Seed dispersal versus seed predation: an inter-site comparison of two related African monkeys

Transcript of Seed dispersal versus seed predation: an inter-site comparison of two related African monkeys

Vegetatio 107/108: 237-244, 1993. 7". H. Fleming and A. Estrada (eds). Frugivory and Seed Dispersal: Ecological and Evolutionary Aspects. © 1993 Kluwer Academic Publishers. Printed in Belgium.

237

Seed dispersal versus seed predation: an inter-site comparison of two related African monkeys

Annie Gautier-Hion, Jean-Pierre Gautier & Fiona Maisels CNRS URA 373 & University of Rennes, Station Biologique, 35380 Paimpont, France

Keywords: C.(mona) pogonias, C.(mona) wolff, Diets, Fruit availability, Gabon, Zaire

Abstract

C. pogonias and C. wolff plant diets were studied in two sites, in Gabon and Zaire and compared with fruit availabilities. Monkeys in Gabon were found to be mainly fruit pulp-eaters while monkeys in Zaire were alternately seed-eaters, aril-eaters or leaf-eaters. These differences were related to differences in the availability of fruit categories: fleshy fruits were found to be much more abundant in Gabon than in Zaire forests. As a result, monkeys in Gabon were found to be mainly seed-dispersers while monkeys in Zaire were found, to a large extent, to be seed-predators. Results are discussed in terms of phenotypic flexi- bility in monkey feeding behavior, diversity of plant-monkey interactions, geographic variability of keystone plant resources, and their implications for forest management practices. The low availability of fleshy fruit species in Zaire is hypothezized to result from the poor soil conditions.

Introduction

The importance of frugivory in tropical rain for- ests and the role of large vertebrate frugivores in the dynamics of forest regeneration is now well established (e.g. Emmons et al. 1983; Leighton & Leighton 1983; Terborgh 1983, 1986a, b; 1990; Dubost 1984; Howe 1984; Estrada & Fleming 1986). To date, mammalian frugivory has been comprehensively studied at only a few sites (e.g. Charles-Dominique etal. 1981; Janson 1983, Howe 1990 for the neotropics; G autier-Hion et al. 1985a, 1985b, for Africa). However, we do not know to what extent what happens in one rain forest can be generalized to another or even to other parts of the same forest block.

This study compares our quantitative observa- tions on the plant feeding ecology of two related monkeys inhabiting rain forests, in Gabon and Zaire. In both study areas, monkey plant diets

were analysed and compared with fruit availabil- ities and the effect of consumers on seeds was studied. The observations from Zaire are still in progress whereas the other data come from our previous work (Gautier-Hion 1980, 1990; Gauti- er-Hion et aL 1985a, b; Gautier-Hion & Micha- loud 1989).

Methods

Study sites

The study sites are close to the equator. Makokou in N-E Gabon, lies at 0 ° 4' N, and Botsima, (Sa- longa National Park) in the Central Zaire Basin, at 1 ° 15' S. The two sites are ca. 1050 km apart (respectively 12 ° 46' E and 22 ° E). Whereas the tropical rain forest at Makokou has been inten- sively studied for three decades, forests of the

238

Central Zaire Basin remain rather poorly known. The Makokou site is mainly covered with sea-

sonal evergreen rain forest. In this forest, the Le- guminosae is most numerous in tree species (Re- itsma 1988) and in individuals (Caball6 1978). The Botsima site is a mosaic of riverine forests on alluvial levees and mature forests on hydromor- phic soils. As in Gabon, Leguminosae is the most species-rich group in the tree stratum.

The mean annual rainfall is comparable at both sites: 1755 mm at Makokou (Gautier-Hion et aL 1985a); 1756 mm at Ikela, a locality situated 120 km from Botsima (Ergo & Halleux 1979). Both sites undergo two rainy seasons and two dry sea- sons ( a small dry season occurring around Jan- uary, February and a main dry season in June and July).

The monkeys and their diets

At each site, one arboreal Cercopithecus species was studied: C. pogonias in Gabon and C. wolff in Zaire; the two species are representatives of the mona superspecies.

In this study, only the quantitative composition of diets in terms of food plant categories is con- sidered. In Gabon, quantitative data come from the analysis of stomach contents sampled every month but April (a total of 52 stomachs; Gautier- Hion 1980). In Zaire, all data come from direct observations (a total of 3293 feeding records over the annual cycle). They were taken according to the frequency method which gives the relative im- portance of each food category in the diet (Stru- hsaker 1975). The two methods are liable to sys- tematic errors; they are nevertheless reliable for examining gross differences in feeding behaviour (Clutton-Brock 1977).

Fruit availability

Fruit availability was assessed as follows (Gauti- er-Hion et al. 1985a). A 5 km-trail in Gabon and in Zaire was traveled every second week and numbers of fruiting species and of fruiting indi- viduals were noted. Results are expressed as the number of fruiting species per month and as the mean monthly number of fruiting sites per 100 m of trail. The availability of the following mature food types was considered in this study: fleshy fruit (either drupes or berries), fruit with arillate seeds, and pods of legumes.

Consumer effect on seeds

Monkeys are regarded as seed dispersers when they eat only the pulp or the aril of seeds and disperse the seeds by endo- or synzoochory. They are considered as predators when they destroy the seeds by eating them (in the case of seeds in pods or capsules) or by eating both the pulp and the seed (in the case of immature fruits). They are regarded as 'neutral' when they simply discard the intact seed under the parent tree.

Results

Mean annual composition of monkey diets

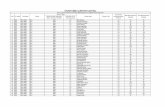

The diets of the two monkeys differed greatly in their overall composition (Table 1). The pulp of mature fleshy fruit formed the main part of the diet of C. pogonias in Gabon ( an annual mean of 77~g) followed by arils (18.4~o). Whatever the period, flower and leaf consumption as well as the consumption of seeds were only occasionally ob- served (an average of 4.5~o).

Table 1. Relative intake (in ~ ; + standard deviation) of the different food categories during the annual cycle by C. pogonias (Gabon) and C wolff (Zaire).

Sites Fleshy Arils Legume Other Leaves Flowers fruits seeds seeds

Gabon 77.1 +_ 19.87 18,4 + 16.70 2.4 i 4.57 2.1 + 2.18 Zaire 4.2 _+ 3.38 27.4 +_ 20.12 20.0 _+ 25.38 7.33 _+ 4.69 29.5 _+ 24.30 11.41 +_ 19.0

239

In Zaire, leaves (29.5~o), seeds (27.3~), and arils (27.4~o) constituted the bulk of the annual diet of C. wolff while the pulp of fleshy fruit only accounted for 4.2 ~o. Most of the seeds were taken from pods of legumes.

Seasonal variation in diets

Whatever the month, the diet of C. pogonias was dominated by fleshy fruits (range: 44~o to 98~o; Fig. 1). The decrease in fruit consumption ob- served around the main dry season was corre- lated with an increase in the consumption of both arils and leaves (Spearman rank correlation, p<0.05 and p<0.01 respectively).

In Zaire, the diet of C. wolff varied greatly throughout the year (Fig. 1). Diet was alternately dominated by leaves (a maximum of 76 Yo in Jan- uary), leaves and flowers (32yo and 51 ~o respec- tively in March), arils (70~o in May, 43 ~o in July), or legume pods (60~o to 57.5~o from August to November). Whatever the period, the consump- tion of mature fleshy fruit was low, with monthly percentages reaching a maximum of 10 ~o in July. The consumption of seeds of immature fleshy fruit took place year round (maximum = 15~o in De- cember).

Leaf consumption was negatively correlated with the consumption of legume seeds (p < 0.01) and of arils (p < 0.05). The increase in consump-

Fig. 1. Relative intake (in ~ ) of plant food categories throughout the year for the two monkey species.

240

25

20.

15,

10

5.

0.

1,41

I; o'

2 4 6 S 10 12

MONTHS

Fig. 2. Patterns of fleshy fruit production in terms of the num- ber of fruiting species and of the mean number of fruiting sites/100m. Zaire: circles; Gabon: squares.

16

14

12

10

6

4

~ 2 C

2 4 6 8 10 12

!,i ,2.

0 .. 2 4 6 8 I0 12

MONTHS

Fig. 3. Patterns of legume pod production in terms of the number of fruiting species and of the mean number of fruit- ing sites/100m. Zaire: circles; Gabon: squares.

tion of legume seeds was correlated with an in- crease in fleshy fruit intake (p < 0.01).

Fruit availability

The two study sites differed in fruit availability. For fleshy fruits, both the monthly number of fruiting species and the mean number of fruiting sites were significantly higher in G a b o n than in Zaire (p>0 .001 , Wilcoxon matched pair test; Fig. 2). A maximum of 24 species simultaneously produced mature fleshy fruit in G a b o n vs a max- imum of 13 in Zaire, with the minimum being 9 and 2 species respectively. The number of fruit- ing sites per 100 m per month ranged from 0.1 to 1.2 in G a b o n versus 0.03 to 0.5 in Zaire. For the pods of Leguminosae (Fig. 3), results were simi- lar at the two sites, both for the maximum num- bers of fruiting species and of fruiting sites ( p > 0 . 0 5 in both cases). Finally the number of species producing arillate seeds per month (Fig. 4) was greater in G a b o n than in Zaire (p<0 .05) , while the number of fruiting sites was higher in Zaire than in G a b o n (p < 0.05).

~ S

4

~ 2

0 i i g i lb l~ b.

in

~ ,1.

~ o

MONTHS

Fig. 4. Patterns of arillate seed production in terms of the number of fruiting species and of the mean number of fruit- ing sites/100m. Zaire: circles; Gabon: squares.

Fruit availability and monkey diets

In Gabon, the high annual consumption of fleshy fruits was related to their overall availability.

241

1417.

120.

10oi

~, so. 6o.

~, 20,

50

2 4 6 8 10 12

45

40

35

30

25

20

10

5

0 '

120

2 4 6 8 L0 12

80

20

0 2 4 6 8 10 12

MONTHS

Fig. 5. Seasonal variation in plant intake by C. pogonias and availability of three food categories (circles: percent of intake; squares: number of fruiting species; triangles: mean number of fruiting sites/lOOm x 100).

However, their monthly rate of consumption was not correlated with their monthly availability either in terms of the number of fruiting species or fruiting sites (Fig. 5; Spearman rank correla- tion, p>0 .05 in both cases). Similarly, the con- sumption of arils was not correlated with the number of fruiting sites (p > 0.05). It was however correlated with the number of fruiting species (p < 0.05). The low consumption of legume seeds obviously diet not relate to their availability. In Zaire, both the availability of fleshy fruits and their rate of consumption were low (Fig. 6). Fur- thermore, the monthly rate of fleshy fruit con- sumption was positively correlated with their monthly availability both in number of species and number of sites (p < 0.05 in both cases). Sim- ilarly, the consumption of legume seeds was pos-

50

40

30

20

10

60

80-

2 4 6 8 10 12

70; 6o~ 5o~ 4o; 30~ 20~ 10~ 0'

2 4 6 S 10 12

80 i J i

60

20

1

2 4 6 8 10 12

MONTHS

Fig. 6. Seasonal variations in plant intake by C. wolff and availability of three food categories (circles: percent of intake; squares: number of fruiting species; triangles: mean number of fruiting sites/lOOm x 100).

itively correlated with the number of fruiting spe- cies and fruiting sites (p< 0.01 in both cases). In the case of arils, the consumption rate was cor- related with their number of fruiting sites (p<O.01).

Consumer effects on seeds

In Gabon, monkeys served as seed dispersers for 82~o of the species whose fruit they ate and were seed-predators for 4~o of their food species. No positive or negative effects on the seeds were re- corded for the remaining 14Yo (Gautier-Hion et al. 1985a).

In Zaire, monkeys are seed dispersers for 58 ~o of the fruit species they ate and destroyed the seeds of at least 40 ~o of the species. This included

242

all of the tree species whose fruits were only eaten when immature and all the Leguminosae. For the latter, seed predation was important in five months of the year (Fig. 1).

Discussion and conclusions

Striking differences occur between Gabon and Zaire in the diets of this pair of related species. In Gabon, whatever the season, the pulp of fleshy fruits forms the bulk of the diet of C. pogonias which can therefore be considered basically a pulp-eater. Arils complement this diet during the main dry season. In Zaire, C. wolff diet is char- acterized by a seasonal procession of different major food items; depending on the season, mon- keys may successively be considered either seed- eaters, leaf-eaters or aril-eaters. Their consump- tion of fleshy fruits remains low throughout the year.

These differences between diets of closely- related monkeys and between seasonal diets within the same population emphasize the plas- ticity of their feeding behavior. They lead to major differences in the nature of interrelations between monkeys and plants. In Gabon, pulp-eating mon- keys play an important role in seed dispersal. In Zaire, seed predation by monkeys is important especially for legumes.

Differences recorded in the relative availabili- ties of fruit types at the two sites mainly concern fleshy fruits which were found to be more abun- dant in number of species and density of fruiting trees in the Makokou forest than in the Botsima forest. They account for the huge differences in fleshy fruit intake between the two monkey spe- cies. They may also explain why dietary differ- ences between the two sites are not correlated to the same extent with the availability of plant foods. Indeed, monkeys in Zaire seasonally ad- just their diet by alternately taking the most com- mon food category. In contrast, monkeys in Gabon maintain a high intake of fleshy fruits year round; they increase their consumption of arils when available but ignore legume seeds and leaves.

Leaf-eating or seed eating could be a last resort for basically frugivorous primates. While mon- keys in Gabon suffer from fruit shortage only dur- ing a limited period, monkeys in Zaire are forced to consume seeds or leaves in the absence of fleshy fruits. Gautier-Hion (1983) previously pointed out that monkeys as a whole are more folivorous in East African forests than in Gabon, apparently as a result of a lack of fleshy fruits. This view was supported by studies of the low- land gorillas of the Lope Reserve (Gabon); these apes were found to largely rely on fruit and seeds, contrary to the folivorous mountain gorillas (Wil- liamson et al. 1990). This led Rogers et al. (1990) to conclude that 'G. g. gorilla was not strictly folivorous, except in habitats which allow it no alternative.'

Seed consumption by Cercopithecus monkeys as extensive as that observed for C. wolff has not yet been documented elsewhere, but is reminis- cent of the black colobus, Colobus satanas, in the Douala-Edea Reserve in Cameroun (McKey 1978). Seed-eating by these colobines was pos- tulated to result from the vegetation growing on the impoverished sandy soils of the Douala-Edea Reserve containing a greater concentration of toxic secondary compounds that equivalent foods growing on richer soils. As seeds are more digest- ible, richer in fats, and generally poorer in tannins than leaves, the colobus, which are mainly leaf- eaters in the Eastern African forests, avoid leaves and rely on seeds at the Douala-Edea Reserve.

As at Douala-Edea, forests in the Salonga Na- tional Park in Zaire also grow on acid sandy soils, containing very small amounts of silt and clay. These areno-ferralsols and/or ferralsols are very poor in nutrients; the humus layer is very shallow and is generally incompletely decomposed (Evrard 1968). At Botsima, poverty of the soil is indicated by the exceptionally low rates of regen- eration after clearing. It remains to be seen whether plants growing on such impoverished soils develop more toxic secondary compounds in their foliage and seeds than those found on richer soils, as suggested by Janzen (1974) and/or whether the low fleshy fruit availability in this forest results from this soil poverty.

Considering the amount of dietary flexibility in closely-related monkeys, what can be inferred about diets from gut specializations (cf. Martinez del Rio & Restrepo, this volume)? More gener- ally, is 'the high level of correspondence between food type, plant chemistry, and digestive anato- my,' previously described by Chivers & Hladik (in Chivers & Hladik 1984), the expression of actual constraints? Could such a tight correspon- dence have been overestimated because of our poor understanding of phenotypic variability due to the limited number of comparative studies con- ducted on related species, populations of the same species, and/or groups of the same population, as suggested by Hauser (1990)?

Because they stress the plasticity of the mon- keys' feeding behavior, these results highlight the geographic variability of keystone plant resources for animal populations (Terborgh 1986b; Gautier- Hion & Michaloud 1989). By highlighting the di- versity of interactions between African primates and their food plants, they warn anyone con- cerned with management practices aimed at con- serving rain forest biodiversity against accepting broad generalizations.

Acknowledgements

We are particularly indebted to Dr Mankoto ma Mbaelele, President of the Institut Za'irois pour la Conservation de la Nature, who encouraged our research in the Salonga National Park. We wish to thank Nathalie Schildwachter and the staff of Botsima Station for their help in collecting phe- nological data. The field work was supported by grants from the Minist+re de l'Environnement and the CNRS (France). Dr F. Maisels was also sup- ported by grants from the Flora and Fauna Pres- ervation Society, the Peoples Trust for endan- gered species, the Percy Sladen Memorial Fund, the Leakey Trust, Edinburgh Zoo, and the Boise Fund. Finally, we are grateful for logistic help from the Commission des Communautrs Europ- 6ennes.

243

References

Caballr, G. 1978. Essai sur la grographie foresti+re du Gabon. Adansonia. 17: 425-440.

Charles-Dominique, P., Atramentowitcz, M., Charles-Domi- nique, M., Gerard, H., Hladik, C.M. & Prevost, M.F. 1981. Les mammifrres frugivores arboricoles nocturnes d'une forrt guyanaise: interrelations plantes-animaux. Rev. Ecol. (Terre Vie). 31: 341-436.

Chivers, D.J. & Hladik, C.M. 1984. Food acquisition and processing in primates: concluding discussion. In: Chivers, D.J., Wood, B.A & Bilsborough, A. (eds.). Food acquisition and processing in Primates. Plenum Press, London.

Clutton-Brock, 1977. Methodology and measurement. In: Clutton-Brock T.H. (ed). Primate Ecology: studies of feed- ing and ranging behaviour in lemurs, monkeys and apes. Acad.Press, London.

Dubost, G. 1984. Comparisons of the diets of frugivorous forest ruminants of Gabon. J. Mammal. 65: 298-316.

Emmons, L., Gautier-Hion, A. & Dubost, G. 1983. Commu- nity structure of the frugivorous-folivorous forest mammals of Gabon. J. of Zool. Lond. 199: 209-222.

Ergo, A.B. & Halleux, B. 1979. Catalogue mondial des don- nres climatiques moyennes. Vol.lI, Fasc.I, C.I.D.A.T., Tervuren.

Estrada, A. & Fleming, T.H. (eds.) 1986. Frugivores and seed dispersal. W. Junk Pub. The Hague.

Evrard, C. 1968. Recherches 6cologiques sur le peuplement forestier des sols hydromorphes de la cuvette centrale con- golaise. ONRD, INEAC.

Gautier-Hion, A. 1980. Seasonal variations of diet related to species and sex in a community of Cercopithecus monkeys. J. An. Ecol. 49: 237-269.

Gautier-Hion, A. 1983. Leaf consumption by monkeys in Eastern and Western Africa: a comparison. Afr. J. Ecol. 21: 107-113.

Gautier-Hion, A. 1990. Interactions among fruit and verte- brate fruit-eaters in an African tropical rain forest. In: Bawa, K.S. & Hadley, M. (eds). Reproductive ecology of tropical forest plants. Mab Series, Vol.7, Parthenon Pub. Cam- forth.

Gautier-Hion, A., Duplantier, J-M., Quris, R., Feer, F., Sourd, C., Decoux, J-P., Dubost, G., Emmons, L., Erard, C., Hecketsweiler, P., Roussilhon, C. & ThioUay, J-M., 1985a. Fruit characters as a basis of fruit choice and seed dipersal in a tropical forest vertebrate community. Oecolo- gia 65: 324-337.

Gautier-Hion, A., Duplantier; J-M., Emmons, L., Feer, F., Heckestweiler, P., Moungazi, A., Quris, R. & Sourd, C. 1985b. Coadaptation entre rythmes de fructification et fru- givorie en for~t tropicale humide du Gaon: mythe ou r~alitr. Rev. Ecol. (Terre Vie) 40: 405-434.

Gautier-Hion, A. & Michaloud, G. 1989. Are figs always keystone resources for tropical frugivorous vertebrates? A test in Gabon. Ecology 70: 1826-1833.

244

Hauser, M. 1990. Speciation and adaptation in the African guenons: what we know and have yet to understand? Am. J Primatol. 20: 299-302.

Howe, H.F. 1984. Implications of seed dispersal by animals for the management of tropical reserves. Biol. Conserv. 30: 261-281.

Howe, H.F. 1990. Seed dispersal by birds and mammals: implications for seedling demography. In: Bawa, K.S. & Hadley, M. (eds). Reproductive ecology of tropical forest plants. Mab Series, Vol.7. Parthenon Pub. Carnforth.

Janson, C.H. 1983. Adaptation of fruit morphology to dispersal agents in a Neotropical forest. Science 219: 187- 198.

Janzen, D.H. 1974. Tropical blackwater rivers, animals, and mast fruiting by the Dipterocarpaceae. Biotropica 6: 69- 103.

Leighton, M., Leighton, D.R. 1983. Vertebrate responses to fruiting seasonality within a Bornean rain forest. In: Sutton, S.L., Whitmore, T.C. & Chadwick, A.C. (eds.) Tropical rain forest: ecology and management. Blackwell Scientific, Oxford.

McKey, D.B. 1978. Phenolic content of vegetation in two- African rain forests: ecological implications. Science 202: 61-64.

Rogers, M.E., Maisels, F., Williamson, E.A., Fernandez, M. & Tutin, C.E.G. 1990. Gorilla diet in the Lope Reserve, Gabon: a nutritional analysis. Oecologia 84: 326-339.

Reitsma, J.M. 1988. Forest vegetation of Gabon. Tropenbos series I. Drukkerij Veenman B.V., Wageningen.

Struhsaker, T.T. 1975. The Red Colobus. Univ. of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Terborgh, J. 1983. Five New-World Primates: a study of com- parative ecology. Princeton Univ., Princeton.

Terborgh, J. 1986a. Community aspects of frugivory in trop- ical forests. In: Estrada A. & Fleming T.H. (eds.) Frugi- vores and seed dispersal. W. Junk, Pub. The Hague.

Terborgh, J. 1986b. Keystone plant resources in the tropical forest. In: Soule, M.E. (ed.) Conservation biology: the sci- ence of scarcity and diversity. Sinauer Ass., Sunderland.

Terborgh, J; 1990. Seed and fruit dispersal. Commentary. In: Kawa, B.S. & Hadley, M. (eds.) Reproductive ecology of tropical forest plants. Mab Series, Vol.7. Parthenon pub. Carnforth.

Williamson, E.A., Tutin, C.E.G., Rogers, M.E. & Fernandez, M. 1990. Composition of the diet of lowland gorillas in Gabon. Am.J Primatol. 21: 265-278.