Major H.C. Mitchell, MBE - SCAA Projects

-

Upload

khangminh22 -

Category

Documents

-

view

0 -

download

0

Transcript of Major H.C. Mitchell, MBE - SCAA Projects

Foreword

This copy of Wartime Memoirs of Major Howard Mitchell, MBE is a reproduction ofthe original that was written and published by Major Mitchell some years ago. MajorMitchell served in the SLI (MG) a wartime unit which has been superseded by theNorth Saskatchewan Regiment.

Major Mitchell was highly decorated for his wartime exploits. The following is an out-line of his service provided from the National Archives of Canada:

Name: Howard Clifton MITCHELLRank on enlistment: 2nd Lieutenant

Rank on discharge:Major

Date of Enlistment: 6 October 1939 (previous service with Canadian Officer TrainingCorps Saskatchewan Unit)

Date of Discharge/Transfer: 18 December 1945 (he joined the reserves)Theaters of service: Canada, United Kingdom and Central Mediterranean Area

Medals:Member of the Order of the British Empire (The Canada Gazette 15 December 1945page 5734 continued)

Military Cross Class III (Conferred by the Government of Greece in recognition of dis-tinguished service in the cause of the Allies.) (The Canada Gazette 17 January 1948page 345)

1939-45 Star, Italy Star, Defense Medal, Canadian Volunteer Service Medal and Clasp

In addition to the original text I have added information about three individualsnamed in the book, the pictures and the citation for Major Mitchell’s MBE and MilitaryCross 3rd Class (Greece)

Reproduced by:LCol. Gerry Carline, CD, RCA (Retired)

September 2008

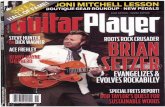

The medals pictured above were issued to MajorHoward Mitchell, MBE for his service duringWorld War II. The medals were found aban-doned in a storage container and came into thepossession of LCol. G. F. Carline, CD in July 2008.

When found the medals were not mounted aspictured. They were loose and not in good condi-tion. The box that they were in contained a notewritten by Major Mitchell which said that theMBE had been presented to him by King GeorgeVI and that the Greek Military Medal Third Classhad been presented to him by the King George II,King of the Hellenes (Greek King).

The box also contained three Royal Canadian Le-gion Medals - Past President, 50 Year ServiceMedal. and 60 Year Service Medal.

The Legion medals had Major Mitchell’s name in-

scribed on the back of them and that made it pos-sible to identify the original owner of the medals.The medals have now been properly cleaned, an-odized and court mounted.

Through the assistance of Dr. Ian Wilson,Archivist for Canada and his staff at the Archivesand Library of Canada and also LCol. LarryWong,CD (Retired) former CO of the NorthSaskatchewan Regiment we have been able touncover the story of Major Howard Mitchell,MBE.

Major Mitchell’s own account of his wartime ex-periences follows.

We Shall remember Them!

The Wartime Exploit of Major H.C. Mitchell 4

The Medals of Major Howard C. Mitchell, MCL to R: Member of the British Empire, 1939-1945 Star, Italy star, France and Germany Star,Defence Medal, Canadian Volunteer Service Medal, Greek Military Medal Third Class

Chapter 1 I Enlist Page 9Chapter 2 The Stadium, Saskatoon Page 11Chapter 3 We Leave Canada Page 14Chapter 4 England Page 17Chapter 5 Aldershot Page 19Chapter 6 Bulford Camp Page 28Chapter 7 We Start On Our Way To War Page 31Chapter 8 The Defence Of Britain Page 34Chapter9 Change of Command Page 37Chapter 10 “C” Company Page 40Chapter 11 Scotland Page 46Chapter 12 Schemes Page 48Chapter 13 Brighton Page 49Chapter 14 Coulsdon Page 52Chapter 15 We Get Our “Colours” Page 59Chapter 16 Change of Command Page 60Chapter 17 Hove Page 63Chapter 18 Steyning Page 67Chapter 19 Crookham Crossroads Page 70Chapter 20 Frant Page 76Chapter 21 Toward Castle Page 77Chapter 22 Liphook Page 79Chapter 23 Bishop Stortford Page 80Chapter 24 Heavy Motars Page 81Chapter 25 The Assault on Sicily Page 84Chapter 26 The Assault on Italy Page 90Chapter 27 Food Page 93Chapter 28 People Page 95Chapter 29 Rest at Oratino Page 96Chapter 30 Naples Page 98Chapter 31 The Moro River Page 100Chapter 32 Ortona Page 103Chapter 33 Counter Mortars Page 105Chapter 34 Roatti Page 108Chapter 35 Lucera Page 109Chapter 36 The Hitler Line Page 111Chapter 37 Piedmonte Page 113Chapter 38 Florence Page 116Chapter 39 The Gothic Line Page 118Chapter 40 Rimini Page 119Chapter 41 Another River to Cross Page 122Chapter 42 The Savio River Page 125Chapter 43 Riccione Page 127Chapter 44 We Get New Generals Page 129Chapter 45 Rotational Leave Page 133Chapter 46 Overseas Again Page 137Chapter 47 de But Page 139Chapter 48 Leave Page 144Chapter 49 England Again Page 146Appendix 1 Citations Page 149

Table of Contents

MYWAR

Major Howard Mitchell

Saskatoon Light Infantry (MG)PREFACE

Modern wars involve everyone in one way or another. The memoirs of a general have a very wideappeal. Many were affected by the decisions of a general.

A general can win a battle or war because of the disciplined effort of many people. Individually thosemany may not seem to have done much. But because of what each did the event was possible. “Whenthe roll was called out yonder” they were there. That was their important contribution.

Ex-service men form one of the greatest “natural fraternities.” We shared the boredom, the monotonyand the loneliness as well as the excitement, the thrills and the laurels. We never tire of recountingwhen... These pages have been written in that spirit. I want to share some of the more unusual experi-ences that I had. It is sort of “worm’s eyeview” of the Second World War where the worm takes forgranted that everyone knows about the daily routine and accomplishments of the Army. This is animportant point to remember. Otherwise reading the following pages may lead one to believe thatwine, women and song were our sole occupation and not just our favorite diversion.

This story is dedicated to the memory of those men and women who, in 1939, laid their lives on theline for a Depression-ridden Canada.

ORGANIZATION

Aword about the organization of the army. ManyCanadians, not having personal experience, findthis to be very confusing. An army, in the field,must be able to carry on under any circumstancesencountered without having to depend on localresources. Somewhere, in the army organization,there will be a unit to supply every individualneed. Following is a very rough explanation ofthe organization.

In WW II the Canadian Army was patternedclosely after the British Army.To begin with thereis the base organization which recruits and trainsthe soldiers; specifies, procures and supplies allmaterial; and sends up reinforcements.

The army in the field is an independent organiza-tion commanded by a general. It consists of twoor more corps, each commanded by a Lieutenant.General, and a host of specialized units. Eachcorps consists of two or more divisions, eachcommanded by a Maj. General, and more special-ized units.

In normal circumstances the division is the small-est formation used in the field. For special pur-poses a brigade may be used. For instance, theCanadian contribution to NATO forces was abrigade. But when that brigade was cut in half itbecame a joke.There are armoured divisions and infantry divi-sions. They are similar in organization but differ-ent. My experiences were with the infantry.

An infantry division consisted of nine infantrybattalions. These were organized into threebrigades, each commanded by a brigadier. Alsounder the command of the division was a Regi-ment of 25 pdr. artillery; a regiment of anti tankguns; a reconnaissance regiment; a machine gunbattalion; a medical unit; an army service Corpsunit; and ordinance corps unit; and engineer

unit..

Each battalion and regiment consisted of 800-900all ranks and was commanded by a Lieutenant.Colonel.

Each battalion or regiment was organized intofour combat companies, batteries or squadrons,and a headquarters company or squadron, eachcommanded by a captain or major. Each com-pany or squadron was organized into three pla-toons or troops, each commanded by alieutenant. Headquarter Coy or sqdn looked aftersupplies, etc.

Our battalion, the Saskatoon Light Infantry (MG)was mobilized and served until Jan. 1, 1943 as amachine gun battalion. We had 48 Vickers Ma-chine guns. They were dubbed the “peanut ar-tillery.” These were water cooled guns that couldfire continuously. They were on a fixed mountwhich meant they could be used against unseentargets by using maps for calculations. We hadtwo types of ammunition: ordinary MKVII .303ammunition that the riflemen used. It had a max-imum range of 2500 yards. Our MKVIII ammuni-tion had a range of 4500 yards.

In Jan. 1943 our battalion was reorganized tomeet the expected needs. We were given 20 mm.Oerlikon anti aircraft guns and 4.2 inch mortarsas well as our Vickers machine guns.

We were called a support battalion. There wasbattalion headquarters which, in action, tookcommand of the Divisional Maintenance Areaand practically suspended connection with thebattalion with the exception of HeadquartersCompany. The rest of the battalion was organizedinto three Groups. Each group consisted of aheadquarters, one company of Vickers machineguns, one company of 20 mm. Oerlikon anti air-craft guns and one battery of 4.2 inch mortars.The 4.2 inch mortars fired a bomb that weighted

The Wartime Exploit of Major H.C. Mitchell 7

19 pounds. Its’ maximum range was 4800yards. We had high explosive and smoke bombs.It was originally designed for chemical warfare.Somewhere, no doubt, there was a store of chemi-cal bombs. We never saw any. Within our rangewe could match the 25 pdr artillery for speed andaccuracy - with one exception. Each bomb had atail unit which stabilized its’ direction. If the tailunit came off no one knew where it would go.

Because of allied air superiority it was found thatthe Oerlikon anti aircraft guns were not needed.So our battalion was re-organized again. TheGroups were disbanded. We were organized intothree machine gun companies and one mortargroup of three batteries. Each machine gun com-pany and mortar battery was assigned to abrigade with which it usually served. On manyoccasions they were all used together.

The Wartime Exploit of Major H.C. Mitchell 8

Chapter 1: Enlist

It might be said that my military career beganone sunny day late in May 1924 when our schoolprincipal told us boys to be back at school at 1p.m. We were issued with rifles and we reportedto the school janitor out on the football field. Wewere Cadets. At five p.m. that same afternoon wewere inspected by a lieutenant, from MilitaryDistrict HQ in Regina. In the interval the janitorhad taught us the rudiments of foot drill and rifledrill. He was so effective that, after inspecting us,the young officer congratulated us in a speechthat I have heard many times since, in fact, I havemade it myself, on occasion.

That autumn, when my chum and I were en-rolling at the University of Saskatchewan., wediscovered that those students who took theCOTC course were not obliged to take PT. In ad-dition, two years COTC counted as a class. Thefinal clinching argument - one got paid fifteendollars for each year’s parades.

We were known as Pottsey’s Army and came infor a lot of derision on the campus in those daysof pacifism. In the same way that a child cannotpoint to any achievements in a particular period,I cannot say now just how much that we learnedabout the Army in COTC. But it was our intro-duction to army life. Arthur Potts, and others likehim, deserve the gratitude of the nation. In spiteof ridicule and indifference they created theskeleton around which Canada was able to buildher effort in 1939 - 1945.

On that fateful day in September 1939 I was com-bining wheat. The agent for some of the land thatI was farming came to see me on business. Hehad a radio in his automobile. Almost withinminutes of the outbreak of hostility I knew of it.It was inevitable that Canada would enter thewar. In spite of the silly proposal of my politicalleaders, that Canada should make her contribu-

tion that of material, I thought it certain thatCanada would send another Expeditionary Forceoverseas. I was single and so almost certain to beconscripted when that phase began. Besides anyaltruistic motives that I may have had, it wasclearly to my advantage to volunteer right away,and take advantage of what training I had whentrained people were almost non-existent. On al-most the first day of war I resolved to enlist. Ipressed on with the harvest and, when the wheatwas all threshed, I drove into Saskatoon in mynew second hand truck to offer my services.

The first thing that I did in Saskatoon was to buya new hat. I had a very good suit of clothes, etc.but my headgear was disreputable. I wanted tomake a good impression. Then I drove out to theUniversity where I contacted Prof. Arthur Potts,also Brigadier Potts in the NPAM. How should Igo about enlisting? Prof. Potts remembered medimly. I am sure he did not remember much thatwas favourable, as I was not one of his starcadets. However, he was very enthusiastic aboutthe need for a person from a mechanized farm inthe newly mechanized army that Canada wasgoing to create. He advised me to contact the COof the Saskatoon Light Infantry.

Next morning, armed with my COTC certificateA, I presented myself to the CO of the SLI. Hewas very courteous but he had his complementof officers He arranged for me to see the CO ofthe 21st Bty The Artillery did not need an officereither Feeling extremely low, I reported my lackof success to Prof Potts He did some telephoningand I went back to the CO of the SLI This tunemy reception was more favourable I was sentover to the depot for my medical and documen-tation After everything had been satisfactorilycompleted, I was duly accepted as an officer ofthe SLI. I was given two weeks leave to wind upmy affairs I had passed a milestone It was 6 Octo-ber ‘39.

The Wartime Exploit of Major H.C. Mitchell 9

This beginning of my association with ArthurPotts with something that no one in the Bn, be-sides he and I, understood. It was commonknowledge amongst the officers that Col. Clelandhad at first rejected me and then, at Potts’ insis-tence, accepted me. The Adj.-Capt. Allan Embury,who, as an RMC graduate, was the one profes-sionally trained officer in the Bn, was quite con-vinced that I had political influence. Eight yearslater, in an hotel room in Kindersley,Saskatchewan., he was flabbergasted when I toldhim that I had always been a C.C.F.’er of Depres-sion days vintage.

It is hard to remember the situation of those days.I think that Potts was almost certain from the out-break of hostilities, that he would take the SLIoverseas, I am quite convinced that Potts wasseized with the challenge of organizing a mecha-nized battalion. He knew that there would bemany problems and he had no idea what theywould be. A common boast of his during thatfirst year was that most of his men had driventrucks and tractors on the farm and would beeasy to organize into a mechanized Bn. I think heeventually had to eat those words. Certainly Ichanged my opinion on that point. A boy, whohad learned to drive his father’s truck, was oftenthe most difficult to convince that there might bea reason for the way the army wanted him todrive.

I feel quite sure that Potts thought that I, a farmerwho owned and operated his own modern ma-chinery, was an excellent potential officer. Mymilitary background might be sketchy but I hadconsiderable practical experience.

Looking back I like to think that I justified Pott’sjudgment of that time. Certainly during that firstyear, it seemed to me, a pattern was set thatlasted throughout the six years that I was withthe Bn. Whenever anything unusual came up, forwhich no one was properly trained, “Mitch” was

given the job. He had no military background tosully if he failed and he usually figured outsomething.

The Wartime Exploit of Major H.C. Mitchell 10

Chapter 2: The Stadium, Saskatoon

At the end of my leave I reported to the Battalionat the Stadium in Saskatoon. Everything andeverybody was in a turmoil. Recruiting was con-tinuing. Quite a high percentage of the applicantswere unsuitable. The provisions for training con-sisted almost entirely of one PPCLI Sgt. plus theNPAM Battalion. There was no equipment, nouniforms.

Everyone in the Battalion was a completestranger to me. I knew how little I knew aboutthe army. I did not know how little the othersknew. It was a time of feeling my way around. Inthe process I found that a smart figure in a smartuniform was sometimes misleading. Most of theother officers had connections in the city andvery few lived in the lines. Consequently it tooklonger to become acquainted. However we hadour moments. One night that I remember was aping pong game in the mess anteroom. Eachplayer’s drink was on the table. The player, intowhose glass the ball was put, stood the round ofdrinks. The game was quite lengthy and hilari-ous.

The first time that I found myself coming to beaccepted by the other officers was following amess dance in the Barry Hotel. A friend fromhome, with whom I had often danced in the OldSchool House during the Depression days, was inthe city and was my partner that evening. Wethought the music was good and we really “cutthe rug.” My fellow officers were impressed. Ofsuch are armies built.

I had been reared to loathe John Barleycorn. Ifound that was the first obstacle I had to cross inthe mess. My patriotic fervour was such that Iwas willing to risk even that. To my surprise I didnot go straight to hell. I did considerable experi-menting but at least a year was to elapse before Ibegan to really understand the good influence

that alcohol can be.

One night a fire broke out in one of the Exhibitionbuildings. Maurice Dupuis was the duty officerthat night. The person who discovered the firehad turned in the alarm to the city fire depart-ment. I think that our Battalion had a few pails ofsand and water but little else of its own. How-ever Maurice, who had had a couple drinks,thought that the duty officer should do some-thing but did not know what. The Orderly Sgt.had rounded up the fire piquet. Maurice hadthem fallen in and then he proceeded to havethem number over and over again. Fortunately asenior officer came along and spared the piquetthe task of fighting a fire by numbering.One of the Battalion’s headaches at that time wasone of our Indian recruits. Throughout my sixyears with the Battalion on active service, I wasvery proud of our Indian boys. But Big Bearcould not stand fire water. And Big Bear wasstrong. Whenever Big Bear was allowed out ofthe barracks, he got drunk. And when he gotdrunk, he got into a fight and literally smashedup the house wherever he was. It was alwaysnecessary for the Orderly Sgt. to take his full pi-quet with him to retrieve Big Bear, and, on oneoccasion at least, he smashed the detention cell inthe stadium and got out.

Early in November, Maj. D. Walker conducted aschool for the Non Commissioned Officers andjunior officers of the Battalion. There were aboutninety of us. In three weeks we covered the rudi-ments of army life as for a machine gunner. Ihave always regarded that course as being theinitial base upon which the record of our Battal-ion was built. It wasn’t that we learned so much.It was the attitude to our job that we learned thatwas so important. We were the Non Commis-sioned Officers and officers from all Companies,of the Battalion. That course was the first unify-ing influence in our Battalion and it set the stan-dard for our future training. Few men had a

The Wartime Exploit of Major H.C. Mitchell 11

greater influence on the SLI in 1939-45 than Dray-ton Walker.

I was attached to ACompany commanded byMaj. E.J. Scott-Dudley. That was the beginning ofa very unhappy association. He knew of how Icame to the Battalion and, like everyone else,misunderstood the situation. He was a bankerwho despised his own farm background. On mypart even his hyphenated name was repulsive.Characteristically the first good impression that Imade on him was when I helped to fill out thepay books for a batch of new recruits. I printed,by hand, their name, etc., as any grade two childcould have done. He thought that I did ratherwell at that.

One day in October, Brigadier Pearkes arrived toinspect our Battalion. It occurred to me that hewas very annoyed at what he saw. The Battalionwas terribly equipped. It wasn’t a case of gettinga uniform to fit - the thing was to get a uniform.Some were in civies. Some had ill fitting battledress blouses and trousers. No belts, no anklets.Wedge caps that we didn’t know how to wear.The officers only had field service dress uni-forms, Sam Brownes, kid gloves, et al. Pearkessoon got us off the parade ground and asked tosee some training. I do not recall what happenedto the men but he got the Second in command ofthe Battalion to give six of us junior officers somegun drill and fire orders with our D.P. Vickersguns. Major Thomson, the Second in commandwas a 1914-18 infantry veteran who, since mobi-lization, had been worried sick about cooks, la-trine buckets and quarters. He may have seen aVickers gun before hand, I do not know. I knowthat I had only seen one a couple of times. Someof the other junior officers were more proficient.Nevertheless weird things happened in that pe-riod of training. I was one of the officers whomBrigadier Pearkes ordered to be eliminated.

The inspection party left and we got on with our

job. That was my first real lesson that the armytaught me. That debacle, far from being disas-trous, welded us together. We had shared a cru-cial experience. I do not know what strings werepulled but no one was dropped because of it. Wehad become brothers in arms.

Late in November we were inspected by MajorGen. A.G.L. McNaughton, Inspector General ofthe Canadian Army. This time we were betterprepared. We had a few uniforms and we hadlearned how to get on and off the parade ground.Things went reasonably well. That evening, inthe mess, Professor Potts introduced Fred Daweand me to General McNaughton. I was verygreatly impressed. One of the General’s firstquestions was as to whether we had finished oureducation. It was going to be a long war and hethought that our first duty was to become as pro-ficient as we could in our own vocation.

Shortly after that inspection Brigadier Potts re-verted to Lt. Col. and took command of our Bat-talion. Often since, I have thought that he was theonly man who could have taken us overseas andmade a going concern out of us. I still doubt thathe knows which end of a machine gun the bulletscome out. But he knew men and he knew the par-ticular collection of men who made up the SLI atthat time. A veteran of 1914-18 and a long timeNon Permanent Active Militia officer he knewwhat we had to become to be effective and heknew what we lacked. His particular forte wasbeing able to choose men to do a job and thenleaving them to do it. I always felt that I knew ex-actly where I stood with Pottsey.

His impression on me, when he came on his firstparade, was of an aging man in a sloppy uni-form, being slightly ludicrous. But every man inthe Battalion knew that times had changed.never got to know Lt. Col. Cleland. Those whohad served under him in the Non Permanent Ac-tive Militia Battalion always spoke highly of him.

The Wartime Exploit of Major H.C. Mitchell 12

Later he took the salute at a march past as wemarched downtown to board our train for over-seas. That day he was very unhappy.

Plans for the Battalion to proceed overseas beganto take shape. First came a series of inoculations.They were multiple things given to protect usfrom several dangers. We had three goes at it.Some men had a greater reaction than others. Istill do not know whose responsibility it was forwhat happened but some terrible things occurredas a consequence. Our permanent force Drill Sgt.had an idea that the best treatment for a newlyinoculated person was a brisk bit of rifle andsquad drill. The unnecessary agony that that foolcaused. Our final shots came a few days beforewe entrained. One of the men, in what was nomi-nally my platoon, got so ill that he had to betaken off the parade ground. ANon Commis-sioned Officer told me about it and I rushed overto the Regimental Aid Post where I asked theMedical Officer to come and look at my man. Heinsisted that the sick soldier should be paraded tohis office. We compromised with a stretcher.When the poor fellow got to the Regimental AidPost, he was dead.

We did not have enough recruits to fill our com-plement. A group of ninety officers, Non Com-missioned Officers and men were transferred tous from the Regina Rifles. The formal organiza-tion of the Battalion into complete companies,plus a re-enforcement company was undertaken.That called for considerable paper work andcould not be finally completed until just beforewe got onto the train as we were to take an exactnumber of bodies. In a battalion, there is always adaily wastage.

Lt. Bradbrooke and I were the two re-enforce-ment officers. He went with the advance party. Itwas my job, the afternoon before we left Saska-toon, to sit in the Adjutant’s office with my nomi-nal rolls as each company commander went over

his nominal roll with the Adjutant. All five Com-pany Commanders came in, one at a time, ha-rassed but in quite good humour. Each in turn,after his session with the Adjutant, left fightingmad. I have never met anyone who had the abil-ity to antagonize people that Allan Embury hadon that occasion.

His position can hardly be imagined. As adjutantand also as the one professionally trained officerin the Battalion he had been responsible for all ofthe paper work connected with the mobilizationof the Battalion. During practically all of that pe-riod Lt. Col. Cleland was in command. I am surethat Cleland knew as well as Potts of the likeli-hood of Potts taking command of the Battalion.Losing the command was a terrible heartbreakfor Cleland. It was almost inevitable that hewould be indecisive under such circumstances.Indecision by the Commanding Officer madeEmbury’s job impossible.

The Wartime Exploit of Major H.C. Mitchell 13

Chapter 3: We Leave Canada

December 5, 1939 we left Saskatoon in two trains.Lt. Col. Potts went with the first train and Maj.Charles McKerron, Officer Commanding ofHeadquarters Company, commanded the secondtrain which traveled two hours later than thefirst. They were standard tourist coachesequipped with double windows for the winterweather. The windows could not be opened. Theofficials were afraid that we, untrained troops,could not be relied on and orders were given thatwe were to entrain and not get off. Farewellswere to be said through the windows. The boystook one look at the glass that separated themfrom their loved ones. As though there was anexplosion, every window on the platform side ofthe train burst out. By the time the second trainwas made ready, the windows had been loosenedso that they could be opened.

There were two aftermaths to this window break-ing. The first was that the boys in the coaches af-fected had to improvise window coverings tokeep out the elements. The second, was that for ayear or more the authorities tried to get Potts topay for the windows out of regimental funds,which he cheerfully refused to do.

My military education continued on the secondtrain. Maj. McKerron was a First War veteran. Helaid on a daily routine for the train - includingthe Commanding Officer’s inspection. Each of usofficers was in command of a coach. I couldhardly believe that these boys were the samewestern farm lads, who had enlisted in Saska-toon. I laid on that the coach, that I commanded,was to be cleaned. Entirely on their own the boysused their own brasso to polish the bright metalparts in the car and their own shoe polish toshine the black pieces of metal. I am sure that theconductor of that train had never before seensuch a clean train. The coaches could not havelooked better when new.

Enroute, one man, in my coach, developed scarletfever. He was taken off the train and everythingproceeded as usual except that whole train wasconfined, each to their own coach. When we gotto Halifax, we were marched off the train ontothe pier one coach at a time. With everyone carry-ing all his luggage it was a very cumbersome ef-fort.

A guide lead me and my coach load into a largeroom in what I later learned was the ImmigrationBuilding. As soon as we were all in the room theguide locked a metal door which very effectivelyimprisoned us. Until that moment, I had not sus-pected a thing. No one wanted to run the risk ofhaving a shipload of men contaminated withscarlet fever. We were in quarantine for twoweeks.

From this distance in time, it is difficult to realizeour thoughts. I had very little knowledge of themilitary and knew absolutely nothing about aship. Had I known then, what I know now, aboutthe loading schedules, etc. of a ship, I would havebeen in even greater despair. As it was I honestlythought it to be quite possible for the war to fin-ish before we rejoined the Battalion. Those werethe days of the phony war and everyone had asublime faith in the French Maginot line.

The Officer Commanding of the transit depot inHalifax was Major Small, who worked forDOSCO in civilian life. He was the smallest manthat I encountered in uniform anywhere. And hewas the most perfect gentleman that I met any-where. I understand that later he took a Battalionoverseas of mostly Cape Breton miners. Later Lt.Col. Small was transferred to anotherUnit and a stranger was given command of Bat-talion. I was told that the loyal miner soldiersstaged a sit down strike to protest losing Lt. Col.Small as the Commanding Officer.

Major Small made us very comfortable. We were

The Wartime Exploit of Major H.C. Mitchell 14

not allowed freedom but we were able to takeroute marches about the city and given equip-ment to do a bit of training. All of which helpedto pass the time. His greatest contribution wasthat he got us included in the second troop con-voy. Knowing now how carefully each ship isloaded, I do not understand how he did it. But hewas well enough acquainted that he did get usaboard the Ship ALAMANZORAwith the RoyalCanadian Regiment who were commanded byLt. Col, Hodson and whose Adjutant was Capt.Dan Spry.

The Alamanzora was a passenger ship equippedfor travel in a warm climate. In December it wascold. We landlubbers were not accustomed to theclose quarters one takes up on a ship. We werenot always happy. The ship’s wine cellar had itspeace time stock. We officers had quite an adven-ture sampling the various kinds of beveragewhich we were able to order. The meals weregood enough. Some men were horribly sick.Much to my surprise, I was not. One morningwhen I went in to breakfast, I thought that wehad caught the stewards unprepared. There wasnothing on the tables. However, before we fin-ished eating we learned why. The sea got veryrough and several times tables and chairs slidacross the room.

We were at sea Christmas Day. The stewardsgave the Christmas menu a big build up. Whenthe Christmas dinner was placed before me I wasready to riot. I am sure that the turkey had beenboiled. It was served with preserved peaches - nocranberries. It was a horrible let down for a farmboy.

There were about a dozen different units and de-tachments on board. One day, Capt. Spry calledan Orders Group of the heads of each. It turnedout that an enemy submarine was known to benear our convoy. We were ordered not to divulgethis information to anyone, but to make sure that

all necessary precautions were taken. My seniorNon Commissioned Officer was Sgt. Booth. Al-most immediately after the Orders Group, Sgt.Booth told me about the submarine. It seems thata junior Non Commissioned Officer in a signalcorps detachment had read the semaphore mes-sage that had transmitted the information to ourship, as it was being sent by the flagship of theconvoy. The net result of the security regulationsenforced was that the only people aboard theship who did not know about the submarinewere the officers.

Another interesting angle on security measures.At that time the German ship Graf Spee wasbeing pursued in South American waters. Dailynewscasts mentioned that the French battleshipDunkerque was taking part in the pursuit. TheDunkerque was the senior ship in our convoythroughout the voyage.

As soon as we came to rest in Liverpool Harboura tender came alongside. Amongst those whocame aboard was a Major Luce of the King’s OwnYorkshire Light Infantry (K.O.Y.L.I,). He hadcome purposely to welcome the fiftySaskatchewan. L. I.’s whom he had noticed to beaboard the ship register. I had heard vaguelyabout our affiliation with the K.O.Y.L.I. and I didhave a faint appreciation of his interest and of hisinvitation to visit the depot in Yorkshire.

We landed at Liverpool. Everyone paraded onthe dock where we were officially greeted by An-thony Eden and Vincent Massey. After thespeeches they walked up and down our ranks. Iguess that they picked on the greenest looking of-ficer and stopped to talk to me. Eden asked meabout the voyage and about myself. I was quiteengrossed in the conversation when Eden said“now they will get your picture back home.” Ilooked away from him and sure enough therewas a complete semi-circle of cameras facing us.Our train was waiting and we got away without

The Wartime Exploit of Major H.C. Mitchell 15

a hitch. About four o’clock in the afternoon thetrain stewards came through and set up tables ineach compartment in preparation for the eveningmeal. It was midnight when they served themeal. I do not recall what the hold up was. I doknow that we were frantic. We had emergency ra-tions with us of bully beef and biscuits. My civil-ian background did not allow me to understandthe sanctity of emergency rations in the army. At10 p.m. I instructed Sgt. Booth to distribute theemergency rations. The next day, when I reportedthis to our Quartermaster, Capt. Archie Gray, Ithought that he would have a fit.

The Wartime Exploit of Major H.C. Mitchell 16

Chapter 4: England

We were met at Farnborough siding by Col. Pottsand Lt. Maurice Dupuis on New Year’s Day.Maurice took me to my quarters. There were veryfew people around the barracks as everyone hadbeen given a one week leave. I was supposed toshare a room with Lt. Vergne Marr. Dupuis verydisgustedly told me that Vergne played darts. Hecouldn’t have me with such a character. I mustmove in with him and Lt. Rob Irvine. Little didMaurice suspect that in six months time thewhole 1st Canadian Division would be playingdarts.

That room that Marr and I shared sticks in mymemory more than purgatory ever will. It turnedout to be a cold winter. I simply could not getwarm in the English climate. We had a coal fire inthe grate and I know now that we burned muchmore than the regulation allowance. In additionwe had two electric radiant heaters.

As soon as the other officers came back I went onmy leave. Of course I went to London. I don’t re-call how I happened to go there but I stayed atthe Strand Palace Hotel. For my very first noonmeal in London I went down to the dining roomin the Strand Palace. The place was alive withpeople. Quite obviously second Lts. were a dimea dozen to the headwaiter. Equally obviously hewas not tying up a whole table with one SecondLt. It took me about ten minutes to size up the sit-uation. Waiting with me was an oldish EnglishSecond Lt. He wore a red armband but thatmeant nothing to me. I spoke to him and sug-gested that, if we went together, we might get atable more quickly. He was a bit hesitant but ac-cepted. Almost immediately we were given atable for two. The Englishman was delighted.

His name was Beattie. It turned out that heworked in the War Office and that his particularline was fire prevention and fire regulations, etc.,

in all army buildings. He invited me to join himwith his wife and niece to see a show the nextevening. Of course I did. That evening was a rev-elation to me. It was a variety show. Such beauti-ful scenery, costumes and music. It wasunbelievable. And so was the humour. I wasnever so embarrassed in all my life.

Beattie caused almost as much consternation asvisiting royalty when, about a month later he,with his red armband, turned up at our barracksin Farnborough enquiring for me. I think he wasa Capt. then. About a year later he was a Lt. Col. -Which was something in the British Army. I losttrack of him after that.

My itinerary in London was typical I went tochurch in St. Paul’s I was thrilled I visited MmeToussaud’s wax works I did not like them at all. Idrove about the city on an outside seat on a twodecker bus. Somehow I picked up a man who, forten shillings, rode about with me, pointing out allthe places of interest.

Probably the most enlightening observation thathe made was about English women. He told methat they did not expect a man to spend a lot ofmoney to entertain them. All that they wantedwas companionship. His name was Piercy. Helived in London After our sightseeing he took meto his home for tea.

Sunday afternoon I went out to Hyde Park to seethe soap box orators. That was really Something.There were five speaking that day. One was awoman and she could out talk them all. I was fas-cinated with her and stood listening when, to myhorror, she stopped her Speech and publicly andpersonally bade me welcome to England andthanked me for coming. I moved on. Anotherspeaker was a communist. There were about fif-teen British Tommies in his audience. He wastelling them what fools they were to be in uni-form. The Tommies were in great spirits and un-

The Wartime Exploit of Major H.C. Mitchell 17

dertook to heckle him, which they did so effec-tively that he couldn’t get on with his speech. Fi-nally the communist turned to the impassive“bobby”, who was on duty and asked for help.The policeman spoke to the Tommies “come nowlads, let the guvnor have his saigh.”

Listening to the next Speaker I found myself inconversation with a petite brunette girl. I do notremember how the conversation started but shewas very pleasant. She was from Persia. Herbrother was with the British army in Egypt. Isuppose we talked for about ten minutes I wasquite charmed. Finally she said, “You know thereis a very nice Lyons tea house just across thestreet where we could have some tea.” That wasthe first thing that she said to arouse my suspi-cions. I looked around and we were completelysurrounded by a circle of people who were ignor-ing the speaker to watch us. I am sure that in an-other minute a “bookie” would have appearedfrom somewhere ready to quote odds on whethershe would pick me up.

One evening towards the end of my leave I wasgetting quite lonely seeing London by myself. Iwent into Scotts for dinner. Again there was await to get a table. This time there was a womanwaiting with me. I guess that I got some encour-agement. At any rate, I asked her to have dinnerwith me. Later we went to a show. it made agood evening for me. After the show we took ataxi to her home. I did not know who was moredumfounded, she or the taxi hotel driver, when Isaid good night to her at her door and took thetaxi back to my In February, I spent a weekend inLondon. Sunday morning I attended a divineservice in St. Paul’s cathedral I was thrilled. Inspite of its’ covering of soot, it was a beautifulbuilding. The organ and choir were wonderful. Iwas not impressed by Westminster Abbey. Ithought that it looked crumby. However the ceil-ing of the Henry 5th chapel was unbelievable.The fretwork in stone looked to me to be impossi-

ble, even in wood.

In the afternoon, I went to Hyde Pan and GreenPark. Besides the speakers there was a model air-craft meet. Boys, with their fathers, had abouttwenty gas motor powered model planes. Theywere the first that I had seen. I was amazed athow the boys maneuvered them.

I closely examined one of the barrage balloons.Each balloon had a six wheel Ford truck onwhich was mounted a Fordson tractor motor towinch the balloon. In London there were hun-dreds of balloons.

The Wartime Exploit of Major H.C. Mitchell 18

Chapter 5: Aldershot

In January when I got back to barracks the othershad had a week to get organized. Training hadbegun in earnest. Training areas were allotted.People were going on courses. The whole ma-chinery went into gear quite well. It seemed thateveryone trained except me. I was the junior re-enforcement officer and whenever anyone wentaway I took his job. It was interesting but my for-mal military training suffered.

We shared the Tournai Barracks with the TorontoScottish Regiment. Again it is hard to realize con-ditions at that time. The Toronto Scottish were aposh peace time militia Battalion. From a largecentre they had a high percentage of people whowere reasonably trained. Their officers weremostly men of means. Their uniforms were beau-tifully tailored. Contrast that with our uncouthmob. There was hardly a single uniform in theSLI that fitted. We came from everywhere in theWest and very few of us knew anything about thearmy. The Toronto Scottish were sorely tried to beso near to us.

Right from the very first, our relations werestrained. Both Battalions had arrived in the bar-racks just before Christmas. As a part of their cel-ebrations the Toronto Scottish got several kegs ofbeer for their men. These were stored in a roomwhere they mounted a proper sentry. A SLI man,by the name of Near, knew about this beer. Some-how he got into the store of beer and carried outone keg, which he got the Toronto Scottish sentryto watch for him while he fetched a wheelbarrow.He actually got away with that keg of beer.

We had been sternly warned, before we leftSaskatoon, that this was to be a no nonsense war.We had a grim job to do and we had to do itwithout frills. So all of our band instruments andmost of our bandsmen had been left in Canada.The Toronto Scottish were much wiser and

brought their complete pipe band. Their day wasordered by the pipes. We came to think that theyplayed the pipe so that they could breathe in uni-son. We got heartily sick of the skin of the pipes.Imagine my disgust in October, 1945 when theBattalion returned to Saskatoon. We were met atthe station by the pipe band of the 2nd Battalionof SLI

Potts knew that we had a lot of training to do andhe laid on long hours. The day began for the offi-cers at 7 a.m., when we paraded for P.T. in thesnow in front of the Officers Mess. For a longtime it was dark at that hour and there was muchmuttering and mumbling. Maurice Dupuis madehis criticism in his own unique way by turningout one morning with a coal oil lantern. ButPottsey was there every morning and P.T. contin-ued at 7 a.m. as long as we were at Tournai.

The training day for the men finished at 4 p.m.when the officers had afternoon tea. This was aparade by which Potts intended to weld us to-gether. Tea was followed by a lecture period forofficers which lasted one hour. After that camethe evening meal and preparations for the nextday’s work.

I had three pet peeves at that time. One was thecold. I didn’t mind winter weather if I could justget warm once in awhile. But I actually felt moreuncomfortable indoors than out. I did not get ac-climatized until our second winter in England.

Two was the habit of the English to break for teaat 10a.m. and 4 p.m. That objection sounds amus-ing now. But in those days Canadians had not ac-quired the coffee break habit. I found it mostdisconcerting to be doing business with someonewho would suddenly disappear for tea. In fact, Ithought it frivolous. However, before long welearned that one could often transact businessbetter over a cup of tea.Three was the Army’s method of training. It

The Wartime Exploit of Major H.C. Mitchell 19

seemed to me to be so absurd to break everymovement down by numbers and to teach theboys as though they were stupid apes. It was mycontention that if they gave each one the pam-phlet and the weapon he would figure it out inthe same way that one had to do when con-fronted with a new implement on the farm. Itwas quite some time before I realized that in thearmy the effort of the individual counted for al-most nothing. The objective in the army was toconcentrate the efforts of literally millions of indi-viduals into one supreme effort.

The civilian had to stop thinking as a civilian andbe trained to think as a fellow ant. I agree withthe authorities that that process takes two yearstime; even with intelligent Canadian boys.

One of the first officers to go away on a coursewas Reg Rankin, the Intelligence Officer. I tookhis place. Under those circumstances the Intelli-gence Officer was really an assistant adjutant andAide de Camp to the Commanding Officer. Therewas a great deal of organizational work to do andI did get a wonderful opportunity to learn aboutthe organization.

Almost immediately on landing in England, Pottshad taken Phil Reynolds, Officer Commanding ofD Company, to be Adjutant and put Embury incommand of D Company. Phil was a quiet opera-tor and it was a pleasure to work under him. Hiswife, Jenny, followed us overseas and took ahouse in Farnborough. We officers spent manyhappy hours in their Farnborough home.

One of the first administrative problems aroseout of the take over of the barracks by the ad-vance party. Lt. R. Rankin had been in charge. Hehad been confronted with masses of documentsby the Aldershot Command people. Amongstthem was one itemizing barrack stores in the offi-cers mess. There was supposed to be a completeline of tableware sufficient to serve an Officer’s

Mess formal dinner. This document that Regsigned transferred all the losses since about thetime of the Crimean War to the SLI. Potts had an-other battle to fight in addition to the window-pane war.

That was an extremely cold winter by Englishstandards. The drains from the bathrooms wereall on the outside of the brick buildings. A routinewas soon established. Each morning the Quarter-master would ascertain the drains that hadfrozen during the night. He would phone the Ad-jutant’s office and either the Adjutant or I wouldphone the Command Engineers to have someonecome and fix the drains. One morning the officeof the Command Engineers asked to speak to ourCommanding Officer. Potts got on the phone andfound that he was speaking to the Commander ofthe Engineers. “Look here old boy, we’ll fix yourdrains this morning but after that you will haveto do it yourself.” Potts exploded. He had re-tained enough of his English accent that it wasnot a case of a “Bloody colonial” speaking to anEnglishman, but was one Englishman speakingto another. “If you people persist in being suchdamn fools as to put the drains on the outsideyou can bloody well bear the consequences.”One day we were assigned firing ranges to dorifle practice. Potts sent me out to reconnoiter theroute and range. I took a motorcycle. It was quitea pleasant day. On the way I found a green gro-cer. I bought some English grown apples. Theywere a bitter disappointment. All wormy andspoiled, only about half were fit to use.

Aldershot is a wonderful training area. In an areaabout fifteen miles square there are training facil-ities literally for an army. There are areas for ma-noeuvres. There are all sorts of firing ranges.Because so much is done in so small an areasafety margins are cut to a minimum. And theywork because, in the British Army, orders areobeyed. The ranges are used almost continuously.Different distances are accommodated in some

The Wartime Exploit of Major H.C. Mitchell 20

cases, by ranges crossing one another. I contactedthe range officer. Our allotted range was Ash No.4. I was shown the road into it. I made notesabout the road and range. I reported to the adju-tant. Nobody said anything to me about theCompany’s Commanders making a reconnais-sance. However, after the Company Com-mander’s meeting, at which my information wasgiven, the Company Commanders decided tohave a look themselves. One afternoon they allgot together on motorcycles and, in a little caval-cade, started out on their own to Ash No. 4 fol-lowing my route card. No one told the rangeofficer about it. It so happened that an Englishmachine gun battalion was doing an indirectshoot with their Vickers. Our Company Com-manders just entered a wooded area as it wasblanketed with a machine gun barrage. The mo-torcycles were soon deserted for what protectionthe bole of a tree could offer.

Except for some minor damage to the motorcy-cles, the party emerged unscathed. But I was notvery popular. I am sure that that episode wouldhave severed my connection with the Battalionwere it not for Potts and McKerron. McKerronwas a 1914-18 Veteran. I believe that that barragerevived memories and that he actually enjoyed it.At any rate I had been on the roll of A Company.Shortly after that I was transferred to B Companycommanded by Maj. Drayton Walker.

One of our great trials, on arriving in England,was getting accustomed to the blackouts. Our in-terpretation of a good blackout quite often didnot meet with the approval of the air raid war-den. Vehicles charging about on a black darknight, with only pin points of lights showingfrom their headlamp, made driving very difficult.Amongst the anti-invasion preparations hugeconcrete roadblocks were constructed throughoutthe country. One night Pte. Rice, a Dispatch Riderof ACompany, was riding his motorcycle. Hecame to two red lights on the road. He drove be-

tween them, headlong into a concrete block. Hebroke both legs. In 1947, I saw him in Vancouver.Before the war he had been a bank inspector. Hisbank hesitated to entrust him with his former re-sponsibilities because of his physical condition.His case is typical of the many such sacrifices thatwere made in this period.

During the first month rations caused a greatdeal of trouble. The scale of issue was tremen-dous in comparison with what we lived on twoyears later. But the cooks were inexperienced andoften food was wasted by being poorly cooled.Some rations were stolen. Whatever the reasonthe men often did not get enough to eat and theycomplained bitterly. However, this was eventu-ally straightened out.

Recreation was slowly organized. Aldershot haslong been an army area. The civilians there hadall their fill of soldiers and certainly were not im-pressed by the Canadians. Although there wereno real incidents, our reaction to Aldershot, afterbeing their four months was that it might not be abad idea to let Hitler have the place.

One habit of the local inhabitants that particu-larly annoyed me was their insistence on payingbus fares. We depended on the public transportfor our recreational trips. Coming back to the bar-racks was nearly always on the last bus of thenight. It would be a double deck bus, with adriver and ticket collector. The blackout wasstrict. The bus, both seats and aisles, would bejammed. The ticket collector would get stuck inthe upper aisle. The civilians would refuse to getoff until they had paid their fare and we wouldbe worrying about the time that we would bechecking into the barracks.

The Theatre Royal in Aldershot staged live pro-ductions. The management soon learned that abit of music and a couple nudes would fill thehouse with Canadians. That lasted for about one

The Wartime Exploit of Major H.C. Mitchell 21

month after which we began to demand some tal-ent. One show of this period featured a snakecharmer. A nude woman had a snake coil itselfabout her. That show disgusted me. MauriceDupuis was entranced by the snake charmer.

Through Potts’ direction we officers joined theAldershot Officer’s Club. They had a cut rate forabout 12 shillings per month. Any time that Iwent there the place was full of Canadians andmuch too crowded. That was really a bit of wind-fall for the Aldershot Club. In 1942 when I waswith the Holding Unit, I did attend one bang upfunction there which I enjoyed. Any other timethat I belonged I considered it to be moneythrown away. In September 1945, when we wereon our way home, I dropped in there one after-noon to see if I would recognize anyone. Therewere a half dozen Limey officers who behavedvery much as though I had the measles. I felt likesmashing up the joint to work out my money.

One day I was in the office alone when Col. Mc-Cusker, the Senior Div. Medical Officer, droppedin with five invitations to a tea that Lady Some-body was holding on Sunday. When Potts cameback he was feeling quite magnanimous and hetold me to distribute them in the Mess. I kept oneand gave the others to Rankin, de Faye, Fullertonand Dawe. We had a bit of trouble finding theright place. It was a large country home. Theroom in which the tea was held was about threetimes the size of the Hall in Fiske. There werecheck rooms for the clothing, etc. It turned outthat the guests included the King and Queen ofSiam, Princess Patricia Ramsey, the Naval At-tache’ to the American Ambassador and so on.Lady Somebody else, who had three eligibledaughters there, invited us to visit her in herLondon house. On the whole we were a bit over-whelmed. Tommy dated the girl from the checkroom. But when we got back to the Mess we laidit on to Pottsey as to what he had missed.The intellectuals in our Battalion were Ben Allen,

Fred Dawe, and Reg Rankin. I think that eachhad his Master’s degree. They had bull sessionsnearly every night. Sometimes I would sit aroundand listen. But usually they were beyond mydepth. One favorite topic was “fixing” the posi-tion of a machine gun on the ground by means ofthe stars.

Our affiliated Regiment in the British Army wasthe King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry(KOYLI). Early in our stay in Tournai Barracksthe Colonel of the KOYLI, General Sir CharlesDeedes, visited our Battalion. He inspected ourranks on parade and spoke briefly to the Battal-ion. Afterwards the officers gathered in the Messwhere they were presented to Sir Charles. Thenthe General took a KOYLI lanyard and placed itabout Potts’ neck and expressed the wish that ourBattalion should adopt the KOYLI dress regula-tions. It was a great honour for our Battalion andfew appreciated the honour as much as Potts did.I have never seen anyone so genuinely moved ormore pleased.

After the proper authorities had given permis-sion, our Battalion adopted the lanyard, buttonsand green color of the King’s Own YorkshireLight Infantry. Quite a minor detail to a civilian.It was really a tremendous influence in the build-ing up and maintenance of morale in our Battal-ion.

Phil Reynolds went on leave for a week and Itook over as Adjutant. One day I just got seatedin the office after noon, when a Major Guy Si-monds came in. I don’t think that I have everseen anyone anywhere in such a livid rage. Heliterally radiated hate and anger. He wanted toknow where Potts was. I told him. When Pottscame back he was to get in touch with Simondsat Div. Headquarters immediately. Simonds wasthe officer at Div. Headquarters in charge oftraining of the three machine gun battalions.The Aldershot Command could train nearly a

The Wartime Exploit of Major H.C. Mitchell 22

whole army at once. But that was only possiblebecause of careful planning and a high rate of uti-lization of the facilities. The rifle ranges were inuse throughout the hours of daylight. Meals hadto be so arranged that firing was continuous. Itseems that, on this day, Simonds had decided tohave a look at how the SLI were doing, “D” Com-pany was at the ranges. He arrived there at noon.

Embury was Officer Commanding D Company.He deliberately set out to ingratiate himself withthe Officers and Non Commissioned Officers ofhis Company. He had quite properly arranged tohave the noon meal brought out for the men. Buthe wasn’t having his officers and Non Commis-sioned Officer’s treated like that. At 12 o’clockthe rifles were stacked. The food was served tothe men. He left the Company in charge of alance Corporal, ball ammunition and all, loadedofficers and Non Commissioned Officers intrucks and went back to barracks to eat like de-cent human beings. Then Simonds arrived at therange.

Potts was a long time at Div. Headquarters thatevening. When he came back he told me to pub-lish PT I orders transferring Embury back as Ad-jutant. There were further long conferences thenext day and the day following I had to rescindthe previous day’s orders. Embury stayed with DCompany but now he really was in the doghouse.

Most of every Saturday morning was taken up bythe Commanding Officer’s inspection of bar-racks. I was always on that with RSM Quinn.Potts had dug up a great silver cup which wasawarded each week for the week to the Companywhich he considered to have the neatest lines.After the range episode, D Company didn’t havea chance. It was nearly a month later when Pottshad chosen ACompany as the winner.On this Saturday morning I was sure that DCompany was the best. When we got into the or-

derly room Potts announced ACompany thewinner. I think what followed was characteristicof Potts’ method of command. Certainly it was ofmy relationship with him. Potts said ACompany.I felt no qualms in speaking up and saying that Ithought he was wrong and that I would choose DCompany. Without a moment’s hesitation heturned to the RSM. What did he think? The RSMthought that D Company was the best. Againwithout hesitation he turned to me and said, “Al-right Mitchell, D Company,” and he actually waspleased about giving D Company the honour. Heheld no grudges.

Shortly after Rankin got back MacDonald, thetransport officer, went on a course for a month.So I became transport officer. Transport at thattime consisted mostly of impressed civilian vehi-cles of all makes. One was never quite sure howlong they would run. And the intricacies of anEnglish made motor were quite a discovery forour boys.

The transport boys were a grand lot. MacDonaldwas not a very regimental type. His section werejust a team of pals. I did not quite fit in but theywere a good lot. One of my first days there, oneof the drivers told of his experience the eveningbefore. He had met this girl once before. She wasreally lovely stuff. So he dated her for theevening and some might say his intentions werenot the best. He went to her home where he metMom and Pop. Just when he was wondering howhe was going to handle the situation, the girl sug-gested that they go for a walk. Fine. Only thingwrong was that he was strange to the countryand she knew it intimately. She kept telling himof all the wonderful sights and they walked andwalked and walked till they had covered tenmiles. This was after a full day’s parade. Whenthe walk had ended all that he could think ofwere his feet.The T. Office was in the same building and rightnext the RQM office. Capt. Archie Gray looked

The Wartime Exploit of Major H.C. Mitchell 23

after me like a father. He corrected the way Iwore my uniform. He corrected my posture. Heinstructed me in the ways of the army. One day Ihad a Non Commissioned Officer to break. Thefellow was unreliable and in my language “justno damn good.” Archie showed me the militarylanguage “Not likely to develop into a goodNCO.”

Archie was a grand fellow. He should never havegone overseas. He was a First War Veteran. Andhe had done yeoman service with the Non Per-manent Active Militia Battalion. He wasn’t physi-cally fit. Some papers must have been altered abit just to give Archie the trip overseas with theBattalion as a reward for his faithful peace timeservice.

One Sunday morning, Archie and I were detailedto take the church parade. Those moments werereally the highlights of his life. This morning hetook over the parade from the RSM. In his thickScots accent “Parade will move to the right in col-umn of route, right.” This was the First War Com-mand. Nothing happened. Archie flushed andgave the order again. At the right moment Iadded the word “turn” and we were away.

One day I was working on some papers in theTransport office and Archie came striding in. Ijumped up and saluted. “Come with me!” andArchie turned and strode out of the office. Archiewas in a terrible mood. I followed him. We wentto the Commanding Officer’s office. Both Pottsand Reynolds were seated at their desks whenArchie and I paraded in. I still hadn’t the foggiestnotion of what was up. Archie was so angry thathis brogue was very bad. Slowly I gathered thathe had checked the barrack stoves in the men’smess hall and discovered that there was one coalburning stove missing. On enquiring he was toldthat I had taken it.Nearly ten days before I had been in the shedthat the Transport boys used as a shop. It was a

plain corrugated iron structure with a concretefloor. There was no heat. It was unbearable foranyone to work in the cold on the vehicles. TheTransport Sgt. told me that he had been talkingabout this to the Sgt. Cook. The Sgt. Cook saidthat there were four coal heaters in the men’smess hail and only three were ever used. Ithought it was a good idea so we went over tosee the Sgt. Cook. “Sure take the stove.” So I toldthe Transport Sgt. to move the stove. Which hedid. They had to cut a hole in the corrugated ironfor the smoke pipe. The smoke pipe was cast ironand in eight foot lengths. They had to cut one ofthem. But they got the stove working and every-body was happy until Archie made his monthlycheck of barrack stores.

Both Potts and Reynolds were amused byArchie’s anger. Their faces were very stern but asthe story unfolded a twinkle came into their eyes.When Archie finished Potts spoke to me.“Mitchell is that right?” “Yes Sir.” “Put the stoveback.” “But sir I can’t. They cut the pipes.” “Putthe stove back, that is all,” and he banged thetable.

Archie and I marched out. I told the TransportSgt. to get a new pipe from the iron monger andput the stove back. It cost me £1, 10s.

Sometime later Archie went to hospital. I visitedwith him in Connaught hospital several times.He was touched to think that I, the junior officerof the Battalion should think of him. EventuallyArchie was sent back to Canada. He was the firstto return. The officer’s wives in Saskatoon hadformed an association to console themselves a bit.Of course Archie had to talk to them as did eachreturning officer. Amongst other things Archietold one officer’s wife what a fine boy her manwas. The other officers were chasing around Eng-land after all sorts of girls but her man only wentout with one girl and she was really lovely.

The Wartime Exploit of Major H.C. Mitchell 24

My biggest headache, at the Transport Office,was motorcycles and especially when officerswere using them. The worst offender was Mau-rice Dupuis. One day I happened to go out to thetraining area and encountered Maurice riding amotorcycle. He had no business to have it. Hewas just tearing around the area with it. When Isaw him he was riding through the trees. In thisspot there was no underbrush and the trees wereabout six feet apart and staggered. Maurice rodethrough them at quite a speed. It was really a featbut one that could only lead to disaster, from mypoint of view. I reported this to Potts and Mau-rice was barred from using motorcycles alto-gether. Part of our barrack stores included Airraid equipment. In this equipment was a bicycle.Maurice got this bicycle out and rode it aroundthe lines for hours on end just for Potts’ sake. Hecould do almost anything with it. What I thoughtwas the best exhibition was when he rode the bi-cycle sitting backwards, on the handlebars, andhe crossed a three inch hose lying on the pave-ment without touching the hose.

Maurice was a very clever person. He was also aslave to alcohol. It was a great pity. He could besuch a fine fellow. One evening at JennyReynold’s house he was the life of the party witha two string toy instrument that belonged to thelittle girl next door.

One night, after a bout of drinking, Maurice de-cided to take a bath at about midnight. The bath-room on his floor was just across the hall fromPotts’ room. Maurice got into the bathroom anddecided that he did not want to be disturbed, sohe locked the door. I don’t suppose that the lockhad ever before been used. At any rate it stuckand at 2 a.m., when Maurice had finished soak-ing in the tub, he couldn’t get the door open. Sohe yelled and roused Potts. They couldn’t get thedoor open, so Potts took the fire axe out of itsglass case and chopped the door open. Maurice’smodesty caused more amusement than anything

else about the episode.

Not long after this we were in the midst of a se-ries of after tea lectures on machine gunning.Maurice got horribly drunk that afternoon. In themidst of the lecture he got sick. Without a wordto anyone he jumped out of the window. He wenton to his room and never said anything to any-one. Potts was present at the time. That was theend of Maurice. He had literally jumped out ofthe Battalion.

Quite characteristically of the army, just afterMacdonald, the Transport Officer, went off on hislong course to learn how the Army wanted driv-ers to drive, I, the acting Transport Officer, wascalled on to organize training for the drivers. Ouronly transport were two dozen impressed vehi-cles and some motor cycles. But we were to trainand classify our drivers so that we would beready to properly use our regular transport whenit was issued.

I am neither a good mechanic nor a good driver.But I had once taken a short course on farm me-chanics. Using that as the plan to follow andadding map reading and a bit on march disci-pline, we were away. We had five separate sub-jects and we rounded up quite a competentgroup of instructors in each. We had one hundredand twenty-five drivers to train. They had train-ing in military subjects as well. It was all inte-grated into a master plan by Major McKerron. AsI recall it, our “course” lasted three weeks. At theend of the course we had the various instructorsgive a series of tests and then Lts. Walsh, Rankinand myself took each driver out with a truck andrated his driving ability and his ability to read amap. One aftermath of this came six months later,when I was transferred to a platoon in the “C”Company. The driver mechanic of the platoonwas a L/Cpl Green. Off parade the first day Ioverhead Green telling a buddy - “There is theSOB who thinks that l am a third class driver.”

The Wartime Exploit of Major H.C. Mitchell 25

One night towards the end of our course we helda night convoy. We had nineteen motorcyclesmanned by Dispatch Riders. The boys had sometwenty trucks in fit shape to make the trip, whichwas to be of some thirty miles. All of the trip wasto be made with the strictest blackout discipline.We had no need for so many Dispatch Riders, buteveryone had been training enthusiastically andwe did not like to ground anyone.

So we took every vehicle that would run. It wasthe climax of our course and I asked Col. Potts ifhe would like to make the trip to see how theboys were doing. He would. Everything startedout beautifully. We got to a railway underpass atFleet where we were to make a turn. I got a miledown the turn and a Dispatch Rider came tearingup to say that we had lost half of our column.The Dispatch Rider on point duty at that turnhad miscounted the vehicles and in his eagernessto be on his bike had left his station too soon.

In the blackout it took us an hour or more to re-trieve our vehicles. Shortly after we had com-pleted our “course” for the drivers Macdonaldthe Transport Officer came back from his course.He knew what the army expected of a driver butthat phase of training had been passed and hewas never given the opportunity to train thedrivers that I had had.

The Colonel-in-Chief of the King’s Own York-shire Light Infantry, our affiliated regiment, wasthe Duchess of York who became Queen Eliza-beth, wife of George VI. She inspected our battal-ion on 8 April, 1940. King George had driventhrough our ranks very informally shortly afterwe had arrived in England. The Queen’s visitwas our first official recognition after we had hadan opportunity to train. It was a tremendousevent in the story of our Battalion. There was spitand polish with a vengeance for a few days.

Her Majesty inspected our Battalion on Queen’sParade between Aldershot and Farnborough.Then we did a “march past”. After the “MarchPast” we officers fell out and were whisked backto our quarters where we quickly changed intoservice dress uniform. Then we were posed onthe lawn by the official photographer so that wewere already when Her Majesty arrived. She satdown and the pictures were taken. Then each ofus were presented to Her Majesty. After that shehad lunch with the senior officers of our Battalionand the Toronto Scottish.

Potts had spent a great deal of time and thoughtpreparing for the Queen’s visit. He had beenmost meticulous about the dress of the officers.For the picture, our Service Dress must include adark coloured khaki dress shirt. Some of us didnot have that particular type and it was withsome difficulty that we got them all the same.

When the picture was developed there was Pottswearing a light coloured khaki shirt. During the“March Past”, when doing “Eyes Right”, I hadnoticed tears in Her Majesty’s eyes That evening,in the Mess, I told Potts about it. Very gruffly, hereplied, “Yes I know.” The Queen made a tremen-dous impression. She was so genuine. So inter-ested in everyone, so gentle, so deeply concernedabout the web of events which had enmeshed allof us.

Toward spring, I began to get my fill of people.Everywhere that I turned there were so many. Iwanted to get away by myself for a few hours sothat I could sort out my thoughts and get a betterperspective. If only I could have ridden aroundmy pasture fence!

On Sunday I went, by myself, for a walk alongthe Basingstoke Canal. I found a secluded spotand laid down in the sun. In the hour or so that Iwas there at least one hundred people stoppedand peered at me. Aman lying in the brush

The Wartime Exploit of Major H.C. Mitchell 26

alone, was really something in England.My second leave was Easter week which I spentin London. I attended one of the “off time” serv-ices in St. Pauls’. I was very disappointed. Myreal thrill was hearing Sir Thomas Beecham con-ducting the London Philharmonic Orchestra andChoir as they performed Handel’s “Messiah”. Itwas in Albert Hall. There was a pipe organ aswell. The performance was marvelous. Equallyimpressive was the sight of at least half of thegreat audience following the musical score as itwas being played.

One Sunday, early in April, Potts laid on an ex-cursion to the sea coast for the whole Battalion.We used all of our impressed vehicles and tooknearly everyone to the seaside town of Little-hampton, which was quite deserted at that timeof the year. It was not much of a day there, butthe trip through the countryside was wonderful.In my memory lives a most beautiful picture ofpeaceful England. As we crossed the hogsback atGuildford, that sunny Sunday morning, we cameupon a little ivy covered stone church sittingunder the beeches and surrounded by the Crociistrewn green fields. The church bell was ringingand from all directions people were walking intwos and three times to the church. It is the hap-piest and most peaceful memory that I have ofEngland.

“Oh to be in England now that April is here.”

After Dunkirk, where there was a real possibilityof a German invasion, normal tolling of churchbells was stopped. The tolling of the bells was towarn everyone that the invasion had begun.During this time in Tournai we developed somevery definite routines. The BBC news at nooncame at 12:30 just as we ate in the Officer’s mess.

Weston the biscuit manufacturer, had given ourBattalion some portable battery radios. Potts al-ways carried one of these radios into the mess

which he switched on for the news. Those werethe days when the “phoney” war gave way to theover running of France, We officers were fre-quently packed off to various meetings wheresome visiting general from the CIGS downwould address us. Time and again we were toldthat the “Boche has missed the boat.” “By not fin-ishing off France before the onset of winter theGermans had missed their opportunity to winand given us time to prepare.” This line was con-tinued until the spring offensive made it ridicu-lous.

I can still feel those tragic electric moments wheneach day, the news would tell of some fresh dis-aster. At first we were casual and philosophical.But as army after army was swept aside it be-came unbelievable. When the news was finishedPotts would shut off the radio. For a moment,everyone would sit, silent with his own thoughts.Then, to break the spell, Potts would jump upand, with a great commotion, leave with hisradio. Work was the great comforter.

The Wartime Exploit of Major H.C. Mitchell 27

Chapter 6: Bulford Camp

During April we, and the Toronto Scottish, spenta month doing field firing and training on Salis-bury Plains. Our camp was at Bulford. We livedin tents. A great portion of the time rain fell and itwas most disagreeable. We lived under Britisharmy conditions. Some things seemed so sense-less. I can still see the chief instructor’s hands,one cold wet day. He had us out in the opendoing some training. During all the time hishands were bare and a blue black in colour, fromthe cold. For some reason he did not wear glovesand it seemed so stupid to me.Nearby was the town of Amesbury. One Sunday,Vergne and I walked over there and stopped in ata tea house for refreshment. I casually1asked forice cream. I can still hear the waitress’s retort.“Where do you think you are - in London?”

Near Amesbury the RAF had an experimental airstation. They had some ninety different kinds ofaeroplanes. The Halifax and Lancaster bomberswere a revelation to me. It was incredible thatsuch huge things could be lifted off the ground.

I was on B Company’s strength. I had not doneany training with the Company at Farnboroughso I more or less tagged along with my platoon.As always happens, the platoon sergeant carriedthe load. The chief instructor, one day, quizzedme quite closely. I had spent my spare winter mo-ments with the pamphlet. I guess I had memo-rized some parts. At any rate this instructor, whohad written the pamphlet, was overwhelmed bygetting the text back, verbatim.

The two Battalions trained separately under thesame staff of the Netheravon Small Arms School.The climax of the period was to be a shootingcompetition between the two Battalions. Duringthe training, the Company, the platoon and thesection, with the best firing record was chosen torepresent each Battalion.

That was one of the most memorable days in thehistory of our Battalion. Many explanations aregiven depending on whether the speaker isToronto Scottish or Saskatchewan. LI.

The competition was held on a six hundred yardrange. On a sand embankment, six hundredyards away, were a dozen or so steel plates whichwould bounce when hit with the bullets. It was aclear dry day and there was a gala spirit in theair. Both Battalions had trained very hard. Eachwere determined to demonstrate their merits.

Major McKerron was a machine gun officer in theFirst War. The evening before the shoot, he veryquietly took the Armourer Sgt. and the twelvemachine guns to be used, off to a range wherethey zeroed the sights. No one in the TorontoScottish Camp thought to do so. That is a pointthat is rarely mentioned. The Toronto Scottishthought that zeroing the guns was not quitecricket. The instructional staff on the school werevery happy to find that our Battalion was so com-petent. We were training for war. At any rate theactual competition was begun on terms that werenot quite even.

For the competition the guns and stores were laidout on the ground, dismantled. The gun crew, onthe command to begin, ran thirty yards, pickedup stores, ran another thirty yards, and went intoaction. The first to hit the plates won. I havenever attended a sporting event anywhere whenthe competitive spirit and excitement was higher.It was a very thrilling occasion. Company, pla-toon, section, Officers, Sgts, and Cpls. TheSaskatchewan. LI won every event. It was a com-plete route.After that period of training the Saskatchewan.LI. was chosen as the Machine Group Battalionfor the 1st Division. The Toronto Scottish wereslated for the 2nd Division. It was a wonderfulfinish to a hard cruel winter.

The Wartime Exploit of Major H.C. Mitchell 28

There was an aftermath to this famous “shoot”which had a very bad effect on the Saskatchewan.LI. After the successful shoot, Potts very properlypraised all ranks for the tremendous effort thathad been made in the winter training. He usedthe results of the shoot as proof of the superior ef-fort that our Battalion had made. This was re-peated so often that everyone, even the Companycommanders, came to believe it implicitly. Withsome people it might not have mattered. But ourSecond in command, Maj. McKerron, was ex-tremely sensitive about his achievements. He hadbeen the officer in charge of training throughoutthe winter but of course each Company Com-mander had been personally responsible for hisown Company and was not too anxious to sharethe credit. Then this personal contribution ofMcKerron’s, in zeroing the guns, was casuallyoverlooked even by Potts. I think that it was amajor factor in undermining McKerron’s ego.

Nearby to Bulford camp was a British A.T.S.training camp. On the last Tuesday that we wereat Bulford, the A.T.S. staged a dance in our hon-our. We supplied the liquor. The A.T.S. lookedafter everything else. The Battalion had a grandevening.

One of the A.T.S. staff was Captain Gilmour. Herhusband was a lieutenant in the ColdstreamGuards. Capt. Gilmour’s mother was Mrs.Christie-Miller who owned the nearby ClarendonEstate. Mrs. Christie-Miller invited the officers ofour Battalion to have tea with her on the follow-ing Sunday.

The Clarendon Estate is the original estate of theDuke of Clarendon. It comprised of eight thou-sand acres. About the time of William the Con-queror, the king established a hunting park there.He built a huge castle - larger than Windsor Cas-tle - as a hunting lodge. The Duke of Clarendongot his “start” as the keeper of His Majesty’shunting estate. The old castle is in ruins. The

newer house of the Duke is a mile away from theruins. Part of it was built in 1540. The newer partwas built in 1850.