Tessier D., Smith N., Tzioumakis Y., Sarrazin P., Quested E., Sarazzin P., Papaioannou A., Digelidis...

Transcript of Tessier D., Smith N., Tzioumakis Y., Sarrazin P., Quested E., Sarazzin P., Papaioannou A., Digelidis...

This article was downloaded by: [Damien Damien]On: 21 October 2013, At: 11:49Publisher: Taylor & FrancisInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registeredoffice: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

International Journal of Sport andExercise PsychologyPublication details, including instructions for authors andsubscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rijs20

Comparing the objective motivationalclimate created by grassroots soccercoaches in England, Greece and FranceDamien Tessiera, Nathan Smithb, Yannis Tzioumakisc, EleanorQuestedb, Philippe Sarrazina, Athanasios Papaioannouc, NikolaosDigelidisc & Joan L. Dudab

a University Grenoble Alpes, Laboratory “Sport et EnvironnementSocial”, F-38041 Grenoble, Franceb School of Sport and Exercise Sciences, The University ofBirmingham, Birmingham, UKc Department of Physical Education and Sport Sciences, Universityof Thessaly, Thessaly, GreecePublished online: 18 Oct 2013.

To cite this article: Damien Tessier, Nathan Smith, Yannis Tzioumakis, Eleanor Quested, PhilippeSarrazin, Athanasios Papaioannou, Nikolaos Digelidis & Joan L. Duda , International Journal ofSport and Exercise Psychology (2013): Comparing the objective motivational climate createdby grassroots soccer coaches in England, Greece and France, International Journal of Sport andExercise Psychology, DOI: 10.1080/1612197X.2013.831259

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2013.831259

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the“Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis,our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as tothe accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinionsand views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors,and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Contentshould not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sourcesof information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims,proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever orhowsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arisingout of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Anysubstantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms &Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dam

ien

Dam

ien]

at 1

1:49

21

Oct

ober

201

3

Comparing the objective motivational climate created by grassrootssoccer coaches in England, Greece and France

Damien Tessiera*, Nathan Smithb, Yannis Tzioumakisc, Eleanor Questedb,Philippe Sarrazina, Athanasios Papaioannouc, Nikolaos Digelidisc and Joan L. Dudab

aUniversity Grenoble Alpes, Laboratory “Sport et Environnement Social”, F-38041 Grenoble, France;bSchool of Sport and Exercise Sciences, The University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK; cDepartmentof Physical Education and Sport Sciences, University of Thessaly, Thessaly, Greece

(Received 15 January 2013; accepted 29 July 2013)

The coach-created motivational climate is a key determinant of athletes’ welfare and degree ofoptimal functioning when taking part in sport. The purpose of this study, grounded in a self-determination theory and achievement goal theory-integrated framework, was to investigateto what extent the differences in the objective motivational climate created by the coachesinvolved in the European-wide “Promoting Adolescent Physical Activity” project were afunction of their country affiliation (i.e. England, Greece and France). Fifty-seven coaches(55 men and 2 women) from England, Greece and France were selected to take part in thestudy. Each coach was videotaped during one complete training session using a digitalcamcorder and microphone. The recently developed Multidimensional MotivationalClimate Observation System was used to code the coach-created motivational climate interms of need-supportive and need-thwarting environmental dimensions. Results showedthat (1) coaches were observed to emphasise on a more need-supportive environment thana need-thwarting one (i.e. 69.9% and 30.1% of the whole behaviours coded, respectively)and (2) although coaches’ interpersonal styles varied significantly across countries, thegeneral pattern of the coach-created environment observed in the three countries had asimilar profile.

Keywords: motivational climate; self-determination theory; achievement goal theory;coaching; soccer

Central to the European-wide Promoting Adolescent Physical Activity (PAPA) project (www.projectpapa.org) is a consideration of how to increase youth athletes’ self-determined motiv-ation and engagement for physical activity (PA). The motivational climate—also termed associal and environmental influences or situational factors—represents an assumed keydeterminant of such responses in young athletes. Within this global environment, the coach,in particular, is an influential and significant figure likely to shape young sport participants’well-being and the quality of their participation (Duda & Balaguer, 2007). The vast majorityof research that has studied the coach-created motivational climate in youth sport has relied onplayers’ self-reported perceptions of the environment. To date, limited research has been con-ducted to examine the objective or actual motivational climate created by coaches in youthsport.

© 2013 International Society of Sport Psychology

*Corresponding author. Email: [email protected]

International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 2013http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2013.831259

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dam

ien

Dam

ien]

at 1

1:49

21

Oct

ober

201

3

Motivational climate in the achievement goal theory framework

The term motivational climate was initially introduced by Ames (1984, 1992), Ames, Ames, andFelker (1977), and Ames and Archer (1988) to refer to the subjective interpretation of the featuresof the environment that were likely to encourage self or other reference competence construal(Ames, 1992). Conceptualised in an achievement goal theory (AGT) (Nicholls, 1989) framework,two types of motivational climate were defined: Task-involving (or mastery) climates are charac-terised by features such as success being evaluated in a self-referent manner, reinforcement ofindividual progress and a sense that everyone has an important role within the group; or ego-involving (or performance) climates are distinguished by features such as judgement of progressbased on normative standards, encouragement to outperform others and public recognition ofsuccess and failure (Ames, 1992).

In the sport domain, the literature consistently shows that the perceptions of a task-involvingmotivational climate are positively associated with numerous adaptive and desirable conse-quences for the participation and development of sport performers. In contrast, when participantsperceive an ego-involving motivational climate, maladaptive beliefs and negative patterns of be-haviour are often displayed (see Amorose, 2007; Duda, 2001, 2005; Duda & Balaguer, 2007;Keegan, Harwood, Spray, & Lavallee, 2011, for reviews). For example, perceptions of a task-involving climate have been positively associated with perceived competence as well as enjoy-ment, intrinsic interest, satisfaction, higher moral standards in sports (e.g. respects for therules, officials and opposition), more autonomous reasons for sport engagement and adaptivelearning strategies whilst playing and training. Conversely, a perceived ego-involving motiva-tional climate has been negatively linked to positively affect moral norms/behaviour and posi-tively related to anxiety, worry, distress and dissatisfaction with the team and coach. In themajority of these AGT-grounded studies, no significant associations have emerged between per-ceptions of ego-involving climate and athletes’ reported competence level and strategy use.

Recent research has recognised that dimensions of the social environment emphasised in self-determination theory (SDT) (Deci & Ryan, 2002) also are relevant to athletes’ responses. SDTpoints to other features of the climate which hold motivational significance.

Motivational climate in the self-determination theory framework

Over the last 25 years, SDT (Deci & Ryan, 2000) has been established as a heuristic theoreticalframework to study individuals’motivated behaviours in several life contexts, including sport set-tings (Ryan & Deci, 2002, 2007). One of the central tenets of the SDT is that the influence ofsocial/environmental factors—such as the coach’s interpersonal style—on individual’s motiv-ation is not direct, but mediated by the degree of fulfilment or frustration of the fundamentalbasic psychological needs for competence, autonomy and relatedness (Ryan & Deci, 2000).Autonomy refers to the degree to which individuals feel volitional and responsible for theirown behaviour and, therefore, represents a need for an inner endorsement of one’s actions(Ryan, 1995). The need for competence—also relevant in AGT, as previously discussed—con-cerns the degree to which individuals feel effective in their on-going interactions with thesocial environment and experience opportunities in which to express their capabilities (Ryan &Deci, 2002). Finally, the need for relatedness is defined as the extent to which individuals feela secure sense of belongingness and connectedness to others in their social environment (Baume-ister & Leary, 1995; Ryan, 1995). Satisfaction of these psychological needs is assumed to directlyenhance psychological and physical well-being in various life domains (Baard, Deci, & Ryan,2004; Reeve & Jang, 2006; Ryan, Patrick, Deci, & Williams, 2008). In sports settings, it isbelieved that any action on the part of the coach that positively affects an athlete’s perception

2 D. Tessier et al.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dam

ien

Dam

ien]

at 1

1:49

21

Oct

ober

201

3

of competence, autonomy or relatedness will ultimately help to facilitate or promote more self-determined forms of motivation and engagement. Antithetically, those behaviours that thwartor inhibit the satisfaction of the three needs are likely to promote more controlled forms of motiv-ation and be associated with more maladaptive cognitive, affective and behavioural responses. Asa consequence, a central research question from a coaching effectiveness perspective is to deter-mine which dimensions of a coach’s interpersonal style and associated behaviours are positivelyor negatively related to the satisfaction and thwarting of these needs.

Previous studies have conceptualised a leader interpersonal style along a continuum rangingfrom highly controlling to highly autonomy-supportive (e.g. Deci, Schwartz, Sheinman, & Ryan,1981; see Reeve, 2002, for a review). In a conceptual paper, Mageau and Vallerand (2003)reviewed the behaviours that represent an autonomy-supportive interpersonal style. Specifically,they argued that autonomy-supportive coaches (a) provide choice to their athletes within specificlimits and rules; (b) provide athletes with a meaningful rationale for the activities, limits and rules;(c) ask about and acknowledge the athletes’ feelings; (d) provide opportunities for athletes to takeinitiative and act independently; (e) provide non-controlling performance feedback; (f) avoidovert control, guilt inducing criticisms, and controlling statements and limit their use of tangiblerewards and (g) minimise behaviours that promote ego-involvement. Following this conceptualpaper, a number of empirical studies (Adie, Duda, & Ntoumanis, 2008, 2012; Smith, Ntoumanis,& Duda, 2007) have shown that perceptions of coach autonomy support is predictive of need sat-isfaction, which in turn is significantly associated with indices of well- and ill-being (e.g. subjec-tive vitality, emotional and physical exhaustion).

More recently, studies (Reeve, Jang, Carrell, Jeon, & Barsh, 2004; Reinboth, Duda, & Ntou-manis, 2004; Skinner & Belmont, 1993; Skinner & Edge, 2002; Tessier, Sarrazin, & Ntoumanis,2010) have expanded upon this unidimensional continuum by examining characteristics of theenvironment that are likely to contribute directly to the satisfaction of each of the three psycho-logical needs. In this line of work, researchers typically label dimensions of the environment as“autonomy support”, “structure” and “interpersonal involvement”, which are believed to nourishthe needs for autonomy, competence and relatedness, respectively.

Autonomy support refers to interpersonal style adopted by a person in a position of authoritywho shows respect, allows freedom of expression and action, and encourages subordinates toattend to, accept, and value their inner states, preferences and desires (Deci & Ryan, 1987). Asargued above, the provision of choice and meaningful rationale from coaches, the support ofplayer volition and the acknowledgement of the players’ perspective are symbolic examples ofautonomy-supportive behaviours (Mageau & Vallerand, 2003). The conceptual opposite of auton-omy support is control. Controlling coaches display coercive, pressuring or authoritarian (e.g. byushering commands and deadlines) behaviours, which are likely to induce a change in an athletes’perceived locus of causality from internal to external. As a consequence, players’ need for auton-omy is threatened because they tend to experience themselves as “pawns” in the hands of thecoach (Skinner & Edge, 2002).

Structure describes the extent to which a social context is structured, predictable, contingent andconsistent (Skinner & Edge, 2002). One key feature of structure is the communication of clear andunderstandable guidelines and expectations (Farkas & Grolnick, 2010; Jang, Reeve, & Deci, 2010;Sierens, Vansteenkiste, Goossens, Soenens, & Dochy, 2009) so that players feel capable to startengaging in the learning task. More specifically, instructional behaviour can be characterised inthree categories: (a) present clear, understandable, explicit and detailed directions; (b) offer a pro-gramme of action to guide players’ ongoing activity and (c) offer constructive feedback on howplayers can gain control over valued outcomes (Jang et al., 2010). Players’ outcomes (e.g. satisfac-tion of need for competence, self-determined motivation and engagement) are enhanced when thecomponents of structure are presented in an autonomy-supportive way (Deci & Ryan, 1991;

International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 3

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dam

ien

Dam

ien]

at 1

1:49

21

Oct

ober

201

3

Jang et al., 2010; Sierens et al., 2009). The conceptual opposite of structure is chaos. When coachesare confusing or contradictory, fail to communicate clear expectations and directions and ask foroutcomes without articulating a means of attainment, coaches are deemed to be chaotic (Janget al., 2010).

Finally, interpersonal involvement (or relatedness support) refers to coaches creating oppor-tunities for individuals to feel related to others and that they belong or are cared for when theyinteract within a social environment that offers affection, warmth, care and nurturance (Skinner& Edge, 2002). In sport settings, when coaches are sympathetic, warm and affectionate withtheir players, and when they dedicate psychological resources, such as time, energy and affec-tion (Deci & Ryan, 1991; Reeve et al., 2004), they tend to nurture their players’ relatedness andencourage more self-determined forms of motivation. The conceptual opposite of interpersonalinvolvement is hostility (or relatedness thwarting). When coaches are hostile or neglectful,players experience themselves as unlovable and the context as untrustworthy (Skinner &Edge, 2002). Relative to autonomy support and structure, very few studies have examined relat-edness-supportive and relatedness-thwarting features of the coach-created environment in sportor PA settings.

Several studies have revealed the benefits of a need-supportive coaching style (including oneor more dimensions among autonomy-support, structure, interpersonal involvement and task-involved), compared to a need-thwarting one (including one or more dimensions amongcontrol, chaos, hostility and ego-involved), on players’ needs satisfaction, motivation, emotionand well-being. For example, Quested and Duda (2010) revealed that perceptions of dance tea-chers’ autonomy-support and task-involving dance environments positively predicted dancers’basic psychological needs satisfaction, which in turn was positively associated with positiveaffect. Reinboth et al. (2004) showed that coaches who were autonomy-supportive (i.e. providedathletes with choices and options), competence-supportive (i.e. task-involving) and relatedness-supportive (i.e. providing social support), influenced positively adolescent soccer and cricketplayers’ perceptions of autonomy, competence and relatedness, which in turn influenced posi-tively their subjective vitality, intrinsic interest in sport and physical well-being. Gagné, Ryan,and Bargmann (2003) used multilevel analysis to show that when gymnasts’ needs were satisfiedduring practice, which would partly be a function of the environment created by the coach, gym-nasts experienced increases in positive affect, self-esteem and subjective vitality. Althoughempirical evidence supports the manifold benefits of need-supportive behaviours, it has beenrepeatedly suggested that coaches consistently rely on a more controlling interpersonal style(Mageau & Vallerand, 2003).

Objective motivational climate

The vast majority of research on the concomitants of the coach-created climate, drawing fromeither or both AGT and SDT, typically focuses on the athletes’ perceptions of their coaches’ be-haviour, rather than objectively assessing behaviours of the coach. This is consistent with theassumptions of social cognitive approaches to motivation (Pintrich, 2003; Roberts, 2001), accord-ing to which, actions of the coach in and of themselves are relatively less important than how anathlete perceives, interprets and evaluates a coach’s behaviours (Horn, 2002). However, Keeganet al. (2011) claimed that this argument would be more convincing if subjective perceptions of theenvironment led to more accurate predictions, or contributed more to the empirical understandingof the studied phenomenon than objective assessments of the environment. To date, no study hasexplicitly compared the “perceived” versus “actual” coach-created climate in terms of predictiveaccuracy (Keegan et al., 2011). Therefore, this issue remains an open question strengthening theneed to examine the motivational climate from an objective point of view.

4 D. Tessier et al.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dam

ien

Dam

ien]

at 1

1:49

21

Oct

ober

201

3

In addition, as claimed by Haerens et al. (2013), there are a number of other pertinent reasonsto design and conduct observational studies of coaches’ interpersonal styles. First, observationalapproaches can provide new information about the validity of the construal “motivationalclimate”. One of the relevant research questions about this construal is to know whether it is agroup-level or an individual-level variable. The motivational climate is probably both; i.e. amulti-faceted construct that necessitates triangulating individual-level measures with group-level measures to encompass all its complexities. It could be argued that the observationalapproach is particularly well suited to address the features of the motivational climate as experi-enced by the collective as ratings are made of all leader behaviours directed at individual athletes,groups of athletes and the team overall.

Second, observation studies have high ecological validity as real trainings are observed andcoaches’ real-life need-supportive and need-thwarting behaviours are coded. For instance, anobservational study in the physical education domain showed that teachers use more controllingmotivational strategies (e.g. rewards and punishment) than autonomy-supportive ones (e.g.emphasising relevance of the task; Tessier, Sarrazin, & Ntoumanis, 2008). Thus in the sportcontext, the observational rating of an entire training session permits a greater understandingof the evolution of the potent frequency and intensity of each interpersonal style dimension(i.e. autonomy support, control, task-involving, ego-involving, etc.) during the discrete aspectsof a usual training period (e.g. warm-up, learning skill tasks and games).

Finally, the development of a coding system is important because it sets the stage for interven-tion studies which involve training coaches to adopt a more need-supportive interpersonal style.The effectiveness of such coach training programmes—like the Empowering Coaching™ pro-gramme (see Duda, 2013) which was implemented in the PAPA project—could then be evaluatedby examining whether a change in the observed coach-created motivational environment can benoticed.

Currently, a number of systems exist for observing coach’s behaviour (Darst, Zakrajsek, &Mancini, 1989), with probably the best known and most widely used being the Coach BehaviourAssessment System (Smith, Smoll, & Hunt, 1977) and the Arizona State University ObservationInstrument (Lacy & Darst, 1985). However, these instruments are based on an inductive and pri-marily behaviourist approach subdividing coach behaviour into multiple behavioural categories(e.g. instruction, question, praise, specific feedback and modelling). Such an approach is notapt to reveal to what extent the coach-created climate is need-supportive or need thwarting.

A limited number of studies have attempted to develop and implement observational ratingsystems to examine need-supportive dimensions of teacher or coach behaviour. Notable studiesinclude the work carried out by Tessier et al. (2008) who developed an observational instrumentto code autonomy-supportive behaviours in physical education settings, Jang et al. (2010) whorated structure and autonomy-supportive behaviours in general education contexts and theneed-supportive rating schemes used by Reeve et al. (2004) and Tessier et al. (2010) in educationand physical education, respectively. In a unique study in sport, Boyce, Gano-Overway, andCampbell (2009) developed and used an observational checklist to assess task- and ego-involvingfeatures of the coach-created motivational climate, and how the ratings of independent observersrelated to coaches’ and athletes’ perceptions of the created environment.

One of the limitations of these instruments is the relation assumed between need-supportiveand need-thwarting dimensions/behaviours. Either these instruments did not assess need-thwart-ing dimensions—only need-supportive ones—leading to an implicit consideration that low-needsatisfaction scores are evidence of both lack of need satisfaction and psychological need thwart-ing, without distinguishing between the two constructs; or they measured need-supportive andneed-thwarting dimensions of the environment on a bipolar scale, considering that these two con-structs are opposite (i.e. the two ends of the same continuum). Recently, Bartholomew,

International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 5

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dam

ien

Dam

ien]

at 1

1:49

21

Oct

ober

201

3

Ntoumanis, Ryan, and Thøgersen-Ntoumani (2011) showed that athletes’ perceptions of psycho-logical need thwarting and psychological need satisfaction were weakly and negatively corre-lated, strengthening the idea that the two constructs are independent. Consequently, it ispossible that sometimes need satisfaction and need thwarting co-occur. That is, within thesame coaching environment, mixed patterns of positive and negative behaviours can be exhibitedand emphasised. Thus, to include both need-supportive and need-thwarting dimensions in theobservational instrument is necessary to analyse more comprehensively the objective coach-created motivational climate. In addition, in order to examine more holistically the motivationalclimate, it is a valid point to adopt a multidimensional approach integrating the complimentarytheoretical frameworks found in AGT and SDT (see Duda et al., 2013).

Present study

The purpose of this study, grounded in a conceptualisation of the motivational climate that entailsan integration of SDT and AGT (Duda et al., 2013), was to investigate to what extent the differ-ences in the objective motivational climate created by the coaches involved in the PAPA projectwere a function of their country of residence (i.e. England, Greece and France). To do so, anobservational coding system was developed and employed within the PAPA project (Smith,Tessier, & Tzioumakis, in preparation). Considering the limitations outlined above, a systemthat integrated key features of the environment emphasised in AGT and SDT was developedallowing for a multidimensional assessment of the coach-created environment in sport. Using asample of 57 coaches, the aims were (1) to examine the objective motivational climate createdby coaches across countries and (2) to test whether the differences between coaches were a func-tion of their country. Concerning aim 1, it was hypothesised that coaches will display more oncontrolling behaviours than autonomy-supportive ones, as was the case for physical educationteachers (Tessier et al., 2008). Pertaining to the contribution of the other interpersonal styledimensions, we did not have prior hypotheses, because of the scarcity of empirical studies exam-ining this question. As for aim 2, we expected to find no difference as a function of the coaches’country, meaning there would be more or less homogeneity across the whole group (i.e. 57coaches from England, France and Greece). Yet, given the small size of the sample, we wereopen to the possibility that individual differences could emerge and this could be a function ofeither the country variable or assigned group variable.

Method

Participants

Fifty-seven coaches (55 men and 2 women; Mage = 37.6, SDage = 9.9; Mexperience = 7.1 yearsof coaching, SDexperience = 5.2) from England (i.e. 18), Greece (i.e. 22) and France (i.e. 17)were selected to take part in the study. Twelve coaches had no coaching qualification, 22 had afederal certificate (i.e. 13 had a federal certificate 1, and 9 had a federal certificate 2 or 3), 18 pos-sessed a qualification delivered by the UEFA—Union of European Football Association—(i.e. 3had the UEFA coaching qualification level C, 14 had the UEFA B and 1 had the UEFA A) and 5possessed an academic coaching qualification or were physical education teachers. All of thecoaches’ trained players aged between 10 and 15 years old (Mteamage = 11.92, SD = 1.45).Among the coaches from England (i.e. 18 men), 9 coaches trained U11 teams (i.e. 10–11 yearsold players) and 9 trained U13 teams (i.e. 12–13 years old players). Among the coaches fromGreece (i.e. 22 men), 10 trained U11s, 5 trained U13s and 7 trained U15s (i.e. 14–15 years oldplayers). Among the coaches from France (i.e. 15 men and 2 women), 7 trained U11s, 8trained U13s and 2 trained U15 teams.

6 D. Tessier et al.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dam

ien

Dam

ien]

at 1

1:49

21

Oct

ober

201

3

Procedure

Each coach was videotaped during one complete training session using a digital camcorder andmicrophone. The camcorder was focused permanently on the coach, but had a large viewingangle, which enabled the recording of the context (i.e. the players’ attitudes and behaviours).All teams were visited at least once before the observed training session to be informed of thecourse of the filming. This procedure is expected to reduce reactivity effects associated withthe use of the camcorder, by allowing the coach and the players to familiarise themselves withthe presence of a researcher. At this initial meeting, coaches and parents of each of the playerson the team were given information letters and consent forms that included details of thepurpose of the research. In accordance with each of the University’s ethical review procedures,the coaches were asked to provide opt-in consent for the filming to take place, and parentswere given the opportunity to opt their child out of the study if they wished. Furthermore, atthis part of the study, and as Van der Mars (1989) suggests, no reference was made to thecoaches about the motivational climate they create. Rather, they were told that they weretaking part in a study related to the motivation and well-being of their players, and that theresearchers were interested in recording what they did during training sessions. This was a pre-cautionary measure taken to prevent a Hawthorne effect (Adair, Sharpe, & Huynh, 1989).

On an average, the observed training sessions were 77 minutes long (SD = 15.8 minutes), andranged from 42 minutes to 92 minutes. Each training session was split into quarters that variedbetween 10 minutes 30 seconds and 23 minutes depending on the length of the overall session.Adopting this analytical approach allowed observers to rate all of the recorded footage.1 For eachquarter, the observers rated each of the seven environmental dimensions included in the measure.

Measure

As part of the PAPA project, the Multidimensional Motivational Climate Observation System(MMCOS) has been developed and is currently in the process of being validated (Smith et al.,in preparation). The MCCOS examines the motivational climate from an integrative perspective,drawing from frameworks within both AGT (Nicholls, 1989) and SDT (Deci & Ryan, 1985,2000). The MMCOS allows researchers to rate seven motivationally relevant environmentaldimensions: autonomy supportive, controlling, task-involving, ego-involving, relatedness sup-portive, relatedness thwarting and structure (for definitions, see first paragraph). To helpinform the coders’ ratings they were given a list of behavioural strategies. These were not indi-vidually rated, but based upon the literature these strategies are believed to be indicative of theseven facets of the environment. For example, a coach can emphasise autonomy support by “pro-viding meaningful choices”; be controlling by “using extrinsic rewards”; be task involving by“recognising effort and improvement”; be ego involving by “emphasising inferior or superiorability”; be relatedness supportive by “adopting a warm communication style”; be relatednessthwarting by “showing a lack of care and concern for players” and finally emphasise structureby “providing guidance throughout exercises”. When generating their ratings, coders wereasked to rate the extent to which the strategies employed by the coach reflected each of theseven environment dimensions. Each dimension was rated using a potency scale ranging from0 (i.e. not at all) to 3 (i.e. strong potency). To aid the coders’ decision-making and facilitatehigh levels of agreement, they were given a marking scheme.2

Coding reliability

Prior to the coding sessions, the lead researchers devoted to the observational work in the PAPAproject in each country, coded the same six 5-minute clips in the English language, two times at

International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 7

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dam

ien

Dam

ien]

at 1

1:49

21

Oct

ober

201

3

least one week apart (as recommended by Van der Mars, 1989), to ensure a good intra- and inter-rater reliability across countries (Tzioumakis et al., 2012). Following recommendations made byBakeman and Gottman (1997), inter- and intra-rater reliabilities were estimated using Cohen’skappa coefficients. Results of this observational pilot study revealed a good reliability betweenthe three coders (i.e. weighted kappa of Cohen > .70) (Tzioumakis et al., 2012). In addition, thehigh degree of consistency across cultures helps to ensure the lead researchers are viewing theclimate similarly using the developed measurement instrument. As a result of this initial work,the lead observational researchers in each country were able to implement the coder-training pro-gramme in a consistent and reliable manner. In each country, two or three researchers familiarwith the tenets and constructs embedded in both SDT and AGT were selected to rate theobserved footage. Each coder underwent an intensive coder-training programme, based uponprinciples specific to AGT and SDT that included, around 6 hours of PowerPoint presentations,seminar discussions and collaborative coding. Following training, coders were asked to rate inde-pendently a number of clips. These were compared to each other, and to the ratings made by thelead researchers in each of the participating countries. Once the inter-rater agreement reached asatisfactory level, coders were asked to independently rate the 57 videoed training sessions. As aconsequence, inter-rater reliability, calculated using Cohen’s kappa, surpassed the acceptable levelof the agreement (Fleiss, 1981). The coefficient was estimated by comparing the ratings of two(UK) or three raters (France and Greece), for each of the 4 quarters across all 57 of the observedtraining sessions. The analysis revealed good inter-rater reliabilities pertaining to the coders fromeach of the three countries. The average kappa coefficient in the UK, Greece and France was .77(between .60 and .90), .92 (between .87 and .95) and .74 (between .66 and .86), respectively. Asthe inter-rater reliability was satisfactory, we averaged the scores of raters into one overall scorefor each environmental dimension per quarter.

Data analyses

Because the within-coach variance (i.e. the variability between the measure occasions) and thebetween-coach variance (i.e. the difference between the coaches in the use of each objectiveclimate dimension) are not independent, hierarchical linear modelling (Bryk & Raudenbush,1992)—also called multilevel modelling—was chosen to perform the analysis. The hierarchicallyorganised structure of the data, with the four occasions of measures at Level 1 and the coaches atLevel 2, has two main implications that are not properly taken into account by ordinary least-squares (OLS) models (Kenny, Kashy, & Bolger, 1998). First, OLS models do not separate thedifferent levels of analysis. Therefore, whilst using OLS models, the data have to be aggregatedat the highest level of the hierarchy (i.e. averaging the data of the four occasions of measure),which can lead to the aggregation bias (Robinson, 1950). Second, coaches in this study are arandom sample of a population of coaches, and their effects have to be treated as randomrather than fixed. This means that we are interested in estimating variances rather than means,and that we have to partial out true variance from sampling variation. Because OLS models con-sider every effect as fixed, these effects are usually overestimated since sampling variation is nottaken into account.

For these reasons, hierarchical linear models were preferred because they have been specifi-cally conceived to take into account hierarchically structured data. Multilevel analyses wereperformed using Predictive Analytics SoftWare (PASW; previously SPSS) Version 18.0.02.(2009). The first step was to use a fully unconditional two-level hierarchical model to partitionthe variance of each climate dimension into between-coach and within-coach components.This model is unconditional because the variance components are not predicted by any variable.Variance estimates produced by the unconditional model are used to calculate the intraclass

8 D. Tessier et al.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dam

ien

Dam

ien]

at 1

1:49

21

Oct

ober

201

3

correlation, an index of the proportion of total variance in the dependent variable (i.e. the sevenclimate dimensions) attributable to Level 1 (i.e. within-coach level). The intraclass correlationwas .53 for autonomy support, .44 for control, .63 for task involving, .32 for ego involving,.56 for relatedness support, .45 for relatedness thwarting and .64 for structure. This means thata substantial part of the variance of motivational climate dimensions (i.e. 53%, 44%, 63%,32%, 56%, 45% and 64%, respectively) was between coaches. This nonzero intraclass correlationprovides justification for using hierarchical models to answer our research question.

Thus, we proceeded in using multilevel analyses to examine the data. The goal was to deter-mine whether differences between the objective motivational climate created by the grassrootssoccer coaches were related to the country of origin (i.e. to be from England, Greece orFrance). Hypotheses were tested by constructing a series of hierarchical linear models. First,model 1 was assessed, by including the background information (i.e. coaches’ age, years ofexperience in coaching, level of qualification and players’ age) as control variables, into an uncon-ditional or an empty model. Next, to test the major hypothesis per se, we assessed model 2 byadding the country variable. As the predictor was a nominal variable with three modalities (i.e.France, England and Greece), we assessed it twice: first, by fixing the modality of France at 0in order to test whether the other two modalities (i.e. England and Greece) were significantlydifferent from the one fixed, and a second by fixing the modality of England at 0 in order totest whether Greece differed significantly from the latter.

Following Rasbash et al.’s (2000) recommendations, to appreciate the efficacy of model 1compared to the empty model, and model 2 compared to model 1, we assessed the significantimprovement in the fit statistic. We calculated the deviance statistic of the model (i.e. Δ−2 logL/df), which follows a χ2 distribution at k degree of freedom, k representing the number ofadding parameters to estimate. When χ2 is significant at p < .05, this indicates a greater improve-ment in the fit statistic compared to the previous model.

Results

To investigate the aims of the present study, the results of a descriptive examination (i.e. mean,correlation and percentage) of the usual objective motivational climate will be first presented.Then, the results of the multilevel analysis, testing the effects of country on each climate dimen-sion, will be described.

Descriptive examination of the usual objective motivational climate created by the coachesacross the three countries

Table 1 shows that half of the values for the variables labelled as “need-supportive” (i.e. auton-omy support and relatedness support) are below the theoretical mean of the scale (i.e. 1.5), andcan be interpreted as being low in potency. Similarly, all of the scores of the variables labelledas “need thwarting” are below the theoretical mean (i.e. control, ego involving and relatednessthwarting) and can also be considered as low in potency. Only the scores of task involving(1.56) and the structure (1.77) are above the mean albeit only slightly so. As one wouldexpect, most of the need-supportive variables (autonomy supportive, task-involving and related-ness supportive) are positively correlated with one another, and negatively correlated or uncorre-lated with the need-thwarting variables, controlling and relatedness thwarting. However, thestructure and task-involving dimension are positively correlated with the ego-involving dimen-sion. The strongest correlations are between structure and task-involving variables, andbetween the control and relatedness-thwarting dimensions (i.e. .71 for both).

International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 9

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dam

ien

Dam

ien]

at 1

1:49

21

Oct

ober

201

3

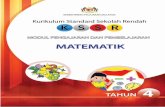

As given in Figure 1, the 57 coaches were observed to emphasise a more need-supportive (i.e.47.49% is obtained in summing autonomy supportive, task-involving and relatedness supportive)than need thwarting (i.e. 30.1% is obtained in summing control, ego involving and relatednessthwarting) motivational climate, whilst structure was the dimension most potently emphasised bythe coaches (i.e. 22.41%). Task involving was the most potent positive (need supportive) dimension(18.58%), followed by relatedness support (15.52%) and then autonomy support (11.82%). Thecontrolling dimension was the most potent need-thwarting behavioural dimension (16.77%), fol-lowed by relatedness thwarting (9.57%), and then ego-involving behaviours (6.26%). Althoughsome mean level differences exist between countries, the general pattern of the coaches createdclimate appears to be the same across countries. Some variations seem to exist between countries.

Are there differences between coaches as a function of their country?

Table 2 shows that change from the empty models to model 1 (i.e. the addition of the control vari-ables) yielded no significant decrease in the deviance statistic of the models (–2 log L; Δ < 9.48, for4 df). Although, in some cases, coaches’ age and experience significantly predicted the observed

Table 1. Inter-correlations between all variables.

Variables M (SD)a 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

1. Autonomy support 0.86 (0.63) –2. Control 1.27 (0.51) −.22 –3. Task-involving 1.56 (0.56) .52*** −.16 –4. Ego-involving 0.49 (0.42) .27* .34* .43** –5. Relatedness support 1.34 (0.68) .59*** −.33* .73*** .31* –6. Relatedness thwart 0.63 (0.54) −.32* .71*** −.35** .20 −.50*** –7. Structure 1.77 (0.49) .59*** .07 .71*** .33* .65*** −.21 –

aThe scale contains three points.*p < .05.**p < .01.***p < .001.

Figure 1. Repartition in percentage of the seven environmental dimensions of the coach-created objectivemotivational climate.Notes: Auto. sup, autonomy support; task, task involving; related sup., relatedness support; ego, ego invol-ving; related. thwart., relatedness thwarting.

10 D. Tessier et al.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dam

ien

Dam

ien]

at 1

1:49

21

Oct

ober

201

3

Table 2. Results of the multilevel models for prediction of coaches’ need-support behaviours.

Empty model Model 1 Model 2

Variable Estimate SE Estimate SE Estimate SE Estimate SE

Autonomy supportFixed effect

Intercept 0.86*** 0.08 −0.68 0.80 −1.01 0.67 −0.06 0.69Age 0.03* 0.01 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00Experience −0.03 0.02 −0.00 0.02 −0.00 0.02Qualification 0.03 0.04 0.03 0.05 0.03 0.05Players’ age 0.05 0.05 0.09 0.05 0.09 0.05

Country UKa 0.95*** 0.20 0 0FRb 0 0 −0.95*** 0.20GR 0.45* 0.20 −0.49* 0.22

Random effectWCV 0.28*** 0.03 0.28*** 0.03 0.28*** 0.03 0.28*** 0.03BCV 0.32*** 0.07 0.28*** 0.07 0.17*** 0.05 0.17** 0.05−2 Log L 453.81 446.70 426.78

Task-involvingFixed effect

Intercept 1.56*** 0.07 0.95 0.27 0.69 0.57 1.44* 0.58Age 0.02 0.01 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00Experience −0.03 0.02 −0.01 0.01 −0.01 0.01Qualification 0.06 0.03 −0.001 0.03 −0.01 0.03Players’ age −0.01 0.05 0.02 0.03 0.02 0.03

Country UKa 0.75*** 0.17 0 0FRb 0 0 −0.75*** 0.17GR 0.81*** 0.16 0.07 0.19

Random effectWCV 0.16*** 0.02 0.16*** 0.02 0.16*** 0.17 0.16*** 0.17BCV 0.27*** 0.06 0.23*** 0.05 0.13** 0.03 0.13** 0.03−2 Log L 347.69 340.84 314.53

Relatedness supportFixed effect

Intercept 1.34*** 0.09 1.25 0.86 0.79 0.58 2.12** 0.59Age 0.02 0.01 −0.01 0.00 −0.01 0.00Experience −0.02 0.02 0.02 0.01 0.02 0.01Qualification 0.08 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04 0.04Players’ age −0.07 0.06 −0.02 0.04 −0.02 0.04

Country UKa 1.32*** 0.17 0 0FRb 0 0 −1.32*** 0.17GR 0.84*** 0.16 −0.48* 0.19

Random effectWCV 0.29*** 0.03 0.28*** 0.03 0.28*** 0.03 0.28*** 0.03BCV 0.37** 0.08 0.32*** 0.07 0.11** 0.03 0.11** 0.03−2 Log L 467.26 460.25 416.43

StructureFixed effect

Intercept 1.78*** 0.07 1.40*** 0.62 1.12* 0.47 1.95*** 0.48Age 0.02* 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00Experience −0.03* 0.01 −0.01 0.01 −0.01 0.01Qualification 0.00 0.03 −0.02 0.03 −0.02 0.03Players’ age −0.01 0.04 0.02 0.03 0.02 0.03

Country UKa 0.83*** 0.14 0 0FRb 0 0 −0.83*** 0.14

(Continued)

International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 11

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dam

ien

Dam

ien]

at 1

1:49

21

Oct

ober

201

3

coaching environment, compared to the empty model, model 1 did not improve significantly the fitstatistic. In contrast, the change from models 1 to 2 (i.e. the addition of the predictor country)yielded strong reductions in between-coaches variances for the four need-supportive dimensions.Actually, the deviances statistic of themodels (–2 log L) strongly decreased (Δ = 17.98; 28.83; 47.3;29.18 for 1 df, for autonomy support, task involving, relatedness support and structure, respect-ively). These were substantial and corresponded to significant improvements in the fits statistic(p < .001), meaning that “country” significantly enhanced the prediction of the observed auton-omy-support, task-involving, relatedness-support and structure-behavioural dimensions. Morespecifically, results of the model 2 showed that coaches from England and Greece more potentlyemphasised autonomy supportive, task-involving, relatedness supportive and structured featuresof the climate compared to coaches from France, and that the coaches fromGreece emphasised sig-nificantly less autonomy supportive, relatedness supportive and structured features of the environ-ment than the coaches fromEngland. For the task-involving dimension of the environment, coachesfrom Greece were not significantly different from the coaches of England.

Table 3 shows that change from the empty model, to model 1, yielded no significant decreasein the deviance statistic of the models (–2 log L). The addition of the control variables into theempty models did not significantly improve the fit statistic. Moreover, the change from models1 to 2 yielded strong reductions in between-coaches variances and a significant decrease in thedeviance statistic of the models (–2 log L), only for ego-involving environments (Δ = 20.02 for1 df). This means that the variable country entered in the model significantly enhanced the pre-diction of the ego-involving dimension. More specifically, results of model 2 showed that coachesfrom England and Greece emphasised significantly and more potently on ego-involving environ-ments than the coaches from France, but the coaches from Greece were not significantly differentfrom the coaches of England.

Discussion

Using a multidimensional assessment grounded in an integration of the social environmentaldimensions emphasised with AGT and SDT frameworks (Duda et al., 2013), the purpose ofthis study was to investigate the extent to which country differences were evident in the objectivemotivational climate created by grassroots soccer coaches. Two aims guided this work: (1) toexamine the observed mean values for the targeted dimensions of the objective motivationalclimate created by coaches and (2) to test whether the country could explain differencesbetween coaches. Results are discussed in light of these two aims.

Table 2. Continued.

Empty model Model 1 Model 2

Variable Estimate SE Estimate SE Estimate SE Estimate SE

GR 0.55*** 0.14 −0.28* 0.16Random effect

WCV 0.12*** 0.01 0.12*** 0.01 0.12*** 0.01 0.12*** 0.01BCV 0.21*** 0.04 0.18*** 0.03 0.09*** 0.02 0.09*** 0.02−2 Log L 280.18 272.64 242.42

Notes: WCV, within-coach variance; BCV, between-coach variance; UK, United Kingdom; FR, France; GR, Greece.aThe variance of the English coaches is fixed at 0.bThe variance of the French coaches is fixed at 0.*p < .05.**p < .01.***p < .001.

12 D. Tessier et al.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dam

ien

Dam

ien]

at 1

1:49

21

Oct

ober

201

3

Table 3. Results of the multilevel models for prediction of coaches’ need-thwarting behaviours.

Empty model Model 1 Model 2

Variable Estimate SE Estimate SE Estimate SE Estimate SE

ControlFixed effect

Intercept 1.27*** 0.07 0.53 0.27 0.54 0.65 0.50 0.66Age −0.01 0.01 −0.01 0.01 −0.01 0.01Experience 0.01 0.02 0.01 0.02 0.01 0.02Qualification −0.04 0.04 −0.05 0.04 −0.05 0.04Players’ age 0.08 0.04 0.08 0.04 0.08 0.04

Country UKa −0.04 0.19 0 0FRb 0 0 0.04 0.20GR 0.08 0.19 0.12 0.22

Random effectW CV 0.24*** 0.03 0.24*** 0.03 0.24*** 0.03 0.24*** 0.03BCV 0.19*** 0.05 0.17*** 0.04 0.17*** 0.04 0.17*** 0.04−2 Log L 404.33 398.56 398.21

Ego-involvingFixed effect

Intercept 0.49*** 0.06 0.03 0.55 −0.13 0.46 0.35 0.47Age 0.01 0.01 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.01Experience −0.3* 0.01 −0.02 0.01 −0.02 0.01Qualification 0.00 0.03 −0.05 0.03 −0.05 0.03Players’ age 0.03 0.04 0.04 0.03 0.04 0.03

Country UKa 0.48** 0.13 0 0FRb 0 0 −0.48** 0.13GR 0.57*** 0.13 0.09 0.15

Random effectWCV 0.25*** 0.02 0.22*** 0.02 0.22*** 0.02 0.22*** 0.02BCV 0.12*** 0.03 0.10** 0.03 0.06** 0.02 0.06** 0.02−2 Log L 372.43 366.24 346.22

Relatedness thwartingFixed effect

Intercept 0.63*** 0.03 0.37 0.66 0.48 0.66 0.16 0.66Age −0.02* 0.01 −0.01 0.01 −0.01 0.01Experience 0.02 0.02 0.01 0.02 0.01 0.02Qualification −0.03 0.03 −0.04 0.04 −0.04 0.04Players’ age 0.08 0.05 0.07 0.04 0.07 0.04

Country UKa −0.32 0.19 0 0FRb 0 0 0.32 0.19GR −0.05 0.19 0.26 0.22

Random effectWCV 0.27*** 0.03 0.27*** 0.03 0.27*** 0.03 0.27*** 0.03BCV 0.22*** 0.05 0.17*** 0.04 0.16*** 0.05 0.16*** 0.05−2 Log L 428.21 418.80 416.01

Notes: WCV, within-coach variance; BCV, between-coach variance; UK, United Kingdom; FR, France; GR, Greece.aThe variance of the British coaches is fixed at 0.bThe variance of the French coaches is fixed at 0.*p < .05.**p < .01.***p < .001.

International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 13

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dam

ien

Dam

ien]

at 1

1:49

21

Oct

ober

201

3

Descriptive examination of the coach-created motivational climate

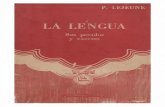

Overall, as shown in Figures 1 and 2, coaches were observed to create a more need-supportive(i.e. 69.9% is obtained in summing autonomy-support, task-involving, relatedness support andstructure) than a need-thwarting (i.e. 30.1% is obtained in summing control, ego involving andrelatedness thwart) motivational environment. One point for discussion is the potential forshared variance between task-involving dimensions of the environment and structure, whichcould artificially inflate the need-supportive environment score. However, even when structure(i.e. 22.41%) is removed, the need-supportive score is still higher (i.e. 47.49%) compared tothe need-thwarting one. Whilst this trend is obvious for the environmental dimensions deemedto be particularly relevant to the needs for competence (i.e. task involving represents 19.69%of the whole exhibited behaviours, whilst ego-involving represents only 6.15%), and the needfor relatedness (i.e. relatedness support represents 16.95%, whereas relatedness thwarting rep-resents 7.91%), it is not so clear for the need for autonomy (i.e. autonomy support represents10.85% versus 16.04% for control). In accordance with our hypothesis, and consistent with theprojections of Mageau and Vallerand (2003), results showed that coaches more potently empha-sised controlling features of the environment rather than autonomy-supportive ones. In a studyinvolving French physical education teachers, and using a different systematic observationsystem, Tessier et al. (2008) observed a similar trend; only 11.5% of the overt teachers’ beha-viours were autonomy-supportive.

Research shows that several forces influence whether and to what extent a person in position ofauthoritywill display amorecontrolling than autonomy-supportive interpersonal style during instruc-tion. Among the seven meaningful influences identified (Pelletier, Séguin-Lévesque, & Legault,2002; Reeve, 2009)—distributed in “pressures from above” (e.g. club manager and state standards),“pressures from below” (e.g. players) and “pressure from within” (e.g. coach’s own beliefs, valuesand personality dispositions)—three might explain the conditions under which grassroots soccercoaches are likely to overemphasise a controlling motivating style to the detriment of an auton-omy-supportive one. First, coaches occupy an inherently powerful position in the social context.To the extent that such an inherent power differential exists, players who are one-down in thepower relationship are vulnerable to being controlled by coaches who are one-up in the powerrelationship. Additionally, coachesmay be aware that being controlling is culturally valued. Culturesin industrialised countries view controlling strategies as optimal ways to motivate athletes in an

Figure 2. Pattern of the mean dimensions scores for the coach-created objective motivational climate ineach country.Notes: Related sup., relatedness support; auto. sup, autonomy support; task invol., task involving; related.thwart., Relatedness thwarting; ego invol., ego involving.

14 D. Tessier et al.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dam

ien

Dam

ien]

at 1

1:49

21

Oct

ober

201

3

attempt to produce maximal performance. People endorse these beliefs as a result of the immediatebeneficial effects of utilising controlling strategies (e.g. situationally turns motivation “on”), whilstthey overlook the negative implications and less apparent long-term effects these strategies mayhave (e.g. developmentally turnsmotivation “off”, particularly the quality of themotivation). Further-more, the reliance on a controllingmotivating style could also be a reaction to players’ perceived pas-sivity during training.When coaches perceive their players are low in “motivation” and engagement,or being disruptive and behaviourally difficult to deal with, they tend to react by adjusting theirinstructional behaviour towards a more controlling style.

Although a difference in the potency of autonomy-supportive and controlling features of theenvironment was noted, the observed mean dimension values were both relatively low (i.e. belowthe theoretical mean of 1.5). This trend was also noted for the task- and ego-involving, and relat-edness-supportive and relatedness-thwarting dimensions. The only potency ratings above thetheoretical mean were the structure and task-involving features of the coach-created climate.This suggests there is potential (and a need) for coaches to be trained to create more need-support-ing environments. These findings also indicate that education programmes focusing on thereduction of need-thwarting features of the environment may be less necessary in this sampleof youth grassroots sports coaches. As a result of these findings two conclusions can bedrawn: (1) the objective coach-created motivational climate is characterised by a lack of need-supportive features rather than an emphasis on need-thwarting ones and (2) in terms of futureintervention attempts, coaches may benefit more from instruction in how to become more“empowering” (Duda, 2013; Duda et al., 2013) by being need-supportive with their players,than to be less “disempowering” by reducing need-thwarting features.

Another point merits to be highlighted is evidence regarding the construct validity of theMMCOS (Smith et al., in preparation) in this study. The high correlation between the structureand task-involving dimensions indicated high overlap between these two constructs. Accordingto SDT, structure can be provided in either an autonomy-supportive or a controlling way (Deci& Ryan, 1985). Thus theoretically, structure could also be considered separately from bothtask- and ego-involving features of the environment. Empirically, studies (Jang et al., 2010;Sierens et al., 2009) have shown that when teachers’ naturally occurring interpersonal stylesare scored by raters, providing structure is positively correlated with the provision of autonomysupport and negatively correlated with the provision of control. This result is partially confirmedby the present study, as structure and autonomy support are highly correlated (r = .59, p < .001),but structure and control are not (r = .07, p = ns). Hence, as was the case in this study, the pro-vision of a structured learning environment being closely associated with both an autonomy-supportive and task-involving style is not surprising. In the future, it will be necessary toexamine how these dimensions of the environment interact to predict athletes’ need satisfactionand thwarting, goal orientation and motivational regulations and overall emotional and behaviour-al responses. Finally, the findings of the present study provide partial support for the work con-ducted by Bartholomew et al. (2011), which showed that need thwarting and need satisfactionwere not correlated. The correlation between autonomy support and control was not significant(r = −.22, p = ns), whilst the correlation between relatedness support and relatedness thwartwas moderate and negative (r =−.50, p < .01). This implies that coaches can be exhibitingboth autonomy supportive and controlling behaviours, but when a coach is relatedness supportivethere is a stronger tendency for him/her to be less relatedness thwarting in his/her behaviours.As for the observed positive correlation between the task- and ego-involving dimensions (r = .43,p < .05), it might mean that coaches want to reach both goals, make their players improve theirskills or apply efforts, and at the same time, demonstrate superior ability. Nevertheless, this positivecorrelation is different from the typical correlation score (i.e. −.30) obtained with players’ self-reported measures (Newton, Duda, & Yin, 2000). This may be explained by the point that objective

International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 15

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dam

ien

Dam

ien]

at 1

1:49

21

Oct

ober

201

3

and perceived assessment of motivational climate represent two different facets of the samereality. Whereas, in the self-report case, the players may take into account their own criteriafor defining success (and judging their competence) when responding to the questionnairetapping their perceptions of the task- and ego-involving features of the environment. In contrast,in the observation case, the raters only code what the coaches say and do, and lean on specificstrategies mentioned on the marking scheme. As a consequence, it is possible that it would bemore likely to pick up the coach engaging in behaviours that are not only task involving butalso other (or perhaps the same) behaviours which have an ego-involving meaning. Investigationsconducted in different contexts with different ages, competitive levels and bigger coach samplesizes will be needed to confirm the construct validity of the MMCOS in terms of the differentenvironment dimensions assessed.

Differences between coaches across countries

The results (Tables 2 and 3) revealed that coaches’ interpersonal styles varied significantly acrosscountries. In essence, the coaches from England and Greece were more autonomy supportive, taskinvolving, ego involving, relatedness supportive and structured, than the ones from France. Inaddition, the coaches from England were more autonomy supportive, relatedness supportive andemphasised more on the structure than the coaches from Greece. All 57 coaches are equally control-ling, and relatedness thwarting. Although we expected to find no country differences betweencoaches, meaning there would be homogeneity across the whole group, we were open to the possi-bility that individual differences could emerge. On the basis of the observational pilot study, whichrevealed that the lead observational researchers in each country had a high degree of consistencyin the coding of the same video clips of trainings (Tzioumakis et al., 2012), it is reasonable tosuggest that these differences are not due to variations between raters across countries in viewingthe climate constructs. It may be that the observed between-country differences can be explainedby individual characteristics—other than coaches’ age, experience in coaching and level of qualifica-tion—or social influences—other than players’ age—thatwere not assessed in the present study. Indi-vidual characteristics such as the coaches’ values, beliefs ormotivation should be considered in futurestudies.As for the social influences, these could be country-variable differences in influences from theclub, the parents or the players whomay pressurise the coach in order for their child or team to reach ahigh normative standard of performance, to select their child for particular positions or pay moreattention to their child’s playing time or progress.

Although between-country differences were observed it is important to state that, as seen fromFigure 2, the general pattern of the coach-created environment observed in the three countries hasa similar profile. In addition, the fact that T1 country based-differences have emerged will not be aproblem for the PAPA project, as these baseline differences will be controlled for in the forthcom-ing statistical analysis in taking into account the self-regressive effect on T2 variables.

Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to investigate to what extent the differences in the objective moti-vational climate created by the coaches were a function of their country of residence. The resultsshowed that coaches’ interpersonal style varied significantly across countries. However, the mainfinding of this study was that across England, Greece and France, the objectively observed multi-dimensional coach-created climate was more characterised by a lack of need-support rather thanan emphasis on need-thwarting behaviours. Given that the coach is an influential figure likely toshape the welfare and optimal functioning of his or her athletes, this study provides a rationale for

16 D. Tessier et al.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dam

ien

Dam

ien]

at 1

1:49

21

Oct

ober

201

3

conducting future studies that are designed to educate coaches on how to create more need-sup-portive and -adaptive motivational environments in sport.

Notes1. This is in contrast to other observation research (Smith et al., 1977; Lacy & Darst, 1985) where

researchers have chosen to split videos into 3-, 5- or 15-minute blocks and inevitably means that aportion of the video will be missed. Which could hold particular relevance for the coach-created moti-vational climate.

2. The marking scheme is available upon request from the first author.

ReferencesAdair, J. G., Sharpe, D., & Huynh, C. L. (1989). Placebo, Hawthorne, and other artefact controls:

Researchers’ opinions and practices. Journal of Experimental Education, 57, 335–341.Adie, J., Duda, J. L., & Ntoumanis, N. (2008). Autonomy support, basic need satisfaction and the optimal

functioning of adult male and female sport participants: A test of basic needs theory. Motivation andEmotion, 32, 189–199.

Adie, J. W., Duda, J. L., & Ntoumanis, N. (2012). Perceived coach-autonomy support, basic need satisfactionand the well- and ill-being of elite youth soccer players: A longitudinal investigation. Psychology ofSport and Exercise, 13, 51–59.

Ames, C. (1992). Classrooms: Goals, structures, and student motivation. Journal of Educational Psychology,84, 261–271.

Ames, C., & Archer, J. (1988). Achievement goals in the classroom: Students’ learning strategies and motiv-ation processes. Journal of Educational Psychology, 80, 260–267.

Ames, C. A. (1984). Competitive, cooperative, and individual goal structures: A cognitive-motivationalanalysis. In R. Ames & C. Ames (Eds.), Research on motivation in education: Student motivation(pp. 177–207). New York: Academic Press.

Ames, C. A., Ames, R., & Felker, D. (1977). Effects of competitive reward structure and valence of outcomeon children’s achievement attributions. Journal of Educational Psychology, 69, 1–8.

Amorose, A. (2007). Coaching effectiveness: Exploring the relationship between coaching behavior andself-determined motivation. In M. Hagger & N. Chatzisarantis (Eds.), Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in exercise and sport (pp. 143–152). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Baard, P. P., Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2004). Intrinsic need satisfaction: A motivational basis of perform-ance and well-being in two work settings. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 34, 2045–2068.

Bakeman, R., & Gottman, J. M. (1997). Observing interaction: An introduction to sequential analysis(2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bartholomew, K., Ntoumanis, N., Ryan, R. M., & Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C. (2011). Psychological needthwarting in the sport context: Development and initial validation of a psychometric scale. Journal ofSport and Exercise Psychology, 33, 75–102.

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fun-damental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 497–529.

Boyce, B. A., Gano-Overway, L. A., & Campbell, A. (2009). The perceived motivational climate’s influenceon goal orientations, perceived competence, and practice strategies across the competitive athleticseason. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 21, 381–394.

Bryk, A. S., & Raudenbush, S. W. (1992). Hierarchical Linear models in social and behavioural research:Applications and data analysis methods (1st ed.). Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Darst, P. W., Zakrajsek, D. B., & Mancini, V. H. (Eds.). (1989). Analyzing physical education and sportinstruction (2nd ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior.New York: Plenum Publishing.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1987). The support of autonomy and the control of behavior. Journal ofPersonality and Social Psychology, 53, 1024–1037.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1991). A motivational approach to self: Integration in personality. In R. Dienstbier(Ed.), Nebraska symposium on motivation: Perspectives on motivation (Vol. 38, pp. 237–288). Lincoln:University of Nebraska Press.

International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 17

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dam

ien

Dam

ien]

at 1

1:49

21

Oct

ober

201

3

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-deter-mination of behaviour. Psychology Inquiry, 11, 227–268.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (Eds.). (2002). Handbook of self-determination research. Rochester: TheUniversity of Rochester Press.

Deci, E. L., Schwartz, A., Sheinman, L., & Ryan, R. M. (1981). An instrument to assess adult’s orientationstoward control versus autonomy in children: Reflections on intrinsic motivation and perceived compe-tence. Journal of Educational Psychology, 73, 642–650.

Duda, J. L. (2001). Achievement goal research in sport: Pushing the boundaries and clarifying some misun-derstandings. In G. C. Roberts (Ed.), Advances in motivation in sport and exercise (pp. 129–183).Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Duda, J. L. (2005). Motivation in sport: The relevance of competence and achievement goals. In A. J. Elliot& C. S. Dweck (Eds.), Handbook of competence and motivation (pp. 318–335). New York, NY: TheGuilford Press.

Duda, J. L. (2013). The conceptual and empirical foundations of Empowering Coaching™: Setting the stagefor the PAPA project. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology. doi: 10.1080/1612197X.2013.839414

Duda, J. L., & Balaguer, I. (2007). The coach-created motivational climate. In S. Jowett & D. Lavalee (Eds.),Social psychology of sport (pp. 117–130). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Duda, J. L., Quested, E., Haug, E., Samdal, O., Wold, B., Balaguer, I., … Cruz, J. (2013). PromotingAdolescent health through an intervention aimed at improving the quality of their participation inPhysical Activity (PAPA): background to the project and main trial protocol. International Journal ofSport and Exercise Psychology. doi: 10.1080/1612197X.2013.839413

Farkas, M. S., & Grolnick, W. S. (2010). Examining the components and concomitants of parental structurein the academic domain. Motivation and Emotion, 34, 266–279.

Fleiss, J. L. (1981). Statistical methods for rates and proportions (2nd ed.). New York: John Wiley.Gagné, M., Ryan, R. M., & Bargmann, K. (2003). Autonomy support and need satisfaction in the motivation

and well-being of gymnasts. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 15, 372–390.Haerens, L., Aelterman, N., Van den Berghe, L., De Meyer, J., Soemens, B., & Vansteenkiste, M. (2013).

Observing physical education teachers’s need-supportive interactions in classroom setting. Jounal ofSport and Exercise Psychology, 35(1), 3–17.

Horn, T. (Ed.). (2002). Advances in sport psychology. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.Jang, H., Reeve, J., & Deci, E. L. (2010). Engaging students in learning activities: It’s not autonomy support

or structure, but autonomy support and structure. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102, 588–600.Keegan, R., Harwood, C., Spray, C., & Lavallee, D. (2011). From “motivational climate” to “motivational

atmosphere”: A review of research examining the social and environmental influences on athlete motiv-ation in sport. In B. Geranto (Ed.), Sport psychology (pp. 1–55). Hauppauge, NY: Nova.

Kenny, D. A., Kashy, D. A., & Bolger, N. (1998). Data analysis in social psychology. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T.Fiske, & G. Lindsey (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (4th ed., Vol. 1, pp. 233–265).New York: McGraw-Hill.

Lacy, A. C., & Darst, P. W. (1985). Systematic observation of behaviors of winning high school head footballcoaches. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 4, 256–270.

Mageau, G. A., & Vallerand, R. J. (2003). The coach-athlete relationship: A motivational model. Journal ofSport Sciences, 21, 883–904.

Newton, M., Duda, J. L., & Yin, Z. N. (2000). Examination of the psychometric properties of the PerceivedMotivational Climate in Sport Questionnaire-2 in a sample of female athletes. Journal of SportsSciences, 18, 275–290.

Nicholls, J. G. (1989). The competitive ethos and democratic education. Cambridge, MA: HarvardUniversity Press.

Pelletier, L., Séguin-Lévesque, C., & Legault, L. (2002). Pressure from above and pressure from below asdeterminants of teachers’ motivation and teaching behaviors. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94,186–196.

Pintrich, P. R. (2003). A motivational science perspective on the role of student motivation in learning andteaching contexts. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95, 667–686.

Quested, E., & Duda, J. L. (2010). Exploring the social-environmental determinants of well- and ill-being indancers: A test of basic needs theory. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 32, 39–60.

Rasbash, J., Browne, W., Goldstein, H., Yang, M., Plewis, I., Woodhouse, G., … Lewis, T. (2000). A user’sguide to MLwin. London: Institute of Education, University of London.

18 D. Tessier et al.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dam

ien

Dam

ien]

at 1

1:49

21

Oct

ober

201

3

Reeve, J. (2002). Self-determination theory applied to educational setting. In E. L. Deci & R. M. Ryan (Eds.),Handbook of self-determination research (pp. 183–203). Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press.

Reeve, J. (2009). Why teachers adopt a controlling motivating style toward students and how they canbecome more autonomy supportive. Educational Psychologist, 44, 159–178.

Reeve, J., & Jang, H. (2006). What teachers say and do to support students’ autonomy during a learningactivity. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98, 209–218.

Reeve, J., Jang, H., Carrell, D., Jeon, S., & Barsh, J. (2004). Enhancing students’ engagement by increasingteachers’ autonomy support. Motivation and Emotion, 28, 147–169.

Reinboth, M., Duda, J. L., & Ntoumanis, N. (2004). Dimensions of coaching behaviour, need satisfaction,and the psychological and physical welfare of young athletes. Motivation and Emotion, 28, 297–313.

Roberts, G. C. (2001). Understanding the dynamics of motivation in physical activity: The influence ofachievement goals on motivational processes. In G. C. Roberts (Ed.), Advances in motivation in sportand exercise (pp. 1–50). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Robinson, W. S. (1950). Ecological correlations and the behaviors of individuals. American SociologicalReview, 15, 351–357.

Ryan, R. M. (1995). Psychological needs and the facilitation of integrative processes. Journal of Personality,63, 397–427.

Ryan, R., & Deci, E. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions.Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 54–67.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2002). An overview of self-determination theory. In E. L. Deci & R. M. Ryan(Eds.), Handbook of self-determination research (pp. 3–33). Rochester, NY: University of RochesterPress.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2007). Active human nature: Self-determination theory and the promotion andmaintenance of sport, exercise, and health. In M. S. Hagger & N. L. D. Chatzisarantis (Eds.), Intrinsicmotivation and self-determination in exercise and sport (pp. 1–19). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Ryan, R. M., Patrick, H., Deci, E. L., & Williams, G. C. (2008). Facilitating health behaviour change and itsmaintenance: Interventions based on self-determination theory. The European Health Psychologist, 10,2–5.

Sierens, E., Vansteenkiste, M., Goossens, L., Soenens, B., & Dochy, R. (2009). The synergistic relationshipof perceived autonomy support and structure in the prediction of self-regulated learning. British Journalof Educational Psychology, 79, 57–68.

Skinner, E. A., & Belmont, M. J. (1993). Motivation in the classroom: Reciprocal effects of teacher behav-iour and student engagement across the school year. Journal of Educational Psychology, 85, 571–581.

Skinner, E. A., & Edge, K. (2002). Parenting, motivation, and the development of children’s coping. In L. J.Crockett (Ed.), Agency, motivation, and the life course: The Nebraska symposium on motivation(Vol. 48, pp. 77–143). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Smith, A. L., Ntoumanis, N., & Duda, J. L. (2007). Goal striving, goal attainment, and well-being: An adap-tation of the self-concordance model in sport. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 29, 763–782.

Smith, N., Tessier, D., & Tzioumakis, Y. (in preparation). Development and Validation of theMultidimensional Motivational Climate Observation System (MMCOS).

Smith, R. E., Smoll, F. L., & Hunt, E. B. (1977). A system for the behavioural assessment of athletic coaches.Research Quarterly, 48, 401–407.

Tessier, D., Sarrazin, P., & Ntoumanis, N. (2008). The effects of an experimental programme to support stu-dents’ autonomy on the overt behaviours of physical education teachers. European Journal ofPsychology of Education, 3, 239–253.

Tessier, D., Sarrazin, P., & Ntoumanis, N. (2010). The effect of an intervention to improve newly qualifiedteachers’ interpersonal style. Students motivation and psychological need satisfaction in sport-basedphysical education. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 35, 242–253.

Tzioumakis, Y., Papaioannou, A., Digelidis, N., Zourbanos, N., Krommidas, H., & Keramidas, P. (2012).Consistency of the environmental dimensions of an observational instrument assessing coach initiatedmotivational climate. 17th Annual ECSS-congress, Bruges.

Van der Mars, H. (1989). Systematic observation: An introduction. In P. W. Darst, D. B. Zakrajsek, & V. H.Mancini (Eds.), Analyzing physical education and sport instruction (2nd ed., pp. 3–19). Champaign, IL:Human Kinetic.

International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 19

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Dam

ien

Dam

ien]

at 1

1:49

21

Oct

ober

201

3

![P-omission under sluicing, [P clitic] and the nature of P-stranding](https://static.fdokumen.com/doc/165x107/632111e6f2b35f3bd10fb543/p-omission-under-sluicing-p-clitic-and-the-nature-of-p-stranding.jpg)