Prisons as Places of Hope and Transformative Learning

-

Upload

oregonstate -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of Prisons as Places of Hope and Transformative Learning

International Journal of Appreciative Inquiry

February 2012

Volume 14 Number 1ISBN 978-1-907549-08-3

Feature Choice: Gervase Bushe on the Foundationsof Appreciative Inquiry

Appreciative Empathy

Prisons as Places of Hopeand Transformative Learning

Inside:

Virtual SOARing in a School of Nursing

Building Vibrant Communities across Southeast Texas

Me, Myself and AI

AI Resources:Books and articles on AI and Learning

An Appreciative Approach to Learning

Guest Editors: Jan Reed, Marianne Tracy and Lena Holmberg

Applying AI in a Constrained Business Setting

The Positive Core of Engagement

AI Research Notes:AI 2.0 Transformational Research

Learning is the Spark of Transformation

February 2012

International Journal of Appreciative Inquiry

Inside:

Back Issues at www.aipractitioner.com

AI Practitioner

Prisons as Places of Hope and Transformative Learning by Michelle InderbitzinEducation as a scarce but treasured resource in state prisons.

21

4 Learning is the Spark of Transformation by Jan Reed, Marianne Tracy and Lena HolmbergAI as a positive learning experience, helping learners and teachers to feel valued

Virtual SOARing in a School of Nursing: Creating Space for Emergent Design by Kristen CrusoeA nursing program adapts to change using a ‘virtual SOAR’ process

27

AIP February 12 Learning is the Spark of Transformation

41 Neighborhood Centers’ Road to Building Vibrant Communities across Southeast Texas by Jen Hetzel Silbert and Laura TimmeA human service agency’s persistent efforts to spark AI learning catalyzes a ripple effect of positive change from the inside out

An Appreciative Approach to Learning: Making It Real and Making It Work by Pamela Lupton-BowersThe four essential factors in appreciative learning

33

Me, Myself and AI by Paul Swart and Rob VinkeWhat is it inside ourselves that makes us effective AI practitioners?

46

In each issue, a leading AI practitioner will present a topic of their choice8 Feature Choice by Gervase Bushe Foundations of Appreciative Inquiry: History, Criticism and PotentialA new feature article tracing the development of AI, through the controversies and the potential of the discipline

AI Practitioner February 2012

International Journal of Appreciative Inquiry

Inside continued:

Back Issues at www.aipractitioner.com

70 Appreciative Inquiry Research Notes by Jan Reed and Lena HolmbergAI 2.0. Transformational research using the National Peace Academy as a unique opportunity to obtain cross-sectional insights

80 About the May 2012 IssueDavid Cooperrider, Lindsey Godwin, Brodie Boland and Michel AvitalThe Appreciative Inquiry Summit: Explorations into the Magic of Macro-Management and Crowdsourcing

IAPG Contacts and AI Practitioner Subscription Information81

73 Appreciative Inquiry Resourcesby Jackie Stavros and Dawn DoleBooks and articles on AI and learning

AIP February 12 Learning is the Spark of Transformation

57 Applying AI in a Constrained Business Setting: A Practical and Flexible Framework by Gary M. CookWe don’t always have the ability to create the exact conditions we would like for our AI work with clients

The Positive Core of Engagement: The Project SOAR and A.L.P.H.A. Stories by Noel E. K. TanHow Positive Change methods like Appreciative Inquiry and Narrative Practices were deployed to help re-engage 15-year-olds

64

51 Appreciative Empathy: New Frameworks for New Conversations by Bob Tschannen-MoranKnowing how to fully appreciate the feelings and needs of others holds the key to AI success

AI Practitioner February 2012

21

Volume 14 Number 1 ISBN 978-1-907549-08-3

More Articles at www.aipractitioner.com

Michelle Inderbitzinstudies prison culture, juvenile justice and transformative education. She has published papers in journals including Journal of Offender Rehabilitation and Criminology & Public Policy. On faculty at Oregon State University since 2001, she teaches classes and volunteers in Oregon’s maximum-security prison for men, and its juvenile correctional facility for girls.Contact: [email protected]

ABSTRACT

Education is a scarce but treasured resource in state prisons. Appreciative Inquiry allows us to imagine prisons as places of hope rather than retributive punishment. This article discusses transformative learning in prison and encourages readers to imagine a system where prisoners are encouraged to engage in college courses and work toward redemption and rehabilitation rather than simply ‘doing time’.

Prisons as Places of Hope and Transformative Learning

As a sociology professor, it is a joy and privilege to be able to share new perspectives, understanding and opportunities with students. Perhaps surprisingly, the most powerful learning I have participated in and witnessed has not happened on a university campus; instead, the transformative power of learning has been most vividly illustrated within the walls of a maximum-security prison.

Prisons may seem designed to strip inhabitants of their humanity, but some individuals discover new hope and strength during their incarceration. Some manage to find the freedom and will to become the men and women they aspire to be while serving time in state prisons. Education acts as one important lifeline for individuals spending years of their lives in prison. Inside or inmate students struggle through readings, homework and difficult concepts, and, in doing so, become role models for their children and their fellow prisoners. They may never be able to erase their past transgressions, but they work to build new skills and hope to leave a legacy other than pain and loss.

Participating in college courses offers individuals inside prison a new identity and an alternative peer group. They can choose to embrace the label of student rather than that of convict or inmate; they are able to define themselves as deliberate learners who choose to spend their time and efforts on self-improvement rather than hanging out on the yard and getting into trouble. As these individuals grow and change, the culture of the prison may slowly change, too. Imagine if we could reframe the purpose of prisons to truly focus on rehabilitating offenders, offering them the tools to become different and better men and women while serving their state-imposed sentences. Prisons could become places of hope, learning and redemption rather than the expensive, punitive warehouses they often are today. Investing in education is undoubtedly our best chance to spark transformation and positive change within state prisons.

AIP February 12 Inderbitzin: Prisons and Transformative Learning

AI Practitioner February 2012

22

Volume 14 Number 1 ISBN 978-1-907549-08-3

More Articles at www.aipractitioner.com

Appreciative Inquiry and prison researchAppreciative Inquiry (AI) is a rarely used but beneficial perspective for research on and in prisons. While prison research often focuses on institutional problems, AI encourages social actors ‘to reflect explicitly upon their most positive experiences’ (Liebling, Price, and Elliott, 1999: 75). Researchers are encouraged to ask good questions, ‘those that help to enlarge possible worlds and possible ways of being in relationship’ (Hosking and McNamee, 2007:12), and ‘the aim is to dream or envision how the organization ideally might look in the future’ (van der Haar and Hosking, 2004: 1019).

Prison educators and their inmate students implicitly understand both the underlying logic of Appreciative Inquiry and the power of transformative education. Prison may seem an unlikely place to expand one’s mind, one’s horizons and one’s social circle, but some incarcerated individuals seek out the opportunity to do just that. They find a way to use the prison setting as their own informal university. As one inmate student explained to his philosophy professor:

‘Since I’ve been in prison, I’ve met people with sophistication…you have college graduates and people from different parts of the world. We meet here and get a chance to rest and get out of our immediate world, and we can think about things we couldn’t on the street.’

It’s what every university would wish to be: a cosmopolitan atmosphere, a diverse student body, the leisure for study and free exchange of ideas (Leder, 2000: 83).

Imagining change and building an education program in a penitentiaryToday’s correctional facilities have a strong contingent of self-made poets, artists, musicians, politicians and scholars in their midst. The deep motivation of individuals serving years in confinement can triumph over the lack of materials, time and teachers in correctional facilities. At the same time, there are many individuals in prison who had terrible experiences in schools while they were growing up and they lack confidence in their ability to learn. I’ve taught both types of inmate students – the confident and the beginners – and it is extremely rewarding to witness their barriers come down as they focus on educational goals rather than the drudgery of prison life.

I began teaching in state prisons through the Inside-Out Prison Exchange Program.1 The program brings university (outside) students into correctional facilities to share a college class for a full term with inmate (inside) students. I was the first to teach this type of class in the maximum-security prison in my state; the inside students who signed up for the first class were initially cautious, but eager for new opportunities and willing to give the class and the program a chance.

To be eligible to participate, the inside students are required to have earned a high school diploma or equivalency and to have no disciplinary infractions within the prison for at least 18 months. Their academic skill levels vary, but their motivation does not. Inside students very quickly realized that participating in this program was a rare opportunity (each class has approximately 15 inside students out of a prison population of approximately 2200); they valued the interaction with outside students and the chance to learn new perspectives

1 http://www.insideoutcenter.org/home.html

‘I came to prison as a 17-year-old boy, but now I not only have the tools to leave as a man, but an educated one at that.’ Inside student serving a 25 year prison sentence

AIP February 12 Inderbitzin: Prisons and Transformative Learning

AI Practitioner February 2012

23

Volume 14 Number 1 ISBN 978-1-907549-08-3

More Articles at www.aipractitioner.com

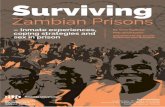

Left: Sign welcoming travelers to the USA at the metro station in Reagan National Airport in Washington DC. Right: Hands of Inside and Outside students

and freely express their opinions. They enrolled in the course without receiving college credit, but the experience was a rewarding one; the initial students requested more courses and encouraged their friends in the prison to get involved.

Over the past five years, the Inside-Out program has grown in the state and the maximum-security prison now hosts three or four classes, each with a different instructor, per year. Additionally, shortly after the successful introduction of the Inside-Out program, a private donor began funding community college courses in the prison. Those courses offered inside students the chance to earn an Associate of Arts degree: a new credential to take out into the community upon release. The education staff members in the prison celebrate earned AA degrees with formal graduation ceremonies that the inside students and their families can attend – it’s a goal to strive for, a bit of normality, and a proud moment for everyone involved.

Education as a transformative experience in prisonCollege programs in prisons present an interesting paradox: deep involvement in education implicitly encourages questioning, while the prison setting requires obedience to the strict rules of the institution. While uncomfortable at times for participants, this is consistent with a transformative pedagogy ‘that relentlessly questions the kinds of labor, practices and forms of production that are enacted in public and higher education’ (Giroux, 2001, p. 18). And really, who needs transformation more than the criminal?

As a society, we have branded the men and women in prison unworthy or incapable of living amongst us. Education is one of the only options available that offers convicted felons a legitimate chance to make difficult choices and to improve their chances for success when re-entering the community. As one of my students serving a 25-year sentence explained: ‘I came to prison as a 17-year-old boy, but now I not only have the tools to leave as a man, but an educated one at that’ (Anderson, 2010).

Education offers hope in prison ... a salvaged future can thus redeem past and present.

AIP February 12 Inderbitzin: Prisons and Transformative Learning

AI Practitioner February 2012

24

Volume 14 Number 1 ISBN 978-1-907549-08-3

More Articles at www.aipractitioner.com

Ray, another of my former inmate students who served nearly thirty years, offered an inside and personal view of the meaning of education in prison. Thinking back to the 1980s, he remembered educational programs in prison as:

‘havens away from the concrete and steel of the cell, the loud bells ringing out schedules, the mass of voices and swarms of movements. They were havens of guidance and education where the inmate could work toward changing his past confusion and shallowness into clarity and insight. God, I was so thankful…these places were filled with men, days and evenings, who were serious about turning their lives around.’

For Ray, working on his own rehabilitation was ‘a beautiful and horrifying journey.’ He excelled in the college program and even began working on a Masters degree through correspondence courses. After prisoners were deemed ineligible for Pell grants, Ray felt like he was ‘racing just ahead of a monstrous, punitive storm devouring everything in its path that offered opportunity and hope.’ He felt despair as laws changed, the havens crumbled and young people faced their prison sentences with very little hope for education or transformation. He was a member of the first Inside-Out class and he became an avid supporter of the program and the possibilities it offered to inside students.

Imagining the possibilities of higher education in prisonOver the past twenty years, there has been strong resistance from the American public to fund college programs in prison. In spite of the fact that recidivism rates for inmates who participate in college programs are consistently lower than those of non-students, there is a clear sense that the community does not want to reward criminals for their bad behavior (Page, 2004), and that prison sentences should be about punishment rather than self-improvement.

Inmate students have often led particularly difficult lives prior to their incarceration. Their experience in prison often harms their psyches and self esteem and further diminishes their life chances. But, does time in prison necessarily have to be damaging to inmates? Imagine if we as a society chose to re-cast the purpose of prisons. How would our ideas about crime and punishment change if time served in a correctional facility was thought of as ‘redeeming time’ rather than lost time?

Appreciative Inquiry and opportunities for higher education are perhaps our best possibilities for transforming prisons, changing them from punitive institutions into redemptive entities.

AI helps us transcend what we have previously known, and the way we have known it, by creating new meaning in relationship with others through storytelling. The focus of our storytelling is intentional: we talk about what we want to amplify and grow. We know from our experience that what we choose to talk about is consequential (Wasserman, 2005: 41).

As a novice AI practitioner emboldened by my belief in the better possibilities of prisons, I will be imagining and talking about the power of transformative education behind bars for many years to come. I will continue to collect stories of redemption and change from my inside students and to think creatively about how to expand educational programming in state prisons. This, of course, is not without its challenges. While implementing innovative teaching and pedagogy

AIP February 12 Inderbitzin: Prisons and Transformative Learning

T-shirt for the Inside-Outside program

AI Practitioner February 2012

25

Volume 14 Number 1 ISBN 978-1-907549-08-3

More Articles at www.aipractitioner.com

is often difficult on college campuses (Inderbitzin and Storrs, 2008), the bureaucratic hurdles and scrutiny are heightened when college classes take place in high security prisons. With greater struggle and risk, however, also comes great reward: I have never had more motivated or appreciative students than those in my prison classes.

I have been the first college teacher for dozens of inside students. Young and old, serving life sentences or close to their release date, I have watched them grow and change as they immerse themselves in reading, studying, listening, considering options and weighing alternatives. Their success in the first class shows them they are capable students with a point of view and a story to tell, and it often stirs their interest in earning a college degree. Through their efforts, incarcerated students earn rare and precious glimpses of freedom; they find an opportunity for growth within the stifling environment of a correctional facility.

Transforming futures and culturesSimply put, education offers hope in prison. For the individuals, ‘A salvaged future can thus redeem past and present’ (Leder, 2000: 95). While some of my inside students will never get out of prison, they work hard to be leaders in the institution and role models for their families on the outside and peers on the inside. Several of my inside students have recently been released from prison. With their hard-earned Associates degrees in hand, they have enrolled immediately in state universities, confident after their educational accomplishments in the prison that they have the ability to learn and keep up. It is a more promising future than they could have imagined before taking college classes in prison.

As the critical mass of inmate students grows, the institution also slowly begins to change. One of my inside students offered an example of a surprising unintended consequence of sharing the college experience with a diverse group of inmates: ‘I have seen racial lines broken through these classes, men getting together in prison throughout the week, talking about the material, learning together [and] developing social bonds,’ (Anderson et al., 2010: 84-85). The picture he paints of tough inmates poring over textbooks and essays together is a welcome change from the concern over gangs and violence that often permeate maximum-security prisons like the one in which he resides.

Alison Liebling, one of the few criminologists to practice Appreciative Inquiry, has suggested that: ‘The special and complex moral environment of the prison makes AI especially relevant’ (Liebling, Elliott and Arnold, 2001: 161). I would further argue that AI will reveal education as our best hope of embracing possibility and changing both the culture of prisons and the expectations of and about former inmates.

My experience teaching college classes in a maximum-security prison suggests that the power of education is the most vital tool we have to encourage change within the individuals in prisons and to begin to transform the larger culture of the institution. Shifting the focus from simply ‘doing time’ to ‘redeeming time’ by participating in educational programming can help us to more generally re-think the purpose of prisons and punishment. If we can make this leap – using education as a tool to imagine new possibilities for dealing with criminal offenders– our prisons and the larger society will undoubtedly be better for it.

AIP February 12 Inderbitzin: Prisons and Transformative Learning

The special and complex moral environment of the prison makes AI especially relevant, Alison Leibling, criminologist and AI practitioner

AI Practitioner February 2012

26

Back to Table of Contents

Volume 14 Number 1 ISBN 978-1-907549-08-3

More Articles at www.aipractitioner.com

ReferencesAnderson, J. (2010) ‘The Education of a Man: An Inside Student’s Perspective,’ The Inside-Out Center Newsletter, 1(2): 5.

Anderson, J., Hall, B., Spencer, D. and Sanders, D. (2010) ‘Essays from Inside,’ Contexts, 9: 84-85.

Giroux, H. (2001) ‘Pedagogy of the Depressed: Beyond the New Politics of Cynicism.’ College Literature, 28 (3), 1-33.

Hosking, D. M. and McNamee, S. (2007) ‘Back to Basics: Appreciating Appreciative Inquiry as Not ‘Normal’ Science.’ AI Practitioner, November 2007, 12-16.

Inderbitzin, M. and Storrs, D. A. (2008) ‘Mediating the Conflict Between Transformative Pedagogy and Bureaucratic Practice., College Teaching 56(1): 47-52.

The Inside-Out Center, http://www.insideoutcenter.org/home.html

Leder, D. (2000) The Soul Knows No Bars: Inmates Reflect on Life, Death, and Hope. New York: Rowan & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Liebling, A., Elliott, C., and Arnold, H. (2001) ‘Transforming the Prison: Romantic Optimism or Appreciative Realism.’ Criminology and Criminal Justice, 1(2): 161-180.

Liebling, A., Price, D., and Elliott, C. (1999) ‘Appreciative Inquiry and Relationships in Prison.’ Punishment and Society, 1(1): 71-98.

Page, J. (2004) ‘Eliminating the Enemy: The Import of Denying Prisoners Access to Higher Education in Clinton’s America.’ Punishment and Society, 6(4): 357-378.

Van der Haar, D. and Hosking, D. M. (2004). ‘Evaluating Appreciative Inquiry: A Relational Constructionist Perspective.’ Human Relations, 57(8): 1017-1036.

Wasserman, I. C. (2005). ‘Appreciative Inquiry and Diversity: The Path to Relational Eloquence.’ AI Practitioner, August 2005, 36-42.

AIP February 12 Inderbitzin: Prisons and Transformative Learning

AI Practitioner February 2012

81

Volume 14 Number 1 ISBN 978-1-907549-08-3

More Articles at www.aipractitioner.com

AI Practitioner

IAPG Contacts and AI Practitioner Subscription Information

ISSN 1741-8224

International Advisory Practitioners Group IAPG

Members of the International Advisory Practitioners Groupworking with AIP to bring AI stories to a wider audience:

Druba Acharya, Nepal

Anastasia Bukashe, South Africa

Gervase Bushe, Canada

Sue Derby, Canada

Sara Inés Gómez, Colombia

Lena Holmberg, Sweden

Joep C. de Jong, Netherlands

Dorothe Liebig, Germany

John Loty, Australia

Sue James, Australia

Maureen McKenna, Canada

Liz Mellish, Australia

Dayle Obrien, Australia

Jan Reed, United Kingdom

Catriona Rogers, Hong Kong

Daniel K. Saint, United States

Marge Schiller, United States

Jackie Stavros, United States

Bridget Woods, South Africa

Jacqueline Wong, Singapore

Margaret Wright, United Kingdom

AIP SubscriptionsIndividualsNGOS, students and community groupsSmall organisationsUniversity/Research Institutes Large organisationshttp://www.aipractitioner.com/subscriptions

Back Issues and Articleshttp://www.aipractitioner.com/issueshttp://www.aipractitioner.com/articles

Change of subscriber detailshttp://www.aipractitioner.com/customer/account/login

Publication Advertising/SponsorshipFor the advertising rates, contact Anne Radford.

Disclaimer: Views and opinions of the writers do not necessarily reflect those of the publisher. Every effort is made to ensure accuracy but all details are subject to alteration. No responsibility can be accepted for any inaccuracies.

Purpose of AI PractitionerThis publication is for people interested in making the world a better place using positive relational approaches to change such as Appreciative Inquiry.

The publication is distributed quarterly: February, May, August and November.

AI Practitioner Editor/PublisherThe editor-in-chief and publisher is Anne Radford. She is based in London and can be reached at [email protected]

The postal address for the publication is:303 Bankside Lofts, 65 Hopton Street, London SE1 9JL, England.Telephone: +44 (0)20 7633 9630Fax: +44 (0)845 051 8639ISSN 1741 8224

Shelagh Aitken is the issue editor for AI Practitioner. She can be reached at [email protected]

AI Practitioner © 2003-2012 Anne Radford

Back to Table of Contents