Public space and public protest in Kuwait, 1938–2012

Transcript of Public space and public protest in Kuwait, 1938–2012

Public space and public protestin Kuwait, 1938–2012Farah al-Nakib

Events across the globe in 2011, from the Occupy movements to the Arab uprisings, havemade salient Henri Lefebvre’s assertion that ‘the city and the urban sphere are . . . thesetting of struggle; they are also, however, the stakes of that struggle’ (Lefebvre, H. 1991.The Production of Space. Oxford: Blackwell, 386). This paper analyzes the city as boththe site and stake of political contestation between state and society in Kuwait, and therelationship between contentious politics and city formation after the advent of oil. Specifi-cally, it traces the spatiality of public protest from the 1930s until today alongside the chan-ging social composition of opposition forces. During each new period of contestation, boththe government and opposition adopted new spatial tactics that left their mark on theurban landscape. The paper focuses on the role of particular public spaces like the historicSahat al-Safat and the newer Sahat al-Irada, and semi-private spaces like diwawın andcivil society organizations, in giving form to the discursive public sphere.

Key words: Henri Lefebvre, Kuwait, political opposition, Arab nationalism, Sahat al-Safat,Sahat al-Irada, dıwaniyya, civil society

Introduction

In The Production of Space, HenriLefebvre (1991) argues that:

‘the city and the urban sphere are [ . . . ] thesetting of struggle; they are also, however, thestakes of that struggle. How could one aim forpower without reaching for the places wherepower resides, without planning to occupythat space and to create a new politicalmorphology?’(386)

Recent events across the globe, from theOccupy movements to the 2011 Arab upris-ings, have made Lefebvre’s idea of urban con-testation widely relevant. Yet despiteBahrain’s experiences in 2011, Gulf citiesrarely feature in the growing literature onurban contestation in the Arab world. Theyare more commonly viewed as ‘glittering

global consumer utopia[s]’ (Kanna 2011) thanplaces of political struggle. Scholarly discourseconstructs Gulf cities as highly controlledspaces housing highly controlled citizenswho were bought out of decision-makingby the oil ruling bargain, trading politicalrights for extensive welfare goods and ser-vices. In this narrative, citizens and residentsplay no role in shaping their city; urbaniz-ation is the purview of the rulers and capital-ist elites. Kuwait, however, defies this imageof Gulf cities, as opposition to the govern-ment has historically held a prominentplace on the country’s political and urbanlandscapes. This paper analyzes KuwaitCity as a site and stake of political strugglebetween 1938 and 2012, and examines therelationship between political contestationand city formation after oil.

# 2014 Taylor & Francis

CITY, 2014VOL. 18, NO. 6, 723–734, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2014.962886

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Fara

h A

l-N

akib

] at

08:

16 0

7 D

ecem

ber

2014

Before the launch of the oil industry in1946, Kuwait Town had developed throughcenturies of unplanned growth that reflectedthe town’s mercantile and maritime func-tions. Aside from the ruler’s palace, therewere minimal markers of government onthe landscape until the first state buildingswere constructed in the 1940s. The stateinitiated a new master plan in 1952 to turnthe old port town into a modern city. Towns-people were moved en masse to new suburbsoutside the town wall, while the city centerwas redeveloped into an economic and politi-cal center. In an attempt to maintain controlover urban development and to project thecity to global audiences as a symbol ofKuwait’s prosperity, the government triedto depoliticize the center by removing thesites of everyday political life, or relocatingthem beyond the city limits.

These attempts at controlling both the cityand politics have not gone uncontested.Kuwait historically enjoys the highest levelsof political freedom and participation in theGulf, and its urban landscape has at leastpartly been shaped by ongoing political con-testations between the rulers and differentopposition groups. Before oil, political lifewas relatively stable, characterized by abalance of power between the rulers and thepeople, and interrupted by few, usually briefperiods of crisis. The discovery of oil in 1938disrupted this equilibrium, and from thatpoint onward, political contestation becamethe norm. Over the following decades, thesocial composition of opposition forces varieddepending on the prevailing economic, politicaland regional context. The city frequently servedas both site and stake of contestation betweenthe government and opposition groups, andboth sides adopted spatial tactics that left theirmark on the urban landscape.

Sahat al-Safat and pre-oil urbancontestation

Kuwait Town was settled in 1716 by a groupof tribes from central Arabia. Over the

ensuing two centuries, the small settlementgrew into a prosperous mercantile and mari-time town integrated into the westernIndian Ocean trading networks. Accordingto local tradition, Sabah I was selected bytown notables in 1752 as Kuwait’s firstruler, charged with maintaining security,settling disputes and administering justice.In exchange, the merchants provided himwith financial support. The rulers were thusaccountable to the merchants, who wereclosely involved in decision-making. Thisdivision of labor seems to have sustained arelatively high level of political stabilitybefore oil. British Political Resident LewisPelly (1865) reported that in Kuwait Town,‘there seems indeed to be little Governmentinterference of any kind, and little need forany’ (10). A French traveler describedKuwaitis in 1884 as ‘one of the freestpeoples in the world’ (Tetreault 2000, 34).

The political dominance of the merchantstranslated itself in the dıwaniyya, the town’sprincipal space of political discussion anddebate. The dıwaniyya was a space in afamily’s house used for male visitors, andwas spatially distinct from the household(the harem). In the evening, men of thelocal neighborhood would call on theirfriends and associates in local diwawın(plural of dıwaniyya) to socialize, exchangenews and views, talk politics and makebusiness deals. Smaller houses were not bigenough to have diwawın, which were morecommon among the elite. Though attachedto a private home, social custom dictatedthat nobody could be turned away; thedıwaniyya thus straddled the line betweenpublic and private realms. Members of theruling family often attended prominentdiwawın, where men spoke frankly abouttheir political opinions, misgivings andgrievances.

While the dıwaniyya remained the purviewof the elite, the market (suq) was the mainurban space giving form to the discursivepublic sphere to which everybody hadaccess, including women. It was the centerof everyday life, the place where one could

724 CITY VOL. 18, NO. 6

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Fara

h A

l-N

akib

] at

08:

16 0

7 D

ecem

ber

2014

hear the news of the town and the world, andwhere public opinion was formed andexpressed. In 1932, a young Kuwaiti national-ist took offence to something Americanmissionaries said during a daily service attheir hospital. He went ‘up and down thebazaar, telling the town that the missionarieswere profaning the religion of Islam and blas-pheming the Prophet’ (Arabian Mission 1932,12). In addition to the news and views thatspread from shop to shop, particular placeswithin the market also stimulated politicaldiscussion. This ‘architecture of sociability’(Tonkiss 2005, 68) included the AhliyyaLibrary and the missionaries’ Bible shop,both of which became ‘casual meeting[places] of the hot-headed anti-Subah [sic]youths of Kuwait’ in the 1930s (Crystal 1995,59; Kuwait Intelligence Summary 1940, 153).It also included the offices of the merchants’market (Suq al-Tujjar), where the elitecollected donations for such services as theMubarakiyya School, which opened in 1911in the market and became the breeding

ground of many interwar opposition leaders.In these places townspeople were free todiscuss, debate and contest the social andpolitical issues of the day. Missionariesreported that they enjoyed ‘absolute freedomof speech’ in their Bible shop, where peoplecould ‘say anything they like’ (Chamberlain1917, 16).

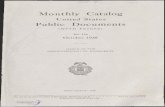

The town’s main public square, the Sahatal-Safat, was at the landward end of themarket (Figure 1). Al-Safat was the site ofthe open-air Bedouin market, which towns-people visited regularly to buy suppliesfrom the desert. Al-Safat was the only spacethat townspeople and tribes shared, andwhere both communities freely interacted.During public festivities, ‘rich and poor, alldressed in new clothes for the occasion,would flock to the main town square’ of al-Safat (Lewcock and Freeth 1978, 7). Thesquare was what Fran Tonkiss (2005) calls apublic site of collective belonging, whichaffords ‘equal and in principle free access toall users as citizens’ (67).

Figure 1 The everyday life of Sahat al-Safat in the late 1930s (Source: Kuwait Oil Company Archives)

AL-NAKIB: PUBLIC SPACE AND PUBLIC PROTEST IN KUWAIT, 1938–2012 725

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Fara

h A

l-N

akib

] at

08:

16 0

7 D

ecem

ber

2014

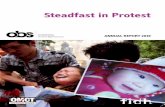

Oil threatened these common rights.In 1934, the ruler, Ahmed al-Jaber, signeda concession agreement with the Anglo-American Kuwait Oil Company. Oilincome went directly into his hands, makinghim independent from the merchants anddecreasing their access to decision-making.During the 1930s, the palace guard (feda-wiyya) regularly performed a Bedouin wardance (or ‘ardha) in al-Safat, as a way of ral-lying public support for the ruler and demon-strating the ruler’s growing power andauthority (Figure 2). When Ahmed al-Jaberwas made Knights Commander of theOrder of the Star of India in 1944, the rulerand his entourage made their way to al-Safat, where ‘an impressive war-dance was

performed’. The day was declared a publicholiday and the entire population saw ‘theirRuler wearing the decorations conferred onhim by his friend and ally, the British govern-ment’ (Dickson 1971, 171).

This changing balance of power promptedKuwait’s first serious opposition movementin 1938, the year oil was discovered in com-mercial quantities. The merchants com-plained that Ahmed was not using hisroyalties for public services. Realizing thatoil ‘would deprive them of their critical rolein providing revenue, and with that costthem their power’ (Crystal 1995, 55), theleading merchants petitioned the ruler toform an elected council, and Ahmedagreed.1 In July 1938, the merchants elected

Figure 2 Dancing the ‘ardha in al-Safat in the late 1930s (Source: Kuwait Oil Company Archives)

726 CITY VOL. 18, NO. 6

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Fara

h A

l-N

akib

] at

08:

16 0

7 D

ecem

ber

2014

a 14-member legislative assembly under thepresidency of Abdullah al-Salem (Ahmed’scousin and nemesis within the rulingfamily). The new council (majlis) demandedbetter government-funded education, apublic hospital and the ‘expenditure of [thecountry’s] revenues on the improvement ofits conditions in every respect’.2 The councilrequested in October 1938 that Ahmedhand over the next oil check to them; he dis-solved the council two months later.3

Symbolic control over the Sahat al-Safatwas at stake in the struggle between the mer-chants and the ruler. The council banneddancing and drumming within the walls ofthe city, a move the Political Agent thoughtwas aimed at the Al-Sabah’s Bedouinwar dances. The council then allowed forradios and gramophones to be played incoffee shops on the square, something theruler had forbidden (Kuwait IntelligenceSummary 1938a, 108, 129). Radios weretuned to Arab nationalist broadcasts fromEgypt, Iraq and London, and played animportant role in stimulating Kuwait’s popu-list movement in the late 1930s. Then, on 10March 1939, Mohammed al-Munayyis—aKuwaiti merchant who had distributed leaf-lets the day before declaring the Al-Sabahdeposed—was arrested, sentenced to deathas a traitor, ‘publicly shot, and subsequentlyhung until evening, in the main [al-Safat]square’.4 On the same day, Ahmed led awar dance in al-Safat; the contest betweenthe reformists and the palace had swung infavor of the ruler.5 By the 1940s, al-Safathad become a symbol of the growing powerof the state, as many new government head-quarters were built there.

Arab nationalism in the 1950s: the city assite and stake of contestation

The last time al-Safat witnessed political con-testation was during the 1950s Arab national-ist movement, when the entire city becamethe site and stake of political struggle. Thesocial composition of this opposition

movement was new, as were their spatialtactics. After Abdullah al-Salem came topower in 1950, he used exponentially increas-ing oil revenues to build state institutions thatwere entirely independent of the people. Atthe same time, unlike his predecessors, hecreated a large welfare state that made thepeople dependent on the government. Theruler also favored the merchants by sanction-ing land-grabbing, facilitating import licensesfor automobiles and consumer goods, andawarding them lucrative government con-tracts. The merchants benefited financiallyfrom development and stayed out of opposi-tional politics to safeguard and enhance theirinterests. They were appointed to high pos-itions in government departments (later min-istries) or committees, and their interestsbecame intrinsically tied to the state.

As the merchants were encouraged to‘relinquish political rights in favor of econ-omic privilege’, the opposition increasinglyshifted toward a new, less affluent intelligen-tsia (Crystal 1995, 82). These men benefitedfrom the country’s improved economic andsocial conditions, and were the first Kuwaitisto receive state scholarships to study abroad.Others had shifted from precarious seafaringoccupations to more settled jobs in the oilindustry or government service. This inter-mediate class had experienced a more drasticshift from their pre-oil conditions than theelite, and pushed for better education andhealthcare, greater social equality and theemancipation of women. They advocatedindependence from Britain, called forgreater freedom and political participation,criticized the extravagance and corruptionof the ruling family, and most threateningto the rulers, were supporters of JamalAbdel Nasser and Arab nationalism.

From the late 1940s onwards, newspapersand civil society organizations emerged as‘new mediated forms of social exchange’ inKuwait that became prominent tools ofopposition (Tonkiss 2005, 67). Technicallyclassified as social or sports clubs, voluntaryassociations were hubs of political activityduring the 1950s nationalist movement (al-

AL-NAKIB: PUBLIC SPACE AND PUBLIC PROTEST IN KUWAIT, 1938–2012 727

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Fara

h A

l-N

akib

] at

08:

16 0

7 D

ecem

ber

2014

haraka al-qawmiyya). Associations like theNational Cultural Club, the Teachers Cluband the Graduates Club attracted varioussocial groups, including the new middle-class intelligentsia, low-wage governmentworkers and foreigners. Their membersdominated national discourse by creatingtheir own publications, writing articles indaily and weekly newspapers and distribut-ing pamphlets. Clubs became the most vocalelements in a public sphere from which,before oil, this intermediate class had beenlargely excluded.

The reduced political role of the merchantclass after oil undermined the status of thedıwaniyya as a spatial counterpart to thepublic sphere. The relocation of the towns-people to new residential areas after 1950also meant that diwawın gradually ceased tobe a feature of the city center. Suburbanizeddiwawın continued to be important spacesof expression and debate, but their role asbases of political participation, organizationand opposition was overshadowed by thenew social clubs, whose headquarters werein the city center. It was in clubs rather thanin diwawın that the ‘young reformist move-ment’ met to discuss social and politicalissues (Kuwait Annual Report 1956).

The nationalist opposition was very muchan urban movement. The reformists believedin boycotts, strikes, demonstrations and theimportance of public places to garner masssupport. The clubs used their central citylocations to their advantage. Representativesfrom different associations would conveneat one of the clubs and then collectivelyventure into the market to collect donationsfor various causes. In September 1956, theclubs raised $27,370 to support the residentsof Gaza (Al-Khatib 2007, 126–128). Thenationalists also used the market to stagedemonstrations, strikes and public speeches.Their activities reached a peak in thesummer and fall of 1956, in response to vola-tile events in Egypt. In August 1956, Nassercalled for a general strike after the nationali-zation of the Suez Canal, and a public dem-onstration was held at the headquarters of

the National Cultural Club. Thousands ofsupporters showed up to hear pro-Nasserspeeches (Al-Khatib 2007, 133; Crystal1995, 81). The security forces raided theclub without warning. Two days later, alarge group of protestors gathered inal-Safat, and ‘a party of some 20 youthsappeared carrying pictures of Nasser’. Onceagain, the security forces intervened and‘laid about the crowd indiscriminately withstaves’ (Kuwait Diary 1956, 172). Twopeople were reportedly killed and severalothers wounded in the clash between demon-strators and fedawiyya, who entered themarket and smashed the windows of theshops and cafes that supported the strike.6

The National Cultural Club was closeddown for two days.

The events of August 1956 revealed to thegovernment how political the clubs hadbecome. The opposition was garneringtremendous public support on the streetamong Kuwaitis and foreigners for an ideol-ogy that threatened the very existence of theruling family. After the tripartite attack onPort Said in 1956, the nationalists planned arally and called for a boycott of Israel,Britain and France. Abdullah al-Mubarak,Head of Public Security, rejected theirrequest and warned the public not to join inany demonstrations. The clubs ignored thewarnings and went ahead, but changedvenue: rather than holding the demonstrationin one of the clubs, which could be raided bythe security forces, they decided to meet atthe market mosque.7 Mosques were ‘pro-tected’ public spaces and free from stateintrusion, though they were never used forpolitical activity before the 1956 nationalistmovement (Tetreault 1993, 278). By appro-priating one of the only public spaces thatthe security forces would not attack, thenationalists were using new spatial tactics toprotect themselves from state interference.Furthermore, the government could closedown the clubs, but not the market. On theday of the protest, the radio warned thepublic not to participate, while army truckswere positioned outside the entrances to the

728 CITY VOL. 18, NO. 6

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Fara

h A

l-N

akib

] at

08:

16 0

7 D

ecem

ber

2014

city. Thousands of protesters still convened atthe mosque to hear speeches and the rallyended without incident (Al-Khatib 2007,146–147).

When Nasser called for a general strike inNovember 1956, the nationalists compelledshopkeepers to close and to follow theboycott. Many businesses cooperated out ofsolidarity and others out of coercion. TheBritish reported that the nationalistsemployed female teachers to patrol themarket and make sure that all shopkeeperscomplied with the action.8 The leading mer-chants, as agents of European products inKuwait, were reluctant to support boycottsthat would undermine their businesses. Itwas the intimidation of thousands of protes-tors convened at the market mosque infront of their offices that compelled the mer-chants to join in the strike (Al-Khatib 2007,146).

‘To avoid incident’, British officials ceasedgoing to the market, and Kuwait OilCompany personnel avoided the city exceptfor urgent business.9 The British believedthe government was doing what it could tomaintain law and order, but they stillthought they would not be sufficiently pro-tected if they entered the city center.10 Mean-while, the government took strongermeasures to prevent political activities. Thiswas undoubtedly a response to the way thenationalists defied police orders and tookcommand of the streets and market. Whenthe creation of a federation of clubs wasannounced in 1957, the government forbadelocal hotels from renting their premises forclub meetings or elections (Kuwait AnnualReport 1957). When news of the 1958 Iraqirevolution reached Kuwait, the head ofpublic security readied the army, the securityforces and the police to preempt civil disobe-dience and public disorder (Persian GulfMonthly Report 1958). Events took a fatalturn during a 1959 rally celebrating the firstanniversary of the union of Egypt and Syriain the United Arab Republic. Oppositionleader Jassem al-Qatami announced, ‘TheKuwaiti people consented to be ruled from

the reign of Sabah I by tribal leadership, andnow the time has come for democratic ruleby the people’ (Al-Khatib 2007, 188–189).The ruler, Abdullah al-Salem, took thesestatements as a personal affront and turnedagainst the political opposition that, faithfulto his support for the 1938 majlis, he hadalways tolerated. He closed social clubsand civil society organizations, suspendednewspapers and other publications, andbanned public protests and demonstrations(Al-Khatib 2007, 190).

It was not until after independence fromBritain in 1961 that the government invitedthe public back into politics, in part becauseof mass public support for Abdullah al-Salem during the Iraqi attempt to annexKuwait in 1961. The Constitution was rati-fied in 1962 and the National Assemblyestablished in 1963. The amir (as the rulerwas now known) was much more cautiousthis time about just how far he would allowthe opposition to go. A new 1962 law con-fined voluntary associations to ‘social andwelfare purposes’ and officially bannedthem from engaging in political or religiousactivity that could endanger the stability ofthe state (Al-Mughni 2001, 37). The newMinistry of Social Affairs and Labor couldlicense and terminate all associations, andprovided them with financial and materialassistance. One form of assistance was theacquisition of new premises, and the ministryrelocated most clubs from the city center tovillas out in the privatized world of the newsuburbs.

After the spaces giving form to the publicsphere (the diwawın and the clubs) movedto the suburbs, the city center ceased to be avenue of political debate and contestation.Although the new National Assembly waslocated in the heart of the city, the stateincreasingly used the legislature as a way tobring in new political groups (tribes in the1970s and Islamists in the 1980s) to balanceout the existing opposition. The governmentalso dissolved the Assembly when it becametoo oppositional, first between 1976 and1981, and again between 1986 and 1992. As

AL-NAKIB: PUBLIC SPACE AND PUBLIC PROTEST IN KUWAIT, 1938–2012 729

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Fara

h A

l-N

akib

] at

08:

16 0

7 D

ecem

ber

2014

a result, most contentious social and politicaldebates took place less in the Assembly thanin the informal spaces of the diwawın andthe clubs, which had been moved to theurban periphery. The state thus safeguardedits control over the city center. Organizedprotests, rallies and demonstrations wereoccasionally permitted, but the venues thathad once given form to the public sphere,such as the market and al-Safat, ceased to beused for social and political purposes. Publicdemonstrations in the city were restricted tospecific areas, mainly the new Flag Squareon the western edge of town. These eventswere closely monitored and controlled bythe Ministry of Interior, and were often orga-nized by the government itself.

After 1973: decentering politics anddepoliticizing the city

After independence and until 2011, the secur-ity forces were no longer deployed within thecity center to curb political protest, becausepoliticized spaces like civil society organiz-ations, the university and the diwawın hadall been suburbanized. After independence,most demonstrations took place outside thecenter, and sometimes included clashesbetween protestors and the police. One suchincident occurred at the university in Febru-ary 1988, when ‘several dozen’ people wereinjured during a demonstration of Kuwaitiand Palestinian students in support of theIntifada (‘Chronology’ 1988, 469).

The suburbanization of voluntary associ-ations did not reduce their ability to revitalizethe public sphere. In fact, the number andvariety of clubs and organizations signifi-cantly increased after independence (Ghabra1991, 200–202). Despite the depoliticizationof the city center, diwawın and civil societyorganizations still served as a form of politicalcommons, which David Harvey (2012)describes as ‘a place for open discussion anddebate over what [ . . . ] power is doing andhow best to oppose its reach’ (161). Aftertheir relocation outside the city center, civil

society organizations became similar todiwawın in that they straddled ‘the public–private divide’ (Tetreault 1993, 279). Bothwere semi-public spaces in the otherwise pri-vatized world of the suburbs; yet both weresemi-private despite being technically opento the public. Membership into voluntaryassociations was based on set criteria thatdivided them along class, occupational, reli-gious or political lines, while diwawınusually attracted visitors that shared thesame social circle, economic class and politi-cal interests of the host. Neither associationsnor diwawın were really sites where peopleof different backgrounds and classes inter-acted freely and worked towards a commonpurpose: a ‘commons’ in the real publicsense. After oil urbanization, political discus-sion and debate lacked the true publiccommons that existed in the city before oil.

It is important to note that clubs anddiwawın differed from one another in oneimportant way. Clubs came under strict gov-ernment control and could be closed downduring crackdowns on public freedoms, aswhen the National Assembly was unconsti-tutionally dissolved in 1976 and 1986(Tetreault 1993, 277). Diwawın, however,were safe from state intrusion thanks totheir location in the inviolable space of thehome. The use of the dıwaniyya as a forumfor political expression and public debatetherefore increased when the governmentcracked down on such conventional forumsas the press and voluntary associations(Ghabra 1991, 205). In 1979, a new Law ofPublic Gathering required gatherings ofmore than 20 people to obtain a policepermit. Diwawın could be held without apermit and therefore served as vital counter-parts to the discursive public sphere, asoccurred in 1989–90 (Tetreault 1993, 279).

By the 1980s, the political opposition wasno longer composed of one single group. Inthe 1950s and 1960s, the nationalists werethe main oppositional group, and the govern-ment sought out new allies to balance themout. Beginning in the late 1960s, tens of thou-sands of Saudi tribesmen were granted

730 CITY VOL. 18, NO. 6

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Fara

h A

l-N

akib

] at

08:

16 0

7 D

ecem

ber

2014

Kuwaiti citizenship to serve as the govern-ment’s principal loyalty base. In the early1980s, the government began courting Isla-mist groups as another way to balance outthe nationalists. Tribes and Islamists domi-nated the 1981 elections, which were thefirst since the 1976 dissolution. However,the government’s attitude toward the Isla-mists changed in 1985 because of securityfears during the Iran–Iraq war, and afterseveral terrorist attacks occurred in the city(including an assassination attempt againstthe ruler). In the 1985 election, the govern-ment backed their old adversaries, thesecular nationalists, who won a majorityover the tribes and the Islamists. However,these three groups unexpectedly alliedagainst the government, leading to anotherunconstitutional dissolution in 1986. By1989, nationalists, Islamists and tribes cametogether in opposition to the ruler’s unconsti-tutional politics.

For seven weeks between December 1989and January 1990, public gatherings were

held every Monday night in the private dıwa-niyya of a different member of the dissolvedassembly to discuss the restoration of the con-stitution and National Assembly. Duringthese Monday diwawın, the opposition andtheir supporters used their peripheral positionin the suburbs to their advantage, and the gath-erings attracted thousands of citizens everyweek. The leaders of the movement (32former MPs from mixed social and politicalbackgrounds, and 13 members of the public)treated these gatherings as private meetings,constitutionally protected from police inter-ference. They avoided using microphones oramplifiers, and upheld the peaceful nature ofthe dıwaniyya (Al-Mubaraki 2008, 39).

The government did all it could to obstructthe movement. During the second Mondaymeeting, on 11 December 1989, the Ministryof Interior closed Mishari al-‘Anjari’sdıwaniyya in Nuzha and security forcesprevented the crowds from reaching thevenue. Public outcry led the Deputy PrimeMinister to publicly apologize to al-‘Anjari.

Figure 3 Al-Safat Square in the early 1950s, after being converted into a traffic circle and parking lot (Source: KuwaitOil Company Archives)

AL-NAKIB: PUBLIC SPACE AND PUBLIC PROTEST IN KUWAIT, 1938–2012 731

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Fara

h A

l-N

akib

] at

08:

16 0

7 D

ecem

ber

2014

He confirmed the sanctity of the dıwaniyyaand guaranteed that the followingMonday gathering would not be disturbed(Al-Mubaraki 2008, 60). However, when themovement spilled out into the traditionallypro-government tribal area of Jahra, theNational Guard and police, equipped withbatons, barbed wire barriers and patrol cars,prevented people from reaching the venue.Yet no dıwaniyya was ever closed again, andthe Monday diwawın movement revealedthat the suburbs, more than the city center,were the primary site of political contestation.

After independence, and particularly afterthe 1973 oil boom, the city center was trans-formed into a heavily guarded ‘landscape ofpower’ (Zukin 1993, 16). New governmentbuildings designed by world-famous archi-tects were constructed on key urban sitesalong or near the seafront (Al-Nakib 2013).In this controlled environment, political con-testation was rare. The one space created forlarge celebrations, Flag Square or Sahatal-‘Alam, was an empty, neutral and control-lable area between the center and the suburbs.Other spaces inside the city, like al-Safat,were transformed beyond recognition. Thearea around al-Safat developed in the 1950sand early 1960s into the central businessdistrict. After a large water tank was built inits center, the square was increasingly usedas a parking lot (Figure 3). In 1982, urbanplanning authorities converted al-Safat intoa modern urban plaza, making it a sunkenspace to deflect the din of the adjacenttraffic. They placed more emphasis on itsvisual qualities than on its public uses.Adorned with trees and a shaded monument,the historic al-Safat became a dead publicspace in the heart of an empty city center.

2011: restoring the urban commons

Al-Safat’s historic role as an urban commonswas virtually revived in the early 2000s,when blogging became a popular mode of pol-itical expression. The blog aggregate websitethat listed all blogs in Kuwait was known as

‘al-Safat’. The historic square thus became an‘electronic agora’, a central if virtual placefor open debate that allowed for free and (inprinciple) equal access to all users (Amin andThrift 2007, 147). Since 2010, however, agrowing opposition movement has workedtoward the restoration of an actual urbancommons. The origins of this movement canbe traced back to May 2005, when the citycenter became a site of political struggle forthe first time since the 1950s. Before a Parlia-mentary vote on a women’s suffrage bill,women’s rights activists (who began cam-paigning for equality with the proliferationof civil society organizations in the 1960s,when they supported, and were supportedby, the nationalists) (Al-Mughni 2001) heldrallies in the seaside park facing the NationalAssembly. Their efforts were successful andthe bill passed with a strong majority. The fol-lowing year, a youth campaign calling for thereduction of voting districts from 25 to 5 helddemonstrations in front of both the Assemblyand the Seif Palace. This return of public pro-tests to the city center was sanctioned thesame year the constitutional court overturnedthe 1979 Law of Public Gathering.

Moreover, when a large political gatheringheld in the suburban dıwaniyya of an opposi-tion leader was broken up by Special Forcesin December 2010, the city once againbecame not only the site, but also the stake,of political struggle. This new oppositionmovement focused on mounting allegationsof financial corruption against the PrimeMinister, Nasser al-Mohammed al-Sabah.Allegations of corruption against governmentofficials and members of the ruling familywere not new, but two factors made the situ-ation more volatile. First, the separation ofthe formerly joint positions of CrownPrince and Prime Minister in 2003 meantthat prime ministers were no longer protectedby the law that criminalizes public criticismof present and future amirs. Second, a 2006press and publications law allowed for theopening of private television stations and anincreased number of private newspapers.Because of this expansion of private media

732 CITY VOL. 18, NO. 6

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Fara

h A

l-N

akib

] at

08:

16 0

7 D

ecem

ber

2014

and the proliferation of blogs and onlinesocial networks, public expression was stron-ger than ever before. The governmentarrested activists for revealing corruptionscandals. In reaction, tribal, Islamist andliberal MPs created the Constitution Bloc todefend constitutional and civil liberties. On8 December 2010, the Bloc held a meetingat a private residence to protest constitutionalviolations. The Special Forces dispersed themeeting, injured several people and arresteda constitutional scholar.

The anti-corruption campaign grew inJanuary 2011, amid uprisings in Tunisia,Egypt and Bahrain. For the first time inmore than 50 years, the opposition plannedmass demonstrations in Sahat al-Safat ratherthan in front of National Assembly. TheMunicipality immediately claimed the plazawas under renovation and boarded it up; itseems the government did not want an occu-pation of al-Safat similar to the occupationsof Cairo’s Tahrir Square and of Manama’sPearl Roundabout. Appropriating al-Safatwould also link the opposition to the 1938majlis and the 1956 Arab nationalists. Thegovernment forced protestors to restricttheir activities to the smaller, historicallyneutral and more easily controllable park infront of the National Assembly, whichbecame popularly known as Sahat al-Irada(Determination Square).

In 2011 and 2012, al-Irada became the offi-cial gathering place of the opposition. Unlikemost previous political movements, thistenuous coalition of Kuwaitis from all class,religious, ideological and political back-grounds required an urban commons. Tohold gatherings at a particular dıwaniyya orassociation would have discouraged the par-ticipation of groups outside of specificsocial circles or political currents. Further-more, Irada was not only used by the opposi-tion; pro-government groups also heldcounter-demonstrations there in 2011 and2012, as did other groups not directly linkedto the current political standoff. Bidun (state-less) rights campaigners held public demon-strations there in 2011, as did women’s

groups demanding equal constitutionalrights in March 2012. Irada became a spacewhere everyone could assemble to expresspolitical views and make demands, reflectinga real political commons (although foreignersare barred from participation in such publicgatherings).

When tensions increased between thegovernment and opposition, protests movedbeyond al-Irada. On the night of 16November 2011, opposition forces stormedand occupied the (empty) National Assemblybuilding. On 21 October 2012, tens ofthousands of demonstrators gathered alongthe Arabian Gulf Road that spans the citycenter in what was dubbed Kuwait’s largestever political demonstration. They were pro-testing the amir’s decree modifying the elec-toral law in the absence of the NationalAssembly. Government forces fired tear gasat the demonstrators, who were given apermit to gather in al-Irada, not to marchacross the city. On 4 November, anotherdemonstration scheduled to take place inthe city relocated to the Mishref residentialneighborhood after government forces cor-doned off the Arabian Gulf Road to preventdemonstrators from reaching the city. In thelead-up to the December 2012 elections,which a large number of Kuwaitis boycotteddue to the aforementioned amiri decree, theKuwait Towers became a prominent site ofrallies and an end point to marches.

The attempted reclamation of al-Safat andthe appropriation of new central spaces likethe Kuwait Towers (the national symbol)reflect a growing public demand for therestoration of a ‘right to the city’ (Lefebvre1996) in Kuwait after half a century of relega-tion to the suburban periphery. Kuwaitappears to be embarking on a new urbanagenda that is shifting away from the prevail-ing Gulf paradigm of spectacular urbanismtowards a more sustainable and democraticfuture. Though there is still a long way togo (including, for instance, the incorporationof non-nationals into this process), Kuwaitisare slowly reclaiming their right to centralityand to shape and use the city according to

AL-NAKIB: PUBLIC SPACE AND PUBLIC PROTEST IN KUWAIT, 1938–2012 733

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Fara

h A

l-N

akib

] at

08:

16 0

7 D

ecem

ber

2014

their own desires, as part and parcel of theirbroader demands for greater equality,democracy and government accountability.

Notes

1 India Office Records, British Library (quoted belowas IO/R): IO/R/15/5/205: Political Agent, Kuwaitto Political Resident, Bushehr, 29 June 1938.

2 ‘A New Movement in Kuwait’, Az Zaman, 3 April1938 (article in Iraqi newspaper translated in IO/R/15/5/205: PA, Kuwait to PR, Bushehr, 24 June1938).

3 IO/R/15/5/206: PA, Kuwait to PR, Bushehr, 22December 1938.

4 IO/R/15/5/206: PA, Kuwait to PR, Bushehr, 12March 1939.

5 IO/R/15/5/206: 12 March 1939.6 Letter from the Council of Clubs to Shaikh Abdullah

al-Salem (Al-Khatib 2007, 134–136); ForeignOffice Records, British Library (quoted below asFO): FO371/120570: Translation of petitionaddressed to High Highness the Ruler of Kuwait bythe Club’s Union, 14 August 1956.

7 FO371/120557: Translation of an appeal to thepeople of Kuwait, 3 November 1956.

8 FO371/120558: Report on situation in Kuwaitprobably by KOC staff (unsigned), 13–20November 1956.

9 FO371/120558: 13–20 November 1956.10 FO371/120588: Extract describing internal

situation in Kuwait, November 1956.

References

Al-Khatib, A. 2007. Al-Kuwait: Min al-Imara ila-l-Dawla,Zhikrayat al-‘Amal al-Watani wa-l-Qawmi. Beirut:Al-Markaz al-Thaqafi al-‘Arabi.

Al-Mubaraki, Y. M. 2008. Hin Isti‘ad al-Sha’b al-KuwaytiDusturahu: Waqa‘i’ wa Watha‘iq Diwawin al-Ithnayn1990–1986. Kuwait: Kuwait National Bookshop.

Al-Mughni, H. 2001. Women in Kuwait: The Politics ofGender. London: Saqi Books.

Al-Nakib, Farah. 2013. “Kuwait’s Modern Spectacle: OilWealth and the Making of a New Capital City, 1950–90.” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa, andthe Middle East 33 (1): 7–25.

Amin, A., and N. Thrift. 2007. Cities: Reimagining theUrban. Malden: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Arabian Mission. 1932. “Annual Report of the ArabianMission for the Year 1930–1931.” Neglected Arabia161.

Chamberlain, W. 1917. “A Tour in the Persian Gulf.”Neglected Arabia, no. 100.

1988. “Chronology: January 16, 1988-April 15, 1988.”Middle East Journal 42 (3): 447–478.

Crystal, J. 1995. Oil and Politics in the Gulf: Rulersand Merchants in Kuwait and Qatar. Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.

Dickson, V. 1971. Forty Years in Kuwait. London: GeorgeAllen and Unwin.

Ghabra, S. 1991. “Voluntary Associations in Kuwait: TheFoundation of a New System?” Middle East Journal45 (2): 199–215.

Harvey, D. 2012. Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City tothe Urban Revolution. London: Verso.

Kanna, A. 2011. Dubai: The City as Corporation.Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Kuwait Annual Report 1956 and Kuwait Annual Report.1957. Persian Gulf Administration Reports 1873–1957. 1989. Vol. XI. Cambridge: Archive Editions.

Kuwait Intelligence Summary: 16–30 June 1938a andKuwait Intelligence Summary: 16–31 July1938b. R. Jarman (ed.). 1998. Political Diaries of theArab World: Persian Gulf 1904–1965. Vol. 13.Cambridge: Archive Editions.

Kuwait Intelligence Summary: 16–30 June1940. R. Jarman (ed.). 1998. Political Diaries of theArab World: Persian Gulf 1904–1965. Vol. 14.Cambridge: Archive Editions.

Kuwait Diary: 31 July-26 August 1956. R. Jarman (ed.).1998. Political Diaries of the Arab World: Persian Gulf1904–1965. Vol. 20. Cambridge: Archive Editions.

Lefebvre, H. 1991. The Production of Space. Oxford:Blackwell Publishing.

Lefebvre, H. 1996. Writings on Cities. Oxford: BlackwellPublishing.

Lewcock, R., and Z. Freeth. 1978. Traditional Architecturein Kuwait and the Northern Gulf. London: Archaeol-ogy Research Papers.

Pelly, L. 1865. Report on a Journey to Riyadh in CentralArabia. Cambridge: Oldeander.

Persian Gulf Monthly Report: 3 July-6 August1958. R. Jarman (ed.). 1998. Political Diaries of theArab World: Persian Gulf 1904–1965. Vol. 22.Cambridge: Archive Editions.

Tetreault, M. A. 1993. “Civil Society in Kuwait: ProtectedSpaces and Women’s Rights.” Middle East Journal47–2: 275–291.

Tetreault, M. A. 2000. Stories of Democracy: Politicsand Society in Contemporary Kuwait. New York:Columbia University Press.

Tonkiss, F. 2005. Space, the City and Social Theory: SocialRelations and Urban Forms. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Zukin, S. 1993. Landscapes of Power: From Detroit to Dis-ney World. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Farah al-Nakib is Assistant Professor ofHistory and Director of the Center for GulfStudies at the American University ofKuwait. Email: [email protected]

734 CITY VOL. 18, NO. 6

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Fara

h A

l-N

akib

] at

08:

16 0

7 D

ecem

ber

2014