Satish Kumar to Keynote - Northeast Organic Farming ...

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of Satish Kumar to Keynote - Northeast Organic Farming ...

Winter, 2004-05 Vol. 2, No. 63 Publication of the Northeast Organic Farming Association ISSN 1077-2294

Inside This IssueFeatures

Praise for NOFA Manuals 3Local News and Events 42-434th Annual Organic Land Care Course 43

Supplement onOrganic Meat

Food From Thought 9Sheep in the Northeast 10Mad Cow in the USA 12Organic Meat at Woodbridge Farm 14Automating chicken Coop Security 18Organic Pork Production 19Industrial vs. Organic Livestock 23Selling Meat and Poultry 27Standard vs. Industrial Turkey Breeds 28Raising Grass-fed Meat 30Farm Animal Production Standards 32Grass Fed at Rocky Top Acres 34Irradiated Meat for Lunch? 38

DepartmentsEditorial 2NOFA Exchange 4News Notes 6Book Reviews 44NOFA Contact People 46Calendar 47NOFA Membership Information 47

For the last several years, the NOFA SummerConference has been able to send people to theConference free of charge, thanks to fundingfrom the Pond Foundation based in Santa Fe,New Mexico. Over three years, the Pond Foun-dation donated $7,200 with which conferenceregistrar Dennis Cronin awarded scholarships toa specific population, as per Pond Foundation‚srequirements. These were people of color andurban youth.

This year, the Pond Foundation has alerted usthat they can no longer help support the NOFASummer Conference financially, although theircontributions have helped close to 150 peopleto broaden their horizons and their life experi-ences by attending the Summer Conference. Ithas also broadened NOFA’s reach to include

Scholarships more young people, minorities and urbandwellers. This deepening of our membershipbase is a plus for all.

The only way that the NOFA Summer Confer-ence can continue to provide scholarships tothis special population and to other people inneed who want to attend the conference isthrough your donations. We would love to self-fund this scholarship program but we need yourhelp.

Donations can be sent to: NOFA SummerConference Scholarship Fund, c/o JulieRawson, 411 Sheldon Road, Barre, MA 01005.Donations may also be made online atwww.nofa.org - click on the Summer Confer-ence link and follow the instructions.

Thank you for your support! Your contributionsare tax deductible

by Kathleen Litchfield, Summer ConferencePublicity Coordinator

The results are in, but it goes without sayingthat the 2004 summer conference was biggerand better than ever. A grand total of 1,447people attended August’s grand event and allenjoyed a diverse array of informative work-shops for adults, teens and children, deliciousorganic meals, music and dancing, the enter-taining festivities of the Saturday fair and somuch more.

Following the stellar 2004 lineup of EliotColeman, Dr. Vandana Shiva, Ralph Nader andTexas Congressman Ron Paul in the slots ofpre-conference presenter, keynote speaker anddebaters, the delectable soup of the four-day31st Annual NOFA Summer Conference isalready stewing.

The Northeast Organic Farming Associationwill hold its 31st Annual Summer Conferencefrom August 11-14, 2005 at Hampshire College

Save August 11-14, 2005 for 31st Annual NOFA Summer Conference

in Amherst, Massachusetts. For the last threedecades, the workshops at this conference haveinspired and brought together new and experi-enced farmers, gardeners, activists, landowners,homesteaders, home-schoolers, and all sorts ofinteresting folks from the Northeast and wellbeyond. Many people plan their summersaround the conference dates, so join them andmark your 2005 calendars now!

The 31st Annual NOFA Summer Conferencepromises to instill in us even more deeply thesense that growing healthy, nutritious food thathelps sustain our community, our environmentand our world as well as our children andourselves, is of utmost importance.

In the ever-changing landscape of farming andhomesteading, organic standards, the politicalenvironment, alternative energy, nutrition andhealth care, civil rights and all of the fibers thatcomprise our day-to-day web of life, it is nice toknow we can count on NOFA’s summer confer-ence for stimulating discussions and workshops

on both intellectual and highly practical topics,while we congregate with a diverse populationof all ages.

During our October summer conference meet-ing, committee members reviewed evaluationsfrom the 2004 event, in order to most effec-tively and proactively plan for yet anotherstellar conference. While munching diverse,homemade potluck fare in a cozy living room,we were delighted to read the following, andadded these fabulous testimonials to the NOFAwebsite, at www.nofa.org.

“This was a fantastic weekend! Verystress-free because everything was meticulouslyorganized.”

“It’s a daunting task to plan and executea conference the size of NOFA and I trulyappreciate all of your efforts. The folks I’ve metand the knowledge I’ve gained have made me abetter farmer and hopefully a better person.Thank you all for a job very well done.”And, “This was our first conference. We reallyhadn’t a clue as to what to expect but weregreatly pleased with every aspect of the confer-ence. My teens have already decided that thiswill be on our agenda next year. When teensand adults are on the same wavelength thatsomething is fun, has good food, wonderfulpeople, is informative, then you have a magicalrecipe for something beyond success. Thankyou!”

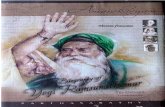

Satish Kumar to Keynote

(continued on page 41)

T h e N a t u r a l F a r m e r Winter , 2 0 0 4 - 0 52

Advertisements not only bring in TNF revenue, whichmeans less must come from membership dues, they alsomake a paper interesting and helpful to those looking forspecific goods or services. We carry 2 kinds of ads:

The NOFA Exchange - this is a free bulletin boardservice for NOFA members and TNF subscribers. Sendin up to 100 words (business or personal) and we’ll printit free in the next issue. Include a price (if selling) and anaddress or phone number so readers can contact youdirectly. If you’re not a NOFA member, you can still sendin an ad - just send $5 along too! Send NOFA Exchangeads directly to The Natural Farmer, 411 Sheldon Rd.,Barre, MA 01005 or (preferably) E-mail [email protected].

Display Ads - this is for those offering products orservices on a regular basis! You can get real attentionwith display ads. Send camera ready copy to DanRosenberg, PO Box 40, Montague, MA 01351 (413) 863-9063 and enclose a check for the appropriate size. Thesizes and rates are: Full page (15" tall by 10" wide) $300 Half page (7 1/2" tall by 10" wide) $155 One-third page (7 1/2" tall by 6 1/2" wide) $105 One-quarter page (7 1/2" tall by 4 7/8" wide) $80 One-sixth page (7 1/2" tall by 3 1/8" wide), or

(3 3/4" tall by 6 1/2" wide) $55 Business card size (1 1/2" tall by 3 1/8" wide) $15

Note: These prices are for camera ready copy. If youwant any changes we will be glad to make them - or totypeset a display ad for you - for $10 extra. Just send usthe text, any graphics, and a sketch of how you want it tolook. Include a check for the space charge plus $10.

Advertise in or Sponsor The Natural FarmerFrequency discounts: if you buy space in several issuesyou can qualify for substantial discounts off these rates.Pay for two consecutive issues and get 10% off each, payfor 3 and get 20% off, or pay for 4 and get 25% off. Anad in the NOFA Summer Conference Program Bookcounts as a TNF ad for purposes of this discount.

Deadlines: We need your ad copy one month before thepublication date of each issue. The deadlines are:

January 31 for the Spring issue (mails Mar. 1)April 30 for the Summer issue (mails Jun. 1)July 31 for the Fall issue (mails Sep. 1)October 31 for the Winter issue (mails Dec. 1)

Disclaimer: Advertisers are helping support the paper soplease support them. We cannot investigate the claims ofadvertisers, of course, so please exercise due cautionwhen considering any product or service. If you learn ofany misrepresentation in one of our ads please inform usand we will take appropriate action. We don’t want adsthat mislead.

Sponsorships: Individuals or organizations wishing tosponsor The Natural Farmer may do so with a payment of$200 for one year (4 issues). In return, we will thank thesponsor in a special area of page 3 of each issue, andfeature the sponsor’s logo or other small insignia.

Contact for Display Ads or Sponsors: Send display adsor sponsorships with payment to our advertising managerDan Rosenberg, PO Box 40, Montague, MA 01351. Ifyou have questions, or want to reserve space, contact Danat (413) 863-9063 or [email protected].

The Natural Farmer is the newspaper of the NortheastOrganic Farming Association (NOFA). Regular membersreceive a subscription as part of their dues, and othersmay subscribe for $10 (in the US or $18 outside the US).It is published four times a year at 411 Sheldon Rd.,Barre, MA 01005. The editors are Jack Kittredge andJulie Rawson, but most of the material is either written bymembers or summarized by us from information peoplesend us.

Upcoming Issue Topics - We plan a year in advance sothat folks who want to write on a topic can have a lot oflead time. The next 3 issues will be:

Winter 2004-05 Organic MeatSpring 2005 Youth and AgricultureSummer 2005 CucurbitsFall 2005 Alternative On-Farm Energy

Moving or missed an issue? The Natural Farmer will notbe forwarded by the post office, so you need to make sureyour address is up-to-date if you move. You get yoursubscription to this paper in one of two ways. Directsubscribers who send us $10 are put on our database here.These folks should send address changes to us. Most ofyou, however, get this paper as a NOFA member benefitfor paying your chapter dues. Each quarter every NOFAchapter sends us address labels for their paid members,which we use to mail out the issue. If you moved ordidn’t get the paper, your beef is with your state chapter,not us. Every issue we print an updated list of “NOFAContact People” on the last page, for a handy reference toall the chapter names and addresses.

As a membership paper, we count on you for articles, artand graphics, news and interviews, photos on rural ororganic themes, ads, letters, etc. Almost everybody has aspecial talent or knows someone who does. If you can’twrite, find someone who can to interview you. We’d liketo keep the paper lively and interesting to members, andwe need your help to do it.

We appreciate a submission in any form, but are lesslikely to make mistakes with something typed than hand-written. To be a real gem, send it via electronic mail([email protected]) or enclose a computer disk (MacIntoshor PC in Microsoft Word ideally.) Also, any graphics,photos, charts, etc. you can enclose will almost certainlymake your submission more readable and informative. Ifyou have any ideas or questions, one of us is usually nearthe phone - (978) 355-2853, fax: (978) 355-4046. TheNOFA Interstate Council website is www.nofa.org.

ISSN 1077-2294copyright 2004,

Northeast Organic Farming Association

The Natural FarmerNeeds You!

by Jack Kittredge

Julie and I have always felt that raising our ownfood – including meat — was important. Shortlyafter we met, in Dorchester, we began keepingrabbits. The kids, as they came along, had to shareour tenement’s miniscule back yard with a consider-able vegetable garden and three rabbit hutches. Themanure went on the garden and when the youngrabbits were old enough we all killed and cleanedthem for the table. Since moving to our farm inBarre, we have raised lots of animals: chickens,turkeys, ducks, geese, sheep, pigs and cattle. Evenfish in our pond, come to think of it.

Neither of us has much trouble with the ethics ofeating meat. I guess we take a “what goes aroundcomes around” point of view. We try to give theanimals a good life, respecting their needs andwishes. When their time comes we do it as pain-lessly as possible.

What seems more difficult to justify, to my mind, ishaving no relationship at all to the meat you eat –not raising it, not even knowing who raised it orhow it was raised. That distance must necessarilyobjectify the relationship, taking the connections ofpersonality or spirit away. What is left is a consumerand a commodity.

Making food into a commodity is what factoryfarming is all about. Monocropping, standardiza-tion, mechanization, confinement housing, use ofchemicals and drugs – all these are ways of strip-ping away natural complexities and replacing themwith simplification and control. The organic move-ment has rejected that approach and tried to workwith nature instead of controlling it.

Such a management approach may be most evidentwhen it comes to animal care. Rare and heritagebreeds, rotational grazing, chicken tractors andrange houses, nursing sick animals with personalcare and attention – all these are common featuresof organic animal husbandry and would be anath-ema to “rational” factory livestock operations.

It has always seemed thoughtless to me to presumethat because big livestock operations are destructiveof resources, small ones must be as well. We several

times had apprentices here who adopted such anideology without ever stopping to think. A feedlotthat trucks in grain and water from distant sources,stockpiles manure lest it pollute, and routinelyadministers parasiticides and antibiotics to keepdisease manageable is not the only model. There arehumane and environmentally sound ways to raisemeat. A small New England farm can make verygood ruminant pasture of grassy hillsides whichshould not be plowed, can thrive using the manureso naturally produced in the process, and is blessedwith healthy dairy products and an annual gift of acalf or lamb each spring.

Throughout the Northeast there are livestock farmswhere the animals are raised with love, care and tothe highest organic standards. Consumers who wishto become a little more connected with their meatcan find such farms easily through their local NOFAchapter, CSA or farmers market. Here in CentralMassachusetts we have the Heifer Project farm inRutland and the Natick Community Organic Farm.Both are happy to have volunteers help with farmchores and involve themselves in every aspect ofanimal care. Many private farms are also willing toaccept regular volunteer help from customers.

We hope that this issue of The Natural Farmermakes it clear how organic animal managementdiffers from conventional. We feature farmers, aswell as animal and consumer advocates. Theirpassion and love for the creatures with whom theywork is evident, and their practical strategies forsustaining small-scale livestock production in thisage of commodities are invaluable.

On Raising and Eating Organic Meat

T h e N a t u r a l F a r m e rWinter , 2 0 0 4 - 0 5 3

by Jonathan von Ranson

In the first review the NOFA Organic Principles andPractices Handbooks Series received, Greg and PatWilliams of the monthly newsletter HortIdeasoffered NOFA highest compliments:“We have nothing but praise for NOFA’s wonderfulidea of making available compact and inexpensiveguides to organic techniques, written by experiencedpractitioners. We predict that these books will gain‘classic’ status—and we hope they will be updatedperiodically to reflect the latest developments!”The handbooks also sold well, retail and wholesale,at the SARE national conference held in October inBurlington, Vt.

Work on the series is in the final stages. All tenvolumes are scheduled to be printed by earlyFebruary, 2005. The authors, the artist and I haveput great effort into this project; many of the re-viewers likewise! Now it moves into promotion andsales time for the new, expert, easy-to-read manuals.All NOFA chapters and other organic associations inthe Northeast have been invited to purchase thehandbooks for resale, individually or as a series.They can do so by contacting Elaine Peterson [email protected] or calling her at 978 355-2853.Promotional materials have also gone out to a fewseed catalogues.

As always, state chapters can sell the books atconferences and events. They also have the opportu-nity for online credit card sales—of the books andother items—as CT NOFA and NOFA/Mass arealready doing. A new manuals page on the InterstateCouncil website describes the books (http://www.nofa.org/pubs/index.php) and gives buyers achoice of which participating state’s web page toorder through. Members of chapters not yet tied inmay want to quickly contact their chapter officialsabout joining the on-line ordering system. (Inquiriesfrom chapters go to Paul Kittredge [email protected]).

Individuals interested in purchasing them can go towww.nofa.org or write Elaine Peterson, Dep’t IC,411 Sheldon Rd., Barre MA 01005. All titles are$7.95 plus $2 shipping and handling per book.

The Latest Entry

Crop Rotation and Cover Cropping is the latest

Reviewers Praise NOFA Handbooks for Quality

book printed. It joins Vegetable Crop Health, byBrian Caldwell, Whole Farm Planning, by ElizabethHenderson and Karl North, and Compost,Vermicompost and Compost Tea, by GraceGershuny, all SARE-funded handbooks. WeedManagement and Soil Fertility Management, bothby Steve Gilman, were published in a similar formatin 2000 and 2002 by NOFA/Mass and are being soldas part of the series.

In Crop Rotation and Cover Cropping, author SethKroek, an up-and-coming Maine farmer, describesthe benefits of planning crop rotations with covercrops: they help control insect pests and disease,improve soil fertility and health, and controlweeds…and free-up the farmer’s time and attentionduring the growing season. Kroek clearly lays outthe principles of crop rotation and takes some of theintimidation factor out by grouping crops accordingto various relevant categories in handy lists. He addsthat the rules are often bent in real life—a service in

this sometimes confusing and intimidating aspect offarming. The manual offers three sample rotationplans with cover crops for a fictional 12-acre farm,simple to complex and detailed (“the Cadillac”),that include a semi-perennial crop: strawberries.Seth has worked and managed organic farms in theNortheast and California for the past eight years. Henow operates his own farm, Crystal Spring Commu-nity Farm in Brunswick, ME with his wife, Maura.Handbooks in the SARE-assisted series to bepublished in the next month or two are Marketingand Community Relations, by Rebecca Bosch,Humane and Healthy Production of Eggs andPoultry, by Karma Glos, Organic Seed Productionand Saving, by Bryan Connolly, and Making Milkand Dairy Products Organically, by Sarah Flack.Besides the authors and myself, the people mostdeeply involved in this project have been artistJocelyn Langer and NOFA President Bill Duesing,who is serving double duty as reviewer and sharp-eyed proofreader.

photo by Bill Duesing

NOFA Manuals Editor Jonathan von Ranson accepts compliments from Cornell Professorand NEON project director Anu Rangarajan (holding copy), at a recent SARE conference.

Please help us thank theseFriends of Organic Farmingfor their generous support!

T h e N a t u r a l F a r m e r Winter , 2 0 0 4 - 0 54

Blow YourOwn Horn!

New intentional community in Central Mass:LandARC (Land Activists Reclaiming Community)is a group of families and individuals planning topurchase land in central Massachusetts. Our aim isto live together with 10-15 families in private homesand to share a common house where commonmeals, meetings, and projects happen. We arecommitted to farming, alternative education, andactivism. Seeking new members. 508-579-9093 orwww.landarcvillege.org

Farm Internship - The Natick Community OrganicFarm located in Natick, Massachusetts is lookingfor a one-year intern. Housing (one room studiowith shared kitchen and bath facilities) is offered inexchange for 10 hours of farm-related work and 5hours of office work. Additional teaching opportuni-ties are available for pay. For further informationsee www.natickfarm.org. If interested please contact508-655-2204 or email [email protected].

Job Opportunity: Managing Director of RegionalFarm & Food Project, Albany-Troy, New York. Willbe responsible for creating and managing thebusiness infrastructure essential to support theorganization’s mission. Responsibilities includemanaging office operations, financial administra-tion, database administration, marketing and com-munications, membership programs and specialevents. This fulltime position requires excellentsmall business management skills, a high degree ofcomputer literacy, event management experience,and knowledge of fundraising and grant writing.The Managing Director will report to the Board ofDirectors and attend monthly Board Meetings.Contact RFFP Board Co-Chair Annie Brody at(518) 781-0446 or email her [email protected]

NOFAExchange

2005 Position Available: Assistant Farm Managerfor two acre certified organic farm which serves as atherapeutic and vocational training site for homelessmen and women. Assist farm manager in all aspectsof seedling and crop production, local sales, andsupervision of client workers. 25 weeks position,from mid-April through mid-October 2004. Previ-ous experience in agriculture needed and workingwith special needs populations preferred. $500 perweek salary. Valid drivers license. Send resume andcover letter to: Jean-Claude Bourrut, Long IslandShelter, P.O. Box 158, Boston, MA 02122. 617-534-2526 x304. [email protected]

Angelic Organics, a Wisconsin community sup-ported organic vegetable farm (www.angelicorganics.com) 8 mi SE of Beloit, 12 mi N ofBelvidere, seeks a Soil and Machinery Managerwho will be responsible for tillage, fertility, spraying(with organic sprays), and machinery management.Must be highly qualified with at least 5 years offarming experience. Full time, year round positionstarts in April, 2005. $32,000 per year plus benefits.Three yr. commitment preferred. (Please - nounscheduled farm visits.) For job overview, reviewmaterials at www.homepage.mac.com/angelicorganics/job.html

The Northeast Organic Dairy Producers Alliance(NODPA) will be hiring a coordinator and admin-istrator this winter. Tasks will include some or allof the following: setting up and running a newoffice, database development, book keeping, eventorganizing, grant writing, supervising part timestaff, and maintaining regular phone and emailcorrespondence with organic dairy farmer represen-tatives, industry and service sector people. Pleasesend a resume and letter of interest to Enid atNOFA-VT, PO box 697 Richmond VT 05477 [email protected].

Organic Crops Production positions for 2005season May-October at Heifer International’sOverlook Farm in Rutland, MA. Seewww.heifer.org for details about Heifer. Overlook isa working farm and educational center that teachesabout hunger and poverty issues. Garden volunteersgrow on 3 acres, lead work groups and educationalprograms. Also small-scale aquaculture, crops fromaround the world, and horse power—come learnwith us! 50 hour week; stipend starts at $250/month, then increases by $50 every 3 months.Americorps credit usually available. $600 bonus for6-month stay! Housing/veggies provided. CallDave or Carolyn at (508) 886-2221, or [email protected]

Sustainable Ag/Education positions at HeiferInternational’s Overlook Farm in Rutland, MA: Seewww.heifer.org for details about Heifer. Live andwork on our farm for 1-12 months. Stipend starts at$250/month, increases by $50 every 3 months. Americorps credit usually available. Housing/somefood provided. Work 6 days a week with livestock,leading group tours and education sessions abouthunger/poverty, and special events. To inquire abouta volunteer position, call or email Sue Collette at(508) 886-2221, or [email protected].

Seeking Urban Farm and Community GardensCoordinator. Be part of growing the urban agricul-ture and environmental justice movement inWorcester, Massachusetts! This position drawsconcrete links between community empowermentand building a just food system. Work with 15community gardens, and manage the YouthGROWurban farm. The farm hosts an organic farmingprogram for teens. Applicants must have enthusiasmfor urban agriculture and working with youth,experience with organic agriculture, events organiz-ing, Spanish proficiency. Send resumes by Decem-ber 20 to Regional Environmental Council, PO Box255, Worcester, MA 01613, or email,[email protected]. Info (508) 799-9139 orvisit www.recworcester.org.

Certified Organic Laying Hens For Sale. 1 1/2years old. Silver Laced Wyandottes, Black Austral-orps, New Hampshire Reds. Experience the delightof fresh eggs. Egg-xactly what every home needs!Call The HERB FARMacy, Salisbury, MA978.834.7879 or email: [email protected].

Assistant Farm Manager – Holcomb Farm CSA,Granby, CT. 20-acre non-profit organic vegetablefarm. Exact responsibilities depend on interests andexperience, but could include field crew leader,tractor work and maintenance, CSA marketing andadministration, selling at a farmers market, andgreenhouse management. Two seasons of produc-tion vegetable farming required. Year round, $425/week, medical insurance, pension, housing. Alsoseeking Apprentices April – Nov, $350/week,housing.Contact Sam Hammer, (860) 653-5554,[email protected]. Pictures and info atwww.holcombfarmcsa.org.

Two hardy perennials, 22 and 23, looking forplace to overwinter. Like brassicas, we’re self-sufficient and highly productive guys, with fifteenyears combined experience in organic farming.Seeking place in Amherst/Pioneer Valley area to setroots during winter and possibly into spring. Idealgrowing conditions are a small farm, estate or grouphouse, where we would caretake/nitrogen-fix/live,in exchange for low rent. Also interested in paidwinter work, including greenhouse, animal andmaple syrup operations. References, pH require-ments, and crop rotation history available uponrequest. Please contact Chuk Kittredge [email protected] by Dec. 20th.

Project Associate, 50% time, for SustainableAgriculture Research and Education ProfessionalDevelopment Program (PDP), Northeast Region.Provide support for day-to-day functions of office atUniversity of Connecticut. Minimum: B.S. inagriculture, biology, related field, or equivalent, andknowledge of sustainable agriculture; willing totravel in Northeast; motivated, self-starter withability to follow through with attention to detail;excellent office skills; experienced with Word,Excel, FileMaker Pro, Power Point. Position fundedfor one year with expected continued funding.Available immediately. Competitive salary, univer-sity benefits. Contact Tom Morris, University ofConnecticut, 1376 Storrs Rd, Plant Science, Unit4067, Storrs, CT, 06269; [email protected]

T h e N a t u r a l F a r m e rWinter , 2 0 0 4 - 0 5 5Seeking community members. Currently 5 house-holds reside on this 275 acre land trust in SW NewHampshire. A community dedicated tosustainability, conservation, and making land andhousing accessible to low and moderate incomepeople who have interest in farming. FormerlyDavis Family Farm, we have grown to become ColdPond Community Farm. Activities at the farminclude: a cooperative CSA, apprenticeship andeducational opportunities, seasonal celebrations andcommunity dinners. There are a few available housesites left in our cluster arrangement and plenty offarm work to do. For more info: Barb or Steve 603-835-2403 [email protected]

Three Apprenticeships available on certifiedorganic vegetable farm in western CT for the 2005season, April 1 through October. Help plant,cultivate, harvest, and market produce through a 200share CSA and farmer’s markets. Opportunity tolearn agricultural and business skills you will needto run an organic farm. Compensation includes aprivate room in the apprentice house, farm produceand eggs, and $700 monthly stipend with opportu-nity for scheduled raises. To apply, send a letter andresume to Paul Bucciaglia, Fort Hill Farm, 18 FortHill Rd., New Milford, CT 06776. For more info,see www.forthillfarm.com, or call 860-350-3158.

Editor sought for Quarterly Journal BIODYNAM-ICS. Applicants should have basic understanding ofbiodynamic agriculture; experience with writing,editing, and marketing of print journals necessary;knowledge of print design, layout, and productionwork desirable. Position description atwww.biodynamics.com. Send letter of interest,résumé, and references to Biodynamic Farming andGardening Association, 25844 Butler Road, Junc-tion City OR 97448; [email protected].

I am in need of land to rent from Nov.-April. Ihave a 30' Camper, quiet generator, portable toilet,and access to shower facilities. I work f/t inNorthampton. Please consider...Thank you fortaking the time to read this. Pamelah (413) 585-0853, [email protected]

Wayne’s Organic Garden is offering certifiedorganic vegetable transplants for the 2005season, including tomatoes, peppers, eggplant,parsley, basil, onions, shallots and possible more.Pre-order only by January 31. Pick-up at farm midto late May. For list, prices, options, write or callWayne’s Organic Garden, PO Box 154, Oneco, CT06373, 860-564-7987.

Start your own diversified organic farm. 50 acres ofbeautiful low cost farm land for serious organicfarmers. Call Morze Tree Farm for details at 802-265-3512.

Red Fire Farm is now hiring apprentices for the2005 growing season. We seek highly motivatedpeople who want to spend one or more seasonsworking on a commercial certified organic veg-etable farm. We grow 15+acres of crops on 40 acresof prime farmland and sell produce via farmersmarkets, a CSA, farm stands and wholesale. Sti-pend is provided and housing is available. Pleasecontact Ryan at 413-467-7645 [email protected] for more information.

Internship opportunities and CSA shares avail-able for 2005 season. 85-family CSA, located in thepicturesque Monadnock region, in Sullivan, NHlooking for intern to work alongside farmer withplanting, weeding, harvesting, washing, packing,deliveries, and farmers market. We are in ourseventh year of diversified organic vegetableproduction and looking for hardworking enthusiasticindividuals, who want to get hands on experiencefarming. Working shares available as well. Formore information contact Tracie, 603-209-1851

T h e N a t u r a l F a r m e r Winter , 2 0 0 4 - 0 56

compiled by Jack Kittredge

GE NewsState of Massachusetts to Help FarmersPurchase GE Seed Corn.In a program recently announced by the Massachu-setts Department of Agricultural Resources, the statewill pay for 1/3 of the cost of genetically engineeredcorn seed for participating farmers. GE seed pur-chases are subsidized along with “best managementpractices” for air, soil and water conservation suchas water conserving irrigation equipment, contain-ment structures for fuel or hazardous chemicals, orenergy-efficient motors. Farmers applying for theGE aid will be asked to participate in a study todetermine how use of the GE corn seed impactstheir use of herbicides and pesticides (see belowstory on recent 9-year study on exactly this issue).Funding for this program (AEEP or AgriculturalEnvironmental Enhancement Program) comes froma state bond issue. source: http://mass.gov/agr andpersonal conversations with Mass DAR

GM Increasing Pesticide UseAs a former Executive Director of the Board onAgriculture of the US National Academy of Sciencefor seven years, Dr. Charles Benbrook represents anauthoritative voice on agricultural science. His latesttechnical report, drawing on 9 years of US Dept ofAgriculture data, confirms that the claim of GMproponents that the use of GM crops in the US hasled to a major reduction in pesticide use is quitesimply a lie. The data shows that overall GM cropshave led to an increase in pesticide use amounting tomillions of pounds per year. GE corn, soybeans andcotton have led to a 122 million pound increase inpesticide use since 1996. While Bt crops havereduced insecticide use by about 15.6 millionpounds over this period, herbicide tolerant (HT)crops have increased herbicide use 138 millionpounds. The increase in herbicide use on HT cropacres should come as no surprise. Weed scientistshave warned for about a decade that heavy relianceon HT crops would trigger changes in weed commu-nities and resistance, in turn forcing farmers toapply additional herbicides and/or increase herbi-cide rates of application. source: http://www.gmwatch.org/archive2.asp?arcid=4572

Hawaii Growing Hostile to Ag BiotechHawaii has been at the epicenter of the biotechonslaught in the US with more field tests takingplace there than in any other State. But as the costhas become clearer, in the wake of a scandal involv-ing massive GMO contamination of supposedlynon-GM papaya seeds at the University, Hawaii isturning into an increasingly hostile environment forthe industry. A recent report on an upcoming elec-tion in Hawaii noted that of the candidates from allpolitical parties, including Democratic and Republi-can, “Regarding the controversial geneticallymodified organisms (GMOs), no one supportedopen-air testing”. source: http://www.gmwatch.org/archive2.asp?arcid=4517, Acres, USA, November,2004

NewsNotes

Vermont: Labels Will Be Required On GMSeedsCompanies selling GM seeds in Vermont will haveto include a “plain English disclosure” on labels,says Agriculture Secretary Steve Kerr. He says thewords, “these seeds have been genetically engi-neered,” will have to appear on the label. Compa-nies will have to specify what traits have beenconferred through biotechnology. The law went intoeffect in October. Kerr decided on the specific rulesafter Monsanto Corporation and Dow AgroSciencesrefused to use the words “genetically engineered”on their seed labels next year. source: http://www.gmwatch.org/archive2.asp?arcid=4585

Mexican Farmers Protest Biotech Corn AtAg Research MeetingSome 300 Mexican environmentalists and farmactivists opposed to biotech crops demonstratedOctober 28 outside a Mexico City hotel to protest ameeting there of agricultural researchers fromaround the world. The demonstrators tossed tortillasand ears of corn painted with fluorescent colors andskulls at a line of riot police guarding the hotel, anddemanded the government halt the importation ofgenetically modified corn, which they claim hascontaminated local varieties of the crop. In March,the Commission for Environmental Cooperation, aNAFTA watchdog panel, found genetically engi-neered corn in Mexico despite the country’s six-year-old biotechnology ban. It said modified genesspread by imported U.S. biotech corn threaten todisplace or contaminate native varieties in Mexico,the birthplace of corn. Scientists say wild ancestralgenes of corn might one day be needed to helpcommercial crops overcome diseases or adverseconditions. source: http://www.soyatech.com/bluebook/news/viewarticle.ldml?a=20041029-5

Nobel Prize For Opponent of GMOs andPatents On LifeThis year’s Nobel Peace Prize is to be awarded toWangari Mathai, leader of the Green Belt Move-ment in Kenya. A biologist by training, Mathai is thefirst African woman to win the prize. She has woninternational recognition for her campaign fordemocracy, human rights and environmental conser-vation. She has also been among the African scien-tists who’ve drawn attention to the dangers ofgenetic engineering and of patents on life. source:http://www.gmwatch.org/archive2.asp?arcid=4501

Pharma Corn Scattered in Tornado?In May Iowa State University researcher Kan Wanggot permission to plant biopharm corn in a Coloradofield near Sterling, in Logan County. The cornproduces a protein which could be active in thehuman immune system. On June 9 a tornado hitSterling. Now organic growers are wondering ifsome of that seed has been scattered and could begrowing in their fields. Doug Wiley, president of theColorado Organic Producers Association, said:“Extreme weather events bring home the fact thatfood crops shouldn’t be used for these experiments.”source: Growing for Market, September, 2004

Brazilian Farmers Can Legally Grow GMSoy This Season - President Lula Da SilvaSigns Executive OrderBrazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva hassigned an executive order to allow the planting andtrade of genetically modified soy for the 2004-2005season only. The order allows farmers to plant theGM beans until December 31st, 2004. The resultingcrop may be sold until January 31st, 2006, but thatdeadline may be extended another 60 days. “Thepresident had no way out,” affirms Leon Klein ofKlein Commodities in Sao Paulo, “The way it looksnow, every state in Brazil is growing GM beans.About 20% of Brazil’s soy crop is expected to begenetically modified. I see it as something inevi-table that the farmers will grow GM.” Since thatwas the case, Lula da Silva had to find a solutionthat would allow Brazil to legally sell its crop. Sinceno option was immediately apparent from thelegislature, he reinstituted the temporary fix heinitiated last fall, legalizing GM soy only for theimmediate future. “It’s like making rain where itwas already wet,” says Mr. Klein. source: http://www.soyatech.com/bluebook/news/viewarticle.ldml?a=20041015-1

California: Marin County Passes GM CropBanMonths after Mendocino County voters passed thenation’s first ban on GM crops, voters in MarinCounty,California, have enacted a similar ban, with61 percent for and 39 percent against. Marin joinsTrinity as well as Mendocino counties in havingsimilar laws banning GMOs. Voters in Humboldt,San Luis Obispo and Butte counties rejected similarballot measures. The Humboldt County loss wasexpected because supporters dropped their cam-paign after complaints that the ballot languagecontained inaccurate scientific descriptions and alsocalled for the jailing of farmers growing GM crops.Butte GM-farm interests raised approximately$190,000 for the Vote No campaign - more thanthree times the money collected by the ban’s sup-porters. It was one of the most expensive ballotmeasures in recent county history. source: http://www.gmwatch.org/archive2.asp?arcid=4597

WHO Urges Further Research on GM FoodAfter Thai Papaya DebacleApparently the Thai Department of Agriculture’sKhon Kaen research station was selling geneticallyengineered papaya seeds in violation of nationallaw. The World Health Organization suggested inearly October that Thailand conduct further researchon genetically modified organisms (GMOs) so thatan early action plan can be implemented to copewith possible health risks posed by transgenic food.“At this point, we have no evidence to say that it isdangerous to consume food products that containGMOs, but at the same time we also don’t know itsnegative side. So, we have to say that we do notknow the adverse health effects of GM food,” WHOassistant director-general Kerstin Leitner said.source: Bangkok Post, October 13, 2004 and TheNon-GMO Source, September, 2004

Bush Suppresses GM Crop WarningsMonsanto and the US government have been tellingthe world that GM crops pose no contaminationthreat to natural indigenous species. But Greenpeacehas learned from a leaked report that NAFTAdisagrees and is recommending steps to avoid agenetic threat to natural maize in Mexico. Surprise,surprise: the Bush Administration is attempting tosuppress the report. The report, written by theCommission for Environmental Cooperation (CEC)of the North American Free Trade Agreement (US,Canada and Mexico) recommends that all GE maizeimports be labelled as such and that all US maizeentering Mexico should be milled upon entry, toprevent living seeds from being planted. The BushAdministration has intervened several times to delaythe publication of the report - completed threemonths ago - and there is still no official date for itspublication. source: http://www.gmwatch.org/archive2.asp?arcid=4547

Bentgrass: The Long Distance Travels of aBioengineered GeneA study shows that genes from a type of geneticallyengineered grass migrated much farther than anyonehad thought possible. The grass, a creepingbentgrass developed by Monsanto and Scotts, hasbeen modified genetically so it can tolerateRoundup herbicide, making it useful on golfcourses. But the bentgrass at issue could be difficultto control: it is a perennial that does not have to beplanted every year, its pollen is small and light andthus easily carried by the wind, and it has a dozen orso wild relatives that it can cross-pollinate. Environ-mental Protection Agency (EPA) scientists studyinggene dispersal of this grass found that some genesreached sentinel plants of the same species as far as13 miles away and wild relatives almost 9 milesaway. source: http://www.nytimes.com/2004/09/30/opinion/30thu3.html?ex=1097550717&ei=1&en=414d4c93cb609d54

T h e N a t u r a l F a r m e rWinter , 2 0 0 4 - 0 5 7

Other NewsDemand Soars for Organic Beef, Poultry,Fish and EggsThe Organic Trade Association (OTA) says thatdemand for organic beef is growing at 30% a yearover last year’s $10 million national total. OrganicValley’s subsidiary the Organic Meat Co. expectsits sales to triple this year, but could do far more ifthe supply were available. Safeway has introducedorganic beef in its California stores and reportsbooming business for the $4 to $6 a pound (retail)meat. The popularity of low carbohydrate diets aswell as the concern over mad cow are posited toexplain the strong demand. Also benefiting from thelow-carb interest are poultry, fish and eggs. Thecategory as a whole jumped 78% in sales in 2004.source: In Good Tilth, August 15, 2004 and OrganicBusiness News, July, 2004

US Farm Trade Surplus Lowest Since Rus-sian Grain DealFalling exports and rising imports next year willgive the US the smallest farm trade surplus since1972, the year before the big Russian grain purchasereoriented American food policy. The USDAestimates that exports will be down about $4.5billion from last year’s record $62 billion. Exportsaccount for about 25¢ of every dollar in farmreceipts. source: Acres, USA, November, 2004

Analysing the Organic Benefit Part IAlyson Mitchell, food chemist at the University ofCalifornia at Davis, reports finding that organictomatoes have a higher level of secondary plantmetabolites and vitamin C than conventionaltomatoes. She also found higher levels of flavonoidsin organic broccoli. She says: “High-intensityagricultural practices can disrupt the natural produc-tion of secondary metabolites involved in plantdefense mechanisms.” A fact sheet discussing recentresearch on the health benefits of eating organic isat: http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/medicalnews.php?newsid=10587.source: The Non-GMO Source, September, 2004

Analysing the Organic Benefit Part IIThe USDA’s Pesticide Data Program (PDP) annu-ally tests thousands of samples of fruits and veg-etables for pesticide residues. An analysis of thatdata from 1993 to 2002, comparing residues bymarket claim (organic, pesticide-free, and no claim)shows a significant advantage for the organicproduce. The below graph illustrates the numbers.source: Organic Processing, July – September, 2004

Personal Care Organic Standards BeingDevelopedOrganic certifier NSF International has announcedcreation of a committee to finalize work on organicstandards for personal care products. The industry’sexperience in this field is checkered. In 2001 theOTA set up a task force to develop such standards,and in 2002 the NOP announced that such standardswould be allowed. But in April of 2004 the NOPreversed itself. In response to industry protests, Ag.Secretary Ann Veneman rescinded that reversal amonth later. The NSF committee will build on theOTA task force’s work and solicits expertise throughJane Wilson at 800-NSF-MARK ex. 6835. source:Acres, USA, November, 2004

Will NOSB Resist Industry Pressure onMethionine?The amino acid methionine is essential to mammalsand poultry, but we cannot synthesize it fromsimpler metabolites and it is not present in signifi-cant amounts in soy. For economic reasons commer-cial poultry operations have long added a syntheticform of it to their feed, rather than purchasingnatural sources. The NOSB, however, has ruled thatafter October, 2005 synthetic methionine will not beallowed in organic production. The OTA has set upa task force to find alternatives, but co-chair BobBuresh of Tyson Foods is suggesting an extensionmay be necessary before it can report. Alternativesinclude fishmeal, potato protein, corn gluten,sasame meal, sunflower meal, field peas, casein,whey, yeast, alfalfa, flax, hemp, green forages,,quinoa and, interestingly, earthworms. Seems theycould solve the feed problem by solving the accessto pasture problem? source: Organic BusinessNews, July, 2004 and October, 2004.

Industry Move In Canada Threatens Farm-ers’ Rights To Save SeedCanadian farmers’ traditional right to save, use,exchange and sell farm-saved seed is being threat-ened by proposals to collect royalties on virtually allseed. A recent review of Canada’s seed productionand regulatory system looked at ways to collectroyalties on seed the growers save from their owncrops, to link crop insurance to the use of purchasedcertified seed, and to increase intellectual propertyprotection for seed companies. “It’s a fundamentalshift in agriculture to the privatisation of seeds,”says Terry Pugh, executive secretary of Canada’sNational Farmers’ Union (NFU). “There are nobenefits for farmers.” Pugh described the process,known as the Seed Sector Review, as an industry-driven restructuring of Canada’s seed productionsystem. Companies such as Monsanto, Syngenta,Bayer and Dupont are pushing for “deregulation”and increased profitability, he said. The aim of thereview is to turn growers from producers of seed toconsumers of seed. sources: http://www.gmwatch.org/archive2.asp?arcid=4484, http://www.gmwatch.org/archive2.asp?arcid=4502

(continued on next page)

T h e N a t u r a l F a r m e r Winter , 2 0 0 4 - 0 58US Declares War on Iraqi FarmersNew legislation in Iraq has been carefully put in place by the US that preventsfarmers from saving their seeds and effectively hands over the seed market totransnational corporations. Food sovereignty for the Iraqi people has beenmade near impossible by these new regulations. The new law in questionheralds the entry into Iraqi law of patents on life forms - this first one affectingplants and seeds. When the new law - on plant variety protection (PVP) - is putinto effect, seed saving will be illegal and the market will only offer proprietary“PVP-protected” planting material “invented” by transnational agribusinesscorporations. The new law totally ignores all the contributions Iraqi farmershave made to development of important crops like wheat, barley, date andpulses. Its consequences are the loss of farmers’ freedoms and a grave threat tofood sovereignty in Iraq. source: http://www.gmwatch.org/archive2.asp?arcid=4538

The Pause That Refreshes: Things Grow Better With CokeIndian farmers have come up with what they think is the real thing to keepcrops free of bugs. Instead of paying hefty fees for patented pesticides, they arereportedly spraying their cotton and chilli fields with Coca-Cola. In the pastmonth there have been reports of hundreds of farmers turning to Coke inAndhra Pradesh and Chattisgarh states. Gotu Laxmaiah, a farmer fromRamakrishnapuram in Andra Pradesh, said he was delighted with his new colaspray, which he applied this year to several hectares of cotton. “I observed thatthe pests began to die after the soft drink was sprayed on my cotton,” he toldthe Deccan Herald newspaper. A leading Indian agriculture analyst, DevinderSharma, commented: “I think Coke has found its right use. Farmers havetraditionally used sugary solutions to attract red ants to feed on insect larvae.”source: The Guardian, November 2, 2004

Teflon Trouble Sticking to DuPontThe EPA filed a complaint last month charging chemical/biotech giant DuPontwith withholding evidence of its own health and environmental concerns aboutan important chemical used to manufacture Teflon. That would be a violationof US federal environmental law, compounded by the possibility that DuPontcovered up the evidence for two decades. Teflon has been hugely successful forDuPont, which over the last half-century has made the material almost ubiqui-tous, putting it not just on frying pans but also on ‘stain resistant’ carpets, fast-food packaging, clothing, eyeglasses and electrical wires - even the fabric roofscovering football stadiums. But Teflon constituents have found their way intorivers, soil, wild animals and humans, and some are known to cause cancer andother problems in animals. One, PFOA, has turned up in the blood of morethan 90 per cent of Americans. John Bowman, a company lawyer, in an internalmemo warned that: “Our story is not a good one…We continue to increase ouremissions despite internal commitments.”source: http://www.gmwatch.org/archive2.asp?arcid=4212

USDA Criticized on Mad Cow Surveillance SystemAccording to a Government Accountability Project (GAP) report, the USDAnew BSE testing program has many critical flaws. The USDA says that it hasscientific protocols for collecting brain samples from suspect animals. Yet thebrain samples are not randomly collected and the animals being tested do notmeet the USDA’s own protocols. Meat inspectors on the frontline of the BSEtesting program continue to lack adequate training. While it’s an inspector’s jobto spot symptomatic animals, GAP has yet to hear from inspectors who feelthey are adequately trained. The USDA disallows independent BSE testing,which would be helpful to domestic beef importers. And if allowed, the USDAseemingly fears the impact of “real” testing by small producers. Felicia Nestor,a Food Safety Policy Analyst for the GAP, offered blunt criticism of theUSDA‚s long plagued BSE surveillance program: “The USDA has carefullychosen an ill-advised campaign to cover up the flaws of a system that endan-gers the both the American public and the American beef industry.”source: Agribusiness Examiner, July 22, 2004

Court Ends FDA Ban on Hemp in FoodA San Francisco appeals court has ruled that the Drug Enforcement Adminis-tration (DEA), not the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), has jurisdictionover marijuana and its active ingredient THC. The ruling came as a result of asuit by the Hemp Industries Association against the Bush administration’sefforts to ban foods containing hemp. The industry argued that the amount ofTHC in foods is insignificant, while hemp is a good source of protein, fiber,and omega-3 and omega-3 fatty acids.source: The Germinator, October, 2004

Corn Screams for HelpCorn plants, when attacked by insects, send out chemical signals to stimulateearly defensive responses report researchers for the Agricultural ResearchService. The signals, called green leafy volatiles, seem to attract caterpillarpredators and parasitoids, natural enemies of the insect predators.source: The Germinator, October, 2004

US Food Not So Safe or Cheap as Claimed?The above PDP study, by Charles Benbrook, also disputes the claim that USfood is the safest in the world. Based not only on levels of residues but otherfactors such as microbial contamination, Benbrook argues that a reasonableconclusion would be that France, the Netherlands, Great Britain and Japan allhave safer food than we do. To evaluate affordability, Benbrook calculatesincome spent per 1000 calories. Using this method, the US average pays $2.28per 1000 calories, while in Sierra Leone the average is 39¢. “Some 90% ofhumanity spends less per calorie of food than Americans,” he says. source:Organic Broadcaster, September – October, 2004

Wonder Bread, Twinkies Baker, Files For Bankruptcy ProtectionInterstate Bakeries Corp., the maker of Hostess Twinkies and Wonder Bread,filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection today. The baker cited the popularityof low-carbohydrate diets for some of its problems. But that was just thefrosting on several layers of recent troubles: high labor costs, unused bakerycapacity and rising costs for ingredients and energy. Still, turnaround expertshired to help Interstate reorganize insisted the company and its brands will bearound for some time. “IBC has some of the most recognizable and popularbaked breads and sweet goods brands in the nation,’’ Tony Alvarez, the newchief executive, said in a statement. Alvarez is the head of a New York-basedturnaround management firm. source: Chicago Tribune, September 22, 2004 Organic farming boosts biodiversityOrganic farming increases biodiversity at every level of the food chain – all theway from lowly bacteria to mammals. This is the conclusion of the largestreview ever done of studies from around the world comparing organic andconventional agriculture. Previous studies have shown that organic farmingmethods can benefit the wildlife around farms. But “the fact that the message issimilar all the way up the food chain is new information”, says agriculturalscientist Martin Entz of the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg, Canada. Thestudy reviewed data from Europe, Canada, New Zealand and the US. Neither ofthe two groups of researchers who did the study – one from English Nature, agovernment agency which champions wildlife conservation, and one from theRoyal Society for the Protection of Birds – has a vested interest in organicfarming. source: New Scientist, 11 October 04

Two More Chains Adopt Organic LinesGiant Foods, and Stop & Shop have both started carrying the “Nature’s Prom-ise” line of private label foods, about 60% of which are organic. They arestarting with 25 items, including milk, soy milk, butter, eggs, cookies, juicesand chips. They expect to expand to 200 items by early 2005. Although pricedover conventional items, the organic products sell for 15% to 20% below otherorganic lines. source: Organic Business News, October, 2004

Surprising Truths about Organic ConsumersA study of organic consumers finds that generalizations are quite difficult aboutthis group. Contrary to popular opinion, they are not largely highly educated,high income white females. In fact Asians and Native Americans are a littlemore likely to be organic consumers than Caucasians. The accompanying tableshows the “user index” for consumers who “at least occasionally” purchaseorganic products. The index is a measure of how likely that group is to buyorganic compared to the general population (index of 100). source: OrganicProcessing, October – December, 2004

T h e N a t u r a l F a r m e rWinter , 2 0 0 4 - 0 5 9

Special Supplementon Organic Meat

by Carl B. Russell

When I was a teenager I participated in a group offriends who were enthusiastic about our outdooradventures. Fishing, hunting, hiking, and camping,we immersed ourselves in natural experience. Likemany of our kind, during summer we would seekdeep cool water to recharge our spirits. One favoriteswimming hole was in an abandoned copper mineon the side of a mountain, several miles from town.A jeep trail led there through challenging terrain,enhancing the adventure.

During mining operations copper ore had beenblasted out of the bedrock, leaving long narrowravine-like shafts. Once abandoned they had be-come filled with water. The steep rock ledges wereburnt-orange, almost red in color. The water wasbright aqua-blue, and milky with suspended sedi-ment. The contrast between green forest, red earth,and brilliant blue water created an exotic visualeffect.

Upon arrival we would race over the barren groundto the edge of the cliffs, and plunge one behind theother into the cold blue water. Once we calmeddown from the initial rush, we would engage in themain purpose for our coming, cliff jumping. Therewas an increasing gradient along one side of themine where we could jump from spots ranging inheight from ten, to as high as sixty feet. We wouldfreely charge out into the air from the lower cliffs,demonstrating different styles of cannon balls anddives. The approach at the highest place was moresubdued. The cliff walls of the ravine were onlythirty feet apart, and from a height of sixty feet anaggressive jump could end dangerously close to theopposite side.

I never found it easy to jump from the high cliff. Iknew that I didn’t have to make the jump, butsomething inside me encouraged me to try. I wouldtake my time ascending, and once on the rockplatform, I would adjust to the challenge in front ofme. From above, the chasm seemed deceptivelynarrow, and as I looked down I would lose my depthperception. I could not see beyond the surface of themilky-blue water, so the view took on a two-dimensional appearance. Light reflecting fromripples would shimmer hypnotically, making thewater level seem to rise and fall, like ocean swells.

Finally, I would be compelled to step off into thinair. The step was my last conscious act. The descentwas so rapid that there was no time to think. I wascompletely dependent upon my instincts to keepupright and prepared for submersion. I can stillremember the sound of the air ripping past my ears,and the sensation of my body tearing through thewater. Gradually slowing down, then regaining

Food FromThought

buoyancy, I had a sense of exhilaration as my mindcaught up with my body, mentally absorbing theexperience.

I found myself recalling these memories as I stoodoutside the pen where I raised my first pigs forslaughter. I had decided to move ahead with achallenge that had been rising within me for years. Ifelt the need to raise and slaughter animals for myown meat consumption. My parents had insistedthat as a young hunter I eat everything I killed. Thishelped in part to shape the current motivation, but ithad also tempered my desire to kill things. A bird onthe wing, or a white-tail deer at fifty yards, is quitedifferent than a pig at hand, and I needed to adjust tothe challenge in front of me.

As I readied myself to enter the pigs’ pen, I couldsee the shimmering in their eyes, too close, too far,too narrow. I was standing at the cliff’s-edge of a setof experiences, the depth and breadth of which Icould not fathom. Even though I knew that I didn’tneed to make the choice to kill my pigs, I wascompelled to. To this day, I have no idea why Itrusted myself to take that step, but I entered the penand did what needed to be done.

I had started this endeavor because I firmly believedthat if I was going to enjoy animal flesh for food,then I had to take responsibility for the killing. Theact of killing became complicated when I realizedhow important the pigs’ lives were to me. These twodistinctly different feelings were difficult for me towrap my mind around. I faced an intellectual chasm,and I could sense the uncertainty that eddied there.After sixteen years I am still in awe of the worldthat opened up around me as I tumbled over thatprecipice.

Killing animals requires skill and commitment. Istarted out with some skill, but more commitment.There are many aspects of slaughtering and butcher-ing that can only be learned through experience, andafter several years slaughtering chickens, cows, andpigs, I started to feel comfortable with the process. Ifelt myself regaining buoyancy, and I began torealize how fast my life had been changing. I hadbeen acting more from instinct than from consciousthought, and I had become submerged in experi-ences that my mind was only beginning to absorb.

There are many emotional issues surrounding thecare and consumption of animals. Because theymove, breathe, and make noise, we can relate to allanimals on a most basic level. Whether cat, deer,chipmunk, draft horse, or milk-cow, we can empa-thize with their life experience. It is enjoyable tohusband farm animals because we can createrelationships with them, which enhance our ownemotional lives. The recognition of the value ofthese relationships to my life is what compelled meto start raising a diversity of animals on my smallfarm.

Beyond feeding, and cleaning pens, I involve myselfin the lives of my animals. I spend time with them,scratching their itches, encouraging them to play,looking into their eyes, and touching them compas-sionately with friendship. They respond positively,

becoming enjoyable, engaging creatures. When theyare alive, it is important to me that they are relaxedand comfortable, and that I have taken time to haverelationships with these living beings.

I know many people who would rather not know theanimals whose meat they may eat. It is common forthem to acknowledge that they would become tooemotionally attached. Often the result is that themeat they do eat comes from animals raised inconfinement and ignored by humans until their meatis processed. This choice is right for a lot of familiesbecause it is convenient, and many people don’thave the space to raise animals, but I am concernedabout the loss of the value of the relationship.

To me food is more than calories or culinary prefer-ence. Food is the energy of life, and life is aboutrelationships. Life is the flow of energy from theEarth through all things. It is the relationshipsbetween all things that keep the energy flowing.Like everything else, humans gather energy, thenexpend it, and eventually we return in totality to thesource. Along the way, it is the relationships that wemake that define our participation.

Once I recognized the significance of my need tohave relationships with the animals whose flesh Ieat, I began to truly feel my connection to Lifeenergy. I feel the same relationship to the trees inthe forest where I work, to the soil that I cultivate,and to the plants in my garden. It is clear to me nowthat energy does not leave an animal when it dies,nor does it leave a bean picked from a vine. Theenergy is always there. By involving myself physi-cally and emotionally in the production of my food,I can strengthen my relationship to that energy. Ialso believe that my involvement can help theseanimals to have vital lives, enhancing the value thatthe food, in turn, brings to my life.

The food that we raise on our small farm rechargesmy body, and my spirit. I am proud of the lovingrelationships we have with our animals. Being theperson responsible for taking their lives is part ofdemonstrating my commitment to them. Acknowl-edging emotional investment substantiates the valuethat I place on their existence. The relationships tomy family, to our community, and to the Earth arestrengthened every day through this connection tofood. These animals and plants that we raise fuel ourefforts to deepen our involvement in the energy ofLife from one season to the next.

While I write this, I am overwhelmed by emotion,and I feel exhilarated as I float in the realization ofpersonal experiences, absorbing the meaning. Thereare many people who, for one reason or another,cannot engage in these experiences, but I encouragethose who think that they can, to try. It is the fear ofuncertainty that causes discomfort, not uncertaintyitself. I have found that I can be afraid, or I can trustmyself, but uncertainty will always exist. Uncer-tainty is what fills the gap where relationships grow.By diving into that abyss I have found a pool ofsignificant reward, and I feel recharged as I watchthe ripples form from my wake and spread acrossthe life around me.

T h e N a t u r a l F a r m e r Winter , 2 0 0 4 - 0 510

by Sarah Flack

“Quality of life begins on the dinner table” statedDavid Kline at a farm conference in Vermont a fewyears ago. And that quality is readily apparent whenI sit down to a dinner that includes lamb raised hereon the farm. Quality is also part of what is continu-ing to create demand for locally raised lamb.

The hillsides and mountains I see from the windowsof my house are now covered in forests, but 150years ago they were open pastures, grazed bythousands of sheep. The market then was mostly forwool, although the per capita consumption of lamb(and mutton) was higher. Then, as now, the demandand price paid for wool produced in our area isinadequate to sustain production. Today, whilesome farmers have found or developed a market forwool, many have shifted their focus to meat produc-tion.

The good news is that the demand for lamb, at leastlocally, seems to be increasing - particularly forfarmers who are direct marketing. Restaurants,farmers markets, local coops and stores, ethnicmarkets, and direct sales from the farm are a fewavailable markets. For sheep farmers, the choices ofhow to raise and market the meat can be dizzying.Should it be 100% grass fed, fed a little grain,“natural”, or certified organic? A sheep farm notonly produces lamb (generally under a year old).The farm might also produce Hogget (lambs in theirsecond summer), and Mutton (older sheep) whichcan either be sold as is or made into sausage, as wellas fiber products and hides.

Opportunities available for today’s sheep farm-ers: There are a growing number of consumersinterested in buying organic, natural and grass-fed

Sheep In The Northeast:Organic, Natural Or Grassfed?

lamb. Consumers looking for grass fed meats areaware that research has shown that grass-fed meatscontain higher amounts of omega-3 fatty acids,conjugated linoleic acid (CLA), carotenoids, andvitamin E. Lamb seems to accumulate more CLAthan other red meats. Some research also indicatesthat animals fed a high forage diet have a lower riskof carrying certain types of food borne illnesses.

While some consumers are looking for lamb fedzero grain, many others are happy to buy “natural”lamb which is raised on pasture and fed a smallamount of grain. The “natural” label is also a way

for an organic farm to market lambs which must betreated with a synthetic de-wormer. Some consum-ers want the “organic” label on the meat they buy,and are less concerned with the amount of grain fedto the lambs.

Whatever market is chosen, if the flock is intendedto be managed as a business, it is important to lookat the costs of production. This information isessential in keeping costs low, and also in setting aprice for meat sales which returns enough to thefarmer.

photo by Sarah Flack

Doug Flack herding ewes and lambs to a new spring pasture on the Flack Farm

T h e N a t u r a l F a r m e rWinter , 2 0 0 4 - 0 5 11Challenges facing today’s sheep farmers: Para-site management is the largest challenge whichorganic sheep producers face. For this reason asection at the end of this article focuses on thatsubject. If any direct marketing is to be done, thereare regulations to meet, labels to make, deliveries,sausage recipes to develop, customer relations andmore. Depending on location, finding a nearbyslaughterhouse and processing facility which canprovide good quality services when needed may bedifficult. For the farmer choosing to raise grass fedlamb, they will need to find sheep with the geneticpotential to do well and create very high qualitypastures. Then they must decide if they will be100% grass fed, or if they will include a smallamount of grain in the ration.

Genetics: Wes Jackson wrote that “Every placeneeds genotypes (cattle, grass…) that are tuned tothat farm. The industrialization of agriculture hashomogenized the genotypes.” Finding sheep whichare resistant, or at least resilient to parasites isessential for an organic sheep farmer. For a farmerinterested in grass feeding, finding sheep which dowell on a high forage diet is needed. For any sheepfarmer, finding healthy animals which require littleassistance at lambing and do well in the localclimate is important. As farmers bring new live-stock to their farms, they must search for the rightanimals which will best fit their farm, and in thisage, they must often look hard to find these idealanimals. Then, once the livestock are living as partof the farm organism, it may take several genera-tions before the livestock on the farm are what isideally suited. Selection and culling choices can bedesigned to create a flock best suited for the farm.

Pastures can be a key way to cut costs on youroperation. They can also be a source of parasites.Sheep are very well adapted to grazing, and can beone of the least expensive ways to improve yourpastures. Sheep can be used to clear brush, tochange plant species composition of a pasture, toincrease plant density, and sheep manure makesgreat fertilizer. Some farmers have figured out waysto get paid to graze their sheep on other peoplesland to clear brush and improve pastures. The useof modern electric fence technology can decrease oreliminate predator problems, and is what makesmanagement intensive grazing possible. For farmsin locations where fence alone isn’t enough to keepout the coyotes or neighborhood dogs, guardiandogs or llamas may be necessary.

Parasites are a concern for all sheep farmers,particularly in a wet growing season. For thecertified organic producer, parasite managementremains the biggest challenges to production. Thisarticle only has room for an overview of thissubject, and additional reading, research and experi-mentation is needed.

To treat internal parasites with herbs or other naturalremedies will require more than just switching frompharmaceutical dewormers to a natural de-wormer.Most natural products work differently and willrequire a more holistic approach with a focus onprevention of infection and creating a healthyanimal with a highly developed immune system.Once infection loads are high, don’t count on“natural” treatments alone.

All farms and all livestock have parasites, so it is amatter of managing the animals in such a way thatthe parasites do not create health problems. It isuseful to learn about the life cycle of the parasites,how they infect livestock, and at what stage of theirlifecycle they are most vulnerable. There are manydifferent types of internal parasites, each withdifferent host organisms and differing life cycles. Itis also interesting to consider what the role ofparasites is, on a farm and in wild animal popula-tions.

Resistance too, or tolerance of parasites varies withbreed, age, previous exposure, selection, immunefunction, soil quality and feed quality. Lambs, withtheir not yet fully developed immune system, aremore susceptible to parasites than mature animals.Grazing management to provide clean (non infec-tive) pastures to the most susceptible livestock,good sanitation, good nutrition, not allowinganimals to get too thin, providing ample colostrum

soon after birth, and selection of hardy animals areall basic in prevention.

Fecal egg counts can be a useful tool in parasitemanagement, but don’t rely on them to tell every-thing about the parasite loads livestock have. Not allparasite species produce many eggs, and there areseasonal variations in egg production. If you dodecide to use fecal egg counts, use them at criticaltimes of the year, the same time each year, andconsider them just part of the overall managementplan.

There is a review of literature on parasite treatmentsin Dr. Hubert Karreman’s book Treating Dairy CowsNaturally. There is also a chapter on parasites in theCanadian Organic Growers Organic LivestockHandbook, and an ATTRA publication on parasitemanagement by Ann Wells D.V.M. Some of thenatural remedies being used on organic farmsinclude: pumpkin seed, black walnut, wormwoodand other Artemesia species, male fern, garlic,cloves, a variety of plants with high tannin contentincluding woody species & brambles, and otherplant species.

Prevention: Pasture management is probably themost important part of the prevention strategy.Minimize or eliminate infection from pasture bykeeping the most susceptible animals out of infectedpastures. Parasites will live and continue to beinfective for about a year (longer in warmer areas)after they are shed in manure on the pasture. Ani-mals which shed the most eggs are usually mothersafter birthing, or lambs. Sheep and goats have(mostly) different parasites than cows, so multispecies grazing can be part of the strategy to createclean pastures. But this requires precise planning,not just a leader follower system or mixed grazing.Not allowing animals to graze the pasture downshorter than 2 inches, particularly in wet weather andon more heavily infected pastures, can also reduceinfection. Other ways to decrease parasite load in a

pasture include harvesting hay, fallowing an area,and rotating with an annual crop. Grazing hightannin plants in hedgerows and pastures seems toreduce parasite loads. (Birdsfoot trefoil, brambles,many woody species). It is also important to notethat farms with a lower stocking rate generally havelower parasite loads.

Sheep can be integrated into a diversified farmorganism to produce wool, meat, sausages, andhides. They can be raised on a larger commercialscale, or as a small backyard flock which can becared for by the whole family. When managed well,they can improve pasture quality, clear brush, andimprove soil fertility. Raising them for your ownfamily or as a business can be rewarding work. Itcan be both spiritually and nutritionally fulfilling,putting you directly in touch with the seasonalnature of producing your own food.

Sarah Flack works part time for NOFA VT, she is anindependent organic and biodynamic farm andprocessor inspector, she consults with individualsand organization, and does public speaking andwriting on a wide array of agricultural subjects.

photo by Sarah Flack

Pasture finished lambs in midsummer.

T h e N a t u r a l F a r m e r Winter , 2 0 0 4 - 0 512

by Tamiko Thomas

The December 2003 discovery of a WashingtonState dairy cow suffering from Bovine SpongiformEncephalopathy (BSE) or Mad Cow Disease wasthe first confirmed American case of this devastat-ing disease. This disease causes its victim’s brain tobecome spongy and ultimately leads to death. It isthought to be transmissible to humans via meatcontaminated with the abnormal prions associatedwith this disease. The human version is calledvariant Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (vCJD) and therehave been nearly 150 cases of it to date. The humanhealth implications of this disease meant the almostimmediate closure of the borders of more than 40nations to American cattle and cattle products. Closeto a year later a substantial number of these bordersare still closed with countries like Japan, one of thetop importers, just now moving towards acceptingAmerican beef imports. In response to all this, thegovernment has announced a series of steps de-signed to address concerns about the safety of thehuman and animal food supply.

Human Food

Within a week of the BSE positive case the UnitedStates Department of Agriculture (USDA) an-nounced a series of interim changes to cattle slaugh-tering procedures in order to safeguard publichealth. Most of the requirements centered aroundreducing the possibility of contamination of beefwith the abnormal prions. In infected animals theseprions are concentrated in certain tissues such as thebrain, eyes, spinal cord, tonsils and parts of thesmall intestine that are therefore considered highrisk. The government has therefore banned tonsils(tonsils have always been considered inedible) andparts of the small intestine from cattle of any age,and the rest of the high risk materials from cattleolder than 30 months of age, from the human foodsupply. In addition, these high risk tissues must alsobe excluded from meat obtained using AdvancedMeat Recovery (AMR) systems. AMR uses pressureto remove muscle tissue from the bone of beefcarcasses. Mechanically separated beef was alsoprohibited because the process involved in making it

Mad Cowin the USA

photo by University of Nebraska

Feedlot raising conditions may be the key to enabling Mad Cow Disease.may result in high risk tissues like spinal cord beingincorporated into the end product. Air injection stunguns, a gun used to render animals unconscious forslaughter, were banned under this ruling. Althoughnot commonly used they were banned because ofconcerns that they could contaminate meat withhigh risk-tissue.

Perhaps the most prudent step taken in response tothe Mad Cow Disease case in terms of protectingfood safety and animal welfare is the USDA’s banon non-ambulatory disabled cattle (downers). Non-ambulatory disabled cattle are understood to be atheightened risk for BSE. All three of the NorthAmerican cattle found to have BSE (one in Americaand two in Canada) have been downers. A Swissstudy (one of several that have established this link)found that downer cattle are about 50 times morelikely to have BSE than cattle identified throughpassive surveillance (i.e., those reported to veteri-nary authorities as BSE-suspect based on clinicalobservation). Animals unable to stand or walk arenot only at a higher risk of suffering from BSE butalso have been shown to have a higher prevalence ofE. coli, Salmonella, and other dangerous pathogensthat can transmit disease to consumers.

Animal advocates have been pressing for this banfor over a decade. Downed animals suffer terribly.Firstly, they suffer as a result of the illness and orinjury that incapacitates them. Secondly, investiga-tions by The Humane Society of the U.S. and otheranimal protection organizations have revealed thatanimals too sick or injured to stand or walk areroutinely kicked, dragged with chains, shocked withelectric prods, and pushed by bulldozers in efforts tomove them at auction and slaughter facilities. Whenthe USDA announced its interim ruling prohibitingthe processing of non-ambulatory disabled cattle forthe human food supply, there was an outpouring ofpublic support. Major retailers, consumer groupsand other nonprofits, and some agricultural organi-zations and individual ranchers expressed strongsupport for the ban as well. In fact, of approximately22,000 comments submitted to the USDA, morethan 99 percent strongly supported the ban.

Another important element is testing for BSE todetermine its prevalence. In March of 2004 Agricul-ture Secretary Ann Veneman announced that theUSDA would expand its BSE surveillance. Theirgoal is to test as many cattle as possible in the high-risk cattle population (cattle exhibiting central