Outfacing Darwin: Intelligent Design and the case of Mount Rushmore

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

3 -

download

0

Transcript of Outfacing Darwin: Intelligent Design and the case of Mount Rushmore

EMILY BAUMAN

Outfacing Darwin: IntelligentDesign and the case of Mount

Rushmore

It’s day three of The Daily Show’s ‘Evolution Schmevolution’ series.1

Aired when tension preceding the trial about teaching IntelligentDesign in the Dover, Pennsylvania, public schools was at its height, thesatirical news show has decided to make its contribution to the nation’smost recent culture war in a four-day series. Following on-sitereporting from the home of the Scopes Monkey Trial and the BronxZoo, day three introduces a panel of diverse thinkers on the question ofevolutionary origins and higher intelligence.

I could watch this episode again and again. At first the panel seemsto be a comic convergence of incompatible worlds: Edward Larson, anuptight biological historian in a navy-blue suit, William A. Dembski,the thin and sensitive theological-mathematician (or mathematical-theologian), and Ellie Crystal, a New Age metaphysicist in crinklymaroon and a garnet-glow necklace who carefully explains that realityis a grid of twelve squares around a single square. Stewart courtseveryone with a joke (‘You mean your God is Hollywood Squares?!’)and at first it looks as though this is all the panel will be: monologusinterruptus in which everyone has a chance to throw out their mostdearly held vocabulary words and blink rapidly while the host addsthe spoonful of sugar. But Stewart is a subtle interviewer and the entirebanter about ‘core concepts of evolution’ and ‘not talking about the BigG’ and our collective virtual reality as a ‘projection of the universe’ hasbeen swirling toward a single planned moment. In the middle ofDembski’s answer to Stewart’s question about the unintelligentlydesigned vulnerability of the scrotum – intelligence isn’t responsiblefor everything! Dembski responds – Stewart breaks the mood: did theconversion come first, or the theory of design?

It’s the question that most critics of the ID movement have at somepoint been dying to ask. How does someone who’s been scientificallyeducated come up with a theory so complicated and yet so empty? It’sthe human question, not the scientific question, but it has its roots in abasic scientific understanding. Intelligent Design is not a testabletheory; space probe-like, ID searches out the holes in evolutionary

theory and where either inadequate information or a historicalconundrum presents itself, it inserts the Eureka of a supreme intelligentbeing as default cause. Secularists find this explanation at bestunconvincing and at worst scientifically evasive. On what basis, theywonder, do you determine that empirical experimentalism hasexhausted itself, leaving as explanation only the deus ex machina ofsupernatural intervention?

Dembski answers Stewart’s question quietly. The conversion camefirst, he admits. It feels like a Geraldo-esque moment, rich withpersonal confession. ‘I didn’t mean anything,’ Stewart offers, ‘but Ithink it’s interesting that in my experience every scientist I’ve askedhas said that the conversion came first.’ Dembski recovers enough toclaim Newton as a religious scientist ancestor, but the damage has beendone; for all practical purposes he’s been had (in a nice way) and thepanel concludes on a slightly poignant but cheerful note.

As the annual Punxsutawney, PA groundhog ritual can attest, whensmall towns in central Pennsylvania make a judgement they make itincontrovertibly. The verdict in Kitzmiller vs. the Dover Board ofEducation in December of 2005 was a no-contest victory for evolutionagainst Intelligent Design in US schools. Not only had a Bush-appointed judge in a federal court ruled that ID was a non-scientific,trussed-up form of Creationism whose introduction in the publicschool system would violate the separation of church and state, butthe six-week trial produced two notable humiliations. One was therevelation that two of the school board members had perjuredthemselves in their deposition testimonies about the sources of fund-ing for ID textbooks donated to the small town’s high school. Theother was the admission by one of ID’s leading proponents that,under his definition of science, astrology would count as a scientifictheory.

Shortly following an election sweep of the Dover school board byanti-ID candidates, the decision by Judge John E. Jones III seemed toresolve many of the tensions brewing the previous fall, when the boardhad voted to allow a statement to be read in the district’s high schoolscience classes that there are holes in evolutionary theory and that sixtycopies of the ID textbook, Of Pandas and People: The Central Question ofBiological Origins, would be available for those students who wished tolearn more about alternative explanations. At the same time, the stateof Kansas was entertaining challenges to its science curriculumdesigned to weaken the teaching of evolution state-wide. Indeed, thewhole summer and fall of 2005 saw a rise in the public debate about the‘controversy’, inspiring a three-day series in the New York Times, afeature essay in Time magazine, and a spate of commentary ranging

62 Critical Quarterly, vol. 51, no. 1

from liberal-chic New Yorker to neo-con talk show maverick BillO’Reilly.

Since then, the furor has largely calmed. Yet, as a NOVA special onthe Dover trial that was aired in November 2007 concluded, the debateis not over.2 Sparring between both sides continues to go in circles.Scientists continue to be baffled by the public’s continuing to give ID anear, evident most recently in the decision by the state of Texas to fire ascience curriculum designer who had written emails to friends andonline groups advertising a talk by one of ID’s most committed criticswho had also testified for the prosecution in the trial. On theanniversary of Darwin’s death in April 2008, the nation saw therelease of a documentary starring Ben Stein entitled Expelled: NoIntelligence Allowed; the documentary presents ID advocates in highereducation as would-be martyrs, persecuted by evolutionists in a closedintellectual society (it also associates Darwinism with the Holocaust).Though panned by critics, the movie made nearly three million dollarsin its first weekend.3 As dramatised in Flock of Dodos, Randy Olson’s2006 documentary on the ID–evolution debate, the scientific commu-nity is ill-equipped to deal with this populist ‘salesmanship’. TheDover policy may have been guilty of ‘breathtaking inanity’ in JudgeJones’s words, but those who supported it were able to claim they wereacting in the spirit of free inquiry and open-mindedness. This is thesecret of the ID movement’s allure and continuing influence on thecountry’s educational agenda: a strategic appeal to both faith andreason, secured through an apparatus of logical feints that are not somuch successful as they are contagious. It is here that those interestedin a critical analysis of Intelligent Design might concentrate theirattentions. As with most propaganda, ID’s pet examples andsyllogisms promise to bridge fundamental contradictions; but as withmost propaganda, those contradictions also threaten to tear it apart.

Earlier in the Daily Show’s panel discussion, Dembski called on oneof Intelligent Design’s most beloved analogies to make his point.‘You’re driving along the highway in Southwest South Dakota and yousee a rock formation that looks like Teddy Roosevelt, Abe Lincoln, etc.Do you turn to your partner and say, ‘‘Gee, isn’t it amazing what windand erosion can do?’’ Or do you say, ‘‘Was there design there’’?’ In hisminute-long prepared speech, Dembski cites one of ID’s mostestablished and widely circulated arguments from induction. This isprobably his moment of greatest confidence in the whole panel. Yet,though given with total confidence, the analogy of Mount Rushmorecould have told us what Stewart had to get serious to elicit: thatIntelligent Design is vulnerable beneath all the self-assurance. Tell mewhat you brag about and I’ll tell you what your weaknesses are. As we

Outfacing Darwin: Intelligent Design and the case of Mt Rushmore 63

shall see below, the Rushmore analogy may be ID’s flagship trope,recurring in the debate like a nervous tic, but it is also its Achilles heel.As such it offers a powerful opportunity to identify what IntelligentDesign fails to see about itself. Flawed and self-contradictory, theanalogy helps ID redeem its elective promises even as the movement’sown logic threatens to undermine them.

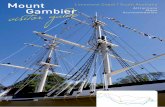

1 Setting the divine clock

Anyone even distractedly familiar with the Intelligent Design debatewill at some point have come across the example of Mount Rushmore.Like the faces on the mountain itself improbably jutting out of theSouth Dakota hills, its image dominates the ID rhetorical horizon. As afigure, it is perhaps more recognisable than the movement’s actualideas or even the names of its own ‘great men’. As far as ID’s publicrelations is concerned, it is appropriate for any occasion. In scholarlypublications, the news media, and popular culture, America’s granitesculpture is the diva example of what ID talks about when it talksabout design.

The first ID theorist to make reference to the strange Americancreation was biochemist Michael Behe, arguably the most importantleader in the movement and certainly the one who has most influencedthe terms of its debate with evolutionists (and also the scientist whoadmitted astrology as a scientific theory in the Dover trial). Beheintroduced the example in his 1996 Intelligent Design classic Darwin’sBlack Box: The Biochemical Challenge to Evolution,4 and calls on itfrequently. In short form, the argument runs thus: our ability to discernthe work of human design in the midst of nature suggests that whenwe examine other aspects of nature that exceed or thwart explanationwe ought to wonder whether those were the result of inhuman design.I quote from Behe’s op-ed piece for the New York Times in 2005:

We can often recognize the effects of design in nature. For example,unintelligent physical forces like plate tectonics and erosion seem quitesufficient to account for the origin of the Rocky Mountains. Yet they arenot enough to explain Mount Rushmore. Of course, we know who isresponsible for Mount Rushmore, but even someone who had neverheard of the monument could recognize it as designed.5

The argument is about that simple, or seems so at any rate. Thecomplexity and recognisability of the faces of the mountain indicate tous, almost instinctively, that a mind rather than natural history musthave been responsible for the precise conjunction of details thatcomprise the proud visages of four great US presidents (whom the

64 Critical Quarterly, vol. 51, no. 1

majority of Mount Rushmore viewers are, incidentally, unable toidentify). This judgement would occur, Behe suggests, even if you wereto arrive there without ever having heard of Mount Rushmore, hadfailed to read the billboards that crowd the expressway leading directlyand exclusively to the site, and had managed to escape the elaboratepatriotic presentation that explains its history and significance –complete with sensory support in the way of fireworks, the Americananthem, and the smell of apple pie.6 Transcending even thesenationalist accessories, the spectacle of art proclaiming itself in thewilderness should unite us all in its gorgeous self-evidence. If this self-evidence arouses us properly, the argument concludes, we may then beled to question the origin of other equally fantastic occurrences innature – like, for instance, ourselves.

‘The Mount Rushmore Test’, a web piece on the Christian Every-Student.com, explains to its target audience how this must be so.

It’s possible that we humans make things so complicated that we fail torecognize the obvious. For example, take a look at the Mount Rushmorephoto displayed here. Now ask yourself, how many years would it takefor these figures to appear on the side of this mountain by chance?Millions of years? Billions of years? Given one hundred trillion years,could these figures eventually form on the side of the mountain?

Is your answer ‘no’? If so, why is it ‘no’? Why couldn’t these facesappear on the side of a mountain, given so much time? Isn’t that how WE

got here? After billions of years of chance, didn’t we eventually,gradually come to be how we are now? Isn’t that the theory that you’vebeen taught to believe as fact?

If at times ID fancies itself a kind of scepticism, the battering ram ofquestions posed by EveryStudent on behalf of its pre-adolescentreaders supports that identification. The goal here is to displaceeducational conditioning with experience-based speculation. By prob-ing their innate assumptions about how they know the mountain cameto be, readers can infer that their instructed assumptions about howthey came to be might be in error (that is, if they want to believe thathumans are as fascinating as the things they create). It is worthrecalling at this point that Intelligent Design acknowledges thatevolutionary processes account for some of the life we see around us;it is just that evolution cannot explain the existence of certain organiclife-forms, life-forms that for ID point to the work of a deliberativeintelligence outside of evolution.

Having already left ‘complicated’ in the dust, the article now turnsto ‘complexity’ – a favourite word of Intelligent Design – to explainwhat distinguishes natural creations from intentional ones:

Outfacing Darwin: Intelligent Design and the case of Mt Rushmore 65

Now consider the men themselves: Washington, Jefferson, [Teddy]Roosevelt, Lincoln. Were the actual men more complex or less complexthan the faces on the side of Mount Rushmore?

This time, it doesn’t leave the answers to chance.

They were MUCH more complex. George Washington led our nation aspresident. Could his face on the side of Mount Rushmore do that?

No way, the 13-year-old answers, before rushing out to talk to herschool board about one of those petitions she heard about in Civicsclass.

What makes the Rushmore analogy powerful is that it is a clearexample of purpose in nature, and one of the most appealing. Earlieranalogies exist of a similar type, but these are cited without the currentzest for detail of the Rushmore example. The oldest thoughtexperiment of this type cited in ID literature belongs to Anglicanclergyman William Paley. In his 1802 Natural Theology Paley argued thatnature’s surprising complexity betrays the hand of a designer, just as ifone were, during the course of a stroll, to discover a pocket watch onthe ground, one would immediately infer by its intricate workings thatit had a maker. The identification is quick, readily assuming that, asBehe put it in interview with National Public Radio, ‘we can recognizethings like Mount Rushmore in life’.7 Like the Rushmore analogy,Paley’s watchmaker conceit reasons from human to natural history. Buta pocket watch lacks the melodrama (and the hubris) of the SouthDakota sculpture, which can make pretences to having pushed theboundaries of what is possible for humans within nature in a way thatthe pocket watch, as a reproducible artefact – however marvellous in itstime – does not. This difference is important. According to ID, if we candetect a human hand where nature has, theoretically, reached its limits,then tracing those limits in cases where humans clearly were notinvolved must testify to the existence of a supernatural agency.

William Dembski is one of the ID theorists most involved in thesearch for scientific means of detecting those limits. Like Michael Behe,Dembski is a senior fellow at the Discovery Institute, the Seattle-basedthink tank that acts as the ID movement’s power base and outreachmachine, and also the executive director of the International Society forComplexity, Information, and Design.8 Where Behe takes on thebiological analysis, Dembski’s contribution has primarily been in thefield of probability science. In particular ID promotion vaunts hisinvention of an evolution/design ‘explanatory filter’, a probabilisticgrid of complexity, contingency, and specification which he claims can

66 Critical Quarterly, vol. 51, no. 1

detect purposeful patterns in nature, forming a ‘bridge betweentheology and science’. In a New York Times paraphrase that once againappeals to the reigning analogy, this filter provides ‘mathematicalcalculations’ that would allow him to distinguish ‘Mount Rushmorefrom Mount St. Helens’.9 Not that anyone needs Dembski’s explana-tory filter to distinguish these two mountains – the maths comesafter the fact, retrieving it for ends already in place. What matters is theway in which seemingly quantitative distinctions between art andnature are used to testify to fundamental differences within natureitself.

It is here that the logic of the Rushmore example runs into hot water.In the analogy, human creations evident in a natural landscape arecompared to natural creations like the eye and the flagellum. Both areseen to be complex in a composite way; that is, each seems to be able toexist only as a totality whose function depends on the holisticorganisation of disparate mechanisms. We cannot imagine part of awatch telling time, nor can we imagine part of an eye seeing, or part ofa flagellum propelling. For this reason, it is argued, the slowevolutionary ‘assembly’ of parts could not have accounted for entitiesthat would only be selected for once they were complete and fullyfunctional. Like Rushmore, conceived as a series of whole faces beforethe sequential labour began, certain organs and organisms must alsohave been conceived in totem prior to their appearance on earth. ‘Suchall-or-none systems, Dr. Behe and other design proponents say, couldnot have arisen through the incremental changes that evolution saysallowed life to progress to the big brains and the sophisticated abilitiesof humans from primitive bacteria.’10 This is the secret of the‘irreducible’ complexity that ID invokes to isolate certain naturalphenomena as unevolvable. Since the piecemeal action of evolutioncan’t account for these complex specialised creations, they must be thework of an external intelligence with a plan.

The scientific response is to argue that, even in a partially evolvedstate, these organs and organisms would have served other functionsthat would give their hosts an evolutionary advantage. But before weeven look to the science, we should be suspicious of the metaphor. It iseasy to grant ID’s initial point that the sculpture intuitively declaresitself a work of art and not a work of nature (though the premise isweakened somewhat by the information that the actress Cherapparently once thought that Mount Rushmore was in fact a naturalformation and not a human creation).11 But the analogy loses steamwhen it conflates physical history and biological history. Rushmoremay be too ‘complex’ for wind, sun, and erosion to make. Is it toocomplex, though, for the forces of variation-driven, environmentally

Outfacing Darwin: Intelligent Design and the case of Mt Rushmore 67

contingent selection building over a long period of time on ascaffolding of changes preserved by the genetic code? The originalsof these faces were after all biologically produced; it is only the fact oftheir likeness that seems to trouble Intelligent Designers. The improb-able accident of one face exactly resembling another pre-given face isthe difficulty according to design, but it is not a difficulty according toscience. The analogy argues that nature isn’t capable of deliveringspecific predetermined outcomes, like the thought experiment aboutthe monkeys and the typewriters eventually creating exactly Hamlet.But this assumes that nature is trying to produce specific predeter-mined outcomes – in other words, that it is trying to design itscreations. It isn’t; nature simply makes (or to put it more exactly, thingsget made). It has no investment in whether it produces GeorgeWashington or George III – nor does it care whether either of these inparticular survives. As far as explanatory reasoning goes, then, theanalogy amounts to a strange tautology in which nature is shown to beincapable of design because it isn’t design.

What the analogy does do is act as a parable of intentionality that IDcan exploit at an ideological level. In circulating the Rushmoreexample, the ID movement presumes that worldly phenomena areanswerable to the logic of predetermination. Instead of discovering inthe world the glory of nature in all its indifferent wit, ID sees it asexisting as it does because someone (or thing) wanted it to. Or moreexactly, it sees that some of it exists as it does because someone (orthing) wanted it to. If, according to Intelligent Design, certain life-formsare the result of evolution and others the result of Providence, then theworld begins to divide among features and organisms that are selectedand those that are elected. It is difficult not to anticipate in thisreasoning the groundwork for a Calvinistic superiority complex.Mount Rushmore, a homage to individual human greatness that paystribute to the exceptionality of a given few, naturally draws out thispossibility. ID proponents may talk about missing transitional fossilsand not being able to reproduce testable conditions for the origin of life,but their metaphors look back to hierarchical distinctions presumed toexist within life itself. Darwin left behind such distinctions when herelated humans to apes, and however social Darwinism may have triedto resuscitate the elective principle it is fundamentally incompatiblewith evolutionary selective mechanisms which predicate ‘superiority’and ‘fitness’ on situational variables and not on any inherent valuewithin a given trait. Survival in evolution is a matter of luck: having theright mutation in the right place at the right time. Survival in IntelligentDesign lays claim to something much more gratifying: the patronageand esteem of a divine Providence.

68 Critical Quarterly, vol. 51, no. 1

The ability to secure a purpose for some natural creations to theexclusion of others is ID’s positive testimonial. This is why someonewould want to believe in it, why he or she would want to go outsidethe bounds of scientific inquiry to answer questions that would sendsomeone else back to the lab. In ID’s eyes each of us humans isintended, our faces as specially made as those on Rushmore’simprobable surface. The idea that there’s a Providence that shapesour ends seems to me more to the point in ID’s arguments even thanthe existence of God (or some Unidentifiable Supreme Intelligence).Certainly ID sympathisers are not shy about the topic; back in 2000 theCenter for Theology and Natural Sciences hosted a conference entitled‘Evolution and Providence’, at which some of the leading as well aslesser known ID proponents and Creationists ‘eager to promote thecreative mutual interaction between contemporary theology and thenatural sciences’ articulated their views that providential designexplains aspects of nature that science cannot.12

That this point of view can be extracted from the Rushmore analogymakes clear the degree to which a definite symbolic and metaphoricagenda directs the science, predetermining the conclusions that itseemingly reaches naturally through scientific analysis. The affirmationof a providential evolutionism has unintended consequences for ID,however, ones that its choice of example exposes in unexpected ways.In the lineage of the Rushmore analogy we discover a history that leadsus to probe the ways in which Intelligent Design’s scientific projectultimately violates and betrays its most cherished theses.

2 Why do people climb mountains?

‘Many great theories are held together by chains of dubious metaphorand analogy,’ Stephen Jay Gould writes in ‘Darwin’s UntimelyBurial’.13 The tradition begins with Darwin himself – something thatIntelligent Design theorists have seized on in their arguments. PhillipE. Johnson, the lawyer-turned born-again Christian considered bysome to have founded the ID movement with his publication of Darwinon Trial in 1993, echoes observations made in evolutionary theory yearsearlier that Darwin ‘had to rely heavily on an argument by analogy’ inreasoning from artificial to natural selection.14 Skipping earliercritiques made by biologists such as Tom Bethell (‘Darwin’s Mistake’,1976), Johnson quotes Darwin defendant Douglas Futuyma to describehow, because of the lack of available examples of natural selection inthe flesh, as it were, Darwin drew on artificial selection data. ‘WhenDarwin wrote The Origin of Species, he could offer no good cases ofnatural selection because no one had looked for them. He drew instead

Outfacing Darwin: Intelligent Design and the case of Mt Rushmore 69

an analogy with the artificial selection that animal and plant breedersuse to improve domesticated varieties of animals and plants’.15 UsingFutuyma’s words against him, Johnson – the author of the would-beSantorum amendment – argues that the project of extrapolatinginferences from the ‘design’ of pigeon breeders to mindless naturallaw is contrived and hence ‘misleading’.

It is a contrivance of which ID is, of course, also guilty. Both sidesseem to be self-conscious about this problem, even cagily apprehensiveabout it. ID websites devote whole pages to defending their right to useanalogies. (See the Intelligent Design and Evolution Awarenesswebsite, www.ideacenter.org, under Frequently Asked Questions: ‘Isit appropriate to justify Intelligent Design theory via analogies?’) Latein Darwin’s Black Box, Michael Behe will spend pages defending his useof analogies, as will one of his main detractors, philosopher RobertPennock, in his hard-hitting response to the ID movement, Tower ofBabel: The Evidence Against the New Creationism.16 Like Behe, Pennock isat pains to defend and explain his right to base a causal argument onlogical inference and on ambitious comparisons between the humanand the natural worlds.

Each side continues to use analogic reasoning, however, despite therisks. Logic’s favourite daughter does after all have scientific connec-tions, ones well placed to advance the cause of those trying to tackle thestubborn topic of biological origin, especially towards revisionist ends.Outside of logic and rhetoric, analogy has a special place in bio-evolutionary terminology, describing functional similarities betweenspecies that arose through a process of ‘convergent evolution’ ratherthan branching off from a common origin. The independent evolution ofthe wings of insects, bats, and birds is a frequently cited example.Though ID and evolutionism part ways over the related topic ofhomology (the diverging evolution of a single ancestral structure),17 theyagree on analogy, both as historical fact and analytic tool. And in somecases, it is not just the procedure but the analogy itself that they share.

Surprisingly, the Mount Rushmore idea does not originate withMichael Behe or with any of the ID theorists. It comes instead from ID’sarch enemy, zoologist and pre-eminent advocate of strict adaptationismRichard Dawkins. In matters of public relations, Dawkins seems tohave declared himself the defender of legitimate rule against the rebelinsurgents, publishing aggressively in response to their arguments andinveighing against both Creationism and religion with uncompromis-ing stamina. And yet he may be the unlikely source of the IDmovement’s most user-friendly analogy.

Something about the invocation of mountains, which in their verybeing seem to call up history from beyond the present, appeals to the

70 Critical Quarterly, vol. 51, no. 1

twin urges of evolutionism and Intelligent Design. In his defence ofnatural selection, Climbing Mount Improbable, Dawkins opens with themetaphorics of that other mountain. ‘Facing Mount Rushmore’, thebook’s first chapter, describes his designation of ‘designoid objects’,objects that look designed but aren’t, a proleptic rebuttal of Darwin’sBlack Box that would come out later that same year. Dawkins contrastsMount Rushmore with the ‘accidental’ shadow of John F. Kennedy castnaturally by a hillside in Hawaii. ‘You couldn’t, on the other hand,persuade a reasonable person that Mount Rushmore, in South Dakota,had just happened to weather into the features of PresidentsWashington, Jefferson, Lincoln and Theodore Roosevelt . . . They areobviously not accidental: they have design written all over them.’18

Dawkins explains this more precisely: ‘The sheer number of details inwhich the Mount Rushmore faces resemble the real things is too greatto have come about by chance.’19 As with the ID theorists, the analogymakes causality a simple probabilistic algorithm dependent onintuitions of complexity (‘sheer number of details’) for its demonstra-tion. Dawkins, of course, has a very different purpose for it in mind.

Climbing Mount Improbable came out in the UK in April of 1996(released in the US in September); Darwin’s Black Box arrived on theshelves that same August. I am not in a position to say whether Behe’suse of Dawkins’s analogy was the result of chance or design. Perhapsthe two evolved independently, analogous structures testifying to adeep functional inevitability and the power of the image itself. Otheranalogies, like Easter Island, are used to make the same point, but theycertainly have never caught on to the degree that the Mount Rushmoreone has. For this reason we might reflect on what might bring Dawkinsand the Intelligent Design theorists together on this one exceptionalpage.

Like Behe and Dembski, Dawkins sees in Mount Rushmore theparamount example of self-evident design, set against an unintelligentnatural backdrop. But it is curious that the analogy lends itself to suchdifferent ends. Dawkins continues to reference it for his own argument(as late as November 2005 in Natural History Magazine), even after it haslong become the part of the predictable wares hauled out by the IDmovement every time it, patiently and enthusiastically, tries to explainitself. Dawkins, however, positions Rushmore as a contrastive ratherthan comparative analogy. For him the mountain is the real counterpartof the ‘illusion of design’ that we perceive in the organic world, aparallel for the wonder we feel when we learn about animalmimicry, the Venus fly-trap, or the human eye, but not for the truths welearn about them, which prove the effectivity of natural selection evenas it commands our total amazement.

Outfacing Darwin: Intelligent Design and the case of Mt Rushmore 71

Rushmore serves Dawkins’s point less awkwardly than it does thatof the ID theorists, since he uses it as a story of perception rather thancreation, aimed to reveal the unreliability of human judgement –always a more secure task than trying for the reverse. Moreimportantly, Dawkins uses the analogy purely for illustrative purposes,leaving the work of showing why complexity is evidence of design inthe physical world while merely the illusion of design in the biologicalto the scientific data and analysis he presents throughout the book. Yetthough Dawkins uses the example in different ways and towards quiteopposite ends to those of the ID proponents, the fact that it originateswith him suggests that there may be something in the very materialismthey reject that ID theorists can’t quite get outside of. In potentiallyco-opting the Rushmore illustration from a system that is hostile totheirs, they open their platform to further scrutiny about the means bywhich they supposedly bridge the mechanics of evolution and theprovidential universe they imagine.

Day No. 6:‘Today I’m really going out there,’ said the Lord God. ‘And I know itwon’t be popular at first, and you’re all gonna be saying, ‘‘Earth to LordGod,’’ but in a few million years it’s going to be timeless. I’m going todesign a man.’And everyone looked upon the man that the Lord God had designed.‘It has your eyes,’ Zeus told the Lord God.‘Does it stack?’ inquired Allah.‘It has a naı̈ve, folk-artsy, I-made-it-myself vibe,’ said Buddha. The Incasun god, however, only scoffed. ‘Been there. Evolution,’ he said. ‘It’scalled a shaved monkey.’‘I like it,’ protested Buddha. ‘But it can’t work a strapless dress.’Everyone agreed on this point, so the Lord God announced, ‘Well, what ifI give it nice round breasts and lose the penis?’‘Yes,’ the gods said immediately.‘Now it’s intelligent,’ said Aphrodite.‘But what if I made it blond?’ giggled the Lord God.‘And what if I made you a booming offscreen voice in a lot of badmovies?’ asked Aphrodite.

– Paul R. Rudnick, ‘Intelligent Design’20

Scientists complain that Intelligent Design destroys the public faith inscience. The public should be more worried about its faith in God. For thedesigner that ID constructs, contrary to popular belief, cannot beunderstood as an independent – and hence providential – intelligence.This is the unintended result of astute strategising. In marketing itself toeducational institutions and government bureaucracies as a non-Creationistalternative to evolution pure and proper, ID compromises the belief systemin whose (unstated) name it advances its ‘Teach the Controversy’ agenda.

72 Critical Quarterly, vol. 51, no. 1

The right-wing revisionist co-optation of scepticism from the left isnot new – witness Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth, in which 1980stobacco companies are quoted as describing their propagandacampaign to discredit federal studies indicating that smoking is infact hazardous to your health in the following way: ‘Doubt is ourproduct.’ Doubt is also ID’s product. It is what it sells, what itadvocates, the basis for its entire philosophy of origin and change, andits historiography of the human. As ID’s opponents are quick to pointout, Intelligent Design is a negative philosophy, basing its argument fora higher intelligence solely on a critique of evolution. The excerpts fromDembski’s speech on The Daily Show and EveryStudent.com show thisgrammatically: ID is built on an interrogative grammar, a network ofrhetorical questions to which all its declarative statements return as ifin fear of their own authority. Doubtless ID theorists see their role, likeJohn the Baptist, as paving the way for the divine affirmations that onlyclerics and prophets can provide, for the positive presence of miraclesand rituals and revealed text that go well beyond the scope of themovement itself. Their self-titled ‘Wedge’ programme, painstakinglydetailed and historicised by Barbara Forrest and Paul R. Gross inCreationism’s Trojan Horse, suggests this strategy.21 They clear thescientific brush, distinguishing themselves from Creationists in orderto make headway in school curricula and state legislation (a projectactive even after the reversal of the Dover, PA, decision), endearingthemselves to teenagers (famous for their innate contrarianism) bycasting themselves as outsider sceptics, while along the way remindingthem of the possibility that life comes from Life, and not theimprobable leftovers of some primeval soup. It is a strategy of complexand multifaceted design.

Yet in clearing the brush ID’s vanguard kills the seed. By defining itsdesigner negatively as the answer to sceptical critique, ID creates afundamental incoherence in its theory of that designer. Witness Behe’sdescription of the supposedly designed system that is life:

The function of a system is determined from the system’s internal logic:the function is not necessarily the same thing as the purpose which thedesigner wished to apply to the system. A person who sees a mousetrapfor the first time might not know that the manufacturer expected it to beused for catching mice. He might use it instead for a defense againstburglars or as a warning system for earthquakes (if the vibrations wouldset off the trap), but he still knows from observing how the parts interactthat it was designed. Similarly, someone might try to use a lawnmower asa fan or as an outboard motor. But the function of the equipment – torotate a blade – is best defined by its internal logic.

(Darwin’s Black Box, 196)

Outfacing Darwin: Intelligent Design and the case of Mt Rushmore 73

Notice here how design is defined as a form of ‘internal logic’, arisingfrom the complexity of the system. Like Rushmore’s obviousdesignedness, the system’s function is claimed to be self-evident.Design is what something can do, at a given moment in time, distinctfrom its creative intention which is, in effect, condensed to themechanism it sets in action. In the realm of religion, this mechanicalreduction would mean that humans, for instance, could justify any actappealing to our physiological makeup (the implications for sexualityand violence, in particular, would be a field day for contemporaryChristian ethics). In the realm of science, Intelligent Design’s relegatingof meaning to function gives ID a savour of sociobiology, the highlycontroversial branch of evolutionary theory associated with RichardDawkins, among others. Like Dawkins’s theories that human beha-viour patterns are skewed toward the survival of the gene and hencebiologically determined, the focus on design reduces the organism toits organic structures and its conception of the organism to how it‘works’, emptying it of ethical content through a functionalistliteralism.

ID may part ways with Creationism in order to protect itself fromlegislative demolition, but there are formidable repercussions.22 Byequating the engineering with the engine, ID not only creates apuzzlingly amoral programme but guts its system of any explanatorycapacity at all. This is made apparent in the quote above in Behe’s veryspecific use of the word purpose. ‘The function is not necessarily thesame thing as the purpose.’ In order to extrapolate the designer fromthe object, purpose is subordinated to design; it arises from itsecondarily as though the goal were to create a functioning systemfor the sake of it functioning, not for what the function allowsit to become or do. Put differently, ID’s insistence on securing theexistence of its designer within biological mechanisms and theirhistories means that it has no external basis on which to articulate whatexactly life has been designed for. As a process, evolution is withoutpurpose, but it can explain why certain traits survive over others: theycontribute to the wellbeing of species and individuals so that they aremore likely to get reproduced. In earlier theologies humans wereunderstood to exist as the mirror and affirmation of God’s image.Intelligent Design claims neither explanation, even as it assumes aninherent meaning and value to life. Neither reproduction nordevotional imitation grounds ID’s sense of the end purpose ofcreation.23 Instead, another tautology surfaces: the system is designedto work so that it can work as a system. At this moment ID’s greatdesigner starts to look like an obsessed gadgeteer with lots of free timeand an independent income.

74 Critical Quarterly, vol. 51, no. 1

Evolution, at least, can account for itself theoretically. The history oflife is a history of reproductive survival, and it is the mechanisms ofsurvival that explain the reasons why populations changed and whythey didn’t. But ID insists that there is a higher intelligence directingearthly history and insists that its purpose is, by the logic ofProvidence, spiritual and transcendent. As a result it cannot identifyreasons with mechanisms, for this would mean falling into a monisticor materialistic worldview. Yet this is exactly what it does do, andwithout apparent self-reflection. The point, Behe announces, is to provedesign only, not the purpose to which it was fitted. It is to prove theexistence of a ‘higher’ intelligence defined automatically, and thus,incontrovertibly. But this quest for certainty, basing supernaturalagency and intelligence in the system (who can argue that it doesnot, in fact, work?), dramatically alters its identity. The designerbecomes the thought expressed in things working – a very Buddhist,but not a very providential, idea.

As a critical methodology restricting its epistemological terrain tothe system it is critiquing, Intelligent Design stays stuck in that system.The designer has been reduced to the designed; manifest destinybecomes manifest functionality. Intellectualising itself in this way, IDavoids Creationism’s taboo dogmas and packages itself as even moredisinterested than the competition, but it also thereby loses Creation-ism’s positive faith. Intelligent Design has indeed diminished itsinventor God to a booming voice in an offscreen microphone. Giventhese roadblocks to both its scientific and its spiritual projects, the turnto Mount Rushmore may well be ID’s most intelligent detour.

3 Prosopagnosia, or because an intelligent agent put themthere

Once you put all the buildings behind you, Rushmore regains itsgrandeur and comes to you on its own terms; like a practiced politician, itdraws you from the crowd and greets you personally.

– John Taliaferro, Great White Fathers

The popularity of Mount Rushmore as ID icon can be directlyattributable to what is missing in Intelligent Design theory itself:a missing primogenitor, the power that generates the power thatgenerates life. Intelligent Design falters in constructing a theory of thesource of creativity, obsessed as it is with functionalist reductions thatfirewall any serious discussion of purpose, without which design ismeaningless.

Outfacing Darwin: Intelligent Design and the case of Mt Rushmore 75

At bottom, ID’s rhetoric is motivated by the double-bind it hascreated for itself. Looking to discover its designer within the holes ofevolutionary theory, ID must reckon with the problem of how togenerate faith out of doubt. It is the same problem Aquinas confrontedyears before: how to create a proof for the existence of God throughlogical inquiry rather than direct revelation. Like ID, Aquinas turned toanalogy as the means by which the human world could be read as asign of an otherwise unknowable and uncertain divine activity.Similarly, Mount Rushmore acts as the revealed text for ID’s statedscepticism, repackaging the accidents of fortune as providentialdestiny. George Washington’s face may not lead a nation as president,but it can inspire lawmakers, parents, and ordinary citizens alike with apositive zeal for what is on its own a critical, negative cosmology.Where the movement begins from and returns to an organisingabsence, America’s ‘shrine to democracy’ seems to embody Presencewrit large. Like the sculpture itself, the ideology Rushmore representsis heavy and big with meanings and ambitions.

Sixty feet tall, 108 feet across, Mt Rushmore is the work of manyunderpaid hands. Nevertheless, the granite sculpture testifies to thepower and personality of its creator. Gutzon Borglum was a man ofcontradictory and passionate impulses. Born to Mormon Danishimmigrants who kept their Mormonism secret for much of Borglum’slife and deprived of his mother for this reason at an early age (she wassent away as his father and stepmother struggled to keep private thefamily’s illegal composition), Borglum became a self-mythologisingfigure, revering Emerson and Carlyle, Manifest Destiny and GreatMen, and all monumentalist history. He was the creative intelligencebehind Rushmore but also originally Stone Mountain, the Georgiamemorial to Confederate heroes, belonged to the Ku Klux Klan and yetsculpted a memorial to Sacco and Vanzetti. This sometime student ofRodin seemed to impose his own definition of personhood well outsideof definitions of party loyalty or what would now be known as ‘type’.Above all he was a populist, helping to draft the Czechoslovakian 1919Declaration of Independence and plan Central Park, convinced of hisidea that the world was not made because it had yet to be built.

If ID advertises Rushmore as its premier example of design, then wecould see Borglum as its exemplary designer. Borglum is everythingthat personifies life, energy, and will. His biography invigorates ID’sunambitious and colourless divinity, who operates only at the limits ofnature and logical argument. Such an intellectualised designer begspersonality and iconic power. Since ID cannot directly call upon God inorder to sell its product (‘I’m not talking about the G-word,’ Dembskisays in his panel discussion on The Daily Show), it therefore calls on his

76 Critical Quarterly, vol. 51, no. 1

proxies: national male icons that testify to the godlike power of humancreation, embodied in sculptor Gutzon Borglum’s impressive conquestof nature and gravity and unrelenting sense of self and purpose.

‘When I approached Rushmore for the first time,’ writes JohnTaliaferro, ‘I anticipated something supernatural, like the loftymountain spires in an Albert Bierstadt painting. But much to mysurprise and satisfaction, I found myself gazing upon something veryhuman – human in form, naturally, but also human in execution. Andthis, I would later come to appreciate, is the glory of Mount Rushmore:It is a true piece of sculpture’.24

Given that Intelligent Design is a field driven in large part byprobability theory and logical reductions, ‘something very human’ maybe just what it lacks. Though the concept of Rushmore fails to prove theexistence of ID’s abstract, rationalised designer, its image bringsintelligence to life in a different way, one that belongs to the socialworld of human history and experience. That Rushmore is a work ofart rather than engineering certainly lends itself to the requirements ofa movement appealing largely to people of faith without delivering thegoods of faith. Yet the use of this image by godless evolutionists as wellas Discovery Institute fellows suggests something more populist innature. Dawkins remarks in passing that ‘our brain has an almostindecent eagerness to see faces’.25 And it might be the rendering offaces as much as anything else accounts for the popularity of thisparticular analogy. Here we have the living complexity that IntelligentDesign hungers for and on which its whole project depends; we have aface for its faceless designer. Marked by personal history andexperience, thoughts and expressions, faces are among the mostcomplicated formations we know. Our brains use some of their mostadvanced technologies to recognise them, and to respond to theintelligence they bring. At the moment when we do recognise a face, itcalls us to read the past in the marks of the present.

I stare at George Washington’s level eyes. ‘Where have the 1770sbrought me?’ he seems to say. This is in some ways the opposite of thequestion ID is asking: where did I come from, what caused me to be as Iam, what explains the origin of life? But it is closer to the question thatunderlies the power behind the ID movement, which is about wherewe go from here. Focusing their revisionary quest on school curriculaand policies, Intelligent Design proponents are clearly as invested infuture changes as past adaptations. Children and teenagers are theircontested territory, not fossils. And as the perplexities of the Rushmoreanalogy show, intelligence resides more powerfully not in the cipher ofan obscure and once-active designer, but in the nature and actions ofthe designed.

Outfacing Darwin: Intelligent Design and the case of Mt Rushmore 77

Over the years, the Lakota people have waged war against thecolonialist appropriation of their land in the Black Hills, thegeographical centre of the nation, arguing the claims of history againstdestiny. Like other sacred places, the Six Grandfathers, now become thefour presidents, reminds those who live there of their past, even asplans are being deliberated to carve a sculpture of Chief Joseph not faraway. Rushmore’s faces seem aware of their own ghosts, conscious thata craggy and inexpressive horizon still looms beneath Borglum’s sharpcuts. But they are also only part of the landscape, just as history is onlypart of the dramas of the present.

‘Look at that.’ Ajax pointed out an incredible sunset, peeking over thesharp edges of the Black Hills. ‘Isn’t it beautiful? The sun is gone, but it’snot gone. Look at that’ – he pointed out a water slide in an amusementpark, one of the many attractions that line the Rushmore road. ‘The kidscome. They play there. Then they forget where they are’.

– Jesse Larner, Mount Rushmore26

Notes

1 ‘Evolution Schmevolution’, Daily Show, Comedy Central, 14 September2005.

2 See Judgment Day: Intelligent Design on Trial, directed by Joseph McMasterand Gary Johnstone, originally aired on PBS on 13 November 2007.

3 The opening salvo of the New York Times review says it all: ‘One of thesleaziest documentaries to arrive in a very long time, ‘‘Expelled: NoIntelligence Allowed’’ is a conspiracy-theory rant masquerading asinvestigative inquiry’ (Jeanette Catsoulis, ‘Resentment over DarwinEvolves into a Documentary’, New York Times, 18 April 2008, late edn, E13).

4 Michael Behe, Darwin’s Black Box: The Biochemical Challenge to Evolution(New York: Free Press, 1996).

5 Michael Behe, ‘Design for Living’, New York Times, 7 February 2005, lateedn, A21.

6 In fact, the hypothesis of someone ever coming across Mt Rushmoredevoid of pre-packaged iconography would make a better argument fordesign than the faces themselves. But this would be a providential-historical, not a technical-inevitable argument, and to my knowledge it hasnever happened.

7 David Kestenbaum, ‘Scientists Hesitant to Debate Intelligent Design’,Morning Edition, National Public Radio, 8 July 2005.

8 Dembski’s biography, as described on the Discovery Institute’s website, isstunning in its range of science-meets-theology credentials: ‘Dr. Dembskihas taught at Northwestern University, the University of Notre Dame, andthe University of Dallas. He has done postdoctoral work in mathematics atMIT, in physics at the University of Chicago, and in computer science at

78 Critical Quarterly, vol. 51, no. 1

Princeton University. Dr. Dembski is a graduate of the University of Illinoisat Chicago, where he earned a B.A. in psychology, an M.S. in statistics, anda Ph.D. in philosophy. He also received a doctorate in mathematics fromthe University of Chicago in 1988 and a master of divinity degree fromPrinceton Theological Seminary in 1996. He has held National ScienceFoundation graduate and postdoctoral fellowships.’ (http://www.discovery.org/scripts/viewDB/index.php?command=view&id=32&isFellow=true).

9 Kenneth Chang, ‘In Explaining Life’s Complexity, Darwinists and Doubt-ers Clash’, New York Times, 22 August 2005, late edn, A11.

10 Ibid.11 See John Taliaferro, Great White Fathers: The Story of the Obsessive Quest to

Create Mount Rushmore (New York: Perseus Books, 2002), 2.12 See CTNS’s website, http://www.counterbalance.net/evoprov/index-

frame.html.13 Stephen Jay Gould, ‘Darwin’s Untimely Burial’, Natural History, 85

(October 1976), 24–30.14 Later, he will reject as ‘spurious’ a key moment of analogic reasoning from

one of Stephen Jay Gould’s most famous essays, ‘Evolution as Fact andTheory’. Johnson takes issue with Gould’s relatively mild claim that astheories of gravity changed from Newton to Einstein, apples neverthelessfell from trees. Johnson counters that ‘We observe directly that apples fallwhen dropped, but we do not observe a common ancestor for modern apesand humans’ (Phillip E. Johnson, Darwin on Trial (Crowborough, Sussex:Monarch Publications, 1994), 67). I leave his analysis to the reader’sjudgement.

15 In Johnson, Darwin on Trial, 17. See Futuyma’s 1983 Science on Trial:The Case for Evolution, which Johnson identifies as ‘one of the leadingcollege textbooks on evolution’ (Darwin on Trial, 158) as a way to justifyand elevate his use of the master’s tools to dismantle the master’shouse.

16 One of the most powerful critiques of the ID movement, especially of theincreasingly marginal branch of Johnson’s ‘young-Earth’ Creationism,Tower of Babel addresses the origin of life question through an analogy withthe origin of language. Executing an elaborate biological-linguisticcomparison, Pennock demonstrates how, just as the Tower of Babelaccount of the origin of language has collapsed under evidence oflinguistic evolution, so does its counterpart in the Genesis story of creationcrumble in the face of science. His defence anticipates criticisms that, inpart because linguistic history does record the action of intelligence,notably memory and judgement, social evolution and species evolution donot always work in the same mysterious ways: Robert T. Pennock, Tower ofBabel: The Evidence Against the New Creationism (Cambridge MA: MIT Press,1999).

17 Homology is Darwin’s rather more dangerous idea, which formed thebasis of his essential argument. The opposite of analogy, homology refers

Outfacing Darwin: Intelligent Design and the case of Mt Rushmore 79

to structures that diverged from a common ancestor but now performdifferent functions (for instance the fins of fish and the legs of tetrapods,which include humans – a transformation recently established to greatacclaim through the discovery of intermediate stage fossils as reported inNature). Predictably, the critique of homology forms one of ID’s recurrenttheses, comprising an entire chapter in the movement’s textbook, theunhappily titled Of Pandas and People (Percival Davis and Dean H. Kenyon,1989/1993) which the Dover school board had hoped to require its biologyclasses to inform students about and make available to them as asupplemental text. Unlike analogous structures, which we perceive visiblyand immediately, evidence for homology – buried in a fragmented andincomplete fossil record – requires interpretation, depending on ourintelligence to be demonstrated. It is here, Intelligent Design theoristsargue, that human wilfulness and error can influence what ought to be adisinterested reading.

18 Richard Dawkins, Climbing Mount Improbable (New York: Norton, 1996), 5.19 Ibid., 6.20 Paul R. Rudnick, ‘Intelligent Design’, New Yorker, 26 September 2005, 88.21 Barbara Forrest and Paul R. Gross, Creationism’s Trojan Horse: The Wedge of

Intelligent Design (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004).22 See, for instance, Forrest and Gross’s discussion of the terminological

changes from the 1989 edition of Of Pandas and People to the 1993 edition,changes which consisted almost solely of replacing the word ‘creation’with ‘Intelligent Design’. When I was teaching in rural Louisiana in 1993,however, such sophisticated considerations were remote and irrelevant.The biology teacher in the high school where I taught took a class poll (aswas his practice) and, as a result of democratic fiat, taught Creationismrather than evolution in his class that year. Coincidentally, this biologyteacher was the adult usually selected to lead the school prayer, a vestigial– and illegal – structure if there ever was one.

23 Earlier examples of proto-Intelligent Design avoid this difficulty bymaintaining Christian dualisms and their intermediary categories. AlfredRussel Wallace, the co-founder of evolutionary theory who later partedways with Darwin to merge science with Spiritualism, argued for examplethat evolution was initiated by and proceeds under the guiding hand of apurposeful God. Remarking that ‘the utilitarian hypothesis . . . seemsinadequate to account for the moral sense’ (The Scientific Aspect of theSupernatural: Indicating the Desirableness of an Experimental Enquiry into theAlleged Power of Clairvoyants and Mediums (London: F. Farrah, 1866), 352),Wallace chose to preserve the traditional Christian idea of God as a simpleunity that encompasses the complexity of creation which he has createdthrough his independent ‘will-force’. In place of Behe’s functionalist‘irreducible complexity’, Wallace suggests an angelic hierarchy mediatingthis divine will and its earthly mechanism, ‘organizing spirits’ who initiatea ‘thought-transference’ between God and evolution (World of Life: AManifestation of Creative Power, Directive Mind, and Ultimate Purpose (New

80 Critical Quarterly, vol. 51, no. 1

York: Moffat, Yard and Co., 1916), 425). An effusion of biographies on andhistories of Wallace, as well as collections of his writings, have come outrecently, indicating a renewed interest in alternatives to establishedevolutionary theory but also, one imagines, alternatives to the alternative.

24 Taliaferro, Great White Fathers, 17.25 Dawkins, Climbing Mount Improbable, 23.26 Jesse Larner, Mount Rushmore: An Icon Reconsidered (New York: Nation

Books, 2002), 29.

Outfacing Darwin: Intelligent Design and the case of Mt Rushmore 81