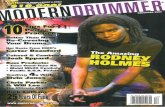

Apr-May 1980 - Modern Drummer Magazine

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

1 -

download

0

Transcript of Apr-May 1980 - Modern Drummer Magazine

MODERN DRUMMER

FEATURES:

VOL. 4 NO. 2

NEIL PEARTAs one of rock's most popular drummers, Neil Peart of Rushseriously reflects on his art in this exclusive interview. With arefreshing, no-nonsense att i tude. Peart speaks of the experi-ences that led him to Rush and how a respect formed betweenthe band members that is rarely achieved. Peart also affirms hisbelief that music must not be compromised for financial gain,and has followed that path throughout his career. 12

PAUL MOTIANJazz modernist Paul Motian has had a varied career, from hisdays with the Bill Evans Trio to Arlo Guthrie. Motian assertsthat to fully appreciate the art of drumming, one must study thegreat masters of the past and learn from them. 16

FRED BEGUNAnother facet of drumming is explored in this interview withFred Begun, timpanist with the National Symphony Orchestraof Washington, D.C. Begun discusses his approach to classicalmusic and the influences of his mentor, Saul Goodman. 20

INSIDE REMO 24 RESULTS OF SLINGERLAND/LOUIE28BELLSON CONTEST

COLUMNS:

EDITOR'S OVERVIEWREADERS PLATFORMASK A PROIT'S QUESTIONABLEROCK PERSPECTIVESOdd Rockby David GaribaldiJAZZ DRUMMERS WORKSHOPDouble Time Coordinationby Ed SophELECTRONIC INSIGHTSSimple Percussion Modificationsby David ErnstSHOW AND STUDIOA New Approach Towards Improving Your Readingby Danny Pucillo 40

38

34

32

8643 TEACHERS FORUM

Teaching Jazz Drummingby Charley Perry

THE CLUB SCENEThe Art of Entertainmentby Rick Van Horn

STRICTLY TECHNIQUEThe Technically Proficient Playerby Paul Meyer

CONCEPTSDrums and Drummers: An Impressionby Rich Baccaro

DRUM MARKET

INDUSTRY HAPPENINGS

JUST DRUMS 71

70

54

52

50

48

42

The feature section of this issue represents a wide spectrum of modernpercussion with our three lead interview subjects: Rush's Neil Peart;jazz drummer Paul Motian and timpanist Fred Begun.

The Neil Peart interview was a story we pursued for many months.Coordinating a meeting place was not easy considering the extremelyhectic road schedule the band maintains. We finally tracked them downat a fairgrounds concert in Allentown, Pennsylvania where MD's CheechIero spoke to Peart at considerable length. A talented and opinionatedartist, Neil discussed numerous aspects of his music. Not impressed bymob fan adulation, Peart maintains a philosophy indicative of theseriousness with which he views his drumming; "If I go in front of 35,000people and play really well, then I feel satisfied . . . adulation meansnothing without self-respect."

Paul Motian has been on the New York jazz scene for quite some time.He's worked with Keith Jarrett, Stan Getz, Thelonius Monk, Lee Konitzand Charles Lloyd, and was a key member of the celebrated Bill Evanstrio with bassist Scott LaFaro. Motian talks about his involvement withcomposing and his affinity for the drumming masters of the past: "Allmusicians should check out the tradition of the instrument. . . their typeof playing is connected with the way people are playing today.

Orchestra in Washington, D.C. for nearly 30 years. This Juilliard trainedpercussionist discusses his background as a student of Saul Goodman,his aspirations as a writer, and the current state of percussion ensembleliterature.

If you've ever wondered what goes on inside a drumhead factory,MD's David Levine has the full story. His Inside Remo tour takes youevery step of the way through the firm's 54,000 square foot facility insouthern California. Company president and founder Remo Belli talksabout the early days of Remo, Inc., the plastic drumhead, and thechallenges which face the company in the future.

A Day In Las Vegas, reported by Laura Deni, is the completelowdown on the finals at the Slingerland/Louie Bellson National DrumContest. Thirteen young drummers under the age of 19 competed at theUniversity of Las Vegas for thousands of dollars in prize and scholarshipmoney and an opportunity to appear with Bellson on Johnny Carson'sTonight Show. It turned out to be quite a contest and an event we hopewill be repeated each year. Our hats are off to Lou Bellson and all thoseat Slingerland who were responsible for coordinating this incredibleproject.

We'd like to welcome David Ernst and Charlie Perry to the columnroster this year with Electronic Insights and Teachers Forumrespectively. Both gentlemen are experts in their fields and have a greatdeal to say.

Another new entry for 1980, making its debut with this issue, is TheClub Scene, a highly informative column containing some great advicefor drummers active in the competitive club date business. Author RickVan Horn has a wealth of experience in this area and we think you'll findhis column a real winner.

The results of MD's Second Annual Reader's Poll are now beingtabulated. You'll find the exciting results in our June/July issue, alongwith Part 1 of The Great Jazz Drummers: An Historical Perspective, anda revealing exclusive interview with the extraordinary Carl Palmer.

STAFF:

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Ronald Spagnardi

FEATURES EDITOR: Karen Larcombe

ASSOCIATE EDITORS: Mark HurleyPaul Uldrich

MANAGING EDITOR: Michael Cramer

ART DIRECTOR: Tom Mandrake

PRODUCTION MANAGER: Roger Elliston

ADVERTISING DIRECTOR: Jean Mazza

ADMINISTRATION: Isabel LoriAnn Lambariello

DEALER SERVICEMANAGER: Carol Morales

CIRCULATION: Leo L. SpagnardiMarilyn MillerMaureen Politi

MD ADVISORY BOARD:

Henry Adler Mel LewisCarmine Appice Peter MagadiniHoracee Arnold Mitch MarkovichLouie Bellson Butch MilesRoy Burns Joe MorelloJim Chapin Charley PerryBilly Cobham Charlie PersipJoe Corsello Joe PollardLes DeMerle Arthur PressLen DiMuzio Paul PriceCharlie Donnelly Ed ShaughnessySonny Igoe Lenny WhiteDon Lamond

MODERN DRUMMER Magazine (ISSN 0194-45331) is published bi-monthly, February,April, June, August, October and Decemberby Modern Drummer Publications, Inc.. 1000Clifton Avenue, Clifton, N.J. 07013. Secondclass postage paid at Clifton, N.J. 07013 andat additional mailing offices. Copyrighted1980 by Modern Drummer Publications, Inc.All rights reserved. Reproduction without thepermission of the publisher is prohibited.SUBSCRIPTIONS: $9.95 per year. $19.00.two years. Single copies $1.75. MANU-SCRIPTS: Modern Drummer welcomes man-uscripts, however, cannot assume responsi-bility for them. Manuscripts must be accom-panied by a self-addressed stamped envelope.CHANGE OF ADDRESS: Allow at least sixweeks for a change. Please provide both oldand new address. MUSIC DEALERS: ModernDrummer is available for resale at bulk rates.Direct correspondence to Modern DrummerPublications, Inc.. 1000 Clifton Avenue. Clif-ton. N . J . 07013. (201) 778-1700 POST-MASTER: Send form 3579 to Modern Drum-mer, 1000 Clifton Avenue, Clifton. N . J .07013.

Fred Begun has been principal timpanist with the National Sympthony

I am writ ing in response to several pre-vious letters criticizing Carl Palmer.

Pleasing to mind and pulsating to soul.Palmer ' s a r t i s t ry d isp lays qua l i t i e sbeyond reproach. If anyone doubts hisability to show solid time with speed,balanced at fu l l t i l t , just listen to "TheEnemy God", ( l ive version). His re-spected standing is truly deserved andformidable.

THOMAS LAPOINTELAWRENCE, MA

I must congratulate you on an ex-cellent magazine. I much enjoy your in-terviews with drummers who have foundthe key to success, and your articles onthe current state of the art in drum equip-ment. But I was quite pleased to see ahuman interest type story "Flipped OverDrums" in your December-January is-sue. While working for RCA records atthe time Whitehorse was working ontheir album, I caught a few sessions andcan attest to the fact that Mr. Valentineis a fine and innovative drummer rightside up, as well as upside down. ThoughI never caught his act l ive , I heard nu-merous positive reports from the grape-vine. Keep up the off-the-wall ( in thiscase off-the-ceiling) type articles.

BOB SOLARPINOS ALTOS. NM

Modern Drummer Magazine is defi-ni tely a plus to both the drum and musicindustry. As the opportuni ty presents it-self, I can assure you that I plug yourmagazine in any way possible.

Perhaps the major thing that irks me isthe failure of the interviewers to obtainmore information on the equipment themusician uses. Some interviews seem tofocus more on the personal side of themusician, as opposed to the methods orequipment they use. This is fine with mebut I t h i n k the main purpose of MD is topresent drummers with information thatwil l be useful to develop the knowledgeof their trade.

JAMES E. VALLONEBUFFALO, NY

Just want to let you know that mydrum cases are weatherproofed! The ar-ticle was great. It was so easy going. Ilined them with red felt and they looksharp. Now I don't have to worry aboutdamaging my drums. Thanks again forthe instructions.

TONY SIGNORELLIPALM BEACH. FL

Michael Shore must be commendedfor his excellent interview wi th Barrie-more Barlow in the December/Januaryissue. I cannot th ink of a single point thatwas not covered regarding this superbdrummer. Barlow is so humble: his com-ments about his playing abi l i ty and tech-nique floored me. Again, thanks for anexcellent article.

BOBBY MCGLOWNMOBILE. AL

In regard to Charley Perry's article."Basic Brushes." I wish to question hiss t a t ements regarding t h e h i s t o ry ofbrushes. Mr. Perry states that, "brushesare a fairly recent addition to the drum-mer's arsenal . . . go back perhaps 40years and have been used almost exclu-sively in jazz and dance bands."

Actually, the brush (rute, switch, etc.)was known as far back as the time ofHaydn and Mozart, and was later re-ques ted by Mah l e r and Strauss . Theoriginal form of the brush was a bundleof twigs or a split rod. In Percussion In-struments and Their History, JamesBlade speaks of Mozart's Il Seraglio inwhich the Tamburo grande is playedw i t h both a s t ick and a "switch oftwigs," an effect which is "evident in theswish of the modern wire brushes."

HOWARD I. JOINESHATTIESBURG, Ml

Thank you for the tribute to the great-est man ever to play the drums. GeneKrupa. It is a true collector's item and Iwill keep my issue forever.

Gene and Cozy gave me drum lessonsat their school in Manhattan many yearsago. Although I was young at the time, Iwil l never forget the art of drumming theway the master taught it. He had pa-t ience and und e r s t a n d i n g and alwaystook the t ime to show the correct habitsof drumming. I 'm happy that I sharedsome of my greatest moments with thisman. Although I'm not famous like Bud-dy Rich or Louie Bellson, I play thedrums in the tradition of my friend andteacher—Gene Krupa.

ANTHONY GUARDINGBAYSHORE, NY

I 'm writ ing in reply to Jack Gilfoyfrom Indianapolis, Indiana, whose letterconcerning the Blue Bear School of Musicappeared in the December/January is-sue. He stated, "If the student is in-telligent enough, a master drummer willbe found who can provide somethingmore meaningful than a garage band en-vironment . Who needs to pay good mon-ey for that? "

I 'm a 17 year old progressive rock per-cussionist. I 'm one of the above men-tioned people who have played in garagebands. I have also played in c lubs ,theatres, gyms, etc. I listen to and appre-ciate classical music, but rock is my firstlove. I have had some classical trainingand it can be good, but it 's not the onlyway.

"Who needs to pay good money forthat? " In my area, club rock performersare in demand. Also, what about therockers who started in garage bands?They are now playing to sellout crowdsat $10 a ticket.

Mr Gilfoy: You do your thing and I'lldo mine. That's what keeps music alive!

FRANK SPICERVINELAND, NJ

TERRY SILVERLIGHTQ. Could you please give me some ad-vice on building endurance and speed formy left foot on the hi-hat?

Matthew PlumeriSt. Louis, MO

A. The first exercise I would recom-mend would be to play the hi-hat on thequarter notes (1, 2, 3, 4) of each bar, andalternate that with a bar of the hi-hat on 1and 3, while building the speed of thetempo. Eventually, substitute the 2 and 4with the snare drum.

For the second exercise, play the hi-hat on all four quarter notes of the bar,with any standard Latin, jazz, or rockand roll beat. Get used to the coordina-tion of playing the hi-hat on all the beatsagainst whatever you would normallyplay. Also, start slow with the hi-hat play-ing quarter notes and increase the tem-po until your leg starts to hurt. At thispoint, hold it there and keep going untilyou can't stand it any longer. Rest, andrepeat this procedure until you feel thepain once again, and keep it going aslong as possible. If you can do this about25 times a day, at the end of 2 weeksyou should definitely see an improve-ment.

Another exercise that is helpful to mewhen playing fast tempos on the hi-hat isto play with the toe of the foot, ratherthan the flat part of the foot or the heel-toe method. You'll probably find at slowto medium tempos the foot resting flat onthe hi-hat pedal will give you the controlnecessary, however very fast temposwill be played easier with the toe, be-cause all the weight of your leg will reston your toe, enabling you to create abouncing movement with your leg.

STEVE FERRONEQ. On Average White Band's latest al-bum Feel No Fret your playing was dy-namic. What were your thoughts whilerecording the title cut?

John MiltonLondon, England

A. When you put down a track, you'realways in a certain frame of mind. "FeelNo Fret" is a sort of West Indian influ-enced reggae groove. When we did thetrack, I was extremely angry. I was goingthrough some personal problems andyou could hear it in the drums. When youcome down to the mixing, you have to beable to bring out what was there in thebeginning. When you put down a track,you can hear it. You've got the track,then of course you add the vocals, andsweeten it. That's fine, but I don't thinkyou should lose what you had in the be-ginning. If you've got a good track, it's agood track!

at times to deal with the music business,so I would like to gain a little insight fromyou. If you care to elaborate on your rea-sons for leaving, or why you stoppedplaying, I would find this informative ingaining a perspective of the music busi-ness.

Gary DatesRed Bank, NJ

A. The incident you are referring to wasin 1974, and at that point I just needed abreak. So I left the group. I was tired ofdoing it. I just got married and needed tohave some answers in my life. It hadnothing to do with music, because thatpart was going very well, and I knew italways would. I just stopped and cooledout for a couple of months. I spent timewith my new wife and studied the Bible,because when the music was over I hadno answers in my life at all. So I went andfound some. That's basically what it was.At the time, I hadn't taken any time off inten years. When you work really hard atsomething for ten years you need abreak.

DAVID GARIBALDIQ. I am aware of the fact that at onepoint you left Tower of Power. I was alittle disturbed to hear this, as I regardedyou as having a bright future in the busi-ness. Now I realize how difficult it can be

Q. I am planning a cruise to the Caribbean next summer andwould like to bring back some percussion instruments dis-tinctive to that area. Can you give me some information on pos-sible places to look, and what to look for? I want to get awayfrom the usual tourist trinkets.

D.B.Athens, GA

A. Instruments of the Caribbean Islands are usually hand-made. Items which some people may consider trinkets turn outto be excellent percussion instruments. If you are in the marketfor steel drums, this is an ideal place to purchase them. Onceyou get there, get in touch with the working professionals. Theywill probably be able to guide you in the right direction.

Q. Could you give me some information on the death of thegreat drummer Chick Webb?

F.C.London, England

A. Chick Webb died of tuberculosis on May 16, 1939 in Balti-more, Maryland, at the age of 32.

Q. I'd like to know if there is a book listing all the drum com-panies and their addresses'? If so, where can I get one?

P.S.Las Vegas, NV

A. Since there have been numerous requests for this itemModern Drummer will soon he offering its Percussion IndustryDirectory; an up to date listing of percussion companies, drumshops, publishers of percussion music and literature, etc. Ad-dresses, phone numbers, and the products they make will alsohe included.

Q. How do you tune a 5 piece drum set in fourths?

C.N.Chicago, IL

A. Some drummers do not think in terms of tuning the snaredrum, or the bass drum to the scale being used. The pitch of thesnare and bass drums are simply made compatible to the rest ofthe tom tom voices. Other drummers utilize the snare and bassdrums in the scale. Whatever the school of thought, you mustremember the drum cannot be tuned to an absolute pitch, butcan only get into the range of that pitch. Assuming you areusing a standard 5 piece set, and are including all drums in thetuning process; tune your snare drum to middle C, left handmounted tom to C below middle C, right hand mounted tom toD below middle C, floor tom to A below D, and the bass drumto C.

Q. Where can I write to The Who's drummer Kenny Jones?

T.M.Antioch, IL

A. All correspondence for Kenny Jones may be addressed toThe Who's personal management: Trinifold, 112 Wardour,London, England, W1V 3LD.

Q. I am the section leader of my school orchestra's percussionsection and I have a problem. I play snare along with two othermembers and whenever we get to the 32 bar snare drum solo inthis one particular piece, we sound as though we are playingthree different parts after the first 8 measures. Any suggestions?

B.M.Billings, MT

A. Since you are in charge of the percussion section, call for asectional rehearsal. Discuss the part thoroughly. Find thetrouble areas, and discuss the type of strokes being used; stick-ing, the height of the strokes, and the dynamics. Practice thesolo individually and together at a slower tempo, graduallybuilding to the required speed. Most important, listen to eachother.

Q. How do the dimensions of the shell of a drum affect its tonalcharacter? Does depth and diameter alter pitch and sustain?

H.D.Oakland, NE

A. According to advisory board member Ed Shaughncssy,"Generally the deeper the dimension of the drum, the longerthe sustain. As for the diameter of the shell, the larger the head,the deeper the fundamental sound of the drum."

continued on page 10

It's Questionable: continued from page 8

Q. I have a white drum kit, only they're not white anymore.Any suggestions for the removal of yellowing that has occurredover the years?

J.N.GlenBurnie, MD

A. There's not much which can be done about the yellowing.Bleaching the shells can often crack the finish. Yellowing is of-ten caused by the nicotine from the smoke in night clubs.Drums displayed in store windows are often victims of the yel-lowing effects of sunlight. Preventive maintenance is the key!Keeping the finish waxed with a white cream car wax is helpful.

Q. Where can I obtain a book dealing with the study of Tabladrums?

M.H.San Jose, CA

A. Donald Robertson's Tabla, published by the Peer Inter-national Corporation, 1619 Broadway, N. Y., N. Y. 10019, is rec-ommended. It covers the history of the drum, developments,tuning, various strokes, etc.

CI: Tell me a l i t t l e about your set up.It's a beautiful looking set. What kind offinish does it have?NP: It 's a mahogany finish. The Per-cussion Center in Fort Wayne. where Iget all my stuff, did the finish for me. Iwas trying to achieve a Rosewood. Athome, I have some Chinese Rosewoodfurniture, and I wanted to get that deepburgundy richness. They experimentedwith different kinds of inks, magic mark-er inks of red, blue, and black, trying toget the color. It was very diff icult .CL: What is the cost of your drum set?NP: I don't th ink about it . I 've neverfigured it out. I didn' t buy it all at once.I've just never thought about it.CI: Do you enjoy the hectic scheduleyou keep on the road?NP: To me, it 's just the musician's nat-ural environment. I won't say that it 's al-ways wonderful, but it 's not always aw-ful either. As with anything else, I th inkit 's a more extreme way of life. The re-wards are higher, but the negative sidesare that much more negative. I th ink thatrule of polarity follows almost everywalk of life. The greater the fulfi l lmentthat you're looking for, the greater theagony you'l l face.CI: During your sound check, you notonly use the opportunity to get the prop-er sound, but also as a chance to warmup and practice a bit.NP: Well, sound check is a nice time topractice and t ry new ideas, becausethere's no pressure. If you do it wrong itdoesn't matter. And I 'm a bit on the ad-venturous side live, too. I ' l l try some-thing out. I ' l l take a chance. Most of thetime I'm playing above my ability, so I 'mtaking a risk. I t h i nk everyday is really apractice. We play so much and playingwithin a framework of music every nightyou have enough familiarity to feel com-fortable to exper iment . If the song startsto grow a bit stale I find one nice l i t t l e f i l lwhich wil l refresh the whole song.CI: Refresh it for the rest of the groupas well.NP: Sure for all of us. We all put in al i t t le something, a l i t t l e spice. The au-dience would probably never notice, butit just has to be a l i t t le something thatsparks it for us. And for me the wholesong will lead up to that from then on andthe song will never be dul l .CI: How did you become involved withRush?NP: The usual chain of circumstancesand accidents. I came from a city that 'sabout 60 or 70 miles from Toronto. A fewmusicians from my area had migrated toToronto and were working with bandsaround there when they recommendedme as someone of suitable style. I guessthey tried a few drummers, but we justclicked on both sides. There was a strongmusical empathy right away wi th newideas they were working on and things I

had as musical ideas. Also, outside ofmusic we have a lot of things in common.CI: Where has this tour taken you?NP: Well, this isn't really much of atour. By our terms, most of our tours last10 months or so. This one is only 3 or 4weeks. This is just a warm up as far aswe're concerned. We've been off acouple of months. We took two weeks ofholidays and then spent six weeks re-hearsing and writing new material. Afterthat kind of break, we just wanted to getourselves out on stage. That's the onlyplace where you really get yourself intoshape. Rehearsals wi l l keep you playingwell and you'll remember all your ideasand learn your songs and stuff, but as faras the physical part of i t , the feeling ofbeing on top of your playing, you've gotto have the road for that .CI: This is a warm up for what?NP: The studio.CI: At what studio wil l you record?NP: We will be going to Les Studiowhich is in Montreal . We'll record thereand mix at Trident in London.CI: When the members of Rush arecomposing a piece of music, is the struc-ture determined by the feedback you re-ceive from one another?NP: Yes, to a large extent. It dependsreally on what we're coming at it with.Often times. Alex and Getty wi l l have amus ica l idea , maybe i n d i v i d u a l l y .They'll bring it into the studio and we'llbounce it off one another, see what welike about it , see if we find it exci t ing asan idea and then we get a verbal idea ofwhat the mood of it is. What the settingwould be. If I have a lyrical idea thatwe're trying to find music for, we discussthe type of mood we are trying to createmusical ly. What sort of compositionalski l ls I guess we' l l bring to bear on thatemotionally. The three of us try to estab-lish the same feeling for what the songshould be. Then you bring the technicalski l ls in to try to interpret that properly,and achieve what you thought it would.CI: Your role as a lyricist has drawnwide acclaim. How did you develop thatparticular talent?NP: Well , that 's really hard to put intofocus. I came into it by default, just be-cause the other two guys didn' t want towrite lyrics. I 've always liked words.I've always l iked reading so I had a go ati t . I l ike doing i t . When I 'm doing it , I tryto do the best I can. I t ' s pretty second-ary. I don't put that much importance onit. A lot of times you just th ink of a lyr-ical idea as a good musical vehicle. I ' l lth ink up an image, or I ' l l hear about acer ta in me t apho r t h a t ' s r ea l l y p i c tu r -esque. A good verbal image is a reallygood musical st imulus. If I come up witha really good picture lyr ica l ly , I can takeit to the other two guys and automatical-ly express to them a musical approach.

CI: The tune "Trees" from your Hemi-spheres album comes to my mind as youspeak.NP: Lyrically, that 's a piece of dogge-rel. I certainly wouldn't be proud of thewriting skil l of that. What I would beproud of in that is taking a pure idea andcreating an image for it. I was very proudof what I achieved in that sense. Al-though on the ski l l side of i t , it 's zero. Iwrote "Trees" in about five minutes. It'ssimple rhyming and phrasing, but it illus-trates a point so clearly. I wish I could dothat all of the t ime.CI: Did that pa r t i cu la r song's lyr icscover a deeper social message?NP: No, it was just a flash. I was work-ing on an entirely different thing when Isaw a cartoon picture of these trees car-rying on like fools. I thought. "What iftrees acted like people?" So, I saw it as acartoon really, and wrote it that way. Ithink that 's the image that it conjures upto a listener or a reader. A very simplestatement.CI: Do all of your lyrics follow thatway of thinking, or have you expressed amore philosophical view in other songsthat you have written?NP Usually, I just want to create a nicepicture, or it might have a musical justifi-cation that goes beyond the lyrics. I justtry to make the lyrics a good part of themusic. Many t imes there's somethingstrong that I 'm trying to say, I look for anice way to say it musically. The sim-p l i c i t y of the t e c hn i q u e in "Trees"doesn't really matter to me. It can be thesame way in music. We can write a reallysimple piece of music, and it will feelgreat. The technical side is just not rele-vant. Especially from a listening point ofview. When I 'm listening to other peopleI 'm not l is tening to how hard their musicis to play, I listen to how good the musicis to listen to.CI: When you listen to another drum-mer, what do you listen for?NP: I listen for what they have. There'sa lot of different kinds of drumming thatturn me on. I t could be a really simplething, and I don't th ink that my stylereally reflects my taste. There are a lot ofdrummers that I like who play nothingthe way I do. There's a band called ThePolice and their drummer plays with sim-plici ty, but with such gusto. It 's great.He just has a new approach.CI: Who are some of your favor i tedrummers?NP: I have a lot. Bil l Bruford is one ofmy favorite drummers. I admire him fora whole variety of reasons. I like thestuff he plays, and the way he plays it. Ilike the music he plays within all thebands he's been in. There were a lot ofdrummers that at different stages of myabi l i ty , I 've looked up to. Starting wayback with Keith Moon. He was one of

my favorite mentors. It's hard to decidewhat drummers taught you what things.Certainly Moon gave me a new idea ofthe freedom and that there was no needto be a fundamentalist. I really l iked hisapproach to putting crash cymbals in themiddle of a roll. Then I got into a moredisciplined style later on as I gained alittle more understanding on the techni-cal side. People like Carl Palmer, PhilCollins, Michael Giles the first drummerfrom King Crimson, and of course Bill,were all influences. There's a guy namedKevin Ellman who played with ToddRundgren's Utopia for a while. I don'tknow what happened to him. He was thefirst guy I heard lean into the concerttoms. Nicky Mason from Pink Floyd hasa different style. Very simplistic yet ultratasteful. Always the right thing in theright place. I heard concert toms fromMason first, then I heard Kevin Ellmanwho put all his arms into i t . You learn somany things here and there. There are alot of drummers we work with, TommyAldridge from the Pat Travers Band is avery good drummer. I should keep a listof all the drummers that I admire.CI: Do you follow any of the jazzdrummers?NP: I've found it easier to relate to theso called fusion actually. I like it if it hassome rock in it. Weather Report's HeavyWeather I think was one of the best jazzalbums in a long time. Usually, just tech-nical virtuosity leaves me completely un-moved, though academica l l y i t ' s in-spiring. But that band just moved me inevery way. They were exciting, and pro-ficient musicians. Their songs were real-ly nice to listen to. They were an impor-tant band, and had a great influence onmy thinking.CI: What drew you towards drums?

Photo by Karen Larcombe

NP: Just a chain of circumstances. I'dlike to make up a nice story about how itall happened. I just used to bang aroundthe house on things, and pick up chopsticks and play on my sister's play pen.For my thirteenth birthday my parentspaid for drum lessons. I had had pianolessons a few years before tha t andwasn't really that interested. But withthe drums, somehow I was interested.When it got to the point of being boredwith lessons, I wasn't bored with play-ing. It was something I wanted to doeveryday. So it was no sacrifice. Noagony at all. It was pure pleasure. I'dcome home everyday from school andplay along with the radio.CI: Who was your first drum teacher?NP: I took lessons for a short period oftime, about a year and a half. His namewas Paul , I can ' t r emember h i s lastname. He turned me in a lot of good di-rections, and gave me a lot of encourage-ment. I ' l l never forget him tell ing me thatout of all his students there were onlytwo that he thought would be drummers.I was one of them. That was the first en-couragement I had which was very im-portant to me. For somebody to say toyou, you can do i t . And then he got intoshowing me what was hard to do. Al-though I wasn't capable of playing thosethings at the time, he was showing medifficult rudimental things, and flashyth ings . Double hand cross-overs andsuch. So he gave me the challenge. Andeven after I stopped taking lessons thosethings stayed in my mind, and I workedon them. And finally I learned how to doa double hand cross-over. I rememberthinking how proud I would be if myteacher could see it.CI: Did you study percussion furtherwith other instructors?

NP: Well, it 's relative. I think of myselfstill as a student. All the time I've beenplaying I've listened to other drummers,and learned an awful lot. I 'm still learn-ing. We're all just beginners. I really likethat Lol Creme and Kevin Godly al-bum. The L thing on their album standsfor "learner's permit" in England. Andthat album is so far above what every-body else is doing, yet they're still learn-ing. I really admire them.CI: When you were coming up, did youset your sights on any particular goals?NP: My goals were really very modestat the time. I would get in a band and thebig dream was to play in a high school.U l t ima t e l y , every c i t y has the placethat's the "in" spot where all the hip lo-cal bands play. I used to dream aboutplaying those places. I never thought big-ger than that. For every set of goalsachieved, new ones come along to re-place them. After I would achieve onegoal it would mean nothing. There's ahall in Toronto called Massey Hall whichis a 4,000 seat hall . I used to think to playthere would be the ult imate. But thenyou get there and worry about otherthings. When we finally got to play therewe were about to make an album, andthought about that.CI: Your mind was a step ahead ofwhat you were doing at the present.NP: Yes. I think it's human nature, notto be satisfied with what you were origi-nally dreaming of. Whatever you weredreaming of, if you achieve it, it meansnothing anymore. You've got to havesomething to replace it.CI: Describe your feelings, walking onstage and looking at an audience of35,000 screaming fans.NP: Any real person, will not be movedby 35,000 people applauding him. If I goon in front of 35,000 people and playreally well, then I feel satisfied when Icome off the stage. I 'm happy becausethose 35,000 people were exci ted . Ifwe're in front of a huge crowd and I havea bad night, I s t i l l can't help being de-pressed. If I come off stage not havingplayed well, I don't feel good. I don't seewhy I should change that. Adulationmeans nothing without self respect.CI: You feel you must satisfy yourselffirst.NP: I never met a serious musicianwho wasn't his own worst critic. I canwalk off stage and people will havethought I played well, and it might haveeven sounded good on tape, but I stillknow I didn't play it the way it shouldbe. Nothing will change that.CI: Do you feel there are certain thingsthat contribute to a particularly good orbad night?NP: I don't think there is anything mys-tical about it at all. I just think it's a mat-ter of polarity. I go looking for a lot of

parallels. I find it in that, because certainnights it is so magical, and the wholeband feels so good about how theyplayed. The audience was so receptiveand there's feedback going back andforth, and good feelings generated by theshow. That has to be the ideal. That par-ticular show might happen 5 or 6 timesout of the whole 200 show tour. But thatis the ideal show. Every other show hasto be measured on those standards. Ouraverage is good. We never do a bad showany more. We have a level where we'realways good. Even if we're bad the showwill be good. Somerset Maugham I be-lieve said, "A mediocre person is alwaysat his best." And that's true. If you playreally great one night, you're not goingto be great every night. As far as my ex-periences go anyway, I've never knownany musician that was. I'm not. Somenights I'm good and some nights I'm notgood. Some nights I think I stink. I thinkit's just a matter of knowing that youhave an honest appraisal of what yourability should be, and know how wellyou've lived up to it. To me, there's nomystery about that at all. You know in-side.CI: What type sticks do you use?NP: I use light sticks generally. I'veused butt end for as long as I can remem-ber. It gives me all the impact I need.When I'm doing anything delicate, I playmatched grip with the bead end of thesticks.CI: So you use both matched and tradi-tional grips depending on the feeling ofthe music.NP: Yes, both. I go back to the conven-tional grip when I have to do anythingrudimentary because that's the way Ilearned it. It's not the best way. For any-body else learning I wouldn ' t advisethat. I've seen a lot of drummers whocould play a beautiful pressed roll withmatched grip.CI: Why do you tape the top shaft ofthe bass drum beater so heavily?NP: That's an interesting trick that oth-er drummers should know about. I breaka lot of beaters off at the head, becausethe whole weight of my leg goes into mypedals. And I always break them wherethe felt part of the beater meets the shaft.They break right at the shaft, and thenthe shaft goes through the head. If youput that roll of tape on there you'll neverbreak your drumhead. In fact I can stillget through half a song if I have to, untilthe beater can be changed. The worstthing that could happen in a show wouldbe for your bass drum to break. Any-thing else could be changed or fixed orre-rigged somehow. But, if you break abass drum head the show stops. We oncehad to stop in the middle of filming DonKirshner's "Rock Concert" because Ibroke a bass drum. So we stopped andfixed it. That's all you can do. It doesn't

Photo by Karen Larcombe

happen anymore, because of that ideaand because Larry keeps an eye on theheads and changes them.CI: Who mikes your drums?NP: Our sound man lan chooses themikes, and positions them.CI: You have your own monitor mixduring live performances, correct?NP: Yes, Larry mixes that. That's real-ly just my drums in a separate mix, be-cause we have front monitors.CI: Are the monitors on your left andright side just feeding you the drums?NP: Yes. All I hear is myself comingfrom those monitor. The front monitorsgive me all synthesizers and vocals, andwhen it comes to guitar, and bass they'reright beside me. There are only two oth-er guys, I'm fortunate in that respect, soI don't need them in my monitors. I havedirect instruments to my ears which tome is the best. I'd rather have that thanto fool around with the monitors. Andthe stuff the other guys need in theirmonitors I get indirectly, because it'spointing at them, so I also hear it. I knowa lot of drummers who prefer to have thewhole mix in their monitors, and in somecases need the whole mix in their mon-itors.CI: Have you ever worn earphoneswhile playing live?NP: No, not really, they fall off. I evenhad a lot of trouble in the studio keepingthem on. I went through all kinds ofweird arrangements, getting the cord outof my way. It's just not worth it, I like tohear the natural sound.CI: What are your thoughts on tuning?NP: Concert toms are pretty well self-explanatory. I just know the note I wantto achieve and tighten them up.CI: Do you use a pitch pipe, get thenote from the keyboard or just hum thenote you're after?NP: I 've been using the same sizedrums for several years, and I just knowwhat note that drum should produce.When you combine a certain type ofhead with a certain size drum I believethere is an optimum note, which will giveyou the most projection and the greatestamount of sustain. Wi th the concerttoms I just go for the note. I have a men-tal scale in my head. I know what thosenotes should be. By now it's instinctive.With the closed toms, I start with thebottom heads. I'll tune the bottom headsto the note that drum should produce,and then tune the top head to the bottom.CI: How often do you change theheads on your drums?NP: Concert tom heads sound goodwhen they're brand new, so they getchanged a bit differently. They lastthrough a month of serious road work.The Evans Mirror Heads are used on thetom toms and take a while to warm up. Ittakes a week to break them in. I don'tchange those much more than every six

weeks or so. They do start to lose theirsound after a while. You start to feelthey're just not putting out the note theyshould be. Then you say, "I hate to do itbut let's change the heads." I like BlackDots when they're brand new. I used touse those on my snare, and the ClearDots also sound good when they ' r ebrand new. But the Evans heads don't. Ittakes awhile. I've gone through agonieswith snare drums. I guess most drum-mers do. I had an awful time, becausethere was a snare sound in my mind thatI wanted to achieve. I went through allkinds of metal snares. And I st i l l wasn'tsatisfied. It wasn't the sound I was after.Then my drum roadie phoned me aboutthis wooden Slingerland snare. It wassecond hand. Sixty dollars. I tried it outand it was the one. Every other snareI 've tried chokes somewhere . E i t h e rvery quietly, or if you hit it too hard itchokes. This one never chokes. You canplay it very delicately, or you can poundit to death. It always produces a veryclean, very crisp sound. It has a lot ofpower, which I didn't expect from awooden snare drum. It's a really strongdrum. I tried other types of woodensnare drums. I tried the top of the lineSlingerland snare drum. This one was aSlingerland but very inexpensive. I'vetried other wooden snares, but this wasthe one, there's no other snare drum thatwill replace it for me.CI: What has been done to the inside ofyour drum shells?NP: Al l of the drums wi th the ex-ception of the snare have a thin layer offiberglass. It doesn't destroy the woodsound. It just seems to even out the over-tones a bit, so you don't get crazy ringscoming out of certain areas of the drums.You don't get too much sound absorp-tion from the wood. Each drum producesthe pure note it was made to produce asfar as I'm concerned. There's no inter-ference with that ei ther in the open tomsor the closed toms. The note is very pureand easy to achieve. I can tune thedrums and when I get them to the rightnote I know the sound wil l be proper.

PAUL MOTIAN:Drawing from Tradition

Story and photos by Scott Kevin Fish

In preparation for my interview with Paul Motian, I listenedto recordings he has made, and read as much material as I couldfind about him. Throughout these record reviews, concert re-views, critiques and analyses, the accolades were many. Onewriter said, "Paul Motian can turn a set of drums into an or-chestra without overshadowing his fellow players." Anothercritic wrote, "To him, percussion is music at every level and hecould never be accused of playing anything for superficial ef-fect."

Paul Motian's professional career began around 1956 in NewYork. Since then, Mr. Motian has played and/or recorded withsome of the greatest musicians in jazz including Bill Evans,Keith Jarrett, Oscar Pettiford, Art Farmer, Mose Allison, The-lonious Monk, Tony Scott, Stan Getz, Lee Konitz, Lennie Tris-tano. The Jazz Composers Orchestra, Charles Lloyd and DonCherry.

In 1972, Paul, as a leader, released his first album, Concep-tion Vessel on ECM records. Two other albums have been re-leased since. Tribute in 1975, and most recently Dance releasedin 1978.

I met Paul Motian at his apartment in Manhattan one after-noon. He answered the door dressed in army pants, Orientalshirt, and knitted cap. He is not a tall man, but Paul has a strik-ing presence, especially in his dark brown eyes that have anobservant quality.

The apartment was decorated with gongs, bells, maraccas,plants, a piano, and a black five-piece drum set. "Almost every-one in the building is a musician," Paul explained. The sound ofa tenor sax seeped into the hallway. "Once I was in the elevatorand a woman asked, 'Is that you playing the drums?' I said yesand told her if it was bothering her I'd try to keep it down. 'Ohno,' she said. 'I like it! It sounds very good.'

"I started playing when I was about 13, in Providence, RhodeIsland," he began, puffing on a cigarette. "I was born in Phila-delphia, but I grew up in Rhode Island. There was a guy whoplayed drums a few blocks away from my house. When hewould play you could hear it in the street. I was fascinated with

it. He played in a Gene Krupa bag. I use to go over there andlisten to him every once in awhile. I started fooling around athome with some wooden sticks, and finally he gave me a coupleof lessons.

"After that I studied reading and syncopation with EmilioRagosta and George Gear in Providence. George Gear use to befriendly with George L. Stone from Boston. I played with thehigh school band. I might have played a couple of dances andclubs with musicians from that band." Motian thought in re-sponse to a question I'd asked about how many gigs he playedin his hometown. There weren't any gigs to speak of, and Mo-tian could only explain it by saying, "It just didn't happen."

"Most of my career just sort of happened," he told me."People ask, 'You mean you always played the drums?' That'strue. I've always played the drums. I've never wanted to doanything else. It's always been there, as sort of a natural thing. Ijust never thought about it that much. It was just something thatI did.

"I heard a lot of music when I was a kid. My parents wereborn in Turkey. They were Armenian and they used to play a lotof Turkish music and some Armenian music. I remember mymother telling me that when I was around two years old, I wasalways dancing to this music. My parents would say, 'Gee.Maybe he's going to get into music some way.'

When the Korean War broke out, Paul enlisted in the Navy."All my friends were being drafted in the Army and comingback frostbitten. That's why I went into the Navy. Somebodytold me about the Navy School of Music so I thought I would doit that way. I was stationed in Brooklyn, living off the base.When I got out of the Navy, I moved into Manhattan. I studiedwith Billy Gladstone, and then I went to the Manhattan Schoolof Music for awhile and studied timpani with Alfred Friese andFred Albright.

"That's when I started playing around," Motian continued."The professional part of my career didn't start unti l I was 24 or25 years old, around 1955 or '56. I use to carry my drums allover the city, man. I use to take them everywhere." By the time

Paul Motian got on the New York scene, the musical mecca ofthe 52nd St. days had all but ended. Charlie Parker died in 1955and it was symbolically the end of an era.

"I'm sorry I missed that," Paul said. "One of my favoritedrummers was Sid Catlett. I never saw him play. The personthat I did see play a lot and who was a major influence on mewas Kenny Clarke. He was in New York at that t ime. MaxRoach was also an influence. I first heard his stuff when I was ateenager. I liked it a lot.

"I remember one t ime going to a place where TheloniousMonk was playing. The drummer hadn't shown up and the pro-moter knew I played the drums. He said, 'Hey man. Go getyour drums and you can play with Thelonious!' I ran as fast as Icould all the way home, got the drums and played that nightwith Thelonious. That was a thri l l for me. Later on, I workedwith him for a week in Boston.

"One time I was playing with Monk and I think the tempopicked up a l i t t le bi t . At the end of the set I went over to him andsaid I was sorry; that I might have rushed a l i t t l e bit on thatnumber. Monk said, 'Well, if I hit you in the side of the headyou won't rush!' Paul broke up laughing. "That's great ad-vice," he said. "I've never rushed after that."

Motian expressed sincere gratitude to the forces that be forthe opportunities that he's had in his musical career. Aside fromMonk, there was a period when Paul Motian played drums withthe Oscar Pettiford quintet and big band; and he has also beenfortunate to have worked with several other premier jazz bass-ists including Scott LaFaro, Charlie Haden and Gary Peacock.

Paul sat back in an easy chair. He'd run out of fi l ter cigarettesand sat smoking one of my non-filters through a cigarette hold-er. I asked him if he could recall any pertinent discussions hemay have had with some of those bass players that would inter-est other drummers.

"I'm trying to th ink back about Scott LaFaro and BillEvans," he said. "I know that we always made suggestions toeach other about different things. I know there were really mu-sical questions and discussions. I remember talking with Bil l

one t ime, thinking of different things. What if you had to play atune that could take five, ten or fifteen minutes, and you had toplay every quarter note in that tune differently? It's just a sug-gestion or an idea to make you aware of the music. If you'rethinking about things like that, think what could happen!

"Bill and I use to play gigs together and we lived in the samebuilding. After Bill had been with Miles Davis, he had his owntrio and was playing Midtown, I th ink at Basin St. His drummercouldn't make it one night so Bil l called me. Scott LaFaro wasplaying around the corner and he came by and sat in. It seemedlike that was it! Bill liked it a lot and we just kept it together forabout two years."

I questioned Paul about one writer's opinion that he and ScottLaFaro were responsible for the "freeing up" of Bill Evans.

"I th ink that might have been more mutual," he answered."Nobody was playing bass l ike Scott. Bass players played rootsof chords all the time and this was the first t ime the bass wasplaying with the pianist. I guess that freed Bil l . I played what Iheard and tried to fit in with them. I never thought of playingthat way," Motian emphasized. "I've never pre-thought some-thing. It seems like it's always been something that's happenedthrough my involvement in the music and the musicians. I thinkit was something that just happened.

"I believe that 'time' is always there. I don't mean a particu-lar pulse, but the time itself. It 's all there somehow like a hugesign that's up there and it says time. It 's there and you can playall around it. I guess playing with Bill Evans was a freeing up forme too.

"We had reached a really nice point just before Scott died. Iremember the gig at the Village Vanguard after we made thoserecordings (Milestone 47002) and we were all real happy. Itseemed that we had musically progressed to a really nice pointand now we could really get going. A few weeks later, Scott waskilled."

Motian stayed with Bil l Evans from 1964-65. "It got to apoint where it didn't seem like it was me anymore," he said. "Ididn't seem part of it . I wanted to go in other directions becausethere was a lot of music happening in New York at that time.

"I played with Carla and Paul Bley, Albert Ayler, and JohnGilmore. It 's better now in New York, but I think that 1965 wasone of the good periods in New York. That was around the timethe Jazz Composers Guild was organized. I was playing a lotbut I wasn't making any money. I used to work for two dollars anight. That was i t . That went on for a couple of years, but Imanaged.

"I took a couple of commercial gigs. I was working an Israeliclub playing floor shows. Then I worked for awhile on the Eastside with a trio. I guess that's how I survived. There are somany clubs now and so much happening. The loft scene and allthat. At those times there were things happening in lofts butthere was just no money in it. It wasn't publicized as much, Ith ink .

"Shortly after that, I got hooked up with Keith Jarrett. I methim at a gig he was playing with Tony Scott and he soundedgreat to me. He was about 19 or 20 then. Later on he called meand Charlie Haden and we did Keith's first trio album. That wasin 1967 and later on I played with Keith in Charles Lloyd'sband.

"We did a fantastic tour of Asia. That was a great experience.Then I went with Arlo Guthrie for awhile. Arlo's bass playerknew of me through my work with Bill Evans so he suggestedme. Arlo had a hit record with Alice's Restaurant and wasabout to start touring. I enjoyed that," Paul said. "It wasn't abig musical experience but it was fun. I can play country/west-ern music: keep time with brushes and have fun. I did a coupleof tours with Arlo and part of that would be the WoodstockFestival.

"Afterwards it was mostly Keith. A trio first and then DeweyRedman joined around 1972." We spoke about some of the mis-cellaneous records that Paul had played on and two that he was

most proud of were Charlie Haden's Liberation Music Orches-tra, (both Motian and Andrew Cyrille are credited with playingpercussion instruments). When asked what he specificallyplayed on that LP, Motian said he played on all of the tracksexcept "Circus '68 "69" on which Andrew Cyrille is per-cussionist, and the monumental project Escalator Over the Hillby Carla Bley.

When Paul Motian started leading his own group, he ran intoa few problems. He found that he had to have a knowledge ofmusic "business" but more than that he became heavily in-volved with musical composition. "I've been studying pianoand composition," he told me. "I think that's really importantfor drummers. All drummers should play a lit t le bit of piano. Ifthey've got something against the piano, then study vibraphoneor xylophone or buy a wooden flute, man!

"My composition stuff is all recent. I never even dreamedthat I could do that kind of thing," Motian said with an air ofpride. "When I got offered to do my first record for ECM, I puttogether some music and found out that I could do it. Plus, I hadsome good musicians to help. That's what I 'm working on now.I would like to get that together. That's very important. I mean,it took me a year just to get a book together for my band!"

I was interested in knowing how Motian went from the initialcomposing of a piece to working it out with his band, to per-forming it. Paul explained, "I'll work it out myself first. When itseems satisfactory, then I ' l l write out parts and rehearse it.Maybe I ' l l get the saxophone to play the melody. If it doesn'tsound right, I may make a few changes. I ' l l do the same thingwith the bass, and then rehearse the trio. The song grows fromthere. (

"I would really l ike to get away from the normal format ofchart, solo, choruses and chart again. I don't really like that,"Motian said. "But, once I've written a tune and worked it withthe band I don't play it on the piano after that. Right now, Ihave maybe seven or eight things that I'm working on that I 'mnot satisfied with. I may scrap it all, I don't know."

Motian was kind enough to oblige my request that he play thepiano. The tune was reminiscent of his writing on the ByeablueKeith Jarrett album. "That's it," Paul said when he had fin-ished. "I'll give that to Keith and he'll play the shit out of it." Itold him that one of the qualities I admired most in his composi-tions was his use of space. Other than the melody line it is oftendifficult to separate what is spontaneous and what is arranged.

"Last year a woman in Canada wrote me and said she likedmy albums because she didn't hear any aggression in them. Idon't know if that 's good, though," Paul laughed. "I can re-member being angry and playing. Usually, the melody andsome harmonies are written. I like to keep it spontaneous sothat I can make changes. So that I can play a piece of music onetime and play it differently another time. The melody will be thesame, but the playing part can change."

Because of the time spent on composing and leading his band,Motian has no desire or time to teach. He has done clinics andformed definite ideas about how he would teach drums. "I al-ways had a thing about that," he said. "If I ever teach, I'm notgoing to teach on a practice pad. To me, that doesn't really havetoo much to do with the drumset. The drumset is your in-strument, not the practice pad!"

Motian recently toured Europe with his trio and told meabout a couple of weeks he spent teaching at a school in Den-mark. "I was there for two weeks with two, one hour classes aday. I took a private student everyday for a half hour lesson. Ihad to come up with something new each day and that was achallenge.

"The first day I had them tune the drums," Paul remem-bered. "There was a set of drums there that sounded terrible. Igot the idea to have each drummer tune them to whatever heheard. By the end of the two weeks that was the best soundingdrumset in that school," Paul beamed.

"Mostly, I talked about music and the musicality of thedrumset. What is the sound? People will listen to drummers andsometimes they don't listen to the right thing." Motian leanedforward in his chair. What is the sound of that drummer? Whatkind of sound is he getting? Each drummer has his own sound.

"All musicians should check out the tradition of their in-struments. There were so many really great drummers. I'd liketo bring that heart of drum playing back. People now don'tknow about Shadow Wilson, Denzil Best, Kenny Clarke, DaveTough, Chick Webb, J immy Crawford! And Baby Dodds! Somegreat drummers. Drummers today don't know about how orwhat they played," Paul said, shaking his head.

Motian explained that the styles of the really great drummerswould never be obsolete. "Their type of playing is connectedwith the way people are playing today. It really is. Whether it'sused or not is another story. But, I think there's a certain art toplaying the drums that is missing today."

When asked what he felt his function in a group was, Motianstated simply. "Adding to the music I love to play time," heelaborated. "It depends on what kind of music it is! I thinkthat's great. It 's a happy thing just to play time and having thatfeeling in your body, bringing it to other people."

"I don't know if that's contradictory to what I said earlierabout playing time. How can you listen to the Charlie ParkerQuartet with Max Roach and say that's not good or that's notfun? That's beautiful music!"

Would Motian agree that the best 'free' drummers were alsoexceptional timekeepers? "Well, that comes back to the tradi-tion of drums. I don't think a drummer or anyone else can juststart playing what's known as 'free'. Somebody said that theonly 'free' music is when you don't get paid. You can't just startplaying that way. It comes from a tradition and there's a lotinvolved there.

When asked whether he still practices, Motian replied, "I tryto play a l i t t le bit each day. Sometimes I make a mental noteand sometimes I ' l l even write down: 'Play at least ten minutes aday on the drum set.' I have to really feel like I want to do it. Idon't force myself. When I sit down and try to think aboutworking something out, I 'm never really happy. If I sit downand play the drums, like I 'm playing in front of people, I 'll getinto it more. Then I can play for awhile."

On the floor tom I noticed a piece of paper with triplet exer-cises written on it. Paul sat down at the kit, picked up the paperand started to play what was written. Then he stopped. "Thatsounded good this morning, but now it doesn't sound so good."He tossed the paper aside and went into a second solo to dem-onstrate the sound of his drums.

"This is an old Slingerland set," Paul explained. "I've had itfor years."

The snare was an old chrome Slingerland, the tom-toms were9X13 and 16X16. For a second mounted tom-tom, Motian hadan old wood 5X14 Ludwig snare with the strainer and snaresoff.

"I have another snare drum that I like a lot," Paul said. "It'sa deep wooden snare with ten lugs. I used that for a few yearsand then I switched to this metal one. I may go back to thewooden one."

"People ask me about my cymbals," Paul said as he tapped asizzle cymbal. "That's another thing that just sort of happened.Through the years you go through different cymbals until youget the sound that you l ike. I must have had my rivet cymbal for20 years. It's an old A. Zildjian."

The second ride on the left was an old K. Zildjian. "I've got aPaiste ripple cymbal on the bottom of the hi-hat, and a K. Zildji-an on top. I have a Paiste Chinese type cymbal that I use a lot.That's what I use pretty regularly now." Paul told me that thiswas the same set he'd used on his recordings and his pet drumseemed to be the 18" bass.

"I think it's deeper than most. This one gets a bigger soundthan a normal 18". I tune them unt i l it 's satisfactory to my ear.I ' l l tune them until it sounds good to me; until there's some kindof interval between the drums and it sounds pleasant to myears. But, I don't say I have to tune a fourth here and a thirdthere. I don't get into that. Sometimes I might as an ear trainingexercise, I'll play the drums and then go over to the piano to seewhat it actually is. But it's hard for me to find out because I likethe overtones in the drums. They hate me in recording studiosfor that. There's no mufflers on the drums. Everything is wideopen. It's loud and there's a lot of overtones. It's hard to tune tospecific notes because of that. Most of the time the studio engi-neer has me take off the head or put some damper on it, becauseit really raises havoc with their needles.

"I'm still not completely satisfied with recording," Motianadmitted. "ECM does a really fantastic job but I wonder if it'spossible to hear drums on a record the way I hear them whenI'm sitting behind them? In a hall with bad acoustics I can't playtoo loud or I ' l l wipe everybody else out."

Does he consider himself a loud drummer? "No," Motiansaid. "But I've had people tell me that I was too loud. Some-times it's interesting to hear other players in a bad hall. I learn alot. Once I went to a concert where the drummer was playingwell but you couldn't hear the piano. I kept thinking, 'I wish thedrummer would just stop for two measures.' He never did. Hejust played constantly and wiped out the piano. I don't wantpeople thinking that way about me."

Remo Ambassador heads are on all of Motian's drums excepton the snare which was calfskin. It isn't that he is so particularabout a specific head as he is, again, about the sound. "On thislast tour of Europe, Sonor Drums provided a set for me. I justtook my trap case and cymbals. The drums seemed good butwhat I didn't like about them was that they had clear plasticheads on them. That starts to mess with my sound. I changed acouple of heads and got a better sound.

"I don't l ike heads when they're real thick. I think plasticheads are made in three or four different thicknesses and eachcompany is a little different. I like the heads that are on mydrums now. It's surprising that the calfskin head seems to stayin tune. It's nice for brushes but the plastic heads are nice forbrushes, too. Those clear ones aren't very good though."

Besides his regular drum kit , Motian plays some of the mostinspiring percussion on various instruments. He is a master atusing mallets in addition to brushes and sticks on the drum kit.

"I've got a couple of boxes of percussion things I've collectedover the years that I take around with me," he said. "It's justlike colors to add to the music.

"I like the concept of Indian music," Paul said. "Where youhave an Indian playing an instrument like a violin or a sarot withthe tamboura and drum. I think there's a way of connecting thatwith what I 'm doing. You have a melody instrument, the tam-boura and a bass or a drum! You can do a lot in music with that.

"A lot of different music is coming together, which was inevi-table. I had an idea to play all kinds of music. I don't see whyyou have to be restricted. I'd like to play a piece by CharlesIves and then a standard. Then one of my compositions. Jazzfusion, music of the world like African, Indian, Asian, theMiddle Eastern, rock & roll, country and western, rhythm &blues, bring it all together!"

Despite critical acclaim for performing and recording, therole of bandleader has been an uphi l l climb for Motian. In spiteof the fact that he's still on the ascent, there is much more thana spark of optimism in his soul.

"Managers can't do anything with me because I don't com-mand $5,000 a performance and their commission isn't going tobe great. That's the reality of it," he said.

"My concerts have done very well. I've gotten very goodreviews. It bothers me that I'm not playing as much as I wouldlike to. I get calls for gigs with other people that I turn down. Sofar, it hasn't been too bad. We've done two European tours, afew concerts in New York, and a couple of workshops and col-lege concerts. Once I actually get to play," he smiled, "it's fan-tastic."

Photos by Robert Stilesby Harold Howland

Fred Begun is that rare sort of per-cussionist whose musicianship parallelsthat of a fine concert violinist. He pos-sesses the ability to translate into com-plete music the rough and primitive in-stincts of aggression which a less sensi-tive person may bring untempered tothat most easily abused of instruments,the drum. In the world of classical mu-sic, rich with tradition, where a player'scultivation of superb technique, tone.and historical understanding is by ne-cessity regarded as a given factor. Fredstands out as uniquely total masterof his instrument.

Born in Brooklyn on August 30. 1928.Fred moved with his family to Washing-ton. D.C. when he was eight years old.At age eleven he began his percussionstudies, to which he applied himself witheffort sufficient to gain his entrance tothe Juilliard School of Music in NewYork in 1946. For the next Jive years Fredstudied the timpani under the firm andartful hand of Saul Goodman, whose un-compromising musical approach he ab-sorbed completely. I he technical andaesthetic awareness which Fred gainedduring his studies under this Horowitz oftimpanists prepared him well for thesymphony orchestra and formed thebasis for his own personal and intenselymusical style.

One is impressed and enchanted im-mediately by Fred's big, clear sound andby his courtly demeanor onstage, wherehe makes graceful and musically ef-fective use of his body to enhance andpersonify every tonal and stylistic detailof his part. During the reading of a givencomposition one actually may imaginethat Fred is the pious and decorated bar-on of eighteenth-century Germany, orthe swashbuckling mounted general ofNapoleon's army. Fred once said, "Imime the music. When I play Don Juan,I identify with the lover."

The true romantic. Fred will alwaysoffer to a conductor or to a student atleast two ways in which to perform prac-tically any passage: an unbiased, "cor-rect" translation of the page, and a vi-tal, expansive interpretation which atonce pays deference to history and ex-plores the realm of inspiration.

HH: What motivated you to study mu-sic, and what was your early traininglike?FB: I started lessons when I was 11.The big attraction at that t ime was, ofcourse, jazz, and the drumset was theonly thing in the world. I hadn't hadmuch contact at all with symphonic mu-sic. In fact, I was totally unaware of it .

It all started because one day a kidbrought a pair of sticks and four or fivet in cans mounted on a board to school. Itwas pretty neat, and I asked him to makeme a set, which he did. I turned on theradio and played along, making quite aracket and driving my folks crazy. I fi-nally persuaded them to get me startedtaking lessons.

In those days the big thing the teacherlaid on the parents was, 'He doesn'thave to make a lot of noise, so get him alittle rubber practice pad.' As you know,that way the student learns how to playthe pad, not the drum. I finally got a realdrum set with a snare drum, a l i t t le Chi-nese tom-tom, a woodblock, and a bluel ight in the bass drum. It was one ofthose very early Baby Dodds-type out-fits. I didn' t have a hi-hat unti l later be-cause that didn't come with the set.

I started playing wi th l i t t le groups inschool. It was getting near the end ofhigh school, and even though I was doingwell on the legitimate studies, I readwell, and I did my rudiments, the thing Ireally wanted to do was play jazz. I hadto decide where I would attend college. Igot into a real subterfuge plan to con-vince my folks to let me try out torJuilliard. I wanted to go to Jui l l iard to benear 52nd Street. I made Juill iard, andstarted my studies with Saul Goodmanon timpani, which I had not played muchat all prior to that . I found it interesting,but the big thing was to try to get intosessions and sit in. Needless to say, Ididn't stop traffic on 52nd Street, muchto my dismay.

I was in about the tenth orchestra inschool, and it came time for us to playour first concert. The first thing I everplayed on timpani in a concert was theSchubert Unfinished. There was some-thing about the concert that I liked: the

public's response, a certain elegance tothe setting, something that appealed toan aesthetic that I hadn't really lookedat. From that point on, I started gettinginto the studies more ardently. Duringmy second year in school I decided that Iwas going to be the next great timpanistin the world. I 'm st i l l trying.HH: Was it the absence of improvisa-tion as a main feature that made classicalmusic easier to pursue than jazz?FB: Well , we do have to adhere to thewritten page when we play with an or-chestra, but there are areas of inter-pretation on timpani where you have achance to use a certain amount of artisticlicense. You're not necessarily changingnotes from what is written, but you havelatitude for a personal interpretation pro-vided it 's tasteful and doesn't get in theway. I was able to find out about thisfairly early on.HH: Does that freedom result simplyfrom the fact that, unlike the sectionstring player, the timpanist has his partall to himself?FB: Well , you are often part of a per-cussion section, even though your thingis usually individualized. In the classicliterature, you are alone, and wi th in theframework you can project the note acertain way. Tone, length, qual i ty , theenhancement of other sections of the or-chestra, those various details can makeyour interpretive role more interesting.HH: What criteria helped you to deter-mine when to alter slightly an older partwhich probably would have been writtendifferently had the composer had accessto more mechanically efficient timpani?FB: It depends on who's conductingand where you're playing, If it's a nerdof a conductor, all of the extra notes inthe world aren't going to help. If it 's abetter conductor, then I consult with himprior to a rehearsal as to what I have inmind, and if he has that in mind, fine.

I feel that there is validity in some ofthe notes that have filtered on throughthe ages, specifically through Toscanini.He added many interesting notes to theBeethoven symphonies.HH: Going back: Tell me somethingabout Goodman as a man, a player, ateacher, an inventor.

FRED BEGUN:Timpani Virtuoso

FB: Very interesting man. He is thesenior citizen of the timpani world, notonly in age, but also in terms of statureand of my own personal reverence. I feelthat he's one of the greatest natural per-formers in any area of music. Here's aman who can just walk up to the in-strument and play. It never seems to beany degree of trouble for him. He hasfantastic time, taste, tone-quality, and akind of joie de vivre that got to all of uswho had room for it. If you don't haveroom for joie de vivre, your playing is go-ing to be dead.HH: Did he have specific qualities,methods, or techniques as a teacher thatyou found particularly valuable?FB: The organization of techniquesthat he used in his lessons was somewhatscattered, and I'm not saying that he wasdisorganized. A lot of the things that Iwanted to get from him had to be ob-tained at the concert hall, however, notat the lesson. He would sometimes unin-tentionally do things differently in les-sons from the way he did them in per-

fo rmance . What I was i n t e r e s t e d inseeing was what he really did in theBrahms Fourth, why he made the endingof the Beethoven Ninth sound so great.This may not happen in a lesson setting,but it wil l in the fevered pitch of a per-formance.

When I started teaching I decided totry to show as faithfully as I could whatI do onstage. That's what it 's about. If aperson is taking the trouble to come andstudy with me, I feel that he should get ital l , choreography and everything.HH: You j o i n ed the N a t i o n a l Sym-phony Orche s t r a (NSO) r ight out ofschool. Tell me about that.FB: I graduated Jui l l ia rd in June 1951,and the opening in this orchestra cameabout. The summer before I was one ofthe t impani players in a performance ofthe Berlioz Requiem. Somebody spottedand remembered me, so I got called toaudition for Howard Mitche l l , who wasthen music director. He signed me to myfirst contract. I 've been here ever since.HH: With the NSO you've given theworld premiere performances of threet imp a n i concer t i . What can you sayabout these as compositions and aboutthe t impani as a solo instrument?FB: The timpani in a solo concerto set-ting can be very effective or very inef-fective. In the three works that I 'vedone, I 've seen i t go both ways and inbetween. The first and best of the three isthe piece that Robert Parris wrote for me(1958). He found a successful setting,and I feel that as far as interest is con-cerned, i t ' s a far better piece than eitherthe Jorge Sarmientos (1965) or the BlasAtehortua (1968).HH: It seems that so much percussion-centered music is written more wi th aneye towards liberating percussionistsfrom the back of the bus than towardscreating lasting works of art.FB: That's one of my objections to thepercussion ensemble l i terature in gener-al. Not that it 's all junk, but enough of itis to make it all seem l ike a circus t r ick .Here they are, the clowns are jumpingaround again. I don't find this very musi-cal, and I would say that most per-cussion ensemble music turns me off.HH: How did your book of e tudesevolve? How do you view it as composi-tion, and what are your aspirations as awriter?FB: The book came about sporadically,an exercise here, an exercise there, andin each piece I would try to th ink interms of a motive that I might develop.The pieces have some kind of form andlogic. It was not just technical histrion-ics, although some of it is quite diff icul t .It was my attempt to write music. I feelthat this is the approach that is missingfrom some of the material that we haveto work with. The technical vehicles thatwe practice are writ ten as exercises, not

as music, and consequently they areplayed that way. This is something thatwe can all th ink about in our daily prac-tice. Take, for example, those very firstcouple of exe r c i s e s in the Goodmanbook. You can make them sound like astring of notes, or you can make thosetwo pages sound highly musical. If youdo, you have a good start as to whatyou're going to do with the instrument.HH: Do you have o t h e r book splanned?FB: I have a couple of books goingaround in my head. It 's going to be veryhard to write a better beginning bookthan the Goodman. Therefore, I

wouldn't even th ink in those terms. Imight th ink of another set of approachesto complement that book, but I feel thatGoodman is the prime method, that i tsays it a l l . I can't envision my ever usinganother beginning book for my students.

As far as writing is concerned, I 'mmore involved now in the written wordthan in music.

I ' v e s t a r t ed a group of anecdotesabout the symphonic repertoire, my feel-ings about certain pieces. I 'm going to doabout fifty or seventy-five, and I've al-ready done work on Le Sucre du Prin-emps, Bartok's Concerto for Orchestra,and the Tchaikovsky Fourth. These arethoughts about a specific performance ora specific work through the years. I didone called Farewell to the GoodmanDrums when we sold his instruments.

I also want to write a good biographyof Saul Goodman. That is something I

can't think about too much currently be-cause of the research t ime involved. Butthe idea appeals to me, both from thestandpoint of his being a chronicle ofplaying in the twent ie th century and howhe evolved.HH: Returning to your role and orien-ta t ion as a teacher : You must haveyounger s tuden t s who, as you oncewere, are more interested in jazz, rock,or other forms than in classical music.How do you relate to and direct their val-ues?FB: Well, I stay with the drumset. Ican't consider myself a Steve Gadd, butI don't t h ink my head's back in 1940. Asfar as reconciling the pursuit of the stu-dent is concerned, we as players andteachers are more and more in a mul t ip lecapacity: you're not going to t ra in just atimpanist, a mallet player, a snare drum-mer, a drum set player. The demands aremuch greater all the t ime. The contem-porary player, if he is to be successful,not just monetarily but also in his role asa percussionist, must do it all .HH: Are you currently as interested injazz as you were before Juil l iard?HH: I can't say that I devote so manyhours each week to listening to recordsor radio programs, but if there's some-thing that I've been reading about or thatpeople have been talking about, I ' l l makeit a point to hear or see it or both.HH: Who are a few of your favoritejazz or rock drummers?FB: Well. I th ink that Steve Gadd isprobably one of the biggest talents thatI've heard, a fantastic player. I like Bil lyCobham and Ginger Baker. Buddy al-ways fascinates me. One of the mostt a s t e fu l p layers of a l l t ime is She l l yManne. There's another guy I ' l l neverforget, Gene Krupa. When I was a youngfledgling. Gene represented the epitomeof what a big-time drummer should be.There was a great mystique about him, acertain class, a certain elegance—he hadstyle, there's no doubt about it .HH: What long-range plan would yousuggest to the aspiring orchestral playerfor lea rn ing the reper to i re and con-fronting auditions?FB: There are resources for learningaudition techniques. Some people fromthe New York Philharmonic have adver-tised themselves as Audition Associates,and Artie Press in Boston as well, tocounsel players on auditioning. Now aperson can become an audition specialistthe way an applicant to a corporationwould go someplace to learn to write agood resume. This is all well and good,but it is liable to become a perverse ele-ment of our field if the player does notlearn to conduct himself onstage once hegets a job. It 's conceivably computer-foolproof to learn the techniques, strate-gic parts, and solos needed to give an aceaudition, but the player must make sure

that he's equipped also to perform aHaydn symphony tastefully. It's gratify-ing to know that this audition counselingexists, but I hope that the people who arerendering the service do it all the way sothat the applicant has the wherewithal todo what his credentials announce.

Regarding the repertoire. I devote thefirst extended period of time to Beetho-ven, then Brahms and Tchaikovsky. Inthe meantime. I deal with certain otheridiomatic styles such as a lighter Mozart,the relationship between Haydn and theBeethoven sound, and so on. In thesedifferent textures it's not all the sameforte. It seems that the average studenttoday is exposed to contemporary musicmore quickly than to the classic stan-dards, so I sometimes find it difficult totransmit the classical style.

When I was in school we didn't havecommunity youth orchestras or othergreat outlets of learning the repertoire. Iused to have to go out and play in theseSunday morning orchestras on the EastSide, l ike the Czechoslovakian SocietyOrchestra of America, with eleven and ahalf people in i t , and we'd saw through aBrahms symphony . People would besinging parts. You learn how to play themusic that way, because there's an awfullot that doesn't happen. I got to Juil l iardand had no real orchestral experience.Today the kids are learning the reper-toire in their youth orchestras, and it'swonderful.HM: Many American percussion stu-dents today take up the serious study ofclassical music about the same time youdid, late high school and college. Do youthink, given the competition out therenow and in the future, that's too late?FB: It depends on how early the playerreally gets started. I've had students sev-en and eight years old, and unless there'ssometh ing t r emendous ly compe l l ingabout them, nothing really happens for acouple of years. You're babysitting mostof the time. If I were to choose an aver-age good starting age, I would say elev-en.