Leveraging Digital Technologies for Effective Risk ... - Criticaleye

Legitimacy, competence and social capital: leveraging personal and structural resources in women-led...

-

Upload

independent -

Category

Documents

-

view

3 -

download

0

Transcript of Legitimacy, competence and social capital: leveraging personal and structural resources in women-led...

1

LEGITIMACY, COMPETENCE, AND SOCIAL CAPITAL:

LEVERAGING PERSONAL AND STRUCTURAL RESOURCES IN WOMEN-LED

SMEs IN RUSSIA

Tatiana Iakovleva1 and Jill Kickul23

Erin McFee

Whereas contemporary research demonstrates that women entrepreneurs across the world

recognize precursors of growth and the importance of activities such as information seeking and

planning in strategic leadership roles, our study contributes to the literature by investigating the

influence of a comparatively more diverse set of factors. These go beyond industry type to target

critical elements directly supporting the needs, development, and growth of women business

owners. Additionally and more importantly, while there are a number of studies, identifying

women SME success factors have been carried out in advanced countries (Anna et al., 1999;

Chaganti and Parasuraman, 1997; Lerner and Almor, 2002), economic research on

entrepreneurship in transition economies is less developed and only a few studies have used a

rigorous scientific approach (Tkachev and Kolvereid, 1999). The lack of information on female

entrepreneurs is especially apparent. According to Ylinempåå and Chechurina (2000), Russian

women have limited options to achieve a leading position in industry, politics or other spheres of

social production. Those limitations serve as “push” factors for women to enter the

entrepreneurial sector, where starting new, smaller firms serves the double purpose of both

generating additional family income, and creating an arena for self-fulfilment. The purpose of

1 doctoral student and research fellow of Bode Graduate School of Business, 8049 Bode, Norwaye-mail:[email protected], tel. +4797626214, (corresponding author)2 Elizabeth J. McCandless Professor of Entrepreneurship, Simmons School of Management 409 Commonwealth Avenue Boston,MA 02215 Telephone: 617-521-3877 Fax: 617-521-3880 [email protected] Erin McFee is a graduate student at Simmons School of Management, [email protected].

2

this study is to add new theoretical and empirical insights on small women-owned-and-run firm’s

factors currently operating within the turbulent Russian economy, and to identify what factors

contribute most substantially to the superior performance and growth of women-owned

businesses. We address this issue of factors affecting growth and expansion by targeting

individual style (e.g., entrepreneurial intensity, perceptions of self and competence levels) as

well as tangible and intangible capital resources (e.g., social and financial).

Our study utilizes signaling theory (Deeds et al., 1997, Stuart et al., 1999, Higgins &

Gulati, 2000) as a conceptual framework to examine women-led venture outcomes such as

funding success, net worth, and business longevity. The signaling content of social capital and

relationships is expected to impact how women perceive themselves and their own assessments

of legitimacy by others. Our study provides a relevant test of theory positing that legitimacy is

contingent on degree of conformity to social norms, values, and expectations (Dowling &

Pfeffer, 1975). It will highlight how legitimacy, as a resource, enhances the odds of survival of

emerging women-run firms (Aldrich & Fiol, 1995; Rao, 1994; Singh, Tucker & Meinhard, 1991;

Suchman, 1995) and attracts resource transactions over sustained periods of time.

Signaling theory describes the leveraging and utilization of social capital to enhance

entrepreneurial ability to assemble financial resources at informal (e.g., friends, family) and

formal (e.g., venture capitalists, banks) levels. The ability to garner these resources is expected

to have an influence on venture net worth, growth, and sustainability. Additionally, it has been

suggested that social capital and legitimacy provide emotional support for entrepreneurial risk

taking (e.g., Bruderl & Preisendorfer, 1998). Women entrepreneurs may, therefore, seek

3

legitimacy to (1) reduce perceived risk by associating with or by gaining explicit certification

from well-regarded individuals and organizations and (2) enhance persistence to remain in

business (Gimeno et al., 1992). Previous research has postulated and examined the role of social

capital, legitimacy, and risk-taking on new venture growth and sustainability; our study seeks to

delve further into how gender impacts these relations leading to the funding success and

performance of women-run entrepreneurial firms.

Based on signaling theory as a means of forecasting entrepreneurial firm outcomes (e.g.,

Busenitz, Fiet, & Moesel, forthcoming), our study will investigate gender differences within each

of the three research questions (see Figure 1 below that displays the individual relationships

based on our questions):

1. What is the function of social capital in women entrepreneurial perceptions of

legitimacy competence, financial competence success, and firm performance?

2. What is the function of women entrepreneurs’ intensity towards the business and

financial competence and firm performance?

3. What role, if any, does perceptions of legitimacy competence impact firm

performance (beyond the roles of social capital, intensity, and financial competence)?

4

Figure 1Proposed Model of Study

Context of study

The history of modern entrepreneurship in Russia began just over ten years ago when it

was legalized in 1987. Until this, private enterprises were prohibited in the Soviet Union. By the

end of Gorbachev’s presidency of the Soviet Union in 1991, most forms of private business had

become legal (Tkachev and Kolvereid, 1999). Already in 2000, over 891,000 small entrepreneurs

operated in Russia (Russian SME Resource Centre). Over 25% of the population of Russia today

are employed in SMEs, which accounts for 12-15% of GDP of the country (Russian State

Statistic Committee Report for 2003).

During the first years of development toward market economy, the emerging

entrepreneurial sector in Russia could be largely characterized as what Ageev et al. (1995)

labelled as “speculative” or even “predatory” entrepreneurship. The dominant model of

SocialCapital

EntrepreneurialIntensity

FinancialCompetence

FirmPerformance

Perceptions ofLegitimacy

Signaling Theory

5

entrepreneurship was focusing on creating value and making profit from trade and financial

operations, exploiting weaknesses in the state legislation and taxation system, and even utilizing

illegal or unethical measures (Bezgodov, 1999). However, over the passing decade, the situation

has changed and the modern entrepreneurship in Russia is oriented toward longitudinal value and

job creation (Ylinenpåå and Chechurina, 2000).

There has been little scientific research on entrepreneurship in Russia. Based on the

previous research in this area, however, it is possible to draw a “portrait” of the typical

entrepreneur. The average age of Russian entrepreneurs is between 30-50 years, Grichenko et al.,

1992; Turen, 1993, Shamxalov, 1996). Usually, about 70-80% of entrepreneurs from the samples

have completed higher education (Grichenko et al., 1992; Babaeva, 1998). Almost all prior

research on entrepreneurs in Russia was taken from a sociological point of view and data were

gathered from urban areas. Notably, the percentage of women among entrepreneurs is between

10% (Turen et al., 1992) and 30%. This is the lowest share of women among all social groups of

population except militaries (Bezgodov, 1999). Characteristics of entrepreneurs working in small

trade marketplaces are different, however. They are mostly women (70%), and a significant

portion of them are either pensioners or students (Babaeva and Lapina, 1997). Some of the

marketplace owners are registered as sole proprietorships, while others are not. Since in the

present study the focus is on women entrepreneurs, it is expected that they will have different

demographics than those found in previous research on entrepreneurs in Russia.

Based on previous research, it is possible to conclude that most entrepreneurs perceive

the external environment as highly unfriendly. High taxes, inconsistent legislation system, heavy

influence of political turbulence on the economic climate, and inflation were mentioned as

factors prohibiting business in Russia (Ruchkin, 1995, Iakovleva, 2001, Ylinenpåå and

6

Chechurina, 2000). Lack of start-up capital and prevailing business laws and tax system are

especially prohibitive to women entrepreneurship in Russia (Ylinenpåå and Chechurina, 2000).

Other barriers to the development of entrepreneurship mentioned by Russian female

entrepreneurs in the Ylinenpåå and Chachurina study are high taxes (90% of respondents), laws

inconsistency (81%), availability of capital (67%), banks instability (66%), inflation (66%),

corruption (55%), and criminality (39%)This is quite different from problems of American

women entrepreneurs, who are more concerned about functional sides of business – profitability

of business, management and growth, innovation (Babaeva, 1998). Motivations for starting

businesses vary, but in comparison with Western studies, Russian women have more tangible

motives such as search for income or striving for financial rewards. In the Ylinenpåå and

Chachurina study, that contrast is explained by the problematic economic situation in Russia

where the ambition to secure an acceptable standard of living is a high-priority issue.

While the profile and motivation of Russian entrepreneurs was explored in some studies

during the last decade, there is an absence of studies analyzing the combination of different

factors and attempting to explain performance of Russian SME, especially with regard to the role

of women. This study addresses the mentioned research gap by testing a model explaining the

performance of women SME in Russia.

Perceived Legitimacy and Social Capital

Much existing research on women entrepreneurs demonstrates that the process by which

women-led NBVs emerge, grow, and become viable subsumes a complex set of individual

motivators, propensities, and intentions (Gundry & Welsch, 2001). Strategy formulations

underlying the process are complex, as research has shown women entrepreneurs recognize the

7

importance of complex and diverse precursors of growth (e.g., information seeking, planning).

Yet, despite the amount of research on the key factors of female entrepreneurship, no existing

study provides an empirical field assessment of established theory in a gendered context.

Our study is designed to make such a contribution by utilizing signaling theory (Busenitz,

Fiet, & Moeser, 2005; Deeds, Decarolis, & Coombs, 1997) to characterize the content of key

factors and empirically examine established theory (e.g., Aldrich & Fiol, 1994; Stuart, Hoang &

Hybels, 1999) in a gendered context of conformity to social norms, values, and expectations

(Dowling & Pfeffer, 1975). Our undertaking represents the first known empirical examination of

phenomena explained by signaling theory in a gendered context highlighting unique

circumstances facing women entrepreneurs.

Perceived Legitimacy

Being perceived as a legitimate business-person of definite credibility is an important

resource for enhancing NBV survival odds (Suchman, 1995). From this, it follows that

credibility signals offered by entrepreneurs regarding legitimacy are instrumental to procuring

resources (Busenitz et al., 2005). Whereas men and women entrepreneurs both vary in terms of

disadvantages vis-à-vis their peers, Kourilsky and Walstad (1998) add that women entrepreneurs

are more conscious of threats to legitimacy and have less intent to establish NBVs as a result.

Such findings provide context for earlier work by Boyd and Vozikis (1994) positing that beliefs

about abilities impact entrepreneurial intentions. In other words, women are aware of particular

external barriers instead of being less confident or capable as a result of identifiable individual

differences.

8

The perceived legitimacy of entrepreneurs impacts the viability and success of their

NBVs (Aldrich & Fiol, 1994). Thus, with a view toward comparing men and women, we

hypothesized that such legitimacy relates positively to entrepreneurial outcomes of formal

venture funding success, net worth, and longevity.

Leveraging Social Capital

Social capital refers to connections with outside parties providing access to resources and

includes structural, relational, and cognitive dimensions. Its structural dimension subsumes

interaction processes, such as those germane to perceptions of legitimacy (Nahapiet & Ghoshal,

1998). Research posits that the location of an entrepreneur in a social network provides various

types of advantage (e.g., 1992, 1983). Entrepreneurs use informal personal contacts (e.g.,

potential customers, friends) in addition to formal ones (e.g., consultants, venture capitalists) to

obtain information or to access specific resources (e.g., information, financial support).

Research targeting the relation between social capital and entrepreneurial success also

offers middling results. Some research suggests no relation between women’s entrepreneurial

success and social capital (e.g., Carsrud, Gaglio, & Olm, 1987). Other research targets more

specific social activities through phases of NBV development. Greve and Salaff (2003) reported

that women entrepreneurs use different kinds of social capital than men across entrepreneurial

phases. Interestingly, although their study found informal contacts to contribute in all phases,

women generally used such contacts, including family members, much more than men –

including men who inherited their business!

9

Entrepreneurial Motivation: The Role of Entrepreneurial Intensity

While commitment to the entrepreneurial endeavor can be described as the passion

required for success of the enterprise, the degree of commitment exhibited by the entrepreneur is

identified here as entrepreneurial intensity. It is characterized in this study as a single-minded

focus to work towards the growth of the venture, often at the expense of other worthy goals. The

difference between general personality traits and indicators of entrepreneurial intensity were

highlighted by Baum (1995) whose study indicated that while measures of general traits and

personality were a poor indicator of venture growth, more specific applications of these traits

such as “growth specific motivation” showed far stronger relationships with growth

performance. Davidsson and Wicklund (2001) specifically state that amongst the new directions

for research of the entrepreneur at the individual level of analysis, “it is the study of what actions

‘nascent entrepreneurs’ take, and in what sequence, in order to get their business up and

running…is perhaps the most promising development to be expected.”

Methodology

To test our research questions, a sample of Russian women-led SME was used. Data were

obtained from the Russian Women’s Microfinancial Network (RWMN). The mission of the

RWMN is to support the development of sustainable, women-focused, locally managed

microfinance institutions (MFIs) throughout Russia by creating an effective financial and

technical structure that provides high-quality services to partner MFIs over the long-term. With

assistance from Women's World Banking (WWB; active in Russian since 1994), several women-

led organisations and local microlending institutions formed RWMN. It was registered as a local

non-profit organization in October 1998. Today RWMN operate in 6 regions in Russia:

10

Kostroma, Tver, Kaluga, Belgorod, Vidnoe, Tula with the head office in Moscow. Each division

is an independent local organisation that provides micro loans for clients, with women

comprising no less than 51% of client base.

After the questionnaire was constructed and pre-tested with the help of 7 Russian women

entrepreneurs that commented on each question, it was send in electronic form to Moscow.

RWMN was responsible for printing and distributing it to its divisions. Data were collected by

the workers of local divisions during face-to face interviews with respondents. As a result, we

initially received 601 questionnaires. Five of them were removed due to the missing data and the

remaining sample was filtered on the following two controls: only women should be left (we

found 5 male responses), and they must be the decision-makers (positive answer to the question,

“Are you the responsible for the main decisions taken in the enterprise?”). That resulted in 555

questionnaires. The sample mainly consisted of sole proprietorships with 94% of businesses

having no more than 10 employees (and 60% having just 2 employees), woman-led and woman-

owned (95%), operating mainly in the service industry (80%), with 56% of enterprises being

family businesses. Another interesting finding is that only 49% of respondents have higher

education, in comparison to 80% from pervious studies (Grichenko et al., 1992; Kofanova, 1997,

Iakovleva 2005). This profile, as expected, differs from the typical Russian SME profile with

regard to industry structure, legal form, number of employees and family business issues (see for

example Iakovleva, 2005, Bezgodov, 1999).

11

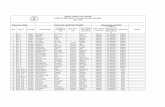

Table 1

Sample Characteristics

Variables Number Percent

RespondentsRespondent statusFounders or(and) owners(shareholders) 525 95%Directors or (and) managers( just employees) 30 5%

Average respondent age 40 years

Higher educationYes 252 49No 271 51

Entrepreneurial experience of relativesYes 76 14No 469 86EnterprisesSubsidiary of another businessYes 24 5No 525 95

Family businessYes 310 56No 242 44

Average firm age 8

Average number of employees 4

Legal formLimited liability companies 33 6Closed joint-stock companies 3 0.5Open joint-stock companies 2 0.4Sole proprietorships 514 93IndustryManufacturing 28 5Trade and catering consumption 442 80Service 81 15

12

Measures

Firm Performance

Performance is the multidimensional concept. There is little consistency in what is meant

under the term ‘performance’ in different studies. Three different measures are most often

associated with the concept of performance: survival of the firm, firm growth and firm

profitability (Delmar, 2000). It is advised that studies should include the multiple dimensions of

performance and use multiple measures of those dimensions (Murphy et al., 1996). In the present

study, only existing firms are considered, and questions related to both growth and profitability

are applied. A measurement of performance is extremely complex for young and small firms.

Such traditional financial measures as return on investments or net profits are problematic when

studying new ventures, since even successful start-ups often do not offer rich profitability for a

considerable period of time (Weiss, 1981). Traditional financial measures are especially

unreliable in Russian context. Due to heavy taxation rates, small enterprises seldom report true

economical results in accounting. The other specific reason of not applying such direct measures

in Russian context is that Russian statutory accounting norm and practices differ greatly from

international accounting norms and practices. Researchers interested in the performance of

emerging businesses must acquire data that meet the criteria of relevance, availability, reliability

and validity when the only attainable source of data is a self-administrated evaluative

questionnaire (Chandler and Hanks, 1993).

Performance is measured with the help of importance and satisfaction questions on

certain items. Respondents were asked to indicate the degree of importance their enterprise

attaches to the following items over the past three years: sales level, sales growth, turnover,

profitability, net profit, gross profit and to the ability to fund enterprise growth from profits.

13

Then, they were asked how satisfied they have been with the same indicators over the past three

years. A slightly modified version of questions used by Iakovleva (2005) was applied.

Originally, questions were taken partly from Chandler and Hanks (1993) and partly from

Westhead, Ucbasaran, and Wright (2005). They were then transformed after the consultation

with Russian entrepreneurs. The questionnaire we used for the present study was pre-tested with

seven Russian women business owners, and some questions were reformulated after that. Based

on these 14 questions, the Composite performance index was constructed following the principle

used in expectancy theory and later in Theory of Planned Behaviour (Ajzen, 1991). First,

importance questions were rescaled from 7-point Likert scale (1 to 7) to scale (-3 to 3), and than

satisfaction and importance scores were multiplied. After that, principal component analysis was

done, which resulted one factor which we called performance (_=0.95).

Table 2

PCA for Composite Performance

Variables Factorloadings

Communality

Composite PerformanceSales level satisfaction*importance 0.87 0.76Sales growth satisfaction*importance 0.89 0.80Turnover satisfaction*importance 0.87 0.75Profitability satisfaction*importance 0.90 0.81Net profit satisfaction*importance 0.88 0.78Gross profit satisfaction*importance 0.88 0.78Ability to fund business from the profitsatisfaction*importance

0.80 0.64

Eigenvalue 5.31Percent variance explained 75.85Chronbach’s alpha 0.95

Note: Factor loadings 0.3 or smaller are suppressed. KMO =0.925, Bartletts’s test of SphericityApp. Chi-Sq 3392.079; df=21, Sig. 000.

14

Social Capital

Social capital was operationalised with the help of four questions: employee’s network as

an informational source, firm network as instrument to influence environment, network as the

way to broader opportunities and manager’s network as important firm resource. Questions are

taken from Borch et al. (1999). Cronbach’s alpha for this component is 0.88.

Entrepreneurial Intensity

Respondents were asked to rate disagreement/agreement with eight statements using a 7-

point Likert scale 1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree. Four items are taken from Grundy

and Welsch (2001) – own business vs. earn high salary as employed by someone else; own

business vs. pursuing another promising carer; make personal sacrifices in order to stay in

business; work somewhere else only long enough to make another attempt), one item is taken

from Isaksen and Kolvereid (2005): willing to work more with the same salary in own business.

Four questions were taken from Gundry and Welsch (2001): I would work somewhere else only

long enough to make another attempt to establish my business; my business is the most

important activity in my life; I would do whatever it takes to make my business a success; there

is no limit to how long I would give a maximum effort to establish my business. Cronbach’s

alpha for this component is 0.89.

Perceived Legitimacy

To assess perceived legitimacy, respondents were asked to rate disagreement/agreement

with statements using a 7-point Likert scale 1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree. Two items

are taken from Brown and Kirchhoff (1997): banks and other suppliers of loan capital are

15

generally very interested in financing businesses like mine; investors are generally very

interested in financing businesses like mine. One item was taken from Isaksen (2006): investors

would generally quite easy understand the technology used in my business. Cronbach’s alpha for

this component is 0.63.

Financial Capital

Financial capital was operationalised with the help of four questions. First three questions

are taken from Shane and Kolvereid (1996): availability of bank loans, availability of capital

from suppliers; availability of capital from family and friends. The last item is taken from Borch

et al. (1999): availability of financial resources relative to competitors. Cronbach’s alpha for this

component is 0.77.

Analytic Approach

We tested our hypotheses using structural equation modeling (SEM) since it effectively

estimates parameters of our model. A covariance matrix was used as input for estimation of the

structural models. Lisrel VIII (Joreskog & Sorbom, 1993) was utilized to analyze the structural

relationships. Aggregation was conducted for each common construct in order to have

unidimensional composite scales for the structural models (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). In order

to adjust for measurement error in the scale scores, the path from the latent variable to its

indicator was set equal to the product of the square root of the scale’s internal reliability. The

error variance was set equal to the variance of the scale score multiplied by 1 minus the

reliability. This approach has been explained by Williams and Hazer (1986) and Joreskog and

16

Sorbom (1993), and has been demonstrated as a reasonable approximation in determining error

variance (Netemeyer, Johnston, & Burton, 1990).

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Zero-Order Correlations

The means, standard deviations, zero-order correlations and reliabilities for our constructs

are reported in Table 2. With the exception of our perceptions of legitimacy measure, all

reliabilities of the measures used were over the .70 minimum established by Nunnally (1978).

Table 2

Means, Standard Deviations, Zero-Order Correlations, and Reliabilities of Measures

Variable Mean SD 1 2 3 4 5

1. Entrepreneurial Intensity 6.07 1.34 (.89)

3. Social Capital 5.22 1.73 .24** (.88)

3. Perceptions of

Legitimacy

3.72 1.63 .10* .35** (.63)

4. Financial Competence 4.15 1.64 .19** .44** .45** (.77)

5. Firm Performance (---) (---) .20** .25** .29** .33** (.95)

Note: **p<.01; *p<.05; Firm Performance measure was standardized.

In order to determine the structural relationships proposed in our model (see Figure 1), a

series of models were evaluated by comparing the change in chi-square associated with the

17

restriction of certain paths to zero (Bentler & Bonett, 1980). The proposed structural model,

which contains all potential paths in our three research questions, (fully saturated model as

shown in Figure 1) was first evaluated. This model had a c2 of 79.25 with 2 degrees of freedom

(GFI=.95; CFI=.85; Standardized RMR=.082).

The model evaluated examined the aggregate of our three research questions, and not the

individual relationships. Below in Figure 2 are the Lisrel estimates of the individual

relationships. All relationships were significant with the exception of the relationship between

social capital and firm performance. A follow-up analyses by removing the path from social

capital to performance revealed that deleting this path would not also significantly improve the

model fit (parsimonious model without relationship is acceptable).

Figure 2Lisrel Estimates of the Individual Relationships

SocialCapital

EntrepreneurialIntensity

FinancialCompetence

FirmPerformance

Perceptions ofLegitimacy

.24

.10

.04

.33

.13

.12

Red signals significantrelationship at .05 level,Black is non-significant

18

However, in analyzing the initial diagnostic information provided in Lisrel (modification

indices from the structural model), we found based on the output that the Modification Indices

suggest to add the following:

Path to from Decrease in Chi-Square New Estimate Legitimacy Financial capital 78.9 0.62 Legitimacy Performance 54.2 2.01 Financial capital Legitimacy 78.3 0.21 Financial capital Performance 78.3 2.22

From these indices, it appears that perceived legitimacy plays a key role in signalling to

others the credibility of the firm and is often gained not only through social capital networks but

also through proven firm performance and having competence on the financial aspects of

operating the business.

Discussion

Although the process towards continual performance and growth is often a complex

interplay of a variety of resources, motivators, and intentions, our findings make an important

contribution to our understanding of how Russian women-led entrepreneurial firms both

integrate and align these factors towards this strategic path. Identifying constructs facilitating

firm performance has added value for practitioners, scholars, and policy makers as they

formulate and implement new strategies and programs that support women entrepreneurs as they

continue to identify market opportunities, confront industry and environmental changes, and seek

new innovations for their businesses.

The emergence and growth of women-owned businesses have contributed to the global

economy and to their surrounding communities. The presence of women around the world

19

driving small and entrepreneurial organizations has had a tremendous impact on employment and

on business environments worldwide. Scholars of strategic management have noted that firm

and organizational resources (including the competency and intensity of the owner) key elements

in highly successful firms. However, little work has examined the impact of structural

components in the context of entrepreneurial ventures. Given the significant differences between

large, established firms and entrepreneurial ventures, uncovering which resources and

capabilities takes on added importance in facilitating the performance of smaller women-led

organizations.

Directions for Future Research

While motivations to undertake business ownership have become more generally

understood through research, more work is needed to examine the factors that contribute to

sustained entrepreneurship, especially in the stages beyond start-up (Bhave, 1994; Kuratko,

Hornsby, & Naffziger, 1997). Cliff (1998) proposed that women entrepreneurs prefer a

managed approach to business growth as opposed to following more risky growth strategies.

Growth orientation has been found to relate significantly to actual firm performance. In a study

of over 800 women entrepreneurs, the ones who headed high-growth-oriented businesses

demonstrated stronger commitment to the success of the business, a greater willingness to

sacrifice on behalf of the business, earlier planning for growth, adequate capitalization, and used

a team-based form of organization design. Further, these firms emphasized market growth and

technological change as strategic intentions (Gundry & Welsch, 2001).

Gundry, Ben-Yoseph, & Posig (2002) have commented on the sometimes daunting

challenge of many women entrepreneurs in locating and obtaining the appropriate information

20

needed to take the business to the next level of growth. To assist in this process, community-

based organizations have been formed for the purpose of providing interconnections among

women entrepreneurs and information resources. For example, Promotion of Women

Entrepreneurs (ProWomEn) was recently launched by the European Commission, in which

representatives of twenty regions in EU member and associated countries come together to

discuss and share policies and actions that promote the creation of businesses by women.

Objectives for this project include enhancing the awareness of decision makers about the

importance of promoting women entrepreneurs; identifying case studies and best practices for

supporting women entrepreneurs; setting up regional networks and pilot projects; and changing

education and training systems to build a culture of women’s entrepreneurship (Clothier, 2001).

Additional research should examine how women entrepreneurs across cultures utilize these

social and financial resources and leverage the importance of these activities including

information seeking and training and education to further develop and grow their businesses.

Conclusion

This research promises to offer much needed understanding and delineation of the

dynamic factors driving firm performance in a gendered context in the Russian economy.

Signaling theory (Janney & Folta, 2003) offers the conceptual foundation, and the data sources

offer means to obtain relevant empirical tests. It is expected that the additional analyses will

yield an integrative model incorporating perceived legitimacy, risk preference, and social capital

to illustrate the unique and differential role each one has on contributing to the performance and

growth of women-led ventures, particularly those in transitioning and emerging markets.

References

21

Ajzen, I. (1991), ‘The theory of planned behavior’, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50:179-211.

Ageev, A. Gratchev, M. and Hirich, R. (1995), ‘Entrepreneurship in the Soviet Union and post-socialist Russia’,Small Business Economics, 7: 365-367.

Aldrich, H.E. and Fiol, C.M. (1994), Fools rush in? The institutional context of industry creation.

Academy of Management Review, 19(4): 645-670.

Anderson, J.C., & Gerbing, D.W. (1988), Structural equation modeling in practice: Areview and recommended two-step approach, Psychological Bulletin, 49, 411-423.

Anna, A. L., Chandler, G. N., Jansen, E. & Mero, N. P. (2000), ’Women business owners in traditional and non-traditional industries’, Journal of Business Venturing, 15: 279-303.

Babaeva, L. and Lapina, G. (1997), Small business in Russia in the period of economical reforms (_____ ______ _______ _ _____ _____________ ______). Russia: Moscow.

Babaeva, L. (1998), ‘Russian and American female entrepreneurs’ (__________ _ ____________ _______-_______________), Sociological Review (_______________ ____________), 8, 134-135.

Baum, R. (1995), The Relation of Traits, Competencies, Motivation, Strategy, and Structure to Venture Growth. InW. Bygrave, B. Bird, S. Birley, N. Churchill, M. Hay, R. Keeley & William Wetzel Jr. (Eds), Frontiers ofEntrepreneurship Research. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University, Babson College Press.

Bentler, P.M., & Bonett, D.G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis ofcovariance structures, Psychological Bulletin, 88, 588-606.

Bezgodov, A. (1999), Entrepreneurship sociology (______ __________ ___________________) St. Petersburg,Petropolis (___, «__________»).

Bhave, M. (1994), ‘A Process Model of Entrepreneurial Venture Creation’, Journal of Business Venturing, 8, 223-242.

Borch, O.J., Morten; H.; Senneseth; K. (1999), ‘Resource configuration, competitive strategies, and corporateentrepreneurship: An empirical examination of small firms’, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 42(1): 49-71.

Boyd, N. and Vozikis, G. (1994), ‘The influence of self-efficacy on the development of entrepreneurial intentionsand actions’, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 18(4), 63-77.

Brown, T. E., & Kirchhoff, B. A. (1997), ‚The effects of resource availability and entrepreneurial orientation on firmgrowth’, in P. D. Reynolds, W. D. Bygrave, N. M. Carter, P. Davidsson, W. B. Gartner, C. M. Mason, & P. PMcDougan (Eds.), Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research. Wellesley, Mass: Babson College: 32-46.

Bruderl, J. & Preisendorfer, P. (1998), Network support and the success of newly foundedbusinesses. Small Business Economics, 10(3): 213-225.

Brush, C., & Hisrich, R. (1988), ‘Women Entrepreneurs: Strategic Origins Impact on Growth’, Frontiers ofEntrepreneurship Research, Wellesley, MA: Babson College, 612-625.

Carsrud, A.L., Gaglio, C.M., & Olm, K.W. (1987), ‘Entrepreneurs – Mentors, Networks, and Successful NewVenture Development: An Exploratory Study’, American Journal of Small Business, 12(2), 13-18.

22

Center for Women’s Business Research (2005), Top Facts, Washington, D.C: Center for Women’s BusinessResearch.

Center for Women’s Business Research (2004), ‘Privately-Held, Majority (51% or More) Women-OwnedBusinesses in the United States, 2004’ Washington, D.C: Center for Women’s Business Research.

Chaganti, R. and Parasuraman, S. (1997), ‘A study of the impacts of gender on business performance andmanagement patterns in small businesses’, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 21, 2; 73-76

Chandler, G. N. and Hanks, S. H. (1993), ‘Measuring the performance of emerging businesses: a validation study’,Journal of Small Business Management, 8: 391-408.

Cliff, J.E. (1998), ‘Does One Size Fit All? Exploring the Relationship Between Attitudes Towards Growth,Gender, and Business Size’, Journal of Business Venturing, 13(6), 523-542.

Clothier, S. (2001), ‘Cracking the Glass Ceiling in Europe’, British Journal of Administrative Management, 24(March, April), 21-22.

Davidsson, P., & Wicklund, J. (2001), Levels of analysis in entrepreneurship research: Current research practice andsuggestions for the future. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 25: 81-99.

Deeds, D.L., Decarolis, D., and Coombs, J.E. (1997), The impact of firm-specific capabilities onthe amount of capital raised in an initial public offering: Evidence from thebiotechnology industry. Journal of Business Venturing, 12(1): 31-46.

Delmar, F. and Davidsson, P. (2000), ‘Where do they come from? – Prevalence and characteristics of nascententrepreneurs’, Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 12: 1-23.

Dowling, J. and Pfeffer, J. 1975. Organizational legitimacy: Social values and organizationalbehaviour. Pacific Sociological Review, 18(1): 122-136.

Granovetter, M. (1992). Problems of Explanation in Economic Sociology. In N. Nohria & R. Eccles (Eds.),Networks and Organizations: Structure, Form, and Action, 25- 56. Boston: Harvard Business School Press

Greve, A., & Salaff, J.W. (2003), ‘Social Networks and Entrepreneurship’, Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice,28(1), 1-22.

Gimeno, J., Folta, T.B., Cooper, A.C. and C.Y. Woo. (1997), Survival of the fittest?Entrepreneurial human capital and the persistence of underperforming firms. AdministrativeScience Quarterly 42:750-783.

Grishenko, G., Novikova, L., Lapsha, I. (1992), ‘Social portrait of entrepreneur’ (__________ _____________________), Sociological Review (_______________ ____________), 10:53.

Gundry, L.K. (1997), ‘The leadership focus of women entrepreneurs at start-up and growth’, Women In Leadership,2(1), 4-16.

Gundry, L.K., Ben-Yoseph, M., & Posig, M. (2002b), ‘Contemporary Perspectives on Women’s Entrepreneurship:A Review and Strategic Recommendations’, Journal of Enterprising Culture, 10(1), 67-86.

Gundry, L.K., & Welsch, H.P. (2001), ‘The Ambitious Entrepreneur: High-Growth Strategies of Women-OwnedEnterprises’, Journal of Business Venturing 16(5), 453-470.

Iakovleva, T. (2001), Entrepreneurship Framework Conditions in Russia and in Norway: Implications for theEntrepreneurs in the Agrarian Sector, Hovedfagsoppgaven, Norway: Bode Graduate School of Business.

23

Iakovleva, T. (2005), ‘Entrepreneurial orientation of Russian SME’, in G.T. Ving and R.C.W. Van der Voort (eds),The Emergence of Entrepreneurial Economic, UK, Elsevier Ltd, pp.83-98.

Isaksen, E. (2006) “Early Business Performance – Initial factors effecting new business outcomes”, Doctoraldissertation, Handelhøgskolen i Bode.

Isaksen, E. & Kolvereid, L. (2005), ‘Growth objectives in Norwegian start-up businesses’, International Journal ofEntrepreneurship and Small Business, 2, 1, pp. 17-26.Higgins, M. C., and R. Gulati (2000), "Getting off to a good start: The effects of upper echelon affiliations oninterorganizational endorsements." Harvard Business School working paper 00-025.

Joreskog, K.G., & Sorbom, D. (1993). LISREL VIII: A guide to the program and applications. Chicago, IL: SPSS.Kamau, D.G., McLean, G.N., & Ardishvili, A. (1999), ‘Perceptions of Business Growth By Women Entrepreneurs’,Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research. Wellesley, MA: Babson College

Kim, W.C., and Mauborgne, R. (1997), ‘Value Innovation: The Strategic Logic ofHigh Growth’, Harvard Business Review 75 (1), 102-112.

Kofanova, T. (1997), ‘Emerging of youth entrepreneurship’ (___________ ___________ ___________________),Conditions and factors of forming of the Russian entrepreneurship (_______ _ _______ _______________________ ___________________). Russia: Kostroma, pp. 64-65.

Kourilsky, M. & Walstad, M. (1998), “Entrepreneurship and The Female Youth: Knowledge, Attitudes, GenderDifferences and Educational Practices.” Journal of Business Venturing, 13: 77-88.

Kuratko, D.F., Hornsby, J.S., and Naffziger, D.W. (1997), ‘An Examination of Owner's Goals in SustainingEntrepreneurship’, Journal of Small Business Management 35(1), 24-33.

Lerner, M. and Almor, T. (2002), ‘Relationships among strategic capabilities and the performance of women-ownedsmall ventures’, Journal of Small Business Management, 40(2), 109-125.Lerner, M., Brush, C., and Hisrich, R (1997),’ Israeli Women Entrepreneurs: An Examination of Factors AffectingPerformance’, Journal of Business Venturing, 12(4), 315-339.

Murphy, G. B., Trailer, J. W., Hill, R.C., (1996), ‘Measuring performance in entrepreneurship research’, Journal ofBusiness Research, Vol. 36, Iss. 1; 15-24.

Nahapiet, J., & Ghoshal, S. (1997), ‘Social Capital, Intellectual Capital and the Creation of Value in Firms’,Academy of Management Best Paper Proceedings: 35-39.

Netemeyer, R., Johnston, M., & Burton, S. (1990), Analysis of role conflict and role ambiguity in a structuralequations framework, Journal of Applied Psychology, 75, 148-157.

Rao, H. (1994), The social construction of reputation: Certification contests, legitimation and the survival oforganizations in the American automobile industry, 1895-1912. Strategic Management Journal. 15: 29-44.

Russian SME Resource Centre http://www.rcsme.ru

Russian State Statistic Committee Report 2003

Ruchkin, B. (1995), ‘Young entrepreneurs as the social strata of modern Russian society’ (______________________ ___ __________ ______ ____________ ___________ ________), in Factors of emerging of thesocial view of young Russian entrepreneurship. (_______ ___________ ___________ ______ ___________________ ___________________). Materials of the international research conference of 1994. Russia: NigniiNovgorod, p. 7-11.

24

Shane, S. and Kolvereid. L. (1995), ‘National environment, strategy and new venture performance: A three countrystudy’, Journal of Small Business Management, April, 37-50.

Shamxalov, V. (1996), Entrepreneurship in Russia: emerging and development problems (___________________ _______. ___________ _ ________ ________), Russia, “Moskva”.

Singh, J. V., Tucker, D. J., and Meinhard, A. G. (1991), “Institutional Change and Ecological Dynamics.” In W. W.Powell and P. J. DiMaggio (Eds.) The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis, 390–422. Chicago: TheUniversity of Chicago Press.

Stuart, T.E., Hoang, H., and Hybels, R.C. (1999), Interorganizational endorsements and theperformance of entrepreneurial ventures. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2): 315-349.

Suchman, M.C. (1995), Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Academy of ManagementReview, 20(3): 571-610.

Tkachev, A. and Kolvereid, L. (1999), ’Self-employment intentions among Russian students’, Entrepreneurship andRegional Development, 11, 3, 269-280.

Turen, A. eds. (1993), Russian entrepreneurship: Experience of sociological analysis. Russia: Moscow.

Weiss, C.A. (1981), Start up business: A comparison of performances. SloanManagement Review (23), 37-53

Westhead, P.; Ucbasaran, D.; Wright, M. (2005), ‘Decisions, Actions and Performance: Do Novice, Serial andPortfolio Entrepreneurs Differ?’, Journal of Small Business Management, 43,4, 393-417.

Williams, L.J., & Hazer, J.T. (1986), Antecedents and consequences of satisfaction and commitment in turnovermodels: A reanalysis using latent variable structural equation methods, Journal of Applied Psychology, 71,219-231.

Ylinenpåå, H. and Chechurina, M. (2000), ‘Perceptions of female entrepreneurs in Russia. In D. Deschoolmestereds., in seminar proceedings Entrepreneurship under difficult circumstances, Best Paper in 30th European SmallBusiness Seminar. Gent, Belgium.