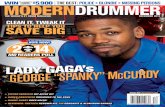

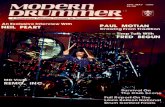

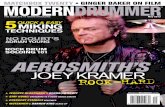

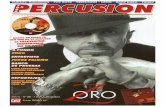

March 1998 - Modern Drummer Magazine

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

5 -

download

0

Transcript of March 1998 - Modern Drummer Magazine

A lot of musical trends have come andgone since Rod Morgenstein and his cohortsin the Dixie Dregs originated their own brandof southern-fried progressive rock. TodayMorgenstein's playing is as vital as ever, asseveral new and exciting projects prove.

Baseball, hot dogs, apple pie, and countrymusic: We're talking good ol' Americanfamily values, yessiree. Of course, beforelanding the gig with country star TimMcGraw, drummer Billy Mason put in somehard time at the FBI. And then there wasthat exotic dancer phase. Uh...perhaps weshould let him explain.

Vernel Fournier has made a career of swim-ming in those strange musical tributaries justoff of the mainstream. But examining hisresume—including his highly influential takeon Ahmad Jamal's Poinciana"—reveals adrummer of singular style and importance.

Experience is the wisest teacher. Just askEnrique Iglesias's Chuck Burgi, Boyz II Men'sFred Holliday, Buckshot LeFonque's RockyBryant, and Sawyer Brown's Joe Smyth.They've traveled all the miles, broken all thesticks—and eaten all the back-stage friedchicken it takes to learn what road life isreally all about. An exclusive MD report.

photo by Paul La Raia

by Robin Tolleson

by John M. Aldridge

by Rick Mattingly

by Lauren Vogel Weiss

52

74

92

102

ROD MORGENSTEIN

BILLY MASON

VERNEL FOURNIER

ON THE ROAD:THE LIFE OF A TOURING DRUMMER

Volume 22, Number 3 Cover photo by Paul La Raia

education

profiles

MD GIVEAWAY

equipment

news

departments

ln Session:Louie Bellson And Gregg Fieldby Robyn Flans

Finding The Grooveby John Riley

Study ln Rhythms, Part 1by Joe Morello

Creating Drum Partsby Brian Stephens

The Value Of Practicing Slowlyby John A. Dorr

The Perception Thingby D.C. Beemon

Making Waves:A Drummer's Life On Cruise Ships,Part 2by Rich Watson

The Great Drummers Of Jazz,A Timelineby Mark Griffith

Adam Cruzby Ken Ross and Victor Rendon

Win A $14,000 Prize PackageIncluding A Grover Pro Percussion Drumkit,

Zildjian Cymbals, Gibraltar Hardware,And Impact Cases

Or One Of 39 Other Great Prizes!

JC's Custom Drumsby Rick Van Horn

Zildjian ZBT And ZBT-Plus Seriesby Rick Mattingly

New Zildjian Professional Cymbalsby Rick Mattingly

Groove Juiceby Rick Van Horn

Alternate Mode drumKAT Turbo 4.0by Rich Watson

Dave Abbruzzese, Mick Fleetwood, Teenage Fanclub's Paul Quinn,Kevin Hayes of the Robert Cray Band, and David Sanborn'sJonathan Joseph, plus News

Montreal Drumfest '97

Carl Palmer and Dave Weckl

Led Zeppelin, Oregon, and Phish CDs, Carter Beauford video,Chuck Silverman Afro-Caribbean play-along book/cassette,and more

Including Vintage Showcase

IN THE STUDIO

JAZZ DRUMMERS' WORKSHOP

STRICTLY TECHNIQUE

ROCK PERSPECTIVES

TEACHERS' FORUM

FIRST PERSON

SHOW DRUMMERS' SEMINAR

BASICS

UP & COMING

ON THE MOVE

NEW AND NOTABLE

PRODUCT CLOSE-UP

ELECTRONIC REVIEW

UPDATE

INDUSTRY HAPPENINGS

EDITOR'S OVERVIEW

READERS' PLATFORM

ASK A PRO

IT'S QUESTIONABLE

MD's 20TH ANNUAL READERS POLL

CRITIQUE

DRUM MARKET

DRUMKIT OF THE MONTH

24

122

124

126

132

134

144

156

148

166

36

40

42

44

45

46

18

160

10

12

30

32

120

140

168

176

130

First Personhis month we're pleased to introduce another new departmentto the regular MD column roster, First Person.The idea for this new series came about after receiving

many articles from MD readers, relating their own personalexperiences on the job, at the audition, in the practice room, orwith the music business in general. Though some of this materialfell neatly into MD's Concepts department, the editorial slant ofmany of the articles simply didn't seem to fit well in that slot—orany other MD department for that matter. And so some of thearticles were returned to the authors, while others were held inthe hopes that we might ultimately find a place for them.

However, we were recently sorting through our inventory ofthese "personal experience" type articles, and began to wonder ifperhaps MD readers might get more out of them than we'd origi-nally thought. Would other drummers perhaps gain some valu-able insight from fellow players who experienced similar situa-tions? Might some of these articles offer inspiration to anotherdrummer struggling to make it? Could one drummer see a reflec-tion of himself through the experience of another and learn animportant lesson from it? Well, we figured we'd never reallyknow until we created a specific department for this type of arti-cle. Thus, the birth of First Person.

The kind of topics you'll be seeing in First Person? A nameplayer recalls meeting a drumming idol as a youngster, and thelong-lasting effect that this experience had on his career. Anotherlocal player speaks out on the trials and tribulations of workinghis way up the musical success ladder. A middle-aged beginneroffers his perspective on starting out in drumming late in life,while another reflects on his return to playing after being awayfrom the kit for many years. And in our opener this month, theauthor relates a humiliating audition experience that taught him alesson about preparation he's not likely to forget.

We're sure many of you out there have equally interesting sto-ries to tell, and we'd certainly like to hear them. Should youdecide to submit a manuscript, please keep it to five or six dou-ble-spaced, typewritten pages, and include a self-addressedstamped envelope. You may enclose a photo if you like, whichcould be used if space permits. Send your articles to ModernDrummer, c/o First Person Editor, 12 Old Bridge Road, CedarGrove, NJ 07009. By the way, if we decide to publish your story,we'll send you a check for $100 when it appears in the magazine.

The World's Most Widely Read Drum Magazine

EDITOR/PUBLISHER

ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER

MANAGING EDITOR

FEATURES EDITOR

ASSOCIATE EDITOR

ASSOCIATE EDITOR

EDITORIAL ASSISTANT

SENIOR ART DIRECTOR

ART DIRECTORASSISTANT ART DIRECTOR

ADMINISTRATIVE MANAGER

ADVERTISING DIRECTOR

ADVERTISING ASSISTANT

MARKETING ANDPUBLIC RELATIONS

WEB SITE DIRECTOR

OFFICE ASSISTANT

RONALD SPAGNARDI

ISABEL SPAGNARDI

RICK VAN HORN

WILLIAM F. MILLER

ADAM J. BUDOFSKY

RICH WATSON

SUZANNE HURRING

SCOTT G. BIENSTOCK

LORI SPAGNARDI

JOE WEISSENBURGER

TRACY A. KEARNS

BOB BERENSON

JOAN C. STICKEL

DIANA LITTLE

KEVIN W. KEARNS

ROSLYN MADIA

MODERN DRUMMER ADVISORY BOARD: Henry Adler,Kenny Aronoff, Louie Bellson, Bill Bruford, Harry Cangany, JimChapin, Dennis DeLucia, Les DeMerle, Len DiMuzio, CharlieDonnelly, Peter Erskine, Vic Firth, Bob Gatzen, Danny Gottlieb,Sonny Igoe, Jim Keltner, Peter Magadini, George Marsh, JoeMorello, Rod Morgenstein, Andy Newmark, Neil Peart, CharliePerry, John Santos, Ed Shaughnessy, Steve Smith, Ed Thigpen,Dave Weckl.

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS: Robyn Flans, Burt Korall,Rick Mattingly, Ken Micallef, Mark Parsons, Matt Peiken,Robin Tolleson, T. Brace Wittet.

MODERN DRUMMER magazine (ISSN 0194-4533) is pub-lished monthly by MODERN DRUMMER Publications, Inc.,12 Old Bridge Road. Cedar Grove, NJ 07009. PERIODICALSMAIL POSTAGE paid at Cedar Grove, NJ 07009 and at addi-tional mailing offices. Copyright 1998 by MODERN DRUM-MER Publications, Inc. All rights reserved. Reproductionwithout the permission of the publisher is prohibited.

EDITORIAL/ADVERTISING/ADMINISTRATIVEOFFICES: MODERN DRUMMER Publications, 12 OldBridge Road, Cedar Grove, NJ 07009. Tel: (973) 239-4140.Fax: (973) 239-7139. E-mail: [email protected].

MODERN DRUMMER ONLINE: www.moderndrummer.com

MODERN DRUMMER welcomes manuscripts and photo-graphic material, however, cannot assume responsibility forthem. Such items must be accompanied by a self-addressed,stamped envelope.

Printed in The United States

SUBSCRIPTIONS: US, Canada, and Mexico $34.97 per year;$56.97, two years. Other international $41.97 per year, $63.97,two years. Single copies $4.95.

SUBSCRIPTION CORRESPONDENCE: Modern Drummer,PO Box 480, Mt. Morris, IL 61054-0480. Change of address:Allow at least six weeks for a change. Please provide both oldand new address. Toll free tel: (800) 551-3786.

MUSIC DEALERS: Modern Drummer is available for resaleat bulk rates. Direct correspondence to Modern Drummer,Dealer Service, PO Box 389, Mt. Morris, IL 61054. Tel: (800)334-DRUM or (815) 734-1214.

INTERNATIONAL LICENSING REPRESENTATIVE:Robert Abramson & Associates, Inc. Libby Abramson,President, 720 Post Road, Scarsdale, NY 10583.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Modern Drummer,PO Box 480, Mt. Morris, IL 61054.

MEMBER: Magazine Publishers Of AmericaNational Association Of Music MerchantsAmerican Music ConferencePercussive Arts SocietyMusic Educators National ConferenceNational Drum AssociationPercussion Marketing CouncilMusic Magazine Publishers Association

T

Correspondence to MD's Readers' Platformmay be sent by mail:12 Old Bridge Road,

Cedar Grove, NJ 07009by fax: (973) 239-7139

by e-mail: [email protected]

MIKE PORTNOYThanks for such arevealing interviewwith Mike Portnoy inyour December '97issue. It's refreshingto experience thehumor, humanity,and candor of such atalented individual.During my short

three years as an MD subscriber, I haveseen a plethora of references made to the"less is more" mentality—along with manyincidents of "prog bashing"—in yourpages. I think William F. Miller pinpointedthe true source of these views with hiscomment to Mike: "A lot of the technical

things you play are out of reach for mostdrummers."

As a nation of progressive people, wehave pushed—and continue to push—theboundaries of sports, science, literature,and frequently, the arts. Have we nowdecided to limit our creativity to that ofsociety's dictates? Modern/progressivedrummers like Mike Portnoy give me hope.Let's not stunt the growth and expressive-ness of our passion. There is so much moreto learn and so much more opportunity togrow as musicians.

John WebbPortland, OR

The interview with Mike Portnoy was phe-nomenal. It addressed many importantissues, such as commercialism, technique,and odd times. Clearly Mike is one of thebest drummers in the industry today. Fromthe way he expressed himself in the article,he seems to be a class act, as well.

I am writing also because I would like tosee the comments attributed in the inter-view to Neil Peart clarified by Neil. In the

past, Neil has seemed to be a very intelli-gent musician. But if he really did state thatthe Working Man tribute was nothing but abunch of "bar-band musicians" trying toget money, then I may have been wrong inmy optimistic assumption.

Magna Carta is a music label whose firstpriority is not money, but is for the artistand for progressive music. And the "barband" musicians referred to are legends. Iam sure most of them were as disappointedas Mike Portnoy was when they heardabout these alleged comments by Neil.

Perhaps in light of seeing his commentsbeing criticized, Neil will finally give cred-it to the great musicians on the album, whomade it out of reverence to one of thegreatest bands ever.

Ian Bradleyvia Internet

My subscription to your outstanding maga-zine started in October '97, and I have notbeen able to put it down since it startedcoming (except when I play)! One thingthat really got my attention was your

HOW TO REACH US

December '97 issue, in which you featuredMike Portnoy of Dream Theater, followedby an excellent article on the drummers onthe OzzFest '97 tour. The way youthoughtfully constructed that article showsthat metal drummers are not just "bash,boom monsters," but true musicians. I willcontinue to be a loyal subscriber for yearsto come!

Jay McDougaldLaurinburg, NC

Your article on Mike Portnoy was topshelf, with a great cover and great photos. Imust admit that your man Miller had meclose to indignant, making comments aboutMike's "extended fills." I really thoughtthat he was being a first-rate snob. Afterall, Mike makes a lot of fans and wins MDReaders Polls by being able to "play somuch." And not just anyone can admit toworking out double-bass patterns on thetoilet! Hey Mike, is that why you really sitso high?

I'm sending this note to express my thanksfor what I found to be the most wonderfuland concise tribute to Buddy Rich that Ihave ever read. [From The Past, December'97 MD] It says everything that needs to besaid about Buddy, in a most respectful andsuccinct manner. Mark Nardi should becommended for his words, and I commendthe MD editorial staff for recognizing apiece of such quality.

John Nasshan Jr.Las Vegas, NV

Mr. Nardi goes out of his way to talk aboutBuddy's "lightning speed, perfect wrists,and astounding technique." While everyone of those descriptions is accurate, Ibelieve most drummers would agree thatthe ability to groove or swing a band is farmore important than how technically profi-cient a drummer is. It's easy to see fromarticles like this why many drummers areso preoccupied with technical proficiencyover the ability to play rhythm and keeptime. Buddy Rich had a sense of rhythmthat can only be considered genius. Itwould be a crime to remember the greatest

drummer who ever lived only for oneaspect of his seemingly limitless abilities.

Rich ScannellaEwing, NJ

A NOTE FROM KENNYThanks to MD formy cover story inyour November '97issue. RickMattingly did anexcellent job, andAlex Solca tookgreat pictures.However, afterreviewing my owntour kit, I realized

that I inadvertently left out two items. I use aMeinl Drummer Tambourine as well as aMeinl RealPlayer steel cowbell as part of mylive setup. These are important effects for theFogerty gig, and I wanted to be sure that theywere mentioned.

Kenny AronoffBloomington, IN

A DECADE OF SILENCE

Brent JuveAustin, TX

Thanks to MD and Matt Peiken for finallygiving some more coverage to MarkZonder—probably the most talented andtasteful drummer in the progressive rockgenre! [In The Studio, November '97 MD]The music he's been creating with FatesWarning over the years has paved the wayfor the likes of Mike Portnoy and others,yet Mr. Zonder and Fates Warning arealways overlooked. Their latest release, APleasant Shade Of Gray, is arguably themost emotionally moving and ambitiouspiece of work we'll see in a long, longtime. Thanks so much!

Vance S. Westvia Internet

I would like to thank Paiste for having theguts to apologize in the November '97 MDfor the October '97 ad that depicted TommyLee romping in pig manure. While I valueour basic freedom of speech, it comes withthe responsibility to act in a respectable man-ner. Just because one makes millions of dol-lars is no reason to act like a child—or rather,like an idiot.

I applaud Paiste's ad apologizing for theirOffense. It really means a lot in this day andage, when too often people like to makeexcuses for why they should be allowed to dothe things they do.

Timothy J. Steggallvia Internet

Your October '97 issue was outstanding. Ireally liked the Paiste ad on page 45; my firstthought was, "How very brave of Paiste andhow typical of Tommy Lee." Then I receivedmy November issue, and lo and behold, onpage 26 Paiste goes belly up and apologizesto North America. (Jeez, just imagine thescope of that.) C'mon Paiste, it's only rock'n' roll, it's only drumming, and it's onlyTommy Lee.

Michael Boevia Internet

Further to the Editor's Overview in theNovember '97 issue, I am one of those whoenjoys reading the ads in each month's issue.They're a big part of why I subscribe toModern Drummer. How else would one staycurrent on what is available generally, andwith new innovations specifically? I certainlydon't have the time to hang around my localpercussion dealer.

Magazines such as GQ and Vogue have amuch higher advertising-to-editorial ratio thandoes Modern Drummer. But as fashion maga-zines this makes perfect sense. (I have neverpurchased GQ for the editorial content.) I agreethat plowing through a magazine with exces-sive ads and business reply cards can be cum-bersome. I canceled my subscription to SportsIllustrated for exactly this reason. However, Iview Modern Drummer as a trade journal, andas such, the ads only complement the excellentinterviews, reviews, and instruction containedin each issue. Keep up the good work!

Mark Blosilvia Internet

The remarks andperspectives thatMario Calire sharedin your October '97issue were veryinspiring and influ-ential. Although Ihave heard only alittle of theWallflowers' music

in the past, because of the interview, I willbe open to listening to a lot more.

Thanks for interviewing the newer drum-mers on the music scene. It's nice to seethat MD can change with the times. Thatdoesn't imply that MD should forget themasters of the present and past. But let'sgive the new drummers the same opportu-nities to reach that level of influence.

Dave MaccaroneRochester, New York

MARIO CALIRE

ADS IN MODERN DRUMMER

MARK ZONDER

Sure, there was some anger, sadness, sense of loss—even a bit of self-pity. Who wouldn't go through thatafter losing a gig, especially one as prized as the drumthrone in Pearl Jam? But now, three years later, DaveAbbruzzese says that in many ways he's better off forwhat happened. Anyhow, the drummer has little timethese days to dwell on it.

Topping the list of Dave's new interests are the rolesof drummer, producer, and one-man record label forhis new band, the Green Romance Orchestra, whichrecently released a home-spun debut, Play Parts I AndV. The mere fact that the CD is ln record stores is some-what of a triumph for Abbruzzese, who says the musicwas originally intended to be nothing more than spon-taneous expression between four Texas homeboys.

"The album was conceived and written as wetracked, and my role as producer was documentingour experience rather than overseeing some regiment-ed, sterile product," Abbruzzese says. "All we wantedwas a great experience, just sharing with each other."

While Abbruzzese didn't plan for anything beyondan extended jam session, he certainly isn't grumblingabout the return on his investment—more in heart andsoul than to his wallet. Abbruzzese says he's playingmusic again for the only reasons that matter to him.And maybe not entirely out of coincidence, his drum-ming has never been better. While Dave has alwayswoven his personality into his playing, you can hear aversatility and charisma on Play that speak of a rebornconfidence.

"I didn't approach my playing any differently than Idid with Pearl Jam," he insists. "I'm a melodic player,but the melodic aspect of this band is a little moreopen. I was really happy with how the drums came off, and Ithink some of that has to do with the time off. There's maybemore finesse, but just as much power as anything I did withPearl Jam."

Abbruzzese's days in Pearl Jam ended when his growingrenown within drumming circles didn't mesh with his band-mates' bent to control their image. Aftercommiserating with other drummerswho'd either quit or been canned frombig gigs, including Stan Lynch (Tom Petty'sHeartbreakers) and Grant Young (SoulAsylum), Abbruzzese went home—literallyand psychologically—to ground his emo-tions and get back in touch with the spiritfor music he thought he'd lost. Back inTexas, Dave and old friends Gary Muller,Paul Slavens, and Doug Neil wrote sevensongs in three days. The drummer thenspent the next year commuting betweenTexas and his home in Seattle, taking onthe role of executive producer and fund-ing the band's time in a Denton, Texasrecording studio.

Abbruzzese eventually formed Free Association Records toprint up an initial run of 20,000 CDs. At first he sold copies oneat a time to anyone who wanted them. Requests came in likean avalanche, though, and soon he found himself givingdiscs away rather than dealing with the bookkeeping effortsthat go along with cashing checks. Reviews have been so

positive that now the Green RomanceOrchestra is considering a nationaltour.

Regardless of a tour and any futurerecords, Abbruzzese says he owes alife-long debt to the other members ofGreen Romance Orchestra and to hisfans for the support that helped himclimb out of emotional turmoil. "PearlJam was the best—and the worst—thing that ever happened to me. Itwas a big life lesson, and a public les-son, that I'm still dealing with. The firstyear was incredibly difficult, the sec-ond was a little better, and the third?I'm just starting to be okay with it."

Matt Peiken

Jam

es B

land

"All we wanted with Green Romance Orchestra was a great experience, just sharing with each other.

"Are You With Me?"To watch Mick Fleetwood play a show isto watch a man who simply loves to per-form. For most of the gig fans can spotthat familiar wide-eyed, open-mouthed,hyper presence behind the kit. Thenthere's Fleetwood's current version of adrum solo: Perhaps the most playful artistin the business, Mick surprised the audi-ence on Fleetwood Mac's recent tourwhen he jumped out from behind hisdrumset and began slapping his chest,playing trigger pads that had been sewninto his vest. Prancing around the stage,Fleetwood kept something of a runningdialog, yelling to the audience severaltimes, "Are you with me?"

Fleetwood was demanding no less ofthe audience than he demands of himself.That sort of emotional connection definesthe musical experience for the drummer."I have a lot of vocals in my monitors, aswell as lead guitar, because I want to hearevery little nuance," Mick says. "That'sthe way I trained myself, to listen like ahawk for those emotional moments. IfLindsey [Buckingham] turns around, hejust has to look in my eyes to know thatI'm thinking, I 'm not just sitting here,I'm with you.'"

While Fleetwood says he plays from amore emotional than technical place, hestill takes his playing seriously. Insistingthat his approach has changed little sinceFleetwood Mac's pop domination in the1970s, Mick reiterates that he focuses onkeeping a good beat mixed with relativelysimple fills. Providing a strong foundationfor the rest of the band is his priority.

While his basic style hasn't changed,though, Fleetwood believes that his drum-ming today is some of the best of hiscareer. "I hope that people say they thinkI'm playing better," he says. "I'm moreconsistent than I've ever been. I think ithas something to do with the fact that I'ma little more leveled out as a person; I useto play flat-out drunk most of the time. Idon't drink anymore, but I still play veryemotionally. I grab the moment."

Doane Perry has been keeping busybetween Jethro Tull obligations. In addi-tion to working on a Tull 30th-anniver-sary studio LP, Perry and singer EllisHall are in pre-production for therecording of their next Thread project,with plans to tour in the spring. Doanecan also be heard on an album by StanBush.

Andy Peake has been working livewith Delbert McClinton.

In addition to working with DavidBenoit, John Ferraro can be heard onTim Weisberg's latest recording. Johnalso performed at the huge PromiseKeepers meeting in Washington a fewmonths back, as well as playing somegigs with Abe Laboriel and JustoAlmario.

Cliff Almond is on the road withManhattan Transfer.

Eddie Bayers recently recorded withRandy Travis, Matreca Berg, PattyLoveless, Rhett Akins, John Anderson,Neal McCoy, the Kinleys, David Kersh,Rick Trevino, Sammy Kershaw, theWilsons, George Jones, Colin Raye,Clint Black, Hank Williams III, George

Strait, John Berry, Mark Wills, BrianWilson, Alan Jackson, and Pam Tillis.

Stan Lynch recently producedreleases by the Grand Street Criers,Jackopierce, and Zaca Creek. In addi-tion, Matreca Berg, the Cikadis,Meredith Brooks, and Toto all coveredsongs written by Lynch on their lastrecords.

Paul Cook is on Edwyn Collins' I'mNot Following You.

Jim Keltner, Brian Blade, DavidKemper, and Winston Watson are onBob Dylan's latest, Time Out Of Mind.

Ex-Sugarcubes drummer SiggiBaldursson on the Reptile PalaceOrchestra's Hwy X.

Craig Krampf and Jeff Finlan areon Matthew Ryan's May Day.

Gregg Bissonette is on SteveLukather's new solo recording, Luke.

Pat McDonald is now with TanyaTucker.

Congratulations to John CougarMellencamp drummer Dane Clark andhis wife Tina on the birth of their daugh-ter, Abigail Rose.

Harriet L. Schwartz

For many fans, last year's Radiohead tour was one of the most eagerly antici-pated in many a moon. It certainly says something about opening bandTeenage Fanclub that the buzz surrounding their set seemed as loud as that forthe eminently hot 'Heads. Where that band appeals with theater and mystery,the Fannies (as they're fondly known) attract with immediately likable guitarjangle and warm & fuzzy vocal harmonies.

Drummer Paul Quinn is very aware of his band's (deceptively) simplestrengths, and does his part to accentuate them. "Simple things are probablythe hardest to do," Quinn suggests, "You know, setting the right beat for a songwithout allowing it to move. And I'm a perfectionist; I don't like things wavering.I get upset with myself quite a lot."

No need for that, from this angle at least. Since leaving the dancey SoupDragons (remember their hit cover of the Stones' "I'm Free"?), Quinn has sup-plied solid, stripped-down backing to some of the most laudedpop songs of the last decade, including the Fannies' mostrecent album, Songs From Northern Britain. "For me themost exciting aspect of this band is playing behindthree great songwriters. You can get stale if there'sonly one writer and he likes drums played in acertain way. Each guy has his own style, andwith Raymond (McGinley) in particular, there'shardly ever a simple 4/4. .well, it may be sim-ple upstairs, but there's loads of off-beatshappening with the bass drum and stuff. So Idon't get bored."

Quinn certainly had his share of distrac-tions in the Soup Dragons: Their Manchestersound required him to play quasi-hip-hopbeats to sequencers, with a lot of percussionscattered about his setup. "When I started toplay with the Fanclub," the drummer explains,"the first thing I did was strip my kit right downto basics. I don't need to be too flamboyant inthe Fanclub; I like to sit back there and let theharmonies and the guitars provide the subtleties. Iwould rather under-play things than over-play. I'ma firm believer that if there is a great song there, youjust have to play behind it, and everything will be true."

Adam Budofsky Tom Sh

eehan

Gen

e A

mbo

As Kevin Hayes explains it, every so often he gets a visit fromone of the old-school blues drummers he's idolized over theyears. Sometimes they'll say to him, "I like the way you play," towhich he quickly responds with a laugh, "I hope you don't recog-nize all that stuff I've lifted from you." Stuff like playing a 12/8beat, or playing the ride cymbal without a swing feel, or just get-ting the groove as deep as possible—those are the things Hayeshas taken from listening to albums by such blues greats as B.B.King, Howlin' Wolf, and T-Bone Walker. Hayes has applied thesecrets he learned to both his Robert Cray Band day job and hissession gigs with the legendary John Lee Hooker on such albumsas Mr. Lucky, Boom Boom, and Don't Look Back.

Hayes first joined the Cray band full-time around eight yearsago, after playing with various members of the group in variousSan Francisco Bay Area bands. Cray was in the middle of a tour,and Hayes was working at home "juggling a bunch of possiblegigs." Apparently the band was aware of who Kevin was, thedrummer says, because, "When Robert called and said, 'We'vedecided to make a change, and you're the guy we want,' I leapt atthe chance."

From then till now, Hayes admits, "I've never been a real'chops' guy." Instead, Kevin says he has worked on the art of thepocket. "Basically I've been more of a groove player. I've alwaysbeen fascinated by the way the pocket works depending on whoyou're playing with in the band, and how the push and pull hap-pens. How a groove feels and where the placement of the beat ismakes such a difference in terms of the way the groove feels."

Hayes says being focused on the time is his main job. "In theCray band, if you can't make the groove happen, there's nothingthere. The songs are good, and his singing and playing are great,but it really is about making that groove happen. That's got to bethe objective for me every night."

David John Farinella

Freelance musicians in the jazz/fusionworld know that the keys to success arcdeveloping the technique to play practical-ly any piece of music, and the ears to playwith any ensemble. Look at the resume ofsaxophonist David Sanborn's drummer,Jonathan Joseph, and you may concludethat he's taken this philosophy to theextreme.

The thirty-year-old Floridian leads amusical double-life, touring internationallyboth with Sanborn's contemporary sextetand with his jazz standards quartet, the lat-ter of which incorporates a fifty-piece sym-phony into each performance. "They'retotally different gigs," Joseph says. "Thesextet is basically a funk/R&B group—more intense, louder, and more 8th- and16th-note oriented. The symphonic group ismore textural, and I'm allowed moreimprovisation."

Joseph's diversity comes naturally. Hismother was choir director for their Miamichurch, so he started out playing gospelservices at age six. Private instructionthrough his formative schooling years ledto acceptance at the University of Miami,

then to polar-opposite touring and record-ing stints with R&B vocalist Betty Wright(the 1993 CD Beatitudes) and steel drummerOthello Molineaux (It's About time, releasedthat same year). Weather Report's JoeZawinul recruited Joseph for tours by hisZawinul Syndicate in 1993 and 1994;1994also included touring with Latin jazz flutistNestor Torres.

Nineteen-ninety-five proved to beJoseph's breakthrough year. Aside fromjoining forces with Sanborn, the drummerwas spotted in Miami by guitarist PatMetheny, who hired him to substitute forPaul Wertico on upcoming Asian dates.Joseph calls the Japan-and-Korea tour "oneof the musical highs of my career." Late in'95, trumpeter Randy Brecker called Josephabout recording; the New York sessionsresulted in his new Into The Sun CD.

Joseph's speed and precision are reminis-cent of Billy Cobham, who he considers abig influence. But even someone who prac-tices exercises from George Stone's StickControl before each gig knows that dexteri-ty comes more from the head than thehands. "I'd say it has less to do with tech-

nique than with musicality and your musi-cal environment," Jonathan suggests. "Thetechnical stuff is more of a personal thing."

In addition to his work with Sanborn,Joseph recently performed Yamaha clinicswith guitarist Mike Stern and bassist JeffAndrews, a Japanese tour with Torres, andshows with vocalist Al Jarreau. Even bySunshine State standards, this drummer'sfuture looks very bright.

Bill Meredith

by Robyn FlansPhotos by Sharyl Noday

regg Field first met Louie Bellsonat a band camp in Lake Tahoewhen Gregg was sixteen years

old. Bellson recognized Gregg's talentthen, even asking how he got hisunique bass drum sound.) It was acheese cloth that covered the entirebatter side of the bass drum with ahole cut in the middle.) Not long after,Field begged to accompany Bellson tosome Canadian jazz festivals, andBellson agreed.

Fast forward twenty-six years.Gregg Field has just finished produc-ing a Louie Bellson recording for thesecond time. He produced Bellson'slast Concord release. Air Bellson, witha small band. This new big band pro-ject (still untitled as of this writing)should be out on Concord early in1998. The album contains never-before-released recordings of piecesby such notable arrangers us ThadJones, Bill Holman, Tommy Newsom,and Bob Florence (many co-written byBellson). Louie is a featured performeralong with such stellar musicians asPete Christlieb, Mike Lang, amd ChuckBerghofer. M D was able to attendsome of the sessions, and to obtain thefollowing comments from both the per-former and the producer.

G

LB: Gregg really knows what to do in a recording session. Yearsago everything sounded great while we were in the studio, butwhen the record came out we'd say, "Where's the band?" Wedidn't realize that the mixing and the editing were the most impor-tant things. Gregg got me the best drum sound I've ever had in mylife. We all respect him as a great drummer, but we respect himeven more as a musician who can tell not only the rhythm section

what to do, but the entire band. He also knows what to do in thebooth.RF: What was Gregg able to give you in a sound that you hadn'thad before?LB: Don't get me wrong—the other albums were good. But Greggsaid, "We need an hour and a half to get a good drum sound beforeanybody comes in," and we had never done that before. The engi-

neer would say, "Hit the bassdrum once...hit the tom-toms...the snare drum. Okay."But that's not enough. It takes anear like Gregg's—along with anengineer like Don Murray—toreally know how to capture thesound of that drumset. WhenGregg did the Air Bellson album,all the reviews—and lots of otherdrummers—raved about thedrum sound.RF: What is it you do, Gregg?GF: Often, in a situation wherethere are a lot of musicians play-ing live, the drummer is the per-son who suffers the most in theprocess. With twenty-four tracks,I've run across situations wherethe brass and the reeds are indi-vidually miked, the piano ismiked in stereo, the bass has botha direct line and a mic' track, andfive or six tracks are left for thedrums. Traditionally, engineers will mix the tom mic's in with theoverhead mic's because they are simply running out of tracks. Butthat way, if you try to add a nice reverb to the toms, then you'readding reverb to the ride cymbal, which really washes it out.

When I was asked to produce Bob Florence's record (Earth), itwas also the first record I was going to play on. I thought, "I wantto get an engineer who is able and willing to put the time in to getthe detail of drums." For my money, Don Murray is as good as itgets. When I was brought in to produce Air Bellson at the eleventhhour, the studio and the engineer had already been picked, so I hadto use some of the tricks I had learnedfrom Don Murray. During playback,he likes to keep the tom mic's at arather low level, because there is anambient rumble in those mic's fromthe entire kit. Then he finds all thetom spots in a particular tune. Hemoves the tom mic's up just for the times you're hitting, and thenhe pulls them back down. That tends to result in a very clean,punchy, and present drum sound. He doesn't spare the tracks,either. Nothing is being combined, so the detail is there. I've neverseen an engineer who takes that kind of time. I first heard himwhen he recorded the GRP Big Band with Dave Weckl—and ofcourse Weckl's sound is wonderful.

Fortunately I came into this new project at the very beginning,so I was able to pick the studio and engineer. We picked Capitol,and we picked Don Murray. The detail in Louie Bellson's dynam-ic drumming has to be captured by a great engineer, and that'swhat Don does. I've been listening to Louie for thirty years. Iknow his sound and I know what he likes, and I want to give thatto him.

When you turn on a traditional pop or rock station—or even asmooth jazz station—it's exciting to hear the really punchy,

smashing recordings. For so long I wondered why jazz musiciansare not afforded the excitement of a really clean, punchy, presentrecording. It's like Louie said: Oftentimes there's a lack of aware-ness among the musicians as to what can be done.RF: Is it budget, too?GF: That's the first thought a lot of artists have, but it's not reallyso. We tracked this entire album in four sessions, so we're talkingabout twelve hours. Maybe you have to spend $50 an hour more togo to Capitol, but when you're talking about twelve hours, that'sonly $600. When you're talking about your life and your art, and

it's a matter of $600 to go from a mediocre studio to the best,there's not even a question for me. If you don't have the moneynow, save up and wait.

There's also the fact that you want to be able to compete withthe sound quality of what's out there. As an artist and a producer, Ireally can't afford to put out a recording that doesn't come up tothat level.RF: What can you do at Capitol that you can't do somewhereelse?GF: It's not that it can't be done at other places, but it can be doneeasier at Capitol. It's a room that has been used a lot and is veryunderstood by the engineers. Don Murray has done countlessrecords there, so he knows its shortcomings and its sweet spots.They have a great Neve board in there, which I really like workingon. I've probably done fifteen or twenty records on that board as aproducer. Whatever you need, they have. Also, it's very much a

"I've been listening to Louie for thirty years. I know his sound andI know what he likes, and as producer I want to give that to him."

Gregg Field

family environment.Everybody knows eachother, and everybody iscomfortable. They don't sitand watch the clock there;they want to help you make agreat project.LB: I told Gregg from thebeginning that I liked the wayhe felt about the setup.Sometimes producers put me inmy own little house, so I can'tsee anybody. If it weren't forheadphones, I'd be lost. On thissession, everyone could see meand I could see everybody. Ofcourse, we had headphones too.But it was more comfortablebecause it was more like a bandsetup—almost like the Glenn Miller setup: saxophones on oneside, brass on the other side, and me in the middle. When youthink of all these technicalities ahead of time, it saves a lot of time.GF: You have to take into consideration that the musicians areused to hearing the drums acoustically at a particular distance from

where they are. If you completely change that variable, not onlyare you asking the musicians to play their best, but you're askingthem now to make a sonic readjustment to their spatial environ-ment. I've done big band records in the same studio we used,Capitol A, where I was playing on the loud side, and I found thatmy drums would leak into microphones that were twenty and thir-ty feet away. It would create a gym-nasium effect and wash my soundout. It's a trade-off: If you put Louiein the booth and isolate him, you geta really clean, punchy sound, butthen you have this readjustmentproblem of "How do I listen?" Weworked diligently on finding thebest spot in the room whereLouie's sound was controlled—so it wasn't spreading out allover the room—and yet themusicians didn't even have toplay with headphones to hearhim if they didn't want to. Onthe walls of Capitol A areslats that can be opened todiffuse the sound and helpwith that "ambient drums

or loud instrument washingaround the room and beingpicked up by the mic's" situa-tion. We experimented withputting the slats in differentpositions to "dry the roomout" a bit and to control thatambient problem. But themain concern was to get theband in a place where theycould hear each other.LB: Preparing for analbum as a band is amajor time-saver, be-

cause once you get into thestudio, people like Gregg and Don

Murray have their hands full just producing a sound. Ifwe're not prepared music-wise, that's where the money goes. Oneof my concerns was to make sure, without spoiling the effect, thateverybody had a chance to play. You can't have players of thatquality just sitting there playing whole notes. So everybody had achance to do some solos, within the context of the idea we had,which was a salute to the arrangers. All of this was out of the waybefore we ever went into the studio.

GF: Louie arranged a pretty rigorous rehearsalschedule, along with a live performance a weekbefore the sessions. By the time the red light wason, they'd been playing it.LB: The worst thing for a big band to do is have agreat arranger come to a record date with twelvecharts they've never seen before. Even though theband is super, it's going to take hours and hours to

get it. Then you put it down real fast, and when you hear it sixmonths later you think, "Gosh darnit, I wish we had played it bet-ter." It's important to lay it down the right way, because you haveto live with it.GF: I made a number of albums with Count Basie with a producerwho had a completely different attitude. We would go in the stu-dio, get the music, rehearse the tune one time, and then record. Itwas tremendous pressure, and exactly what Louie said came true:

We'd play the arrangements on the road, and sixmonths later we'd hear them really

come into something towhich the recordingdidn't even compare.RF: Usually, no matterhow well you prepare,something doesn't go asplanned. What obstaclesdid you find yourself hav-ing to conquer once youbegan these latest sessions?

LB: To tell you the truth, Idon't think there were any. Ithought maybe it would takeone or two tunes to get ready,but even though we started a

"Gregg knows the music and the drum parts.That really made it so much easier for me."

Louie Bellson

little late, on the very first take of the first tune, I felt comfortable.GF: That first tune is so important. It sets the tone for the wholedate. You don't want to keep guys waiting.LB: I didn't have any problems with anything at all. I think a cou-ple of times I said, "Let's try this part over," or "Let's make anoth-er take," which is natural. But this session was very much like theone we did with the small band. On that one, we did nine sides thefirst day.GF: When we did that first Duets session with Frank Sinatra, hedidn't want to sing for two days. When he finally felt like singing,we did nine tunes in three hours.LB: When I was with Benny Goodman, we were out here doing amovie. We did a number called "Paducah," and Frank was singingon it. I'll never forget it. We spent nine hours on that tune, and hewound up taking the first take.RF: What were some of the difficulties for each one of you indi-vidually on this project?LB: Sometimes a leader can try to express something to a drum-mer, but he doesn't succeed because he can't explain what hewants. With Gregg, it was, "Lou, watch this bar...see if you canfill in this bar," because he knows the music and the drum parts.That really made it so much easier for me. I can remember doingrecord dates years ago at a place in New York called LeiderkranzHall, which was like the old concert halls in Vienna. They had twoTelefunken microphones in front of the band and that was it, andboy what a sound. Today you don't have a Leiderkranz Hall, soyou have to have those mic's set up like Gregg said, or you're outof luck. Before Benny Goodman died, he tried to reenact thoseLeiderkranz Hall days by recording with very few mic's, and hedidn't get a good sound at all.RF: Do you always record live?GF: I've been watching Louie record for twenty-five years. Healways records live with everybody.LB: It's a more honest way of playing.GF: It's like a pendulum that keeps swinging. When I first startedrecording in the late '70s, doing a lot of R&B sessions, I would laythe drum part down by myself. Then they would overdub the bass,and the song was built up like that. But the nature of that musicwas not about spontaneity; it was about a groove and a sound.That's never been what jazz is about. Jazz is about the interactionof musicians. To take that element away just to get a slightly bettersound would really be not seeing the forest for the trees. When werecorded with Frank, we would go into Capitol A and B becausethere were about seventy of us. Frank wasn't there in the after-noon, so those sessions were strictly for all the notes to be workedout. That way, when the old man came in and was ready to sing,the third trombone player wasn't saying, "Is that a B or a B flat inbar 33?" We would record those afternoon sessions, though, justfor reference.

One time they asked Frank to put on a set of headphones andsing over something we had recorded earlier that day. They hadn'tlaid more than twenty bars when he pulled the phones off and said,"This is hooey. I have to hear the band." When we record, he's inthe middle of the room. He wants to hear that brass hitting him andthe drums hitting him. It fires him up. He never overdubbed; henever fixed a note. Whatever you hear Frank Sinatra sing on anyrecord is what he sang from top to bottom.

LB: That's the way the old masters like Benny, Tommy Dorsey,and Duke Ellington all recorded. Whatever you heard is how theydid it.GF: And Louie, too. During this date, we had a problem on onetune with Louie's right bass drum. It was only three or four notes,but it seemed like when Louie really jumped on that bass drum, itwas distorting the mic'. Fortunately I had another mic' very closeto the bass drum, so I was able to deal with it. But initially, I wastrying to think, "Could I have Louie just go in and overdub thosebass drum parts?" Forget it—that's not what he's about. It wasmore important to capture what he played, so we covered it withanother mic'.

The other challenge during the date was realizing that we hadseventeen of the highest-paid, highest-profile, most accomplishedmusicians in the world sitting in a studio, fired with energy—andto make sure not to waste their time or cause them to lose thatenergy. I remember watching Phil Ramone produce Sinatra. Evenunder the most tense circumstances, he could diffuse it and get thejob done. I really respected that. Part of that is knowing when totake a break, when to get things going, and when they've played atune too many times. If a musician loses the fire, it's going tocome out on tape.LB: I have little signals with my guys in the brass section and reedsection. All I have to do is look up there and one of them willpoint at their chops and say, "Lou, give us a few minutes so theblood comes back." Those guys are blowing, and after a toughtune, they might need five minutes to get their heads together.

RF: On the other hand, you want to make sure they don't lose themomentum, so you can't let them get into goofing around.GF: Welcome to the world of producing. The other thing youcan't lose sight of is that when you're making music, you're sup-posed to have fun.LB: When we assembled the band, we were very careful to getguys who knew one another—not only musically, but as humanbeings. That mixture really makes it—especially in a rhythm sec-tion. The foundation is there, and you build a house that way.When you have that going, you're 90% there.GF: Especially with Chuck Berghofer playing bass.LB: Yeah, I'll tell you, he's just like a rock. He gives the drummera lot of freedom to express himself. I don't have to beat the bassdrum to death, because I have that rock-bottom feel there. Jo Jonessaid to me a long time ago, "Play the bass drum, but not likeyou're marching down the street. Play it so it's felt and not heard."Those words have rung in my ears for years.RF: Any other interesting, unexpected, or problematic moments inthe studio?GF: We started at 4:00 in the afternoon the first day, and it was adouble session. Everybody was working very hard. We took a one-hour dinner break between the two sessions, but our food was latein coming. Louie hadn't eaten yet when all the musicians wereback, and it was time to get back to work. I was thinking, just fromthe producer's standpoint, "Now I've got a drummer who has toput out a bunch of energy, and we have three more hours to go.How much can I expect of Louie at this point?" The food showed

up five minutes into the second session, but Louie said, "No, no,let's keep working." He grabbed little pieces of bread betweentakes, and all of a sudden it was 10:00 at night. We were doing"Your Wake-Up Call"—which is really difficult—and Louiewasn't backing off one iota. I kept wondering, "How can this guybe doing this?" Louie has always been my hero, but now he's evenmore my hero.LB: I remember the days when we used to play nine shows a dayat the Apollo with Duke. Sometimes there wasn't a chance to eat,so we'd have to go ahead and play. Somehow you did it.GF: This is Louie's record, yet in the two days of recording, henever complained about anything. Talk about a producer's dream.I can't wait until the next one.LB: I told Gregg last night that I'm already working on music. Ilearned from Duke to write music every day. I don't care if it'sfour bars or eight bars. You can never tell when you're going towant to use those four or eight bars.

Carl Palmer

I will be putting my solo project out some time in 1998. It's part of an ELP program, andwill be a Carl Palmer Anthology including recordings from 1965 onwards—right up to

the Percussion Concerto I've had ready for years. I'm afraid I can't give you an exactrelease date; perhaps you should call the label (Rhino Records) to inquire.

Thanks for all the complimentary words about my clinic. I like to do six to eight clinicsper year; they're very important to me. I love to talk about drums, and to play as much as Ican at my clinics. As for a video, I honestly have no plans to make one. There are many good videos on the market, but I mustsay there are also many bad ones. Of course, I won't rule out the possibility that I might make a video some day—or perhapsa CD ROM would be even better!

Dave WecklI saw you in clinic in Fresno about a year and a half ago.During the clinic you did a one-handed roll with your

left hand. It was incredibly quick and clean. I've tried to dothe same, but I haven't got it yet. I'm judging that thesecret lies in the fingers, but I can't be sure. Can youexplain the technique involved with that roll?

Jimmie Adamsvia Internet

First of all, thanks for writing! The roll I think you'rereferring to is played with the left hand, using conven-

tional or "traditional" grip. It's done mostly with a bouncetechnique similar to—but probably not exactly like—theone Buddy Rich used on the hi-hat on the second of histwo documentary videos (available from Warner Bros.

Publications), which is where I saw it and became inspiredto try to learn it. Although the fingers are involved in thestroke, they are not totally responsible for making it hap-pen. There is a lot of thumb involved.

I think the easiest way to understand it is this: Play ashuffle with your left hand. On the quarter notes, throwyour fingers out to the side—basically making the strokewith your thumb. (Bounce and balance are critical for get-ting this to work, so don't hold the stick too far back.) Onthe little strokes in between the quarter notes, bring the fin-gers back in to the stick. Once you can do this, try to "evenout" the shuffle so it becomes "straight." From there youjust have to work at the "action/reaction" of the stick usingthe technique above, and try to increase speed.

This technique is obviously not a priority in playingdrums for most applications. It was really something that Ijust wanted to attempt to learn for the heck of it. I havefound some musical applications for it, though. One wouldbe in an up-tempo straight-ahead jazz style for continuous8th notes on the snare. Another is to do it with both handsat the same time—one on a ride cymbal and the other onthe snare—for a jazz samba feel. I've also recently beenmessing around, just for fun, at attempting to do a single-stroke roll with that technique applied to both hands, whichis much faster than I could ever play it using any other con-ventional technique. But please be aware that this, as withany technical concept, is a means to an end—that endbeing good-feeling music. The cardinal rule is: If it doesn'tfeel good, don't play it.

I've been a fan of yours for about twenty years. I was recently very fortunate to attendone of your rare drum clinics. I'd like to thank you for sharing the tips and insights you

gave me.I've read that you will soon have a solo project available. If so, what is it titled, and

when will it be available? Also, you are such a great talent...why have you never releasedan instructional video?

Ivan Weissbuchvia Internet

Q

A

Q

A

Ric

k M

alki

n

tried many kinds of cymbals, and I havemade some expensive mistakes and had tosell some really great cymbals. I now thinkits time to ask a pro what to do. Whatbrand and type of cymbals do you recom-mend for my situation?

Guapovia Internet

Asking for "light, not-too-loud cymbalsthat give some stick definition during

jazz but can give somewhat of a cut forrock while producing a light wash" is sortof like saying you want a family sedan thatcan also haul concrete and win Indy raceson weekends. Asking any single type ofcymbal to serve all the needs you describeis asking a lot. We've entered an age ofspecialization within cymbal selection;most manufacturers offer models "target-ed" for jazz, rock, Latin, etc. Many drum-mers take advantage of this specializationand create different cymbal setups for eachtype of playing that they do.

Of course, creating different setups canget expensive, and at your age you may not

be ready for such acoustical diversification.In that case, your best bet may be to ignoreall the specialized cymbal models for thetime being, and instead to look for somegood, general-purpose cymbals that offerversatility. All of the major brands offerwhat can best be described as "middle ofthe road" lines, offering a bit less special-ization and a bit more flexibility than theirother lines. (These would include ZildjianAs, Sabian AAs, Paiste 2002 models, andMeinl Classics.) Within those lines, lookfor medium-weight rides and medium-thinto medium crashes. Because you don'twant to overpower your jazz situation, 15"to 17" crashes would do well there. But forthe added cut and sustain you'll need in arock/ska situation, you might want to con-sider an 18" crash as well. Hi-hats of 13"or 14" sizes (again in a medium weight)will prove most versatile for your purposes.If budget is a major consideration, look forthe same types of cymbals within Zildjian'snew ZBT Plus line, Sabian's Pro line, orPaiste's Alpha series.

The beauty of choosing cymbals of this

Thanks a lot for the great article aboutthe Flyin' Traps album. It was great to

hear the artists' views on the tracks theyrecorded. However, when I asked about theCD at the record stores in my town, theyhad not heard of it. Is Flyin' Traps out yet?If not, when will it be released?

Flyin' Traps, on Hollywood Recordscan be found in any good record store.

I am a sixteen-year-old drummer and Iplay all kinds of styles. I practice music

for the school jazz band, and with an alter-native/groove-rock band, and I have offersto join a reggae/original ska type band. I'mlooking for some light, not-too-loud cym-bals that give some stick definition duringjazz but can give somewhat of a cut forrock while producing a light wash. I've

Patrick Bastedovia Internet

Flyin' Traps

The Right Cymbal

AA

Q

Q

type is that they will serve in almost anyapplication now, and can be the core of amore sophisticated and esoteric selection ofcymbals that you collect as your career andexperience develops.

Safe StorageI recently bought a five-piece, mid-'70sSlingerland set in great condition. As

this is my first kit, I am concerned aboutkeeping it in a safe place to avoid damage.At the moment, I am keeping it in my base-ment. Is this a good idea? The basement isnot "musty" and it does not require that Irun a dehumidifier to keep out dampness.But I am still looking for reassurance. Iwould hate to unwittingly cause any dam-age to this prized possession.

Scott BurggrafToronto, Ontario, Canada

As you have already surmised, damp-ness in a basement is the greatest risk to

drums stored or set up there. If, as you say,you don't have that problem, then it's like-ly that your drums will not be at risk in thatarea. However, since accidents involving

plumbing sometimes happen (resulting inflooded basements), we recommend thatyou set up your kit (or store it in its cases)on some sort of elevated platform. This canbe as simple or as fancy as you desire. A"safety riser" can easily be created fromindustrial wood pallets covered with asheet of 1/2" plywood. Cinder blocks orplastic crates can also be used as supportsfor a plywood top. Carpeting can be addedto make the platform more aestheticallyappealing (and to cut down on soundreflected off the bare plywood).

Carl's book. However, if your band isinterested in performing ELP material, youwill find excellent drum transcriptions of"Hoedown," "Jerusalem," "Letters FromThe Front," and "Brain Salad Surgery"(along with six Asia tunes) in AppliedRhythms, which is available through theMD Library.

Rogers DetailsI own a Rogers XP-8 kit from the late'70s. It has a 5x14 chrome Dyna-Sonic

snare drum. A vintage drum collectorfriend told me that if the Rogers badge has"USA" on it, the drum is a brass shell, andif not, it is a steel shell. Can you confirmthis? Also, the shells on the toms seemquite thick, with no reinforcement rings.Are these shells 100% maple?

Will DeBouverConyers, GA

Although we cannot state unequivocallythat every USA-made Dyna-Sonic fea-

tured a brass shell, we can say that themajority of them did. (It's possible that thelast American-made drums—manufactured

Carl Palmer TranscriptionsMy high school band is planning onplaying Emerson, Lake & Palmer's

"Karn Evil 9" at our spring concert. Themusic we got for the drum part isn't verygood or accurate. Is a drum transcriptionincluded in Mr. Palmer's book AppliedRhythms?

AUnfortunately, "Karn Evil 9" is notincluded among the transcriptions in

Q

Q

A

Q

AStephanie Piotrowskivia Internet

in the Fullerton, California plant during thedays of CBS ownership in the early '80s—used steel shells.) Any shells made fromthe mid-'80s on (when the Rogers namewas owned by Island Music of StatenIsland, New York and the drums weremade in Taiwan) were made of steel. Theeasiest way to determine the nature of yourdrum's shell is to apply a magnet to it. Ifthe magnet sticks, the shell is steel. If not,it's brass.

All XP-8 shells were made of 8-plymaple.

Hearing HoracioI 've heard it said that listening toHoracio Hernandez play is like hearing

two great drummers performing together. Ialways try to listen to great drummers (likeChambers, Weckl, Portnoy, etc.), so I'vebeen trying to find recordings by Horacio.But so far I haven't been able to find any-thing that features him. Can you give mesome suggestions?

Here's a list of suggested recordings thatfeature Horacio:

1. Michel Camilo, Thru My Eyes(TropiJazz RMD 82067)2. Gonzalo Rubalcaba, Giraldilla(Messidor 15801)3. Victor Mendoza, This Is Why (RamRecords 4515-2)4. Paquito D'Rivera, Cuba Jazz (TropiJazzRMD 82016)5. TropiJazz All Stars, TropiJazz All Stars(TropiJazz RMD 82028)

You can also see and hear Horacio'sincredible playing at Modern Drummer's10th Anniversary Festival Weekend onvideo. Horacio appears both on theHighlights video and on his own solo per-formance video. Both are available fromDCI Music Video and may be orderedthrough MD.

Rick Leevia Internet

Q

A

Intrigued by the look and sound of transparentdrums, but a little intimidated by the thought ofsitting behind an almost totally invisible kit?How about adding a hint of color? Fibes nowoffers their Crystalite acrylic drums in an ambertint. The new color will be available in all thir-ty-three standard shel l -depth and -diametercombinations (with some custom sizes alsoavailable).

Fibes Amber Crystalite Drums

Through A Drumshell,Darkly

Sabian Terry Bozzio Radia, Evelyn Glennie "Glennie's Garbage,"Chad Smith Explosion, and David Garibaldi Jam Master Cymbals,

PRO Series Rock Hats, Crashes, and Rides, and AAX Past Hats and Bright CrashAffectionately termed "Glennie's Garbage,"renowned solo percussionist EvelynGlennie's signature models are 10", 12", and16" accent cymbals shaped from a heavilyhammered nickel/silver alloy. They're said toproduce "raw and biting accents with raspy,exotic voices."

Sabian's new Radia lineup comprises cymbals, effects,and sounds created to Terry Bozzio's specs. The cym-bals are individually hand-hammered for tonal com-plexity and increased musical value, with their surfacescored (in gong fashion) to create an "ancient oriental"appearance.

Chad Smith's Explosion Crash is made ofSabian's B8 bronze for maximum cut andexplosive power. It's available in 18½" and20½" sizes.

David Garibaldi's Jam Master cymbals arehand-hammered for increased musical tone.According to Sabian, the 22" ride produces "adefinite stick response balanced with a con-trollable degree of warm spread," while the18" crash/ride emits "a powerful crashresponse and a ride sound of moderate defini-tion and maximum spread."

Also new from Sabian are PRO Rock models, including14" Rock Hats, 16" and 18" Rock crashes, and 20" and22" Rock rides. These are now the loudest cymbals inthe PRO series. Finally, the AAX series has been aug-mented with an 18" Bright crash and 13" and 14" FastHats, all with boosted high-end response, clarity, andprojection.

A Sampler Of Signature Cymbals And Special Sounds

The all-new LPMusic GroupComplete Per-cussion Catalogcontains over120 full-colorpages of highlydetailed productphotos withcomplete de-scriptions out-lining LP's

array of instruments. The collection ofproducts are available in three brands: LP(professional), Matador (intermediate oraspiring pro), and CP (school or beginner).

The catalog also includes an illustratedhistory of LP Music Group, an alphanu-meric index, and a complete parts section.A retail price list accompanies the catalog.To receive the catalog (as well as a rebatecoupon for $10 towards any new LP,Matador, or CP purchase), send a $10check or money order to: CustomerService, LP Music Group, 160 BelmontAvenue, Garfield, NJ 07026. If you don'twant to wait for a catalog, check outLP's new Web site, located at www.lpmu-sic.com. The site utilizes the latest in audioand visual internet technologies, includingthe use of PDF files, Quick Time Movies,and Real Audio.

Not content to deal only in new informa-tion, LP has also introduced Valje ArmandoPeraza Series congas and bongos. Thesedrums feature authentic Valje styling and

are crafted from kiln-dried, NorthAmerican cherry wood in a satin finish.Designed in conjunction with masterconguero Armando Peraza, the congasstand 30" tall and are available in threesizes. Each drum is equipped with tradi-tional-style chrome hardware, Valje-styleside plates, and non-marring rubber bot-toms. LP Conga Shell Protectors help toshield the fine finish on these drums. Pricesare as follows: 11" quinto—$620; 11 3/4"conga—$665; 12 1/2" tumbadora—$700.

Valje Armando Peraza bongos feature

cherry wood shells with 7 1/4" and 8 5/8" headsizes, and are fitted with natural rawhideskins. The steel tradi t ional r ims and

Cuban-style bottoms have a bright, durablechrome finish. A short center block bringsthe shells close together for easy seatedplaying, yet still allows the drums to bemounted on a stand for standing players.Suggested list price is $315.

Finally, LP now offers the original UduDrums designed and created by FrankGiorgini. Based upon ancient West Africanclay drums, LP Udu Drums possess dis-tinct tonal qualities ranging from subtlebass to soothing tabla-like tones. They areavailable in six styles: Claytone (in foursizes), Hadgini, Mbwata, Tambuta, Utar,and Udongo IL LP Udu Drums can beplayed in a seated position or on the flooror table-top (using the included LP UduDrum Straw Ring). Special microphoneports allow for small mic's to be mountedinternally for amplification.

LP Complete Percussion Catalog, New Web Site,Valje Armando Peraza Series Congas And Bongos, And Udu Drums

Everything You Ever Wanted To Know About LP...And More

SKB corporation is now offering totallyredesigned roto-molded cases in 8", 10",12", 13", 14", 16", and 22" sizes. Thecases are designed to "telescope" in orderto accommodate drums of any depth. Forease of storage, the cases "nest" withineach other, and they feature a contour thatallows them to stack without sliding. Eachcase is fitted with special foam inserts tohold the drum securely, and a heavy-dutyweb strap with a side-release buckle toensure secure closing. A "package" set ofcases (12", 14", 16", and 22") is currentlyavailable at a list price of $389.95.

Regal Tip is now offering a completeline of marching percussion mallets anddrumsticks. The mallets feature heads ofa composite material said to be as strongand responsive as felt, but that will con-tinue to work even when exposed towater (unlike felt). Also new are wood orvinyl grip multi-tom mallets with an alu-minum shaft and a disk-shaped nylonhead. Wood or nylon-tipped 17"-longsnare drum sticks round out the line.

Designed for use with a conventionalbass drum pedal or double pedal, DrumTech's Kick Pad combines elements oftheir 10" Flat Pad with a more durablesensor assembly and a modified playingsurface (to provide an acoustic bassdrum-like feel). The pad adjusts forheight and tilt, has dual outputs forchaining, and folds up for transport.Retail price is $229.

SKB Cases

Regal Tip Drum Corps2000 Line

Drum Tech Kick Pad

A New Case History

Marching IntoThe Next Century

Put Your FootDown...Electronically

Sonor's Trilok Gurtu model 5x10 snare drum is now available in the en t i re range ofDesigner Series high-luster finishes. The 9-ply Maple Light shell comes equipped withSonor's Advanced Projection System, which features rubber insulators on a l l t un inglugs. Tension rods are fitted with the Tune Safe system, which prevents de-tuning. Anupdated snare strainer tensions the snare wires in an even and dependable manner. Thedrum is recommended as a secondary snare for most applications, or as a primary snarein hip-hop, drum & bass, Latin, or funk.

Looks Little...Sounds BigSonor Trilok Gurtu Signature Snare Drum

Making ContactBeyerdynamic56 Central Ave.Farmingdale, NY 11735tel: (516)293-3200fax:(516)293-3288

Drum Tech (Sales)351 Pleasant St. #141Northampton, MA01060tel: (413) 538-7586fax: (413)538-8274

EvansJ. D'Addario & Co.595 Smith St.Farmingdale, NY 11735tel: (516)439-3300fax:(516)[email protected]

Fibes701 S. Lamar Blvd.Austin, TX 78704tel: (512)416-9955fax:(512)[email protected]

Levy's LeathersBox 3044Winnipeg, MB, CanadaR3C 4E5tel: (204) 957-5139fax: (204) 943-6655levys @ levysleathers.comwww.levysleathers.com

LP Music Group160 Belmont AvenueGarfield, NJ 07026tel: (800) 526-0508fax: (973) 772-3568www.lpmusic.com

Meinl Percussionc/o Tama DrumsPO Box 886Bensalem, PA 19020orc/o Chesbro MusicPO Box 2009Idaho Falls, ID83403-2009

Musician'sPharmacyIndesign Mfg., Inc.21 Willets DriveSyosset, NY 11791tel/fax: (516) [email protected]

Regal Tip4501 Hyde Park Blvd.Niagara Falls, NY14305tel: (800) 358-4590fax:(716)285-2710www.regaltip.com

SabianMeductic, NB, CanadaEOH 1 LOtel: (506) 272-2019fax: (506) [email protected]

SKB13501 SW 128th St.,Suite 204Miami, FL 33186tel: (305) 378-1818fax: (305) 378-6669www.skbcases.com

Sonor/HSSPO Box 9167Richmond, VA 23227tel: (804) 550-2700fax: (804) 550-2670

And What's MoreRealplayer Steelbells are new profes-sional-quality cowbells. Thinly lacqueredto prevent discoloration and corrosion,

each bellhas fullyweldedseams andis equippedwith a sturdymountingbracket thataccepts L-arms up to

10 mm in diameter. Small muffling padsare included as tone controls, but can beremoved for additional sustain and vol-ume. Sizes currently available are 8"large or small mouth, 6 1/4" mediummouth, and 4 1/2" small mouth.

TG-X 10supercardioid percussion microphone isdesigned for drummers and percussion-ists who need a high-quality mic' capableof accepting very high sound pressurelevels. It's small enough for close miking,but is said to be robust enough to with-stand "the occasional knocks that drummic's are often subjected to." It featuresan acoustic shock mount to rejectmechanical noise transmitted through theshell of the drum. Retail price is $279.

has expanded their Pre Pakline of prepackaged heads. Configured toreplace thebatter headsin the mostfrequentlypurchaseddrumsets,the new PrePaks (EPP-3 and EPP-4) includethree popu-lar tom bat-ters (coated Genera G2s) in the mostrequested sizes, plus a free Genera G1coated snare batter and a free Clip Key.

isa leather specialty company that'sbeen making stick and cymbal bagsfor years. Now they're offering theEMK line of soft-sided drum bags,featuring a polyester shell with foamcore and plush liner. Bags are offeredfor standard kits, as well as optionsfor toms and kick drums. Snare bagsfeature a detachable shoulder strap.

MEINL PERCUSSION

BEYERDYNAMIC's

EVANS

MUSICIAN'S PHARMACY

LEVY'S LEATHERS

offers Pro-Techt, a dietary supplement for-mulated to help the body heal from injuriesincurred as a result of repetitive motion—such as carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS)—along with arthritis and joint pain in gener-al. The product contains glucosamine sul-fate and chondoitin sulfate, which are saidto be major components of cartilage, ten-dons, and bones, and which provide rawmaterials for the body to produce connec-tive tissues. Vitamin B-6, vitamin E (forprotection of nerve sheaths), and VitaminC are also ingredients.

JC's Custom Drums

Here's a little kit that offersbig performance.

by Rick Van Horn

JC's Custom Drums are the brainchild of drum designer Joe Chila.Joe custom-crafts each kit in his shop in Michigan, using shells ofAmerican hard rock maple. His drums are available in two series:JC Customs and JC Juniors.

Custom models feature 5-ply toms and 6-ply bass drums—bothwith 3-ply reinforcing rings—as standard. "Thin is in, as far as I'm

concerned," says Joe. "However, I will make drums with othershell configurations if desired, along with solid-shell snaredrums."

Classic tube lugs (or optional small, brass "button" lugs), heavy-duty steel rims, and RIMS mounts are standard and included in thepurchase price of Custom series drums; die-cast rims are availableat extra cost. All sets are timbre-matched and are available in cat-alyzed urethane finishes ("in almost any color imaginable"), withcovered wraps, or in a variety of satin hand-rubbed finishes.("Satin finishes allow the wood to breathe a bit, they look good,and they're more environmentally friendly," says Joe.) Everydrum is personally signed and dated by Joe upon completion.

JC Juniors feature the samequality shells as the Customseries, but with toms and snaresonly in 6-ply configurations andbass drums in 8-ply. The drumsfeature the same custom-crafted45° bearing edges and RIMSmounts as the Customs as well.However, the use of low-masslugs, lighter-duty rims, and satinfinishes help to keep the priceslower for this line.

Although he offers drums inall contemporary sizes, Joewanted us to try a kit that was alittle different from the sizes wegenerally receive for review. Sohe sent us his personal giggingkit, in what is usually termed"jazz sizes." It consisted of an18x18 bass drum, 8x10 and8x12 rack toms, and a 14x14floor tom—all from the Customseries. The snare was a 4x14Junior, but was a slight excep-tion to the norm in that it fea-tured an 8-ply shell. All of thedrums were finished in a hand-rubbed satin finish in a classyburnt-orange color. The snareand toms came fitted withAttack single-ply, white-coated

Small Drums

Jim

Esp

osit

o

outstanding construction qualitydrums offer acoustic versatility that beliestheir size"gigging kit" sizes make kit compactand portable

18" bass drum needs to be elevated sopedal beater can strike batter head at its center

batter heads and clear, single-ply, medium-weight Terry Bozziomodel bottom heads. The bass drum was equipped with a RemoAmbassador batter (because an 18" bass drum head was not avail-able in the Attack line) and a Remo Ebony front head with no hole.

In terms of construction quality, all of the drums were donebeautifully, with smooth, sanded precision bearing edges and snarebeds. The tube lugs were attached to the shells at the top and bot-tom with very small posts, each of which was secured with oneAllen set screw. The brass tubing looked natural and warm againstthe burnt-orange finish, giving the kit the look of a fine, hand-crafted instrument.

Owing to their thin shells and small si/es (especially the bassdrum), the drums were light and easy to handle—making the kitvery appealing from a portability standpoint. Joe leaves the choiceof hardware up to the customer; in the case of our test kit the"rack" toms were suspended via multi-clamps and L-arms attachedto cymbal stands on either side of the bass drum.

Big SoundWhen played with the "factory-installed" thin, white-coated

heads, the small kit had a predictably lively, "jazz" sort of sound.The toms sang clearly, and offered a surprising amount of underly-ing tone behind a crisp-sounding stick attack. The Junior snaredrum was exceptionally crisp, clear, and cutting, offering plenty ofdynamic range and excellent brush response.

My first experience with the bass drum was less than over-whelming. It's a small drum, and it was fitted with a thin batterhead, so I didn't expect it to produce a thunderous low end. Butmy major objection was that the small diameter of the drum madeit impossible for my bass drum beater to hit the batter head at itscenter (when the pedal was clamped to the hoop in normal fash-ion). However, I improved on this situation by elevating the drumto a point where the beater could hit the center of the head. Iaccomplished this by extending the spurs and propping the batterside of the bass drum up on some foam rubber pads. My bass drumpedal has a baseplate equipped with enough non-slip material thatI didn't need to clamp the pedal to the bass drum hoop; I could justplace it in the appropriate position in front of the batter head. Butsince not everyone has such a bass drum pedal, it would be nice ifJC's could offer some sort of factory-installed elevation device(such as are available from some other manufacturers who offer18" drums).

Once I could strike the bass drum head in the optimum position,the drum produced a good deal more body and fullness—if stillnot a lot of low end. Owing to its 18" depth it also had a good dealof punch and projection, and plenty of resonance. (Remember,

there was no hole in the front head.) Jazz drummers would proba-bly leave that resonance alone; other players might want to addsome muffling for control.

My overall evaluation of the kit as it came out of the box (andwith the described elevation of the bass drum) is that it would be ajoy to play for any "traditional" small-group jazzer, and couldquite respectably cover most types of low-volume acoustic gigswhere tonality would be prized above sheer power or thunderousdepth.

But I wanted to find out if this highly portable kit could cut themustard in a more intense situation—like a small rock club, or awedding band playing a variety of styles. With that in mind, myfirst goal was to see if I could get more "bottom" out of the bassdrum. So I replaced the Ambassador batter with a twin-ply, self-muffling Pinstripe. Whoa—big difference (emphasis on the"big"). The drum suddenly sounded fat, punchy, and...well...deep.I'm not talking Carlsbad Caverns, here—it still was an 18" drum,after all. But it was definitely a bass drum, with enough depth andpower (and boominess, which one could take or leave) to competequite adequately in a small club situation. (And if you were tomike up this baby, you could probably compete in any situation.)

Given my success with the bass drum, I popped Pinstripes ontothe three toms as well. As with the bass drum, the difference wasimpressive. The fundamental pitches dropped considerably, andthe overall "bigness" of the drums' sounds increased dramatically.Again, I'm not saying that the drums suddenly sounded threetimes bigger than they really were. But they did sound fat, full,and powerful. As long as you weren't looking for earthquake-inducing low end, you could very likely get all the rock 'n' rolltom sound you'd ever want out of these little beauties.

I really didn't need to change anything about the snare drum;its sound would work beautifully for a rock gig. But just for thesake of durability (assuming that a rock player would hit harderthan a jazz or pop player) I put a white coated Emperor on thedrum. It lost a tiny bit of brush sensitivity, but other than that Icould discern no appreciable change in performance.

My final impression of this compact kit was one of pleasant sur-prise. I expected it to work well in a classic "jazz" context, and itcertainly did. I did not really expect it to apply as well to general-purpose use, and certainly not to a rock situation—but the kitproved me wrong. Given the proper heads (and the possibility ofmiking where applicable), this "gigging kit" could cut just aboutany gig musically, while offering compactness and portability intothe bargain! With today's trend toward smaller drumkits, its niceto know that one can also consider smaller drums as well.

But That Ain't AllMy favorable impression of Joe Chila's small "gigging kit"

shouldn't imply that those are the only JC's Custom Drums youshould consider. As I said earlier, Joe offers drums in all sizes, andhe would be thrilled to create monster tubs for you, if that's yourpreference. The point is that JC's Custom Drums offer outstandingquality—both in sound and construction. No matter what sizesyou're interested in or what type of music you play, you could beconfident that JC's Custom Drums would serve your needs in anoutstanding manner.

Joe Chila builds each JC's Custom kit to order, according to the

WHAT'S HOT

WHAT'S NOT