My Introduction to 'Zinoviev and Martov: Head to Head in Halle', translated and edited by Ben Lewis...

Transcript of My Introduction to 'Zinoviev and Martov: Head to Head in Halle', translated and edited by Ben Lewis...

Head to head in Halle

6

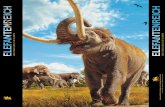

Front cover of the popular German satirical magazine, Ulk, from October 29 1920. Entitled ‘Cunning Russian strike’, it depicts a sabre, emblazoned with ‘Moscow’, splitting the USPD in two. In the one hand the victim carries a brief-case bearing the name of USPD left leader Däumig. The briefcase in his other hand is that of Dittmann, the USPD right leader. The caption reads: “Whether you look right or left, you see an Independent cleft”

7

The significance of HalleI : The significance of Halle

I The four-hour speech and the

significance of Halle Ben Lewis

Party comrades! It is not without a feeling of deep inner stirring and emo-tion that today I step onto this stage - the stage of the party congress of the class-conscious German proletariat, of that proletariat from which we have learnt so much and from which we will learn even more. Indeed, we have not come here merely to provide you with news of the experiences of our proletarian revolution, but also to learn something from the Ger-man proletariat and its great struggles. We will not forget that the German proletariat has gained much experience in the two years of revolution it has been through; that there is not a single town in this country where proletarian blood has not been shed for the proletarian revolution. We will not forget that proletarian fighters like August Bebel, Wilhelm Lieb-knecht and others have struggled in the ranks of the German proletariat. We will not forget that the German working class includes real heroes of the world revolution: Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg.

These are the opening words to one of the most significant speeches of the 20th century workers’ movement, delivered by Bolshevik leader Grigory Zinoviev at the Halle congress of the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (USPD). Many on the left will not have even heard of the speech or the split which followed it. With a few honourable exceptions, Zinoviev’s speech is often overlooked by histories of the Weimar Republic and the German workers’ move-

Head to head in Halle

8

ment more specifically.Between October 12 and 17 1920, the sharp debates fought out at Halle were

to shape the entire future of the German and indeed the whole European work-ers’ movement. Two opposing motions were placed before the 392 mandated delegates. They dealt with two simple yet profoundly controversial questions. Firstly, should the USPD affiliate to the Communist International, born in the aftermath of the Russian Revolution? Or was this unnecessary because the par-ties of the old Second International, which had ceased to function during World War I, were already reforming? Secondly, should the USPD fuse with the young Communist Party of Germany (Spartacus),1 or would this mean sacrificing its autonomy to an organisation that had just recently split away from it?

In 1920 the USPD had something close to 800,000 members and a press which included over 50 daily papers. But with revolutionary sentiment spread-ing like wildfire across Europe, the USPD stumbled from one crisis to the next.

In spite of its recently acquired fractious nature,2 the German workers’ move-ment was enormously powerful. As Europe’s leading industrial power, Germany was centrally important to the world revolution that the Bolsheviks had banked on in 1917. Russia was a backward country with an overwhelming peasant ma-jority. The Bolsheviks had always been clear that their continued survival cru-cially hinged on the German working class taking power. Without correspond-ing revolutionary action in Germany, the Bolsheviks knew that the young Soviet Republic would be condemned to isolation and inevitable defeat. It was sur-rounded by a sea of hostile imperialist powers and subject to the overarching economic dictates of the world division of labour.

The importance of the German workers’ movement can be traced back to the success of the German Social Democratic Party (SPD). Between the 1880s and 1914 the SPD had served as a model for the workers’ movement internationally. His criticisms of its programme and its lack of republicanism notwithstanding, Friedrich Engels could barely contain his delight at its seemingly inexorable rise. Just before his death in 1895, he wrote:

Its growth proceeds as spontaneously, as steadily, as irresistibly, and at the same time as tranquilly as a natural process. All government intervention has proved powerless against it. We can count even today on two and a quarter million voters. If it continues in this fashion, by the end of the century we shall have the greater part of the middle strata of society, petty bourgeoisie and small peasants, and we shall grow into the decisive power in the land, before which all other powers will have to bow, whether they like it or not. To keep this growth going without interruption until it gets

1. Formed in January 1919, the Communist Party of Germany (Spartacus) only dropped the suffix in December 1920. Henceforth I will refer to it as the KPD(S).2. At the Halle congress, Arthur Crispien mocked the USPD left by pointing out that there were al-ready four different ‘communist parties’ in Hamburg alone. Paul Levi, then KPD(S) chair, corrected him with a heckle: there were actually five! Protokolle der Parteitage der USPD, Band 3, Berlin 1976, p77.

9

The significance of Halle

beyond the control of the prevailing governmental system of itself, not to fritter away this daily increasing shock force in vanguard skirmishes, but to keep it intact until the decisive day, that is our main task.3

Unlike the many ‘parties’ that parade themselves on today’s far left, the SPD had genuine mass influence and deep roots. As the historian Vernon Lidtke4 has shown, German social democracy was not so much a political party as it was another way of life devoted to the political, cultural and social development and empowerment of the working class. It ran women’s groups, cycling clubs, party universities and schools, published hundreds of newspapers, weekly theoretical journals, special interest magazines such as The worker cyclist or The free female gymnast and much, much more. “It was much more than a political machine” concurs Ruth Fischer: “it gave the German worker dignity and status in a world of his [sic] own.” Indeed, by 1912 the SPD had become the biggest party in the Reichstag with 110 seats and over 28% of the popular vote. Depending on their position in society, many either confidently or anxiously awaited the day when it would win a parliamentary majority and take over the running of society.

But the SPD’s expansion had also planted the seeds of opportunism and revi-sionism that would later undermine it from within. As the party grew, so did the gulf between its revolutionary theory and the dull routine of putting out newspa-pers, organising in trade unions and contesting elections.5 The goal of socialism and human emancipation was increasingly relegated to Sunday speeches, party congresses, annual festivals and educational events. An increasingly detached and largely unaccountable bureaucracy of over 15,000 specialist full-timers de-veloped, in which many party trade union leaders and functionaries saw no fur-ther than the struggle for higher wages and better conditions. Reichstag deputies immersed themselves in minor reforms and parliamentary deals. In other words the practice of the labour bureaucracy was becoming the norm, finding theoreti-cal expression in the writings of Eduard Bernstein - a former star pupil of Marx and Engels, who was now questioning the very basis of Marxism itself.

3. F Engels, Introduction to The class struggles in France (http://marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1895/03/06.htm).4. V Lidtke The alternative culture Oxford 1985.5. Here I believe that Pierre Broué, the late French Marxist historian who has probably written the most extensive account of the German revolution, is wrong to assert that “Kautsky did not renounce the maximum program, the socialist revolution, which the expansion of capitalism had made a distant prospect, but laid down that the Party could and must fight for the demands of a minimum program, the partial aims, and political, economic and social reforms, and must work to consolidate the political and economic power of the workers’ movement, whilst raising the con-sciousness of the working class. In this way, the dichotomy was created … This separation was to dominate the theory and practice of social democracy for decades.” Whilst it is doubtless the case that there were flaws in Kautsky’s conception of working class rule, the programmatic method he was defending in the Erfurt programme of 1891 was that of Marx and Engels - ie, the culmination of the minimum programme’s demands were understood to be the dictatorship of the proletariat or “the socialist revolution”, not what Broué deems mere “partial aims, and political, economic and social reforms”. See P Broué The German revolution 1917-1923 Chicago, 2006, p17.

Head to head in Halle

10

Rosa Luxemburg polemically savaged Bernstein. But it was another star pupil of Marx and Engels, Karl Kautsky, who spoke for the party’s centre - the ma-jority, orthodox tendency. However, Kautsky’s vision of the rule of the working class majority was problematic. For him, the existence of a state bureaucracy and the ‘rule of law’ were necessary in any modern state - bourgeois or proletarian.6 Primarily, however, he was resolutely committed to maintaining the unity of the SPD.7

Engels had not only pointed out some of these problems by noting the omis-sion of the democratic republic - “the form of the dictatorship of the proletariat”8 - from its 1891 Erfurt programme.9 With quite remarkable prescience he also envisaged two possible scenarios that could put a brake on, or even throw back the cause of German social democracy: a possible war with Russia, with the po-tential loss of “millions of lives”, or “a clash on a grand scale with the military, a blood-letting like that of 1871 in Paris”.10 And, of course, World War I sent millions of working class people across Europe into the mincing-machine, also ensuring that these “years of fraternal dispute” in SPD pubs, branch meetings and congresses “found their bitter end in fratricidal warfare”.11

War and collapseWhen on August 4 1914 the SPD Reichstag fraction treacherously voted for war

6. See M Macnair ‘Representation, not referendums’ Weekly Worker July 1 2010 for a discussion of Kautsky’s views on the state bureaucracy and working class rule.7. For an excellent discussion of the tension between the unions and the SPD, see D Gaido ‘Marx-ism and the union bureaucracy’, Historical Materialism No16, Amsterdam, pp115-136.8. F Engels Critique of the Erfurt programme (http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1891/06/29.htm). There are several points in Zinoviev’s diary entry and speech where he refers to understanding the dictatorship of the proletariat in an ‘Erfurtian sense’. This was a common Bolshevik phrase at the time, echoing some of Engels’s sentiments back in 1891. At the Second Congress of Comintern, for example, Lenin attacked Crispien’s “Kautskyite conception of the dictatorship of the proletariat”. This is Lenin in full: “Replying to an interjection, Crispien said: ‘Dictatorship is nothing new; it was already mentioned in the Erfurt programme.’ The Erfurt programme says nothing about the dictatorship of the proletariat, and history has proved that this is no accident. When we were working out the party’s first programme in 1902-3 we always had the example of the Erfurt programme before us. Plekhanov, the same Plekhanov who calmly said at the time: ‘Either Bernstein will bury social democracy or social democracy will bury Bernstein’, laid special emphasis on the fact that the Erfurt programme’s failure to mention the dictatorship of the proletariat was theoretically wrong and in practice a cowardly concession to the opportunists. And the dictatorship of the proletariat has been in our programme since 1903” (R A Archer The second congress of the Communist International, Vol 1, London 1977, p272). This is not to say that the Bol-shevik understanding of ‘dictatorship’ was consistently in accord with that of Marx and Engels - see H Draper The dictatorship of the proletariat from Marx to Lenin New York 1987. 9. Also of significance in this regard is the dispute between Kautsky and Luxemburg over the use of the slogan of the democratic republic in 1912. In line with the majority of the party, Kautsky op-posed SPD agitation for the republic, whereas Luxemburg insisted that it must form a central part of the SPD’s activity.10. F Engels Introduction to the Class Struggles in France (http://marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1895/03/06.htm).11. C Shorske German social democracy 1905-1917: the development of the great schism Harvard 1983, p322.

11

The significance of Halle

credits, following a deal struck with the trade union bureaucracy to avoid strike action in the event of a war, many in the international movement were catatoni-cally shocked. Hearing the news, for example, Lenin was convinced that it had been a fabrication on the part of the bourgeoisie in order to generate pro-war sentiments. But other parties in the Second International followed the German lead: with few exceptions, each party sided with their own bourgeois govern-ment. The usually indefatigable Rosa Luxemburg contemplated taking her life when she learnt that the Second International - once a symbol of international class unity - had betrayed its own name.

Even the great internationalist Karl Liebknecht had gone along with party discipline in voting for the war credits.12 But like the thirteen other deputies who had expressed their opposition in a private fraction meeting the previous day, he had put the unity of the party first in the hope that it could be rapidly won back round.

The German war government’s politics of Burgfrieden (civil peace) had enor-mous ramifications for the party itself. Exploiting the wave of patriotic demon-strations in favour of war against ‘the enemy without’, the German state appa-ratus had the perfect excuse to clamp down on ‘the enemy within’: censorship, conscription, and oppression against a workers’ movement that German abso-lutism feared just as much as the British navy. Kaiser Wilhelm II summed up the results: “I no longer know any parties, I know only Germans!”13

Indeed, while the German ruling classes had long envisaged creating a land empire from France to Russia to complement their colonial ‘place in the sun’, their turn to imperialism was primarily informed by domestic concerns - not least beating back the ‘red menace’ of the SPD. As historian Paul Kennedy notes, the SPD’s election results and social influence had “frightened all forces of the establishment”14 for quite some time. There were calls from big industrial capital and the great landowners, convinced that things like elections and democracy had gone too far, to curb the Reichstag’s already limited powers and eliminate the threat of the SPD once and for all via a “coup d’état from above”.15 The war, and with it the passing of political power into the hands of the military com-mand, can therefore be partly understood as the ruling class challenge to the workers’ movement. The tragedy is that the SPD was unable to rise to it. For all its size and organisational strength, it could not cope politically.

The SPD right was more than willing to put its shoulder to the war effort. It ruthlessly enforced a crackdown on the party’s critical elements. Those who viewed August 4 as an aberration that could quickly be reversed were soon proved wrong - party democracy was further constrained and things got much

12. Speaking to party comrades afterwards, Liebknecht said: “Your criticisms are absolutely justified … I ought to have shouted ‘No!’ in the plenary session of the Reichstag. I made a serious mistake.” Quoted in Broué The German revolution 1917-1923 Chicago 2006, p50.13. S Haffner Der Verrat Berlin 1995, p12.14. P Kennedy The rise of the Anglo-German antagonism - 1860-1914 London 1980, p453.15. Ibid.

Head to head in Halle

12

worse. Soon SPD leader Phillipp Scheidemann openly embraced the plans of German chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg for territorial annexation in a Reichstag speech, even meeting up with him beforehand to clarify any dif-ferences they still had. A cosy relationship.

However, the patriotic wave that allowed the SPD union leaders and Re-ichstag tops to promise class peace gradually gave way to anti-war sentiments. Shortages, repression and the horrific reality of the carnage across Europe shifted perceptions. The longer the war continued, the more instances there were of workers taking action against its deleterious effects. This inevitably found expression in the SPD itself. On December 1915, 20 SPD deputies re-fused to vote for further war credits. Staying within the remit of ‘self-defence’ by focussing their attacks more on the bellicose talk of annexations than the war itself, their opposition was a far cry from that of the internationalist wing of Liebknecht and Luxemburg, who had founded the Gruppe Internationale in 1915. Known as the Spartakusgruppe from 1916, and the Spartakusbund from November 1918 on, its influence may have been small,16 but its message was infectious. It strove to utilise the economic and political crisis created by the war to hasten the downfall of capitalist class rule.17

Naturally, the pacifistic speeches of some of the Reichstag deputies earned the scorn of many a Spartacist polemic. Yet whether they knew it or not, the logic of events was driving towards cooperation and unity in a new organisa-tion.

Against the backdrop of enormous disillusionment with the war, the SPD faced growing opposition from the left. The SPD right and its allies in the war cabinet and the German Imperial Army staff were unanimous - dissent could not be tolerated. The SPD daily Vorwärts, already twice censored for making vaguely critical comments about bread distribution, printed a letter from colo-nel general Mortimer von Kessel which spelled out that it would be banned if any of its articles broached the sensitive matter of class struggle.18 As a result, the activity of all critically-minded party journalists and editors of local party newspapers was severely restricted. For its part, the SPD leadership proceeded with caution, attempting to drive a wedge between the radicals and the more moderate, pacifistic opponents of the war by washing its hands of the former.

16. The Spartakusbund consisted of no more than a few hundred members, and the first edition of its monthly journal ‘Die Internationale’ had a circulation of around 9,000.17. This was fully in line with the policy adopted by the Stuttgart conference of the Second Inter-national in 1907. Following an amendment from Luxemburg and Lenin, this policy read: “If a war threatens to break out, it is the duty of the working class and of its parliamentary representatives in the countries involved, supported by the consolidating activity of the International [Socialist] Bureau, to exert every effort to prevent the outbreak of war by means they consider most effective, which naturally vary according to the accentuation of the class struggle and of the general political situation. Should war break out nonetheless, it is their duty to intervene in favour of its speedy termination and to do all in their power to utilise the economic and political crisis caused by the war to rouse the peoples and thereby to hasten the abolition of capitalist class rule.”18. EB Görtz (ed) Eduard Bernsteins Briefwechsel mit Karl Kautsky (1912-1932) Frankfurt am Main 2010, p24.

13

The significance of Halle

Thus in May 1916 Karl Liebknecht was sentenced and conscripted for his tire-less work in the Spartakusbund. Meanwhile Karl Kautsky, an inveterate peac-emonger, was able to continue editing the SPD theoretical journal, Die Neue Zeit. Just a year later, however, he would be removed.

Yet these attempts to sever the different elements of the opposition only partially succeeded. The incarcerated Liebknecht became something of a mar-tyr. The anti-war strikes in Berlin, Leipzig and other working class centres in 1916 and 1917 rallied around his name. With influential left lawyers like Hugo Haase deluged with cases in defence of anti-war activists and conscription ob-jectors, the different shades of the anti-war socialists entered into much more of a dialogue with each other. Most soon realised that the ‘war socialists’ were the common enemy.

When 20 rebellious deputies from the SPD parliamentary fraction refused to vote for further war credits in December 1915, they began to gain the ear of wider layers of the party. By March 1916, when Haase spoke out against the renewal of the state of siege and was supported by the parliamentary minor-ity, the 33 deputies were expelled from the fraction. By January of the next year, they were out of the party as well - their work in forming the Sozial-demokratische Arbeitsgemeinschaft (Socialist Working Group) in the Reichstag proved too much for the SPD right leaders Gustav Noske, Friedrich Ebert and Phillipp Scheidemann. Three months later, in April 1917, the USPD was born.

This realignment of the workers’ movement was set against the backdrop of a deep-seated desire for radical change. The kaiser’s regime was cracking under the weight of military failure and mass discontent.

The USPD and two revolutionsThe USPD split is to this day the largest in the long history of the SPD. Some 120,000 members defected to the new organisation. It was a veritable melange, including Luxemburg, Bernstein, Kautsky and Liebknecht. Its main slogan was still “peace without reparations and annexations”, which it thought could be achieved through mass pressure. The international bourgeoisie could be made to see reason. In response to their bureaucratic mistreatment in the SPD, the USPD favoured a decentralised approach. This tended to gloss over important differences within the organisation rather than resolve them - a defining fea-ture of the USPD throughout its short existence. Yet the USPD was about to be shaken by a series of world-historic events which would abruptly bring these internal contradictions to the fore and call its very existence into question.

For their part, the Spartacists were clear that they were only in the USPD as a way of influencing those elements breaking with Burgfrieden and war socialism. Others, like Emanuel Wurm, Kautsky and Bernstein, were at first strongly opposed to the formation of the USPD, precisely because they feared the growing influence of the radical left wing. Their rather limited aims were to achieve peace and to uphold the values of the old SPD. After much discussion in private, Bernstein and Kautsky eventually agreed that the struggle for peace

Head to head in Halle

14

had to come first, even if this necessitated temporarily working alongside the Spartacists.19

The USPD’s foundation was in many ways bound up with the Russian Revolu-tion. The fall of the tsar in spring 1917 had electrified public opinion in Germany and lifted the spirits of the German left. During the negotiations to found the USPD, Haase spoke of the “light coming from the east”.20 Kautsky wrote enthu-siastically about the possibility of socialist revolution, maintaining that it could be on the agenda if the peasantry - “the X, the unknown factor in the Russian Revolution”21 - could be won over.

But as the Russian Revolution gathered yet more momentum, tensions in-creased between the differing trends in the USPD. Soon the October Revolution would demand an unambiguous stance, as would the disintegration of the kaiser regime.

By late September 1918 Germany’s defeat was obvious to the military top brass, the emperor’s court and leading industrialists alike. General von Luden-dorff22 pressed for urgent action. He was clear: a military dictatorship was not on the cards - Spartakusbund and USPD rank and file agitation had made the armed forces unreliable. They had to broaden the government to include the SPD in what admiral von Hintze dubbed a “revolution from above” in order to head off a “Russian October”.23

Initially hesitant, the SPD leadership eventually decided to join the new coali-tion of Progressives, National Liberals and the Centre on October 4 1918. They were bought off with the promise of an equal franchise in Prussia and the resto-ration of the Belgian state, which would receive reparations. But this could not hold back the movement from below. On October 16 there were mass demon-strations under the slogan: “Down with the government, long live Liebknecht!” Then, on November 3, a sailors’ mutiny in Kiel made toppling the government a real possibility.

For the time being, the SPD kept its options open. On November 4 its execu-tive committee announced that the kaiser’s abdication was under discussion. Its supporters in the working class were urged “not to frustrate these negotiations through reckless intervention”. Calls to action by an “irresponsible minority”24 had to be rejected.

19. C Shorske German social democracy 1905-1917: the development of the great schism Harvard 1983, p314.20. Protokolle der USPD, Band 3, Berlin 1976, p98.21. K Kautsky ‘Prospects of the Russian Revolution’, Weekly Worker January 14 2010. For the pos-sible effects of this article on Vladimir Ilych Lenin’s ‘April theses’ see L T Lih ‘Kautsky, Lenin and the April theses’, Weekly Worker January 14 2000. 22. In August 1916 Paul von Hindenburg replaced Erich von Falkenhayn as chief of the general staff with Ludendorff as his coadjutor, continuing their partnership which had begun some time earlier. By mid-1917 Hindenburg and Ludendorff were running a highly centralised and militarised regime which had effectively taken over the civil government. 23. E Waldman, The Spartacist uprising of 1919 Marquette 1958, p70.24. J Riddell (ed) The German revolution and the debate on soviet power New York 1986, p38.

15

The significance of Halle

But the line could not be held. Bavaria was the first state to become a republic, declared by USPD member Kurt Eisner following a general strike on November 7. King Ludwig III abdicated and numerous other petty princes and fiefs were swept from power. By November 8, Dresden, Leipzig, Chemnitz, Magdeburg, Brunswick, Frankfurt, Cologne, Düsseldorf, Hanover, Nuremberg and Stuttgart had all fallen into the hands of the workers’ and soldiers’ councils.

On November 9 the regime was finished. The revolution had reached Berlin. A meeting of the USPD leadership had decided on a general strike and, although the Jägerbatallion [light infantry] was sent in by prince von Baden to suppress it, the soldiers refused to move against the crowd.

Von Baden hoped that the regime could be salvaged if the kaiser abdicated. He himself resigned as chancellor in favour of Friedrich Ebert, general secretary of the SPD. Ebert told him: “If the kaiser does not abdicate, then social revolu-tion is unavoidable. But I do not want it; no, I hate it like sin.”

Meanwhile, leading SPD member Phillipp Scheidemann had found out that Liebknecht was about to proclaim the socialist republic. He decided to act. Against Ebert’s wishes, Scheidemann declared the republic and that von Baden had given his office over to “our friend Ebert”, who would “form a government to which all socialist parties will belong”.

Almost at the same time, Liebknecht was indeed proclaiming the socialist republic.25 With the memory of Ebert’s and Scheidemann’s betrayals of August 1914 still in mind, he feared another betrayal. Liebknecht was clear: Ebert had to be ousted from power. At 8pm around a hundred of his supporters stormed and occupied parliament. Their plan was quite simple: tomorrow elections had to take place in every factory and every regiment in order to form a revolution-ary government.

While the workers’ and soldiers’ councils represented a burgeoning alterna-tive power, the two workers’ parties remained pivotal. Indeed, relations between them were to prove decisive at all levels.

The SPD’s behaviour can be explained by the fact that it essentially considered the revolution completed by November 1918. Germany had become a demo-cratic republic26 and peace had been restored. A ‘socialisation’ commission had

25. This reflected a more general tendency to voluntarism in Karl Liebknecht - the socialist republic was quite clearly not an immediate prospect. Another example of Liebknecht’s hastiness came on January 5 1919, when he and Wilhelm Pieck met with the USPD in Berlin and decided to set up a ‘revolutionary committee’ to take power in the capital. The resultant uprising is often known as the ‘Spartacist uprising’. Yet Pieck and Liebknecht took this decision against the wishes of the KPD(S) leadership, which had met on January 4 and rejected calls to seize power in the capital. 26. In Marxist terms, of course, Germany in 1918 was a long way from a ‘democratic republic’ in the sense of Engels’s understanding of popular rule embodied in the Paris Commune of 1871. Yet Karl Kautsky was of the firm conviction that the German working class had come to power in No-vember 1918. Going back to the preconditions of proletarian power he outlined in his 1905 work ‘Republic and social democracy in France’, his absolute collapse as a revolutionary theoretician and politician is clear. If the Kautsky who had written ‘Republic’ in 1905 was the same person writing in 1919, as opposed to the ‘renegade’ Kautsky who had disavowed what he once wrote, then he would have been in no doubt that the working class had not conquered power. To take just two of the

Head to head in Halle

16

been established, the right to vote for all men and women over 20 guaranteed, pre-war labour regulations reintroduced and an eight-hour day enforced.

With initial success, it sold itself to the population at large as a kind of care-taker government upholding ‘order’ before elections to a national assembly. This was conceived as the sole legitimate form of government, resting on the pillars of the old bureaucracy and the army supreme command.

Addressing the councils or trade union branches, SPD members would talk about how newly-won universal suffrage represented “the most important po-litical achievement of the revolution, and at the same time the means of trans-forming the capitalist social order into a socialist one, by planned accordance with the will of the people”.27 ‘Socialism’ was framed firmly within the capitalist constitutional order. Yet given the revolutionary turmoil, the concessions won by the SPD were considered the most that could be obtained by many in the trade union movement and the workers’ movement more generally. Following the agreement signed between SPD union leader Carl Legien and the big in-dustrialists, Hugo Stinnes and Carl Friedrich von Siemens, the trade union bu-reaucracy became positively hostile to notions of deepening and spreading the revolution. This influential layer formed another pillar of SPD support.

This in part explains another key feature of the SPD’s behaviour: its constant tendency to cite the danger of ‘putschism’, ‘Bolshevik chaos’ and ‘civil war’ to justify its dealings with the supreme command and its restriction of working-class self activity. Behind the rhetoric, SPD intentions were clear - not to arm the people, not to expropriate industry, but to use its political influence within the new order to secure improved living standards, voting rights, trade union negotiation rights, and so on.

The SPD was unsure whether the workers’ councils would cooperate with Scheidemann’s government or would themselves become an alternative centre of power. Thus it had to direct the councils into safe channels. Yet doing so re-quired left cover from USPD supporters. The USPD was therefore pushed into joining a provisional government. A major test for it.

The USPD rank and file were in many ways the ‘men of the hour’ in Novem-ber 1917. They had established strong roots, particularly with the militant shop stewards’ movement known as the Revolutionäre Obleute. But, given its divi-sions and its short existence, the USPD had no clear vision of what it wanted, no clear programme for German society. Distrust between the leadership of the USPD and the SPD ran deep, but the former comrades knew each others’ politics inside out. And the SPD was confident that it could win the softer lay-ers of the USPD -the ‘centrists’ - that way a descent into ‘Bolshevik chaos’ could be prevented. Ebert even implied, hypocritically, that he wanted Liebknecht on

criteria he outlines for the ‘commune ideal’ in his 1905 article, the powerful state bureaucracy of the old order remained intact and the army supreme command remained master of the situation - not the armed people. See B Lewis ‘Same hymn sheet’, Weekly Worker May 19 2011.27. Quoted in DW Morgan The socialist left and the German revolution: a history of the German Independent Social Democratic Party, 1917-1922, p129.

17

The significance of Halle

board - just hours earlier he had been resolutely committed to a parliamentary monarchy and SPD coalition with the Liberals and the Progressives.

Richard Müller, Ernst Däumig and Georg Ledebour were extremely suspi-cious of those so quick to leap from advocating a coalition with the bourgeoisie to advocating a workers’ government. They did not want to be used as a fig-leaf for SPD moves to call a snap general election, thereby nullifying the councils. Däumig, who later refused to take up a post in the war ministry, was clear: “the German revolution has only taken the first step - it must take many more.”28

Liebknecht insisted that government participation should be made contin-gent on all power being vested in the councils and on the immediate signing of an armistice. This was rejected by the SPD, which claimed that a “class dicta-torship” of the workers would be ‘undemocratic’. Only the people could decide on their government following properly organised elections - making it clear that the SPD wanted bourgeois parties on board.

A second round of negotiations - this time without Liebknecht in the USPD delegation - proved far more fruitful. The USPD accepted the invitation to enter government on the condition that bourgeois politicians would be there merely as “technical assistants”. The other condition was that the national as-sembly should not meet until “the gains of the revolution had been consolidat-ed”. This vague concession had counterrevolutionary implications, as the old state apparatus essentially remained intact. All this produced further strains in the USPD.

Liebknecht was emphatic. He would not join the proposed government with Ebert, a man who had “smuggled himself into the revolution”. So the new government was set up without Liebknecht, and consisted of three representa-tives, or people’s commissars, from each party: Ebert, Scheidemann and Otto Landsberg for the SPD; and Hugo Haase, Wilhelm Dittmann and Emil Barth for the USPD. However, the situation was in flux. The SPD was playing the role of both the heir to the old regime and the head of the Berlin Rat der Volks-beauftragten (Council of People’s Commissars).

Right from the outset the SPD was determined to marginalise the execu-tive council of workers’ and soldiers’ councils (Vollzugsrat), which had been elected at a 3,000-strong meeting of workers and soldiers in Circus Busch on November 10 1918.

Driven on by its radical minority, the Vollzugsrat saw itself as a kind of Petrograd Soviet. It declared that Germany was now a “socialist republic”, where power lay in the “workers’ and soldiers’ councils”. Such clowning was, of course, easily ignored by the SPD-controlled press. The Vollzugsrat was re-duced to radical rhetoric, having as it did no effect on the decisions of the Rat der Volksbeauftragten. In turn, the Rat der Volksbeauftragten had little control over the real day-to-day business of running the country.

None of the six people’s commissars was a departmental minister. Trusted

28. Ibid p136.

Head to head in Halle

18

socialists may have been assigned to keep an eye on the bureaucrats. But the results were farcical. At a time when the new government was colluding with the Entente imperialist states to keep German troops in Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia so as to contain the Russian Revolution, Kautsky - sent as a USPD rep-resentative to watch over foreign policy - was sent away to investigate historical documents on the origins of World War I! Business as usual, then, for foreign secretary Wilhelm Solf and his officials.

It was the same in other areas of government business too. The ‘socialisa-tion’ commission produced no results at all. The SPD members insisted that it was impossible to “socialise need”, and that socialisation could only occur on the basis of national reconstruction and stability.

Controlling the army also proved impossible. The people’s commissars re-fused to take measures against overbearing officers, which, after all, was one of the original impulses behind the revolution. Beyond a few token sackings and declarations on the right to display the red flag, the people’s commissars did nothing. The SPD’s approach of tinkering with the institutions of the old order ensured that they tolerated groups like the Freikorps on the Polish bor-der. Soon the supreme command would employ them to crush some of the German capital’s most militant working class strongholds.

Of enormous symbolic importance was the new ‘socialist’ government’s at-titude towards the Soviet Republic. The Russian delegation to the congress of workers’ and soldiers’ councils in Berlin on December 16 - which included former Soviet ambassador Adolph Joffe, as well as Nikolai Bukharin and Karl Radek - was turned away.29

The mass of the USPD membership came to oppose their party’s participa-tion in the provisional government. By equal measure, the attempts to convene elections to a national assembly as quickly as possible were rejected. The three USPD people’s commissars found themselves increasingly isolated from their membership.

There were growing calls for a USPD party congress - all were ignored. Yet the crisis in the party could not be averted. The final straw came on December 24 when the SPD commissars ordered general Lequis - a man well-known for his role in the suppression of the Herero uprising of 190430 - to launch an at-tack on the People’s Naval Division in Berlin without the knowledge, let alone the consent, of their fellow USPD commissars. Dittmann, Haase and Barth felt compelled to resign.

Despite this, the leadership still refused to heed calls for a party congress,

29. The minutes of the session of the Council of People’s Commissars of November 19 state: “Con-tinuation of the discussions on Germany’s relations with the Soviet republic. Haase advises dilatory progress … Kautsky joins with Haase; the decision would have to be postponed. The Soviet govern-ment would not last much longer, but would be finished in a few weeks …”30. Following an uprising against German colonial rule in South West Africa (modern-day Na-mibia), the German army drove the Herero people into the desert of Omaheke. Up to 100,000 of the native population then died of thirst and starvation. This has been regarded as the first act of genocide of the 20th century.

19

The significance of Halle

arguing that the coming January elections took precedence. The Spartakus-bund of Luxemburg and Liebknecht then decided split from the USPD and establish the Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands (Spartakus). In the words of a later KPD(S) leader Paul Levi, the split had “scarcely any influence” on the disaffected ranks of the USPD. Clearly, a premature move.

International realignmentsThe first few months of the revolution saw the SPD expand its mass base. Polling just under 38% in the January elections, it opted to join a bourgeois coalition government with the Centre Party and the German Democrats. This created real problems, with the SPD-led coalition dismally failing to deliver on many of its promises. For example, the eight-hour day had been a great achievement but it had been introduced without a corresponding wage in-crease - the average weekly wage of a worker fell to levels not seen since 1913.

Now in opposition, the USPD benefited from the resulting discontent. Be-tween November 1918 and March 1919 200,000 new members swelled the US-PD’s ranks. The KPD(S) remained in the shadows. But the USPD had failed to resolve its own crisis of identity. Governmental unity with the SPD had proved a disaster. So what next?

Eduard Bernstein’s best efforts to reunite the two wings of social democracy by taking up dual membership of both parties and establishing the ‘Central de-partment for socialist unification’ found little support beyond the most right-wing circles of the USPD. His hopes of proving that the “politics of negation and decomposition ... was worse than all of the SPD’s errors together”31 soon foundered. As was expected, this trajectory led him back into the SPD proper by May 1919.

But the USPD’s prospects of unity ‘to the left’ were also beset with problems. The KPD(S) was viewed with suspicion too. Following the turmoil of the so-called ‘Spartacist’ uprising of January 191932 its membership was scattered and subject to repression. Within months three of its best leaders - Luxemburg, Liebknecht and Leo Jogiches - were murdered by those with whom they had cooperated in the same organisation just a few years prior. The only reason that Paul Levi, by far the most talented of the remaining KPD(S) leadership, was able to escape being killed and take up the reins was because he was in prison when the killing spree began. It is thus unsurprising that many rank and file KPD(S) members drew understandable, yet erroneous conclusions: reject working alongside the SPD supporters of the butcher Noske in the unions and the factory councils, boycott the national assembly elections, and so on. But this did not win them much of a hearing with the USPD rank and file. Nor would it win them much of a hearing with the class more generally.

And by the USPD’s second congress in May 1919, a definite shift to the

31. H Krause USPD Frankfurt am Main 1975, p132.32. As discussed in footnote 25, the uprising was not the initiative of the Spartacist leadership.

Head to head in Halle

20

left occurred around the question of international organisation. A motion was passed, calling for the “reconstruction of the workers’ international on the basis of a revolutionary socialist policy in the spirit of the international conferences in Zimmerwald and Kienthal”33. However, the guarded wording of the motion was insufficient to clearly break with the plans of Kautsky and others to reconstruct the Second International at the Berne conference in February 1919.34 Now that the war was over, it was time to forgive and forget about the social chauvinism, participation in war cabinets and the urging of workers to slaughter each other.

Lenin and the Bolsheviks, who, in opposition to the USPD leadership, had constantly fought for the foundation of a new, purified international at the anti-war conferences like Zimmerwald and Kienthal, turned words into action in March 1919. Seeing that the Communist International was formed by very small forces, many in the USPD considered this move premature. Revealingly, the Communist International was not mentioned in the USPD’s resolutions at the May 1919 congress. Yet, having seen Kautsky’s and Haase’s conception of ‘so-cialist’ foreign policy in the November government, and having heard of plans to revive the Second International, USPD members increasingly changed their minds. Reflecting the new political trajectory of the USPD, in July 1919 the pro-Comintern radicals Curt Geyer and Walter Stöcker were elected to the party’s leadership.

In response to this and other such developments, Hilferding wrote a series of articles defending his commitment to a revived Second International. For him this involved reshaping the Second International on a (vaguely defined) social-ist basis. But these words did not amount to very much. The resolutions of the Second International’s Lucerne congress of August 1919, for example, did not demand a clear break with bourgeois coalitionism, and as such put no pressure on the SPD. Following this disappointment, many local USPD publications were of the view that backing a revived Second International was no longer an option. The demand for a revolutionary international grew daily. Yet what this exactly meant, and how it was to be achieved, was still unclear.

Come the USPD’s Leipzig congress of September 1919, these international issues were to dominate the agenda. Unity prevailed on domestic questions, and a new Leipzig ‘Action programme’ was decided upon. Although making nods in the direction of the ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’, the new programme was framed in a typically centrist way so as to smooth over differences and placate both of the USPD’s wings. This led Lenin to castigate the USPD’s growing left wing for combining, in an “unprincipled and cowardly fashion - the old preju-dices of the petty-bourgeoisie about parliamentary democracy with communist recognition of the proletarian revolution, the dictatorship of the proletariat, and

33. P Broué The German revolution 1917-1923 Chicago 2006, p337.34. As Eva-Bettina Görtz notes, by June 1920 Kautsky was seriously considering rejoining the SPD in the hope of once again editing the theoretical journal Die Neue Zeit. EB Görtz (ed) Eduard Bern-steins Briefwechsel mit Karl Kautsky (1912-1932) Frankfurt am Main 2010, pxiv.

21

The significance of Halle

soviet power.”35 For his part, KPD(S) leader Levi likened the new programme to a “lump of clay that one can make into a face or a gargoyle at will”.36

Unity evaporated when discussion turned to the international situation. Three positions were represented. For the left, Geyer and Stöcker in particular were clear: the USPD should immediately and unconditionally affiliate to the Communist International. Now that the USPD officially recognised the council system and the dictatorship of the proletariat, the USPD was moving towards Comintern, and affiliation was the next logical step. They criticised the narrow perspectives of the Second International, which appeared to see no further than the League of Nations.

Hilferding proposed a resolution which criticised Comintern and called for the formation of a new international alongside what he deemed the revolution-ary parties of the Second International. For him, Bolshevism needed “action” and thus unconditional affiliation would render the USPD “the whipping boy” of the Bolsheviks. The autonomy and independence of the USPD would be lost. At a time when the armies of counterrevolution were waging their campaign against Soviet Russia, when the masses were building solidarity in ‘Hands off Russia’ committees, Hilferding could only haughtily lecture that Russia was a “sinking ship” and tying the USPD to it would bring its imminent demise.

A middling position was represented by Georg Ledebour, who feared further splits in the movement. He wanted to work with the communists in the hope of overcoming the schism in the workers’ movement by creating an international of all ‘social revolutionary’ parties to resolve this matter alongside Comintern.

The debate was fierce. Karl Kautsky cut a sorry figure in his attempts to prop up Hilferding. His pious complaints about 6,000 government executions in Rus-sia during the civil war were countered head-on by Geyer, Stöcker and their comrades, reminding Kautsky of the siege unleashed on Soviet Russia.

Ledebour’s middling position won the day. Following a day of negotiations behind the scenes, the congress finally reconvened. Both Hilferding and Lede-bour had withdrawn their resolutions to propose a new, joint one which incor-porated substantial aspects of Ledebour’s speech. It called for a break with the Second International, naming Comintern as the only international the USPD wished to join. However, it called for “negotiations” between the parties of the Second International and Comintern, not immediate affiliation. This delaying procedure was clearly aimed at undermining Stöcker, who adamantly refused to withdraw his resolution for immediate affiliation. The tactic worked. Immediate affiliation was defeated by 170 votes to 111, and the ‘compromise’ motion passed by 227 votes to 54.

Yet the pro-Comintern left’s representation in the USPD structures also con-tinued to increase. With two opposed lists contesting the elections to the leading party bodies, the left list won 11 of 26 positions, along with four others who were

35. P Broué The German revolution 1917-1923 Chicago, 2006, pp345-6.36. R A Archer (trans) The Second Congress of the Communist International Vol I, London 1977, pp282-3.

Head to head in Halle

22

proposed by both lists. Writing in Kommunistische Internationale, Karl Radek celebrated the Leipzig congress as a “landmark” in the development of the Ger-man revolution”.37 He also took some KPD(S) members to task for not recognis-ing these changes within the USPD and the growth of a “communist” left. He argued that engaging with these layers was vital to the success of the German communists, who had to recognise that the USPD was no longer “the organisa-tion it was in 1918” and that engagement demanded “different tactics”.

In the immediate aftermath of the congress, some members of the USPD right initiated rumours of secret meetings between the USPD and the KPD(S), and de-cried the ‘influence of putschist agents’. Now, Comintern had to intervene from Moscow against the leftists in the KPD(S) and Levi had to assert his authority. Ultra-leftist and syndicalist illusions had become an obstacle to unification in a much bigger revolutionary organisation.38 Levi took the lead by expelling most of the leftists at the Heidelberg congress of October 1919; although it should be added that Comintern leaders Lenin and Karl Radek did not approve of Levi’s methods.39 The ‘lefts’ proceeded to form the Communist Workers’ Party of Ger-many (KAPD). But the USPD left and the KPD(S) still seemed a long way apart.

Comintern’s 2nd congressThe Weimar Republic’s continuing destabilisation and exposure to a backlash from the far right made the different attitudes towards Comintern within the USPD ever more incompatible.

The USPD continued to grow at the SPD’s expense. The latter’s record in gov-ernment, combined with its willingness to use the army and forces like the Frei-korps to suppress the council movement - both before and after the attempted March 1920 coup d’état led by Wolfgang Kapp and General Walther von Lüttwitz - resulted in a rapid decline in its support base. The organised working class, whose general strike had defeated the attempted putsch, flooded into the USPD. Between the January 1919 and June 1920 elections the SPD’s share of the vote fell from 37.9% to 21.6%, while the USPD’s increased from 7.6% to 18.8%. Once again, the SPD asked the USPD whether it would form a joint ‘workers’ govern-ment’. However, the USPD insisted that the only government it would join would be a socialist one with majority support.40 The Centre Party, the national-liberal

37. K Radek ‘Der Parteitag der USPD’ in Kommunistische Internationale No4, Amsterdam 1919, p129.38. Levi’s focus was quite clearly correct. In 1920 the membership of the KPD was around 50,000, whereas the USPD organised around 800,000 members.39. Although Charlotte Beradt describes Levi’s move as not that far removed from some of the tactics later employed by Comintern to split the west European parties, she states that it was “in-dispensable” to bring about rapprochement with the USPD left (C Beradt Paul Levi: ein demok-ratischer Sozialist in der Weimarer Republik Frankfurt 1969, p33). However, Lenin was clear in his opposition: “If the split was inevitable, efforts should be made not to deepen it, but to approach the Executive Committee of the Third International for mediation and to make the ‘lefts’ formulate their differences in a pamphlet” (quoted in P Broué The German revolution 1917-1923 Chicago 2006, p321).40. This remains a controversial decision. John Riddell cites Lenin, who argued that such a govern-

23

The significance of Halle

German People’s Party and the liberal German Democratic Party proceeded to form an unambiguously bourgeois government.

Comintern sought to turn up the heat. Having rejected notions of ‘interna-tional negotiations’ - the matter at hand concerned whether the USPD wanted to join it or not - the ECCI wrote several letters and articles to establish just what was going to actually be done. The USPD right’s prevarication soon became ap-parent. One ‘open letter’ from the ECCI went unpublished on rather spurious grounds: running such articles in the run-up to the elections could only assist the KPD. On another occasion a “lack of paper”(!) was blamed for the failure to print ECCI correspondence.41

The USPD right’s feeble excuses were running into the sand. Meanwhile, the impulse towards genuine communist party unity initiated by the Russian Revolution was starting to pay dividends. More and more sizeable parties were pledging support for the new international, from Norway to Italy. The USPD leadership felt it had no other choice: it had to go to Moscow for Comintern’s 2nd congress in July 1920.

Twenty-one communist parties across the world were officially present. To much fanfare, ECCI chair Grigory Zinoviev opened proceedings by proclaim-ing the death of the Second International and celebrating Comintern’s transfor-mation from the “propaganda society” of its founding congress of 1919, into a “fighting organisation of the international proletariat”.42 For Zinoviev, attaining this goal required “clarity, clarity and once more clarity”. Expressing the wish that “Soviet France” could commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Paris Com-mune in 1871, Zinoviev wondered what a Communist Party and a Communist International could have achieved in the heady days of 1871. But conditions were not ripe then. Now they were, and the 2nd congress was to clarify remaining political differences to create “one single Communist Party with departments in different countries”.43 All delegates were handed a copy of Lenin’s Left-wing communism and Trotsky’s Terrorism and communism. In their differing ways, the pamphlets tackled both the USPD and the KAPD. (The latter organisation’s two delegates did not stay in Russia long.) The congress was divided into a number of sessions: ‘The role of the Communist Party during and after the revolution’, ‘The national and colonial question’, ‘The conditions of admission to the Communist

ment was broadly analogous with the Bolshevik proposal to form a government of the Mensheviks, Bolsheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries in 1917. See J Riddell ‘The origins of the united front policy’ in International Socialism No130 (http://www.isj.org.uk/index.php4?id=724&issue=130#130riddell_6). Interestingly, the controversy over the ‘workers’ government’ question cut across the left-right divisions in the USPD, with Hilferding and Könen favouring negotiations with the SPD and Crispien and Däumig rejecting them. 41. Quoted in ‘An alle Mitglieder der USPD’ in Die Kommunistische Internationale No12, Summer 1920, p325. The letter appealed to the USPD rank and file to send its own delegates to Comintern’s Second Congress.42. R A Archer (trans) The Second Congress of the Communist International Vol 1, London, 1977, p187.43. Ibid p87.

Head to head in Halle

24

International’, etc.The sixth session saw the much-anticipated discussion on the conditions

of admission to Comintern. For some delegates like Dutch leftist David Wijnkoop, the very presence of large centrist organisations like the USPD and the French Socialist Party was tantamount to the liquidation of revolution-ary principles. Henri Guillbeaux was also opposed, because both organisations had not made formal applications to affiliate, but were there to establish the conditions of affiliation.

Yet Zinoviev was adamant that such organisations were not simply to be absorbed into Comintern as they were - that was the role of the conditions. Not seeking to engage with the USPD as a way of winning over 800,000 workers, “badly led as they are”, amounted to nothing more than a sectarian pose. “Un-der no circumstances … would this congress permit intellectual dishonesty, nor will it make the slightest concessions on principle”.44 Organising in the same party with forces who wavered on the cardinal questions addressed in the conditions would risk another collapse from within like in Germany or Hun-gary. Given the extremity of the situation, there was no time for patient politi-cal struggle within the new international. Soviet Russia was suffering under blockade and delegates at the congress followed the course of the Soviet-Polish war on a giant map hung on the wall. Meanwhile, Miklós Horthy’s troops ran wild in Hungary, massacring working class activists of all political stripes. The Finnish counterrevolution had, with the complicity of the German SPD, led to the butchering of around one-fifth of the entire working class. The British government was funding anybody and anything set on occupying and crush-ing Moscow and Petrograd.

Not that the ECCI was under any illusions that in and of themselves its proposed conditions represented some sort of ‘communist baptism’. Zinoviev reminded the delegates that “it is possible to accept 18,000 conditions and still remain a Kautskyite”. The ECCI had to follow up and monitor the practice of all the parties seeking to affiliate.

Drafted by Grigory Zinoviev, the 21 conditions were stringent. Leaders like Kautsky and Hilferding were named as traitors, from whom the workers’ move-ment should decisively break. The necessity of maintaining an illegal party ap-paratus alongside a legal one, which caused Dittmann some consternation, was uncompromisingly insisted upon. Ledebour made much of the question of the “autonomy” of the USPD as an organisation, which for Clara Zetkin simply amounted to a “German” technocratic/organisational fanaticism conditioned by the organisational prejudices of the Second International. 45

Published for the first time on August 24, the 21 conditions eventually agreed upon initiated much debate, particularly among the German, French and Italian parties. They were seen in different lights by the party functionaries

44. Ibid p10.45. C Zetkin Der Weg nach Moskau Hamburg 1920, p5.

USPD centre

25

The significance of Halle

on the one hand, and the membership on the other. Historian Robert Wheeler has, it should be pointed out, usefully distinguished between a “first and sec-ond wave”46 of responses in the USPD.

The first came from the party press, which almost entirely came out negatively. The same can be said of the USPD Reichskonferenz of September 1920, attended by the USPD central committee, Beirat (advisory committee), representatives of local party organisations, newspaper editors, Reichstag fraction members and representatives from the local state parliaments. Many old wounds were opened up in the course of a debate. Talk of ‘us’ and ‘you’ surfaced on both sides, with the debate polarising between those ‘for’ and ‘against’ Comintern and the Rus-sian Revolution. This conference of party officials voted against the conditions.

With the Halle congress only six weeks away, the USPD right was confident that its majority amongst the functionaries would be reflected in the party as a whole. The USPD left knew the membership better.

Mass USPD assemblies sprang up all over the country. The “second wave” had begun. The key representatives of both tendencies addressed hundreds of meet-ings, with members thirsting for the arguments. Pamphlets,47 bulletins and flyers were hastily produced. Party newspapers focused on the dispute. Local party organisations called congresses to decide their position on the 21 conditions. Resolutions were debated and adopted.

Disputes over organisational questions overlay the ideological battle, with the date for the coming congress proving particularly controversial. To the outrage of the USPD left, which did not have control of the party press and thus needed more time for the arguments to develop, the right succeeded in bringing the con-gress forward from October 24 to October 12. When it became clear that there was no space in Hilferding’s Freiheit, Däumig, Könen, Stöcker and Hoffmann wrote an ‘Appeal of the USPD left’ in the KPD(S) publication Die Rote Fahne, which criticised the early convocation of the congress.

The party leadership’s decision to hold a referendum to settle the composition of delegates at the forthcoming party congress marginalised the ‘centre’ current around those like Arthur Crispien and Toni Sender who sought to preserve the organisational independence of the USPD and use it as the basis for launching a new, separate international (a “bastard” international, in Radek’s words). This tendency was forced to bloc with the USPD right against what it perceived to be the ‘Moscow diktat’ (a derivation from the term ‘Versailles diktat’ often used then) of Comintern and its 21 conditions.

The gulf between the party functionaries and the membership was most evi-dent in Berlin. While all eight editors of Freiheit, naturally including Hilferding,

46. R F Wheeler USPD und Internationale: Sozialistischer Internationalismus in der Zeit der Revolu-tion Frankfurt am Main 1975, p233.47. Amongst others, Curt Geyer, Toni Sender, Karl Radek and Clara Zetkin wrote contributions. Not to be outdone, the SPD also chipped in, publishing a pamphlet with the rather long yet barbed title: Who is for splitting the workers’ movement? The USPD. Who is for uniting the workers’ move-ment? The SPD.

Head to head in Halle

26

opposed affiliation, 16 out of 18 USPD organisations voted in favour of the 21 conditions. This pattern was repeated nationally: in the referendum which se-lected the delegates to the Halle congress, 57.8% voted in favour of Comintern affiliation, 42.2% against.

This result revealed how isolated leaders like Dittmann had become. On returning from Comintern’s 2nd congress, he had penned a pamphlet entitled The truth about Soviet Russia. Intended to make the case against Comintern af-filiation, this pamphlet had precisely the opposite effect. The patronising tone, his condescending attitude towards the young workers’ state in general, and the “uncultured and ignorant” Russian peasantry in particular, merely revealed his contempt for the Russian Revolution itself.

This angered many USPD members, including those who were very sceptical about the 21 conditions.48 Class instinct alone led many to look to Comintern and, in the words of Curt Geyer, to prevent the development of a “holy alliance” of counterrevolutionary powers against the revolution.

Martov and ZinovievThis backdrop explains the significance of the Halle congress in the history of the workers’ movement. The run-up to the congress had seen a fervour of intense debate in the party press, meetings, union caucuses and the broader working class. Both sides engaged in such feverish agitation and propaganda that the USPD effectively ceased to exist in the months before the congress. Everything was subordinated to the factional struggle and getting delegates elected with mandates to support either faction.

The days preceding the congress brought precursors of what was to come. On October 9 leftwing USPD Reichstag deputies split from the party’s parlia-mentary fraction. At a regional congress in Stuttgart, those opposed to Comin-tern affiliation simply walked out following a dispute over the agenda. One day before delegates assembled in Halle, the right wing of the Lower Rhine USPD expelled Comintern supporters.

In such circumstances, it is hardly a surprise that there was such a charged atmosphere in Halle, where “two parties” were present, divided by a walkway in the middle of the hall “as if a knife has cut them sharply in two”.49 The spec-tators’ gallery at the back was packed for the duration. There were two chair-men, Otto Brass (left) and Dittmann (right).

On both sides of the hall were seated tried-and-tested leaders who had run illegal newspapers, languished in the kaiser’s jails for defeatist agitation amongst soldiers, and spent the last few years avoiding reactionary thugs and goons.

While the left had won a clear majority of delegates in the party referendum, the next five days of proceedings were not so much about those present at the

48. Wheeler cites an example where one of the party organisations in Berlin voted for the condi-tions “in spite of them”!49. G Zinoviev, Twelve days in Germany, printed in this volume.

27

The significance of Halle

congress as about those outside. This was not going to be a soporific talking shop, but a real battle for the hearts and minds of the movement. Militants from across the whole world looked on. It was here, in the furore of partisan cheering and electrifying speeches, cut-and-thrust polemics and killer points, that the fate of the German, and perhaps the international workers’ movement was fought out.

Könen, Stöcker, Hilferding, Däumig, Dittmann and Hoffmann all graced the platform. In addition, both USPD factions had canvassed for support in-ternationally, arranging for numerous speakers to address the congress: Marx’s grandson Jean Longuet, editor of the French Socialist Party’s newspaper, Le Populaire; Solomon Lozovsky, chair of the All-Russian congress of trade un-ions; Shablin (Ivan Nedelkov) of the Bulgarian communists’ central committee and many others. But two speakers, both from the Russian movement, were particularly anticipated.

The first was Julius Martov, the intellectually rigorous, if politically inde-cisive, leader of the Menshevik Internationalists.50 A co-founder of the Rus-sian Social Democratic Labour Party, he cut his teeth alongside Lenin in the St Petersburg League of Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Class and then on the editorial board of the underground newspaper Iskra (Spark). Breaking with Lenin and his supporters at the 1903 congress, Martov became one of the main leaders of Menshevism, renowned for his love-hate relation-ship with the Bolsheviks. Martov’s sophistication of argument and cutting po-lemics make him stand out from other Menshevik leaders like Fyodor Dan, Pavel Axelrod or Georgi Plekhanov.

Yet these were not the only attributes which distinguished him from other Mensheviks. He was often engaged in protracted battles within his or-ganisation, leading his biographer Israel Getzler to consider him an “eternal oppositionist”.51 While critical of those in the movement who had besmirched the banner of internationalism in supporting the imperialist war, he refused to go along with the Bolshevik call for a new International. Martov was fuming when, in April 1917, leading Mensheviks like Dan and Irakly Tsereteli took up ministerial posts in the new provisional government and committed them-selves to the continuation of the imperialist war. Yet once again he was not prepared to split his Menshevik Internationalists from the main Menshevik body. Despite some ideological convergence with the Bolsheviks in 1917, he recoiled from what he called their ‘putschist methods’.

50. Whether out of revolutionary bravado or not, Zinoviev did not seem too bothered by the pros-pect of debating Martov. Asked on the train to Halle what he thought of the latter’s attendance, he responded: “Just leave Martov to me. You’ll see” (quoted in: C Geyer Die revolutionäre Illusion: zur Geschichte des linken Flügels der USPD Stuttgart 1976, p219). According to Bukharin, a majority of politburo members were concerned that allowing Martov a visa to travel to Germany might throw a spanner into the works of Comintern. It was mainly due to Lenin’s insistence that they allowed him to leave for Germany (I Getzler Martov: a political biography of a Russian social democrat Cambridge 2003, p208).51. I Getzler Martov: a political biography of a Russian social democrat Cambridge 2003, p164.

USPD centre

Head to head in Halle

28

As part of his ‘socialist intervention’ policy for Soviet Russia - his attempt to create space for the non-Bolshevik left - Martov had been at pains to es-tablish contacts with what he deemed the socialist ‘centre’ in Europe. Writing from Soviet Russia, he encouraged those like Karl Kautsky, Victor Adler and Jean Longuet to write letters to Lenin and other Bolshevik leaders condemning the treatment of oppositionist forces. Martov further encouraged them to send party delegations and ‘fact-finding’ commissions to Russia.

Two such leaders had recently returned from Russia: Crispien and Ditt-mann. And it was they who invited Martov to speak at the Halle congress. They did so because Martov sought to preserve the organisational and pro-grammatic independence of the European parties from Comintern. Martov felt close to the USPD and its positioning between official social democracy and the Bolsheviks, seeing the USPD as the “backbone of that socialist ‘centre’ which alone would be capable of forming the core of a future International”.52

Thus his agenda was clear: a split would be the equivalent of condemning the USPD to the wilderness of groups and sectlets as opposed to real parties. The Bolsheviks were perilously basing themselves on the spontaneous, visceral anger of a population suffering from the privations of the war and the eco-nomic crisis53 and this perspective threatened the entire workers’ movement. His position in Halle could be summarised as: ‘Neither Moscow (Bolshevism) nor Berlin (SPD) but international socialism.’

The second eagerly-awaited speaker had come to fight the corner of the USPD left - Grigory Zinoviev. And on the third day of proceedings, Zinoviev, chair of the Executive Committee of the Communist International, stepped onto the Halle podium amidst cries of ‘Bravo’ and ‘Long live the Third Inter-national’.

At this point we need to digress briefly and make a few remarks about Zi-noviev. History, to put it mildly, has not been very kind to him. From histori-cal character sketches to Hollywood movies he is mostly remembered for his opposition to the Bolshevik seizure of power in October 1917, his ruthless ‘Bolshevisation’ of Comintern and his capitulation to his eventual killer, Jo-seph Stalin. As with other key Bolshevik figures who fell victim to the Stalinist counterrevolution (amongst others, Karl Radek, Nikolai Bukharin54 and Lev

52. Ibid p206.53. This was a common feature of Martov’s critique of the Bolsheviks throughout his life. After the failure of the December 1905 uprising Martov wrote to Axelrod: “at a time of political lull, the Bol-sheviks are bound to win, for the ‘spontaneity’ of revolution works for them; the limited conscious-ness of ‘conscious’ workers and the cursed, lifeless psychology of ‘kruzhkovshchina’ [little activist circle mentality] and ‘putschism’ which thrives in the underground works for them” (quoted in I Getzler Martov: a political biography of a Russian social democrat Cambridge 2003, p113). This quote provides further vindication of Lars T Lih’s research: the Mensheviks were characterised by their ‘worry about the workers’.54. Both Radek and Bukharin played a part in shaping developments in Germany. Unfortunately, the latter seems to have had visa problems and thus could not travel to Germany. In the important run-up to the Halle congress, the former wrote a pamphlet against Hilferding, Crispien and Ditt-mann, accusing them of saying the same things as Scheidemann and acting as the “last guard of the

29

The significance of Halle

Kamenev) it would appear that Zinoviev was not only physically liquidated by Stalinism, but historically too.

Both the far left and the academy have tended to base their interpretation of the Russian Revolution and its degeneration almost exclusively on the deci-sions and actions of Lenin, Trotsky and Stalin.55 Not only does this downplay the role of the masses, it also fails to grasp the significance of the Bolshevik Party and its role in developing articulate, dedicated leaders. As such it often reduces other leading Bolsheviks, and indeed the masses themselves, to mere minions of the ‘great leader’, Lenin. Understandable for cold war warriors or those in thrall to the ‘cult of the personality’, but utterly insufficient in terms of historical analysis.

As an organisation determined to turn the world on its head, the Bolsheviks sought to ‘bring the revolutionary message’ to the people. Zinoviev particu-larly excelled in this. Indeed, as unfair as some of the historical accounts are to him, many contemporary records pay testament to his strengths as an agitator and an organiser. Anatoly Lunacharsky was in no doubt: Zinoviev’s speeches “are not as rich or as full of new ideas as the real leader of the revolution, Lenin, and he cannot compete in graphic power with Trotsky”, but apart from those two, “Zinoviev has no equals”.56 Trotsky had many criticisms of Zinoviev, but he too stressed Zinoviev’s “range of intellect and will”, his deep and unreserved “devotion to the cause of socialism”. 57 As the leader of the new Third Interna-tional, Zinoviev achieved something like celebrity status, from Berlin to Baku.

Zinoviev first met Lenin as a student in Switzerland in 1903. Siding with the Bolsheviks in the RSDLP split, he soon proved his revolutionary commitment. In 1905 he worked on the party journal Proletary and agitated amongst the Petrograd metal workers. Voted onto the central committee in 1907, he was arrested within a year. Released on health grounds, he was soon in Switzerland again. That he represented the Bolsheviks at the Zimmerwald anti-war confer-ence of 1915 pays testament to one of his greatest qualities: his ability to speak to hostile audiences and staunchly defend Bolshevik views against opponents and detractors.

Most of his writings remain closed off from an English-speaking audience, but it can certainly be agreed that he lacks the depth, nuance and sophistica-tion of a Trotsky or a Lenin. It is his strengths as an agitator and orator, his abil-

Whites” (K Radek Die Masken sind gefallen Berlin 1920, p10). Unfortunately, the pamphlet did not arrive in time for the congress. Radek, who had done a lot of work in the West European Bureau of Comintern, was not present at Halle. He had been removed from the secretariat in August 1920 for opposing the presence of the KAPD at Comintern’s 2nd congress. However, he did represent Comintern at the fusion congress of the new, united KPD in December 1921. I thank comrade Ian Birchall for pointing this out.55. The title of Bertram Wolfe’s study, Three who made a revolution is a case in point. 56. A Lunacharsky Revolutionary silhouettes: Grigorii Ovseyevich Zinoviev (http://www.marxists.org/archive/lunachar/works/silhouet/zinoviev.htm). 57. L Trotsky Kamenev and Zinoviev (http://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1937/xx/kamzinov.htm).

Head to head in Halle

30

ity to respond to real people’s concerns and to tell compelling narratives, that distinguish him. So even though Lenin had called for Zinoviev’s expulsion fol-lowing the latter’s public opposition to the seizure of power in 1917, Zinoviev soon took up extremely important positions in the new workers’ state: eg, chief party spokesman in the Trade Union Central Council, president of the Petrograd Soviet and chair of the Executive Committee of the Communist International.

His intervention as ECCI chair at the Halle congress is perhaps his great-est, often overlooked, accomplishment.58 Readers can judge for themselves, but surely even his most determined detractor must admit that his speech sparkles with passion, wit and intelligence.

One of Zinoviev’s great advantages in Halle was his command of German. As the reader will see, in the opening lines of his speech he asks the congress to exercise as much restraint as possible in heckling because of his linguistic limitations, but in reality he was more than capable of dealing with the whole event. Geyer, who officially welcomed Zinoviev in Berlin and accompanied him on the train to Halle (with a pistol in his breast pocket as protection) describes Zinoviev’s German as “not completely without error or accent, but incredibly fluent, speaking at a speed considerably greater than my own, and with a diction that appeared to know nothing of commas or full stops.” Geyer was also struck by Zinoviev’s “high, somewhat feminine” voice. 59

Zinoviev’s address has very few equals in the history of the workers’ move-ment. Speaking for over four hours in his second language, he shook German society to its foundations.

He mesmerised the delegates on both sides of the hall: impressing even the staunchest supporters of the USPD right, casting seeds of doubt into those who were wavering, and even winning over some of them to the left.60 His speech both shocked and impressed the German bourgeois press, which de-scribed him as “the first orator of our century”. It certainly lacks some of the finely tuned style and carefully-selected words and phrases often associated with great speech-making. Yet what marks it out is that much of it was off-the-cuff. Time and again Zinoviev responds to questions and interjections, includ-ing from some of European social democracy’s leading figures.

This is precisely what makes the Halle congress so extraordinary. The steno-graphic record is in parts extremely difficult to follow due to the myriad inter-