Sumergido/ Submerged. Alternative Cuban Cinema

Transcript of Sumergido/ Submerged. Alternative Cuban Cinema

sumergido / submergedCine Alternativo Cubano • Alternative Cuban Cinema

Luis Duno-Gottberg & Michael J. Horswell

literalpublishing

Diseño de portada e interiores: DMPLa imagen de portada en una obra de Miguel Coyula

Primera edición 2013

Todos los derechos reservados

© 2013 Luis Duno-Gottberg and Michael J. Horswell© 2013 Literal Publishing

5425 RenwickHouston, Texas 77081www.literalmagazine.com

ISBN: 978-0-9770287-7-1

Ninguna parte del contenido de este libro puede reproducirse, almacenarse o trans-mitirse de ninguna forma, ni por ningún medio, sea éste electrónico, químico, me-cánico, óptico, de grabación o de fotocopia, sin el permiso de la casa editorial.

Impreso y hecho en México / Printed and made in Mexico

Índice

]9[Bienvenida e introducción

Luis Duno-Gottberg & Michael J. Horswell

]15[Notas sobre el audiovisual cubano contemporáneo

Juan Antonio García Borrero

]27[Después del icaic: Los tres imperativos categóricos

del audiovisual cubano actualDean Luis Reyes

]51[Cine dependiente, Cine pendiente

Miguel Coyula

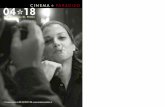

]57[Programa del festival

]81[Iconografía

] 9 [

Sumergido: Festival de Cine Alternativo Cubano

Bienvenida e introducción

Luis Duno-Gottberg (Rice University) Michael J. Horswell (Florida Atlantic University)

En el contexto del cine cubano contemporáneo, ¿qué es “al-ternativo”? ¿Es acaso lo mismo que “independiente”, “experi-mental” o “subterráneo”? Al explorar esta cuestión, debemos considerar la preminencia que ha tenido el Instituto Cubano de Arte e Industria Cinematográficos (icaic) en el desarrollo y consolidación de una industria cubana de cinematografía. Esta presencia institucional dista mucho de haber sido estáti-ca y, a lo largo de su historia, han existido momentos de gran innovación y experimentación radical, seguidos, en ocasiones, de estancamiento y expresiones formulaicas. En este sentido, el surgimiento de un “cine cubano subterráneo” da cuenta de las relaciones incómodas entre las instituciones de un Estado altamente comprometido con la cultura y una serie de discursos que, con frecuencia, se resisten a ser institucionalizados o coop-tados. Sin embargo, sería un gran error reducir la noción de un cine alternativo a aquellos trabajos que se producen fuera del circuito estatal. Es una ilusión pensar que la creciente disponi-bilidad de capital y financiamiento privado generará un espacio de libertad total para los cineastas. A medida que el Estado se

] 10 [

repliega, otros poderes se asoman, con nuevas exigencias. Las estructuras trilladas y las narrativas convencionales podrían re-gresar por la puerta trasera, seducidas por promesas de financia-miento no estatal y una taquilla más jugosa. Lo nuevo, lo que brindará formas novedosas de ver y contar historias, está más allá del mero asunto del apoyo/patrocinio/control estatal de la industria cinematográfica.

Para los fines del festival que organizamos se selecciona-ron películas que representan una alternativa a expresiones ci-nematográficas que gozan del apoyo institucional del Estado, pero también obras que cuestionan temas y estructuras tradi-cionales. Estas son películas cuyos personajes, tópicos, puntos de vista y estructuras formales se hayan ausentes en el cine cubano tradicional. Algunas de éstas son “experimentales” por cuanto desafían los límites del medio y los procesos de produc-ción y distribución. Otras son “subterráneas” porque funcio-nan fuera de lo que Juan Antonio García Borrero denominó “icaicentrismo”. Estas películas connotan algo subversivo que incomoda a las audiencias y desarma exceptivas y tradiciones que trascienden las cortapisas que hubiera podido imponer la cultura visual oficialista. Su osadía es relevante para un ámbito que va más allá de lo cubano.

El festival fue posible gracias a la colaboración entre cua-tro universidades (Florida Atlantic University, Rice University, Tulane University y Princeton University) y nuestros colegas e instituciones colaboradoras de Cuba. Nos esforzamos por reunir algunas de las películas más notables producidas en Cuba duran-te los últimos años; películas que muestran las nuevas realidades de un país que ha experimentado transformaciones profundas en los últimos cinco años, debido a un incipiente proceso de flexibilización de las estructuras económicas. El mapa es, por su-

] 11 [

puesto, mucho más amplio de lo que aquí presentamos. Además de proyectar dieciocho cortos, medios y largos, representativos de diversos géneros cinematográficos, múltiples contextos de producción y distribución, y varios directores tanto consagrados como emergentes, tenemos la fortuna de contar con la contri-bución de académicos y críticos notables. Los invitamos a leer los ensayos de este programa que, lejos de ser uno de esos catálo-gos tradicionales que acompañan las muestras cinematográficas, ofrece un análisis profundo del cine cubano contemporáneo.

Juan Antonio García Borrero es considerado como uno de los críticos de cine cubano más importantes del momento. Su ensa-yo nos ofrece una fascinante reflexión sobre las transformaciones de la industria cinematográfica cubana a medida que el icaic pierde control sobre la producción, distribución y promoción del cine en la isla. Su perspectiva del proceso es única, en tanto intelectual líder de una generación que participa de las trans-formaciones desde una periferia (la provincia de Camagüey). Su reflexión sobre el modo en que las películas incluidas en esta serie representan un ángulo singular de la “Cuba sumergida” han de despertar debates sobre lo que emerge como “cine independien-te” en la isla y sus relaciones con la heterogeneidad del país y las fuerzas de la globalización en un periodo de aperturas, cuando la experimentación va más allá de géneros, estéticas, formatos y modos de distribución nuevos.

Dean Luis Reyes, curador de esta muestra, ha sido profesor del eictv e investigador independiente del cine cubano. Él nos ofrece una historia amplia del cine cubano contemporáneo y su relación con las transformaciones del contexto post-icaic. En su trabajo identifica lo que denomina “tres imperativos del cine cubano contemporáneo,” que incluyendo aspectos institucio-nales, tecnológicos y temático-estilísticos proporcionan un sen-

] 12 [

tido de unidad al corpus diverso que integra nuestro festival. Su interpretación de las películas del programa ofrecen a nuestra audiencia elementos para una experiencia de visualización pro-ductiva. A partir de allí se podrán observar los patrones que emergen en la producción reciente y se apreciarán mejor los ejes temáticos que hemos utilizado para organizar la muestra.

Miguel Coyula es uno de los cineastas independientes más conocidos de Cuba y su famosa película Memorias del desarrollo forma parte de esta muestra. El director ha contribuido tam-bién al presente catálogo con un ensayo sobre la dicotomía cine dependiente/independiente. Su reflexión, profundamente per-sonal, ofrece al espectador una mirada dentro del proceso crea-tivo de un director y su particular percepción/recepción de sus contemporáneos. Su meditación nos lleva a ponderar qué sig-nifica “independiente” en el circuito internacional de festivales y desde la perspectiva de un joven que trabaja desde Cuba, pero fuera de los circuitos tradicionales de la industria nacional.

Este programa se organizó en torno a seis núcleos temático-formales: “Mitología tropical” reúne cuatro trabajos que explo-ran de algún modo mitos y leyendas cubanas, haciendo referen-cia al universo del inconsciente; “Ruinas y espectros” aborda los restos de grandes narrativas históricas cubanas que se van bo-rrando o distorsionando con la fragilidad de la memoria o el simple abandono; “Electrones libres” reúne apuestas que esca-pan intencionalmente a clasificaciones fáciles y rompen con los repertorios tradicionales del cine cubano; “Las políticas de la memoria” confronta la dimensión afectiva de cinco décadas de devenir histórico mediante múltiples lentes/generaciones; “La persistencia de un sueño” propone exploraciones desafiantes del gran proyecto/sueño de la Revolución; “Postnacionalismo, pos-cinemático” cierra el ciclo con una apuesta que rompe con los

] 13 [

confines geográficos de la isla y aborda concepciones amplias de la cubanidad mientras explora con virtuosismo el potencial de las tecnologías digitales.

Queremos agradecer a las muchas personas que nos asistie-ron en este proyecto, a las cuatro instituciones que nos patroci-nan lo mismo que a nuestros colegas y amigos.

A continuación ofrecemos los ensayos producto de este fes-tival con la esperanza de que disfruten las discusiones que ellos, sin duda, suscitarán.

Sobre los editores:

Luis Duno-Gottberg es Profesor Asociado de Estudios Caribeños y de Cine en el Departamento de Estudios Hispánicos de Rice University. Ha enseñado en la Universidad de Simón Bolívar en Caracas y en Florida At-lantic University en Boca Raton, donde dirigió el programa de Estudios Latinoamericanos y la maestría en Literaturas Comparadas. Se especializa en los siglos xix y xx de la cultura caribeña, con énfasis en asuntos de raza y etnicidad, política y violencia. Su investigación actual, Dangerous People: Hegemony, Representation and Culture in Contemporary Venezuela, explora la relación entre la movilización popular, la política radical y la cultura. Es editor de varios volúmenes sobre cine latinoamericano, incluyendo Miradas al margen. Subalternidad y representación en el cine de América Latina y el Caribe (Caracas: Cinemateca Nacional/Ministerio de Cultura, 2008).

Michael J. Horswell es Profesor Asociado de Literatura Latinoamericana en el Departamento de Lenguas, Linguística y Literaturas Comparadas de Flo-rida Atlantic University. Es el Decano Asociado Interino y Director del Programa de Doctorado en Estudios Comparados de la Facultad de Artes y Letras. Se especializa en literatura colonial y estudios andinos. Su libro Decolonizing the Sodomite: Queer Tropes of Sexuality in Andean Colonial Cul-ture (University of Texas Press, 2006) acaba de salir en español en segunda

] 14 [

edición como La descolonización del “sodomita” en los Andes coloniales (Qui-to: Abya Yala, 2013). Actualmente escribe sobre el barroco y neobarroco andinos en literatura y cine.

] 15 [

Notas sobre el audiovisual cubano contemporáneo

Juan Antonio García Borrero

El 4 de mayo del 2013, un grupo de aproximadamente 60 ci-neastas cubanos decidió reunirse, de modo espontáneo, en el Centro Cultural Fresa y Chocolate (perteneciente al icaic), con el fin de debatir asuntos relacionados con la renovación de la industria audiovisual en Cuba.

En el primer documento suscrito públicamente por el gru-po de trabajo electo para “representar a los cineastas en todas las instancias y eventos, propiciar y garantizar la participación activa de los mismos en todas las decisiones y proyectos que se relacionen con el cine cubano, y luchar por la protección y de-sarrollo de estas artes e industrias y sus hacedores”, puede leerse en el acuerdo preliminar:

Reconocemos al Instituto Cubano del Cine y la Industria Cine-matográficos (icaic) como el organismo estatal rector de la acti-vidad cinematográfica cubana; nació con la Revolución y su larga trayectoria es un legado que pertenece a todos los cineastas. Al propio tiempo, consideramos que los problemas y las proyeccio-nes del cine cubano en la actualidad no atañen sólo al icaic, sino también a otras instituciones y grupos que de manera institu-cional o independiente están implicados en su producción, y sin

] 16 [

cuyo concurso y compromiso no es posible alcanzar soluciones válidas y duraderas. Por esa razón, su reorganización y fomento no puede hacerse sólo en el marco de este organismo.1

La improvisada reunión parece marcar el inicio de una nueva era de la creación audiovisual en Cuba, pero en verdad desde hace mucho venía teniendo lugar ese punto de giro caracteri-zado por el salto tecnológico, el ingreso a la esfera pública de una nueva generación de realizadores graduados en recintos académicos como el Instituto Superior de Arte (isa) y la Es-cuela Internacional de Cine y Televisión de San Antonio de los Baños (eictv), con la consiguiente pérdida del liderazgo creativo del icaic, principal centro productor de audiovisuales del país.

Los últimos cinco o seis años de creación audiovisual en Cuba, habían terminado por confirmar los principales pro-nósticos que se formularan en los inicios de la primera década del siglo xxi. En primer lugar, la revolución electrónica que se viene experimentando en el mundo, pese a las precariedades económicas que siguen sacudiendo a la isla, ha contribuido no sólo a democratizar la producción de ese audiovisual, sino que ha permitido que un gran número de jóvenes, muchos de ellos graduados del Instituto Superior del Arte (isa), o la Escuela In-ternacional de Cine y tv de San Antonio de los Baños (eictv), entre otros centros docentes, hagan suyo ese oficio que con an-terioridad parecía reservado a quienes laboraban en el Instituto Cubano de Artes e Industrias Cinematográficas (icaic).

1 “Cineastas cubanos por el cine cubano”. Puede consultarse en http://cinecubanolapupilainsomne.wordpress.com/2013/05/11/cineastas-cuba-nos-por-el-cine-cubano/

] 17 [

Ya en su libro Romper la tensión del arco, el cineasta Jorge Luis Sánchez había apuntado con gran lucidez:

Cuando en el año 2000 Alfredo Guevara, vértice esencial de la ge-neración fundadora, pide salir de la dirección del icaic, parecería que llegó el irreversible final. No sucedió, pero con la llegada del siglo xxi surge otro icaic, y otra idea de diseño de la organización del cine cubano comenzará a imponerse.2

Podría decirse que el primer paso que en ese sentido da la nueva dirección del icaic, encarnada en la persona de Omar González (sucesor de Guevara como presidente, cargo que sigue ocupan-do en la actualidad), es la organización de la Primera Muestra Nacional del Audiovisual Joven, la cual se celebra en La Ha-bana del 31 de octubre al 3 de noviembre del 2000. El evento tenía como objetivo principal diseñar un espacio en el cual se pudiera detectar el talento real de aquellos que, en teoría, esta-ban llamados a ser el relevo generacional de los cineastas que hasta ese instante habían hecho su obra al amparo del icaic.

En las primeras ediciones de la Muestra se puso de mani-fiesto la vitalidad de un grupo de jóvenes realizadores donde so-bresalía, sobre todo, la heterogeneidad de sus intereses. Si bien en el programa inaugural de la primera cita llamaron la aten-ción los jóvenes Miguel Coyula con Clase Z Tropical (2000), Esteban García Insausti con Más de lo mismo (2000), Aarón Vega (Se parece a la felicidad, 1998), Juan Carlos Cremata (La época, El encanto y Fin de siglo, 1999) y Gustavo Pérez (Caidi-

2 Jorge Luis Sánchez Gonzalez. Romper la tensión del arco (Movimiento cubano de cine documental). Ediciones icaic, La Habana, 2010, p 325.

] 18 [

je… La extensa realidad, 2000), entre otros, todavía no puede hablarse allí de un verdadero punto de giro en la producción de ese audiovisual contemporáneo.

El punto de giro, en todo caso, habría que localizarlo en lo que está pasando desde hace cinco o seis años en este conjun-to de nuevos realizadores, cuando lentamente, pero de manera consistente, ha comenzado a advertirse una mayor ambición y complejidad en el tratamiento de las historias contadas, así como un mayor dominio del lenguaje cinematográfico, tanto en el documental, como en la ficción. Algo de eso puede de-ducirse de lo que afirman en el libro Los cien caminos del cine cubano los investigadores Marta Díaz y Joel del Río:

(…) Así, el 2007 tal vez sea recordado por los historiadores del cine cubano como el punto de giro que indicó las potencialidades del relevo generacional, y la entronización en el audiovisual cubano de una perspectiva más distendida y genérica. Cuatro de los filmes cubanos estrenados comercialmente fueron dirigidos mayormen-te por nuevos directores: La edad de la peseta (Pavel Giroud), La pared (Alejandro Gil), Personal Belongings (Alejandro Brugués) y Mañana (Alejandro Moya), los dos últimos producidos fuera del icaic dentro de las “políticas” del digital y el bajo presupuesto. A renglón seguido se estrenaron La noche de los inocentes (Arturo Sotto), Madrigal (Fernando Pérez), Camino al Edén (Daniel Díaz Torres) y El viajero inmóvil (Tomás Piard).3

Con lo anterior se nos está sugiriendo que si queremos obtener una idea un poco más integral del panorama audiovisual cubano

3 Marta Díaz, Joel del Río. Los cien caminos del cine cubano. Ediciones icaic, La Habana, 2010, p 95.

] 19 [

del último lustro, tendremos que aplicar en el análisis una pers-pectiva de conjunto que permita valorar cómo interactúan entre sí las dinámicas institucionales (procedentes del icaic) y las al-ternativas que puedan apreciarse más allá de ese campo simbó-licamente legitimado. A ello habría que sumar la conciencia de que, en este momento histórico, no existe un ente hegemónico que pueda estar marcando la tendencia dominante en lo público.

A diferencia de épocas anteriores, donde la institución icaic gozaba no sólo del monopolio de la creación cinematográfica, sino también de la distribución y promoción de sus productos, en la actualidad la multiplicación informal de canales de producción y consumo audiovisual ha puesto en crisis absoluta el antiguo esquema de emisión y recepción. Sin embargo, si bien el icaic pareciera ser el gran perdedor en este nuevo escenario, no podría afirmarse que los llamados “independientes” hayan ganado visi-bilidad definitiva ante un público que se muestra cada vez más desorientado en medio de la creciente y caótica jungla audiovi-sual contemporánea. A la pregunta de “¿qué está pasando con el cine cubano de los últimos cinco o seis años?” quizás deberíamos responder con otra interrogante no menos cargada de enigmas: “¿qué está pasando con los públicos cubanos del último lustro?”

Lo sucedido en la ciudad de Camagüey (Cuba) hace tres años, a propósito del 17 Taller Nacional de la Crítica Cinema-tográfica, puede revelarnos ángulos inéditos de esa opaca trans-formación que ya está operando en nuestros esquemas mentales asociados al cine cubano. Normalmente cuando se habla de “cine cubano”, no obstante la actual proliferación de materiales creados al margen, todavía se piensa en el cine producido por el icaic. Es a ese gesto involuntario lo que otras veces hemos llama-do icaicentrismo y que consistiría en la acción de narrar o pensar en la historia del cine cubano como si se tratara de la historia

] 20 [

del icaic. El icaicentrismo tiene maneras burdas de manifestarse, pero en verdad son las modalidades más sutiles las que mejor han contribuido a imponer esa imagen sesgada de la práctica audio-visual fomentada por los cubanos en las últimas cinco décadas.

Entre las más burdas podría contemplarse esa acción a través de la cual, por ejemplo, en una reciente Semana de Cine Cubano organizada por la Embajada de Cuba en Beirut, a última hora el embajador decidió cambiar el programa inaugural donde se anunciaba el estreno de Memorias del desarrollo (2010), de Mi-guel Coyula, por otra “más representativa del cine cubano” (léase producida por el icaic, que en este caso resultó ser Tres veces dos). En cuanto a las más sutiles, podríamos aludir precisamente a esas muestras nacionales e internacionales que terminan producien-do un sentido teleológico donde todo desemboca en el icaic, relato más tarde respaldado en circuitos académicos del Primer Mundo, y en el cual se recicla una y otra vez una historia del cine cubano apenas atenta a los textos y el impacto que estos provo-can en el intérprete, pero ajena a las profundas colisiones (no sólo ideológicas) que han dado lugar al corpus fílmico.

Lo ocurrido en Camagüey en aquella ocasión, si bien ape-nas ha sido advertido por críticos o estudiosos, marca un hito dentro de este conjunto de acciones que hoy nos permite afir-mar que, pese a esa apariencia de parálisis que hay alrededor del audiovisual cubano, las cosas no son tan en blanco y negro como las pintan. Paralelo al evento teórico que le da base al Taller Nacional de la Crítica Cinematográfica, se organiza en esa ciudad una suerte de festival a través del cual se muestra al público una gran cantidad de películas, priorizando la produc-ción cubana. Pues bien, en esa ocasión el público local tuvo la posibilidad de enfrentarse en tres noches sucesivas a tres fil-mes realizados por cubanos en distintas circunstancias; filmes

] 21 [

producidos de diversos modos, y con muy variados intereses: Martí, el ojo del canario, de Fernando Pérez, Molina’s Ferozz, de Jorge Molina, y Memorias del desarrollo, de Miguel Coyula.

Para un público habituado a esa suerte de uniformidad tex-tual que prevalece detrás de la multiplicidad de anécdotas pre-sentes en el cine “oficial”, debido a una política cultural que establece límites y contornos claramente ideológicos, asociados en este caso a la política revolucionaria del “dentro de la Revo-lución, todo; contra la Revolución, nada”, el asistir a estos tres filmes en tres noches sucesivas, pero en un mismo espacio sim-bólico (un evento organizado dentro de la isla), podía resultar, cuando menos, desconcertante.

La película de Fernando Pérez es una producción del icaic, pero ello (tratándose de un autor que se ha propuesto una poéti-ca claramente transgresora, aún operando en los predios institu-cionales) resultaría en sí mismo irrelevante; sólo que con Martí, el ojo del canario Fernando Pérez ha optado por renunciar a esos experimentos lingüísticos que, sobre todo en Madagascar y Suite Habana, habían contribuido a revitalizar los moldes expresivos del cine del icaic a partir de los años noventa.

Martí, el ojo del canario no carece de ese pulso revulsivo que ha mostrado en todo momento la obra de Pérez, inclu-so en su debut con Clandestinos, cuando apelando al cine de género nos mostraba a un grupo de “héroes” más allá de toda pretensión de convertirlos en mármol. En este nuevo filme Fernando Pérez se aproxima nada más y nada menos que a José Martí, el héroe nacional por excelencia, el Apóstol de Cuba, el hombre del cual aún se declaran depositarios de sus más no-bles ideas los grupos más irreconciliables en lo ideológico, y no puede decirse que la cinta eluda la complejidad expositiva (al menos en cuanto a la caracterización del Martí adolescente) si

] 22 [

bien hay una clara voluntad de respetar el modelo de represen-tación hegemónico.

Molina’s Ferozz estaría en el polo opuesto. Se trata de un ejemplo de cine bizarro que durante tanto tiempo fue exclui-do, ya no del repertorio de prácticas del cine cubano, sino del llamado nuevo cine latinoamericano, ese donde casi siempre un sujeto colectivo asociado a la masa, al pueblo, lidiaba con la Historia trazando para los realizadores del patio un perímetro demasiado estrecho de “la realidad”. Jorge Molina, el director del mencionado filme, desde antes ya se había propuesto rom-per con ese canon dominante, a través de una obra donde la presencia provocadora del sexo, la violencia y la muerte, obliga al espectador a sumergirse en áreas de la realidad que rompen con todos los esquemas preconcebidos.

Por su parte, Memorias del desarrollo, de Miguel Coyula, es tal vez el punto más alto que ha logrado el audiovisual cuba-no contemporáneo en su voluntad de emanciparse definitiva-mente de la tradición realista heredada de los años sesenta (la llamada “década prodigiosa del cine cubano”), para proponer una estética anti-canónica, llena de irreverencias conceptuales, pero sobre todo, subversora del modelo más común de repre-sentación de la realidad cubana.

Si me he detenido en este episodio que puede parecer demasiado anecdótico, es porque en el fondo posibilita una lectura bastante novedosa de lo que viene ocurriendo con el au-diovisual realizado por cubanos de estos tiempos. No sólo está el hecho de que se pusiera de manifiesto una inédita igualdad, a la hora de irrumpir en la escena pública, de tres productoras de audiovisuales (icaic, La Tiñosa Autista y Pirámide, respecti-vamente) con rangos de legitimidad totalmente diferentes, sino que formal y conceptualmente las tres películas nos muestran

] 23 [

a una Cuba dilatada donde lo que importa no es tanto el pai-saje (fundamentalmente urbano) que estamos acostumbrados a apreciar en pantalla, debido al realismo al uso que terminó con-virtiendo en hegemónico el cine más visible, como la creación de nuevos sentidos a partir del registro de una Cuba sumergida, una Cuba que se intuye a veces desde la perspectiva del vacío y el reacomodo de las representaciones sociales.

Esa voluntad de extrañeza ante la realidad se hace explícita en varios de los filmes más recientes del audiovisual cubano contemporáneo. En algunos, como puede ser el caso de La pis-cina (2011), de Carlos Machado, ese extrañamiento se pone de manifiesto haciendo un uso dramático de lo que está más allá del encuadre, más allá de lo que se dice por los personajes, o como en el caso de La película de Ana (2012), de Daniel Díaz Torres, con el cuestionamiento explícito del uso del cine a la hora de mostrar una realidad determinada. En ambos filmes, si bien sus directores construyen sus historias apelando a recursos en apariencia irreconciliables (Machado sumergiendo al espec-tador en un mundo más sensorial que narrativo; Díaz Torres edificando una historia llena de peripecias o equívocos), hay una intención bastante marcada de renunciar a aquella inge-nuidad de la cámara donde parecía que “la realidad” que se mostraba era la realidad misma.

De cualquier manera, aún cuando se note en lo colectivo una mayor preocupación por indagar en la naturaleza de ese conjunto de imágenes que se muestran, propiciando el expe-rimento estético, ello no significa que se haya abandonado el registro sociológico. Filmes de ficción como Irremediablemente juntos (2012), de Jorge Luis Sánchez, Verde, Verde (2012), de Enrique Pineda Barnet, o Melaza (2012), de Carlos Lechuga, se ocupan de plantear de un modo frontal conflictos derivados

] 24 [

de la supervivencia en la sociedad del racismo, la homofobia o los reajustes que en el plano socio-económico se han tenido que implementar con el fin de salvaguardar el proyecto socialista.

En el segundo acuerdo del documento suscrito por los ci-neastas reunidos el 4 de mayo del 2013 se apunta:

Entendemos por cine cubano el producido a través de mecanismos institucionales, independientes, de coproducción con terceros o de fórmulas mixtas; y como cineastas a todos los creadores, técni-cos y especialistas cubanos de estas artes e industrias que realicen su trabajo dentro o fuera de las instituciones, sean cuales sean sus estéticas, contenidos o afinidades grupales. En consecuencia, es in-dispensable la aprobación del Decreto Ley para el reconocimiento del Creador Audiovisual. Este decreto debe ser enriquecido con todos los complementos legales adicionales que sean necesarios.

Se trata, sin duda, del anuncio de una nueva era para el audiovi-sual realizado en estos tiempos por los cubanos, marcada por la impronta digital, la pérdida de liderazgo del icaic como principal centro productor, y la inserción de esa producción local en la lógica del mercado global. Algo está pasando en el audiovisual realizado por cubanos en este nuevo siglo. Pero desde luego, algo está pasan-do antes en la sociedad, y son los cineastas los que se están encar-gando de dejar el testimonio de nuestro sordo e imparable devenir.

Sobre el autor:

Juan Antonio García Borrero. Miembro de la Asociación Cubana de la Prensa Cinematográfica (Fédération Internationale de la Presse Cinématographique/ fipresci) desde 1999. Creador y Coordinador General de los Talleres Nacio-nales de la Crítica Cinematográfica (1993-2003), considerado el evento teórico

] 25 [

más importante para especialistas en el país. Presidente de la “Cátedra de Pensa-miento Audiovisual Tomás Gutiérrez Alea” (2002), ha ganado en seis ocasiones el premio de Ensayo e Investigación que concede anualmente la Unión de Es-critores y Artistas de Cuba (uneac), así como dos años consecutivos el Premio Nacional de la Crítica Literaria, resultando hasta el momento las únicas ocasio-nes en que se entrega ese galardón a textos sobre cine. En 1990 fundó el cine club Luis Rogelio Nogueras, con sede en la Casa del Jurista de Camaguey. Su investigación Guía crítica del cine cubano de ficción registra por primera vez en un volumen la producción silente, sonora pre-revolucionaria y revolucionaria, incluyendo las realizaciones de los cineclubes de creación, el Taller de Cine de la Asociación Hermanos Saíz, la Escuela Internacional de Cine de San Antonio de los Baños, los Estudios Cinematográficos de las Fuerzas Armadas Revoluciona-rias, los Estudios Cinematográficos de la Televisión, entre otros.

] 27 [

Después del icaic: Los tres imperativos categóricos del audiovisual cubano actual

Dean Luis Reyes

En el año 2000, tras la salida de la presidencia del Instituto Cu-bano del Arte e Industria Cinematográficos de Alfredo Guevara, su fundador e ideólogo fundamental, la institución eje de la cul-tura cinematográfica cubana se vio colocada ante un momento de tránsito. Su nuevo presidente, Omar González, un funciona-rio cultural sin vínculo anterior con el cine, solicitó un estudio etario de los empleados bajo su mando. El resultado arrojó que la edad promedio de los directores de cine en Cuba era de 50 años.

Ante la pregunta obligatoria de “¿quiénes harán las películas cubanas dentro de una década?” sobrevino la convocatoria para organizar una muestra nacional de nuevos realizadores, sin dis-tinción de edad, que pudiera rejuvenecer la cantera de creado-res. Así, en el mismo año 2000 tuvo lugar lo que fue el germen de la actual Muestra Joven. Ella supuso un ágora inevitable para los realizadores jóvenes así como un escenario para los nuevos modos de hacer cine en Cuba. Este es el imperativo geriátrico.

El segundo imperativo fue tecnológico. En 2001, el joven realizador habanero Humberto Padrón se graduó de la Facultad de Medios Audiovisuales del Instituto Superior de Arte de La Habana con una tesis de ficción titulada Video de familia. Este cortometraje causó un impacto nacional enorme. Obtuvo todos

] 28 [

los premios de los concursos locales, el Coral al mejor corto de ficción en el Festival Internacional del Nuevo Cine Latinoame-ricano de La Habana y algunos reconocimientos internaciona-les. Había sido realizado con una cámara digital. Su relato refiere la reunión de una familia cubana para grabar una video-carta dirigida al hijo emigrado. Un tanto en la cuerda de Festen (Tho-mas Vinterberg, 1998), la reunión acaba invocando los demo-nios de un país lleno de prohibiciones y ancestrales autoridades.

La marca de Video de familia se extendió al cine del icaic. Uno de los grandes autores vivos del periodo épico de la dé-cada de 1960, Humberto Solás, autor de clásicos como Lucía (1968), retornó a la dirección tras más de una década sin filmar, y lo hizo en digital. Miel para Oshún (2001) propone también una discusión entre diferentes maneras de entender el proyecto social de la nación, mientras que Barrio Cuba (2005), su obra póstuma, es una alegoría nacional que propone el encuentro de las diferencias en un abrazo de concordia.

Pero mientras la producción del icaic sigue reiterando los temas caros a su estética clásica –el registro de las marcas visibles de una identidad nacional pretendidamente esencial; la constitu-ción simbólica de una comunidad imaginada para la nación; el proyecto de creación de esfera pública con el cine como instru-mento predilecto para incidir en la transformación del especta-dor como sujeto social–, otras propuestas se manifestaban en el ámbito de una producción alternativa al instituto. Ello expresa el tercer imperativo: el temático-estilístico.

En poco más de una década, estos tres imperativos han pro-vocado un cambio sustancial en el panorama de la producción de cine en Cuba. Después de la profunda crisis económica de la década de 1990 y de la desaparición de los subsidios estata-les para la producción de cine –fuente casi absoluta de finan-

] 29 [

ciamiento para el icaic hasta inicios de los 90– el número de películas cubanas de largometraje se redujo considerablemente. No así la producción por otras vías.

En 2005, el propio Humberto Padrón dirigió el primer lar-go de ficción financiado con capital privado. El dueño de un célebre restaurante de La Habana, un grupo de pintores amigos que subastaron obras, más fondos del propio director y la parti-cipación casi gratuita de técnicos y actores, permitieron financiar una película de realismo social titulada Frutas en el café. Fue ese el inicio de una corriente fílmica alternativa intensa y creciente que, trabajando fuera de los centros de producción habituales y sin una legislación adecuada que los reconociera como actores legítimos, han insuflado vitalidad a la cultura fílmica nacional.

Quizás el impacto más decisivo se haya producido en el es-cenario de la no ficción. El documental comienza a manifestarse como un campo sin unidad visible. Al no existir un debate pres-criptivo que imponga tal o cual método de aproximación a los te-mas, todos los estilos y tratamientos conviven sin negarse entre sí.

Una marca destacada a partir de 2006 fue la emergencia de multitud de cortometrajes dedicados al examen de aspectos controvertidos de la realidad social cubana. Haciendo una suer-te de trabajo de contrainformación, estas piezas cobraron signi-ficativo relieve al revelar la falta de consecuencia entre discurso público y vida cotidiana en Cuba. Este conjunto revitalizó la dimensión testimonial del documental cubano. Sus realizado-res privilegian el cine encuesta y la entrevista como herramien-tas, además de un tratamiento reporteril generalizado. Ello dio lugar a un nuevo periodismo que hizo de la cámara digital el dispositivo esencial para mostrar y denunciar. Asuntos como el travestismo, la prostitución, la homosexualidad, la censura, la burocracia y toda clase de exclusiones y marginalidades aflo-

] 30 [

raron, acogiendo a segmentos sociales con reivindicaciones ca-rentes de espacio público donde ventilarse.

Esta tendencia dice adiós a uno de los recursos principales de la retórica del documental social cubano para aliviar la dureza en el tratamiento de esta clase de temas: la argumentación ba-lanceada. Una abrupta necesidad de denunciar, marcada por el desencanto con las dilaciones del wishful thinking de los cineas-tas precedentes, dio lugar a una corriente documental de inten-ción activista, que causó desconcierto en los censores y provocó mucha ojeriza. Los temas básicos de la oleada de la segunda mi-tad de la década tocaban en su mayoría cuestiones relacionados con la administración del espacio público nacional.

La búsqueda de respuestas propias para cuestiones de su universo social de pertenencia hace que los documentalistas jó-venes se concentren en la elaboración de tesis a partir de darle voz al otro, y a que atiendan razonamientos no tendientes a la armonía, a que excluyan de sus versiones la opinión oficial, o incluso a que la contravengan. Así, en De generación (Aram Vidal, 2006), un puñado de jóvenes hace un balance desencan-tado, pragmático y nihilista de sus posturas ante la sociedad, en abierta discusión con las expectativas que ésta ha puesto en ellos. Mientras que Revolution (Mayckell Pedrero, 2009) abor-da el trabajo de Los Aldeanos, un dúo de hip hop de postura contracultural, a través de cuya historia se muestran las costuras del consenso nacional en torno a temas que afectan la colecti-vidad, como es la gestión del disenso político, y se exhibe la emergencia de un discurso cultural de la marginalidad y el peso de las subculturas juveniles de contestación.

Por su parte, Manuel Zayas, quien había dirigido un primer documental dedicado a la figura olvidada y a la obra silenciada del destacado documentalista Nicolás Guillén Landrián, Café

] 31 [

con leche (2003), examina las marcas sobre el campo cultural de las décadas de 1960 y 1970 de la exclusión de intelectua-les homosexuales en Seres extravagantes. Teniendo a Conducta impropia (Néstor Almendros, Orlando Jiménez Leal, 1983) como referente central, su indagación incluye la reelaboración de archivos y mucho material testimonial propio. Esta obra se suma a otras que por el periodo indagan en aspectos o figuras excluidas del canon cultural cubano por diversas razones.

También ocurre la eclosión de piezas de artistas formados en la academia y que usan las herramientas audiovisuales para prácticas de documentación e indagación antropológica. Un caso especial es el grupo de creadores asociados al proyecto de la Cátedra de Arte Conducta organizada por la artista Tania Bru-guera. De ese grupo de creadores cercanos a la intervención, el videoarte y la no ficción en general, destaca Reconstruyendo al héroe (Javier Castro, 2007), una aproximación a la violencia so-cial con las herramientas de la indagación etnográfica, así como una sutil inversión del canon nacionalista: las 26 madres que cuentan a cámara las heridas recibidas por sus hijos en reyertas públicas suman la misma cantidad de marcas que el héroe de la independencia cubana en la guerra contra España, el general mulato Antonio Maceo, llevaba en su cuerpo al morir.

Esta inclinación por reseñar las subjetividades marginales, apenas atendidas en el audiovisual cubano, en general atento a referir historias ejemplares, explica tanto el tema como el tra-tamiento escogido por Damián Sainz en De agua dulce (2011). Las confesiones de su personaje y las faenas de pesca en que lo observamos progresar muestran una zona oscura del carácter humano desde un estilo que no se inmuta ni pide ver más.

El rasgo esencial de los desplazamientos producidos a través de la década consiste en la problematización del sujeto popular.

] 32 [

La gente vuelve al centro de las preocupaciones de la documen-talística nacional, subrayando una tendencia hacia la etnografía experimental. Este término se ha vuelto común para una zona de estudios multidisciplinarios derivada de la teoría antropoló-gica poscolonial, según Catherine Russell, como

una manera de referir el discurso que circunvala el empiris-mo y la objetividad convencionalmente ligados a la etnografía (…) Especialmente en situaciones de observación entre cultu-ras, muchos filmes adquieren aspectos etnográficos, en tanto la “etnografía” se vuelve menos una práctica científica y más un método crítico, un medio para “leer” la cultura en vez de re-presentarla transparentada (…) La etnografía experimental no se propone como una nueva categoría de práctica fílmica, sino como una incursión metodológica de la estética sobre la repre-sentación cultural, una colisión de teoría social y experimenta-ción formal.1

La etnografía experimental subvertiría la ciencia etnográfica tradicional para transformarla, en manos del cine, en una es-tructura crítica que traslada su centro de interés de las preocu-paciones formales al reconocimiento del rol y posición cultural del cineasta. Lo cual indica la tensión moral que recorre esta corriente; su interés por la gente en situación difícil se debate contra la hipocresía de la porno-miseria disfrazada de huma-nismo. Por ello, estas obras no desfallecen ante la elección del tema indispensable, sino que lo reelaboran lingüísticamente y,

1 Catherine Russell (1999). Experimental Ethnography: The Work of Film in the Age of Video, Durham nc: Duke University Press.

] 33 [

sobre todo, incorporan al destinatario en su trabajo. Su énfasis en tratamientos descriptivos consigue introducir al espectador en un universo ajeno, le permiten percibir la sensación de un ambiente, para someterlo al estremecimiento del estuve allí.

La pieza audiovisual operaría entonces como laboratorio donde poner bajo escrutinio tanto las políticas de representa-ción como las convenciones del cine de carácter observacional. Dentro de un emplazamiento cultural tan específico como el del documentalista frente a un sujeto popular con un ámbito de representación complejo y ajeno, la autoconciencia de la pieza resultante y el reconocimiento de esta complejidad se transforman en atributos expresivo productivos desde el pun-to de vista de lenguaje, pero sobre todo desde la perspectiva ética.

Esta tendencia hacia la reelaboración del material testimo-nial dentro de rangos que no dejan prosperar el ilusionismo del documental institucional, el cual favorece la ocultación de su hechura ficticia, estimula una reflexividad apoyada en la am-bigüedad resultante. En el caso cubano, la reflexividad suele dirigirse a poner en cuestión la postura que ocluye la partici-pación del espectador en la construcción de sentido resultante, privilegiando la persuasión por sobre la reflexión. De ahí que se tienda a construir formas dialógicas, que presuponen tomar parte en una experiencia compartida.

Además, esta corriente reflexiva insiste en trabajar sobre el contenido político del género. Por ello, subraya la hechura del documental como constructo, representación. De manera que se hace evidente la toma de distancia frente a la gran tradición del documental testimonial cubano, al alejarse del contenido factual, de lo evidente, y desplazar el énfasis expresivo de lo explícito hacia lo latente.

] 34 [

Un ejemplo es Model Town (Laimir Fano, 2006). Con la intención de establecer un contraste entre el pasado de batey azucarero, administrado como feudo por un empresario esta-dounidense, del actual poblado de Hershey, y el presente de nostalgia y abandono, la pieza construye su discurso desde dos perspectivas simultáneas. Una, de carácter digamos historiográ-fico, rehace el Edén perdido a partir de documentos visuales (fotos, escrituras, rastros de la cultura material del pasado), a los que pone a discutir a través de un montaje paralelo con imágenes del presente.

La segunda es la memoria viva, el cómo evoca un grupo de ancianos, principales testimoniantes, su infancia en un mundo ideal. Estos elementos permiten a Laimir tejer, a través de la voz de sus entrevistados, una especie de red de confesiones, donde se entremezclan nostalgia e idealización. De ahí que la textura formal del documental quiera reproducir por la fuerza aque-llo que es imposible registrar como documento, aquello que, por permanecer sin registro audiovisual o por existir reducidas fuentes documentales con que reconstruirlo, se ha vuelto invi-sible. Estamos ante una manipulación del material para hacer una reflexión en torno al artefacto de la memoria humana y sobre cómo se la construye.

Nos quedamos (Armando Capó, 2009) procede a un ex-trañamiento mayor. Todo el material testimonial en esta pieza está en función de una meditación en torno a la persistencia humana ante el caos, la ruina y el desastre. Sus personajes se enfrentan a fuerzas irracionales que no pueden entender o do-minar. Ante ellas, apenas les queda la resignación y la espera. Capó construye su pieza bajo un criterio de manipulación del lenguaje fílmico y de ensayo de un criterio de montaje de van-guardia.

] 35 [

También Ariagna Fajardo hace en Papalotes (2010) un do-cumental de montaje. Aunque se trate de una obra realizada dentro del proyecto de televisión comunitaria que desde hace veinte años documenta la vida de una zona de la Sierra Maes-tra, mayor grupo montañoso de Cuba, su tratamiento se dis-tancia de los métodos reporteriles.

En Papalotes, un día en la vida de un puñado de personas se articula a través de un complejo y bien hilvanado montaje dialéctico. Pero su principal interés es la gente. La registra casi siempre desde muy cerca. Busca sus rostros y ademanes a la hora de emprender tareas cotidianas: comer, esperar, trabajar. Hay un respeto casi diríase ritual ante la imagen del otro. Un asunto que está al centro de lo mejor del documental cubano que se tomó como algo imprescindible negociar la represen-tación del subalterno social, del humilde, el pobre –véase la obra realizada durante los 60 por Sara Gómez, Nicolás Guillén Landrián y Bernabé Hernández para identificar esta ambición.

Esta necesidad de la no ficción cubana por romper todos los moldes encuentra en La ilusión (Susana Barriga, 2008) su con-sumación. Una vez más, una cámara forma parte de una crisis familiar. Susana Barriga viajó al Reino Unido buscando a su desconocido padre. La ilusión es el resultado de esa búsqueda. Su proyecto documental posee todos los rasgos de un performan-ce, de una auto-representación. Susana encuentra finalmente a su padre, incluyéndolo en un corto en el que lo testimonial marca profundamente la experiencia estética. La ilusión nació como un proyecto de reconstrucción biográfica.

Nuevamente, la cámara de video portátil juega un papel fundamental. Mientras Susana espera la llegada de su padre, enciende el aparato. Entonces graba el vidrio de la puerta del apartamento iluminado, los sonidos del lugar, la entrada de la

] 36 [

escalera, la calle de abajo. Una suerte de confusión la lleva a capturar cada detalle, para aprehender la sagrada presencia, que no se ha revelado aún, mediante las herramientas que le son fa-miliares. Una vez adentro, después del primer saludo, la cámara sigue rodando al interior del bolso. No le ha dicho al hombre que viene con el fin de realizar un documental.

Nunca logramos ver al padre por completo, ni siquiera su ros-tro. Sólo una figura borrosa, cuando entra en el encuadre, deja fue-ra su torso y sus piernas. Todo sugiere que observamos una escena capturada por una cámara escondida; los eventos se comparten sin reservas. Susana nunca llega a decirle al hombre que ha venido a filmarlo, pero los resultados del trabajo se revelan ante nosotros.

La película de Susana Barriga surge de una intención indi-vidual. Su acto privado, sin embargo, deviene un acto de me-moria colectiva. Presupone, en el caso cubano, una propuesta que persigue una articulación de nuestras propias formas de la memoria para transformar la formación el dolor propio en un ingrediente de la memoria colectiva. En otras palabras, la fun-dación de un nuevo contrato social requiere una nueva ley que rija la memoria y, de allí, la importancia de la negociación de la historia en el futuro de la cultura audiovisual cubana.

La ilusión pone en evidencia una noción distinguible desde inicios de década en nuestro audiovisual, cuando se hace visi-ble que aquello que atrae hacia el documental tiene menos que ver con representaciones fílmicas auténticas y reales que con una democratizada retórica de lo real, donde lo histórico está asenta-do en contextos individuales, de inmediatez. Ello, como conse-cuencia de la mediatización social generalizable a las sociedades contemporáneas, donde, como precisa Paul Arthur, “cada vida es entendida como intrínsecamente una producción-en-desarrollo cuyos idiomas son modelados por un espectro de prácticas do-

] 37 [

cumentales, desde las noticias producidas por testigos a través de cámaras en teléfonos celulares hasta cándidos videos sexuales.”2

También en la animación alternativa se ha producido un salto al vacío. Mientras que los Estudios de Animación icaic han crecido en su producción y sus contenidos, siguen siendo mayoritariamente dirigidos a los niños, con fines didácticos, el rasgo característico de la creación alternativa es rehuir el didac-tismo, empleando todas las técnicas disponibles. Sus intereses se desplazan lejos de la acción o el humor, proponiendo obras donde la forma animada aporta soluciones de lenguaje imposi-bles a través de un medio diferente.

Windows xy (Yimit Ramírez, 2009) implica para la anima-ción cubana un gesto similar al que supone en la historia del me-dio Duck Amuck (Chuck Jones, 1953). Su textualidad descansa en la auto-referencialidad y en el trabajo de deconstrucción que propone para la animación 3D. La elección formal de Yimit es visibilizar el proceso de producción y proponerlo como el relato mismo, en una exploración autoconsciente de las posibilidades expresivas que ofrecen las nuevas tecnologías de creación de ima-gen. Es, además, un ejemplo de diseño complejo de banda sono-ra, rasgo extensible a toda la obra de Ramírez y que resalta en un ambiente como el de la animación cubana, donde el trabajo de sonido casi siempre queda reducido a montar diálogos y música.

A partir de esta clase de ejemplos se hace imposible seguir hablando en Cuba de la animación como un género preferible-mente para niños o que facilita contar historias realistas imprac-ticables o incosteables a través de registro fotográfico. Propuestas complejas y muy elaboradas se han visto en los últimos tiempos,

2 Paul Arthur, “Extreme makeover: the changing face of documentary”, Cineaste, vol. xxx, nr. 3, Summer 2005, pp. 18-23.

] 38 [

como La segunda muerte del hombre útil (Adrián Replansky, 2010). Un grupo de refrigeradores de fabricación soviética, olvi-dados en un oscuro almacén, cumplen un ritual de secta secreta. Estamos ante obras que, como la mayoría de las producidas en la animación alternativa, responden a la agenda de autores de formación disímil –diseño gráfico, ciencias de la computación, artes plásticas– y que concurren a este ámbito de creación por razones de agenda personal.

También fruto de iniciativas de producción absolutamente ajenas a las instituciones tradicionales es La escritura y el desastre (Raydel Araoz, 2008). Este mediometraje de ficción usa rasgos de ciencia ficción, de meditación en torno al destino del creador artístico en una sociedad en crisis y de elementos del discurso fílmico de vanguardia, para deslizar un comentario en torno a la persistencia del paradigma cultural moderno. En el mismo, el artista ejercería la función de conciencia crítica de la sociedad y la obra de arte asumiría la función de desplazamiento simbólico que aspira a abarcar en su estructura formal la totalidad social.

Este gesto de Araoz supone la adquisición por el audiovisual cubano de la agenda intelectual de grupos de creadores jóvenes de la Cuba actual, herederos de los proyectos literarios experi-mentales –manifiestos sobre todo en la poesía, la narrativa y el ensayo, más algunas experiencias de arte acción e intervención social– surgidos en la década de 1980 y vigentes durante los 90. La escritura y el desastre, además de traer a Blanchot a una hipoté-tica Habana pos-humana, es un comentario irónico y de honesto y bien articulado amateurismo acerca de la aspiración mesiánica de la clase intelectual cubana.

Una agenda que se manifiesta con fuerza en la producción alternativa es además la reivindicación de una mirada de gé-nero. El tema femenino, consustancial a buena parte del cine

] 39 [

cubano, recibe ahora tratamientos mucho más autoconscientes y advertidos de la necesidad de expresar aspectos de la subjetivi-dad que trasciendan la idea de la mujer como ser social. Varias mujeres en activo dentro de la ficción alternativa proponen en-foques llenos de originalidad y activismo.

Ese es el caso de Patricia Ramos, que en El patio de mi casa (2007) ofrece una sutil estampa de la familia cubana articulada en torno de la mujer. Pero en vez de proponer en este corto una mirada de ambición sociológica, Patricia opta por recrear a tra-vés de las imágenes el imaginario imposible de una existencia aparte de lo cotidiano. Los sueños idealizados de los personajes chocan con la dura realidad de la subsistencia. A través de una puesta en escena minimalista y el privilegio de una atmósfera emocional apoyada en el manejo sutil de la sugerencia ambien-tal, las texturas, el color y las luminosidades filtradas, Patricia construye un mundo sinestésico, lleno de vida interior.

Estos ejercicios de estilo carentes del peso argumental ha-bitual del cine cubano, que transitan más por el cómo que por el qué se cuenta, que confían en la naturaleza de lo visible hasta el punto de dejarnos solamente con los cuerpos, los gestos, los si-lencios, forma parte del repertorio de una parte del audiovisual cubano de hoy. El documental ha explorado conscientemen-te esta clase de tratamiento –Suite Habana (Fernando Pérez, 2003) sería el paradigma de una corriente que atraviesa la no ficción de la última década, en pos de expresar lo inmanente social. Pero el recurso de cargar de sentido el fuera de campo, a costa de reducir lo que vemos en pantalla, ha sido el medio favorito de Carlos Machado.

La piscina es su opera prima. Su sinopsis: un profesor de natación pasa un día completo con cuatro adolescentes afecta-dos por diversos hándicaps. El relato es escueto en lo que a pe-

] 40 [

ripecias dramáticas respecta (empleo drama en el sentido que le otorga su origen etimológico y uso corriente en el teatro griego clásico: acción). Machado emplea como núcleo de su trabajo el “fuera de campo”, el cual opera como ausencia-presencia que se activa y funciona como metáfora. O sea, como fuera de campo alegórico, espacio de sentido omitido que densifica aquello que el registro hace visible.

La piscina se comporta como un fragmento, una anécdo-ta casi, cuyo propósito es sostener una tensión de ambición naturalista que aspira a purgar de contenido dramático su es-tructura. Su guionista, Abel Arcos, se resiste a llenar el vacío sostenido de este universo, con peripecias o curvas de interés para la ambición escópica de un espectador amaestrado para ir al cine a ver suceder cosas. Desde tales presupuestos, el estilo de la obra se desempeña como un duelo con lo ausente: el cine convencional. El cine cubano, incluso.

De ahí que esta obra acabe siendo un discurso doble: sobre la alteridad del ser humano que no pertenece al universo de lo inscrito, lo comprensible, y sobre un cine que quiere dejar de ser literatura y teatro filmado, que se rehúsa a dar explicaciones, que no recurre a marcas locales o valores culturales indígenas, que fomenta un naturalismo que aspira a la abstracción y ofrece como única respuesta el rostro desnudo de la imagen-tiempo.

Con semejante elipsis de sentido, La piscina, que no apa-renta ambiciones de trascendencia, se transforma en un acto inaugural enorme para el audiovisual cubano. Porque al fondo de esa búsqueda está la vuelta a la utopía de un cine que piensa al espectador al tiempo que se piensa a sí mismo.

La piscina es además el ejemplo más claro de las mutaciones que se producen en la cultura audiovisual cubana actual y en sus referentes. La opción de Machado por un estilo contemplativo

] 41 [

y antinarrativo responde a la nueva cinefilia de los realizadores cubanos jóvenes –abiertos al cine europeo de autor y a la obra de realizadores de cinematografías periféricas (China, Portugal, Filipinas, Rumanía), además de a su familiaridad con formas de producción del cine independiente y de bajo presupuesto.

Esta clase de negociaciones con estilos y géneros extraños a la tradición cinematográfica local explica la aparición de obras como Juan de los Muertos (Alejandro Brugués, 2011), que im-porta el cine de zombis y lo cubaniza. Y también es el origen del particular estilo y ámbito temático en que se inscribe Molina’s Ferozz (Jorge Molina, 2010). Su realizador es el único autor de cine de culto de Cuba, como también el mayor, más duradero y persistente transgresor de los cauces temáticos y de los para-digmas morales de la cinematografía cubana.

Molina ha sostenido una intermitente producción inde-pendiente desde inicios de la década de 1990. Los referentes de su cine eran desde entonces el noire hollywoodense, la serie B, el nuevo cine de Hong Kong, el sexploitation, el horror clásico y posmoderno, el cine de la transgresión neoyorkino, Jess Fran-co, Russ Meyer, Ze de Caixao, Nick Zedd, entre otros tantos. Su cine es de una irónica autoreferencia que emplea motivos extremos y ofrece escenas de sexo y violencia explícitos.

Casi veinte años tomó a Molina levantar su primer pro-yecto de largo. Éste mismo es una versión perversa del cuento de la Caperucita roja, localizado en un anacrónico campo cu-bano. Entre el bucolismo de la fotografía y la sencillez de su puesta en escena se desenvuelven un grupo de personajes de libido autodestructiva. Molina se desplaza, sin abandonar sus referentes fílmicos, a través de una vasta tradición de literatura y tradiciones populares cubanas nada canónicas que reelaboran el absurdo y las pulsiones del cuerpo. Ferozz abraza, por el lado

] 42 [

literario, los legados de Samuel Feijóo, Virgilio Piñera y Pedro Juan Gutiérrez, entre otros.

El cine de Molina es el ejemplo más extremo de tejido de una nueva tradición para el cine cubano, que toma distancia de sus referentes canónicos. Pero la ruptura que supone no es sólo temática. El cine de Molina propone además una negación del proyecto moralizante del cine de la revolución socialista, de sus modelos ejemplares y estructuras clásicas. En su cine se elude la creencia ciega en un proyecto humano de felicidad y candor. Sus personajes son seres atormentados por urgencias carnales, por deseos irracionales y pulsiones de muerte. Nada que ver con el proyecto del hombre nuevo.

Las rupturas con la tradición del actual cine nacional obe-decen además a las negociaciones con mecanismos globales de gestión y producción de cine. Un proyecto novedoso para Cuba como es el sello independiente Producciones de la Quin-ta Avenida –que produjera Juan de los Muertos– opera a través de la búsqueda de fondos y ayudas a la producción en festivales como Rotterdam y en inversiones multinacionales. De ahí que sus productos tengan una orientación mucho más definida por el diálogo con entornos trasnacionales de intercambio.

Un ejemplo de qué clase de configuración pudiera tener una producción originada dentro de tales coordenadas es Me-laza (Carlos Lechuga, 2012). Se trata de otra opera prima que, sin tomar distancia de la tradición temática del cine cubano, muestra un panorama de cómo podría definirse un cine cuba-no posclásico. O sea, una corriente que, sin romper del todo con las marcas de la tradición de la cinematografía local, pro-ponga desvíos y carreteras secundarias.

En Melaza hay un espacio físico que sobredetermina todo lo que en su trama sucede. Se trata de un paisaje, una territo-

] 43 [

rialidad preexistente a los personajes y sus conflictos. Reinando sobre tal geografía, un central azucarero desmantelado, clausu-rado luego de la enésima reestructuración macroeconómica. Lo que otrora fue el eje de la prosperidad y mantra de un estilo de vida, de rituales ahora desaparecidos, observa impasible cómo sobreviven los seres ubicados al final de la cadena productiva de la economía: la gente.

Los personajes de Melaza son, a un tiempo, espectros de este paraje fantasmal y autómatas que tratan de sacudir de su día a día la derrota que impone esa mole olvidada y herrum-brosa que rige muda sobre sus vidas. Aldo y Mónica sobreviven a todo poniendo su relación por delante. Son una pareja joven, hermosa y lozana, que defiende una convivencia donde falta de todo, menos cariño. Su esfera social es parte de ese universo inane: ella hace inventario y revisa el funcionamiento de las maquinarias del central, adonde va a “trabajar” cada jornada; él enseña a un puñado de niños en una escuelita desconchada y da clases de natación en una alberca vacía.

En términos de fábula, estamos ante una nueva historia de supervivencia típica del cine nacional en las pasadas dos déca-das: Aldo y Mónica deben improvisar, andar sobre el filo de la legalidad, simular, conspirar, aprovecharse del débil, hacer esto y aquello, para comer decentemente. Pero en términos de construcción de sentido audiovisual, Melaza supone retomar la obsesión con el vacío de un área adelantada del cine nacional re-ciente. Esa persistencia sobre el vacío es la marca dramática más noble de los personajes de Melaza. Y la noción de lo ausente aca-ba transformándose en el eje del método expresivo de Lechuga.

Con este no estamos ante un filme que busca desdramati-zar, sino que maniobra a partir de elipsis, de severas omisiones. Primeramente, el espacio físico del relato, de donde se ausenta

] 44 [

un propósito, una teleología. Si acaso, hay un ruido de fondo que anuncia su existencia como eco: un periódico que exhibe consignas en su portada; alguna pintada de contenido político carcomida sobre una pared; un vehículo con amplificación que difunde el llamado a algún acto de masas.

Esta tendencia hacia ubicar las marcas contextuales fuera de la representación se asemejan al tratamiento de la realidad sociopolítica nacional de películas como Platform (2000) o Still Life (2006), del director chino Jia Zhangke. En ellas se elabo-ran fábulas donde las grandes transformaciones socioeconómi-cas de su país son refractadas a través de la vida cotidiana de personajes que cruzan la época como cualquier hijo de vecino: sin reparar en el valor memorial de la experiencia del presente.

En el caso cubano, aquello que se imponía como color local o valor testimonial en nuestra cinematografía, cede paso a un enfoque menos apegado al referente. El peso documental de Melaza es manifiesto: fue rodada en el batey del central Habana Libre, en la antigua provincia de la Habana, y una de sus vir-tudes es aprovechar para sus fines ese escenario tal como está. Pero, si obviamos toda esa información, estaremos ante un dis-positivo fílmico casi atemporal, un probable no-lugar. Lechuga nos deja a solas con gente que pasa necesidad porque los sobre-determina una orden de cosas que no dominan ni entienden, y que aun así buscan ser felices, a costa incluso de su integridad.

Melaza fue apoyada por el festival holandés de Rotterdam y es el resultado de fuentes de financiamiento ajenas a las insti-tuciones cubanas. Su régimen expresivo obedece a una cultura global de cine de autor que se manifiesta más allá de lo tradicio-nalmente entendido bajo el criterio de “cines nacionales”, para en cambio dar lugar a un estilo internacional reconocido bajo la agenda legitimadora de redes de festivales sobre todo europeos.

] 45 [

A pesar de lo anterior, Melaza guarda mucha relación con las tendencias del audiovisual cubano de la pasada década en su trabajo sobre las marcas de lo social, alejándose del paradigma del cine del icaic. El interés por un tratamiento descriptivo, la evasión de los grandes temas, del acento normativo, más la toma de distancia de un alineamiento ideológico específico y manifiesto, caracteriza a un grupo de realizadores más atento al diseño de atmósferas que de fábulas cerradas.

No obstante, el deseo de elaborar versiones particulares de la Historia se sostiene, ya fuere a través de historias cotidianas de aspiración minimalista o de piezas más ambiciosas. Ese es el caso de Memorias del desarrollo (Miguel Coyula, 2010). Construido como un texto modular, éste encuentra su organicidad en una radicalización del método collage.3 Su empleo se observa en dos aspectos: primero, la historia, que incluye la fragmentación permanente de la experiencia del personaje principal, un nuevo Sergio inspirado en aquél de Memorias del subdesarrollo (Tomás Gutiérrez Alea, 1968),4 quien observa la realidad de modo alea-

3 Me refiero al uso de collage desarrollado por los vanguardistas del principio del siglo xx, que crearon un método informado por una simulta-neidad en composiciones heterogéneas. En Visionary Film, su estudio clá-sico de la vanguardia norteamericana, P. Adams Sitney hace comentarios claros sobre el cine de Bruce Conner: “The natural irony of the collage film, which calls attention to the fact that each element quoted in the new synthesis was once part of another whole, thereby underlining its status as a piece of the film, creates a distance between the image depicted and our experience of it. Montage is the mediator of collage.” (253)

4 De hecho, Memorias del desarrollo, de Edmundo Desnoes, publicada en 2007, no es una continuación pura de la historia del intelectual burgués de la novela anterior sino es la búsqueda de algunos de sus tópicos en un contexto biográfico diferente, de una realidad alternativa.

] 46 [

torio y relacional, elaborando a partir de los fragmentos disper-sos de experiencias que conforman el ecosistema emotivo donde cada evento es modificado, alterado e influido por sus valores y su visión del mundo. En segundo lugar, el discurso, estrecha-mente ligado a la dimensión diegética, aunque también forma parte del ejercicio creativo de una experiencia audiovisual úni-ca. De allí que Coyula hilvane su obra con materiales disímiles: imágenes tomadas de la prensa, el arte clásico o moderno, cine documental, video juegos, textos, animación, repentinas actua-ciones en escenas reales y cabales puestas en escena.

La estética de las películas de Coyula responde a la interrup-ción lingüística que ocurre en los relatos visuales basados en la imagen electrónica. El director propone un montaje ligeramen-te neobarroco, mediante el análisis minucioso de las imágenes y el uso de programas para su manipulación. Las ventanas dentro de ventanas que caracterizan las tomas de Memorias desestabili-zan el uso de cuadros y retículas de la composición visual para exacerbar la movilidad e inestabilidad de los encuadres desarro-llados por la industria fílmica a través de la historia.

Coyula intensifica la sensación de hallarse ante encuadres dentro de encuadres, usando la función de copiar y pegar, típi-ca del collage e intensificado con el uso de los ordenadores. Esta labor de sampling, que nos introduce en el mundo descentrado y autista de los personajes, le permite trabajar con característi-cas fundamentales de la imagen electrónica, según Lev Mano-vich: su reciente densidad y maleabilidad.

El montaje interno usado por Coyula transforma su película en un trabajo de animación. La intervención en los encuadres va desde la manipulación de la luz y el color, hasta una modifica-ción del registro original que alcanza la falsificación. Así recupera el acto ontológico de la filmación: la escritura del movimiento. El

] 47 [

director hace esto a fin de radicalizar algunos rasgos de sus pelícu-las anteriores: la conciencia de trabajar con material grabado y no con la realidad. Según Manovich, para los medios electrónicos, “el tema no es la realidad misma, sino la representación mediáti-ca.”5 De allí el número de referencias y citas que Coyula emplea, desde una postura postmoderna, para analizarlas, reproducirlas y recombinarlas con otros materiales. El salto que ello representa para el cine cubano tiene un sentido similar a aquél momento en el que Godard reconoce la materia prima de la textualidad del cine, aquella en la que y desde la que se escribe y reconstruye.

En términos de la historia, Memorias desarrolla una notable operación. Este Sergio no se considera a sí mismo como un Hom-bre Marcado, aunque lo sea. Podemos ver el estigma a través de su doble condición de extranjero: viene de otro país, Cuba, lo que lo obliga a ofrecer explicaciones ante el hecho de ser evaluado por su sentido simbólico; pero al mismo tiempo, se considera fuera de lugar, viviendo en un ostracismo cínico que lo hace incapaz de establecer vínculos emotivos de cualquier tipo.

Un segmento del prefacio de Memorias ilustra este momen-to: una foto de una tía cariñosa lleva a Sergio a su infancia en Cuba, hacia el final de los 50. Los fragmentos de memoria son reconstruidos constantemente mediante la subjetividad del niño, mostrándonos la tierna relación entre ellos, interrumpi-da por los eventos de un país en guerra. Coyula reconstruye hechos históricos con materiales tomados principalmente de fotos publicadas en la revista Bohemia. El collage de fotos de prensa, publicidad y los más diversos sonidos cuentan la histo-ria de cómo se desarrollan los hechos.

5 Lev Manovich (2001), The Language of New Media: mit, p. 178.

] 48 [

La guerra es, en la mente del niño, un evento distante, con armas de juguete que disparan contra la foto de un tren des-carrilado durante el asalto a Santa Clara, o participa mediante combates foto-animados. Las fotos vuelven a la vida, formando una galería de momentos icónicos en la historia de Cuba, la cual es revisitada sin veneración: las imágenes de la Historia o sus signos gráficos, que rara vez generan emociones de fervor, es lo que perdura. Coyula es parte de una generación para la que lo histórico está basado en la construcción de la propia expe-riencia. Las imágenes de héroes y figuras tutelares no despiertan más exaltación que las figuras de cera de una iglesia.

Aún más notable es el hecho de que Memorias visualiza el proceso de construcción de la memoria. La escena anterior posee el color inequívoco de lo que se evoca. Para enfatizarlo, la escena se tiñe de sepia, tornándose más oscura hacia el final, cuando la tía agoniza en su lecho de muerte. El niño Sergio la mira y sus ojos se pierden en el líquido contenido en un embace colocado cerca de la cama. Este fluido, que posee el color turbio y el espesor del pa-sado, refleja su rostro por primera y única vez. Es una fotografía.

La Historia funciona como una base de datos en la que una reflexibilidad de segundo grado aparece representada, dado que lo que vemos no es la realidad, sino una realidad fotográfica. El modo en que podemos conectar los hechos almacenados allí es un producto de la imaginación que opera del mismo modo que el lenguaje de la conectividad digital, mediante interfaces que gene-ran nuevos significados.

De este modo, la tendencia a construcciones sincrónicas en Memorias es débil. Los referentes no se expresan de modo puro y los límites entre el efecto fotográfico y las intervenciones son inestables. Por otro lado, se propicia la hibridación, la transfor-

] 49 [

mación perenne y la intersección se ven estimuladas tal como la memoria funciona mediante vínculos rizomáticos.

Esta ruptura del patrón naturalista, facilitado por el reflejo parasitario del soporte del celuloide y la grabación mecánica, los cuales sugieren la transparencia y la fidelidad del referente, presupone la muerte del gesto memorialista del cine cubano clásico. En lugar de favorecer un arte indexial y mimético, se fa-vorecen estrategias analíticas. La realidad no pertenece a esque-mas fijos, sino que es elástica y flexible. Su representación no deriva su esencia de la fidelidad (como lo pretende la raciona-lidad mecanicista), sino, cuando mucho, de la interpretación. Esta nueva estética propone un estudio de la mirada más que un reflejo del mundo.

No puedo dejar de advertir la semejanza que la actual co-yuntura del audiovisual cubano guarda con aquella en la cual, frente al Hollywood cansino y formulaico de los años setenta, se rebeló una generación dividida entre un grupo que produjo un nuevo pacto para el artificio y la ilusión cinematográfica, con lo cual refundó la industria (de la mano de Spielberg o Lucas), y otro ansioso por desplegar la autoría en distintas di-recciones (Coppola, Altman, Cassavetes, Scorsese). Así nació lo que la historiografía del cine denomina el Nuevo Hollywood. Supongamos que el gesto ha sido ejecutado ahora mismo para la fundación de un cine cubano posclásico: por un lado, Juan de los Muertos reelabora la alegoría nacionalista conectándola con un subgénero del cine universal –la película de zombis. Por el otro, Memorias del desarrollo, La piscina y Melaza replantean, sin las manías retóricas habituales, el eje ideológico del cine cu-bano de la revolución socialista: el individuo y su circunstancia, que es como decir su cine.

] 50 [

Sobre el autor:

Dean Luis Reyes (Trinidad, Sancti Spiritus, 1972). Crítico y ensayista. Fun-da, junto a Julio García Espinosa y Víctor Fowler Calzada, la revista electró-nica Miradas (www.eictv.org/miradas), de la Escuela Internacional de Cine y Televisión de San Antonio de los Baños (eictv), de la cual fue editor hasta 2007. Entre 2000 y 2005 fue miembro del comité organizador de la I Muestra Nacional del Audiovisual Joven (Ciudad de La Habana, noviembre de 2000) y de la II , III y IV Muestras Nacionales de Nuevos Realizadores (Ciudad de La Habana, febrero de 2003, 2004 y 2005, respectivamente). Desde 2000 es jurado anual de los Premios Lucas, concurso nacional del video clip cubano. Ha merecido el Premio Caracol de la Unión Nacional de Escritores y Artistas de Cuba en la categoría de crítica sobre audiovisual en 2003, 2008, 2009 y 2012. Desde 2005 escribe y conduce el programa televisivo de frecuencia mensual Secuencia Crítica (Canal Habana, primer martes del mes, 8:45 pm), donde hace comentarios sobre el audiovisual cubano contemporáneo. Entre 2007 y 2010 ejerció como Coordinador de la Cátedra de Humanidades de la eictv, donde ha impartido asignaturas como Problemas de estética de la animación, Apreciación de la imagen, Teoría del cine y Análisis del filme, entre otros. Tiene publicados Contra el documento (Editorial Cauce, Cuba, 2005), La mirada bajo asedio. El documental reflexivo cubano (Editorial Orien-te, Cuba, 2012). De inminente aparición, Werner Herzog: la búsqueda de la imagen extática (Nobuko, Buenos Aires, 2012).

] 51 [

Cine dependiente, cine pendiente

Miguel Coyula

Creo que la utopía de un cine de ficción verdaderamente in-dependiente –como cualquier utopía– no existe, siempre de-pendes de actores o de favores cuando menos. Pero hablando en términos de industria, es cierto que se ha incrementado la producción independiente desde un punto de vista económico, pero no siempre desde el contenido y forma. Muchas veces el cine independiente es concebido como un vehículo para darse a conocer en la industria y no así como una expresión genuina, sin filtros creativos.

Para mí el cine es la salvación. Un arte verdaderamente inde-pendiente es lo único sobre lo que podemos tener control absolu-to. Es una obsesión. En mi caso es bueno que me interese el arte y no la política, de otra forma probablemente sería un dictador. La ventaja de tener un control total de los medios de producción es envidiable. La originalidad es algo muy difícil pero tampoco es necesaria. Lo importante es absorber tantas influencias para que nazca originalidad de una hibridez extrema.

Hoy en día se hace difícil encontrar algo que sea original. Por ejemplo, ahora se ha puesto de moda el minimalismo en cine de arte de América Latina, los planos largos, ausencia de música incidental o de estilizaciones extremas en la imagen, el tempo narrativo contemplativo, que es algo que hacía el cine

] 52 [

europeo hace 40 años. Conste que creo definitivamente en las influencias para formar un lenguaje de hibrideces al límite. Pero no creo en la hegemonía de una moda, aunque sea cine de arte. Cuando empiezo a ver varias películas “de vanguardia” en la misma cuerda, me doy cuenta de que algo no anda bien. El melodrama en el cine de arte prácticamente se ha desechado, cualquier tipo de sentimiento sufre el destino de una esteriliza-ción, como adolescentes ocultando sus emociones por miedo a dejar de ser cool. Creo que vivimos en un momento muy blan-do donde lo políticamente correcto ha permeado gran parte del cine contemporáneo. Me refiero a las “películas de festivales” que muchas veces se diseñan de manera calculadora pensando en el público al que van dirigidas de acuerdo a la moda impe-rante. Esto es normal por parte de las personas que invierten el dinero en el proyecto, pero es perturbador cuando los propios realizadores discuten estos términos como factor determinante en el resultado final. Lo cierto es que si una obra cinemato-gráfica es sincera, siempre hallará una audiencia, aunque sea pequeña. Hay cineastas que filman para ganar dinero, otros que filman para festivales y otros que filman porque no tienen otra salida que vomitar sus películas desde el subconsciente, sacár-selas de adentro, exorcizárselas. No digo que los festivales y el dinero vengan mal. Pero si es ese el objetivo, estamos hablando en ambos casos de un cine dependiente.

Muchos aprecian el formato digital como alternativa barata al cine. Pocos veneran las características que lo hacen distinto. Creo que la profundidad del campo en el formato digital me parece un logro increíble de la tecnología: el impacto de un ros-tro lleno de arrugas y poros en híper nitidez de alta definición, al igual que el fondo que ya deja de ser fondo por estar en foco perfecto, el barroquismo de un plano donde todos sus elemen-

] 53 [

tos estén en foco, sin grano, para que el espectador elija a donde mirar y pueda así construir una interpretación más compleja de la imagen. Gregg Toland se extenuaba por lograr esto en el Ciudadano Kane. Ahora, 70 años más tarde, la tecnología lo permite y sin embargo los cineastas se matan por tener menos profundidad de campo, desenfocar el fondo, desaturar los co-lores, y quitarle nitidez a la imagen. Todo para que al preguntar uno la razón conceptual de tal decisión estética le contesten “porque así parece más cine”. Otras veces el video digital se ha malinterpretado mucho como idea de que su estética debe ser sucia, cámara en mano, foco y diafragma en automático. Basta de dogmas.

No hay nada más triste que un joven haciendo cine “viejo” para ser asimilado por la industria. No hay nada más triste que reconocer las fórmulas del “género Sundance”, o del “género Cannes” en una película. Me viene a la mente ahora algo que dijo Godard: “la cultura es norma, el arte es excepción.” Cierto que festivales como Sundance y Cannes programan películas más inteligentes que la media de Hollywood, pero por lo gene-ral evitan un cine verdaderamente incómodo. Es triste pues la responsabilidad de un festival hoy en día (salvando algunas ex-cepciones) parece ser más asegurar el cierto mínimo de interés comercial que no ahuyente a sus patrocinadores, y la corrección política de sus programas que asegurará un público comprome-tido con causas. Interesa mucho más todo esto y mucho menos la integridad artística del proyecto.

Es culpa de los cineastas también. Creo que actualmente podemos encontrar un atrevimiento en el contenido pero no tanto en la forma. Temas francamente incómodos son de al-guna manera suavizados por la forma. Una puesta en escena perezosa, en piloto automático. Como si la memoria fílmica

] 54 [