Perceptions of Wildfire and Landscape Change in the Kenai Peninsula, Alaska

Transcript of Perceptions of Wildfire and Landscape Change in the Kenai Peninsula, Alaska

1 23

Environmental Management ISSN 0364-152X Environmental ManagementDOI 10.1007/s00267-013-0127-4

Perceptions of Wildfire and LandscapeChange in the Kenai Peninsula, Alaska

Jason S. Gordon, Joshua B. Gruver,Courtney G. Flint & A. E. Luloff

1 23

Your article is protected by copyright and all

rights are held exclusively by Springer Science

+Business Media New York. This e-offprint is

for personal use only and shall not be self-

archived in electronic repositories. If you wish

to self-archive your article, please use the

accepted manuscript version for posting on

your own website. You may further deposit

the accepted manuscript version in any

repository, provided it is only made publicly

available 12 months after official publication

or later and provided acknowledgement is

given to the original source of publication

and a link is inserted to the published article

on Springer's website. The link must be

accompanied by the following text: "The final

publication is available at link.springer.com”.

Perceptions of Wildfire and Landscape Change in the KenaiPeninsula, Alaska

Jason S. Gordon • Joshua B. Gruver •

Courtney G. Flint • A. E. Luloff

Received: 20 August 2012 / Accepted: 9 July 2013

� Springer Science+Business Media New York 2013

Abstract Despite a broad literature addressing the human

dimensions of wildfire, current approaches often compart-

mentalize results according to disciplinary boundaries.

Further, relatively few studies have focused on the public’s

evolving perceptions of wildfire as communities change

over time. This paper responds to these gaps by exploring

perceptions of landscape dynamics and wildfire between

2003 and 2007 using a typological framework of inter-

secting ecological, social, and cultural processes. Designed

as a restudy, and using key informant interviews, this

research allowed us to observe risk perception as they are

related to community challenges and opportunities in the

Kenai Peninsula, Alaska. Risk perceptions were examined

as an integral part of community and landscape change.

Wildfire was a concern among informants in 2003 and

remained a concern in 2007, although informants were less

likely to discuss it as a major threat compared to the ori-

ginal study. Informants in the western part of the peninsula

tended to express more concern about wildfire than their

eastern counterparts largely due to their experiences with

recent fires. Other important factors residents considered

included changing forest fuels, the expanding wildland

urban interface, and contrasting values of new residents.

Underscoring the localized nature of risk perceptions,

informants had difficulty describing the probability of a

wildfire event in a geographical context broader than the

community scale. This paper demonstrates how a holistic

approach can help wildfire and natural resource profes-

sionals, community members, and other stakeholders

understand the social and physical complexities influencing

collective actions or inactions to address the threat of

wildfire.

Keywords Risk perceptions �Wildfire �Bark beetle �Alaska � Restudy

Introduction

Over the past several years, trends in wildfire risk mitiga-

tion have shifted emphasis from agency-focused risk mit-

igation to empowerment and actions at the household and

community levels (USDA-USDI 2000; USDA-USDI

2009). Risk managers acknowledge that successful imple-

mentation of risk reduction strategies necessitates resident

participation. To do this requires an understanding of

public perceptions and collective agency within the com-

plex and widely varying contexts of impacted places. This

relatively new perspective is especially important in the

Wildland–urban Interface (WUI),1 areas that must contend

J. S. Gordon (&)

Department of Forestry, Mississippi State University, Box 9681,

Mississippi State, MS 39762, USA

e-mail: [email protected]

J. B. Gruver

Department of Natural Resources and Environmental

Management, Ball State University, West Quad, Room 110,

Muncie, IN 47306, USA

C. G. Flint

Department of Sociology, Social Work & Anthropology, Utah

State University, 0730 Old Main Hill, Logan, UT 84322, USA

A. E. Luloff

Department of Ag Economics, Sociology, and Education,

The Pennsylvania State University, 114 Armsby, University

Park, PA 16802, USA

1 The literature presents various WUI definitions. Here, we define

WUI as the area where human settlement is adjacent to or interspersed

with wildland vegetation (USDA-USDI 2001).

123

Environmental Management

DOI 10.1007/s00267-013-0127-4

Author's personal copy

with social and ecological problems related to residential

development in former timberland holdings. WUI growth

can be problematic because: (1) more people in areas of

high fuel levels increases the chances of ignition; (2)

emergency services must prioritize safety and protection of

homes, often at the expense of fire line containment or

letting the wildfire burn itself out; and (3) emergency ser-

vices could be limited due to the rural nature of the loca-

tion. Despite the evolution of perspectives toward risk

management, the 2009 Quadrennial Fire Report suggests

wildfire risk will increase due to continued WUI growth

(USDA-USDI 2009).

A significant body of research has examined wildfire

risk perceptions with an increase in community risk

management work emerging over the last decade (e.g.,

Brenkert-Smith 2010; Carroll and others 2005; Donovan

and others 2007; McCaffrey and others 2011; Steelman

and Kunkel 2004). However, additional study is needed

investigating the interactions among the biophysical, so-

ciodemographic, and sociocultural attributes of a place

that lead to variation in risk perceptions and management

(Blanchard and Ryan 2007; Brenkert-Smith and others

2012; Carroll and others 2005). Such an examination is

essential because residents and communities make

important decisions based on their perceptions and loca-

tions within a local landscape (Brenkert-Smith 2006;

Gordon and others 2010; Paveglio and others 2009).

Individual and collective interpretations of the changing

sociocultural, sociodemographic, and biophysical land-

scape both inform and interfere with public understand-

ings of forest-related risks. The entry of new worldviews

associated with in-migrants to WUI areas may funda-

mentally transform a community once concerned about

timber production jobs into one concerned about envi-

ronmental preservation, even at the expense of timber

production.

Alaska’s Kenai Peninsula presented a unique oppor-

tunity to examine wildfire risk perceptions at the inter-

section of environmental and social change that

frequently pitted resource extraction against amenity-dri-

ven growth. Complicating this shift, the peninsula was in

the final stages of a spruce bark beetle (SBB) outbreak in

2003, influencing forest fuel regimes and affecting per-

ceptions of wildfire in surrounding human communities.2

In response, research was conducted in 2003 to explore

wildfire risk perceptions in several Kenai communities

(Flint 2006). Then, in 2007, we returned to address any

possible changes. Few published studies have explored

wildfire risk perceptions in the same communities as

ecosystem disturbances and hazards cascade over time

(McCaffrey and others 2013).3

This paper compares key informant findings from both

studies to examine how wildfire risk perceptions of Kenai

residents changed within the context of shifting population,

landscape, and SBB. To do this, we employ an approach

that accounts for the biophysical, sociodemographic, and

sociocultural elements impacting wildfire risk perception

(Field and Burch 1991; Firey 1999; Landis 1997; Luloff

and others 2007; Wilkinson 1991). Although a large body

of work exists on coupled systems in general, this approach

has been applied less frequently to wildfire. The framework

employed here can help wildfire and natural resource

professionals, community members, and other stakeholders

understand collective action(s), or lack of action(s), to

address wildfire threats. Such an understanding will help

these groups work with communities to shift discussions

about wildfire from protecting communities at risk to ones

of self-reliance and increased resiliency (USDA-USDI

2009).

Background

The Wildland Urban Interface

WUI communities have experienced substantial growth

over the last several decades. As a result, there is height-

ened need to examine factors affecting their well-being

(Krannich and others 2003). One important trend in the

WUI is the shift toward forest fragmentation and smaller

properties through parcelization and the creation of low-

density developments (Egan and Luloff 2000). An

increasingly large number of homes are scattered among

forested tracts marked by high fuel build-up. Emergency

responders and natural resource managers find it chal-

lenging to protect life and property from wildfire due to the

distances they must travel, lack of water sources, and

underdeveloped road systems common to the WUI

(Radeloff and others 2005). Further, increases in popula-

tion have led to strained public services often forcing local

decision-makers to raise taxes in order to finance

improved/enhanced roads, emergency protection, educa-

tion, and other vital social services (Freudenberg 2001).2 In this paper, we do not suggest causality between SBB and

wildfire. Although SBB in Alaska is not as well understood as other

beetles (Berg 2006), a large body of research has focused on the

linkages between beetles and wildfire with widely varying conclu-

sions. While SBB does not increase wildfire risk, it can increase

hazard potential based on increased fuel load and volatility following

desiccation (Hicke et al. 2012; Jolly and others 2012).

3 We are aware of research by Shindler and Toman (2003) describing

a longitudinal analysis of public support for U.S. Forest Service fuel

reduction policies. In addition, McCaffrey and others (2011) recently

reported findings from the first half of a longitudinal study of

homeowner mitigation decisions.

Environmental Management

123

Author's personal copy

WUI social variability and complexity confound poli-

cies designed to increase local responsibility for wildfire

risk mitigation, collaboration between agencies and local

residents, and catalysis of homeowner actions (Jakes and

others 2011; Paveglio and others 2009; Sturtevant and

Jakes 2008). Inconsistencies in the literature reflect the

diversity of individual and community responses to wild-

fire. For example, two separate Canadian studies drew

contrasting conclusions about whether or not previous

experience with wildfire predicted resident mitigation

efforts (McFarlane and others 2011; McGee and others

2009). Sturtevant and Jakes (2008) found degrees of pre-

paredness among various case studies were associated with

unique place-based characteristics such as local history,

social organization, and environmental attitudes (also

McCaffrey and others 2011). In one of the few studies

focusing on states east of the Mississippi River, different

sets of social values led to wide ranging disparities in the

definition of the WUI which, in turn, were related to dif-

ferent Community Wildfire Protection Plans at either the

neighborhood, municipal, or county scales (Grayzeck-

Souter and others 2009).

Because WUI growth is an outcome of migration pat-

terns, it is important to consider inconsistencies in the lit-

erature concerning the relationship between residence

status (full-time vs. part-time and new vs. long-time) and

wildfire risk perceptions. Some studies found new residents

to be less likely than long-time resident to engage in

wildfire preparedness, while others found long-time resi-

dents just as unlikely to mitigate risk due to a malaise

toward frequent wildfire events (Burns and others 2008;

Carroll and Cohn 2007; Carroll and others 2005; Collins

2008; Daniel and others 2003; Gardner and others 1987;

Jakes and others 2007). In addition, wildfire preparedness

has been linked to homeowners’ preferences for natural

landscape amenities (Jakes and others 2007; McCaffrey

and others 2011). For example, Brenkert-Smith and others

(2006) and Nelson and others (2005) found homeowners

were unwilling to engage in vegetation removal because

the activity conflicted with the reasons for purchasing the

property in the first place. Homeowners often prioritized

privacy, wildlife habitat, vistas, and subjective definitions

of natural vegetative cover over defensible space. Addi-

tional research found residents failed to create defensible

space due to conflicting information or pre-conditioned

beliefs about the effectiveness of defensible space treat-

ments, the condition of adjacent forested tracts, and/or

wildfire behavior (Brenkert-Smith and others 2006; Bright

and Burtz 2006; Daniel 2006; McCaffrey 2008; Nelson and

others 2005).

Human dimensions of wildfire research have demon-

strated that awareness does not always translate into

behaviors. Numerous inconsistencies among such studies

underscore the subjectivity of risk depending on spatial

scale, risk tolerance and perceived vulnerability to harm,

type of negative outcome, trade-offs, and previous expe-

rience (McCaffrey 2008).

Steelman (2008, p. 64) suggested:

The perceived risk of wildfire destroying any one

individual’s home is very low, while the cumulative

risk to the entire community of wildfire can be much

higher. This creates a greater incentive for a com-

munity to mitigate the risk from wildfire than for any

individual property owner.

This ‘‘wildfire mitigation paradox’’ has led to a growing

body of research seeking to understand collective adapta-

tions to risk (Brenkert-Smith 2010; Carroll and others

2005; Everett and Fuller 2011; Jakes and others 2007;

McCaffrey and others 2011; McGee and others 2009;

Rodriguez-Mendez and others 2003; Sturtevant and Jakes

2008). Community risk reduction activities include pro-

grams such as FireWise, Fire Safe, FireFree, and Commu-

nity Wildfire Protection Plans as well as development of

rural fire departments and actions around individual homes.

Such actions constitute a critical part of community

development, which strengthen social networks and capac-

ities of residents to collectively respond to a variety of

community concerns (Fleeger 2008; Jakes and Nelson

2007; Sturtevant and McCaffrey 2006; Waugh and Streib

2006). During processes of community development,

engaged residents share attitudes about, and information

concerning wildfire (Amacher and others 2005; Brenkert-

Smith 2010; Carroll and others 2005).

The broad body of natural hazards research, including

studies focusing on wildfire, indicates residents not

engaged in community processes were less successful in

gaining assistance from neighbors and institutions follow-

ing a catastrophic event (Burns and others 2008; Cutter and

others 2008; Drabek and others 1975; Jakes and others

2007; Tierney and others 2001). If relationships among

community members and between residents and govern-

ment have not fully developed, as is often the case for new

residents, collective definitions of risk and strategies to

reduce risk may not materialize (Brenkert-Smith 2010;

Bright and Burtz 2006). Without meaningful public

engagement in decision-making processes, residents have

less confidence in an institution’s ability to fulfill its role,

and therefore might not be as willing to participate in

mitigation programs (Shindler and Toman 2003; Winter

and Fried 2000). Further, management interventions

designed solely to reduce biophysical hazards of wildfire,

while ignoring social vulnerabilities can result in unequal

distributions of risk between different residential groups

(Collins and Bolin 2009; Cutter and others 2008). In short,

sustainable risk mitigation, at the community level,

Environmental Management

123

Author's personal copy

requires opportunities for facilitating formal and informal

social relationships among residents to expedite informa-

tion flow and engage homeowners in mitigation activities

(Sturtevant and McCaffrey 2006).

Wildfire Risk in the Kenai Peninsula: Summary

of Initial Research

Beginning in the late 1980s, an SBB infestation quickly

spread across more than 400,000 acres of spruce forests in

the Kenai Peninsula. Early research found widespread con-

cern about negative esthetic affects (Daniel and others 1991;

Kruse and Pelz 1991). By 2003, SBB populations had begun

to decline; however, their impacts were evident in vast acres

of largely dead stands of trees (Flint 2006). In response, Flint

and colleagues (Flint 2006, 2007; Flint and Luloff 2007;

Flint and Haynes 2006) used data from key informant

interviews (n = 115) and a mail survey (n = 1,088/46 %) to

compare attitudes about the impacts of SBB on wildfire

hazard across six area communities.

One of the most important findings of the 2003 study

was that different stages in the SBB outbreak were asso-

ciated with residents’ perceptions of the degree of its

impact. Some communities identified impacts related to

high probability of wildfire hazard, danger from falling

trees, declining watershed quality, landscape change, and

reduced habitat quality. Others experienced economic

benefits through timber salvage and, consequently, short

term revenue and increased employment. Notably, public

policies addressing beetle infestation, timber management,

and recreation strained the relationship between local

communities and resource managers.

Initial research from 2003 highlighted strong feelings

about forest utilization, particularly salvaging versus leaving

beetle killed trees on site. Such attitudes were connected with

dissatisfaction over the lack of coordination among agencies,

poor harvesting practices, and perceived lack of attention to

forest regeneration. Over 60 % of survey respondents were

unsatisfied with the way borough, state, and federal land

managers handled forest risks resulting from the SBB out-

break. Further, over 85 % of respondents claimed residents

did not have a voice in management decisions. The only

significant finding regarding local actions to reduce risk was

evidence of pre-existing capacities of residents to work

together on issues and threats regardless of the level of

conflict (Flint 2006, 2007).

A Biophysical, Sociodemographic, and Sociocultural

Approach

Flint and colleagues’ initial research in the Kenai Peninsula

informed Luloff and others’s (2007) development of a

holistic approach for understanding the complex relationship

among coupled social and biological systems and was based

on the perspective:

…that a comprehensive methodological strategy that

embraces spatial, temporal, and theoretical scales is

needed in natural resource-related research work.

Studies in these areas must be replicated, both in

research design and across physiographic regions

(Luloff and others 2007, p. 208).

This perspective reflected recent and classic works, which

suggested anchoring human dimensions of natural

resources work to at least three dimensions: biophysical,

sociodemographic, and sociocultural (Blaikie and others

1994; Cutter and others 2008; Field and Burch 1991; Firey

1999; Landis 1997; Wilkinson 1991).

As explained by Luloff and others (2007), the first key

dimension of this holistic approach was the biophysical

environment. Biophysical factors include land cover,

topography, climate, fuel load, fire regimes, wildlife, forest

insect disturbance, and other ecological characteristics of the

site. The second dimension consisted of sociodemographic

characteristics such as population distribution, land use,

political jurisdictions, and economic structure. Social and

cultural characteristics, such as collective experiences, atti-

tudes, beliefs, and values framed the third dimension and

provide a context for the relationship between humans and

fire that is unavailable in demographic and economic pro-

files. It is important to note that in any given wildfire risk

context the three dimensions can exhibit considerable

overlap. As these dimensions intersect, interactions take

place that impact wildfire risk perceptions and community

response. The framework accounts for both objectively

defined risk factors (i.e., inherently biophysical factors) as

well as subjectively defined (i.e., socially constructed) risk

factors (Blaikie and others 1994).

A variety of social science concepts have been used to

explain the ability of a community to adapt to wildfire risk.

For example, Flint and Luloff (2007) and Gordon and others

(2010) used field interactional theory to guide the study of

the role and influence of social relationships on community

preparedness for wildfire. Paveglio and others (2009) added

the concept of adaptive capacity to interactional field theory

in their study on how WUI residents responded to commu-

nity problems. Others incorporated concepts from the sense

of place literature, which informed intimate knowledge of

and emotions about local environments (Brenkert-Smith

2006; Jakes and others 2007). In addition, Bihari and Ryan

(2012) recently examined how place attachment and past

experience with wildfire influenced social capital and the

subsequent adoption of defensible space.

Another noteworthy framework concerned place vulnera-

bility, which has been defined as the magnitude and type of

exposure to risk generated by the physical and social attributes

Environmental Management

123

Author's personal copy

of a geographic location (Cutter and others 2008). The spatial

relationships between individuals and hazards influence per-

ceptions about probability of harm. Similarly, Blaikie and

others (1994) looked at the significant magnification of bio-

physical and social vulnerabilities by inequality and greed.

While, each of these perspectives is linked in its explicit

acknowledgment of physical and social influences on risk

perceptions, as a whole, they have tended to emphasize vul-

nerability over collective agency. It is not surprising, then, that

these studies have assumed communities to have minimal

capacities to work toward hazard preparedness and resiliency.

Luloff and others’s (2007) approach accounted for

community agency toward wildfire preparedness within

place-based social and physical contexts. In response to

Luloff and others’s (2007) call for multidimensional and

longitudinal studies to capture community perceptions of

wildfire risk, we returned to the Kenai Peninsula commu-

nities first visited in 2003. We explored two research

questions: (1) What factors related to each of the three

dimensions of our integrated approach influenced risk

perceptions? (2) Did such perceptions, and the importance

of different dimensions, change over time?

Setting

Kenai Peninsula study communities included Anchor Point,

Homer, Ninilchik, Seldovia, Moose Pass, and Cooper Landing

(Fig. 1). Sites included Alaska Native communities and

communities within and outside of federal management areas.

According to the Decennial Census, the population across the

study area had been increasing with the exception of Seldovia,

which had declined by about 2 % (Table 1). Between 1990

and 2010, the population of Moose Pass increased the most,

moving from 81 to 219 (170 %) coupled to a corresponding

169 % increase in housing units. The populations in Anchor

Point and Ninilchik also increased substantially (123 and

94 %, respectively). Homer, the largest populated place in the

study area, and Cooper Landing grew at slower rates (37 and

19 %, respectively). All sites had experienced SBB activity

since the mid-1990s and several fires burned across the pen-

insula in the 2000s (Burnside 2011). Among them, the Tracy

Avenue Fire burned 5,400 acres in 2005 and the Caribou Hills

Fire burned 55,438 acres and destroyed 197 structures in 2007

(Kenai Peninsula Borough Office of Emergency Management

2011).

Methods

Key informant interviews were conducted in each of

the study communities during 2003 and 2007 (Table 2).

Informants were selected for their representation of various

perspectives and knowledge of the study communities

(Krannich and Humphrey 1986). In 2003, 120 key infor-

mants were interviewed. In 2007, effort was made to revisit

informants contacted in 2003 to compare their responses

over time; additional informants, not interviewed in 2003,

were identified using snowball sampling with purposive

selection to encourage a diversity of perspectives (Hecka-

thorn 2002). Researchers conducted 120 and 81 interviews

in 2003 and 2007, respectively. Of the 81 informants in

2007, 45 were interviewed previously. The remaining 36

consisted of long-time and new residents. The former

reported their perspectives from 2003 versus 2007, while

the latter reported on how their perspectives had

evolved since moving to the area. The community level

perspectives provided by new informants were no less

valuable than those repeated from the 2003 interviews and

differences in perspectives were noted during analysis. To

ensure comparability across the study area, informants

representing each of the following perspectives were

interviewed in each community: (1) business leader; (2)

religious leader; (3) someone who had lived in the com-

munity for several decades; (4) new or seasonal resident;

(5) news media; (6) volunteer; (7) government employee;

(8) forester or logger; (9) Alaska Native; (10) environ-

mental activist; and (11) someone involved with education.

As is the case with key informants, individuals often rep-

resented more than one category.

For both studies, semi-structured interviews asked open-

ended questions focusing on: (1) perceptions of landscapeFig. 1 Kenai Peninsula, Alaska

Environmental Management

123

Author's personal copy

change and public response to SBB and wildfire; (2) col-

lective agreement about the level of forest risks; (3) notions

about the causes of local wildfire risk; (4) individual and

collective actions to address wildfire and other forest risks;

(5) outside attempts to address wildfire and other forest

risks; (6) opinions about private and public forest man-

agement in the area; (7) perceptions of the economic sit-

uation; and (8) descriptions of local community

participation. The 2007 questions included probes intended

to address changes since the 2003 study. The use of open-

ended questions encouraged informants to volunteer

information, rather than simply respond to queries. Their

rich and spontaneous replies provided a view of the reality

of a place, including broad patterns of relationships among

actions and actors with the local environment (Elmendorf

and Luloff 2001).

With informant approval, interviews were tape-recor-

ded to complement the interviewer’s notes. Discussions

were transcribed and analyzed for emergent themes using

a two-step coding process involving reading through the

transcripts and then coding into thematic categories

(Creswell 1998). Themes were compared within and

across cases. Each author reviewed the data and added

additional interpretation to improve reliability. The

identified themes were then organized according to the

biophysical, sociodemographic, and sociocultural dimen-

sions of our approach.

Findings

The Biophysical Dimension

The biophysical dimension accounted for climate, land-

scape, and spatial factors influencing wildfire risk percep-

tions. As with the original study, 2007 informants

continued to link SBB with wildfire. However, they

described a moderated influence of SBB on wildfire risk

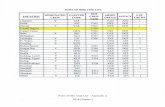

Table 1 Population and housing characteristics (Census 1990, 2000

SF1)

Place Population

(2010)

Population

change

(1990–2010)

(%)

Housing

units

(2010)

Housing

units

(1990–2010)

(%)

Moose

Pass

219 170 137 169

Anchor

Point

1,930 123 1,239 206

Ninilchik 883 94 967 193

Homer 5,003 37 2,692 61

Cooper

Landing

289 19 395 41

Seldovia 420 -2.3a 414 5.9a

Borough 55,400 36 30,578 58

a Reflects aggregated population and housing data (Seldovia City and

Seldovia Village CSD) between 2000 and 2010. Data for those living

beyond Seldovia city limits is not necessarily accounted for in the

1990 data, so was not included

Table 2 Key Informant

Categories (each category

represents a perspective from

the community)

a 2003b 2007c Includes Alaska Native

Key informant category Anchor

Point

Cooper

Landing

Homer Moose

Pass

Ninilchik Seldovia

School a ab ab ab b

Businessc ab ab ab ab ab ab

Library a ab ab ab ab ab

Governmentc a a ab ab a ab

Religiousc a b ab a a ab

Emergency services a a ab a a ab

Community (volunteer)

servicec

ab ab a ab a ab

Logging/forestryc ab ab ab ab ab ab

Environmentalist perspectivec a a ab ab ab ab

Newspaper or media a a ab a ab

Homesteader or longtime

residentc

a ab ab ab ab a

Newcomer/seasonal ab ab ab a a a

Total 2003 (120 interviews) 23 13 34 12 21 17

Total 2007 (81 interviews) 6 12 22 14 10 17

Repeated 2003 5 3 15 7 7 8

Total 2003 and 2007 29 25 56 26 31 34

Environmental Management

123

Author's personal copy

compared to data from 2003.4 A second major finding

addressed the spatial and temporal variation of wildfire risk

perceptions across the study area. Divisions between

dimensions can be blurred, underscoring the complexity of

risk perceptions.

Interviews from both 2003 and 2007 demonstrated res-

idents’ perceptions that SBB and fire hazard were linked. In

2003, many residents commented on increased fuel loads

as a result of SBB damage and the heightened probability

of a major fire event. Residents often described the event as

a natural cycle: ‘‘Now it’s just hundreds of acres of dead

trees. Until that whole cycle goes, we’re just in for the long

haul.’’ Some informants questioned the relevance of the

SBB-wildfire linkage because they were aware of the sci-

entific debate over the volatility of dead trees versus res-

inous green trees. One informant indicated, ‘‘You can pick

which side [of the debate over dead trees versus green trees

you like] and find a scientist or literature to support it.’’

Ultimately, such inconsistencies inflamed community dis-

agreement over whether timber salvage was necessary to

decrease the probability of wildfire. By 2007, the saliency

of SBB as a driver of landscape change had diminished:

‘‘Well, I mean… it’s just kind of come and gone in a way. I

wouldn’t see a sense of anxiety.’’’

A second important theme involved concerns about

wildfire as a function of proximity to past fire events and

fuel types. For example, interviews from 2003 informants

in the oceanside communities of Ninilchik and Anchor

Point suggested concern about wildfire was connected to

grass fuels instead of SBB damaged trees which had been

cleared to mitigate risk: ‘‘The big concern now is not so

much the dead spruce trees because there aren’t that many

around, it’s the grass that’s come up where it’s been log-

ged.’’ This long-time resident also noted concern over grass

fire peaked during dry weather. By contrast, informants in

Cooper Landing and Moose Pass expressed concern due to

their adjacency to the Chugach National Forest. Fuel

reduction efforts by the U.S. Forest Service failed to alle-

viate their concerns.

Wildfire remained a concern in 2007, although infor-

mants were less likely to discuss it as a major threat

compared to the original study. Informants in Homer,

Anchor Point, and Ninilchik tended to express more con-

cern about wildfire than their eastern counterparts largely

due to their experiences with recent fires: ‘‘I think most of

us still realize that [wildfire] can happen at any time…-because they’ve heard it and they’ve gone through several

large fires.’’ Because the recent fires ignited in grass fuels,

grass fire was a greater concern than forest fire and risk was

linked to human encroachment into wildland places.

Underscoring the localized nature of risk perceptions,

residents were asked to describe risk across the peninsula

in general; however, informants had difficulty describing

the probability of a wildfire event in a geographical context

broader than their community.

The Sociodemographic Dimension

The sociodemographic dimension accounted for factors

such as population distribution, land use, political juris-

dictions, and economic influences. Residential construction

into wildland areas and the shift away from an extraction-

based economy were important themes.

The number and intensity of comments in 2003 sug-

gested concerns regarding population change were greatest

in Homer and Cooper Landing. The backgrounds and

experiences of many newcomers differed dramatically

from those of long-time residents:

[It’s] a desirable place to live so there’s an awful lot

of building going on. People with some portability in

their professions or people who can do their con-

sulting through email can choose to live here. Prop-

erty values reflect that.

This informant noted new residents frequently had higher

incomes than long-time residents; many of the latter had

settled in the area to ‘‘get back to the land.’’ As well,

informants suggested many new residents spent little time

in the community and were unlikely to participate in

wildfire preparedness programs.

By 2007, descriptions of residential development were

positioned at the forefront of informants’ discussions. In

places like Cooper Landing and Moose Pass, WUI growth

seemed particularly intense because the communities were

surrounded by mountains and public land. Issues related to

development precipitated conflicts between residents.

Some informants suggested decision-makers put too much

value on development into fire-prone areas:

They seem to [keep moving] out a little farther [into

the forest] and it’s getting to the point where most of

the problems – the worst problems [in terms of

wildfire] are within the private holdings. It’s jack-

strawed.

This informant pointed to three factors driving WUI

growth: new residents’ attraction to natural amenities,

pressure from developers on decision-makes, and the lure

of a growing tax base.

In addition to an expanding WUI, informants high-

lighted issues related to changes in local economies.

Despite growing tourism and residential construction,

a number of residents in 2003 remained financially

4 See Flint and colleagues cited in this paper for additional analysis

of 2003 findings.

Environmental Management

123

Author's personal copy

dependent on timber, fishing, and other forms of natural

resource extraction and suggested SBB was a risk associ-

ated with the business of growing and harvesting timber.

These resource dependent residents noted previous periods

when hillsides were left bare of trees due to logging and

forest fires: ‘‘We’re used to seeing and visualizing changes

in the forest.’’ Like any other form of timber casualty loss,

they felt the impacts of SBB should be mitigated using

salvage operations: ‘‘Because we didn’t [do an aggressive

salvage operation], areas that were let go really got hit hard

[by SBB]. In the end, a lot of money was lost.’’ Informants,

who thought along these lines, considered wildfire a normal

part of the local landscape and, as with other landscape

events, felt that proper responses should involve human

intervention. Such comments conflicted with opinions by

residents—particularly in Homer—who were not depen-

dent on resource extraction: ‘‘The people that didn’t have

that much land were mad at the people that had land and

cut the trees.’’

By 2007, much of the salvageable material had been

harvested and some informants described the resulting

economic change as the ‘‘boom and bust’’ of logging

across the peninsula. Consequently, residents were no

longer as closely tied to forest products as they had been.

Partly due to the decrease in harvesting, 2007 participants

expressed less concern than 2003 informants over what to

do with dead and dying trees. However, questions con-

tinued to surround decisions made in the past. Many

residents who had formerly opposed logging changed

their minds after a series of wildfire events threatened

communities and homes: ‘‘There were a number of

community people in the early days that were against the

logging, but then when the fire happened, maybe not so

much.’’ Several other informants commented that their

opinions about salvage operations for fuel reduction

purposes had changed over time, although they continued

to oppose commercial harvesting.

Regardless of demographic background, informants

discussed the impact of previous salvage logging on forest

regeneration. Some observed that areas not salvage-logged

appeared healthier than those that had been logged. ‘‘One

thing that surprised a lot of people was how fast the

regeneration is coming along, especially in those areas that

haven’t been logged.’’ Even informants working in the

timber industry admitted areas that had been logged were

not regenerating adequately. By contrast, informants on the

eastern side of the peninsula had experienced grass fires

since the SBB outbreak: ‘‘At some point they always go

beyond what is needed [by thinning] and then the grasses

grow that much faster.’’ This informant was concerned

thinning would lead to grass regeneration and worsen the

wildfire hazard.

The Sociocultural Dimension

The sociocultural dimension illuminated how attitudes,

beliefs, values, and collective experiences influenced resi-

dents’ responses to wildfire. In this section, central themes

focused on attachments to the forest and actions to respond

to wildfire risk.

When asked how important forests were to the commu-

nity compared to other issues in 2003, one long-time resident

explained, ‘‘They’re cutting trees—something that this

community is very concerned about and very protective of.’’

Another said, ‘‘It was kind of like going through mourning.’’

While all residents were impacted, newcomers were espe-

cially vocal about loss of view-sheds. One newcomer stated:

‘‘You have a very strong mindset of people who move here

because they want forests and trees and moose and eagles.’’

By comparison, long-time residents described initial shock

followed by resigned acceptance: ‘‘For everybody that’s

lived here for so long, when it hit us it was kind of a shock,

until we realized we just had to live with it.’’

Informants described many of their neighbors as having

adjusted to the changed landscape by 2007. Some partici-

pants believed conditions had improved. This quote reflects

a frequent comment: ‘‘You can talk to some people that

say, ‘You know I never realized I had this kind of a view

off of my property. I can now see the mountains.’’’ The

quote demonstrates some residents were searching for an

optimistic perspective regarding the loss of trees in an

effort ‘‘to move on.’’ Residents who had moved to the area

after the SBB outbreak were unaware of the previous

landscape and valued the vistas created by forest clearing.

In other cases, informants noted harvesting operations had

prepared beetle-impacted sites for home-building.

One theme from the 2007 interviews contrasted with the

general ‘‘moving on’’ attitudes expressed across the pen-

insula. Informants from Cooper Landing and Moose Pass

described their neighbors’ persistent distrust of the U.S.

Forest Service and questioned the agency’s ability to mit-

igate wildfire risk. Prior to 2003, the agency had ignored

residents’ concerns about a prescribed burn that subse-

quently escaped and threatened homes. According to

informants, the agency’s mishandling of information and

failure to address conflicting claims about different man-

agement strategies impacted public trust more than the

prescribed burn accident: ‘‘It’s not fire, it’s the govern-

ment’s response to fire that has opened our eyes.’’ Despite

later efforts to improve public involvement in forest man-

agement decisions, residents had difficulty believing the

agency was effectively protecting them from wildfire.

With the exceptions of Cooper Landing and Moose Pass,

acceptance of the perceived inevitability of landscape

change may have been associated with awareness (but not

Environmental Management

123

Author's personal copy

necessarily concern) about wildfire. Over time, an

increased interest in defensible space and other FireWise

activities in response to the changing landscape emerged:

‘‘Most of the extreme fear has leveled out for the better.’’

Reflecting on controversy and debate over landscape

change in 2003, an informant explained that the differences

in opinion reflected larger issues:

In a way it [SBB] made us all have to deal with issues

like loss and change. The loss of the trees…the

emerging views…bring in a different change. Change

from the way things are, the way people live out here.

And Homer is not always good with change. That’s a

source of struggle…change from a simpler life to a

bigger life.

This informant suggested physical changes in the land-

scape were linked with social and cultural changes in the

community. The bark beetle outbreak and wildfire risks

forced residents to address challenges to local identities

and community well-being. As a result, the focus on

esthetics was incorporated into the scientific debate over

the impacts of logging and the cyclical nature of

disturbance.

Attitudes about esthetics and wildfire appeared to impact

resident participation in community activities generally,

and wildfire mitigation activities specifically. In 2003,

informants across the peninsula described their neighbors

as actively participating in their communities. The remarks

from an Anchor Point informant, provided below, reflect

the majority of comments about communication on topics

of general interest in his community:

There’s no lack of people willing to express their

opinion. We’re used to being on five different

committees and basically being with the same peo-

ple. Things are not always handled as effectively

as they could. But that’s not to say they’re not

communicating.

Based on preexisting capacities, some communities were

able to overcome conflict and mobilize collective resources

to offer community-wide wildfire mitigation strategies

such as coordinating defensible space activities, tree

planting campaigns, and supporting timber harvests on

public lands.

In 2007, informants continued to describe high levels of

participation; however, many comments addressed the lack

of participation by new and seasonal residents. A Seldovia

informant suggested these residents were more interested

in recreation activities than community affairs:

When [new residents] are here, they’re doing the

things they came here to do. They are not involved in

the community and they’re not too knowledgeable

about issues like [wildfire]. That’s a reflection of this

change that I see at least in this structure of the

community.

Another informant commented: ‘‘[Seasonal residents]

think the year-round people will take care of it.’’

Although this informant expressed frustration, she sug-

gested long-time residents should be responsible for

making efforts to involve new residents in local activities

and decision-making. She believed such efforts, over time,

would result in common perspectives of new and long-

time residents.

Summary

Table 3 summarizes our major findings organized accord-

ing to the three dimensions of our research approach. The

table presents primary and secondary influences of each

finding. Primary influences are traced to the same dimen-

sion as the findings, while secondary influences emerge

from other dimensions.

Biophysical Dimension

Findings indicated little change in residents’ perceptions of

the relationship between SBB and wildfire occurred

between 2003 and 2007. Factors inspiring informants’

comments included visual clues about the landscape (e.g.,

vegetation mortality) as well as an understanding of eco-

logical processes. Several interactional factors influenced

this finding, including experience with fire (associated with

time in the community and communication with neigh-

bors), environmental values regarding wood utilization

(i.e., salvage) and forest management (e.g., thinning), and

conflict over differing social values.

By 2007, the saliency of SBB as a major threat and

driver of landscape change had declined. Contributing

factors included an understanding of local landscape pro-

cesses, while additional influences included fire experience

and values associated with wood utilization and residential

growth. The third theme underscored increased emphasis

of spatial properties on risk perceptions in Homer, Anchor

Point, and Ninilchik. Fuel type, condition (wet or dry), and

proximity, as well as fire history (recent grass fires) were

directly associated with the theme. Other influences

included experiences of different resident groups, increas-

ing proximity to fuels as a result of WUI growth, and lack

of trust in the Forest Service in Cooper Landing and Moose

Pass based on previous experiences and communication

among residents.

Environmental Management

123

Author's personal copy

Sociodemographic Dimension

WUI growth and residential development emerged as a

stronger influence in 2007 than 2003. Fueled by an increase

in population, political and economic pressures encouraged

land parcelization and development in fuel zones. New

residents valued the landscape’s natural amenities for

esthetics and recreation; their values clashed with the

utilitarian views of long-time residents. Further, new resi-

dents had not lived in the community long enough to learn

about biophysical processes from long-time residents.

Issues and concerns related to the economic shift from an

extraction-based economy were as prevalent in 2007 as in the

initial study. Environmental attitudes played an important

role (e.g., fuel reduction was acceptable, but commercial

harvesting was not), as did the SBB population decline,

which led to the ‘‘bust’’ in salvage harvesting. More infor-

mants were satisfied with the status of regeneration in 2007

than 2003. Attitudes were influenced by financial depen-

dence on forest products or outdoor tourism, decline in the

SBB population, wanting to put SBB in the past, landscape

esthetics, and attitudes toward forest management (i.e., sal-

vage, thinning, and prescribed burn policies).

Sociocultural Dimension

In 2007, informants described an adjustment to the nega-

tive effects of SBB on emotional attachments to the land-

scape (known as place disruption), which, in turn, were

connected to wildfire risk perceptions (Brown and Perkins

1992). Adjustment did not indicate apathy about wildfire,

but an adaptation to a traumatic event (the loss of trees)

with wildfire concerns persisting in the collective con-

sciousness. Attitudes about resource utilization, amenities,

and agency trust (in Cooper Landing and Moose Pass) were

contributing factors to changes in place attachment. Inter-

acting factors included physical aspects of landscape

change, and SBB migration. Proximity to fire hazard was

important to residents living near heavy fuel zones and

national forests. Experience with SBB, as determined by

residence status, affected the extent of disruption and

adjustment.

Although a high level of collective action was consistent

between the two studies, 2007 informants were more likely

than earlier informants to describe a lack of participation

by new residents. Values linked to resource extraction or

recreation, and empathy of long-time residents toward new

Table 3 Summary of findings by dimension

Major findings: ‘‘Wildfire

risk perceptions are

influenced by…’’

Dimension Change

2003–2007

(yes/no)

Primary contributing

factors related to finding

Secondary or interactional factors

SBB and wildfire hazards BP Yes Visual clues, local

knowledge

(1) knowledge and fire experience (SD residence status,

SC social interactions) (2) biases regarding salvage (SC

values) (3) forest management (SC values and social

interactions)

SBB driving landscape

change

BP Yes Visual clues, local

knowledge

(1) knowledge and fire experience (SD residence status,

SC social interactions) (2) resource utilization and

residential development (SC values)

Spatial factors BP Yes Fuel characteristics/

proximity, previous fires

(1) fire experience (SD residence status) (2) WUI growth

(SD population change) (3) institutional trust (SC social

interactions)

Concern about

development

SD Yes In-migration, political/

economic pressures,

residence status, income

(1) esthetic preferences (SC values, BP landscape

characteristics) (2) WUI growth (BP proximity to risk)

(3) resource utilization (SC values) (4) collective

experiences (SC social interactions)

Economic shifts SD No Resource dependence,

residence status, income

(1) resource utilization (SC values) (2) SBB population

decline (BP cycle)

Concern about forest

regeneration

SD Yes Resource dependence,

residence status, income

(1) SBB population decline (BP cycle) (2) acceptance (SC

attitude) (3) esthetic preferences (SC values, BP

landscape characteristics) (4) forest management (SC

values)

Place disruption SC Yes Resource utilization,

amenity values, agency

trust, adaptation

(1) landscape change, SBB population decline, and spatial

factors (BP) (2) SBB experience (SD residence status)

Mitigation actions SC Yes Resource utilization,

community participation,

empathy

(1) time to develop relationships (SD residence status) (2)

financial opportunities (SD income) (3) distance

between places (BP landscape characteristics, SD

population density)

BP biophysical, SD sociodemographic, SC sociocultural

Environmental Management

123

Author's personal copy

residents, contributed to actions. Unsurprisingly, residence

status and distance between residents were important for

facilitating formal and informal social interactions with

income often acting as a barrier to interactions.

Discussion

The integration of the three dimensions can be understood

and visualized in a matrix context. Figure 2 presents a

modified version of Luloff and others’s (2007) typological

framework adapted for the Kenai Peninsula. This matrix

approach to understanding people, fire, and forests contrib-

utes to our understanding of wildfire risk perceptions within

the context of challenges and opportunities occurring in the

study communities between 2003 and 2007. Findings pro-

vide new insights into the complexity of public response to

wildfire and whether or not risk perceptions change over

time. In addition, findings illustrate use of the matrix

approach with qualitative interpretation to provide enhanced

understanding of interactional effects. Finally, research

findings as explained by the three dimensions of the matrix

inform work on resiliency in fire-prone communities. Sev-

eral conclusions emerged from the findings.

Local Knowledge and Experience with the Landscape

The restudy found a consistent trend in perceptions that

SBB concern had declined over time to be replaced by

concerns about development. This finding underscores

spatial and temporal processes related to residents’ expe-

riences and understanding of ecological processes,

including the role of fire in the landscape and probability of

harm (Beebe and Omi 1993; Brenkert-Smith 2011; Cohn

and others 2008; Daniel 2006; Gardner and others 1987;

Paveglio and others 2011; Steelman 2008; Werner and

others 2006). Our study further suggests some public

groups hold far more detailed knowledge about relation-

ships between wildfire and a variety of disturbance

impacts, a finding both supportive of earlier work (Nelson

and others 2005) and in conflict with other studies

(McCaffrey and others 2013). This does not suggest

knowledge was the most important factor in concerns about

specific outcomes or mitigation strategies (Blanchard and

Ryan 2007; Vaske and others 2007). Rather, experience

with the fire landscape and associated perceptions of vul-

nerability are moderated by localized factors, such as res-

idence status, agency trust, and resource utilization

perspectives that vary between communities.

As Sturtevant and Jakes (2008) noted, local knowledge

and experience play a critical role in collaborative resource

decision-making and wildfire preparation. Although resi-

dents’ understanding of landscape processes might coarsely

reflect that of experts, layperson assessments take into

account social and physical contexts of place. If properly

interpreted and utilized, local experience can precisely

identify and reduce wildfire risk (David 1990). Residents’

observations of the relationships between various ecological

phenomena and wildfire provide the basis for future study.

Residence Status

Findings from the literature are inconsistent regarding resi-

dence status (permanent or part-time, but not tenure).

Nonetheless, the Kenai studies highlighted the role of time in

creating opportunities to gain knowledge of ecological pro-

cesses, observe forest risks leading to wildfire, become

familiar with fuels management on public lands, and

implement individual risk mitigation strategies (Bright and

Burtz 2006; Collins and Bolin 2009). Perhaps most impor-

tantly, time spent in the community informed the develop-

ment of social interactions and ensuing communication of

interactional factors between resident groups, including

information on fire and fuels management (Brenkert-Smith

2010; Cutter and others 2008; Tierney and others 2001).

Our findings build upon earlier work by demonstrating

the ways residence status interacts with themes in each

dimension of the matrix approach. Few existing studies

focus on residence status; more research is needed to

identify and measure the processes leading to new/seasonal

residents’ involvement in community activities, including

collective wildfire mitigation programs and how this

influences community resiliency. Such studies should focus

Fig. 2 Management of SBB in the Kenai Peninsula illustrates the

usefulness of the three-dimensional matrix of biophysical, sociode-

mographic, and sociocultural factors in understanding the interaction

of people, fire, and forests

Environmental Management

123

Author's personal copy

not only on passive involvement in incentive programs, but

also leadership development and conflict resolution

between new and long-time residents to achieve mitigation

goals (Sturtevant and Jakes 2008).

Sense of Place

While several studies have addressed defensible space in

landscaping activities, little research in the wildfire risk

perception literature has focused on sense of place

(exceptions are Brenkert-Smith 2006; Bihari and Ryan

2012). Sense of place is informed by knowledge of and

emotional connections to the local landscape and is

critical to facilitating collective definitions of risk

(Kemmis 1990). The matrix approach fits well with the

sense of place concept because it allows for the over-

lapping dimensions that define place. In the Kenai rest-

udy, sense of place was a key aspect to influencing local

knowledge of biophysical factors and facilitating social

interactions. In particular, the disruption of a shared sense

of place, resulting from dramatic sociodemographic and

biophysical changes in the community, influenced diverse

attitudes toward SBB timber salvage, defensible space,

and scenic vistas. Because place is a collection of phys-

ical attributes, values, and emotional attachments, its

meaning varies across resident groups and communities.

Like the role of residence status, there is a need to further

study how sense of place influences collective wildfire

risk perceptions and response.

Social Interactions and Local Capacities

Referring to the wildfire mitigation paradox, McCaffrey

(2008) suggested inconsistencies in wildfire preparedness

result because the community is at greater risk than the

individual. Taking this a step further, the matrix approach

proposes heightened community risk results from social

complexity in the WUI (Jakes and others 2007; Paveglio

and others 2009). For example, Kenai residents’ per-

spectives about their communities and landscapes chan-

ged over time with the arrival of new social values,

economic change, and as effects of SBB played out. In

turn, they expressed a moderated but informed con-

sciousness about wildfire which was overlaid by other

dimensions of the matrix (Table 3). While this com-

plexity has been interpreted as leading to vulnerabilities

(Blaikie and others 1994), restudy informants suggested

collective capacities mature over time through interac-

tional processes that develop sense of place, leadership,

participation, and a common vision of community

(Sturtevant and Jakes 2008).

Conclusion

The Kenai restudy’s grounding in the three dimensional

matrix approach enabled a holistic perspective of wildfire

risk perceptions, which occurred within communities

defined by people and place (Luloff and others 2007;

McCaffrey and others 2011). Interactions among biophys-

ical, sociodemographic, and sociocultural factors differed

in their effects and degree of influence throughout the

matrix. In turn, the three dimensions held varying degrees

of influence over community resiliency, a primary goal of

current wildfire preparedness policy (USDA-USDI 2009).

Further research is needed to identify these degrees of

influence. As well, a synthesis of previous research results

into these three dimensions would be a valuable contribu-

tion to the literature and help identify remaining gaps in

our understanding of wildfire risk perceptions. The matrix

approach is a conceptual tool stakeholders can use to

identify challenges and opportunities in collaborative

planning and management. As McCaffrey and others

(2013) noted, fire management is a social process. An

understanding of the key biophysical, sociodemographic,

and sociocultural dynamics is integral to minimizing neg-

ative consequences of fire on human and natural

communities.

Acknowledgments This research was supported by funding from

the Pacific Northwest Research Station, Forest Service, U.S.

Department of Agriculture. In addition, we are grateful for the

valuable comments and conceptual insights provided by anonymous

reviewers.

References

Amacher GS, Malik AS, Haight RG (2005) Forest landowner

decisions and the value of information under fire risk. Can J

For Res 35:2603–2615

Beebe GS, Omi PN (1993) Wildland burning: the perception of risk.

J For 91(9):19–24

Berg EE (2006) Landscape drying, spruce bark beetles and fire regimes

on the Kenai Peninsula, Alaska. For Ecol Manag 227:219–232

Bihari M, Ryan R (2012) Influence of social capital on community

preparedness for wildfires. Landsc Urban Plan 106(3):253–261

Blaikie P, Cannon T, Davis I, Wisner B (1994) At risk: natural

hazards, people’s vulnerability, and disasters. Routledge,

London

Blanchard B, Ryan R (2007) Managing the wildland urban interface

in the Northeast: perceptions of fire risk and hazard. North J

Appl For 24(3):203–208

Brenkert-Smith H (2006) The place of fire. Nat Hazards Rev 7(3):

105–113

Brenkert-Smith H (2010) Building bridges to fight fire: the role of

informal social interactions in six Colorado wildland–urban

interface communities. Int J Wildland Fire 19(6):689–697

Brenkert-Smith H (2011) Homeowners’ perspectives on the parcel

approach to wildland fire mitigation: The role of community

context in two Colorado communities. J For 109(4):193–200

Environmental Management

123

Author's personal copy

Brenkert-Smith H, Champ PA, Flores N (2006) Insights into wildfire

mitigation decisions among wildland–urban interface residents.

Soc Nat Res 19(8):759–768

Brenkert-Smith H, Dickinson KL, Champ PA, Flores N (2012) Social

amplification of wildfire risk: the role of social interactions and

information sources. Risk Anal. doi:10.1111/j.1539-6924.2012.

01917.x

Bright AD, Burtz RT (2006) Firewise activities of full-time versus

seasonal residents in the wildland–urban interface. J For 104(6):

307–315

Brown BB, Perkins DD (1992) Disruptions in place attachment. In:

Altman I, Low SM (eds) Place attachment. Plenum Press,

New York

Burns MR, Taylor JG, Hogan JT (2008) Integrative healing: the

importance of community collaboration in postfire recovery and

prefire planning. In: Martin WE, Raish C, Kent B (eds) Wildfire

risk: human perceptions and management implications. Resources

for the Future, Washington DC, pp 81–98

Burnside R (2011) Forest health update: a decade of beetle activity in

Alaska. Kenai Peninsula Borough Spruce Bark Beetle Mitigation

Program, http://www2.borough.kenai.ak.us/SBB/pages/beetlepages/

kenaihistory.html. Accessed 14 Aug 2012

Carroll MS, Cohn P (2007) Community impacts of large wildfire

events: events, issues and dynamics during fires. In: Daniel T,

Carroll, MS, Moseley, C, Raish C (eds) People fire and forests: a

synthesis of wildfire social science. Oregon State University

Press, Corvallis, pp 104–123

Carroll MS, Cohn PJ, Seeholtz DN, Higgins LL (2005) Fire as a

galvanizing and fragmenting influence on communities: the case

of the Rodeo-Chediski fire. Soc Nat Res 18:301–320

Cohn PJ, Williams DR, Carroll MS (2008) Wildland–urban interface

residents’ views on risk and attribution. In: Martin WE, Raish C,

Kent B (eds) Wildfire risk: human perceptions and management

implications. Resources for the Future, Washington DC, pp 81–98

Collins TW (2008) What influences hazard mitigation? Household

decision making about wildfire risks in Arizona’s White

Mountains. Prof Geogr 60:4508–4526

Collins TW, Bolin B (2009) Situating hazard vulnerability: people’s

negotiations with wildfire environments in the U.S. Southwest.

Environ Manag 44(3):441–455

Creswell JW (1998) Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing

among five traditions. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Cutter SL, Barnes L, Berry M, Burton C, Evans E, Tate E, Webb J

(2008) A place based model for understanding community

resilience to natural disasters. Environ Change 18:598–606

Daniel TC (2006) Public preferences for future conditions in

disturbed and undisturbed northern forest sites. In: McCaffrey

S (ed) The public and wildland fire management: Social science

findings for managers. General Technical Report NRS-1.

Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northern Research

Station, Newtown Square, pp 53–61

Daniel TC, Orland B, Hetherington J, Paschke JL (1991) Public

perception and attitudes regarding spruce bark beetle damage to

forest resources on the Chugach National Forest, Alaska. Final

Report to U.S. Forest Service, Forest Pest Management,

Anchorage, Alaska, R10

Daniel T, Weidemann E, Hines D (2003) Assessing public tradeoffs

between fire hazard and scenic beauty in the wildland–urban

interface. In: Jakes P (ed) Homeowners, communities, and wildfire:

science findings from the National Fire Plan USDA Forest Service

General Technical Report NC-231, USDA-USFS, pp 36–44

David JN (1990) The wildland–urban interphase: paradise of

battlegrounds? J For 88(1):26–31

Donovan GH, Champ PA, Butry DT (2007) Wildfire risk and housing

prices: a case study from Colorado Springs. Land Econ 83(2):

217–233

Drabek T, Key WH, Erickson PE, Crowe JL (1975) The impact of

disaster on kin relationships. J Marriage Fam 34:481–494

Egan AF, Luloff AE (2000) The exurbanization of America’s forests.

J For 98(3):26–30

Elmendorf WF, Luloff AE (2001) Using qualitative data collection

methods when planning for community forests. J Arboric 27(3):

139–151

Everett Y, Fuller M (2011) Fire safe councils in the interface. Soc Nat

Res 24(4):319–333

Field DR, Burch WR Jr (1991) Rural sociology and the environment.

Social Ecology Press, Middleton

Firey WI (1999) Man, mind and land: a theory of resource use. Social

Ecology Press, Middleton

Fleeger WE (2008) Collaborating for success: community Wildfire

protection planning in the Arizona White Mountains. J For

106(2):78–82

Flint CG (2006) Community perspectives on spruce beetle impacts on

the Kenai Peninsula, Alaska. For Ecol Manag 227:207–218

Flint CG (2007) Changing forest disturbance regimes and risk

perceptions in Homer, Alaska. Risk Anal 27(6):1597–1608

Flint CG, Haynes R (2006) Managing forest disturbances and

community response: lessons from the Kenai Peninsula, Alaska.

J For 104(3):269–275

Flint CG, Luloff AE (2007) Community activeness in response to

forest disturbance in Alaska. Soc Nat Res 20(5):431–450

Freudenberg WR (2001) Risk, responsibility, and recreancy. Res Soc

Probl Public Policy 9:87–108

Gardner PD, Cortner HJ, Widaman K (1987) The risk perception and

policy response toward wildland fire hazards by urban home-

owners. Landsc Urban Plan 14:163–172

Gordon JS, Stedman RC, Matarrita-Cascante D, Luloff AE (2010)

Fire perception in rapid growth communities. Rural Sociol 75(3):

455–477

Grayzeck-Souter S, Nelson KC, Brummel RF, Jakes P, Williams DR

(2009) Interpreting federal policy at the local level: the

wildland–urban interface concept in wildfire protection planning

in the eastern United States. Int J Wildland Fire 18:278–289

Heckathorn DD (2002) Respondent-driven sampling II: deriving valid

estimates from chain-referral samples of hidden populations. Soc

Probl 49(1):11–34

Hicke J, Johnson MC, Hayes JL, Haiganoush KP (2012) Effects of

bark beetle-caused tree mortality on wildfire. For Ecol Manag

271:81–90

Jakes P, Nelson KC (2007) Community interaction with large

wildland fire events: critical initiatives prior to the fire. In:

Daniel T, Carroll M, Moseley C, Raish C (eds) People, fire and

forests. Oregon State University Press, Corvallis, pp 91–103

Jakes P, Kruger L, Monroe M, Nelson K, Sturtevant V (2007)

Improving wildfire preparedness: lessons from communities

across the U.S. Hum Ecol Rev 14(2):188–196

Jakes PJ, Nelson KC, Enzler SA, Burns S, Cheng AS, Sturtevant V,

Williams DR (2011) Community wildfire protection planning: is

the Healthy Forest Restoration Act’s vagueness genius? Int J

Wildland Fire 20:350–363

Jolly WM, Parsons R, Varner JM, Butler BW, Ryan KC, Glucker CL

(2012) Do mountain pine beetle outbreaks change the probability

of active crown fire in lodgepole pine forests? Comment.

Ecology 93(4):941–946

Kemmis D (1990) Community and the politics of place. University of

Oklahoma Press, Norman

Kenai Peninsula Borough Office of Emergency Management (2011)

Fire information. http://www.borough.kenai.ak.us/emergency-

mgmt/fire. Accessed 26 Nov 2012

Krannich RS, Humphrey CR (1986) Using key informant data in

comparative community research: an empirical assessment.

Sociol Methods Res 14(4):473–493

Environmental Management

123

Author's personal copy

Krannich K, Petrzelka P, Brehm J (2003) Tourism and natural

amenity development: real opportunities? In: Brown D, Swanson

L (eds) Challenges for rural America in the twenty-first century.

Penn State University Press, University Park, pp 190–199

Kruse J, Pelz R (1991) Developing a public consensus on the

management of spruce beetles on the Kenai Peninsula. Report

for Alaska Division of Forestry. Institute of Social and Economic

Research, University of Alaska, Anchorage

Landis PH (1997) Three iron mining towns: a study in cultural

change. Social Ecology Press, Middleton

Luloff AE, Field D, Krannich R, Flint C (2007) A matrix approach for

understanding people, fire, and forests. In: Daniel T, Carroll M,

Moseley C, Raish C (eds) People, fire and forests: a synthesis of

wildfire social science. Oregon State University Press, Corvallis,

pp 207–216

McCaffrey S (2008) Understanding public perspectives of wildfire risk.

In: Daniel T, Carroll M, Moseley C, Raish C (eds) People, fire and

forests. Oregon State University Press, Corvallis, pp 11–22

McCaffrey SM, Stidham M, Toman E, Shindler B (2011) Outreach

programs, peer pressure, and common sense: what motivates

homeowners to mitigate wildfire risk? Environ Manag 48(3):475–488

McCaffrey S, Toman E, Stidham M, Shindler B (2013) Social science

research findings related to wildfire management: an overview of

recent findings and future research needs. Int J Wildland Fire

22:15–24

McFarlane BL, McGee TK, Faulkner H (2011) Complexity of

homeowner wildfire risk mitigation: an integration of hazard

theories. Int J Wildland Fire 20(8):921–931

McGee TK, McFarlane B, Varghese J (2009) An examination of the

influence of hazard experience on wildfire risk perceptions and

adoption of mitigation measures. Soc Nat Res 22:308–323

Nelson KC, Monroe MC, Johnson JF (2005) The look of the land:

homeowner landscape management and wildfire preparedness in

Minnesota and Florida. Soc Nat Res 18(4):321–336

Paveglio TB, Jakes PJ, Carroll MS, Williams DR (2009) Under-

standing social complexity within the wildland–urban interface:

a new species of human habitation? Environ Manage 43(6):

1085–1095

Paveglio TB, Carroll MS, Absher J, Robinson E (2011) Symbolic

meaning of wildland fire: a study of residents in the U.S. Inland

Northwest. Soc Nat Res 24(1):18–33

Radeloff VC, Hammer RB, Stewart SI, Fried JS, Holcomb HH,

McKeefry JF (2005) The wildland–urban interface in the United

States. Ecol Appl 15(3):799–805

Rodriguez-Mendez S, Carroll MS, Blatner K, Findley AJ, Walker GB,

Daniels SE (2003) Smoke on the hill: a comparative study of

wildfire and two communities. West J Appl For 18:60–70

Shindler B, Toman E (2003) Fuel reduction strategies in forest

communities: a longitudinal analysis of public support. J For

101(6):8–15

Steelman TA (2008) Addressing the mitigation paradox at the

community level. In: Daniel T, Carroll M, Moseley C, Raish C

(eds) People, fire and forests. Oregon State University Press,

Corvallis, pp 64–80

Steelman TA, Kunkel GF (2004) Effective community responses to

wildfire threats: lessons from New Mexico. Soc Nat Res 17(8):

679–699

Sturtevant V, Jakes P (2008) Collaborative planning to reduce risk.

In: Daniel T, Carroll M, Moseley C, Raish C (eds) People, fire

and forests. Oregon State University Press, Corvallis, pp 44–63

Sturtevant V, McCaffrey S (2006) Encouraging wildland fire

preparedness: Lessons learned from three wildfire education

programs. In: McCaffrey S (ed) The public and wildland fire

management: Social science findings for managers, US For.

Serv. Gen. Tech. Rep. NRS-1, Northern Research Station,

Newtown Square, PA, pp 125–136

Tierney KJ, Lindell MK, Perry RW (2001) Facing the unexpected:

disaster preparedness and response in the United States. Joseph

Henry Press, Washington D.C

United States Department of Agriculture and the U.S. Department

of the Interior (2000) National fire plan: a report to the

president in response to the wildfires of 2000. USDA & USDI,

Washington, DC

United States Department of Agriculture and the U.S. Department of

the Interior (2001) Urban wildland interface communities within

the vicinity of federal lands that are at high risk from wildfire.

Federal Register, vol 66, no 3. USDA & USDI, Washington, DC

United States Department of Agriculture and the U.S. Department of the

Interior (2009) Quadrennial fire review 2009: final report. www.

iafc.org/files/wild_QFR2009Report.pdf. Accessed 12 April 2013

Vaske JJ, Absher JD, Bright AD (2007) Salient value similarity:

social trust and attitudes toward wildland fire management

strategies. Hum Ecol Rev 14(2):223–233

Waugh WL Jr, Streib G (2006) Collaboration and leadership for

effective emergency management. Public Admin Rev 66(1):

131–140

Werner RA, Hosten EH, Matsuoka SM, Burnside RE (2006) Spruce