Preparing Writing Teachers to Teach Vocab & Gr of Academic Prose- Averil Coxhead & Pat Byrd

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of Preparing Writing Teachers to Teach Vocab & Gr of Academic Prose- Averil Coxhead & Pat Byrd

Preparing writing teachers to teach the vocabulary

and grammar of academic prose

Averil Coxhead *, Pat Byrd

School of Language Studies, Massey University Palmerston North, Private Bag 11 222,

Palmerston North, New Zealand

Abstract

Over the years, substantial shifts in theory, belief, and practice have occurred in the teaching of language,

specifically vocabulary, grammar, or their combination in lexicogrammatical features of a language as part

of the writing class or curriculum (Paltridge, 2004; Reid, 1993, 2006). Much of the instruction in L2 writing

for adult learners who are preparing for degree study in an English-medium college or university focuses on

academic writing; one result of this interest in academic writing is a growing body of research data that

provides insights into the language of academic discourse and the various registers that make up that

discourse, demonstrating that vocabulary and associated grammar characterize particular discourse types

(Biber & Conrad, 1999, 2004; Biber, Conrad, & Cortes, in press, Biber, Conrad, Reppen, Byrd, & Helt,

2002; Coxhead, 2000; Schleppegrell, 2004; Schleppegrell, Achugar, & Orteiza, 2004; Schleppegrell &

Colombi, 2002). Through knowledge of that literature and the development of skill at analyzing particular

examples of academic writing, teachers can learn to identify the language that their students need to become

fluent writers of various types of English academic prose. In this article, we review recent scholarship on the

nature of the vocabulary and grammar that characterize academic writing. In addition to the discussion of

published research and theory on language-in-use focused on academic prose, we also include a selected

listing of web-based resources to be used for teacher development. We also suggest practical ways that

teacher educators can bring the study of academic language into the preparation of writing teachers to teach

the vocabulary and grammar of academic prose.

# 2007 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Applied corpus linguistics; Language-in-use; Lexicogrammatical features of academic writing; On-line

resources; Teacher development

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com

Journal of Second Language Writing 16 (2007) 129–147

* Corresponding author. Tel.: + 64 6 356 9099x7923; fax: +64 6 350 2271.

E-mail address: [email protected] (A. Coxhead).

1060-3743/$ – see front matter # 2007 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.jslw.2007.07.002

Teaching vocabulary and grammar in the EAP composition class

Over the years, substantial shifts in theory, belief, and practice have occurred in the teaching of

language, specifically vocabulary, grammar, or their combination in lexicogrammatical1 features

of a language as part of the writing class or curriculum (Paltridge, 2004; Reid, 1993, 2006). The

place of language instruction in the writing classroom remains unclear for many teachers who

want to teach composition skills while faced with evidence in student writing that many of their

students have yet to develop the linguistic resources necessary for communicative competence as

academic writers. Part of the lack of clarity about the status of language teaching in the

composition class may result from limited access to information about language-in-use, the

approach to language analysis used in many corpus-based and functional studies of grammar/

vocabulary where the focus is on ways that language is actually used for communication (for

more information on this approach to linguistics, see Biber, Conrad, & Reppen, 1998; Stubbs,

1993). Language-in-use provides insights not simply on what is possible with grammar/

vocabulary but on what is actually done when a language is used for a particular type of

communication. For example, the verb require (which is frequently found in academic writing)

can be used in a number of different ways: simple present tense, simple past tense, past participle

as an adjective, past participle in the passive or modified to become the noun requirement(s).

Require itself is often a word that teachers assume their higher proficiency students know, but the

various inflected2 forms of the word are not likely to be as well known as the base word itself, just

as nouns and verbs are more well known by most learners than adverbs and adjectives (see

Schmitt & Zimmerman, 2002 for information on student knowledge of inflectional forms). In

actual use in academic writing, the past participle required is overwhelmingly selected over all

the other forms of require and is used for passive verbs and almost never for simple past tense

statements. Additionally, required has two possible complementation3 patterns: required

that + clause or required + infinitive. In academic writing, the great majority of uses involve the

infinitive as in Every company is required to make a statement in writing (Coxhead, Bunting,

Byrd, & Moran, in press).

Much of the instruction in L2 writing for adult learners who are preparing for degree study in

an English-medium college or university focuses on academic writing; one result of this interest

in academic writing is a growing body of research data that provides insights into the language of

academic discourse and the various registers that make up that discourse, demonstrating that

vocabulary and associated grammar characterize particular discourse types (Biber & Conrad,

A. Coxhead, P. Byrd / Journal of Second Language Writing 16 (2007) 129–147130

1 Throughout the article, definitions are given for terminology often used in corpus-based linguistic analysis of English

grammar. These definitions are provided at the request of colleagues who reviewed drafts of this chapter who have not

recently studied linguistics. They are offered in the spirit of help for colleagues who would like special information and

with the hope that those who do not need the information will patiently skip over the information they do not need. For

example, lexicogrammatical refers to frequently occurring combinations of words and grammar, where a particular word

generally requires particular grammar. That is, the verb required can be followed either by an infinitive or by a that-clause.

However, the most commonly used combination involves required followed by an infinitive. The combination of required

and the infinitive is a lexicogrammatical pattern.2 Inflected, inflection, and inflectional are used to describe the various forms of a word that are created by grammatical

processes. For example, the base form of the verb is require. That verb has the following inflected forms: requires,

required, requiring.3 Complement and complementation are used by linguists and grammarians to describe the kinds of words, phrases,

and/or clauses that are needed to complete a word. The complements for verbs can be infinitives or that-clauses or other

required sets of words.

1999, 2004; Biber, Conrad, & Cortes, 2003; Biber, Conrad, & Cortes, 2004; Biber, Conrad,

Reppen, Byrd, & Helt, 2002; Coxhead, 2000; Schleppegrell, 2004; Schleppegrell, Achugar, &

Orteiza, 2004; Schleppegrell & Colombi, 2002). Through knowledge of that literature and the

development of skill at analyzing particular examples of academic writing, teachers can learn

how to identify the language that their students need to become fluent writers of various types of

English academic prose. Two dangers are inherent in this aspect of teacher development: (a)

native speaker and advanced L2 intuitive judgments can be unreliable guides to the language

actually characteristic of academic writing (Folse, 2004; Hunston, 2002; Sinclair, 1991); (b)

materials developers, curriculum designers, and teachers need to be aware of the difference

between language specific to a particular sub-area of academic study or even to a particular

reading passage; otherwise, the vocabulary selected for study can focus on items of limited

usefulness rather than on words and word families4 that are broadly used in many different

academic fields (Coxhead, 2000; Coxhead & Nation, 2001). To provide teachers with the

resources needed for accurate and effective decisions about the language content of English-for-

Academic Purposes (EAP) writing classes, teacher educators have access both to web-based

teacher-support sites (e.g., The Compleat Lexical Tutor at hhttp://132.208.224.131/i) and to a

growing body in print format of empirical data and theory building on academic language and on

the teaching and learning of that language (e.g., Biber, Johansson, Leech, Conrad, & Finegan,

1999; Byrd & Reid, 1998; Corson, 1995, 1997; Cotterall & Cohen, 2003; Coxhead, 2006; J.

Flowerdew, 2003; L. Flowerdew, 2003; Jabbour, 2001).5

In this article, we review recent scholarship on the nature of the vocabulary and grammar that

characterize academic writing. In addition to the discussion of published research and theory on

language-in-use focused on academic prose, we also include a selected listing of web-based

resources to be used for teacher development. We also suggest practical ways that teacher

educators can bring the study of academic language into the preparation of writing teachers to

teach the vocabulary and grammar of academic prose.

The place of language instruction in the EAP writing classroom: vocabulary of

academic writing

Knowing a word involves many different aspects of knowledge (Nation, 2005). Additionally,

native speakers of a language have varying levels of knowledge of vocabulary items, from high

frequency items we recognize in reading and listening and use regularly in our everyday speaking

and writing to more specialized lexical items we use only to convey particular meanings.

Paradigm and notwithstanding, for example, are unlikely candidates for everyday conversation

A. Coxhead, P. Byrd / Journal of Second Language Writing 16 (2007) 129–147 131

4 Linguists use several different approaches to the grouping of words into sets of related words. For example, a set

might be limited to the forms associated with a particular part of speech with the various forms used as verbs in one

category and the various forms used as nouns in another category. These part-of-speech based categories are often labeled

with the term lemma. For example, the lemma for the verb walk would include walk, walks, walked, and walking. A word

family is a much more inclusive grouping that includes all of the various part of speech forms along with other closely

related words that might have different affixes. For example, in the Academic Word List (Coxhead, 2000) the word family

for require includes the inflected forms of the verb and a noun: required, requires, requirements, require, requirement,

requiring. In that same set of academic words, the word family for respond includes verb forms, the singular and plural of

the related noun, and an adjective: respond, responded, respondent, respondents, responding, responds, response,

responses, responsive.5 Such resources are exemplified by the multiple publications and web-based materials that build on the word families

in the Academic Word List (Coxhead, 2000, 2006; Haywood, 2007b).

but occur reasonably often and widely in written academic English (Coxhead, 2000). Corson

(1995, pp. 180 and 181) calls this academic language with its restricted use a lexical bar or barrier

that students need to transcend in order to move successfully from everyday ways of expressing

meaning to the specialized, ‘‘high-status’’ academic language. Just as native speakers of English

have widely varying knowledge of vocabulary, especially academic vocabulary, second language

users also have varying levels of knowledge of lexical items; differences are a result of both

proficiency level and of the natural variance in the knowledge of each individual learner (Hoey,

2002).

Furthermore, knowledge needed for the use of words in listening, speaking, reading, and

writing is not all the same (Nation, 2001). Knowing a word to use it in writing involves at least

understanding and expressing meaning in a range of contexts, spelling (and pronunciation for

some people so that they might guess how to spell a word), regular grammatical patterns of

occurrence, collocations or words that commonly occur with the word, word families, formality,

word parts, and synonyms and opposites. The complex learning that lies behind knowing how to

use words in writing does not happen by chance but needs to be planned (Laufer, 2005) by the

teacher and by the learner. Both must be aware that a single encounter with a new word will not

often lead to learning to use the word in writing because the development of vocabulary

knowledge requires multiple encounters so that students build up their knowledge and skill at

using words over time (Nation, 2001).

The Academic Word List (AWL) (Coxhead, 2000) is an example of corpus linguistics research

of language-in-use focused on academic writing that was carried out with teachers and learners in

mind. The AWL can guide the selection of academic words worth their limited time for learning

and teaching. The AWL is a list of 570 academic word families6 that are widely used across many

disciplinary areas; that is, these are not the technical, specialized words of particular fields of

study. The list is divided into sublists based on frequency and covers approximately 10% of any

academic text (with most of the words in any text coming from the most common 2000 words of

English along with a small assortment of more technical words). That is, on average, 10 words in

every 100 in an academic text may occur in the AWL. For more on how the AWL was devised, see

Coxhead (2000).

The nature of the AWL has at least three major implications for teacher educators in academic

writing. First, the AWL contains vocabulary that is primarily academic in nature. While AWL

words can also occur in newspaper writing (with a coverage of around 4.5%), these words are rare

in fiction (about 1.4%). Because reading and analysis of fiction will not provide access to

appropriate vocabulary for students who need to become academic writers, teachers of academic

writing should include study of academic texts in the writing classroom. Second, over 80% of the

list is Graeco-Latin in origin. This figure indicates that learners from a Romance language

background will have a substantial advantage over learners with other first languages (Coxhead,

2006, p. 6). Third, the specialized nature of academic vocabulary and its origins in Latin and

Greek support Corson’s (1995) idea of a lexical bar that can block the success of many students as

they work to become effective academic writers, making instruction in vocabulary important in

A. Coxhead, P. Byrd / Journal of Second Language Writing 16 (2007) 129–147132

6 Studies of vocabulary generally focus on two major issues: frequency and range. Frequency tells us which words are

more commonly (or more rarely) used. Range tells us about how widely the words are used in different areas. For

example, required is highly frequent in academic texts and is used widely in many different disciplinary areas, while a

term like counter transference is likely to be known only by specialists in psychotherapy and not widely used outside that

disciplinary area.

EAP academic writing courses. Currently the AWL is available as a list of words only. At the time

of writing, several research projects are underway to investigate formulaic sequences or lexical

bundles of the AWL. Simpson and Ellis (2005) are working on an academic formulas list, and

Coxhead et al. (in forthcoming) are looking at the common collocations and recurrent phrases of

the AWL. As yet, more specialized word lists of academic subject areas such as economics or

biology have not appeared in the literature of EAP.

Writing for academic purposes involves specialized knowledge of academic genres (see

Hyland, 2007) and of the academic language required by those genres. Academic writing

does not exist as a task on its own but is inextricably linked to the reading of academic texts.

Both skills are oriented to text (Jabbour, 2001, p. 291), with reading used by academic writers

for purposes that are considerably different from those in other types of reading; that is, as part

of the academic writing process, materials are read for ideas, data, and language to be used in

the written product that results from the process; reading is not just for understanding or for

pleasure. Additionally, in the L2 writing class, reading provides learners with language

development opportunities and scaffolding as well as meaning and ideas to use in their own

writing.

Academic reading texts, such as journal articles and textbook chapters, tend to be long and

demanding in their content and in the language used to express that content. There are two key

reasons why this simple fact is important for writing teachers. Firstly, the sheer volume of

reading at university is a major source of difficulty for ESL/EFL students (Skyrme, personal

communication). Secondly, the vocabulary in different sections of an academic text can differ

(Hirsh, unpublished paper). These differences in vocabulary result both from differences in the

wording of sub-sections of academic papers (abstracts versus methods versus conclusions) and

also in the way that content develops over the length of an article or a textbook chapter. To

develop students’ ability to handle the language as well as the context of academic reading,

their writing classes need to include whole-text reading. By working with texts of authentic

length and language, students can learn strategies for recognizing, dealing with, and then

using the new words that they find in required reading materials. Thus, the work with

academic reading passages should not focus exclusively on the content of the reading but also

include study of the academic language, along with work on strategies for vocabulary

learning.

The tradition in ESL/EFL has been to make vocabulary learning the responsibility of the

‘‘reading teacher’’ with the result that vocabulary is often approached at the recognition level

rather than with the ultimate goal of having the students learn to use the academic words in their

own writing. It is unrealistic to expect learners to produce newly met items, particularly difficult

ones, early on in their writing. Teacher educators should encourage teachers to provide multiple

opportunities to focus on these items in class, to draw attention to them while learners are reading

or listening, and to produce them in writing with time for feedback and rewriting (see Ferris, this

volume).

The place of language instruction in the writing EAP classroom: grammar of

academic writing

Presentation of information about grammar in a reference book (or a pedagogical grammar

textbook) generally proceeds on a category by category basis, verb tense by verb tense, noun

class by noun class, and on through the parts of speech and sub-divisions of sentences. This item-

by-item presentation profoundly influences how we view a language and, as a result, how we go

A. Coxhead, P. Byrd / Journal of Second Language Writing 16 (2007) 129–147 133

about presenting the language in curricula, materials, and lessons. Studies of the grammatical

features of different communication types (e.g., Biber, 1988; Biber et al., 1999; Byrd & Reid,

1998) reveal a fundamentally different picture of how grammar works in authentic

communication (rather than in reference grammars and ESL/EFL textbooks). For example,

academic prose is characterized by the following grammatical features:

� long complicated noun phrases with nouns more often followed by prepositional phrases than

by relative clauses,

� long nouns, big words, and a tendency to use words of Latin or Greek origin rather than the

simpler Anglo-Saxon word base of everyday conversation,

� lots of different words (especially compared to friendly conversation with its limited range of

often repeated words),

� simple present tense verbs in generalizations and statements of theory,

� a limited range of verbs with be, have, seem often repeated,

� frequent use of the passive voice (usually without a by-phrase),

� use of adverbial phrases to indicate location inside the text (e.g., in the next chapter, etc.).

In contrast to the verb-centered instruction often used in ESL/EFL grammar and/or grammar-

writing textbooks and curricula, academic prose is noun heavy. Of course, while it is true that

academic prose is noun-centric rather than verb-centric, such writing is not just made up simply

of nouns but of particular kinds of nouns combined with particular kinds of verbs and used with a

range of other grammatical features expected by members of that discourse community (Benz,

1996; Biber, 1988; Biber et al., 2004, 2002; Byrd, 2005; Henry & Roseberry, 2001; Swales,

1990). The major point here is that academic prose is made up of a variety of grammatical

features all working together in that environment, or even more accurately, all working together

to create that environment. As a result of this view of the clustering of grammar by functional

purpose, the teaching point in an EAP writing class will not be how present tense differs from past

tense but how academic prose requires a cluster of grammatical items all working together;

students need to learn to handle the whole set of characteristic vocabulary and grammar within

the context of creating appropriately worded academic prose. Attempts to understand how

language instruction influences language development are all too often undermined by a focus on

generic grammar (rather than deeply situated grammar/vocabulary) or by study of single

grammatical features such as verb tense (rather than the development of the cluster of

grammatical features characteristic of a particular type of communication) (Bunting & Byrd, in

press).

The place of language instruction in the writing EAP classroom: lexicogrammatical

sequences in academic prose

In addition to the grammar features that cluster together as the defining linguistic features of

academic prose and the individual words that are often used in academic writing, this type of

English has characteristic extended sets of words that come in relatively fixed sequences and that

are likely to be stored in memory as sets rather than created word-by-word for each use.

Examples include four-word sequences like those reported in Biber et al. (2004) in an

examination of phrases such as the extent to which, as a result of , at then end of , and it is possible

to. These sets of words are important for composition teachers and their students for at least three

reasons: (a) the word sets are often repeated and become a part of the structural material used by

A. Coxhead, P. Byrd / Journal of Second Language Writing 16 (2007) 129–147134

advanced writers, making the students’ task easier because they work with ready-made sets of

words rather than having to create each sentence word by word; (b) as a result of their frequent

use, such sets become defining markers of fluent writing and are important for the development of

writing that fits the expectations of readers in academia; (c) these sets of words often lie at the

boundary between grammar and vocabulary; they are the lexicogrammatical underpinnings of a

language so often revealed in corpus studies but much harder to see through analysis of individual

texts or from a linguistic point of view that does not study language-in-use. That is, teachers and

students may not be aware that these important sets of words exist, or that they exist as often

repeated sets rather than as individual words and need to be learned and used as sets. Wray (2002)

demonstrates the problems that adult second language learners have in recognizing the existence

of word sequences rather than individual words; she argues convincingly that one of the negative

results of literacy development is an unfortunate tendency to start seeing vocabulary in terms of

individuals words rather than the sets of words that are so characteristic of language-in-use. In

their EAP writing classes, students can be helped to learn these phrases as whole sets and to

experiment with such sets in their own writing.

A helpful summary of the types of recurrent lexical sequences and their grammatical features

is found in Biber et al. (1999) in Chapter 13, Lexical expressions in speech and writing (pp. 987–

1036). Because there are so many different kinds of recurrent lexical sets, no list will be

complete, and all lists will have overlapping content. However, the general patterns are similar

even when scholars use different terminology to label the patterns. The study of recurrent lexical

sequences is a relatively new one (Altenberg, 1998), with the result that categories are still being

discovered and the naming system still being negotiated.

Type #1. Multi-word combinations that are structural or semantic7 units: These are word sets like

the phrasal verbs and prepositional verbs that occur together as sets and need to be regarded as a

single unit, as a single word that happens to have two or more parts and that may have a more

complicated grammatical patterning than simpler compounds. Examples include look up, agree to.

Type #2. Multi-word combinations that are often termed idioms (on the difficulty of exact

definition and application of the term, see Grant, 2005; Grant & Bauer, 2004) and generally

involve meaning that is difficult, if not impossible, to derive from the typical meanings of the

individual words that make up the unit. Examples include red herring, shoot the breeze. Such

sequences are rare in conversation and even rarer in academic writing (Figs. 1 and 2).

Type #3. Collocation is the term used for the relationship between a word and other words that

are likely to appear in the environment of the word.8 To take an example from the most common

2000 words in English as used in the corpus of approximately 56,000,000 words called

WordBanks Online, the word mother has the collocates listed in the table. Some of these

collocates are grammatical (her, his), while others indicate the semantic environment in which

the word is situated (words for family relationships) as well as two-word combinations with

A. Coxhead, P. Byrd / Journal of Second Language Writing 16 (2007) 129–147 135

7 Linguists use the term semantics to refer to meaning in the traditional grammatical trilogy along with morphology

(word formation) and syntax (clause structures).8 Collocational relationships are revealed by a computer analysis of words in a corpus. The core word in the

relationship is termed the node while the words that often are found with the node are called its collocates. A statistical

program is used to decide if the relationship between two words that are frequently found near each other is accidental or

statistically significant. While some fixed expressions can show up as a result of a collocational analysis of words in a

corpus, these two-word combinations are often not fixed expressions that are easily recognized in a single text. However,

the relationship can be a powerful one with a word pulling other words to it on a regular, repeated basis that advanced

users of a language recognize when the relationship is pointed out but might not have been anticipated.

specialized use (Queen Mother, Mother Earth). The strong association of died and death with

mother results from the inclusion of biographic information in many of the subcorpora that make

up the larger corpora.9 The functions of mothers in U.S. and British society might be hinted at

with the close collocational relationship of mother to words of speaking such as said and told.

Finally, the inclusion of political and social commentary and news in the corpus is suggested by

the relationship between single and mother for the phrase single mother with its underlying

meaning of ‘‘a woman with a child or children but no husband.’’

Type #4. Word types based on complement and valency patterns: A major lexicogrammatical

pattern for verbs involves two widely recognized grammatical patterns for verb phrases: (a) many

A. Coxhead, P. Byrd / Journal of Second Language Writing 16 (2007) 129–147136

Fig. 1. Table collocates for Mother in WordBanks online.

9 The importance of information about the death of a person’s mother in a biographical profile might be worthy of

intercultural and/or pragmatic investigation.

verbs can take that-clauses or infinitives as their complements. That is, a feature of a

particular verb is whether or not it can take such a complement (and thus generally is used with

particular grammar) and, very importantly, any register10 differences over which type of

complement is used for particular types of communication; (b) Valency is the word used by

many linguists for the verb pattern teachers generally discuss in terms of transitive, intransitive,

and linking verbs. Again, particular words fit into particular grammatical patterns, demonstrating

once more the tie between vocabulary and grammar. Moreover, the connection between words

and grammar can go in either direction: if we want to talk about valency patterns, we end up

making lists of particular verbs that have the pattern, but if we want to talk about particular verbs,

we end up explaining their valency patterns as transitive, intransitive, or linking verbs.

Type #5. Lexical bundle is a term created and advanced by Douglas Biber, Susan Conrad, and

their colleagues (e.g., Biber & Conrad, 1999; Biber et al., 1999; Cortes, 2004). Lexical bundles

are sets of words that are repeated in exactly the same form and sequence at a frequency and over

a range of different registers specified by the researcher. Other scholars have investigated the

same pattern using other labels such as Altenberg’s recurrent lexical sequences (Altenberg,

1998). Biber et al. (1999) provides detailed information about lexical bundles found in their

corpus with the focus on recurrent sets of four words that appear at least 10 times per million

words, although some information is given about longer sequences. In their corpus, lexical

bundles often used in conversation include sets such as ‘‘I do not want to’’ and ‘‘Do you want,’’

while academic prose often uses sets like ‘‘in order to’’ and ‘‘there is no’’ The lexicogrammatical

force of these patterns derives from the combination of particular word sets (a matter of

vocabulary) that involve particular grammatical patterns (word order, subject–verb agreement,

and the grammar features required to complete the sequence). The lexical bundles characteristic

of academic prose fit within the larger nature of such writing. That is, many of the lexical bundles

reported by Biber et al. (1999) for academic prose involve noun phrase structure, passive verb

phrases, or use of a simple form of be followed by a noun or adjective phrase. Examples include

noun phrases followed by of (e.g., the number of); noun phrases with other types of post-modifier

fragments (e.g., the fact that); passive verb followed by a prepositional fragment requiring a noun

phrase for completion (e.g., are shown in); and copular be followed by a noun/adjective phrase

(e.g., is a matter of , is similar to).

Type #6. Semi-fixed sequences combining semantic requirements with grammar and

vocabulary: Another, but harder to study, feature of extended text is the use of more abstract

patterns that require the user to make choices hemmed in by certain semantic boundaries.

For example, Biber et al. (1999) illustrates the pattern that combines a modal with a required

set of words (and so, yet again, a combination of grammar and lexicon) in the pattern of

possibility modal + well be. The following example (with bold added) is from an

introduction to a logic textbook used in U.S. undergraduate courses (Hurley, 1994): ‘‘. . .then the personal comments made by the attacker may well be relevant to the conclusion

that is drawn.’’

A. Coxhead, P. Byrd / Journal of Second Language Writing 16 (2007) 129–147 137

10 No settled usage has yet been reached in corpus linguistics about the best way to refer to functional categories used in

different communication situations. Sometimes the term genre is used to refer to particular types of linguistic

communication such as business letters or academic journal articles. Sometimes genre is used for subdivisions of

longer genres, the methods section of a research paper, for example. In other publications, the term register is used to refer

to a more general group such as academic prose or newspaper writing or conversational English. However, scholars can

use genre and register as loose synonyms for each other. In addition, terms such as discourse and discourse types are used

for similar concepts.

Type #7. Frames involving highly frequent words: Highly frequent function11 words like the

and of are also used in patterns that researchers sometimes refer to as ‘‘frames’’ (Altenberg, 1998;

Biber et al., 1999; Renouf & Sinclair, 1991; Stubbs, 2004). A typical frame of this sort is ‘‘the —

of the —.’’ Such frames combine the vocabulary and grammar and can lead to relatively fixed

sequences that might be included in other sub-categories of recurrent word sequences. However,

the nouns used in the slots might not be used frequently enough for a particular combination to

rise to the level of recurrent word sequence, but the underlying pattern is itself highly frequent.

Type #8. Miscellaneous other subsets of recurrent lexical sequences: Researchers have found

other patterned sets of words that lie at the intersection of grammar and vocabulary. For example,

Biber et al. (1999) illustrates use of binominal phrases that put grammatically parallel words

(noun with noun, verb with verb, etc.) in phrases such as black and white.

Teacher analysis of selected samples of academic prose: resources and applications

In this section, we will look first at non-computer based ways to analyze samples of authentic

and ESL student texts and then move to computer-based applications.

Non-computer-based ways to analyze samples of language

In training programs and courses for teachers working in these settings, training can focus on

the following procedures for selecting and analyzing samples of language-in-use:

� Selecting texts for analysis and study, making sure they are academic in nature. Were they

written for an academic audience? Are they appropriate for the academic futures and interests

of your students?

� Analyzing of the selected academic texts to prepare for their use with students. Teachers can

read through the texts and highlight key lexicogrammatical features. What words are repeated?

What other words are used in the same environment as the target word? In addition to their reading

analysis, teachers can find valuable information about the use of words in the examples given in

corpus-based dictionaries. Words and phrases that they have decided to focus on with their

students can be studied in the context of the examples (even more than the definitions) in such

dictionaries as the Collins Cobuild English Dictionary for Advanced Learners or the MacMillan

English Dictionary for Advanced Learners of American English. Such a dictionary will provide

more than definitions by including authentic examples to illustrate the use of words in context.

� Planning for teaching activities with the words. After selection and analysis, teachers can think

about how they might teach or draw their students’ attention to the language selected as

important for students to learn to use in their writing. At this point, teachers can draw upon their

knowledge of language teaching to design vocabulary learning activities appropriate to their

students and their programs.

� Setting writing tasks that require learners to encounter and to use academic words (Coxhead,

2006). Systematic focus on lexicogrammatical features of academic texts can help the

development of the knowledge needed to write these items in a new context. Steps to achieve this

A. Coxhead, P. Byrd / Journal of Second Language Writing 16 (2007) 129–147138

11 Function words are those with grammatical function and little other meaning; their meaning is usually made clear in

context. The contrast is with words with fuller meaning, which are often termed lexical words. For example, the is a

function word while mother is a lexical word.

aim could be: identify the common words and phrases that are important for their writing; isolate

and analyze those common academic words and phrases and their collocates; recognize how the

words work in their academic context; practice using them in controlled ways; write with them in

less controlled ways; seek feedback; and work on that feedback to fill gaps in knowledge.

For example, below is a short extract from a university-level accounting textbook (Needles,

Powers, & Crosson, 2005) that could be the focus for developing knowledge of AWL words and

their common collocations and phrases in an accounting text. The words from the AWL in the

text are in bold so that they catch the attention of the reader. What AWL words occur frequently

in the text? Financial and annual stand out. What regular patterns do they occur in? What other

lexicogrammatical features do you notice in the text that would be worth precious teaching and

learning time in the classroom?

� General Mills Inc. hhttp://www.generalmills.comi The management of a corporation is

judged by the company’s financial performance. Financial performance is reported to

stockholders and others outside the business in the company’s annual report, which includes

the financial statements and other relevant information.

� Performance measures are usually based on the relationships of key data in the financial

statements. For large companies, this often means condensing a tremendous amount of

information to a few numbers that management considers important. For example, what key

measures does the management of General Mills Inc., a successful food products company that

recently acquired its long-time rival Pillsbury and offers such well-known brands as Cheerios,

Wheaties, Hamburger Helper, and Progresso Soups, choose to focus on as its goals?

� In its letter to shareholders, General Mills states its financial goals as follows: Our target is 7%

compound annual sales growth between now and 2010. With this faster topline growth, . . .our

Earnings Per Share (EPS) growth should accelerate, too. Our target is to deliver 11–15 percent

annual earnings per share growth over the balance of this decade. We believe achieving these

goals will represent superior performance when benchmarked against major consumer

products companies.

� General Mills’ management has thus set forth measurable performance goals by which it can

be evaluated. The graph on the opposite page shows that the company reached its growth in

sales target in only one of the past 3 years. However, it reached its growth in EPS in all 3 years.

Teachers might decide to look with their students at how target operates in this text. For

example, one can have personal targets (our targets), sales targets, and sometimes instead of

target, the word goals is used.

Computer-based tools for analyzing samples

Drawing attention to words in a text through highlighting can help teachers with their analysis

of samples of text they might want to use with their students. The AWL Highlighter (Haywood,

2007b), a web-based tool that highlights the AWL words in a text, is available at http://

www.nottingham.ac.uk/�alzsh3/acvocab/awlhighlighter.htm. Teachers and learners can cut and

paste texts of their own into this website or follow links on the page to on-line sources of texts

from sites such as the BBC, New Scientist and the Economist.

Traditional ESL/EFL teaching activities such as gap fills (known as ‘‘fill-in-the-blanks’’ in

U.S. usage) can be adapted to help students focus on important words and interact with the words

A. Coxhead, P. Byrd / Journal of Second Language Writing 16 (2007) 129–147 139

in part of that multiple-encounter and multiple-use pattern required for the learning of new

vocabulary. The AWL Highlighter website described above has a link to the AWL Gapmaker

(Haywood, 2007a)—available for free at http://www.nottingham.ac.uk/�alzsh3/acvocab/

awlgapmaker.htm. The Gapmaker creates fill-in-the blank exercises using electronic texts,

which is a useful way of having students focus on vocabulary in context (Folse, 2006). Here is a

fill-in-the-blanks exercise on our sample text using the AWL Gapmaker.

A. Coxhead, P. Byrd / Journal of Second Language Writing 16 (2007) 129–147140

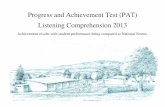

Fig. 2. Gap file from AWL Gapmaker (Haywood, 2007a) with gaps up to Sublist 10 of the Academic Word List.

The Compleat Lexical Tutor (Cobb, 2007), a web site that provides teachers and students

with a wide range of tools focused on vocabulary development, is available at http://

www.lextutor.ca/. Using the Vocabprofile tools, teachers and learners can analyze the

vocabulary in a text in terms of the GSL, AWL, and more specialized words. Compleat Lexical

Tutor also has a concordancing tool that operates on texts that instructors or students insert

themselves, or analysis on target words can be carried out using small bodies of texts provided

by the website.12 The concordancer will find all uses of a particular word in a text and then

create a concordance list to show the lines of the text where the word is used. Concordancing is

not a new tool to language teachers (Bernadini, 2004; Hunston, 2002; Hyland, 2003; Tribble &

Jones, 1990). A number of studies investigate academic writing and the use of

concordancing13: hedging in scientific articles (Hyland, 1998); the behaviour of common

academic words in texts and their functions, such as issue and factor to refer to the literature

(Thurstun & Candlin, 1998); using interactive concordancing for academic writing and the use

of quotations and citations (Garton, 1996); the use of concordancers to inform post-graduate

L2 writers (Starfield, 2004); and exploring differences in citations by L1 academic writers in

the sciences with samples from EAP student writing (Thompson & Tribble, 2001). Hoon and

Hirvela’s (2004) award-winning article on the attitude of ESL students working to the use of a

corpus in L2 writing classes reported that the participants felt overall that corpus use was

helpful to their second language writing, particularly if work with the corpus was ‘‘hands on’’

(p. 277). Bunting (2005) illustrates use of concordance lines in EAP vocabulary teaching

materials.

A concordance for a particular word can be examined by asking questions such as these:

1. If the word is a noun, what verbs and adjectives commonly occur with it?

2. If the word is a verb, what nouns and adverbs commonly occur with it?

3. Are there any lexicogrammatical patterns of the word that stand out in the data? For example,

if the word is a verb, what follows it: an infinitive, a that-clause, or some particular selection of

prepositions?

Below is a small sample concordance of the word widespread from a 3,500,000 word corpus

of written academic texts.

The basic question for teachers to learn to use through practice analysis is ‘‘What patterns can

you see in these concordance lines?’’ First of all, because of the alphabetical sorting, the first

word to the right in each example, except for Number 1 because of the percentage (80%), has

been sorted into initial position. Briefly, in this data set at the word level, widespread is followed

most often by adoption, then acceptance, and finally agreement. Even more important is that

most of these instances are of a noun phrase followed by another noun phrase, as in ‘‘widespread

something of something.’’

1. The same studies also reported widespread (80%) improvement in cash management and

credit control (p. 78)

A. Coxhead, P. Byrd / Journal of Second Language Writing 16 (2007) 129–147 141

12 One note of caution: a small body of texts limits the opportunity for words to appear, particularly lower-frequency

ones. The bigger the corpus, the more opportunities for a word or phrase to recur.13 Concordances are useful because they are based on real language and provide learners with exposure to words in a

range of contexts (Nation, 2001, p. 111). Concordance lists also focus attention directly onto the target words,

collocations, and lexicogrammatical features by showing the words that surround the target word.

2. Isolated rumours that he had suffered a nervous breakdown. Now the rumours were

widespread about Hitler’s fits and

3. restrictions on the employee’s right to refuse unsafe work would prompt its widespread

abuse, because workers would

4. and sound relationship. Throughout the Asia-Pacific region there is a widespread acceptance

of the view that third-party

5. left by the implied contract rationale is one of the factors that led to the widespread

acceptance of unjust enrichment.

6. Twenty years ago. Though a statement of Catholic doctrine, it has received widespread

acceptance. In his famous

7. Anatoki River Go Ahead Creek. Other minerals Zircon and apatite are widespread

accessories. The apatite contains

8. activity of Al, and the presence of boron, whereas the widespread accessory fluorapatite

points to

9. from just one resident, can unsettle the whole House and make for widespread acting out. It

is like one fire

10. The previous chapter were the exception rather than the rule in so far as their widespread

adoption was concerned

11. undermine the working conditions of those in conventional employment. The widespread

adoption of non-standard work

12. and economy will importantly depend on which has the greater strength. The widespread

adoption of exporting strategies has

13. 1990s, and is now delivering strong performance results. There has also been widespread

adoption of a range of other

14. outcomes are exceedingly difficult to assess, there appears to be at present widespread

advocacy for replacing

15. behind them. It is hardly possible that this could be so without widespread agreement on

which

16. a device has been chosen to reduce the amplitude of fluctuations. There is widespread

agreement that instability of

17. through war as honourable and singularly justified. To a degree it is widespread among many

not just in the

18. and listening to their objections. As we have seen, these practices are widespread among

BERLs respondents

Concordancing has also been used for comparisons of L1 and L2 writing (see Granger &

Tribble, 1998). It is hoped that soon the British Academic Written English Corpus (BAWE), a

corpus of proficient student writing for degree programmes at UK tertiary institutions (Nesi &

Thompson, 2007), will be available online also, to mirror in some ways the Michigan Corpus

of Academic Spoken English (MICASE), available at http://micase.umdl.umich.edu/m/micase/.

A business letter corpus is available at http://ysomeya.hp.infoseek.co.jp/, coupled with an online

concordancing programme.

Another useful computer-based tool for text analysis is Range (Nation & Heatley, 2007),

available as a free downloadable zip file at http://www.vuw.ac.nz/lals/staff/paul-nation/

nation.aspx. Range can help teachers analyze vocabulary in a large number of texts. Teachers

can use this tool with electronic forms of several texts to find out what vocabulary items

are shared across the texts, their frequency (word family and individually), and whether

A. Coxhead, P. Byrd / Journal of Second Language Writing 16 (2007) 129–147142

they occur in the first 2000 words, the AWL or not in any list. By using the frequency

and range information, teachers and learners can decide which items to focus on first in class.

The same program can be used by students to analyze the vocabulary they use in their own

writing.

Teachers can check the use of these words in a corpus-based dictionary, either paper-based or

online, paying special attention to the examples given for each definition to see how the words are

used in context. They could answer questions such as the following: What grammatical patterns

do these words occur in? Given the patterns that occur, how might composition students work

with such information about the grammar and vocabulary of academic English? Questions such

as these encourage focus on the words and phrases in use, thereby raising awareness of their form

and meaning.

Moving from the analysis of samples to teaching of academic vocabularyand grammar

The line between analyzing text for lexical, grammatical, and lexicogrammatical features and

knowing what to do with that analysis in the classroom can be more of a gully for many teachers,

especially inexperienced ones: What can be done with such information about academic

language to help students become better readers and writers as they handle the academic tasks

required in their degree study? Generally, students need to do at least the following:

� Expand their academic vocabulary, especially the AWL words used across many disciplinary

areas. Here students and teachers need to see vocabulary in the context of writing and not just

reading. Academic success requires learning how to use academic vocabulary in writing as

well as recognize it in reading.

� Be aware of the effect the L1 has on L2 writing (Jiang, 2004a,b).

� Become aware of the differences between academic vocabulary and the words that they use in

conversation with friends. Students need to realize that it matters for academic success to

present themselves in a style appropriate for the academic setting.

� Because academic study involves being in contact with tremendous numbers of words, students

need to learn how to sort through words in a textbook or other assigned reading passage or in an

instructor’s lecture to select the words important for their success in academic tasks.

� Understand that ‘‘learning a new academic word’’ means more than memorizing a synonym or

dictionary definition. ‘‘Learning a new word’’ includes knowing how to use the word in

lexicogrammatically expected ways.

� Understand that ‘‘learning a new academic word’’ means learning significant collocates or

recurrent lexical sequences in which the new word is embedded. This step is more difficult than

it might appear on first thought for highly literate adult second language learners who have

learned through their schooling to think of a language as made up of single words (Wray, 2002).

Here is an example sentence from an L2 student’s writing from an essay on the use of the

Internet for banking: However, the disadvantages of I-banking cannot be omitted, since people

have strict perceptions about what this thing is going on.

If we focus on the use of the word perception, for example, we could search for the

collocating word the student used (strict) in a corpus of academic writing and find that there

were no concordance entries for strict perception in a corpus of 3,500,000 running words

developed during the creation of the Academic Word List (Coxhead, 2000). Instead of strict,

A. Coxhead, P. Byrd / Journal of Second Language Writing 16 (2007) 129–147 143

the student might find data such as the perception of and the perception that, as in the sample

concordance lines below, from the corpus of academic written English mentioned above. The

student might also find these frequent collocations—our, public, personal, knowledge, and

visual and may revisit his or her use of the collocation strict with the noun perceptions. (A

search of google.com shows only eight uses of the combination of strict with perceptions, with

several examples seemingly written by non-native speakers of English. Google searches

provide a more easily available reality check that can be made by students and teachers without

ready access to an academic corpus.)

N Concordance

1 Framework: the impetus for the development of the NQF stems from the perception of successive

governments that educational reform should enhance New

N Concordance

2 the ways in which public and private school teachers and principals share a perception of autonomy,

where they are different, and how they experience const

N Concordance

3 nt. Although size of the institution plays a primary role in the perception of quality, the role it plays in the

autonomy felt by public and pri

N Concordance

7 s a general belief that private schools equate with academic excellence. The perception of academic

excellence in private schools may stem from a bel

N Concordance

70 ree to, and is inseparable from the three angles of a triangle. Sometimes the perception of connection

between two ideas is direct, we perceive it

N Concordance

75 circle has its characteristic properties. Given that ‘knowledge’ is the perception of connections between

ideas, and that where this perception is lack

� Be skillful at taking words and their associated grammar from their reading to use in their

writing. Academic writing proceeds to a great extent on the basis of skillful use of other

people’s words and of the corporate wording that has developed as the signature of academic

writing generally and in disciplinary subfields particularly (Macdonald, 1994).

To help students reach the skill and knowledge needed to become effective learners of new

words and their associated grammar, teachers must provide them with information about

academic language but also, of course, practice with task-appropriate activities along with the

scaffolding (Cotterall & Cohen, 2003) necessary for initiates to become more skillful at the

common but demanding task of academic writing. Practical teaching activities along with

information about academic vocabulary can be found in chapters 16 and 17 in Coxhead

(2006); information about assessment of student skills as academic writers is given in Weigle

(2002).

Conclusion

Writing teachers need support and tools to prepare to teach the vocabulary and grammar of

academic prose. The support includes clarification of the purposes of language instruction in a

writing class and, for many teachers, a giving of permission to make what they will perceive as a

fundamental philosophical change in their approach to teaching writing (see Doughty & Varela,

1998). The tools should include new ideas about English grammar, vocabulary, and the links

between the two as well as books, software, and websites that help with language analysis and

present language data in accessible forms for use by teachers.

A. Coxhead, P. Byrd / Journal of Second Language Writing 16 (2007) 129–147144

References

Altenberg, B. (1998). On the phraseology of spoken English: The evidence of recurrent word-combinations. In A. H.

Cowie (Ed.), Phraseology: Theory, analysis, and applications (pp. 101–122). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Benz, C. (1996). Entering an academic discourse community: A case study of the coping strategies of eleven English as a

second language students. Miami, FL: Florida International University.

Bernadini, S. (2004). Corpora in the classroom: An overview and some reflections on future developments. In J. Sinclair

(Ed.), How to use corpora in language teaching (pp. 15–38). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Biber, D. (1988). Variation across speech and writing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Biber, D., & Conrad, S. (1999). Lexical bundles in conversation and academic prose. In H. Hasselgard & S. Oksefjell

(Eds.), Out of corpora: Studies in honour of Stig Johansson (pp. 181–190). Amsterdam: Rodopi.

Biber, D., & Conrad, S. (2004). If you look at. . .: Lexical bundles in university teaching and textbooks. Applied

Linguistics, 25(3), 371–405.

Biber, D., Conrad, S., & Cortes, V. (2003). Lexical bundles in speech and writing: An initial taxonomy. In A. Wilson, P.

Rayson, & T. McEnery (Eds.), Corpus linguistics by the lune: A festschrift for Geoffrey Leech. Frankfurt/Main: Peter

Lang.

Biber, D., Conrad, S., & Cortes, V. (2004). Lexical bundles in university teaching and textbooks. Applied Linguistics,

25(3), 371–405.

Biber, D., Conrad, S., & Reppen, R. (1998). Corpus linguistics: Investigating language structure and use. Cambridge

University Press.

Biber, D., Conrad, S., Reppen, R., Byrd, P., & Helt, M. (2002). Speaking and writing in the university: A multidimensional

comparison. TESOL Quarterly, 36(1), 9–48.

Biber, D., Johansson, S., Leech, G., Conrad, S., & Finegan, E. (1999). Longman grammar of spoken and written English.

Harlow, England: Pearson Education Limited.

Bunting, J. (2005). College vocabulary level 4. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Bunting, J., & Byrd, P. (in press). One size fits all: A myth about grammar in the composition classroom. In J. Reid (Ed.),

Ten writing myths: Applying second language research to classroom teaching. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan

Press.

Byrd, P. (2005). Instructed grammar. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning

(pp. 545–561). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

Byrd, P., & Reid, J. (1998). Grammar in the composition classroom: Essays on teaching ESL for college-bound students.

Boston: Heinle & Heinle.

Cobb, T. (2007). The compleat lexical tutor. Available at http://www.lextutor.ca/.

Corson, D. J. (1995). Using English words. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Corson, D. J. (1997). The learning and using of English academic words. Language Learning, 47, 671–718.

Cortes, V. (2004). Lexical bundles in published and student disciplinary writing: Examples from history and biology.

English for Specific Purposes, 23, 397–423.

Cotterall, C., & Cohen, R. (2003). Scaffolding for second language writers: Producing an academic essay. English

Language Teaching Journal, 57(2), 158–166.

Coxhead, A. (2000). A new academic word list. TESOL Quarterly, 34(2), 213–238.

Coxhead, A. (2006). Essentials of teaching academic vocabulary. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Coxhead, A., Bunting, J., Byrd, P., & Moran, K. (in forthcoming). The Academic Word List: Collocations and recurrent

phrases. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Coxhead, A., & Nation, P. (2001). The specialised vocabulary of English for academic purposes. In J. Flowerdew (Ed.),

Research perspectives on English for academic purposes (pp. 252–267). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Doughty, C., & Varela, E. (1998). Communicative focus on form. In C. Doughty & J. Williams (Eds.), Focus on form in

classroom second language acquisition (pp. 114–138). Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

Flowerdew, J. (2003). Signalling nouns in discourse. English for Specific Purposes, 22, 329–346.

Flowerdew, L. (2003). A combined corpus and systemic-functional analysis of the problem-solution pattern in a student

and professional corpus of technical writing. TESOL Quarterly, 37(3), 489–511.

Folse, K. (2004). Vocabulary myths: Applying second language research to classroom teaching. Ann Arbor, MI:

University of Michigan Press.

Folse, K. (2006). The effect of type of written exercise on L2 vocabulary retention. TESOL Quarterly, 40,(2), 273–

293.

Garton, G. (1996). Interactive concordancing with a specialist corpus. On-call 10(1).

A. Coxhead, P. Byrd / Journal of Second Language Writing 16 (2007) 129–147 145

Granger, S., & Tribble, C. (1998). Learner corpus data in the foreign language classroom: form-focussed instruction and

data-driven learning. In S. Granger (Ed.), Learner English on computer (pp. 199–209). London: Longman.

Grant, L. (2005). Frequency of ‘core idioms’ in the British National Corpus. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics,

10(4), 429–451.

Grant, L., & Bauer, L. (2004). Criteria for re-defining idioms: Are we barking up the wrong tree? Applied Linguistics,

25(1), 38–61.

Haywood, S. (2007). The AWL Gapmaker. Available at http://www.nottingham.ac.uk/�alzsh3/acvocab/awlgapmaker.

htm.

Haywood, S. (2007). The AWL Highlighter. Available at http://www.nottingham.ac.uk/�alzsh3/acvocab/awlhighlighter.

htm.

Henry, A., & Roseberry, R. L. (2001). A narrow-angled corpus analysis of moves and strategies of the genre: ‘‘Letter of

application’’. English for Specific Purposes, 20(2), 153–167.

Hoey, M. (2002). Lexical priming: A new theory of words and language. London: Routledge.

Hoon, H., & Hirvela, A. (2004). ESL attitudes toward corpus use in L2 wrting. Journal of Second Language Writing,

13(4), 257–283.

Hunston, S. (2002). Corpora in applied linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hurley, P. (1994). A concise introduction to logic. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Hyland, K. (1998). Hedging in scientific research articles. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Hyland, K. (2003). Second language writing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jabbour, G. (2001). Lexis and grammar in second language reading and writing. In D. Belcher & A. Hirvela (Eds.),

Linking literacies: Perspectives on L2 reading-writing connections (pp. 291–308). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan

Press.

Jiang, N. (2004a). Semantic transfer and development in adult L2 vocabulary acquisition. In P. Bogaards & B. Laufer

(Eds.), Vocabulary in a second language. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Jiang, N. (2004b). Semantic transfer and development in adult L2 vocabulary acquisition. In P. Bogaards & B. Laufer

(Eds.), Vocabulary in a second language (pp. 101–126). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Laufer, B. (2005). Instructed second language vocabulary learning: The fault in the ‘default hypothesis’. In A. Housen &

M. Pierrard (Eds.), Investigations in instructed second language acquisition (pp. 311–329). Berlin: Mouton de

Gruyter.

Macdonald, S. P. (1994). Professional writing in the humanities and social sciences. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois

University Press.

Nation, P. (2001). Learning vocabulary in another language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nation, P. (2005). Teaching and learning vocabulary. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Handbook of research in second language

teaching and learning. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Nation, P., & Heatley, A. (2007). Range. from http://www.vuw.ac.nz/lals/staff/paul-nation/nation.aspx.

Needles, B., Jr., Powers, M., & Crosson, S. (2005). Principles of accounting. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Nesi, H. & Thomson, P. (2007). British academic written English corpus. Available at http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/

soc/celte/research/bawe/

Paltridge, B. (2004). Academic writing. Language Teaching, 37(2), 87–105.

Reid, J. (1993). Teaching ESL writing. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Regents/Prentice-Hall.

Reid, J. (2006). Essentials of teaching academic writing. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Renouf, A., & Sinclair, J. (1991). Collocational frameworks in English. In K. Aijmer & B. Altenberg (Eds.), English

corpus linguistics (pp. 128–143). London: Longman.

Schleppegrell, M. J. (2004). The language of schooling: A functional linguistics perspective. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence

Erlbaum.

Schleppegrell, M. J., Achugar, M., & Orteiza, T. (2004). The grammar of history: Enhancing content-based instruction

through a functional focus on language. TESOL Quarterly, 38(1), 67–93.

Schleppegrell, M. J., & Colombi, M. C. (Eds.). (2002). Developing advanced literacy in first and second languages.

Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Schmitt, N., & Zimmerman, C. (2002). Derivative word forms: What do learners know? TESOL Quarterly, 36(2), 145–

171.

Simpson, R., & Ellis, R. (2005). An academic formulas list Phraseology 2005. Belgium: Louvain-la-Neuve.

Sinclair, J. (1991). Corpus concordance collocation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Starfield, S. (2004). Why does this feel empowering? Thesis writing, concordancing, and the ‘corporatising’ university. In

B. Norton & K. Toohey (Eds.), Critical Pedagogies and language learning (pp. 138–157). Cambridge University

Press.

A. Coxhead, P. Byrd / Journal of Second Language Writing 16 (2007) 129–147146

Stubbs, M. (1993). British traditions in text analysis: From Firth to Sinclair. In M. Baker, G. Francis, & E. Tognini-Bonelli

(Eds.), Text and technology: In honour of John Sinclair (pp. 1–33). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Stubbs, M. (2004). On very frequent phrases in English: Distributions, functions, and structures.

Swales, J. (1990). Genre analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Thompson, P., & Tribble, C. (2001). Looking at citations: Using corpora in English for academic purposes. Language

Learning and Technology, 5(3), 91–105.

Thurstun, J., & Candlin, C. N. (1998). Exploring academic writing. Sydney: National Centre for English Language

Teaching and Research, Macquarie University.

Tribble, C., & Jones, G. (1990). Concordances in the classroom. Houston, TX: Athelstan.

Weigle, S. C. (2002). Assessing writing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wray, A. (2002). Formulaic language and the lexicon. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

A. Coxhead, P. Byrd / Journal of Second Language Writing 16 (2007) 129–147 147