Proceedings of Workshop on Migration and Urbanisation

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of Proceedings of Workshop on Migration and Urbanisation

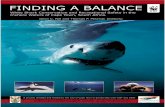

PROCEEDINGS OF WORKSHOP ON MIGRATION AND URBANISATION

MARCH 10 28" 1986

NEW DELHI

Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Ministry of Home Affairs

Government of India 2/A, Mansingh Road

New Delhi

F OJLe.woJtd Pre·face ..

CON TEN T S

Workshop on Migration and Urbanization

Se.c~~on 1 - Migration

1. A modern theory of classification: and the question, who is migrant?

G.P. ChLtprnct:n

2. Place of birth data and lifetime migrati-on

Rona..-ld Ske.-ldon

3 . A note .on sampling and' migration

R.ona:!.d· Skeldon 4. Place of last residence and duration

of residence

Rona.e.d Ske.-ldon

5. Internal. migra,tion in India: An Asses:sment

S.K. S~nha 6. De lhi~ I S mi.gr.i1.nt pr_oblem: Some- i SSue.s

O.P. Sha.Jr.rna.

7. Impact of migration on the growth of Delhi ••

R.K. PuJti.

8. Mobility amqng Indian, women

O. P. Shalt-rna..

..

Page No.

i

iii

vii

1 - 32

33 - 47

48 - 58

59 - 66

67 - 79

93 -112

113 -128

See~~on II - U~ban~za~~on

9.

10.

ll.

12.

13.

14.

Recent urbanization in India .•

B.K. Roy Projection of urban population

K.S. Na.~a.~aja.n

Trends of urbanization in. India ..

R.K. Pu.~~

An analysis of the density differen~ tiation of the popu1at~on of ~ndia 1961, 1971 and 1~81 .•

G.JJ. Cha.lOman

A note on concepts, definitions a~d measures of urbanization an~ urban growth . '.

M.K. Ja.~n

The simulation of the development of national economies real imaginary case studieS

G.P. Cha~man & r~abeLLe T~a.kok

List of participants .,

Topics covered ip the wor~shop

*** ***** ***

Pa.ge No.

129-149

150-181

182-207

208-221

22<2-241

275-2-77

279-280

FOREWORD

The idea of organising a workshop on migration and urbanization was mooted by the Overseas Development Agency (C.D.A.) of the U.K. to the Office of the Registrar General,India in early 1985. The Government of India accepted the proposal and the ini-tial exploratory work was started in September 1985 when ' Dr. J.C. Dewdney, Professor, University of Durham, England, visite~ India and discussed the details of the programme with us. A team of officers finalised the detailed programme and the time ,table of the workshop in consultation with Professor Dewdney. The programme was also agreed to by the British Council in New Delhi.

Twenty three of our middle level officers were selected as participants keeping in view the objective of the workshop, namely to acquaint our officers with the latest research and methodologies in the areas of migration and urbanization.

, As recommended by the C.D.A. CU .K:), the British team consisted

of Dr. Robert W~ Bradnock (School of Oriental & African Studies, University of London) Dr. Ranalk Skeldon (University of Hongkong), Dr. Graham P. Chapman (University of Cambridge), with Professor J.C. Dewdneyas team leader. Resource Persons deputed fram this office were Sarvashri' K.S. Natarajan, S.K. Sinha and M.K. Jain. Dr. B.K.Roy was nominated to lead the workshop from the Indian side.

It is gratifying that the workshop was meticulously planned and ~ampetently conducted.

Considering the long term utility of the vast fund of information imparted and with. the view to make the record of the deliberations available even to others who did not participate, it was decided to publish the proceedings of the workshop ~long with relevant supplementary material.·

Our anxiety to include such material has caused same delay but I hope that the resulting volume will prove useful to researchers and pro~ssiona1s in fostering the knowledge of and investigation into the complexities of migration and urbanization issues of India.

I take this opportunity to express this organisation's gratitude to the Overseas Development Agency of the U.K., the British Council and its officials located in Delhi, the British Experts and our own Offi~ who made this workshop possible and rewarding. ~

New Delhi July 13, 1987

vv.' (v.s~~

Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India

PREFACE

The Overseas Development Agency (U.K.) and the office of the Registrar General, India organised the workshop to reorient the exper1:ise available in this office as the dimensions of migration and urbanizaLion have been ever changing in the context of the contemporary development of the country. The workshop convened by the Registrar General, India during 10 & 27 March, 1986 at New Delhi Nas hence a timely and important deliberation as a reorientatiop programme to the participants of the level of Deputy Directors,Asstt~Dlrecror, ~esearch Office·.cs, including a few Geographers drawn from the field iirectorates of the Census Operations of States/Union Territories and headquarters of the Census of India who have been actively ~ngag8d in the Census 'taking, writing reports or annotatio.ns of :ensus data on various issues of migration and urbanization.

A few words about the workshop may be relevant here. The fellberaLions of the workshop, in general, were organised in two vays, (i) by the ora tical lecturing and (ii) through solving practica~ exercises by the parcicipants followed by discussions. Among the theoratical aspects, the workshop touched upon debatable questions On the concepts and definitions of migration and urbanization. In the realm of migration, a comprehensive evaluation of literature related to motivation and decision making in migration alongwith c.hangirlg levels of various forms of mobility through time were discussed. This led, furthermore, to define total migration and outmigration between areas as well the net migration evaluated. Besides, taxonomic models pertaining to theories of migration and circulatory movement behaviour in populat~ons were elaborated.

The migration and urbanization links were specially analysed with reference to contemporary situations of economic development in India. In addition, important issues of similar problems confronted by Britain, the U.S.A. and some developing countries of South-East Asia in their urbanization systems were also highlighted.

In the practical exercises, the participants were provided data from the Indian census for testing some of the hypothesis on the major themes of theoretical aspects. In addition, a Simulation Model b&sed on an imaginary 'State' was generated to subscribe multi-level geographic responses to economic development and policies. The workshop also devoted an afternoon session on the values of CensuS Cartography with special reference to migration and urbanization mapping as comprehensive and basic tool for reporting and analysing the subject for examining spatial patterns.

The decision of the Registrar General, India to work out the proceedings of this workshop by including the lectures of the British team and reading materials by the Resource PersonS and others is encouraging to bring out the entire materials in thi~ volume. It has been tried that almost all aspects, as far as possible, are gathered ln the proceedings for ~vhich, a spade work and cooperation of all concerned associated with the workshop is highly acknowledged.

iv

Soon after the workshop w'as over, I could c..ontact the specialists of the British Team and Resource Pereons of tlle wo::kshop for their scr!.pts of papers. A few other papers having d:!,j_'ect rereyance to the frame of the workshop which I could collest frem var.~cus other authors as reading naterials are also included in ~his volume to mak~ it a comprehensive record. It was very encouraging nr..d prcL(. t:'cally in a short time, all the manu€c..ripts were at my disposal whieh t'l.nde my job easier to go ahead for the final:'zat:'on of: the 'nlume.

A set of 14 papers are p!"esented in this book into two sections viz., \i) Migr~ti0n having eight papers and (ii) Urbanization with six papers, preceded by an official report On the workshop preparec by Shri S.K. Sinha, Senior Research Officer of this office who patiently attended all the events of the workshop during the period. In the end, two appendices are given recording the list of partic~Fants, and ~opics covered in the workshop to make the entire p::oceeding a land~ark for record, reference and consultation.

Organising a workshop like the present one for n per!od of abo~t three weeks is a challenging job consicering the limited resources at our disposal. As soon as the responsibility was given to me, a well knit team of workers assisting for vario~s needs, such as, acc.:mIllodation to the participants in &. city like Delhi and arrangement of transport attracted my mind. A small secretariat worked for this comprising of Mrs. M. Ghosh, Map Officer and her team consis~ing of S!shri P.S. Chhikara, R.N. Chhipa, P.K.Patnaik, P.K. MandaI, Mohd. Ishaq, D, Thakur, Raj Kumar, etc. My steno, Shri S. Agarwal with others ~hared a huge typing responsibility fa!" the workshop • Another most impor;'tant function shared in Map Division was a huge load of reproglapcy and making of transparencies for specialists' visual aids to the pn:: tic i'?ants • S.'911:::i R.R. Ch3kraborty and S.K. Mukherjee assisted by Shri Vishnu Dayal performed this creditably , ... ithout any, grievances. J:n adciition, I could get tho fulL-c..ooperation of the Administraticn Division at eYery step for various supports.

As soon as the publication of the proceedings was plonned, Shri O.P. Sharma, Deputy Director caneforth spontaneously with the assistance of Shri Brahm Dutt, Senior Technical Assistant(VT) and Sh:'i R.D. AjbanL, Technical Assistant(VT) who prepared varitype plates of the entire manuscript which in itself is a great task to complete in such a short time and with accuracy. The ccmparison of the varitype galley-proofs with the original texts of the papers were done by S/shri Pooran Singh, K.Kumar and B.B. Jain. Miss Suman Gupta and Miss Sarita ulso shared this work to limited extent under the supervision of Shri Mahesh Ram, Research Officer (Map) . Shri P.K.Banerjee,· Senio:' Technical Assistant (Rotaprint) and Shri am P:'akash, Rota Print Machine Operat~r took great pains to execute their part of the job i.e.,printing with great technical competence.Shrl B.P. Jain, Assistant

v

Direc~or in the Pri~ting Cell of th~s office, helped us to arrange fo~ b10ck oaking of maps and diagrans and printing of the proceedings.

L&st but not the least, I am thankful to Shri \.S. Verma,I.A.S., RegistLar General, India to give mc the reaponsibility to organise the workshop and bring out the publica~ion. Also, I am t''llilnkful to the f:coource Persons of the workshop and Shri N. Rama Rao, Lssistant Regist~ar General (C&T) in various ways who ~elped me at every stage :or a successful conplction of the 'W'o!'kshop. The pAtience of the partic:'pants is laudab::"e as they were attentive dur::"ng the span of the entire workshop withot.:.t any ..... oss of time dnd inte;!:'cst 88 thE. cu!'io~sity WAS created by ~he specialists of the British Team du~ing ~he de:iberations at every point. This lead to n ve=y high standard of exchange of views on various technical and profesGionn~ issues on the taemes. I, therefore, owe m)re than I cVn adequately express ii!'st to the Reg::..strar General, InciA to provida a forum, such as this workshop, and ~hen tv the British ~earn for otim~lating ~ecture5, 'vhile: our other COlleagues haYe througnout contribu~ed in many wayo in the success of the workshop.

The support ,;)! }!r. Dll'· id Theobald, First Secretary and Miss G. Majumdar, ~sstt. Progrnnme Offi~er of the B=itish Council diVision, New Deihi is aso nc~owledged whc, nt short r.otice9 were helpful in providing w:i.th <.:ale:ule.tors and other equipments; my grntcfelness to all of them. It is belieyed ~hat this pr(.ceed::!.n~

may p=ovide excl.ting pnpe:.:s to everyone. cor.cerncd to meas,ure and eV3luatc the dynamics of migrati~n and urbanization to a great extent.

~A~ f~~Y~ ~ ~ """'1 .,~ £" ." ~:'1.

Ke\~ Delhi (B.K. ROY) 26 May, 1987 Deputy Registrar Gene~ai(Map)

JJ.9_R_K_?_H.9_P_.9~_~_I.fl~_tl.J_I.9~_l\~_D_y_R§~~_?~JJ.9iJ

~a_r_c~ _ ~ ~ _-_ ~;:r:.c~ _ ~~ '_ ] 2~~ , ____ ~ _R~p~r:_t_

Migratlon is the outcome of a decision making process

by an individual or household. The decision making process 1S

initiated by a relative dissatisfaction with the present place

and/or by perce1ved opportunities at the place of destinatlon

commonly known as 'push' and 'pull' factors. Urbanisation on the

other hand entails a profound process of social and economic

transformatlon, Migration and Urbanl.sation are two very broad

topics linked with any population redistribution policy. The

ultimate aim of any population redistribution policy is to

achieve a desired balanced development of the human settlement

system which may include metropolitan regions, major cities,

growth centres, medium-sized towns, small towns, rural settle

ments etc. Realising the importance of the linkages between

migration and urbanisation, the Economic and Social Commission

for Asia and the Pac1fic (ESCAP) proposed detailed comparative

studies of m1gration and urbanisation in relation to development •

These were called the 'national migration surveys' and were

undertaken by several countries around early 80's.

•

The Government of India has also been fully aware of

the importance of studying migration in relation to urbanisation

and development. The Registrar General's Office has been the

nodal department for undertaking such studies and data producing

through censuses" The scope of such data has been enlarged in

the 1981 Census greatly 0 However 1t was noted with concern

about the non-availability of migration data at specific urban

levels excluding Million cities.

The idea of organising a works-hop on migration and

urbanisation took shape sometime in early 1985. With the

help of the Overseas Development Agency (ODA) of the UK

Government, a workshop on the application and utility of

indirect methods of estimating fertility and mortality was

organised in March-April 1984. This workshop was intended

to train officers o~the Registrar General's Office in specific

demographic techniques of fertility and mortality.

A follow up programme for the propoSed workshop

on migration and urbanisation was worked out in September,

1985 by Prof. J.C. Dewdney of the University of Durham in -

consultation with the Registrar General, India and later with

a team of Registrar General's Office Officers consisting of

Dr. B.K. Roy, Deputy Registrar General (Map), Dr. N.G. Nag,

Deputy Registrar General (SS), Shri N. Rama Rao, Assistant

Registrar General (C&T), Shri K.S. Natarajan, Assistant

Registrar General (Demography) and Shri M.K. Jain, Senior

Research Officer.

The workshop was not intended to be confined to

migration apd its effects on urbanisation but was to be

very wide ranginSI covering as many aspects of migration

(all types) and urbanisation as could be dealt with in the

time available. A period of three weeks was agreed upon

for this workshop and the duration was fixed tentatively

from March 10 - March 28, 1986. The workshop was actually

held on these days. Reg;;:,arding the possible topics, it was

agreed upon that the course should include comparison of

Indian census data and methods with those of other countries,

I~

modern methods of census analysis, Cartographic as well as statistical methods, migration theories, historical aspects

of migration, urbanisation as well as its recent trends,

including international migrationso' As the focus was more

on methods and interrelations, larger part of the workshop

was intended to be covered by formal lecture pres~~tions and group discussions and correspondingly smaller el~ment

of practical work. Practical work was also intended to be

mainly on Indian data.

The British expert team consisted of Prof. J.C.

Dewdrtey, University of Durham, Dr. G.P. Chapman, Universi,ty

of Cambridge, Dr. R.Skeldon, University of Hongkong and

Dr. R.W. Bradnock, School of Oriental and African studies,

London. All these experts are famous Geographers specialised

in these fields. Prof. Dewdney was the team leader. In

order to help the British e~perts, who were the main speakers

for the workshop, S/Shri K.S. Natarajan, Assistant Registrar

General (Demography), S.K. Sinha, Senior Research Officer

and M.K. Jain, Senior Research Officer, were made responsible

to work as resource personnel. These resource personnel were

expected to assist the lectures in initiating discussions,

providing necessary census data, reading materials and other

logistic supports. Dr. B.K. Roy, Deputy Registrar General

(Map) was the over-all incharge of the workshop. He was

assisted by this colleagues of the Map Division.

The workshop was formally inaugurated by the

Registrar General,India, Shri V.S. Verma on +Oth March,

1986 at 10.00 AM. The inauguration function was attended by

Dr. D. Theobald, First Secretary, Cultural Affairs of the

British Council, Miss Majumdar, Assistant Programme Officer . of the British Council, beside~ heads of divisions, resource

personnel, the British experts, and the part~cipants. Twenty

five participants consisting of officers of various divisions

of Registrar General's Office as well as from various

census directorates attended the workshop. The resource

personnel gave a number of reading materials' in the form of

papers and data sheets. A list of the materials available

with this workshop is given in the appendix. Copies of the

papers supplied by the resource persons are also attached.

Prof. Dewdney started the course of the workshop

by lect~ring on the concepts and definition of migration,

types of human mobility, distinguishing migrants from

other movers such as commuters etc. He also stressed on

the problems of international comparability of migration

data and its limitations. He compared the Indian migration

data -from the census with that of the U.K. migration data.

There was a lively discussion on the problem of defining

who is a migrant. The UN definition of migration was also

disqussed in det~il. Persons moving through time and space

(geogr~phical boundaries) and changing the place of their

residence are termed as migrants. Commuters are those who

move from one place to other but return back to the place

of residence and as such do not change the place of residence.

Commuters and migrants together form what is known as

'movers' or 'mobile population'. After introducing the

basic concepts of m~gration, Prof. Dewdney invited Dr. Chapman

who gave interesting lectures on international migration,

data sources and problems and India's role in the international

migration (i.e. Indians living abroad).

Data sources and their reconcilation on Internal

Migration was dealt with by Dr. Skeldon. He took a couple

of lectures on this topic and discussed the Indian data on

Internal Migration. Cerisus h~s re~ained the main source of

internal migration 'in India. He discussed the various

studies on internal migration undertaken by various Indian

scholars,like Zacharia, Mukherjee, Das Gupta etc. and also

the famou!':· ILO study in' Ludhiana: The place of birth data

giving life-time migration and its limitations, were dealt

at length and th~ri duratio~ of residerice and migration by

place of last residerice ~ere also discussed in detail.

Dr,. Skeldon also took a few lectures on the ESCAP national

migration surveys. The primary objective of th,F!se national

migration surveys has been to supplement the migration data

from the census and also "to assist decision makers in

policy formulation on population redistribution and programme

development for controlling the volume and directi~n of

population movements in order to help achieve the national

development goals". (ESCAP,· 1979, 3p.)

The first we~k of the workshop, therefs>re, covered

basic topics on international and internal migration in

India, comparison of Indian data with that of other countries

such as Britain, definition of migration, various concepts

relating to migration and various research studies on

migration in India and also the ESCAP migration surve~s.

-xi i_

In the second week Prof. Dewdney spoke on the

migration rates, ratios, and other indices, in-migration,

outmigrants, gros's-migration, net migration, and migration

streams etc. Dr. Chapman and Dr. Skeldon took lectures on

the types of'migrants by age, sex, economic status,

educational levels, reasons of moves and nature of movers,

distance of move etc. Dr. Chapman discussed in detail the

concept a of 'Population Poteritial f, population density,

cartographic depiction and anal,~sis of migrants integrating

urbanisation and migration. Indirect and direct measures

of migration through th~ vitai statistics method and the _. "

survivorship ratio method were discussed by Dr. Skeldon.

- In the secon_d week itself Dr. Bradnock took a preliminary

lecture on the relationship betwe~n migration and

urb'anisation.

A number of practical exercises were ,attempted by

the participants using Indian data on the various migration

rates etc. Gravity model, Todaro's model and other

migration theories such as that of Ravenstein and Lee were

also discussed by Prof. Dewdney and Dr. Skeldon.

One of the practical exercise was a simulation

model on market behaviours and impact of migration on

economic growth by Dr. Chapman. It was interesting and

he ~volved all the participants. He visualised an economy -

in which there is little interaction between rural and

urban areas. There were cultivators with large and small

families and with uneven land distribution. There are

frequent occurances of, drought and there is lack of

institutional support. The vill~ge has a few rich farmers

and in the town there is the President assisted by his

Industry Minister and the Government Agent. The simula

tion model included an industrialist, an urban labour and

a banker. The data generated on the basis of five conse

cutive crops indicated that there is no cooperative effort

i~ the viilage inhabitants and due to frequent drought

conditions and uneven land di~tribution as well as high

fertility and mortality conditions, only a few cultivators

could get the benefits of technological and institutional )

support, due to initiative and risk. This was to assess

how migration in the presumed economic condition originates.

There was lack of rural to urban migration due to high

cost of movement and lack of policy. The simulation model

generated lot of interest among the participants. This

gave a practical 'approach to the linkages between migration

and 'economic development.

In the third week, lectures on urbanisation were

taken by Dr. Bradnock. He discussed the problem of defini

tion of an area to be declared as urban in the census as

definition of 'urban' varies from country to country. Even

the UN has not been. able to standardise the definition of . . . 'urban' .

Dr. Bradnock discussed the various dimensions of

Indian urbanisation. Urbanisation has implied an increasingly

territorial division of labour. Urban and rural areas

become increasingly interdependent economicall~. Specialisation

and interdependence are the product of industrialisation

and it is the pattern of urbanisation that distinguishes

the modern period from earlier ones. Earlier urban centres ,

served as residences of I~lites, crafts and tradera .and centres

for administrative activities. Indian urb~isation is

characterised by higher urban growth without much economic

growth and industrialisation. Dr. Bradnoqk discussed various

characteristics of Indian urbanisation and introduced various

measures like degree tempo, and scale of urbanisation. He

also discussed problems connected with population projections,

especially projecting urban population and how migration

affects urban growth. He lectured on the problems relating

to projecting population of metropolitan areas and of big

towns and discussed the limitations of the UN method of

projecting urban population using the Urban-Rural Growth

difference (URGD) method. He alsQ gave some insight into

the historicai aspects of urbanisation in India.

In the third week Prof. Dewdney took a couple of

lectures on Census' Cartography. Using UK ·data on migration

between regions etc. Prof. Dewdney discussed and introduced

census cat:~~iraphy and the various problems and its limit.ations.

He and Dr. Champman referred to computerised cartographical

methods as well as the utility of ~emote ~ensing and

photointerpretation. On this topic lively discussions ·took

place with Dr. B.~. Roy, Deputy Registrar General (Map) defending

the present cartographical approach followed in India and

pointing out the limitations of computerised cartography,

map preparation and remote sensing in the Indian conditions.

However, he ~elt a bright future to use this technology in

the Indian ~ensus in near future.

All through the three weeks, the period of the

workshop, lively discussions took place and most of the

participants took acti~e interests. Th~enlightened

the British experts on the field problems of the Indian

Census. The participants were fully exposed to the concepts,

definitions and various methods of migration analysis and

its links with urbanisation and the related problems and

limitations.

The training received by the participants could

be utilised properly if they are offered research projects

and opportunities to work and analyse migration data

pertaining to their states of postings. This workshop was

a great success but J.ultimately the impact of such

specialised, training should be translated into practice by

offering the participants to take up analytical and

research work and preparing reports. It is desirable that

each participant may be requested to prepare a background

paper on migration and urbanisation relating to his/her

field of choice.

The British experts were also satisfied and happy

with the workshop. Theyappreciated the work done by the

resource personnel as well as on the research projects

undertaken by Registrar General's office on migration and

urbanisation.

At the end of the workshop the participants presented

citations and souvenirs to the British Professors. The

concluding sessi0n was attended by the Registrar General,

India, Joint Registrar General, India, Deputy Registrar

General (Map), Assistant Registrar General (C&T), Assistant

Registrar Generil (Map), resource personn~l officers of the

Map Division besides Dr. D. Theobold and Miss Majumdar of

British council. The Registrar General and pRG(Map)

thanked the British Professors and the British Council and

congratulated the participants for their active interest

and hard work. The concluding function ended with a forma'}.

vote of thanks to the Chair.

***** **.* *

~_~Q~~~~_~~~Q~~_Q~_~~~~~!~!~~~~Q~_~_~~Q_~~~_QQ~~!~9.~,

vmo IS A MIGRANT?

G. P. Chapman

INTROVUCTIOM

This paper is an attempt to demonstrate

pedagogica~ly the way in which Atkin's ideas (1974,1977,

1981) on sets of elements, hierarchies of sets, and their

intersection can be applied to many of the thorny old

problems of classification in agricultural analysis and

migration analysis. To do so we have to start with a

rough idea of what is meant by a set, a relatlon, a

hierarchy of sets, and the ideas of holism and

intersection.

I. VEFINITION

a.) El e.m e.n.t.6 a.nd .6 e.:t.6

Without getting trapped by arguments about

'processes' rather than 'things', I will say quite simply

that we will in any given situation define or imagine some

set of basic building block, individuals to be classified,

which represent the fundamental level, the elements, of

the current study. A field biologist might take the

following as some elements: ant, bee, fig tree. A linguist

might, in the classification of languages, take French,

English, Hindi as some of his elements. A set is defined a

as any defi~ed collection of elements. The set may have

a name or be indicated by a symbol. I could define the

set x

:t -} X == \a, b, d

-2-

where the curly brackets indicate the set, and X is

the name of the set, and a, band d are the elements.

An alternative way of defining sets is to say

x = {a / a is a cat living in England]

In general, using a definition to test set membership

like this is less satisfactory, since until all

candidates bav.e been considered we are not sure whether

the test of merobe.rship is going to be a good one which

will give a simple answer in each case. If I were to

say

x ={a/a is a rich man}

the de:Einition would be left very unclear.

A set can have no members, and it is then known

as the Null set and written ¢.

b) Rela.tion.6 be,..tween .6e.t.o

A relation can be envisaged as a matrix of

zeros and units - on one axis of the matrix are the

elements of one set, and on the other axis of the matrix

are the elements of the other (or sometimes the same) set.

If a unit is recorded in the matrix, it means that the

two elements defined by the row and column of that cell

are related in a defined manner. Suppose we have six

people and eight cats, we would define the owning relation

ioj which means that person i owns cat j. We could define

a liking relation - which need not of course be the same

thing at all. One of the important points to notice is

that these relations are found by observing scmething,

and recording data. One could fill one of these matrices

-3-

by imagination, but not necessarily by theorizing.

In most cases observation is the only way the data

is found.

c.l Se.t.6 and E..e..emen.t.6 all.e Logic.a.e...e..y V'<:'66eltent

To show how different sets and elements are,

we are going to consider a paradox, the paradox of the

Barber of Old Delhl.

In Old Delhi, there is a man who is the barber,

who shaves all those men and only those men who do not

shave themselves. Does the barber shave himself?

If -:·.he does shave himself he is not shaved by

the barber, since the barber shaves those men and only

those men who do not shave theselves. But that can't

be right, because he is the barber. On the other hand, no-I;

if he does/shave himself, he cannot be shaved by the

barber, who shaves all those men and only those men

who do not shave themselves. The resolution of this

paradox lies in the fact that we are using two distinct

meanings of the w~rd (barber'. The barber as an element,

a man, is one meaning. The other is the barber as a set,

a set of men defined by the shaving relation - i~e.

the barber is the set of all those men who shave other

men. Even if there is only one man in Delhi who shaves

other men, say Md. Karim, the meaning of the barber as

Md. Karim, an element, is a man, is 'different from the

meaning of the barber as the set of those who shave

others, which is B = {Md. Karim}. Suppose you have a

friend Mr. Riszvi who sits an examination with many

other people. Suppose the set of all successful

candidates is S = {Mde RiszVi}. It is quite clear that

the concept of successful candidates and your friend

Md. Riszvi are not the same.

-4-

Now of course there are many barbers" in Old'Delhi.

But ~et us pretend there is only one. Does the barber, an

element, a man, shave himse-If ? the paradoxical answers

given ~bove can be resolved as follows. If he (~irst

meaning, q man, an element) does, then he is not shaved

by the barber (second meaning, the set of all men who

shave those who do not shave themselves). So we find

we are confusing two logically district meanings within

one sentepce, because both meanings are conveyed by one

word. The solution is to restrict ourselves to one

meaning when asking the question, say that of the element,

and then simply to find out- whether or not the barber

does shave himself - it is a simple matter of data.

It is interesting to note, but not altogether

surprising to discover, that in English the distinction

is implicitly recognized in the sentence, 'I am going

t~ the barber's shop today'. The noun is the singular

(genitive), implying an element, but the meaning is 'I

will go to that barber's_ shop of all the barbers' shops,

to which I normally g~; or I will go to any barber's shop.

The singular and plural meanings are quite evident.

I have found it quite instructive to playa game

in which one thinks of a word, then elevates it by

turning it into qapital letters and thinking of it as

a set, and then wondering how the element and the set

differ. If one thinks of a language, say English, as an

element, a member 6f the set of all languages, what is

ENGLISH? ENGLISH is a set of languages, which includes

English English as but one member, Canadian English,

American English, Punjabi English etc. as others.

-5-

The consequences of the distinction between {b}

and b are profound and far-reaching. Sets are distinct

from elements, and sets of sets are distinct from sets,

and so on up the hierarchy. At the bottorn_ we have elements, -

say a, b, c, d, e, f. At the next level one can have any

sets that one needs or finds useful, including non

partitional (i.e. intersecting) ones, p~oyiding that

they are all members of the power set of the elements -

that is the set of all possible subsets of the original

set. If there are n original elements, then there ~re

2n members of the power set, any of.w~~ph can be at the

.next hierarchical level above the elements. In this

case we have 27 possible numbers = .128, _such as {a, f, g}

or {e, f, g} - all of them distinct.

11. HIERARCHIES

To some extent this section 'heading is misleading,

because I will show that the first of the t.~ ways of

building a hierarchy is in some sense inferior t~ the second.

The first merely involves enlarging sets at the same

hierarchical level, so the hierarchy is a kind of pseudo

hierarchy. The second tnvolves climbing the hierarchy

of power sets and displays the holistic natur~ nature of

such operations.

This, the usual approach, simply involves

collecting elements into sets, and joining these sets

into bigger sets. Suppose we have a set of trees

G = {a, b, c, d, e, f] , being respectively mango, coconut,

-6-

neem, bamboo,1 1 banana, jackf.ruit. We can group these into

frui t trees = F, and non-fruit trees = N. We can :.: ;,-.'.:~"~.:

~produce a hierarchy by aggregation as follows:

set of all trees = G = F U .N ;~/' c

f} d} types of trees F = {\ \ e, f

individual tree species abc

The only operation involved is set union U, the addition

or merging of sets.

'We also find that if:-

(meaning la' is within or an element of F)

and F C G (F is a subset of G)

then a E G.

For example, if a banana tree is a fruit tree, and a fruit

tree is a tree, then a banana tree is a tree. The

classification is known as agrregation because only set

union is involved.

Two sets may have elements in common (they intersect)

but are not equal to each other.

If A = {a, b, c} and B = { a, b, f} then A ~ B

That is a simple definition of set theory, but it has

practical use. Suppose~:. we wished to relate the pre-

conditions of an event to an event itself. (This is

1) Anyone who objects that bamboo and banana are not trees will miss the point of much of this paper.

-7-

rather like talking about necessary and sufficient

conditions). Suppose I have four elements, a = Car,

b = Driver, c = petrol, d=water, then

A ={a, b, c} -I B ={a, b, d}

and we look at the two relations between the two sets

A and B and the results Movement and Swearing, we may

get: Movement Swearing

A A

B B

Here we will look at a two level hierarchy using

members of the power sets generated at each level.

Suppose a = wall (s), b = covered floor, c = door,

e = roof, since there are five members of this set of elements

there are 2 5 = 32 members of the power set, many of which

will in a holistic manner have 'no meaning'. Does a roof

without walls mean anything?

Let us suppose for the sake of the argument that

we can recognise in some farmstead the following

H, C) I C =

Note that this time a E House means that a wall is an

element of a house, and H E F means that a house is an

element of the far~, but it does not mean a wall is a farm.

-8-

In the case of Aggregative Hierarchies (IIa above),

the name of a class is appropriate to a quality which

can be applied individually to the elements in a class.

Hence all members of the set TREES are trees. This is

inseparable from the fact that we are using set unions

as the only means of 'climbing' the hierarchy, the unions

being defined for a property cornmon to all elements at

any 'level', By constrast, in the holistic combinatorial

use of sPots, since we 'climb' the hie~archy by whole

sets, the name is applied to the set in its entirety,

and need ~ot reflect any property cornmon to all elements.

I I 1.

0.)

PARTITION VS. COVERSET IN AGGREGATIVE ANV HOLlSTIC HIERARCHIES

Ag 9 IL eg a.t.Lv e. H.L eILa,1L c. h.L e1l

For reasons which are difficult to state briefly,

there has in the West been an assumption within formal

intellectual debate that hierarchies should be partitional.

This means th~t something at a lower level belongs to one

and only one class at a higher level. Thus we would not

allow, through dubious claims to scientific logic, the

schemE below for 'serious' study.

/trees~

fruit timber

I~/\ coconut mango neem

It represents an intersecting (coverset) hierarchYJ~u~ to

every-day man not only is such a hierarchy 'true', it is

the very essence of life - multiple categories and

multiple uses of things.

-9-

We will consider first the case of intersection

in the aggregative hierarchy. Suppose we consider that

trees can be grouped into timber trees - the set K -

and fruit_ trees - the set F - and N the trees that-are

neither. K and F could well intersect.

G=FUKUN = c, d, e, f)

66 %

Partitionalists do not like this approach, because

(i) at some points some sets overlap each other, so that

the isolation of some problem or quality for study is

impossible; (ii) at anyone level numbers, for example

the percentages of individuals in the classes of trees

in the above example, do not necessarily add up to a

predetermined total.

Most irritating of all, as soon as we allow

_ intersection, we play havoo with the idea of 'levels'

the idea that one level is 'above' another. Provided

that we maintain a partitional approach, we can even

with these aggregative hierarchies maintain the fiction

that there are indeed higher and lower levels, even although

we have already shown that the aggregative hierarchy

involving only set union actually stays at one level.

-10-

Since, as we have said, the real world is usually full

of intersecting hierarchies, the traditional approach

which is rarely questioned, is to use several ditferent

hierarchies to cross-classify the basic data, making

sure that each of these hierarchies is used separately

(orthogonally) and is itself partitional.

Consider crop varieties,a,b,c,d,e,f,g,h, and

these three orthogonal hierarchies.

genetic history season cereals

\

f\ \\ \. .I .

local LIV HYV r~ce wheat

A contingency table will have dimensions 3 x 3 x 2.

Here we draw the 3 x 3 table, and indicate the third

dimension by saying that leI is wheat and all other rice.

Aus Aman Rabi

HYV a ,be. e ---

LIV g

L

Initially the discussion will be limited to the 3 x 3

table. We can derive a two-level hierarchy on one

-11-

axis as follows:

Aus Aman Rabi

!\ I Aus HYV Aus L

/\~ AID.an HYV Aman LIV Aman L Rabi HYV

and on the other axis as follows:

HYV LIV L (Local)

/1'" ;\ /' '''"'' ~ \ " II \

Aus ;HYV Aman HYV Rabi HYV Aman LIV Aus L Aman L

If we include the third dimension, the rice/wheat

distinction, we can have any of six different arrangements

of three-level hierarchies, two of which are:

wheat rice

t

I rabi wheat

~ '-" "'-,

....... rice Aus

I / '~ "- ~ rabi HYV wheat AIDan HYV

e b,c

Aman LIV rice

g

AIDan L r~ce

h

Aus HYV rice Aus L

a d,f

ric

-12-

Rabi Aus Aman

I I \

Rabi wheat

I

I AIls rice l\man ri\, /~ / /'"

",'" '\ ,,' ." r

Rabi HYV wheat Aus HYV rice Aus, L rice Aman HYV rice .Arnan LIV

e a d,f b,c g

kttan L rice

h

If there is any 'problem' it appears to be tha.t 'We can use the major

orthogonal axes to divide each other at arbitrary levels - e.g. divide

plant type by season, or season by plant type.

Th~se 'problems' are self-inflicted. The 'fact' that there are

these different hierarchies ~s an illusion brought a1x>ut by the unspoken

assumption that the hierarchie.s must be parti tiona 1 - as indeed the

above ones are. All six of the 'possible' hierarchies, two of which

are shown above, are in fact .partitional subsets of the single cover set

(Le. intersecting) hierarchy which rises simultaneously on all three

axes. This simultaneous hierarchy looks like this:

e

a:

d,f

g

b,c h

rice

-13-

The major observation we can make as a result

of this discovery is that partiti~ning is a highly

selective filtering of the overall coverset classification

system, which produces paltry subsets. If one uses such

subsets one is always plagued by the nagging doubt that

one should have done it the other way round - and indeed

the first question at any seminar often lS, 'why did

you not do it the other way round ?'

Such a diagram represents a Gallois lattice,

which has been the subject of investigation by Marsh

(1983} and othe~s.

We will use an example based on foods and diet.

Suppose a = cooked rice, b = unleavened wheat bread, c =

lentils, d = ,fish. The power set of these foods will

have 16 members, but of those 16 only some will constitute

true meals. To nSb rice with lentil but neither rice

nor wheat we will define as not a true meal. So here I

produce my list of true meals.

poor man's meals rich man's meals

Pl= {a,c} p/Z"{a,d} P3= {blC} P4= {b,d}

1<'3={b,C,d} FA= {a,c,d} F5= {a,b,c,d}

Rl= {a,b,c} F2={a,b,d}

elements a b c

According to this schema there are many intersections:

all meals must have at least rice or wheat in them and

at least either lentil or fish. But the poor man can

never have both rice and wheat at the same meal, and never

both lentil and fish. But as any cook knows, wneat and

d

-14-

fish are holistically different as a meal from wheat

and lentils. The whole scheme is based on the holistic

difference of the sets.

Such is the intuitive subtlety of the human

mind we find that quite often both aggregative and

holistic hierarchies are used together. Remember that

we have already sai,d that an aggregative hierarchyuses

the concept .of OR - that F (fruit trees) is Banana OR

Mango OR Jackfruit OR Coconut - whereas the Holistic

Hierarchy uses the concept AND - that a meal is both

staple carbohydrate AND protein. We will define the

set of Carbohydrates C, and the set of P~oteins P.

Although at rock bottom we can return to a long

list of holistic members of the power set, there are

often so many (even with 5 eleme'nts we would have 32

possibilities to consider, with 10 elements 1024

possibilities) that we often use a short hand to reduce

the apparent number, by indicating groups of acceptable

sets. For example, let us define a good diet as G = {c, p} If we use only the holistic power set approach

we get:

G = {c p}

= {{a,b} , {C'd}} which would appear to indicate that a good diet was both

rice and wheat as well as both lentil and fish. What

we actually want to say is:

{(a or b) and (c or d)}

-15-

We can see that this corresponds to an aggregate of the

meals defined above.

G = {PI or P2 or P3 or p4 or Rl or ,R2 or R3 or R4 or RS}.

and that we are trying to achieve a shorthand way of

saying so by ind~cating incorrectly that G = {C r p}

Henceforth in this paper we will use notation

which avoids all this ambiguity. A superscript * will ,_j;

indicate lany element of the set'. Therefore A Good

Diet is any member of the set Gt = {c*, p*}

IV. EXAMPLES

a) Th~ O~gan~za~~on on a Fa~m

I will start by sketching in a simple minded way

how one might think of a farm. It will turn out that I

think such a way has no value, and is an invitation to

sloppy thinking. But that is where we will start.

~Farmer

Animals Latoure~crops ~ t ~

Work Tools Fields

The problems with this diagram are legion: I have not

said what the arrows mean: are they subordination - but

are crops I subordinate I to farmers? - are they location -

crops are in fields ? - are they control - do animals

'control' rather than 'provide' work? Also, although I

-16-

have different levels, are not farmers and labourers

at one level all men? DO not farmers and labourers

work as well as animals ?

If we ap.ply a little rigour to this situation,

we see we must distinguish between elements and sets,

and between sets and the relations between sets.

If we try again, we mught define -five hierarchies

here, and many relations between different levels in

the hierarchies. The hierarchies are CROPS, FIELDS,

IMPLEMEN'r_S, PEOPLE, ANIMALS. We can define any

appropriate number of levels we wish: here we mostly

define three, in on~ case two levels. (It seems a rule

of thumb (or the human mind more likely) that in any

given study three levels seems to be the useful number}.

We will identify the hierarchies by the word defining

the single set at the top of each (we do not have to

have a single set at the top: that is merely what I

have done in this case).

The definition of 'the farm' amounts to the

relations between all these sets, ego the ~ow~ng relation

between crop types and fields, the wOJr..k.~ng. relation

between labour and fields, the u~~ng relation between

labourers and implements etc.

-17-

FIGURE ;/.. 1

tLi.. e.fL a.fL c hi e..6 on S e..t.6 on .the.. FafLm

eN vl cN+1

v2 rice

v3 wheat eN+2

v4 kharif CROPS

vS rabi

v6

v7

v8

FN fl FN+l

f2 wet

f3 FN+2 . f4 FIELDS

fS dry

f6

f7

IN plough r N+l r N+2

hoe Field . ladder IMPLEMENTS

thresher Farmstead

stove

pN m pN+l

m pN+2

m Labour

m Family PEOPLE

f

f kitchen

f

AN cow AN+l

bullock Domestic AN+2

heron wild ANIMALS

-19-

This is a very complex affair: but then reality

is complex ~nd there is no point in pretending otherwise.

We can simplify the way we see thinqs by going up

the hierarchy, but that does not mean that this simple

view does not ultimate 'rest on something much more

complicated which for the time being we chose to ignore.

The relations that define the farm structure are

horizontal, vertical and 'diagonal'. For example, the

relations between people and fields could be:

Diagrammatically the 'whole farm' is indicated

by many relations, not all of which will be monitored

or known, nor indeed all of which WQuld be interesting.

But let us look at the possibilities. We use the

conventional notation that the lowest level of a

hierarchy, saye is N written eN. The next two highest

levels are then e N+l and e N+2 . There are fifteen

nodal points on the diagram, so there are 15 x 14/2 = 105 possihle relations, shown in Fig.a. Let us choose

-20-

a few at random to see what they might be.

e N+2 r AN+2 might simply be 'animals work on

crops' or 'animals eat crops'. In general such high

level relations will not be of much interest. FN r I N+l

would be probably that implements are used in all fields.

Again perhaps not very interesting. eN r FN could be,

which crop varieties are in ~hich fields, and would be

very interesting. ,eN f FN+I would be which crop

varieties are in which field types, which might be of . N+l N+l great interest to agronom1sts. e r P - might be a

working relation: which types(s} of labour (family,

(hired) labour, kitchen lapour) worked on which crop

types.

The relations should be consis~ent, so that eN r N N N+I. h . . N N+I h' t F X F r F 1S t e same as e r F • In t 1S even

it is possible to collect only the data indicated by

Figure 3, in which case all other relations are calculable

and all other questions answerable. But note this only

applies to dealing with the relations that we have

collected: if there are other relations - such as people

liking crops rather than only working with them - then

of course other data would have to be collected.

At the workshop of Urbanization and Migration

the question of the definition of a migrant became quite

significant. Is a migrant someone who has returned

to his village, from a spell in town? If so a spell of

what duration ?

-22-

FIGURE 4

n N male pN+l

female Sex p N+2

harijan, Caste PEOPLE

kayasth Age

old etc.

young

etc.

PLN Sonagaon PLN+ l

Rampur Andhra pradesh PLN+2

Begumbazar Bihar PLACES

etc. Urban

Rural

etc.

IN I hour

daily IN+l IN+2

hourly

seasonally Frquency

retu:.r:n Duration JOURNEYS

train Completion

bus Medium

holiday Purpose

money/work etc.

etc.

JBN skilled .J'BN+ l

non-skilled TRAINING JBN+2

professional NO TRAINING

manual AGRICULTURAL JOBS

~tar.:teA]" INDUSTRIAL

agricultural

etc.

-23-

Is movement to another house in the same village

migration? If not, why is movement to the ne~t village

migration ?

I do not know the answer to the question "Who

is a Migrant (', but I do know the' way in which I would

go about defining different kinds of migrants, applying

much of what has been outlined above.

Migrants are PEOPLE, they move between PLACES,

they make JOURNEYS of different kinds, and they have

JOBS with differing characteristics. There may be

many other hierarchies which we could tnink of as

relevant - EDUCATION - for example, but for the moment

we will start with those I have indicated.

At the bottom pN of the people hierarchy we may

have descriptive words such as 'male, female, caste,

scheduled tribe, scheduled caste, school age, pensioner,

pensionable age, dependent, independent, married, single,

divorced, widowed'. If we wished we could combine these

holistically to define other categories: we could define N+I CHILD at P to be 'dependent, school age'.

The PLACES hierarchy starts at PLN with a list

of all places at the smallest scale that we can record -

a list of all villages, urban mohallas etc. places are

usually grouped in a partitional way: villages within

taluq~/tehsi$, tehsils within districts etc. But of course

we need here to have a coverset approach, as the Census . . N+I t' t of India fully recognlses, by grouplng at P no JUs

into taluq5, but also into township gr6ups oi" urban

agglomer.ations.

-24-

Migrants' JOURNEYS can be characterised by many

words. This time let us think of words at IN+l and N project back to J. rFrequency' would make us think of

Hourly, daily, X per year, seasonal, non-repetitive.

"Completion' would make us think of return and non-return.

'Duration' would make us think of 1 hour, 5 hours, (for

example), 2 days, 2 months. Obviously we will have to

look carefully to see if there are useful cut-off points

in this scheme. We can think of 'Medium', such as plane,

car, motor-bike, b~~, bicycle, foot, train, lorry, camel,

ass etc. We can think of 'Motivation' such as pleasure,

fear ,money, status, pilgrimage, education, dependent,

posting, marriage. Pleasure may make us wonder whether

we can project down even further to I N- l - to the level

of 'skiing, swimming, golf, fishing' etc.

There are many classifications of JOBS, and

some of those may be of use or relevance here. We might

use such words as 'skilled, non-skilled, professional,

manual, clerical, agricultural, light industrial, heavy

industrial, organized industrial, domestic industrial,

extractive' •

These thoughts are enough to begin to sketch out

how we might answer the question 'who is a migrant'.

First let us combine some of the words from JOURNEYS

level IN.

To define COMMUTING wie may need to say:

car

and/or bus

and/or train

and/or walk

and/or bike J r money J

+ l:-nd/ or s ta tu s

-25-

To define ITINERANT or TRAMP we may need to say:-

Daily + No return + r unemplyed 1 L~nd/or casual .employmen~~

N where I have used words not only from JOURNEY but also

from JOBSN. (The employment descriptors).

To define SEASONAL WORK MIGRANT we may need to ·'.say:-

plane

and/or train

and/or walk Seasonal + and/or car + money + return

and/or bike

and/or lorry

and/or camel and/or ass

To define a TOURIST/VACATIONE~ we may say lalmost exactly the same:

plane

and/or t:tain

and/or C&r

and/or b.tke

and/or l<::>rry

and/or cstmel

and/or a~s

+ pleasure + retrun

-26-

The only ~ifference here is that I have giv~n a motive

of pleasure not money, and have excluded walking from

the actual means of making the journey. (If we wish

to make sure we include walkers who merely reach their

initial start point by non-walking we simply have to

define it so). Here it .is manifestly clear that

Tourists and Seasonal Workers have much in common in terms

of shared elements: but in combination the change of one

element in the set - motivation - chan~es the meaning

of the whole.

Enpugh has been said already to show that there

is no simple and single answer to the question 'what

1S a migrant ?'. Using the words we have now defined

we might wish to include COMMUTERS and SEASONAL WORKERS

as Migrants, but exclude TRAMPS and VACATIONERS. So

now we have a scheme. looking rather like this:-

MIGFANl'

I Cannuter Seasonal \'brker movers for

permanent ~rk

seasonal money employment

............ dependents

non-repetitive

-27-

Note, that if all the data with regard to

individuals is recorded at the lowest level, and then

stor~d in a computer, we can keep changing de~initions

and re-run our computations using new concepts. The

categories and sub-categories of migration are not pre

ordained. They are d~~~~~d and u~ed by us for whichever

purposes seem sensible avenues of research.

What we have not so far said much about is other

hierarchies - PEOPLE, JOBS, PLACES. If for every

person in the data set all the data about these is

collected as well as the data about the JOURNEY, then

there are two ways in which this data may become of

importan~e. Firstly it may extend and augment the

definitions as we have already done: employment might be

part 0f the definitions of certain types of migrants;

dependency might exclude some persons from the category

of 'primary migrant' and place them in 'seconday migrant'.

The rural-u~ban migrant (PLACES) might be thought of

in a different category from the urban-urban. Secondly,

we may not think so much in terms of using these for

definition, as use them for counting the mappings between

the ditferent parts of the different hierarches: counting

how many SEASONAL migrants are agricultural, or how many

are urban-rural etc.

I conclude this example by a simple illustration

of calculating the percentage of migrants relating to

different combinations of data recorded for them.

-28-

Suppose we observe five persons, us~ng some

of the words from both the JOURNEYS and JOBS

hierarchies~

One: seasonal Strain T money M agriculture A

TWO; seasonal Scar C pleasure P non-worker NW

Threeiseasona1 Scar C money M hawking H

Four; non-repetitive NR walk W marriage MG

wife WF

Five; non-repetitive NR walk W money M servant ST

Each of these five can be represented by a polyhedron

whose vertics represent the elements describing each

person, as in Fig. 5.

If we put all five together there are some

areas of over lap. If now we count .the pe_rcentage

of migrants with different combinations of elements

starting with the greatest number of elements in

combination and going down singleton elements, we ge~

the list shown in Figure 60

This gives us a complete breakdown of the

migration pattern in this data set, enabling us to

ask simple questions and to see if the answers are

useful or not, and ~f not, to ask more complicated

questions.

This procedure has been elaborated at greater

length with respect oto broadcasting statistics in

Cha~~.-, Johnson and Gould (1986).

One Two •......... Three.&. .&. .&. ...... Four ••.•••• Five

MG tt ..

* .. * .. * * '" * * WF

• • ..

· · · · • · · · ·

29

. :c . . . . . p.' .N W···········

-30-

!. fIGURE 6

Comb-in.a.tioltO 06 M,[,gJta.;t.,i.oYl cf:iaJta.c.teJtMtic..6 I

8 T M A 20% ONE :8 T 20% mE 8 C pp NW 20% 'l'W) ·8 M 40% ONE ,THREE I 8 C M H 20% ~8 A 20% ONE NR W M3 WF 20% FOURI T A 20% ONE NR W M sr 20% FlVE~: T M 20% ONE

'j M A 20% ONE 8 T M 20% ONE ~: 8 C 40% TWJ,THREE 8 T A 20% ONE '18 P 20% 'l'W)

8 M A 20% ONE !8 NW 20% TW)

T 1)1 A 20% ONE ic P 20% 'IW)

8 p C 20% 'IW) 01 C NW 20% 'I'W) II 8 C NW 20% 'IW) II P NW 20% TWJ 8 20% 'IW)

II 20% THREE P NW 11 8 H

C P NW 20% 'IW) il c H 20% THREE 8 C M 20% TlffiEIIJ M H 20% THREE S C H 20% THREBl C M 20% THREE S M H 20% ~NR w 40% FaJR, FIVE C M H 20% THREI1t NR MG 20% FOOR NR W l'IG 20% FOUR I NR 'lJt.J' 20% FOOR NR MG WF 20% FooR':: w l'IG 20% FaJR NR MG WF 20% FCUR II W WF 20% FCUR ,I W M3 W 20% FCUR:I MG WF 20% FOUR NR W M 20% FIVE~: NR sr 20% FIVE NR M 8T 20% FIVE I:: NR M 20% FIVE NR W 8T 20% FIVE II W sr 20% FrJE W M ST 20% I sr 20% FIVE FIVE ,I M

~w M 20% FIVE

NR 40% FOUR, FIVE W 40% FOUR,FIVE C 40% 'lID, THREE 8 60% ONE, 'IW), THREE M e0% ONE, THREE ,FIVE

, T 20% ONE sr 20% FIVE H 20% THREE A 20% ONE P 20% 'I'W)

NW 20% TWJ VF 20% FaJJ<-M3 20% FooR

-31-

V" CONCLUSIONS

The clear and unambi.guous description of the real

world is the aim and foundation of man's social science

disc~pline.se Without orderly observations the word

! science r has t,o be dropped in favour of I op].nions' or

I hunch , or even 'prejudice'" Yet it is extremely

d.lff~cult '(.0 observe the soclal world in relat~vely

rlgorous ways.

Part of the problem lies with the soph-istication

and subtlety of the human ob~erve"f', Each of us is

equipped to handle complex problems of pattern recognition,

and complex problems of discrimination. Often we are

intuitively able to handle such complexity without

attempting to analyse it consciously. However, when we

need to collect data systematically, it becomes apparent

that instinct is not enough - we are too individualistic

and inconsistent. So we have to break the problems down

by some system of orderly observation. The system

proposed by At.kin is the best I have yet come across ..

It realises straight '.away that we often instinctively

use relations between sets: but that to record this we

must first work out what the sets are, and only then

observe the relatlons. It recognises that there are

hierarchies of sets, but that these hierarchies need

not be part1tional. It recognises that there are pseudo-

hieraLchies of aggregation, and real hierarchies of

power sets. There are many extensions to the ideas

demonstrated here: to analyses of the structure of

relatJ.ons, and to relating traffic (dynamics) to

backcloth (structure). But these can be explored

elsewhere. (G~uld~ Johnson, Chapman 19S().

PLACE OF BIRTH DATA' AND' L'IFETTME' M'IGRATION

Ronald Skeldon

The question on place of birth in population

censuses and surveys provide~ a basic direct way of

measuring migration. The' movement between place of

birth and place of enumeration is known as "lifetime

migration Il and a "lifetime inigrant 11' is def ined as

someone whO is enumerate'd' in a spatial unit other than

the one in which he or she was born.

Lifetime migration' is a fundamental measure of

population movement, altho'Ug'h now, in the second half

of the 1980s, it .is perhaps not thou~h~ so fundamental

as it once was considered to be. Ih' M'ahU:al' VI - the '" .. ....

Uhit'ed Nations I M'ahUal' on:- M'e;t'h'ods~ 'of' M'ea'sur'ing' Ih'te-rh'al -....._ .

Mi<Jratibn - published in 1970, place of birth is given

pride of place. Many analysts ,of migration would now

accord lifetime migration only a place of secondary

importance, with some considering that it is almost

useless from the point of view of policy-relevarit migration

analysis. This latter view is perhaps a little extreme

but certainly lifetime migration is not the ideal measure

of migration. However, for· certain reasons, it is

still a useful measure. In this chapter the advantages

and disadvantages of the. method will be examined to see

why it has changed from' ~ measure of migr.;ition to but

one measure of migration and the various uses of

birthplace data will also be examined.

-34-

BJ.rthp1'ace data have prov~ided the basis for some

of the classic studies of migration in India lMehrotraf 1974;

Davis 1951; Zachariah, 1964) and Indian analysts have been

in the forefront in the development of techniques to

analyse these data (Zachariah 1977; Nair 1985). Other

useful appraisals of the techniques employed ~n the anaLysis

of lifetime migration can be found in united NatJ.ons (.i970)(

Shryock ~ 'al. (1971), George (1970) and Arriaga (1977),

Let us consider first the disadvantages, The

first major disadv~ntage is that there is no time dimension.

Lifetime migration is the aggregate sum ot all movements

from birthplace to enumeration place for a population

irrespective of when the movements took ~~acee A move made

by an 80 -year-old man who moved 60 years ago w.1.l1 be

included with a move made by an 18-year-old student three

weeks before the census. Policy-makers are usually

interested in the present pattern of migration and lJ.fe£ime

migration is going to provideJpiased picture. We can try

to control this problem in two ways. First, we can examine

lifetime pattern by age group and make thl~easonab1e assumption that younger people are more likely to move and

so the lifetime flows of the 15-19 and 20-24 age cohorts

are given more weight in an analysis~ Secondly, and more

commonly, if a question on duration of residence is

included in the the census then we pan cross-classify the

flows from birthplace to place of enumeration by duration

of residence at place of enumeration: less than 1 year,

1-4 years, 5-9 years and so on.

However, this brings us to the second maJor

disadvantage with lifetime migration: it is a measure of

a single move from birthplace to place of enumeratlon~

A,n individual's migration may not have been so simple:

-35-

it could have involved several moves through intermediate

places between birthp1'ace and pilace of enumeration.

Perhaps even more important is the fact that much

migration is not captured by lifetime migration'at all.

We know that return migration is important in many

countries and particularly in the developing world. Data

from spectfic surveys have shown that there is a high

probability of a second migratimn being a return to place

of ,origin. Given this situation there are a large

number of people who may have spent considerable time

away from their birthplace who are classified as "non

migrants" or "never moved" under lifetime migration:

their place of enumeration is the same as their place

of birth.

One of the controls fOJ:jproblems:inherent ir{,the

lifetime migration data mentioned above was the inclusion

of a question on residence at place of enumeration.

However, the duration of residence data need not necessarily

refer to the migration from birthplace but to a movement

to the place of enumeration fromsome other place. This

makes any analysis of migrant/non-migrant differentials

(by, for example, age, educational or occupational status)

of dubious value from lifetime migration data.

Finally, lifetime migration does not take into , account the effect of mortality; it measures only those

who have survived at the destination to be enumerated

in the census. Hence, lifetime migration is not an

estimate of gross migration.

It is for the disadvantages outlined above that

migration analysts have relegated lifetime migration to

a secondary position in the study of the process of

migration. Given these disadvantages one might wonder

why we 8*lluld persist with its study. It does, however,

have two related advantages. First, birthplace data

-36-

are often the only migration-relevant data available

and, secondly, the question is easy to incorporate

in a census questionnaire: easy to ask ~nd almost as

easy for the ~espondents to answer. Let me emphasize

at this stage that while we are talking about "birthplace"

the question asked need not necessarily be "Where

were you born ?" but can be a variant - as in the case

of India - "Where was the usual place of residence

of your mother at tfue time of your birth ?" or "Where

were your parents usually living it the time of your

birth?" This question can simply be made culture

specific to produce a relevant question for each country~

To almost everyone, ~place of birth" is a meaningful

place which will be accurately remembered. This is an

important point in its favour as this is not the case

with some other methods of measuring migration such as

"Where were you usually living five years ago 7" which

is subject to problems of memory lapse. Hence, the

quality of birthplace data is lik~ly to be relatively

high.

Given that the question on birthplace is simple

we are likely to have a long sequence of birthplace

data. India is a classic case since information on

birthplace has been collected in thepountry since 1881.

There is also widespread spatial coverage of birthplace

data. Twenty-seven out of 34 countries in the Asia

Pacific region collected information on place of birth

in their 1980 round of censuses and this was by far

the most common migration-related question asked. For

the period 1955-65, the United Nations has information

on 109 national censuses taken around tpe world in which

87 recorded information on birthplace.

-37-

Hence, there are disadvantages and advantages

with the use of birthplace data and when we use such

data we must be aware of their strengths and weaknesses.

The ~ of Birthplace ~

(1) The measurement of origin-destination flows

The primary use·of,birthplace data is as a direct

measure of inmigration, outmigration and net-migration

for all the regions of a country. These can be

portrayed in a square origin-destination matrix. The

finer the network of spatial ~nits in a cQuntry, the

greate1the volume of migration that is captured by

the population census. To take an example from the

1981 censusof India, we find that when we use the

state as the migration-defining area 23.4 million people

would be defined as lifetime internal migrants (3.6

per cent of the total population) but if we use the

smallest place of enumeration as the migration-defining

unit, the number of migrants increases to 201.7 million

(or almost 30 per cent of the total population).

Despite the fact that the smaller units capture

more migration, we do not want the number of spatial

units to'. be too large or the origin-destination matrix

will be so complex that we cannot grasp the number of

flows involved. The number of spatial units should

then be IImanageable ll• Also, if the origin-destination

flows are going to be mapped we do not want them to

be so pr~fic that the result is a maze of intercrossing

flows and the main trends are not apparent at all.

For example, it would ",'._ not be desirable to have a

matrix of all the districts of India. state flows can

-38-

be complex enough. Specific matrices can be designed

for speci£ic purposes, although this may mean tedious

aggregration of the data where origin-destination flows

become too comp~ex.

The origin-destination flows can be simplified by

focusing on the net-flows, that is, the balance between

inmigration and outmigration for each spatial unit. It

must always be borne in mind that net-migration represents

the balance between two flows. It does not tell us any

thing about the volume of inflows or outflows but only

about the interchange of 'population between two areas.

It is a useful measure to' gauge the impact of ' migration

on the red:i·s·t'r'ibution of population. It must also be

remembered that there is no ,such person as a "net-migrant rt •

Net-migration is purely an aggregate measure to which

(individual) characteristics cannot be attributed. The

above clearly does not just apply to ~ifetime migration.

but to any direct method of measuring o~igin-destination

flows.

In the origin-destination matrixtha .number of

inmigrants must equaltbe .number of outmigrants - it is

a zero sum ga~e. In the analysis of internal migration

those 'who are born within the system and who have moved

out to other countries are not captured by the census -

and those who have moved into the system from other

countr~~are discounted and normally considered in a

separate series of tabulations and separate analysis.

Migration of "foreign-born Ii wi thin the system is thus

discounted in lifetime migration.

-39-

The data on the flows of inrnigrants and out

migrants can be subjected to the standard types o~

demographic analysis, by age, sex, marital statuS',

education and occupation. The migrant population is

often compared with the "non-migrant" or "immobile"·

population but we must remember, of course, that these

terms are misnomers. In comparing two censuses the

intercensal growth of "migrant" and IInon-migrant"

populations can be compared. A very detaile~ analysis

of lifetime mig.rants for India was made by Mehrotra (1974)

from the 1971 census.

For India, lifetime migration can be analysed

at the following levels: inter-country, inter-state,

inter-district and intra-district. The relevant

cat.egories are:

(a) Born here (place of enumeration);

(b) Born elsewhere in this district;

(c) Born in another district in this state (name of district);

(d) Born in another state (name of state);

(e) Born overseas (name of country).

Category (b) has only been identifiable in India since

1961

(2) The measurement of intercensal net migration

The second use of lifetime data is to measure

intercensal net-migration. Where the primary concern is

the role of migration as a component of population growth

or decline, knowledge of net-migration is often sufficient.

"Thus an estimate of net-migration is the most fundamental

migration measurement. For this reason, it occupies

-40-

a disproportionate share of migration researchers'

attention." (Bogue, Hinze and White, 1982) This is

very much a traditional demographer's view and I do

not think that many migration analysts today would

subscribe to ·;-_it. However, net-migration is an important

and valid aspect of migration research. It can, of

COUEse, be estimated without recourse to any migration

questions at all but these indirect techniques are

covered in another chapter and I will concentrate on

the estimation of net-migration using birthplace data.

The following discussion can be pursued at greater length

in United Nations' Ma'Itu:a1 VI (1970).

If 'Itand It+n are the inmigrants to a particular

spatial unit at two censuses at 't' and 't+n' and 0t and

0t+n are the outmigrants from that spatial unit at the

two censuses, then the net-migration that has occurred

dunng the intercensa1 period can be calculated thus:

Net M = (1t +n - 0t+n) - (SIlt _ SO) ° t

Where SI and So are the intercensal 'surviva1 ratios

which allow us to estimate how many of the inmigrants

and outmigrants of the earlier census will survive through , to therater census.

The formula is more commonly presented as:

Net M = (It +n - SIlt) + (SOOt - 0t+n)

The problem with this formula is to estimate S1 and SO·

There are various methods:

a) Overall census survival ratio, that is,

assume SI=So =ST;

b) Area-specific census survival ratios;

c) Age-specific censusfurviva1 ratios.

-41-

The aim of these procedures is to take mortality into

account; that is,t)\e mortality of the inmigrants to and

the outmigrants from a spatial unit during the intercensal

period. If mortality is not taken into account, the

net-migration over the period will be underestimated.

Hence, the assumption is that the migrants, both in and

out, at time t are stable, and the only factor to affect

them will be mortality. Implicit in this approach is

the idea that migratlon is a simple linear process:

a movement from A to B.· This is not the case. Mortality

is but one factor - and I would regard it as not the most

important factor- in the attrition of It anq 0t. On

movement ~nd return movement are more important. Migrants

also tend t+e youn:g adults and while certainly subject

to mortality this is not likely to be the most significant

factor in the reduction of It and 0t.