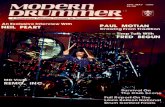

November 1988 - Modern Drummer Magazine

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of November 1988 - Modern Drummer Magazine

Cover Photo by Neil Zlozower

FEATURES

JEFFPORCARO18

Splitting his time between Toto and studio work, JeffPorcaro has experienced the pros and cons of bothworking for himself and for others. He discusses thereasons behind his decreasing use of electronics, andshares a particularly bad experience he once had on astudio session with a well-known artist.

by Robyn Flans

RAYFORDGRIFFIN24

Best known for his seven years with fusion violinistJean-Luc Ponty, Rayford Griffin has also worked withsuch artists as Stanley Clarke, Patrice Rushen, andCameo. He discusses his background, and explains whyhe feels that a lot of music that's labeled "fusion" isn'ttrue fusion.

by William F. Miller

RIKKIROCKETT28

Drumming with the band Poison demands a com-bination of musicianship and visual excitement. RikkiRockett describes his role in the group, and reveals theprocess by which he comes up with his drum parts forthe group's songs.

by Mary Ann Bachemin and Mark Konrad

DRUMS ONCAMPUS32

It wasn't that long ago that drumset was not considereda valid instrument in college music programs. Butthanks to schools such as the University of Miami, theBerklee College of Music, and the University of NorthTexas, students can now pursue music degrees with adrumset major. MD visited these schools for a look atthree different approaches to music education.

by William F. Miller, Rick Van Horn,and Lauren Vogel

Photo by Sharon Sipple

Photo by Jaeger Kotos

COLUMNS VOLUME 12, NUMBER 11

EDUCATIONROCK 'N' JAZZCLINICWhat's In A Note:Part 1

by Rod Morgenstein

40

THE MACHINESHOPBuilding Blocks OfRock

by Clive Brooks42

DRUM SOLOISTSolo Intros: HarveyMason, VinnieColaiuta, and GerryBrown

by Bobby Cleall50

IN THE STUDIOThe Headphone Mix

by Craig Krampf52

THE JOBBINGDRUMMERSubbing: A MusicalApproach

by Mark Hurley74

CLUB SCENEOut Of The Dark

by Rick Van Horn114

106

MASTER CLASSPortraits In Rhythm:Etude #15

by Anthony J. Cirone

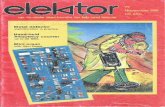

ELECTRONICINSIGHTSStudio SoundsOn A Budget

by Jon Bergeron104

CONCEPTSVisual Learning

by Roy Burns102

DRIVER'S SEATMastering The Fill

by Gil Graham100

ROCKPERSPECTIVESWarming Up: Part 2

by Kenny Aronoff80

EQUIPMENTPRODUCTCLOSE-UPLudwig Super ClassicKit & Black BeautySnare

by Rick Van Horn62

ELECTRONICREVIEWCasio DZ-1 MIDIDrum Translator

by Jim Fiore98

NEW & NOTABLESummer NAMM 1988

by Rick Mattingly116

PROFILES

PORTRAITSMousey Alexander:Profile In Courage

by Russ Lewellen46

NEWS

UPDATE8

DEPARTMENTS

EDITOR'SOVERVIEW

4

READERS'PLATFORM

6

ASK A PRO12

IT'SQUESTIONABLE

14

DRUM MARKET126

MaintainingPerspective

Modern Drummer has never ignored the signifi-cance of electronics and its application to drum-ming, and we've done our best to bring you thelatest information on the subject. I've commentedon the importance of keeping abreast of technol-ogy on more than one occasion in this column.

We've actually been covering the electronicscene since the days of Star and Syndrum in1979. In 1983 we were the first major publica-tion to present a full report on drum machines.And we've continued to cover the new technol-ogy through departments like Electronic Review,The Machine Shop, Electronic Insights, and MIDIComer, each created to help you deal with im-portant aspects of this complex area.

All of this is well and good. However, I believea danger exists when a special-interest musicmagazine gives the impression that technologyshould take precedence over the goal of becom-ing the best player you can be. We've tried tokeep our priorities in perspective over the years,and have deliberately avoided putting too greatan emphasis on technology, over and above mu-sicianship.

Our primary purpose is to help you play the in-strument to the best of your ability. We accom-plish that by presenting the concepts of the lead-ing artists of the day—artists who willingly sharetheir ideas with you. We also help by supplyinginsight on important techniques, and by offeringpractical solutions to problems all drummers en-

counter, whether they be in the concert arena oron the local club bandstand. Publishing informa-tion that will aid you in attaining your goals as aplayer is what we do. Much to our satisfaction,the overwhelming majority of MD readers seemto be in agreement with that editorial premise.

The point is, technology in and of itself won'tnecessarily make you a better player if you haven'tdevoted the time and effort needed to becomeone. There's certainly nothing wrong with explor-ing new areas. But keep in mind that most of theartists who've broken new ground with electron-ics did so only after proving themselves as ex-tremely competent players first. Bill Bruford, DaveWeckl, Terry Bozzio, Chad Wackerman, and PeterErskine are a few who immediately come to mind,and who clearly demonstrate the point. The tech-nology was the icing on the cake for these skilledplayers—the upper floor after the foundation wasfirmly set. Again, it's simply a matter of keepingthings in proper perspective.

Unfortunately, it's pretty easy to have one's pri-orities distorted, in light of today's hi-tech envi-ronment. Over-emphasizing the technologicalaspect tends to make us lose sight of the reasonswe got involved with drums in the first place—which was to play music, and to play it to the bestof our ability. That's what Modern Drummer is allabout. And in the final analysis, isn't that what allthis is really about?

EDITOR/PUBLISHERRonald Spagnardi

ASSOCIATE PUBLISHERIsabel Spagnardi

SENIOR EDITORRick Mattingly

MANAGING EDITORRick Van Horn

ASSOCIATE EDITORSWilliam F. MillerAdam Budofsky

EDITORIAL ASSISTANTCynthia Huang

ART DIRECTORTerry Kennedy

A Member Of:

ADMINISTRATIVE MANAGERTracy Kearney

ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANTJoan C. Stickel

ADVERTISING DIRECTORKevin W. Kearns

DEALER SERVICE MANAGERCrystal W. Van Horn

CUSTOMER SERVICEDonna S. Fiore

MAIL ROOM SUPERVISORLeo Spagnardi

CONSULTANT TO THE PUBLISHERArnold E. Abramson

MODERN DRUMMER ADVISORY BOARDHenry Adler, Kenny Aronoff, Louie Bellson, BillBruford, Roy Burns, Jim Chapin, Alan Dawson, DennisDeLucia, Les DeMerle, Len DiMuzio, Charlie Don-nelly, Peter Erskine, Vic Firth, Danny Gottlieb, SonnyIgoe, Jim Keltner, Mel Lewis, Larrie Londin, PeterMagadini, George Marsh, Joe Morello, Andy New-mark, Neil Peart, Charlie Perry, Dave Samuels, JohnSantos, Ed Shaughnessy, Steve Smith, Ed Thigpen.

CONTRIBUTING WRITERSSusan Alexander, Robyn Flans, Simon Goodwin, Karen ErvinPershing, Jeff Potter, Teri Saccone, Robert Santelli, Bob Saydlow-ski, Jr., Robin Tolleson, Lauren Vogel, T. Bruce Wittet.

MODERN DRUMMER Magazine (ISSN 0194-4533) is pub-lished monthly with an additional issue in July by MODERNDRUMMER Publications, Inc., 870 Pompton Avenue, CedarGrove, NJ 07009. Second-Class Postage paid at Cedar Grove, NJ07009 and at additional mailing offices. Copyright 1988 byModern Drummer Publications, Inc. All rights reserved. Repro-duction without the permission of the publisher is prohibited.

EDITORIAL/ADVERTISING/ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICES: Mod-ern Drummer Publications, 870 Pompton Avenue, Cedar Grove,NJ 07009.

MANUSCRIPTS: Modern Drummer welcomes manuscripts,however, cannot assume responsibility for them. Manuscriptsmust be accompanied by a self-addressed, stamped envelope.

MUSIC DEALERS: Modern Drummer is available for resale atbulk rates. Direct correspondence to Modern Drummer, DealerService, 870 Pompton Ave., Cedar Grove, NJ 07009. Tel: 800-522-DRUM or 201-239-4140.

SUBSCRIPTIONS: $24.95 per year; $44.95, two years. Singlecopies $2.95.

SUBSCRIPTION CORRESPONDENCE: Modern Drummer, POBox 480, Mount Morris, IL 61054-0480. Change of address: Al-low at least six weeks for a change. Please provide both old andnew address. Toll Free Phone: 1-800-435-0715.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Modern Drummer, P.O.Box 480, Mt. Morris, IL 61054.

ISSUE DATE: November 1988

JOEY KRAMERThanks for giving a cover to an excellentdrummer and wonderful person: Joey Kra-mer [August '88 MD]. He is a man whohas proved to us all that you can overcomeanything if you try. Joey has both excellenttechnique and a wonderful visual side, anddisplays both on stage with Aerosmith.

You not only gave readers Joey Kramer,but also a wonderful insight into the worldof drum corps. If it were not for college, Iwould join many a friend on the field. Onceagain, thank you for such a wonderful is-sue. And by the way, the new format looksgreat!

E. VogtLexington KY

I can't tell you how impressed I was byyour handling of the subject of substanceabuse in the Joey Kramer interview. As arecovering alcoholic myself, everything inmy life—especially my playing—changedwhen I took charge of my life. Kudos toSaccone and Kramer for their candor.

Thanks, also, for your thoughtful inclu-sion of my name in your Update depart-ment "News" section. I was thrilled to bementioned in the midst of such distin-guished company. I must say that I neverthought I'd see my name in your maga-zine, by virtue of the fact that I still havemuch to learn about my craft. MD is cer-tainly a good tool at my disposal.

Malcolm TravisBoston MA

LIBERTY AND CARLOSI'd like to extend my appreciation to RickVan Horn and Robyn Flans for two excel-lent interviews in the July issue of ModernDrummer with Liberty DeVitto and CarlosVega. I was fascinated to hear Liberty's storyabout life on the road (especially in the

Soviet Union) with Billy Joel. The chartsection, entitled "Liberty: Off The Record,"was great to have. I only wish every coverdrummer's interview included a similarsection.

Even more, I enjoyed the superb inter-view with Carlos Vega. His classic "rags toriches" story from banging on frying panswith spoons to performing for 50,000people with James Taylor should be an in-spiration to us all. I see Carlos as a veryinspiring, up-and-coming musician whomI'm sure we'll soon hear more and moreabout.

In closing, I must say that the July issueas a whole was probably the best examplein recent issues of the fine journalism thatmakes up your publication. Keep up thegood writing!

Jonathan BurtonDamariscotta ME

DCI CORRECTIONWe would like to thank you for the reviewof Dave Weckl's Contemporary Drummer+ One audio cassette/book package [OnTape, August '88 MD]. We'd like to men-tion that the price of $26.95 listed in thereview was the original price, which alsoappeared in the first few ads. Due to theunanticipated length of the transcriptionbook and charts, the price has beenchanged to $29.95. The early ads wereplaced before the package was complete,due to lead time necessary for magazineadvertising.

In the fall we will be releasing the samematerial in a molded plastic storage case.This case will also be available separatelyto people who already have the material.

Paul SiegelDCI Music Videos, Inc.

New York NY

VIKTOR MIKHALIN AND MOREI am writing to express my heartfelt thanksto MD for doing such a marvelous job ofsupplying the drumming community witha wealth of knowledge month after month,year after year. I read the interview withRussian drummer Viktor Mikhalin [August'88 MD] and was moved to tears by hisgenuine enthusiasm for American musi-cians. Yes, music is a universal language,and drummers are at the core of it.

I also want to thank you for acknowledg-ing drummers, like myself, who are incar-cerated, but who still take their drummingvery seriously. In places like these, ModernDrummer is a godsend. To the other read-ers of MD: Even though we may differ attimes in our opinions, let's remember thatModern Drummer is, and always will be,the only true magazine for us and about us.Let's be mindful not to use it to say thingsthat might be hurtful or offensive to oneanother.

Thomas MaynardWallkill NY

KUDOS TO CORDERRecently, after much thought and carefulconsideration, I decided to purchase adrumset from the Corder Drum Company,located in Huntsville, Alabama. When mydrums arrived, I quickly noticed the fineworkmanship that went into making myset—in addition to their beautiful sound.

Although Corder is a relatively unheard-of drum company compared to the morefamiliar names in the industry, they indeedmake top-quality drums at a reasonableprice. I recommend Corder drums to everyserious drummer who values an American-made product offering the best in sound,quality, workmanship, and service!

Bob OwenAsheville NC

Chris Frantz

When Talking Heads drummerChris Frantz got a call fromVirgin Records some monthsago asking him to take overthe task of producing reggaeartist Ziggy Marley's ConsciousParty album, Frantz didn'tquite know what to do. "Thecall came as a result of anunfortunate incident," Frantzsaid. "My good friend AlexSadkin was supposed toproduce the album, but he hadjust been killed in a caraccident in Jamaica. I didn'tknow how Ziggy felt about theproposition. I mean, he choseAlex to produce the record,not me."

As it turned out, Marley wasvery receptive to the idea, so,in time, Frantz and fellowHead/wife Tina Weymouthwere in the studio with Marleyand the Melody Makers,Ziggy's sibling backup group,working on tracks to this year'smost successful reggae album."It turned out to be a prettygood record," Frantz contin-ued. "I'm glad I was asked toget involved."

Frantz has another projecthe's proud of, too: Naked,Talking Heads' latest LP. Itfeatures some of Frantz's finestmoments as a drummer. "Ireally turned things aroundwhen we went into the studioto record the album," Frantzsaid. "I deliberately went aftera different drum soundbecause I had it up to myeyebrows with the 'big' rockbeat."

Instead of pounding away,

Frantz used brushesrather than sticks for allbut one song, "RubyDear." "I love the tex-ture that you get whenyou use brushes,"Frantz said. "I wanted amore organic drumsound. The only way Iknew how to get it forcertain was to usebrushes."

Frantz incorporatedother stylistic turn-arounds on Naked. "Inthe past, I alwaysseemed to use the hi-hat quite a bit. So thistime I didn't. In fact,most of the drum partson the album aredifferent than what Iwould have played in

the past. They're simple andstraightforward. I was able todo pretty much what I wantedand get away with it."

On top of all this, Frantz andWeymouth have completed abrand new Tom Tom Club LPcalled Boom Boom Chi BoomBoom, which, Frantz said, "isthe kind of drum sound you'llhear on the record." Thealbum features a 50/50 split ofacoustic drums and drummachines, Frantz explained."Because the Tom Tom Clubisn't a band project, I found iteasier to experiment, espe-cially with the drum machine.The album starts off on prettyfamiliar terrain, but then wemove into some pretty weirdstuff." For one song, "TheChallenge Of The LoveWarriors," Frantz sampledhuman breathing and triggeredit so that "the whole thingsounds like a big orgy. There'slots of rhythmic huffing andpuffing going on."

According to Frantz, the TomTom club used to be "some-thing to do on the side." Butsince David Byrne has noplans to promote Naked bytaking Talking Heads on tour,"the Tom Tom Club willprobably become a moreimportant project to me,"Frantz said. "I can't very wellmake a Talking Heads albumand then sit around for thenext year or so," he continued."There's got to be a bit more tomy career, don't you think?"

Indeed.—Robert Santelli

Gina Schock

On House of Schock's firstrecord, Gina Schock split thedrum duties with drummer Ste-ven Fisher. "Initially I wasgoing to play drums on all thesongs, but then I decided thatSteven should participatebecause he's going to beplaying most of these songswhen we play live," Cina says."I found him through mypartner Vance [DeGeneres].Vance played with him in NewOrleans years ago, so hebrought him out here when wewere looking for a drummerbecause he knew I'd be veryparticular in my choice.

"I wanted someone whocould play the songs the way Ilike my songs played. I thinkthe most important thing is thata drummer have good meter.That's first and foremost withme. And he has to be open tomaking any necessary changesthat have to be done to makethe songs work. In otherwords, somebody who won'tcome in and give me a lot ofshit about what I ask him toplay—somebody who isn'tgoing to have a real big egoabout it, who wants to learn.That's what it's all about. Theonly way you learn is by tryingdifferent things."

For the record, she would sitdown with bassist DeGeneresand guitarist Chrissy Shefts towork up the arrangements. "Iwould get all my drum beatstogether. Then we'd bring thearrangements in and showthem to Steven, and he would

play the drum bits I hadwritten. He might add afew things here and there,but we would always talkabout any additions."

Of the 13 songs theyrecorded, Gina ended upon four of the ten thatmade the record: "Just ADream," "Love In Re-turn," "This Time," and"The World Goes'Round." Live, she is onlyplaying drums on onesong, but she playstimbales on three or foursongs and guitar on aboutfive of them.

"It was difficult comingout front because I alwaysgo through the motions ofplaying drums. I'mplaying air drums half thetime," she laughs. "I'll

always play on the albums, butwhen we play live, I can't sitbehind the kit all night andsing. It wouldn't be veryexciting, even though it wouldbe the most comfortable andeasiest thing in the world forme to do. I play drums on thelast song we do in our encore.It's a song by the Beatles called'Everybody's Got Something ToHide Except For Me And MyMonkey.' When we do abigger tour and we're headlin-ing, I'll definitely play on a lotmore songs, but in thesituation we're in now, we'reeither playing clubs or openingthe show. There isn't a lot oftime, and we don't have a bigstage setup because we'reusually set up in front ofsomeone else. When weheadline a tour, though, I'll dothe Phil Collins routine andhave my drums set up rightnext to Steven's. I'll play onmore songs because I'll havethe time and space to do itright."

Was it difficult starting overat the bottom after being in thevery successful Go-Go's? "Youcan sit around and think,'Man, I was playing 20,000-seaters and now I'm having toplay clubs,' but you forgetabout that when you getinvolved with what you'redoing. I was talking to Belinda[Carlisle] the other day, andwhen her first record cameout, she did a club tour. Soyou've got to start over to letpeople know you're serious

According to Marky Ra-mone—who recently returnedto The Ramones after a four-year hiatus—playing with thisnear-classic, quintessentialNew York rock band is nowbetter than ever. Says Marky:"It's even better this timearound because we're allgetting along more, and myown head's a lot clearer."

Marky left the band in '83because "I had a drinkingproblem," he admits. "I tookthe right course of direction tocorrect it, and now it's beenfour years since I last partied.

"Being totally straight is somuch better when it comes toplaying drums: Your pacing issteadier, your playing isn'tsloppy, and of course your tim-ing is better, too. We play foran hour and 20 minutes anight, and with the pace thatwe keep during our shows, wehave to conserve our energiesfor the length of the set.

"A Ramones drummer has toconstantly play 16th notes onthe hi-hat and always has to beready for the 'one-two-three-

Marky Ramome

about what you're doing—thatyou're not going to sit aroundand wait for something tohappen, that you're going togo out and make it happen.Sure, I'd love to be playing20,000-seaters instead ofclubs, but if I have to start outin clubs, that's what I'll do,because I believe in my musicand I love doing it."

—Robyn Flans

four' counts that the bassplayer screams out. You haveto be right there; there's nohesitating, no talking betweensongs. That's because thewhole idea behind theRamones is playing; there's nota lot of conversing with thecrowd. There's the occasional2/4, but it's basically 4/4constantly, and the songs arequick—two-and-a-half minutesongs."

For the record, Marky joinedthe Ramones ten years ago af-

ter being a memberof Richard Hell'sVoidoids. Althoughhe isn't the originalRamones drummer,he has been partici-pating in the bandlonger than anyother drummer.When he tookleave in '83, hewas replaced byRichie (Ramone),who left in '87. Hewas temporarilyreplaced by formerEurhythmies andBlondie drummerClem Burke, whoplayed two gigswith the band priorto Marky's return.

Presently, the Ramones arecelebrating their 14th anniver-sary on tour, and they've re-leased a double-LP of theirbest-loved tunes entitled Ra-monesmania, which has beenreceived quite favorably by oldand new fans.

"The onslaught of energywith this band keeps me likingwhat I do," adds Marky. I canplay drum fills all over theplace if I want to, but that's nota part of the Ramone's music.It's the constant pumping ofenergy—what we get from theaudience and what we giveback—that keeps this sointeresting for me. Being backfor the last year has been likecoming home."

—Teri Saccone

David AllenWhen Paul Riddle left the

Marshall Tucker band four anda half years ago and theinterim drummer, JamesStroud, left a year later, DavidAllen took over the drumchair. The album that was just

released on PolyGram hasbeen in the can since Stroud'sreign, so he is on all the cutsexcept the title track, "StillHolding On," which Davidrecorded. Needless to say,David looks forward to thetime when he can cut an entireLP with the group, but for now,he is content playing with theband in concert.

"Marshall Tucker is kind of acrossover band, so we canplay country nightclubs as wellas rock 'n' roll clubs," Allenexplains. "We go over withboth types of crowds. Actuallywe're labeled pretty muchsouthern rock/country rock,and our crowds range from 15to 50 years old.

"The band is really jazz androck influenced. There are alot of swing-type songs we do.Most of the time I have to playon top of the beat, just to addsome energy to the show. Thesongs are played hard andthey're energetic. A lot of itleans towards a rhythm &blues style of drumming.

"It looks like there are a lotof southern bands out touringnow. Lynyrd Skynyrd is backout, Atlanta Rhythm Section isout, the Outlaws just signed adeal, and we're finding a lot ofpromoters in different areas aremore interested in booking usnow than they were a fewyears ago, so the music seemsto be more appreciated. Ourbiggest market is up north.We've never really drawn thatwell down south."

The band has been so busythat David has had to abandonhis teaching. "Last summer Iwas still teaching part time. Itgot to where I just had toomany irons in the fire, and itreally wasn't fair to mystudents. So finally I had togive up the teaching anddevote all my time to theband. I really enjoyed it,though. I learned so muchfrom teaching six hours a day,four or five days a week. Thelittlest kid would come in anddo something so elementary,but maybe it was something Ihad forgotten about. If theband ever slows downenough, I'll get back into it. Ireally miss it."

—Robyn Flans

Armand Grimaldi on the roadwith Al Jarreau...Eddie Bayers on a RoyOrbison star-studded LP thatwill include duets with SteveWinwood, Tom Petty, BobDylan, and George Harrison.Eddie is also on recent releasesby George Strait, Roger Miller,Conway Twitty, John Jarvis,Charly McLain, the MccarterSisters, Wayne Massey, theJudds, Gene Watson, BarbaraMandrell, Karen Staley, andRonnie Milsap, and he's onRandy Travis' Christmas LP...Russ Kunkel touring with SteveWinwood...Butch Miles is on a Japanesetour with the Great AmericanSwing Orchestra...Dino Danelli on the road withthe Rascals...Jonathan Moffett producedand wrote a song that ChicoDeBarge recorded for thesoundtrack of Coming ToAmerica. The song is called"All Dressed Up (Ready To HitThe Town)." He can also beheard on Julian Lennon's newalbum...Kenny Aronoff on HollyKnight's new record, as well asreleases by John Eddy andGregg Alexander. He has alsobeen giving clinics while onthe road with John CougarMellencamp...Vic Mastrianni on the roadwith Reba McEntire...James L. Burton has beenworking with Canadianrecording artist MichelleWright...John Ferraro has been doingsome dates with Albert Lee...Danny Seraphine on tour withChicago in support of a newrelease...Kevin Winnard on the roadwith Times Two...Clint de Ganon on DionneWarwick's all-Cole Porter al-bum...Lou Molino touring with KimMitchell...Mark Feldman on recent re-cording by guitarist Joe Tay-lor...John Riley has been giggingwith Mike Stern, MikeMetheny, Bob Mintzer, LeniStern, and Eliane Elias.

News...

ED SHAUGHNESSY

Q. I'd like to say that you're the most musi-cal big band drummer I've ever listened to.Could you explain in detail the sizes andtypes of cymbals and drumheads you usedon the second Tonight Show album?

R.D.New Orleans LA

A. Thank you for your very kind compli-ments. I really appreciate your commentthat you find my playing "musical." I'vefound that with big band drumming, whatyou leave out is just as essential as what

you put in. You have to edit yourself a bitmore in big band playing; you can't chat-ter away as much as you could in a combo.

To start with the heads, all the toms andbass drum batter heads were Ludwig Sil-ver Dots. All the tom bottom heads wereheavy, clear Rockers; the bass drum frontheads were coated. The snare drum batterwas a coated Rocker with a dot, and thesnare side head was an extra-thin. All thedrums were wide open except for the bassdrums, which had felt strips for just theslightest amount of muffling.

The cymbals were all A Zildjians, andincluded a 2V Rock ride, two 18" me-dium-thin crashes (right and left sides), a16" thin crash on the left bass drum, a 22"pang played upside-down, and 15" NewBeat hi-hats. Just to round out the picture,I'd like to tell you that the drums wereLudwig Classic models, and that the snarewas a 5" Black Beauty. I'm crazy aboutthat drum because it's the only metal drumI know of that has a "woody" quality—notas nasal as most metal drums—but still re-tains the added projection of a metal snare.

NICKO MCBRAIN

Q. I've been listening to your drummingfor many years, from your days with PatTravers, through Trust, and now with IronMaiden. I like your style very much. Myquestions are: First, have you ever usedclick tracks in the past, and do you usethem now with Maiden? Second, your rightfoot is extremely fast on the single bassdrum that you use. Was there a certain wayyou worked on that?

Tom BittnerRush NY

A. I have used click tracksin the past, but not withany of the major bandsthat I've worked for. I'veused them only on somevarious sessions that I'vehad to play. The mainones that spring to mindwere with a chap calledPaul Ives. I had to putsome drumming tracksdown to some pre-recorded bass and guitarlines that he did in Paris.He brought the tapes toEngland and I had to putthe drums on top. I'venever used a click withIron Maiden. We actuallytend to allow the time tomove a bit; it's not thatdead strict in terms oftempo. There are parts—

say, for instance, a solo—where the timewill go off a little forward of the beat, thencome back into the groove for the verses. Iprefer to work that way.

I didn't really do anything specifically todevelop my bass drum foot; it was mainlyjust lots of playing over the years with theambition of driving the right foot as muchas was humanly possible. As far as tech-nique goes, for speed I find it's a questionof being quite comfortably balanced with

the ball of the foot on the pedal. It's muchmore a question of that than brute force. Isit pretty low; I'm about six feet tall, andwhen I sit down, my legs are virtually hori-zontal, parallel to the floor.

I think the demanding side of IronMaiden—the sort of songs that Steve Har-ris writes and the bass lines he puts to-gether—tend to dictate what kind of drumpatterns should be played. Because of theway a song is structured, that's the way itcomes about that I have to play what I do.If I were to put a straight classic rock pat-tern over it, it would be boring. So I try toconcentrate on playing with the bass pat-tern, or with some of the super-speed gui-tar riffs.

I should point out that the pedal oneuses has a lot to do with speed. I use astandard Ludwig Speed King. It's a result ofhow you just get used to using somethingfor a long time. I have worked with Sonorpedals, and they're very good. They're very"fiddly," with so many different arrange-ments you can have for spring tension,beater angle, pedal height, and so on. ButI've been a Speed King user for the past15 or more years. I find that I prefer thesimpler, lighter weight pedal. Of course, itmust be maintained: It needs to be oiledand greased quite regularly, and when I'mon the road I'll tighten the springs up aquarter of a turn every month or so. Thatkeeps it pretty sweet.

Q. About three years ago I purchased two Paiste cymbals: a 20"Power Ride and a 16" crash. While setting up a few days ago to dosome studio work, I noticed a crack in the crash cymbal, abouthalf an inch up from the edge. I find this very unusual, since theZildjian 15" crash I have (which was used when I purchased it) hasnot even dented in over six years of playing. This fact, coupledwith the fact that I've had no problem with the ride cymbal, hasleft me with a question: whether or not the crack problem is aresult of weather conditions, playing technique, or something elseI'm responsible for. If it is, why hasn't the same cracking occurredwith my Zildjian crash, which I treat the same as I do the Paiste?To further express my dilemma, my Camber hi-hats, which areover six years old, have held up quite well under the same condi-tions of play and weather. I'd appreciate your comments.

K.T.Roeland Park KS

A. There is no way to predict a crack in any cymbal, and very littleway to determine indisputably why a crack has occurred. There isalso no way to explain why a given cymbal cracks when a similarone doesn't, even though the two are used under the same condi-tions. Whether a cymbal is new or old is rarely an issue; manydrummers keep and use cymbals for decades, while others use upcymbals almost as fast as they do heads or sticks. The brand ofcymbal is also generally not a major factor; equal numbers ofnotable drummers swear by both Zildjian and Paiste cymbalswhile citing "breakage problems" with whichever line they don'tuse.

Individual instruments respond differently to identical situations.Obviously, a crash cymbal receives harder, more intense attacksthan does a ride, so it's not surprising that your Paiste crash shouldhave cracked while your ride didn't. Weather conditions shouldnot affect cymbals, since their metal alloys have already beentempered by many hundreds of degrees of heat, and would not

likely become brittle or more "prone" to cracking unless they weresubjected to sub-arctic cold.

As to whether your playing technique contributed to the crack-ing of the cymbal, that is always a possibility, but probably not alikely one if it took you three years to crack one cymbal. Mostdrummers whose technique is so abusive that they crack theircymbals do so quite regularly, and in short order. In your case, itseems to be a case of simply accepting the fact that cymbalscannot be guaranteed to last indefinitely, and must, in the finalanalysis, be recognized as replaceable items.

Q. It seems that all drum hardware is fairly easy to come by. Myquestion is: Do any drum manufacturers sell unfinished shells for ado-it-yourself drummer to design a personal drumset at an accept-able price?

M.F.Washington PA

A. Of course, what constitutes an "acceptable price" is up to you.Most of the major drum manufacturers do not sell raw shells, but anumber of custom drumshell operations do. According to the1988 edition of the Modern Drummer Equipment Annual, rawwooden drumshells are available from the fames Drum Company,229 Hamilton Street, Saugus, Massachusetts 01906; Modern DrumShop, 167 W. 46th Street, New York, New York 10036; and fromThunderstick, Rt. 2, Box 186, Blue Earth, Minnesota 56013. Inaddition, raw fiberglass shells are available from A.F. Blaemire,5208 Monte Bonito Drive, Los Angeles, California 90041, whilebrass snare drum shells are shown in the catalog of Con Bops ofCalifornia, 2302 E. 38th Street, Los Angeles, California 90058.

Q. I am having problems obtaining the speed I want from my basspedal. I recently bought a DW 5000 Turbo, but I can't seem toplay it as fast as I want to. Basically, what I want is a pedal that isvery easily pushed forward to strike the head, but will spring backextremely fast for the next stroke. Can you give me any adjustmentadvice? Also, what about tuning my bass drum?

D.S.Eastman CA

A. Since you state that you only recently purchased your newpedal, any advice given here must be prefaced with the fact thatany type or brand of pedal must be "gotten used to" in order tofunction to its optimum level. But since you describe a particularaction that you are looking for in a pedal, we must mention thatthe DW 5000 Turbo, like any chain-drive pedal based on a circu-lar sprocket, is not designed to give that particular action. Thecircular sprocket is designed to give a smooth, even action onboth the downstroke and the return. The chain pulls straight down,the sprocket rotates in a circular motion, and thus the leverage isthe same at any point on the rotation of the axle. Due to this fact,adjustments for speed are difficult, since tightening the spring for aquick return will make the downstroke that much tighter as well.

The type of action you describe is more likely to be found froma pedal employing an eccentric cam. This is a popular design,represented today by pedals including Drum Workshop's originalDW 5000 strap-drive model, the Gretsch Floating Action, andmany other lightweight models. The linkage on these pedals isdesigned so that the leverage is strongest on the downstroke,making it easy to depress the pedal. The more the pedal is de-pressed, the smaller the radius of the cam becomes, increasing thepower of the beater impact. At the same time, the tension placedon the spring also increases proportionately. When the pedal isreleased, the small radius of the cam allows the spring to returnthe pedal to its original position very quickly.

It is possible to gain a bit of pedal speed by increasing thetension of the bass drum batter head (for a bit of "bounce"). Butdoing so may adversely affect the desired pitch and tonality of thedrum. Generally speaking, it is better to rely exclusively on thepedal for its own action, and tune the drum for sound purposesalone.

I'm driving in my car, thinking about whatI'm going to write about Jeff Porcaro. Thevolume of the radio is nearly off while my

mind is preoccupied, but suddenly I'mprompted to turn the music up. What I've

heard, almost subliminally, is a groove thatfeels so good. I laugh when I realize it's Boz

Scaggs' "Lowdown," and the subject of mypreoccupation is playing drums. I know that I

heard that drum track from an almostinaudible radio because I couldn't not hear it.

The song ends, and I change the station. Thenext song that blares from my speakers is

"Pamela, "from the newest Toto album, TheSeventh One. It's that feel again, and it

becomes obvious that that's what I want toconvey about Jeff Porcaro.

Hours later, I'm sitting in a restaurant. In themidst of a conversation with a friend,

something I can barely hear in thebackground catches my attention. It's "GeorgiePorgie"from Toto's first album, and I wonder

why I haven't noticed any other music that'sbeen played in the restaurant all night. Maybe

it has to do with the fact that no one plays agroove like Jeff. If you've ever seen him play

live, you know it's because he commits hisbody and soul to

by Robyn Flans

He'll laugh when he reads this, and I wish Icould convey his contagious laugh with words.He's been playing professionally since he was17, when he left high school to tour with Sonny& Cher, then graduating to one of the moremusically hip gigs around—Steely Dan. Thenhe became one of the most employed sessionplayers, working for the full spectrum of artists.He'll laugh at the accolades because he simplydoesn't—or won't—acknowledge his specialgift-

In my 1983 interview with Jeff, he made oneof the most ludicrous statements anyone hasever uttered: "My time sucks." Yeah, right. Butleff would rather compliment someone he digsthan talk about why people dig him. His mod-esty doesn't allow him to wear attention well,and he insists that his playing is just a stolencombination of influences. What he overlooksis that he has synthesized those influences intoa style that is all his own. He may have ab-sorbed his hems' playing, but what has beenborn is an amalgamation that is combined withhis own vital, vibrant, emotional personality—the animated way he expresses himself ver-bally, the sensitivity he possesses as a humanbeing, the lack of pretense, and his omnipres-ent vulnerability. All of that is infused in hisperformance as a musician and creates thatsound that makes me feel a drum track he'splayed before I can identify the song.RF: According to Toto's bio, the new albumwas done differently than the past albums inthat it was done live. Is that true?JP: Somewhat true. The first thing different wasthat we had coproducers that we worked wellwith. Toto has always produced their own rec-ords, but then we're worried about the techni-cal end, the control room, the engineering, themaking of work tapes, and on and on to themastering of the record. That takes up a lot oftime. Plus, when you're producing yourself, youlisten to the track as a band. Maybe the track is

burnin', and it feels good, but maybe I'm listening to it andthinking, "I know I could have done a little bit better on thatbridge." But I look around and everyone else is quite satisfied, andit is satisfactory, so I'm not going to cause waves by saying, "Letme do another one." I know through experience everyone is goingto say, "Man, it sounds great," and we move on, because we'retoo kind to each other.

On this album, we had Billy Payne and George Massenburg,who we'd all worked with before and respect highly. So if we cutthat same track, Billy or George might say, "Ah Jeff, try to do thatthing you did earlier on the bridge," and we'll go out and doanother one. The reason we would do another one is because wedid this album as artists. We weren't worried about all the techni-cal things.RF: Does it work the other way, too, where you tend to scrutinizetoo much, and the producer might say, "I think it's cool the way itis"?JP: That has happened, too, and that's also what they were therefor. They were there to push the potential to what it should be.We still tried to arrange, dictate the sounds somewhat, and get thefeel we wanted.

But back to live recording, when we did this album, we tried todo as much rhythm section—bass, guitar, keyboards, and drums—in the studio, with live vocal, as possible. This is the first albumwe've done where we've heard a vocal going on while we cut. Ona couple of songs—for instance, "A Thousand Years" and "TheseChains"—I actually listened to the demo cassettes through head-phones while I recorded the drum tracks. It was like playing alongto a record, which I did when I was learning how to play. I did thaton those particular tunes because the demos were great, the twoguys were singing, so it was definitely the right tempo, and theproduction of the demos was such that I heard all the parts. So Iplayed along. The only other track that's not live is "You Got Me."That track was a demo that David wrote for Whitney Houston. Weheard the song and said, "We should do this in Toto." The songfelt great; it was all electronics, drum machine, and stuff, and wedecided to add real drums, percussion, real horns, guitar, etc.RF: The tune "Farenheit" was pretty machine-oriented.JP: There were two tunes on that album that were Synclavierdrums, and the rest was real drums. "Farenheit" was half Syn-clavier, and the choruses were real drums.RF: How electronic are you these days?JP: Less and less and less and less and less.

Pho

to b

y Ja

eger

Kot

os

RF:Why?JP: I'm not particularly keen about them—how they are as instru-ments to play or their sounds. A lot of people are very excited andthink their sounds are cool, but it's all very Mattel Toy to me. I stilllike acoustic drums in a big room, and I feel I can match anysample by playing drums in a proper room with proper recording,proper outboard gear, gates, AMS's, and all sorts of digital things.You can process real drums on the spot and they'll sound just asgood as any of the electronic crap around.RF: Don't you use Dynacord electronic drums?JP: Yeah, I use Dynacords for a couple of things. I don't triggerDynacord from my real drums much. Live, instead of setting up abunch of timbales and gongs, I'll use the Dynacord gong and itsgated timbales.RF: Like on what?JP: "Africa," the "Dune Theme," "Mushanga," and a couple ofthings. On this particular tour I won't be using it. Luis Conte willbe using my Dynacord stuff and performing those bits of informa-tion for us. My brother Steve just produced a couple of tracks forFernando Saunders, the bass player. We did it at David Paich'sstudio, where I played my whole Dynacord set. I've done it some-times for people, but it doubly goes to show me that nothing is asversatile as a real drumset and a human being.RF: When we did our last interview, machinery was runningrampant...JP: Was I into them then?RF: You were more into the fantasy of what they could be, be-cause it was just starting.JP: And I kept looking at them, saying, "You're light years awayfrom where you should be."RF: But we were talking about being able to phone in a part inperfect time. In our article "Drum Machines, Friend or Foe," yousaid, and I quote, "I see a future of walking into a studio with abriefcase full of my own sounds—all different kinds of sounds.They will be electronically perfect. I can put them in a Linnmachine, or whatever is available in the future, and play like Ialways play."JP: It still hasn't happened. Samples have happened, but what Isaw potentially back then was something that you could play as aplayer, and be able to have your own sounds. That will happen inthe future. But it has to be something with all the beauty ofplaying—meaning it's a physical thing, a dynamic thing. Whenmy mind and my body say, "Man, slam it," that has to come off. Ifthey can duplicate what happens with a real acoustic drum, yeah.Nobody's got real dynamics yet. I've heard at the most five incre-ments, and everybody's joking themselves if they think there'smore than that. Electronic stuff is cool in its place, but for mepersonally, it's still like the old days. When I first got Syndrums, Iused them on four records: a Boz Scaggs record [Down Two, ThenLeft], a Diana Ross record, a Leo Sayer record [Thunder In MyHeart], and Carly Simon's "Nobody Does It Better," which was thefirst record out with Syndrums on it. I did those four records in aone-month period. Right after that I saw a Ford commercial withSyndrums, and I threw up my hands and said, "Okay, that's it." Assoon as you hear something on a TV commercial, it's Mattel. It's atoy.RF: In the studio, do you see a swing back to acoustic drums?JP: Oh yes, I definitely do. First of all, a lot of people thought we'dsave time by programming drums—that they are efficient.RF: That isn't true?JP: I don't think that's true. I've gotten a lot of calls in the past twoyears where people wanted me to replace drum machines. Thenthey went back to just using clicks. Then they would say, "Let's geta rhythm section." Studio owners have been tearing down thewalls of their 200-square-foot rooms for synthesizers to build1,500-square-foot rooms for live drums again. At least aroundhere I've been seeing that a lot. It's not cost efficient, either. Theythought, "I don't have to pay a lousy drummer no more; I canprogram stuff." But it takes people hours and hours to do that,when a capable drummer can record as many songs in a day anda half as it would take a week to program. And it'll feel better andwon't sound like every other record on the radio.

RF: Are you as negative about electronics as you're coming off tobe?JP: They're just not my cup of tea. I react to sounds from electron-ics as I do to fireworks at Disneyland. I go, "Wow, that was great,"but fireworks at Disneyland are not anything like seeing a meteorexplode—hearing a real snare drum and the beauty of the drum. If

it's a tune where you don't want any dynamics out of the drum-mer, yes, electronics are cool. You can get some pretty far-outelectronic sounds, but for me and the music I do, and for mycareer, gigs come up 10% of the time where I have the opportu-nity to use those things.RF: What does your set look like these days?JP: A standard set. I guess Pearl is calling my set the jazz-styledrums. When I went to a photo session, it was with a set of drumsthat weren't mine. When I got there, I said, "The toms seem deep;these aren't my sizes." They said, "These are the standard sizes."They explained that, in the past couple of years, the power-tomsizes became their standard drum. They have the super powertoms, but the standard drums that have been around since the '20sand '30s, they call the jazz drums now. So when you see picturesof me behind a drumset in an ad, it's deceiving. It's my setup, butthose aren't my sizes. I use Pearl jazz-size toms, 10", 12", 13", and14" and 16" floor toms, an 18 x 22 bass drum, a Pearl piccolosnare, a Pearl standard-size metal snare, and I have a LudwigBlack Beauty and a 6 1/2" regular Ludwig metal snare drum.RF: I know you endorse Paiste Cymbals. What hi-hats do youfavor, since that's one of your trademarks?JP: I have several pairs I like. I have a pair of 602 Paistes that I'm inlove with. I have a pair of 13" Zildjians—a Z on the bottom and aK on top. One of my favorite pairs is an old, old, old A Zildjian 14"on top and an Italian Tosco on the bottom that has four quarter-

Pho

to b

y Ja

eger

Kot

os

inch holes drilled around the bell and two setsof rivets on each north, south, east, and westpoint on the bottom cymbal. They're incred-ible. This Tosco is real thick, but very brittle—not a lot of harmonics on the bottom. Thatcombination worked out great. I got the Toscocymbal when I was in Italy with Toto.RF: Was work on the hi-hat something youconcentrated on as a kid?JP: No. It was probably the last instrument tocome into my repertoire of drum instruments. Ifit had been important to me or I had studiedthe hi-hat or paid special attention to the hi-hatin general, it would have been easier. Thisyear, I'm finally comfortable playing quarternotes on the hi-hat through a whole tune orthrough a whole groove. See, I was never taughtthat way, so my foot would stay sti l l ._l wastaught to chick the hi-hat on 2 and 4 from oldbebop records, and everything else involvedplaying the hi-hat closed or a little bit swishyopen. I used to listen to all those Sly Stonerecords with Greg Errico, and I loved his hi-hatstuff, and the guy who took over for him, AndyNewmark. I stole a lot of hi-hat stuff from thosetwo guys, plus David Garibaldi and BernardPurdie.RF: So you did think about it?JP: I thought as much about it as I did bassdrum and snare drum stuff. I'm talking aboutduring this period when I was really picking upstuff. Pre-disco R&B stuff had a lot of hi-hathappening. Funk had a lot of nice hi-hat stuffgoing on, like David Garibaldi and the TowerOf Power stuff. But what I never realized ornever heard or had the ears to hear, was thatBernard always kept quarter notes, 8th notes,or even 16th notes going on the hi-hat with hisfoot—sometimes loud or sometimes real tightand short—while he was playing 16ths or 8thsor whatever on top. This didn't become obvi-ous to me until I got out into the real world andsaw a lot more drummers playing. And when Iwould try to do that...I'm not the most ambi-dextrous type guy, so coordination with myfeet would be real funny. John Guerin does

stuff with his foot that blew my mind.Tony Williams would blow my mind, sothen I'd go, "Gee Jeff, you've got to learnat least how to play quarter notes. Ohyeah, this helps my time if I keep quarternotes going while I'm filling. Good idea,Jeff." I didn't realize that until I was 21years old. By the time I got to be 25 and26 there were Vinnie Colaiuta and allthese guys whose hi-hat technique andability was incredible. So the only thingI ever woodshed if I'm sitting at a set ofdrums is doing quarter notes with myleft foot.RF: Back to The Seventh One. What areyour favorite tracks?JP: I like them all, I really do. I thinkeach one stands on its own merits.RF: Did you have particular fun on anyof them?JP: I had fun on "Mushanga" because,walking into the studio, I knew what thething was going to be, but I wanted tothink of a new beat for me—somethingdifferent. I didn't want one of those situ-ations where, after I heard what I did, it

ends up that I stole it or I'd heard it before in some sort of context.It was fun doing that beat. Now that I know it, I wish we could cutthe track again. It was one of those things where I had to figure outthe sticking a certain way; there are no overdubs.RF: Can you explain the beat?JP: No, this beat of all beats you cannot explain, [laughs] It'simpossible. I sat for an hour trying to explain it to my dad, and hewas cracking up because it involves hitting every drum, the rim,the head, the hi-hat, and it's all this split-hand stuff. It's basically asimple thing once you do it, but it's confusing to figure out for thefirst time—at least for me. And as soon as I got it, it was, "Quick,let's cut the track." We just cut it with David and me, and I wentinto a trance and tried to remember it, because a lot of it had to dowith me just getting comfortable with my sticking. The track cameout great, but then after we cut it, I finally got the beat down andstarted adding more things, like playing quarter notes on the hi-hatand things like that.

And I like "These Chains," but that's because it's exactly a rip-off of Bernard Purdie doing "Home At Last" on Aja. It's not exactlythe same beat, but that was the sole inspiration, just like with"Rosanna." I like "Stay Away" a lot, the rock 'n' roll thing withLinda Ronstadt, and I like "Anna" a lot, and the whole damnalbum.RF: The bio also says that there has been sort of a re-commitmentto the band, and that you guys are taking less session work inorder to spend your energies here. Is that accurate?JP: Every day that anything is needed for Toto, we're all committedto being here for what we need to do—whether that means tour-ing, making a record, writing, or whatever. Any time in between isup to each individual guy to do what he wants to do with it. Me,I've always done a lot of sessions, and I still do. I've got to admit it,I do sessions. Other guys in Toto have been writing more. When Iwake up, I don't get inspired to spend a day or a week writing; thattalent is not a natural thing in me. But when I wake up in themorning, I'm tapping my foot, so it's nice if I have a studio to go toso I can play some drums.RF: I want to go through a list of songs and have you tell me howyou came up with the groove and the patterns, and what was theinspiration and the approach.JP: It's hard for me to remember that stuff, but I'll do the best I can.RF: Do you remember "Your Gold Teeth II" (Steely Dan)?JP: Oh yeah! I definitely recall "Your Gold Teeth II." It was writtenin 6/8, 3/8, and 9/8; that is the way the bar phrases were writtenfor us. It was Chuck Rainey, me, and Michael Omartian for thebasic tracking session. We ran it down once, and all of us thought,"Wow, this is going to be unbelievable," especially me, because I

Pho

to b

y Ja

eger

Kot

os

L I S T E N E R S ' G U I D EQ. For readers who'd like to listen to albums that most represent your drumming, which ones would you recommend?(Please list in order of preference.)

Album Artist Label Catalog #

Katy LiedSilk DegreesToto IVTeaserAbout Face

Steely Dan

Boz ScaggsToto

Tommy Bolin

David Gilmour

MCA

Columbia

Columbia

Nemperor

Columbia

37043

PC-32760

PC-37728

PZ-37534

PL-39296

Q. Which records have you listened to the most for inspiration?

Album

Pretzel Logic

The Royal Scam

Aretha: Live At The Fillmore West

Accept No Substitute—The Original Delaney &Bonnie & Friends

Houses Of The Holy

Artist

Steely Dan

Steely Dan

Aretha FranklinDelaney & Bonnie

Led Zeppelin

Drummer

Jim Gordon

Bernard Purdie

Bernard PurdieJim Keltner

John Bonham

Label

MCA

MCA

Atlantic

Atco

Atlantic

Catalog #

37042

37044

7205

Out Of Print

SD-19130

was 21 and I wasn't the most experienced bebop player—and Iam of the same mind today. When I heard "Gold Teeth II," the firstreaction in my nervous little body was, "I am the wrong guy; Ishould not be here," knowing the kind of tune and knowing thoseguys real well. They weren't really aware of a lot of drummersback then, but they were aware of Jim Gordon, and I thoughtGordon could do a better job playing that. He was more experi-enced at getting a better feel. I was very nervous about it. Fortu-nately, the whole rhythm section had a bitch of a time. This wasmy first sight-reading.RF: It's a hard song.JP: Not only that. You say, "Okay, it's a big band...," but it's not abig band. It's a little quartet composition, and the phrasing of thelyrics also had to swing. Fagen did the perfect thing. We lived neareach other, and we would hang out and listen to Charlie Mingustogether. He gave me some Mingus album with Dannie Richmondon drums, and he said, "Listen to this for two days before comingto the studio." So I listened to Dannie Richmond and tried to copya couple of things he was doing and copy a couple of things that Ihad heard my dad play. There was this Mingus vibe to the rhythmof the song. I remember that everybody had such a hard time thatwe would record other Steely Dan songs, and every night beforewe'd leave, we'd play "Gold Teeth II" once. I think it was aboutthe fifth or seventh night of a four-week tracking date that we gotthe track of "Gold Teeth II." Next?RF: "Lowdown" (Boz Scaggs).JP: "Lowdown" is from a David Paich composition that he wrotefor what would be Toto. David and I had done some demos in late'75, early '76. There was this one song that, when we got to thefade, we snapped into a completely different groove. That groovewas bass drum on 1, the last 16th note of the second beat, and thethird beat, 16th notes straight on the hi-hat, and snare drum on 2and 4. Boz Scaggs heard this song and said he wanted to do it, butPaich said no, it was going to be for a group we were going tohave one day, but he would give him the fade. So Paich took thefade and wrote "Lowdown" for Boz. Boz wrote lyrics and melodyand stuff, and we went into the studio. When we cut "Lowdown,"it was 1976 and there was an Earth, Wind & Fire album out that Ihad been playing over and over again. It might have been I Am orthe one before that. Instead of 16ths, the groove was quarter noteson the hi-hat with the same beat I just described. We wanted toget that kind of Earth, Wind & Fire medium dance-groove rhythm.But instead of doing quarter notes, I did 8th notes, so if you take

the figure I described to you and substitute 8th notes on the hi-hat,and every two bars or so open the hi-hat on the last 8th note of thefourth beat, that's it.

We cut it that way, but the producer said, "Gee, do you want totry adding 16th notes?" because disco was starting to come inaround '76. I wasn't the keenest guy on disco and said, "Naw, youdon't want to do that, man. You don't want to ruin the groove."He said, "Just try it," and Paich and Boz said so too, so I over-dubbed the hi-hat, which they put on the opposite side of thestereo mix. While I was overdubbing the simple 16ths, I starteddoing some accents and answering my hi-hat stuff, and it got to bea lot of fun.RF: "Love Me Tomorrow" (Boz Scaggs).JP: The most reggae that I had heard at that part of my life wasprobably Bob Marley. I hadn't heard of Peter Tosh or any of thosecats yet. Maybe the most up-to-date record that would tell youwhat I'm talking about would be "Kid Charlemagne," but if youlisten to the groove on that and on "Haitian Divorce" from TheRoyal Scam, that's Bernard Purdie. You'll hear some of the samekind of groove on the Aretha and King Curtis Live At the FillmoreWest albums, both of which Bernard Purdie played on. On KingCurtis Live At the Fillmore West, when they do "Memphis SoulStew," you get a taste of this Bernard Purdie loop that I've heard alot from Rick Marotta, too. My main influence for "Love MeTomorrow" was the Bernard Purdie kind of shuffling type loop,very reggaeish, but it's a bad imitation of Purdie.RF: Were those timbales on it?JP: Yes, set up right by the drums, and it was me.RF: "Hold The Line" (Toto).JP: That was me trying to play like Sly Stone's original drummer,Greg Errico, who played drums on "Hot Fun In The Summertime."The hi-hat is doing triplets, the snare drum is playing 2 and 4backbeats, and the bass drum is on 1 and the & of 2. That 8th noteon the second beat is an 8th-note triplet feel, pushed. When wedid the tune, I said, "Gee, this is going to be a heavy four-on-the-floor rocker, but we want a Sly groove." The triplet groove of thetune was David's writing. It was taking the Sly groove and mesh-ing it with a harder rock caveman approach.RF: "Georgie Porgie" (Toto).JP: "Georgie Porgie" is imitating all the Maurice and FreddieWhite stuff, it's imitating Paul Humphrey heavily, it's imitatingEarl Palmer very heavily. When it comes to that groove, my

It seems hard to believe that it's been sevenyears since the release of Jean-Luc Ponty'salbum Mystical Adventures. When that albumwas first released in 1981, fusion-drummingfans kept asking, "Who is this guy?" and"Where did this guy come from?" This "guy,"drummer Rayford Griffin, came out ofnowhere with a sound and style all his own.

For followers of fusion music, masterelectronic violinist Jean-Luc Ponty is nostranger. His first major exposure came frombeing a member of the second MahavishnuOrchestra, and since that time Ponty hasbeen one of the few original fusion artists tosuccessfully lead his own band. These bandshave included some of the finest musiciansperforming today, including Ndugu Chancier,Mark Craney, Casey Scheuerell, and SteveSmith. It's a testament to Rayford Griffin'stalent and ability that he has remained inPonty's band for longer than any previousdrummer, having recorded five albums withthe violinist thus far.

by William F. Miller

Besides his main gig with Ponty, Rayford has worked with sev-eral other artists including Patrice Rushen, Cameo, Wilton Felder,The Isley Brothers, George Howard, and Stanley Clarke. In fact, ina recent Musician magazine interview, Stanley Clarke singled outRayford as being the best young drummer happening today.

The following interview was conducted before a performancewith Jean-Luc Ponty at Carnegie Hall. At that concert, Rayfordshowed why he has been so highly touted. He combined tastewith a great degree of technical skills, and his drum solo broughtthe capacity audience to their feet. For a man who came out of no-where seven years ago, Rayford Griffin has risen to become one ofthe best.WFM: Where are you from originally?RG: I'm from Indianapolis, Indiana, but I lived in Houston for alittle while. I started playing drums in Houston when I was ten,and I moved back to Indianapolis in '69. I played in the marchingband and did all of that. I studied for about three years during highschool with Tom Akins, who is the timpanist with the IndianapolisSymphony Orchestra. I attended a whole year [laughs] at IndianaState in Terre Haute as a music major studying percussion. Then Ijoined a band called Merging Traffic, and on our second gig weopened up for Jean-Luc Ponty. That was in 1977. In 1978, Jean-Luc toured through town again, and we opened for him again. In'79, he came to town again, and this time I went to the show andtalked to him backstage. He remembered me from the previoustwo years, and he told me to send him a tape. About nine monthslater, Jean-Luc called and said that he was holding auditions. I hadto scrape and borrow the money just to fly out to L.A. for the audi-tion. I ended up getting the gig.WFM: What type of music were you playing in Merging Traffic?RG: It was fusion, very similar to what Jean-Luc was doing at thetime. Return To Forever was an influence. It was all originalmusic. The style was from what I call the original fusion style. Theword "fusion" has since become bastardized, in my opinion. WhenI think of the term "fusion," Jean-Luc, Return To Forever, BillyCobham, Chick Corea, and all those cats who pioneered the styleare what come to mind. Now "fusion" is used for acts such asSpyro Gyra or Grover Washington, and to me, that just doesn't getit.

WFM: Tell me about your audition for Ponty.RG: Well, I was bugging out because most of the other guys whoauditioned were from L.A., or at least from California, so they allhad their drums. Since I was coming from Indianapolis, I couldn'tafford to fly my drums out there. I did bring my snare drum andcymbals, though. I had been playing a lot of double bass, so that'swhat I would have preferred to audition on, but they rented asingle bass Ludwig kit, so I wasn't that comfortable with it. Iplayed the audition, and Jean-Luc told me to come back the nextday because he wanted to hear me again. However, the nextmorning he called me back to say that he had listened to the tapeagain and that I could have the gig, without having to play for himagain.WFM: What did Ponty have you play at your audition?RG: Well, we played things from his previous album at that time,which I was very familiar with because I was so into his style. Iwas accustomed to the way that his music was played and the wayother guys interpreted his music. Randy Jackson, who had playedwith Narada and Billy Cobham, was playing bass for the audition.Randy and I locked right in. In fact, during the audition Jean-Lucasked us if we had played together before. I think we were so tightbecause he had worked with Billy and Narada, and I was soheavily influenced by their music that we thought in a very similarmusical way. Everything just worked out great.WFM: Were you intimidated at all knowing that you were follow-ing in the footsteps of some very impressive players? Ponty hadplayed with Narada in the second Mahavishnu Orchestra, and hehad people like Ndugu Chancier, Steve Smith, and Casey Scheuer-ell in his bands previous to you. I would think that might beintimidating.RG: I wasn't that intimidated. I had done a lot of playing up to thatpoint, and whenever I would listen to those albums, I would say tomyself, "I can do that!" I kind of had that attitude. I was nervous atthe audition though, mainly because I was playing a set that Iwasn't familiar with.WFM: I'd like to backtrack for a minute and find out how and whyyou started drumming.RG: My uncle was Clifford Brown, the jazz trumpeter. I can re-member being five or six, and hearing my uncle's records. Fromlistening to those records, the thing that my ear went to more thananything else was the drums. I was always beating on stuff withpencils. When I was in fourth grade, my brother Reggie startedplaying saxophone. I was like, "He's playing saxophone; I want toplay something too!" So I started studying drums. It seems to methat, even way back then, I knew that playing the drums was whatI wanted to do for the rest of my life. I wanted to play music as op-posed to being a banker or a fireman or an astronaut.WFM: Since Clifford Brown was your uncle, I would imagine thatjazz was your first big influence.RG: Well, when I first started playing, I only had one drum. WhenI finally did get a drumset, it wasn't jazz that I was playing. I usedto go down in the basement and listen to Kool & The Gang, IsaacHayes, and Jimi Hendrix. A few years later, my brother startedbringing home Mahavishnu Orchestra albums, and I got into that.As a matter of fact, that freaked me totally out. For a long time, Ithought Billy Cobham was the only drummer alive. Everybodyelse, to me, was just bullshittin' on the drums. All the bands that Iplayed in were a little more progressive. I never really played in aTop-40 band, which I think helped to prepare me for the music Iplay now with Jean-Luc.WFM: What type of formal training did you have?RG: It was mainly just drumset and timpani, back when I wasstudying with Tom Akins.WFM: Did you have any rudimental training? I seem to hear a lotof that in your playing.RG: That's what a lot of people say. There wasn't a lot of emphasison rudiments when I was studying. I was taken through the rudi-ments when I was younger. I would practice what was there, but Ididn't put much emphasis on it. It surprises me that people thinkI'm that type of drummer, because I have never thought of myselfthat way. I never did any drum corps or anything like that.WFM: Your first name gig was with Jean-Luc Ponty. How long

Pho

to b

y E

bet

Rob

erts

Griffin's Groovesby William F. Miller

The grooves that follow demonstrate some ofRayford Griffin's playing on a few different Jean-Luc Ponty recordings. Rayford's confidentdrumming always grooves, whether he is playinga complicated odd meter or a simple rock beat.And his excellent technique can be inspiring.

This first example is the title track from thePonty album Mystical Adventures (Atlantic SD19333), and this is the beat that Rayford plays on

part 1. When playing this beat be sure to open the hi-hat whereindicated. This beat isn't as easy as it looks.

The next example is also from "Mystical Adventures," this beingpart 3 of the suite. The first measure is the pattern Rayford playsduring the bridge section of the tune, and the second measure isfrom the guitar solo section.

The following beats are from the tune "Jig," also from /Adventures.The first measure is the intro pattern, and the second is the solo-section beat.

The next three examples are from the Jean-Luc Ponty albumFables (Atlantic 7 81276-1). This two-bar phrase from "ElephantsIn Love" really grooves.

This odd-meter beat is from the tune "Radioactive Legacy." Noticehow the accents on the hi-hat set up four-note phrases that remainconstant, which changes the emphasis from an upbeat feel to a

This last example is from the song "Metamorphosis."

The last two examples are from the most recent Jean-Luc Pontyalbum, The Gift Of Time (Columbia FC 40983). This rathercomplicated beat is from the tune "New Resolutions," from theending section of the song. Rayford accents on the hi-hat andplays tom notes that correspond with the other instruments on thetrack.

This is the beat to "Cat's Tales," which Rayford plays in the guitarsolo section. This beat looks simple, but the way these few notesare phrased makes for an interesting beat.

downbeat feel when going from measure to measure.

Pho

to b

y Li

ssa

Wal

es

Rikki Rockett takesissue with those

who think of drumsas a backup instru-

ment and drummersas musicians who

support the "key fig-ures'" in a band. Inthe years since he

and singer BretMichaels organizedthe successful rock

group Poison, Rikkihas worked long

and hard to becomea drummer who is

as entertaining visu-ally as he is acousti-

cally. Leaping frombehind his drumkit,

flailing his armsabout, and generallymatching the chore-ography of the band

is Rikki's uniquestyle of showman-

ship. So it's not sur-prising that many

fans come to Poisonconcerts just to see

and hear RikkiRockett play.

Photo by Mark Weiss

MD: When did you first take an interest indrums?RR: I was 10 years old at the time, and mysister had a boyfriend who played bongos.One day he left them out in the car, and Itook them into the house and started play-ing around. I liked them so much that whenhe came looking for them, I hid them un-der my bed. Eventually, I confessed to thetheft, and because he already bought anew set, he let me keep them.

role models in the beginning?RR: Peter Criss from Kiss, Bun E. Carlos ofCheap Trick, Joey Kramer of Aerosmith, PhilRudd from AC/DC, Joe X. Dube [Starz],Dicky Diamond [Sparks], and of course,Keith Moon.MD: And now?RR: There are so many great drummers outthere. I can always pick up ModernDrummer and find an interview on a greatdrummer—sometimes someone I'm not

other drummers?RR: I study their techniques, even play alongto their records, but my playing will neversound exactly like theirs because I havemy own interpretation and style of playing.Our new album, Open Up And Say...Ahh!,has some real boogie-woogie type songs.For ideas, I went back and listened toTommy Aldridge, who's a great rhythm &blues drummer. When it came time forsomething more solid, more rock-bottom, Itook time to listen back through Led Zepalbums. I think it's important to not getburied in a one-style coffin.MD: How important is showmanship toyou?RR: I think it's very important; it's impor-tant to rock 'n' roll in general. Musician-ship, image, and showmanship in roughlyequal parts is ideal.MD: On stage, you seem to enjoy leapingout from behind the drumkit. Does thishelp your playing or is it just pure show-manship?RR: [laughs] It's my medication! No, at anytime you do something other than just play,your concentration and accuracy are at risk.It can be very difficult to do both, but it is ashow, so both are important. Who said itwas supposed to be easy?MD: Throwing in some extra visuals seemsparticularly important since Poison is a vis-ual, excitement-oriented band.RR: That's right. Frankly, a lot of bandswon't tour at all because they feel their liveperformance will endanger their credibilityas musicians, and a lot more shouldn't p\aylive, because they're so damn boring towatch!MD: How do you prepare for the tensenessand excitement of a live show and stillremain psyched up for it?RR: I'm always a nut case just beforeshowtime. I have to keep moving; I stretch,do some sticking that Bun E. Carlos showedme, and basically go over the show in mymind.MD: Does the excitement of being on stagehelp your playing, and do you miss that inthe studio?RR: Oh, definitely! It does change thingsbeing in the studio. I approach the studioin a whole different way. I strive for preci-sion while trying to envision what it will belike live; that gets me excited and keepsmy enthusiasm up. That's what rock 'n' rollis all about.MD: Do you prefer recording live, with allthe band members playing at once, or multi-tracking each instrument one at a time,looking for technical perfection?RR: I love a "live" sound. But in order tocompete with other bands that do exten-sive multitracking and overdubbing and

Photo by Anna Maria DiSanto

MD: So you were on your way to becom-ing a drummer...or a thief. When did youstart playing acoustic drums?RR: When I was 12 my parents bought—and let me emphasize the word "bought"—me a set for $50. I began practicing to mymom's Elvis records, my sister's Beatles rec-ords, and my own Johnny Winter albums. Inever had a bona fide teacher, althoughmy brother-in-law—the guy I stole the bon-gos from—taught me pretty much every-thing he knew.MD: Did you do any playing in school?RR: After a brief attempt at trying to playtrumpet in a school band, I decided tostick to drums and rock 'n' roll, my firstloves. During the next several years, I wentthrough a slew of basement bands. Eventu-ally I formed a band that got gigs playingclubs in our home state of Pennsylvania.Things really started happening when Ihooked up with Bret Michaels and weformed Paris, a visually-oriented band thatwas basically the same concept as Poison.Bobby and C.C. joined up, we moved toLos Angeles, changed our name to Poison,and started working the local club circuit.MD: Who were your drumming heroes or

even familiar with—and learn somethingfrom that person because of his or her skill.But if I'm going to name names, I guess I'dalso add Alex Van Halen, Bobby Blotzer,Tony Thompson, Shelia E., Neil Peart, BillBruford, Terry Bozzio, and Tommy Lee.MD: All these people influence the workyou do, combined with your own experi-ence?RR: Yes. I think you can't help but wind upbeing a product of your influences.MD: How so?RR: It's almost automatic to try things you'veheard on records, to see if something likethat will work for what you want to do.Influences become a point of reference. Iusually try all sorts of things covering abroad range of music. By the time I'vesettled in on something or some combina-tion of things that fit the part I need, it'sbecome my own style.MD: So you don't consciously try to copy

"A LOT OF BANDS SHOULDN'T PLAY

LIVE BECAUSE THEY'RE SO DAMN BORING TO WATCH!"

such, you have to utilize the technologyavailable now. My goal, though, is to gointo the studio, shoot for technical perfec-tion, but make it sound like I just went inthere and winged it. I don't want it to soundlike there's an orchestra or all these se-quencers going off. When the people whobuy records see you live, they want to hearthe same sound, to see you play what theyhear on the record.MD: Then you don't use electronic drumson stage?RR: I do, but only for effects. The fans wantto see what the hell I'm hitting.MD: Do you prefer acoustic drums to elec-tronic drums?RR: I do. Most of the new electronic drumsare touch-sensitive, but there's still a cer-tain feeling missing...and you can't hit rims.I like electronic drums and I think theyhave their place. Out on tour I know thatthere's going to be some effects I've used inthe studio that I'll want to reproduce live.The only way I'm going to be able to dothat is to sample the sounds and pop themout later on stage. So there are times whenI'll use electronic drums.MD: So the new album was done with liveacoustic drums?RR: Yes. I thought at some point in time Imight have to go back into the studio andoverdub a bunch of samples, but I did onlya few samples. There were a couple oftimes I used RotoToms for the beginning ofa song or someplace where I wanted a veryspecialized sound. Basically, we did thewhole album with straight acoustic drumsand a few samples thrown in here andthere for the fun of it.MD: Are you more satisfied with your per-formance on Open Up And Say...Ahh! ascompared to Look What The Cat DraggedIn?RR: I like it a lot better! I had more timeand money at my disposal. Look What TheCat Dragged In was done in 12 days on a$30,000 budget. I know guys who spendthat kind of money on drum tracks alone inone day. As we were working on the newalbum, if something didn't sound right tome, I could move on to the next song. Thenext day, after I'd thought it over and messedaround with the troublesome part, I'd try itagain. This has been the most comfortableI've ever been in a studio situation. I hadthe drums set up the way I wanted them,and I was surrounded by a group of verypositive people.MD: Positive as in "yes men"?RR: Definitely not. Positive in the sensethat if I made a mistake, the producer orengineer would say, "That was a little 'outthere,' but everything else sounded great,so let's take it again." Somebody else might

have said, "Hey! What's wrong with you?You're really screwing up!" In the studio,you've got to have people who are bothpositive and helpful, because it's almostinevitable that you're going to be hard onyourself.MD: When you listen back to the workyou've done, do you tend to be overlycritical?RR: I think almost every musician, afterlistening to his own work, thinks he couldhave done it better. It's all because youwant to do the very best you can. If I do adrum track and two weeks later I listen toit, I'm sure I could have done it better.MD: Is that how you feel about Open UpAnd Say...Ahh!?RR: With this new album, I put in a lotmore time than I ever have before—cut outmy social life and even lost my girlfriend. Iwould go to rehearsal at 1:00 in the after-noon and not finish until about 9:00 atnight. Then I'd take my portable four-trackhome and use either my drum machine orplay beats on the Octapad. I would playjust kick and snare the whole way throughon track two, and turn around and play hi-hats and fills on track three. After a while,I'd have a whole song with drums included.I'd be able to sit back and say, "Now, whenthis goes on the vinyl, am I gonna want itto sound like this?" I figured, once I had

everything in my mind, then it was downto where it sounded like a good song. Timeafforded me that luxury. We really had torush our first record. The most we hoped togain from it was enough groundwork to setourselves up for the next record—a biggerbudget, more time, and some name recog-nition. But it turned out that Look WhatThe Cat Dragged In really skyrocketed. Itdid ten times what we hoped it would do.But I still listen to it and think, "God, I wishI could've done it differently."MD: Are you a "feel" player as opposed toa "technical" player?RR: I guess I am more of a "feel" player. Idon't play mathematically. I don't reallycount things out unless there's a breakcoming up or there's something that has tobe counted. I can read music to a degree,but I'm very slow at it. I certainly can'tsight read, but I can figure out a chart if Ireally look at it for a while, play aroundwith it, and have someone tell me whetherI'm right or wrong.MD: Do you consider this a weakness foryou?RR: Yes, and it's something I've started towork on. Using a drum machine and learn-ing to program it has helped me learn nota-tion and charts a helluva lot more.MD: Do you try to play right on the beat,behind it, or ahead of it?

Drums: DrumWorkshop withcustom greenfinish.Cymbals:Zildjian.A. 8x 14brass or 6 x14 maplesnareB. 9 x 1 0rack tomC. 10 x 12 rack tomD. 12 x 14 floor tomE. 14 x 16 floor tomF. 16 x 22 bass drumG. 16 x 22 bass drumH. Duo Pads (electronicdrums)1.14" Z Dyno Beat hi-hats2. 10" A splash3. 17" A rock crash4. 20" or 22" Z Heavy Power Ride5. 18" K crash ride6. 18" A medium crash7. 19" K China Boy8. LP cowbellHardware: A combination of DW hardware with a Collarlockdrum support system. DW hi-hat, DW 5000TE bass drumpedals.Electronics: Dynacord Add-one digital drums and DrumWorkshop Duo Pads (kick and snare only) triggering Rikki'sown samples using an Akai S-900 digital sampler.