Scoring of Skin Rejection in a Swine Composite Tissue Allograft Model

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of Scoring of Skin Rejection in a Swine Composite Tissue Allograft Model

liagr

scicpto4btga

tabvpbjw

S

d

PsiL

JA

Scoring of Skin Rejection in a Swine Composite Tissue Allograft Model1

Marty Zdichavsky, M.D., Jon W. Jones, M.D., E. Tuncay Ustuner, M.D., Xiaoping Ren, M.D.,Jean Edelstein, M.D., Claudio Maldonado, Ph.D., Warren Breidenbach, M.D.,

Scott A. Gruber, M.D., Ph.D.,* Mukunda Ray, M.D., Ph.D.,†and John H. Barker, M.D., Ph.D.2

Divisions of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery and Hand Surgery of the Department of Surgery, and †Department of Pathology,University of Louisville School of Medicine, Louisville, Kentucky, 40292; and *Division of Immunology and Organ Transplantation,

ournal of Surgical Research 85, 1–8 (1999)rticle ID jsre.1999.5673, available online at http://www.idealibrary.com on

Department of Surgery, University of Texas at Houston Health Science Center, Houston, Texas, 77030

tion

it

ari

s

ptmhcsmptmmtmsmia

te

Submitted for publica

Background. For the first time, we define and corre-ate visual and histologic grading systems of compos-te tissue allograft (CTA) skin rejection in a large-nimal model and determine the utility of theserading systems for early diagnosis and monitoring ofejection.Materials and methods. Sixteen pairs of outbred

wine underwent transplant of a forelimb osteomyo-utaneous free flap. Group I (n 5 6) did not receivemmunosuppressive therapy. Group II (n 5 10) re-eived oral cyclosporin A, mycophenolate mofetil, andrednisone. The flap was visually inspected and pro-ocol skin biopsies were taken at frequent intervalsver a 90-day period. Visual Grades 0 (no rejection) to(severe rejection) were assigned based on skin color,leeding from biopsy site, and blister formation. His-ologic Grades 0 to 4 were assigned based on the de-ree of vasculitis, folliculitis, dermal inflammation,nd epidermal degeneration present.Results. All Group I animals progressively rejected

heir graft by Day 7. Group II grafts survived from 19nd 90 days; 93% of 115 biopsy specimens were read toe within 61 histologic score of their assigned flapisual grade. Visual assessment carried an 8% falseositive and 39% false negative rate with regard toiopsy-proven rejection. However, 81% of missed re-

ection specimens were histologic Grade 1. Biopsy,hen visually indicated, would detect all rejection ep-

Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Academicurgery, Seattle, Washington, November 18–22, 1998.

1 This work was supported in part by the Jewish Hospital Foun-ation of Louisville, KY.

2

sois

To whom correspondence should be addressed at Division oflastic & Reconstructive Surgery, Department of Surgery, Univer-ity of Louisville, 511 South Floyd Street, 320 MDR Building, Lou-sville,KY40292.Fax:(502)852-4675.E-mail:[email protected].

1

November 18, 1998

sodes when histologically Grade 1 or 2 and still poten-ially reversible.Conclusions. Visual scoring of CTA skin serves asuseful tool for initially detecting rejection, but

epeated histologic evaluation is necessary for monitor-ng the subsequent course of the graft. © 1999 Academic Press

Key Words: composite tissue allograft; skin rejection;wine; cyclosporin A; mycophenolate mofetil.

INTRODUCTION

Composite tissue allografts (CTAs) are modules com-osed of various combinations of skin, subcutaneousissue, connective tissue, muscle, bone, cartilage, bonearrow, and neurovascular tissue. These tissue blocks

ave tremendous potential clinical application for pre-ise functional and structural restoration of large tis-ue defects after birth defects, resection of large tu-ors, or trauma. Despite the introduction of new, more

otent immunosuppressants, preventing acute rejec-ion of CTAs without significant systemic toxicity re-ains a major problem in both small- and large-animalodels [1–7]. Along these lines, it has become clear

hat vascularized CTAs elicit nonsynchronized im-une responses of varying intensity among their tis-

ue components, with skin being the most antigenic,uscle of intermediate immunogenicity, bone of lower

mmunogenicity, and cartilage and tendon the leastntigenic [3, 8, 9].In marked contrast to the monitoring of solid-organ

ransplants, measurements of graft function cannot beasily utilized as indicators of CTA rejection. However,

ince CTAs are not hidden from view (as are visceralrgan transplants), rejection of the graft might be eas-ly detected and monitored via visual inspection of thekin, which would be expected to be the first tissue0022-4804/99 $30.00Copyright © 1999 by Academic Press

All rights of reproduction in any form reserved.

iprcdblmamtmsbCchcc

maCMfmaltehr

ldamtoaiw(

c(rocno

taefGcft

fha

cvivaceasuttipp3

csm3rthrlss

fss

p2vsi

2 RC

nvolved in the rejection process. In an attempt torovide a means for standardization and comparison ofesults between protocols, Buttemeyer et al. [3] re-ently developed a histopathologic grading system forefining the severity of rejection in the skin, muscle,one, and articular cartilage components of rat hindimb allografts immunosuppressed with either tacroli-

us or cyclosporin A (CsA). This system was based onpreviously developed scheme for evaluating cardiacuscle rejection [10, 11], as well as on prior descrip-

ions of CTA rejection in other rodent and primateodels [1, 9, 12–14]. To our knowledge, a reproducible

coring system for quantifying skin rejection has noteen previously described as part of a large-animalTA model. The purpose of this report is to define,

orrelate, and assess the clinical utility of visual andistologic grading systems for skin rejection in a por-ine, brachial-artery-based, radial forelimb osteomyo-utaneous flap CTA model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals. Thirty-two age- (6–8 week old) and size- (13–24 kg)atched, outbred farm pigs were used in our study and cared for in

ccordance with guidelines established by the Institutional Animalare and Use Committee of the University of Louisville School ofedicine. Different farms for donors and recipients were requested

rom the supplier to assure that the animals were unrelated. Ani-als were housed in separate cages in light-, temperature-, and

irflow-controlled rooms and were fed standard diets and water adibitum. Following an initial physical examination, baseline labora-ory tests were performed (complete blood count with differential,lectrolytes, and liver function tests) to assess the animals’ generalealth. Pretransplant cross-matching was performed for each donor-ecipient pair to avoid hyperacute rejection.CTA model. Orthotopic allotransplantation of a right radial fore-

imb osteomyocutaneous free flap was performed as described inetail previously [15]. In brief, flaps were based on the brachialrtery and cephalic vein and consisted of the flexor carpi radialisuscle, a segment of the median nerve including its branch to the

ransplanted muscle, a segment of the radial bone, and an island ofverlying skin extending from the craniomedial to the craniolateralspect of the right forelimb. Following skin closure and wound dress-ng, a fiberglass cast was applied to the operated forelimb. A windowas created in the cast to permit inspection and biopsy of the graft

Fig. 1) until the cast was removed 3 weeks postoperatively.Experimental groups and immunosuppressive protocol. CTA re-

ipients were randomly assigned to one of two groups: Group Icontrol; n 5 6) and Group II (treatment; n 5 10). The control groupeceived no immunosuppression, while the treatment group receivednce-daily oral CsA, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), and prednisoneombination therapy as previously described [15]. Drug doses wereot adjusted based on the clinical progress of the animals, despite theccurrence of rejection.

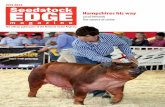

FIG. 1. Three of 5 visual and histological grades of rejection of co

JOURNAL OF SURGICAL RESEA

ink skin color, no blister formation; histologically (right), no vasculitis,(middle): visually (left), red skin color, no blister formation, bleeding

asculitis, mild-to-moderate folliculitis, dermal inflammation, and mild ekin color, no bleeding from biopsy site (arrow), blister formation positivnflammation, and epidermal degeneration.

Postoperative care. All recipients were followed for 3 months forhe occurrence of acute rejection, graft loss, or death. Rejection wasssessed clinically by daily visual inspection of the flap skin by twoxaminers. Skin biopsies were performed on Days 0 (immediatelyollowing revascularization), 2, 4, 7, 10, 14, 21, 30, 45, 60, and 90.raft survival, defined as time to flap cyanosis and sloughing (indi-

ating complete rejection), animal death, or the end of the 3-monthollow-up period were considered study endpoints. A complete au-opsy was performed in all cases.

Histopathology. Skin biopsies were initially fixed in 10% bufferedormaldehyde and then transferred to and stored in 70% ethyl alco-ol. For analysis, the tissue sections were stained with hematoxylinnd eosin.

RESULTS

Group I. CTA flaps in all control pigs demonstratedomplete rejection with necrosis on Day 7. Based on theisual and histologic progression of skin rejection notedn these animals during their 1-week survival period,isual and histologic scoring systems were formulatednd are enumerated in Tables 1 and 2 and Fig. 2. Skinolor, presence or absence of blister formation, andxtent of bleeding from biopsy site were easily detect-ble, clinically relevant parameters selected for visualcoring (Table 1), and the severity of vasculitis, follic-litis, dermal inflammation, and epidermal degenera-ion was used for histologic scoring (Table 2). As rejec-ion progressed, the character of the inflammatorynfiltrate changed from predominantly mononuclear toolymorphonuclear, with nuclear fragmentation, apo-tosis, and vascular thrombosis appearing with Grade(moderate-to-severe) rejection.Group II. Table 3 gives the graft survival times,

ause of graft loss, and visual and histologic grades ofkin rejection noted on final examination of the treat-ent group at the end of the study period. One pig (No.

) died from pneumonia on Day 19 without signs ofejection and one (No. 4) from an anesthetic complica-ion during biopsy on Day 30 with visual Grade 0 andistologic Grade 1 rejection. Two flaps were lost toejection on Days 25 and 29 (Nos. 1 and 2, respective-y). The remaining six animals survived the 3-monthtudy period with viable flaps as judged by visual in-pection.Correlation of visual and histologic scoring systems

or CTA skin rejection. A total of 115 skin biopsypecimens were obtained from the 16 pigs during thetudy, 26 from Group I and 89 from Group II. Figure 1A–E) depicts the spectrum of histologic grades re-orded for biopsy specimens according to the visual

osite tissue allograft pig forelimb flaps. Grade 0 (top): visually (left),

H: VOL. 85, NO. 1, JULY 1999

(c

mp

folliculitis, dermal inflammation, or epidermal degeneration. Grade(11) from biopsy site (arrow); histologically (right), focal moderatepidermal degeneration. Grade 4 (bottom): visually (left), blue/purplee; histologically (right), severe/necrotic vasculitis, folliculitis, dermal

gtotirfdswGa3to

riob5slw61ff

pGtGbdas

tr(radwb1c1cebvhacsetslsrcroc

4 RC

rade assigned to the graft at the time the biopsy wasaken. As can be seen in Fig. 1A, acute rejection wasngoing in 21 (39%) of 54 skin biopsy specimens ob-ained from flaps which appeared normal on visualnspection. Of the 17 biopsies with histologic Grade 1ejection, 3 were Day 0 specimens and 9 were obtainedrom grafts that had demonstrated prior visual evi-ence of rejection ($ Grade 1). In the remaining 5pecimens from two pigs (Nos. 2 and 8), acute rejectionas subsequently detectable by visual criteria ($rade 1) when the histologic grade was 2. Finally, inll 4 biopsies with visual Grade 0/histologic Grade 2 or, rejection was detectable by inspection of the graft athe time of prior biopsy from the same animals dem-nstrating the same or lower histologic grade.Of 23 biopsy specimens in grafts with visual Grade 1

ejection, 4 (18%) had no evidence of rejection histolog-cally (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, these specimens werebtained from three grafts which did indeed developiopsy-proven histologic Grade 1 or 2 skin rejection 3 todays later. In contrast, 7 specimens (30%) demon-

trated a more advanced rejection grade (2 or 3) histo-ogically. Twenty (96%) of 21 biopsies taken from flapsith visual Grade 2 rejection were noted to be within1 histologic grade on pathologic examination (Fig.C). Only a single specimen was found to be rejection-ree by histologic criteria. Finally, specimens obtainedrom grafts with visual Grades 3 and 4 were highly

TABLE 1

Visual Scoring System for Skin Rejectionof a CTA Flap

Grade POD No.a Color

BleedingBiopsy

siteBlister

formation

0 0–2 Pink 111 —1 2 Slight red 111 —2 2–4 Red 11 —3 4 Red/purple 1 1/—4 7 Blue purple — 1

a POD, postoperative day.

TAB

Histological Scoring System fo

Grade POD No.a Vasculitis

0 0–2 None1 2 None/mild2 2–4 Moderate focal

JOURNAL OF SURGICAL RESEA

4 4–7 Severe/necrosis Sev

a POD, postoperative day.b Focal necrosis may be present.

redictive of the presence of moderate to severe ($rade 2) histologic rejection (Figs. 1D and 1E). In fact,

he biopsy specimens with visual Grade 3/histologicrade 1 and visual Grade 4/histologic Grade 2 wereoth taken from the same pig (No. 7) at the time ofevelopment of a large seroma within the flap, likelyccounting for the observed discrepancy between thecoring systems.Table 4 examines the clinical usefulness of the rejec-

ion grading systems with regard to detection of acuteejection in the treatment group. In 3 of the 10 animalsNos. 5, 6, and 9), the first visual and histologic signs ofejection appeared simultaneously. In two pigs (Nos. 1nd 3), visual signs of rejection preceded histologiciagnosis by 3 and 5 days, respectively, and rejectionas of mild severity (Grade 1) when it did appear oniopsy. In 5 animals, a histologic picture of mild Graderejection appeared on biopsy before any noticeable

hanges in the skin surface. In 3 of these cases (Nos.0, 7, and 4), histologic rejection as defined by ourriteria was present on Day 0 with visual changes notvident until Days 2, 4, and 7, respectively. However,y the time rejection was first noted to be present byisual criteria, the rejection process had not progressedistologically in 2 of the 3 animals (still Grade 1) andctually reversed in 1 (Grade 0). In the remaining 2ases (Nos. 2 and 8), rejection was already of moderateeverity (Grade 2) at the time when it first becamevident by visual criteria (on Days 10 and 68, respec-ively), and was potentially diagnosable when it wastill Grade 1 by earlier biopsy. Pig No. 2 did ultimatelyose the graft from rejection on Day 29, with all biop-ies from Day 2 on demonstrating at least Grade 1ejection. Interestingly, pig No. 8 demonstrated an in-onsistent picture of Grade 1 alternating with Grade 0ejection on biopsy specimens from Days 7 to 61 post-peratively, with only specimens from Days 68 to 90onsistently showing Grade 2 rejection.

DISCUSSION

The skin is felt to be more susceptible to rejectionhan other extremity tissues and visceral organs be-

2

Skin Rejection of a CTA Flap

olliculitisDermal

inflammationEpidermal

degeneration

ne None Nonene/mild Mild None/mildld/moderate Mild/moderate Mild

b

H: VOL. 85, NO. 1, JULY 1999

t

LE

r

F

NoNoMi

3 4 Moderate diffuse Moderate Moderate Moderate

ere/necrosis Severe/necrosis Severe/necrosisccdltbothetruceoqtt

sual Grade 0 (A, n 5 54); Grade 1 (B, n 5 23); Grade 2 (C, n 5 21); Grade3

ause of its special intrinsic immunologic features, in-luding high concentrations of Langerhans’ and otherendritic antigen-presenting cells, as well as extracel-ular matrix proteins that position T-cells for activa-ion and effector functions [16]. Indeed, the skin haseen observed to be the first tissue component to dem-nstrate visual and histologic changes of acute rejec-ion in both small- and large-animal CTA models, andas been used as the parameter for rejection of thentire transplant [1, 17–19]. Unfortunately, a multi-ude of different visual criteria for defining the time ofejection of the skin component of a CTA have beentilized in previous studies, and there appears to be noonsensus or attempt at standardization. For example,ndpoints used by other investigators to define the day

FIG. 2. Histological grade of rejection of biopsy specimens with vi(D, n 5 6); and Grade 4 (E, n 5 11).

ZDICHAVSKY ET A

f rejection of rat hind limb transplants, the most fre-uently studied CTA model, have included: (1) whenhe skin surface could be wiped away with the gentlestouch [4]; (2) when the entire skin surface was hard

TABLE 3

Result Summary for Group II Pigs ReceivingCsA/MMF/Prednisone Therapy (n 5 10)

Pig No. POD No.aCause of

death

Skin rejection grade

Visual Histologic

1 25 Rejection 4 42 29 Rejection 4 43 19 Pneumonia 0 04 30 Anesthesia 0 15 .90 0 06 .90 0 07 .90 0 1

5L.: SKIN REJECTION

8 .90 2 29 .90 3 4

10 .90 2 2

a POD, postoperative day.

a[[bmma

flsdcioHsnbbwidjOlplttrbiaa

fsfisschtotbrw

te(attflGwGeGgGri(

.

6

nd escharified with hair loss [4]; (3) erythema for 24 h5, 7]; (4) the onset of edema, erythema and/or hair loss6, 20]; (5) the first sign beyond erythema and edemaut before progressing toward epidermolysis, desqua-mation, or eschar formation [3, 21]; (6) 80% involve-ent of the limb by progressive dermal lesions [22];

nd (7) a 5°F decline in limb temperature [23].In contrast to the widespread use of visual criteria,

ew investigators have utilized or developed a histo-ogic grading system for evaluating the severity of CTAkin rejection. Along these lines, Daniel et al. [1] basediagnosis of rejection in primate hand and neurovas-ular free flap transplants solely on clinical signs, sincet was difficult to distinguish infection from rejectionn punch biopsies. Benhaim et al. [18] and van denelder et al. [19] adopted a histopathologic grading

ystem used by Saurat et al. [24] for grading the cuta-eous manifestations of graft-versus-host disease afterone marrow transplantation for evaluation of skiniopsies from rat hind limb allograft recipients treatedith MMF. Fritz et al. [17] based their histologic grad-

ng scheme for assessing rejection of CsA-treated ro-ent limb transplants on early reports describing re-ection in rabbit skin and canine heart muscle [25, 26].nly Buttemeyer et al. [3] developed a de novo patho-

ogic grading system for scoring rejection of CTA com-onents based on their own histologic examination of aarge number of biopsy specimens obtained from limbransplants in rats immunosuppressed with CsA andacrolimus. This group identified three grades of skinejection, with focal mononuclear cell infiltration andasal cell vacuolation (Grade I) proceeding to a mixed

TAB

Clinical Utility of Visual and Histologic Gra

Pig No.

First visual rejectionHis

gPOD No.a Grade

1 4 12 10 23 2 14 7 25b 4 26b 4 17 4 18 68 29b 2 1

10 2 2

a POD, postoperative day.b Visual and histologic grades indicated rejection on the same day

JOURNAL OF SURGICAL RESEA

nfiltrate with suprabasal bulla formation (Grade II),nd finally, to the development of edema, vasculitis,nd necrosis (Grade III).To date, there has been no attempt to (1) establish a

1rov

ormal grading system for visual assessment of theeverity of skin rejection in CTAs; (2) correlate visualndings with histologic examination of skin biopsypecimens; and (3) define both visual and pathologiccoring systems for skin rejection in a large-animal,linically-relevant CTA model. Based on the visual andistologic progression of skin rejection noted in un-reated swine undergoing creation of a radial forearmsteomyocutaneous flap containing all of the tissues ofhe limb except cartilage, we defined and correlatedoth visual and histologic scoring systems for skinejection (Fig. 1) and applied them to recipients treatedith a CsA/MMF/prednisone regimen.First, the entire group of 115 biopsy specimens ob-

ained from 6 control and 10 treated pigs was consid-red together and evaluated as independent sampleswithout regard to the clinical course of the animals) tossess the predictive value of an assigned visual gradeo the actual histologic grade, which was consideredhe “gold standard.” The two grades matched in 61% ofaps with visual Grade 0, 52% of flaps with visualrade 1, 48% of flaps with visual Grade 2, 17% of flapsith visual Grade 3, and 91% of flaps with visualrade 4, for an overall concurrence rate of 57%. How-ver, biopsy specimens from 93% of grafts with visualrade 0, 96% of grafts with visual Grade 1, 95% ofrafts visual with Grade 2, 83% of grafts with visualrade 3, and 91% of grafts with visual Grade 4 were

ead to be within 61 histologic score. When visualnspection indicated acute rejection was presentGrade 1), it was indeed present histologically (Grade

4

ng Systems in Diagnosis of Skin Rejection

gice

First histologic rejectionVisualgradePOD No.a Grade

7 1 12 1 07 1 10 1 04 1 24 2 10 1 07 1 02 2 10 1 0

H: VOL. 85, NO. 1, JULY 1999

LE

di

tolorad

0201120221

RC

) 92% of the time. When visual assessment indicatedejection was not present (Grade 0), it was present byur histologic criteria 39% of the time. Importantly, theast majority (81%) of missed rejection specimens were

ma

ciwvwcdmeaw2wsbDjtwvwb

1tsorTpttiow

pbdmitViec

t

1

1

1

1

1

1

L.:

ild (histologic Grade 1) in severity, 14% were moder-te (Grade 2), and only 5% moderate-to-severe (Grade 3).We next determined the clinical significance of the

orrelation between the two scoring systems by exam-ning the course of the 10 pigs in the treatment groupith specific regard to initial detection of rejection bothisually and histologically. Had biopsy been performedhen prompted by visual changes alone and not ac-

ording to protocol, acute rejection would have beeniagnosed histologically at Grade 1 (mild) in five ani-als, and Grade 2 (moderate) in five animals, with all

pisodes still very likely reversible with initiation ofntirejection therapy. Moreover, in two of the five pigshich would have been initially diagnosed with Graderejection (on Days 2 and 4 postoperatively), rejectionas not at all apparent on earlier (Day 0 or 2) biopsy

pecimens. Furthermore, a third pig which would haveeen initially picked up with Grade 2 rejection late onay 68 did not have a consistent picture of acute re-

ection on previous biopsies. Therefore, it would appearhat clinical utilization of our visual scoring systemith Grade 1 as an indication for biopsy would result inirtually all initial rejection episodes being detectedhen still histologically Grade 1 or immediately onecoming Grade 2.Three of the 16 grafts demonstrated histologic Graderejection on Day 0, although it is difficult to attribute

his to a nonspecific postoperative inflammatory re-ponse because it only occurred in a small percentagef cases. Two of these grafts did not show evidence ofejection by visual and histological criteria on Day 2.hese initial mild pathologic findings would be moreroperly assessed by including an autotransplant con-rol group. Along these lines, Press et al. [9] noted thathe histological appearance of rat limb allografts isnitially identical to that in autografts, which also dem-nstrate edema and an initial inflammatory infiltratehich clears.In conclusion, visual assessment carried an 8% false

ositive and 39% false negative rate with regard toiopsy-proven rejection if samples were evaluated in-ependently. However, 81% of missed rejection speci-ens were histologic Grade 1. Biopsy, when visually

ndicated, would detect all rejection episodes when his-ologically Grade 1 or 2 and still potentially reversible.isual scoring of CTA skin serves as a useful tool for

nitially detecting rejection, but repeated histologicvaluation is necessary for monitoring the subsequentourse of the graft.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

ZDICHAVSKY ET A

The authors thank Ms. Sharon Lear for excellent technical assis-ance in processing the skin samples.

1

1

REFERENCES

1. Daniel, R. K., Egerszegi, E. P., Samulack, D. D., Skanes, S. E.,Dykes, R. W., and Rennie, W. R. J. Tissue transplants in pri-mates for upper extremity reconstruction: A preliminary report.J. Hand Surg. 11A: 1, 1986.

2. Stark, G. B., Swartz, W. M., Narayanan, K., and Møller, A. R.Hand transplantation in baboons. Transplant. Proc. 19: 3968,1987.

3. Buttemeyer, R., Jones, N. F., Min, Z., and Rao, U. Rejection ofthe component tissues of limb allografts in rats immunosup-pressed with FK-506 and cyclosporine. Plast. Reconst. Surg. 97:139, 1996.

4. Arai, K., Hotokebuchi, T., Miyahara, H., Arita, C., Mohtai, M.,Sugioka, Y., and Kaibara, N. Prolonged limb allograft survivalwith short-term treatment with FK-506 in rats. Transplant.Proc. 21: 3191, 1989.

5. Maramatsu, K., Doi, K., Shigetomi, M., Kido, K., and Kawai, S.A new immunosuppressant, FTY720, prolongs limb allograftsurvival in rats. Ann. Plast. Surg. 40: 160, 1998.

6. Fealy, M. J., Umansky, W. S., Bickel, K. D., Nino, J. J., Morris,R. E., and Press, B. H. Efficacy of rapamycin and FK 506 inprolonging rat hind limb allograft survival. Ann. Surg. 219: 88,1994.

7. Maramatsu, K., Doi, K., Akino, T., Shigetomi, M., and Kawai, S.Longer survival of rat limb allograft. Acts. Orthop. Scand. 68:581, 1997.

8. Lee, W. P. A., Yaremchuk, M. J., Pan, Y-C., Randolph, M. A.,Tan, C. M., and Weiland, A. J. Relative antigenicity of compo-nents of a vascularized limb allograft. Plast. Reconst. Surg. 87:401, 1991.

9. Press, B. H. J., Sibley, R. K., and Shons, A. R. Early histopatho-logic changes in experimentally replanted extremities. J. HandSurg. 8: 549, 1983.

0. Billingham, M. E., Cary, N. R. B., Hammond, M. E., Kemnitz,J., Marboe, C., McCallister, H. A., Snover, D. C., Winters,G. L., and Zerbe, A. A working formulation for the standard-ization of nomenclature in the diagnosis of heart and lungrejection: Heart rejection study group. J. Heart Transplant.9: 587, 1990.

1. Rose, A. G., and Cooper, D. K. C. A histopathologic gradingsystem of hyperacute (humoral, antibody-mediated) cardiacxenograft and allograft rejection. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 15:807, 1996.

2. Sobrado, L., Pollak, R., Robichaux, W. H., Martin, P. C., Sulli-van, K. A., and Swartz, W. M. The survival and nature of theimmune response to soft-tissue and composite-tissue allograftsin rats treated with low-dose cyclosporine. Transplantation 50:381, 1990.

3. Press, B. H. J., Libley, R. K., and Shons, A. R. Limb allotrans-plantation in the rat: Extended survival and return of nervefunction with continuous cyclosporine/prednisone therapy.Ann. Plast. Surg. 16: 313, 1986.

4. Lipson, R. A., Kawano, H., Halloran, P. F., McKee, N. H.,Pritzker, K. P. H., and Langer, F. Vascularized limb transplan-tation in the rat. Transplantation 35: 293, 1983.

5. Ustuner, E. T., Zdichavsky, M., Ren, X., Edelstein, J., Maldo-nado, C., Ray, M., Jevans, A. W., Breidenbach, W. C., Gruber,S. A., Barker, J. H., and Jones, J. W. Long-term compositetissue allograft survival in a porcine model with cyclosporineA/mycophenolate mofetil therapy. Transplantation 1998, in

7SKIN REJECTION

press.6. Steinmuller, D. The enigma of skin allograft rejection. Trans-

plant. Rev. 12: 42, 1998.7. Fritz, W. D., Swartz, W. M., Rose, S., Futrell, J. W., and Klein,

1

1

2

2

2

2

2

2

8 RC

E. Limb allografts in rats immunosuppressed with cyclosporinA. Ann. Surg. 199: 211, 1984.

8. Benhaim, P., Anthony, J. P., Lin, L. Y-T., McCalmont, T. H.,and Mathes, M. J. A long-term study of allogeneic rat hindlimbtransplants immunosuppressed with RS-61443. Transplanta-tion 58: 911, 1993.

9. van den Helder, T. B. M., Benhaim, P., Anthony, J. P., Mc-Calmont, T. H., and Mathes, S. J. Efficacy of RS-61443 inreversing acute rejection in a rat model of hindlimb allotrans-plantation. Transplantation 57: 427, 1994.

0. Kuroki, H., Bean, M. A., Ikuta, Y., Aklyama, M., and Burgess,

JOURNAL OF SURGICAL RESEA

E. M. Effect of FK 506 and donor-specific blood transfusion onthe rat composite tissue limb allograft and the mechanism oflong-term graft survival. Transplant. Proc. 25: 658, 1993.

1. Min, Z., and Jones, N. F. Limb transplantation in rats: immu-nosuppression with FK-506. J. Hand Surg. 20A: 77, 1995.

2

2. Doi, K. Homotransplantation of limbs in rats. Plast. Reconst.Surg. 6: 613, 1979.

3. Black, K. S., Hewitt, C. W., Fraser, S. A., Howard, E. B.,Martin, D. C., Achauer, B. M., and Furnas, D. W. Compositetissue (limb) allografts in rats. Transplantation 39: 365,1985.

4. Saurat, J. H., Gluckman, E., Bussel, A., Didierjean, L., andPuissant, A. The lichen planus-like eruption after bone marrowtransplantation. Br. J. Dermatatol. 92: 675, 1975.

5. Medawer, P. B. A second study of the behaviour and fate of skin

H: VOL. 85, NO. 1, JULY 1999

homografts in rabbits. J. Anat. 157, 1945.

6. Billingham, M. E., and Caves, P. The diagnosis of canine ortho-topic cardiac allograft rejection by transvenous endomyocardialbiopsy. Transplant. Proc. 5: 741, 1973.