In situ observation of collective grain-scale mechanics in Mg and Mg–rare earth alloys

Offscreen Dreams and Collective Synthesis in Dovzhenko's Earth

Transcript of Offscreen Dreams and Collective Synthesis in Dovzhenko's Earth

Offscreen Dreams andCollective Synthesisin Dovzhenko’s EarthELIZABETH A. PAPAZIAN

Recent discussions of the Soviet 1920s and 1930s question the notion of a black-and-white world in which the Soviet subject must choose between complicity and resistance, asdefined by the liberal values of the Western critic—who secretly hopes that the object ofhis study will choose the morally preferable path of resistance. A more nuanced view ofthe relationship between individual subjects and Soviet society is needed, one that recog-nizes the instability of such oppositions as public/private, official/unofficial in the contextof the Soviet “transformative, in essence utopian ethos,” and ultimately questions the very“possibility of a stable and coherent Stalinist subject.”1 The call for new historiographicalparadigms poses a particular challenge to the cultural critic discussing works of art: notonly is the focus of the inquiry shifted somewhat, from the “Stalinist subject” (the artist)onto source itself (the work of art), but the special position of both artist and art in Sovietcultural mythology only intensifies the longings of the critic with regard to his/her object.Such scholarly desires had long been an object of critical scrutiny with regard to literarycriticism from the Soviet Union, and the Western critic has become adept at “readingbetween the lines” of artists, writers, scholars, and diarists to find the “real” opinion con-cealed within. Having learned to negotiate the labyrinth of “official” and “unofficial”discourses (even given the fuzziness of the distinction), how can one come to terms withone’s own desires to “exonerate” or even “sanctify” the best Soviet artists (heaving a sighof relief at unambiguous signs of official disapproval such as expulsion from the Writers’

I gratefully acknowledge the help and suggestions of Herbert Eagle, Nikolai Firtich, Vida Johnson, Gretchen Jones,Stephen P. Hill, Susan Larsen, George Liber, Joel Seltzer, Sergiy Trymbach, Raymond John Uzwyshyn, and JosephineWoll, and in particular the detailed comments I received from Bohdan Y. Nebesio and my anonymous reviewer. Re-search for this article was made possible by a grant from the University of Maryland General Research Board. I alsothank my undergraduate research assistants at Vassar College, Margaret Crowley and Nicole McGrath, and the staffof the Library of Congress’s European Reading Room. All stills courtesy of BFI Stills, Posters and Designs.

1See the special issue “Resistance to Authority in Russia and the Soviet Union,” Kritika 1 (Winter 2000), especiallyJochen Hellbeck, “Speaking Out: Languages of Affirmation and Dissent in Stalinist Russia,” 86 (for the first quote),and Anna Krylova, “The Tenacious Liberal Subject in Soviet Studies,” 145 (for the second quote).

The Russian Review 62 (July 2003): 411–28Copyright 2003 The Russian Review

papazian.pmd 2003. 05. 07., 13:31411

412 Elizabeth A. Papazian

Union, at discoveries of dissenting work “for the drawer” which compensates for the ca-pitulating published work)?

Such a nexus of desire—triangulated among author, text, and critic, and mediated bytemporal and spatial distance from the text—certainly informs the viewing of AlexanderDovzhenko’s masterpiece of the silent cinema, Earth (Zemlia, 1930). The film, which waswritten, shot, and edited between April and December 1929, just as collectivization and“dekulakization” of the countryside were being implemented,2 was marked by controversyfrom the moment of its first previews in the spring of 1930, and continues to engagescholars today. Situating Dovzhenko’s oeuvre within the context of a previously “sub-merged” Ukrainian cultural context, Raymond John Uzwyshyn has noted that the director’swork is “emblematic of an archeologic ‘site’ for political struggles occurring in the wider[Soviet] republics but also, ironically, in the West.”3

The present article, while perhaps guilty of the “Unionist” fallacy (or Soviet chauvin-ism) to which Uzwyshyn refers, represents an attempt to reexcavate the plundered archeo-logical site through recourse to that most basic of tools, close reading. First, I will describethe categories and defining oppositions established in the earliest criticism of the film andcarried over into the present, and propose an alternate view of the film’s plot shape. Re-cent analyses by Vance Kepley, Jr., and Bohdan Nebesio emphasize the “difficulty” ofDovzhenko’s silent film narratives and the relative freedom of the viewer in synthesizingmeaning4; I will follow this trend in a close analysis of the treatment of offscreen space inEarth. It is my contention that Dovzhenko uses offscreen space, along with a relatedtechnique of “unreported speech,” to allude to a utopian vision; the presence of the utopianimpulse is also revealed in a striving toward visual and thematic synthesis. The nature ofthis utopia and its relation to the Soviet project, however, is rendered ambiguous and mustbe resolved by the viewer.

Early reception of Earth generally praised its formal mastery (formal'noe masterstvo)but sharply criticized its ideological failures (ideologicheskie provaly).5 In the most vi-cious attack on the film, the “Kremlin poet” Demian Bednyi denied its artistic merits andcalled the film “counter-revolutionary obscenity!” and “a Kulak cinema-film.”6 Accord-ing to its contemporary detractors, Earth foregrounded “biology” to the detriment of

2See Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine, 3d ed. (Seattle, 1998), 553-63.3Raymond John Uzwyshyn, “Between Ukrainian Cinema and Modernism: Alexander Dovzhenko’s Silent Trilogy”

(Ph.D. diss., New York University, 2000), 9. Western left-wing criticism of the 1930s uncritically accepted Sovietfilm, just as right-wing criticism uncritically attacked it. See Vlada Petric, “Soviet Revolutionary Films in America(1926–35)” (Ph.D. diss., New York University, 1973), cited in Uzwyshyn, “Between Ukrainian Cinema and Modern-ism,” 423.

4Vance Kepley, Jr., “Dovzhenko and Montage: Issues of Style and Narration in the Silent Films,” Journal of Ukrai-nian Studies 19 (Summer 1994); Bohdan Y. Nebesio, “The Silent Films of Alexander Dovzhenko: A Historical Poet-ics” (Ph.D. diss., University of Alberta, 1996), esp. chap. 4. See also P. Adams Sitney, Modernist Montage: TheObscurity of Vision in Cinema and Literature (New York, 1990), chap. 2.

5I. M. Iakovlev, in “Diskussiia o ‘Zemle’,” Kino i zhizn' (21 April 1930): 9. Many of the scathing criticisms of thefilm in this volume are tempered by sincere admiration of it as a work of art. Left-leaning Western critics such asHerbert Marshall similarly pointed out the “fundamentally counter-revolutionary philosophy” of Earth, while admit-ting it was “indeed a beautiful film” (from Marshall’s 1930 review of the film in Close-Up (September 1930), cited inMarshall, Masters of the Soviet Cinema: Crippled Creative Biographies (London, 1983), 121.

6Demian Bednyi, “Filosofi,” Izvestiia, 4 April 1930, cited in Marshall, Masters of the Soviet Cinema, 126–28(Marshall’s translation).

papazian.pmd 2003. 05. 07., 13:31412

Offscreen Dreams and Collective Synthesis in Dovzhenko’s Earth 413

“sociology”: instead of emphasizing the triumph of the new society over the old, the filmwas seen as emphasizing the continuity of natural processes.7 Kepley contests this idea,finding that the film’s overarching theme is “naturalization,” an attempt to “naturalize”collectivization in the service of change.8 Thus Kepley inverts the charge that the filmtakes a “biological” position, revealing how Dovzhenko combines “biology” with “sociol-ogy”: “biological” (natural) processes are used to convert a radical social process into anatural (and inevitable) one.9

Clearly, as Kepley asserts, the primary layer of Earth’s meaning is necessarily basedon its ostensible propaganda mission in the interest of collectivization. However, Sovietcritics sensed “ideological failures” in the film: perhaps these might hint at a second layerof meaning, a hidden reactionary (or dissenting) position? Kepley writes that “naturaliza-tion” is a theme traditionally used “to defend the status quo,” whereas in Earth it is used“to make a large-scale change appear spontaneous, practical, and palatable.”10 Could thismean that Dovzhenko’s narrative is reactionary (from the Soviet perspective) in its the-matic structure?11

The opposition of “biology” and “sociology” can be read as a coding of the familiarSoviet antithesis of “old” and “new” (as in Eisenstein’s formulation), as well as of themore general binary pairing of “nature” and “culture.” The old, prerevolutionary, “back-ward” way of life is linked with nature; the new, revolutionary path is associated with“culture”—which in turn is associated with technology and progress. Another implicitopposition, occurring in both Soviet and Western critical reception of the film, arose throughthe (imprecise) use of the term “pantheism”—which we might place in contrast to“utopianism.”12 Ultimately, all these oppositions can be reduced to an opposition in narra-tive shape, between circularity (stasis) and linearity (progress). This leads us to the inevi-table question: is Dovzhenko’s film ultimately “circular,” “biological,” and “pantheistic,”or “progressive,” “sociological,” and “utopian”?

Because Earth was made during the initial stages of the First Five-Year Plan, it re-flects both the relative ideological and artistic pluralism and enthusiastic and radical

7In “Diskussiia o ‘Zemle’” see, for example, the unsigned introduction, “‘Zemlia’ Dovzhenko,” and the commentsby Feliks Kon, 6, R. A. Kedrova, 7–8, P. A. Bliakhin, 8, and I. M. Iakovlev, 9, as well as “Rabochii prosmotr v klubeVTsSPS,” 9. In addition, many commentators believed that the “class enemies” were portrayed incorrectly. Lastly, thefilm was seen as indulging in “unhealthy eroticism” (Kedrova, 8).

8Vance Kepley, Jr., In the Service of the State: The Cinema of Alexander Dovzhenko (Madison, 1986).9Gilberto Perez has written that in Earth “the Old is not so much discarded as assimilated into the New.” See his

“All in the Foreground: A Study of Dovzhenko’s Earth,” Hudson Review (Spring 1975): 83. This contrasts withKepley’s reading, since “naturalization” implies the converse—the New incorporated into the Old.

10Kepley, In the Service of the State, 84.11This is essentially what one Soviet critic implied in 1930, when he wrote that in Dovzhenko’s film, “a formal-

artistic inadequacy is already transformed into an ideological defect” (Bliakhin, “Diskussiia o ‘Zemle,’” 8).12Marshall defines the term “pantheistic” in Masters of the Soviet Cinema, pointing out that this term was used

(pejoratively) in early Soviet reception of the film. (He then agrees with that evaluation, now reading “pantheistic” asa virtue.) Contemporary Western critics of the film also used the term; for example, Alexander Bakshy wrote that,“though the story is ostensibly political in its message ... it is wrapped in a pantheistic sentiment that spreads a veil ofeternity over all incidents of human life, reducing the conflict to a mere episode in the endless cycle of love, birth, anddeath” (Nation [29 October 1930]: 480). If “pantheistic” is taken to mean, as Marshall defines it, that “life and deathare inextricable opposites in unity,” then many other critics have referred to “pantheism” without using the word(Masters of the Soviet Cinema, 132–33).

papazian.pmd 2003. 05. 07., 13:31413

414 Elizabeth A. Papazian

utopianism of the 1920s as well as the nascent, all-encompassing artistic method of So-cialist Realism.13 The tension between the traditional, natural way of life and the progres-sive, technological forces that disrupt it can be read in terms of Katerina Clark’s formula-tion of the cultural shift in the early thirties: from the machine as the “dominant culturalsymbol” of the early years of the First Five-Year Plan to a focus on nature as both a chaoticelement to be overcome and a utopian goal.14 In Earth, the key to transforming nature is“electrification,” a loaded concept with a range of associations that serves as a metaphorfor both “enlightenment” (bringing light and/or consciousness) and the release of “en-ergy.”15 While electrification per se is not an overt topic in the film, it is alluded to first ofall through the somewhat sinister recurring distance shot of telephone poles slicing thestill landscape and sky and connecting village with center (Moscow), and secondly throughthe disrupting force of the machine (the tractor) in the village.16 The tractor arrives alonga road punctuated by telephone poles; at first we see only earth, sky, and thin poles on theright side of the frame intercut with waiting villagers; then a small smudge appears, andfinally, we see the tractor and the men accompanying it. Thus the tractor follows the“electric” or “electrifying” path of the telephone wires, a path that brings “enlightenment”from Moscow.17

Earth presents a vision of the industrialization of the countryside (collectivization) aselectrification: in the sequence after the arrival of the tractor, we see all the villagersworking together, both in harmony with the machine and as a sort of machine themselves;they integrate the tractor into their work and integrate themselves into its work. Themutual relationship is revealed above all, perhaps, in the moment when the tractor stops,its radiator depleted of water: the young men urinate into it, and off it goes. The action isframed by a pastoral vision of nature (distance shots of wheat and sky, close-ups of flowers,trees, and fruit, particularly apples), in an apparent echo of not only the Marxian sequenceof history, from preindustrial simplicity to communism, but also the Christian one, fromParadise to Paradise.18 The narrative that unfolds inside the frame tells the story of re-demption through electrification (progress) as well as through the martyrdom of the pure,visionary hero.

13As Dovzhenko expressed it in his remarks during the discussion of the film at ARRK on 20 March 1930, “I madethe film Earth right at the turning point of two eras.” See Dovzhenko, Sobranie sochinenii, ed. Iu. Barabash et al.(Moscow, 1966), 1:264.

14Katerina Clark, The Soviet Novel: History as Ritual, 3d ed. (Bloomington, 2000), 93–113.15On the metaphor of “electrification” and its various incarnations see ibid., 93–97. The associations range from

Lenin’s slogan (“Communism equals Soviet Power plus the electrification of the entire country”) and the Marxist-Leninist view of electricity as a symbol of progress, knowledge, and “society organized on a rational, scientific basis,”to Stalin’s association of electricity with the industrialization of all aspects of life—economic, political, and social.

16Note also that a telephone call (presumably from some central party headquarters) is intercut with the tractor’sarrival.

17As Clark points out, in 1928, Stalin reinterpreted Lenin’s slogan: “by ‘electrification,’ Stalin said, Lenin meantindustrialization in general, and the time was now ripe for industrializing the entire country, including agriculture,which would be ‘industrialized’ in the sense that the rural sector would be converted from one based on small holdingsto large-scale operation, highly mechanized and subject to central planning and control” (Soviet Novel, 93–94).

18“Even Marx’s account of alienation and the division of labor can be seen as a variant of that megamyth of man’sFall from unity, which began with Adam and Eve’s banishment from the Garden of Eden” (ibid., 108).

papazian.pmd 2003. 05. 07., 13:31414

Offscreen Dreams and Collective Synthesis in Dovzhenko’s Earth 415

The basic plot of the film is quite simple: an old man, Semén, dies peacefully at thebeginning of the film, surrounded by his family. His son, Opanas, owns a small plot ofland; his grandson, Vasyl, is an activist working toward collectivization. Opanas plowshis plot of land with oxen, while Vasyl sets off with his activist friends to pick up thetractor allotted to the collective by the party. The tractor arrives; the people rejoice; theharvest begins; markers delineating individual plots of land are overturned. The propertyboundaries of the Bilokin' family, “kulaks” who have been hoarding their grain, are alsotransgressed.19 After the great day of harvesting, Vasyl leaves his fiancée and heads home,breaking into a traditional Ukrainian dance; in the middle of his joyful dance, he is shotdead by the young kulak Khoma Bilokin'. Vasyl’s family rejects the priest’s attempts tocomfort them, and Opanas asks the young men of the collective farm to organize a specialfuneral “without religion,” in which the young people will sing “new songs about the newlife.” During the funeral, the priest pronounces anathema on the collective farm; Vasyl’smother gives birth to another child; Vasyl’s fiancée tears her clothes off in grief; andKhoma confesses to the murder. The villagers listen raptly to the speech of the youngCommunist leader, unaware of or indifferent to Khoma’s confession.

In terms of the linear organization of the narrative, the film not only tells the story ofthe building of a collective in a single Ukrainian community; it also charts the birth ofconsciousness in Vasyl’s father, who moves from a position of ambivalence about progressto an acceptance of both collectivization and secularization, and more importantly, to aconscious understanding of the vision of the “new life.” His enlightenment comes, super-ficially at least, through the electrification of the collective—that is, through the arrival ofthe tractor. The only time we see Opanas crack a smile during the course of the film isduring the “harvest sequence,” in which the tractor becomes the core of a collective har-vesting machine, and, in fact, apparently spawns not only a whole inventory of agricul-tural machinery, but an entire bread factory. The distortion of time and space of thissequence, in which a single day expands to contain an entire harvest season and an appar-ently small village expands to contain a factory, can be seen as the center of the film withregard to its utopian project: the sequence shows the results of the intense compression oftime. This temporal contraction parallels the “great leap forward” of the Five-Year Plan:while conveying a sense of industrialization in progress, the sequence offers a vision of thefuture, of an industrialized, urbanized countryside—life as it should be.

One cannot help but wonder whether the whole sequence represents a flash forwardor even a dream. Time and space expand, the pace of motion within the frame quickens(in the case of the collective farm “machine”) or slackens (in the case of the contrast ofOpanas mowing alone, with a scythe), the rhythm of the cutting is increased, objects areshown closer and closer, until we are looking at waves of grain moving through parts ofvarious machines so closely and so quickly that the images become abstract. Yet thesequence is not motivated as a dream of any specific character, at least not through

19On the use of the term “kulak” as a political designation, see Uzwyshyn, “Between Ukrainian Cinema and Mod-ernism,” 420–34); Robert Conquest, The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine (NewYork, 1986); and Magocsi, History of Ukraine.

papazian.pmd 2003. 05. 07., 13:31415

416 Elizabeth A. Papazian

conventional means: instead it represents the collective dream, and stands as the key mo-ment of a concrete vision of the Communist future.

The “harvest sequence,” the culmination of the first half of the film,20 causes Vasyl’sfather, Opanas, to stop his futile and slow “plowing with oxen” and to smile with joy at thewonderful things that collectivization can bring, the achievements of the future; however,he does not yet participate in the collective. His true revolutionary transformation frompassivity to action comes only with the death of his son, Vasyl: it is only this murder thatbrings Opanas to the party headquarters to ask for a funeral for Vasyl without priests andreligion, but with “songs of the new life.” In this sense, the single dynamic character ofthe film, Opanas, requires not only “electrification” in the form of the tractor (driven byhis son) but something else as well, something embodied by the death of his son. Thissomething else is alluded to in the film in several places, through references to a realityoutside the represented realm of the film. This is done through the use of offscreen space.

Offscreen space, or the space outside the frame, comes into play with onscreen spacein several ways—in particular, through “entries into and exits from frame,” offscreenglances, partial framing of a character, and camera movement.21 As Noel Burch pointsout, “any film ... employs movements into and out of frame; any film ... suggests an oppo-sition between screen space and off-screen space through the use of such devices as off-screen glances, the shot and the reverse shot, partially out-of-frame actors, and so on. Yet... only very few directors (the greatest ones) have used this implicit dialectic as an explicitmeans of structuring a whole film.”22 (Burch specifically mentions “the Russians, AlexanderDovzhenko in particular,” as being particularly sensitive to the possibilities of offscreenspace.23)

In Earth, characters are frequently framed in close-up or medium close-up, lookingoffscreen, but often without a subsequent eyeline match, that is, a shot revealing what isbeing looked at. Moreover, the lack of establishing shots at the beginning of a scenemeans that what is being looked at often cannot be deduced on the basis of topographyalone.24 Thus the offscreen glances remain unresolved. This even occurs when a particu-lar object is clearly implied by both the surrounding situation and the offscreen gaze, aswith the baby born to Vasyl’s mother during the funeral sequence. In addition, some viewsare shown without a corresponding gaze, rendering not only their position but also theirreality unclear: the harvest sequence, for example, seems to be a dream because of itsintense compression of time and space, but it is an unattributed vision.

20Perez, “All in the Foreground,” 82–83.21Noel Burch, “Nana, or the Two Kinds of Space,” Theory of Film Practice (London, 1979), 17–31. Burch points

out that Soviet directors, particularly Dovzhenko, “severely limited” camera movements, perhaps because they “sensedthe multiple implications present in camera movement”—that is, that “any camera movement obviously converts off-screen space into screen space or vice versa” (p.29, emphasis added). Perez notes that Dovzhenko’s use of cameramovement in Earth is limited to keeping a moving object framed (or onscreen). See his The Material Ghost (Balti-more, 1998), 166–67.

22Burch, “Nana,” 23–24 (emphasis added).23Ibid., 29.24Such omission of establishing shots is a general characteristic of the “Soviet School” (Nebesio, “The Silent Films,”

248).

papazian.pmd 2003. 05. 07., 13:31416

Offscreen Dreams and Collective Synthesis in Dovzhenko’s Earth 417

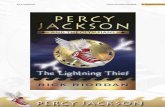

These peculiarities emerge from the opening sequence of the film, which consists ofdistance shots of wheat fields and sky, a shot of a woman and an enormous sunflowerfollowed by a close-up of a sunflower, and shots of fruit trees and fruit at increasingly closecamera distance. As Kepley writes of the single shot of the woman and flower (Fig. 1),“any temptation one might have to reconcile the prior four shots as the visual perspectiveof the woman in shot five would be spoiled by an inconsistent spatial cue: the horizon linechanges in each shot.”25 The viewer’s expectation “that the opening shots are presented soas to establish a story setting” is frustrated: “Nothing will transpire in the space estab-lished in [the first] four shots.”26 The woman’s immobile gaze offscreen, which contrastswith the rhythmic swaying of wheat, sunflower, and fruit, is not resolved by an eyelinematch: the following shot contains an extreme close-up of a sunflower at almost the sameangle as in the previous shot. And although the view of fields recurs in the next sequence,it “seems to be located in an ‘impossible’ space with respect to the eyeline directions ofthose who see it.”27 The opening sequence can therefore be read in part as establishing thevisual motif of the (unresolved) offscreen gaze—and the unattributed view.

The next sequence of the film is made up of shots of family members present atVasyl’s grandfather’s deathbed. There is no establishing shot, only individual medium

FIG. 1 Earth (Zemlia), 1930, dir. Alexander Dovzhenko, VUFKU.

25Kepley, “Dovzhenko and Montage,” 35.26Ibid.27Burch, “Film’s Institutional Mode of Representation and the Soviet Response,” October, 1979, no. 11:89. As

Burch notes, it is unclear what the temporal and spatial relation between this shot and the following scene of thegrandfather’s death is; Burch sees this shot (among others) as relating to both “emblematic” and diegetic space/time.

papazian.pmd 2003. 05. 07., 13:31417

418 Elizabeth A. Papazian

close-ups and close-ups of each individual person, looking offscreen. Each person looksoff in a different direction: without an establishing shot, it is unclear whether they arelooking toward the dying old man, the fields of grain or apple orchards shown in theintroduction, at each other, or somewhere else; moreover, it is impossible to determinewhere each character is standing with respect to the others.28 This offscreen gaze echoesthat of the first shot of a human subject in the film, that is, the woman standing next to thesunflower, which established the visual motif. Gilberto Perez notes that “there is littlefeeling of spatial continuity”: each individual character “has his own intensity”; each sepa-rate element has equal weight, and no one element is subordinated to any other.29

This isolation of individuals, each of whom is looking offscreen, might have anothermeaning, which seems to be connected to the odd request the dying grandfather’s friendPetro asks of the old man: to come back from the dead and tell him about the “next world.”This suggests that the isolated parts are connected precisely by this looking toward anunknown world beyond the reach of the camera.30 Offscreen space suggests the “nextworld” of death.

The use of offscreen space is complemented by a related technique, which I will callunreported speech. This phenomenon, common in films of the silent era, involves acharacter’s lips moving, but without being followed by a dialogue card. Iurii Tsiv'ian hasdiscussed the use of intertitles at some length, focusing on the change, during the 1910s, inthe conventions of their use, in particular the shift from narrative titles (“The life of theZhukovskys flowed by quietly and peacefully”) to dialogue titles. With the growing use ofdialogue titles came the necessity to attribute them, particularly as very often several char-acters appeared onscreen at once: according to Tsiv'ian, lip movement was not the primarymeans of doing this, since it was considered to look ugly and even comical.31 Instead,gesture, context, and mise-en-scène were preferred.32 In addition, by the late 1920s, asNebesio notes, the practice of framing a dialogue title with medium shots of the speakingcharacter had come into use.33 On the other hand, as Tsiv'ian points out, lip-movementsmight be used when it was important to indicate only that a character was speaking, whenwhat was being said was not important; the dialogue card could then be omitted.34

28As the scene unfolds, the viewer gradually infers the disposition of characters based on both the direction of theirglances and a slight turning of the head that sometimes accompanies a cut. The fact that in general the space is notclearly established allows Dovzhenko to switch from an interior to exterior scene (or vice versa) without the viewerimmediately noticing it, as for example in the “mourning of the kulaks” which follows the death of grandfather Semén.

29Perez, “All in the Foreground,” 72–75.30Burch notes that the characters in this scene “are linked only by their eyeline exchanges” (“Film’s Institutional

Mode,” 89). Perez disagrees, positing that the characters “are linked together by their inner arrangement, not by theirrelationship to some object out of frame in a location not specified” (Material Ghost, 175–76). I am arguing that thelink is not to some single object, but rather to an abstract idea of another world that the family group shares, implied bytheir unresolved glances offscreen.

31Iurii Tsiv'ian, Istoricheskaia retseptsiia kino. Kinematograf v Rossii. 1896–1930 (Riga, 1991), 309. Moreover,lip movements would confine the director’s choices in montage; actors were encouraged not to speak at all duringshooting.

32Ibid., 311.33Nebesio, “A Compromise with Literature? Making Sense of Intertitles in the Silent Films of Alexander Dovzhenko,”

Canadian Review of Comparative Literature 23 (September 1996): 688.34Tsiv'ian, Istoricheskaia retseptsiia kino, 312.

papazian.pmd 2003. 05. 07., 13:31418

Offscreen Dreams and Collective Synthesis in Dovzhenko’s Earth 419

Moreover, toward the end of the silent period, the reduction of the number of intertitles,particularly narrative titles, was an international trend.35 In Earth, however, “unreportedspeech” occurs rather differently: a character framed alone, usually in a medium shot,speaks at some length, with his lips moving, about something that should be crucial—butwithout the appearance of a title card. This omission of dialogue titles happens in Earth atthree key moments, each of which concerns the film’s ostensible propaganda goal, itsmessage in favor of collectivization and the Soviet project as a whole.

The first instance of “unreported speech” occurs in the scene of the grandfather’sdeath, when Petro announces that Semén should be awarded a medal for plowing the earthwith oxen for so long. Vasyl laughs at this idea, and says that people are not decorated foroxen: Petro asks Vasyl what it is that people get decorated for, and Vasyl answers emphati-cally, glowing with soft lighting, with flashing eyes and teeth, his lips moving rapidly, butwordlessly—without any intertitles to reveal exactly what he says—in answer to a directquestion about the “new ways.”

Vasyl’s intense, smiling, almost beatific gaze out of frame connects with the offscreenglances of all the other characters in this deathbed scene: a link is established between theCommunist “new life” he is (wordlessly) explaining and the other world offscreen. This isthe first opportunity in the film to make an explicit statement of ideology: old and newhave been juxtaposed (grandfather’s oxen vs. Vasyl’s unspecified new way; the reverseshots of the dying grandfather and several very young children, eating fruit), but the op-portunity for a clear ideological statement is passed up. We are left to supply the wordsourselves.

One explanation for an elision of explicit ideological explanations is, of course, cen-sorship. Therefore, it is important to provide some background on the rather complicatedtextological history of the film. The original screenplay of Earth, which might have pro-vided some clues as to possible censorship, no longer exists.36 The film was reviewedtwice before its official release—first in Kiev, where the intertitles were translated intoRussian before the film was then sent to Moscow and reviewed again.37 Following Bednyi’sattack, cuts were made to the film; these cuts were restored in the reconstructed version ofthe film released in the 1960s.38 I have also referred to the 35mm Gosfilmofond print heldat the archive of the National Center of Alexander Dovzhenko in Kiev.39 At present, the

35Nebesio, “A Compromise?” 684, 688.36There is only a literary adaptation written by Dovzhenko much later (dated 1952), which can hardly be seen as

authoritative (Uzwyshyn, “Between Ukrainian Cinema and Modernism,” 609–12).37It was accepted by VUFKU in February 1930 and pronounced to ideologically reflect “the party’s line and efforts

to reconstruct agriculture” (Nebesio, “The Silent Films,” chap. 1), and by ARRK on 20 March (Uzwyshyn, “BetweenUkrainian Cinema and Modernism,” 412). For Dovzhenko’s opening and closing statements to the discussions on hisfilm see “K bodrosti i zhizni” and “V nogu s vremenem,” in Sobranie sochinenii 1:259–71.

38According to Marco Carynnyk, the cuts were: the filling of the tractor’s radiator, the fiancée’s naked mourning,and Vasyl’s mother giving birth (Alexander Dovzhenko: The Poet as Filmmaker [Cambridge, MA, 1973], liii). AsUzwyshyn explains, there are “at least six different versions of Earth circulating in East and West”; the most widelyavailable version on video in North America, from KINO, is based “on the retitled ‘Khrushchev thaw’ reconstruction”(“Between Ukrainian Cinema and Modernism,” 412, 416). I am quoting the English titles from this version.

39This print is as close as one can get right now to an authoritative version, according to Sergiy Trymbach, a filmhistorian and deputy general manager of the archive.

papazian.pmd 2003. 05. 07., 13:31419

420 Elizabeth A. Papazian

intertitling of the original is unknown: the original Ukrainian titles no longer exist.40

Certainly it will be a crucial task to excavate the history of an artifact whose nature is, infact, far less stable than one might suppose. In any case, I believe that the instances of“unreported speech” work extremely well within the aesthetic system of the film, as I hopewill become more apparent below.

The next instance of unreported speech again complements the use of offscreen spaceto create a sense of a utopian vision which is rendered ambiguous. Not coincidentally, thistakes place in the next scene in which Vasyl appears. The scene begins with a shortsequence which might be called “Vasyl at the window,” and is followed by the arrival ofVasyl’s fellow activists. The “window” sequence begins with two shots:

SHOT 1: medium shot of Vasyl, looking out the bright window on the right sideof the frame (only bright light is visible), bathed in light from the window; he isapparently talking to his father (offscreen); cut (not exactly on his glance, sincehe is not looking at his father);SHOT 2: his interlocutor, his father Opanas, sitting at a table, with his back tothe camera and to Vasyl, though without an establishing shot this is not immedi-ately clear.41

In this sequence, a conversation takes place between Vasyl and his father about the oldways as opposed to the new ones.

VASYL: “Well, Pop, now we’ll put an end to the rich farmers. And get tractors,too.”

OPANAS: “But, [Vasyl], maybe you’re forgetting—what’s his name...”VASYL: “We’ll get tractors and take earth away from them.”OPANAS: “That’s just what I say—maybe you’re forgetting—what’s his name...”OPANAS: “They can get along without you. No need to go.”OPANAS: “Even as it is, the village is laughing.”VASYL: “It’s not the village that’s laughing, Pop, it’s the rich farmers, and the

dopes.”OPANAS: “So you think I’m a dope?”VASYL: “Not a dope, Daddy, but just getting old.”

As Nebesio points out, this sequence is one of very few in the film which “resembles inlength a typical Hollywood film conversation” in that it contains a relatively high number

40Trymbach noted at a recent Symposium on “The Art and Legacy of Alexander Dovzhenko” (Film Society ofLincoln Center, 11 May 2002) that “textological research” needs to be done for all of Dovzhenko’s films. For Earth,the original Ukrainian titles will have to be reconstructed on the basis of Dovzhenko’s 1950s literary screenplay.

41As Burch points out with reference to the grandfather’s deathbed sequence, “the characters are never seen togetherin the same shot; they are linked only by eyeline exchanges.” (“Film’s Institutional Mode,” 89). In general, charactersaddressing each other are rarely framed together. This means that they necessarily look offscreen, toward their inter-locutors.

papazian.pmd 2003. 05. 07., 13:31420

Offscreen Dreams and Collective Synthesis in Dovzhenko’s Earth 421

of dialogue titles: “A traditional conversation is presented in an untraditional fashion.The content of the conversation fades as the viewer struggles to establish the spatial rela-tionship between the two characters.”42 While the precise content of the titles (Opanas’sattempt to convince his son not to go with the party cell to retrieve the tractor) may not beentirely crucial to the narrative, the general topic of “old vs. new,” and the particular ideaof “getting tractors and taking earth away from the rich farmers (kulaks),” is significant,and intersects with the visual system of the sequence. If the dominant of the sequence isthe conversation between Vasyl and his father as told in words and body language (thenoncommunication implied by the characters’ backs), the “overtone” is the relationshipbetween light and darkness, both physical and figurative.43 The shots conflict not onlybecause the interlocutors are facing away from each other, disturbing the continuity, butalso because of the lighting difference. Vasyl’s father is turned away from both Vasyl andfrom the viewer, as well as from the radiant light emitting from the window.

The bright light Vasyl looks toward and which illuminates him is both a metaphor forthe new, bright world of communism that he wants to build and which only he seems tosee, and at the same time a hint of his proximity to death, his martyrdom, and even of anafterlife. The light emitting from the window seems to imply a path to heaven, at the sametime that it illuminates him with an otherworldly light. (He wears exactly the same be-atific expression as he wore in the sequence of his grandfather’s death.) In this sense, thisshort sequence exemplifies the apparent ambivalence of the movie—its simultaneous pro-Bolshevik ideological project and its mythological, even Christian, overtones; the sugges-tion is that the new world that Vasyl envisions will be “heaven” (on earth), at the sametime that it is unknowable, just as Semén’s knowledge about life after death cannot becommunicated to Petro from beyond the grave. The fact that Vasyl’s father is turned awayfrom this reveals not only his initial hostility to the new ways but also the fact that he isclosed to metaphysical understanding—a trend which is reversed by the end of the movie,when he is “converted” to the cause.

When Vasyl’s friend, the head of the Communist cell, arrives along with the othercell members, he and Vasyl begin to harangue Opanas about politics, presumably aboutcollectivization.44 Once again, there are no titles to provide exact quotations: their argu-ment consists of emphatic gestures, earnest expressions, and moving lips, and ultimatelyVasyl and his friend stand in the same shot, arguing simultaneously while Opanas looksaway, chewing a piece of bread. This second silencing of speech, of evidently fiery rheto-ric in favor of Communist goals, would seem an easy way for Dovzhenko to avoid oversim-plifying Bolshevik ideology, or possibly committing to a party line that might soon be

42Nebesio, “A Compromise?” 689.43See Eisenstein, “Methods of Montage,” in Film Form, ed. and trans. Jay Leyda (San Diego, 1949). In The

Cinema of Eisenstein (Cambridge, MA, 1993), David Bordwell defines “overtone” as cutting based on “secondaryexpressive qualities” (p. 132).

44The literary screenplay (dated 1952) makes it clear that Opanas is not a member of the collective farm, whileVasyl is an active member, trying to convince his father to join. On a first or even second viewing of the film, thiswould be difficult to discern, and it is certainly never made explicit (Dovzhenko, “Zemlia,” Sobranie sochinenii,vol. 1).

papazian.pmd 2003. 05. 07., 13:31421

422 Elizabeth A. Papazian

changed or outdated.45 On the other hand, this second omission of ideological discoursemay have a greater significance: the impassioned but silent pro-Bolshevik rhetoric of Vasyland his friend link to that unseen “other world” offscreen, which has been associated bothwith “life after death” and with the Communist utopia, in favor of the latter—however,without explaining exactly what the nature of that utopia is.46

The third instance of unreported speech occurs toward the end of the film, during the“funeral sequence,” and again complements the use of offscreen space. This sequenceincludes several montage pieces cut together—the funeral procession, the priest’s pro-nouncement of anathema, the frenzied mourning of Vasyl’s fiancée, the rage and confes-sion of Khoma, and a woman giving birth. This woman is in fact Vasyl’s mother, Opanas’swife. Many critics have commented on the juxtaposition of life and death in this sequence;however, what is more significant, perhaps, is the fact that the same mother who gavebirth to the positive hero and martyr Vasyl is now giving birth again. The mother looksdown at her baby with an exhausted, again almost beatific, yet motherly smile.47 However,the baby does not appear at all: the mother looks offscreen toward an unseen baby. If Vasylwas the martyr for the collective farm, causing through his death the leap to revolutionaryaction of his own father, what will this new, unseen child accomplish? Like the other sideof the window through which Vasyl sees the future, this child cannot be shown: he, too, isthe future, an offscreen utopian dream whose exact ideological meaning is uncertain.

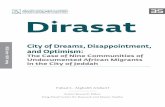

The “birth of the unseen baby” is a single montage piece intercut with several others,the main focus of which is the funeral procession in honor of Vasyl. The procession is ledby Vasyl’s father, who has asked the party cell to organize a special funeral, “withoutpriests or deacons,” in which instead of songs “of death,” “songs of the new life” will besung. The funeral procession consists of close-ups, medium close-ups, and medium shotsof solemn young people, shot from below and looking offscreen (as with the arrival of thetractor), as they walk toward the backing-away camera with their mouths open wide insong, seemingly joyous, but with tears running down their cheeks (Fig. 2). The words ofthe song are, of course, not reported.48

In this case, the birth of a new hero, which comes at the end of the “funeral se-quence,” and the “songs of the new life” would seem almost inevitably to be linked with aChristian vision of life after death; yet Dovzhenko has taken great pains to dissociate thefuneral from religion. Just before the “funeral sequence,” Opanas confronted the village

45As happened to Eisenstein in the making of The General Line, whose title became Old and New when the “gen-eral line of the party” changed.

46It is worth comparing this scene with a similar one in Dovzhenko’s next film, the sound film Ivan (1932), in whichsound provides the exact text for all propagandizing speeches, and offscreen glances are for the most part resolved.Early in the second reel of the film, the young protagonist Ivan has just arrived at the construction site, and looks outa window, his face lit from beyond the window; cut to an apparent point-of-view shot of the site (the Dneprostroihydroelectric dam) surrounded by smoke or mist, in a sort of (apocalyptic) vision of the New Jerusalem.

47Moreover, the mother’s lower body has remained offscreen throughout the film, concealing the possibility of thisnew baby until just before the moment of delivery.

48In the 1952 literary screenplay, Dovzhenko specifies that the young people marching in the procession sing “newKomsomol songs” and the “Internationale,” among other songs. (“Zemlia,” 136) On the other hand, Uzwyshynclaims that “the song not able to be mentioned but clearly on the villagers’ lips is Ukraine’s subsequently proscribednational anthem,” “Ukraine Has Not Yet Died” (“Between Ukrainian Cinema and Modernism,” 566–67).

papazian.pmd 2003. 05. 07., 13:31422

Offscreen Dreams and Collective Synthesis in Dovzhenko’s Earth 423

priest (again silently, but this time without moving his lips), and immediately afterwardwent to the collective farm headquarters to discuss alternative funeral arrange-ments. Moreover, one of the montage pieces making up the “funeral sequence” consists ofthe priest, tiny and alone in a cavernous church, asking God to “smite the impious.”

FIG. 2 Earth (Zemlia), 1930, dir. Alexander Dovzhenko, VUFKU.

Despite this antireligious element, clearly meant as part of the contemporary campaign,the “birth of a new hero” and “songs of the new life” collide in a way that inevitablysuggests religion—whether Christianity’s focus on resurrection and redemption, or theseasonal cycles of pantheism.49 This may have to do with the intercutting of Vasyl’s mothergiving birth with her son’s open coffin, his face brushed by apple tree branches: the deathof the hero, the birth of a new hero, and the solemn faith of the singing masses cannot butconjure the idea of reincarnation. “The key to all the poignancy in Dovzhenko’s films isdeath,” Ivor Montagu wrote.

Death apprehended never as an end, a finish, dust to dust. But death as a sacri-fice, the essential one, a part of the unending process of reviving life. ... Thebasis of all culture. ... No empty cycle, but the hope and certainty, because theinescapable method, in fact the ritual of progress. A poet of death, as part andparcel of eternal life.50

49On the antireligious component of collectivization see, for example, Sheila Fitzpatrick, Stalin’s Peasants: Resis-tance and Survival in the Russian Village after Collectivization (New York, 1994).

50Ivor Montagu, “Dovzhenko: Poet of Life Eternal,” Sight and Sound (Summer 1957): 47.

papazian.pmd 2003. 05. 07., 13:31423

424 Elizabeth A. Papazian

Montagu here conflates the binary opposites of old/new, circular/linear, and pantheistic/utopian in an apparent paradox, which he immediately recognizes: “Pantheism? No. Natureworship? Not at all. Sound Marxist dialectic: the union of opposites.” Herbert Marshallhas a good laugh over this in Masters of the Soviet Cinema, but Montagu has a point, aswill be seen below.51

Utopian ideology is connected to offscreen space one more time. The final moment ofideological rhetoric occurs at the very end of Earth, and is, in fact, not elided. The inspir-ing funeral oration of Vasyl’s friend, the young Communist leader, is reported in severaldialogue cards, one of which states unequivocally that, “With his hot blood, Vasyl wrotethe supreme verdict for the class enemy.” The orator then describes how Vasyl’s “Commu-nist steel horse” overturned thousand-year-old boundaries (mezhi), and how his glory willspread around the world, like “our Communist airplane” over there! At this point theyoung Communist points up in the air; the camera shows a series of long shots of thecrowd, who, looking up, turn their heads to follow the airplane across the sky. The Sovietairplane represents a technology far superior to that of the tractor (which, after all, brokedown along the way), and a symbol of Soviet power far more impressive and far-reachingthan the earlier shots of telephone lines connecting the village to the center and earth tosky: the airplane is beautiful and inspiring, a tangible embodiment of Soviet achievementsand the utopian future.52 However, we are not given a glimpse of this Soviet airplane: theupward glances of the entire collective remain unresolved.

The airplane’s existence and importance, attested by the onlooking crowd, echoes theearlier arrival of the tractor, which is marked by the expectant faces of the villagers, aswell as of the animals it will replace. In the earlier tractor sequence, the waiting villagersare again presented in a series of medium close-up and close-up shots (from below), look-ing offscreen. In this sequence, as opposed to grandfather Semén’s deathbed scene, spatialcontinuity is more or less preserved: basically all the villagers look screen-right, as thetriumphant group of party members accompanying the tractor approaches from screen-right.53 Even when the group of activists comes into view, Dovzhenko postpones showingus the entire tractor for as long as possible: at first he frames the marching party activists,with part of the tractor’s wheel screen-left, from which he pans away, focusing instead onthe marching activists, which the camera follows; only later, after cutting back to motion-less shots of waiting villagers, do we get a tracking shot of Vasyl, in profile, driving thetractor—which is still only partially framed. Here, too, an object of the future is hinted at;people wait for it, scouring the distance to find it first; the camera refrains as long aspossible from revealing it. Moreover, the use of a rare tracking shot to follow the march-ing activists, along with partial framing, draws attention once again to offscreen space: the

51Marshall, Masters of the Soviet Cinema, 133.52Technology in general was an object of suspicion among peasants in the late 1920s. Fitzpatrick mentions the

appearance of both tractors and airplanes in peasant rumors of apocalypse that grew with the increased drive towardcollectivization (Stalin’s Peasants, 46–47).

53Perez argues that “the direction in which they all look ... is not well defined in shots nor clearly oriented spatiallywith respect to any point outside the frame. The tractor is out there somewhere, and we get a few shots of it, butDovzhenko is more engaged with the people who are waiting for it ... they all look expectantly in some direction but weare made to look intently at them” (“All in the Foreground,” 79–80). I would suggest that in fact what they are lookingat is equally important if not more so, and that the postponement of the tractor’s appearance only underlines this.

papazian.pmd 2003. 05. 07., 13:31424

Offscreen Dreams and Collective Synthesis in Dovzhenko’s Earth 425

camera’s movement converts offscreen space into onscreen space; the offscreen dream ofthe tractor is gradually brought onscreen. The movement of the camera contrasts with theinitial stasis of the waiting villagers, which is gradually transformed into movement as thetractor finally comes into view, and they turn to each other in glee, point toward the distanthorizon, and then run to meet it. When the camera finally frames the entire tractor as itmoves across the screen with Vasyl at the wheel (Fig. 3), it seems as though utopiandreams really can come true: the Party fairy godmother, embodied by the telephone polesand telephone call intercut into this sequence, has bestowed upon this collective farm thenecessary magical agent, the “steel horse” with which the collective can make their largerdreams into reality.54 (“We’ll/ Prosper/ With/ Tractors!”) If this object of the future, thissymbol of Soviet progress, can appear (onscreen) as a result of the people’s watching and

FIG. 3 Earth (Zemlia), 1930, dir. Alexander Dovzhenko, VUFKU.

waiting for it, in answer to their dreams, perhaps the offscreen dream seen by Vasyl throughthe window can also be actualized.55

The “naturalization” of the forces of change noted by Kepley intersects with the themeof “electrification,” or, the coming to enlightenment of the collective through technology

54The image shown in Fig. 3 occurs only after the intervening incident of the tractor’s overheating and the replenish-ment of its radiator. In this shot, Vasyl drives the tractor past the fixed camera, followed by the marching activists.

55This impression is reinforced by a repeated shot, intercut with the image of the newly arrived tractor, of membersof the “kulak” Bilokin' family in a darkened interior, looking offscreen (left) through a window, with evident trepida-tion. This shot rhymes with the earlier shot of Vasyl at the window. Just after Petro announces that “it’s a fact,” amember of the Bilokin' family concludes: “They’ve brought it. Well, that’s the end.”

papazian.pmd 2003. 05. 07., 13:31425

426 Elizabeth A. Papazian

in the form of the tractor.56 Vasyl’s vision through the window, his mother’s newbornbaby, and the Soviet airplane all provide unseen images of the future (paradise); the tractorprovides a concrete image of that future. The machine granted by the party electrifies thecollective, putting the static villagers into motion, and promises—as we see in theunattributed vision of the harvest sequence—to transform it, enlighten it, bring it to con-sciousness, urbanize it.57 The tractor becomes the core of the collective, integrating theindividual labor of each character into a larger, dynamic, more efficient system.

The film shows a linear progression, both through the theme of “electrification” andthe plotline of one individual’s coming to consciousness. Opanas, too, is “electrified,” byboth the concretization of his son’s vision and his son’s sacrifice for that vision: after heconfronts the village boys (“Did/ You/ Kill/ My Vasyl?”), we again see the long shot oftelephone poles, and Opanas walks into the camera (which backs down and away fromhim in another rare tracking shot) to confront Khoma. Opanas’s new-found dynamism isthen communicated to the collective, which is similarly shot in the funeral procession witha backing-away camera.

The trajectories of various individual characters (Khoma, Opanas, Vasyl’s fiancée,Vasyl’s mother, the priest) culminate in the separate montage pieces of the funeral se-quence; the parts are brought together, yet they maintain their independence of one an-other, and do not interact: for example, Khoma’s confession is ignored by the attendees ofthe funeral.58 The intercutting of these pieces culminates in the moment in which theentire collective, the whole, looks up together, in the same direction, toward the unseenairplane, and their heads move together to follow its trajectory. This is broken into a seriesof shots, but each is a long shot, containing a large number of people.59 The breaking-upof groups of people looking offscreen has evolved over the course of the film, from series ofclose-ups of individuals looking offscreen (Semén’s death), to series of medium close-upsof twos and threes (the arrival of the tractor), to series of medium close-ups of small groups(the funeral procession), to the distance shots of the entire gathered village.60 This meansthat in the end, Opanas is framed together with his fellow villagers. Vasyl’s vision of thefuture is thus made concrete for the whole group as they turn together to look offscreentoward the utopian airplane; synthesis is achieved.61 As Perez points out, although it is

56Both the “natural process” and the process of enlightenment/education play a role in the coming to consciousnessof Opanas (as revealed particularly in the quick jump cuts of increasingly closer static shots of his face as he confrontsthe priest after his son’s death), and ultimately, of the collective as a whole.

57The aspect of “urbanization” inherent to the industrialization of the countryside is embodied, first of all, in theappearance of a bread factory at the end of this sequence, apparently spawned by the tractor, and staffed by workers inuniform. Thus the “electrification” of the village means not only technology and collectivization, but the raising ofconsciousness: the enlightened villagers will be transformed from peasants into proletarians, who work with machines,whether on farms or in (bread) factories; the farm itself will become a kind of outdoor factory.

58Perez, “All in the Foreground,” 84.59Interestingly, Eisenstein’s critique of Earth focused on the problem of framing: according to Eisenstein, the scene

of Vasyl’s fiancée’s mourning fails because of the “ovens, pots, towels, benches, tablecloths—all those details of every-day life, from which the woman’s body could easily have been freed by the framing of the shot.” See “Dickens,Griffith, and the Film Today” in Film Form, 242.

60There are examples of distance shots of large groups in the scene of the tractor’s arrival; however, Dovzhenkoframes these shots so that members of the crowd gaze in various directions, and often not offscreen.

61According to the French philosopher Gilles Deleuze, Dovzhenko is one of the “truly dialectical” Soviet directors.He follows the “second law” of the dialectic, “the law of the whole, of the set and of the parts. ... If there was ever a

papazian.pmd 2003. 05. 07., 13:31426

Offscreen Dreams and Collective Synthesis in Dovzhenko’s Earth 427

generally considered that “a close-up is a synecdoche,” in fact, every shot in a film is adetail, a section of a larger field extending out of frame.”62 By framing larger and largergroups together, by bringing offscreen space onscreen, Dovzhenko integrates the indi-vidual into the collective—now unified in looking toward the other, new world, which isstill located offscreen.

The wider and wider shots of smaller and smaller human subjects prepare us for thereturn to the narrative frame, which ends, as it began, with wide shots of wheat fields,from which human figures are entirely absent: motion is provided only by the wind andrain. (If Vasyl has become an airplane, the people have become a field.) Here again we areconfronted with the problem of circularity and linearity. The narrative frame of fields,trees, and fruit, which seem to be unaffected by change, clearly implies a perfect circularitythat echoes the loose narrative structure of the film, which begins with grandfather Semén’sdeath and ends with Vasyl’s funeral. This circularity seems to undermine the possibility ofsynthesis, corresponding as it does with the cycle of seasons, with a “pantheistic” concep-tion of eternity, in which life and death are inextricably intertwined, and the part is equalto the whole.63 However, Dovzhenko’s synthesis should not be understood in terms ofEisensteinian conflict. It is rather an integration of individual parts into a collective whole—both in the sense of the heroes’ relationships and in the visual system of the film.64 More-over, the narrative frame of fields and fruit provides yet another referent for the offscreenglances of the film—not only the bright future, but the ever-present earthly paradise, theUkrainian soil (zemlia). In fact, the circularity of the film corresponds to a similar circu-larity in the otherwise linear/progressive shapes of both Christian eschatology and theMarxian view of history, both of which seek an End of Time in the regaining of a lostParadise.65

The very last shot of the film, the vignetted shot of Vasyl’s fiancée with another man,embracing and breathing deeply, suggests still another resolution of a particular offscreenglance, that of Vasyl at the window. It is as though he has seen the future through awindow of the afterlife, and it turns out to be as personal as it is political and historical.We see that life will in fact continue after death, and that this new hero will take over fromwhere Vasyl left off: indeed, it even occurs to the viewer that perhaps this new hero is thebaby brother of Vasyl, miraculously grown up instantly.

director who knew how to make the parts plunge into a whole which gives them a depth and extension disproportion-ate to their proper limits, it was Dovzhenko to a far greater extent than Eisenstein.” See Cinema 1: The Movement-Image, trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Barbara Habberjam (Minneapolis, 1986), 37–39.

62Material Ghost, 168. Perez focuses on how each individual shot in Dovzhenko is “a part that stands on its own,”so that we “forget the space off screen as we apprehend the thing that we have before our eyes.”

63Vasyl, despite being the visionary who dies for the “new life,” is, like the “little man” of Five-Year Plan literaturedescribed by Clark—simply a “part” of a greater “whole,” like every other individual framed by Dovzhenko’s camera(Soviet Novel, 91, 95). This is shown by his “replacement” first by a new baby, then by the airplane, and finally witha new “New Man,” who embraces his fiancée.

64See Deleuze, Cinema I, 37–39; and Perez, Material Ghost, 176.65Marxism charts a “Fall” from the simplicity of preindustrial life in the form of the division of labor and man’s

alienation from his work, to a regaining of Paradise in the form of Communism (Clark, Soviet Novel, 106–13). Theparticular focus on apples in Earth underlines the impression of a Fall: Semén eats a pear before he dies, while a smallchild eats an apple; this precedes the arrival of the “steel horse” which “overturns thousand-year-old boundaries.”

papazian.pmd 2003. 05. 07., 13:31427

428 Elizabeth A. Papazian

By suggesting multiple possible definitions for the unseen offscreen utopian dream,Dovzhenko masks their contradictions. On the one hand, tradition, nature, and the cycleof life exist, persist, and seduce the viewer with their beauty; on the other, the village hasbeen “electrified”—brought to consciousness through technology and sacrifice—and pre-sumably will continue to progress toward that ideal future. The film maintains the sym-metry, rhythm, and (visual) rhyme of a cinematic poem, at the same time that it follows theforward push of prose and the didacticism of utopian fiction.66 By exploiting the emphasison martyrdom characteristic of the Slavic Orthodox kenotic tradition (initiated in the storyof Boris and Gleb) and associating the martyr (Vasyl) with an offscreen paradise, Dovzhenkolinks the Communist Future with a Christian ideal of heaven.67 Whether or not Dovzhenkomeant for the film to be ambiguous (or dissenting), it is this thematic, structural, andgeneric complexity that makes the film a masterpiece.

One does not want Dovzhenko to be advocating collectivization, which in Ukrainebecame a synonym for genocide; one would prefer Earth to resist a plan that was going sowildly awry just as the film was being released in the Soviet Union and internationally.68

Yet, instead of resisting the Soviet utopian ethos, Dovzhenko’s film resists interpretation:by never revealing the exact referent for that offscreen dream of another world, Dovzhenkoobscures the answer to the question of which dream beckons to Vasyl through the radiantwindow. In his essay on “Discourse in the Screenplay of the Feature Film,” Dovzhenkoimplies that in fact one of the distinctive features of the silent cinema was the freedom ofthe viewer to interpret the film: “The viewer in a sense thanked the director and the screen-writer of the film for their faith in his ability for subtle perception and for the fact that thedirector ... in a sense placed him in the situation if not of a coauthor, then in any case, of ahighly-developed, subtle appraiser of his art.”69 By 1953, when these words were written,Dovzhenko had been waiting five years for permission to make a new film; he must havebeen only too aware of the consequences of allowing his reader such interpretive freedom,such space for the interplay among author, text, and critic.

66See Viktor Shklovsky, “Poetry and Prose in Cinema” (1927), in The Film Factory: Russian and Soviet Cinemain Documents 1896–1939, 2d ed., ed. Richard Taylor and Ian Christie (London, 1994), 176–78. On poetic cinema inDovzhenko see Nebesio, “The Silent Films”; idem, “A Compromise?”; and Perez, Material Ghost, chap. 5.

67On “Russian kenoticism” see George P. Fedotov, The Russian Religious Mind (I) (Belmont, MA, 1975), chap. 4.68Uzwyshyn discusses the horrible coincidence of collectivization in Ukraine with the post-production and release

of Earth and provides, in an appendix, a chronology of “Earth Related Dates in the Context of Ukrainian Collectiviza-tion and the Soviet Ukrainian Genocide” (“Between Ukrainian Cinema and Modernism,” 419–28, 607–8).

69Dovzhenko, “Slovo v stsenarii khudozhestvenogo fil'ma,” in his Izbrannoe, ed. A. Ia. Petrovich (Moscow, 1957),588.

papazian.pmd 2003. 05. 07., 13:31428