Measuring destination competitiveness: multiple destinations versus multiple nationalities

-

Upload

metinkozak -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of Measuring destination competitiveness: multiple destinations versus multiple nationalities

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

This article was downloaded by: [TÜBİTAK EKUAL]On: 18 November 2009Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 772815468]Publisher RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Journal of Hospitality Marketing & ManagementPublication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information:http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t792306863

Measuring Destination Competitiveness: Multiple Destinations VersusMultiple NationalitiesMetin Kozak a; Şeyhmus Baloğlu b; Ozan Bahar c

a School of Tourism and Hospitality Management, Muğla University, Muğla, Turkey b Tourism andConvention Department, William F. Harrah College of Hotel Administration, University of Nevada,Las Vegas, Las Vegas, Nevada, USA c Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences, MuğlaUniversity, Muğla, Turkey

To cite this Article Kozak, Metin, Baloğlu, Şeyhmus and Bahar, Ozan'Measuring Destination Competitiveness: MultipleDestinations Versus Multiple Nationalities', Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 19: 1, 56 — 71To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/19368620903327733URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19368620903327733

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf

This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial orsystematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply ordistribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contentswill be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug dosesshould be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss,actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directlyor indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

56

Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 19:56–71, 2010Copyright © Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 1936-8623 print/1936-8631 onlineDOI: 10.1080/19368620903327733

WHMM1936-86231936-8631Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, Vol. 19, No. 1, Oct 2009: pp. 0–0Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management

Measuring Destination Competitiveness: Multiple Destinations Versus Multiple

Nationalities

Measuring Destination CompetitivenessM. Kozak et al.

METIN KOZAKSchool of Tourism and Hospitality Management, Mugla University, Mugla, Turkey

SEYHMUS BALOGLUTourism and Convention Department, William F. Harrah College of Hotel Administration,

University of Nevada, Las Vegas, Las Vegas, Nevada, USA

OZAN BAHARFaculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences, Mugla University, Mugla, Turkey

Over the past few decades, studies on competitiveness have generallyfocused on examining the exportation success of goods-producingor manufacturing firms rather than the service industry, includ-ing tourism. This study develops a practical method for measuringthe direct competitive position of one country compared to othersimilar countries in the same competitiveness set. In this respect,the competitive position of Turkey was studied relative to two othercountries in the Mediterranean area. The countries, which areself-selected by the foreign tourists visiting Turkey and nominatedas the direct competitors to Turkey, include Spain and Greece. Thestudy also reports the findings of a cross-national comparisonfrom the perspective of tourism demand. Respondents includethose from Britain, Netherlands, and Germany. In so doing, thedestination managers may be able to understand the level of theirown performance as compared to their major competitors withmultiple segments of the market. Implications for the theory andpractice are also discussed.

Address correspondence to Seyhmus Baloglu, Tourism and Convention Department,William F. Harrah College of Hotel Administration, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, 4505Maryland Parkway, P.O. Box 456023, Las Vegas, NV 89154-6023, USA. E-mail: [email protected]

Downloaded By: [TÜBTAK EKUAL] At: 12:43 18 November 2009

Measuring Destination Competitiveness 57

KEYWORDS Destination competitiveness, cross-national com-parison, benchmarking, competitiveness monitors, Mediterraneantourism

INTRODUCTION

Over the past few decades, while studies on competition have focused gen-erally on examining the exportation success of goods-producing or manu-facturing firms, studies on the service industry, including tourism, haveremained limited. Accordingly, we know very little about both the serviceindustry and competition in tourism destinations. Nevertheless, the increasingweight of tourism in industrialized countries of today, counting for 60–70% oftheir GNP, has resulted in rising competition in this industry. The latestfigures update that the Mediterranean region has a share of 31.6% in inter-national tourism in terms of the number of tourists (WTO, 2004). The coun-try with the largest market share out of the region is France with a share of34.1%, followed by Spain, Italy, Greece, and Turkey, respectively. With ashare of 6.0%, Turkey is the fifth biggest country in the region. The estimationsof WTO for 2010 and 2020 reveal that it would be possible to see Turkey, withan annual growth rate of 5.5%, as the third fastest growing country afterYugoslavia and Egypt. According to the estimations of the World Travel andTourism Coucil (WTTC), in a period when the regional growth rate of theEuropean market is decreasing, the growth rate of the Mediterranean marketwill also be slower. Tourism competition or competitiveness has often beendefined as the strength or ability of a destination to provide a quality expe-rience to the visitors and quality of life to the local people by developingsustainable advantages and market share (d’Hauteserre, 2000; Ritchie &Crouch, 2003; Enrigth & Newton, 2004).

A review of significant number of studies on tourism competitivenessrevealed that a more valid assessment of tourist destination competitivenessshould compare the destination with more than two destinations and exam-ine it from perspectives of the multiple nationalities, although the latterissue has been underestimated so far in the previous empirical studies (i.e.Kozak, 2004; Mangion, Durbarry, & Sinclair, 2005; Campos-Soria, Garcia, &Garcia, 2005). With consideration to the potential gap in past research, theprimary purpose of this study is to develop a practical method for measur-ing the direct competitive position of one country as a tourist destinationcompared to other countries in the same competitiveness set. This articlefirst examines past research on destination competitiveness and comparisonon the basis of their contents, strengths, and limitations. Then, it presents thedevelopment of methodology which has been applied to measuring the com-petitiveness of Turkey. The discussion of findings is based on the data col-lected through a survey conducted among those three European nationalities

Downloaded By: [TÜBTAK EKUAL] At: 12:43 18 November 2009

58 M. Kozak et al.

of tourists visiting Turkey in the summer of 2004. Finally, the study findingshave been compared with the indicators of competitiveness index developedby the WTTC.

LITERATURE REVIEW

In general terms, destinations are often seen as the geographical regionsserving integrated services to tourists and are composed of the combinationof the tourism products or the places with distinct natural attractiveness andproperties that may be appealing to the tourists (Buhalis, 2000). A proposedtourist destination may be a country or a continent, city, town, an island, orplaces with natural and outstanding landscapes. This study considers coun-tries as a tourism destination from macro economic and marketing perspec-tives. The literature has evidence to suggest that tourists have similarperceptions of different destinations in the same country or they sometimeshave intentions to visit other places in the same country due to the per-ceived homogenous structure of cultural and natural resources all over thecountry (Mill & Morrison, 1992; Kozak, 2001).

Tourism Destination Competitiveness

Competition may range from its meaning among nations and firms to itsfunctions among destinations due to the effect of globalization. However,there are not any determining factors of the destination competition. In thisrespect, the literature presents various definitions of tourism (destination)competition. In one definition, tourism competition refers to the ability offacilities providing a high standard of living to the inhabitants of a tourismregion—the competitive power of that place (Ritchie & Crouch, 2003).Another definition states that tourism competition is the ability of a destina-tion to attract the possible tourists to its region and satisfy their needs andwants (Enrigth & Newton, 2004). According to a final definition, tourismcompetition is the ability of a destination to sustain its market share andpower, protecting and developing it in time (d’Hauteserre, 2000). All thesedefinitions underline a period through which competition is ongoing; that isthey cover a dynamic period, that the level of prosperity of the local peoplecan be increased and customers (tourists) can be satisfied at the highestlevel.

On the other hand, the review of literature clearly indicates that there isnot a certain definition of competition upon which is commonly agreed andwhich has a complete and perfect content (Chon & Mayer, 1995). This isbecause it is almost impossible to integrate the characteristics of a number ofcountries and firms and to distinguish some of them. Furthermore, the competi-tion itself is a concept that includes perspectives in various disciplines such

Downloaded By: [TÜBTAK EKUAL] At: 12:43 18 November 2009

Measuring Destination Competitiveness 59

as a price competition perspective, a strategy and management perspective,and a historical and sociocultural perspective, as well as a comparativeadvantages perspective (Man, Lau, & Chan, 2002). The major reason forattempting to develop a model of competitiveness that focuses specificallyon the tourism industry is that there appears to be a fundamental differencebetween the nature of the tourism product and the more traditional goodsand services. Unlike a specific manufacturing product, competition amongtourism destinations has a much different structure in terms of an integra-tion of all the characteristics of the destination visited (Vanhove, 2006),which include the integration of 41 different sectors consisting of somesmall and some big branches of business which supply individual productsand services (e.g. airlines, seaways, railways, rental car companies, travelagencies, intermediaries, restaurants, and convention centers; Lundberg,Stavenga, & Krishnamoorthy, 1995).

Competitiveness Research in Hospitality and Tourism

Competitiveness in the tourism industry has shifted from interfirm competi-tiveness to interdestination competitiveness through the impacts of global-ization. However, there are no special factors relating to interpreting thedeterminants of destination competitiveness. Tourism competitiveness is ageneral concept that encompasses price differentials coupled with exchangerate movements, productivity levels of various components of the touristindustry, and qualitative factors affecting the attractiveness or otherwise of adestination (Dwyer, Forsyth, & Rao, 2002). While it is known that the firststudies on tourism competitiveness that cover a significant proportion of thetourism literature have been conducted by several researchers within thelast few decades (Haahti & Yavas, 1983; Heath & Wall, 1992; Kozak &Rimmington, 1999; Baloglu & McCleary, 1999; Papatheodorou, 2002; Enright &Newton, 2004), the most comprehensive study so far is that of Ritchie andCrouch (2003). They applied the competitiveness of the service industry tothe context of tourism destinations on the basis of countries, industries,products, and companies. To this end, the possibilities of a destination pro-viding a high standard of living for its citizens represent the competitivenessof that destination.

As seen, competitiveness has become the focus of considerationamount of empirical studies in tourism and hospitality, particularly in thelast decade. An extensive review of the literature indicated that much hasbeen written about competitiveness between different tourist destinationseither at the regional, national, or international level (e.g. Hsu, Wolfe, &Kang, 2004; Enright & Newton, 2004; Yoon, 2002; Driscoll, Lawson, &Niven, 1994; Gursoy & Kendall, 2004; Dwyer et al., 2002; Papatheodorou,2002). Some studies have attempted to estimate the competitive position oftourist destinations from the perspective of using quantitative measures (i.e.

Downloaded By: [TÜBTAK EKUAL] At: 12:43 18 November 2009

60 M. Kozak et al.

Mangion et al., 2005; Papatheodorou, 2002; Gursoy & Kendall, 2004). Thebody of research usually deals with the assessment of secondary data suchas prices, number of tourist arrivals, income, etc. The second group of stud-ies has taken the perspective of employing qualitative measures attemptingto carry out a “one-by-one test” procedure for direct comparison (i.e.Enright & Newton, 2004, 2005; Yoon, 2002; Driscoll et al., 1994). It is alsointeresting to note the existence of some other studies making use of bothquantitative and qualitative measures (Campos-Soria, Garcia and Garcia,2005).

Given brief information about the findings of such studies, for exam-ple, in a study of Mangion et al. (2005), the findings confirmed that theprice sensitiveness of tourism demand varies from one destination toanother; thereby, Malta and Cyprus are considered complementary ratherthan substitute target destinations by the U.K. tourist market. Through theDuplication of Purchase Law and using primary data, Mansfeld and Romaniuk(2002) suggest that Scotland and Ireland compete more directly for theBritish market due to the position of their neighborhood locations. Thesame is also true for other substitute countries such as France and Italy,Hong Kong and Singapore, and Mexico and Canada. Contrary to this argu-ment, through the Market Share Analysis and using secondary data, Aguas,Rita, and Costa (2004) identified that France, Greece, and Spain come outas the winners, whilst Italy and Portugal are the losers in the competitiveposition of the EU member countries in a period of six years between1996 and 2001. In the context of evaluating business-to-business competi-tive performance, Campos-Soria et al. (2005) note that service quality hasnot only a positive and direct effect but also an indirect effect on compet-itiveness via other variables such as occupancy rates and average directcosts.

Although some literature is available concerning the relevance of severalcompetitiveness measurement models to the tourism and hospitality industry,it is still limited with respect to their relevance to practitioners, i.e. tourismauthorities and service providers. Therefore, in a broader context of destina-tion competitiveness measurement research, there is a potential evidence tosupport the argument that a destination needs to be compared with morethan two destinations and the input of multiple nationalities m ust be con-sidered, although the latter issue has been underestimated so far in the pastempirical studies (i.e. Kozak, 2004; Mangion et al., 2005; Campos-Soriaet al., 2005). In so doing, both destination authorities and tourism serviceproviders may be able to better understand the level of their own perfor-mance not only against one specific destination but also against their majorrivals from the perspective of their culturally-diverse customer profiles. Forexample, through the perceptions of the tourist group “X” one destinationmay be more competitive than another while less competitive for the touristgroup “Y”.

Downloaded By: [TÜBTAK EKUAL] At: 12:43 18 November 2009

Measuring Destination Competitiveness 61

METHODOLOGY

A questionnaire including three sections was developed through a review ofprevious literature (e.g. Kozak & Rimmington, 1999). The first part aimed toidentify 11 other Mediterranean destinations the respondents had visited at leastonce. The second part was designed to allow the respondents to choose fromthose destinations to compare with their current holiday. Respondents had tochoose only one foreign destination for the comparison. In the third part, therespondents compared Turkey on 23 attributes with the destination theyselected to understand what attributes of their current trip in Turkey were per-ceived to more or less competitive than the selected paired destination (positiveor negative aspects of tourism). They were asked to evaluate the competitiveposition of Turkey compared to the country on a 5-point scale (1 = muchworse, 2 = worse, 3 = about the same, 4 = better, 5 = much better). A “don’tknow” option was also labeled on the scale for those who might not have anyopinion about their experiences with any of the destination attributes. Aneconometric study of tourism demand suggests that the Mediterranean coun-tries provide both substitute and complementary products for those in the west-European countries (Syriopulos & Sinclair, 1993). The paired countries nomi-nated as the direct competitor to Turkey include Spain, Italy, Greece, France,and Cyprus. These countries were self-selected by respondents.

Sampling and Procedure

The population for this study consisted of international tourists visiting thesouthwest part of Turkey for the purpose of pleasure or a summer vacation.With the assistance of two trained interviewers, the inclusion of the authors, andthe cooperation of the airport authority, the survey was carried out at two inter-national airports operating in the province of Mugla. Questionnaires were deliv-ered at each airport’s departure lounge upon tourists completed their check-inprocedures. No particular attempt was made to apply a random sampling. In thisresearch, it is expected that sample populations have direct experience in orderto respond accurately to questions regarding their holiday experiences in eachdestination. Otherwise, findings do not accurately reflect the performance ofdestinations on specific attributes. Thus, there is a need for a better understand-ing of tourists’ judgments in measuring competitive destination performance.Tourists were selected at different times of the day in order to obtain a morerepresentative sample. By the given time, a total of 881 questionnaires werecollected through the end of a four-week period in July and August of 2004.

Data Analysis

Using the SPSS 14.0 program, various statistical techniques were conductedto analyze the data. First, reliability analysis (Cronbach’s alpha) was performed

Downloaded By: [TÜBTAK EKUAL] At: 12:43 18 November 2009

62 M. Kozak et al.

to test the reliability and internal consistency of the survey instrument. Sub-sequently, factor analysis was used to reduce the data into meaningfuldimensions and create some major factor labels. Finally, a two-way MANOVAwas utilized to examine the main and interaction effects of respondents’nationality and the reference destination (Greece and Spain) used in evalu-ating the comparative perceptions of Turkey. The analysis of data is alsobased on the employment of various statistical tests, applied elsewherewhen required, e.g. the Tamhane post hoc test, Pillai’s Trace and Wilk’slambda, Scheffe tests.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Although the initial intention was to consider all the 11 Mediterranean coun-tries in the competitiveness analysis of Turkey, only those ranked top two inthe list were selected for comparison due to their larger sample size, namelySpain and Greece. The rest had small sample size (see Table 1). Nearly one-third of the respondents (foreign visitors) had no previous experience inTurkey (28.3%). This was similar to the ratio for Spain (24.6%), France(34.6%), and Greece (39.0%). On the other hand, approximately half of therespondents had not been to Italy (48.4%) and Cyprus had the largestnumber of nonvisitors (71.5%). As Table 2 shows, the majority of the samplepopulation had a very recent visit to the countries under investigation. Thisfinding indicated some recency effect and provided further support for reli-ability as the respondents tend to make a comparison between the pairedcountries, bearing in mind their most recent experiences in the self-nominatedpartner country.

TABLE 1 Distribution of Visited Countries

Countries

Tourists

Rank N %

Spain 1 267 30.3Greece 2 267 30.3Subtotal 534 60.6Italy 3 73 8.3France 4 64 7.3Cyprus 5 49 5.6Portugal 6 47 5.3Egypt 7 40 4.5Tunisia 8 30 3.4Yugoslavia 9 19 2.2Morocco 10 13 1.5Malta 11 12 1.4

Total 881 100.0

Downloaded By: [TÜBTAK EKUAL] At: 12:43 18 November 2009

Measuring Destination Competitiveness 63

A profile of the respondents by origin countries was shown in Table 3.British tourists appear to be older and have higher incomes than Germanand Dutch/Holland tourists. There were also variations in accommodationtype preferences. Most of British tourists have stayed in self catering and bedand breakfast properties while German and Dutch/Holland tourists have

TABLE 2 The Distribution of the Latest Visits to the Selected Countries byYears (%)

Prior to 1990 1990–1994 1995–1999 2000–2004 No response Total

2.1 3.0 12.9 73.6 8.4 100.0

TABLE 3 Profile of Respondents by Origin Countries

British Dutch/Holland German

Age15–24 7.8 36.6 8.625–34 15.6 22.1 28.435–44 29.7 24.1 27.245–54 32.3 14.4 29.655–64 12.7 2.8 6.265 and over 1.9 0.0 0.0

Total 100.0 100.0 100.0

IncomeUnder 5.000 € 1.4 21.7 18.35.000–9.999 € 1.4 10.8 5.010.000–14.999 € 5.4 6.7 1.715.000–19.999 € 5.0 4.2 8.320.000–24.999 € 7.1 6.7 6.725.000–29.999 € 13.5 4.2 10.030.000–39.999 € 21.2 15.7 16.740.000 € and over 45.0 30.0 33.3

Total 100.0 100.0 100.0

Type of accommodationAll-inclusive 16.3 42.4 54.3Half board 15.9 16.7 28.4Self-catering 30.3 9.7 1.3Flight only 8.3 0.7 5.0Full board 3.0 0.7 8.6Bed and breakfast 25.8 6.9 1.2Room only 0.4 22.9 1.2

Total 100.0 100.0 100.0

How far in advance bookedLess than a week 9.2 6.4 10.01–4 weeks 22.9 27.0 48.71–3 months 20.2 15.6 21.34–6 months 23.7 46.0 12.57 months and longer 24.0 5.0 7.5Total 100 100.0 100.0Length of holiday (days) 14.65 12.69 12.68

Downloaded By: [TÜBTAK EKUAL] At: 12:43 18 November 2009

64 M. Kozak et al.

preferred all inclusive concepts during their visit. German tourists (1–4 weeks)are more likely to book their vacation earlier than Dutch/Holland tourists(4–6 months).

Table 4 summarizes the results of factor analysis used to reduce the data.Reliability analysis (Cronbach’s alpha) was performed to test the reliability andinternal consistency of the factor dimensions. This stage is precursor to avalid research in order to ensure that findings are accurate and be able todiscuss further implications. As Table 4 indicates, the scales are internallyreliable, ranging from 0.73 to 0.79. They all met the minimum standard(0.70) suggested by Nunnaly (1978).

The mean scores and two statistics were used to test if the factor analysiswas appropriate for this study (Hair, Anderson, Tatham, & Black, 1998).First, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) statistic was calculated as 0.86 which isexcellent. Second, Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity was conducted, yielding a sig-nificant chi-square value in order to test the significance of the correlationmatrix (c = 1373, p < .000). Both tests indicated that factor analysis wasappropriate for this study. The factor analysis explained 55.1% of the totalvariance. The first factor includes the availability of facilities and activities.The second factor is described with cultural and natural attractiveness. Thethird factor is associated with the quality of tourist services. The last factorwas related to the quality of infrastructure. The last column of Table 4 alsoincludes mean scores of the attributes. In general, Turkey’s most competi-tive attributes are hospitality, value for money, and quality of services.These attributes are very critical competitive forces for any destination intoday’s market.

A two-way MANOVA was conducted to examine the perceptual differ-ences across nationalities and if differences exist when comparing Turkey toGreece or Spain. The Tamhane post hoc test was chosen because (a) thebox’s test of equal variance assumption was significant at .01 level, indicat-ing that the assumption was violated, and (b) a conservative test wasselected to avoid Type I error (i.e. rejecting a true null hypothesis). Themultivariate tests such as Pillai’s Trace and Wilk’s lambda showed that maineffects of respondents’ nationality and destination with which Turkey wascompared (Greece and Spain) was significant at .001 level. These resultssuggest that there exist image differences across origin countries and differ-ences in Turkey’s image when compared to Greece and Spain regardless ofrespondents’ nationalities. The interaction between the respondents’ nation-ality and reference destination was not significant at .05 probability level,indicating that the respondents from the three nationalities provide more orless similar evaluations when comparing Turkey to Greece and Spain. How-ever, some interactions were found at .10 probablity level (Table 5). Thesefindings indicate that tourist destinations should develop competitive advan-tages for each origin market and against a particular competing destination.Cultural and Natural Attractiveness showed significant variations across

Downloaded By: [TÜBTAK EKUAL] At: 12:43 18 November 2009

Measuring Destination Competitiveness 65

TABLE 4 Factor Analysis of Destination Competitiveness Items

FactorsFactor loading Eigenvalue

Variance explained

Mean score F ratio Alpha

MeanScore

Factor 1: Availability of Facilities and Activities

7.82 34.02 3.36 30.44 0.78

Availability of sport activities and facilities

.68 3.30

Effectiveness of the promotion and publicity

.67 3.39

Suitability of nightlife and entertainment

.65 3.39

Standard of facilities and activities for children

.61 3.35

Availability of shopping facilities

.59 3.70

Standard of accommoda-tion facilities

.52 3.46

Distance to my home country

.46 2.85

Factor 2: Cultural and Natural Attractiveness

2.29 9.65 3.65 13.90 0.79

Attractiveness of historical sources

.79 3.77

Attractiveness of cultural sources

.77 3.69

Attractiveness of natural environment

.73 3.71

Diversity of tourism products

.67 3.62

Overall attractiveness .66 3.82Quality of sea and

beaches.44 3.47

Factor 3: Quality of Services 1.36 5.94 3.72 109.55 0.72Quality of services .74 3.81Standard of hygiene and

sanitation.62 3.26

Level of hospitality and friendliness

.60 4.15

Quality of local food and beverage

.53 3.66

Overall value for money .50 3.86

Factor 4: Quality of Infrastructure

1.20 5.22 3.36 10.20 0.73

Quality of banking services

.74 3.25

Quality of telecommunica-tion network

.73 3.20

Quality of health services .52 3.37Quality of the destination

airport.48 3.27

Quality of local transport network and services

.47 3.56

Note. Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy = .867; total variance explained at 55.1%.

Downloaded By: [TÜBTAK EKUAL] At: 12:43 18 November 2009

66 M. Kozak et al.

origin countries and based on the reference destination used by the respon-dents. However, Quality of Service was significantly different across origincountries whereas Quality of Infrastructure was significantly different whenTurkey was compared to different competitor destination.

To better understand the nature of the significant differences found,post hoc tests were used. The equality of variance assumption was not metfor Cultural and Natural Attractiveness. Therefore, Tamhane post hoc proce-dure was used for this factor grouping. For all others significant differences,Scheffe tests were used. Both Scheffe and Tamhane are more conservativetests when compared to their equivalent tests. In addition, the significancelevel (.05) was adjusted by the number of tests (Bonferroni correction). Anexamination of the main effects showed that German and British tourists eval-uated Turkey’s competitive position more positively than Dutch/HollandTourists. In addition, British tourists rated Turkey better than German andDutch/Holland tourists for Quality of Services. Not surprisingly, Turkey wasrated more competitive on Cultural and Natural Attractiveness when com-pared to Spain than it was to Greece. In contrary, for Quality of Infrastruc-ture, Turkey was perceived less competitive against Spain when comparedto Spain and Greece. Further, British and German tourists rated Turkeybetter than Dutch/Holland tourists for Cultural and Natural Attractivenesswhile British tourists evaluated Turkey’s competitive position for providingQuality of Services better than both Dutch/Holland and German tourists.The interaction effects indicated that the perceptions of Turkey by threenationalities varied based on the reference destination selected. When com-paring Turkey to Greece and Spain for Quality of Facilities and ActivitiesDutch/Holland and German tourists perceived Turkey more competitivewhen compared to Spain while Germans perceived Turkey more competi-tive when comparing it to Greece. For Quality of Services, unlike other

TABLE 5 Two-way MANOVA Results

Dependent variables F-Value p

Visitor group F1: Quality of facilities and activities 2.24 .107F2: Cultural and natural attractiveness 16.05 .000*F3: Quality of services 19.56 .000*F4: Quality of infrastructure 0.81 .443

Reference destination F1: Quality of facilities and activities 0.92 .338F2: Cultural and natural attractiveness 9.37 .002*F3: Quality of services 0.57 .450F4: Quality of infrastructure 22.26 .000*

Visitor group × reference destination F1: Quality of facilities and activities 2.73 .066**F2: Cultural and natural attractiveness 0.23 .794F3: Quality of services 2.52 .081**F4: Quality of infrastructure 1.82 .163

*p < .01. **p < .10.

Downloaded By: [TÜBTAK EKUAL] At: 12:43 18 November 2009

Measuring Destination Competitiveness 67

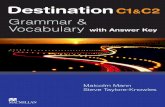

nationalities, Germans also perceived Turkey more competitive when com-paring it to Greece (Figure 1).

Figure 1 indicates that in general Turkey received similar or better com-parative ratings as the mean scores varied between the scale midpoint andmore favorable ratings (1 = much worse, 3 = about the same, 5 = much better),with a range of 3.1 and 3.9. The findings demonstrated that different nation-ality groups perceive Turkey’s competitive position differently. Turkeyneeds to improve quality of service for German and Dutch/Holland tourists.Two items in Quality of Service that deserve specialized attention are “stan-dard of hygiene and sanitation” and “quality of local food and beverage,” astheir mean scores were relatively low. Turkey should also enhance its com-petitiveness against Spain in terms of Quality of Infrastructure. The items in

FIGURE 1 The interaction between visitor groups and reference countries.

Note. The lines show ratings for Turkey for each factor dimension when compared to Spain and Greeceacross British, Dutch/Holland, and German tourists.

F1: Quality of Facilities F2: Cultural and Natural Attractions

F3: Quality of Services F4: Quality of Infrastructure

Downloaded By: [TÜBTAK EKUAL] At: 12:43 18 November 2009

68 M. Kozak et al.

this dimension were mostly nontourism services such as banking, health,and telecommunication. It should be noted that this finding was consistentwith the indices published by the WTTC.

The findings also suggested that a small gap exits in competitiveness ofTurkey, Spain, and Greece against each other. This result was not much sur-prising given the fact that these destinations offer similar cultural and naturalattractions and are typical sea, sun, and sand destinations. However, qualityof services delivered appears to be a major factor in determining competi-tiveness of these destinations. This finding corresponds with the propositionof Campos-Soria et al. (2005). Therefore, strategic plans can focus onincreasing the quality of service and perceived value as well as enhancingthe destination experience by augmenting the tourism product and servicesin order to distinguish one destination from its major rivals.

CONCLUSION AND IMPLICATIONS

This study has been designed to measure the direct competitive position ofone destination compared to other similar competing destinations. Theresearch findings complement the Competitiveness Monitor of WTTC whichis based on secondary data and statistics of various United Nations organiza-tions. Comparatively speaking, one may argue that the present study pro-vides some evidence to test the validity of the research findings. Based onactual survey data this study, although be limited, clarifies competitivenessmeasurement. In order to compare this study with data in Tourism Compet-itiveness Monitor we obtained the necessary data and came up a compara-tive table of three countries. The results given in Table 6 indicate considerableagreement between the present study and the WTTC comparative analysis.First of all, Turkey is much better in terms of price competitiveness, simi-larly ranks quite high in openness and human tourism. However, in case of

TABLE 6 Competitive Position of Turkey vis-a-vis Spain and Greece Using WTTCCompetitiveness Monitor

Turkey Spain Greece

Index value Ranking Index value Ranking Index value Ranking

Price competitiveness 70 28 29 95 29 93Human tourism 51 37 51 36 NA NAInfrastructure 51 67 52 65 47 76Environment 44 110 90 5 57 75Technology 67 75 93 39 94 35Human resources 44 99 92 13 85 25Openness 69 45 59 74 61 69Social 55 75 72 31 70 33

Source: WTTC Competitiveness Monitor.

Downloaded By: [TÜBTAK EKUAL] At: 12:43 18 November 2009

Measuring Destination Competitiveness 69

environment, Turkey ranks 110 out of 212 countries whereas Spain ranks 5and Greece ranks 75 same with Turkey. The only problem is that we do nothave the relative weights of WTTC competitiveness data in order to comeup an overall position of these three countries.

This article has also provided some clearer insights into competitive-ness measurement for tourism destinations which can contribute to effec-tive policy making by local tourism authorities and service providers in theprivate industry. Mediterranean destinations were selected as they are theprimary competitors of Turkey in international tourism, as supported byprevious research (Kozak & Rimmington, 1999; Kozak, 2004). According tothe projections for 2020, Turkey is on the way to be the fourth biggestdestination in the Mediterranean region with a market share of 7.8% and27 million visitors. Consequently, the ability of Turkey to increase itsmarket share, the number of visitors, and thereby tourism revenuesdepends on better assessment of the factors forming competitiveness,developing appropriate policies and strategies for this, and implementingthem into the practice accordingly. Through the feedback obtained fromthe nationally-diverse market segments, findings of this study would behelpful for tourism authorities to evaluate their comparative performancewith their major rivals in the Mediterranean area. The findings are limitedto the competitiveness attributes included in the study and for a futureresearch a qualitative study would help reveal some other components oftourist destination competitiveness.

The results should be interpreted with caution before devising differen-tiated target market and tourism product delivery strategies and tactics,because particular nationality groups visit different geographic regionswhile visiting Turkey. For instance, German tourists prefer the Mediterra-nean coast or Turkish Riviera while British tourists prefer seaside resortsalong the Aegean Sea. Therefore, it is possible that these variations wouldbe due to service culture and type of tourism development (all-inclusive,bed and breakfast, etc.) in those geographic regions. Another limitation ofthe study is that the results may not be generalizable over the tourist nation-alities included in the study. Future research would aim to replicate thestudy by using different samples and extend the study scope by includingmultiple destinations and nationalities.

REFERENCES

Aguas, P., Rita, P., & Costa, J. (2004, May). Market share analysis: Tourist destinationcompetitiveness. Paper Presented at the 33rd EMAC Conference, Murcia, Spain.

Baloglu, S., & McCleary, K. W. (1999). U.S. international pleasure travelers’ image offour Mediterranean destinations: A comparison of visitors and non-visitors.Journal of Travel Research, 38, 144–152.

Downloaded By: [TÜBTAK EKUAL] At: 12:43 18 November 2009

70 M. Kozak et al.

Buhalis, D. (2000). Marketing the competitive destination of the future. TourismManagement, 21, 97–116.

Campos-Soria, J., Garcia, L., & Garcia, M. (2005). Service quality and competitive-ness in the hospitality sector. Tourism Economics, 11(1), 85–102.

Chon, K., & Mayer K. J. (1995). Destination competitiveness models in tourism andtheir application to Las Vegas. Journal of Tourism Systems and Quality Man-agement, 1, 227–246.

d’Hauteserre, A. M.. (2000). Lessons in managed destination competitiveness: Thecase of Foxwoods Casino Resort. Tourism Management, 21, 23–32.

Driscoll, A., Lawson, R., & Niven, B. (1994). Measuring tourists’ destination percep-tions. Annals of Tourism Research, 21, 499–511.

Dwyer, L., Forsyth, P., & Rao, P. (2002). Destination price competitiveness:Exchange rate changes versus domestic inflation. Journal of Travel Research,40, 328–336.

Enrigth, M. J., & Newton, J. (2004). Tourism destination competitiveness: A quanti-tative approach. Tourism Management, 25, 777–788.

Gursoy, D., & Kendall K. W. (2004, November). A competitive positioning of Medi-terranean destinations. Proceedings of EuroChrie Congress, Ankara, Turkey.

Haahti, A. J., & Yavas, U. (1983). Tourists’ perceptions of finland and selected europeancountries as travel destinations. European Journal of Marketing, 17(2), 34–42.

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate dataanalysis (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Heath, E., & Wall G. (1992). Marketing tourism destinations: A strategic planningapproach. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: John Wiley.

Hsu, C. H. C., Wolfe, K. C., & Kang, S. K. (2004). Image assessment for a destina-tion with limited comparative advantages. Tourism Management, 25, 121–126.

Kozak, M., & Rimmington, M. (1999). Measuring tourist destination competitiveness:Conceptual considerations and empirical findings. International Journal ofHospitality Management, 18, 273–283.

Kozak, M. (2001). Repeaters’ behavior at two distinct destinations. Annals of TourismResearch, 28, 785–808.

Kozak, M. (2004). Measuring comparative performance of vacation destinations. InG. I. Crouch (Ed.), Consumer psychology of tourism, hospitality and leisure(pp. 285–302). Wallingford, UK: CABI.

Lundberg, E. D., Stavenga, M. H., & Krishnamoorthy, M. (1995). Tourism economics.New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Man, T. W. Y., Lau T., & Chan K. F. (2002). The competitiveness of small andmedium enterprises a conceptualization with focus on entrepreneurial compe-tencies. Journal of Business Venturing, 17, 123–142.

Mangion, M. L., Durbarry, R., & Sinclair, M. T. (2005). Tourism competitiveness:Price and quality. Tourism Economics, 11(1), 45–68.

Mansfeld, A., & Romaniuk, J. (2002, May). How do destinations compete? An appli-cation of the duplication of purchase law. Paper presented at the 32nd EMACConference, Glasgow.

Mill, R. C., & Morrison A. M. (1992). The tourism system: An introductory text(2nd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Nunnaly, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Downloaded By: [TÜBTAK EKUAL] At: 12:43 18 November 2009

Measuring Destination Competitiveness 71

Papatheodorou, A. (2002). Exploring competitiveness in Mediterranean resorts.Tourism Economics, 8, 133–150.

Ritchie J. R. B., & Crouch, G. I. (2003). The competitive destination. Wallingford,UK: CABI.

Syriopoulos, T. C., & Sinclair, M. T. (1993). An econometric study of tourismdemand: The AIDS model of US and European tourism in Mediterranean coun-tries. Applied Economics, 25, 1541–1552.

Yoon, Y. (2002). Development of a structural model for tourism destination com-petitiveness from stakeholders’ perspectives. Unpublished dissertation, TheVirginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Virginia.

Vanhove, N. (2006). A comparative analysis of competition models for tourismdestinations. In M. Kozak & L. Andreu (Eds.), Progress in tourism marketing(pp. 101–114). London: Elsevier.

World Tourism Organization. (2004). Tourism highlights. Madrid, Spain: Author.

Downloaded By: [TÜBTAK EKUAL] At: 12:43 18 November 2009