Linking High Nature Value Grasslands to Small-Scale Farmer Incomes: Târnava Mare, Romania

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

6 -

download

0

Transcript of Linking High Nature Value Grasslands to Small-Scale Farmer Incomes: Târnava Mare, Romania

21/06/2012 17:57Linking High Nature Value Grasslands to Small-Scale Farmer Incomes: Târnava Mare, Romania

Page 1 of 20http://www.mountainhaymeadows.eu/online_publication/14-linking-hi…-value-grasslands-to-small-scale-farmer-incomes-tarnava-mare.html

Linking High Nature Value Grasslands to Small-Scale FarmerIncomes: Târnava Mare, Romania

Nat PAGE, Razvan POPA, Cristi GHERGHICEANU, Lenke BALINT

Fundatia ADEPT, Str. Principala nr. 166, Saschiz, Mures Romania RO [email protected], [email protected],[email protected], [email protected]

download pdf

KEYWORDS:

Romania, Transylvania, conservation, High Nature Value, grassland, biodiversity,wild flower meadows, organic farming, sustainable development, communityparticipation.

ABSTRACT

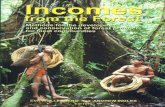

In the High Nature Value (HNV) grasslands of the Târnava Mare proposed site ofcommunity interest (SCI), in southern Transylvania, species-rich plant and animalcommunities thrive alongside traditional agriculture. The wildflower meadows areprobably the best that survive in lowland Europe. The designated area is about85,000 ha, with a population of about 25,000 people, 90% of whom are small-scale farmers. This landscape has evolved over centuries of traditionalmanagement, by small-scale farmers creating an ecological mosaic. Onlycontinued traditional management can maintain it. Economic and social benefitsfrom biodiversity conservation can provide a sustainable future for economicallythreatened small-scale farming communities.

It is hoped that recognition of the European importance of Romania’s semi-naturallandscapes, and the vital ecosystem services they provide, will lead to moretargeted policy measures to support the small-scale farming communitesassociated with them.

In 2005 Funda!ia ADEPT began an integrated programme of biodiversityconservation, agri-environment and rural development. Agri-environment, organicand Natura 2000 payments are all key policy elements. ADEPT is working at localand national levels to improve access to EU funding. Added to this, improvedmarketing of local food products, training schemes and schools education,diversification including development of new products and of ecotourism, canresult in real benefits for local people from protecting their landscape.

INTRODUCTION

Subsistence and semi-subsistence farming systems, certainly in Europe, areassociated with High Nature Value Farmed (HNVF) landscapes: semi-naturalgrasslands often in a mosaic of small plots intermixed with forests and arableland. When valuing HNVF landscapes, it is useful to estimate their value in abroad sense, using the concept of ecosystem services. Such areas are to bevalued as much for the public goods they produce, as for their economicagricultural productivity. Otherwise increased competitiveness will be givenpriority in landscapes without taking account of the broader social cost. Thebenefits of public goods (biodiversity conservation, water quality and security,food quality and security, cultural heritage, quality of life, recreation, carbonsequestration, fire and flood resistance, etc.) go beyond the communities that live

21/06/2012 17:57Linking High Nature Value Grasslands to Small-Scale Farmer Incomes: Târnava Mare, Romania

Page 2 of 20http://www.mountainhaymeadows.eu/online_publication/14-linking-hi…-value-grasslands-to-small-scale-farmer-incomes-tarnava-mare.html

within the areas that provide them.

What public goods do Romania’s HNV Farmed landscapes provide?

1. provisioning services

food – the majority of the area is under extensive subsistence or semi-subsistence type farming, and is thus an essential source of food (meat, dairyproducts, cereals, fruits and vegetables) for the local population. Wild foods suchas game, edible fruits and fungi are gathered in the region to eat or sell.

timber and fibre – the majority of houses are heated with wood, gathered fromlocal forests. Charcoal burning relies on local wood, supplying charcoal nationally.Timber is also still an essential building material, and although traditional craftssuch as carpentry and basket weaving are still present, these are in danger ofbeing lost. Wool from local sheep is used e.g. to provide an additional income forwomen in Viscri by making products to sell to tourists.

natural medicines and dyes etc. – Wild plants hold a valuable source ofbiochemicals and pharmaceuticals; today, use and knowledge about these plantsis decreasing as they are replaced by synthetic substances. However, a widerange of plants are still used medicinally: Greater Burdock (Arctium spp.), MarshMallow (Althaea officinalis), St John's-wort (Hypericum perforatum), Yarrow(Achillea millefolium), and Centaury (Centaurium erythraea).

genetic resources – the Saxon Villages region contains many wild relatives ofcommon crop plants (60 wild crop relatives occur in Transylvania – J. R. Akeroydpers. comm.).

2. regulating services - include essential functions such as maintenance ofnutrient and water cycles, carbon storage, pollination and pest regulation, soilerosion control and flood alleviation. Regulating services include:

biodiversity conservation. Semi-natural pastures and meadows (HNVgrasslands) represent a major part of European biodiversity. At a Europeanscale, these man-made landscapes offer a haven for significant biodiversity. Infact, the mosaic nature of small-scale farming landscapes often containsgreater species as well as habitat diversity. Wilderness areas have oftenreached a climax vegetation which is relatively uniform over large areas. Thefragmented ownership and management of small-scale farms creates acomplex mosaic which is very biodiversity-friendly. See Figure 1 below.

21/06/2012 17:57Linking High Nature Value Grasslands to Small-Scale Farmer Incomes: Târnava Mare, Romania

Page 3 of 20http://www.mountainhaymeadows.eu/online_publication/14-linking-hi…-value-grasslands-to-small-scale-farmer-incomes-tarnava-mare.html

Fig. 1: Mixed traditional agricultural landscapes in Europe have higher biodiversitythat wilderness areas

clean air and water for local, regional, national and international supply.Agricultural intensification will cause a loss of water quality as a result ofpollution from fertilisers, pesticides, manure or silage effluent. Downstreamcosts in water purification can be greater than the individual or nationalfinancial benefits of intensification.resistance to climate change: HNV landscapes associated with small-scalefarmers also provide large-scale habitats that allow species to adapt to climatechange. Conversely, these valuable habitats are threatened by some policyresponses to climate change, for example change of land use for bio-cropping.Reduction in CO! emissions. Small-scale farming communities areextremely energy-efficient and offer models for the reduction of CO2 emissionsand resulting global warming.carbon sequestration. Grassland habitat is a valuable carbon sink. Althoughwoodland sequesters large amounts of carbon above ground (c.6tonnes/ha/yr), grassland and woodland soils sequester similar amountsbelow ground (up to 140t/ha). Soil carbon is the 'premium sink' that weshould value the most, as woodland is usually managed and selectively felled,releasing large amounts back into the atmosphere.Extensively managed permanent grassland rich in wildlflower species hascarbon-rich soil. Many wildflower species are deep-rooted, especially in theabsence of fertiliser, and many species also have associated extensivenetworks of carbon-rich mycorrhizal fungi. Deep rooting and associatedseasonal root death helps to push carbon deep into the lower soil horizon.Ploughing of grassland, especially unimproved grassland and conversion toarable farming releases huge amounts of carbon into the atmosphere throughoxidation as well as releasing nitrates and suspended solids into watercourses. Arable soils without fallow periods tend to have low-carbon,mineralised soils and are ineffective in storing carbon (Smith et al., 1997).

21/06/2012 17:57Linking High Nature Value Grasslands to Small-Scale Farmer Incomes: Târnava Mare, Romania

Page 4 of 20http://www.mountainhaymeadows.eu/online_publication/14-linking-hi…-value-grasslands-to-small-scale-farmer-incomes-tarnava-mare.html

3. cultural and support services - recreation and tourism. Aesthetic/spiritualvalues are unrecognized and uncompensated side effects of conservation of theselandscapes. It is obviously important, socio-economically, that Romania offers her4 million small-scale farmers an economic future. Small-scale farmers can createa natural image and regional brand, offering commercial incentives tocommunities to manage their landscapes sustainably. Many communities, oftenassisted by NGOs, have successfully added value to and improved markets forlocal products by creating brands that link small producers with natural food. As amajor part of these commercial incentives, rural tourism will continue to developin rural areas, due to the unique landscapes, large semi-natural areas,hospitability of rural inhabitants, conservation of tradition, and the diversity ofrural tourist resources. This will act as a form of “payment” to local people forlandscape conservation. Local projects have been successful in working with localfarmers to develop a tourism-related economy - guest houses, food and crafts fortourists, nature guiding, etc.

The precise value of these environmental services is incalculable, althoughattempts at estimations are beginning to be made so that this factor may beincorporated into policy decision-making. The above explains the hidden, broader social value of HNVF landscapes and thesubsistence and semi-subsistence farm holdings that are essential for theirsurvival. These significant public goods suggest that we should give priority tosupporting them: the economic, social and environmental costs of losing them faroutweigh the costs of support.

ThreatsIn most rural villages in Romania, 90% of the population works in agriculture(Romania’s Rural Development Plan 2007, NRDP). Some do this as a secondincome, but these are very much the exception, and the main income tending tobe village schoolteacher, village mechanic/blacksmith etc. Most villages do nothave centres of employment within reach, especially in view of transportproblems.

These subsistence and semi-subsistence farmers face many problems including:1. Lack of markets for their goods, owing to cheap imports and tighter

regulations on informal sale of smallholder produce.2. Support measures to increase competitiveness or to diversify are not easily

accessible to them. The focus of NRDP investment measures is the 8% ofsemi-subsistence farms (over 2 ESU1 in economic turnover), not the 91% ofsubsistence farms under 2 ESU.

3. Hygiene regulations have damaged local small-scale food production byimposing unrealistic standards on small producers.

4. Small-scale farmers have no one lobbying for them, at national scale, and themany agencies with whom they need contact for assistance measures arepoorly coordinated and hard to access.

5. Economic migrations have led to a shortage of seasonal labour in villages:summer hand-mowing of hay meadows, for example.

6. Breakdown of the important common grazing system: until recently, grazingwas effectively managed by village grazing committees, with pasture/meadowboundaries and village boundaries honoured. This system is increasinglyabused and mayors do not have the power or incentive to take action.

7. Diversification of income is poorly developed because of lack of opportunities.The NRDP identifies a need to promote diversified employment, especially intourism. But lack of local tourist information centres to promote tourism atlocal level is holding back development.

The mosaic landscape management is one of the key elements of the HNVlandscape that is the provider of such significant public goods. Continuedtraditional management of the grasslands is essential to the survival of the area’sbiodiversity and continued provision of broader ecosystem services.

This paper describes a project in which the regeneration of rural economy and

21/06/2012 17:57Linking High Nature Value Grasslands to Small-Scale Farmer Incomes: Târnava Mare, Romania

Page 5 of 20http://www.mountainhaymeadows.eu/online_publication/14-linking-hi…-value-grasslands-to-small-scale-farmer-incomes-tarnava-mare.html

village prosperity is being used as the main tool for biodiversity conservation. Theprinciple being that we don’t support the grasslands, but the farmers whomaintain them.

Without support, these HNVF landscapes will disappear, as they have in much ofwestern Europe. Accession to the EU has intensified pressures on small-scalefarming: for example stricter food hygiene regulations and vulnerability tocompetitive imports. However, the EU also offers tools to support them.

The Târnava Mare areaThe Târnava Mare area is dominated by an astonishing seven EU HabitatsDirective Annex I grassland habitats, of which three are priority habitats; 10Habitats Directive Annex I forest habitats of which four are priority habitats. 23Habitats Directive Annex II plant and animal (especially butterfly) species havebeen identified, associated with these grassland habitats. These figures areremarkable at a European scale. The Târnava Mare area was designated a Natura 2000 site in 2008

SCI under the Habitats Directive, 85,000 ha (Figure1)SPA under the Birds Directive, 245,000 ha, mostly overlapping the SCI.

Why is the area’s biodiversity so important?Habitats:

The Târnava Mare pSCI still supports extensive stands of semi-natural vegetation,which is species-rich and, in the case of the woodlands, closely resembling thenatural habitats that occupied the Transylvanian foothills of the Carpathians priorto human impact. At the same time the region supports habitats that haveevolved in intimate association with human agriculture and other activities.Several of the habitats present, and individual species, are localized in distributionand highly characteristic of this part of Central Europe. It is a classic HighNature Value (HNV) farmed landscape, of considerable international value(Tables 1 and 2).

Fig. 1: Map of the Târnava Mare pSCI, in southern Transylvania, Romania.

Flora

Diverse and often pristine habitats support more than 1100 plant taxa, more than

21/06/2012 17:57Linking High Nature Value Grasslands to Small-Scale Farmer Incomes: Târnava Mare, Romania

Page 6 of 20http://www.mountainhaymeadows.eu/online_publication/14-linking-hi…-value-grasslands-to-small-scale-farmer-incomes-tarnava-mare.html

Diverse and often pristine habitats support more than 1100 plant taxa, more than30% of the Romanian flora. This richness is a result of geographical position,diversity of relief, varied climatic conditions and soils, and traditional land-usewith a mosaic of woodland, grassland and arable cultivation. Of these taxa, 87 arelisted for protection and conservation at national and international level, and 12taxa are threatened in Europe and are included in Annex II of the EU HabitatsDirective. A further 77 taxa are threatened at national level and included in theRomanian Red List. Just over half occur in meadow-steppe grasslandcommunities. Several are rare and decreasing in Europe. Some 60 native plantsare related to cultivated or crop plants and constitute a potential resource forplant breeding, notably distinctive variants of forage legumes such as Sainfoin(Onobrychis viciifolia) and Red Clover (Trifolium pratense) (J.R. Akeroyd pers.comm.). Some village fruit trees may represent old varieties or cultivars,especially plums and pears, and the wild pears too are a natural gene-pool.

Table 1: EU Habitats Directive Annex I habitat types present in the Târnava MarepSCI

Natura 2000Annex 1code

Description

40A0* Sub-continental Peripannonic scrub

9160 Sub-Atlantic & medio-European oak or oak-hornbeam forests ofCarpinion betulii

9170 Galio-Carpinetum oak-hornbeam forest

91Y0 Dacian oak-hornbeam forests

91E0* Alluvial forests with Alnus glutinosa and Fraxinus excelsior(Alno-Padion Alnion incanae Salicion albae)

92A0 Salix alba and Populus alba galleries

3150 Natural eutrophic lakes with Magnopotamion or Hydrocharition -type vegetation

3270 Rivers with muddy banks with Chenopodion rubri p.p. andBidention p.p. vegetation

62C0* Ponto-Sarmatic steppes

6210* Semi-natural dry grasslands and scrubland facies on calcareoussubstrates (Festuco-Brometalia) with important orchid sites

6240* Sub-pannonic steppic grasslands

6430 Hydrophilous tall herb fringe communities of plains and of themontane to alpine levels

6440 Alluvial meadows of river valleys of the Cnidion dubii class

6510 Lowland hay meadows (Alopecurus pratensis, Sanguisorbaofficinalis)

6520 Mountain hay meadows

* indicates priority habitats according to Annex I of Habitats Directive.

The most obvious manifestation of Transylvania’s astounding richness of plantand animal diversity is the wildflowers of the traditionally managed grasslands(Akeroyd 2002, 2006). These are probably the best lowland hay-meadows andpastures left in Europe; so extensive that you can walk through them for hours oreven days. The colourful and varied flora of these grasslands comprises a mixtureof western and central European plants, but with a significant element of steppicspecies. This species-rich ‘meadow-steppe’ has retreated throughout Europe,even in Poland, Czech Republic and Slovakia (Cerovsky 1995). Wiry grassesdominate the sward, and the species-rich communities often include 30-40

21/06/2012 17:57Linking High Nature Value Grasslands to Small-Scale Farmer Incomes: Târnava Mare, Romania

Page 7 of 20http://www.mountainhaymeadows.eu/online_publication/14-linking-hi…-value-grasslands-to-small-scale-farmer-incomes-tarnava-mare.html

species of legumes, notably Sainfoin (Onobrychis viciifolia), milk-vetches(Astralagus spp.), several dwarf brooms (Chamaecytisus and Genista spp.) andnumerous clovers (Trifolium spp.), a characteristic floristic element of drygrasslands in Transylvania (Pu"caru-Soroceanu 1963).

On hot, dry south-facing slopes, the flora is distinctly steppic, with Pontic-Sarmatian elements such as Adonis vernalis, Crambe tatarica, Linum flavum andSalvia nutans, and Mediterranean elements such as Muscari comosa and Vincaherbacea (Akeroyd 2007).

One of the most interesting and significant factors is the low nutrient status of thesoils (Jones 2008). Generations of villagers have transferred nutrients to thevalleys as hay or animal dung with almost no input of nutrients to the upperpastures. This correlates with the great species diversity, the richest grasslandcommunities (more than 40 species per 0.5 m2 relevé) being on medieval ‘ridgeand furrow’ fields along high slopes. In other parts of Europe, nutrient enrichmenthas done untold damage to similar ancient grasslands.

Fauna

The region’s animals associated with the diverse habitats and flora include the lastsignificant populations of wolf and brown bear in lowland Europe; a rich birdpopulation including rare species such as lesser-spotted eagle and corncrake; and1300 lepidoptera species including many rare and threatened taxa (Table 2).

Table 2: EU Habitats Directive Annex II species presentin the Târnava Mare pSCI

Group Species Group Species

Mammals Canis lupus * Insects Astacus astacus

Ursus arctos * Lucanus cervus

Lutra lutra Callimorpha quadripunctaria

Myotis myotis Eriogaster catax

Barbastella barbastellus Lycaena dispar

Maculinea teleius

Amphibians Triturus cristatus

Rana dalmatina Plants Echium russicum

Bombina variegata Crambe tataria Sebeok

Rana temporaria Cypripedium calceolus .

Pulsatilla pratensis ssp.hungarica *

Reptiles Lacerta agilis Arnica montana

Natrix natrix Gentiana lutea

Emys orbicularis Angelica palustris

Lycopodium clavatum

Fish Barbus meridionalispetenyi

Pulsatilla vulgaris subsp.grandis

Gobio albipinnatusvladikovy Adenophora liliifolia

Rhodeus sericeusamarus, Cephalaria radiata

Cobitis taenia taenia Salvia transsylvanica

Sabanejewia auratabalcanica

21/06/2012 17:57Linking High Nature Value Grasslands to Small-Scale Farmer Incomes: Târnava Mare, Romania

Page 8 of 20http://www.mountainhaymeadows.eu/online_publication/14-linking-hi…-value-grasslands-to-small-scale-farmer-incomes-tarnava-mare.html

Gobio uranoscopus frici

Gobio kessleri kessleri

To summarize the ecological and conservation importance of the habitats andspecies of the Târnava Mare pSCI:

The woodlands clearly derive from the original forests of the region, and theirground flora shelters plant and animal species and plant communities ofrestricted world distribution. Distinctive oak wood-pastures are a local feature.The grasslands and their biodiversity are of considerable importance at aEuropean level, and are particularly rich in Dacio-Pannonic, Pontic-Sarmatianand Mediterranean floristic elements. They represent a major resource of ahabitat that has contracted or disappeared over much of Europe throughagricultural intensification.Many of the wetlands, both floodplains and flushes, remain hydrologicallyintact, with a semi-natural zonation of habitats.The floristically rich habitats contain substantial populations of vertebrate andinvertebrate animals that are increasingly rare over much of Europe.The architecturally outstanding villages are an integral part of this landscape inintimate association with the rich biodiversity.These habitats provide biologists with a model of historical ecological patternsand processes and how these can maintain high levels of biodiversity.

Rarity on its own may not always be the best criterion for assessing conservationneeds and a holistic approach is required to protect such a sensitive and fragileecosystem (Akeroyd and Page 2006). The grasslands cannot be separated fromthe cultural landscape, of which they are a historical and integral element. Siteswith the rarest and most interesting plants, for example a steep grazed slope keptclear of scrub through burning and with Salvia nutans and Linum flavum (Jones2008), were poor in species (c.10 per relevé) but of inestimable ecological andconservation interest at a European level. Plant species diversity, althoughimportant in ecological terms, should not be considered in isolation as a measureof conservation value. Numbers of Red Data Book species or other threatenedplants (and animals) may not also be an accurate measure of the value of acommunity or habitat.

Throughout most of Europe, traditional grasslands have suffered drastic shifts inmanagement and are in a state of flux. This part of south-east Transylvaniarepresents a still functioning historic landscape, with the fauna, flora andcomplement of soil microorganisms of an intact ancient ecosystem, in whichextensive wildflower meadows still retain their role in agriculture. Such areas arerare in lowland Europe, and are therefore extremely valuable for conservationresearch and interpretation. They also are a cultural treasure.

Low-input grassland delivers a broad spectrum of environmental benefits:enhanced landscape quality, wildflower and wildlife conservation, protection ofarchaeological sites, protection of water-courses, reduction of soil erosion, andpublic amenity and education (Allen, 1995). Experiments have also shown thatfarm grassland can lock up carbon to a similar degree to farmland that has beenplanted with trees (Smith et al., 1997).

Threats to the flora and vegetationAlthough this ancient and special landscape remains substantially intact, thesurvival of its unique biodiversity depends upon maintenance of traditionalagricultural practices. These are threatened by the precarious state of the localagricultural economy and social structure. The lack of profitability in traditionalfarming methods and the emigration of most of the experienced farmingpopulation have created pressure to abandon marginal land and intensify farmingon readily accessible sites. The application of artificial fertilizers will seriouslydamage or destroy wildflower-rich hay-meadows, allowing coarse or vigorousgrasses and weeds to invade. Traditional manuring is not a problem, but even asingle application of chemical fertilizer would undoubtedly have catastrophic

21/06/2012 17:57Linking High Nature Value Grasslands to Small-Scale Farmer Incomes: Târnava Mare, Romania

Page 9 of 20http://www.mountainhaymeadows.eu/online_publication/14-linking-hi…-value-grasslands-to-small-scale-farmer-incomes-tarnava-mare.html

effects on the survival of the most species-rich grasslands. Woodlands aregenerally well-managed, but changes in ownership have created pressures forquick profits, and some localized abusive felling.

Research by ADEPT (Akeroyd & Page 2006; Jones 2008; and Akeroyd, Jones,unpublished) has identified a number of substantial threats to biodiversity.Unchecked, these factors will lead to loss of biodiversity, and will contribute topoverty and hardship for local people.

The principal threats to the wild plants and vegetation of the region are:reduction of livestock numbers leading to abandonment or reduction oftraditional grassland management such as common grazing and scrubclearance;Uncontrolled agricultural expansion into grasslands, with nutrient over-enrichment and over-grazing, especially by sheep, and invasion by a ruderalflora of unpalatable species such as thistles and other invasive weeds;Unsustainable forestry practices such as planting with exotics or clear-felling;

Secondary threats are:Unsuitable and unsustainable infrastructure development for recreation andtourism, with new roads and buildings;Unsustainable exploitation of wild populations of plants, especially over-collection of medicinal plants;Lack of public knowledge and information about the region’s ecological value,and the potential economic value of the natural landscape (e.g. EU incentivesto conserve biodiversity, and market potential of natural image);Further spread of weeds, especially aggressive aliens such as JapaneseKnotweed (Fallopia japonica var. japonica);Climate change, for example an increase in frequency and duration ofprolonged spring and summer drought.

Collapse of cow numbers is the largest and most immediate threat to thislandscape.

The key economic sector is the owners with fewer than five cows. See Table 3,indicating trends in numbers, and Table 4, showing low average herd size; over55% of applicants for payments have fewer than 5 cows:

Table 3: Number of cows in the 8 communes of Tarnava Mare area

CommuneYear/Cow numbers registered in Town Halls

2008 2009

Bunesti 1764 1450

Saschiz 602 420

Vanatori 520 377

Danes 740 500

Apold 623 550

Albesti 600 422

Laslea 1647 1077

Biertan 430 374

Table 4: Applications for land payments and agri-environment payments analysedby number of cows owned

Cownumbers Bunesti Saschiz Vanatori Danes Apold Albesti Laslea Biertan Total

#5 69 33 30 33 48 20 67 17 317

21/06/2012 17:57Linking High Nature Value Grasslands to Small-Scale Farmer Incomes: Târnava Mare, Romania

Page 10 of 20http://www.mountainhaymeadows.eu/online_publication/14-linking-hi…value-grasslands-to-small-scale-farmer-incomes-tarnava-mare.html

5-10 31 6 5 8 12 13 40 8 123

10-50 26 9 9 7 13 13 37 5 119

50-100 2 1 0 3 1 0 3 3 13

>100 0 1 1 1 0 0 1 0 4

Total: 128 50 45 52 74 46 148 33 576

ADEPT project in the Târnava Mare areaThe NGO Funda!ia ADEPT (Agricultural Development & Environmental Protectionin Transylvania) has been active in Romania since 2003. It has cooperated closelywith the Romanian Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MARD), andMinistry of Environment and Forests. Its vision is to achieve biodiversityconservation at a landscape scale not primarily by creating protected areas, butby working with small-scale farmers to create incentives to conserve the semi-natural landscapes they have created.

ADEPT is focusing on an 85.000 ha area, Târnava Mare, a semi-natural landscapeof remarkable biodiversity. It has recently been designated a Natura 2000 siteboth under the Birds Directive and the Habitats Directive. But this designationalone will not conserve the area for its biodiversity and broader public goodsbenefits. Only local small-scale farmers can conserve the landscape, an objectivewhich can be achieved primarily through the National Rural Development Plan.

Table 5: applications for registration of dairy cattle farms in terms of herd size(APIA, 2009)

Herd size Com.Bunesti

Com.Vanatori

Com.Danes

Com.Albesti

Com.Laslea

Com.Biertan Total

#5 69 30 33 20 67 17 236

5-10 31 5 8 13 40 8 105

10-50 26 9 7 13 37 5 97

50-100 2 0 3 0 3 3 11

>100 0 1 1 0 1 0 3

Total 128 45 52 46 148 33 452

In the Târnava Mare area, 52% of registered holdings (those of more than 1 ha)have fewer than 5 cows. If holdings smaller than 1 ha were included, this figurewould be around 90%. Similarly, the average holding size of farmers who haveapplied for agri-environment payments in the Târnava Mare area is 8.2ha(source: APIA), a figure which also excludes all holdings under 1 ha. (See Table5)

1: Agri-environment payments

Romania has designated eligible areas for its grassland agri-environmentpayments on an assessment of HNV grassland distribution in Romania – seeFigures 1 and 2 below. This is an effective way of targeting support towards theHNVF landscapes which provide public goods, and is to be applauded.

In 2005-6, ADEPT carried out a pilot agri-environment programme in closecooperation with the Romanian Ministry of Agriculture & Rural Development(MARD). These were the only grassland agri-environment agreements in Romaniaat the time. SAPARD 3.3 revealed a number of design problems that impededsmall-farmer access: complexity of forms to be completed electronically,complexity of supporting documents required, need for repeated visits to theregional capital to deposit the forms, etc. Under the pilot measure, ADEPTemployed 3 staff members full-time for 6 months to promote the scheme and tohelp farmers complete and deliver the forms, in 6 out of the 8 communes of the

21/06/2012 17:57Linking High Nature Value Grasslands to Small-Scale Farmer Incomes: Târnava Mare, Romania

Page 11 of 20http://www.mountainhaymeadows.eu/online_publication/14-linking-hi…value-grasslands-to-small-scale-farmer-incomes-tarnava-mare.html

Târnava Mare area. This proved to be very effective: 97 farmers and 1,980 haentered the pilot agri-environment scheme SAPARD 3.3. The ADEPT FarmAdvisory Service (FAS) was also effective in raising longer-term awareness in thearea of the benefits to small farmers of the agri-environment scheme.

MARD responded to lessons learned under the pilot project by simplifying theapplication process for the equivalent grassland agri-environment measurelaunched in 2008, Measure 214. This helped take-up of the measure in the projectarea, much higher than for SAPARD 3.3 (see Table 6).

Table 6: overall take-up of SAPARD 3.3 and Measure 214 in Târnava Mare area

Târnava Mare area

No. participants inSAPARD 3.3 (2006)

Area coveredby SAPARD 3.3

No. participants inMeasure 214 (2008)

Area covered byMeasure 214

97 1980 967 7940.48

Also, as a result of ADEPT’s farm advisory actions, participation of Târnava Marearea farmers in Measure 214 was 6.6 times the national average, in terms ofnumber of participants, and 3.8 times national average in terms of area. It issignificant that a larger number of smaller-scale farmers participated (as shownby average size of applications) as a result of farm advisory actions. See Table 7.

Table 7: comparative take-up of Measure 214 in communes in which FAS wasactive, compared to other communes in Mures county, 2009 (data from APIA,

Romanian payments agency)

Mures countyNr. ofparticipants inMeasure 214

Area coveredby Measure214

Av. size ofapplication

Av. per commune in the 5 FAScommunes in Mures county 200.6 2020.8 ha 10.07 ha

Av. per commune for the 45other eligible communes inMures

30.4 537.6 ha 17.68 ha

Impact: in the eight communes of the area, 1.390 small farmers on 17,641 haare receiving a total of over $2.5 m/year through access to agri-environmentschemes. Expected figure without FAS support would be $658,000. Positiveimpact on conservation management of land under agri-environment grants canbe seen already; this applies especially to scrub clearance, which is being carriedout by land-owners in order to pass inspections by the national inspection agencyAPIA.

2. Supporting common grazing through agri-environment payments

Common grazing is an important element of traditional land management inTransylvania, and continued common grazing is essential to the survival of small-scale dairy producers in the region. However, continued common grazing isthreatened by breakdown of the discipline and owner contributions of free labourto maintain common land (scrub clearance etc.) and by the fact that such accessto agri-environment payments is a problem. Applicants need to own, or have a 5-year lease, of such lands to be eligible. In Seica Mare, a village 50 km west of Sighisoara, imaginative measures havebeen adopted locally in order to give the common land users access to RDP Axis 2Measure 214 agri-environment payments. The Seica Mare project has enabled around 100ha of communal grazing landnormally managed through the Town Hall to be leased for 5 years by the villagegrazing association unlocking access to agri-environment payments. The grazingassociation has agreed to maintain the land properly which has secured the future

21/06/2012 17:57Linking High Nature Value Grasslands to Small-Scale Farmer Incomes: Târnava Mare, Romania

Page 12 of 20http://www.mountainhaymeadows.eu/online_publication/14-linking-hi…value-grasslands-to-small-scale-farmer-incomes-tarnava-mare.html

association has agreed to maintain the land properly which has secured the future

of 27 cattle, sheep and goat farmers while preserving the habitats and landscape.

Impact: 1,000 ha under lease to the grazing association, giving $180,000/year tothe 27 cattle, sheep and goat farmers, which they will invest in common projectsincluding a milk collection and processing unit, and a village abattoir which willadd value to local agricultural projects and create further employment.

3: Dairy sector

Small-scale dairy production is key to the survival of the HNV landscapes ofRomania. Over 50% of registered producers (that is, excluding those with under1ha of land) have fewer than 5 cows. Over 75% of registered producers haveunder 10 cows. The small-scale farmers, who have created these landscapes,depend mainly on dairy cow or ewe products for their income. Small producers alldeliver to one or two milk collection points in villages, from which the processorstake delivery. These communal milk collection points have quality problems, sincesome farmers are less careful than others.

In the Târnava Mare area, as in all of Transylvania, there is a collapse in themarket for milk and therefore a collapse in cow numbers. Without a market, agri-environment payments alone are obviously not sufficient to halt this collapse.Surveys show a reduction of cow numbers of 25% in the last year alone, 2008-2009. Total number of cattle in the 6 communes of Târnava Mare area for whichwe have figures was 5701 in 2008, but fell to 4200 in 2009. See Table 3. Thiscould be disastrous for traditional land management, especially for the survival ofthe area’s traditional wildflower-rich hay meadows.

The cause of the loss of market is that small farmers cannot guarantee the qualityand quantity necessary to attract the milk processors. Although EU-standard milkhygiene is not obligatory in Romania until January 2011, milk processors arealready using these standards as a commercial yard-stick. They can import goodquality milk, in convenient large quantities, at a competitive price, fromneighbouring countries such as Hungary. Villages have been left without any milkcollection by processors. Village producers are generally unable to organise acombined response to solve the problemIn 2009, milk processors stopped collecting milk from many of these community-use milk collection points, since milk quality and quantity was not sufficient. Theprocessors can import good quality milk, in convenient large quantities, at acompetitive price, from neighbouring countries such as Hungary. Suddenly therewas no market for milk, threatening the economic survival of these communities.Many villages were left without any milk collection by processors, and the small-scale dairy farmers were unable to solve the problem.

This threatens the very survival of small-scale milk producers in the HNV areas ofRomania.

ADEPT responded by helping three villages (Saschiz, Daia, Danes) to improvetheir milk collection points, as well as other actions to improve hygiene, and toimprove discipline at the communal milk collection points, through workshopswith farmers, discussions with village dairy associations, on-the-spot testing andnaming-and-shaming of poor-quality producers (by posting up daily test results),and negotiations with processors to complete the link to the buyers. See Figure 2.

Impact: within 6 months, three villages have had their milk collection reinstated,giving $5.000/month monthly turnover again to 35 small-scale farmers pervillage, and reversing the fall in cow numbers. (See Table 8)

21/06/2012 17:57Linking High Nature Value Grasslands to Small-Scale Farmer Incomes: Târnava Mare, Romania

Page 13 of 20http://www.mountainhaymeadows.eu/online_publication/14-linking-hi…value-grasslands-to-small-scale-farmer-incomes-tarnava-mare.html

Fig 2: milk hygiene training brochure used in small-scale farmer workshops

Table 8: ADEPT Milk collection point in Daia Village

Cost of new milkcollection point

No. offarmers

No. ofcows

litres ofmilk/day

Euros/litre

Initial monthlyturnover

$12.000 25 78 725 l. $0.23 $5.000

In the villages with new milk collection points, the number of cows and number ofowners supplying the points are already rising now that a profit motive has beenrestored. Therefore the turnover and profitability of the milk collection points arealso expected to increase.

21/06/2012 17:57Linking High Nature Value Grasslands to Small-Scale Farmer Incomes: Târnava Mare, Romania

Page 14 of 20http://www.mountainhaymeadows.eu/online_publication/14-linking-hi…value-grasslands-to-small-scale-farmer-incomes-tarnava-mare.html

also expected to increase.

4. Adding value to agricultural products

In 2005 ADEPT began a processing and marketing programme in the TârnavaMare area. This shows how branded local products can evolve with effectivemarketing.

First, ADEPT identified 20 producers of cheese, jam and pickles who wereinterested in participating in a marketing exercise. ADEPT wrote productionprotocols and trained producers to follow these and maintain consistent qualityand hygiene standards.

ADEPT also developed a local brand and labeling (see Fig 3).

Fig 3: examples of branding and packaging for local marketing.

Sales and associated skills have now increased to a point where the original 20producers travel to farmers markets without assistance from ADEPT (oftensharing transport at their own initiative). See Table 9.

The producers are now commercially sustainable, and ADEPT is encouraging morefarmers and farmers wives to join the informal producer group, the Târnava MareProducers Association. Once the first producers clearly derived useful profit,others asked to be included. This in general is the case: talking about potentialbenefits is met with scepticism: demonstration of profit elicits immediateparticipation from others.

Table 9: trends in sales, Târnava Mare Producers Association

Year Value of direct sales (cheese, jam,pickles, baskets)

Value of sales thro’ TouristInformation Center

2005 - -

2006 $3600 -

2007 $15900 $2500

2008 $75000 $8500

2009 $31500 $12161

ADEPT also developed farmers markets (only the producers themselves arepermitted to sell at these markets). Transport was paid for initially, but thissupport is no longer necessary. ADEPT also offered them the opportunity to selljams and pickles in the tourist information centre. The “Saschiz Jams”, unknownin 2005, are now sought after in farmers markets in several Romanian cities.

ADEPT led the establishment of Targul Taranului Roman in Bucharest in 2007 andthe Targul Roadele Pamantului in Brasov in 2009, which are both highly succesful.We are now developing other markets nearer the project area: see Table 10.

Table 10: development of farmers’ markets, Târnava Mare Producers Association

No. of Estimated Revenue

21/06/2012 17:57Linking High Nature Value Grasslands to Small-Scale Farmer Incomes: Târnava Mare, Romania

Page 15 of 20http://www.mountainhaymeadows.eu/online_publication/14-linking-hi…value-grasslands-to-small-scale-farmer-incomes-tarnava-mare.html

Location Established Frequency No. of

producers

Estimated

people/event

Revenue

/eventProducts

Sighisoara Dec 09 andMar 2010 quarterly 15- 20 700-1000 $4-5.000 Meat/oils/preserves/

cheese/bakery/pickles

Medias May 2010 first one ofits kind 25-30 1000-1500 $8-

10.000Mostly cheese, plusother products

Sibiu July 2010 first one ofits kind 15-20 4000-5000 $8-

10.000Meat/oils/preserves/cheese/bakery/pickles

ADEPT is getting increasing demand for organizing and promoting these events.ADEPT is also creating links between producers and major hotels in nearby cities.

Impact: $43,661 extra income in 2009 for 25 producers (jam and cheese), indirect sales by producers mainly at farmers markets facilitated by ADEPT, andsales through the Tourist Information Centre established by ADEPT. 15 trainedwomen involved in jam-making in the summer months. Over 100 Romaseasonally employed.

5. Helping to solve food hygiene threat to small-scale producers

The sale of these products in farmers markets was threatened by inconsistentinterpretation of EU hygiene regulations, especially those relating to authorisationof premises for small-scale production and of points of sale (especially farm-gatedirect sales).

ADEPT and NGO partners WWF and Milvus have worked closely with the statefood hygiene agency ANSVSA to clarify that a flexible approach should be appliedto direct sales by small-scale producers in marginal areas: so long as food safetyis retained, traditional production methods should often be allowed to continue.This message was published in a booklet supported by EU Delegation funds, in2007, in order not only to reassure small producers, but also, equally importantly,so that local (DSVSA) representatives of ANSVSA receive clear signals fromBucharest that this is an approved approach. See Fig 4.

We are pleased to say that farmers markets selling local/traditional products arenow becoming a feature in major Romanian cities this would not have occurredwithout active MADR and ANSVSA support.

These kinds of activities are eligible for support under various NRDP measures,such as Measure 123 Adding value to agricultural and forestry products (although50% co-financing is a problem for small producers), and 142 Setting up ofproducer groups (although thresholds are too high to help small groups in initialstages).

Fig 4: booklet on food hygiene for small producers, available freely in Hungarian,Romanian and English.

6: Development of agro-tourism in Târnava Mare area

21/06/2012 17:57Linking High Nature Value Grasslands to Small-Scale Farmer Incomes: Târnava Mare, Romania

Page 16 of 20http://www.mountainhaymeadows.eu/online_publication/14-linking-hi…value-grasslands-to-small-scale-farmer-incomes-tarnava-mare.html

6: Development of agro-tourism in Târnava Mare area

ADEPT has also promoted diversification in the Târnava Mare area, which haswitnessed an extraordinary growth in the number of visitors, according to recordstaken by the Tourist Information Centre that was opened by a ADEPT inpartnership with the Town Hall. Of the visitors, 60% were foreign, 40%Romanian. (See Table 11.)

This growth in numbers has occurred in spite of a fall nationally and globally in2009 as a result of the financial crisis. The tourists are attracted by a varied offerof cultural and nature-watching pursuits developed by the NGO: guest houses,meeting producers, guided nature walks, etc.

Table 11: trends in Târnava Mare tourism income

Year Tourism (accommodation, meals,activities, guiding)

No. of tourists,Târnava Mare

2005 - -

2006 $15000 350

2007 $25000 2120

2008 $38000 5970

2009 $62457 6328

Impact: $62,000 extra income in 2009 to 30 guest house owners and serviceproviders.

ADEPT achieved this growth of numbers by carrying out a number of agro-tourismtraining courses, very practical in their content including basic English andexplanation of visitor expectations. For example, potential guest house hosts wereoften concerned by lack of television and of supermarket food, quite opposite tothe concerns of guests whose main concerns were cleanliness and some degree ofprivacy – requiring little investment. Perceived barriers were removed by suchexplanations.

Similar to the jam development experience, the initiative came from ADEPT, butonce a small number had derived an income, ADEPT has received manyspontaneous demands to become involved.

This diversification could be funded under 313 Encouragement of tourismactivities, although lack of confidence and of co-financing are barriers to small-scale farmers wishing to diversify.

7. LEADER

ADEPT has recognised LEADER as highly relevant to smallholder communities, andhas promoted the establishment of the Târnava Mare Local Action Group (LAG).This is already operational, although Axis 4 funding for LAGs has not yet started.As a result, small-scale farmers are participating in LEADER-type meetings, whichhelps ADEPT and others understand local concerns and priorities.

ADEPT has deliberately proposed the Târnava Mare LAG to cover the same areaand include the same communes as the Târnava Mare Natura 2000 area, sincethese two measures (one for local involvement in sustainable rural development,and the other for biodiversity conservation) will assist each other in an innovativeway. See Figures 3 and 4 below. The LAG will become a very useful tool to involvelocal people in the management of the Natura 2000 site.

The LEADER process will be used increasingly in guiding local rural developmentpolicies. Once Axis 4 funding starts, small-scale farmers will contribute directly toencouragement and initiation of local development actions, including newproducts and marketing systems, modernizing the traditional activities byapplying new technologies, etc.

21/06/2012 17:57Linking High Nature Value Grasslands to Small-Scale Farmer Incomes: Târnava Mare, Romania

Page 17 of 20http://www.mountainhaymeadows.eu/online_publication/14-linking-hi…value-grasslands-to-small-scale-farmer-incomes-tarnava-mare.html

An example of new technologies relevant to village needs is the Public AccessInformation Points (PAPI) initiative referred to above. There are 2 in the 8communes of the Târnava Mare area. Use is free, and assistance is available, foraccess to funding projects, internet banking etc., and there is a small charge forpersonal use. Although to begin with (2008) the PAPI was used mainly byyounger villagers, it is noticeable now that many middle-aged villagers are usingthe PAPI for access to banking, downloading of forms etc., especially for NRDP-related IACS maps and grant claim forms. PAPI is a World Bank project, but thesystem could be eligible for NRDP support, for example under Measure 322 Villagerenewal and development / basic services for rural economy.

8. Natura 2000

ADEPT led the process of designation of the Târnava Mare area as a Natura 2000site, which took place in 2008. Under NRDP Measure 213, holdings within Natura2000 sites will receive additional payments. These payments will not start inRomania until sites have management plans with obligatory measures, and thecosts of these obligatory measures can be calculated.

Natura 2000 plays an important role as the EU’s flagship for biodiversityconservation, but it is important to take into account that public goods includingbiodiversity are derived to a large extent from semi-natural agriculturallandscapes outside conventional Natura 2000 sites. Significant opportunities tosecure biodiversity conservation and other public goods will be lost if theprotection of semi-natural landscapes is ignored in favour of Natura sites. TheHNV concept argues that high biodiversity should be recognised and protected bylooser, more flexible tools than targeting areas with strict boundaries and formaldesignation: tools such as agri-environment payments. This is the area of overlapof DG Agriculture and DG Environment. The more closely they work together inpolicy development, the better.

These examples illustrate thatsmall-scale farmers suffer practical problems in applying for agri-environmentschemes. This applies to other area-based and investment schemes alsosmall-scale farmers will not take the initiative to solve practical problems tomeet quality and other commercial standards – they generally have a fatalisticand passive approachsuch problems in these rural areas can be solved by integrated planning byqualified advisorssmall-scale farmers respond to advisory services where they are availableresults achieved appear, according to examples cited, to be commerciallyviable and therefore offer long-term solutions to the problem of small-scalecommunity sustainability.

CONCLUSIONS

The Romanian Government understandably sees the need to increasecompetitiveness in the agricultural sector, because EU membership will increaseexposure to competition from lower-cost and better-established producers inWestern Europe. However, in parallel, the Public Goods approach to policyanalysis suggests that more action may be justified to support the continuedtraditional activities of Romania’s approximately 4 million small-scale farmers,rather than thinking of them simply as a sector to be restructured. Thesetraditional management systems are important for delivering a whole range ofvital public goods – water quality, flood prevention, resistance to effects ofclimate change, water and food security – which have a large economic value.The EU has tools in the NRDP the support these HNVF landscapes andcommunities: however, there are barriers to access in policy design anddelivery.

Policy design: the target of NRDP Pillar II Axis 1 is the 8% of SSF holdings 2-8ESU in size, not the 91% of SF holdings under 2 ESU. And measure 112, Settingup of young farmers, has a minimum threshold of 6 ESU, which is a barrier toyoung farmers. The target of NRDP Axis 2, and Pillar I area payments, is the 54%

21/06/2012 17:57Linking High Nature Value Grasslands to Small-Scale Farmer Incomes: Târnava Mare, Romania

Page 18 of 20http://www.mountainhaymeadows.eu/online_publication/14-linking-hi…value-grasslands-to-small-scale-farmer-incomes-tarnava-mare.html

young farmers. The target of NRDP Axis 2, and Pillar I area payments, is the 54%

of holdings over 1ha in size, not the 45% of holdings under 1 ha2. In othermember states thresholds are lower for receiving these payments.

Could eligibility for be enlarged in Romania? This would present administrativechallenges – for example, aid secured by a farm applying for say 0.5ha underagri-environment may be disproportionate to the administrative cost to deliver &control such support, and there would also be the additional administrativeburden of a huge increase in the number of eligible beneficiaries. But, when widereconomic, social and cultural benefits are taken into account, in terms of publicgoods, this might be considered justified.

Delivery: this case study suggests that improvements in consultancy services willdeliver much improved results on the ground, in terms of uptake by farmers. Thestudy also shows that if the range of NRDP support measures is combined in aninnovative way, it can be very effective in supporting small-scale farmingcommunities. The challenge is to broaden such activity from localised, patchyimplementation to wider, national-level implementation. For this, highly trainedand motivated advisory services are required.

Romanian subsistence and semi-subsistence farmers will rely on good advisoryservices for many more years owing to their unfamiliarity with the process ofgrant applications. However, state agriculture advisory services are patchy, insome areas ineffective. State advisory and inspection services often lack trainingand basic equipment, such as vehicles to allow farm visits; such capacity isrequired to improve uptake of measures, and to improve the impact of measuresthrough proper inspections.

This case study also shows that the role of NGOs can be significant, by helpinggovernment agencies to deliver policy in a very cost-effective manner, and byproviding feedback from farmers to guide modification of NRDP measures wheresuitable. Perhaps the potential role of NGOs could be given greater policyrecognition and financial support, for example by expanding and making moreflexible NRDP Measure 143 (Providing farm advisory and extension services), sothat local/regional NGOs can gain access to funding for such a role.

The ADEPT project works in a semi-natural landscape of European biodiversityimportance, in which conservation of the area depends not only on communitysupport, but also on active community participation in the form of continuedtraditional management of the landscape. Without community participation thearea cannot be conserved; conservation practitioners can never replicateartificially the mowing, grazing and general management of tens of thousands ofhectares of mosaic landscape.

Under these circumstances, the community must rediscover commercial andmoral incentives to continue to manage the area traditionally. The role ofscientists and conservation NGOs is, in this case, to help local people tounderstand the importance of the landscape in which they live, and to encouragethem to take an interest in why it works as an ecosystem, and to help give themthe capacity, and long-term economic incentives, to continue to conserve itthemselves.

The importance of the area from a biodiversity point of view is clear. The inclusionof the Târnava Mare area within the EU’s Natura 2000 network offers perhaps thebest means to protect the landscape in the face of economic and social pressures,especially since Natura 2000 will take into account the interests of local people,and make them eligible for special grants and funding.

But it is also clear that this is not a wilderness conservation project, butessentially an agri-environmental one. We are seeking prosperous small-scalefarming communities in sustainable and diversified rural economies. Local peopleare therefore at the heart of these processes. They created this landscape, andonly their continued management can preserve it.

21/06/2012 17:57Linking High Nature Value Grasslands to Small-Scale Farmer Incomes: Târnava Mare, Romania

Page 19 of 20http://www.mountainhaymeadows.eu/online_publication/14-linking-hi…value-grasslands-to-small-scale-farmer-incomes-tarnava-mare.html

In the project, all methods are being explored by which the biodiversityimportance of the landscape can be given a market value, which would bring localbenefits and therefore create positive, long-term, market incentives forconservation.

EU payments for habitat and species conservation (under Natura 2000) and foragri-environment (HNV grassland management payments) are not a long-termsolution, but they do give time and financial opportunity to establish thoseessential long-term commercial incentives.

Adding value to food and other local products, through area branding and throughquality/organic certification and branding, are key to this longer term process.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our thanks to the following:Orange Romania and the Norwegian Government’s Innovation Norway fund forsponsoring this aspect of the ADEPT project;the Romanian Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development for their excellentsupport and cooperation;ADEPT staff colleagues especially Dr John Akeroyd, Ben Mehedin and CornelStanciu for their energy and dedication which has made the project successful;

last but not least the many local people who have supported ADEPT with suchenthusiasm, without whom we could do nothing.

REFERENCES

Akeroyd, J.[R.] (2002) Protecting Romania’s Lost World. Plant Talk, 30: 19–24.

Akeroyd, J. [R.] (2006) The historic countryside of the Saxon Villages of southernTransylvania. Fundatia ADEPT, Saschiz, Romania. pp. 86.

Akeroyd, J.R. (2007) The floral riches of southern Transylvania. The Plantsman,NS, 6: 152–156.

Akeroyd, J.R. & Page, N. (2006) The Saxon Villages of southern Transylvania:conserving biodiversity in an historic landscape. In Gafta, D. & Akeroyd, J.(R.),eds (2006) Nature Conservation: Concepts and Practice, pp. 199–210. SpringerVerlag, Heidelburg, Germany.

Allen, T.D. (1995) Environmental benefits from grassland farming. In Pollott, G.E.(ed.) Grassland in the 21st century, pp.135–142. British Grassland Society.

Cerovsky, J. (1995) Endangered plants. London: Sunburst Books.

Jones, A. (2008) The challenge of High Nature Value grasslands conservation inTransylvania. Transylvanian Review of Systematical and Ecological Research, 4:73–81.

Mountford, J. O. and Akeroyd, J.R. (2009) Village grasslands of Romania – anundervalued conservation resource. In Ivanova, D. (ed.), Plant, fungal and habitatdiversity investigation and conservation. Proceedings of IV Balkan BotanicalCongress, Sofia, 20–26 June 2006, pp. 523–529. Institute of Botany, Sofia.

Puscaru-Soroceanu, E. (ed.) et al. (1963) Pasuni si fînetele din Republica PopularaRomîna. Academiei Republicii Populare Romîna, Bucure"ti.

Smith, P., Powlson, D., Glendining, M. & Smith, J. (1997) Potential for carbonsequestration in European soils: preliminary estimates for five scenarios usingresults from long-term experiments. Global Change Biology, 3: 67–79.

1 The economic size of farms in the EU is defined as Economic Size Units (ESU), where 1 ESU =an annual turnover of approximately 1,200 EUR

2 It is worth noting that land in holdings under 1 ha can be eligible for SAPS payments since theapplicant for SAPS is not the owner, but the user of the land. If a farmer uses several parcels from

21/06/2012 17:57Linking High Nature Value Grasslands to Small-Scale Farmer Incomes: Târnava Mare, Romania

Page 20 of 20http://www.mountainhaymeadows.eu/online_publication/14-linking-hi…value-grasslands-to-small-scale-farmer-incomes-tarnava-mare.html

applicant for SAPS is not the owner, but the user of the land. If a farmer uses several parcels from

several owners, and is using at least 1ha in total, he/she can claim SAPS even if individualownership of the parcels of the land he is using is under 1 ha.

Mountain hay meadows: hotspots of biodiversity and traditional culture, Ed.Barbara Knowles, Society of Biology, London. ©Pogány-havas Association 2011.