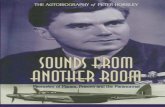

Peter Horsley - Sounds From Another Room.pdf - Avalon Library

Payeftjauemawyneith’s Shabti (UC 40093) and Another from Nebesheh

-

Upload

acorjordan -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of Payeftjauemawyneith’s Shabti (UC 40093) and Another from Nebesheh

161

Payeftjauemawyneith’s Shabti (UC 40093) and Another from Nebesheh

Hussein Bassir and Pearce Paul creasman

Abstract

A shabti of Saite date, UC 40093, bearing the name Payeftjauemawyneith, is for the first time described, transcribed, transliterated, and translated. Some publications conflate it with another shabti that bears the same name. This article explores whether they belonged to the same man (who may be a high-ranking official who served under Apries and Ama-sis), and possible locations for his tomb.

Introduction1

Shabti2 UC 40093 (Petrie No. 546) (figs. 1–4),3 of Saite date, is currently displayed at the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology and University College London in Case M, Drawer 6. The catalog of named shabtis in the Petrie Museum transcribes the owner’s name as “PA.f-TAw-Nt (aA n xA),”4 and this abbreviated form, “Peftuaneith,”

1 The authors are greatly indebted to Stephen Quirke and Ivor Pridden for providing the photographs published here, as well as permission to publish this shabti. Many thanks are due to Karl Jansen-Winkeln, David Klotz, and Noreen Doyle for reading drafts of this paper and making valuable comments. We are very grateful to Vassil Dobrev and Bernard Mathieu for discussing with us the discovery of two shabtis at Tabbet al-Guech (South Saqqara). Thanks are also due to Vincent Razanajao, Editor of the Topographical Bibliography and Keeper of the Archive of the Griffith Institute, for sending to us page three of Griffith’s sixth notebook for Nebesheh, and to Paolo Del Vesco, Marie Curie Research Fellow at the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, for his aid related to this matter. Finally, we are very grateful to Christiane Ziegler, Guillemette Andreu-Lanoë, Elisabeth David, and Audrey Viger of the Louvre Museum for providing the photograph of Louvre statue A 93 and allowing us to publish it.

2 For typology of the shabti figures and the shabti phraseology, see H. Schneider, Shabtis: An Introduction to the History of An-cient Egyptian Funerary Statuettes with a Catalogue of the Collection of Shabtis in the National Museum of Antiquities at Leiden, 3 vols. (Leiden, 1977); he mentions this shabti in vol. I, 341. The oldest version of the shabti spell, CT Spell 472, was inscribed on some Middle Kingdom coffins; see Schneider, Shabtis 1, 46–62, § 7–8; see also H. Stewart, Egyptian Shabtis (London, 1995); J. Taylor, Death and the Afterlife in Ancient Egypt (Chicago, 2001) 112–35; H. Milde, “Shabtis,” in W. Wendrich, ed., UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology (Los Angeles, 2012), http://digital2.library.ucla.edu/viewItem.do?ark=21198/zz002bwv0z; D. Spanel, “Funerary Fig-ures,” in D. Redford, ed., The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt 1 (New York, 2001), 567–70; H. Schlögl, “Uschebti,” LdÄ 6 (Wi-esbaden, 1986), 896–99; A. Awadalla, “Une ouchebti de Wxy à Heliopolis,” GM 132 (1993), 7–12. For Chapter 6 of the Book of the Dead, see E. Von Dassow, ed., The Egyptian Book of the Dead: The Book of Going Forth by Day: Being the Papyrus of Ani (Royal Scribe of the Divine Offerings), Written and Illustrated circa 1250 B.C.E., by Scribes and Artists Unknown, Including the Balance of Chapters of the Books of the Dead Known as the Theban Recension, Compiled from Ancient Texts, Dating Back to the Roots of Egyptian Civilization, trans. R. Faulkner and O. Goelet (San Francisco, 1994), 101 [6]; T. Allen, BD, 8; see also G. Lapp, The Papyrus of Nu (BM EA 10477) (London, 1997), 73 [6], pl. 62; E. Hornung, Das Totenbuch der Ägypter (Zurich, 1979), 47–48, 417.

3 See W. Petrie, Shabtis (Warminster, 1974 [1935]), pls. 12, 22, 42, no. 546.4 H. Stewart, “Index to the Named Shabtis in the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology at University College London,”

http://www.digitalegypt.ucl.ac.uk/downloads/shabtis.pdf, accessed 22 October 2013, 18.

Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt, Vol. 50, pp. 161–69doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.5913/jarce.50.2014.a022

162 JARCE 50 (2014)

Fig.1. Front of shabti UC 40093 (photograph courtesy of the Petrie Museum).

Fig. 2. Back of shabti UC 40093 (photograph courtesy of the Petrie Museum).

is often used.5 An early rendering of the name was “Pef ā (?) net.”6 Ramadan El-Sayed7 reads it as “Peftaouneith;” Jacques-F. Aubert and Liliane Aubert,8 “Païeftchaouaneith;” and E. Jelínková-Reymond,9 “Pef-tow-Neith.” Georges Posener10 interprets the name as “Payeftjauemawyneith.” Despite suggestions that the name might be “Pef-zaou-di-Neith,”11 “Pef-tjau-awy-neith,”12 “Payeftjauerawyneith,”13 or “Payeftjauheramyneith,”14 the full

5 M. Lichtheim, Ancient Egyptian Literature 3, The Late Period (Berkeley-Los Angeles, 2006 [1980]), 33–36.6 F. Griffith, “The Inscriptions,” in W. Petrie, Nebesheh (Am) and Defenneh (Tahpanhes) (London, 1888), 37.7 R. El-Sayed, Documents relatifs à Saïs et ses divinités (Cairo, 1975), 245, §25, (d).8 J.-F. Aubert and L. Aubert, Statuettes égyptiennes: chouabtis, ouchebtis (Paris, 1974), 226.9 E. Jelínková-Reymond, “Quelques recherches sur les réformes d’Amasis,” ASAE 54 (1957 [1956]), 275–87.10 G. Posener, La première domination perse en Egypte: Recueil d’inscriptions hiéroglyphiques (Cairo, 1936), 11.11 H. Gauthier, “À travers la Basse-Égypte,” ASAE 22 (1922), 81; see also H. Bakry, “Two Saite Monuments of Two Master

Physicians,” OrAnt 9 (1970), 326.12 Lichtheim, AEL 3, 33–36 [n. 2]; this is very close to the reading of P3.f-t3w-Nt by Stewart, “Index to the Named Shabtis in

the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology at University College London,” 18.13 G. Lefebvre, “Textes égyptiens du Louvre,” RdÉ 1 (1933), 94, n. 4.14 J. Clère, “Notes d’onomastique à propos du dictionnaire des noms de personnes de H. Ranke,” RdÉ 3 (1938), 105; Bakry,

BASSIR AND CREASMAN 163

Fig. 3. Right side of shabti UC 40093 (photograph courtesy of the Petrie Museum).

Fig. 4. Left side of shabti UC 40093 (photograph courtesy of the Petrie Museum).

form should read PA(y)=f-TAw-(m)-a(wy)-Njtt “Payeftjauemawyneith,” meaning “His breath is in the hands of Neith.”15 “Payeftjauemawyneith,” the most reasonable of all the interpretations, is employed here. It was very common name in the Late period,16 known from many individuals in the Saite period.17

“Two Saite Monuments of Two Master Physicians,” 326; P. Ghalioungui, The Physicians of Pharaonic Egypt (Cairo-Mainz, 1983), 31.15 H. Ranke, PN I, 128 [2], lists a similar name, pA.f-TAw(m-) a.wj-n-(?)njt “sein Atem ist in den Händen der Neith.” For more on

names in ancient Egyptian traditions, see G. Vittmann, “Personal Names: Structures and Patterns,” in E. Frood and W. Wendrich, eds., UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology (Los Angeles, 2013), http://digital2.library.ucla.edu/viewItem.do?ark=21198/zz002dwqsr (accessed 3 December 2013); H. Ranke, “Personal Names: Function and Significance,” in E. Frood and W. Wendrich, eds., UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology (Los Angeles, 2013), http://digital2.library.ucla.edu/viewItem.do?ark=21198/zz002dwqr7.

16 See, for instance, M. Mogensen, Stèles égyptiennes au Musée national de Stockholm (Copenhague, 1919), 69 [58]; Posener, La première domination perse en Égypte, 164, n. 5, 11. Also BM EA 21748, the upper part shabti belonging to an individual probably named p(A.)f-TAw-?- (Pef-tjau-?-) from the Late period (Dynasty 30); see Schneider, Shabtis 2, 169 [5.3.1.89] and Ranke, PN 1, 127 [21]. Coincidentally, Paolo Del Vesco (personal communication, 4 November 2013) points out that BM EA 21748 reportedly came from Nebesheh.

17 El-Sayed, Documents relatifs à Saïs et ses divinités, 230, 235, 245, 266; M. Raven and W. Taconis, Egyptian Mummies: Radiological

164 JARCE 50 (2014)

Description

Measuring 13.6 cm in height, this upper part of a very carefully modeled, faience shabti with blue-green glaze18 represents Payeftjauemawyneith in the typical mummy form. His arms cross right over left on his chest; his clenched hands protrude from a shroud to hold in the left a pick and in the right a hoe and the twisted rope of a small seed-bag that is slung over his left shoulder. These implements are depicted in relief. Although shabtis were mass-produced, Payeftjauemawyneith’s smiling face,19 square in appearance, is more personalized, with many late Saite features.20 He wears his plain, tripartite wig low on the forehead. His sharp eyebrows and the cosmetic lines of his almond-shaped eyes are rendered in relief. His cheeks are full and fleshy on either side of a long nose; below his thick lips is a square, wide chin. Large ears protrude as if pressed out by the wig, and his Osirian beard is cleverly plaited. Like other Late period faience shabtis,21 this was made in a two-piece pottery mold. The fragment has an incomplete back pillar and probably once had a trapezoidal base.22

The remaining hieroglyphic text, five horizontal lines read right to left, is neatly incised. A version of Chapter 6 of the Book of the Dead was usually inscribed on this kind of magical figurine, which served its dead owner by carrying out on his behalf all the manual labor required of him in the afterlife. How-ever, because the lower portion of the shabti is missing, only the beginning of text is preserved.

Text

Atlas of the Collections in the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden. Papers on Archaeology of the Leiden Museum of Antiquities, Egyptology 1 (Turnhout, 2005), cat. no. 17.

18 However, Stewart, “Index to the Named Shabtis in the Petrie Museum,” 18, states that is made of blue faience, as does Petrie, Shabtis, pl. 22.

19 See C. Aldred, Egyptian Art in the Days of the Pharaohs, 3100–320 BC (London, 1980), 228; H. Schäfer, Principles of Egyptian Art (Oxford, 1974), 292. For more on Late period Egyptian art, see J. Josephson, “Egyptian Sculpture of the Late Period Revis-ited,” JARCE 34 (1997), 1–20; B. Bothmer, H. De Meulenaere, and H. Müller, Egyptian Sculpture of the Late Period 700 B.C. to A.D. 100 (Brooklyn, 1973 [1960]); B. Bothmer and M. Cody, Egyptian Art: Selected Writings of Bernard V. Bothmer (New York, 2004); J. Josephson, Egyptian Royal Sculpture of the Late Period, 400–246 B.C. (Mainz, 1997); J. and M. Eldamaty, CG 8601–48649 (Cairo, 1999); K. Mysliwiec, Royal Portraiture of the Dynasties XXI–XXX (Mainz, 1988).

20 For more on Saite shabtis and their iconographic features, see N. Reeves, “An Unpublished Royal Shabti on the 26th Dynas-ty,” GM 154 (1996), 93–97; A. Bolshakov, “Miscellanea Hermitagiana 4 (Three Ushabtis Recently Bequeathed to the Hermitage Museum),” GM 156 (1997), 27–31; J. van Oostenrijk, “Individuality versus Uniformity: Twenty-Sixth Dynasty Shabti Groups from Saqqara,” Saqqara Newsletter 10 (2012), 58–61; J. van Oostenrijk,“Horkhebi Revised: A Description of a Late period Shabti from Saqqara,” BSEG 28 (2008–10), 119–27; J. van Oostenrijk, “Iconographic Changes on Late Period Shabti Groups from Saqqara.” Unpublished paper available at https://www.academia.edu/1487065/Iconographic_Changes_on_Late_Period_Shabti_Groups_from_Saqqara (accessed 3 December 2103).

21 For more on the concept of the shabti during the Late period, see Schneider, Shabtis 1, 319–45. 22 See Aubert and Aubert, Statuettes égyptiennes, 208; Taylor, Death and the Afterlife in Ancient Egypt, 131; G. Janes, Shabtis, A

Private View: Ancient Egyptian Funerary Statuettes in European Private Collections (Paris, 2002), xvii.

BASSIR AND CREASMAN 165

Transliteration:

1. Dd mdw jn wsjr aA n xA PA(y)=f-tAw-(m)-a(wy)-Njtt j wSbty.w jpn 2. jr jp.tw wja r jr(t) kA(t) nb(t) jr(rt) jm m Xr-nTr jw=tw 3. (Hr) Hwj sDb.wb jm m z r Xrc.wt=f mk 4. wj kA=Tn jp.tw=Tn r n[w]d

5. nb [jrt] jm r srd e sxwt…f

Translation:

1. Words spoken by Osiris, great of the xA-hall Pa(y)eftjau(em)a(wy)neith: “O these shabtis, 2. if one counts me off to do any work that has to be done there in the realm of the dead, 3. and when one implants obstacles therein, as a man at his duties, ‘here 4. I am,’ you shall say when you are counted off at any occasion 5. [of acting] there, to cultivate the fields, … … ….”23

Notes on the Inscription:

a) Here wsjr followed by the name of deceased usually appear rather than a pronoun.b) For this phrase, Hwj sDb, see B. Gunn, “The Stela of Apries at Mîtrahîna,” ASAE 27 (1927),

227–28.c) Written as a broad isosceles triangle for T28 (butcher’s block).d) Only the n is written at the end of line 4.e) Written srwd for srd; see Wb. IV, 205.f) For a similar Saite shabti formula of Psamtikmeryptah (contemp. Amasis) from Saqqara, see

Schneider, Shabtis 2, 181 (5.3.1.149) and 3, fig. 5 (VII/6 = 5.3.1.149).

Discussion

In the current index of named shabtis in the Petrie Museum,24 the origin of UC 40093 is given as Nebesheh in the Eastern Delta.25 However, the publication cited for this object, namely, Petrie’s publi-cation of the site,26 refers to a different shabti,27 of which little is known. Of this other shabti, only the owner’s title, name, and genealogy are published, without any further description or the context of its discovery, although Griffith does attribute it to the Saite period.28 The only illustration is Griffith’s recording of (part of?) its inscription, which he interpreted as “Pef ā (?) net deceased, (son of) the secem Hau of Sais ? Sebek (or Se sebek) and of …” (fig. 5).29

23 Janes, Shabtis, xix, cites a complete version of Chapter 6 of the Book of the Dead, which usually reads i wSbty ipn ir ip.tw ir Hsb.tw Wsir (T & N) r irt kAt nb ir im m Xrt-nTr ist Hw sDb(w) im m s r Xrt.f mk wi kA.tn ip.tw tn r nw nb irt im r srwD sxt r smHy wDbw r Xnt Say r imntt iAbtt Ts pXr mk wi kA.tn and is typically translated: “O this/these ushebti(s), if one counts, if one reckons the Osiris, (Title and Name of deceased) to do all the works which are wont to be done there in the God’s land—now indeed obstacles are implanted therewith—as a man at his duties, ‘here I am,’ you shall say when you are counted off at any time to serve there, to cultivate the fields, to irrigate the riparian lands, to transport by boat the sand of the east to the west and vice-versa; ‘here I am,’ you shall say.” See also Allen, The Book of the Dead, 8; Von Dassow, ed.,The Egyptian Book of the Dead, 101 [6]; Lapp, The Papyrus of Nu (BM EA 10477), 73 [6], pl. 62; Hornung, Das Totenbuch der Ägypter, 47–48, 417.

24 Stewart, “Index to the Named Shabtis in the Petrie Museum,” 18.25 For more on this site, see J. Baines and J. Málek, Cultural Atlas of Ancient Egypt (New York, 2000), 176.26 Petrie, Nebesheh.27 Griffith, “The Inscriptions,” in Petrie, Nebesheh, 36–37, pl. 13 b.28 Griffith, “The Inscriptions,” 37, pl. 13 b.29 Griffith, “The Inscriptions,” 37.

166 JARCE 50 (2014)

jmy rA pr wr PA(y)=f-TAw-(m)-a(wy)-Njtt […] [xrp] Hwwt sA-sbk msj n […]“High steward Payeftjauemawyneith, [son of the director of] the palaces Sasobek, born of […].”

Griffith’s field notes reveal that this second shabti, which was found with the additional fragment of a “small one painted,” came “from [the/a] hosh (?) [i.e., courtyard] in town on S[outh] side of mound,” with the additional notation “fine[ly] impressed.”30 The whereabouts of this particular shabti, which for convenience will be referred to here as “Griffith’s shabti,” are unknown to us. Regrettably, neither figurine is among those pictured (as sketches) in Petrie’s publication of his excavations at Nebesheh.31

Although neither field notes nor Petrie’s later publication of UC 4009332 confirm that UC 40093 was found at Nebesheh, by no later than 1974 it was attributed to that site,33 and subsequently this assign-ment has persisted.34 At least once in publication, Griffith’s shabti has been directly conflated with UC 40093.35

Who might the owner(s) of the shabtis in question here have been? Both objects have been attributed to one particular Payeftjauemawyneith of the Saite period, a high official who served under Apries and Amasis.36 This Payeftjauemawyneith has four37 well-attested statues inscribed with biographical texts:

30 F. Griffith, Nebesheh notebook 6, 3 (no. 3), Griffith Institute Archive, Oxford. We are grateful to Vincent Razanajao (per-sonal communication, 15 November, 2013) for this information.

31 Petrie, Nebesheh, pls. 1, 2, 12. 32 Petrie, Shabtis, pls. 12, 22, 42, no. 546.33 Aubert and Aubert, Statuettes égyptiennes, 226.34 Schneider, Shabtis I, 341; Stewart, “Index to the Named Shabtis in the Petrie Museum,” 18.35 Stewart, “Index to the Named Shabtis in the Petrie Museum” 18. Aubert and Aubert, Statuettes égyptiennes, 226, acknowl-

edge the existence of the two shabtis (attributing both to the same owner); Schneider, Shabtis 1, 341, mentions only “UC 546,” which he assigns to “Payef-tjau-Neith, high steward (contemp. Amasis),” although this title does not appear on Petrie No. 546/UC 40093.

36 Aubert and Aubert, Statuettes égyptiennes, 226; Schneider, Shabtis 1, 341. For more on this high official, see A. Hussein, “Self-Presentation of the Late Saite Non-Royal Elite: The Texts and Monuments of Neshor Named Psamtikmenkhib and Payeft-jauemawyneith” (PhD diss., Johns Hopkins University, 2009), 116–209.

37 J. Heise, Erinnern und Gedenken: Aspekte der biographischen Inschriften der ägyptischen Spätzeit (Fribourg; Göttingen, 2007), 225–28, 229–33, securely attributes only two biographies to Payeftjauemawyneith: naophorous statue BM EA 83 and naophorous statue Louvre A 93.

Fig. 5. Griffith’s published transcription of the inscription from a shabti found at Nebesheh (drawing after W. Petrie, Nebesheh, pl. 12).

BASSIR AND CREASMAN 167

naophorous statue BM EA 83,38 naophorous statue Mit Rahina 545,39 the lower part of a statue from Buto,40 and naophorous statue Louvre A 93.41 He is also known from a spell inscribed on a libation table in Cairo.42

He held many titles and positions, including wr swnw “chief physician,”43 xrp aH “administrator of the palace,”44 and jmy-rA pr wr “high steward.”45 His parents’ names and offices are known from the monu-ments and reflect what appears on Griffith’s shabti. His father Sasobek held among his titles xrp Hwwt “director of the palaces,” while the name of his mother, a “female musician of Neith, Mistress of Sais,” is known to have been Nanesbastet.46 Thus there is no doubt that Griffith’s shabti in fact belonged to this particular high official.

UC 40093 gives only one useful identifier, the title aA n xA “great one of the xA hall.” This, too, is among Payeftjauemawyneith’s titles, known from three of his monuments.47 It is thus entirely possible that the owner of UC 40093 was the same Payeftjauemawyneith who occupied a number of high offices during the reigns of Apries and Amasis. The facial features of this object are indeed very similar to those that appear on another of his monuments, Louvre A 93 (fig. 6).48

38 For more on this statue, see Heise, Erinnern und Gedenken, 225–28; Hussein, “Self-Presentation of the Late Saite Non-Royal Elite,” 117–24; I. Guermeur, Les cultes d’Amon hors de Thèbes: recherches de géographie religieuse (Turnhout, 2005), 106–8; pls. IV–V; K. Piehl, “Saitica,” ZÄS 31 (1893), 88–91; H. Bassir, “The Self-Presentation of Payeftjauemawyneith on Naophorous Statue BM EA 83,” in E. Frood and A. McDonald, eds., Decorum and Experience: Essays in Ancient Culture for John Baines (Oxford, 2013), 6–13. However, to refer to this statue some scholars have used BM 805[83]: Lichtheim, AEL 3, 33; BM 805; J. Kahl, Siut-Theben: Zur Wertschätzung von Traditionen im Alten Ägypten (Leiden; Boston, 1999), 228–30; or BM EA 83(805): D. Pressl, Beamte und Soldaten: Die Verwaltung in der 26. Dynastie Ägypten (664–525 v.Chr.) (Frankfurt am Main-Berlin-Bern-New York, 1998), 231. Although E. Budge, A Guide to the Egyptian Galleries (Sculpture) (London, 1909), 223, refers to no. 83 at the end of his entry, he uses no. 805 as the main number of his exhibition. All these numbers referring to this statue are confusing.

39 For more on statue Mîtrahîna 545, see Bakry, “Two Saite Monuments of Two Master Physicians,” 325–33, fig. 1; Pressl, Beamte und Soldaten, 232; PM III.2, 847–48; Hussein, “Self-Presentation of the Late Saite Non-Royal Elite,” 124–26.

40 Pressl, Beamte und Soldaten, 233, refers to a lower part of a statue that she believes belongs to Payeftjauemawyneith. According to Pressl, this statue was discovered in the University of Tanta excavations by Fawzy Mekkawy at Buto/Tell Al-Faraîn. No date for this excavation is mentioned. However, she does refer only to Payeftjauemawyneith’s titles on this statue and dates it to the reign of Apries. Attempts to gain access to this fragmentary statue have been unsuccessful, but for more on this statue, see Hussein, “Self-Presentation of the Late Saite Non-Royal Elite,” 126–27.

41 For more on naophorous statue Louvre A 93, see Hussein, “Self-Presentation of the Late Saite Non-Royal Elite,” 127–32; A. Baillet, “La statue A 93 du Louvre,” ZÄS 33 (1895), 127–29; K. Bosse, Die menschliche figur in der rundplastik der ägyptischen spätzeit von der XXII. bis zur XXX. Dynastie (Glückstadt-New York, 1936), Doc. 88; Bothmer, De Meulenaere, and Müller, Egyptian Sculpture of the Late Period 700 B.C. to A.D. 100, 68, 76, 77; J. Breasted, Ancient Records 4, 514–17, §1015–25; H. Brugsch, Thes. 6, 1252–54; H. Goedicke, “Review of Ancient Egyptian Literature: A Book of Readings, volume III, The Late Period by Miriam Lichtheim,” JAOS 102 (1982), 173–74; Heise, Erinnern und Gedenken, 229–33; K. Jansen-Winkeln, “Das futurische Verbaladjektiv im Spätmittelägyp-tischen,” SAK 21 (1994), 107–29; Jelínková-Reymond, “Quelques recherches sur les réformes d’Amasis,” 275–87; A. Leahy, “The Date of Louvre A.93,” GM 70 (1984), 45–58; Lefebvre, “Textes égyptiens du Louvre,” 87–104; Lichtheim, AEL 3, 33–36; E. Otto, Biog. Inschr., 164–66; O. Perdu, “Socle d’une statue de Neshor à Abydos,” RdÉ 43 (1992), 145–62; Piehl, “Säitica,” 118–22; idem, “Un dernier mot sur la statue A 93 du Louvre,” ZÄS 34 (1896), 81–83; idem, Inscr. 2; P. Pierret, Recueil d’inscriptions inédites du Mu-sée égyptien du Louvre, vol. 2 (Hildesheim; New York, 1978 [1878]), 39–41; PM V, 99; Pressl, Beamte und Soldaten, 232; E. Chassinat, Le mystère d’Osiris au mois de Khoiak 1 (Cairo, 1966), 255–60; U. Rössler-Köhler, Individuelle Haltungen zum ägyptischen Königtum der Spätzeit: Private Quellen und ihre Königswertung im Spannungsfeld zwischen Erwartung und Erfahrung (Wiesbaden, 1991), 243–45; S. Shubert, “Realistic Currents in Portrait Sculpture of the Saite and Persian Periods in Egypt,” JSSEA 19 (1993 [1989]), 27–47; D. Klotz, “Two Studies on the Late Period Temples at Abydos,” BIFAO 110 (2010), 128–29; H. Bassir, “On the Historical Implications of Payeftjauemawyneith’s Self-Presentation on Louvre A 93” (forthcoming [2015]).

42 For more on the Cairo libation table, see A. Wiedemann, “Inschriften aus der saitischen Periode,” Rec Trav 8 (1886), 63–69; Piehl, “Saitica,” 84–91; Hussein, “Self-Presentation of the Late Saite Non-Royal Elite,” 132–34.

43 For more on this title, see Hussein, “Self-Presentation of the Late Saite Non-Royal Elite,”191–92.44 For more on this title, see Hussein, “Self-Presentation of the Late Saite Non-Royal Elite,”189–90.45 For more on this title, see Hussein, “Self-Presentation of the Late Saite Non-Royal Elite,”187–88. 46 Hussein, “Self-Presentation of the Late Saite Non-Royal Elite,” 137–41, 186–202.47 It appears on BM EA 83; Louvre A 93; and Mîtrahîna 545; for more on this title, see Hussein, “Self-Presentation of the Late

Saite Non-Royal Elite,” 192–200.48 For more on Payeftjauemawyneith’s visual self-presentation, see Hussein, “Self-Presentation of the Late Saite Non-Royal

Elite,” 192–200, 165–70; Bassir, “The Self-Presentation of Payeftjauemawyneith on Naophorous Statue BM EA 83,” 10.

168 JARCE 50 (2014)

Conclusion

This Payeftjauemawyneith is associated, textually or archaeologically, with sites scattered throughout Upper and Lower Egypt, where he was particularly active under Apries and Amasis: Abydos, Memphis, Buto, Heliopolis; only Griffith’s shabti associates him with Nebesheh in the nineteenth Lower Egyptian nome.49 Evidence from the monuments suggests that during the reign of Amasis he may no longer have held any of the high offices he had occupied under Apries.50 However, at the time of his death he evi-dently retained, at least nominally, the title “high steward” and perhaps also “great one of the xA-hall.”

His tomb has not yet been found. Because his libation table, which features a spell for the “Osiris, the high steward P(ay)eftjau(em)a(wy)neith, true of voice,” was found in a context of reuse in Cairo,51 it has been suggested that his tomb might be someday located among the Late period tombs at Heliopo-lis, Giza, Abusir, or Saqqara.52 Certainly an object such as a libation table is less portable than shabtis

49 For the career and other aspects of the life of this nonroyal elite member, see Hussein, “Self-Presentation of the Late Saite Non-Royal Elite,” 116–209.

50 Hussein, “Self-Presentation of the Late Saite Non-Royal Elite,” 158–59.51 It was found and probably remains in the khanqah of Sultan Baybars II Al-Jashankir at in the Jamaliyah quarter of Fatimid

Cairo (706–709 H./AD 1306–1309/1310), L. Fernandes, The Evolution of a Sufi Institution in Mamluk Egypt: The Khanqah (Berlin, 1988), 25, 121, n. 25. For further brief discussion and sources regarding its modern context, see Hussein, “Self-Presentation of the Late Saite Non-Royal Elite,” 132, n. 839. For the spell on the libation table, see idem, “Self-Presentation of the Late Saite Non-Royal Elite,” 132–33; Piehl, “Saitica,” 86–88; A. Wiedmann, “Inschriften aus der saitschen Periode,” RecTrav 8 (1886), 64–65.

52 Hussein, “Self-Presentation of the Late Saite Non-Royal Elite,” 136, first suggested Abusir. For example, the tomb of Udja-horresnet has been found at this site. For a review of Late period tombs there, see L. Bareš, K. Smoláriková, M. Balík, et al., The Shaft Tomb of Iufaa 1: Archaeology, Abusir XVII (Prague, 2008); L. Bareš, K. Smoláriková, and E. Strouhal, The Shaft Tomb of Udja-horresnet at Abusir (Prague, 1999); L. Bareš, “The Necropolis at Abusir in the First Millennium BC,” in K. Daoud, S. Bedier, and

Fig. 6. The face of naophorous statue Louvre A 93, © 2008 Musée du Louvre, Georges Poncet (used with permission).

BASSIR AND CREASMAN 169

and is thus perhaps less likely to have traveled very far from its original (funerary) context. In February 2006, Vassil Dobrev discovered two shabtis seeming to name a Payeftjauemawyneith at Tabbet al-Guech (South Saqqara),53 a necropolis found to include a number of Late period tombs.54 Saqqara would be more in keeping with not only the context of the libation table but also those sites associated with the other monuments and activities of Payeftjauemawyneith son of Sasobek and Nanesbastet. However, the owner of the shabtis from Tabbet al-Guech appears to be a different individual.55

The discovery of at least one and possibly two of his shabtis at Nebesheh suggests that the tomb of Payeftjauemawyneith son of Sasobek and Nanesbastet could be among the Late period tombs there56 rather than at one of the sites with which he was associated during his active career. It is hoped that it will someday be possible to identify its location and resolve the conundrum offered by the two very dif-ferent contexts of his funerary objects.

University of Arizona

S. Abd El-Fattah, eds., Studies in Honor of Ali Radwan I (Cairo, 2005), 177–82. For more on Late period tombs, see J. Quack, “Das Grab am Tempeldromos: Neue Deutungen zu einem Spätzeitlichen Grabtyp,” in K. Zibelius-Chen and H. Fischer-Elfert, eds., Von reichlich Ägyptischem Verstande: Festschrift für Waltraud Guglielmi zum 65 (Wiesbaden, 2006), 113–32.

53 L. Pantalacci and S. Denoix, “Travaux de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale en 2005–2006,” BIFAO 106 (2006), 354, fig. 7; V. Dobrev, personal communication, 21 November 2013. The two shabtis from Tabbet al-Guech may also be seen in a pho-tograph at http://www.ifao.egnet.net/archeologie/tabbet-al-guech/, accessed 28 October 2013.

54 N. Grimal, E. Adly, and A. Arnaudiès, “Fouilles et travaux en Ègypte et au Soudan, 2005–2007,” Orientalia 77 (2008), 213–16.

55 B. Mathieu (personal communication, 25 November, 2013) points out that there are difficulties in reading the Tabbet al-Guesh shabtis. He indicates that “Payeftjauemawy-Neith is for now the most probable possibility, but not totally certain.” How-ever, as he also indicates, the name of the owner’s mother seems to contain the name of the goddess Hathor (Ht-Hr-m-[…]), and it is possible that “Payeftjauemawy-Neith” is in fact the name of the owner’s father. The legible title, which is priestly, also differs from those known to belong to Payeftjauemawyneith son of Sasobek and Nanesbastet.

56 Petrie, Nebesheh, 20–25.