Salt, early complex society, urbanization: Provadiya- Solnitsata (5500-4200BC)

Transcript of Salt, early complex society, urbanization: Provadiya- Solnitsata (5500-4200BC)

1

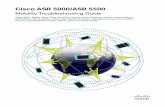

Salz und Gold: die Rolle des Salzes im prähistorischen Europa

Salt and Gold: The Role of Salt in Prehistoric Europe

2

Salz und Gold:die Rolle des Salzes

im prähistorischen Europa

Akten der internationaler Fachtagung (Humboldt-Kolleg) in Provadia, Bulgarien

30 September – 4 October 2010

Herausgegeben von

Vassil Nikolov und Krum Bacvarov

Provadia • Veliko Tarnovo 2012

3

Salt and Gold:The Role of Salt

in Prehistoric Europe

Proceedings of the International Symposium (Humboldt-Kolleg) in Provadia, Bulgaria

30 September – 4 October 2010

Edited by

Vassil Nikolov and Krum Bacvarov

Provadia • Veliko Tarnovo 2012

4

Gedruckt mit Unterstützung der Alexander von Humboldt-Stiftung

Bonn, Deutschland

Printed with the support of the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation

Bonn, Germany

Sprachredaktion: Krum Bacvarov (Englisch), Tabea Malter (Deutsch), Gassia Artin (Französisch)

Grafikdesign: Elka Anastasova

© Vassil Nikolov, Krum Bacvarov (Hrsg.)© Verlag Faber, Veliko Tarnovo

ISBN 978-954-400-695-2

11

Salt, early complex society, urbanization: Provadia-Solnitsata (5500-4200 BC)

Vassil Nikolov

We often do not notice or are not aware of the fact that we are inextricably bound up with seemingly small things without which our lives would be very difficult and even impossible. Such a small ‘detail’ is salt, the common cooking salt. To make our food tastier, we often reach for the salt shaker at the table, rather automatically, without actually thinking for a while that our lives would not be possible if there were no salt. It is not because our food would feel kind of tasteless but because without a certain amount of salt per day the human organism would not be able to function since sodium chloride plays a unique physiological role in maintaining the osmotic equilibrium in all animal organisms.

The minimum dose of salt necessary to maintain the life of a grown-up individual on the verge of biological death in a static state is 4 g per 24 hours. With double that dose per day one could live normally but without making any physical efforts. It is generally assumed that for doing normal physical activity man needs 2 g of salt per 10 kg of weight, i.e. in most cases between 12 and 18 g daily. Under extreme physical exertion the norm could be higher. The chronic and even minimal shortage of salt causes serious fertility disorders leading to sterility, retarded development and complex body damages. The moderate salt shortage leads to a state of permanent fatigue, anorexia, nausea and vomiting, any physical effort being impossible. At high salt deficiency in the body the symptoms mentioned increase thus causing death.

Since the physiology of animals is similar to that of humans, they also need the respective amount of sodium chloride. Providing it to domestic animals is the task of those who breed them because their fertility, weight (meat for food!) and the quantity of milk produced depend on that salt. Animals used for work require considerably bigger daily amounts.

The healing properties of salt, which were surely noticed and used as early as the later prehistory, should also be taken into account.

The problem of planned provision of salt both for man and domestic animals did not exist for the most part of human history. Paleolithic hunters ate the meat of wild animals thus getting the necessary daily salt intake and the animals themselves found salt in nature: salt springs, salt stones, halophyte (containing sodium chloride) plants, etc. A problem arose during the transition to food production, i.e. the transition to a Neolithic type of culture about 12-14 thousands of years ago in Southwest Asia. People became producers of cereals and began to raise domestic animals. The role of hunting wild animals sharply decreased and the problem – not realized until then – of providing the vital supplies of salt occurred. With the development of a settled way of life, salt became the only strategic raw material during the Neolithic, a raw material without which the new subsistence strategy could not function.

To the highly important functions of salt for that period we should add its use for food preservation which was a must in the everyday life of the early agricultural society. The preservation of food reserves for regular all-year-round maintenance of the settled way of life was part of the newly created system of relations with the natural environment. Besides, salt was also needed for various domestic production activities, primarily those related to cattle hide processing and use.

V. Nikolov & K. Bacvarov (eds). Salz und Gold: die Rolle des Salzes im prähistorischen Europa / Salt and Gold: The Role of Salt in Prehistoric Europe. Provadia & Veliko Tarnovo, 2012, 11-65.

12

As a strategic raw material during the later prehistory, salt became a strong economic base of the community that produced it and a necessary prerequisite for the development of trade contacts, respectively. In this way salt became the motive power of social and cultural processes.

All those problems usually don’t attract the attention of the scholars of the past. The reasons are easily explainable. Archaeologists build up their ideas of the culture based mainly on the excavated material remains and observations of the respective contexts. Due to their high solubility in water, the hard salt lumps, which happened to get in the cultural deposit, were washed out long ago and hence cannot be identified during an archaeological excavation. Therefore, it is also difficult to make an unambiguous interpretation of installations and other material elements of the production processes.

Until recently there were no real evidence on salt production and use during the later prehistory in Bulgaria. Only speculations have been made related primarily to using sea salt for that purpose and possibly water from the presently existing low flow-rate salt springs. The specialized productions and activities during the later prehistory were until not long ago on the periphery of archaeological research.

Farming, cattle-breeding and hunting as well as the associated domestic productions during the later prehistory required proper natural and climatic conditions. Such conditions were available in huge areas of the Old World including Southeast Europe. Unlike the main livelihood, specialized activities were those that could be done in a limited coverage of particular geographic areas in view of their natural assets or such activities that resulted from the exploitation of specific natural assets. The appearance of specialized activities does not necessarily mean that their technological level could be estimated as definitely higher than the ‘normal’ people’s livelihood. The differences were certainly in the two directions. However, for the specialized activities small groups of producers appeared who partially or completely were separated from the traditional livelihood and served another economic

Fig. 1. Provadia-Solnitsata. A view from the east during the excavations in 2008

13

sphere necessary for the community. The sphere of specialized activities was expressed in a limited number of types related mainly to raw material procurement and processing as well as the realization of the production through exchange or trading. The specialized activities during the later prehistory in Bulgaria involved mostly copper and gold metallurgy, manufacturing of long flint blades and other specific artifacts as well as long-distance trading. Now we could also add to this list the production of salt by evaporation of brine.

Provadia-Solnitsata: an expected surpriseIn 2005, excavations began on the complex archaeological site of Provadia-Solnitsata near

Provadia in Northeast Bulgaria1. The complex includes a prehistoric – Neolithic and Chalcolithic (6th and 5th mill. BC) – tell upon which and with part of whose cultural deposit a Thracian tumulus was heaped thousands of years later as well as large prehistoric production and ritual sites around the tell.

Tell Provadia-Solnitsata – which, before being partly destroyed by the tumulus builders, had a cultural deposit 9 m thick and was 105 m in diameter – and the nearby Neolithic/Chalcolithic production site, the Chalcolithic ritual site and the Chalcolithic cemetery are located over the big truncated cone of the only rock salt deposit in the Eastern Balkans, the so-called Mirovo salt deposit.

1 The archaeological excavations are carried out every year for a period of two months, including 2011. They are funded by Nelly and Robert Gipson (U.S.A.), the Bulgarian Ministry of Culture and the Provadia Municipal-ity. Over the years the team has included the following archaeologists: Victoria Petrova, Krum Bacvarov, Petar Leshtakov, Elka Anastasova, Margarita Lyuncheva, Nikolay Hristov, Kamen Boyadzhiev, Desislava Takorova, Stoyan Trifonov.

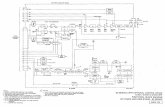

Fig. 2. Field-site plan of the Mirovo rock salt deposit, with the salt mirror boundaries and the location of the archaeological site of Provadia-Solnitsata

14

Fig. 3. Mirovo rock salt deposit. North-south geological cross-section

The formation of the large salt cone occurred when under strata pressure a huge amount of salt mass in a plastic state was lifted upwards to the surface. The salt cone is enveloped on all sides by a kind of marl ‘mantle’ protecting it from washout. Its upper surface is ‘a salt mirror’ (a thick salt solution having a thickness of approx. 1 m) located at a depth of 12 – 20 m. It is shaped like an ellipse measuring 850 x 450 m and has an area of 330 000 square meters. The salt cone reaches a depth of 4000 m where its diameter exceeds 15 km. Salt springs flowed out from the ‘salt mirror’ with salt concentration values very close to the maximum which for brine is 312 grams per liter.

It would have been very unusual if such a beneficial deposit with salt springs flowing out of it had not been used during prehistory. The events that happened followed the natural course of things. Moreover, the remains from the lives and activities of the people in that region during the 6th and 7th millennium BC also turned out to be beneficial. Seven seasons of archaeological excavation at Provadia-Solnitsata also changed our ideas about the prehistory of the Eastern Balkans.

Salt production facilities and salt productionAt the beginning of the Late Neolithic Karanovo III-IV culture which covered the whole of

Thrace, a group of people crossed the Balkan Range, settled near the salt springs at Provadia and began to produce salt. According to the calibrated radiocarbon dates obtained for the earliest stage of the new settlement, it happened circa 5500 BC. The reason for the risky undertaking in a foreign, possibly hostile environment was that Thrace lacked the vital salt sources although at that time all other conditions for the prehistoric farming and stockbreeding were better than those in Northeast Bulgaria.

During the first two or three centuries of the Late Neolithic (i.e. during its first stage, LN1), salt production near Provadia was carried out by evaporation of brine from the springs in thin-walled bowls specially made for the purpose placed in specially built solid dome ovens. The ovens whose production capacity was about 10 tons hard salt per year were located in buildings within the settlement. It has been proved that the evaporation of brine in bowls is the earliest application of that salt production technology recorded in Europe and Provadia-Solnitsata is the earliest salt production site on the Old Continent discovered so far. Its production was intended for ‘export’.

15

Fig. 4. Provadia-Solnitsata. Southeastern area. A two-storey building: remains from a dome oven for brine evaporation. Late Neolithic 1, 5500-5200 BC

The remains of a Late Neolithic two-storey building were excavated there which had an area of 55-60 square meters. A large dome-like installation made of clay was uncovered on the ground level which was designed for the evaporation of brine. It is four-sided, with bulging walls and rounded corners. Its dimensions along the two axes are 1.70 x 1.50 m. It consists of a solid dome and a thick inner floor of strongly beaten clay; there is no base raised above the room floor which was typical of the home ovens. The role of the heat accumulating body in that case was transferred primarily to the solid dome thus implying a different use of the installation compared with that of the home ovens. After removing the remains from the oven, a red spot of the same area emerged in the clayey layer under the floor which reaches at least 30 cm in depth; that layer obviously also accumulated a considerable amount of thermal energy needed for the evaporation process.

The dome is a well-baked red solid clay installation. The walls at the base are about 25 cm thick thinning out upward to 13-14 cm at a height of 40 cm. Judging by the dome walls preserved in their original form, its maximum height on the inside must have been approx. 50 cm and on the outside approx. 60 cm, respectively.

The installation had two entrance openings. They were shaped up in the eastern and southern side of the dome. The eastern one is 26 cm wide, with a preserved height of 25 cm. A low clay podium was made in front of it. The second opening was located in its southern wall and was much larger, probably 60 cm wide, but is poorly preserved. There was a clay podium in front of it, too.

The presence of two openings in the dome of a Late Neolithic oven is unusual. The most probable reason for the appearance of the small side hole was the technological need for maintaining a certain temperature regime during the brine evaporation process and the salt crystallization as well as the need to provide draught for carrying away the vapor which was possible to achieve only by a controlled

16

Fig. 5. Provadia-Solnitsata. Southeastern area. A two-storey building: remains from a dome oven for brine evaporation. Late Neolithic 1, 5500-5200 BC

access of air to the installation. The bowls with brine were inserted through the large opening and taken out with hard salt in them at the end of the cycle.

The abovementioned bowls for obtaining pure salt by brine evaporation are a specific pottery type that was discovered for the first time in the European later prehistory. These are thin-walled deep bowls for special use cast in mold. The surface of the evaporation bowls is roughly smoothed on the outside and well smoothed on the inside; as a result of their use it is now covered with a thick whitish limestone accretion. The bowls are thin-walled and this is the reason why they have been uncovered in a fragmentary state. The wall thickness varies between 3-4 and 5-6 mm, increasing up to 10 mm at the mouth for strength. The thin walls of the specially made bowls heated quickly thus facilitating the brine evaporation.

The production bowls are wide open, with a deep biconical body whose most bulging part is located in its upper third part. The bottom diameter is 11-18 cm. Their mouth is 32-56c m in diameter, rounded and slightly thickened on the inside.

The inverted mouth-rim of the bowls prevented the outflow of brine in the oven while inserting the full vessels in it as well as in case of undesired boiling during the evaporation process. The maximum temperature reached during the boiling was not allowed to exceed the boiling point of brine with sodium chloride concentration of about 312g/l (the natural concentration of brine from the springs near Provadia or that obtained by the preliminary ‘thickening’ of the brine exposed to the sun during the warm months) which is 105˚С. Taking into account the area of the sub-dome space of the oven as well as the capacity of the bowls filled up with brine to the level of their maximum diameter (6 - 36 l), it can be assumed that with optimal arrangement by combining bowls of different diameters, it was possible to evaporate about 90 l of brine at one feeding of the installation.

17

Fig. 6. Provadia-Solnitsata. Southeastern area. A two-storey building: the preserved part of the dome of the brine evaporation oven. Late Neolithic 1, 5500-5200 BC

Therefore, at the relevant concentration of sodium chloride in the brine for one cycle performed per day (theoretically at least two cycles are possible), 26-28kg of purified hard salt would have been obtained, i.e. up to 10 tons annual output in one oven only.

The use of a version of dome oven for the evaporation of brine during the Late Neolithic was a direct consequence of the level of knowledge and experience of the time in the construction of thermal installations; dome ovens appeared in the Early Neolithic and were used for heating and food preparation, and possibly as pottery kilns as well. Open fire is very difficult to control so that it was not suitable for part of the activities. Therefore, the brine evaporation installation was built using the knowledge about the dome oven made of clay.

In the Southeastern area of the tell, a very small part of the Late Neolithic layer has been excavated so far where only the oven described has been explored. In the Northwestern area, however, a considerable amount of sherds from the abovementioned specialized ceramic bowls for brine evaporation has been found which originate from the destroyed Late Neolithic layer there. This is an indication that evaporation ovens were built over the whole territory of the settlement since the first stage of the Late Neolithic. Their small production capacity as well as the inconveniences created by the production process within the settlement and especially in the buildings demanded a change in the brine evaporation technology. That happened during the second stage of the Late Neolithic in the region (LN2) which comprised the last two centuries of the 6th and the first century of the 5th mill. BC. For the time being only individual finds, mainly pottery sherds, have been uncovered which belong to that Late Neolithic phase; in the excavated small-area sections the deposit of that period was destroyed as early as ancient times.

However, two pit installations for brine evaporation belong to the second stage of the Late Neolithic. They are located about 150 m from the tell near the then Provadia River bed and near the

18

Fig. 7. Provadia-Solnitsata. Southeastern area. A two-storey building: shapes of ceramic bowls for brine evaporation in an oven. Late Neolithic 1, 5500-5200 BC

one of the salt springs found in the 20th century. One of the installations was excavated during the last excavation season. It was filled up and covered with an ashy-white layer containing a huge amount of highly fired pottery sherds and daubs. The installation itself was built up of clay and was also highly fired during its operation. All observations testify to traces of a production process by a strong fire using wood. According to the peculiarities of the shapes and the surface treatment, the fragmented pottery found within the installation has so far been unknown but it presents enough evidence for its dating to the last phase of the Eastern Balkan Neolithic.

The Late Neolithic pit installation has a kidney shaped layout. It is dug to a depth of 40 cm in the virgin soil. Its long axis is ESE-WNW-oriented; its length is approx. 3.30 m (the western end of the installation is destroyed by a recent trench). Its width (along the NNE-SSW line) is about 2 m. The installation has four compartments divided by three nearly parallel clay ribs aligned to its long axis. Their height is up to 30 cm but all three of them rise up to the level of the virgin soil which the installation is dug into. The four troughs have a somewhat V-shape, i.e. the clay ribs widen downwards and the bottom of each trough deepens gradually towards the center. The ribs have slightly conical cross section: their

thickness at the base is 20-24 cm and at the top they are leveled and have a width of 12-15 cm (the top parts of the ribs were additionally plastered to obviously maintain that width and the leveled upper surface). The four troughs of the installation end on both open (?) sides with a slight rounding; they are also shallower there. The width of the outer troughs is 25-26 cm and their depth is up to 25 cm. The width of the inner troughs is 35-36 cm and their depth is up to 35 cm. The floors of the four compartments were plastered with clay (probably additionally plastered as well): plastering of 1-2 cm thickness has been preserved in some places. Two low ‘thresholds’ about 10 cm wide and 7-8 cm high have been made on the bottom of one of the inner troughs at a distance of approx. 80 cm from each other and almost across the axis. The northern part of the northern compartment is shaped like a high segmented step (20 cm maximum width). The installation was open to the east; it is not clear whether it was open to the west. On the north and south it was surrounded by a thin clay wall which probably rose above the surrounding terrain but it is not clear to what height it rose. (I suppose that due to the frequently blowing northeast wind on that side it was higher; in fact it was probably that wind that caused the whole installation to take a streamline kidney shape.) The remains from the installation are now brick-colored as the result of the multiple heating; it is decreasing towards the eastern end. A layer of whitish ash has been found on the bottom of the four troughs which reaches a thickness of up to 12 cm in the inner compartments.

In result of the preliminary processing of pottery sherds, a new type of brine evaporation bowl was identified. That is a deep vessel with a low and slightly inverted upper part, with a rounded carination but with two opposite massive lugs which come out of the mouth rim almost horizontally or angle slightly upwards. The bowls have fairly thin walls (5-8 mm) but their inner surface is almost always thickly coated with a thick layer of clay (2-3 mm) different from the main body, and their outer surface is rough. This coating had probably been made after the vessel dried completely because the cohesion

19

Fig. 8. Provadia-Solnitsata. Southeastern area. A two-storey building: brine evaporation bowl lying bottom upward by the oven. Late Neolithic 1, 5500-5200 BC

between the bowl’s wall and the additional clay layer is weak and on most sherds that coating has fallen off. The wall surface is very dense and probably contains kaolin; it is very well smoothed and often burnished. According to their size, the bowls fall into two main groups: 1) with a maximum diameter of approx. 35 cm; and 2) with a maximum diameter of 25 cm. All bowls have a comparatively narrow bottom (outer diameter 8-10 cm).

These deep ceramic bowls were made for use in the pit installations. I suppose they were filled up with brine and arranged one next to the other in the trough corresponding to their size in such a way that the massive opposite lugs should rest on two neighboring ribs. The bowls’ bases probably did not reach the bottom of the installation. The remaining empty space around and under the vessels was apparently filled up with firewood whose burning caused the brine to evaporate. The sherds from small inverted conical or almost cylindrical vessels found there were probably used to obtain smaller salt cakes; it is possible that these bowls were arranged on the segmented extension in front of the eastern rib of the installation. According to the preliminary calculations, one feeding of the installation yielded more than 100 kg of hard salt. In comparison with the capacities of the oven discussed above, the new installation in the Late Neolithic production site was about four times more efficient.

The life on the tell continued during the Middle Chalcolithic (Hamangia IV culture), i.e. in the period between 4700 and 4500 BC. It was during that time when immediately by the settlement a large salt production site appeared which partly covered the remains of the Late Neolithic production site. It operated also throughout the Late Chalcolithic Varna culture, i.e. at least in the third quarter of the 5th millennium BC (4500-4200 BC) when the settlement reached its heyday. The driving force behind the fast technological development was the apparent need to increase the production of salt for the market.

20

Fig. 9. Provadia-Solnitsata. Southeastern area. A two-storey building: a brine evaporation bowl as well as sherds of such bowls lying by the evaporation oven. Late Neolithic 1, 5500-5200 BC

21

Fig. 10. Provadia-Solnitsata. Southeastern area. A two-storey building: stone pounders used in saltmaking. Late Neolithic 1, 5500-5200 BC

Based on the achievements at the end of the Neolithic, the technological process was modified in during the Middle Chalcolithic. The Late Neolithic open-air installations were a step forward to the construction of much larger open-air installations: deep and wide pits in which a new type of ceramic vessels were densely packed next to each other: very deep and thick-walled tubs of much larger volume than the Late Neolithic bowls. The brine was evaprated by the technique already established for centuries, i.e. by an open fire lit on the pit’s bottom in the spaces between the tubs touching one another with their mouths.

The Chalcolithic production site has an area of at least 0.5 hectares but in fact it may turn out to be larger. It is located immediately to the northeast and partly to the north of the tell. The locations of at least 5 big saltmaking installations have been identified in it so far.

Most of one production pit has been excavated which was used to evaporate brine at the end of the Middle and the beginning of the Late Chalcolithic. It was subsequently filled up with the materials from the cleaning of the neighboring production pit. The installation has an irregular, nearly oval shape and it gets narrower in its northern part. Its N-S axis is about 10.50 m long and its maximum width is probably around 8 m. The pit’s maximum depth is 1.85 m; ca 1 m of it is dug into the virgin soil. The southeastern part of the pit opens to a wide ‘chute’, which provided the access to the installation.

Very low ‘walls’ of thick yellowish clay have been uncovered at the installation’s bottom which divide four separate features, ‘basins’ of oval or round shape. A deposit of reddish-brown loose soil with some pottery sherds overlies certain areas of the bottom.

The installation is almost filled up with sherds of thick-walled ceramic vessels used for brine evaporation during the Chalcolithic. They are made of clay tempered with a big amount of large inorganic and organic admixtures. Their outer surface is intentionally rusticated whereas the inner one is very well smoothed and often coated with kaolin in order to become permeable thus protecting the vessel from cracking during the production process. Their color is most often light brown or beige brown. The tubs were additionally coated on the outside with a layer of clay mixed up with finely cut straw or animal dung (probably to increase their thermal capacity). They are very deep open tubs with an inverted

22

Fig. 11. Provadia-Solnitsata. Southeastern area. A two-storey building: a hoard of four antler sickles at the bottom of a grain storage bin. Late Neolithic 1, 5500-5200 BC

conical body. Their mouth diameter is between 30 and 70 cm, while at the base it is between 15 and 40 cm. The wall thickness ranges from 0.8 to 2.5 cm. Most tubs have two pairs of opposite vertical conical lugs each; tubs with pairs of one or three lugs are rarer (apparently they made it easier to get a better hold of the heavy vessels when moving them).

Sherds of smaller roughly made deep tubs with a mouth diameter of 10-12 cm have been uncovered in the pits; intact or fragmented ornithomorphic (bird-shaped) vessels have also been discovered as well as ceramic discs; all three types of finds played a role in salt production.

The small number of fine ware in the pit installation dates it to the end of the Middle and the beginning of the Late Chalcolithic (ca. 4550/4450 BC).

The change in the technology of salt production by brine evaporation is obvious: the Late Neolithic open-air production installations were replaced by much more efficient pit installations. The deep ceramic tubs were probably arranged at the bottom of the pit in such a way that their mouth rims touched one another and the peripheral tubs touched the pit walls. Having in mind their height and inverted conical shape with sometimes considerably larger mouth diameter compared with the base diameter, it could be assumed that large spaces widening downward remained between the parts of the tubs below their mouths. That effect was apparently purposefully sought. The spaces were probably filled up with fire wood. Throughout the entire evaporation process the fire heated laterally mainly the upper part of the brine in the tubs; during the evaporation, the level of the liquid dropped down and so did the level of the fire burning outside. With the fire dying away the temperature dropped down as well thus creating conditions for the salt crystallization process to take place. Hard conical salt cakes remained in the tubs which were suitable for transportation even at great distances.

The Chalcolithic saltmakers near Provadia found a perfect technology for a much faster and considerable salt production for that period which can reasonably be labeled ‘industrial’. The future

23

Fig. 12. Provadia-Solnitsata. Neolithic production site. Pit installation for brine evaporation. Late Neolithic 2 (5200-4900 BC)

Fig. 13. Provadia-Solnitsata. Neolithic production site. Pit installation for brine evaporation: lugs used to suspend the evaporation bowls in the installation troughs. Late Neolithic 2 (5200-4900 BC)

24

Fig. 14. Provadia-Solnitsata. Chalcolithic production site. A moment of the excavation of the large pit installation for brine evaporation. Middle/Late Chalcolithic, 4550/4500-4200 BC

Fig. 15. Provadia-Solnitsata. Chalcolithic production site. A moment of the excavation of the large pit installation for brine evaporation. Middle/Late Chalcolithic, 4550/4500-4200 BC

25

Fig. 16. Provadia-Solnitsata. Chalcolithic production site. Fill’s profile of the Late Chalcolithic pit installation for brine evaporation. Middle/Late Chalcolithic, 4550/4500-4200 BC

26

Fig. 19. Provadia-Solnitsata. Chalcolithic production site. A sherd from a large brine evaporation tub. Middle/Late Chalcolithic, 4550/4500-4200 BC

Fig. 18. Provadia-Solnitsata. Chalcolithic production site. Line drawing reconstruction of a large brine evaporation tub. Late Chalcolithic, 4500-4200 BC

excavations and lab tests will clarify the details of that new technology. This also applies to the role of the dug-in middle part of the bottom of the production pit.

The change in the salt production technology established which led to possibilities for a sharp increase in the production capacity of the ‘factory’ near Provadia during the Late Chalcolithic provides a strong argument for the assumed connection between the salt production and salt trade there as well as the astonishing wealth of prestige artifacts of that period in the ‘golden’ Varna Late Chalcolithic cemetery located in the same region. The discovery of the Middle and Late Chalcolithic production site comprising a huge area enables us to support the idea and give a well-grounded explanation of that phenomenon. Besides, no other Neolithic and Chalcolithic salt production site that used the abovementioned highly efficient technologies has been identified so far in southeast Europe; technologies whose principles have remained valid in saltmaking until the present day.

Fig. 17. Provadia-Solnitsata. Chalcolithic production site. Line drawing reconstruction of large brine evapora tion tubs. Middle/Late Chalcolithic, 4550/4500-4200 BC

27

Fig. 20. Provadia-Solnitsata. Chalcolithic production site. A heap of sherds from brine evaporation tubs from the fill of the pit. Middle/Late Chalcolithic, 4550/4500-4200 BC

Fig. 21. Provadia-Solnitsata. Chalcolithic production site. Reconstruction of the brine evaporation pit during its operation

The Late Neolithic saltmakers of Provadia-Solnitsata (5500-4900 BC) met their own demand for the vital substance most probably by using the very spring brine while the hard produce was ‘exported’ to the south of the Balkan Range. During the Middle and Late Chalcolithic (4700-4200 BC) the production apparently reached industrial quantities for that period. Hard salt, which at that time played the role of money, became a general equivalent in a large-scale trade with neighboring regions but mainly to the south of the Balkan Range.

28

Fig. 22. Provadia-Solnitsata. A small ornithomorphic pot used in saltmaking. Middle Chalcolithic, 4700-4500 BC

Fig. 23. Provadia-Solnitsata. A hoard of ceramic ‘ladles’ connected with the brine evaporation process. Middle Chalcolithic, 4700-4500 BC

The settlement and its fortified wallsThe wealth accumulated by the saltmakers had somehow to be defended. Therefore, during the

Middle and Late Chalcolithic the settlement on the tell was strengthened with a strong fortification system. As is demonstrated by the excavations in the two large areas, the Southeastern and the Northwestern areas, it passed through several phases of changes and development. The main reason for the new erection of the fortification was probably its destruction during an earthquake or the need for expanding the settlement.

29

Fig. 24. Provadia-Solnitsata. Southeastern area. The fortification system of the settlement: stone bastions, a palisade and a moat. Middle Chalcolithic, 4700-4500 BC

That part of the defensive system which has been excavated in the Southeastern area consists of an arc-shaped moat and a gated wall at a small distance behind it. The moat was excavated in the virgin soil. It was made at the beginning of the Middle Chalcolithic. Its width in the upper part is at least 2 m and in some places up to 3 m, and its depth is between 2.20 and 3.30 m. It has a highly asymmetric trapezoid profile narrowing downward. The first Middle Chalcolithic fortification wall consists of two connected parts built in different techniques: a clay palisade with wooden posts, and stone bastions. In the southern zone of the area, the palisade is located at a distance of 3-4 m behind the moat. It consists of a massive vertical timber structure with a thick clay coating. Its width is approx. 80 cm and its minimum height is about 3 m. The palisade reaches the southeastern gate of the settlement which is flanked by two stone bastions made of very large quarried rocks. The dimensions of the bastions at the southeastern gate are 4.50 x 3.30 m and they were more than 3 m high. The gate is approx. 2.40 m in width as wide as the street beginning there which leads to the center of the settlement. It is not clear yet whether the defense system continued to the north of the gate with a palisade again; however that assumption seems to be quite probable.

Circa 4600 BC, the fortification system of Tell Provadia-Solnitsata was badly damaged by an earthquake. The restoration of the two bastions at the southeastern gate was much more complicated than the construction of new ones. The new bastions were built behind the ruined ones though smaller stones were used to make them and they were L-shaped. The thickness of their wall is 1.20 m and they are over 3 m high. In the southeast they are connected with the palisade again and in the northeast a stone wall continues (partially excavated so far). Since the defense moat was filled up with the stone debris of the bastions, a new moat was excavated in front of the gate. The two new ‘bastions’ were probably not used for a long time either. They were ruined during the next earthquake at the end of the Middle Chalcolithic, ca. 4500 BC.

30

Fig. 25. Provadia-Solnitsata. Southeastern area. The foundation of the defense wall (palisade). Middle Chalcolithic, 4700-4500 BC

31

Fig. 26. Provadia-Solnitsata. Southeastern area. Remains of the southeastern stone bastions, the palisade and the defense moat. Middle Chalcolithic, 4700-4500 BC

The remains of three successive Chalcolithic fortification systems built of stone have been excavated in the Northwestern area of the tell.

The earliest defense wall was built during the Middle Chalcolithic along the periphery of the settlement. In the excavated – ca 32 m long – section it is straight, oriented NNE-SSW. It is 2 m wide and built by the opus emplectum technique (larger stones on the faces and smaller ones on the interior). Clay was used as binder. At the northern end of the excavated section the wall has been preserved at a height of 1.50 m; part of the façade of the interior wall can be seen in which eight horizontal stone courses can be counted. It is slightly inclined inward, i.e. at least on the inside the wall narrows in height. For the time being it is impossible to establish a direct connection with the defense structures in the Southeastern area but most probably that wall belongs to the earliest fortification system of the tell to which the two big bastions made of large rocks in the other area can be referred to. Having in mind that the wall in the Northwestern area comes out into the settlement periphery, at least with its southern end, I assume that the first fortification of the tell was angular in shape. In the Northwestern area it was not connected with a defense moat; in fact a defense moat may have existed only on the southern side of the fortification system. The first fortified wall described was very likely ruined during the already identified earthquake ca. 4600 BC.

The excavated part of the second defense wall in the Northwestern area rests mostly on the first one, slightly rotated to the left (in relation to the north direction). It was built by the same emplectum technique, with clay used again as binder. A 12.5 m length of the wall has been excavated. It is arc-shaped and is probably part of a round fortification. Its thickness at the base in the southern zone is 2.40 m and in the northern one it is more than 3 m; a small bastion probably existed there. The front part of the wall in the southern zone is built of tightly arranged ‘face’ (even-sided) stones; seven courses (1.50

32

Fig. 27. Provadia-Solnitsata. Southeastern area. Remains of the northeastern stone bastions, the eastern gate of the fortification and defense moat. Middle Chalcolithic, 4700-4500 BC

Fig. 28. Provadia-Solnitsata. Southeastern area. Part of the foundation of the Northeastern L-shaped bastion (a view from the inside). Middle Chalcolithic, 4700-4500 BC

33

Fig. 29. Provadia-Solnitsata. The tumulus and the Northwestern area, with the three stone fortifications. Middle and Late Chalcolithic, 4700-4200 BC

Fig. 30. Provadia-Solnitsata. The Northwestern area, with the three stone fortifications. Middle and Late Chalcolithic, 4700-4200 BC

34

Fig. 31. Provadia-Solnitsata. The Northwestern area, with the three stone fortifications. Middle and Late Chalcolithic, 4700-4200 BC

m high) have been preserved, the ones following upward being destroyed during an earthquake which toppled the upper part of the wall to the east. It is possible to reconstruct approximately its height which in that place was over 3 m. The front part of the wall in the northern zone is less preserved though it was built in the same manner. Part of the interior face has also been preserved which is inclined inward and exhibits wall narrowing in height; at least five horizontal stone courses have been identified in its preserved part which are somewhat smaller than those on the front part of the wall. The emplectum is made of comparatively small stones. The direction of the wall to the south remains unclear but it is very probable that it was connected with the two Middle Chalcolithic L-shaped bastions of the Southeastern area. However, until now the exact dating of the second wall has remained unspecified despite the fact that its base lies in the Middle Chalcolithic deposit of the tell; a long time after it was built, at an earlier phase of the Late Chalcolithic, a two-storey building was erected, i.e. at that time (and even later on) it continued to exist.

The third and outermost defense wall excavated in the Northwestern area was built during the Late Chalcolithic; this is a new type of stone structure. It consists of stone facing on the steep periphery of the tell, several meters high (at that time) and a solid stone wall2 rising above it. There are no remains of a moat. The facing of the steep cut slope of the tell is made of small and medium-sized quarried rocks and is up to 1 m thick. It covers both the slope and its foot. The aim was apparently strengthening the peripheral part of the tell’s deposit and protecting it from weathering thus providing a solid foundation for the uprising heavy stone wall on the outermost boundary of the tell. The base of that wall was built of very large stones but obviously smaller ones were used upwards; now they are scattered (probably by an earthquake) along the uppermost surface of the prehistoric layer which testifies to the wall being 2 It is very likely that in the 1950s the third stone wall was badly damaged by a heavy excavator during the inva-sion of treasure hunters. The ‘cuts’ from the shovel are across the wall route and are at least 90 cm wide. It was probably at that time also when heavy machines dug out a 6 m wide and very deep cut through the tumulus’ heap which disturbed the Late Chalcolithic layer of the tell. Then, in that area, the upper part of the third wall was destroyed.

35

Fig. 32. Provadia-Solnitsata. Northwestern area, defensive walls 1 and 2: a view from above. Middle and beginning of the Late Chalcolithic, 4700-4400 BC

36

Fig. 33. Provadia-Solnitsata. Northwestern area, defensive walls 1 and 2: a view from the south. Middle and beginning of the Late Chalcolithic, 4700-4400 BC

Fig. 34. Provadia-Solnitsata. Northwestern area, defensive wall 2: a front side detail. Beginning of the Late Chalcolithic, 4500-4400 BC

37

Fig. 35. Provadia-Solnitsata. Northwestern area, defensive wall 1: a detail from its inner face. Middle Chalcolithic, 4700-4500 BC

used until the end of the existence of the settlement, i.e. to the end of the Varna culture. Part of a possibly rectangular bastion has been excavated which protrudes in front of the wall. It is made of rammed earth and faced with medium-sized stones. Unfortunately, when the tumulus was erected, the remains from that last defense system in the southeastern half of the tell were destroyed.

Several Chalcolithic tells with fortification systems have been excavated in Northeastern Bulgaria so far. In comparison with them, the fortifications of the Middle and Late Chalcolithic settlement of Tell Provadia-Solnitsata have several peculiarities. The space surrounded by a defense wall is considerably larger than that of the Chalcolithic settlements in the region. The combination of a defense wall and a moat has been found at only one more tell site. The construction of a stone fortification with solid walls during the Middle and Late Chalcolithic has until now been identified only at Provadia. The facing of the Late Chalcolithic defense system is analogous only with the one found in the Kamchia River valley. The combination of a palisade and stone bastions has no parallel during the Chalcolithic in the region.

The successive settlements defended by these powerful fortifications have so far remained unexplored. The reason for that lies in the fact that the southeastern part of Tell Provadia-Solnitsata has been considerably ruined by the builders of the tumulus; the tumulus itself, being very high, is a serious obstacle to excavating the underlying prehistoric deposits.

Nevertheless, the remains from several buildings have been excavated until now which refer to the three main prehistoric periods identified at the tell: Late Neolithic, Middle and Late Chalcolithic. Three of those, which were two-storey buildings, provide the basic evidence. The presence of so many two-storey buildings at the periphery of the respective settlements enables us to assume that due to the accumulation of wealth from the salt production, the settlement had to be properly defended (especially in the Chalcolithic) which would have been much more successful if the fortification system had been

38

Fig. 36. Provadia-Solnitsata. Northwestern area, a two-storey building: floor boarding between the first and second levels. Beginning of the Late Chalcolithic, 4500-4400 BC

Fig. 37. Provadia-Solnitsata. Northwestern area, a two-storey building: floor boarding between the first and second levels. Beginning of the Late Chalcolithic, 4500-4400 BC

39

Fig. 38. Provadia-Solnitsata. Northwestern area, mandible: foundation offering under the floor of a two-storey building. Beginning of the Late Chalcolithic, 4500-4400 BC

less long, i.e. with mostly two-storey buildings. (No evidence has so far been found on a Neolithic fortification system though its existence could be assumed.) For different reasons all three buildings have been only partly excavated.

The Late Neolithic building (Southeastern area) has already been mentioned. The lower floor was designed for production purposes, i.e. for salt production. The upper one was residential with all the necessary installations and areas for domestic activities.

A considerable amount of ceramic vessels of high quality, complicated shapes and decoration were uncovered in the Middle Chalcolithic house (Southeastern section) thereby implying the high social status of its occupants.

The excavation of the Late Chalcolithic building (Northwestern area) has not yet been finished. A foundation offering was revealed there: a mandible of an adult female under the base of the western wall (the jaw was apparently taken out of the grave for that purpose). The board flooring preserved in the second-storey floor is of special interest; it provides rich information on the high level of engineering knowledge possessed by the builders of the time.

Judging by the excavations at the Southeastern gate of the Middle Chalcolithic fortification, it can be assumed that a paved street began from the gate inwards having a width of 2 m. It is clear that the settlements of that period were well organized but there is no more evidence available.

Ritual facilities and ritual sitesRituals are an immanent part of ancient culture. Traces of it can be found both within and

outside the settlements. Despite the small area excavated, several ritual facilities on the tell have been revealed.

40

Fig. 39. Provadia-Solnitsata. Northwestern area, ritual feature. Late Neolithic 1, 5500-5200 BC

Late Neolithic pit with deer antlers in the Northwestern area. Four deer antlers have been discovered above the ruins of a Late Neolithic building arranged in an almost V-shaped pattern in two pairs. The antlers were apparently laid deliberately in this way. They enclose a space of 1.50 x 1 m. Several medium-sized stones, a bone ‘chisel’ and two clay alters’ fragments were placed between them

41

Fig. 40. Provadia-Solnitsata. Southeastern area, ritual pit. Late Neolithic 1 (5500-5200 BC).

on the yellow clay layer. Due to the small dimensions of the trench, there is no other information available for this context. However, there is no doubt that feature is the result of a ritual though its meaning remains unclear. In any case the deer antlers were associated with high male potency and fecundating power during prehistory.

Late Neolithic ritual pit in the Southeastern section. It has been partly excavated in a cultural layer and primarily in virgin soil. It is approx. 2 m deep, slightly keg-shaped. Its dimensions in the upper part are 1.35 x 1.20 m; it is widening a little in the middle and is constricting again at the bottom.

An irregular hole has been identified in the central part of the pit’s bottom. It is filled up with small and medium-sized stones among which 12 pieces of grinding stones have been found. These stones are covered by the lowest layer of the pit’s fill: 10-15 cm thick, yellowish-green clay with some pottery sherds (mainly of a thick-walled storage jar) and charcoals that had was obviously been piled up soon after the grinding stones’ ritual.

A dark-gray, comparatively dense layer, 5-10 cm thick, with a large amount of pottery sherds, mainly from brine evaporation bowls, as well as charcoals follows in the pit’s fill overlaid by a charcoal layer with a thickness of 1-1.5 cm which is in turn covered by another dark-gray layer, approx. 15 cm thick, that contains charcoals and a large number of pottery sherds, mainly from brine evaporation bowls. Remains of unburned wood were found in several places in that layer.

A 5-10 cm thick layer follows which contains mainly pottery sherds from brine evaporation vessels, some dark brown sediment and charcoals. An intact bone awl was uncovered in it as well as a small animal’s phalange, an animal femur, a ceramic vessel’s base, a rim sherd of carinated bowl, a rim sherd of biconical bowl, a jug sherd with part of a handle, a ‘mushroom’ handle, three articulated animal vertebrae lying next the pit’s wall.

42

Fig. 41. Provadia-Solnitsata. Northwestern area, burial 3. Late Chalcolithic, 4500-4200 BC

This layer is sealed with yellowish-green clay of 4 cm thickness. A broken cattle bone has been uncovered at each of the four pit’s edges (northern, eastern, southern and western); all of the bones are placed with their epiphysis pointing west and plastered in the yellowish-green clay. A rim sherd of a jug, an intact bone awl and an antler fragment are also plastered in the same clay layer.

Another dark-gray fairly dense layer follows, with a very large quantity of ceramic sherds and charcoals having a thickness of about 5 cm. Large pieces of burnt daub are arranged upon that layer and partly within it, along the periphery of the ritual pit, coming from the debris of a building or some installation since on most of them one can distinguish the wattle imprints. All of these were ‘plastered’ in the pit walls with yellow sterile clay. Thus a free space was formed in the central zone of the pit. Dark-gray ash with charcoals was piled up in it forming a 10-15 cm thick deposit. The ash was covered with highly powdered daubs which subsequently formed a dense deposit. А massive stone axe was placed upon it in the central part of the pit whose backside was broken before it was placed there.

The next layer of the pit’s fill is 20 cm thick and contains dark-gray loose sediment with charcoals and pottery sherds, mostly from brine evaporation bowls. An antler fragment has been found by the western wall and a perforated Black Sea shell by the southern one. Six stones have been uncovered in the lower part of that deposit, four of which being grinding stone fragments.

Overlying that deposit is a grayish-black gravel deposit with charcoals having a thickness of 52 cm. Medium-sized stones have been uncovered at the bottom of the deposit in the southern and central part of the pit, five of which being grinding stone fragments. They are placed in such a way that they form a stripe oriented SE-NW. West of these the deposit is saturated with a large amount of pottery sherds from brine evaporation bowls. One piece of burnt daub has been found in the southern and western parts of the pit each. An intact bone awl has also been revealed. One large fragment of grinding stones has been uncovered in the western and eastern parts of the feature each.

43

The next layer is 44 cm thick and consists of grayish-white ash and charcoals. Four quarried rocks have been found in the upper part of that layer arranged in an arc along the wall.

The uppermost 20 cm layer of the fill is comparatively dense reddish-yellow sediment consisting of ‘pulverized’ debris from a building or some clay installation with which the ritual pit was finally capped. A small leg of a female anthropomorphic figure was uncovered in that layer.

As has already been discussed, the pit was filled up as a result of about twelve individual ritual actions. Probably before each one the pit was prepared for the new offering: it was cleaned, the bottom was leveled and sometimes plastered. The content of the layers is the usual one for the Late Neolithic rituals including grinding stones, bone tools, pottery, burnt daubs from houses and

Fig. 42. Provadia-Solnitsata. Marble bead from burial 3. Late Chalcolithic, 4500-4200 BC

domestic installations. The presence of a large amount of sherds from brine evaporation bowls implies that for this activity support was also sought through rituals.

Late Chalcolithic burial. It was discovered in the western periphery of the tell, between the second and the third defense walls. The skeleton shows some peculiarities in the manner of burying the deceased woman. She was buried lying prone, with the head to the north. The left arm is bent at the elbow along the body, its lower part lying under the ribs. The right arm was probably also bent along the body. The legs are bent at the knees strongly backwards; the shank of the right leg is located left of the thigh whereas the shank of the right leg lies right of the thigh, i.e. the heels are located one next to the other between the two thighs immediately under the pelvic bone while the phalanges dropped under it (the ankles were apparently tied to the upper part of the thighs). No grave goods have been found except for a marble disc bead located the pelvic bone. Such a manner of burial, 2-3 m in front of the fortification wall (or in front of the assumed Western gate?) is unusual and has not found proper explanation. Moreover, the buried adult woman (25-30 years old) died of a blow with a heavy sharp object between the eyes (sacrifice?).

Late Chalcolithic ritual sites outside the tell. They present two main aspects of the ritual activity during the last period of the ‘golden’ millennium.

A ritual pit site has been found about 60 m west-northwest of the tell. Its area is at least 20 ares. Part of the large feature including the bottoms of 30 ritual pits has been excavated in a trench covering an area of approx. 60 sq m. The pits’ bottoms are outlined in the virgin soil at a depth of about 2 m. A 1.20-1.40 m thick gray deposit (with two sublayers) overlying them has been identified which contains more or less charcoals, pebbles, sherds of thick-walled and less thin-walled ceramic vessels, animal bones, flint artifacts. As in other similar cases, the outlines of the ritual pits in that deposit cannot be distinguished. The distinction can be made only at the level of the yellow virgin clay. A characteristic feature of the site is the frequent intersection between the pits though none of them is disturbed by its eastern half. That presupposes site development from the east to the other directions, especially to the west, which is reasonable bearing in mind that the settlement is located east-southeast of the ritual site. The fill in the upper part of the pits is identical with the lower sublayer from the abovementioned deposit overlying the virgin soil.

The oval pits predominate followed by round ones but there are irregular ones as well. Three of the pits have one ‘step’ each in their northern parts. The dimensions vary considerably: the oval and irregular pits have diameters of 40 x 90 cm to 1.5 x 2.0 m; a pit with a length of 3.50 m and a width of

44

Fig. 43. Provadia-Solnitsata. Pit sanctuary. Late Chalcolithic, 4500-4200 BC

more than 1.0 m has been partially excavated. The depth of the pits ranges from 10 to 90 cm. However, two concentration ranges can be observed: nine pits with a depth of 20-30 cm and six other pits with a depth of 40-50 cm. The walls of the pits are steep or vertical and rarely sloping or concave. Their bottoms are level. In one case coating with 1cm thick gray clay has been identified.

The differences in the pits’ fill enable us to distinguish three groups:In the biggest group, the fill is grayish-brown loose sediment with admixtures of small charcoals;

in the lower part towards the bottom the sediment smoothly lightens in color with the occurrence of inclusions of greenish clay similar to the virgin soil and its density increases. The concentration of pottery sherds is low to medium, rarely high, additionally decreasing in depth. The animal bones are few. Of particular interest are pit 15 – fragments of an oven base lie on its bottom, having been transported from elsewhere – and pit 23, at the bottom of which an accumulation of stones, pottery sherds and bones has been uncovered.

The second group includes several pits in which the fill is grayish-brown loose sediment only at the level of the virgin soil whereas the rest of the feature is filled up with dense grayish-green clayey earth variegated with small charcoals. There are a small number of pottery sherds only in the uppermost layer of the fill while downward there are single pieces.

In the first two groups, despite the existing differences, the fill is comparatively homogeneous.The third group involves several pits in whose fill separate levels can be identified. As a rule

the concentration of pottery sherds in them is high, rarely low to medium. Those are the pits with the richest material. Pit 12 gives an idea of several-layered fill: on top there is 10 cm of grayish-brown loose sediment followed by a level of 5-10 cm of burnt beaten clay overlain by multiple pottery sherds followed downward by 40 cm of grayish-brown loose sediment with many charcoals in it and several medium-sized and large stones; downwards the earth lightens in color (grayish-green) mixed with sterile clay;

45

Fig. 44. Provadia-Solnitsata. Ritual pit 1: offering of ceramic bowls. Late Chalcolithic, 4500-4200 BC

Fig. 45. Provadia-Solnitsata. Ritual pit 1: a bowl. Late Chalcolithic, 4500-4200 BC

Fig. 46. Provadia-Solnitsata. Ritual pit 1: a bowl. Late Chalcolithic, 4500-4200 BC

there are pieces of sterile clay probably fallen off the walls, i.e. the pit stayed open and was periodically filled up. A sealing of greenish clay has been identified in pit 19 (up to 4 cm thick), a level of pottery sherds in grayish-brown earth and 1 cm thick gray clay coating on the bottom and walls; two parts of the same female figure were also uncovered in it. A level of 10 cm thick pure greenish clay has been cleaned under the fill in the upper part of pit 22 (grayish-brown earth) which covers its entire area; under that level several large pottery sherds and two medium-sized stones were unearthed in a thin deposit of grayish-brown earth at the pit bottom. A small portion of pit 29 has been investigated (a length of 3.50 m and a width of 0.95 m) on the bottom of whose northern part stone accumulation was uncovered measuring

46

0.50 x 1.0 m and a height of approx. 0.85 m, the stone being with different sizes arranged in 4-6 rows; the pit’s fill is in layers; the concentration of pottery fragments is low.

It is generally assumed that the rituals in the so-called pit sanctuaries are associated with the fertility of the Mother Goddess in all her aspects. The Neolithic pit sanctuaries were usually located by a high water spring. In this particular case, although referring to the Late Chalcolithic, the situation is similar: a sweet-water spring gushes forth 70-80 m southwest of the ritual site.

A ritual pit site within the Chalcolithic production site. The practice of specialized salt production at Provadia-Solnitsata must have had its influence on rituals which is very similar in the vast area of early farming cultures in the Eastern

Fig. 47. Provadia-Solnitsata. Ritual pit 1: a bowl from the burial. Late Chalcolithic, 4500-4200 BC

Mediterranean. Since sacred and profane were inseparable concepts in the minds and lives of the early farmers, the long practice of another specialized production activity was undoubtedly reflected in the cult because they wished that salt production should succeed as well.

The following ritual facilities have been identified on the territory of the Chalcolithic production site but do not disturb the production installations, which means that they had been made either during the operation of that part of the site or immediately after the end of the production activity there. The ritual facilities are located in an area of about 350 sq m, at a short distance from each other; this is probably only part of the ritual site. All features date to the Late Chalcolithic (4500-4200 BC).

A large pit (No. 1) has been found in the central part of the Chalcolithic production site whose excavations has yielded interesting results and gives food for thought. In fact, the pits are two, one dug into the other at a certain time interval, the later one considerably disturbing the fill of the earlier one.

The later pit is 1.70 m deep. Its diameter in its upper part is approx. 2 m. Two layers can be clearly distinguished in the fill. The upper one consists of brown sediment with a relatively low concentration of pottery, animal bones and small pieces of burnt daub. The pottery sherds are mainly from brine evaporation tubs. Two intact ceramic vessels were unearthed in it which were placed one next to the other with their mouths downward and the bottoms upward, respectively. Their position shows clearly that they were deliberately placed in that way and not thrown away. The lower layer has a very high concentration of burnt daubs and sherds of salt evaporation vessels.

Remains of the fill of an earlier pit have been found but its main part was scraped during the excavation of the later pit in the same place. Three long bones of human lower limbs were uncovered at a depth of 85 cm from the surface near the eastern wall as well as several human skull fragments. Two of the long bones were articulated at the knee joint and bent at an angle of 60 degrees. The bones belong to a 20-30 year-old man3 who was buried in the earlier pit in a flexed position on the right side with the head to the west. An intact vessel laid on its bottom has been found in the same pit and at the same level with the bones.

This situation raises important questions about the ancient rituals. The earlier pit is a Late Chalcolithic grave disturbed by the later pit. However, there are no indications for the existence of a cemetery in the uncovered area of the Chalcolithic production site. Therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility that this was not a regular burial but an inhumation associated with other reasons and circumstances. It is very likely that the later pit was also related to certain ritual activities. Although the overall nature of the fill does not allow more concrete conclusions to be made in this respect, the 3 The human bone material from Provadia-Solnitsata has been assessed by Kathleen McSweeney of the University of Edinburgh. I would like to thank her for the preliminary information about the sex and age of death of the deceased.

48

Fig. 49. Provadia-Solnitsata. Stone axe from burial 2. Late Chalcolithic, 4500-4200 BC

position of the two intact vessels in the pit with their mouths facing downward shows clearly that they were deliberately placed in that way, with a specific purpose, which definitely was not associated with their functional use as vessels.

Another burial (No. 2) has been discovered near the ritual pit presented above. The oval grave pit measures 1.20 x 0.65 m, its depth being 0.40 m. The skeleton is well preserved. The body of the adult man was buried in a flexed position on the left side with the head to the southwest. The upper half of the body was in a supine position with a slight incline to the left. The right arm was bent at the elbow at an acute angle, with a hand in front of the face whereas the left arm was extended downward and bent at the abdomen. The legs were bent in a parallel position. A stone hammer-axe with a wooden handle was put in the right hand of the dead man as a sign of high social status.

Why was a man of high social status buried individually within the boundaries of the salt production site? Maybe he had some leading position in the salt production? It is beyond doubt, however, that his burial outside the cemetery of the settlement was not accidental. He obviously held a higher position in society.

Immediately south of the grave, a second ritual pit has been found which unfortunately had been disturbed by a recent excavation. Only the lowest 25 cm of fill have been preserved though it was at least 1.70 m deep. It is oval in shape measuring 1.08 x 0.85 m. The walls or at least their lowest part dug in the virgin soil, were clay coated. The preserved bottom part was filled up with sherds of thick-walled brine evaporation tubs and some brown sediment admixed with charcoals. On the basis of the sherds, a big brine evaporation tub has been reconstructed graphically that was probably broken in the pit.

The third ritual pit has an irregular ellipsoid shape measuring 4.30 x 3.20 m in its upper part and having a depth of approx. 1.50 m. The walls extend smoothly downwards and inwards. The bottom is level. A hole, 20 cm deep, has been revealed in its central part in which a stone was placed. The ritual pit is almost tightly filled up with small and medium-sized quarried rocks; their number decreases towards the bottom and the periphery. Separate layers can also be identified, i.e. the pit was filled up by multiple activities. The sediment between the rocks is loose and ash gray in color. An intact, well preserved copper

51

Fig. 52. Provadia-Solnitsata. Ritual pit 3: copper axe. Late Chalcolithic, 4500-4200 BC

Fig. 53. Provadia-Solnitsata. Ritual pit 3: copper axe. Late Chalcolithic, 4500-4200 BC

52

Fig. 54. Provadia-Solnitsata. Chalcolithic production site. A ritual facility with an approximately square outlines. Late Chalcolithic, 4500-4200 BC

shaft-hole axe of the so-called Pločnik type has been uncovered in the western periphery of the pit near its wall at a depth of about 70 cm; there are remains of a wooden shaft in the hole. At almost the same depth amidst the rocks but in the central part of the pit, bones of an adult woman have been found: a long bone and rib fragments as well as the mandible without teeth. A stone pounder with rounded edges has been uncovered near the copper axe. A large amount of sherds from thick-walled brine evaporation tubs as well as a small amount of thin-walled sherds has been revealed among the rocks.

The ritual pit is impressive for the offering which probably could be interpreted as a secondary burial: the human bones were taken out of a grave of a woman with a high social status and reburied within certain ritual context, perhaps in seeking for the help of the deceased soul for a favorable outcome to a critical situation. The copper axe was probably also taken out of a grave, but a grave of a man with a very high social status, and was placed in the pit. The ritual pit is located within the boundaries of the Chalcolithic production site: both ancestors – a woman and a man – whose graves were opened, most likely had performed important functions in their lives and had considerable contribution to the organization of the salt production.

The fourth excavated ritual pit has dimensions of 1.20 x 0.80 m; it is comparatively shallow (25-30 cm) and filled up with sherds of thick-walled brine evaporation tubs as well as of thin-walled vessels. Among the latter is an intact ornithomorphic bowl (that bowl type was used in salt production). A sealing of a thin clay layer has been identified in the middle zone of the fill.

Two installations have also been excavated which are outlined with small stones on the surface of the production site’s layer. They were rectangular in shape measuring approx. 3 x 4 m and oriented NNE-SSW. They are spaced 20 m from each other within the area of the ritual facilities described and their long axes lie on one line. Since they were badly disturbed by later activities, their function remains unclear but was not related to salt production.

54

Fig. 56. Provadia-Solnitsata. The cemetery: detail of burial 5. Late Chalcolithic, 4500-4200 BC

Fig. 57. Provadia-Solnitsata. The cemetery: detail of burial 6. Late Chalcolithic, 4500-4200 BC

55

The bones of two adults, a man and a woman, have been unearthed immediately to the east of the described ritual ground. They probably originated from a ritual pit which has not been excavated yet.

Therefore, both Late Chalcolithic extramural ritual sites are located almost symmetrically in relation to the tell settlement. Traditional rituals were practiced in the first one northwest of the tell that are known to had existed in this form at least since the Late Neolithic in the Eastern Balkans. With a certain risk (only a small part of the site has been excavated), they can be defined as ‘farming’ rituals. The second site, northeast of the settlement, demonstrates nontraditional rituals which represent a combination of various elements: ritual pits, burials and stone features. Moreover, the fill of the ritual pits suggests various ritual variants of a new type. I would associate the second ritual site with the new specialized activity for the early farming society, separated from the traditional economic pattern: salt production.

The Chalcolithic cemeteryThe cemetery of the settlement of Provadia-Solnitsata was identified by a trench excavation.

The graves excavated so far refer only to the Late Chalcolithic which means that maybe only one of the cemeteries has actually been uncovered. This will be clarified during the next seasons. The burial ground is located about 250 m southwest of the tell. Three graves have been excavated in its eastern periphery and pieces of grave goods have been found in its western periphery; the lack of skeletal remains in the latter case is perhaps an indication of finding a cenotaph.

The first three burials (Nos. 4, 5 and 6) are flexed inhumations on the right side with the head to the north. Burial 4 belongs to an adult woman. The grave goods consist of a comparatively long flint blade, a bone awl and a rounded stone. Both other burials belong to adult men. The grave goods of burial 5 consist of two small decorated tiered pots, one of which the deceased individual held in both hands in front of his face. The grave goods of burial 6 include two small tiered pots as well as three small carinated bowls and a small copper axe. Judging by the damages in their skulls, both men in burials 5 and 6 died a violent death. Two large copper earrings come from burial 7, in the western periphery of the cemetery.

The limited excavation carried out until now suggest that the Late Chalcolithic cemetery will provide exhaustive evidence about the life in the settlement and the early complex society in the area as well as the trade contacts of the saltmakers.

Provadia-Solnitsata, Varna Chalcolithic cemetery and the long distance tradeExchange of material valuables, that is also exchange of ideas often defined as influences, is

an inseparable part of the life of ancient societies. In fact, the need for exchange is the reason for the appearance of relations and contacts. Revealing those important problems using only archaeological evidence is a very complicated task. Especially if we bear in mind the fact that it is inorganic materials that have mostly been preserved from the prehistory thus distorting the picture. On the other hand, there has been no evidence on the existence of wheel transport (carts) so that the possibilities for exchange of heavy items and raw materials at long distances were quite limited; we should take into account the standard for load on a carrier in the trade expeditions which during the time of the ancient Mesopotamian states was about 30 kg. The capacities of the participants in the prehistoric caravans could not have been bigger than that.

A basis for the appearance and development of exchange is the ecological diversity in the areas of habitation of early farming communities and mainly the availability of raw materials necessary for the people but rarely found. On that basis a production intended for exchange could have started. Exchange and trade were not carried out with accidental surplus of some products; this was a specialized activity in which purposefully manufactured products were realized. A clear example of that is the salt production by brine evaporation. Those who lived near the salt springs satisfied all their needs with brine whereas the salt production was always trade-oriented. Salt in particular played a special role in prehistoric trade in which it had a double function. On the one hand, salt is a product for use and part of the

56

Fig. 58. Varna cemetery. Gold insignia. Late Chalcolithic, 4500-4200 BC

Fig. 59. Varna cemetery. Gold amulets. Late Chalcolithic, 4500-4200 BC

salt produced was ‘bought’ for that purpose. On the other hand, salt played the role of a general equivalent, of money, and once it entered the market, it could circulate in that other capacity before being consumed. A similar case is known in history when Indian black pepper for some time ‘overshadowed’ gold.

All sort of products were included in the exchange and trade networks throughout the Neolithic and Chalcolithic which were estimated by other people or communities as necessary. They are very often items subsequently used in a new context as signs of prestige. Examples of those items are bracelets and other ‘ornaments’ from the Mediterranean Spondylus and Glycymeris shells which appeared in Neolithic and Chalcolithic settlements, cemeteries and pit sanctuaries in Bulgaria. This also applies to the shells of several other Mediterranean mollusks. Some dark- or polychrome painted ceramic vessels from the Early Neolithic in the Central Balkans were exchanged in Thrace where they also served as a sign of prestige. Many more examples can be

57

Fig. 60. Salt deposits in Europe. The Mirovo salt deposit is the only one south of the Lower Danube which was a basic precondition for the important role of the salt production site of Provadia-Solnitsata in the prehistory of SE Europe

provided but no information on the character of exchange and its context can practically be extracted.A good example of successful exchange is the exceptionally rich grave inventory in the ‘golden’

Varna Chalcolithic cemetery which is located about 40 km from Provadia-Solnitsata and was left by the same ethnocultural community.

There must have been good reasons for the appearance of such an unusual cemetery of the time including a considerable number of burials with a high concentration of grave goods of varied types and materials as well as the occurrence of that cemetery near the Varna Lake.

Two theoretical possibilities exist for the accumulation of prestigious items in the Varna Lake area during the Late Chalcolithic: a) availability of various local raw materials or import of raw materials for their local production, or b) import of produced artifacts regardless of the local production type. However, we should bear in mind that one of the prerequisites for an artifact to bestow prestige to its owner is that it – or the material it is made of – should be of a distant ‘foreign’ origin.

Some of the grave goods are apparently local and made of local raw materials. These are the ceramic vessels, bone and antler artifacts, some of the ground and chipped stone tools. For the other items, areas of origin more or less distant from the Varna Lake can be assumed.

Chipped stone tools. Part of them resulted from specialized production carried out by professionals in the Razgrad area about 100 km northwest of the Varna Lake.

Ground stone tools from volcanic rocks (basalt, andesite, gabbros). The nearest deposits from which those tools could be made are located south of Burgas and primarily in the Strandzha Mountains.

Obsidian blade. Based on the physicochemical analysis, it originates from the Melos Island in the southern part of the Aegean.

58

Chalcedony (carnelian and agate) beads. The raw material for them probably came mainly from Anatolia though certain pieces may be associated with the Eastern Rhodope Mountains.

Artifacts (‘ornaments’) made of mollusk shells (Spondylus, Glycemeris and Dentalium). The raw material originated from the Aegean Sea along the northern coast of which the prestigious items were probably manufactured.

Copper tools and ‘ornaments’. The ready metal ingots were imported to the Varna Lake area from a greater distance. The lead-isotope analyses made of most copper artifacts from the Varna cemetery show a comparatively clear polycentric picture of the metal sources. The raw material came predominantly from the West Pontic copper ore area (the northeastern parts of the Standzha Mountains, approx. 120-150 km away) and less from the East Thracian copper ore area (the eastern parts of the Sredna Gora Mountains, about 250-270 km away); small amounts come from other deposits, probably in West Bulgaria (400-500 km away).

Gold artifacts. The question of the origin of gold remains largely open. Two types of gold have been identified: in the first one (BP) there is some admixture of platinum and in the second one (B) there is none. The origin of the BP type raw material is sought in Northeast Anatolia or Caucasus and of type B to the south of the Balkan Range, most likely in the Standzha Mountains. I would include the Sakar Mountains and the Eastern Rhodope as a possible region of origin of the second type.