Status, Caste, and Market in a Changing Indian Village

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of Status, Caste, and Market in a Changing Indian Village

Status, Caste, and Market in a ChangingIndian Village

RAM MANOHAR VIKASROHIT VARMANRUSSELL W. BELK

When social and economic conditions change dramatically, status hierarchies inplace for hundreds of years can crumble as marketization destabilizes once rigidboundaries. This study examines such changes in symbolic power through an eth-nographic study of a village in North India. Marketization and accompanying pri-vatization do not create an independent sphere where only money matters, butdue to a mix of new socioeconomic motives, they produce new social obligations,contests, and solidarities. These findings call into question the emphasis in con-sumer research on top-down class emulation as an essential characteristic of sta-tus hierarchies. This study offers insights into sharing as a means of enacting andreshaping symbolic power within a status hierarchy. A new order based on mar-kets and consumption is disrupting the old order based on caste. As the old moralorder dissolves, so do the old status hierarchies, obligations, dispositions, andnorms of sharing that held the village together for centuries. In the microcosm ofthese gains and losses, we may see something of the broader social and eco-nomic changes taking place throughout India and other industrializing countries.

Keywords: status, symbolic power, marketization, sharing, caste

In recent years, several scholars have closely examinedthe spread of markets and consumer culture in India

(e.g., Askegaard and Eckhardt 2012; Derne, Sharma, andSethi 2014; Eckhardt and Mahi 2012; Mathur 2014;Mazzarella 2003; Nakassis 2012; Pandey 2014; Srivastava2014; Varman and Belk 2008, 2009, 2012). Yet the impactof markets on social hierarchies in India remains

underexamined. We study marketization or the spread ofmarket forces (McAlexander et al. 2014) and related pri-vatization and individualization in a village in North Indiain order to answer the underexamined question of how ac-tors holding different status positions respond to disruptionin an orthodox social order.

Although markets have existed in India for thousands ofyears, for a considerable part of this period market accessand roles were defined by status positions within caste or-ders (Fuller 1989; Ray 2011; Roy 2012). These positionsare now undergoing a dramatic change with the spread ofmarketization created by capitalist relations of production.This helps us to comprehend transitions in a status hierar-chy through the redistribution of symbolic capital or honorand prestige (Bourdieu 1990). It helps us understand newsocial obligations, contests, and solidarities that are createdbecause of marketization and related processes.

Karl Polanyi’s (1944) The Great Transformation is oneof the most influential works on the spread of marketsand has shaped several discussions of the role of marketi-zation in the contemporary world (e.g., Nisbet 1953;Varman and Costa 2008, 2009). Polanyi criticizes the role

Ram Manohar Vikas ([email protected]) is assistant professor of mar-keting at the Institute of Rural Management, Anand, Gujarat, India. Rohit

Varman ([email protected]) is professor of marketing at DeakinUniversity, Melbourne Burwood Campus, 221 Burwood Highway,Burwood, VIC 3125. Russell W. Belk ([email protected]) is Kraft

Foods Canada Chair in Marketing at Schulich School of Business, YorkUniversity, 4700 Keele Street, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M3J 1P3. Direct

correspondence to Rohit Varman. This article is based on the first author’sdissertation. The authors acknowledge the helpful comments of the edi-tors, associate editor, and reviewers. The authors are particularly indebted

to the residents of Chanarmapur for helping them to conduct this ethno-graphic inquiry.

Ann McGill and Darren Dahl served as editors, and Søren Askegaard

served as associate editor for this article.

Advance Access publication July 13, 2015

VC The Author 2015. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of Journal of Consumer Research, Inc.

All rights reserved. For permissions, please e-mail: [email protected] ! Vol. 42 ! 2015

DOI: 10.1093/jcr/ucv038

472Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jcr/article-abstract/42/3/472/1820435/Status-Caste-and-Market-in-a-Changing-Indianby Bibliotheque Cantonale et Universitaire useron 10 October 2017

of self-regulating markets, primacy of economic over so-cial motives, and condemns their 19th-century impositionthrough active state interventions. He interprets the separa-tion of economic and noneconomic aspects of the socialworld as artificial, unsustainable, and destructive. We drawon Polanyi’s call for a substantive analysis and attend tomarketization, subordination, symbolic violence, and al-tered socioeconomic ties.

Our understanding of marketization helps us to offer im-portant insights into status hierarchies not yet studied inconsumer research. Marketization and related processes ofprivatization and individualization are creating new normsof behavior in the village and changing the village hierar-chy and socioeconomic behaviors in several ways. Theseare altering socioeconomic ties that were outcomes of acaste-based moral order and relied on hierarchical normsof gift-giving and sharing. We found reconfigured normsof sharing and relationships within the changing symbolicpower in the setting. This helps to understand moral order,gift-giving, and sharing as ambivalent social structures andprocesses that are steeped in symbolic violence, which getcast in high relief under the influence of a new heterodoxorder that emerged with markets.

Past studies do not sufficiently explain modificationsin Bourdieu’s (1984) concept of habitus and how subordi-nates can countervail the symbolic violence of the elite.As a result, higher status groups are persistently seen tocreate distinctions from lower groups (cf. Ustuner andHolt 2010; Ustuner and Thompson 2012). This readingallows the elite’s symbolic power and their ability to un-leash symbolic violence to remain intact, and it fails tocapture the complete dynamics of economic and socialchange. While we do find that the elite cultivate newtastes based on their habitus in order to distance them-selves in a social space, we find several contradictory fea-tures that call for revising this popular interpretation ofsocial hierarchies. We also found that younger high castemembers adapted to new ways of life in a market econ-omy, and these once-dominant actors are forced to coex-ist in the same social space with lower groups with aconsequent alteration of their symbolic power. Moreover,we find that younger elites come to imitate the popularpractices of lower groups, which results in a reduction, ifnot an inversion, of social distance and the symbolicpower previously associated with these distinctions.These insights help us to develop a more comprehensivereading of marketization and the changing political econ-omy of culture.

MARKETIZATION, SYMBOLIC POWER,AND CASTE

Marketization involves the spread of market forces todomains that were otherwise outside their fold

(McAlexander et al. 2014). It often results in privatizationand a rise in individualism. Consumer researchers haveidentified several areas such as education (Varman, Saha,and Skalen 2011), medicine (Thompson 2004), and reli-gion (McAlexander et al. 2014; Srivastava 2011), to namea few, that have been deeply penetrated by markets in re-cent years. These studies have broadly examined the ques-tions of identity construction, consequences ofmarketization, and resistance to or devalorization of non–market-based processes. Many of these researchers haveadopted a critical perspective in which markets are viewedas harmful institutions that should be restricted to ensureconsumer welfare (Cronin, McCarthy, and Collins 2012;Klein 1999; Varman and Vikas 2007). Others have chal-lenged this interpretation of markets as harmful institutionsand have argued in support of market-based exchanges(Arnould 2007; Marcoux 2009). Despite such insights, theimpact of marketization on social hierarchies and new sta-tus contests created in its wake has not been understood.

In his seminal work on the rise of markets, Polanyi(1944) critically examines the question of marketizationwith the spread of capitalism. In a scathing criticism ofmarket economy, resulting privatization, and attempts to es-tablish self-regulating markets through commodification ofland, labor, and money, he argues that the project is unnatu-ral and unsustainable. At the outset, Polanyi (1944) differ-entiates between “market society” and “market in society.”Market in society, as it prevailed in different parts of theworld until the 19th century, implies that markets reflectthe prevailing social order and are embedded in it, whereasmarket society implies that the unnatural laws of marketsimposed from outside through state interventions becomefundamental and govern the social order (Polanyi 1968a).

Polanyi (1944) saw only a limited role of markets beforethe 19th century. Accordingly, long-distance trade or exter-nal markets were kept separate from local markets thatonly had a restricted presence in societies dominated byhousehold economics. Polanyi (1968b) further carefullyseparates gift trade and administered trade from the morerecent idea of market trade based on the logic of supplyand demand. Polanyi (1968b, 170) particularly interpretedhiggling-haggling or “exchange at bargained rates” asharmful for social solidarities. He further observed that im-position of self-regulating markets created a spontaneousdouble, or counter, movement to restrict their spreadthrough state and social interventions (Polanyi 1944).Moreover, he challenges the “formalist” or rational anduniversal notions of market society and contends that asubstantivist view that attends to specific contexts and em-bedded economic motives must be developed.

Polanyi’s biggest contribution to our understanding ofmarkets is his emphasis on how economic and socialmotivations become intertwined and produce particularoutcomes. Drawing on this idea, Parry (1989) offers abrilliant analysis of how Gregory’s (1982) moral

VIKAS ET AL. 473

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jcr/article-abstract/42/3/472/1820435/Status-Caste-and-Market-in-a-Changing-Indianby Bibliotheque Cantonale et Universitaire useron 10 October 2017

distinction between gifts and commodities on the basis ofnoncommercial/commercial separation is limiting. Parry(1989, 66) observes “the poison of the gift” and prevalenceof the belief that alms given to the big Benaras pilgrimagepriests cannot be used for productive economic invest-ments and gets wasted by them in nonproductive activities.On the contrary, Parry (1989, 81) shows that acquisition ofcommercial wealth, despite its moral dilemmas, is a legiti-mate and laudable objective in the setting as long as it canbe “justified by the generosity with which it can then bedisbursed.” Thus, as Polanyi has suggested, Parry’s (1989)substantive analysis shows the intertwined nature of eco-nomic and social, and how these conflicting motives cometogether to produce social and moral outcomes.

These contributions do not imply that Polanyi’s work hasnot been questioned for certain limitations. Some scholarscriticize Polanyi (1944) for failing to understand the preco-lonial spread of markets, money, and of profit motive innon-European societies (Braudel 1979). Moreover, his pas-sion for nonmarket ways led him to, as Gerlach (1997, 43)observes, a “Rousseauistic vision of harmonious, integratedprimitive societies.” He has also been criticized for his fail-ure to understand how contemporary gain-centric marketswere never disembedded from social relations (Braudel1979; Heejibu and McCloskey 1999; McCloskey 1997). Itcan be argued in his defense that Polanyi’s (1944) passion-ate rejection of the primacy of markets stemmed from hisdeep concerns about the displacements caused by capital-ism to the 19th-century social world.

A similar rejection of markets and yearning for commu-nity or social ties is central to several classical writings insociology (see Nisbet 1966). This can partly be traced toTonnies (1887, 18), who in a classic critique of capitalismintroduced the concepts of gemeinschaft, or community,and gesellschaft, or society. According to Tonnies (1887,95), gemeinschaft founded on wesenwille or natural will,fosters development of human beings in harmony withtheir habitats, with close identification with other humanbeings. On the other hand, Tonnies (1887, 95) argues, ges-selschaft is based on kurwille, or rational will, that es-tranges one human being from the other, with the externalworld as an object to be acted upon and controlled. Thiscelebration of community by Tonnies, Polanyi, and othersbecame particularly influential in shaping conservativewritings in which social ties become a bulwark against thetyranny of the state or markets (e.g., Nisbet 1953).

Instead of setting up a market versus community di-chotomy, we wish to examine how economic and noneco-nomic motives interact under marketization to producesocial outcomes. More specifically, we examine a caste-based social order working on the principle of centricitythat exploits the majority of its population with gains ac-cruing to a few occupying the center. This helps to attendto symbolic power and changes in entrenched socialhierarchies.

Symbolic Power

In developing a critical understanding of the intertwinednature of economic and noneconomic motives, Bourdieu(1979) is particularly helpful. Bourdieu (1979, 2005) inter-prets the social as a field constituted by relations of force.He observes that the force attached to an actor in a field de-pends on his or her volume and structure of economic, cul-tural, social, and symbolic capital.

Recent writings in consumer research offer a sophisti-cated understanding of status and symbolic power, largelybased on Bourdieu’s (1990) concept of symbolic capital.For Bourdieu the power stemming from symbolic capital isbased on its ability to legitimize existing economic and po-litical relations, and to create unequal social relations. Inconsumer research, Holt (1998) used Bourdieu’s frame-work in his analysis of American consumption and offeredinsights into different dimensions of taste among low andhigh cultural capital groups. Similarly, Allen (2002) in ex-amining the idea of consumers’ choices emphasized theroles of social class–based habitus and ongoing practices.And several consumer researchers have focused their atten-tion on in-group social hierarchies (e.g., Arsel and Bean2013; Arsel and Thompson 2011; Kates 2002; Schoutenand McAlexander 1995). In the last few years, several au-thors have closely examined status and stratification in lessindustrialized countries (LICs). For example, Ustuner andHolt (2007) found that among poor women in a Turkishsquatter community, three patterns existed with regard tothe dominant consumption ideology: shutting out the domi-nant ideology, pursuing this dominant consumption pat-tern, or giving up on both practices and suffering ashattered identity project. In offering a theory of statusconsumption in LICs, Ustuner and Holt (2010) show thatlow cultural capital consumers are situated within an indig-enized field and are influenced by local elites in consump-tion choices that determine status in Turkey. For their part,high cultural capital consumers copy Western consumersand their mythical lifestyles to assert their superiority oversubordinate groups. In the same cultural context, Ustunerand Thompson (2012) observe that market encounters instratified settings are marked by status struggles and bycontested forms of symbolic capital. They further reportacceptance of the symbolic power of the elite as reinforcedby attempts of subordinate groups to reconfigure their hab-itus to match the dominant groups.

The idea of power is central to Bourdieu’s analysis, andhe reads it as domination by an actor in a field. Dominationis an outcome of combinations of the various forms of cap-ital that people possess that help them to gain an exaltedposition within a field. Thus, in a situation of marketiza-tion, when market relations transform an existing socioeco-nomic field, the ability of the person to draw on theavailable capital and to generate new capital from externalsources is an important element in the process of

474 JOURNAL OF CONSUMER RESEARCH

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jcr/article-abstract/42/3/472/1820435/Status-Caste-and-Market-in-a-Changing-Indianby Bibliotheque Cantonale et Universitaire useron 10 October 2017

transformation. This makes marketization a process of so-cial change that creates conflicts between old and new in-terests or alignments as it transforms relations of force in afield. In Bourdieu’s reading this conflict often manifests it-self in a contest between actors holding on to the older hab-itus that valorizes tradition and others who are willing toadapt and adopt the entrepreneurial logic of markets(Swedberg 2010). Bourdieu (2005, 86) interprets habitus associalized subjectivity or a screen through which actors in-terpret and create “intentional action without intention.”Accordingly, those in a field with a particular habitus thatresulted from traditional socialization have to deal withnewer social forces that challenge it. This results in a detra-ditionalization of earlier social institutions (McAlexanderet al. 2014) and can create gaps between habitus and thestructure of the economy (Bourdieu 1979). Accordingly,markets require a different social rhythm that those withtraditional habitus have to adapt to because it leads to a re-dundancy of older ways of life and authority. In this analy-sis, Bourdieu (1979) is close to Polanyi’s (1944) reading ofthe rise of markets that results in the older ways of life inwhich social and economic concerns were deeply inter-twined to be forcefully separated.

Bourdieu’s (1984, 1990) key theoretical concern was tounderstand how arbitrary choices and relations in a socialspace, or a field, get transformed into legitimate relationsthat help to create widely recognized distinctions and statushierarchies. In particular, Bourdieu offers insights into dis-guised forms of domination in a field. In this conception,the ideas of symbolic capital and symbolic power are ofgreat importance. Bourdieu (1990, 118) interprets symboliccapital as “capital of honor and prestige which produces aclientele as much as it is produced by it.” He believes thatexercise of power often requires its legitimation, and thatcomes with prestige or status. Bourdieu does not interpretsymbolic capital and power as post hoc outcomes. Instead,he locates symbolic power in habitus and fields of practiceswhen he points to the “double historicity” of dispositions(Bourdieu and Wacquant 1992, 139). Accordingly, ideas ofsymbolic capital emerge out of habitus that is a product ofinitial socialization into social structures, which, in turn,are results of the historical work of succeeding generations.

Bourdieu delves into political functions of dominantsymbolic systems and questions their taken for grantedcharacter as worldviews of a society. Accordingly, statushierarchies are based on social domination but often gomisrecognized as a form of power under the veneer of astatus culture that legitimizes domination by presenting itunder the guise of disinterestedness. Such a system ofpower fulfills a political function by creating symbolic vio-lence in which the subordinates accept as legitimate theirown condition of domination (Bourdieu 1977).

In his analysis of symbolic power, Bourdieu (1990,281-82) attaches great significance to the role of the thresh-old in a society, and he illustrates that thresholds are where

social battles take place. Accordingly, practices at a thresh-old can be a threat to an established order and entrenchedgroups make efforts to ward off these dangers. This makesit necessary to pay close attention to such places and to thediscourses and practices that take place within them.Bourdieu (1990, 228) further suggests that consumption insuch places should be closely attended to because “con-sumption visibly mimes this paradoxical inversion.”

In existing consumer research, private and public placeshave been defined according to ownership of the place.However, many of the ordinary places in our daily lives donot fall neatly into the categories of private or public placesand are ambivalently situated. We interpret the thresholdplace as a hybrid and ambiguous place. Here the hybridityand ambiguity of the place stem from contradictions be-tween ownership, consumption, and in-betweenness.

Our understanding of thresholds to a considerable extentis based on the conceptualization of Bourdieu (1977, 130),who describes it as “a sort of sacred boundary between twospaces, where the antagonistic principles confront each an-other and the world is reversed.” Accordingly, the thresholdcan take spatial, temporal, or seasonal forms. For example,the physical space at the entrance of a house is a thresholdplace between inside and outside, male and female, and pri-vate and public places. Similarly, the season of spring is athreshold because it “is an interminable transition, con-stantly suspended and threatened, between the wet and thedry, ... or, better, a struggle between two principles with un-ceasing reversals and changes in fortunes” (Bourdieu 1977,131). In Bourdieu’s understanding, ambiguity is an essentialfeature of a threshold and is also marked by the order ofthings being turned upside down. Thus Bourdieu has con-ceptualized the threshold physically and temporally as beingpregnant with internal tension. Bourdieu’s (1977) notion ofthe threshold is similar to the liminal of van Gennep (1960)and Turner (1974). However, Bourdieu’s (1977) threshold ismore commonplace and is not located in some special, spec-tacular, or magical space. It is located in the daily or ordi-nary space of a common person.

Bourdieu contends that meanings of movements acrossthresholds are often contested. For example, women andmen give opposite importance to the meaning attached tomovements across threshold in Kabyle society (Bourdieu1990). A man is ordinarily expected to be seen outside andthe socially acceptable movement is his coming out of ahouse, whereas for a woman, who is expected to be inside,her outward movement is extraordinary and related to actsof expulsion. Moreover, he suggests that the meaning of athreshold is intersubjectively determined. This aspect, inparticular, draws our attention to the role of our partici-pants in not only inheriting aspects of the threshold thathave been naturalized to them as objective facts throughsymbolic violence, but also to their subjective actions inthe domain of consumption that create new thresholds ortransform the old ones.

VIKAS ET AL. 475

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jcr/article-abstract/42/3/472/1820435/Status-Caste-and-Market-in-a-Changing-Indianby Bibliotheque Cantonale et Universitaire useron 10 October 2017

In sum, a Bourdieusian perspective helps to understandsocial orders as contested fields that are constituted bypower plays, domination, and distinctions. Despite offeringa rich social analysis of forces that constitute a field, thisperspective does not delve into how contests between thedominant and dominated unfold under conditions of mar-ketization. More specifically, how symbolic powers of dif-ferent groups undergo transitions due to marketization isunderexamined. In this ethnography, the focus of our studyis on exchanges and consumption in threshold places andtheir influence on transitions in symbolic power and statuspositions of different caste groups. We next turn to the is-sue of caste.

The Caste System in India

Caste, which means pure or chaste, is one of the mostenduring features of Indian society, and Dirks (2002, 3) ob-serves that it “defines the core of Indian tradition.” Thissystem of stratification originated thousands of years agoand continues to imprint social and economic relations inthe country despite its official prohibition as a basis for dis-crimination (Teltumbde 2010).

The central idea of the caste system is a hierarchy thatworks against the two cardinal principles of equality andliberty (Dumont 1970). The caste system discriminates be-tween groups of people on the basis of the ritualistic normsof purity and pollution, high versus low status, and rules ofcommensality (Dumont 1970). While Dumont’s focus onthe caste order as a unified system had shortcomings (cf.Fuller 1989), an enormous amount of literature available inthe social sciences on caste shows that it propagates in-equality or social stratification through symbolic power.According to Dumont (1970), Brahmins (priests) are con-sidered at the top, followed by Kshatriyas (soldiers) andVaishyas (traders), who are all considered Dwija, or twiceborn. These upper castes are followed by Shudras, or lowcastes, and at the bottom of the hierarchy are Dalits, or out-castes, who were untouchables. Many Dalits do not con-sider themselves to be Hindus and have actively resistedattempts to incorporate them into the Hindu caste hierarchy(Ilaiah 1996).

Social stratification of caste can be explained throughthe vertical axis of hierarchy and horizontal axis of differ-ence, repulsion, and segmentation (Bougle 1991). Caste isa system of distinctions that allows intergenerational trans-fer of symbolic power and corresponding economic, cul-tural, and social capital. Beteille (1991, 1996) drawsattention to these differences in terms of fairness of skin,house, dresses, food, education, and rituals to emphasizethe various forms of capital possessed by the higher castes.Therefore, the symbolic power of the caste system in Indiahas been its ability not only to classify or stratify, but toachieve this in practice by making itself natural and takenfor granted or through symbolic violence.

Jajmani was an important characteristic of the caste sys-tem that underpinned the working of the socioeconomicsystem in many parts of North India (Wiser 1988). Theterm Jajman, or patron, was initially used in a limited sensefor the relationship between a Brahmin and his clients andincluded fees that Brahmins charged for the performance ofany solemn or religious ceremony (Dumont 1970; Mayer1993). Unlike Dumont (1970), Fuller (1989) does not seecaste as antithetical to modern property rights, and inter-prets Jajmani as an amorphous order that defined divisionof labor in varied forms across the country. Because agri-culture was the most important economic activity in thepast, the landowning upper castes were at the epicenter ofthe Jajmani order. In this system, low caste workers wereexpected to serve their high caste patrons according to thecaste-based division of labor. The rights and remunerationof workers were defined according to unwritten norms thatwere primarily determined by the upper caste. The Jajmaniorder functioned as a moral economy in which “the mecha-nism of exchange has so little detached itself from norma-tive contexts that a clear separation between economic andnoneconomic values is hardly possible” (Habermas 1987,163; see also Sayer 2004; Scott 1976; Weinberger andWallendorf 2012). Although many scholars have inter-preted earlier moral economies as humane orders and havecriticized markets for their commodifying and dehumaniz-ing influences (e.g., Booth 1994; Etzioni 1988; Polanyi1944), the normative framework that impelled the Jajmanisystem is considered oppressive and exploitative by thelower castes (Dirks 2002; Omvedt1995).

The system’s fixity does not mean that the symbolicpower encoded in the caste system did not witness strug-gles, contests, and changes (Fuller 1989). The caste systemhad its own dynamics in which groups could change theirpositions over a period of time, and the occupational cate-gorization was not completely ossified. Gupta (1991) hasfurther argued that there were several vertical hierarchiesin the caste system and some of the lower and outcastesalso proclaimed exalted origins (see also Beteille 1991).

Srinivas (1991) further adds that the country witnessedseveral caste-based movements, including a strong anti-caste struggle under the leadership of Bhimrao Ambedkar,to challenge the authority of the upper castes (see alsoJaffrelot 2003; Omvedt 1995). This struggle has meant thatsome of the earlier status positions cannot be taken forgranted, and lower castes are more assertive and free to re-sist the upper castes in many parts of the country.Furthermore, over a period of time some old castes havedisappeared, merged with each other, and new ones havebeen formed (Teltumbde 2010).

Miller (1986) suggests a more congenial view of theJajmani system in which the social embeddedness of ex-change relations between castes was seen as nonalienating.Furthermore, he contends that rather than opposing andthreatening the Jajmani system, the market economy both

476 JOURNAL OF CONSUMER RESEARCH

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jcr/article-abstract/42/3/472/1820435/Status-Caste-and-Market-in-a-Changing-Indianby Bibliotheque Cantonale et Universitaire useron 10 October 2017

within and outside the village allows the balance of excessand insufficient production of secular exchange goods thathelp to reinforce the Jajmani system. Thus, to Miller, themarket poses no threat to the traditional Jajmani systemand even supports it. However, two points are worth not-ing. First, Miller was concerned with the external exchangeor sale of goods (pottery) rather than labor. Second, hisfieldwork was carried out in the early 1980s before theIndian market liberalizations of the early 1990s.Nevertheless he has subsequently made the same argu-ments, suggesting that Jajmani is “an ideal form of ex-change, which expresses the moral and ideologicalaspirations of the participants” (Miller 2002, 241). As willbe shown, not only does the contemporary labor and ser-vice market economy of India change things, the Jajmanisystem involved exploitative power dynamics.

In summary, caste-based stratification in India has ex-isted for more than a thousand years. The Jajmani orderunderpinned the accumulation of symbolic capital withinthe caste system and created symbolic power that was in-tergenerationally stable and acted as a bond on the lowercastes. The moral economy created by the Jajmani systemis under increasing threat with the deepening of capitalismacross the country and with increasing politicization of thelowers castes. In more recent times, high castes’ symbolicpower or legitimacy has come under increasing attack fromthe lower castes. As would be expected, people who areforced to forgo their privileged status try their best to retaintheir positions by hindering free exchanges and by monop-olizing market goods. While caste struggles are extensivelydocumented in social theory in India, the role of marketiza-tion and its impact on the symbolic power of differentgroups within this theorization are still minimally studied.In the context of this struggle between the dominant andthe subordinate, it is this new political economy of culturethat we particularly attend to in our ethnography in order tounderstand the changes in exchanges, consumption, status,and symbolic power in Chanarmapur.

ETHNOGRAPHY IN A NORTH INDIANVILLAGE

This research is a study in the village of Chanarmapur(pseudonym) in North India. We conducted an ethno-graphic case study (Atkinson and Hammersley 1983;Spradley 1979). The first author conducted the fieldwork.For the sake of simplicity we have used “we” in this andthe other sections of the article.

Chanarmapur is located in the North Indian or Indo-Gangetic plain in the state of Bihar. Bihar is one of thepoorest states of India with the lowest per capita income inthe country at Rs 7875 ($131) in 2005–06 (PlanningCommission 2008). The village is situated 2.5 kilometersto the west of Robertsganj (pseudonym). Robertsganj was

central to revenue generation in the region during theBritish rule in India (Bayly 1988; Yang 1998), and it con-tinues to be an important market city in the region.

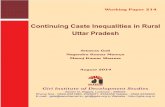

The village contains seven hamlets. People from thesame caste or friendly castes live together in each hamlet.Several caste groups reside in the village. The total popula-tion of Chanarmapur is 3028; there are 406 houses in thevillage. The villagers speak Bhojpuri, and the village iswell connected with an asphalt road. It has a school and abank. Literacy in Chanarmapur is 67% among men and48% among women. There is an increasing emphasis onsending children to school, and of the 219 students, 53%go to the state school and the rest go to private schools out-side the village (refer to the village layout in figure 1).

Until recently, land ownership in the village was an im-portant factor that decided the economic status of a house-hold. Since agriculture is one of the main occupations anddependence on land is high, 79% of the landowners ownless than one acre of land. The size of land holdings ishighest among the high caste Bhumihaars (averagingnearly 2.5 acres). About 23% of households are landless.The agricultural fields are divided into two types based onthe location: chaur and goeda. The former are fields thatare far away from the settlement and relatively low lying.Paddy, wheat, and other crops that are produced in densequantities per acre are farmed in chaur. Goeda fields arenear the settlements and used for crops such as vegetablesthat need day-to-day cultivation. In recent years, economicconditions have made agriculture unsustainable in this partof the country. Landowners prefer to rent their land and en-gage in alternative sources of income generation in the vil-lage or in cities (see Varman, Skalen, and Belk 2012).

In Chanarmapur the Hindus can be divided into threecategories of Bar Jaat (high caste), Chot Jaat (low caste),and Achut (untouchables). Achuts also include Dhuniya,who are Muslims. Rajputs are the largest caste group. Thethree high castes of Bhumihaar, Brahmin, and Rajput to-gether comprise 42% of the population of the village. Inthe remaining 58% are 14 lower castes. Muslims constitute5% of the village. The Scheduled Caste is the lowest in thecaste hierarchy, consisting of Chamar, Dusaadh, andDhobi, and constitutes 12.5% of the village population.Caste is not a matter of researcher interpretation but an ob-jective position that is preassigned based on heredity.However, within the broad categorization of castes, such aslow or high, there can be specific local interpretations. Forexample, in this region, Bhumihaars are considered higherthan Brahmins, who in turn are higher than Rajputs. This isnot a matter of external or self-designation but a locally de-termined objective position.

Methods

Chanarmapur is also the ancestral village of the first au-thor. We maintained a separation between our research

VIKAS ET AL. 477

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jcr/article-abstract/42/3/472/1820435/Status-Caste-and-Market-in-a-Changing-Indianby Bibliotheque Cantonale et Universitaire useron 10 October 2017

interests and personal ties by keeping away from any en-gagement with personal issues of the villagers and refrain-ing from interfering in village politics. In order to gainaccess, we participated in the village festivals. The first au-thor also taught schoolchildren of the villagers withoutcharging a fee. Since most of the villagers aspire to educatetheir children, they perceived his effort as a welcome offer-ing to the entire village. This helped us to gain access at adeeper level.

The first author is a Bhumihaar and belongs to an absen-tee landlord family. There was suspicion because his ances-tral house was locked for more than a decade and nobodyfrom the extended family came to live in the village afterthe death of the first author’s father’s uncle, who was thehead of the joint family. When the first author started the

fieldwork, no one except members of his own kin recog-nized him as a village resident. He introduced himself as agrandson of his father’s uncle. His local cook was his ethno-graphic guide and also introduced him to the villagers.

A naturalistic inquiry cannot be fully designed beforeentering the field. The emphasis is on a dynamic researchdesign that is a reflexive process (Atkinson andHammersley 1983). Following this design, we started with-out any assumptions, and the first step was to observe andrecord market and consumption phenomena in detail striv-ing for thick description (Geertz 1993). We followed an it-erative process and continued with our fieldwork until weachieved interpretive sufficiency and reached a point of re-dundancy, making further data collection unnecessary(Belk, Sherry, and Wallendorf 1988).

FIGURE 1

LAYOUT OF CHANARMAPUR VILLAGE

478 JOURNAL OF CONSUMER RESEARCH

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jcr/article-abstract/42/3/472/1820435/Status-Caste-and-Market-in-a-Changing-Indianby Bibliotheque Cantonale et Universitaire useron 10 October 2017

During the initial phase of the research we used purpo-sive sampling and selected participants on the basis of theircaste. Various castes of the village represent distinct socialgroups, and hence we chose participants from all thecastes. Later we realized that there were issues of articula-tion and access. We subsequently adopted a theoreticalsampling technique to focus on stratified consumptionpractices and the question of status. To address variation,we selected our participants on the basis of caste, age, gen-der, and economic status. We conducted 35 interviewswith the villagers and included every caste group in oursample. A concise description of participants is shown inTable 2.

We used multiple sources of data generated through par-ticipant observation (Atkinson and Hammersley 1983;Patton 2002), interviews (McCracken 1996), and photogra-phy (Belk et al. 1988). Some of the topics that we pursuedwere names and meanings of the important sites inChanarmapur, ownership, exchanges, and consumptionpractices connected with these sites, and perceived changesin exchanges and consumption in the past decade. We alsoasked our participants to narrate local lore about the impor-tant sites and consumption practices. We asked them tonarrate their interpretations of Jajmani relationships andhow they have changed in the last few years. We alsoasked them to share their meanings of these changes. Weobserved consumption in different places and also partici-pated in conversations with the villagers who congregatedat religious sites. This helped participants to explain con-sumption rituals during marriages, betrothals, and festivalssuch as Holi and Chath. We visited different places, suchas sports grounds, religious places, the burial ground, theschool, and the small shops of Chanarmapur. We walkedand cycled through the village and neighboring villages toobserve whether similar changes were happening in the vi-cinity. More specifically, we examined consumption in thethreshold places of Duar, Chath Ghat, and Bagaicha. ADuar is the place in front of a house, the Chath Ghat is thebank of the local pond, and the Bagaicha is an orchard (fordescriptions of these places, refer to appendix A; hereafterwe use house-front, pond-bank, and orchard for Duar,Chath Ghat, and Bagaicha, respectively). These are thekey areas within the village.

Analysis of the data was done throughout the fieldwork(Glaser and Strauss 1967) to aid interpretive tracking andcomparative analysis through a grounded reading of thedata (Strauss and Corbin 1998). We conducted a herme-neutical analysis by comparing interviews or observationsin light of emerging theoretical concepts and underlyingthemes (Thompson and Troester 2002). We facilitated theiterative process of interpretation and comparison by usingmemos. Post field interpretation was done through formalcoding. We used open, axial, and selective codingapproaches. The open codes helped in the identifying con-cepts, whereas axial coding helped in the identification of

different subcategories, and selective coding helped in inte-gration with existing theories. Rigor in the research wasmaintained through different processes of pursuing trust-worthiness (Lincoln and Guba 1985), such as triangulation,prolonged engagement, persistent observation, peer de-briefing, and member checks. We were in the field for oneyear. Regular interactions with our participants and obser-vations during our visits to the neighboring villages helpedus to understand transitions in the status hierarchy inChanarmapur. We shared our observations with our col-leagues for peer debriefing. We conducted member checksby sharing our interpretations with the participants and byinquiring about their adequacy.

MARKETIZATION, STATUS, ANDTRANSITIONING POLITICAL ECONOMY

In this section, we provide a description of how marketi-zation has come to alter the status of upper casteBhumihaars and Brahmins in the village. We use the termlow caste to include all the castes that are belowBhumihaars and Brahmins, who were traditionally at the topof the caste hierarchy in this region. This is a context of pov-erty, and all consumption levels in this village are still lowby Western standards. We delve into marketization and thelower castes’ consumption of food, furniture, housing, reli-gious objects, services, and other consumption aspects ofeveryday life. We confine much of our analysis to changesin consumption in threshold places of house-front, pond-bank, and orchard as a consequence of marketization andaccompanying privatization, and their ramifications for thedistribution of symbolic power in the village.

Marketization, Freedom, and New Dependencies

The Jajmani system was a guarantor of privileges forBhumihaars and Brahmins. This moral order involved lowcaste dependency on the high caste Bhumihaars throughpatron–client relationships. These ties created moral obli-gations for the lower castes, and domination was “dis-guised under the veil of enchanted relations” perpetuatinga form of “symbolic violence” (Bourdieu 1990, 126). Untila few decades ago, landlords and high castes controlled theeconomic and social lives of lower castes. Lower casteswere dependent on landlords and were not allowed to workfor others or to start their own entrepreneurial ventures.They had to get approvals from landlords before enteringinto economic transactions with others. The Jajmani sys-tem was so dominant that low castes had to either run awayfrom the village or lose their lives if they violated this prin-ciple. Even the low caste artisans had to sell their producethrough patron landlords, who acted as middlemen be-tween producers and traders. Trading of goods was alsoscripted on the basis of caste affiliations as early markettransactions were defined by Jajmani ties (e.g., Telis dealt

VIKAS ET AL. 479

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jcr/article-abstract/42/3/472/1820435/Status-Caste-and-Market-in-a-Changing-Indianby Bibliotheque Cantonale et Universitaire useron 10 October 2017

TABLE 1

CASTE AND CHANGING OCCUPATION STRUCTURE IN THE VILLAGE

Caste category Castes Traditional occupation Present occupation

High Bhumihaar Zamindar, or landlord, agriculture Absentee landlords; migrated to cities where they work as doctors,engineers, professors, clerks, government workers

High Rajput Army men of Zamindar, agriculture Agriculture, politics, government jobsHigh Brahmin Priest of Bhumihaars and low castes Agriculture, work as security guards in cities; priestsLow Teli Oil seed collection and pressing Agriculture on rent, retail shops in a nearby town, agents of insurance

and financial productsLow Nonia Agriculture workers of Bhumihaars Agrarian workers, migrated to city as construction workersLow Dhanuk Village merchants Agriculture on rent and also workers in the local brick kilnLow Kanu Purchased and processed jute and flax Agriculture on rent and also work as workers in the local brick kilnLow Yadav Milk products Milk products, AgricultureLow Gond Parching of grains for clients Parching of grains, agriculture on rent, government servicesLow Koeri Vegetable farming Agriculture on rent, retail shops, rice mills, interior decoration businessLow Hazam Hair cutting of clients Hair cutting by opening salon in a nearby town and other citiesLow Lohar Iron work related to agriculture Iron workshop in local town to fabricate windows, doors, gates,

construction contractor. Workers in bus body building shopUntouchable Dusadh Godait, or army men, of Bhumihaars Agriculture on rent, agricultural work, and construction workerUntouchable Chamar Plowmen of Bhumihaars Agriculture on rent, construction work, motor drivingUntouchable Dhobi Clothes cleaning for clients Clothes cleaning shop in the marketUntouchable Dhuniya Cotton carding, agriculture worker Agriculture worker, construction worker, construction contractor,

electrician

TABLE 2

LIST OF PARTICIPANTS

Pseudonym GenderAge,years Caste Profession

Interview duration,in hours

Bharan Ram Male 73 Chamar Agricultural worker 7Bharat Singh Male 62 Bhumihaar Living on pension, Landlord 8Chunnu Male 40 Brahmin Entrepreneur 10Pukar Sah Male 70 Gond Agricultural worker 6Hanuman Singh Male 44 Rajput Farmer 6Irfan Mia Male 75 Dhuniya Living on pension 8Jagan Ram Male 75 Chamar Agricultural worker 8Janak Tewari Male 55 Brahmin Priest 10Janam Sharma Male 65 Lohar Contractor 10Jitender Ram Male 30 Chamar Agricultural worker 8Jyoti Female 50 Bhumihaar Housewife, teacher 8Lakhan Bo Female 45 Nonia Agricultural worker 7Mahato Male 54 Nonia Agricultural worker 10Matin Male 20 Dhuniya Worker 10Narender Singh Male 20 Rajput Student 8Pravind Male 34 Bhumihaar MBA, entrepreneur 8Radha Singh Male 80 Bhumihaar Living on pension, landlord 10Rajinder Ram Male 70 Chamar Living on pension 8Raju Male 28 Chamar Private tutor 6Ramavtar Male 60 Chamar Agriculture 10Ram Singh Male 75 Bhumihaar Landlord, politician 8Ramji Male 70 Nonia Agricultural worker 10Ramesh Singh Male 58 Rajput Agriculture and politics 5Salim Male 48 Dhuniya Contractor 8Samran Male 66 Chamar Agricultural worker 6Sanjay Singh Male 38 Bhumihaar Landlord 8Satendra Singh Male 54 Bhumihaar Physician 10Satish Yadav Male 28 Yadav Politics 10Sita Singh Female 45 Rajput Housewife 8Sohan Lal Male 36 Teli Professional 10Suganti Female 60 Nonia Agricultural worker 4Sujodhan Male 45 Brahmin Worker 5Sunita Female 40 Nonia Agricultural worker 6Susant Pande Male 20 Brahmin Student 8Zainab Female 23 Dhuniya Agricultural worker 4

480 JOURNAL OF CONSUMER RESEARCH

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jcr/article-abstract/42/3/472/1820435/Status-Caste-and-Market-in-a-Changing-Indianby Bibliotheque Cantonale et Universitaire useron 10 October 2017

in oil, Dhanuk in jute, Awadhiya in sugarcane, and Kanu incereals). In the Jajmani system, landlords also collectedtaxes from these transactions. These taxes were collectedboth on the purchase of raw materials and at the time ofmarket sale. In the absence of a sufficient number of mar-ketplaces and limited economic opportunities, the lowcaste found it extremely difficult to escape the clutches oflandlords.

In the moral economy low castes were dependent ontheir patrons to fulfill even their smallest desires to con-sume. Samran, an elderly untouchable lamented, “In thezamindari era in evenings before proceeding to the marketwe used to go to the landlord. He would ask why we werethere. We would say ‘O Landlord! Please give us one anna(Rs 0.06 or $0.001) to buy tobacco.’ The landlord was ourpatron, and he would give us money in the evening to buytobacco.” Tobacco is a very commonly consumed productamong the men in the village. It is also considered trivialand commonly shared if a fellow villager demands it.Several participants told of their anguish about this period,“We did not have money even to buy one pinch of tobacco.We had to depend on our landlord to buy tobacco for us.”

In the last few decades, with the expansion of the Indianeconomy and deepening of capitalism, many markets havedeveloped in and around the village that have reduced thedependence of the villagers on landlords. These marketsoffer opportunities to the low caste to have their own smallshops or offer their services. With the expansion of eco-nomic activities in the area, there are several businessesthat require workers, and low caste villagers have foundopportunities there. Migration to large cities and in the eastto the tea gardens of Assam and West Bengal has alsobrought in much needed money for the low castes. In the1970s, many Muslims from the region went to the MiddleEast. Their remittances suddenly catapulted them fromlowly untouchables to those with high respect in a marke-tized social order in which economic capital was beginningto be one of the key assets to possess. Pahariya, a townnear the village, became a big market of consumer prod-ucts because of the newfound wealth of the lower castes. Amanager of a large national bank informed us that his localbranch has the highest turnover in the entire state. In thenearby district, the General Post Office had the distinctionof receiving the maximum amount of remittances in amonth in the entire country.

This process of marketization came about because of in-ternal tensions in the village and also due to extraneous fac-tors. The agrarian economy was already in decline andoffered unsustainable returns (see Varman et al. 2012). Thiscreated greater pressure on both the high and low castes toshift to other occupations. When the young low castes goteconomic opportunities outside the village, they startedbreaking the bonds of subservience. The market economyalso offered riches to several high castes as they started mi-grating to urban centers. The low caste migrants were able

to save money from their market-based activities and subse-quently able to buy land. This has led to some change inland ownership and has offered freedom to the low castesbecause they do not have to fear their patrons any longer.

Access to education also helped the lower castes tomake use of market opportunities. Education is consideredimportant by the lower castes, and when we offered toteach children in the village, most low castes were happyto send their children to us. They realize that the lowercastes who have done well with the onset of marketizationare also the ones who could widen the scope of their world-views and make use of the opportunities that markets pre-sent to them (see also Bourdieu 1979).

For example, Rajinder, a Dalit who migrated to Kolkata,after getting a basic education from the village school, gotan opportunity to work as a clerk in a jute mill. His chil-dren are educated and work for the government. MostDalits look up to them, and they are the new village rolemodels. In the past this process of getting a basic educationwas not easy, and Jitender, a poor Dalit, complained aboutthe prior domination of the landlords: “Those were difficulttimes. My grandfather told me that he could not study be-cause his landlord did not allow him to study. One day thelandlord went to the school and he dragged my grandfatherout of the class and beat him. The landlord abused him andsaid that if he goes to school who will plough the field.”

This became a vicious cycle in which those not allowedto get schooling got further trapped in their Jajmani ties,and there was no escape from the domination of landlords.Although there are some, largely dysfunctional, govern-ment schools, private schools that charge tuition now dom-inate in the region. But access to such private schools isstill difficult for the poor. Those families that have man-aged to become educated, such as Rajinder’s, access theopportunities presented by markets. However, those whoare not educated slip deeper into the abyss of poverty.

Another factor that has contributed to the greater indepen-dence of the lower castes is a shift in the political field. Thepolitics of the village have changed in the last 20 years.While the high caste Bhumihaars and Brahmins were com-petitors in the first few decades after India’s independence,in the last two decades several low caste political partieshave captured state power and challenged the dominance ofthese high castes. Rajputs, who were at the bottom of thehigh caste hierarchy, have become politically powerful inthe region. Ram Singh, an elderly Bhumihaar, told us,

I will tell you that today no other caste is ready to support aBhumihaar candidate. You might be aware what happenedto the Bhumihaar candidate of JD-U [Janata Dal United, theruling party in the state that had nominated a Bhumihaarcandidate, who lost in the last general elections] in the MP[Member of Parliament] by-election. A Rajput won. Thepolitics has become very bad. Bhumihaars have no rolenow. We do not have the numbers.

VIKAS ET AL. 481

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jcr/article-abstract/42/3/472/1820435/Status-Caste-and-Market-in-a-Changing-Indianby Bibliotheque Cantonale et Universitaire useron 10 October 2017

In the absence of any formidable challenge fromBhumihaars and Brahmins, Rajputs are the new dominantcaste of Chanarmapur. Some Rajputs are politically pow-erful and economically rich. Although Rajputs are power-ful, the caste relationships have changed, and there is fargreater independence for the lower castes as compared tothe past. There are several poor Rajputs in the village whoare in subordinate positions to the richer low castes. Ahigh caste Rajput won the last parliamentary election, buthe could only do it with the support of low castes. Rajputshad to negotiate with the panchayat (local government)leaders, many of whom are from the low castes and had toconcede the responsibility for a state-run grocery store orFair Price Shop, chairmanship of a local developmentcommittee, as well as concede control of a local primaryschool. The government’s welfare schemes are operatedthrough the local self-government, which is in control ofthe Rajputs. This has made low castes associate with theRajputs in order to reap the benefits of the schemes.Hence change in the political structures with the forma-tion and popularity of the low caste parties has furthercontributed to the independence of the low castes fromthe upper castes.

Marketization has, however, created a new group ofsubaltern from people who have failed to convert capitalfrom their traditional field to the new economic field. TheBhumihaar families who stayed back in the village havefaced difficult times and are now economically poor.Their symbolic power has diminished because they do notown sufficient land. Markets have also not offered oppor-tunities to many Brahmins. The Brahmins ofChanarmapur were not conversant in Sanskrit and did notown land because traditionally their survival was basedon the alms from landlords during the harvest season.Although they arranged with other Brahmins to carry outrituals for their patrons, they never carried out religiousrituals themselves. The new market economy has re-stricted the idea of alms and has only offered opportuni-ties to the Brahmins who conduct rituals and areconversant with Sanskrit. Some low castes, particularlyDalits, who traditionally worked in the Jajmani system,are unable to sell their labor in markets and remain poor.They were at the bottom of the erstwhile moral order andnever had sufficient economic, social, and cultural capitalto make a transition to markets. In many cases they areunder severe strain because Jajmani was also a covenantfor the sustenance of life in which right to food for sur-vival was not denied. Many low castes members whowere already old could not adjust to the dominance of thenew market logic. They found it difficult to change theirhabitus and did not like the idea of living in settings thatwere commercial and impersonal. The village has manyelderly who refuse to live with their children in cities andprefer hardships of the village life to the relative materialcomfort of the city.

Consumption and Shifting Symbolic Power

As a result of marketization, many practices of depen-dence on the high caste, especially Bhumihaars, havechanged in the past three decades. The symbolic violenceperpetrated by the higher castes ceases to be visible as theold feudal ties wither away. However, this is a slow anddifficult process of change. Ramavtar, an elderly low caste,knows how tough it was for him to send his son to city tofind a job. “He ran away,” he had said to his patron with asullen face. Ramavtar was too poor to afford the wrath ofhis patron who was angry because Ramavtar’s son has es-caped from his domain of power. Ramavtar was too oldand ill equipped to migrate. Later when his son returned,he brought gifts of a tape recorder and a suitcase to his pa-tron’s house. Ramavtar’s son had brought a tape recorderfor his family’s personal use. But he was pragmatic and in-telligently offered the gift to his patron as a future invest-ment. The tape recorder was a buffer during the transitionperiod. We also heard stories of how the son of a low castevillager returned from Kolkata with a new Raleigh bicycle.The poor person rode it only once, and the patron was furi-ous. “How can a low caste ride on a bicycle as his patronwalk on foot?” said a high caste villager. Before the mattergot out of control, the father took his son’s bicycle to hispatron’s house-front and offered it to him as a gift.Ramavtar recounted a number of such episodes. However,with subsequent trips to the village, the size and quality ofgifts deteriorated. In the meantime, Ramavtar’s son earnedenough money to construct a house, and finally he freedhimself and his family from the umbilical cord of theJajmani patronage system.

Ramavtar’s son no longer goes to the house of his ances-tor’s landlord. He perceives that a visit to Bharat Singh’shouse-front is tantamount to carrying on the ancestral tradi-tion of Jajmani. Many low castes in the village believe thatvisits to a landlord’s house-front furthers the traditional hi-erarchy enacted through the ritual of the landlord sitting ona cot or chair and low castes being made to either squat onthe ground or stand in front of him. This is now consideredan insult by the younger generations of low castes. Thisperception has led to rejection of the practice by youngerlower castes and a resulting subversion of the symbolicpower wielded by the upper castes.

The reluctance of a low caste to visit the house-front ofa high caste villager results in dismay and frustrationamong the old elite. It is very much evident as elderlyBhumihaar Bharat Singh complained,

Now no low caste goes to any high caste house-front. Onthe contrary we have to go to their house-front to requestthem to come to the agricultural field for work. It was so dif-ficult to get the agricultural work done that I gave all myland on rent to Sipujana [a vowel ‘a’ is attached at the endof a name as a mark of contempt] of Chamtoli [the hamletof the Chamar or low caste].

482 JOURNAL OF CONSUMER RESEARCH

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jcr/article-abstract/42/3/472/1820435/Status-Caste-and-Market-in-a-Changing-Indianby Bibliotheque Cantonale et Universitaire useron 10 October 2017

Bharat believes that the avoidance of their house-front bythe low caste signifies a challenge to the local hierarchy.He argues that such defiance has coincided with changes inthe farming practices of the village and marketization. Inorder to avoid daily or routine visits to low caste house-fronts to recruit laborers, the high castes prefer contractfarming. Land is offered to low caste for rent of about Rs4000/acre (around $67/acre) for one crop season (there aretwo crop seasons in a year). This assists in maintainingmarket-based transactional relationships and helps the highcastes to maintain distance.

Marketization is leading to accumulation of wealth forsome and is creating a new consuming class among the af-fluent of the lower castes. Far from becoming an order thatis equal, we see a shift to a new hierarchy in which eco-nomic capital plays a significant role in creating symboliccapital. A part of economic capital finds expression in de-monstrative expenditure. According to Bourdieu (1990,131), “demonstrative expenditure (as opposed to ‘produc-tive expenditure, which is why it is called ‘gratuitous’ or‘symbolic’) represents, like any other visible expenditureof the signs of wealth that are recognized in a given socialformation, a kind of legitimizing self-affirmation throughwhich power makes itself known and recognized.” In pop-ular understanding, informants used their Ghar-Duar(house-front) to describe a family’s status, saying, for ex-ample, “ghar-duar ke theek ba log—the family is well off.”Demonstrative expenditure on the house-front is a sourceof distinction within the village hierarchy. The house-frontappearance is affected by different conspicuous decorativeobjects. For example, erstwhile Bhumihaar landlords keptelephants and horses in their house-front area, along withfurniture, as representations of taste and culture of theowner and the family residing in the house. Even todayerstwhile feudal landlords keep tall oxen at their house-fronts. The oxen do not have any functional use becausetractors are now used for tilling land (see also Miller2010). The physical size of the house-front and the locationof its material objects is a “natural refinement” (Bourdieu1984), termed in the local parlance as khandani or badka(i.e., “cultured” or “big”). Most of the high caste familiesdecorated their house-fronts to express wealth and power.

Low caste villagers now attach great significance to theirhouse-front. In Chanarmapur, we came across a Dusaadh(a low caste) family with a red velvet sofa kept inside asmall palani (a hut made of dried grass) at their house-front. When we inquired, the head of the household told usthat good furniture increases the value of a house-front. Hesaid that the aesthetic appeal of a house-front increaseswith furniture. The idea and the widespread success of thispractice are further expressed by the increase in the numberof furniture shops at local fairs. Sofas and chairs, in partic-ular, are seen as modern furniture and thus represent con-temporary status practices, and they are considered to be ofhigher aesthetic value.

In the hamlet of blacksmiths we observed a two-storybuilding being constructed by Janam Sharma, a low castevillager. Three to four years ago there was a small thatchedroof house in its place. Janam was a carpenter who madeand mended house furniture and plows under the Jajmanisystem. He later migrated to a plant construction site inMumbai and started working as a carpenter for a wage.While working at the site, in the 1990s he got an opportu-nity to work as a supplier of carpenter labor. Since his casteis traditionally engaged in woodwork, he could manage toassemble a team of carpenters comprising distant relativesand men of his caste for one of the largest constructionfirms of India. It was also a period when the economy hadopened up and there was a boom in the construction indus-try. This business helped him to make a good amount ofmoney. He could convert his capital from an earlier fieldinto relevant forms of capital in the new field (Bourdieu1979). While Janam has now retired, his sons continue tolook after the business. His sons live in Mumbai with theirfamilies and have bought flats there. When we asked thepurpose of constructing such a big house in the village,Janam told us, “It is our mother land. In the end you haveto come here. All my life I lived a wretched life. Now wehave money. I constructed this house so that people wouldcome to my house-front and they would feel good aboutme.”

Consumption of idols during the festival of Chath at thevillage pond-bank serves as another marker of social hier-archy and of caste-based tension. By the side of the pond-bank is a series of small pyramidal stepped structures ofidols of the Chathi goddess. On the northern side of thepond are two rows of idols, relatively larger in size andpainted in different shades of white and off-white. The firstrow of idols belongs to different Brahmin families; the sec-ond belongs to Bhumihaars. A short distance from thesetwo rows of high caste idols are the boldly red and green-colored idols of low caste Nonia, Gond, Dhobi, Dussadh,and Chamar villagers. Rajput’s idols are located at somedistance from the idols of the Brahmins and Bhumihaars.Their idols are closer to those of the lower caste. Thepond-bank is a threshold place that was earlier controlledby the high caste Hindus, and only they constructed perma-nent idols of the goddess there. However, in recent years,low caste consumers have changed this ritual through theirparticipation, construction, and consumption of permanentidols. There are fewer low castes’ idols compared to thoseof the high castes, but now they construct their own idolsand do not pray to the idols of the high caste villagers.

The low caste groups not only imitate the high caste buthave also created their own novel codes of consumptionthat are distinct from those of the upper castes. These novelcodes of consumption are, as Bourdieu (1990, 119) ob-served, “exhibitions of symbolic capital” that allow thelower castes to challenge the upper caste domination. Agood illustration of such an exhibition is found in the

VIKAS ET AL. 483

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jcr/article-abstract/42/3/472/1820435/Status-Caste-and-Market-in-a-Changing-Indianby Bibliotheque Cantonale et Universitaire useron 10 October 2017

change in the shape of the idols at the pond-bank. The idolsof the low caste maintain the traditional nonanthropomor-phic geometric form of a stepped pyramid. However, thedesign of the idols of the lower caste Chamar is circular,which is a deviation from the prevalent high caste squaredesign. In the circular stepped pyramid form of the goddessidols of the Chamar are provisions made to receive offer-ings as well as lamps that are not present among the highcaste idols. Carvings and sketched patterns on the idols oflow caste consumers make them more trendy and conspic-uous. Lastly, the color and texture of the surface finishmakes their idols stand out in the crowd. In contrast to thelight color and matte finish of the high castes’ idols, thelow castes’ idols are painted in bright colors with a glossyfinish. Jyoti, an old female Bhumihaar teacher, lamented,

The low castes color and decorate their idols to express thatthey are better; that they are equal to us. Through color theyexpress that they are colorful. Earlier they were under pres-sure of the high castes. Low castes were suppressed. Theywere not allowed at the pond-bank. Now they are free. Theytry to outdo us. This year I observed that Teli and Loharhave erected (a) beautiful Chandani (tent like structure)with jhalar (flounce or frills). I also observed an arrange-ment of projector at the pond-bank. Videos were displayedthroughout the night. There are also cases of installing an-thropomorphic idols on the conventional stepped pyramididols. I believe that there is a quest among the low castesthat they can worship goddess in a better way compared tothe high castes.

These comments represent a put-down of lower caste con-sumption practices as being gauche and characteristic ofnouveau riche consumption. According to low caste con-sumers, the color and deviation from the usual form is asign of a shift in the village hierarchy. Sunita, a middle-aged female Nonia, informed us, “We paint idols withdeep color to decorate it. Deep color looks beautiful. Youcan see it from a distance.” The light color of high casteconsumers symbolizes simplicity, and the bright colors ofthe low castes symbolize happiness and newfoundprosperity.

Rejecting and Embracing Bonds of Sharing

The old moral economy functioned at multiple levels ofsustenance. The quest to achieve independence is furtheredby a rejection of other relics of Jajmani including those ofthe orchard that was a site for collecting cooking fuel. Thedaily requirement of fuel of low caste households was metby collecting twigs and dry leaves from the orchards of thehigh caste. The fuel collected in the orchard was not en-tirely free. The price of collecting fuel was to abide by thenorm of reciprocity and work for the high caste owner forlow or no wages. The deepening of market ties haschanged this economic field. Subordinate groups with

higher disposable incomes from market-based wages or en-trepreneurial ventures now prefer to buy liquid petroleumgas (LPG) cylinders from the market. Lakhan Bo, a mid-dle-aged low caste woman, observed that “recently threefamilies in Dhuniya Patti [a section of her hamlet] pur-chased gas cylinders for Rs 5000 each [LPG stove and cyl-inder for around $83].” Members of these families work innearby cities and have saved enough to make this transi-tion. Rather than collecting so-called free twigs, spendingmoney to buy LPG is the preferred route to freedom.Lakhan Bo reiterated that the high caste villagers do not al-low access to their orchards to collect fuel without an ex-pectation of service and indebtedness in return. Thiscreation of dependency and symbolic power is recognizedby the low caste, and the market is seen as a freer alterna-tive that gives them more autonomy.

Chath rituals at the pond-bank are also importantmarkers of marketization in the village. In the past, thelandlord provided all ritual objects and the new clothes thatlower castes wore to participate in Chath festivities.Mahato, a low caste, informed us,

In the past the landlord provided everything to observeChath—a cotton sari for my wife and cotton handloom clothfor my children and me. The local weaver provided cloth forfree to the landlord that he passed on to us. Salman Mia, thevillage tailor, stitched bush shirts and pajama for my sons.The times have changed.

Mahato further informed us that lower castes do not go tohigher castes for clothes anymore. In his own case, hisson works in a city as a mason and earns enough money tobuy clothes for himself and his family. In fact, Mahatoadded, “my son purchases branded jeans trousers and apolo T-shirt now. He is no more interested in tailor-stitched clothes.” With the fading away of the Jajmanisystem and deepening of marketization, ready-madeclothes are new markers of freedom. Moreover, T-shirtsand jeans are interpreted as modern market-based attireand more sought after than the traditional Indian shirt andpajama (also see Nakassis 2012). Marketization has al-lowed them to use their freedom to become socially mo-bile and has resulted in a greater urge to consume objectsthat were denied to them for generations. It has also meantthat the control exercised by the high caste landlords onthe socioeconomic system is fading away. This has con-tributed to a greater democratization of consumption, aprocess that was absent for most low castes under theJajmani system.

However, there are some old and poor low castes whoare still dependent on the old norms of sharing with theirpatrons. The new logic of markets has left them particu-larly worse off because some high castes refuse to sharetheir wealth with the poor because they are relatively inde-pendent of social obligations of the local field. SatendraSingh, a Bhumihaar who works in a nearby city and whose

484 JOURNAL OF CONSUMER RESEARCH

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jcr/article-abstract/42/3/472/1820435/Status-Caste-and-Market-in-a-Changing-Indianby Bibliotheque Cantonale et Universitaire useron 10 October 2017

children work in Mumbai, is not dependent on the lowcaste in the village for his survival. He said,

We are not interested in the orchard. We do not get benefitfrom it. The low castes use our orchard. The low casteswould not do any work for us but they graze goats, collectfuel and consume fruits in my orchard. They steal fruits. Weget nothing. We cannot do anything. Do you think that I willgo to the village to guard [my] orchard or my sons would goto the village leaving jobs in the city? No, it is not possible.We can buy and eat much more and better quality mangoesin the city. It is better to plant Mahogany and Sissoo insteadof fruit trees.

It is evident that Satendra wants to keep away low castesfrom accessing his orchard with the withering of the oldpatron–client ties. While he could stop the low castes fromaccessing his orchard by constructing a boundary wall orby posting a guard, both options are too expensive. Hencehe decided to plant non–fruit-producing commercial trees.In this way he can both stop low castes from using his or-chard and increase the commercial value of his assets. Thehigh castes’ actions to privatize and to keep away lowcastes from the orchard, not even allowing them to collectdry leaves, also creates situations of conflict. In one case,Sanjay Singh stopped low caste Suganti from collectingfuel from his orchard. Sanjay Singh, a Bhumihaar landlord,shouted at Suganti, “Not for once did you come to myhouse-front during the month of bhado [June-July]. When Iwent to your house during June-July, the transplanting sea-son of paddy, you refused to come, and today you are col-lecting dry wood from my orchard.” From the top of theopen balcony we observed the 38-year-old Sanjay shoutingat the old woman as her four grandchildren looked in an-other direction. “I was sick with unpredictable bouts ofstomach-ache. I am old now, and I do not have strength leftfor agricultural work,” defended Suganti. “But you do notfeel weak when you collect wood and graze goats in my or-chard,” Sanjay shouted back. Suganti responded, “The or-chard is yours so what; many generations of my ancestors‘melted’ into yours (while serving them).” The orchard isthe private property of Sanjay, and yet Suganti wants toconsume the dry wood produced in this place because it isconsidered an ambiguous threshold. In the conversationshe reminds Sanjay that she can collect and consume woodby virtue of the intergenerational relationship betweenthem, which he refuses to consider. Thus the poor lowcastes, who have not been successful in making the transi-tion to the market economy, continue to be dependent onothers who are better off.

Interdependence creates the need for sharing, and socialrespect is accorded to high as well as low castes willing toshare their good fortunes with others without the coercionof the Jajmani system. Even though creating distinction byconstructing boundary walls is the new norm of exclusivityamong the high caste and the rich, there is an important

low caste exception in the village. Salim, now a successfulconstruction contractor, has not constructed any boundarywall around his house in spite of having sufficient space todo so. Instead we found many red-colored plastic chairs onhis house-front. He has local prestige, and both low andhigh caste villagers come to his house-front and spendtime. He is considered a compassionate person and a saviorof the low caste and poor. Low caste poor villagers ofChanarmapur often come to meet Salim at his house-frontin order to seek work opportunities. He offers them un-skilled work on a monthly basis. His workers are primarilyfrom the low castes, but some high castes also find em-ployment in his business. Low and high caste villagersboth value the suggestions and advice of Salim more thanthat of high caste residents. It is common to hear inChanarmapur that “Although Salim is a Dhuniya, highcaste Hindus go to his house-front. There is always some-one or the other sitting at his house-front.”

Salim owns an electric generator, a sound box, and em-ploys electricians. During Chath he offers his generatorand electricians to provide light during the night and inearly morning on the penultimate day of Chath. SatendraSingh, a Bhumihaar and a popular physician in the area,told us, “Salim is a very good person. He is also very gen-erous. Every year, he spends Rs 20 000 (around $330) toinstall hand pumps on roadside temples.” Similarly, wefound evidence of his generosity in a meeting organized inthe village to raise funds to renovate the village temple. Alocal politician had called this meeting in which both thehigh and low castes participated. Salim declared that hewould contribute Rs 25 000 (around $415) and promisedthat he would provide masons for free. Such novel acts ofphilanthropy help Salim to generate symbolic capital andto create a sense of solidarity among the low castes. In thisvillage the prevalence of the old, or Jajmani-based, andnew, or market-based, dispositions create an “ambiguousgestalt” that means symbolic capital requires market-basedsuccess and sharing of wealth as it prevailed in the tradi-tional social order (Bourdieu 1979).

In the course of the fieldwork it was common for thelow castes to offer us tea or food when we visited theirhouse-front. The low caste villagers were happy when wedrank water or tea and ate food offered by them. In sociallydivided Chanarmapur, drinking water or tea and consum-ing food offered by the low caste are still considered tabooby many high castes. Many elderly high castes did not ap-preciate our consumption of food at the low caste house-fronts. With great dismay Bharat Singh told us, “We wouldprefer if you do not go to low castes’ house-front. Even ifyou have to go to their house-front, you should not eat ordrink there.” They would, instead, advise us to come totheir home and eat. Any public sharing of food with thelow caste was in violation of the caste norms and reducedthe distance between the high and low castes. However, re-ducing social distance for the low caste by sharing food is

VIKAS ET AL. 485

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jcr/article-abstract/42/3/472/1820435/Status-Caste-and-Market-in-a-Changing-Indianby Bibliotheque Cantonale et Universitaire useron 10 October 2017

an important part of the process to reconfigure symbolicpower in the village.