Listen to us—we know the solution: mapping the perspectives of African communities for innovative...

Transcript of Listen to us—we know the solution: mapping the perspectives of African communities for innovative...

This article was downloaded by: [Brought to you by Unisa Library]On: 22 February 2015, At: 23:49Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registeredoffice: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Click for updates

Conflict, Security & DevelopmentPublication details, including instructions for authors andsubscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ccsd20

Listen to us—we know the solution:mapping the perspectives of Africancommunities for innovative conflictresolutionAndreas VelthuizenPublished online: 17 Feb 2015.

To cite this article: Andreas Velthuizen (2015) Listen to us—we know the solution: mappingthe perspectives of African communities for innovative conflict resolution, Conflict, Security &Development, 15:1, 75-96, DOI: 10.1080/14678802.2015.1008219

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14678802.2015.1008219

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the“Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis,our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as tothe accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinionsand views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors,and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Contentshould not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sourcesof information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims,proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoeveror howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to orarising out of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Anysubstantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms &

Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Bro

ught

to y

ou b

y U

nisa

Lib

rary

] at

23:

49 2

2 Fe

brua

ry 2

015

Analysis

Listen to us—we know thesolution: mapping theperspectives of Africancommunities for innovativeconflict resolutionAndreas Velthuizen

Inspired by the need to find lasting solutions

to violent conflict, the author stated the

research question by asking ‘how can

community knowledge be given a new

centrality so that it can contribute to

innovative conflict resolution?’ In

answering this question, the author argues

that conflict mapping is a strong influential

instrument not only for community

research, but also to empower a

community to deal with conflict, promote

equity of discourse on all dimensions of a

conflict, as well as to create a web of equal

relationships among peace-builders to

resolve conflicts. The conceptual framework

addresses conflict mapping; the top-down/

bottom-up approach to conflict resolution

and introduces the concept ‘innovative

conflict resolution’. Examples of centralising

community knowledge in some African

societies are offered. The conceptual

framework and examples from Africa are

then applied to practical conflict mapping

that was performed as part of a community

engaged participatory research project with

a San community in South Africa.

Introduction

In his work, On Liberty, John Stuart Mill stated, ‘liberty, as a principle, has no application

to any state of things anterior to the time when mankind have become capable of being

q 2015 King’s College London

Dr Andreas Velthuizen is a Senior Researcher at the Institute for Dispute Resolution in Africa, College of Law,

University of South Africa (Unisa) where he is doing trans-disciplinary research in endogenous knowledge

management for conflict resolution, violent conflict prevention and restorative justice.

Conflict, Security & Development, 2015Vol. 15, No. 1, 75–96, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14678802.2015.1008219

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Bro

ught

to y

ou b

y U

nisa

Lib

rary

] at

23:

49 2

2 Fe

brua

ry 2

015

improved by free and equal discussion’.1 This assertion reminds us of the freedom of

association, beliefs and lifestyle and the condition that exercising these freedoms may not

harm others. Furthermore, it shows us that humankind can only improve itself through

discourse that recognises the equality of worldviews and the freedom of people to share

those views, irrespective of the quality of the window from which the world is viewed.

It guides people to become conscious of the needs of others, including restoration of

dignity where it was damaged and peace where it was broken. In practice, it compels

people into action, projecting the mind and physical resources to effect positive change.

It requires the never-ending quest for solutions brought by many innovative efforts,

continuously adapting to an ever-changing world, and making a lasting impact on the

reality of people, including those affected by violent conflict.

However, people who are suffering from the effects of recent or current conflicts do not

always have the privilege of participating in equal discourse to offer solutions. Therefore,

the need for renewed efforts to find innovative ways of ending conflicts, in discourse with

those affected by the conflict, inspired the research problem: ‘how can community

knowledge be given a new centrality so that it can contribute to innovative conflict

resolution?’ The aim of this article is therefore to discuss how the centrality of community

knowledge can be attained to end conflict, with specific emphasis on conflict mapping as a

method of equal partnerships in data collection, analysis and critical reflection between

peace-builders and communities in conflict.

To achieve this aim it is important to delimitate the research in geographical terms and

to investigate a specific research population with the expectation that the findings of the

research would expose valuable knowledge that can be applied to other places and peoples.

Therefore, the research focused on the community in the context of African society, citing

examples from Rwanda and Liberia of how community knowledge was centralised so that

it could contribute to innovative conflict resolution. In this article, the author argues that

conflict mapping is a strong and influential instrument not only for community research,

but also to empower a community to deal with conflict, promote equity of discourse on all

dimensions of a conflict, and create a web of equal relationships among peace-builders to

resolve conflicts.

This argument sets out from a conceptual framework addressing conflict mapping, the

top-down/bottom-up approach and conflict resolution through conflict mapping.

Examples of centralising community knowledge in Africa are then offered. The analysis of

the conceptual framework and examples from Africa is then applied to practical conflict

76 Andreas Velthuizen

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Bro

ught

to y

ou b

y U

nisa

Lib

rary

] at

23:

49 2

2 Fe

brua

ry 2

015

mapping that was performed together with the San community of Platfontein near

Kimberley (the capital of the Northern Cape province of South Africa) as part of a

community-engaged participatory research project to investigate the conflict resolution

practices of the San of Southern Africa.

Conceptual framework

An analysis of theoretical concepts on innovative conflict resolution and conflict mapping

as an instrument for centralising community knowledge is important when analysing

specific case studies, such as that of the San of Platfontein. The conceptual framework will

cover conflict mapping, the top-down and bottom-up approaches to conflict resolution

and innovative conflict resolution, including an analysis of these concepts in relation to

conflict mapping.

Conflict mapping

Wehr suggests the collective creation of a complete picture, preferably in the form of a

chronological and geographical map of the conflict, to display knowledge of the conflict.2

The map is then used as a holistic framework that includes all conflict variables to

determine recursive conflict patterns, enhance dialogue and interact to find solutions to

solve or transform a conflict.

De Coning and Carvalho found that conflict mapping enables assessment of the

dynamics between various powerful actors in the context or milieu in which the conflict

started or takes place.3 The map should include all elements of a conflict, such as the

people involved, the conditions of the conflict situation and an analysis of all stakeholders.

Conflict mapping enables issue analysis as part of conflict analysis as a starting point for

the design of strategies to engage with conflicting parties. The conflict map can be in the

form of a conflict tree that symbolises the core problem of the conflict and the effects of the

conflict, to generate discussions.

Raiskums suggests that displayed information should be interpreted through discourse

among participants to interpret data in the reality of its social and cultural context.4 In this

process, participants should apply critical thinking and reflective reasoning about beliefs

and actions to decide whether a claim is true or false. It involves the social practice of

participatory democracy, the willingness to consider alternative perspectives, the

Listen to us 77

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Bro

ught

to y

ou b

y U

nisa

Lib

rary

] at

23:

49 2

2 Fe

brua

ry 2

015

willingness to integrate new or revised perspectives into existing ways of thinking and

acting, as well as fostering critical thinking in others.

An analysis of these assertions shows the importance of specific conflict resolution

techniques where the emphasis is on revisiting the lived experiences of a community,

analysing it, learning from it and using it to innovate society by addressing the root causes

of conflict. The conflict map serves to display all the knowledge claims of knowledge

holders. If applied in the community context, it avoids breaking down variables in a

conflict into meaningless concepts by displaying a coherent picture of all variables. This

map is probably never complete, and is developed by participants into specific scenarios as

new knowledge and interpretations are added. Conflict mapping is therefore an important

aspect of centralising community knowledge with the ultimate objective of transforming

or solving conflict.

Furthermore, the analysis shows that research with full participation of the community

is a useful way of linking their customs, values and lived experiences to the need for

conflict resolution through an integrated research methodology that includes engagement

with the community to map and collectively interpret research results.

The top-down approach to conflict resolution: partial truths and temporary

peace

Highlighting three themes, Braithwaite asserts that there are many sequences of truth, justice

and reconciliation.5 The first theme proposes that expanding zones of bottom-up truth or

reconciliation often enables top-down truth-telling. Reconciliation in a specific context may

open the way to high-integrity truth-seeking. However, a second theme is proposed, which

claims that reconciliation can take place on a foundation of only partial top-down truths.

Where partial truth and reconciliation are mutually supportive, both truth-reconciliation

and reconciliation-truth sequences should be analysed. A third theme proposes the virtues

of a network governance of reconciliation, where peace-builders network across

organisations that are responsive to local voices, as a craft of responsive governance.

Michel Foucault reminds us that that there are many different discourses in society.6

Subjectivity and acceptance of unequal power relations are formed through engagement

with different discourses. True knowledge comes from social relations as the foundation

on which ‘relations with truth’ are formed, where all knowledge claims may be valid in a

specific cultural construct. In a relational or system network of power that dominates and

78 Andreas Velthuizen

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Bro

ught

to y

ou b

y U

nisa

Lib

rary

] at

23:

49 2

2 Fe

brua

ry 2

015

defines the social world, resistance to power emerges, especially when power is exercised by

regulating discourse by deciding who is allowed to speak and what discourses will be used

in knowledge production.7

In this regard, Levi-Strauss argues that people are considered subservient because they

are hungry and subsist in harsh material conditions without writing skills.8 However, they

are perfectly capable of understanding the world around them by applying intellectual

means, using a precise knowledge of their environment and the resources in it. Therefore,

their knowledge should have the same status as that of any ‘modern’ philosopher or

scientist. Despite cultural differences, the human mind has everywhere the same limited

capacity to understand the whole.

If these propositions are analysed, the question that is posed is how an epistemology of

power that is characterised by inequality can be challenged. From the outset, it is evident

that instruments are required that would lead to a fusion of knowledge where all

perspectives are considered and, if possible, fused into a collective perspective.

Furthermore, it is important to ensure that some communities, especially those in

conflict, are not marginalised in creating a general acceptance of what is ‘true’. This can

easily happen in a society where structural injustices persist, and people are so

overwhelmed by the dynamics of making peace that the perspectives of a large number of

affected people are neglected because of time pressures in the quest to find solutions.

Instruments of knowledge fusion are required that are sharp enough to be applied at the

right time to ensure conflict transformation, meaning the eradication (or mitigation) of

epistemological inequality, building or restoring relations with communities in conflict,

moving beyond partial truths, and preventing structural dysfunctions from causing re-

emerging violence. The analysis leads to the finding that the ontology of historical factors

shapes the structural injustices, including an imbalance in power between central rulers

and marginalised communities. The ending of conflict is not only about the ending of

violence, but is also a transformative process aimed at injustices, imbalances and

dysfunctions in society to ensure lasting solutions.

The bottom-up approach to conflict resolution: fromtruth-telling to reconciliation

In his book Reconciliation and Architectures of Commitment, John Braithwaite concludes

that the strong top-down architecture of a peace agreement is also potentially its greatest

Listen to us 79

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Bro

ught

to y

ou b

y U

nisa

Lib

rary

] at

23:

49 2

2 Fe

brua

ry 2

015

weakness, because it is unclear whether there is credible commitment to a final peace

arrangement in the case of a top-down approach.9 Peace requires a mutually enabling

relationship between a top-down credible commitment architecture and bottom-up

reconciliation. While the top-down architecture of peace is critical to secure peace, the

bottom-up reconciliation and reintegration process is more important.

In this regard, Rubinstein differentiates between technocratic and political conflict

resolution.10 Technocrats accept existing legal and other arrangements within state

infrastructures, where conflicting parties negotiate differences in state-sanctioned forums.

In contrast, political conflict resolution is more ambitious and is not only aimed at

resolving individual disputes, but contributes to the political will to change the structure,

and not maintain the system. According to Walklate the technocratic approach fails to

consider the centrality of a community’s trust in the capacity of the state to deliver.11 The

political approach insists that state institutions earn their trust, and is informed by the

personal, organisational networks of trust and power that lie within communities.

Narayan points out the link between empowerment and the effectiveness of

development, both in broader society and at ‘grassroots level’.12 When citizens are

engaged, and their voices and demands for accountability are heard, government

performance improves and dysfunctions like corruption are harder to sustain. Moreover,

informed citizen participation can facilitate consensus-building to support the difficult

and politically sensitive reforms needed to undertake reconciliation.

An analysis of propositions on the bottom-up approach reveals an emphasis on the

limitations of a technocratic approach to conflict resolution, especially in terms of trust-

building, reminding us that conflict resolution is mainly a political issue. It shows that

conflict resolution involves the state and all its subjects, of which the political dynamics at

the community level are an undeniable element, demanding political will for structural

change. Political will is required to involve communities in policy-making by giving

communities local ownership and control over conflict resolution processes.

Actors from outside the community are required to avoid imposing dysfunctional,

unjust systems or ‘scientific’ solutions on communities, but must instead follow a

humanistic approach to earn the trust and support of a community through respectful

intra-action. The community is not divorced from broader society but is intra-actively

linked with society, therefore requiring that the demands and pressures of communities be

addressed in order to turn influences flowing from there into support during

reconciliation and truth-seeking. Analytical instruments such as knowledge mapping,

80 Andreas Velthuizen

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Bro

ught

to y

ou b

y U

nisa

Lib

rary

] at

23:

49 2

2 Fe

brua

ry 2

015

which allows for connecting the ‘top’ with the ‘bottom’ and places them on an equal

footing, are needed to facilitate truth-telling in the quest for peace and reconciliation.

Innovative conflict resolution: weaving an integrated network of

peacemakers

Conflict management practitioners still tend to follow either the ‘Prescriptive Paradigm’

(believing that culture is not a barrier and that processes are readily transferable) or

the ‘Elicitive Paradigm’ (cultures have their own unique mechanisms of dispute

management that do not translate easily). However, an integrative approach is most

likely to succeed, recognising that cultures differ in the way they resolve disputes.

Furthermore, practitioners from outside the community must be aware of the culture in

which they are operating, as well as the peculiarities of their own culture.13

According to Ury, conflict resolution is a part of the culture of every society.14 In each

society, some methods are favoured over others. Although each culture in the world may

be unique, underlying each is its own specific, usually tacit, agreement or system that

determines how to resolve disputes. At the same time as Western practitioners have tried to

utilise Dispute Systems Design (DSD) principles in different contexts, other societies have

been rediscovering traditional forms of conflict resolution.

Lederach refers to ‘middle-out capacity’ which means strategic networking to weave

webs of relationships and activities to get a small group of the right people involved in the

right places.15 The main ingredient is the critical ‘yeast’ not the critical mass. Braithwaite,

using the Bougainville peace process in Papua New Guinea, asserts that ‘little’ peacemakers

linking together can give momentum towards peace, even when top-down peacemakers

are assassinated and the leaders of the war remain spoilers or when profit-seeking

international spoilers interfere.16 Once the tipping point of bottom-up support for peace

was passed, progressive elements in the military and political elite moved around the

spoilers to join hands with the great mass of Bougainvillean peacemakers, committing to

forgiveness and putting revenge aside permanently.

Analysing the above propositions indicates the importance of integrating the top-down

and bottom-up approaches into an innovative approach that recognises that cultures differ

in the way they resolve conflicts. Cultural awareness is the essence of an integrated

approach, especially knowledge of how people in a conflict situation tacitly agree on how

their dispute resolution system functions in their specific cultural context. Such a system

Listen to us 81

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Bro

ught

to y

ou b

y U

nisa

Lib

rary

] at

23:

49 2

2 Fe

brua

ry 2

015

will probably include traditional forms of conflict resolution, but it may also be found that

many practices from outside the community are accommodated in customary practices.

It is for peace-builders to discover the individual peacemakers in a community and link

them together in a web of relationships so that a small set of peace-minded people can

serve as the critical ‘yeast’ in resolving conflict. It is just possible that such a web of

relationships may replace the notion of ‘bottom’ and ‘top’, creating an equal power

relationship where knowledge from a community could enjoy central and equal status with

knowledge from the ‘top’. Such an integrated body of knowledge could enable a critical

mass of people to move around vengeful spoilers, to focus on forgiveness and

reconciliation.

It is towards the ideal of integrating modern with customary practices that a suitable

instrument, such as conflict mapping, is required, where peacemakers can be involved.

It implies that the community, and those they consider as their leaders, need to be an

important part of conflict resolution. The challenge arises when such a system does not

function well and fails to resolve internal disputes or to deal with disputes with other

entities. It is then that a specific design is required, founded on the knowledge of the

community, displayed on a conflict map, on what conflict resolution practices worked well

in the past and should be tried again in a more systematic and formal way to ensure peace.

Centralising community knowledge through conflictmapping in Africa

The Rwanda experiment

The relevance and appropriateness of customary African practices for conflict resolution

was tested after Rwanda experienced a genocide in 1994 that left an estimated 800 000

Rwandans dead and many others displaced or wounded. The Rwandan government then

implemented a judicial system to ensure the participation of the community in the process

of investigation. Subsequently the Gacaca Traditional Court System, a legal system

inspired by tradition, was constituted together with the International Criminal Tribunal

for Rwanda (ICTR) and the national penal courts.17

The ‘mission’ of the Gacaca courts was to achieve ‘truth, justice, reconciliation’, and they

aimed to promote community healing by making the punishment of perpetrators of

crimes quicker and less expensive. Gacaca is the revival of a traditional court system of

82 Andreas Velthuizen

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Bro

ught

to y

ou b

y U

nisa

Lib

rary

] at

23:

49 2

2 Fe

brua

ry 2

015

‘wise men’ symbolising justice at the village level. Originally, the Gacaca courts constituted

village assemblies, presided over by elders who dealt with mediation, to settle village or

family disputes. The type of conflict dealt with by the Gacaca courts was related to social

cohesion, tolerance and peaceful coexistence in the densely populated rural communities.

Eventually the Gacaca Court System accumulated a body of knowledge that was valuable

in determining the causes, the modus operandi and the consequences of genocide.18

Unfortunately, since its inception the government of Rwanda has manipulated national

reconciliation to boost party political support. Furthermore, the system did not contain a

strong enough reparative element and the Gacaca courts still function within a society

marked by ethnic divisions, polarised by ‘collectivising guilt’. Although experiments such

as the Gacaca courts are needed and could have been a successful model for societies in

transition, they have not resulted in a free dialogue between the government and the

population. The Rwandan experiment showed that to break out of a cycle of violence and

vengeance, a new way should be found to achieve reconciliation between perpetrators and

victims, together.19

According to Malan, since the end of the last century, conflicts in Africa are addressed in

the environment where the conflict emerged.20 The new approach involves realistic,

responsible and practical conflict resolution as a dynamic element of home-grown, people-

centred relation-building and socio-economic development of local communities.

Normative issues are considered when the root causes of a conflict are explored to take

timely precautions against conflict and to effect reconciliation. A shared understanding of

the past and the present contributes to restoring, maintaining and building relationships.

The interest and involvement of the people affected by a dispute is in the foreground when

the community takes part in affirming an agreement and monitoring its implementation.

If the generalised statements of Malan are evaluated together with the Rwandan

experience, it is found that the integration of the top-down and bottom-up approaches

was not successful in the case of Rwanda. Although an honest attempt was made use the

traditional legal system (the Gacaca courts) for truth-telling and reconciliation, the

unequal power relationships perpetuated by the Rwandan government prevented a web of

relationships emerging that would have enabled peace-makers to claim that ‘knowledge

from the lawn’ played a decisive role in truth and reconciliation in Rwanda. A top-down

international effort in which the Rwandan government played a decisive hegemonic role

together with powerful international partners resulted in the relative peace and prosperity

that Rwanda experiences today. The majority of the people who live in the villages in

Listen to us 83

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Bro

ught

to y

ou b

y U

nisa

Lib

rary

] at

23:

49 2

2 Fe

brua

ry 2

015

Rwanda remain outside the mainstream of maintaining the peace, a very dangerous

situation that can cause renewed outbreaks of violence at any time.

Weaving the web of lasting peace

Brock-Utne is of the opinion that African practices for conflict resolution involve

‘warping’ and ‘weaving’. The involvement of the family, neighbourhood and the elders can

be described as ‘warping’. ‘Weaving’ indicates the fundamental value of human

togetherness called Kparakpor in Yoruba, Ubuntu in Nguni and Ujaama in Kiswahili. The

priority is the restoration of relationships, which are more important than personal

interests, taking into account past and current tensions.21 Reconciliation begins with the

involvement of only a few people, later calling on the whole community to deal with the

conflict. In its ideal state, the African customary conflict resolution process is non-dualistic

and owned by the whole community.22 Humaneness is central to customary practices,

encompassed in compassion, sharing, reciprocity, upholding the dignity of personhood,

individual responsibility to others and interdependence.23

Customary African practices promote the inclusion of all worldviews that arise from the

critical reflection of individuals and groups who exercise contemplation to shape their

world, even if these views are inconsistent with contemporary paradigms. In this regard,

the diverse ideas, self-awareness of thoughts and comprehensive understanding of reality

of the ‘African Philosopher’ (the intellectual of traditional African society whose ideas are

undocumented or unwritten, but whose thoughts can be reasonably reconstructed) that

form the intellectual and moral foundation of African society play an important role.24

The African way of knowing is also endogenous, the result of lived experiences found

within a community affected by contact with other communities. It assumes that the

knowledge of the community is not static but develops continuously. Endogenous means

viewing the world from the Afrocentric vantage point of local people, empowering African

people. A participatory process builds convergences and sustained interaction between

formal and informal institutions while empowering community beneficiaries through

programmes and projects.25

An example of this conflict resolution approach can be found in the ‘Palava Huts’ and

truth-telling programme of Liberia, a programme intended to create opportunities for

dialogue and peace-building. Mediation is done by a respected elder from the community.

According to recommendations of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC)

84 Andreas Velthuizen

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Bro

ught

to y

ou b

y U

nisa

Lib

rary

] at

23:

49 2

2 Fe

brua

ry 2

015

report of Liberia, ‘all perpetrators, their associates, warlords, financiers, organizers,

activists; whether named or not in the TRC report but who have committed some wrong’

are to submit to the Palava Hut process. Women, children and victims of sexually based

violence should have the opportunity to participate. The process should conform to

human rights standards, especially the protection of women and children. Community

forums and other broader national and regional mechanisms should also be in place for

truth-telling that should lead to community reconciliation. Community-based measures

should not replace criminal accountability and should avoid potential tensions between

the Palava Hut programme and the statutory justice system.26

Subsequently participants were trained in strengthening families, clans and traditional

institutions as part of a restorative process of how the Palava Hut Dialogues could

contribute to democratisation and development in Liberia, dealing with individual and

societal problems through dialogue and peaceful means. Community residents were

encouraged to present their problems in the open forum, creating an environment in

which people felt free and confident to analyse their problems in ways that generated

knowledge about the source of and solutions to the problems. Broader discussion of

problems also took place in alleys and on sidewalks, organised largely by unemployed

people, as ‘talking centres’ in ‘sites of knowledge’ as an extension of the Palava Hut

dialogues. Directed at generating problem-solving knowledge, participants spoke in the

languages with which they were most comfortable.27

If these affirmations and examples from Africa are analysed, it seems viable and

necessary to attempt conflict resolution in the environment where the conflict emerged,

according to customs that are applicable to specific cultural contexts and socio-economic

conditions. The environment means the physical location where the root causes of a

conflict, the historic timeline, home-grown and people-centred understanding and

solutions to a conflict can be researched. It is in this context that modern and universally

accepted practices (such as conflict mapping) can be used, involving customary practices

for gathering, analysing and reflecting on knowledge appropriate to the conflict. It is by

gathering around a conflict map that the common humaneness and human togetherness

of participants are achieved, where a small group of people can start ‘weaving’

understanding and solutions in a non-dualistic way through dialogue and truth-telling.

The conflict map becomes the collective window through which a whole community

(including the elders, women and even children, excluding nobody) looks at a conflict as

the point of departure in moving relationships and institutions towards reconciliation

Listen to us 85

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Bro

ught

to y

ou b

y U

nisa

Lib

rary

] at

23:

49 2

2 Fe

brua

ry 2

015

between perpetrators and victims. The conflict map becomes the centre of dialogue, expanding

to other sites in the community. Eventually a community site of knowledge develops, where

problem-solving knowledge is generated towards solutions and can contribute to

democratisation and development. At this point capacity-building by key facilitators is

needed, who can use the endogenous knowledge (knowledge that has grown from a fusion of

knowledge in a community over time) to facilitate the peace-building process.

From the analysis, it is furthermore inferred that solutions are born from collective

interpretation, involving the thinkers of the community to reflect critically on what the

holistic picture of appreciative enquiry reveals, and to complement the views of other

participants with their own views, opening the door to solutions. Such solutions are not

only practical, but are supported by deep philosophical thinking.

The analysis also shows that a community site of knowledge would be difficult to

manipulate from a ‘top-down’ position (such as in the case of Rwanda) and holds a

powerful reparative element if the knowledge is used to initiate dialogue with the

government. Civil society at the community level can contribute meaningfully to a body of

knowledge that can be used in the process of managing, reconciling and restoring

relationships at the regional and national levels. For instance, ‘top’ structures can then use

this shared knowledge to focus on broader issues such as persisting ethnic divisions,

criminal accountability, reparations for victims and other tensions through national and

regional mechanisms to ensure conformation with human rights standards and

humanistic principles.

Conflict mapping: the case of the San of Platfontein

Background to the San

Using mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) tracing, the San, the First People of Southern Africa,

were traced to the last glacial maximum (approximately 20 000 years ago) and further back

to approximately 190 000 years ago to the ‘Mitochondrial Eve’, the common line from

which all Africans originate.28 Today a distinction is made between San language

groupings, with dialects that are not mutually intelligible being spoken in different parts of

Southern Africa. For instance, the Khwe dialect is spoken by the San of the Okwa Valley of

Botswana, the central Kalahari Desert, north-east Botswana, south-east Zambia and

western Zimbabwe, while !Kung is spoken by the San living in Namibia, north-west

Botswana and southern Angola.29

86 Andreas Velthuizen

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Bro

ught

to y

ou b

y U

nisa

Lib

rary

] at

23:

49 2

2 Fe

brua

ry 2

015

Rationale for the San of Platfontein as conflict resolution case study

Although the general history of the San of Platfontein is as part of the rest of the San of

Southern Africa, the community is an ideal case study because of their unique history of

involvement in conflicts over the past 60 years. Since the late 1960s, the !Kung and Khwe

served in the Portuguese military in southern Angola as trackers (called ‘flechas’). In 1974,

when Portugal handed over its colonies, they also withdrew fromAngola and the first group

of !Kung soldiers crossed the border into Namibia, followed by Khwe communities.

On arrival, they were formed into amilitary unit to combat insurgents from the South-West

African Peoples Liberation Army (Swapo) as part of the former South African Defence

Force (SADF). The unit (including their families) settled at a based called Alpha (later

Omega) in what was then called the Western Caprivi. In 1982, a second San base was

established at Mangetti Dune in northern Namibia. In March 1990, after the independence

of Namibia, the San were resettled near Kimberley, the capital of the Northern Cape

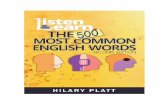

province of South Africa (see Figure 1 for a map of the location of the San).30

In 1999 the !Kung and Khwe became owners of the farms Platfontein, Wildebeeskuil

and Droogfontein near Kimberley after almost a decade of living in tents near

Schmidtsdrift on the Vaal River. In June 1999, they were officially awarded the title deeds

to the farms by the late President Nelson Mandela. Today, the major challenges facing

the !Kung and Khwe are internal divisions and segregation where they live in spatially

segregated settlements at Platfontein.31 This ongoing social distance and tension between

the !Kung and Khwe, with the intensification of the struggle over access to jobs

(including employment opportunities at the new farms) and housing, persists. However,

there is hope that the youth will be able to overcome this divide. These divisions have

been aggravated by delays in the provision of infrastructure and have contributed to

high levels of frustration and conflict.32

According to Boulle, the San, in general, have lived traditional lives for thousands of

years.33 In many cases, the lack of technological refinement contradicts the sophistication

of the conflict resolution practices of the San, which have evolved without courts and a

formal state system and are suited to the needs of a collective hunter-gatherer society.

Ury, basing his arguments on research among the San, asserts that their traditional

methods constitute a complete and effective conflict resolution system.34 Such a system

includes the prevention of disputes; resolving disputes by healing emotional wounds;

reconciling divergent interests; determining which rights and norms are at stake and have

Listen to us 87

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Bro

ught

to y

ou b

y U

nisa

Lib

rary

] at

23:

49 2

2 Fe

brua

ry 2

015

precedence; testing relative power; averting the use of power-based strategies; and

containing unresolved disputes to prevent escalation into violence. According to Ury, the

secret of the San for managing conflicts is the vigilant, active and constructive involvement

of the community. Community involvement includes practices such as teaching the

children to avoid violence and disputes, discussions led by the elders to eradicate negative

feelings, trance dance, consensual decision-making, confronting the offender with

witnesses, testing relative power by deciding who needs whom the most, and containing

violence by keeping parties away from each other and from weapons.

The findings of Ury and Boulle apply to the traditional San in general, and are not

necessarily applicable to all San communities, that may have different and unique

experiences of conflict, such as the San of Platfontein. Therefore it was decided that the San

community of Platfontein was a suitable case study for research into African conflict

resolution models, because this community was exposed to and formed part of the totality

of conflict dynamics in the Southern Africa sub-region for many decades.

Figure 1. Location of the !Kung and the Khwe of Platfontein.

Source: Robins et al., Assessment of the Status of the San.

88 Andreas Velthuizen

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Bro

ught

to y

ou b

y U

nisa

Lib

rary

] at

23:

49 2

2 Fe

brua

ry 2

015

Community-based participatory research with the San community of

Platfontein

From September 2013, the Institute for Dispute Resolution in Africa, at the College of Law

of the University of South Africa (Unisa), has conducted community-based participatory

research with the informed consent of the San community of Platfontein. The research is

conducted in three phases, namely a Discovery Phase that was concluded in September

2014, a Design Phase which is due to end in March 2015, followed by an Implementation

Phase in 2015 when the designed solutions will be implemented and improved. The

research methodology was presented to scholars and practitioners at the International

Academic Conference on Social Sciences (IACSS 2013) on 27–28 July 2013 in Istanbul,

Turkey, and discussed during a master class presentation at the Anton de Kom University

of Suriname, Paramaribo on 13 February 2014 to ensure that the research methodology

adheres to international standards of academic rigour.

The discovery phase resulted in more than 200 research reports from semi-structured

interviews, focus group meetings and interpretation workshops, attended by all

knowledge holders who provided informed consent to participate.35 The participants in

the semi-structured interviews and focus groups included men and women, as well as

community members of all ages, adhering to the principle that no voices will

be silenced.

Interpretative conversations were conducted with the elders of the Platfontein

community and the leaders of the San community of Andriesvale (230km north of the

town of Upington, about 600km from Platfontein) to compare the research results with

other San communities who live in different circumstances but with similar histories of

social exclusion.

During the interpretative conversations, important discourse took place between

community members and academics from many different disciplines. The participating

scholars, elders and leaders added significant value to the results of the research,

looking at conflict and conflict resolution from overlapping but different perspectives.

A holistic picture began to take shape, displayed on a conflict map in the shape of a

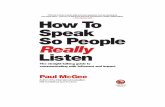

Baobab tree, a tree indigenous to the area where the San live (Figure 2). The ‘Baobab

Map’ was used to collate and analyse the data obtained from the narratives that was

captured during the focus groups, semi-structured interviews and interpretation

conversations. Using poster paper, colour pens and colour stickers, the map was laid

Listen to us 89

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Bro

ught

to y

ou b

y U

nisa

Lib

rary

] at

23:

49 2

2 Fe

brua

ry 2

015

out on tables in the middle of a lecture room situated in a community knowledge

centre (a facility especially established for the purpose of conflict resolution research).

The design phase that started in September 2014 consists of a series of conversations

with community members, seminars with scholars and practitioners and an international

conference to design conflict resolution architecture. During these events, an electronic

version of the Baobab Map is displayed to entice critical thinking and reflective reasoning

about beliefs regarding the actions and commitments, which need to be undertaken to

intervene in the continuing cycle of poverty and conflict in the community. In the

workshops argument maps are used as a logical extension of the Baobab Map to deliberate

issues, ideas and arguments associated with solving the problem of violent conflict.

The most important limitation on the research is that of language. All interviews were

conducted in !Xung and Khwe, languages that can only be written down in a very basic

way. Therefore, the interviews were captured by field researchers in Afrikaans (a common

language spoken in the community) or in English, where the field researcher had the

confidence to do so. All reports were then translated and typed into English for processing.

The result is that some data may be lost in translation, but the sufficient number of

interviews and triangulation in terms of research methods assured the accuracy of research

Figure 2. The Baobab map.

Source: The Author.

90 Andreas Velthuizen

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Bro

ught

to y

ou b

y U

nisa

Lib

rary

] at

23:

49 2

2 Fe

brua

ry 2

015

findings. The oral culture, illiteracy and fading memory, especially among older people,

also posed a challenge in keeping interviews structured. In most cases research questions

resulted in informal narratives that had to be summarised later, by listening to recordings

or looking at video clips made of some interviews. The following quote (captured from a

Khwe narrative in Afrikaans and then translated into English), illustrates this dilemma.

Everybody who wants to fix the relationship must gather underneath a tree.

Both the guilty and innocent parties will be given the opportunity to talk and

say what they think of the court. The problem will be solved in the court and the

accused must pay the victim in front of everybody. After forgiveness, the

relationship will be fixed.36

In this specific case, the response was in the form of a 15-minute informal narrative

explaining the functioning of the traditional court, using very colourful language that

somebody with an intimate knowledge of Khwe could understand and capture (nobody

else has the ability). The researcher had to capture the gist of the narrative so that it could

be valuable data, useful for collation with other research reports, analysis and

interpretation.

Despite these challenges, at the conclusion of the Discovery Phase, sufficient valid data

were available to populate all the variables visible on the conflict map, resulting in the

fusion of collective perspectives that will survive the rigour of academic scrutiny, as well as

informing conflict resolution initiatives.

Mitigating a history of top-down hegemony

The Discovery Phase of the research revealed that the San experienced a specific kind of

structural injustice, one that involved continuous intrusion of their land by many other

people, mostly from other parts of Africa. These peoples were powerful in terms of military

might and possessions and showed a hunger for land to feed their cattle and themselves.

Under this imbalance of power, the San had no choice other than to escape into the desert

or remote savannah forests or to become slaves of their African masters.

During colonial times, many of the San clans in the savannah areas ended up as soldiers

of Portuguese colonial rulers while others remained slaves of African communities in

Angola. During apartheid this slavery was ended, but the powerful system of apartheid

rendered the San powerless nevertheless. A militarised rules-based system had a lasting

influence on the traditional customs of the San at Platfontein. The clans who preferred to

Listen to us 91

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Bro

ught

to y

ou b

y U

nisa

Lib

rary

] at

23:

49 2

2 Fe

brua

ry 2

015

remain in Namibia and Angola became the most marginalised communities in Africa. The

San therefore have a history of conflict resolution that was characterised by avoidance by

moving away from trouble, allying themselves during the Cold War with belligerents (who

appreciated their bushcraft and tracking skills) who presented alternatives to hunting and

slavery.

The democratic nature of South African society, where the !Kung and Khwe currently

reside, shows a political will to involve all San communities in policy-making in exchange

for votes that can determine the outcome of elections in the specific ward where they

reside. However, the San community has very little political power and therefore

governance structures do not consider them a high priority in the allocation of resources

for service delivery. Therefore, the relationship with local authorities remains tense

because the San community are still seen by many local residents as immigrants from

Angola, and therefore remain marginalised in a modern society. Furthermore, disruptions

were caused when clans were located close to each other in township settings, as well as

close to other townships. This closeness brought in too many influences such as drugs and

criminality, putting pressure on the community.

The community of Platfontein has local ownership and control over the farms where

they live, managed by a Community Property Association (CPA), a statutory body. This

body needs to work closely with the local Sol Plaatjies Municipality. However, it was

discovered that the traditional conflict resolution practices, a strong asset of the traditional

San, were seriously disrupted by having lived previously in a militarised rules-based

society, and now in a modern system. The pressure of social ills and neglect by all levels of

government remains a major challenge for the community, which finds it difficult to

negotiate with modern structures, preventing them from breaking out of the pressures of

state hegemony.

Conflict mapping, especially the conversations that take place among leaders, scholars

and practitioners, proved an excellent instrument to mitigate top-down hegemony

founded on the political, social and epistemological inequality that persists in South

African society, a consequence of structural dysfunctions in society. Gathering around a

map that contains the fusion of many voices that were previously silenced creates the

opportunity to challenge the perpetuation of inequality and dominant paradigms.

Furthermore, it creates a new awareness among many people, that a transformative process

aimed at redressing injustices is needed to bridge the gap between the ‘top’ and the

‘bottom’ to attain lasting peace.

92 Andreas Velthuizen

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Bro

ught

to y

ou b

y U

nisa

Lib

rary

] at

23:

49 2

2 Fe

brua

ry 2

015

Innovative conflict mapping

The ongoing community-based participatory research with the community shows that the

restoration of traditional practices, complemented by good practices learned from other

scholars and practitioners, will probably not only empower the community to deal with its

own internal conflicts, but also capacitate them to handle complex relationships with

governance structures and with modern society in general.

Conflict mapping, as applied in Platfontein, is innovative in the sense that it creates

equal power relationships and status, integrating knowledge from both modern university

practitioners and the village community. Furthermore, a new cultural awareness is created

among scholars and practitioners from outside the community, who recognise that the

sometimes tacit customs that are embedded in the village community to resolve internal

conflict may be just as effective, or probably more effective, than models that are applied

successfully elsewhere. It is therefore vital that the researcher allows local community

ownership and control over conflict resolution processes all the time, with the researcher

assuming the role of facilitator, learner and trusted advisor.

It was also confirmed during conversations around the map that to resolve conflict

requires moderating those individuals who are attempting to silence voices from a position

of perceived superiority. During the research, it was experienced that political dynamics on

a community level could not be avoided, but should be treated with wisdom so that trust

was not compromised. Treating potential spoilers with respect and recognising their

dignity earned their trust, opening the way to drawing them in around the conflict map

where they could develop the political will to influence structural changes, truth-seeking

and reconciliation.

It was discovered that a traditional system of conflict resolution is not fully functional,

and that conflict resolution practices that worked well before need to be revived and

reinforced with good practices that have proved to be successful in other conflict

situations. For instance, the research revealed that the endogenous knowledge of the

community about how to avoid conflict, together with the values of mutual respect and

respect for personal dignity, are important building blocks for lasting peace. Furthermore,

during conflict mapping individual peacemakers were identified who could take the lead

in weaving a web of relationships that can keep out spoilers (if they cannot be avoided),

work towards truth-telling and forgiveness and tip the scale towards healing and

reconciliation in a systematic way.

Listen to us 93

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Bro

ught

to y

ou b

y U

nisa

Lib

rary

] at

23:

49 2

2 Fe

brua

ry 2

015

Conclusions

This article set off with the aim of discussing how the centrality of community knowledge

can be attained to end conflict, with specific emphasis on conflict mapping as a method to

equalise discourse with communities in conflict. This aim was achieved by linking the

theoretical concepts of innovative conflict resolution and conflict mapping, applying them

to the African context and finally offering a case study of the San of Platfontein to illustrate

how conflict mapping can be used to attain the centrality of community knowledge for

conflict resolution and transformation.

It was found that conflict mapping is a strong influential instrument not only for

community research, but also to empower a community to deal with conflict, promote

equity of discourse on all dimensions of a conflict, and create a web of equal relationships

among peace-builders to resolve conflicts. Empowerment of a community means building

the capacity of the community to engage with hegemonic structures and dialogues on an

equal footing to deal with modern pressures, including disputes that could lead to

violence. Equity of discourse on a conflict involves the restoration of relationships inside

the community and with the rest of society in such a way that disputes are avoided and

people resolve their differences with humanistic principles as a point of departure,

including respect for human rights, dignity and togetherness. The ideal place to start

creating a web of equal relationships is through conversations around an instrument such

as the conflict map as a centre of dialogue where the synthesis of many narratives can be

viewed, discussed and argued. This leads to trust-building, collective understanding, inter-

generational and inter-cultural sharing of knowledge, joint solutions and implementation

of interventions. It is around the conflict map that a network of peacemakers is formed,

departing from the community as a site of knowledge to resolve conflict and prevent

disputes from turning violent.

Endnotes1. Xander, On Liberty, 52.

2. Wehr, Conflict Regulation.

3. De Coning and De Carvalho, ACCORD Peacebuilding

Handbook, 93–100.

4. Raiskums, ‘An Analysis of the Concept Criticality’.

5. Braithwaite, ‘Truth, Reconciliation and Peacebuilding’,

30.

6. Foucault, The Order of Things.

7. Ibid.

8. Levi-Strauss, Myth and Meaning, 12–15.

9. Braithwaite et al., Reconciliation and Architectures of

Commitment, 65.

10. Rubenstein, ‘Conflict Resolution and Structural

Sources’, 173–195.

11. Walklate, ‘I Can’t Name any Names’, 208–209.

12. Narayan, Empowerment and Poverty Reduction, xviii.

94 Andreas Velthuizen

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Bro

ught

to y

ou b

y U

nisa

Lib

rary

] at

23:

49 2

2 Fe

brua

ry 2

015

13. Brahm and Ouellet, ‘Designing New Conflict Resolution

Systems’.

14. Ury, ‘Conflict Resolution among the Bushmen’, 379–

389.

15. Lederach, The Moral Imagination, 80–91.

16. Braithwaite et al., Reconciliation and Architectures of

Commitment, 86.

17. Nabudere and Velthuizen, Restorative Justice in Africa,

48–55.

18. Ibid.

19. Ibid.

20. Malan, Conflict Resolution Wisdom from Africa, 93.

21. Brock-Utne, ‘Indigenous Conflict Resolution in Africa’,

14–15.

22. Nabudere, ‘Ubuntu Philosophy’, 19.

23. Faris, ‘Dispute Resolution’.

24. Asouzu, The Methods and Principles, 115–116.

25. Houtondji, ‘Knowledge of Africa’, 10.

26. Nabudere and Velthuizen, Restorative Justice in Africa,

112–117.

27. Ibid.

28. Oppenheimer, Out of Africa’s Eden, 40.

29. Bleek and Lloyd, Specimens of Bushman Folklore.

30. Robbins, The Story of South Africa’s Discarded San

Soldiers.

31. Ibid.

32. Robins et al., Assessment of the Status of the San, 2.

33. Boulle, ‘A History of Alternative Conflict Resolution’,

130.

34. Ury, ‘Conflict Resolution among the Bushmen’, 379–

389.

35. San Dispute Resolution Oral Archive. Available at:

http://uir.unisa.ac.za.

36. Interview with Elisa Kiyanga by Karina Shiwarra,

Caprivi Street, Platfontein, 4 September 2014. Available

at: http://uir.unisa.ac.za/handle/10500/13921 [San Dis-

pute Resolution Oral Archive].

ReferencesAsouzu, I.I., 2004. The Methods and Principles of Comp-

lementary Reflection: In and Beyond African Philosophy.

University of Calabar Press, Calabar.

Bleek, W.H.I. and L.C. Lloyd, 1911. Specimens of Bushman

Folklore. George Allen & Company, London.

Boulle, L., 2005. ‘A History of Alternative Dispute

Resolution’. ADR Bulletin 7(7), 130.

Brahm, E. and J. Ouellet, 2003. ‘Designing New Dispute

Resolution Systems’. In Beyond Intractability, eds.

G. Burgess and H. Burgess. Conflict Information

Consortium, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO,

Available at: http://www.beyondintractability.org/essay/

designing-dispute-systems [Accessed 7 January 2015].

Braithwaite, J., H. Charlesworth, P. Reddy and L. Dunn, 2010.

Reconciliation and Architectures of Commitment: Sequen-

cing Peace in Bougainville. The Australian National

University Press, Canberra.

Braithwaite, J., 2013. ‘Truth, Reconciliation and Peace-

building’. In Peace in Action: Practices, Perspectives and

Policies that Make a Difference, eds. R. King, V. MacGill

and R. Wescombe. King MacGill Wescombe Publi-

cations, Wagga Wagga, 30–46.

Brock-Utne, B., 2001. ‘Indigenous Conflict Resolution in

Africa’. Paper presented to the weekend seminar on

indigenous solutions to conflicts held at the Institute for

Educational Research, University of Oslo, 23–24

February. Available at: http://www.africavenir.org/

uploads/media/BrockUtneTradConflictResolution.pdf

[Accessed 5 October 2014].

De Coning, C. and G. De Carvalho, 2013. ACCORD

Peacebuilding Handbook. The African Centre for the

Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD),

Umhlanga Rocks.

Faris, J., 2011. ‘Dispute Resolution: Towards a New Vision’.

Paper presented at the Fifth Caribbean Conference on

Conflict Resolution, Jamaica, April. Available at: http://

www.unisa.ac.za/ [Accessed 27 October 2011].

Foucault, M., 1970. The Order of Things: An Archaeology of

the Human Sciences. Vintage Books, New York.

Houtondji, P.J., 2009. ‘Knowledge of Africa, Knowledge of

Africans’. RCCS Annual Review 1, 7–10.

Lederach, J.P., 2005. The Moral Imagination: The Art and Soul

of Building Peace. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Levi-Strauss, C., 1978. Myth and Meaning. Routledge,

London.

Malan, J., 1997. Conflict Resolution Wisdom from Africa.

African Centre for the Constructive Resolution of

Disputes (ACCORD), Durban.

Nabudere, D.W., 2011. ‘Ubuntu Philosophy. Memory and

Reconciliation’. Available at: http://www.grandslacs.net/

doc/3621 [Accessed 24 January 2012].

Nabudere, D.W. and A. Velthuizen, 2013. Restorative Justice in

Africa: From Trans-Dimensional Knowledge to a Culture

of Harmony. Africa Institute of South Africa, Pretoria.

Narayan, D., 2002. Empowerment and Poverty Reduction:

A Sourcebook. The World Bank, Washington, DC.

Oppenheimer, S., 2004. Out of Africa’s Eden: The Peopling of

the World. Jonathan Ball, Johannesburg.

Raiskums, B.W., 2008. ‘An Analysis of the Concept Criticality

in Adult Education’, Capella University. Dissertation

Abstracts International 69(07). ProQuest document ID:

1584073261.

Robins, S., E. Madzudzu and M. Brenzinger, 2001. Assessment

Listen to us 95

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Bro

ught

to y

ou b

y U

nisa

Lib

rary

] at

23:

49 2

2 Fe

brua

ry 2

015

of the Status of the San in South Africa, Angola, Zambia

and Zimbabwe. Report No. 2 of 5. Legal Assistance

Center, Windhoek.

Robbins, D., 2007. The Story of South Africa’s Discarded San

Soldiers. Jonathan Ball Publishers, Johannesburg.

Rubenstein, R.E., 1999. ‘Conflict Resolution and Structural

Sources of Conflict’. In Conflict Resolution Dynamics,

Process and Structure, ed. H. Jeong. Ashgate, Aldershot,

173–195.

Ury, W.L., 1995. ‘Conflict Resolution among the Bushmen:

Lessons in Dispute Systems Design’. Negotiation Journal

11(4), 379–389.

Walklate, S., 2003. ‘I Can’t Name any Names but What’s-

His-Face Up the Road will Sort it Out: Communities

and Conflict Resolution’. In Criminology,

Conflict Resolution and Restorative Justice, eds.

K. McEvoy and T. Newburn. Palgrave Macmillan,

London, 208–222.

Wehr, P., 1979. Conflict Regulation. Westview Special Studies

in Peace, Conflict, and Conflict Resolution. Westview

Press, Boulder, CO.

Xander, E., 1991. On Liberty: John Stuart Mill. Broadway

Press, Ontario.

96 Andreas Velthuizen

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Bro

ught

to y

ou b

y U

nisa

Lib

rary

] at

23:

49 2

2 Fe

brua

ry 2

015