COVID-19: Tackling A Likely Fourth Wave - Aljazirah Nigeria ...

Multi-sited territory, territorial complexity and territorial postmodernity: A relevant conceptual...

Transcript of Multi-sited territory, territorial complexity and territorial postmodernity: A relevant conceptual...

MULTI-SITED TERRITORY, TERRITORIAL COMPLEXITY AND TERRITORIAL POSTMODERNITY: A RELEVANT CONCEPTUALTOOLBOX FOR TACKLING CONTEMPORARYTERRITORIALITIES?Frédéric Giraut

Belin | « L’Espace géographique »

2013/4 Volume 42 | pages 293 - 305 ISSN 0046-2497ISBN 9782701180892

This document is a translation of:--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Frédéric Giraut, « Territoire multisitué, complexité territoriale et postmodernité territoriale : desconcepts opératoires pour rendre compte des territorialités contemporaines ? », L’Espacegéographique 2013/4 (Volume 42), p. 293-305.--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Available online at :--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------http://www.cairn-int.info/article-E_EG_424_0293--multi-sited-territory-territorial.htm--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------The English version of this issue is published thanks to the support of the CNRS--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

How to cite this article :--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Frédéric Giraut, « Territoire multisitué, complexité territoriale et postmodernité territoriale : desconcepts opératoires pour rendre compte des territorialités contemporaines ? », L’Espacegéographique 2013/4 (Volume 42), p. 293-305.--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Electronic distribution by Cairn on behalf of Belin.© Belin. All rights reserved for all countries.

Doc

umen

t dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.c

airn

-int.i

nfo

- - G

iraut

Fre

deric

- 8

6.21

8.8.

133

- 19/

05/2

015

22h2

6. ©

Bel

in D

ocument dow

nloaded from w

ww

.cairn-int.info - - Giraut Frederic - 86.218.8.133 - 19/05/2015 22h26. ©

Belin

Reproducing this article (including by photocopying) is only authorized in accordance with the general terms andconditions of use for the website, or with the general terms and conditions of the license held by your institution, whereapplicable. Any other reproduction, in full or in part, or storage in a database, in any form and by any means whatsoeveris strictly prohibited without the prior written consent of the publisher, except where permitted under French law.

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org)

Doc

umen

t dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.c

airn

-int.i

nfo

- - G

iraut

Fre

deric

- 8

6.21

8.8.

133

- 19/

05/2

015

22h2

6. ©

Bel

in D

ocument dow

nloaded from w

ww

.cairn-int.info - - Giraut Frederic - 86.218.8.133 - 19/05/2015 22h26. ©

Belin

ABSTRACT.— This paper discusses therelevance of the concept of “multi-sitedterritory”, proposed for the specification ofspatial entities associating non-contiguousplaces sharing a coherent territoriality.Such a concept would be in accordance withthe relational nature of socio-spatialanalysis, challenging the “territorial trap’’and its container methodologism resultingfrom the modern way of designatingregions. For this reason, it seems essentialfor us to address simultaneously theconcept of “territorial postmodernity”related to the context which makes itpossible to conceive of “multi-sitedterritory” and the concept of “territorialcomplexity” pertaining to the simultaneousproduction of territories with differentnatures. The analysis of noteable SouthAfrican territorial experiences illustrates inexacerbated form each of these conceptsand the political contradictions that theyexpress.

MULTI-SITED TERRITORY, NETWORK,POSTMODERNITY, SITUATION, SOUTH AFRICA, TERRITORIAL COMPLEXITY,TERRITORY

RÉSUMÉ.— Territoire multisitué,complexité territoriale et postmodernitéterritoriale : des concepts opératoires pourrendre compte des territorialitéscontemporaines ? — Il s’agit de discuter la pertinence du concept de « territoiremultisitué » pour désigner certains espacessans continuité spatiale et dont la territorialité repose sur l’assemblagefonctionnel de plusieurs lieux. L’affirmationd’un tel concept s’inscrirait dans le mouvement de reconnaissance du caractère avant tout relationnel deterritorialités contemporaines qui peuvents’affranchir des contraintes de fixité,d’exhaustivité et d’exclusivité assignéesaux territoires conçus dans le cadre de la pensée et des pratiques relevant de la modernité. Pour cette raison, il noussemble indispensable d’envisagersimultanément le concept de« postmodernité territoriale » qui désigne le contexte qui permet de concevoir le « territoire multisitué », et celui de « complexité territoriale » relatif à la production simultanée de territoires denature différente. Les riches expériencesterritoriales sud-africaines permettent detester la pertinence et la compatibilité de ces expressions.

COMPLEXITÉ TERRITORIALE,DISCONTINUITÉ, POSTMODERNITÉ,RÉSEAU, SITUATION, TERRITOIREMULTISITUÉ, AFRIQUE DU SUD

Preamble

This article is the outcome ofa request made to the author byGeneviève Cortes to introduce aseminar on the expression “multi-sited territory”, its potential usesand eventual heuristic value. Theproposal sounded like it could bea possible response to a concep-tual requirement: the need to esta-blish a concept by sharing andcomparing knowledge obtainedfrom research on territoriality as apolitical relationship with space aswell as the need to reason interms of relations rather than interms of continuity and unicity.One could mention here therecent admission of disarray byClaude Raffestin who feels thathis definition of territoriality,despite being flexible and com-plex, is called into question by thedeterritorializing power of money.This may not result in theresearch on collective territorialitybeing abandoned but lead to a

EG

2013-4

p. 275-287

Frédéric GirautUniversity of Geneve

Department of Geography, Unimail40 boulevard Pont d’Arve

1211 Geneve 4, [email protected]

Multi-sited territory, territorial complexity and territorialpostmodernity: A relevant conceptual toolbox for tacklingcontemporary territorialities?

@ EG2013-4

275

Doc

umen

t dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.c

airn

-int.i

nfo

- - G

iraut

Fre

deric

- 8

6.21

8.8.

133

- 19/

05/2

015

22h2

6. ©

Bel

in D

ocument dow

nloaded from w

ww

.cairn-int.info - - Giraut Frederic - 86.218.8.133 - 19/05/2015 22h26. ©

Belin

more selective and differentiated conception depending on the players and their position(autonomy) in the system1. As far as I am concerned, this need comes from studyingsuccessive stages of South African territorial engineering and the resulting relationshipswith space. They baffled me with respect to fixist approaches, approaches whichconsider territory merely as places of residence or reproduction zones, failing toacknowledge complex territorialities which assemble these places and zones to formspatial systems of governmentality which could be used as tools of oppression,emancipation or simply governance, whether explicit or otherwise.

This paper is thus the first elaboration of a set of spontaneous reflections. It aimsto evaluate the utility of the expression in certain contemporary research on territoryand territoriality with respect to a triumphant and concealing modernity. It aims toassess its utility as compared to other available expressions and open up avenues byhelping to identify and formulate complex spatial realities that are defined by theirnature which is relational, evolutive and trans (translocal, transregional, transnationaland/or transscalar), all at the same time. It might often seem allusive because of itsdesire to encompass a wide range of different cases and different aspects of the proble-matic. It is not a fully developed synthesis but is above all, a discussion paper, whichaims to contribute to a theoretical, semantic and forward-looking debate.

Introduction

Understanding contemporary mutations in individual and collective territorialitiesrequires one to use various concepts. In fact, the characteristics and forms of thesemutations affect the “territorial puzzle” (Grataloup, Margolin, 1987), a puzzle of poli-tical and cultural territories as well as networks of places forming social and economicspatialities defined by a large variety of relationships with extent and duration(Debarbieux, 2006). They thus create and reveal territorial complexity.

The incompatibility of the areolar and reticular dimensions for considering terri-torialities seems to be refuted (Offner, Pumain, 1996; Vodoz et al., 2004; Macleod,Jones, 2007; Painter, 2007; Allen, 2009; Vanier, 2009; Harrison, 2010). In otherwords, the antagonistic vision of the topographical and topological realities that wouldassign territory as an exclusive expression of the areolary and the topographic is outdated.Therefore, the creation of an expression that could be a concept to include the notions ofterritory-network and discontinuous territory would be welcome. We will examinethe importance and the positioning related to the notion of “multi-sited territory”proposed in geography by Geneviève Cortes and Denis Pesche after it had been usedin anthropology.

Let us look first at the positioning of this notion with respect to the analysis ofthe overcoming of territorial modernity and the analysis of territorial complexity.South African territorial engineering is good for conducting field tests on the impor-tance of using these expressions to describe various aspects of manifold, heterogenousand dynamic territorialities. The South African case has a heuristic range in politicalgeography especially on issues related to territoriality. In fact, through its exacerbationand profusion in the domain of territorial govermentality, it makes it possible to askgeneral questions and test concepts meant to summarize complex territorial practicesand realities. Finally, we will try to see the contributions and the limitations in the useof the expression from the perspective of a political geography.

1. “The definition ofterritoriality that I havebeen in the habit of givingis growing outmoded, butbefore going any further, I should recall it:territoriality is the totalityof relations that humansmaintain with exteriorityand alterity, with theassistance of mediators,for the satisfaction of theirneeds, towards the end ofattaining the greatestpossible autonomy – that is, the capacity tohave aleatory relationswith their physical andsocial environment –taking into account the resources of thesystem. This definition isin part outmoded, becauseit is no longercontemporaneous withthe situation in which we evolve. The mediatorsare no longer reallychosen, but are a functionof money, of the moneyavailable for such andsuch an individual, forsuch and such a collectivity. The pyramidof needs is broken, and many no longer evenknow that such a thingexisted. It is enough to saythat autonomy no longerhas the same full senseand that it only continuesto exist for a privilegedminority and that thereare no more aleatoryrelations for the worst offamongst us.” (Raffestin,2012, p. 139).

© L’Espace géographique 276

Doc

umen

t dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.c

airn

-int.i

nfo

- - G

iraut

Fre

deric

- 8

6.21

8.8.

133

- 19/

05/2

015

22h2

6. ©

Bel

in D

ocument dow

nloaded from w

ww

.cairn-int.info - - Giraut Frederic - 86.218.8.133 - 19/05/2015 22h26. ©

Belin

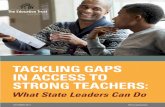

Overcoming territorial modernityTerritorial modernity strived to find a basis in rationalizing principles and unidi-

mensional functionnings (Anderson, 1996; Penrose, 2002; Antheaume, Giraut, 2005;Retaillé, 2005). It thus adopted management technologies corresponding to a fewsimple principles: exhaustiveness, exclusivity and connectivity. This was done to prepare,on one hand, demarcated and interlocked territories of the nation-state and localgovernment and, on the other hand, living areas based on a Fordist economy associatingcentre and periphery (table 1). Incidentally, it led to a “methodological territorialism”(Scholte, 2000) that exaggerates the effects of politico-administrative “containers” insocial sciences (Agnew, 1999, 2010; Werlen, 1993). Through this reference to acontainer associated with the “territorial trap”, which was widely adopted subsequently,Benno Werlen, John Agnew and Jan Aart Scholte, alluded to the bias in geography andinternational relations which involves taking as objects and considering as majorsubjects, entities which are in fact hegemonic analysis units due to the statisticalgeographical frameworks (NUTS: Nomenclature of territorial units for statistic) basedon state administration units. Stuart Elden (2010a and b), meanwhile, incorporatesterritory into a combination of economic (land) and strategic (terrain) control accor-ding to techniques related to the historical context where modern cartographical andstatistical reason was just a modality among many others, but one which was veryactive in our contemporary representations and practices.

The advent of variable geometry and reticularity is at the core of the major muta-tion in relationships to space and territory fabrication. This mutation is about multiplechanges that affect individual and collective mobile practices in technico-economiccontexts that destroy the precise interlocking of levels. At the same time, ideologies thatcreate and legitimize communities and collectivities govern their relationship withspace on complex and paradoxical bases, articulating the local and the global againstthe backdrop of major players such as the Stateand the major industrial concerns repositio-ning themselves.

Apprehension of territorial mutations isalso a question of analytical tools. Theconcepts used to perceive and interpret theserealities make it possible to understand someof their dimensions and their application tocertain objects (Paasi, 2002; Macleod, Jones,2007; Jessop et al., 2008; Painter, 2008). Forthis purpose, it can also be estimated thatcontemporary concerns based on mobility andcomplexity have a configurating effect.

Proposals of “territory-network” (Bakisin Dupuy, 1991; Offner, Pumain, 1996) and“archipelago type territory” (Viard, 1994;Veltz, 1996), as well as reactivation by JoePainter (2007) of the figure of the “rhi-zome2”, one of Gilles Deleuze’s (1980)favourite terms, made it possible to consideremerging forms or reconsider neglected

Frédéric Giraut277

Modernity Pre or postmodernity ?Mono-activity, mono-residence Pluri-activity, pluri-residenceCommuting CirculationExodus

FragmentationCentre-periphery Emergence

AssemblageHinterland Hinterworlda. Economic and social territorialities: mutation of practicesProximity RelationTopographical TopologicalConnexity Connectivityb. Mutation of functioning or modes spatial apprehensionFixed border Fuzzy border

Buffer zoneExhaustiveness Corridor, enclave, exclave

NetworkTransfrontierness/crossborderness

Exclusive sovereignty Shared sovereigntyZoning Territorial initiativec. Politico-administrative puzzle: mutation of territorial engineering

Table 1/ Territorial postmodernity: Contemporary mutations of principles of territorial

organization, functioning and apprehension

2. A figure alreadyreproduced by JacquesLévy, but in order tooppose it to that ofterritory (Lévy, Lussault,2003).

Doc

umen

t dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.c

airn

-int.i

nfo

- - G

iraut

Fre

deric

- 8

6.21

8.8.

133

- 19/

05/2

015

22h2

6. ©

Bel

in D

ocument dow

nloaded from w

ww

.cairn-int.info - - Giraut Frederic - 86.218.8.133 - 19/05/2015 22h26. ©

Belin

forms. They are based on the analysis of technical network territoriality or that ofeconomic and social interaction places. They however remained at the stage of adescriptive notion or analogy. Denise Pumain (2012) today explicitly considers theconcept of territory as “a continuous and bounded geographical area (or a set ofplaces that are more closely related: ‘network type territory’)” that can include“demarcation forms ranging from inclusion in boundaries (a fairly recent representation)to sets composed of several pieces (diaspora territories, for example) or restricted tonetworks (multinational companies, individual territories, etc.)” (p. 61).

The new proposal made with the expression “multi-sited territories” goes on tocomplete the range of francophone expressions that make it possible to describe,interpret and conceptualize contemporary mutations and innovations affecting terri-torialiaties. More specifically, there are expressions of “territorial complexity”(Giraut, Vanier, 1999; Moine, 2006) and “post-modern territoriality” (Anderson,1996; Newman, 1999; Antheaume, Giraut, 2005).

Territorial complexity emphasizes the simultaneous deployment of various terri-torialities which come under relationships to space corresponding to various rationalesand practices, which in turn have already increased in scalar terms. There are, notably,policy-related territorialities (in the sense of policy and polity, which go beyond thestrictly political aspects in politics) which require an exclusive demarcation and a certainfixity in time and space in order to define the scope of the exercise of power in terms ofcontrol and/or political representation (Lévy, 1994). Besides, there are individual andcollective socio-economic territorialities, which overcome container constraints (conti-nuity, fixity, demarcation) by using a set of complementary spaces, reproduction ordependence spaces and opportunity or commitment spaces (Cox, 1997).

“Territorial postmodernity” has something to do with the mutation of concep-tions. We propose it not as a stand which would involve adopting an approachfocused on differences, deviations from the norms and promotion of subalternateor dominated conceptions but as a subject pertaining to emerging and renewedprinciples of social and political relationships to space.

With these three expressions, it would be possible to have a set of notions thatallows us to understand: 1) mutation of principles (territorial postmodernity), 2)mutation of forms (multi-sited territories) and 3) complex systems that are esta-blished by virtue of, on the one hand, territorial production originating from themutation of principles and forms and, on the other hand, conservation of territorialartefacts based on principles of modernity (territorial complexity).

The purpose of these proposals is firstly to attempt to adapt and specify thefundamental concept of territory without leaving it to the “modern” context of itsappropriation by geography but by considering its capacity to understand emergingor submerged spatialities. The process is part of a “raffestinian” approach to territorythat deals with the deterritorialization-reterritorialization process by consideringterritoriality in a dynamic manner3 (Raffestin, 1980, 1986).

These expressions also allow us to re-examine spatial and territorial modernity,not only in the form of a rationalizing digression but also as a fundamentally hybridrationality. The table contrasting principles and forms is merely a convenient tool fordifferentiating what may be considered as various paradigms that dominate successivelybut are never exclusive.

3. “The very fact that theregion is not more than adiscourse shows quitewell that we have nowshifted to a temporizedterritoriality, that is, asystem of relations thatdepend on the variationand quality of informationin a given territory”(Raffestin, 1986, p. 184).

© L’Espace géographique 278

Doc

umen

t dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.c

airn

-int.i

nfo

- - G

iraut

Fre

deric

- 8

6.21

8.8.

133

- 19/

05/2

015

22h2

6. ©

Bel

in D

ocument dow

nloaded from w

ww

.cairn-int.info - - Giraut Frederic - 86.218.8.133 - 19/05/2015 22h26. ©

Belin

Three expressions for describing spatial structures and dynamicsof post-apartheid South Africa

A great deal of research has shown how South Africa, with its successive waves ofsettlements followed by its various apartheid policies, was marked by radical politicaland economic projects that have established efficient long-term segregationist territo-rial engineering (Christopher, 1994, 2002; Antheaume, 1999; Ramutsindela, 2001;Giraut, Vacchiani 2009, 2012; MacCarthy, Bernstein, 1998). This generates originalspatial structures and practices at different scales that overcome modern territorialityprinciples to a very large extent.

In fact, these territorial reorganizations established segregationist residentialzones and resource exploitation zones with interplay of assignment, different statusand organization of mobility. One of the characteristics of spatial apartheid systems isthe systematization of buffer zones at various levels (fig. 1). At the agglomeration level(Davies, 1981), they are found between townships reserved for subordinate groups ofnon-European origin and the part of the city which includes Central Business District(CBD) and rich suburbs with local government institutions. At the regional level, theyisolate population concentrations situated beyond former Bantoustan frontiers.

The policy of homelands or Bantoustans was conceived and presented as aninternal decolonization policy with the creation of new pseudo-independent States forcommunities of African origin where they would exercise their political rights. Thepurpose of forced movement and restrictions on residential mobility was to restrict thefamilies to the homelands and limit their settlement in South African cities. From thisradical policy arose urban fragments projectedbeyond the frontiers of former reserves that havebecome assigned homelands while remaining closeto the South African cities. These border humanconcentrations can be found a few kilometresfrom the cities but are functionally dependent onthem or industrial zones established close to theBantoustans to exploit labor.

Inherited spatial structures certainly demons-trate a strong momentum in the post-apartheidcontext of a highly unequal society. Emerging fromapartheid, public redistribution action served firstto ensure justice for the peripheries in terms ofaccess to basic services (Giraut, Maharaj, 2002).Residential and economic socio-spatial order was,however, not overturned, with priority given tosupporting growth by promoting sites, sectors anda class of entrepreneurs likely to attract foreigndirect investment.

In this context, South African cities remainhighly fragmented spaces within which individualsand groups adopt spatial practices based on visitsto discontinuous, physically separated and largelyexclusive places. While the pass system disappearedwith the end of apartheid, growth in individual and

Frédéric Giraut279

Towships

? ?

?

Townships

Buffer zone

Buffer zoneBuffer zone

Buffer zone

CBD

CBD

CBD

CBD

TowshipsTowships Municipality

HomelandHomeland

Municipality

Municipality 1

Municipality 2

Town

4. Post-apartheid municipality

Source: Giraut, 2005. ©L’Espace géographique, 2013 (awlb).

3. Post-apartheid transitional municipality

1. Apartheid city 2. Apartheid municipality

Suburbs Suburbs

Suburbs

TownshipsTownships

Townships

Suburbs

Fig. 1/ Complex system of South African urban areas andthe series of arrangements meant for their governmentThe buffer zone can be several hundred metres to several kilometreswide according to the size of the agglomeration and the urbanfragments, which developed beyond the frontiers of the formerBantoustans, can be at a distance of several tens of kilometres from themain agglomeration. Municipality boundaries are represented by greendots and boundaries of former Bantoustans or homelands by red dots.

Doc

umen

t dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.c

airn

-int.i

nfo

- - G

iraut

Fre

deric

- 8

6.21

8.8.

133

- 19/

05/2

015

22h2

6. ©

Bel

in D

ocument dow

nloaded from w

ww

.cairn-int.info - - Giraut Frederic - 86.218.8.133 - 19/05/2015 22h26. ©

Belin

© L’Espace géographique 280

collective security-related confinement continuously refreshes the extreme fragmenta-tion of living areas based on more or less bounded places that are nonetheless functio-nally and socially related in largely watertight networks. To describe these living areas,the expression “multi-sited territory” is highly welcome given that it makes it possibleto apprehend highly coherent spatial systems whose entities are dispersed but arefunctionally related in a space produced politically and historically in a differen-tiated way for various segments of the society. An old advertisement, but one thatannounces a new self-produced segregationist order, illustrates clearly the nature ofthese multi-sited urban territories (photo 1).

In the spatial system proposed here, the various residential areas are completelyforeign to one another. They are associated with different production spaces to formdifferentiated and exclusive territories composed of sets of places. The Central BusinessDistrict is equated with the centrality visited frequently by car-owners and thus asso-ciated with residential areas of affluent motorists. It is effectively so in its verticaldimension: underground parking and associated office towers are connected. But thisCentral Business District is also visited horizontally. A small group from townships andmigrants from central neighbourhoods occupy public spaces for informal and popularcommercial activities. Another territoriality thus coexists in the same central position asthat of the business world but in association with other places.

Functional activity areas are socially extremely specialized: Central BusinessDistrict towers, utility shopping centres, mining and industrial zones, streets in thecity centre. Exchanges beween people from different socioprofessional categoriesare restricted to certain places and certain moments. It is elsewhere that rare areasof intersection between various socio-spatial networks can be found such as the

Photo 1/ ‘‘You should have been there and you are here.With NOGo Zones, if you’re not supposed to be there, we’ll knowabout it’’Advertisement published in the South African press in 2002 for an innovative South-African product. NoGo Zones is a device with a built-in exclusion zonesprogramming. In case your vehicle ventures into pre-defined prohibited areas, the exchange is warned with the possibility of precise localization and dispatch ofaid. To demonstrate the utility of the product, the metropolitan space is reproducedand you are projected there in an imaginary risk situation. In fact, this representationproposes a beautiful centre-periphery model. You are supposed to be close to the Central Business District (background) with its recognizable skyline. In reality, the communities that this advertisement targets live in affluent suburbs and oftenvisit the new office neighborhoods and shopping malls nearby. You have beenkidnapped and you find yourself at the other end of the agglomeration, after even the townships (middle plane) that can be recognized because of the unendingmatchbox alignments. The informal residential neighborhood that you have beentaken to with its shacks and dirt tracks visited often by pedestrians and bicycles isapparently peaceful and even nice. There is a village or rural ambiance and that iswhere the problem lies! You are in another world, that of the Bantus, that is, formerreserves and then bantoustans, that today is not demarcated by any police boundary.But fortunately NoGo Zones make up for this shortage virtually* it is a substitute thatallows you to confine yourself through the prohibited zone programming!

* It is a virtual creation not in the sense of a “probable or potential future” but of immaterial

operational reality..

Doc

umen

t dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.c

airn

-int.i

nfo

- - G

iraut

Fre

deric

- 8

6.21

8.8.

133

- 19/

05/2

015

22h2

6. ©

Bel

in D

ocument dow

nloaded from w

ww

.cairn-int.info - - Giraut Frederic - 86.218.8.133 - 19/05/2015 22h26. ©

Belin

shopping malls meant for mass consumption (Houssay-Holzschuch, Vacchiani-Marcuzzo, 2009).

In the postmetropolis model developed by Edward Soja based on Los Angeles,this dimension of urban organization which favors long-distance relationships overproximity and disconnections between homogenous entities over gradients is the“fractal city” dimension. The links between pieces and fragments are establishedbecause of social affinity in the framework of metropolitan division of labor. Therelational dimension is thus totally free from contiguity of urban neighborhoodsseparated from one another by a material system.

In fact, in such a context, the expression “multi-sited territory” can be appliedeither to discontinuous spaces of different social groups which become entangled inthe agglomeration and beyond, or to the agglomeration itself as an eminently politicalterritory which associates contrasting and distant fragments of the city where urbanintegration and redistribution is a major challenge.

In the first case, territory is defined through practices and appropriation. In thesecond case, it is defined through the exercise of a power or through the political func-tion of space considered as a space which associates different social groups and, in thisrespect, calls for a specific government (or governance). In fact, the main South-Africanagglomerations today have metropolitan government-type integrated managementinstitutions while being particularly fragmented. They are thus political variable territo-ries made up of parts that have to be systematically re-established in various inheritedzonings which are contrasting social contexts and refer to the extreme socio-spatialdivision of the metropolitan space.

Thus there is the dichotomy of approaches in social geography against the dicho-tomy of territory (sociocultural vs. sociopolitical). We will come back to this in thethird part to define our position but the adjective ‘‘multi-sited’’ covers, in both cases,complex territorialities that are based on networks and associations of complementaryplaces and zones. The oppressive inheritance of the colonial past and apartheid alliedto the contemporary functions of order, confinement and maintenance of multi-sitedterritories contribute to the contemporary territorial complexity that we have describedelsewhere (Antheaume, Giraut, 2005).

The new South African territorial complexity also comes from the imposition ofa dual system: a rational system of provincial, metropolitan and local government anda system of promotion of resource sites using a rationale that is entrenched in globa-lization independent of their local and regional registration.

In such a context, the territorial arrangements are also a fertile ground for post-modern innovations such as trans-provincial communes, transnational parks, develop-ment corridors, integrated metropolitan areas or even non-municipal districts, pluraltoponymies, etc. These formulae are tested in an attempt to respond to the politicalchallenges facing local government and the development of such a society(Antheaume, Giraut, 2002; Sutcliffe, 2002; Giraut, 2005; Giraut et al., 2005, 2008).

South Africa thus appears to be organized into multi-sited territories that tapvarious inherited zonings and add to a chronic territorial complexity associated with avery unequal and segregated division of labor, resources and space. Approaches fallingunder territorial postmodernity are used here to try to adapt the politico-administrativeorder to these socio-spatial realities. In the case of South Africa, we thus have threeexpressions for a set of realities that challenge modern territories:

Frédéric Giraut281

Doc

umen

t dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.c

airn

-int.i

nfo

- - G

iraut

Fre

deric

- 8

6.21

8.8.

133

- 19/

05/2

015

22h2

6. ©

Bel

in D

ocument dow

nloaded from w

ww

.cairn-int.info - - Giraut Frederic - 86.218.8.133 - 19/05/2015 22h26. ©

Belin

• territorial complexity: a tangle of scales and configurations;• territorial postmodernity: overcoming exclusive sovereignties and fixed frontiers; • multi-sited territory: set of contrasting and distant places that come under differentzonings and form functional, political and lived places.

Questions of politicial geography on the use of the expression“multi-sited territory”

While the relevance of the expression “multi-sited territory” seems evident in thecase of South Africa and its space configured by the apartheid system, questionsremain unanswered with respect to its use as a generic category in geography and thecontradictions that it is supposed to generate.

Is it necessary to address archipelago spatialities with territoriality?

In other words, is it necessary to recycle the notion of territory, which has beenexclusively associated for a long time with the realities of bounded sovereignty inorder to describe discontinuous spaces with variable geometry?

Among the authors who venture into the world of theoretization in geography,there are several who prefer to confine territory to the initial category of areolaryspatial functions marked by the principles of spatial modernity and contrary to reti-cularity: fixity in time and space, exclusive sovereignty, precise interlocking, and fron-tier-type linear demarcation. The argument is that a spatial concept has to be definedwith spatial properties. This is the case of Jacques Lévy and Michel Lussault (2003,2007) as well as, among the English speakers, Bob Jessop, Neil Brenner and MartinJones4 (2008) and John Allen (2009), who are all interested in theoretical proposals thatare outstanding because of their coherence, but which are based on a poor definition ofthe concept of territory. Yet, if we assume that territory is, above all, an informed spaceendowed with a form of power (Raffestin, 1980) or that it involves an intrinsically poli-tical space because of its composite social and economic composition that calls for aform of government (Giraut, 2005), it does not confine it to an areolar, continuous andfixed configuration.

This reflection does not justify the expression “multi-sited territory” but legitimizesthe potential association of territoriality (political in this case) with forms of dis-continuity and even multi-situation.

However, while a political conception of territory, and hence multi-sited territory,does not exclude an eventual reticular configuration, on the other hand, it excludes itsextension to non-political spatialities such as a polytopical habitat (Stock, 2006)made up of a set of living places linked through flows of living beings, who occupythem culturally and socially with their experience of mobility.

Is the adjective ‘multi-sited’ associated with territory ambivalent?

Does the ambiguity or rather the dual significance of the adjective ‘‘multi-sited’’,which, as opposed to multi-localized, evokes the plurality of localizations as well as theplurality of spaces or reference contexts, contribute to diluting the scope of theexpression through vagueness?

The adjective ‘‘multi-localized’’ clearly indicates a discontinuous configurationthrough the extension of a reality over several disjointed places. The adjective

4. In an attempt totheoritize thepolymorphism of socio-spatial relations, theysuggest that “territories(T), places (P), scales (S),and networks (N) must beviewed as mutuallyconstitutive andrelationally intertwineddimensions of sociospatialrelations” and then, theypropose a pertinentanalysis grid byreproducing the TPSNquadriptic. By doing so,their definition of theterritory appearsrestrictive by reproducingonly their territorialmodernity characteristics:Bordering, bounding,parcelization, enclosure;Construction ofinside/outside divides;constitutive role of the`outside’.” (Jessop et al.,2008).

© L’Espace géographique 282

Doc

umen

t dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.c

airn

-int.i

nfo

- - G

iraut

Fre

deric

- 8

6.21

8.8.

133

- 19/

05/2

015

22h2

6. ©

Bel

in D

ocument dow

nloaded from w

ww

.cairn-int.info - - Giraut Frederic - 86.218.8.133 - 19/05/2015 22h26. ©

Belin

‘‘multi-sited’’ also integrates a localized reality but one that has to be situated inrelation to different environments and different scales or dimensions.

The adjective thus goes further than multi-localized because it refers to multiplesituations, or in other words, to a positioning that is simultaneously related to severalsocio-spatial dimensions. Thus a multi-sited territory integrates the inter-territorial(Vanier, 2008) and the trans-territorial, not only the reticular, that is, a set of territorialfigures included in complex arrangements, which are not based on the principles ofterritorial modernity but which make territory. More specifically, territorial assem-blages arising from cooperation between institutional territories (neighboring or not) orparts of institutional territories (neighboring or not) can be considered as multi-sitedterritories. Thus it is about assemblages considered in English language literature as“non standard regional spaces” that contribute to the territorial reorganization of theState (Deas, Lord, 2006).

The combination of the two previous responses, which are also elements of theore-tical positioning, requires specifying and limiting the use that one can make of theexpression in the South African context. An extensive conception allows us initially tointegrate the social and individual spatialities related to the existence of discontinuousand segregated living areas, for example, those that will be programmed as sets of visi-table areas for a certain white South African bourgeoisie, targeted by the advertisementfor NoGo Zones. While these living areas are effectively multi-sited, they are politicalonly to the extent that they are the fruit of inherited policies of division of labor andspace and are a part of particularly unequal active socio-spatial relationships. But theydo not have political autonomy and do not form a territory to the extent that they arefundamentally and genetically an element of a socio-spatial system of governmentalitythat includes them (Dean, 1999). The contemporary attempts at establishing local andprovincial governents try to associate socially complementary spaces by grouping richareas and dominated and relegated areas to organize redistribution and create condi-tions for overcoming the segregated order. Thus the expression “multi-sited territory”aptly describes the city stemming from apartheid. It is discontinuous with buffer zonesand at the same time, made up of fragments that have to be situated with respect toliving and working spaces assigned to various segments of the society in larger networks.Finally, it constitutes a governmentality space in which a political project can be appliedby playing on a differentiated set of resources and populations with multiple affiliations.

Is multi-sited territory ungovernable by definition?

It is known that exercising representative democracy calls for a political territorialitywith fixed boundaries in time and space to stabilize citizenship and its exercise as well asthat of a political mandate (Lévy, 1994). Recognition and promotion of multi-sitedterritories would thus be incompatible with those of the territories of the democracy,which are by definition modern and thus obey principles of territorial modernity withits fixity, boundedness and exclusive sovereignty. In addition, multi-sited territoriescontribute to the fragmentation of classical territories (city, State) and promote forms ofextra-territoriality. But the crisis in representative democracy and the exercise of thelocal government in metropolitized societies provide possibilities, given the denunciationof “démocratie du sommeil” ‘the democracy of sleep’ (Viard, 2006) or non-exercise of acitizenship by commuting or cross-border workers or more so, by foreign residents, withrespect to the definition of the territory project in which they take an active part.

Frédéric Giraut283

Doc

umen

t dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.c

airn

-int.i

nfo

- - G

iraut

Fre

deric

- 8

6.21

8.8.

133

- 19/

05/2

015

22h2

6. ©

Bel

in D

ocument dow

nloaded from w

ww

.cairn-int.info - - Giraut Frederic - 86.218.8.133 - 19/05/2015 22h26. ©

Belin

In order to overcome this contradiction, several lines of approach are involved.Firstly, that of fragmentation by public choice (Estèbe, 2008) which supposes thebenefits of competition between basic local governments within the agglomerations,with the inhabitants using the public services “voting with their feet” (in other words,shifting their residence or their business) by joining the tax-service compromise whichsuits them best. Then comes interterritoriality or geometrically varying cooperationbetween basic political territories (Vanier, 2008), which allows flexible arrangementsadapted to each issue of spatial management. Finally, that of reconfigurable participa-tory democracy, which functions by mobilizing collectives and consultation frame-works in relation to political issues of spatial management. It is clearly the progress ofthese inter-territorialities and participatory democracy which makes it possible tobetter overcome better the steady conceptions of political territory by introducing apotentially innovative reflection on relationships between democracy and geography(Joliveau, Amzert, 2001; Barnett, Low, 2004; Bussi, 2006).

At a different scale, it is also in these terms that various imperial formulae andexpressions are referred to, comparatively in time and space (Sassen, 2006; Cooper,Burbank, 2011). These authors, by looking into legal and spatial technologiesdeployed in the framework of various empires over a very long timeframe, emphasizethe often flexible and innovative nature of management, recognition and exploitationof cultural and social differences. This is the case in complex and singular arrangementsthat play on plurality of status according to the situations. Empire can be considered as aform of multi-sited territory.

Multisited territory is thus potentially a referential figure both as a category foranalyzing contemporary political territorialities and as framework of the local orregional government renewed in a translocal or simply a multi-sited form.

AGNEW J. (1999). ‘‘Mapping political power beyond state boundaries: territory, identity and movementin world politics’’. Millennium: Journal of International Studies, vol. 28, no. 3, p. 499-521.

AGNEW J. (2010). ‘‘Still trapped in territory?’’. Geopolitics, vol. 15, no. 4, p. 779-784.ALLEN J. (2009). ‘‘Three spaces of power: territory, networks, plus a topological twist in the tale of

domination and authority’’. Journal of Power, vol. 2, no. 2, p. 197-212.ANDERSON J. (1996). ‘‘The shifting stage of politics: new medieval and postmodern territorialities?’’.

Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, vol. 14, no. 2, p. 133-153.ANTHEAUME B (coord.)(1999). ‘‘L’Afrique du Sud’’. L’Espace géographique, t. 28, no. 2, p. 97-187.ANTHEAUME B., GIRAUT F. (2002). ‘‘Les marges au cœur de l’innovation territoriale ? Regards croisés

sur les confins administratifs (Afrique du Sud, France, Maroc, Niger, Togo…)’’. Historiens etgéographes, no. 379, p. 39-58.

ANTHEAUME B., GIRAUT F. (eds.)(2005). Le Territoire est mort. Vive les territoires ! Paris: IRD Éditions,coll. ‘‘Hors collection’’, 386 p.

BARNETT C., LOW M. (eds)(2004). Spaces of Democracy. Geographical Perspectives on Citizenship,Participation and Representation. London: Sage Publications, 264 p.

BUSSI M. (2006). ‘‘L’identité territoriale est-elle indispensable à la démocratie ?’’. L’Espacegéographique, vol. 35, no. 4, p. 334-339.

CHRISTOPHER A.-J. (1994). The Atlas of Apartheid. London: Routledge, 224 p.— (reprint. 2002). Atlas of Changing South Africa. London: Routledge, 272 p.

© L’Espace géographique 284

References

Doc

umen

t dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.c

airn

-int.i

nfo

- - G

iraut

Fre

deric

- 8

6.21

8.8.

133

- 19/

05/2

015

22h2

6. ©

Bel

in D

ocument dow

nloaded from w

ww

.cairn-int.info - - Giraut Frederic - 86.218.8.133 - 19/05/2015 22h26. ©

Belin

COOPER F., BURBANK J. (2011). Empires. De la Chine ancienne à nos jours. Paris: Payot, 686 p.COX K. (1997). ‘‘Spaces of dependence, spaces of engagement and the politics of scale, or: looking

for local politics’’. Political Geography, vol. 17, no. 1, p. 1-23.DAVIES R.J. (1981). ‘‘The spatial formation of the South African city’’. GeoJournal, no. 2, p. 59-72.DEAN M. (1999). Governmentality. Power and Rule in Modern Society. New York: Sage, 229 p.DEAS I., LORD A. (2006). ‘‘From a new regionalism to an usual regionalism? The emergence of non

standard regional spaces and lessons for the territorial reorganization of the state’’. UrbanStudies, vol. 43, no. 10, p. 1847-1877.

DEBARBIEUX B. (2006). ‘‘Prendre position : réflexions sur les ressources et les limites de la notiond’identité en géographie’’. L’Espace géographique, vol. 35, no. 4, p. 340-354.

DELEUZE G., GUATTARI F. (1980). Milles plateaux. Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, coll. ‘‘Critique’’, 645 p.DUPUY G. (1991). L’Urbanisme des réseaux : théories et méthodes. Paris: Armand Colin, coll. ‘‘U.

Géographie’’, 198 p.ELDEN S. (2010a). ‘‘Land, terrain, territory’’. Progress in Human Geography.

http://phg.sagepub.com/content/early/2010/04/21/0309132510362603ELDEN S. (2010b). ‘‘Thinking Territory Historically’’. Geopolitics, vol. 15, no. 4, p. 757-761.ESTÈBE P. (2008). Gouverner la ville mobile. Paris: Presses universitaires de France, coll. ‘‘La Ville

en débat’’, 76 p.GIRAUT F. (2005). Fabriquer des territoires : utopies, modèles et projets. Paris: Université de Paris 1

Panthéon-Sorbonne, thèse d’habilitation à diriger des recherches (professoral thesis), 308 p.GIRAUT F., GUYOT S., HOUSSAY-HOLZSCHUCH M. (2005). ‘‘La nature, les territoires et le politique en

Afrique du Sud’’. Annales. Histoire, Sciences sociales, vol. 60, no. 4, p. 695-717.GIRAUT F., GUYOT S., HOUSSAY-HOLZSCHUCH M. (2008). ‘‘Enjeux de mots : les changements toponymiques

sud-africains’’. L’Espace géographique, vol. 37, no. 2, p. 131-150.GIRAUT F., MAHARAJ B. (2002). ‘‘Contested terrains: Cities and hinterlands in post-apartheid boundary

delimitations’’. GeoJournal, vol. 57, p. 39-51.GIRAUT F., VACCHIANI-MARCUZZO C. (2009). Territories and Urbanisation in South Africa. Atlas and

Geo-Historical Information System (DYSTURB). Bondy: IRD Éditions, coll. ‘‘Cartes et notices’’,CD-Rom.

GIRAUT F., VACCHIANI-MARCUZZO C. (2012). ‘‘Représenter les lieux et les populations dans une coloniede peuplement : un siècle de recensements sud-africains’’. Mappemonde, no. 106.http://mappemonde.mgm.fr/num34/articles/art12201a.html

GIRAUT F., VANIER M. (1999). ‘‘Plaidoyer pour la complexité territoriale’’. In GERBAUX F. (ed.), Utopiepour le territoire : cohérence ou complexité ? La Tour d’Aigues: Éditions de l’Aube, coll.‘‘Société et territoire’’, p. 143-172.

GRATALOUP C., MARGOLIN J.-L. (1987). ‘‘Du puzzle au réseau’’. EspacesTemps, no. 36, p. 55-66.HARRISON J. (2010). ‘‘Networks of connectivity, territorial fragmentation, uneven développement:

The new politics of city regionalism’’. Political Geography, vol. 29, no. 1, p. 17-27.HOUSSAY-HOLZSCHUCH M., VACCHIANI-MARCUZZO C. (2009). ‘‘Un morceau de territoire en quête de réfé-

rence : le centre commercial dans les aires métropolitaines en Afrique du Sud’’. In BOUJROUF S.,ANTHEAUME B., GIRAUT F., LANDEL P.-A. (eds), Les Territoires à l’épreuve des normes : référents etinnovations. Contributions croisées sud-africaines, françaises et marocaines. Marrakech,Grenoble: Université Cadi Ayyad et revue Montagnes méditerranéennes, p. 129-146.

JESSOP B., BRENNER N., MARTIN J. (2008). ‘‘Theorizing sociospatial relations’’. Environment andPlanning D: Society and Space, vol. 26, no. 3, p. 389-401.

JOLIVEAU T., AMZERT M. (coord.)(2001). ‘‘Les territoires de la participation’’. Géocarrefour, vol. 76, no. 3,p. 171-280.

Frédéric Giraut285

Doc

umen

t dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.c

airn

-int.i

nfo

- - G

iraut

Fre

deric

- 8

6.21

8.8.

133

- 19/

05/2

015

22h2

6. ©

Bel

in D

ocument dow

nloaded from w

ww

.cairn-int.info - - Giraut Frederic - 86.218.8.133 - 19/05/2015 22h26. ©

Belin

LÉVY J. (1994). L’Espace légitime : sur la dimension géographique de la fonction politique. Paris:Presses de la Fondation nationale des sciences politiques, 442 p.

LÉVY J. (2003). ‘‘Territoire’’. In LÉVY J., LUSSAULT M., Dictionnaire de la géographie et de l’espace dessociétés. Paris: Belin, p. 907-910.

LÉVY J., LUSSAULT M. (eds)(2003). Dictionnaire de la géographie et de l’espace des sociétés. Paris:Belin, 1033 p.

LUSSAULT M. (2007). L’Homme spatial. La Construction sociale de l’espace humain. Paris: Éditionsdu Seuil, coll. ‘‘La Couleur des idées’’, 363 p.

MAC CARTHY J., BERNSTEIN A. (1998). South Africa’s ‘‘Discarded People’’: Survival, Adaptation andCurrent Challenges. Johannesburg: The Centre for Develoment and Enterprise Research, Policyin the Making 9, 40 p.

MACLEOD G., JONES M. (2007). ‘‘Territorial, scalar, networked, connected: In what sense a ‘regionalworld’?’’. Regional Studies, vol. 41, no. 9, p. 1177-1191.

MOINE A. (2006). ‘‘Le territoire comme un système complexe : un concept opératoire pour l’aménage-ment et la géographie’’. L’Espace géographique, vol. 35, no. 2, p. 115-132.

NEWMAN D. (ed.)(1999). Boundaries, Territory and Postmodernity. London: Frank Cass, coll. ‘‘CasesStudies in Geopolitics’’, 206 p.

OFFNER J.-M., PUMAIN D. (eds)(1996). Réseaux et territoires : significations croisées. La Tourd’Aigues: Éditions de l’Aube, coll. ‘‘L’Aube territoire’’, 280 p.

PAASI A. (2002). ‘‘Place and region: regional worlds and words’’. Progress in Human Geography,vol. 26, no. 6, p. 802-811.

PAINTER J. (2007). ‘‘Territoire et réseau : une fausse dichotomie ? ». In VANIER M. (ed.), Territoires, terri-torialité, territorialisation. Controverses et perspectives. Rennes: Presses universitaires deRennes, coll. ‘‘Espace et territoires’’, p. 57-66.

PAINTER J. (2008). ‘‘Cartographic anxiety and the search for regionality’’. Environment and Planning A,vol. 40, no. 2, p. 342-361.

PENROSE J. (2002). ‘‘Nations, states and homelands: territory and territoriality in nationalistthought’’. Nations and Nationalism, vol. 8, no. 3, p. 277-297.

PUMAIN D. (2012). ‘‘Espace et territoire : vers des concepts scientifiques intégrés’’. In BECKOUCHE P.,GRASLAND C., GUÉRIN-PACE F., MOISSERON J.-Y. (eds), Fonder les sciences du territoire. Paris: ÉditionsKarthala, p. 53-70.

RAFFESTIN C. (1980). Pour une géographie du pouvoir. Paris: Librairies techniques, coll. ‘‘Géographieéconomique et sociale’’, 249 p.

RAFFESTIN C. (1986). ‘‘Écogénèse territoriale et territorialité’’. In AURIAC F., BRUNET R. (eds), Espaces,jeux et enjeux. Paris: Fayard, coll. ‘‘Nouvelles encyclopédies des sciences et des techniques’’,p. 173-185.

RAFFESTIN C. (2012). ‘‘Space, territory, and territoriality’’. Environment and Planning D: Society andSpace, vol. 30, no. 1, p. 121-141.

RAMUTSINDELA M.R. (2001). Unfrozen Ground: South Africa’s Contested Spaces. Aldershot: Ashgate, 102 p.RETAILLÉ D. (2005). ‘‘L’espace mobile’’. In ANTHEAUME B., GIRAUT F. (eds), Le Territoire est mort. Vive

les territoires ! Paris: IRD Éditions, coll. ‘‘Hors collection’’, p. 175-201.SASSEN S. (2006). Territory, Authority, Rights. From Medieval to Global Assemblages. Princeton:

Princeton University Press, 493 p.SCHOLTE J.A. (2000). Globalization: A Critical Introduction. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 304 p.STOCK M. (2006). ‘‘L’hypothèse de l’habiter poly-topique : pratiquer les lieux géographiques dans

les sociétés à individus mobiles’’. EspacesTemps.nethttp://espacestemps.net/document1853.html

© L’Espace géographique 286

Doc

umen

t dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.c

airn

-int.i

nfo

- - G

iraut

Fre

deric

- 8

6.21

8.8.

133

- 19/

05/2

015

22h2

6. ©

Bel

in D

ocument dow

nloaded from w

ww

.cairn-int.info - - Giraut Frederic - 86.218.8.133 - 19/05/2015 22h26. ©

Belin

Frédéric Giraut287

SUTCLIFFE M. (2002). ‘‘Creating cities of Hope’’. In ANTHEAUME B., GIRAUT F., MAHARAJ B. (eds), Recom-positions territoriales, confronter et innover. Actes des rencontres scientifiques franco-sud-africaines de l’innovation territoriale. Paris, Durban: IRD, université du Natal, 5 p.http://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/docs/00/76/97/42/PDF/Sutcliffe_31.pdf

VANIER M. (2008). Le Pouvoir des territoires. Essai sur l’interterritorialité. Paris: Economica,Anthropos, coll. ‘‘Géographie’’, 160 p.

VANIER M. (ed.)(2009). Territoires, territorialité, territorialisation. Controverses et perspectives.Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes, coll. ‘‘Espace et territoires’’, 228 p.

VELTZ P. (1996). Mondialisation, villes et territoires. L’économie d’archipel. Paris: Presses universitairesde France, coll. ‘‘Économie en liberté’’, 262 p.

VIARD J. (1994). La Société d’archipel ou les territoires du village global. La Tour d’Aigues: Éditionsde l’Aube, coll. ‘‘Monde en cours’’, 126 p.

VIARD J. (2006). Éloge de la mobilité. Essai sur le capital temps libre et la valeur travail. La Tourd’Aigues: Éditions de l’Aube, coll. ‘‘Monde en cours’’, 205 p.

VODOZ L., PFISTER-GIAUQUE B., JEMELIN C. (eds)(2004). Les Territoires de la mobilité. L’aire du temps.Lausanne: Presses polytechniques et universitaires romandes, 383 p.

WERLEN B. (1993). Society, Action and Space. London: Routledge, 249 p.

Doc

umen

t dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.c

airn

-int.i

nfo

- - G

iraut

Fre

deric

- 8

6.21

8.8.

133

- 19/

05/2

015

22h2

6. ©

Bel

in D

ocument dow

nloaded from w

ww

.cairn-int.info - - Giraut Frederic - 86.218.8.133 - 19/05/2015 22h26. ©

Belin