Migration-related health inequalities: Showing the complex interactions between gender, social class...

Transcript of Migration-related health inequalities: Showing the complex interactions between gender, social class...

1

Migration-related health inequalities: Showing the complex interactions between gender,

social class and place of origin.

Social Science and Medicine, 2010, 71(9), 1610-9.

Unformatted, pre-print manuscript. Article available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.043

Davide Malmusia,b,c,d

*, Carme Borrella,c,d,e

, Joan Benachc,f

aAgència de Salut Pública de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

bTraining Unit in Preventive Medicine and Public Health IMAS-UPF-ASPB, Barcelona, Spain

cCIBER Epidemiología y Salud Pública (CIBERESP), Spain

d Institute of Biomedical Research (IIB-Sant Pau), Barcelona, Spain

e Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Spain

f Health Inequalities Research Group (GREDS), Employment Conditions Network (EMCONET),

Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Spain

* Corresponding Author. [email protected]

Abstract

In this paper, we briefly review theories and findings on migration and health from the health

equity perspective, and then analyse migration-related health inequalities taking into account

gender, social class and migration characteristics in the adult population aged 25-64 living in

Catalonia, Spain. On the basis of the characterisation of migration types derived from the

review, we distinguished between immigrants from other regions of Spain and those from other

countries, and within each group, those from richer or poorer areas; foreign immigrants from

low-income countries were also distinguished according to duration of residence. Further

stratification by sex and social class was applied. Groups were compared in relation to self-

assessed health in two cross-sectional population-based surveys, and in relation to indicators of

socio-economic conditions (individual income, an index of material and financial assets, and an

index of employment precariousness) in one survey. Social class and gender inequalities were

evident in both health and socio-economic conditions, and within both the native and immigrant

subgroups. Migration-related health inequalities affected both internal and international

immigrants, but were mainly limited to those from poor areas; were generally consistent with

their socio-economic deprivation; and apparently more pronounced in manual social classes and

especially for women. Foreign immigrants from poor countries had the poorest socio-economic

situation but relatively better health (especially men with shorter length of residence). Our

findings on immigrants from Spain highlight the transitory nature of the ‘healthy immigrant

effect’, and that action on inequality in socio-economic determinants affecting migrant groups

should not be deferred.

Keywords: health inequalities; migration and health; socio-economic conditions; self-rated

health; Spain

2

Introduction

In economically advanced countries, theoretical and empirical research on health

inequalities and on health among migrants has generally developed in parallel, with few

attempts to integrate the two fields. Migration and health issues have only been partially

addressed within the health equity framework. In this paper, we briefly review theories and

findings regarding migrants’ health from the health equity perspective and then analyse

migration-related health inequalities in Catalonia taking into account gender, social class, and

migration circumstances. The framework of the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of

Health (CSDH) highlights the existence of health inequalities that are dependent on the different

spheres that shape an individual’s position in society, such as social class, gender and ethnicity

(Solar & Irwin, 2007). Inequalities faced by racial and ethnic minorities have been widely

described in countries such as the United States and United Kingdom, which have a very long

(decades or centuries) history of migration, intertwined with slavery and colonialism, and

established minorities (Nazroo, 2003). In other western European countries, the study of

inequalities related to migration dynamics might be also useful, and has attracted growing

interest. Catalonia (around 7,000,000 inhabitants), which has experienced a large and now

established immigration flow from other areas of Spain, and a more recent one from abroad, can

constitute an interesting case study.

Immigrants’ health trajectory and its explanations

Previous work on migrants´ health generally compares the health of international migrants

to that of the native population in the destination country. Most findings are consistent with the

so-called “healthy immigrant effect”: recently arrived immigrants (usually from poor areas)

have generally better health than the native population, or at least better than expected for their

socio-economic characteristics; this health advantage is frequently observed to deteriorate more

rapidly than among natives, despite a relative socio-economic improvement (Ronellenfitsch &

Razum, 2004; Vissandjee, Desmeules, Cao, Abdool & Kazanjian, 2004; Newbold, 2005;

Uretsky & Mathiesen, 2007). A possible explanation for this pattern, proposed in several US

studies on Hispanic immigrants (Escobar, Hoyos Nervi & Gara, 2000; Abraido-Lanza, Chao &

Flórez, 2005; Hosper, Nierkens, Nicolaou & Stronks, 2007; Lutsey et al., 2008), suggests that

culture-based healthier lifestyles, stronger social bonds and support from the country of origin

initially exert a protective effect on immigrants´ health; but that these factors are progressively

lost as immigrants undergo a process of “acculturation”, i.e. assimilate dominant culture and

habits, and in their offspring. However, in these studies acculturation was not measured directly,

but simply as a function of the duration or number of generations of residence; also, searching

3

for a culture-based explanation might divert attention from structural constraints (Viruell-

Fuentes, 2007, p.1525). In fact, there is evidence that immigrants also have better levels of

health than the population in their place of origin, and this is especially true for young migrants

whose primary goal is to find work; this has been attributed to a labour-related positive health

selection due to the high physical demands of the manual jobs that most occupy (Marmot,

Adelstein & Bulusu, 1984; Lu, 2008; Redstone Akresh & Frank, 2008). Also, many studies

show that less privileged social class and poorer socioeconomic conditions account partly or

totally for the poorer health outcomes of individuals from low-income countries (Reijneveld,

1998; Lindström, Sundquist & Östergren, 2001; Hjern, Wicks & Dalman, 2004; van der Wurff

et al., 2004; Levecque, Lodewyckx & Vranken, 2007; Tinghög, Hemmingsson & Lundberg,

2007; Rasch, Gammeltoft, Knudsen, Tobiassen, Ginzel & Kempf, 2008); additional, specific

mechanisms of inequality creation have also been postulated such as discrimination (Gee, Ryan,

Laflamme & Holt, 2006) and “othering” (being treated as ‘the other’: Viruell-Fuentes, 2007).

Together, these findings – positive health selection, rapid decline in health despite a parallel

socio-economic improvement, and socio-economic explanations of inequality – make sense if

we attribute this accelerated health decline as the late-effect of cumulative inequality, both in

the place of origin, with poorer socio-economic environment in childhood and growth

(Ronellenfitsch et al., 2004), and in the place of destination, with chronic exposure to work

hazards, poor living conditions, hardship and discrimination, mechanisms that are well

recognized as causal factors of racial and ethnic inequalities in health (Krieger, 2003; Nazroo,

2003; Harris, Tobias, Jeffreys, Waldegrave, Karlsen & Nazroo, 2006). The psychobiological

impacts of a forced migration, such as separation from friends and relatives and loss of social

status, may add to these mechanisms.

Characterising migration: advantaged and disadvantaged, internal and international

Another recurrent characteristic in recent studies on immigration and health is the

distinction between immigrants from ‘Western’, ‘high-income’ or ‘developed’ countries, and

those from ‘other’, ‘low-income’ or ‘developing’ countries: a distinction which is empirically

supported by data, but rarely accompanied by theoretical discussion (Lindström et al., 2001;

Pudaric, Sundquist & Johansson, 2003; Hjern et al., 2004; Hosper et al., 2007; Levecque et al.,

2007; Rasch et al., 2008). In our view, this distinction makes sense, in that emigration from

deprived areas is usually a forced choice, shared by a wide sector of the population, as the result

of broad imbalances in economic and social well-being between the countries of origin and

destination (Castles, 2003); this often implies entry to the host society in a subordinate position,

with little negotiating power, and increased vulnerability to discrimination and exploitation.

This type of migration – based on labour movement from impoverished to advantaged and

4

expanding economies – is the predominant or most increasing type in both internal and

international migration flows (Lu, 2008; United Nations, 2009) and is the most important for

analyses of health inequalities based on power relations. The minority of immigrants who move

between wealthy areas are more likely to do so for individual circumstances and opportunities,

and do not share the characteristics mentioned above. In this sense, migration is a reflection of

global, geographical inequalities between countries, territories and populations.

Finally, the vast majority of studies on health inequalities between natives and immigrants

have focused on international migration. However, internal migrants – those who have moved

within the same country – are at least four times as many as international ones (UNDP, 2009,

p.1). Most theoretical work makes little distinction between internal and international migration

but often suggests that the basic underlying mechanisms and challenges (adaptation to a new

life, economic hardship) apply equally to both groups (Lu, 2008). Legal restrictions and greater

geographical and cultural distance are the additional barriers (related both to health selection

and hazards) faced by international migrants (Lu, 2008). Some of the studies on health

inequalities between natives and immigrants from other regions of the same or an adjacent

country described poorer health for Finns in Sweden (Pudaric et al., 2003; Westman, Martelin,

Härkänen, Koskinen & Sundquist, 2008); higher mortality among Irish and Scottish immigrants

in England (Marmot et al., 1984; Raftery, Jones & Rosato, 1990; Wild & Mckeigue, 1997); but

less hypertension and overweight than non-migrants for employment-related internal migrants

in Croatia (Kolcić & Polasek, 2009).

Our study area, Catalonia, is a relatively wealthy region within Spain, with its own

language, customs, and national identity, with the interesting characteristic of having

experienced in the last 50 years two separate waves of interregional and international

immigration, in both cases mainly (but not exclusively) from disadvantaged areas. The last

decade has seen a rapid increase in foreign immigration, which increased the foreign-born

population in municipal continuous registers from 4% in the year 2000 to 14,8% in 2007

(Idescat, 2008); for this reason, good quality data on the health of this sector of the population

are just becoming available. 12.6% of the adult immigrant population were born in the highly

developed EU-15 countries, while the rest includes 41.1% from Central and South America

(from various countries, being Ecuador, 7.9%, the most common); 23.5% from Africa (mostly

Morocco, 17.4%); 13.2% from the rest of Europe (Romania, 6%); and 8.8% from Asia. On the

other hand, several different waves arrived from other regions of Spain during the second half of

last century, especially in the 1950s and 1960s, when the rapidly expanding Catalan economy

required workers, and the areas of the south and west of Spain were affected by unemployment

and poverty. At present in Catalonia there are more people born in other Spanish regions than in

Catalonia itself in some age cohorts, such as those aged 55 to 74 (Idescat, 2008). This

heterogeneity has been largely omitted in health studies. Recently, the only study of

5

immigration and health status was published, as far as we are aware, that includes in a separate

group Spanish individuals born outside Catalonia (Borrell et al., 2008).

Integrating migration with other inequality mechanisms

The migration dimension cannot be understood independently of social class and gender, as

all three are key intertwined mechanisms of power relations in society (Anthias, 2001). Through

processes such as exploitation, domination and discrimination, power determines the extent to

which an individual or group can influence their surrounding environment, and it entails

privileges, opportunities, access to resources and health-damaging exposures (the so-called

intermediary determinants of health in the CSDH framework) throughout life. Studies

describing health inequalities by both social class and gender are increasing, and in Catalonia

women in disadvantaged classes have the worst indicators of morbidity and self-assessed health

(Borrell et al., 2006). As described, several studies have simultaneously explored socio-

economic position and migration status (Marmot et al., 1984; Reijneveld, 1998; Levecque et al.,

2007), and others socio-economic position and race/ethnicity (see Davey Smith, 2000; Krieger,

2003). However, only a few studies have attempted to analyse inequality in three dimensions

simultaneously, usually with gender, socio-economic position and race/ethnicity (Pamuk,

Makuc, Heck, Reuben & Lochner, 1998; Almeida-Filho et al., 2004; Schulz & Mullings, 2006;

Clarke, O’Malley, Johnston & Schulenberg, 2009), but also with migration status (Borrell et al.,

2008). A recent study in California showed that body mass index among immigrants increases

with length of residence, and the pace of increase is higher among women, those with the lowest

education level, and Hispanics (Sanchez-Vaznaugh, Kawachi, Subramanian, Sánchez &

Acevedo-Garcia, 2008). Pamuk et al. (1998) found that a stable racial minority such as Black

people in the US had poorer self-rated health than Whites at each level of income, whereas the

Hispanic (a large proportion of whom were immigrants) had equal or better health; and that

women had worse health than men among Black and Hispanic, but not among Whites.

In summary, it seems reasonable that an analysis of migration-related health inequalities

requires a classification of migration type that takes into account the duration of residence and

characteristics of the place of origin, i.e. its grade of economic development, and localization

within or outside the receiving country. The aim of the next section is to test empirically the

relevance of this classification and to explore the intersections of migration type with gender

and social class in the analysis of social inequalities in health status in Catalonia. Also, we will

look at the distribution, in the same dimensions, of socio-economic assets and privileges – the

intermediary determinants – and at their contribution to the relationship between migration type

and health.

6

Methods

Study population, sample and data collection

The population context was the 2006 non-institutionalised population of Catalonia, Spain.

Two cross-sectional surveys carried out on the same population were used: the Enquesta de

Condicions de Vida i Hàbits de la Població (which we will refer to as the Living Conditions

Survey, LCS) and the Enquesta de Salut de Catalunya (the Health Interview Survey, HIS). Both

surveys are part of the regional government’s official statistical plan, and share the following

characteristics: a random sampling method stratified by territory, age and sex; individuals

selected from the continuous population register (response rates for eligible subjects were

72.7% in the LCS and 84% in the HIS; non-responders were replaced by subjects with the same

characteristics); and information collected during face-to-face interviews at home.

In this study, we restricted the analysis to the adult population aged 25 to 64, in order to

ensure an acceptable comparability in work-related and economic circumstances of social

classes and migrant groups with quite different age structures. This comprises a sample of

10,408 individuals in the HIS and 7,107 in the LCS. We mainly focused on the LCS, due to its

more extensive socio-economic information, but HIS data were also used for validating results

for the health variable.

Indicators and variables

The dependent variable was derived from a single question on self-assessment of general

health. Studies of health inequalities have made extensive use of this simple question, which not

only has predictive power for mortality and morbidity, but also reflects the global judgement of

the individual, combining evaluation of disease, symptoms, functional abilities and general

well-being. This question has demonstrated reasonable validity in comparison across socio-

economic positions (Quesnel-Vallée, 2007; Bago-d’Uva, O’Donnell & van Doorslaer, 2008).

The following question (not age-comparative) was used: ‘‘Would you say your overall health

is…” with 5 possible answers, ranging from ‘excellent’ to ‘poor’ in the HIS, and ‘very good’ to

‘very poor’ in the LCS. A dichotomous outcome variable was used (Poor health=less than good;

Good health=good or better), which has been shown to give very similar results to ordinal

methods (Manor, Matthews & Power, 2000). Poor health was reported by comparable

proportions of the population in the two surveys: 21.7% of LCS subjects (three possible answer

categories below ‘good’) and 19.5% of the HIS subjects (two categories below ‘good’).

7

Social class is based on the current or last occupation of the subject, or in its absence, the

occupation of the partner or household reference person. The Spanish adaptation of the British

Registrar General classification was used (Domingo-Salvany, Regidor, Alonso & Alvarez-

Dardet, 2000):

- Class I (higher-level professionals, administrative managers, directors of large companies);

- II (medium-level professionals and directors of small companies);

- III, which we further separated into III-non-manual (administrative workers, clerks, safety

and security workers) and III-manual (self-employed and supervisors in manual

occupations);

- IV (skilled and semi-skilled manual occupations);

- and V (unskilled manual occupations).

Place of birth and duration of residence were used to define the migration type. People born

in Catalonia (native Catalans) constitute the reference category. Migrants were first separated

into internal (people born in the rest of Spain) and international (people born abroad). To further

divide internal migrants according to the socio-economic situation of their place of origin, we

retrieved an estimation of the Human Development Index (HDI) by Spanish regions for the year

1981 (Herrero, Soler & Villar, 2005), which we expected to be more related to migration

decisions in the peak period of the internal immigration wave than a current estimation. We

grouped the 16 regions (excluding Catalonia) into thirds: an upper third of 5 regions with a HDI

range of 0.857-0.846 (Catalonia had 0.851), a medium third of 5 regions (range 0.841-0.825)

and a bottom third of 6 (0.811-0.763), which we respectively named ‘Spain-wealthy’, ‘Spain-

average’ and ‘Spain-poor’.

The same division among foreign immigrants was based on the HDI elaborated by the

United Nations Development Programme in the year of the surveys (UNDP, 2006). EU-15

countries and other countries with similar HDI were coded as ‘Foreign-advanced’ and the rest as

‘Foreign-poor’. The cut-off was set at the level of the EU-15 country with lowest HDI, Portugal,

which was 0.904 that year. In its last report (2009, p. 171), UNDP has set a cut-off at 0.900

above which lie countries with “very high human development”.

Immigrants from poorer countries were also classified as recent and long-term according to

duration of residence. Other migrant groups were not separated into recent and long-term

categories because of the low number of recent internal immigrants and immigrants from richer

countries. Categories in previous studies were alternatively set at 5, 10 or 20 years, with

evidence of progressive health deterioration without a preferrable cut-off point (Newbold &

Danforth, 2003; Ronellenfitsch & Razum, 2004; Uretsky & Mathiesen, 2007). Therefore, and

taking into account the sample size limitations, we separated recent and long-term on the basis

of the median year of arrival in both of our samples, 2000, i.e. 6 years before the survey date.

8

Those who arrived before 2000 were classified as long-term, and those arrived afterward, as

recent.

As for the intermediary determinants of health, we focused on three dimensions of living

and working conditions. Three variables were extracted from the LCS, and treated as dependent

or adjustment variables depending on the analysis:

- economic and material conditions of the household: the available items were all

dichotomised and an index was created by adding the 10 items giving the highest internal

consistency (Cronbach’s alpha: 0,76). These were: savings capacity; (no) difficulty in

making it through the month; active financial investments; spending for leisure; having a

hired person for household labour; and availability of some items: dishwasher; vacuum

cleaner; personal computer; internet connection; landline phone. The index was used as

continuous variable in logistic models, and dichotomised in descriptive analysis, with the

lowest tertile (4 or less items) coded as material deprivation;

- individual income: the respondent could place her/himself in one of 12 possible ranges of

monthly net income. Descriptive analyses were restricted to workers with valid responses,

dichotomising income at the lower third of the sample distribution: below or above 900

euros/month, coded as low income (yes/no). In logistic models, the categories “no

individual income” and “non-response or irregular income” (12.3% of the subjects), were

added;

- employment conditions: for those employed, we selected six items related to the concept of

‘precariousness’ (Vives et al., 2010): type of contract (permanent versus temporary or no

contract), time in current job (more or less than 5 years), unemployment during last 5 years

(yes/no), unions’ representation in the firm (yes/no), paid holidays (more or less than 30

days), and self-perceived job insecurity. The resulting index (Cronbach’s alpha: 0,58) was

dichotomised with subjects with three or more of the “insecure” characteristics coded as

precarious employment. In logistic models, those not employed were added as a separate

category.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were carried out using the Stata 9 package, and included weights derived from the

complex sample design. Results were stratified by sex.

First, we described the demographic characteristics, socio-economic conditions and health

status of the six social classes and the seven migration-based groups, separately. Due to the

large differences in age distribution between groups, we directly described the variables of

interest adjusted by age. This was made by comparing all the groups, for each dependent

variable, in a logistic regression adjusted by age; for the sake of interpretability, predicted

9

prevalences (e.g. of poor health) at 45 years of age were obtained for each group using the

logistic regression post-estimation function.

Thereafter, two separate approaches were used to describe and explain migration-related

inequalities in a framework of gender and social class. One consisted of describing once again

socio-economic conditions and health status in a matrix of sex, social class and migration at a

time, after simplifying both the migration and social class classifications. The other was to

compare by means of logistic regression the health status of migration-based groups, adjusting

for age; and then, adding as potential mediators, sequentially, social class; material conditions

of the household; individual income; and employment status and conditions.

Results

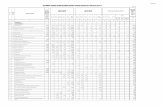

--- Table 1 about here ---

Socio-demographic description of the samples

A total of 3510 women and 3597 men composed the LCS sample, and 5086 women and

5322 men composed the HIS sample. Table 1 displays the distribution of the samples by sex and

social class and by sex and origin; and for each category, mean age, and age-adjusted socio-

economic situation and health status.

Social class IV was the largest group in both sexes and both surveys. In both surveys,

women in manual classes (III-m to V) were generally older than in non-manual classes, whereas

no such pattern was observed in men. With regard to origin, 64.6% of the LCS subjects were

Catalans, 22.8% were born in the rest of Spain and 12.6% were born abroad. Corresponding

figures in the HIS were 70%, 20.8% and 9.2%. In both surveys, the majority of internal

immigrants were from the poorest regions group, and the majority of foreign immigrants were

from the poor countries group. Internal immigrants were older than the native Catalans, with

age increasing from the richest to the poorest regions group, whereas recent immigrants from

poor countries were younger.

Social class and gender inequalities in socio-economic conditions and health

All socio-economic indicators in the LCS, as well as the health indicator in both surveys,

showed increasing levels of deprivation with decreasing social classes (Table 1). In all social

classes and migration groups, women were more likely than men to report poor health and to

have a low income when employed; women also had worse employment conditions than men in

some groups: manual social classes, immigrants from average and poorest regions of Spain, and

10

recent immigrants from poor countries. ‘Spain-average’ and ‘Spain-poor’ were also the only

groups where women experienced greater material/financial deprivation.

Migration-related inequalities in socio-economic conditions and health

People from both the wealthiest and average regions of Spain had similar or better socio-

economic indicators compared to those of the native population, with the exception of women

from ‘Spain-average’ regions, who had slightly poorer indicators. Health levels in these groups

were also similar to those of the reference population, except for a high proportion of poor

health reported among the 56 women from rich regions in the HIS sample.

‘Spain-poor’ women were markedly more disadvantaged than natives for all socio-

economic and health indicators; men also had poorer health in both surveys, and a relative

excess of deprivation, whereas they were similar to the reference population in terms of income

and employment conditions.

‘Foreign-advanced’ immigrants had similar, if not better, socio-economic and health

indicators than the native population. Conversely, ‘foreign-poor’ immigrants had by far the

worst situation in all socio-economic indicators, especially in the more recent group. Their

health situation differed by gender: women reported worse health than natives, and the pattern

according to duration of residence was opposite in the two surveys. Men’s prevalence of poor

health was more similar to natives’ levels, and even lower in recent immigrants in the HIS

sample.

Socio-economic and health inequalities in a matrix of sex, social class and migration type

The next step consisted of the simplification of social class grouping and migration type

classification, taking into account the differences and similarities described, as well as the

sample size limitations. Because of the low proportion of immigrant subjects in the non-manual

social classes (I, II and III-nm) and the consequent difficulty in making the groups big enough,

these were grouped into one. Class III-m was also small and was therefore grouped with class

IV, to which it was more similar than the aggregated non-manual classes. Finally class V, which

was clearly the least advantaged in most indicators, especially in women, was maintained

separate. Migration type classification was simplified first by combining immigrants from the

wealthiest and intermediate Spanish regions, which were two small and fairly similar groups,

into ‘Spain-rich’; and second, ‘foreign-poor’ immigrants were considered together regardless of

duration of residence. The sample distribution in the resulting groups is shown in Table 2, and

socio-economic and health indicators are displayed in Figure 1. Note that figures for immigrants

11

from advanced countries were ultimately removed, as they comprised only 1-40 subjects in each

subgroup.

--- Table 2 and Figure 1 about here ---

Figure 1 shows that the social class gradient and the gender gap in socio-economic

conditions and health generally persist within both the native population and the different

immigrant groups. Conversely, differences between migrant types are more inconsistent,

depending on social class, gender and the measured outcome.

Health inequalities affecting ‘Spain-poor’ immigrants persist in each class among women,

but disappear among men, except in the IIIm-IV group. In the case of deprivation, inequality

persists within each social class grouping and gender. The gap in income between native and

‘poor Spain’ women persists in manual classes only, and the gap in employment conditions

disappears.

‘Foreign-poor’ men and women have still the highest levels of material deprivation and

precariousness within each class. ‘Foreign-poor’ men continue to have an equal or better health

status than natives in their class (clearly better in class V), whereas women have worse health

among the unskilled group and inconsistent results between the two surveys in other social

classes.

In the case of ‘Spain-rich’ immigrants, stratification by social class uncovers some relative

disadvantage for manual women, namely a higher prevalence of material deprivation and poor

health. Among men the sample size is inadequate to interpret findings.

--- Table 3 and Figure 2 about here ---

Migration-related health inequalities: the role of socio-economic position and conditions

Table 3 shows the results of the alternative approach, that is the analysis of migration-

related health inequalities stratified by sex, and adjusted for social class and indicators of living

and working conditions, considered as potential mediators. Figure 2 illustrates how the risk of

poor health of certain migrant groups is attenuated by the introduction of these variables in the

models.

Models adjusted only by age show a significant excess risk of poor health for ‘Spain-poor’

migrants among male (OR 1.48) and especially among female (OR 2.11), compared to the

Catalan-born group. The excess risk among men is clearly reduced and no longer significant

12

when adjusted for social class and the material and economic assets index; among women, the

risk is partially reduced but still significant after these adjustments.

Immigrant men and women from advanced countries, as well as ‘Spain-rich’ men, showed a

non-significant tendency to lower risk of poor health. Only ‘Spain-rich’ women had a slight,

non-significant, excess risk of poor health (OR 1.27), hardly modified by socio-economic

adjustments.

The ‘foreign-poor’ were disaggregated into more and less recent migrants. More recent

immigrant women had a significantly higher risk of poor health (OR 1.70), which was reversed

(OR 0.84) after adjustment for social class and economic assets. All other ‘foreign-poor’ groups

(less recent immigrant women, more and less recent immigrant men) had a slight, non-

significant, excess risk of poor health, which was significantly reversed ) by socio-economic

adjustments.

Discussion

This study analyses inequalities in socio-economic determinants and self-assessed health

status according to gender, social class and migration type, defined on the base of sociological

theory, historical context and literature review. As discussed below, the findings show that this

migration type classification helps to detect and understand migration-related health

inequalities, which:

- affect both internal and international immigrants, but are mainly limited to immigrants from

poor areas, as a reflection of global inequities between countries and regions;

- seem to affect women more than men;

- are largely consistent with immigrants’ socio-economic deprivation compared with natives.

The ‘healthy immigrant effect’ might explain the relative health advantage of recent foreign

immigrants and especially men.

In addition, the magnitude and strength of inequalities by social class and gender stand out

independently of birthplace. Social class and gender are fundamental drivers of living and

working conditions and health status, not only among natives but also within all immigrant

groups. Also, social class and gender may act as mediators or effect modifiers of some of the

associations between migration type and health status. Therefore, in Catalonia, as also

demonstrated in research elsewhere, studies on migration and health must take these two

dimensions of inequality into account.

Health inequalities by migration type, and the contribution of socio-economic factors

13

Fundamental differences were observed as a function of the level of economic development

of the place of origin, among both internal and international migrants. Immigrants from affluent

regions and countries were not dissimilar to the native Catalan population in terms of socio-

economic characteristics and health outcomes. Inequalities were only evident for those who had

migrated from clearly poorer areas. This result is in line with studies from other countries (such

as Pudaric et al., 2003), and with the hypothesis we made of two clearly distinct types of

migration, one which is assumed to be more likely to be the result of free choices or individual

opportunities, and another which we interpret as part of large population movements resulting

from marked economic inequalities between territories. These geographical inequities are

reproduced by the lower social position that these immigrants attain in the host society.

Thus, it is not unexpected that a large proportion of migration-related health inequalities are

“explained” after adjustment for social class and the material and financial situation, as

observed in other studies cited above (e.g. Reijneveld, 1998). We expected that the cumulative

‘embodiment’ of more adverse conditions both pre- (early life) and post-migration (living and

working conditions in the first periods in the host country) would result in excess risk of poor

health beyond the present social and economic situation, particularly for a long-term immigrant

population, such as that from within Spain. This hypothesis was supported to some extent for

women, but not for men. It is likely that these cumulative effects are still partly counterbalanced

by health-related selection processes, which have influenced the likelihood of migration as well

as of returning. Also, the capacity of the material assets index to add further explanatory power

to health differences than social class alone should be noted. Davey Smith (2000) and Nazroo

(2003) have pointed out the insufficiency of a single measure of socio-economic position to

control for the social disadvantage experienced by ethnic minorities in the US and UK. In this

case especially, the assets index might have acted as marker of accumulated wealth, as shown

by the fact that, while the gap in income and current employment conditions between natives

and ‘poor Spain’ immigrants was eliminated within the same social class, the gap in deprivation

persisted.

Another important finding is that, despite the focus in most other studies on international

migrants, internal migration may be also very relevant to a health inequalities analysis, and that

in the specific case studied, due to differences in migration wave period, it may also be

indicative of future developments in foreign immigrants’ health. Foreign immigrants from poor

countries reported the worst socio-economic conditions, but relatively good health, a pattern

attributable to the “healthy immigrant effect” that was expected for the most recent immigrants

only but also partly extended to those having lived in Spain for longer. In our analysis, ‘less

recent’ foreign immigrants had a median length of stay in Catalonia (15 years) which was far

shorter than for internal immigrants (37 years). In the long term, foreign migrants' health may

deteriorate to a level similar to (or possibly worse than) internal migrants, since as already

14

pointed out (Lu, 2008), international migrants face the same social and economic challenges as

internal migrants, and additional legal and cultural barriers (Solé, 2000).

The modifying effect of social class and gender on migration-related inequalities

In some cases, inequalities between natives and migrants from poor areas were wider in, or

limited to, manual social classes and especially women. If one looks at health data in Figure 1,

among the unskilled manual group, male and female patterns vary: among women, all

immigrant groups (from both poor and rich regions of Spain, and from poor countries) showed

excess risk of poor health; whereas among men, immigrant groups had better health than natives

in the same social class. Possible explanations could include the following:

- family migration is usually in favour of man’s employment (Boyle, Cooke, Halfacree &

Smith, 2001); this implies both a greater health-related selection and consequent “healthy

immigrant effect” among men, and a detrimental effect on woman’s health;

- wider gender inequalities in immigrants’ societies of origin due to strong patriarchal

systems, where the “traditional” (submissive) role of women is enhanced. This was the case

in Spain, particularly outside Catalonia, under Franco’s dictatorship (Borrell et al., 2008),

and is also likely in most of the less economically advanced countries, as shown by

indicators such as the Gender Empowerment Measure (UNDP, 2006, p.367);

- as indicated by Lohan (2007), patriarchy may be reinforced in less favoured social classes

where men may appeal to hierarchies of masculinity rather than hierarchies of social class,

in order to regain social status. On the other side, manual immigrant women are exposed to

the cumulative burden of socio-economic and gender-related disadvantages and

disempowerments, together with their experience of marginalisation (Lynam, 2004).

Limitations

One of this study’s innovations lies in the simultaneous description of three complex

dimensions of inequality, although this was made difficult by insufficient sample size,

particularly in some subgroups that had to be excluded or aggregated in some analyses.

Also, due to sample size, we ruled out further splitting “foreign poor” immigrants by country or

continent of origin. A study on self-assessed health of foreigners in Spain found some

variability between continents, but did not stratify by sex and social class (Hernández-Quevedo

& Jiménez-Rubio, 2009). While waiting for data that make possible this analysis, we may

speculate that the phenomena described in our study are common to all immigrant populations

from poor backgrounds – as the case of the rest of Spain demonstrates – more than a specificity

15

of some peculiar “ethnic minorities”. The representativeness of the foreign population is another

issue. Since 2000, foreign immigrants can be registered in the municipal population registries

(the base for the survey) regardless of whether they have residence authorization, and this is a

prerequisite to freely register and access to public services, including healthcare. However, there

is some evidence of under-representation from the lower proportion of foreign immigrants in the

surveys than in population data. This might especially concern those more recently arrived

and/or with residential instability: groups probably affected by higher deprivation, but also

enjoying the “healthy immigrant effect”.

Language and cultural differences have been raised as possible sources of bias in self-

assessed health comparison between ethnic groups, or between natives and immigrants. This

should not apply to the larger immigrant group in our study, the one from within Spain. In

respect of foreign immigrants, we lack data in our context; nevertheless, such a bias is not

evident in studies on Asian immigrants in the US (Erosheva, Walton & Takeuchi, 2007); ethnic

minorities in the UK (Chandola & Jenkinson, 2000); or in a Dutch study, where the poorer

health rating of Turkish and Moroccans was consistent with their greater global burden of

diseases and use of health care (Agyemang, Denktas, Bruijnzeels & Foets, 2006). Conversely,

self-assessed health may be considered a sensitive and precocious marker of health deterioration

among immigrants: health selection is stronger for chronic and severe conditions, and several

studies found relatively better health outcomes for immigrants on indicators such as mortality,

chronic conditions or impaired activity than with self-assessed health (Vissandjee et al., 2004;

Leung, Luo, So & Quan, 2007; Lu, 2008; Puigpinós, 2008). With the HIS data too, we found

that the foreign-poor performed relatively better on an indicator of chronic limitation than on

self-assessed health; and equal or worse on mental health measured with the GHQ-12 (data not

shown). In summary, the use of self-assessed health to compare natives’ and immigrants’ health

seems reasonable, even though adding other, not necessarily more valid (Quesnel-Vallée, 2007),

health indicators to the analysis could help to give a more complete picture.

In conclusion, the present study shows how disadvantaged migration emerges as a health

inequality mechanism, in addition to and interacting with gender and social class, and especially

evident in women. These inequalities are in line with existing geographical inequities that affect

some (not all) immigrant groups. Evidence is given from a large immigrant group such as the

one from within Spain, with long duration of residence, so lessening the influence of the healthy

immigrant effect, and quite similar cultural background, so making acculturation an unlikely

cause. Future research and policies on the health of new immigrants can not ignore class, gender

and territorial inequality and the health trajectory perspective; and should make surveillance of

socio-economic conditions as a predictor of future health and a target of policies for health

equity.

16

Acknowledgement

This work was undertaken as part of Davide Malmusi's doctoral dissertation at the Universitat

Pompeu Fabra. Davide Malmusi was partially supported by the IV grant for young

epidemiologists "Enrique Nájera" awarded by the Sociedad Española de Epidemiología and

sponsored by the Escuela Nacional de Sanidad.

17

References

Abraído-Lanza, A. F., Chao, M. T., & Flórez, K. R. (2005). Do healthy behaviors decline with

greater acculturation? Implications for the Latino mortality paradox. Social Science and

Medicine, 61(6), 1243-55.

Agyemang, C., Denktas, S., Bruijnzeels, M., & Foets, M. (2006). Validity of the single-item

question on self-rated health status in first generation Turkish and Moroccans versus native

Dutch in the Netherlands. Public Health, 120, 543-550.

Almeida-Filho, N., Lessa I, Magalhães L, et al. (2004). Social inequality and depressive

disorders in Bahia, Brazil: interactions of gender, ethnicity, and social class. Social Science

and Medicine, 59(7), 1339-53.

Anthias, F. (2001). The material and the symbolic in theorizing social stratification: issues of

gender, ethnicity and class. British Journal of Sociology, 52(3), 367-390.

Bago-d’Uva, T., O’Donnell, O., & van Doorslaer, E. (2008). Differential health reporting by

education level and its impact on the measurement of health inequalities among older

Europeans. International Journal of Epidemiology, 37, 1375-83.

Borrell, C., Benach, J., & CAPS-FJ Bofill Working Group (2006). [Evolution of health

inequalities in Catalonia [Spain]]. Gaceta Sanitaria, 20, 396-406. Spanish.

Borrell, C., Muntaner, C., Solà, J., et al. (2008). Immigration and self-reported health status by

social class and gender: the importance of material deprivation, work organization and

household labour. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 62, e7.

Boyle, P., Cooke, T.J., Halfacree, K., & Smith, D. (2001). A cross-national comparison of the

impact of family migration on women's employment status. Demography, 38, 201-13.

Castles, S. (2003). The International Politics of Forced Migration. Development (Houndmills),

46(3), 11–20.

Chandola, T. & Jenkinson, C. (2000). Validating self-rated health in different ethnic groups.

Ethnicity and Health, 5, 2.

Clarke, P., O’Malley, P. M., Johnston, L. D., & Schulenberg, J. E. (2009). Social disparities in

BMI trajectories across adulthood by gender, race/ethnicity and lifetime socio-economic

position: 1986-2004. International Journal of Epidemiology, 38, 499-509. CSDH (2008). Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social

determinants of health. Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health.

Geneva: World Health Organization. Available at:

http://www.who.int/social_determinants/final_report/en/index.html

Davey Smith, G. (2000). Learning to live with complexity: ethnicity, socio-economic position

and health in Britain and in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 90, 1694-

8.

Domingo-Salvany, A., Regidor, E., Alonso, J., & Alvarez-Dardet, C. (2000). Proposal for a

social class measure. Working Group of the Spanish Society of Epidemiology and the

Spanish Society of Family and Community Medicine [Article in Spanish]. Atención

Primaria, 25, 350-63.

Escobar, J. I., Hoyos Nervi, C., & Gara, M. A. (2000). Immigration and mental health: Mexican

Americans in the United States. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 8, 64-72.

Gee, G. C., Ryan, A., Laflamme, D. J., & Holt, J. (2006). Self-reported discrimination and

mental health status among African descendants, Mexican Americans, and other Latinos in

the New Hampshire REACH 2010 Initiative: the added dimension of immigration.

American Journal of Public Health, 96, 1821-8.

Harris, R., Tobias, M., Jeffreys, M., Waldegrave, K., Karlsen, S., & Nazroo, J. (2006). Effects

of self-reported racial discrimination and deprivation on Māori health and inequalities in

New Zealand: cross-sectional study. Lancet, 367, 2005-9.

Herrero, C., Soler, A., & Villar, A. (2005). El índice de desarrollo humano en España, 1981-

2000. Capital Humano (num.49, 2005), Bancaja, Valencia.

Hernández-Quevedo, C. & Jiménez-Rubio, D. (2009). A comparison of the health status and

health care utilization patterns between foreigners and the national population in Spain:

18

New evidence from the Spanish National Health Survey. Social Science and Medicine, 69,

370-8.

Hjern, A., Wicks, S., & Dalman, C. (2004). Social adversity contributes to high morbidity in

psychoses in immigrants—a national cohort study in two generations of Swedish residents.

Psychological Medicine, 34, 1025-33.

Hosper, K., Nierkens, V., Nicolaou, M., & Stronks, K. (2007). Behavioural risk factors in two

generations of non-Western migrants: do trends converge towards the host population?

European Journal of Epidemiology, 22, 163-72.

Idescat (2008). Banc d'estadístiques de municipis i comarques [data file]. Retrieved from

http://www.idescat.cat/en/ at: Population > Nature of population. Ongoing local census >

Lloc de naixement per sexe i edat.

Leung, B., Luo, N., So, L., & Quan, H. (2007). Comparing Three Measures of Health Status

(Perceived Health With Likert-Type Scale, EQ-5D, and Number of Chronic Conditions) in

Chinese and White Canadians. Medical Care, 45(7), 610-617.

Levecque, K., Lodewyckx, I., & Vranken, J. (2007). Depression and generalised anxiety in the

general population in Belgium: A comparison between native and immigrant groups.

Journal of Affective Disorders, 97, 229-239.

Lindström, M., Sundquist, J., & Östergren, P. O. (2001). Ethnic differences in self reported

health in Malmö in southern Sweden. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 55,

97-103.

Lu, Y. (2008). Test of the ‘healthy migrant hypothesis’: A longitudinal analysis of health

selectivity of internal migration in Indonesia. Social Science and Medicine, 67, 1331-9.

Lutsey, P. L., Diez Roux, A. V., Jacobs Jr, D. R. et al. (2008). Associations of acculturation and

socioeconomic status with subclinical cardiovascular disease in the Multi-Ethnic Study of

Atherosclerosis. American Journal of Public Health, 98, 1963-70.

Lynam, M.J. (2004). Marginalization of First Generation Immigrant Women: An Experience

With Implications for Health [doctoral thesis], London: King’s College.

Kolcić, I. & Polasek, O. (2009). Healthy migrant effect within Croatia. Collegium

Antropologicum, 33 Suppl 1, 141-5.

Krieger, N. (2003). Does racism harm health? Did child abuse exist before 1962? On explicit

questions, critical science, and current controversies: an ecosocial perspective. American

Journal of Public Health, 93(2), 194-199.

Manderbacka, K., Lahelma, E., & Martikainen, P. (1998). Examining the continuity of self-

rated health. International Journal of Epidemiology, 27, 208-213.

Manor, O., Matthews, S., & Power, C. (2000). Dichotomous or categorical response? Analysing

self-rated health and lifetime social class. International Journal of Epidemiology, 29, 149-

157.

Marmot, M. G., Adelstein, M. A., & Bulusu, L. (1984). Lessons from the study of immigrant

mortality. Lancet, 323, 1455–1457.

McFadden, E., Luben, R., Bingham, S., Wareham, N., Kinmonth, A. L., & Khaw, K. T. (2008).

Social inequalities in self-rated health by age: Cross-sectional study of 22 457 middle-aged

men and women. BMC Public Health, 8, 230.

Nazroo, J. Y. (2003). The structuring of ethnic inequalities in health: economic position, racial

discrimination, and racism. American Journal of Public Health, 93(2), 277-84.

Newbold, K. B. (2005). Self-rated health within the Canadian immigrant population: risk and

the healthy immigrant effect. Social Science and Medicine, 60(6), 1359-70.

Newbold, K. B. & Danforth, J. (2003). Health status and Canada’s immigrant population. Social

Science and Medicine, 57, 1981-95.

Pamuk, E., Makuc, D., Heck, K., Reuben, C., & Lochner, K. (1998). Socioeconomic Status and

Health Chartbook. Health, United States, 1998. Hyattsville, Maryland: National Center for

Health Statistics.

Pudaric, S., Sundquist, J., & Johansson, S. E. (2003). Country of birth, instrumental activities of

daily living, self-rated health and mortality: a Swedish population-based survey of people

aged 55-74. Social Science and Medicine, 56, 2493-2503.

19

Puigpinós, R. (coord.) (2008). La salut de la població immigrant de Barcelona. Barcelona:

Agencia de Salut Pública de Barcelona. Retrieved from

http://www.aspb.es/quefem/docs/salut_immigrants_BCN.pdf

Quesnel-Vallée, A. (2007). Self-rated health: caught in the crossfire of the quest for ‘true’

health ? International Journal of Epidemiology, 36, 1161-4.

Raftery, J., Jones, D. R., & Rosato, M. (1990). The mortality of first and second generation Irish

immigrants in the U.K.. Social Science and Medicine, 1990, 31(5), 577-584.

Rasch, V., Gammeltoft, T., Knudsen, L. B., Tobiassen, C., Ginzel, A., & Kempf, L. (2008).

Induced abortion in Denmark: effect of socio-economic situation and country of birth.

European Journal of Public Health, 18(2), 144-9.

Redstone Akresh, I. & Frank, R. (2008). Health selection among new immigrants. American

Journal of Public Health, 98(11), 2058-64.

Reijneveld, S. A. (1998). Reported health, lifestyles, and use of health care of first generation

immigrants in The Netherlands: do socioeconomic factors explain their adverse position?

Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 52(5), 298-304.

Ronellenfitsch, U. & Razum, O. (2004). Deteriorating health satisfaction among immigrants

from Eastern Europe to Germany. International Journal for Equity in Health, 3, 4.

Sanchez-Vaznaugh, E. V., Kawachi, I., Subramanian, S. V., Sánchez, B. N., & Acevedo-Garcia,

D. (2008). Differential effect of birthplace and length of residence on body mass index

(BMI) by education, gender and race/ethnicity. Social Science and Medicine, 67, 1300-10.

Schulz, A.J. & Mullings, L. (Eds.). (2006). Gender, Race, Class, and Health. Intersectional

approaches. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Solar, O. & Irwin, A. (2007). A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of

health. Discussion paper for the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva,

World Health Organization.

Solé, C. (2000). Inmigración interior e inmigración exterior. Papers, 60, 211-224.

Tinghog, P., Hemmingsson, T., & Lundberg, I. (2007). To what extent may the association

between immigrant status and mental illness be explained by socioeconomic factors? Social

Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 42(12), 990-6.

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2009).

International Migration Report 2006: A Global Assessment (p.xiv). New York: Author.

United Nations Development Programme (2006). Human Development Report 2006. Beyond

scarcity: power, poverty and the global water crisis (p.283). New York: Author.

United Nations Development Programme (2009). Human Development Report 2009.

Overcoming barriers: human mobility and development. New York: Author.

Uretsky, M. C. & Mathiesen, S. G. (2007). The Effects of Years Lived in the United States on

the General Health Status of California’s Foreign-Born Populations. Journal of Immigrant

and Minority Health. 2007;9:125-36

Van der Wurff, F. B., Beekman, A. T. F., Dijkshoorn, H., et al. (2004). Prevalence and risk-

factors for depression in elderly Turkish and Moroccan migrants in the Netherlands. Journal

of Affective Disorders, 83, 33–41.

Viruell-Fuentes, E. A. (2007). Beyond acculturation: Immigration, discrimination and health

research among Mexicans in the United States. Social Science and Medicine, 65, 1524-35.

Vissandjee, B., Desmeules, M., Cao, Z., Abdool, S., & Kazanjian, A. (2004). Integrating

ethnicity and migration as determinants of Canadian women’s health. BMC Women's

Health, 4, S32.

Vives, A., Amable, M., Ferrer, M., Moncada, S., Llorens, C., Muntaner, C., ... Benach, J.

(2010). The Employment Precariousness Scale (EPRES): Psychometric properties of a new

tool for epidemiological studies among waged and salaried workers. Occupational and

Environmental Medicine, in press.

Westman, J., Martelin, T., Härkänen, T., Koskinen, S., & Sundquist, K. (2008). Migration and

self-rated health: a comparison between Finns living in Sweden and Finns living in Finland.

Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 36, 698.

Wild, S. & McKeigue, P. (1997). Cross sectional analysis of mortality by country of birth in

England and Wales, 1970-92. British Medical Journal, 314, 705.

20

Table 1. Socio-economic conditions and health status according to social class and

migration type, stratified by sex. Living Conditions Survey Health Interview Survey

N Age Material

deprivation

Low

income c

Precarious

employment c

Poor

health

N Age Poor

health

mean %b %

b %

b %

b mean %

b

Social class a

Women I 319 38.6 7.4 7.9 15.8 11.8 467 39.1 12.3

II 425 40.2 15.8 20.2 17.5 21.2 522 39.9 11.8

III-nm 751 37.8 17.1 30.5 19.6 21.3 1010 40.1 17.7

III-m 187 43.0 33.8 41.3 41.4 29.2 332 45.6 23.5

IV 1316 41.6 49.4 67.2 40.1 32.2 2054 43.7 27.7

V 492 44.0 64.1 81.8 62.0 41.6 636 46.5 40.2

Men I 389 40.7 3.8 3.0 13.2 9.3 550 41.6 7.8

II 451 39.4 14.1 7.4 19.8 14.2 479 40.8 10.9

III-nm 500 40.5 17.4 8.7 17.0 14.1 661 42.3 11.1

III-m 335 43.6 28.8 12.4 25.6 16.8 655 44.1 14.3

IV 1651 40.4 45.8 17.4 30.5 26.4 2468 42.0 19.3

V 263 38.4 69.6 35.4 42.4 26.2 462 40.9 20.1

Origin

Women Natives 2254 38.7 27.2 39.0 26.2 23.4 3562 40.5 19.9

Spain-

wealthy

61 42.4 29.1 22.5 15.0 25.6 56 44.2 42.7

Spain-

average

168 46 33.1 34.7 35.0 29.4 210 50.4 23.2

Spain-poor 596 49 50.2 63.4 37.9 40.4 819 50.8 33.9

Foreign-

advanced

53 41.3 18.8 36.0 28.5 18.7 81 39.8 16.8

Foreign-

poor, less

recent

159 38.8 69.0 57.3 51.6 27.4 153 39.7 39.8

Foreign-

poor,

recent

219 33.6 70.4 77.1 82.9 33.4 205 35.6 31.7

Men Natives 2333 38.3 25.0 12.5 26.7 18.7 3728 39.8 14.2

Spain-

wealthy

48 43.6 35.4 3.7 13.1 13.1 62 43.9 10.0

Spain-

average

152 46.9 23.9 4.2 12.4 18.1 213 48.7 13.6

Spain-poor 597 49.2 39.1 11.9 23.7 24.7 801 51.4 22.0

Foreign-

advanced

46 37.9 24.0 14.9 46 16.9 77 38.7 12.5

Foreign-

poor, less

recent

182 37.3 71.0 25.6 52.5 23.5 186 40.9 18.4

Foreign-

poor,

recent

239 33.1 79.0 38.8 67 20.9 255 35.0 8.1

a Social class could not be coded in 20 women and 8 men in the LCS, and in 65 women and 47 men in the HIS. b Predicted probabilities at age 45 obtained from logistic regression models. c Restricted to subjects in paid job.

21

Table 2. Sample distribution in the matrix of sex/social class/migration type. Living

Conditions Survey.

Non-manual III-m IV Unskilled

N Column % N Column % N Column %

Women

Natives 1192 79.7 880 58.5 171 34.8

Spain-rich 108 7.2 88 5.9 33 6.7

Spain-poor 102 6.8 342 22.8 146 29.7

Foreign-advanced 33 2.2 17 1.1 3 0.6

Foreign-poor 60 4.0 176 11.7 139 28.3

Men

Natives 1025 76.5 1186 59.7 117 44.5

Spain-rich 98 7.3 94 4.7 6 2.3

Spain-poor 141 10.5 406 20.4 50 19.0

Foreign-advanced 21 1.6 24 1.2 1 0.4

Foreign-poor 55 4.1 276 13.9 89 33.8

22

Table 3. Odds ratio of fair/poor health according to migration type, adjusted by potential mediators (logistic regression models). LCS survey.

N Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4 Model 5

Sex and origin AGE +CLASS +MATERIAL +INCOME +JOB

Women OR 95% CI OR 95% CI OR 95% CI OR 95% CI OR 95% CI

Natives 2254 1 1 1 1 1

Spain-rich 229 1.27 (0.93-1.72) 1.25 (0.91-1.71) 1.21 (0.87-1.67) 1.23 (0.89-1.70) 1.17 (0.85-1.62)

Spain-poor 596 2.11*** (1.73-2.59) 1.67*** (1.35-2.06) 1.49*** (1.20-1.86) 1.50*** (1.21-1.86) 1.48*** (1.19-1.85)

Foreign-advanced 53 0.76 (0.36-1.58) 0.84 (0.40-1.76) 0.90 (0.43-1.89) 0.89 (0.42-1.88) 0.85 (0.40-1.79)

Foreign-poor, less recent 159 1.25 (0.85-1.85) 0.90 (0.60-1.34) 0.64* (0.42-0.98) 0.65* (0.43-0.99) 0.67 (0.44-1.02)

Foreign-poor, recent 219 1.70*** (1.19-2.42) 1.19 (0.82-1.73) 0.84 (0.57-1.23) 0.83 (0.56-1.22) 0.88 (0.60-1.30)

Men

Natives 2333 1 1 1 1 1

Spain-rich 200 0.91 (0.62-1.32) 0.88 (0.60-1.30) 0.83 (0.56-1.23) 0.89 (0.59-1.33) 0.84 (0.56-1.26)

Spain-poor 597 1.48*** (1.19-1.84) 1.20 (0.96-1.51) 1.07 (0.85-1.35) 1.15 (0.91-1.46) 1.17 (0.92-1.48)

Foreign-advanced 46 0.89 (0.38-2.08) 0.89 (0.37-2.10) 0.88 (0.37-2.10) 0.87 (0.36-2.07) 0.85 (0.35-2.03)

Foreign-poor, less recent 182 1.30 (0.86-1.96) 1.00 (0.66-1.52) 0.60* (0.39-0.93) 0.59* (0.38-0.93) 0.60* (0.38-0.95)

Foreign-poor, recent 239 1.10 (0.73-1.67) 0.81 (0.53-1.24) 0.49** (0.32-0.76) 0.44*** (0.28-0.68) 0.45** (0.29-0.71) * p<0,05. ** p<0,01. ***p<0,001.

Model 1: Adjusted by age (5-years categories). Model 2: Model 1 + social class (I, II, III-nm, III-m, IV, V, not coded).

Model 3: Model 2 + material index (linear).

Model 4: Model 3 + individual monthly income ( >900€, <900€, no income, irregular or non-response).

Model 5: Model 4 + employment status and conditions (Secure job, precarious job, not employed).

23

Figure 1. Socio-economic conditions and health status according to the matrix of

sex/social class/migration type.

Predicted probabilities at age 45 obtained from logistic regression models.

In less than good health, the two columns of the same colour represent data from the HIS and the LCS for the same group.

Estimations of low income and precarious employment are restricted to subjects in paid job.

24

Figure 2. Risk of fair/poor health according to migration type, adjusted by potential

mediators. (2a) Women, (2b) Men.

Source: Living Conditions Survey. Odds Ratio obtained from logistic regression models. Model 1: Adjusted by age (5-years categories).

Model 2: Model 1 + social class (I, II, III-nm, III-m, IV, V).

Model 3: Model 2 + material index (linear).

Further adjustments hardly modified the associations.