findings. The excerpts chosen for this text were translated from the Swedish originals, and we have tried to stay close in the translation to the original transcription. Most of the interviews were conducted via video link, while others were conducted face to face in various locations. The length of the first set of interviews was between 54 and 96 minutes (m = 74; sd = 12.48), and the second set of interviews ranged from 30 to 90 minutes (m = 66.95; sd = 12.62).

For the written self-reports, the participants were given open questions to write about. In the first self-report, we asked follow-up questions from the initial interview, which varied depending on issues covered in the initial interview. In the second self- report, we asked about experiences of ending their teacher education as well as any worries they might have had about starting to teach. In the third self-report, the participants were asked about what they had experienced during their first six months of teaching. The self-reports were analysed to further guide the interview questions in the second wave of interviews at the end of the first year of teaching. The word counts of the self-reports varied considerably, from 101 to 2,546 (m = 547.08; sd = 414.44).

Data analysis

A constructivist grounded theory approach guided the analysis (Charmaz 2014). Using grounded theory, we stayed close to the data and utilised grounded theory tools in a flexible manner. We conducted three types of coding (initial, focused, and theoretical coding), and started with initial coding. The transcriptions of the interviews were coded word-by-word, sentence-by-sentence, and segment-by-segment (Charmaz 2014). We labelled segments of data with names that categorised, summarised, and accounted for each piece of data. During the whole process, we constantly compared data with data, data with codes, codes with codes, and codes with new data. These comparisons helped us to sort and cluster the codes into new and fewer (but more elaborated) codes.

In focused coding, the most significant and frequent initial codes that made most analytical sense were used when going through large amounts of data (Charmaz 2014) and to guide further data collection and coding. We decided which codes best captured what we saw happening in the data and raised these codes up to tentative conceptual categories, which means that we gave these categories conceptual working definitions. An important part of this analysis was to compare and group codes, compare codes with emerging categories, compare different incidents (e.g., social situations, emotions,

6 H. LINDQVIST ET AL.

actions and social processes reported in the data), compare different participants (their beliefs, situations, actions, accounts and experiences), compare data from the same participants at different points in time, and compare the categories with each other.

In parallel with the focused coding, theoretical coding was used to examine possible relationships between our focused codes and categories to integrate them into a coherent theoretical understanding (Glaser 1978; Thornberg and Charmaz 2012). We inspected, compared, chose, and used theoretical codes as analytical tools to organise and concep-tualise our own categories. Theoretical codes refer to underlying logics that could be found in pre-existing theories about how concepts or categories are interrelated in those theories (e.g., causes, contexts, consequences, phases, basic social process, dimensions, and paired opposites). These theoretical codes were explored and compared with our data, codes, and categories. The codes we chose had be relevant and fit with the data and generated categories. In addition, memo writing was used for trying out codes, compar-ing and clustering codes, developing codes into categories, examining relationships between codes/categories, and further theorising (Charmaz 2014). The first author conducted the coding. All authors then critically scrutinised the work and discussed the codes, resulting in further elaboration and trustworthiness.

Findings

The project can be broken up into three distinct phases of data collection, which are summarised here. The first phase of the project collected data (the first wave of inter-views) during their final year of training in their teacher education. In phase 1, all participants regularly described feelings of inadequacy and doubts about their ability to start teaching. The second phase of data collection (the first self-report) began when they had completed their teacher education and worked their first six months as a teacher. All participants described an eagerness to be responsible, but also raised concerns regarding emotions that could result in stress in relation to their forthcoming professional life, and so could be described as ‘enthusiasm mingled with fear’ (as one participant put it; see page 15). The third phase of data collection (the second self-report and second interview) happened after participants had worked for a year. In this phase, participants reported a rollercoaster of emotions that led them to consider their place at the school and their work as a teacher, and also involved prioritising within their teaching duties.

Phase 1: opposite positions

The first phase focused on perceptions, emotions, and challenges that were discussed when the participants were studying their last year of teacher education. In this phase, the participants voiced concerns about their ability to become a teacher and experiences that had created doubt about their ability to teach. Here, the phrase opposite positions refers to emotions that could be conflicting, such as whether they viewed their teaching ability with doubt or trust. These opposites were part of a process of either maintaining proactive coping strategies or using reactive coping strategies for dealing with the conflict that the opposites created. The processes for coping focused on trying to either prepare to be proactive and take actions to increase trust in their abilities, or to postpone and use a reactive strategy to cope with conflicting emotions.

RESEARCH PAPERS IN EDUCATION 7

Doubt about abilityOne of the opposite positions was doubt and trust in ability to work as a teacher. Here, ‘doubt in ability’ is defined as an emotional state of questioning the school’s and one’s own ability to perform according to one’s perception of what is required to be a good teacher. Harriet experienced a general doubt about the ability of teachers to create a positive educational environment for pupils, which, according to her, resulted in her doubting her own ability to maintain classroom order.

My supervisor used the tactic of trying to be louder than the pupils when they were noisy, to compete when they were loud. And I think that just triggered the pupils to be even louder. It’s kind of becoming a negative spiral. A lot of time of the lessons was spent trying to establish calm and keeping pupils quiet in the classroom. (Harriet, interview 1)

Participants regularly described experiencing doubt, which challenged and decreased their sense of teaching ability. According to them, the main source of doubt was negative experiences during teacher education, particularly from their practicum (i.e., experiencing failures and shortcomings first-hand and/or observing the failures and shortcomings of other teachers). Another source of doubt described was teaching experiences outside their teacher training, e.g., when working as a substitute teacher while studying. Even though substitute teaching was generally discussed as positive in terms of gaining experience, having negative experiences only reinforced doubt in their ability to work as a teacher.

It would be if I didn’t establish order after some time had passed, that it would still be rowdy in the classroom after two or three months. That’s something I started to worry about. When I’ve worked as a substitute teacher it took a lot of energy. It’s just rowdy, very loud, and I feel nobody is listening to me. If that is still the case after several weeks, I’m afraid of that. And then of course that my teaching would be bad. That’s the nightmare. (Ben, interview 1)

Trust in abilityThe opposite of doubt was describing trust in their ability to work as a teacher, and some participants had acquired experiences that led them to believe in their teaching ability. Experiencing trust in teaching ability (the ability to work as a successful or effective teacher) is commonly discussed in terms of teacher efficacy beliefs in the literature, rooted in Bandura’s (1997) concept of self-efficacy. Self-efficacy has been found to be positively associated with professional commitment (Chesnut and Burley 2015), staying in a profession (Wang, Hall, and Rahimi 2015), pupil achievement, teaching effectiveness (Klassen and Tze 2014), and it has been found to be negatively correlated with teacher burnout (Wang, Hall, and Rahimi 2015). According to our analysis of participants’ experiences and perspectives, having positive experiences from teacher education and, in particular, from their practicum (i.e., experiencing their own efficiency and success) increased their trust in their teaching ability.

I have authority, I enter and own a room, they listen to me and I have good tools that I use, and I plan thoroughly and everything. (Ann, interview 1)

Ann discussed trust related to teaching, and sometimes student teachers discussed having trust in their ability in one part of the required work as a teacher but not in another. For instance, one might have trust in one’s ability to teach, but not in handling conflicts. An

8 H. LINDQVIST ET AL.

example of this splitting of trust can be seen in a quote from Claire, which showed enhanced trust in her ability to be act as a caring teacher. She positioned caring as the most important aspect of the work and essential for effective teaching.

I really think that’s part of the work, even though some people might think it’s hard. I think it’s obvious you should. It’s humans you work with and being human is more than being able to write and have certain knowledge. Simply caring about them. (Claire, interview 1)

Trust in their ability did not develop in a linear way. Student teachers trust in their ability was dependent on what they valued as important aspects of teaching and working as a teacher. Kelchtermans (1993) described subjective educational theory as a personal system of beliefs and knowledge developed over teachers’ careers. A teacher’s biographi-cal journey starts with teacher education (Skamp and Mueller 2001).

Strategies for coping

Here, we discuss strategies for coping that were found during the first phase of teacher education. The participants discussed coping in terms of how they had coped with challenges, but also how they anticipated coping in the future when they had become teachers. These strategies were described as either proactive or reactive (Blase, 1988). Proactive strategies strive to change situations and conditions, while reactive strategies are used to maintain a situation and provide protection against change.

Proactive strategiesProactive coping involved taking action to alleviate the challenges that the participants encountered. Stefan discussed observing experienced teachers struggling to maintain order in the classroom, and he had thought of a strategy to use in order to avoid experiencing the same type of problem.

Well, if you notice when the pupils feel bad, you build a better relationship, and the confidence increases. I feel that if I give my pupils confidence and trust and see them as individuals, then I don’t think they will let me down, yeah, they will respect me in another way I think. (Stefan, Interview 1)

Here, Stefan was planning to use proactive coping by trying to establish contact with pupils. Similarly, Daniel tried to use proactive coping in a situation that he perceived of as challenging, by trying to build a relationship with a pupil, but then he questioned this approach. He tried using empathy as a means to care for pupils in order to gain trust in his ability to deal with challenges.

The last time I attended a socially deprived school, it was obvious that some pupils had a tough time at home and didn’t have a role model, and then I came there being a bit younger [than most teachers, authors’ note]. They find that fun, interesting, and exciting, and they try make contact. / . . . / It’s hard to know how to treat a 14-year-old boy with dyslexia and concentration problems, who is really quite nice and calm during lessons, but often wanders off to do his own thing. How do you approach him when he tries to make contact? (Daniel, interview 1)

RESEARCH PAPERS IN EDUCATION 9

Proactive strategies mainly focused on building relationships with pupils or establishing a set of instructions and material to use for teaching, in order to avoid being over-whelmed with work as a beginning teacher. Most participants discussed both proactive and reactive strategies, and they did not rule out having to use both.

Reactive strategiesReactive coping strategies focus on uncertainty (Helsing 2007) and are based on a perception of not being able to know what might happen in every situation (here, when working as a teacher). Using a reactive coping strategy focuses on engaging in specific situations. For example, some participants thought that work would inevitably be overwhelming, and that there was no way to start other than undergoing a ‘baptism by fire’ (Weasmer and Woods 2000) or having a ‘sink or swim’ mentality (Varah, Theune, and Parker 1986).

I have an image of myself as a graduate teacher. I know that I have to put energy into having spare time when you are done, so that work isn’t all you have. But I try to adjust myself to the fact that it will be hard in the beginning. And I think that the more that image shows the work of being a teacher as hard, the easier it will be. (Lena, Interview 1)

In relation to reactive strategies, teacher education was sometimes portrayed as flawed because it was not seen as truly preparing the participants for their future work. One of the participants concluded: ‘They think the school teaches us, but no one is doing that. It’s just get out there, encounter it and handle it your own way’ (Marlene, interview 1). The reactive strategy of just doing it and handling it to the best of one’s teaching ability created expectations that the start would be challenging.

Phase 2: ‘Enthusiasm mingled with fear’

The next phase was naturally characterised by elevated nervousness, since the participants had just graduated from teacher education and were about to start their first teaching position at a school. The longitudinal nature of the data set meant that it was possible to notice that the participants reported that they still had to learn how to become a teacher, and they expressed worries and fears coupled with excited expectancy and enthusiasm. Hannes described this feeling as ‘enthusiasm mingled with fear’ (Self-report 2).

Worry and fearStarting to teach involved elevated emotions of worry and fear. It was a new beginning for the participants and feeling nervous might be expected. Although natural worries were expected when starting to teach, participants linked their worry with not having been adequately prepared in teacher education, which manifested as a reactive strategy in phase one. Harriet had recently found out that schools did not always provide term planning, and this worried her.

I feel unsure about the teaching content you should start with in the different subjects. Previously during practicum, I got the impression that there was set term planning at schools. / . . . / The teachers told me you had to decide that yourself. I find that difficult as a new teacher. I think I find that hard since I’m worried that I will miss something in my teaching. (Harriet, Self-report 2)

10 H. LINDQVIST ET AL.

The participants reported fears and worries that were specific to the tasks and were therefore more than just being nervous about starting a new position. Daniel described teachers’ working conditions as unreasonable before beginning to teach, and even though he described having teacher efficacy beliefs, he anticipated that building relationships with pupils would be difficult.

Also, to handle all the work without set routines and material, being newly qualified, I view as almost unreasonable, even though I’m structured, methodical, and ambitious. / . . . / All these things with relationships and building relationships are a huge challenge that I brood about to some extent, and that will probably be the case during my career. (Daniel, Self-report 2)

Thus, perceptions of teachers’ working conditions being too demanding or troublesome, combined with a sense of not being sufficiently prepared by teacher education to work as a teacher, created worry and fear when the participants were entering the teacher occupation.

Excited expectancy and enthusiasmWhile participants were experiencing worry and fear, feelings of excited expectancy and enthusiasm were also reported in this second phase. These emotions might also be naturally coupled with starting something that one has been preparing for during a long period of education. Emotions of excited expectancy and enthusiasm at the outset of the teaching career included eagerness and joy.

It will be fun to start working. / . . . / I know it’s a tough and often thankless job (I noticed when I worked), but it’s also a very rewarding and fun job. Being with young people and helping them develop their mathematical and scientific thinking, that’s awesome. (Pia, Self-report 2)

According to Pia in the excerpt above, the idea of being around pupils and expanding their knowledge was a source of enthusiasm. She seemed to perceive that these joyful experiences and emotions of working as a teacher would outweigh the troublesome and negative aspects of the work. Feelings of excited expectancy involved moving forward, knowing that it would be tough at the beginning, and still looking forward to starting. Similarly, Paul described anticipating the beginning to be tough, but said that he was still looking forward to starting.

That means you have to work really hard at the beginning, and I’m aware that it will be a tough start with a lot of overtime hours in order to do the best possible job. However, I very much look forward to starting to work. (Paul, Self-report 2)

A few of the participants referred specifically to their experiences of working as a substitute teacher as a source of feeling prepared for the profession.

Strategies for copingHere, we discuss strategies for coping that were found during the second phase, after having completed teacher education. The participants discussed coping in terms of how they had managed previous challenges in their teacher training (mainly during their practicum), but also how they anticipated coping as teachers.

Satisficing. In this phase, the only distinctly described strategy for coping was satisficing. Satisficing is finding a way of accepting that an action is perhaps not the best imaginable option, but the best possible option in the context of the resources available (Le Maistre

RESEARCH PAPERS IN EDUCATION 11

and Paré 2010). The participants commonly discussed satisficing in terms of setting appropriate levels of engagement and not setting their expectations of their own perfor-mances too high.

Will I be good enough? What’s expected of me? What if something goes wrong? I make an effort to think about starting to work as continued learning time. I’m new, I don’t have to be perfect – and no one expects me to be (I hope). / . . . / And if I’m going to make a mistake I will, and I will learn from that. Like all teachers I feel a responsibility to have all the answers, and always act in the right way in all situations. (Lena, Self-report 2)

Satisficing also involved finding the right level of engagement with the pupils; neither enmeshed and unrealistically engaged (i.e., unhealthy and limitless caring) nor detached and disengaged (i.e., leaving them all to themselves) in their interactions and relation-ships with pupils.

Phase 3: rollercoaster of emotions

The next phase included the participants’ first year of work. They discussed the full range of emotions that the first year involved, from not having any emotional chal-lenges during the first six months to experiencing many emotional challenges six months later in the subsequent interview. This rollercoaster of emotions is a common feature of the third phase.

Joy and uncertaintyThe emotions described during this phase involved feeling joy after having started work, and in trying to establish the work role that they had envisioned. Participants commonly described emotions of joy as a result of actually doing what they had aimed to do. Even so, they also experienced uncertainty. Anders experienced his start as meaningful in comparison to previous work, and he described every day as being exciting but also involving a certain amount of uncertainty, which he valued. In addition, he found that the work was more socially orientated than he had expected. Learning and teaching were not the main priorities for his colleagues. Anders reported admiration for his colleagues and the varied nature of his working day that involved a rollercoaster of emotions.

For example, a boy often comes up to me, he’s usually waiting for me to greet me and give me a hug. Then you’re happy and then you kid around with someone who’s playing soccer or something like that. Then there might be someone who’s sad and there are conflicts and stuff during the day, then you get a bit down, or feel a bit angry, or a bit wound up, or something like that. (Anders, Interview 2)

Here, Anders describes joy as well as uncertainty. In contrast, Harriet reported that she felt uncertain when setting out to do what she envisioned among pupils, giving social support and being a caring teacher. She became aware of having to be cautious about feeling for the pupils too much.

Harriet: There are some pupils you have better contact with, and that might be the ones who have more of a need to talk about something that has happened at home or with friends. And some of these pupils look for contact a lot. And then they talk about stuff that happened at home, or things that make them feel bad in various ways. That affected me. I thought that,

12 H. LINDQVIST ET AL.

you know, you get pretty close with some pupils. And you establish a good relationship, which is good and bad. Because it takes time to learn how to shut off, or to know how to talk to the student without taking everything in. That’s hard for me.

Interviewer: In what way?

Harriet: The things they feel, the things they think are hard, I feel for them too much. (Interview 2)

Anders and Harriet experienced joy at having an important place in a pupil’s school day, and tried to establish relationships with their pupils, and when doing so experienced having to be cautious about their position, in order not to experience overwhelming emotions.

Disillusion and exhilarationOther participants experienced disillusion and exhilaration when they started to teach. Ben felt disillusioned at the beginning.

I notice that they don’t care about what I have to say, some of them. It’s not important what I have to say. They could just sit and talk with each other instead, because that’s more important. And that, how should I put this, it makes me sad actually. / . . . / It makes me sad. / . . . / Because I notice that when my colleagues talk to them it’s dead quiet. I don’t know if they do it with a lot of involvement, but it’s something they do. (Ben, Interview 2)

Alice experienced positive emotions when she continued to work with adult learners despite her recent degree in teaching lower secondary pupils. ‘When writing this I can’t think of any challenges. All in all, emotions have been positive.’ (Alice, self-report 3.) After a while, Alice decided to try working with the age group she had studied to work with and found the experience overwhelming. She felt disillusioned from the start.

Situations when you feel you don’t have control. There are, like, conflicts with pupils where I felt I had to put my foot down. But they don’t feel I’m fair and then you don’t really reach each other, instead they are very angry. And it’s hard to accept they’re angry with you. But now I feel I can distance myself a little. Today a student said, ‘Alice do you know why we hate your lessons?’ / . . . / No, he said ‘that’s why everyone hates you’. (Alice, Interview 2).

Other narratives were like those recounted by Alice and Ben and involved either feeling disillusioned straight away or a shift from exhilaration to disillusion.

Strategies for copingHere, we discuss strategies for coping that were found and used during the third phase when the participants were starting to teach. They discussed coping in terms of what they did to manage various challenges as beginning teachers.

Turnover/attrition. Like Alice, Disa did not experience strain at the beginning. ‘I don’t feel like I have had that much strain’ (Disa, self-report 3). However, after having completed a full year of teaching, Disa considered giving up teaching altogether and concluded that no one could be expected to work under the conditions she was facing.

Disa: The way I feel right now, I feel like I won’t be a teacher for much longer.

Interviewer: How come you feel that way?

RESEARCH PAPERS IN EDUCATION 13

Disa: It’s not as plain as it should be. / . . . / We’re supposed to be the best at this and that, we have to develop our special needs knowledge, our conflict management. It’s too much, I can’t do it. I’m ambitious so when I can’t do it, I get anxious. And I could turn it down, but not what is asked of me. Half-way through the term I started forgetting things, I had extreme migraines, I got stress symptoms, and I couldn’t sleep. But now I just let it bounce off me. That’s the way it works. But the question is how long I can manage, until I lose my patience. Well yeah, that’s a bit sad thinking about the joy you felt when it worked.

Interviewer: So, you think about whether this is the right kind of work for you?

Disa: Exactly, is this the right line of work for anyone, that’s what I think. How many is it? The fifth teacher left today. (Disa, Interview 2)

Some teachers seemingly adopted attrition and turnover as coping strategies. Turnover refers to changing schools, while attrition refers to leaving the profession altogether. To cope, and to avoid experiencing migraines, sleeping problems, and other complications, Disa reported that she thought about if it was worth the trouble. Similarly, Marlene found herself in challenging situations and considered giving up. However, she fought through the challenges and the feeling of wanting to give up, and this resulted in changes.

I wanted to resign several times. I wasn’t happy with going to work, since I had anxiety and panic attacks every time I had a lesson. When I left for the day, I rushed to the car to get away as fast as I could. The pupils want me to stay. They’re safe with me. A lot of people are curious about how I worked to establish a calm working atmosphere in the classroom where pupils can work and feel safe, all pupils regardless of their diagnosis. The pupils are anxious. They need guidance, help, and someone who’s always there for them. Sometimes I say that you are a mother, a teacher, and a friend to them. It’s worth it after everything I went through in February, it’s worth it. Now I love being there. (Marlene, Self-report 3)

Over the course of a year, several of the participants started working at another school, mainly due to the challenges they experienced. At the moment, Sweden has a shortage of teachers (Swedish National Agency for Education 2019), and there is commonly a stable work market for teachers, with many secure and open positions. This availability makes teacher turnover easy in the sense that there are usually lots of positions to apply for.

Prioritising. According to the participants, prioritising the tasks that they felt were their responsibility was a way of coping with the emotional rollercoaster as a beginning teacher. It has been shown that student teachers use responsibility reduction as a way to cope with challenges in teacher education (Lindqvist 2019), but it was harder to reduce responsibility as a beginning teacher. The participants felt responsibility and demands, and thus the need to prioritise in order to cope.

Daniel: During the term I have lowered the demands I placed on myself. They were pretty high, or very high, in the middle and now there has been some kind of survival involved in what I’ve done. Well, you don’t have the time, and after a while you don’t have the strength. Soon there’s the Christmas holidays, but you have to prioritise, prioritise in some way. / . . . / And your subject teaching, first and foremost planning and structure, has been a shortcoming.

Interviewer: How do you feel when you think about that?

Daniel: Well, pretty frustrating. / . . . / It feels like, I’m a teacher, I want to teach. (Interview 2)

14 H. LINDQVIST ET AL.

Stefan also found the number of tasks that a teacher had to carry out to be challenging. Like other participants, he discovered that there was little guidance available from more experienced colleagues, because their prioritisations differed.

There’s a lot to sort out. I hadn’t really understood that, like all the administration and documentation. Maybe I lost that a bit in the beginning. Everything from writing reports to individual plans. It’s also very different if you ask teachers what they are supposed to do. Some think they should do a lot, and some nothing at all. Then it’s very hard to know what to do. What’s expected from me, which report should I write? / . . . / When there’s a lot to sort out it becomes kind of messy. It’s hard to do anything at times. You really have to know what to prioritise, what’s important in your work. I’ve put a lot into building relationships with pupils. That was what I started with when I started working, focusing a lot on that part and getting to know the pupils. (Stefan, Interview 2)

Stefan prioritised relationships, which was his aim when he started to teach, according to his understanding of the teaching profession (cf. Kelchtermans 1993). In his view, establishing relationships was a way to cope with the numerous challenges he encoun-tered during his first year as a teacher.

A grounded theory of phases when starting to teach

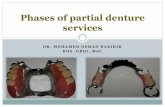

The transition process of a teaching student becoming a new teacher is characterised by a variety of emotions, and these differences are reflected in the different phases of the study (see Figure 1). The participants experienced both positive emotions and emotions commonly depicted as negative (Koenen et al. 2019), and they also encountered opposite positions in each of the three phases. Phase 1 was characterised by the opposites trusting versus doubting teaching ability, phase 2 by excited expectancy versus worry/fear, and phase 3 by joyful exhilaration versus disillusion/uncertainty.

During the various phases, the participants described how they thought they would be able to cope with the challenges they encountered. Our grounded theory encompasses a process of either tuning in to or phasing out from the teaching profession depending on how each new teacher resolved the challenges and tensions between the opposite posi-tions in each phase. Tuning in refers to adjusting oneself and one’s working conditions to fit into the teaching profession and is linked to adaptive coping and predominantly positive emotions. Phasing out refers to a process of detaching oneself from the teaching profession as a result of experiencing predominantly negative emotions and failing to resolve the challenges and tensions in each phase.

The participants used various coping strategies that they found appropriate for dealing with the common challenges during whichever phase they were in. The coping strategies changed over time to deal with the different challenges experienced. In the first phase, proactive strategies helped student teachers alleviate the challenges and increased trust in their abilities, while reactive strategies fuelled a sense of helplessness and doubt in their ability. In the second phase, satisficing helped the new teachers adjust their expectations, demands, and performance to a realistic and ‘good enough’ level. By contrast, unrealis-tically high engagement or being detached and disengaged pushed them closer to phasing out. In the third phase, new teachers experienced an emotional rollercoaster at the beginning of their teaching career and relied primarily on one of two coping strategies. The strategy of prioritising helped the novice teachers to get through the rollercoaster of

RESEARCH PAPERS IN EDUCATION 15

emotions by making their teaching work manageable and decreasing the intensity of emotions (tuning in). The strategy of turnover and attrition, on the other hand, provided a way of getting away from the rollercoaster. Turnover (leaving the current school) and attrition (leaving the professional altogether) can be understood as coping by avoiding the situation, and therefore represent different degrees of phasing out.

The transition process throughout the three phases was produced by an interplay among personal, behavioural, and situational/contextual influences (cf. Bandura 1997) and was therefore partly uncertain and unpredictable. For example, having experienced joy during one phase did not necessarily mean that the participants thought this emotion would be part of their work again when encountering more strenuous emotions or uncertainty. Nevertheless, in relation to the longitudinal analysis, it should be noted that participants who expressed doubt about their ability during their last year of teacher education more often discussed turnover or attrition as a coping strategy.

Discussion

Becoming a teacher is an emotional journey. This contribution is our attempt to answer the research question: How do the perceived emotional challenges and coping strategies of new teachers change over time?

Our findings suggest that some student teachers graduate from teacher education with doubts about their teaching ability (phase one). Increasing and developing student teachers’ efficacy beliefs should be an educational goal in teacher education, as this self- concept has been shown to be important for job satisfaction and teaching effectiveness, among other things (Klassen and Tze 2014; Wang, Hall, and Rahimi 2015). It has also been shown that teacher efficacy beliefs among student teachers influence later thoughts of attrition (Hascher and Hagenauer 2016). Teacher efficacy beliefs are not universal or chronological, as they sometimes appear in literature. A significant contribution of this study is that self-efficacy beliefs in phase one relate to different aspects of what a teacher is responsible for. In accordance with social cognitive theory on self-efficacy (Bandura 1997), student teachers could experience high teacher efficacy when teaching a subject,

Figure 1. Phases There seems to be a space in the third Phase in columns of Teacher emotions and Strategies to cope.

16 H. LINDQVIST ET AL.

but low teacher efficacy when grading or establishing fruitful relationships with pupils. This difference addresses emotional challenges that are social and performative (cf. Zembylas 2007), and these challenges can give rise to either a phasing out or tuning in processes.

The start of a career as a teacher has been shown to be troublesome (Le Maistre and Paré 2010; Veenman 1984), and various coping strategies use both cognitive and beha-vioural efforts aimed at reducing and overcoming challenges. The second and third phases of the transition process reported in this study corroborate that starting to teach is a highly emotional journey, with elevated concerns and challenges that the new teachers have to cope with. An interesting finding is the use of satisficing as a strategy (Le Maistre and Paré 2010), which the new teachers (phase 2) reported that they used as their primary coping strategy. The ambition was to find a way to accept that an action taken was the best possible option in the context of the resources available, as a way of tuning in and adapting to the new, real-life working conditions. The strategy of satisficing is in line with the notion that challenges occur when there is a gap between resources and demands, as described by Lazarus and Folkman (1984).

Another notable finding relates to a recent call to look at the career choices of new teachers with an extended view of why new teachers quit teaching (Cochran-Smith et al. 2012). In our findings, as corroborated by Hascher and Hagenauer’s (2016) findings, teacher efficacy beliefs and emotions of self-doubt were linked to thoughts of attrition. More importantly, we found that teacher efficacy beliefs and self-doubt were associated and aligned with the new teachers’ subjective educational theory of beliefs and knowl-edge. That means that intense emotions in the rollercoaster of emotions (phase 3) were related to the subjective educational beliefs that they carried with them into teaching.

In trying to influence future teachers and educate resilient teachers, it could be valuable to consider that the emotional journey creates disequilibrium of identity (Ní Chróinín and O’Sullivan 2014). Social support is often depicted as a solution to this problem. The strategy of having a critical friend (which has been tried in medical education, Dahlgren et al. 2006) could be valuable for teachers at all stages. In fact, Dahlgren et al. showed that being a critical friend was more fruitful even than having one. This would mean that new teachers should be able to be a critical friend for a colleague and not always only by on the receiving end of support, which might help in the tuning in process to the teacher profession. The problem is that not all schools incorporate a method for social support. Studies even point to other teachers creating emotional challenges for both old and new colleagues (Lindqvist et al. 2019; Löfgren and Karlsson 2016).

Limitations

Some limitations of the study need to be acknowledged. The analysis was based on data from interviews with new teachers and written accounts over a period of one and a half years. Thus, no observational or performative data are included, and we rely on the narratives of the participants. It is possible that the participants may have portrayed the emotionally challenging situations in a way that was favourable to them (although the participants reported weaknesses, fears, and problems they encountered). The reported research relies on the experiences and perspectives of the participants. Furthermore,

RESEARCH PAPERS IN EDUCATION 17

grounded theory does not end in a fixed result, but could be open to modification through further data collection and theoretical sampling (Charmaz 2014; Glaser 1978). The differences in the lengths of the self-reports are also important to consider as a limitation. Some self-reports were short and did not provide a great deal of information; even so, the self-reports built up a substantial amount of rich data.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Funding

This research was supported by a grant from Vetenskapsrådet [Grant number 721-2013-2310].

Notes on contributors

Henrik Lindqvist, PhD, is senior lecturer at Education at the Department of Behavioural Sciences and Learning at Linkoping University in Sweden. His research areas are (1) student teachers learning from, and coping with, emotionally challenging situations in teacher education, and (2) special education.

Maria Weurlander, PhD, is associate professor and senior lecturer in Higher Education at the Department of Education at Stockholm University in Sweden. Her main research focuses are on student learning in higher education, and student teachers’ and medical students’ experiences of and dealing with emotionally challenging situations during their training.

Annika Wernerson, PhD, MD, is professor in renal- and transplantation science at the depart- ment of Clinical Science, Intervention and Technology (CLINTEC) at Karolinska Institutet, where she also is Dean of higher education. Her research areas in medical education focus on learning in higher education and medical students’ and student teachers ́ experiences of and dealing with emotionally challenging situations during their training and early professional life.

Robert Thornberg, PhD, is Professor of Education at the Department of Behavioural Sciences and Learning at Linkoping University in Sweden. His main focuses are on (a) bullying and peer victimization among children and adolescents in school settings, (b) values education, rules, and social interactions in everyday school life, and (c) student teachers and medical students’ experi- ences of and dealing with emotionally challenging situations during their training

ORCID

Henrik Lindqvist http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3215-7411Maria Weurlander http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3027-514XAnnika Wernerson http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2792-0010Robert Thornberg http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9233-3862

References

Admiraal, W. F., A. J. F. Korthagen, and T. Wubbels. 2000. “Effects of Student Teachers’ Coping Behaviour.” British Journal of Educational Psychology 70 (1): 33–52. doi:10.1348/ 000709900157958.

18 H. LINDQVIST ET AL.

Aspfors, J., and T. Bondas. 2013. “Caring about Caring: Newly Qualified Teachers’ Experiences of Their Relationships within the School Community.” Teachers and Teaching 19 (3): 243–259. doi:10.1080/13540602.2012.754158.

Bandura, A. 1997. Self-efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York, NY: Freeman and Company.Blase, J. 1988. “The Micropolitics of the School: The Everyday Political Orientation of Teachers

toward Open School Principals.” Educational Administration Quarterly 25 (4): 377–407. doi:10.1177/0013161X89025004005.

Blumer, H. 1969. Symbolic Interactionism. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.Caspersen, J., and F. D. Raaen. 2014. “Novice Teachers and How They Cope.” Teachers and

Teaching 20 (2): 189–211. doi:10.1080/13540602.2013.848570.Chaaban, Y., and X. Du. 2017. “Novice Teachers’ Job Satisfaction and Coping Strategies:

Overcoming Contextual Challenges at Qatari Government Schools.” Teaching and Teacher Education 67: 340–350. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2017.07.002.

Charmaz, K. 2014. Constructing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.Charmaz, K., and R. Thornberg. 2020. “The Pursuit of Quality in Grounded Theory.” Qualitative

Research in Psychology. Advance online publication. 10.1080/14780887.2020.1780357.Charon, J. M. 2007. Symbolic Interactionism: An Introduction, an Interpretation, an Integration.

9th edn ed. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.Chen, J. 2016. “Understanding Teacher Emotions: The Development of a Teacher Emotion

Inventory.” Teaching and Teacher Education 55: 68–77. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2016.01.001.Chesnut, S. R., and H. Burley. 2015. “Self-efficacy as A Predictor of Commitment to the Teaching

Profession: A Meta-analysis.” Educational Research Review 15: 1–16. doi:10.1016/j. edurev.2015.02.001.

Cochran-Smith, M., P. McQuillan, K. Mitchell, D. G. Terrell, J. Barnatt, L. D’Souza, A. M. Gleeson, K. Shakman, K. Lam, and A. M. Gleeson. 2012. “A Longitudinal Study of Teaching Practice and Early Career Decisions: A Cautionary Tale.” American Educational Research Journal 49 (5): 844–880. doi:10.3102/0002831211431006.

Dahlgren, L. O., B. E. Eriksson, H. Gyllenhammar, M. Korkeila, A. Sääf-Rothoff, A. Wernerson, and A. Seeberger. 2006. “To Be and to Have a Critical Friend in Medical Teaching.” Medical Education 40 (1): 72–78. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02349.x.

Flores, M. A., and C. Day. 2006. “Contexts Which Shape and Reshape New Teachers’ Identities: A Multi-perspective Study.” Teaching and Teacher Education 22 (2): 219–232. doi:10.1016/j. tate.2005.09.002.

Fuller, F. F., and O. H. Bown. 1975. “Becoming a Teacher.” In Teacher Education, the 74th Yearbook of the National Society for the Study of Education, edited by K. Ryan, 25–52, Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Garciá-Carmona, M., M. D. Marín, and R. Aguayo. 2019. “Burnout Syndrome in Secondary School Teachers: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.” Social Psychology of Education 22 (1): 189–208. doi:10.1007/s11218-018-9471-9.

Glaser, B. 1978. Theoretical Sensitivity: Advances in the Methodology of Grounded Theory. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.

Harmsen, R., Helms-Lorenz, M., Maulana, R., & Van Veen, K. (2018).“The relationship between beginning teachers’ stress causes, stress responses, teaching behaviour and attrition.“Teachers and Teaching 24 (6): 626–643.

Hascher, T., and G. Hagenauer. 2016. “Openness to Theory and Its Importance for Pre-service Teachers’ Self-efficacy, Emotions, and Classroom Behaviour in the Teaching Practicum.” International Journal of Educational Research 77: 15–25. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2016.02.003.

Helsing, D. 2007. “Regarding Uncertainty in Teachers and Teaching.” Teaching and Teacher Education 23 (8): 1317–1333. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2006.06.007.

Hiller, H. H., and L. Diluzio. 2004. “The Interviewee and the Research Interview: Analysing a Neglected Dimension in Research.” Crsa/rcsa 41: 1–26. doi:10.1111/j.1755-618X.2004. tb02167.x.

RESEARCH PAPERS IN EDUCATION 19

Hong, J., B. Greene, and J. Lowery. 2017. “Multiple Dimensions of Teacher Identity Development from Pre-service to Early Years of Teaching: A Longitudinal Study.” Journal of Education for Teaching 43 (1): 84–98. doi:10.1080/02607476.2017.1251111.

Izard, C. E. 2010. “The Many Meanings/aspects of Emotion: Definitions, Functions, Activation, and Regulation.” Emotion Review 2 (4): 363–370. doi:10.1177/1754073910374661.

Kelchtermans, G. 1993. “Getting the Story, Understanding the Lives: From Career Stories to Teachers’ Professional Development.” Teaching and Teacher Education 9 (5–6): 443–456. doi:10.1016/0742-051X(93)90029-G.

Kelchtermans, G., and K. Ballet. 2002. “Micropolitical Literacy: Reconstructing a Neglected Dimension in Teacher Development.” International Journal of Educational Research 37 (8): 755–767. doi:10.1016/S0883-0355(03)00069-7.

Kennedy-Lewis, Brianna, L., and R. Thornberg. 2018. “Induction, Deduction, Abduction.” In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Collection, edited by U. Flick, 49–64, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Klassen, R. M., and V. M. C. Tze. 2014. “Teachers’ Self-efficacy, Personality, and Teaching Effectiveness: A Meta-analysis.” Educational Research Review 12: 59–76. doi:10.1016/j. edurev.2014.06.001.

Koenen, A. K., E. Vervoort, G. Kelchtermans, K. Verschueren, and J. L. Spilt. 2019. “Teachers’ Daily Negative Emotions in Interactions with Individual Students in Special Education.” Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders 27 (1): 37–51. doi:10.1177/ 1063426617739579.

Kyriacou, C. 2001. “Teacher Stress: Directions for Future Research.” Educational Review 53 (1): 27–36. doi:10.1080/00131910120033628.

Lazarus, S. R., and S. Folkman. 1984. Stress, Appraisal and Coping. Springer.Le Maistre, C., and A. Paré. 2010. “Whatever It Takes: How Beginning Teachers Learn to Survive.”

Teaching and Teacher Education 26 (3): 559–564. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2009.06.016.Lindqvist, H. 2019. “Student Teachers’ Use of Strategies to Cope with Emotionally Challenging

Situations in Teacher Education.” Journal of Education for Teaching 45 (5): 540–552. doi:10.1080/02607476.2019.1674565.

Lindqvist, H., M. Weurlander, A. Wernerson, and R. Thornberg. 2017. “Resolving Feelings of Professional Inadequacy: Student Teachers’ Coping with Distressful Situations.” Teaching and Teacher Education 64: 270–279. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2017.02.019.

Lindqvist, H., M. Weurlander, A. Wernerson, and R. Thornberg (2019). Conflicts Viewed through the Micro-political Lens: Beginning Teachers’ Coping with Emotionally Challenging Situations. Research Papers in Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2019.1633559

Löfgren, H., and M. Karlsson. 2016. “Emotional Aspects of Teacher Collegiality: A Narrative Approach.” Teaching and Teacher Education 60: 270–280. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2016.08.022.

MacPhail, A., & Tannehill, D. (2012).“Helping pre-service and beginning teachers examine and reframe assumptions about themselves as teachers and change agents: “Who is going to listen to you anyway?.“ Quest 64: 299–312.

Madigan, D. J., and L. E. Kim. 2021a. “Does Teacher Burnout Affect Students? A Systematic Review of Its Association with Academic Achievement and Student-reported Outcomes.” International Journal of Educational Research 105: 101714. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101714.

Madigan, D. J., and L. E. Kim. 2021b. “Towards an Understanding of Teacher Attrition: A Meta- analysis of Burnout, Job Satisfaction, and Teachers’ Intentions to Quit.” Teaching and Teacher Education 105: 103425. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2021.103425.

McCormack, A. N. N., & Thomas, K. (2003).“ Is survival enough? Induction experiences of beginning teachers within a New South Wales context.“ Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education 31: 125–138.

Murray-Harvey, R., T. Slee, P. Lawson, H. M. J, Silins, G. Banfield, and A. Russell. 2000. “Under Stress: The Concerns and Coping Strategies of Teacher Education Students.” European Journal of Teacher Education 23 (1): 19–35. doi:10.1080/713667267.

20 H. LINDQVIST ET AL.

Ní Chróinín, D., and M. O’Sullivan. 2014. “From Initial Teacher Education through Induction and Beyond: A Longitudinal Study of Primary Teacher Beliefs.” Irish Educational Studies 33 (4): 451–466. doi:10.1080/03323315.2014.984387.

Oatley, K., and P. N. Johnson-Laird. 2014. “Cognitive Approaches to Emotions.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 18 (3): 134–140. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2013.12.004.

Pillen, M., D. Beijaard, and P. den Brok. 2013. “Tensions in Beginning Teachers’ Professional Identity Development, Accompanying Feelings and Coping Strategies.” European Journal of Teacher Education 36 (3): 240–260. doi:10.1080/02619768.2012.696192.

Sharplin, E., O’Neill, M., & Chapman, A. (2011).“Coping strategies for adaptation to new teacher appointments: Intervention for retention.“ Teaching and Teacher Education 27 (1): 136–146.

Skamp, K., and A. Mueller. 2001. “Student Teachers’ Conceptions about Effective Primary Science Teaching: A Longitudinal Study.” International Journal of Science Education 23 (4): 331–351. doi:10.1080/09500690119248.

Swedish National Agency for Education. 2019. “Prognosis of Teachers 2019, Presentation of the Assignment to Produce Prognosis of the Need of Pre-school Teachers and Different Teacher Categories (Stockholm, Sweden).” Report number 5.1.3-2018:1500. https://www.skolverket.se/ download/18.32744c6816e745fc5c3a88/1575886956787/pdf5394.pdf .

Thornberg, R., and K. Charmaz. 2012. “Grounded Theory.” In Qualitative Research: An Introduction to Methods and Designs, edited by S. D. Lapan, M. Quartaroli, and F. Reimer, 41–67, San Francisco, CA: John Wiley/Jossey-Bass.

Travers, C. 2017. “Current Knowledge on the Nature, Prevalence, Sources and Potential Impact of Teacher Stress.” In Educator Stress: An Occupational Health Perspective, edited by T. M. McIntyre, S. E. McIntyre, and D. J. Francis, 23–54, Cham: Springer.

Tynjälä, P., and H. L. Heikkinen. 2011. “Beginning Teachers’ Transition from Pre-service Education to Working Life.” Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft 14 (1): 11–33. doi:10.1007/ s11618-011-0175-6.

Varah, L. J., W. S. Theune, and L. Parker. 1986. “Beginning Teachers: Sink or Swim?” Journal of Teacher Education 37 (1): 30–34. doi:10.1177/002248718603700107.

Veenman, S. 1984. “Perceived Problems of Beginning Teachers.” Review of Educational Research 54 (2): 143–178. doi:10.3102/00346543054002143.

Wang, H., N. C. Hall, and S. Rahimi. 2015. “Self-efficacy and Causal Attributions in Teachers: Effects on Burnout, Job Satisfaction, Illness, and Quitting Intentions.” Teaching and Teacher Education 47: 120–130. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2014.12.005.

Weasmer, J., and A. M. Woods. 2000. “Preventing Baptism by Fire: Fostering Growth in Newteachers.” The Clearing House 73 (3): 171–173. doi:10.1080/00098650009600941.

Zembylas, M. 2007. “Theory and Methodology in Researching Emotions in Education.” International Journal of Research and Method in Education 30 (1): 57–72. doi:10.1080/ 17437270701207785.

RESEARCH PAPERS IN EDUCATION 21